User login

Mitchel is a reporter for MDedge based in the Philadelphia area. He started with the company in 1992, when it was International Medical News Group (IMNG), and has since covered a range of medical specialties. Mitchel trained as a virologist at Roswell Park Memorial Institute in Buffalo, and then worked briefly as a researcher at Boston Children's Hospital before pivoting to journalism as a AAAS Mass Media Fellow in 1980. His first reporting job was with Science Digest magazine, and from the mid-1980s to early-1990s he was a reporter with Medical World News. @mitchelzoler

AES: Development of unobtrusive seizure-detection devices continues

PHILADELPHIA – Reliable, externally worn seizure-detection devices for epilepsy patients have been eagerly sought but elusive. New results from the pivotal trial of an arm-mounted device that works by analyzing skin electromyography showed promise when tested in 142 adults and children with epilepsy who also underwent video EEG monitoring, Dr. José E. Cavazos reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

More than 7,000 hours of simultaneous surface electromyography with the investigational device, worn on the patient’s upper arm, and video EEG monitoring as the gold standard for seizure detection showed that the device correctly identified all 29 generalized tonic-clonic seizures experienced by the 142 patients studied. This level of detection came with a false-positive rate of 1.47 false events during every 24 hours of monitoring, with most of the false positives occurring when the device was being placed or removed.

The results made Dr. Cavazos hopeful that the Food and Drug Administration would clear the device, the Brain Sentinel Seizure Detection and Warning System, for U.S. marketing in 2016. The FDA first received the marketing-clearance application in late 2014, said Dr. Cavazos, an epileptologist and professor of neurology at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

But Dr. Cavazos also conceded that receiving FDA clearance for U.S. sale of the device is just the next step in an ongoing process to prove its clinical value.

“Currently, clinical decisions for epilepsy patients are often based on patient-reported seizure counts. There is a clear need for objective data on seizure frequency,” something now obtainable only by running an expensive visual-monitoring study, said Dr. Cavazos, who is also founder of and a stockholder in the company that is developing this device. “We definitely need to show in future studies that monitoring [with the worn device] has a positive impact on patient care, by reducing hospitalizations and producing improved patient outcomes,” he said in an interview. “These data may be enough to get regulatory clearance to sell the device, but insurers may not want to reimburse for it until we can prove its value.”

When the device detects a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, it produces an audible alert and also starts recording both surface EMG data and local audible sounds for use in future analysis of the patient’s status. In the study, seizure detection occurred an average of 14 seconds following seizure onset as judged by visual EEG monitoring adjudicated by three epileptologists. The study also included an additional 31 patients who initially entered the study and began wearing the device but did not complete the monitoring protocol because of an adverse effect while wearing the monitor, usually mild or moderate skin irritation.

The results from this study come in a context of extensive research efforts aimed trying to find reliable and unobtrusive methods to quickly detect seizures short of running an observational study. The best results so far have come when using devices that monitor brain EEG signals with electrode-containing caps or implanted electrodes. But patients have voiced substantially reduced interest in having to resort to such stigmatizing methods, noted Dr. Elizabeth Donner during a separate talk at the meeting.

“Patients don’t want what looks like an EEG-detection device. We need devices that suit our patients’ needs,” said Dr. Donner, an epileptologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Aside from direct measurement of EEG, other approaches involve measurement of heart rate or movement, she noted.

“There are very good techniques for detecting seizures without using EEG,” said Dr. Gregory L. Krauss, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who joined Dr. Donner in a discussion of the pros and cons of current methods for seizure detection. He specifically cited a heart-rate based detection scheme reported last year by a Belgian team (Seizure. 2015 Nov;[32]:52-61). But like all detection methods, the heart rate–based approach showed a marked trade-off between sensitivity and specificity: A heart-rate threshold of at least 50% above baseline had a sensitivity of 82% while identifying one false positive every hour. Raising the detection threshold to at least 30% above baseline boosted the sensitivity to 91%, but with the cost of flagging 3.5 false positives each hour.

Dr. Krauss is currently trying to develop a motion-based approach to identifying seizure onset using an Apple watch, He concluded that, as of now, development of seizure-detection devices that do not rely on direct measurement of brain EEG patterns remains a work in progress, with no prospectively collected data, although he made this assessment prior to the poster report by Dr. Cavazos at the meeting.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Reliable, externally worn seizure-detection devices for epilepsy patients have been eagerly sought but elusive. New results from the pivotal trial of an arm-mounted device that works by analyzing skin electromyography showed promise when tested in 142 adults and children with epilepsy who also underwent video EEG monitoring, Dr. José E. Cavazos reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

More than 7,000 hours of simultaneous surface electromyography with the investigational device, worn on the patient’s upper arm, and video EEG monitoring as the gold standard for seizure detection showed that the device correctly identified all 29 generalized tonic-clonic seizures experienced by the 142 patients studied. This level of detection came with a false-positive rate of 1.47 false events during every 24 hours of monitoring, with most of the false positives occurring when the device was being placed or removed.

The results made Dr. Cavazos hopeful that the Food and Drug Administration would clear the device, the Brain Sentinel Seizure Detection and Warning System, for U.S. marketing in 2016. The FDA first received the marketing-clearance application in late 2014, said Dr. Cavazos, an epileptologist and professor of neurology at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

But Dr. Cavazos also conceded that receiving FDA clearance for U.S. sale of the device is just the next step in an ongoing process to prove its clinical value.

“Currently, clinical decisions for epilepsy patients are often based on patient-reported seizure counts. There is a clear need for objective data on seizure frequency,” something now obtainable only by running an expensive visual-monitoring study, said Dr. Cavazos, who is also founder of and a stockholder in the company that is developing this device. “We definitely need to show in future studies that monitoring [with the worn device] has a positive impact on patient care, by reducing hospitalizations and producing improved patient outcomes,” he said in an interview. “These data may be enough to get regulatory clearance to sell the device, but insurers may not want to reimburse for it until we can prove its value.”

When the device detects a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, it produces an audible alert and also starts recording both surface EMG data and local audible sounds for use in future analysis of the patient’s status. In the study, seizure detection occurred an average of 14 seconds following seizure onset as judged by visual EEG monitoring adjudicated by three epileptologists. The study also included an additional 31 patients who initially entered the study and began wearing the device but did not complete the monitoring protocol because of an adverse effect while wearing the monitor, usually mild or moderate skin irritation.

The results from this study come in a context of extensive research efforts aimed trying to find reliable and unobtrusive methods to quickly detect seizures short of running an observational study. The best results so far have come when using devices that monitor brain EEG signals with electrode-containing caps or implanted electrodes. But patients have voiced substantially reduced interest in having to resort to such stigmatizing methods, noted Dr. Elizabeth Donner during a separate talk at the meeting.

“Patients don’t want what looks like an EEG-detection device. We need devices that suit our patients’ needs,” said Dr. Donner, an epileptologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Aside from direct measurement of EEG, other approaches involve measurement of heart rate or movement, she noted.

“There are very good techniques for detecting seizures without using EEG,” said Dr. Gregory L. Krauss, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who joined Dr. Donner in a discussion of the pros and cons of current methods for seizure detection. He specifically cited a heart-rate based detection scheme reported last year by a Belgian team (Seizure. 2015 Nov;[32]:52-61). But like all detection methods, the heart rate–based approach showed a marked trade-off between sensitivity and specificity: A heart-rate threshold of at least 50% above baseline had a sensitivity of 82% while identifying one false positive every hour. Raising the detection threshold to at least 30% above baseline boosted the sensitivity to 91%, but with the cost of flagging 3.5 false positives each hour.

Dr. Krauss is currently trying to develop a motion-based approach to identifying seizure onset using an Apple watch, He concluded that, as of now, development of seizure-detection devices that do not rely on direct measurement of brain EEG patterns remains a work in progress, with no prospectively collected data, although he made this assessment prior to the poster report by Dr. Cavazos at the meeting.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Reliable, externally worn seizure-detection devices for epilepsy patients have been eagerly sought but elusive. New results from the pivotal trial of an arm-mounted device that works by analyzing skin electromyography showed promise when tested in 142 adults and children with epilepsy who also underwent video EEG monitoring, Dr. José E. Cavazos reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

More than 7,000 hours of simultaneous surface electromyography with the investigational device, worn on the patient’s upper arm, and video EEG monitoring as the gold standard for seizure detection showed that the device correctly identified all 29 generalized tonic-clonic seizures experienced by the 142 patients studied. This level of detection came with a false-positive rate of 1.47 false events during every 24 hours of monitoring, with most of the false positives occurring when the device was being placed or removed.

The results made Dr. Cavazos hopeful that the Food and Drug Administration would clear the device, the Brain Sentinel Seizure Detection and Warning System, for U.S. marketing in 2016. The FDA first received the marketing-clearance application in late 2014, said Dr. Cavazos, an epileptologist and professor of neurology at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

But Dr. Cavazos also conceded that receiving FDA clearance for U.S. sale of the device is just the next step in an ongoing process to prove its clinical value.

“Currently, clinical decisions for epilepsy patients are often based on patient-reported seizure counts. There is a clear need for objective data on seizure frequency,” something now obtainable only by running an expensive visual-monitoring study, said Dr. Cavazos, who is also founder of and a stockholder in the company that is developing this device. “We definitely need to show in future studies that monitoring [with the worn device] has a positive impact on patient care, by reducing hospitalizations and producing improved patient outcomes,” he said in an interview. “These data may be enough to get regulatory clearance to sell the device, but insurers may not want to reimburse for it until we can prove its value.”

When the device detects a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, it produces an audible alert and also starts recording both surface EMG data and local audible sounds for use in future analysis of the patient’s status. In the study, seizure detection occurred an average of 14 seconds following seizure onset as judged by visual EEG monitoring adjudicated by three epileptologists. The study also included an additional 31 patients who initially entered the study and began wearing the device but did not complete the monitoring protocol because of an adverse effect while wearing the monitor, usually mild or moderate skin irritation.

The results from this study come in a context of extensive research efforts aimed trying to find reliable and unobtrusive methods to quickly detect seizures short of running an observational study. The best results so far have come when using devices that monitor brain EEG signals with electrode-containing caps or implanted electrodes. But patients have voiced substantially reduced interest in having to resort to such stigmatizing methods, noted Dr. Elizabeth Donner during a separate talk at the meeting.

“Patients don’t want what looks like an EEG-detection device. We need devices that suit our patients’ needs,” said Dr. Donner, an epileptologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Aside from direct measurement of EEG, other approaches involve measurement of heart rate or movement, she noted.

“There are very good techniques for detecting seizures without using EEG,” said Dr. Gregory L. Krauss, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who joined Dr. Donner in a discussion of the pros and cons of current methods for seizure detection. He specifically cited a heart-rate based detection scheme reported last year by a Belgian team (Seizure. 2015 Nov;[32]:52-61). But like all detection methods, the heart rate–based approach showed a marked trade-off between sensitivity and specificity: A heart-rate threshold of at least 50% above baseline had a sensitivity of 82% while identifying one false positive every hour. Raising the detection threshold to at least 30% above baseline boosted the sensitivity to 91%, but with the cost of flagging 3.5 false positives each hour.

Dr. Krauss is currently trying to develop a motion-based approach to identifying seizure onset using an Apple watch, He concluded that, as of now, development of seizure-detection devices that do not rely on direct measurement of brain EEG patterns remains a work in progress, with no prospectively collected data, although he made this assessment prior to the poster report by Dr. Cavazos at the meeting.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT AES 2015

Key clinical point: A seizure-detection device worn on the arm showed good sensitivity and reasonable specificity, but no data yet exist on its clinical utility.

Major finding: The Brain Sentinel device had 100% sensitivity while resulting in 1.47 false-positive alarms every 24 hours.

Data source: The pivotal trial for the Brain Sentinel device, which collected detection data from 142 adults and children with a history of seizures.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Brain Sentinel, which is developing the device. Dr. Cavazos is a founder of the company, holds stock in the company and is a consultant to the company. Dr. Donner had no disclosures. Dr. Krauss has been a consultant to SK Life Science, Acorda Therapeutics, and Sunovion and has received research support from Upsher-Smith, SK Life Science, UCB, Novartis, and Pfizer.

STS: Planning for mass casualties builds on routine trauma care

PHOENIX – Surgeons are the logical choice for taking the lead in formulating a hospital plan for dealing with mass casualties, and when doing so they should use their usual trauma-management practices as the cornerstone, Dr. Kenneth L. Mattox recommended at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“The disaster plan is built on the trauma plan, and surgeons are at the heart of it,” said Dr. Mattox, chief of staff and surgeon in chief at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, during a session on disaster preparedness and mass casualties. “When it’s not built on the trauma plan, it can be a nightmare,” he warned.

“Disasters are local. One size [of disaster response] does not fit all. A hurricane in Miami is not like an earthquake in San Francisco or a shooter in Colorado,” which is why each hospital and community needs to devise its own, localized plan. “Surgeons know their community’s organization,” and the vast majority of mass casualty events result in no more patients and are not more daunting than a busy Friday night of injuries at urban trauma centers, Dr. Mattox said. It’s also critical that a hospital leader be in charge at the center and recognize that the hospital’s resources will need to suffice to meet a mass-casualty challenge.

“The ‘cavalry’ will not come over the hill, and even if the cavalry were to arrive, they won’t be credentialed in your state, they won’t know how to deal with your crisis, and they won’t know your local resources. You are the boss.”

Dr. Mattox recommended that interested surgeons get involved with their community’s disaster plan and set up their mass-casualty protocols in advance, but he warned against trying to come up with anything special. “Treat it like you do the Friday night crisis,” he suggested. “Use your routine triage criteria, the way you handle trauma patients all the time, and don’t try to do anything special. If you try to do something special, it always comes back to bite you.”

Although the idea of a disaster and mass casualties may sound daunting, Dr. Mattox noted that history has repeatedly supported the 10% rule: Only 10% of the survivors of a mass-casualty event need hospitalization, and of that 10%, it is only another 10% (1% of the starting population) who need attention in the operating room or ICU. That puts a premium on accurate and effective triage, which initially can be handled by nurses or emergency personnel, and then ultimately by surgeons to identify the small number of patients who truly need immediate surgical attention.

Recent world developments have shown that hospitals handling mass casualties must also think about and guard against a new challenge: the terrorist or shooter who targets the hospital itself. As a consequence, mass-casualty drills at hospitals should include practicing steps to better safeguard the surgical wing at a hospital from attack. This could be as simple as shoving door stops under doors to help keep them securely closed, said Dr. Mattox, who is also a distinguished service professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. He recommended that surgical units rehearse their disaster drills often enough to refine their approaches and make them automatic, but not so often as to numb the staff to an actual event.

Dr. Mattox and his colleagues conduct an annual, 1-day course on medical disaster response.

He had no disclosures aside from serving as program director for an annual course on medical disaster response.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – Surgeons are the logical choice for taking the lead in formulating a hospital plan for dealing with mass casualties, and when doing so they should use their usual trauma-management practices as the cornerstone, Dr. Kenneth L. Mattox recommended at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“The disaster plan is built on the trauma plan, and surgeons are at the heart of it,” said Dr. Mattox, chief of staff and surgeon in chief at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, during a session on disaster preparedness and mass casualties. “When it’s not built on the trauma plan, it can be a nightmare,” he warned.

“Disasters are local. One size [of disaster response] does not fit all. A hurricane in Miami is not like an earthquake in San Francisco or a shooter in Colorado,” which is why each hospital and community needs to devise its own, localized plan. “Surgeons know their community’s organization,” and the vast majority of mass casualty events result in no more patients and are not more daunting than a busy Friday night of injuries at urban trauma centers, Dr. Mattox said. It’s also critical that a hospital leader be in charge at the center and recognize that the hospital’s resources will need to suffice to meet a mass-casualty challenge.

“The ‘cavalry’ will not come over the hill, and even if the cavalry were to arrive, they won’t be credentialed in your state, they won’t know how to deal with your crisis, and they won’t know your local resources. You are the boss.”

Dr. Mattox recommended that interested surgeons get involved with their community’s disaster plan and set up their mass-casualty protocols in advance, but he warned against trying to come up with anything special. “Treat it like you do the Friday night crisis,” he suggested. “Use your routine triage criteria, the way you handle trauma patients all the time, and don’t try to do anything special. If you try to do something special, it always comes back to bite you.”

Although the idea of a disaster and mass casualties may sound daunting, Dr. Mattox noted that history has repeatedly supported the 10% rule: Only 10% of the survivors of a mass-casualty event need hospitalization, and of that 10%, it is only another 10% (1% of the starting population) who need attention in the operating room or ICU. That puts a premium on accurate and effective triage, which initially can be handled by nurses or emergency personnel, and then ultimately by surgeons to identify the small number of patients who truly need immediate surgical attention.

Recent world developments have shown that hospitals handling mass casualties must also think about and guard against a new challenge: the terrorist or shooter who targets the hospital itself. As a consequence, mass-casualty drills at hospitals should include practicing steps to better safeguard the surgical wing at a hospital from attack. This could be as simple as shoving door stops under doors to help keep them securely closed, said Dr. Mattox, who is also a distinguished service professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. He recommended that surgical units rehearse their disaster drills often enough to refine their approaches and make them automatic, but not so often as to numb the staff to an actual event.

Dr. Mattox and his colleagues conduct an annual, 1-day course on medical disaster response.

He had no disclosures aside from serving as program director for an annual course on medical disaster response.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – Surgeons are the logical choice for taking the lead in formulating a hospital plan for dealing with mass casualties, and when doing so they should use their usual trauma-management practices as the cornerstone, Dr. Kenneth L. Mattox recommended at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

“The disaster plan is built on the trauma plan, and surgeons are at the heart of it,” said Dr. Mattox, chief of staff and surgeon in chief at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, during a session on disaster preparedness and mass casualties. “When it’s not built on the trauma plan, it can be a nightmare,” he warned.

“Disasters are local. One size [of disaster response] does not fit all. A hurricane in Miami is not like an earthquake in San Francisco or a shooter in Colorado,” which is why each hospital and community needs to devise its own, localized plan. “Surgeons know their community’s organization,” and the vast majority of mass casualty events result in no more patients and are not more daunting than a busy Friday night of injuries at urban trauma centers, Dr. Mattox said. It’s also critical that a hospital leader be in charge at the center and recognize that the hospital’s resources will need to suffice to meet a mass-casualty challenge.

“The ‘cavalry’ will not come over the hill, and even if the cavalry were to arrive, they won’t be credentialed in your state, they won’t know how to deal with your crisis, and they won’t know your local resources. You are the boss.”

Dr. Mattox recommended that interested surgeons get involved with their community’s disaster plan and set up their mass-casualty protocols in advance, but he warned against trying to come up with anything special. “Treat it like you do the Friday night crisis,” he suggested. “Use your routine triage criteria, the way you handle trauma patients all the time, and don’t try to do anything special. If you try to do something special, it always comes back to bite you.”

Although the idea of a disaster and mass casualties may sound daunting, Dr. Mattox noted that history has repeatedly supported the 10% rule: Only 10% of the survivors of a mass-casualty event need hospitalization, and of that 10%, it is only another 10% (1% of the starting population) who need attention in the operating room or ICU. That puts a premium on accurate and effective triage, which initially can be handled by nurses or emergency personnel, and then ultimately by surgeons to identify the small number of patients who truly need immediate surgical attention.

Recent world developments have shown that hospitals handling mass casualties must also think about and guard against a new challenge: the terrorist or shooter who targets the hospital itself. As a consequence, mass-casualty drills at hospitals should include practicing steps to better safeguard the surgical wing at a hospital from attack. This could be as simple as shoving door stops under doors to help keep them securely closed, said Dr. Mattox, who is also a distinguished service professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. He recommended that surgical units rehearse their disaster drills often enough to refine their approaches and make them automatic, but not so often as to numb the staff to an actual event.

Dr. Mattox and his colleagues conduct an annual, 1-day course on medical disaster response.

He had no disclosures aside from serving as program director for an annual course on medical disaster response.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

STS: Score stratifies risks for isolated tricuspid valve surgery patients

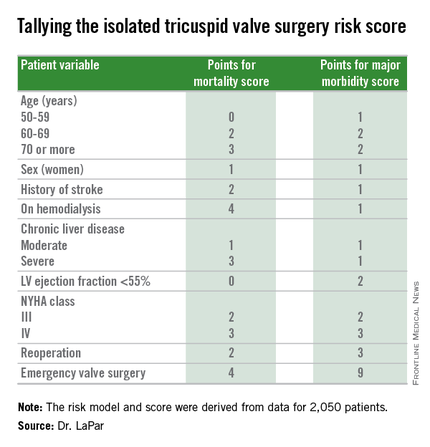

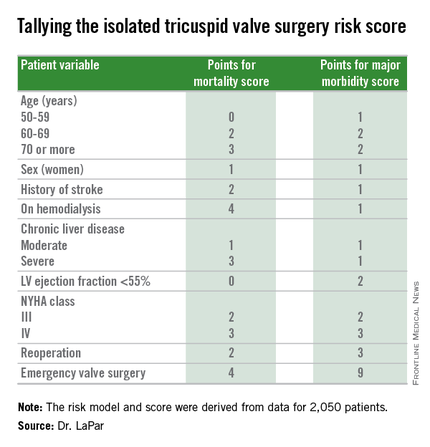

PHOENIX – A team of cardiac surgeons has developed the first clinical risk score for predicting the risk that patients face for operative mortality and postsurgical major morbidity when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

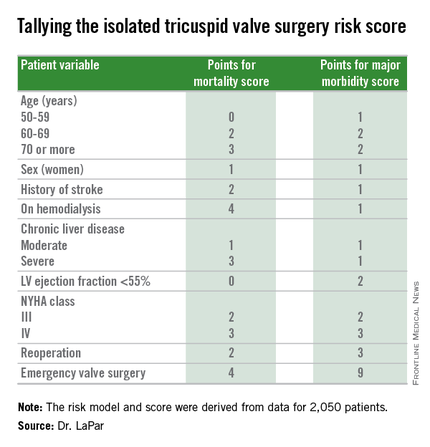

The risk score uses nine easily collected variables, and the derived model discriminates outcomes based on patients who score from 0-10 or more points on both a mortality and a morbidity risk scale, Dr. Damien J. LaPar said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The risk scores allow surgeons to better describe and quantify to patients considering isolated tricuspid valve surgery the risks they face from the operation, and they have already been incorporated into practice at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where Dr. LaPar practices.

“Patients love to better understand their risks. We can provide them with empirical data from a large, heterogeneous population that are better than a surgeon’s gut feeling” about the risks they face, said Dr. LaPar, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University.

Another consequence of having the new risk model and score is that it identified certain key risk factors that are controllable, and thereby, “makes the case for early referrals” for isolated tricuspid valve surgery, Dr. LaPar said in an interview. For example, the risk score shows that patients who are older, on hemodialysis, have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, or require emergency intervention all contribute to worse outcomes, compared with patients who are younger, have better renal function, better cardiac output, or can be treated on a more routine basis.

Many physicians have viewed isolated tricuspid valve surgery as posing similar risks to all patients, with an overall average operative mortality rate of about 10%, he noted. The new risk score model shows that some patients who are younger and healthier have operative mortality rates below 5%, while older and sicker patients have rates that can surpass 20%.

“Our data show a spectrum of risk, and that it is better to operate sooner than later. That is the huge clinical message of these data,” Dr. LaPar said.

Designated discussant Dr. Michael A. Acker noted that the risk score for tricuspid-valve surgery “is a first of its kind and a major contribution.” Dr. Acker is professor of surgery and chief of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He is a consultant to Thoratec and HeartWare.

Dr. LaPar and his associates derived the risk model and score from data collected on 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement at 49 hospitals in Virginia or Michigan during 2002-2014. The data came from databases maintained by the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and by the Michigan Society of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeons, and reported to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The model they developed showed operative mortality rates that ranged from 2%, for patients with a mortality score of zero, to 34% for patients with a score of 10 or more. It further showed major morbidity rates of 13%, for patients with a morbidity score of zero, to 71% for those with a score of 10 or more. Scoring for mortality uses a slightly different system than the scoring for morbidity, so the scores must be calculated individually, and the score totals for a patient can differ for each endpoint. The maximum score is 22 for mortality and 23 for morbidity.

Only 5%-15% of patients undergoing tricuspid valve surgery have an isolated procedure, so a relatively limited number of patients fall into this category, a fact that has in the past limited collection of data from large numbers of patients. The dataset used for this analysis, with 2,050 patients “is one of the largest series collected,” and made possible derivation of a robust risk model and scoring system. Future analysis of even more patients should further improve the model and scoring system.

“These data set the stage for looking at national-level data to further refine the model and make it even more generalizable,” Dr. LaPar said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – A team of cardiac surgeons has developed the first clinical risk score for predicting the risk that patients face for operative mortality and postsurgical major morbidity when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

The risk score uses nine easily collected variables, and the derived model discriminates outcomes based on patients who score from 0-10 or more points on both a mortality and a morbidity risk scale, Dr. Damien J. LaPar said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The risk scores allow surgeons to better describe and quantify to patients considering isolated tricuspid valve surgery the risks they face from the operation, and they have already been incorporated into practice at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where Dr. LaPar practices.

“Patients love to better understand their risks. We can provide them with empirical data from a large, heterogeneous population that are better than a surgeon’s gut feeling” about the risks they face, said Dr. LaPar, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University.

Another consequence of having the new risk model and score is that it identified certain key risk factors that are controllable, and thereby, “makes the case for early referrals” for isolated tricuspid valve surgery, Dr. LaPar said in an interview. For example, the risk score shows that patients who are older, on hemodialysis, have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, or require emergency intervention all contribute to worse outcomes, compared with patients who are younger, have better renal function, better cardiac output, or can be treated on a more routine basis.

Many physicians have viewed isolated tricuspid valve surgery as posing similar risks to all patients, with an overall average operative mortality rate of about 10%, he noted. The new risk score model shows that some patients who are younger and healthier have operative mortality rates below 5%, while older and sicker patients have rates that can surpass 20%.

“Our data show a spectrum of risk, and that it is better to operate sooner than later. That is the huge clinical message of these data,” Dr. LaPar said.

Designated discussant Dr. Michael A. Acker noted that the risk score for tricuspid-valve surgery “is a first of its kind and a major contribution.” Dr. Acker is professor of surgery and chief of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He is a consultant to Thoratec and HeartWare.

Dr. LaPar and his associates derived the risk model and score from data collected on 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement at 49 hospitals in Virginia or Michigan during 2002-2014. The data came from databases maintained by the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and by the Michigan Society of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeons, and reported to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The model they developed showed operative mortality rates that ranged from 2%, for patients with a mortality score of zero, to 34% for patients with a score of 10 or more. It further showed major morbidity rates of 13%, for patients with a morbidity score of zero, to 71% for those with a score of 10 or more. Scoring for mortality uses a slightly different system than the scoring for morbidity, so the scores must be calculated individually, and the score totals for a patient can differ for each endpoint. The maximum score is 22 for mortality and 23 for morbidity.

Only 5%-15% of patients undergoing tricuspid valve surgery have an isolated procedure, so a relatively limited number of patients fall into this category, a fact that has in the past limited collection of data from large numbers of patients. The dataset used for this analysis, with 2,050 patients “is one of the largest series collected,” and made possible derivation of a robust risk model and scoring system. Future analysis of even more patients should further improve the model and scoring system.

“These data set the stage for looking at national-level data to further refine the model and make it even more generalizable,” Dr. LaPar said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – A team of cardiac surgeons has developed the first clinical risk score for predicting the risk that patients face for operative mortality and postsurgical major morbidity when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement.

The risk score uses nine easily collected variables, and the derived model discriminates outcomes based on patients who score from 0-10 or more points on both a mortality and a morbidity risk scale, Dr. Damien J. LaPar said at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The risk scores allow surgeons to better describe and quantify to patients considering isolated tricuspid valve surgery the risks they face from the operation, and they have already been incorporated into practice at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, where Dr. LaPar practices.

“Patients love to better understand their risks. We can provide them with empirical data from a large, heterogeneous population that are better than a surgeon’s gut feeling” about the risks they face, said Dr. LaPar, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the University.

Another consequence of having the new risk model and score is that it identified certain key risk factors that are controllable, and thereby, “makes the case for early referrals” for isolated tricuspid valve surgery, Dr. LaPar said in an interview. For example, the risk score shows that patients who are older, on hemodialysis, have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, or require emergency intervention all contribute to worse outcomes, compared with patients who are younger, have better renal function, better cardiac output, or can be treated on a more routine basis.

Many physicians have viewed isolated tricuspid valve surgery as posing similar risks to all patients, with an overall average operative mortality rate of about 10%, he noted. The new risk score model shows that some patients who are younger and healthier have operative mortality rates below 5%, while older and sicker patients have rates that can surpass 20%.

“Our data show a spectrum of risk, and that it is better to operate sooner than later. That is the huge clinical message of these data,” Dr. LaPar said.

Designated discussant Dr. Michael A. Acker noted that the risk score for tricuspid-valve surgery “is a first of its kind and a major contribution.” Dr. Acker is professor of surgery and chief of cardiovascular surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He is a consultant to Thoratec and HeartWare.

Dr. LaPar and his associates derived the risk model and score from data collected on 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve repair or replacement at 49 hospitals in Virginia or Michigan during 2002-2014. The data came from databases maintained by the Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative and by the Michigan Society of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgeons, and reported to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The model they developed showed operative mortality rates that ranged from 2%, for patients with a mortality score of zero, to 34% for patients with a score of 10 or more. It further showed major morbidity rates of 13%, for patients with a morbidity score of zero, to 71% for those with a score of 10 or more. Scoring for mortality uses a slightly different system than the scoring for morbidity, so the scores must be calculated individually, and the score totals for a patient can differ for each endpoint. The maximum score is 22 for mortality and 23 for morbidity.

Only 5%-15% of patients undergoing tricuspid valve surgery have an isolated procedure, so a relatively limited number of patients fall into this category, a fact that has in the past limited collection of data from large numbers of patients. The dataset used for this analysis, with 2,050 patients “is one of the largest series collected,” and made possible derivation of a robust risk model and scoring system. Future analysis of even more patients should further improve the model and scoring system.

“These data set the stage for looking at national-level data to further refine the model and make it even more generalizable,” Dr. LaPar said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A risk-scoring system estimates a patient’s mortality and morbidity risk when undergoing isolated tricuspid valve surgery.

Major finding: The scoring system discriminated mortality risk from 2% to 34%, and major morbidity risk from 13% to 71%.

Data source: Analysis of 2,050 patients who underwent isolated tricuspid valve surgery in the STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database.

Disclosures: Dr. LaPar had no disclosures.

STS: Hybrid thoracic suite leverages CT’s imaging sensitivity

PHOENIX – Using CT imaging to detect lung cancers in people at high risk for developing it has made it possible to find small tumors with substantially increased sensitivity than is possible with radiography, However, this approach has posed a new challenge to thoracic surgeons: How to visualize these nodules – subcentimeter and nonpalpable – for biopsy or for resection?

The answer may be the hybrid thoracic operating room developed by Dr. Kazuhiro Yasufuku and his associates at Toronto General Hospital, a novel surgical suite that he described at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Dr. Yasufuku and his team began using the hybrid operating room on an investigational basis in 2013 and have now done about 50 cases as part of several research protocols. The trials address the feasibility of resection, biopsy, and nodule localization, as well as whether the hybrid approach reduces the amount of radiation exposure to both patients and to the surgical team, he said. They plan to report some of their initial results later this year.

The Toronto group assembled the hybrid array of equipment into a single operating room that includes both a dual-source, dual-energy CT scanner and a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, equipment for minimally invasive procedures including video-assisted thoracoscopic and robotic surgery, and advanced endoscopic technology including endobronchial ultrasound and navigational bronchoscopy. “We use innovative methods that we already know about, but bring them all together” within a single space, Dr. Yasufuku explained. “Rather than having patients go to several locations, we can do everything at the same time in one room.”

Perhaps the most novel aspect of this operating room is inclusion of a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, which uses mobile, flat CT-imaging panels that overcome the limitations of a conventional, fixed CT scanner. “They scan the patient and then we can retract them and get them out of the way” to better facilitate surgery, he said in an interview.

“We do not have a culture in thoracic surgery of using imaging during surgery,” said Dr. Yasufuku, director of the interventional thoracic surgery program at the University of Toronto. Hybrid operating rooms using noninvasive or minimally invasive equipment and procedures have become commonplace for cardiovascular surgeons and cardiac interventionalists, but this approach has generally not yet been applied to thoracic surgery for cancer, in large part because of the imaging limitations, he said. “It is difficult to perform video-assisted thorascopic surgery using fixed CT.”

Bronchoscopic technologies provide additional, important tools for minimally invasive thoracic surgery. “We use the hybrid operating room to mark small [nonpalpable] lesions.” One approach to marking is to place a microcoil within the nodule with a percutaneous needle. Another approach is to tag the nodule with a fluorescent dye using navigational bronchoscopy.

Dr. Yasufuku also emphasized that the hybrid operating room will also be valuable when new, minimally invasive, nonsurgical therapeutic options for treatment of lung cancer become available in the near future.

Dr. Yasufuku said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – Using CT imaging to detect lung cancers in people at high risk for developing it has made it possible to find small tumors with substantially increased sensitivity than is possible with radiography, However, this approach has posed a new challenge to thoracic surgeons: How to visualize these nodules – subcentimeter and nonpalpable – for biopsy or for resection?

The answer may be the hybrid thoracic operating room developed by Dr. Kazuhiro Yasufuku and his associates at Toronto General Hospital, a novel surgical suite that he described at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Dr. Yasufuku and his team began using the hybrid operating room on an investigational basis in 2013 and have now done about 50 cases as part of several research protocols. The trials address the feasibility of resection, biopsy, and nodule localization, as well as whether the hybrid approach reduces the amount of radiation exposure to both patients and to the surgical team, he said. They plan to report some of their initial results later this year.

The Toronto group assembled the hybrid array of equipment into a single operating room that includes both a dual-source, dual-energy CT scanner and a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, equipment for minimally invasive procedures including video-assisted thoracoscopic and robotic surgery, and advanced endoscopic technology including endobronchial ultrasound and navigational bronchoscopy. “We use innovative methods that we already know about, but bring them all together” within a single space, Dr. Yasufuku explained. “Rather than having patients go to several locations, we can do everything at the same time in one room.”

Perhaps the most novel aspect of this operating room is inclusion of a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, which uses mobile, flat CT-imaging panels that overcome the limitations of a conventional, fixed CT scanner. “They scan the patient and then we can retract them and get them out of the way” to better facilitate surgery, he said in an interview.

“We do not have a culture in thoracic surgery of using imaging during surgery,” said Dr. Yasufuku, director of the interventional thoracic surgery program at the University of Toronto. Hybrid operating rooms using noninvasive or minimally invasive equipment and procedures have become commonplace for cardiovascular surgeons and cardiac interventionalists, but this approach has generally not yet been applied to thoracic surgery for cancer, in large part because of the imaging limitations, he said. “It is difficult to perform video-assisted thorascopic surgery using fixed CT.”

Bronchoscopic technologies provide additional, important tools for minimally invasive thoracic surgery. “We use the hybrid operating room to mark small [nonpalpable] lesions.” One approach to marking is to place a microcoil within the nodule with a percutaneous needle. Another approach is to tag the nodule with a fluorescent dye using navigational bronchoscopy.

Dr. Yasufuku also emphasized that the hybrid operating room will also be valuable when new, minimally invasive, nonsurgical therapeutic options for treatment of lung cancer become available in the near future.

Dr. Yasufuku said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHOENIX – Using CT imaging to detect lung cancers in people at high risk for developing it has made it possible to find small tumors with substantially increased sensitivity than is possible with radiography, However, this approach has posed a new challenge to thoracic surgeons: How to visualize these nodules – subcentimeter and nonpalpable – for biopsy or for resection?

The answer may be the hybrid thoracic operating room developed by Dr. Kazuhiro Yasufuku and his associates at Toronto General Hospital, a novel surgical suite that he described at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Dr. Yasufuku and his team began using the hybrid operating room on an investigational basis in 2013 and have now done about 50 cases as part of several research protocols. The trials address the feasibility of resection, biopsy, and nodule localization, as well as whether the hybrid approach reduces the amount of radiation exposure to both patients and to the surgical team, he said. They plan to report some of their initial results later this year.

The Toronto group assembled the hybrid array of equipment into a single operating room that includes both a dual-source, dual-energy CT scanner and a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, equipment for minimally invasive procedures including video-assisted thoracoscopic and robotic surgery, and advanced endoscopic technology including endobronchial ultrasound and navigational bronchoscopy. “We use innovative methods that we already know about, but bring them all together” within a single space, Dr. Yasufuku explained. “Rather than having patients go to several locations, we can do everything at the same time in one room.”

Perhaps the most novel aspect of this operating room is inclusion of a robotic cone-beam CT scanner, which uses mobile, flat CT-imaging panels that overcome the limitations of a conventional, fixed CT scanner. “They scan the patient and then we can retract them and get them out of the way” to better facilitate surgery, he said in an interview.

“We do not have a culture in thoracic surgery of using imaging during surgery,” said Dr. Yasufuku, director of the interventional thoracic surgery program at the University of Toronto. Hybrid operating rooms using noninvasive or minimally invasive equipment and procedures have become commonplace for cardiovascular surgeons and cardiac interventionalists, but this approach has generally not yet been applied to thoracic surgery for cancer, in large part because of the imaging limitations, he said. “It is difficult to perform video-assisted thorascopic surgery using fixed CT.”

Bronchoscopic technologies provide additional, important tools for minimally invasive thoracic surgery. “We use the hybrid operating room to mark small [nonpalpable] lesions.” One approach to marking is to place a microcoil within the nodule with a percutaneous needle. Another approach is to tag the nodule with a fluorescent dye using navigational bronchoscopy.

Dr. Yasufuku also emphasized that the hybrid operating room will also be valuable when new, minimally invasive, nonsurgical therapeutic options for treatment of lung cancer become available in the near future.

Dr. Yasufuku said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE STS ANNUAL MEETING

West African Ebola–virus transmission ends, then resumes

A day after the World Health Organization declared on Jan. 14 that no known cases of Ebola-virus transmission or active infection had been identified in West Africa for more than 42 days, the agency revealed the existence of a new, single case of Ebola-virus infection in Sierra Leone.

The appearance of the new case highlighted the challenges that remain in fully stamping out the West African Ebola–virus outbreak. The crisis began in December 2013, raged throughout 2014, and only wound down toward a sputtering halt near the end of 2015.

When Dr. Rick Brennan, the World Health Organization (WHO) director for Emergency Risk Management and Humanitarian Response, announced during a press conference on Jan. 14, “the end of Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa” and “the first time since 2014 that all know chains of transmission have stopped in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone,” he and his colleague, Dr. Peter Graaff, also underscored the ongoing risk for sporadic, isolated cases. The main threat for new cases comes from men who survived Ebola-virus infection but harbored significant quantities of infectious virus in various body fluids and tissues, including their semen, for a period of about 1 year following their infection.

During the press conference, both Dr. Brennan and Dr. Graaff spoke of a new, strengthened infrastructure that WHO had placed in West Africa to better monitor and react quickly to these flare-up cases – the mechanism that led to quick identification of the new Sierra Leone case.

“I think you’ll see a more responsive and effective WHO,” said Dr. Graaff, WHO’s director of Ebola response. “We will use the Ebola experience to be more agile, more operational, and better able to react more quickly to whatever future problems come our way,” including infectious-disease outbreaks by pathogens other than Ebola virus.

The 42-day period without new infections that had led to the announcement of an end to Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa represents two 21-day incubation cycles for the virus. Until the Sierra Leone case reported on Jan. 15, the last confirmed West African case had been identified in Liberia in mid-November. Liberia had previously been declared Ebola free in last May, but four new, isolated infections appeared subsequent to that transmitted by Ebola-infection survivors who still harbored infectious virus. Before the Jan. 15 case, an additional three such flare-ups occurred in Sierra Leone and another three in Guinea since last March, Dr. Brennan said.

The current tally on the West African Ebola outbreak stands at roughly 28,500 confirmed cases identified, and about 11,300 deaths. Nearly three-quarters of infections occurred during 2014. The case fatality rate at the start of the outbreak ran about 80%, noted Dr. Graaff, but gradually fell as infected patients began receiving better care. Near the outbreak’s end, the case fatality rate stood at roughly 35%, when most patients were receiving optimal clinical care.

WHO staffers are maintaining close surveillance of people who recently survived Ebola-virus infection so that they can identify and isolate any new infections. WHO personnel have also counseled these survivors on the risk they pose for potential transmission, primarily by unprotected sex by men for up to 12 months following the end of active infection. The WHO also plans to launch an investigational protocol to vaccinate sexual partners and other close contacts of adult male survivors with an as-yet unapproved Ebola vaccine to further reduce risk of new infections.

“The WHO and world community reacted slowly at the start of the Ebola outbreak” in early 2014, admitted Dr. Brennan. “Without question, the disease got away from us. In retrospect, there were a number of things that we should have done better and sooner,” he said. “We have done a lot of soul-searching and we [at WHO] have identified a number of weaknesses in our structures and systems. We have already taken several important steps, and we are undergoing major reforms of our emergency operations. I think you’ll see a much more effective WHO in the future.”

Reform of WHO systems for infection prevention and control “will be much better able to detect new cases, not only of Ebola, but of other important diseases,” said Dr. Graaff.

The United States is also strengthening its health screening and monitoring system for travelers coming from affected countries and improving its hospital preparedness to manage cases, said Alice C. Hill, senior adviser for preparedness and resilience at the National Security Council and special assistant to President Obama. Hill, who spoke Jan. 6 at the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise stakeholders workshop, acknowledged that challenges still exist that must be addressed, including the development of safe and effective diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines for existing infectious diseases such as influenza and more emerging threats such as Ebola or MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), developing accurate disease forecasting capabilities to predict what will be the next threat, building rapid clinical trial networks and manufacturing capabilities, and the abilities for mass dispensing of medical countermeasures.

Gregory Twachtman also contributed to this story.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

A day after the World Health Organization declared on Jan. 14 that no known cases of Ebola-virus transmission or active infection had been identified in West Africa for more than 42 days, the agency revealed the existence of a new, single case of Ebola-virus infection in Sierra Leone.

The appearance of the new case highlighted the challenges that remain in fully stamping out the West African Ebola–virus outbreak. The crisis began in December 2013, raged throughout 2014, and only wound down toward a sputtering halt near the end of 2015.

When Dr. Rick Brennan, the World Health Organization (WHO) director for Emergency Risk Management and Humanitarian Response, announced during a press conference on Jan. 14, “the end of Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa” and “the first time since 2014 that all know chains of transmission have stopped in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone,” he and his colleague, Dr. Peter Graaff, also underscored the ongoing risk for sporadic, isolated cases. The main threat for new cases comes from men who survived Ebola-virus infection but harbored significant quantities of infectious virus in various body fluids and tissues, including their semen, for a period of about 1 year following their infection.

During the press conference, both Dr. Brennan and Dr. Graaff spoke of a new, strengthened infrastructure that WHO had placed in West Africa to better monitor and react quickly to these flare-up cases – the mechanism that led to quick identification of the new Sierra Leone case.

“I think you’ll see a more responsive and effective WHO,” said Dr. Graaff, WHO’s director of Ebola response. “We will use the Ebola experience to be more agile, more operational, and better able to react more quickly to whatever future problems come our way,” including infectious-disease outbreaks by pathogens other than Ebola virus.

The 42-day period without new infections that had led to the announcement of an end to Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa represents two 21-day incubation cycles for the virus. Until the Sierra Leone case reported on Jan. 15, the last confirmed West African case had been identified in Liberia in mid-November. Liberia had previously been declared Ebola free in last May, but four new, isolated infections appeared subsequent to that transmitted by Ebola-infection survivors who still harbored infectious virus. Before the Jan. 15 case, an additional three such flare-ups occurred in Sierra Leone and another three in Guinea since last March, Dr. Brennan said.

The current tally on the West African Ebola outbreak stands at roughly 28,500 confirmed cases identified, and about 11,300 deaths. Nearly three-quarters of infections occurred during 2014. The case fatality rate at the start of the outbreak ran about 80%, noted Dr. Graaff, but gradually fell as infected patients began receiving better care. Near the outbreak’s end, the case fatality rate stood at roughly 35%, when most patients were receiving optimal clinical care.

WHO staffers are maintaining close surveillance of people who recently survived Ebola-virus infection so that they can identify and isolate any new infections. WHO personnel have also counseled these survivors on the risk they pose for potential transmission, primarily by unprotected sex by men for up to 12 months following the end of active infection. The WHO also plans to launch an investigational protocol to vaccinate sexual partners and other close contacts of adult male survivors with an as-yet unapproved Ebola vaccine to further reduce risk of new infections.

“The WHO and world community reacted slowly at the start of the Ebola outbreak” in early 2014, admitted Dr. Brennan. “Without question, the disease got away from us. In retrospect, there were a number of things that we should have done better and sooner,” he said. “We have done a lot of soul-searching and we [at WHO] have identified a number of weaknesses in our structures and systems. We have already taken several important steps, and we are undergoing major reforms of our emergency operations. I think you’ll see a much more effective WHO in the future.”

Reform of WHO systems for infection prevention and control “will be much better able to detect new cases, not only of Ebola, but of other important diseases,” said Dr. Graaff.

The United States is also strengthening its health screening and monitoring system for travelers coming from affected countries and improving its hospital preparedness to manage cases, said Alice C. Hill, senior adviser for preparedness and resilience at the National Security Council and special assistant to President Obama. Hill, who spoke Jan. 6 at the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise stakeholders workshop, acknowledged that challenges still exist that must be addressed, including the development of safe and effective diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines for existing infectious diseases such as influenza and more emerging threats such as Ebola or MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), developing accurate disease forecasting capabilities to predict what will be the next threat, building rapid clinical trial networks and manufacturing capabilities, and the abilities for mass dispensing of medical countermeasures.

Gregory Twachtman also contributed to this story.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

A day after the World Health Organization declared on Jan. 14 that no known cases of Ebola-virus transmission or active infection had been identified in West Africa for more than 42 days, the agency revealed the existence of a new, single case of Ebola-virus infection in Sierra Leone.

The appearance of the new case highlighted the challenges that remain in fully stamping out the West African Ebola–virus outbreak. The crisis began in December 2013, raged throughout 2014, and only wound down toward a sputtering halt near the end of 2015.

When Dr. Rick Brennan, the World Health Organization (WHO) director for Emergency Risk Management and Humanitarian Response, announced during a press conference on Jan. 14, “the end of Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa” and “the first time since 2014 that all know chains of transmission have stopped in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone,” he and his colleague, Dr. Peter Graaff, also underscored the ongoing risk for sporadic, isolated cases. The main threat for new cases comes from men who survived Ebola-virus infection but harbored significant quantities of infectious virus in various body fluids and tissues, including their semen, for a period of about 1 year following their infection.

During the press conference, both Dr. Brennan and Dr. Graaff spoke of a new, strengthened infrastructure that WHO had placed in West Africa to better monitor and react quickly to these flare-up cases – the mechanism that led to quick identification of the new Sierra Leone case.

“I think you’ll see a more responsive and effective WHO,” said Dr. Graaff, WHO’s director of Ebola response. “We will use the Ebola experience to be more agile, more operational, and better able to react more quickly to whatever future problems come our way,” including infectious-disease outbreaks by pathogens other than Ebola virus.

The 42-day period without new infections that had led to the announcement of an end to Ebola-virus transmission in West Africa represents two 21-day incubation cycles for the virus. Until the Sierra Leone case reported on Jan. 15, the last confirmed West African case had been identified in Liberia in mid-November. Liberia had previously been declared Ebola free in last May, but four new, isolated infections appeared subsequent to that transmitted by Ebola-infection survivors who still harbored infectious virus. Before the Jan. 15 case, an additional three such flare-ups occurred in Sierra Leone and another three in Guinea since last March, Dr. Brennan said.

The current tally on the West African Ebola outbreak stands at roughly 28,500 confirmed cases identified, and about 11,300 deaths. Nearly three-quarters of infections occurred during 2014. The case fatality rate at the start of the outbreak ran about 80%, noted Dr. Graaff, but gradually fell as infected patients began receiving better care. Near the outbreak’s end, the case fatality rate stood at roughly 35%, when most patients were receiving optimal clinical care.

WHO staffers are maintaining close surveillance of people who recently survived Ebola-virus infection so that they can identify and isolate any new infections. WHO personnel have also counseled these survivors on the risk they pose for potential transmission, primarily by unprotected sex by men for up to 12 months following the end of active infection. The WHO also plans to launch an investigational protocol to vaccinate sexual partners and other close contacts of adult male survivors with an as-yet unapproved Ebola vaccine to further reduce risk of new infections.

“The WHO and world community reacted slowly at the start of the Ebola outbreak” in early 2014, admitted Dr. Brennan. “Without question, the disease got away from us. In retrospect, there were a number of things that we should have done better and sooner,” he said. “We have done a lot of soul-searching and we [at WHO] have identified a number of weaknesses in our structures and systems. We have already taken several important steps, and we are undergoing major reforms of our emergency operations. I think you’ll see a much more effective WHO in the future.”

Reform of WHO systems for infection prevention and control “will be much better able to detect new cases, not only of Ebola, but of other important diseases,” said Dr. Graaff.

The United States is also strengthening its health screening and monitoring system for travelers coming from affected countries and improving its hospital preparedness to manage cases, said Alice C. Hill, senior adviser for preparedness and resilience at the National Security Council and special assistant to President Obama. Hill, who spoke Jan. 6 at the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise stakeholders workshop, acknowledged that challenges still exist that must be addressed, including the development of safe and effective diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines for existing infectious diseases such as influenza and more emerging threats such as Ebola or MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), developing accurate disease forecasting capabilities to predict what will be the next threat, building rapid clinical trial networks and manufacturing capabilities, and the abilities for mass dispensing of medical countermeasures.

Gregory Twachtman also contributed to this story.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AES: Seizure freedom attainable for most epilepsy patients

PHILADELPHIA - Fully optimized antiepilepsy therapy that tries at least a couple of well-chosen and properly dosed antiseizure drugs as well as follow-up with nondrug options for patients who are unresponsive to pharmaceuticals seems able to render about 80%-90% of epilepsy patients seizure free, Dr. Cynthia L. Harden said while summing up a session on epilepsy therapy at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Finding an appropriate and effective treatment for each epilepsy patient can be “labor intensive and expensive”; it depends in part on a patient’s mood, psychosocial profile, and willingness to comply with treatment; and it often needs the multidisciplinary expertise found at epilepsy centers. But the optimistic message from contemporary seizure-management is that by using a drug or two and in selected patients surgery, diet, or an implanted device, the vast majority of epilepsy patients can become seizure free, noted Dr. Harden, system director of clinical epilepsy services at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York and cochair of the session.

“How many of your uncontrolled patients can become seizure free with more vigilance and tender loving care?” she asked the large audience as she concluded the session. A significant fraction of uncontrolled patients become seizure free when their drug dosage is increased, another drug is substituted or added, their compliance improves, their depression diminishes, or a patient’s understanding of their epilepsy and treatment increases through education, Dr. Harden said.

Drugs remain the cornerstone of seizure control for epilepsy patients, with at least 22 agents now available for epilepsy treatment, including 13 with U.S. or European (or both) approval for initial monotherapy of epilepsy. In addition, study results have shown several agents – carbamazepine, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, and zonisamide – to be more or less equally effective for treating newly diagnosed focal epilepsy, which means that clinicians must also consider factors beyond just efficacy, such as adverse effects, impact on a specific patient’s comorbidities, interactions with other drugs a patient takes, and ease of use and cost, said Dr. Emilio Perucca, a neurologist and professor of pharmacology at the University of Pavia (Italy). In general, newer antiepilepsy drugs have not been more effective than older drugs, he noted.

Another feature of drug treatment is that more is usually not better. “Most patients do not need the highest tolerated dosage,” he said, and minimizing dosages to the lowest effective level helps minimize adverse effects. On the other hand, an antiepilepsy drug needs to be administered at an adequate dosage before concluding that it is ineffective for a patient.

Although a majority of patients respond to the first or second antiepilepsy agent they receive, drugs can’t render all patients seizure free. Results from several reported cohorts show that about 45% of patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy respond well to the first drug they receive and about 13% become seizure free on a second drug. After that, the response rates fall off sharply, with roughly 5% of patients responding to a third drug or drug combinations, said Dr. Patrick Kwan, professor and chairman of neurology at the University of Melbourne and head of epilepsy at Royal Melbourne Hospital. “Once a patient has failed two drugs, even if they become seizure free on a subsequent drug, there is a higher rate of relapse,” Dr. Kwan noted.

In general, 60%-65% of newly diagnosed epilepsy patients become seizure free with drug monotherapy, Dr. Kwan summarized. Epilepsy patients who fail to fully respond to the first two antiepilepsy drugs they receive need “prompt” referral to an epilepsy center. A “substantial proportion” of patients like this can become seizure free by further optimization of the dosage they receive or by addressing compliance issues, Dr. Kwan said. In addition, some patients achieve full or partial seizure freedom through multidrug treatment or with other treatments.

Two-drug combinations have generally been more effective than combinations with three or more drugs, said Dr. Josiane LaJoie, a pediatric neurologist at New York University. “Using three or more drugs probably won’t lead to better control, just more adverse events,” she cautioned. Many published study results have documented successful two-drug combinations, such as lamotrigine and valproate, and valproate and clobazam, to name just two combinations. In addition to looking at combinations with successful track records in published studies, she highlighted the importance of combining drugs with distinct mechanisms of action and avoiding combing drugs with similar adverse-event profiles. Combinations also need to be tailored to each patient’s clinical characteristics, taking possible drug-drug interactions into account, Dr. LaJoie said.

When drug treatment fails to produce seizure freedom, other options are resective or ablative surgery, diet, or a neurostimulation implant. “At no time in history have we had as many nonpharmacologic treatment options as we have today,” said Dr. Christopher T. Skidmore, a neurologist in the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. “With diet or neurostimulation, you get seizure reduction without the adverse effects of addition additional drugs.”

Study results with three different diets indicate that they can each produce a roughly 50% cut in seizure rate in about half the patients who adhere to the diet. The ketogenic diet has the longest track record, but with a 90% fat content, it is notoriously difficult to stick with and requires that patients eat meals that often preclude eating with friends or family members or away from home. Adhering to a modified Atkins diet or a low glycemic load diet seems about as effective as a ketogenic diet while offering more food flexibility and a range of foods more compatible with group meals or meals outside the home, Dr. Skidmore said.

Even though the modified Atkins and low glycemic load diets offer somewhat more flexibility, both remain a “paradigm shift in food consumption,” compared with what most Americans eat, and when compliance is poor they don’t work. “Diet doesn’t work when people cheat,” Dr. Skidmore noted.

Three forms of nerve stimulation have also shown efficacy for seizure reduction, he said: vagal nerve stimulation, responsive neurostimulation, and deep brain stimulation of the anterior nucleus of the thalamus. “All three devices have proven efficacy,” he noted. “Neurostimulation offers an alternative to medical therapy that does not require daily effort and compliance.”

Discussions with patients about diet, neurostimulation, and surgery options allow each patient to decide whether one or more of these might be a good option. “It takes a certain patient to follow a diet or want an implant,” he said. “There is no one right choice. You need to educate patients and help them make their choice,” Dr. Skidmore advised.

Dr. Harmon had no disclosures. Dr. Perucca has served as a consultant to and received honoraria from Biopharma Solutions, GW Pharma, Takeda, Sun Pharma, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Kwan has been a consultant to Eisai and Novartis and has received research funding from UCB. Dr. LaJoie had no disclosures. Dr. Skidmore has been a consultant to Supernus and a site principal investigator for NeuroPace.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA - Fully optimized antiepilepsy therapy that tries at least a couple of well-chosen and properly dosed antiseizure drugs as well as follow-up with nondrug options for patients who are unresponsive to pharmaceuticals seems able to render about 80%-90% of epilepsy patients seizure free, Dr. Cynthia L. Harden said while summing up a session on epilepsy therapy at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Finding an appropriate and effective treatment for each epilepsy patient can be “labor intensive and expensive”; it depends in part on a patient’s mood, psychosocial profile, and willingness to comply with treatment; and it often needs the multidisciplinary expertise found at epilepsy centers. But the optimistic message from contemporary seizure-management is that by using a drug or two and in selected patients surgery, diet, or an implanted device, the vast majority of epilepsy patients can become seizure free, noted Dr. Harden, system director of clinical epilepsy services at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York and cochair of the session.

“How many of your uncontrolled patients can become seizure free with more vigilance and tender loving care?” she asked the large audience as she concluded the session. A significant fraction of uncontrolled patients become seizure free when their drug dosage is increased, another drug is substituted or added, their compliance improves, their depression diminishes, or a patient’s understanding of their epilepsy and treatment increases through education, Dr. Harden said.

Drugs remain the cornerstone of seizure control for epilepsy patients, with at least 22 agents now available for epilepsy treatment, including 13 with U.S. or European (or both) approval for initial monotherapy of epilepsy. In addition, study results have shown several agents – carbamazepine, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, and zonisamide – to be more or less equally effective for treating newly diagnosed focal epilepsy, which means that clinicians must also consider factors beyond just efficacy, such as adverse effects, impact on a specific patient’s comorbidities, interactions with other drugs a patient takes, and ease of use and cost, said Dr. Emilio Perucca, a neurologist and professor of pharmacology at the University of Pavia (Italy). In general, newer antiepilepsy drugs have not been more effective than older drugs, he noted.

Another feature of drug treatment is that more is usually not better. “Most patients do not need the highest tolerated dosage,” he said, and minimizing dosages to the lowest effective level helps minimize adverse effects. On the other hand, an antiepilepsy drug needs to be administered at an adequate dosage before concluding that it is ineffective for a patient.

Although a majority of patients respond to the first or second antiepilepsy agent they receive, drugs can’t render all patients seizure free. Results from several reported cohorts show that about 45% of patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy respond well to the first drug they receive and about 13% become seizure free on a second drug. After that, the response rates fall off sharply, with roughly 5% of patients responding to a third drug or drug combinations, said Dr. Patrick Kwan, professor and chairman of neurology at the University of Melbourne and head of epilepsy at Royal Melbourne Hospital. “Once a patient has failed two drugs, even if they become seizure free on a subsequent drug, there is a higher rate of relapse,” Dr. Kwan noted.

In general, 60%-65% of newly diagnosed epilepsy patients become seizure free with drug monotherapy, Dr. Kwan summarized. Epilepsy patients who fail to fully respond to the first two antiepilepsy drugs they receive need “prompt” referral to an epilepsy center. A “substantial proportion” of patients like this can become seizure free by further optimization of the dosage they receive or by addressing compliance issues, Dr. Kwan said. In addition, some patients achieve full or partial seizure freedom through multidrug treatment or with other treatments.

Two-drug combinations have generally been more effective than combinations with three or more drugs, said Dr. Josiane LaJoie, a pediatric neurologist at New York University. “Using three or more drugs probably won’t lead to better control, just more adverse events,” she cautioned. Many published study results have documented successful two-drug combinations, such as lamotrigine and valproate, and valproate and clobazam, to name just two combinations. In addition to looking at combinations with successful track records in published studies, she highlighted the importance of combining drugs with distinct mechanisms of action and avoiding combing drugs with similar adverse-event profiles. Combinations also need to be tailored to each patient’s clinical characteristics, taking possible drug-drug interactions into account, Dr. LaJoie said.