User login

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

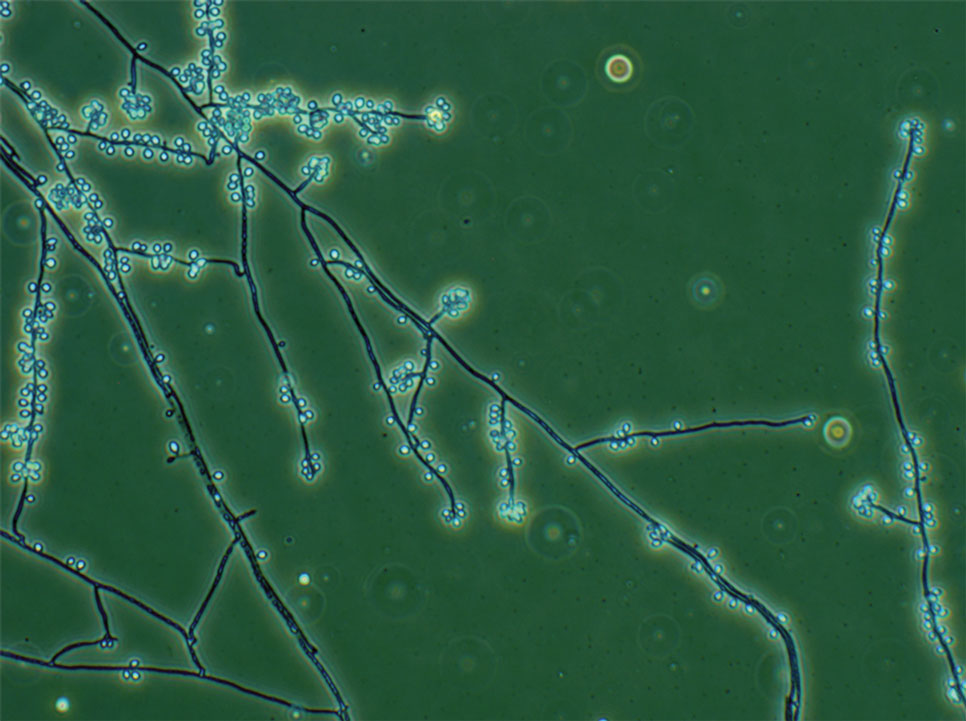

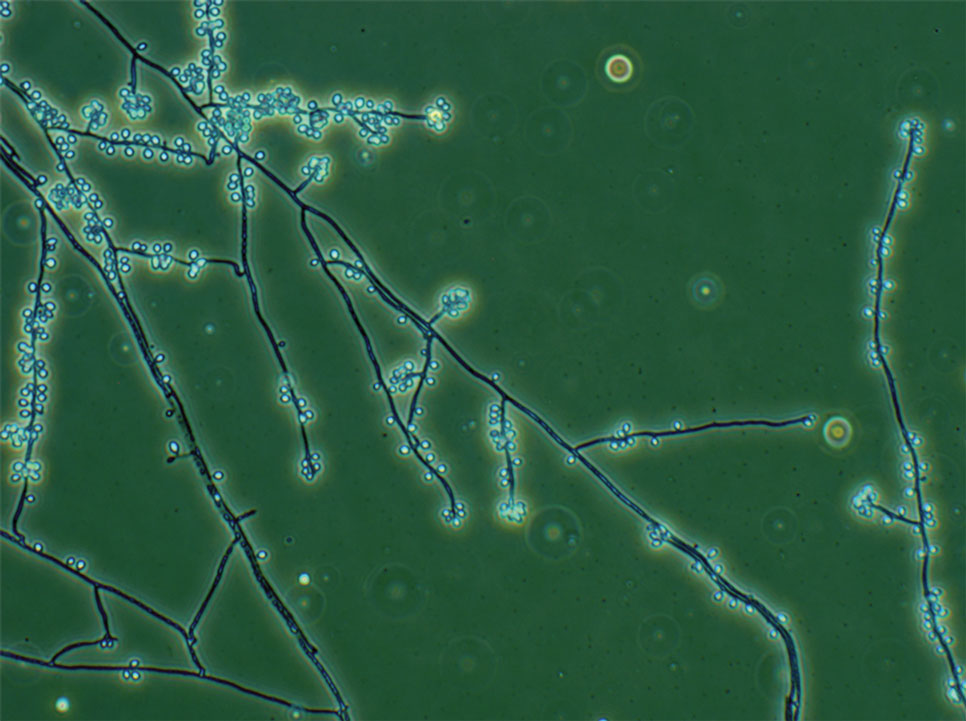

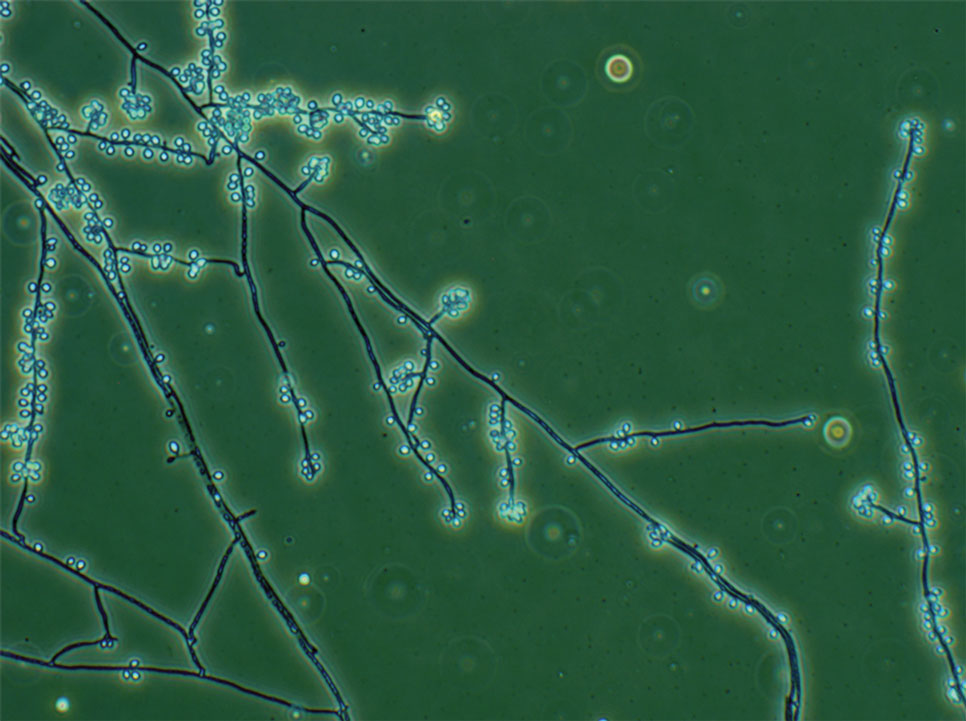

Candida is a common commensal organism of human skin and mucous membranes. Candidiasis of the skin and nails is caused by overgrowth of Candida species due to excess skin moisture, skin barrier disruption, or immunosuppression. Candidiasis of the skin manifests as red, moist, itchy patches that develop particularly in skin folds. Nail involvement is associated with onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and subungual debris.1 Data on the prevalence of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and treatment practices of candidiasis of the skin and nails using data from 2 large US health insurance claims databases.

Methods

We used the 2023 Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases) to identify outpatients with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code B37.2 for candidiasis of the skin and nails. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases include health insurance claims data submitted by large employers and health plans for more than 19 million patients throughout the United States, and the Multi-State Medicaid database includes similar data from more than 5 million patients across several geographically dispersed states. The index date for each patient corresponded with their first qualifying diagnosis of skin and nail candidiasis during January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. Inclusion in the study required continuous insurance enrollment from 30 days prior to 7 days after the index date, resulting in exclusion of 7% of commercial/Medicare patients and 8% of Medicaid patients. Prevalence per 1000 outpatients was calculated, with stratification by demographic characteristics.

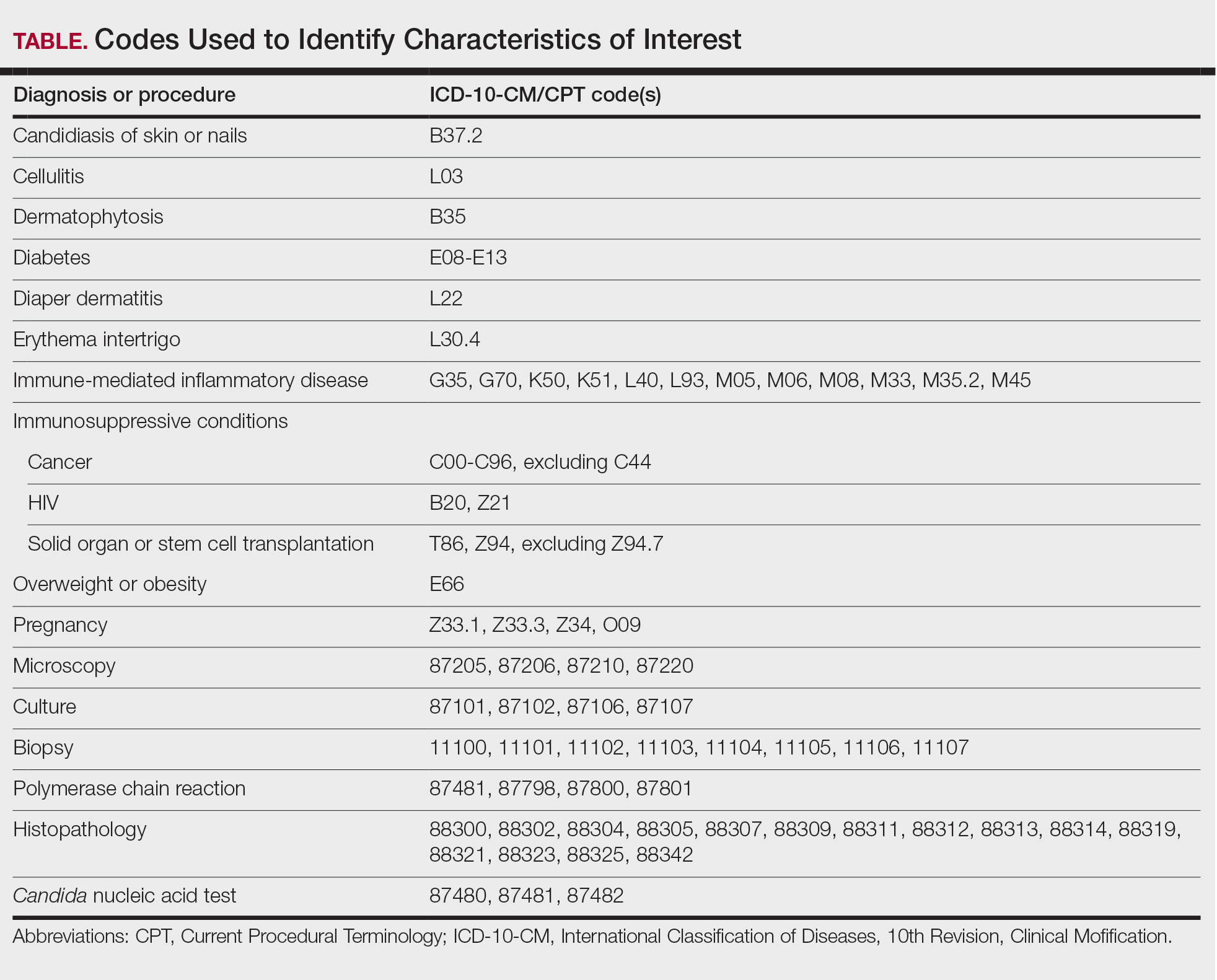

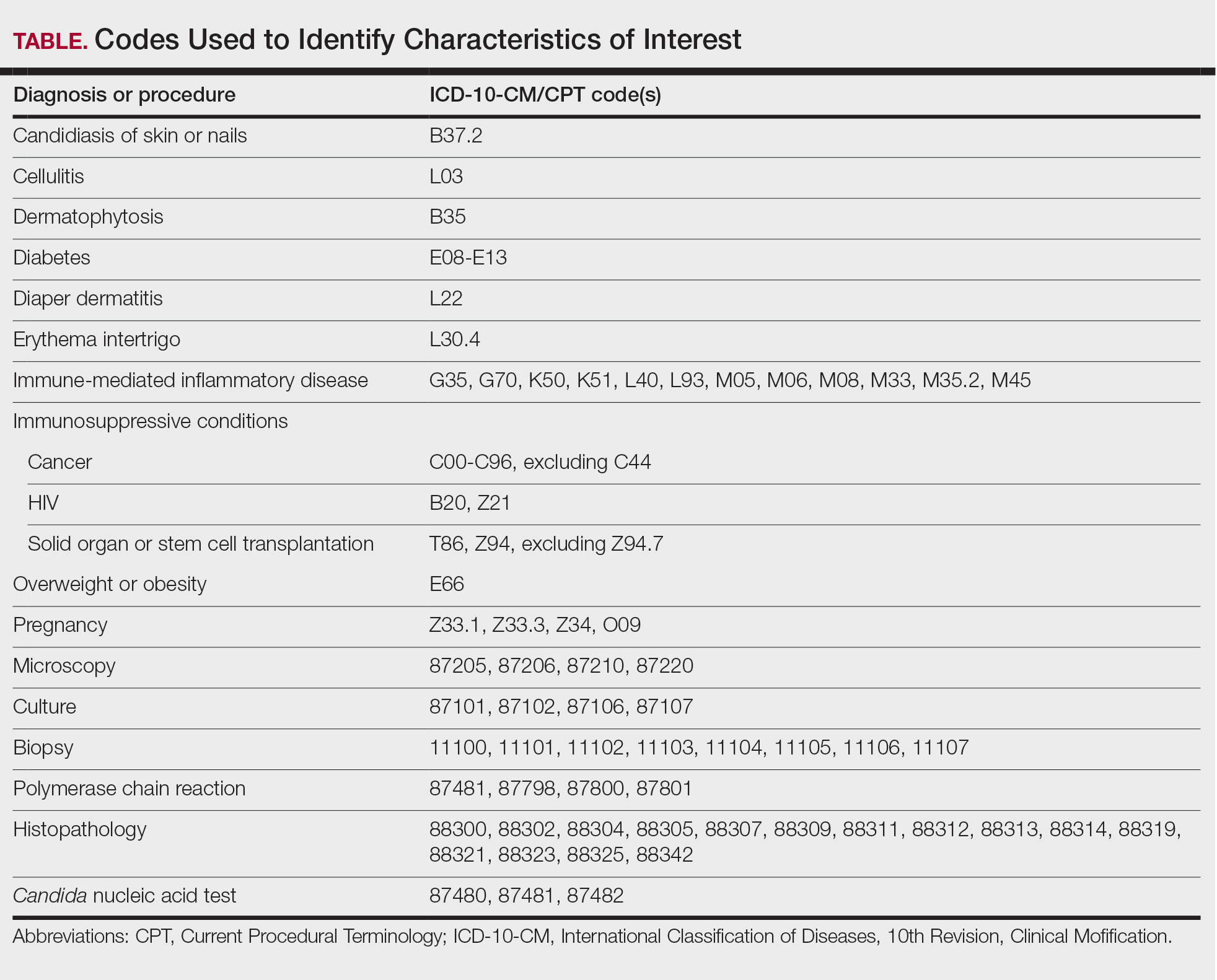

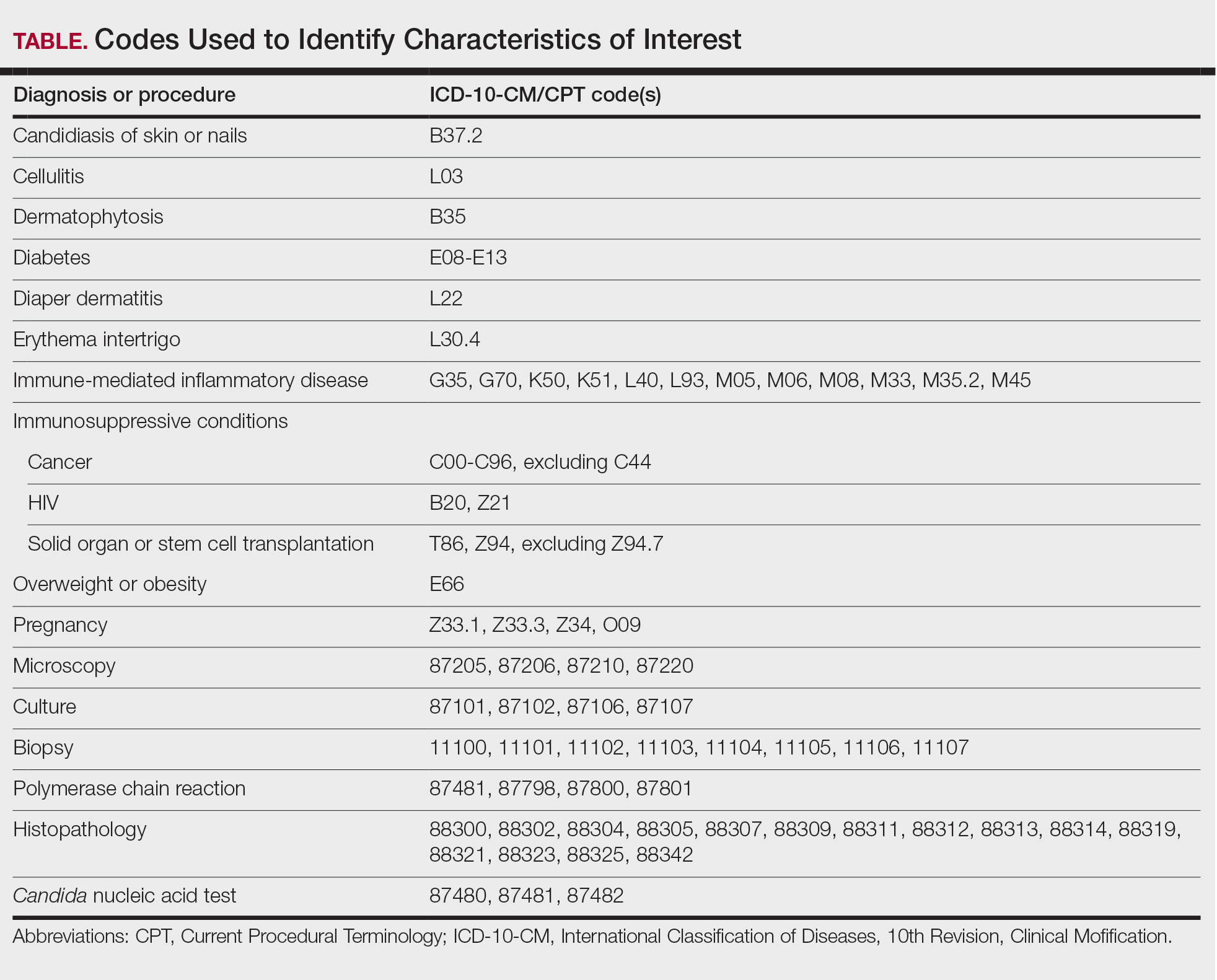

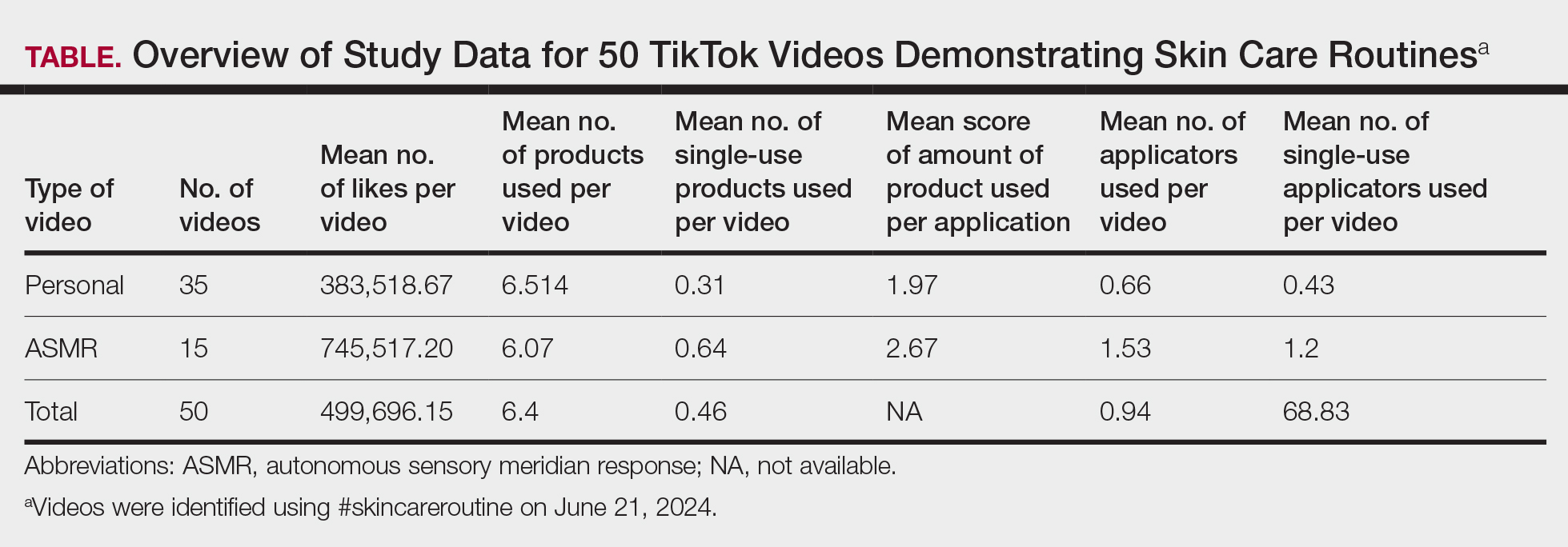

We examined selected diagnoses made on or within 30 days before the index date, diagnostic testing performed within the 7 days before or after the index date after using specific Current Procedural Terminology codes, and outpatient antifungal and combination antifungal-corticosteroid prescriptions made within 7 days before or after the index date (Table). Race/ethnicity data are unavailable in the commercial/Medicare database, and geographic data are unavailable in the Medicaid database.

Results

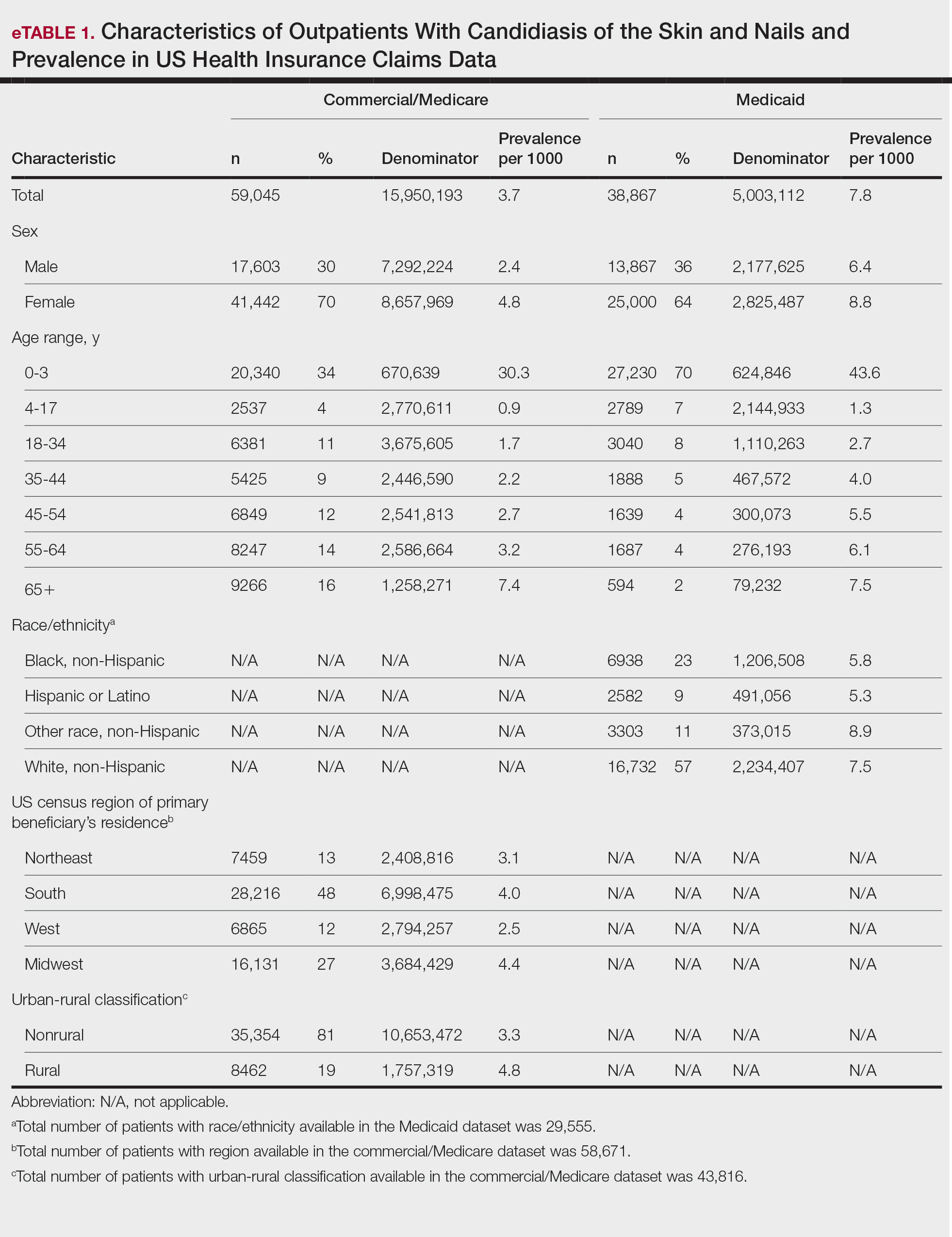

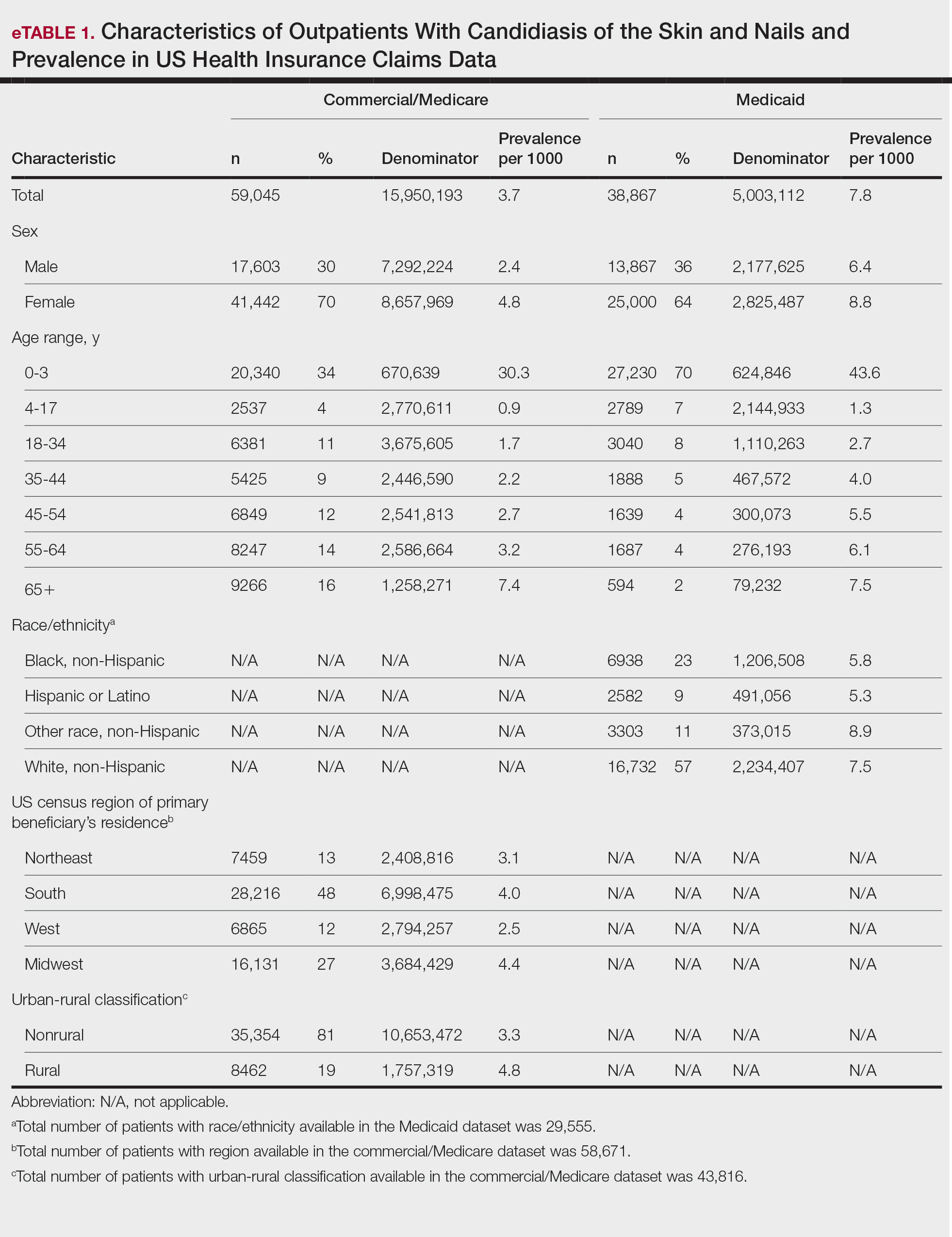

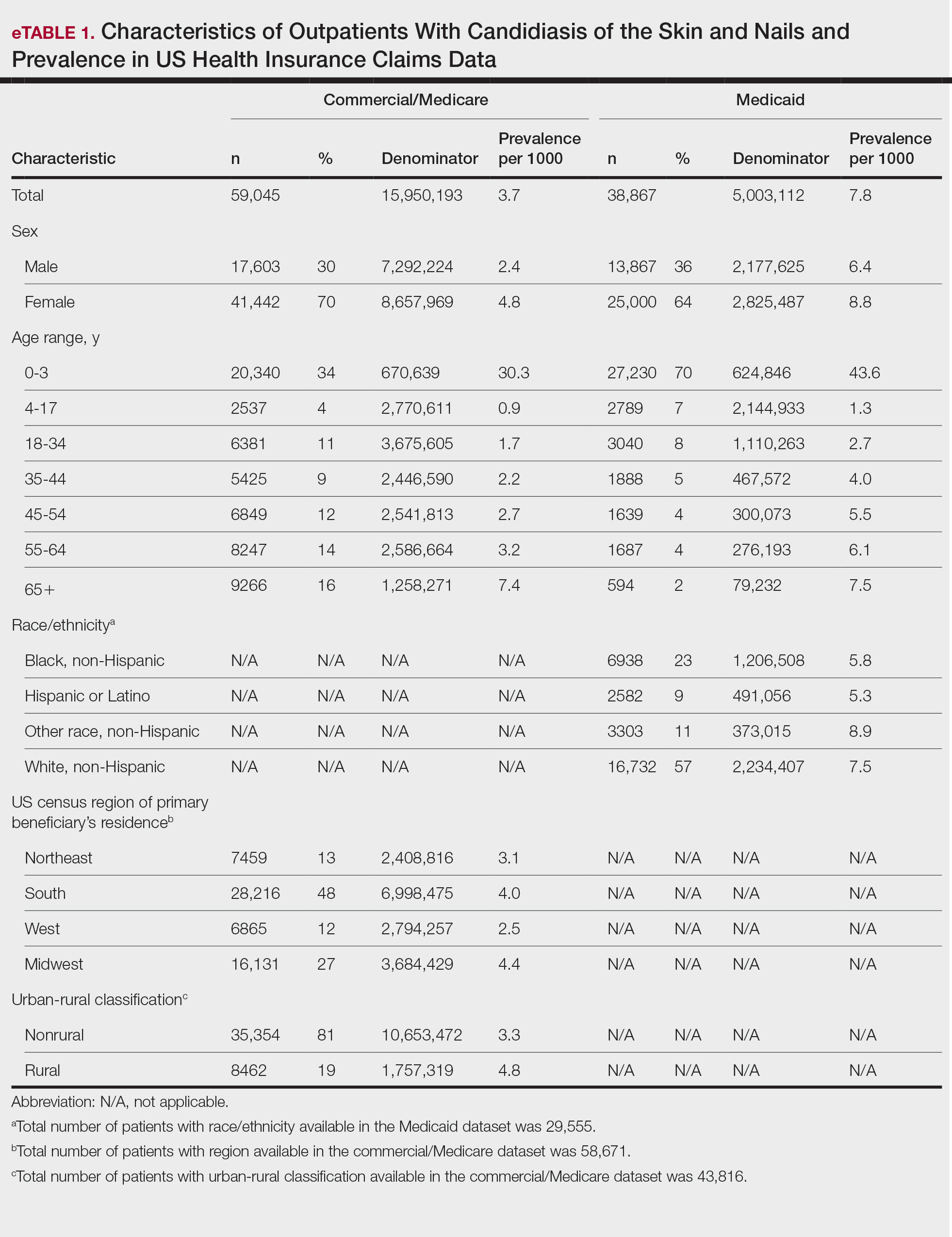

The prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis was 3.7 per 1000 commercial/Medicare outpatients and 7.8 per 1000 Medicaid outpatients (eTable 1). Prevalence was highest among patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 30.3 per 1000; Medicaid, 43.6 per 1000), followed by patients 65 years or older (commercial/Medicare, 7.4 per 1000; Medicaid, 7.5 per 1000). Prevalence was higher among females compared with males (commercial/Medicare, 4.8 vs 2.4 per 1000, respectively; Medicaid, 8.8 vs 6.4 per 1000, respectively). Among Medicaid patients, prevalence was highest among those of other race, non-Hispanic (8.9 per 1000) and White non-Hispanic patients (7.5 per 1000). In the commercial/Medicare dataset, prevalence was highest in patients residing in the Midwest (4.4 per 1000) and the South (4.0 per 1000).

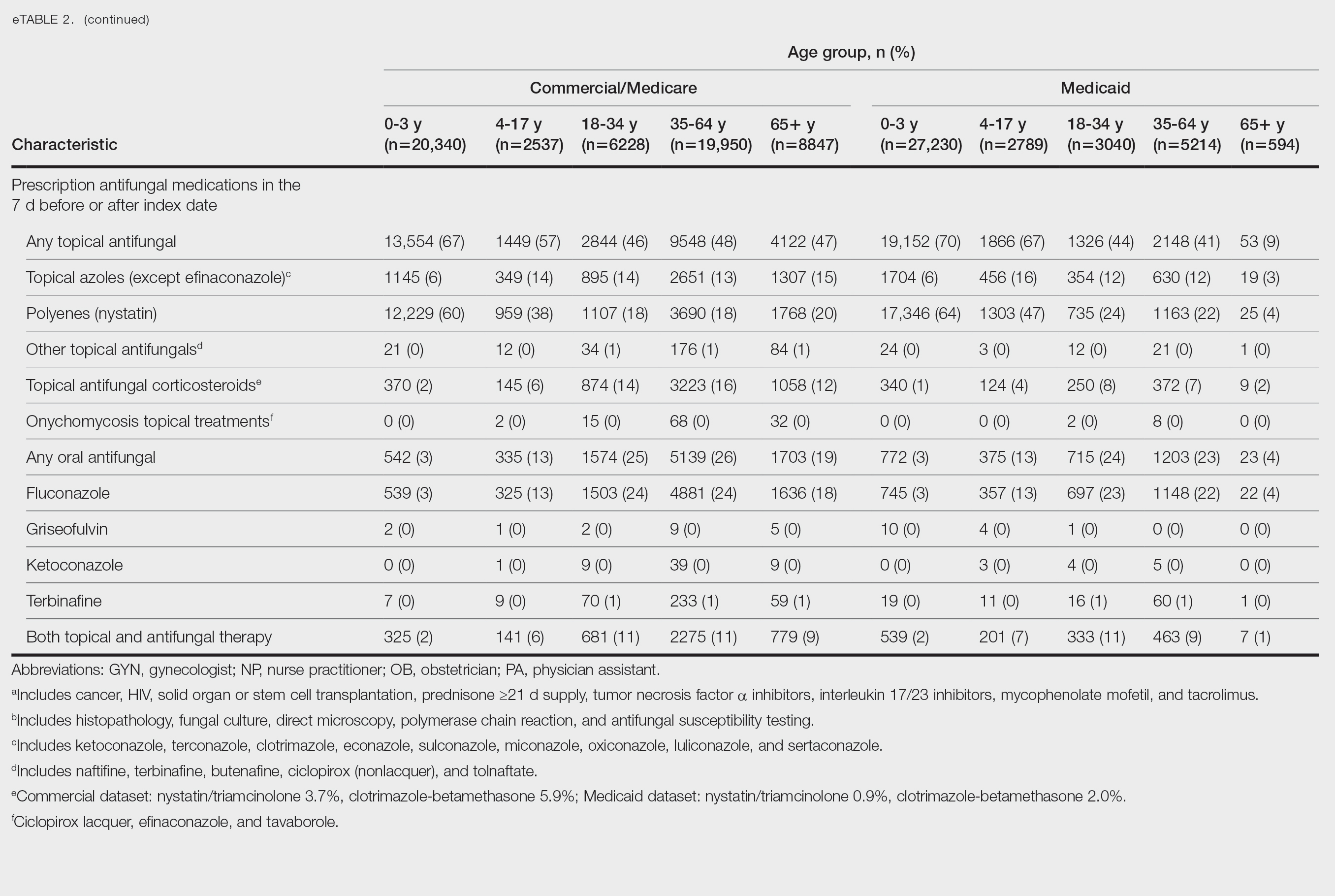

Diaper dermatitis was listed as a concurrent diagnosis among 51% of patients aged 0 to 3 years in both datasets (eTable 2). Diabetes (commercial/Medicare, 32%; Medicaid, 36%) and immunosuppressive conditions (commercial/Medicare, 10%; Medicaid, 7%) were most frequent among patients aged 65 years or older. Obesity was most commonly listed as a concurrent diagnosis among patients aged 35 to 64 years (commercial/Medicare, 17%; Medicaid, 23%).

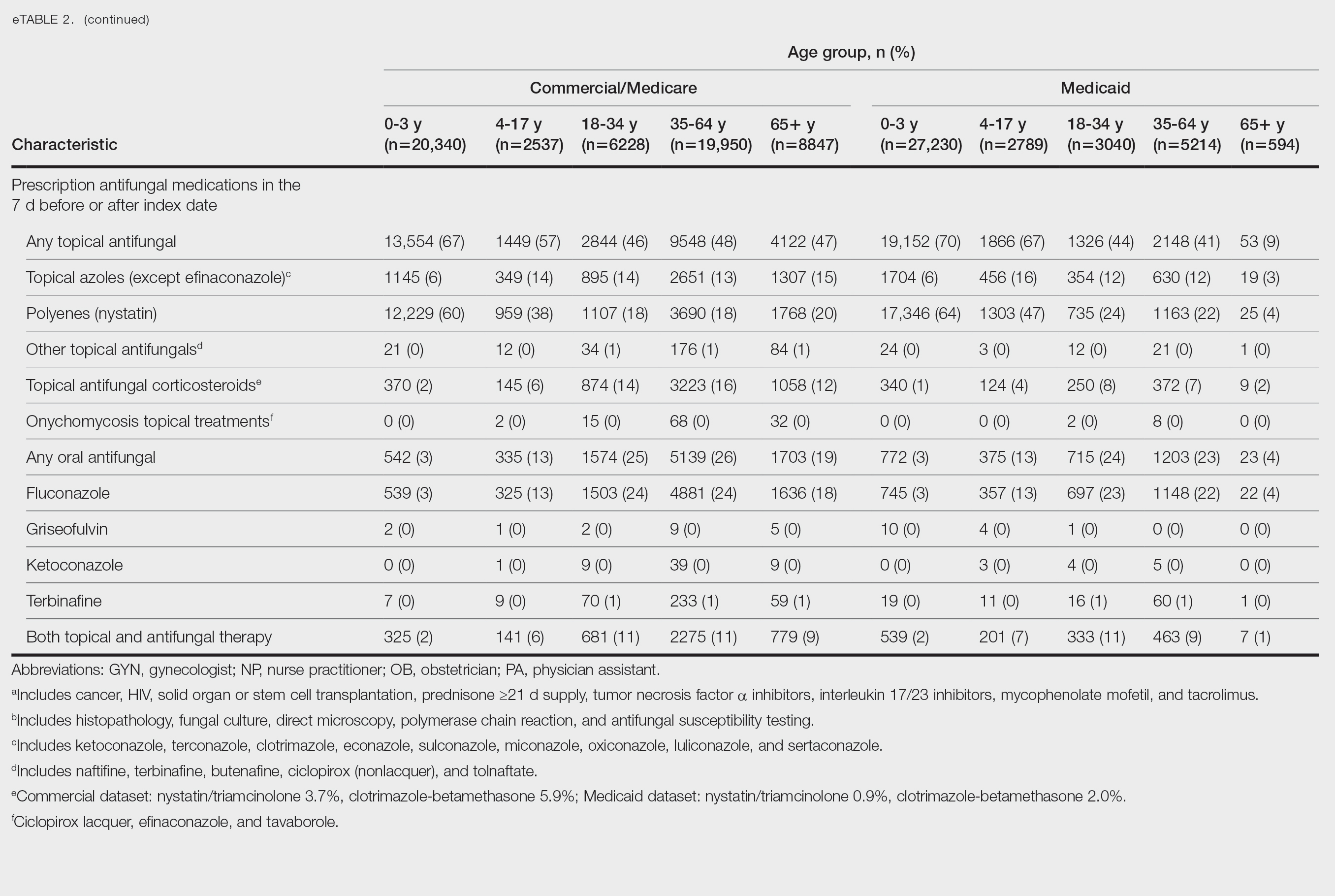

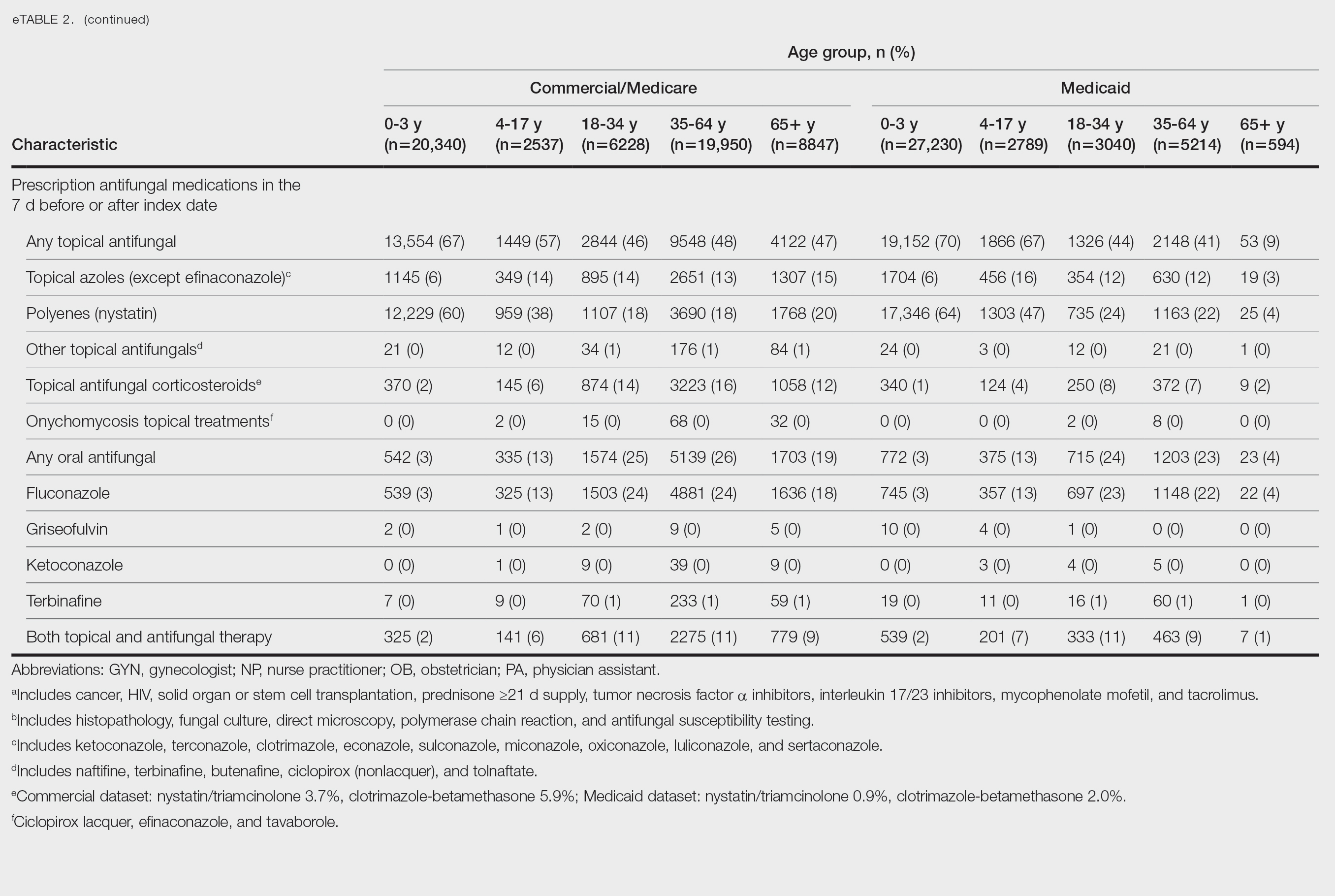

Patients aged 18 to 34 years had the highest rates of diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date (commercial/Medicare, 9%; Medicaid, 10%). Topical antifungal medications (primarily nystatin) were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 67%; Medicaid, 70%). Topical combination antifungal-corticosteroid medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (16%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (8%). Topical onychomycosis treatments were prescribed for fewer than 1% of patients in both datasets. Oral antifungal medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (26%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (24%). Fewer than 11% of patients across all age groups in both datasets were prescribed both topical and oral antifungal medications.

Comment

Our analysis provides preliminary insight into the prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis in the United States based on health insurance claims data. Higher prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis among patients with Medicaid compared with those with commercial/Medicare health insurance is consistent with previous studies showing increased rates of other superficial fungal infections (eg, dermatophytosis) among patients of lower socioeconomic status.2 This finding could reflect differences in underlying health status or reduced access to health care, which could delay treatment or follow-up care and potentially lead to prolonged exposure to conditions favoring the development of candidiasis.

In both the commercial/Medicare health insurance and Medicaid datasets, prevalence of diagnosis codes for candidiasis of the skin and nails was highest among infants and toddlers. Diaper dermatitis also was observed in more than half of patients aged 0 to 3 years; this is a well-established risk factor for cutaneous candidiasis, as immature skin barrier function and prolonged exposure to moisture and occlusion facilitate fungal overgrowth.3 In adults, diabetes and obesity were among the most frequent comorbidities observed; both conditions are recognized risk factors for superficial candidiasis due to their impact on immune function and skin integrity.4

In both study cohorts, diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date was infrequent (≤10%), consistent with most cases being diagnosed clinically.5 Topical antifungals, especially nystatin, were most frequently prescribed for young children, while oral antifungals were more frequently prescribed for adults; nystatin is one of the most well-studied topical treatments for cutaneous candidiasis, and oral fluconazole is the primary systemic treatment for cutaneous candidiasis.1 In our study, the ICD-10-CM code B37.2 appeared to be used primarily for diagnosis of skin rather than nail infections based on the low proportions of patients who received treatment that was onychomycosis specific.

Our study was limited by potential misclassification inherent to data based on diagnosis codes; incomplete capture of underlying conditions given the short continuous enrollment criteria; and lack of information about affected body site(s) and laboratory results, including data identifying the Candida species. A previous study found that Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans were the most common species involved in candidiasis of the skin and nails and that one-third of isolates exhibited low sensitivity to commonly used antifungals.6 For nails, Candida species are sometimes contaminants rather than pathogens.

Conclusion

Our findings provide a baseline understanding of the epidemiology of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States. The growing threat of antifungal resistance, particularly among non-albicans Candida species, underscores the need for appropriate use of antifungals.7 Future epidemiologic studies about laboratory-confirmed candidiasis of the skin and nails to understand causative species and drug resistance would be useful, as would further investigation into disparities.

- Taudorf EH, Jemec GBE, Hay RJ, et al. Cutaneous candidiasis—an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1863-1873. doi:10.1111/jdv.15782

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102325

- Benitez Ojeda AB, Mendez MD. Diaper dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559067/

- Shahabudin S, Azmi NS, Lani MN, et al. Candida albicans skin infection in diabetic patients: an updated review of pathogenesis and management. Mycoses. 2024;67:E13753. doi:10.1111/myc.13753

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Ranđelovic M, Ignjatovic A, Đorđevic M, et al. Superficial candidiasis: cluster analysis of species distribution and their antifungal susceptibility in vitro. J Fungi (Basel). 2025;11:338.

- Hay R. Therapy of skin, hair and nail fungal infections. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:99. doi:10.3390/jof4030099

Candida is a common commensal organism of human skin and mucous membranes. Candidiasis of the skin and nails is caused by overgrowth of Candida species due to excess skin moisture, skin barrier disruption, or immunosuppression. Candidiasis of the skin manifests as red, moist, itchy patches that develop particularly in skin folds. Nail involvement is associated with onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and subungual debris.1 Data on the prevalence of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and treatment practices of candidiasis of the skin and nails using data from 2 large US health insurance claims databases.

Methods

We used the 2023 Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases) to identify outpatients with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code B37.2 for candidiasis of the skin and nails. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases include health insurance claims data submitted by large employers and health plans for more than 19 million patients throughout the United States, and the Multi-State Medicaid database includes similar data from more than 5 million patients across several geographically dispersed states. The index date for each patient corresponded with their first qualifying diagnosis of skin and nail candidiasis during January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. Inclusion in the study required continuous insurance enrollment from 30 days prior to 7 days after the index date, resulting in exclusion of 7% of commercial/Medicare patients and 8% of Medicaid patients. Prevalence per 1000 outpatients was calculated, with stratification by demographic characteristics.

We examined selected diagnoses made on or within 30 days before the index date, diagnostic testing performed within the 7 days before or after the index date after using specific Current Procedural Terminology codes, and outpatient antifungal and combination antifungal-corticosteroid prescriptions made within 7 days before or after the index date (Table). Race/ethnicity data are unavailable in the commercial/Medicare database, and geographic data are unavailable in the Medicaid database.

Results

The prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis was 3.7 per 1000 commercial/Medicare outpatients and 7.8 per 1000 Medicaid outpatients (eTable 1). Prevalence was highest among patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 30.3 per 1000; Medicaid, 43.6 per 1000), followed by patients 65 years or older (commercial/Medicare, 7.4 per 1000; Medicaid, 7.5 per 1000). Prevalence was higher among females compared with males (commercial/Medicare, 4.8 vs 2.4 per 1000, respectively; Medicaid, 8.8 vs 6.4 per 1000, respectively). Among Medicaid patients, prevalence was highest among those of other race, non-Hispanic (8.9 per 1000) and White non-Hispanic patients (7.5 per 1000). In the commercial/Medicare dataset, prevalence was highest in patients residing in the Midwest (4.4 per 1000) and the South (4.0 per 1000).

Diaper dermatitis was listed as a concurrent diagnosis among 51% of patients aged 0 to 3 years in both datasets (eTable 2). Diabetes (commercial/Medicare, 32%; Medicaid, 36%) and immunosuppressive conditions (commercial/Medicare, 10%; Medicaid, 7%) were most frequent among patients aged 65 years or older. Obesity was most commonly listed as a concurrent diagnosis among patients aged 35 to 64 years (commercial/Medicare, 17%; Medicaid, 23%).

Patients aged 18 to 34 years had the highest rates of diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date (commercial/Medicare, 9%; Medicaid, 10%). Topical antifungal medications (primarily nystatin) were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 67%; Medicaid, 70%). Topical combination antifungal-corticosteroid medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (16%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (8%). Topical onychomycosis treatments were prescribed for fewer than 1% of patients in both datasets. Oral antifungal medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (26%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (24%). Fewer than 11% of patients across all age groups in both datasets were prescribed both topical and oral antifungal medications.

Comment

Our analysis provides preliminary insight into the prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis in the United States based on health insurance claims data. Higher prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis among patients with Medicaid compared with those with commercial/Medicare health insurance is consistent with previous studies showing increased rates of other superficial fungal infections (eg, dermatophytosis) among patients of lower socioeconomic status.2 This finding could reflect differences in underlying health status or reduced access to health care, which could delay treatment or follow-up care and potentially lead to prolonged exposure to conditions favoring the development of candidiasis.

In both the commercial/Medicare health insurance and Medicaid datasets, prevalence of diagnosis codes for candidiasis of the skin and nails was highest among infants and toddlers. Diaper dermatitis also was observed in more than half of patients aged 0 to 3 years; this is a well-established risk factor for cutaneous candidiasis, as immature skin barrier function and prolonged exposure to moisture and occlusion facilitate fungal overgrowth.3 In adults, diabetes and obesity were among the most frequent comorbidities observed; both conditions are recognized risk factors for superficial candidiasis due to their impact on immune function and skin integrity.4

In both study cohorts, diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date was infrequent (≤10%), consistent with most cases being diagnosed clinically.5 Topical antifungals, especially nystatin, were most frequently prescribed for young children, while oral antifungals were more frequently prescribed for adults; nystatin is one of the most well-studied topical treatments for cutaneous candidiasis, and oral fluconazole is the primary systemic treatment for cutaneous candidiasis.1 In our study, the ICD-10-CM code B37.2 appeared to be used primarily for diagnosis of skin rather than nail infections based on the low proportions of patients who received treatment that was onychomycosis specific.

Our study was limited by potential misclassification inherent to data based on diagnosis codes; incomplete capture of underlying conditions given the short continuous enrollment criteria; and lack of information about affected body site(s) and laboratory results, including data identifying the Candida species. A previous study found that Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans were the most common species involved in candidiasis of the skin and nails and that one-third of isolates exhibited low sensitivity to commonly used antifungals.6 For nails, Candida species are sometimes contaminants rather than pathogens.

Conclusion

Our findings provide a baseline understanding of the epidemiology of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States. The growing threat of antifungal resistance, particularly among non-albicans Candida species, underscores the need for appropriate use of antifungals.7 Future epidemiologic studies about laboratory-confirmed candidiasis of the skin and nails to understand causative species and drug resistance would be useful, as would further investigation into disparities.

Candida is a common commensal organism of human skin and mucous membranes. Candidiasis of the skin and nails is caused by overgrowth of Candida species due to excess skin moisture, skin barrier disruption, or immunosuppression. Candidiasis of the skin manifests as red, moist, itchy patches that develop particularly in skin folds. Nail involvement is associated with onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and subungual debris.1 Data on the prevalence of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States are scarce. In this study, we evaluated the prevalence, characteristics, and treatment practices of candidiasis of the skin and nails using data from 2 large US health insurance claims databases.

Methods

We used the 2023 Merative MarketScan Commercial, Medicare Supplemental, and Multi-State Medicaid Databases (https://www.merative.com/documents/merative-marketscan-research-databases) to identify outpatients with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code B37.2 for candidiasis of the skin and nails. The Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases include health insurance claims data submitted by large employers and health plans for more than 19 million patients throughout the United States, and the Multi-State Medicaid database includes similar data from more than 5 million patients across several geographically dispersed states. The index date for each patient corresponded with their first qualifying diagnosis of skin and nail candidiasis during January 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023. Inclusion in the study required continuous insurance enrollment from 30 days prior to 7 days after the index date, resulting in exclusion of 7% of commercial/Medicare patients and 8% of Medicaid patients. Prevalence per 1000 outpatients was calculated, with stratification by demographic characteristics.

We examined selected diagnoses made on or within 30 days before the index date, diagnostic testing performed within the 7 days before or after the index date after using specific Current Procedural Terminology codes, and outpatient antifungal and combination antifungal-corticosteroid prescriptions made within 7 days before or after the index date (Table). Race/ethnicity data are unavailable in the commercial/Medicare database, and geographic data are unavailable in the Medicaid database.

Results

The prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis was 3.7 per 1000 commercial/Medicare outpatients and 7.8 per 1000 Medicaid outpatients (eTable 1). Prevalence was highest among patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 30.3 per 1000; Medicaid, 43.6 per 1000), followed by patients 65 years or older (commercial/Medicare, 7.4 per 1000; Medicaid, 7.5 per 1000). Prevalence was higher among females compared with males (commercial/Medicare, 4.8 vs 2.4 per 1000, respectively; Medicaid, 8.8 vs 6.4 per 1000, respectively). Among Medicaid patients, prevalence was highest among those of other race, non-Hispanic (8.9 per 1000) and White non-Hispanic patients (7.5 per 1000). In the commercial/Medicare dataset, prevalence was highest in patients residing in the Midwest (4.4 per 1000) and the South (4.0 per 1000).

Diaper dermatitis was listed as a concurrent diagnosis among 51% of patients aged 0 to 3 years in both datasets (eTable 2). Diabetes (commercial/Medicare, 32%; Medicaid, 36%) and immunosuppressive conditions (commercial/Medicare, 10%; Medicaid, 7%) were most frequent among patients aged 65 years or older. Obesity was most commonly listed as a concurrent diagnosis among patients aged 35 to 64 years (commercial/Medicare, 17%; Medicaid, 23%).

Patients aged 18 to 34 years had the highest rates of diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date (commercial/Medicare, 9%; Medicaid, 10%). Topical antifungal medications (primarily nystatin) were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 0 to 3 years (commercial/Medicare, 67%; Medicaid, 70%). Topical combination antifungal-corticosteroid medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (16%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (8%). Topical onychomycosis treatments were prescribed for fewer than 1% of patients in both datasets. Oral antifungal medications were most frequently prescribed for patients aged 35 to 64 years in the commercial/Medicare dataset (26%) and for patients aged 18 to 34 years in the Medicaid dataset (24%). Fewer than 11% of patients across all age groups in both datasets were prescribed both topical and oral antifungal medications.

Comment

Our analysis provides preliminary insight into the prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis in the United States based on health insurance claims data. Higher prevalence of skin and nail candidiasis among patients with Medicaid compared with those with commercial/Medicare health insurance is consistent with previous studies showing increased rates of other superficial fungal infections (eg, dermatophytosis) among patients of lower socioeconomic status.2 This finding could reflect differences in underlying health status or reduced access to health care, which could delay treatment or follow-up care and potentially lead to prolonged exposure to conditions favoring the development of candidiasis.

In both the commercial/Medicare health insurance and Medicaid datasets, prevalence of diagnosis codes for candidiasis of the skin and nails was highest among infants and toddlers. Diaper dermatitis also was observed in more than half of patients aged 0 to 3 years; this is a well-established risk factor for cutaneous candidiasis, as immature skin barrier function and prolonged exposure to moisture and occlusion facilitate fungal overgrowth.3 In adults, diabetes and obesity were among the most frequent comorbidities observed; both conditions are recognized risk factors for superficial candidiasis due to their impact on immune function and skin integrity.4

In both study cohorts, diagnostic testing in the 7 days before or after the index date was infrequent (≤10%), consistent with most cases being diagnosed clinically.5 Topical antifungals, especially nystatin, were most frequently prescribed for young children, while oral antifungals were more frequently prescribed for adults; nystatin is one of the most well-studied topical treatments for cutaneous candidiasis, and oral fluconazole is the primary systemic treatment for cutaneous candidiasis.1 In our study, the ICD-10-CM code B37.2 appeared to be used primarily for diagnosis of skin rather than nail infections based on the low proportions of patients who received treatment that was onychomycosis specific.

Our study was limited by potential misclassification inherent to data based on diagnosis codes; incomplete capture of underlying conditions given the short continuous enrollment criteria; and lack of information about affected body site(s) and laboratory results, including data identifying the Candida species. A previous study found that Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans were the most common species involved in candidiasis of the skin and nails and that one-third of isolates exhibited low sensitivity to commonly used antifungals.6 For nails, Candida species are sometimes contaminants rather than pathogens.

Conclusion

Our findings provide a baseline understanding of the epidemiology of candidiasis of the skin and nails in the United States. The growing threat of antifungal resistance, particularly among non-albicans Candida species, underscores the need for appropriate use of antifungals.7 Future epidemiologic studies about laboratory-confirmed candidiasis of the skin and nails to understand causative species and drug resistance would be useful, as would further investigation into disparities.

- Taudorf EH, Jemec GBE, Hay RJ, et al. Cutaneous candidiasis—an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1863-1873. doi:10.1111/jdv.15782

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102325

- Benitez Ojeda AB, Mendez MD. Diaper dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559067/

- Shahabudin S, Azmi NS, Lani MN, et al. Candida albicans skin infection in diabetic patients: an updated review of pathogenesis and management. Mycoses. 2024;67:E13753. doi:10.1111/myc.13753

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Ranđelovic M, Ignjatovic A, Đorđevic M, et al. Superficial candidiasis: cluster analysis of species distribution and their antifungal susceptibility in vitro. J Fungi (Basel). 2025;11:338.

- Hay R. Therapy of skin, hair and nail fungal infections. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:99. doi:10.3390/jof4030099

- Taudorf EH, Jemec GBE, Hay RJ, et al. Cutaneous candidiasis—an evidence-based review of topical and systemic treatments to inform clinical practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1863-1873. doi:10.1111/jdv.15782

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102325

- Benitez Ojeda AB, Mendez MD. Diaper dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 3, 2023. Accessed January 14, 2026. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559067/

- Shahabudin S, Azmi NS, Lani MN, et al. Candida albicans skin infection in diabetic patients: an updated review of pathogenesis and management. Mycoses. 2024;67:E13753. doi:10.1111/myc.13753

- Kalra MG, Higgins KE, Kinney BS. Intertrigo and secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89:569-573.

- Ranđelovic M, Ignjatovic A, Đorđevic M, et al. Superficial candidiasis: cluster analysis of species distribution and their antifungal susceptibility in vitro. J Fungi (Basel). 2025;11:338.

- Hay R. Therapy of skin, hair and nail fungal infections. J Fungi (Basel). 2018;4:99. doi:10.3390/jof4030099

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

Retrospective Analysis of Prevalence and Treatment Patterns of Skin and Nail Candidiasis From US Health Insurance Claims Data

Practice Points

- Candidiasis of the skin or nails is a common outpatient condition that is most frequently diagnosed in infants, toddlers, and adults aged 65 years or older.

- Most cases are diagnosed clinically without diagnostic testing and treated with topical antifungals, but increased attention to formal diagnosis and treatment may be warranted given the emergence of antifungal-resistant Candida species.

Treating Dermatophyte Onychomycosis: Clinical Insights From Dr. Shari R. Lipner

Treating Dermatophyte Onychomycosis: Clinical Insights From Dr. Shari R. Lipner

With increasing reports of terbinafine resistance, how has your strategy for treating dermatophyte onychomycosis evolved?

DR. LIPNER: Most cases of onychomycosis are not resistant to terbinafine, so for a patient newly diagnosed with onychomycosis, my approach involves evaluating the severity of disease, number of nails affected, comorbid conditions, and concomitant medications and then discussing the risks and benefits of oral vs topical treatment. If a patient’s onychomycosis previously did not resolve with oral terbinafine, I would test for terbinafine resistance. If positive, I would treat with itraconazole for more severe cases and efinaconazole for mild to moderate cases.

Are there any new systemic or topical antifungals for onychomycosis that dermatologists should be aware of?

DR. LIPNER: There have been no new US Food and Drug Administration–approved antifungals for onychomycosis since 2014 (efinaconazole and tavaborole). For most patients, our current antifungals generally have good efficacy. For treatment failures, I would recommend reconfirming the diagnosis and testing for terbinafine resistance.

When do you choose oral antifungal therapy vs topical/combination therapy?

DR. LIPNER: almost never prescribe combination antifungal therapy because monotherapy alone is usually effective, and there is no obvious benefit to combination therapy. If treatment is working (or not working), it is hard to know which agent (if any) is effective. The one time I would use combination therapy (eg, oral terbinafine and topical efinaconazole) would be if the patient has distal lateral subungual onychomycosis and a dermatophytoma. Oral terbinafine would generally be most effective for distal lateral subungual onychomycosis, and topical efinaconazole would likely be most effective for dermatophytoma.

What is the role of adjunctive therapies in onychomycosis?

DR. LIPNER: Debridement can be effective for patients with very thick nails, combined with oral or topical antifungals. Nail avulsion generally is not helpful and should be avoided because it causes permanent shortening of the nail bed. Devices (eg, lasers, photodynamic therapy) are not subject to the same stringent endpoints as medication-based approvals. Because studies to date are small and have different efficacy endpoints, I do not use devices for treatment of onychomycosis.

How do you counsel patients about expectations and timelines for onychomycosis therapy and cure vs improvement?

DR. LIPNER: Oral treatments for toenail onychomycosis are generally given for 3-month courses, but patients should be counseled that the nail could take up to 12 to 18 months to fully grow out and look normal. If patients also have mechanical nail dystrophy, the fungus may be cured with antifungal therapy, but the nail may look better but not perfect, so it is important to manage long-term expectations.

With increasing reports of terbinafine resistance, how has your strategy for treating dermatophyte onychomycosis evolved?

DR. LIPNER: Most cases of onychomycosis are not resistant to terbinafine, so for a patient newly diagnosed with onychomycosis, my approach involves evaluating the severity of disease, number of nails affected, comorbid conditions, and concomitant medications and then discussing the risks and benefits of oral vs topical treatment. If a patient’s onychomycosis previously did not resolve with oral terbinafine, I would test for terbinafine resistance. If positive, I would treat with itraconazole for more severe cases and efinaconazole for mild to moderate cases.

Are there any new systemic or topical antifungals for onychomycosis that dermatologists should be aware of?

DR. LIPNER: There have been no new US Food and Drug Administration–approved antifungals for onychomycosis since 2014 (efinaconazole and tavaborole). For most patients, our current antifungals generally have good efficacy. For treatment failures, I would recommend reconfirming the diagnosis and testing for terbinafine resistance.

When do you choose oral antifungal therapy vs topical/combination therapy?

DR. LIPNER: almost never prescribe combination antifungal therapy because monotherapy alone is usually effective, and there is no obvious benefit to combination therapy. If treatment is working (or not working), it is hard to know which agent (if any) is effective. The one time I would use combination therapy (eg, oral terbinafine and topical efinaconazole) would be if the patient has distal lateral subungual onychomycosis and a dermatophytoma. Oral terbinafine would generally be most effective for distal lateral subungual onychomycosis, and topical efinaconazole would likely be most effective for dermatophytoma.

What is the role of adjunctive therapies in onychomycosis?

DR. LIPNER: Debridement can be effective for patients with very thick nails, combined with oral or topical antifungals. Nail avulsion generally is not helpful and should be avoided because it causes permanent shortening of the nail bed. Devices (eg, lasers, photodynamic therapy) are not subject to the same stringent endpoints as medication-based approvals. Because studies to date are small and have different efficacy endpoints, I do not use devices for treatment of onychomycosis.

How do you counsel patients about expectations and timelines for onychomycosis therapy and cure vs improvement?

DR. LIPNER: Oral treatments for toenail onychomycosis are generally given for 3-month courses, but patients should be counseled that the nail could take up to 12 to 18 months to fully grow out and look normal. If patients also have mechanical nail dystrophy, the fungus may be cured with antifungal therapy, but the nail may look better but not perfect, so it is important to manage long-term expectations.

With increasing reports of terbinafine resistance, how has your strategy for treating dermatophyte onychomycosis evolved?

DR. LIPNER: Most cases of onychomycosis are not resistant to terbinafine, so for a patient newly diagnosed with onychomycosis, my approach involves evaluating the severity of disease, number of nails affected, comorbid conditions, and concomitant medications and then discussing the risks and benefits of oral vs topical treatment. If a patient’s onychomycosis previously did not resolve with oral terbinafine, I would test for terbinafine resistance. If positive, I would treat with itraconazole for more severe cases and efinaconazole for mild to moderate cases.

Are there any new systemic or topical antifungals for onychomycosis that dermatologists should be aware of?

DR. LIPNER: There have been no new US Food and Drug Administration–approved antifungals for onychomycosis since 2014 (efinaconazole and tavaborole). For most patients, our current antifungals generally have good efficacy. For treatment failures, I would recommend reconfirming the diagnosis and testing for terbinafine resistance.

When do you choose oral antifungal therapy vs topical/combination therapy?

DR. LIPNER: almost never prescribe combination antifungal therapy because monotherapy alone is usually effective, and there is no obvious benefit to combination therapy. If treatment is working (or not working), it is hard to know which agent (if any) is effective. The one time I would use combination therapy (eg, oral terbinafine and topical efinaconazole) would be if the patient has distal lateral subungual onychomycosis and a dermatophytoma. Oral terbinafine would generally be most effective for distal lateral subungual onychomycosis, and topical efinaconazole would likely be most effective for dermatophytoma.

What is the role of adjunctive therapies in onychomycosis?

DR. LIPNER: Debridement can be effective for patients with very thick nails, combined with oral or topical antifungals. Nail avulsion generally is not helpful and should be avoided because it causes permanent shortening of the nail bed. Devices (eg, lasers, photodynamic therapy) are not subject to the same stringent endpoints as medication-based approvals. Because studies to date are small and have different efficacy endpoints, I do not use devices for treatment of onychomycosis.

How do you counsel patients about expectations and timelines for onychomycosis therapy and cure vs improvement?

DR. LIPNER: Oral treatments for toenail onychomycosis are generally given for 3-month courses, but patients should be counseled that the nail could take up to 12 to 18 months to fully grow out and look normal. If patients also have mechanical nail dystrophy, the fungus may be cured with antifungal therapy, but the nail may look better but not perfect, so it is important to manage long-term expectations.

Treating Dermatophyte Onychomycosis: Clinical Insights From Dr. Shari R. Lipner

Treating Dermatophyte Onychomycosis: Clinical Insights From Dr. Shari R. Lipner

Waterproof Cast Protector Keeps Wound Dressing Intact Following Nail Surgery

Waterproof Cast Protector Keeps Wound Dressing Intact Following Nail Surgery

Practice Gap

Postoperative care after nail biopsies can be challenging for patients due to the bulky dressing that must remain in place for 48 hours.1 The dressing can restrict daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, and other household tasks. A common solution is to cover the hand with a plastic bag secured with tape during water-related activities, but efficacy is variable. In one study, 23 participants tested this method by holding a paper towel with their hand covered by a plastic bag and measuring the weight of the paper towel before and after submersion of the hand in water.2 Any saturation of the paper towel was defined as failure; the failure rate was 52.2% (12/23) with motion (rotating the arm at the elbow for 30 seconds clockwise, counterclockwise, and left to right) and 60.9% (14/23) without motion. There was an average of 5.50 g of moisture accumulation without motion and 4.51 g with motion, with failure occurring most often immediately following submersion of the hand. Furthermore, the plastic bag with tape method was rated poorly by all 23 participants based on efficacy and comfort.2

In the same study, participants also reported that removal of the adhesive tape was unpleasant and irritating,2 which suggests these same complaints may apply to use of a waterproof bandage, another potential option for coverage of the wound dressing. As an alternative, we propose the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector following nail surgery that allows patients to continue their regular activities while keeping the dressing dry and intact to allow for optimal wound healing.

The Technique

Our technique involves the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector that is sealed with a thick rubber cuff, allowing patients to perform regular daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, cleaning, and doing laundry without the wound dressing underneath becoming wet (Figure). Cast protectors made of flexible latex-free plastic are readily available and can slide on and off the arm as needed. We recommend that patients purchase the cast protector prior to undergoing surgery. There are options to fit most adults, with the opening generally accommodating arm diameters of 2 to 7 inches. These reusable cast protectors are available via popular online retailers and typically cost patients $10 to $15.

Practice Implications

In our experience, using a reusable waterproof cast protector following nail surgery is effective at keeping wound dressings dry and provides a practical solution for bathing and other activities involving water exposure. It is durable and easy to use, especially when compared to a plastic bag and waterproof tape. However, some patients find the waterproof seal uncomfortable, especially when worn for extended periods of time. According to online product feedback, limitations of the cast protector include potential leakage with prolonged immersion in water, swimming, or high-pressure water exposure. The cast protector should not be worn for more than 30 minutes, as it can restrict blood flow, and condensation from prolonged use may dampen the dressing. While we have not encountered allergic contact dermatitis associated with the use of cast protectors for this purpose in our practice, patients should be cautioned of this potential risk. While these cast protectors generally can accommodate a range of arm diameters, they may not fit all hand sizes or shapes and may reduce dexterity for motor tasks. Additionally, the patient must purchase the protector ahead of surgery.

Our technique involving the use of a waterproof arm cast protector is an affordable solution that allows patients to keep their wound dressing dry while continuing to perform regular daily activities. The cast protector also can be used following other dermatologic procedures (eg, biopsy, Mohs micrographic surgery) that involve the hand and lower arm when waterproof protection may be necessary.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. How we do it: pressure-padded dressing with self-adherent elastic wrap for wound care after nail surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:442–444. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002371

- Kwan S, Santoro A, Cheesman Q, et al. Efficacy of waterproof cast protectors and their ability to keep casts dry. J Hand Surg Am. 2023;48:803–809. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.05.006

Practice Gap

Postoperative care after nail biopsies can be challenging for patients due to the bulky dressing that must remain in place for 48 hours.1 The dressing can restrict daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, and other household tasks. A common solution is to cover the hand with a plastic bag secured with tape during water-related activities, but efficacy is variable. In one study, 23 participants tested this method by holding a paper towel with their hand covered by a plastic bag and measuring the weight of the paper towel before and after submersion of the hand in water.2 Any saturation of the paper towel was defined as failure; the failure rate was 52.2% (12/23) with motion (rotating the arm at the elbow for 30 seconds clockwise, counterclockwise, and left to right) and 60.9% (14/23) without motion. There was an average of 5.50 g of moisture accumulation without motion and 4.51 g with motion, with failure occurring most often immediately following submersion of the hand. Furthermore, the plastic bag with tape method was rated poorly by all 23 participants based on efficacy and comfort.2

In the same study, participants also reported that removal of the adhesive tape was unpleasant and irritating,2 which suggests these same complaints may apply to use of a waterproof bandage, another potential option for coverage of the wound dressing. As an alternative, we propose the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector following nail surgery that allows patients to continue their regular activities while keeping the dressing dry and intact to allow for optimal wound healing.

The Technique

Our technique involves the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector that is sealed with a thick rubber cuff, allowing patients to perform regular daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, cleaning, and doing laundry without the wound dressing underneath becoming wet (Figure). Cast protectors made of flexible latex-free plastic are readily available and can slide on and off the arm as needed. We recommend that patients purchase the cast protector prior to undergoing surgery. There are options to fit most adults, with the opening generally accommodating arm diameters of 2 to 7 inches. These reusable cast protectors are available via popular online retailers and typically cost patients $10 to $15.

Practice Implications

In our experience, using a reusable waterproof cast protector following nail surgery is effective at keeping wound dressings dry and provides a practical solution for bathing and other activities involving water exposure. It is durable and easy to use, especially when compared to a plastic bag and waterproof tape. However, some patients find the waterproof seal uncomfortable, especially when worn for extended periods of time. According to online product feedback, limitations of the cast protector include potential leakage with prolonged immersion in water, swimming, or high-pressure water exposure. The cast protector should not be worn for more than 30 minutes, as it can restrict blood flow, and condensation from prolonged use may dampen the dressing. While we have not encountered allergic contact dermatitis associated with the use of cast protectors for this purpose in our practice, patients should be cautioned of this potential risk. While these cast protectors generally can accommodate a range of arm diameters, they may not fit all hand sizes or shapes and may reduce dexterity for motor tasks. Additionally, the patient must purchase the protector ahead of surgery.

Our technique involving the use of a waterproof arm cast protector is an affordable solution that allows patients to keep their wound dressing dry while continuing to perform regular daily activities. The cast protector also can be used following other dermatologic procedures (eg, biopsy, Mohs micrographic surgery) that involve the hand and lower arm when waterproof protection may be necessary.

Practice Gap

Postoperative care after nail biopsies can be challenging for patients due to the bulky dressing that must remain in place for 48 hours.1 The dressing can restrict daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, and other household tasks. A common solution is to cover the hand with a plastic bag secured with tape during water-related activities, but efficacy is variable. In one study, 23 participants tested this method by holding a paper towel with their hand covered by a plastic bag and measuring the weight of the paper towel before and after submersion of the hand in water.2 Any saturation of the paper towel was defined as failure; the failure rate was 52.2% (12/23) with motion (rotating the arm at the elbow for 30 seconds clockwise, counterclockwise, and left to right) and 60.9% (14/23) without motion. There was an average of 5.50 g of moisture accumulation without motion and 4.51 g with motion, with failure occurring most often immediately following submersion of the hand. Furthermore, the plastic bag with tape method was rated poorly by all 23 participants based on efficacy and comfort.2

In the same study, participants also reported that removal of the adhesive tape was unpleasant and irritating,2 which suggests these same complaints may apply to use of a waterproof bandage, another potential option for coverage of the wound dressing. As an alternative, we propose the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector following nail surgery that allows patients to continue their regular activities while keeping the dressing dry and intact to allow for optimal wound healing.

The Technique

Our technique involves the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector that is sealed with a thick rubber cuff, allowing patients to perform regular daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, cleaning, and doing laundry without the wound dressing underneath becoming wet (Figure). Cast protectors made of flexible latex-free plastic are readily available and can slide on and off the arm as needed. We recommend that patients purchase the cast protector prior to undergoing surgery. There are options to fit most adults, with the opening generally accommodating arm diameters of 2 to 7 inches. These reusable cast protectors are available via popular online retailers and typically cost patients $10 to $15.

Practice Implications

In our experience, using a reusable waterproof cast protector following nail surgery is effective at keeping wound dressings dry and provides a practical solution for bathing and other activities involving water exposure. It is durable and easy to use, especially when compared to a plastic bag and waterproof tape. However, some patients find the waterproof seal uncomfortable, especially when worn for extended periods of time. According to online product feedback, limitations of the cast protector include potential leakage with prolonged immersion in water, swimming, or high-pressure water exposure. The cast protector should not be worn for more than 30 minutes, as it can restrict blood flow, and condensation from prolonged use may dampen the dressing. While we have not encountered allergic contact dermatitis associated with the use of cast protectors for this purpose in our practice, patients should be cautioned of this potential risk. While these cast protectors generally can accommodate a range of arm diameters, they may not fit all hand sizes or shapes and may reduce dexterity for motor tasks. Additionally, the patient must purchase the protector ahead of surgery.

Our technique involving the use of a waterproof arm cast protector is an affordable solution that allows patients to keep their wound dressing dry while continuing to perform regular daily activities. The cast protector also can be used following other dermatologic procedures (eg, biopsy, Mohs micrographic surgery) that involve the hand and lower arm when waterproof protection may be necessary.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. How we do it: pressure-padded dressing with self-adherent elastic wrap for wound care after nail surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:442–444. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002371

- Kwan S, Santoro A, Cheesman Q, et al. Efficacy of waterproof cast protectors and their ability to keep casts dry. J Hand Surg Am. 2023;48:803–809. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.05.006

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. How we do it: pressure-padded dressing with self-adherent elastic wrap for wound care after nail surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:442–444. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002371

- Kwan S, Santoro A, Cheesman Q, et al. Efficacy of waterproof cast protectors and their ability to keep casts dry. J Hand Surg Am. 2023;48:803–809. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.05.006

Waterproof Cast Protector Keeps Wound Dressing Intact Following Nail Surgery

Waterproof Cast Protector Keeps Wound Dressing Intact Following Nail Surgery

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

To the Editor:

Residency applicants, especially in competitive specialties such as dermatology, face major financial barriers due to the high costs of applications, interviews, and away rotations.1 While several studies have examined application costs of other specialties, few have analyzed expenses associated with dermatology applications.1,2 There are no data examining costs following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; thus, our study evaluated dermatology application cost trends from 2021 to 2024 and compared them to other specialties to identify strategies to reduce the financial burden on applicants.

Self-reported total application costs, application fees, interview expenses, and away rotation costs from 2021 to 2024 were collected from the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency (STAR) database powered by the UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, Texas).3 The mean total application expenses per year were compared among specialties, and an analysis of variance was used to determine if the differences were statistically significant.

The number of applicants who recorded information in the Texas STAR database was 110 in 2021, 163 in 2022, 136 in 2023, and 129 in 2024.3 The total dermatology application expenses increased from $2805 in 2021 to $6231 in 2024; interview costs increased from $404 in 2021 to $911 in 2024; and away rotation costs increased from $850 in 2021 to $3812 in 2024 (all P<.05)(Table). There was no significant change in application fees during the study period ($2176 in 2021 to $2125 in 2024 [P=.58]). Dermatology had the fourth highest average total cost over the study period compared to all other specialties, increasing from $2250 in 2021 to $5250 in 2024, following orthopedic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $6750 in 2024), plastic surgery ($2250 in 2021 to $9750 in 2024), and neurosurgery ($1750 in 2021 to $11,250 in 2024).

Our study found that dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024, primarily driven by rising interview and away rotation expenses (both P<.05). This trend places dermatology among the most expensive fields to apply to for residency. A cross-sectional survey of dermatology residency program directors identified away rotations as one of the top 5 selection criteria, underscoring their importance in the matching process.4 In addition, a cross-sectional analysis of 345 dermatology residents found that 26.2% matched at institutions where they had mentors, including those they connected with through away rotations.5,6 Overall, the high cost of away rotations partially may reflect the competitive nature of the specialty, as building connections at programs may enhance the chances of matching. These costs also can vary based on geography, as rotating in high-cost urban centers can be more expensive than in rural areas; however, rural rotations may be less common due to limited program availability and applicant preferences. For example, nearly 50% of 2024 Electronic Residency Application Service applicants indicated a preference for urban settings, while fewer than 5% selected rural settings.7 Additionally, the high costs associated with applying to residency programs and completing away rotations can disproportionately impact students from rural backgrounds and underrepresented minorities, who may have fewer financial resources.

In our study, the lower application-related expenses in 2021 (during the pandemic) compared to those of 2024 (postpandemic) likely stem from the Association of American Medical Colleges’ recommendation to conduct virtual interviews during the pandemic.8 In 2024, some dermatology programs returned to in-person interviews, with some applicants consequently incurring higher costs related to travel, lodging, and other associated expenses.8 A cost-analysis study of 4153 dermatology applicants from 2016 to 2021 found that the average application costs were $1759 per applicant during the pandemic, when virtual interviews replaced in-person ones, whereas costs were $8476 per applicant during periods with in-person interviews and no COVID-19 restrictions.2 However, we did not observe a significant change in application fees over our study period, likely because the pandemic did not affect application numbers. A cross-sectional analysis of dermatology applicants during the pandemic similarly reported reductions in application-related expenses during the period when interviews were conducted virtually,9 supporting the trend observed in our study. Overall, our findings taken together with other studies highlight the pandemic’s role in reducing expenses and underscore the potential for exploring additional cost-saving measures.

Implementing strategies to reduce these financial burdens—including virtual interviews, increasing student funding for away rotations, and limiting the number of applications individual students can submit—could help alleviate socioeconomic disparities. The new signaling system for residency programs aims to reduce the number of applications submitted, as applicants typically receive interviews only from the limited number of programs they signal, reducing overall application costs. However, our data from the Texas STAR database suggest that application numbers remained relatively stable from 2021 to 2024, indicating that, despite signaling, many applicants still may apply broadly in hopes of improving their chances in an increasingly competitive field. Although a definitive solution to reducing the financial burden on dermatology applicants remains elusive, these strategies can raise awareness and encourage important dialogues.

Limitations of our study include the voluntary nature of the Texas STAR survey, leading to potential voluntary response bias, as well as the small sample size. Students who choose to submit cost data may differ systematically from those who do not; for example, students who match may be more likely to report their outcomes, while those who do not match may be less likely to participate, potentially introducing selection bias. In addition, general awareness of the Texas STAR survey may vary across institutions and among students, further limiting the number of students who participate. Additionally, 2021 was the only presignaling year included, making it difficult to assess longer-term trends. Despite these limitations, the Texas STAR database remains a valuable resource for analyzing general residency application expenses and trends, as it offers comprehensive data from more than 100 medical schools and includes many variables.3

In conclusion, our study found that total dermatology residency application costs have increased significantly from 2021 to 2024 (all P<.05), making dermatology among the most expensive specialties for applying. This study sets the foundation for future survey-based research for applicants and program directors on strategies to alleviate financial burdens.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.049

- Gorgy M, Shah S, Arbuiso S, et al. Comparison of cost changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic for dermatology residency applications in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:600-602. doi:10.1111/ced.15001<.li>

- UT Southwestern. Texas STAR. 2024. Accessed November 5, 2025. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html

- Baldwin K, Weidner Z, Ahn J, et al. Are away rotations critical for a successful match in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:3340-3345. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0920-9

- Yeh C, Desai AD, Wilson BN, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of scholarly work and mentor relationships in matched dermatology residency applicants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1437-1439. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.861

- Gorouhi F, Alikhan A, Rezaei A, et al. Dermatology residency selection criteria with an emphasis on program characteristics: a national program director survey. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:692760. doi:10.1155/2014/692760

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Decoding geographic and setting preferences in residency selection. January 18, 2024. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/services/eras-institutions/geographic-preferences

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Virtual interviews: tips for program directors. Updated May 14, 2020. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/gme/program_portal/pd/pd_meet/2019-2020/8-6-20-Virtual_Interview_Tips_for_Program_Directors_05142020.pdf

- Williams GE, Zimmerman JM, Wiggins CJ, et al. The indelible marks on dermatology: impacts of COVID-19 on dermatology residency match using the Texas STAR database. Clin Dermatol. 2023;41:215-218. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2022.12.001

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

Cost Analysis of Dermatology Residency Applications From 2021 to 2024 Using the Texas Seeking Transparency in Application to Residency Database

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatology application costs increased from 2021 to 2024, largely due to expenses related to away rotations and, in some cases, a return to in-person interviews.

- Away rotations play a critical role in the dermatology match; however, they also contribute substantially to financial burden.

- The cost-saving impact of virtual interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights a meaningful opportunity for future cost reduction.

- Further interventions are needed to meaningfully reduce financial burden and promote equity.

The Role of Dermatologists in Developing AI Tools for Diagnosis and Classification of Skin Disease

The Role of Dermatologists in Developing AI Tools for Diagnosis and Classification of Skin Disease