User login

MRSA incidence decreased in children as clindamycin resistance increased

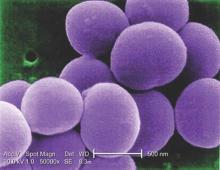

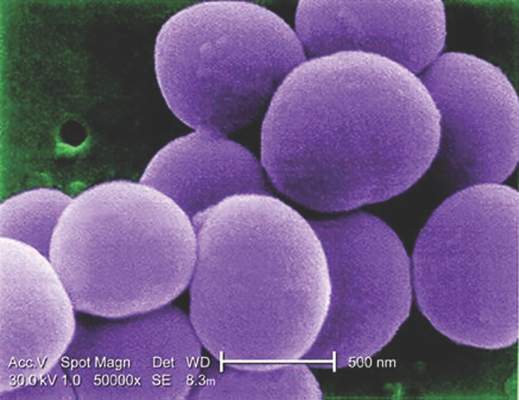

The incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections has decreased in children in recent years, but resistance to clindamycin has increased over the same period, a study showed.

“The epidemic of skin and soft tissue infections and invasive MRSA led to modifications of antimicrobial prescribing practices for suspected S. aureus infections,” reported Dr. Deena E. Sutter of the San Antonio Military Medical Center in Fort Sam Houston, Tex., and her associates. “Over the study period, erythromycin susceptibility among methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) remained stable, suggesting that declining clindamycin susceptibility is a result of an increase in inducible resistance.”

The steady decline in clindamycin susceptibility “may lead to some concern about the continued reliance on clindamycin for the empirical treatment of presumptive S. aureus infections, although it is probably premature to abandon this effective antibiotic choice,” they wrote (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar. 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3099). “It is crucial that clinicians remain knowledgeable about local susceptibility rates as it would be prudent to consider [alternative] antimicrobial agents for empirical use when the local clindamycin susceptibility rate drops below 85%.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed lab results from 39,209 patients under age 18 who were treated for S. aureus infections at one of the 266 U.S. facilities of the Military Health System from 2005 to 2014. The data included 41,745 S. aureus isolates, classified as MRSA if found resistant to cefoxitin, methicillin, or oxacillin and as methicillin susceptible (MSSA) if susceptible to those antimicrobials. The isolates had also been tested for susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, oxacillin, penicillin, rifampin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX).

During that decade, overall S. aureus susceptibility to clindamycin, ciprofloxacin, and TMP/SMX decreased – although susceptibility to TMP/SMX in 2014 stayed high at 98% – while overall susceptibility to erythromycin, gentamicin, and oxacillin increased. Specifically, 59% of S. aureus isolates were susceptible to oxacillin in 2005, which dropped briefly to 54% in 2007 before climbing to the 2014 rate of 68%.

Meanwhile, overall susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 86% in 2014, and MSSA susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 84% in 2014. “Erythromycin susceptibility remained stable among MSSA isolates throughout the study period at 63.5%, whereas MRSA susceptibility to erythromycin increased from 12.1% to 20.5%,” Dr. Sutter and her associates reported. “Ciprofloxacin susceptibility significantly decreased overall, although an initial decrease of 10.6% over the first 7 years of the study was subsequently followed by an increase of 6% between 2011 and 2014.”

Most of the isolates came from patients with skin and soft tissue infections, which were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin than were other infections. Infections in children aged 1-5 years also were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin, compared with infections in children of other age groups.

If the local clindamycin susceptibility rate falls below 85%, “beta-lactams, TMP/SMX, or tetracyclines may be used for less severe infections with intravenous vancomycin employed in severe cases,” the investigators said. “If overall MRSA rates continue to decline and clindamycin resistance among MSSA continues to increase, we may see a return to antistaphylococcal beta-lactam antimicrobial agents such as oxacillin or first-generation cephalosporins as preferred empirical therapy for presumed S. aureus infections.”

The research did not use external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common organisms isolated from children with health care–associated infections, regardless of whether these infections had their onset in the community or were acquired in the hospital. Thus, the initial empiric treatment of a skin or soft tissue infection or invasive infection in a child almost always includes an antibiotic effective against S. aureus.

However, over the years, clindamycin susceptibility among S. aureus isolates has declined, likely related to the increased use of this agent for empiric as well as definitive treatment of community-acquired (CA) MRSA infections, encouraging the transmission of the genes associated with clindamycin resistance.

What are the implications of the findings from the report by Sutter et al. with respect to the selection of empiric antibiotics for children with suspected S. aureus infections? Currently, considering the still substantial MRSA resistance rates that exceed the 10%-15% level suggested by many experts as the threshold above which agents effective against CA-MRSA isolates should be administered for empiric treatment, changes in the selection of empiric antibiotics are not warranted. If rates of MRSA among S. aureus isolates from otherwise normal children are documented to drop below the 10%-15% threshold in different communities, a modification of current recommendations should be considered. It would also be important to understand why methicillin resistance is declining among S. aureus isolates from CA infections; this information may provide clues for preventing CA-MRSA infections with the use of vaccines or other means. The epidemiology of S. aureus infections in children has been changing over the past 2 decades, which is why it is critical to keep a very close eye on this common pathogen.

These comments were excerpted from an accompanying commentary by Dr. Sheldon L. Kaplan of the infectious disease service at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0101). Dr. Kaplan has received research funds from Pfizer, Forest Laboratories, and Cubist.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common organisms isolated from children with health care–associated infections, regardless of whether these infections had their onset in the community or were acquired in the hospital. Thus, the initial empiric treatment of a skin or soft tissue infection or invasive infection in a child almost always includes an antibiotic effective against S. aureus.

However, over the years, clindamycin susceptibility among S. aureus isolates has declined, likely related to the increased use of this agent for empiric as well as definitive treatment of community-acquired (CA) MRSA infections, encouraging the transmission of the genes associated with clindamycin resistance.

What are the implications of the findings from the report by Sutter et al. with respect to the selection of empiric antibiotics for children with suspected S. aureus infections? Currently, considering the still substantial MRSA resistance rates that exceed the 10%-15% level suggested by many experts as the threshold above which agents effective against CA-MRSA isolates should be administered for empiric treatment, changes in the selection of empiric antibiotics are not warranted. If rates of MRSA among S. aureus isolates from otherwise normal children are documented to drop below the 10%-15% threshold in different communities, a modification of current recommendations should be considered. It would also be important to understand why methicillin resistance is declining among S. aureus isolates from CA infections; this information may provide clues for preventing CA-MRSA infections with the use of vaccines or other means. The epidemiology of S. aureus infections in children has been changing over the past 2 decades, which is why it is critical to keep a very close eye on this common pathogen.

These comments were excerpted from an accompanying commentary by Dr. Sheldon L. Kaplan of the infectious disease service at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0101). Dr. Kaplan has received research funds from Pfizer, Forest Laboratories, and Cubist.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common organisms isolated from children with health care–associated infections, regardless of whether these infections had their onset in the community or were acquired in the hospital. Thus, the initial empiric treatment of a skin or soft tissue infection or invasive infection in a child almost always includes an antibiotic effective against S. aureus.

However, over the years, clindamycin susceptibility among S. aureus isolates has declined, likely related to the increased use of this agent for empiric as well as definitive treatment of community-acquired (CA) MRSA infections, encouraging the transmission of the genes associated with clindamycin resistance.

What are the implications of the findings from the report by Sutter et al. with respect to the selection of empiric antibiotics for children with suspected S. aureus infections? Currently, considering the still substantial MRSA resistance rates that exceed the 10%-15% level suggested by many experts as the threshold above which agents effective against CA-MRSA isolates should be administered for empiric treatment, changes in the selection of empiric antibiotics are not warranted. If rates of MRSA among S. aureus isolates from otherwise normal children are documented to drop below the 10%-15% threshold in different communities, a modification of current recommendations should be considered. It would also be important to understand why methicillin resistance is declining among S. aureus isolates from CA infections; this information may provide clues for preventing CA-MRSA infections with the use of vaccines or other means. The epidemiology of S. aureus infections in children has been changing over the past 2 decades, which is why it is critical to keep a very close eye on this common pathogen.

These comments were excerpted from an accompanying commentary by Dr. Sheldon L. Kaplan of the infectious disease service at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0101). Dr. Kaplan has received research funds from Pfizer, Forest Laboratories, and Cubist.

The incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections has decreased in children in recent years, but resistance to clindamycin has increased over the same period, a study showed.

“The epidemic of skin and soft tissue infections and invasive MRSA led to modifications of antimicrobial prescribing practices for suspected S. aureus infections,” reported Dr. Deena E. Sutter of the San Antonio Military Medical Center in Fort Sam Houston, Tex., and her associates. “Over the study period, erythromycin susceptibility among methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) remained stable, suggesting that declining clindamycin susceptibility is a result of an increase in inducible resistance.”

The steady decline in clindamycin susceptibility “may lead to some concern about the continued reliance on clindamycin for the empirical treatment of presumptive S. aureus infections, although it is probably premature to abandon this effective antibiotic choice,” they wrote (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar. 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3099). “It is crucial that clinicians remain knowledgeable about local susceptibility rates as it would be prudent to consider [alternative] antimicrobial agents for empirical use when the local clindamycin susceptibility rate drops below 85%.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed lab results from 39,209 patients under age 18 who were treated for S. aureus infections at one of the 266 U.S. facilities of the Military Health System from 2005 to 2014. The data included 41,745 S. aureus isolates, classified as MRSA if found resistant to cefoxitin, methicillin, or oxacillin and as methicillin susceptible (MSSA) if susceptible to those antimicrobials. The isolates had also been tested for susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, oxacillin, penicillin, rifampin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX).

During that decade, overall S. aureus susceptibility to clindamycin, ciprofloxacin, and TMP/SMX decreased – although susceptibility to TMP/SMX in 2014 stayed high at 98% – while overall susceptibility to erythromycin, gentamicin, and oxacillin increased. Specifically, 59% of S. aureus isolates were susceptible to oxacillin in 2005, which dropped briefly to 54% in 2007 before climbing to the 2014 rate of 68%.

Meanwhile, overall susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 86% in 2014, and MSSA susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 84% in 2014. “Erythromycin susceptibility remained stable among MSSA isolates throughout the study period at 63.5%, whereas MRSA susceptibility to erythromycin increased from 12.1% to 20.5%,” Dr. Sutter and her associates reported. “Ciprofloxacin susceptibility significantly decreased overall, although an initial decrease of 10.6% over the first 7 years of the study was subsequently followed by an increase of 6% between 2011 and 2014.”

Most of the isolates came from patients with skin and soft tissue infections, which were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin than were other infections. Infections in children aged 1-5 years also were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin, compared with infections in children of other age groups.

If the local clindamycin susceptibility rate falls below 85%, “beta-lactams, TMP/SMX, or tetracyclines may be used for less severe infections with intravenous vancomycin employed in severe cases,” the investigators said. “If overall MRSA rates continue to decline and clindamycin resistance among MSSA continues to increase, we may see a return to antistaphylococcal beta-lactam antimicrobial agents such as oxacillin or first-generation cephalosporins as preferred empirical therapy for presumed S. aureus infections.”

The research did not use external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

The incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections has decreased in children in recent years, but resistance to clindamycin has increased over the same period, a study showed.

“The epidemic of skin and soft tissue infections and invasive MRSA led to modifications of antimicrobial prescribing practices for suspected S. aureus infections,” reported Dr. Deena E. Sutter of the San Antonio Military Medical Center in Fort Sam Houston, Tex., and her associates. “Over the study period, erythromycin susceptibility among methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) remained stable, suggesting that declining clindamycin susceptibility is a result of an increase in inducible resistance.”

The steady decline in clindamycin susceptibility “may lead to some concern about the continued reliance on clindamycin for the empirical treatment of presumptive S. aureus infections, although it is probably premature to abandon this effective antibiotic choice,” they wrote (Pediatrics. 2016 Mar. 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3099). “It is crucial that clinicians remain knowledgeable about local susceptibility rates as it would be prudent to consider [alternative] antimicrobial agents for empirical use when the local clindamycin susceptibility rate drops below 85%.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed lab results from 39,209 patients under age 18 who were treated for S. aureus infections at one of the 266 U.S. facilities of the Military Health System from 2005 to 2014. The data included 41,745 S. aureus isolates, classified as MRSA if found resistant to cefoxitin, methicillin, or oxacillin and as methicillin susceptible (MSSA) if susceptible to those antimicrobials. The isolates had also been tested for susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, oxacillin, penicillin, rifampin, tetracycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX).

During that decade, overall S. aureus susceptibility to clindamycin, ciprofloxacin, and TMP/SMX decreased – although susceptibility to TMP/SMX in 2014 stayed high at 98% – while overall susceptibility to erythromycin, gentamicin, and oxacillin increased. Specifically, 59% of S. aureus isolates were susceptible to oxacillin in 2005, which dropped briefly to 54% in 2007 before climbing to the 2014 rate of 68%.

Meanwhile, overall susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 86% in 2014, and MSSA susceptibility to clindamycin dropped from 91% in 2005 to 84% in 2014. “Erythromycin susceptibility remained stable among MSSA isolates throughout the study period at 63.5%, whereas MRSA susceptibility to erythromycin increased from 12.1% to 20.5%,” Dr. Sutter and her associates reported. “Ciprofloxacin susceptibility significantly decreased overall, although an initial decrease of 10.6% over the first 7 years of the study was subsequently followed by an increase of 6% between 2011 and 2014.”

Most of the isolates came from patients with skin and soft tissue infections, which were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin than were other infections. Infections in children aged 1-5 years also were less likely to be susceptible to oxacillin, compared with infections in children of other age groups.

If the local clindamycin susceptibility rate falls below 85%, “beta-lactams, TMP/SMX, or tetracyclines may be used for less severe infections with intravenous vancomycin employed in severe cases,” the investigators said. “If overall MRSA rates continue to decline and clindamycin resistance among MSSA continues to increase, we may see a return to antistaphylococcal beta-lactam antimicrobial agents such as oxacillin or first-generation cephalosporins as preferred empirical therapy for presumed S. aureus infections.”

The research did not use external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: The incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections has decreased in children in recent years while resistance to clindamycin has increased.

Major finding: MRSA susceptibility to oxacillin increased to 68.4% in 2014, and susceptibility dropped to 86% for clindamycin.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of 41,745 S. aureus isolates from 39,209 patients under age 18 years in the U.S. Military Health System between 2005 and 2014.

Disclosures: The research did not use external funding, and the authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Risperidone, aripiprazole treat irritability in children with ASD

Risperidone and aripiprazole, followed by N-acetylcysteine, appear most effective in treating irritability and aggression in youth with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in the February issue of Pediatrics.

“Although risperidone and aripiprazole have the strongest evidence for reducing ABC-I [Aberrant Behavioral Checklist–Irritability] in youth with autism spectrum disorders, they also have evidence for significant adverse events for a subset of patients,” reported Dr. Lawrence K. Fung of Stanford (Calif) University, and his associates (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb.;137[Suppl 2]:S124-35).

More than half of autistic individuals show significant emotion dysregulation, and about 20% have irritability or aggression at moderate to severe levels.

The authors combed Medline, PsychINFO, Embase, and review articles to identify randomized placebo-controlled trials evaluating medications to treat irritability and aggression in ASD youth, aged 2-17 years. The researchers used Aberrant Behavioral Checklist–Irritability scores as the primary endpoint in assessing effect size for improvement of emotional and behavioral symptoms in individuals with ASD.

Of 35 randomized controlled trials involving 1,673 participants included in the systematic review, 25 trials used the ABC-I, with 11 targeting irritability as the primary outcome and the other 14 targeting a different primary outcome. Five of the 11 trials targeting irritability tested the effectiveness of risperidone, while 2 tested aripiprazole, 2 tested valproate, 1 tested N-acetylcysteine, and 1 tested amantadine. Risperidone, aripiprazole, and N-acetylcysteine showed improvement in ABC-I scores with a moderate to large effect size. Valproate showed significant improvement to a lesser extent, but amantadine did not.

Among medications tested in the other 14 trials using the ABC-I, clonidine, methylphenidate, and tianeptine showed improvement with moderate effect sizes ,while venlafaxine and naltrexone showed improvement with a small effect size. Other medications tested included atomoxetine, citalopram, dextromethorphan, levetiracetam, mecamylamine, omega-3 fatty acid, and secretin. Hyperactivity and impulsivity improved in trials testing atomoxetine and dextromethorphan.

In trials using assessments other than ABC-I, risperidone and haloperidol showed effectiveness, compared with placebos, although risperidone beat haloperidol in a head-to-head trial. Some improvement in irritability also occurred with clomipramine, naltrexone, and a supplement with 19 vitamins and 9 minerals, compared with placebo.

The researchers calculated a number needed to treat (NNT) of two for risperidone at a dose between 1.2 and 1.9 mg, but the number needed to harm (NNH) for sedation from risperidone was also two. Risperidone’s NNH for extrapyramidal symptoms was six to seven. Flexible dosing with aripiprazole yielded an NNT of three, but fixed dosing led to an NNT of five to seven. The NNH for sedation with aripiprazole was 16, and the NNH for extrapyramidal symptoms was 20.

Sedation also occurred with haloperidol (NNH = 1) and amantadine (NNH = 10), and haloperidol caused extrapyramidal symptoms (NNH = 10). Weight gain occurred with risperidone, aripiprazole, and valproate.

“The reason for more compounds failing to show efficacy is not clear, but some of the negative studies had small sample sizes,” the authors noted. “Therefore, it is possible that some of these negative studies may represent false negatives,” and some of the studies used baseline ABC-I scores below the typical cutoff of at least 18 for inclusion.

The research was conducted through the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network and was supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the maternal and child health research program at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Daniel Coury has received research funding from Autism Speaks, SynapDx, and Neuren Pharmaceuticals; has consulted for Cognoa; and is a speaker for Abbott/Innovative Biopharma. Dr. Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele has received research funding from Seaside Therapeutics, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Forest, Sunovion, and SynapDx and has consulted for or advised Roche Pharmaceuticals, SynapDx, and Novartis.

Risperidone and aripiprazole, followed by N-acetylcysteine, appear most effective in treating irritability and aggression in youth with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in the February issue of Pediatrics.

“Although risperidone and aripiprazole have the strongest evidence for reducing ABC-I [Aberrant Behavioral Checklist–Irritability] in youth with autism spectrum disorders, they also have evidence for significant adverse events for a subset of patients,” reported Dr. Lawrence K. Fung of Stanford (Calif) University, and his associates (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb.;137[Suppl 2]:S124-35).

More than half of autistic individuals show significant emotion dysregulation, and about 20% have irritability or aggression at moderate to severe levels.

The authors combed Medline, PsychINFO, Embase, and review articles to identify randomized placebo-controlled trials evaluating medications to treat irritability and aggression in ASD youth, aged 2-17 years. The researchers used Aberrant Behavioral Checklist–Irritability scores as the primary endpoint in assessing effect size for improvement of emotional and behavioral symptoms in individuals with ASD.

Of 35 randomized controlled trials involving 1,673 participants included in the systematic review, 25 trials used the ABC-I, with 11 targeting irritability as the primary outcome and the other 14 targeting a different primary outcome. Five of the 11 trials targeting irritability tested the effectiveness of risperidone, while 2 tested aripiprazole, 2 tested valproate, 1 tested N-acetylcysteine, and 1 tested amantadine. Risperidone, aripiprazole, and N-acetylcysteine showed improvement in ABC-I scores with a moderate to large effect size. Valproate showed significant improvement to a lesser extent, but amantadine did not.

Among medications tested in the other 14 trials using the ABC-I, clonidine, methylphenidate, and tianeptine showed improvement with moderate effect sizes ,while venlafaxine and naltrexone showed improvement with a small effect size. Other medications tested included atomoxetine, citalopram, dextromethorphan, levetiracetam, mecamylamine, omega-3 fatty acid, and secretin. Hyperactivity and impulsivity improved in trials testing atomoxetine and dextromethorphan.

In trials using assessments other than ABC-I, risperidone and haloperidol showed effectiveness, compared with placebos, although risperidone beat haloperidol in a head-to-head trial. Some improvement in irritability also occurred with clomipramine, naltrexone, and a supplement with 19 vitamins and 9 minerals, compared with placebo.

The researchers calculated a number needed to treat (NNT) of two for risperidone at a dose between 1.2 and 1.9 mg, but the number needed to harm (NNH) for sedation from risperidone was also two. Risperidone’s NNH for extrapyramidal symptoms was six to seven. Flexible dosing with aripiprazole yielded an NNT of three, but fixed dosing led to an NNT of five to seven. The NNH for sedation with aripiprazole was 16, and the NNH for extrapyramidal symptoms was 20.

Sedation also occurred with haloperidol (NNH = 1) and amantadine (NNH = 10), and haloperidol caused extrapyramidal symptoms (NNH = 10). Weight gain occurred with risperidone, aripiprazole, and valproate.

“The reason for more compounds failing to show efficacy is not clear, but some of the negative studies had small sample sizes,” the authors noted. “Therefore, it is possible that some of these negative studies may represent false negatives,” and some of the studies used baseline ABC-I scores below the typical cutoff of at least 18 for inclusion.

The research was conducted through the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network and was supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the maternal and child health research program at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Daniel Coury has received research funding from Autism Speaks, SynapDx, and Neuren Pharmaceuticals; has consulted for Cognoa; and is a speaker for Abbott/Innovative Biopharma. Dr. Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele has received research funding from Seaside Therapeutics, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Forest, Sunovion, and SynapDx and has consulted for or advised Roche Pharmaceuticals, SynapDx, and Novartis.

Risperidone and aripiprazole, followed by N-acetylcysteine, appear most effective in treating irritability and aggression in youth with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in the February issue of Pediatrics.

“Although risperidone and aripiprazole have the strongest evidence for reducing ABC-I [Aberrant Behavioral Checklist–Irritability] in youth with autism spectrum disorders, they also have evidence for significant adverse events for a subset of patients,” reported Dr. Lawrence K. Fung of Stanford (Calif) University, and his associates (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb.;137[Suppl 2]:S124-35).

More than half of autistic individuals show significant emotion dysregulation, and about 20% have irritability or aggression at moderate to severe levels.

The authors combed Medline, PsychINFO, Embase, and review articles to identify randomized placebo-controlled trials evaluating medications to treat irritability and aggression in ASD youth, aged 2-17 years. The researchers used Aberrant Behavioral Checklist–Irritability scores as the primary endpoint in assessing effect size for improvement of emotional and behavioral symptoms in individuals with ASD.

Of 35 randomized controlled trials involving 1,673 participants included in the systematic review, 25 trials used the ABC-I, with 11 targeting irritability as the primary outcome and the other 14 targeting a different primary outcome. Five of the 11 trials targeting irritability tested the effectiveness of risperidone, while 2 tested aripiprazole, 2 tested valproate, 1 tested N-acetylcysteine, and 1 tested amantadine. Risperidone, aripiprazole, and N-acetylcysteine showed improvement in ABC-I scores with a moderate to large effect size. Valproate showed significant improvement to a lesser extent, but amantadine did not.

Among medications tested in the other 14 trials using the ABC-I, clonidine, methylphenidate, and tianeptine showed improvement with moderate effect sizes ,while venlafaxine and naltrexone showed improvement with a small effect size. Other medications tested included atomoxetine, citalopram, dextromethorphan, levetiracetam, mecamylamine, omega-3 fatty acid, and secretin. Hyperactivity and impulsivity improved in trials testing atomoxetine and dextromethorphan.

In trials using assessments other than ABC-I, risperidone and haloperidol showed effectiveness, compared with placebos, although risperidone beat haloperidol in a head-to-head trial. Some improvement in irritability also occurred with clomipramine, naltrexone, and a supplement with 19 vitamins and 9 minerals, compared with placebo.

The researchers calculated a number needed to treat (NNT) of two for risperidone at a dose between 1.2 and 1.9 mg, but the number needed to harm (NNH) for sedation from risperidone was also two. Risperidone’s NNH for extrapyramidal symptoms was six to seven. Flexible dosing with aripiprazole yielded an NNT of three, but fixed dosing led to an NNT of five to seven. The NNH for sedation with aripiprazole was 16, and the NNH for extrapyramidal symptoms was 20.

Sedation also occurred with haloperidol (NNH = 1) and amantadine (NNH = 10), and haloperidol caused extrapyramidal symptoms (NNH = 10). Weight gain occurred with risperidone, aripiprazole, and valproate.

“The reason for more compounds failing to show efficacy is not clear, but some of the negative studies had small sample sizes,” the authors noted. “Therefore, it is possible that some of these negative studies may represent false negatives,” and some of the studies used baseline ABC-I scores below the typical cutoff of at least 18 for inclusion.

The research was conducted through the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network and was supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the maternal and child health research program at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Daniel Coury has received research funding from Autism Speaks, SynapDx, and Neuren Pharmaceuticals; has consulted for Cognoa; and is a speaker for Abbott/Innovative Biopharma. Dr. Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele has received research funding from Seaside Therapeutics, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Forest, Sunovion, and SynapDx and has consulted for or advised Roche Pharmaceuticals, SynapDx, and Novartis.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Risperidone and aripiprazole most effectively treat irritability and aggression in youth with autism spectrum disorders.

Major finding: The number needed to treat was two for risperidone and three with flexible dosing of aripiprazole, with varying numbers needed to harm depending on adverse events.

Data source: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 35 randomized controlled studies assessing the effectiveness of medications in the treatment of irritability and aggression in youth with ASD.

Disclosures: The research was conducted through the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network and was supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the maternal and child health research program at Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Daniel Coury has received research funding from Autism Speaks, SynapDx, and Neuren Pharmaceuticals; has consulted for Cognoa; and is a speaker for Abbott/Innovative Biopharma. Dr. Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele has received research funding from Seaside Therapeutics, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Forest, Sunovion, and SynapDx and has consulted for or advised Roche Pharmaceuticals, SynapDx, and Novartis.

Sleep problems common among youth with ASD

The majority of children with autism spectrum disorders have sleeping problems and many take medications for sleep, but those taking medications have worse daytime behaviors and poorer quality of life, according to a study published in the February issue of Pediatrics.

“These findings underscore the need for both longitudinal and interventional studies to determine whether improvement of sleep disturbance with medications also improves daytime behaviors and quality of life,” reported Dr. Beth A. Malow of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and her associates (Pediatrics. 2016;137[S2]:e20152851H).

The researchers analyzed data from parent questionnaires and clinical forms filled out between April 2009 and December 2013 for 1,518 children, aged 4-10 years, in the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network Registry. Most of the children were white boys; only 16% were girls and 20% were nonwhite.

Although only 30% of children (P less than .0001) had sleep diagnoses in clinical reports, parents reported that 71% of the children had significant sleep problems, indicated by a score of at least 41 on the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire. The most common sleep diagnosis was sleep disturbance not otherwise specified, followed by inadequate sleep hygiene, behavioral insomnia of childhood, other sleep disorder, and organic insomnia unspecified.

One reason for the discrepancy between diagnoses and parent-reported difficulties, the researchers suggested, was that “sleep concerns may be eclipsed by other needs [of children with ASD], especially in the limited time available at a clinician visit.” At the same time, however, they note that 41 may be too low a scale cutoff for autistic children.

Among those with a sleep diagnosis, 46% were taking any medication for sleep. Just over a third (36%) of those with a sleep diagnosis took melatonin, and 14% took alpha-agonists. Only 2% of those without a sleep diagnosis took alpha-agonists, but 13% took melatonin and 15% took any medication. Other medications children took for sleep included antidepressants, antihistamines, atypical antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, beta-blockers, sedatives, iron supplements, and vitamins/dietary supplements.

The children taking medications for sleep had more insomnia, significantly lower scores for quality of life, and significantly higher scores for irritability and for internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

“It is possible that sleep disturbance itself is driving this relationship,” Dr. Malow and her associates said. “It is also possible that a clinician would be more likely to use a medication for sleep in a child with more difficult daytime behaviors” or that sleep medications influence behaviors and quality of life.

The research was supported by the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and the Maternal and Child Health Research Program to the Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Malow has received grant funding from Neurim Pharmaceuticals for a study of prolonged release melatonin (Circadin), and Dr. Reynolds has received grant funding from Mead Johnson.

The majority of children with autism spectrum disorders have sleeping problems and many take medications for sleep, but those taking medications have worse daytime behaviors and poorer quality of life, according to a study published in the February issue of Pediatrics.

“These findings underscore the need for both longitudinal and interventional studies to determine whether improvement of sleep disturbance with medications also improves daytime behaviors and quality of life,” reported Dr. Beth A. Malow of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and her associates (Pediatrics. 2016;137[S2]:e20152851H).

The researchers analyzed data from parent questionnaires and clinical forms filled out between April 2009 and December 2013 for 1,518 children, aged 4-10 years, in the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network Registry. Most of the children were white boys; only 16% were girls and 20% were nonwhite.

Although only 30% of children (P less than .0001) had sleep diagnoses in clinical reports, parents reported that 71% of the children had significant sleep problems, indicated by a score of at least 41 on the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire. The most common sleep diagnosis was sleep disturbance not otherwise specified, followed by inadequate sleep hygiene, behavioral insomnia of childhood, other sleep disorder, and organic insomnia unspecified.

One reason for the discrepancy between diagnoses and parent-reported difficulties, the researchers suggested, was that “sleep concerns may be eclipsed by other needs [of children with ASD], especially in the limited time available at a clinician visit.” At the same time, however, they note that 41 may be too low a scale cutoff for autistic children.

Among those with a sleep diagnosis, 46% were taking any medication for sleep. Just over a third (36%) of those with a sleep diagnosis took melatonin, and 14% took alpha-agonists. Only 2% of those without a sleep diagnosis took alpha-agonists, but 13% took melatonin and 15% took any medication. Other medications children took for sleep included antidepressants, antihistamines, atypical antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, beta-blockers, sedatives, iron supplements, and vitamins/dietary supplements.

The children taking medications for sleep had more insomnia, significantly lower scores for quality of life, and significantly higher scores for irritability and for internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

“It is possible that sleep disturbance itself is driving this relationship,” Dr. Malow and her associates said. “It is also possible that a clinician would be more likely to use a medication for sleep in a child with more difficult daytime behaviors” or that sleep medications influence behaviors and quality of life.

The research was supported by the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and the Maternal and Child Health Research Program to the Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Malow has received grant funding from Neurim Pharmaceuticals for a study of prolonged release melatonin (Circadin), and Dr. Reynolds has received grant funding from Mead Johnson.

The majority of children with autism spectrum disorders have sleeping problems and many take medications for sleep, but those taking medications have worse daytime behaviors and poorer quality of life, according to a study published in the February issue of Pediatrics.

“These findings underscore the need for both longitudinal and interventional studies to determine whether improvement of sleep disturbance with medications also improves daytime behaviors and quality of life,” reported Dr. Beth A. Malow of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, and her associates (Pediatrics. 2016;137[S2]:e20152851H).

The researchers analyzed data from parent questionnaires and clinical forms filled out between April 2009 and December 2013 for 1,518 children, aged 4-10 years, in the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network Registry. Most of the children were white boys; only 16% were girls and 20% were nonwhite.

Although only 30% of children (P less than .0001) had sleep diagnoses in clinical reports, parents reported that 71% of the children had significant sleep problems, indicated by a score of at least 41 on the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire. The most common sleep diagnosis was sleep disturbance not otherwise specified, followed by inadequate sleep hygiene, behavioral insomnia of childhood, other sleep disorder, and organic insomnia unspecified.

One reason for the discrepancy between diagnoses and parent-reported difficulties, the researchers suggested, was that “sleep concerns may be eclipsed by other needs [of children with ASD], especially in the limited time available at a clinician visit.” At the same time, however, they note that 41 may be too low a scale cutoff for autistic children.

Among those with a sleep diagnosis, 46% were taking any medication for sleep. Just over a third (36%) of those with a sleep diagnosis took melatonin, and 14% took alpha-agonists. Only 2% of those without a sleep diagnosis took alpha-agonists, but 13% took melatonin and 15% took any medication. Other medications children took for sleep included antidepressants, antihistamines, atypical antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, beta-blockers, sedatives, iron supplements, and vitamins/dietary supplements.

The children taking medications for sleep had more insomnia, significantly lower scores for quality of life, and significantly higher scores for irritability and for internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

“It is possible that sleep disturbance itself is driving this relationship,” Dr. Malow and her associates said. “It is also possible that a clinician would be more likely to use a medication for sleep in a child with more difficult daytime behaviors” or that sleep medications influence behaviors and quality of life.

The research was supported by the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and the Maternal and Child Health Research Program to the Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Malow has received grant funding from Neurim Pharmaceuticals for a study of prolonged release melatonin (Circadin), and Dr. Reynolds has received grant funding from Mead Johnson.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Many autistic children have sleeping problems, and many take medications for sleep.

Major finding: 71% of children with autism spectrum disorders have sleeping difficulties, and 30% have a sleep diagnosis, of whom 46% take medications for sleep.

Data source: The findings are based on analysis of questionnaires and clinical reports for 1,518 children, aged 4-10 years, in the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network Registry seen between April 2009 and December 2013.

Disclosures: The research was conducted through the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network and was supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Malow has received grant funding from Neurim Pharmaceuticals for a study of prolonged release melatonin (Circadin), and Dr. Reynolds has received grant funding from Mead Johnson.

More teens complete HPV vaccine series when parents choose reminder methods

Asking parents how they want to be reminded of the need for their child’s second dose of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine appears to increase the likelihood of their child completing the three-dose series, a recent study found.

“For the promise of the HPV vaccine to be realized, rates of vaccine initiation and series completion must be markedly increased,” wrote Dr. Allison Kempe of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and her associates. “Results of this study demonstrate that preference-based recall could have a major impact on increasing HPV series completion rates and in increasing the timeliness of full vaccination” (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2857). “The intervention was most effective for younger adolescents, and reminding the adolescent, in addition to the parent, did not increase effectiveness.”

The researchers randomly assigned three pediatric practices from Kaiser Permanente Colorado to offer usual care and four practices to the intervention, during January to June 2013. They limited the practices to those with a similar proportion of African American and Hispanic patients, a similar number of patients aged 11-17 years, and a similar proportion of Medicaid-covered patients. At the start of the study, the intervention sites had an 18% rate for the first dose of the HPV vaccine and a 6% series completion rate, compared with 20% and 7%, respectively, at the control sites.

When parents brought their children in for the first dose of the HPV vaccine, staff at the intervention practices asked the parents if they wanted to receive a reminder about the next dose. If they did, they chose whether they wanted a text message, an email, or an automated phone message (they could choose up to two) and whether they wanted their child contacted as well. Parents of 43% of the 867 eligible adolescents participated.

The researchers compared HPV vaccines series completion rates between those 374 adolescents and the 555 eligible adolescents at the control practices. At the intervention practices, 83% of the teens received the second dose, and 63% completed the vaccine series. At the control practice, 71% of the teens received the second dose, and 38% completed the series – similar to the 33% completion rate of unenrolled teens at the intervention practices. Overall, 46% of all the teens – enrolled and unenrolled – at the intervention practices completed the series, compared with 38% at the control practices – for an adjusted risk ratio of 1.22 (P less than .01)

The most popular recall method was text messaging alone, requested by 39% of parents and particularly preferred by parents of Hispanic adolescents. Both text and email were requested by 19% of parents, while 18% of parents requested email only, 9% requested text and phone, and 9% requested phone only. Only 6% requested phone and email, yet this was the only recall method associated with higher series completion rates that significantly differed from the other methods. Nearly one in five parents (19%) requested the practice to remind their child too, but these reminders had no apparent impact on completion rates.

“Whether this method [of preference-based recall] could also increase initiation of the series also should be examined, as barriers to initiation and to completion have been shown to differ,” the authors wrote.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. The authors reported no disclosures.

Asking parents how they want to be reminded of the need for their child’s second dose of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine appears to increase the likelihood of their child completing the three-dose series, a recent study found.

“For the promise of the HPV vaccine to be realized, rates of vaccine initiation and series completion must be markedly increased,” wrote Dr. Allison Kempe of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and her associates. “Results of this study demonstrate that preference-based recall could have a major impact on increasing HPV series completion rates and in increasing the timeliness of full vaccination” (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2857). “The intervention was most effective for younger adolescents, and reminding the adolescent, in addition to the parent, did not increase effectiveness.”

The researchers randomly assigned three pediatric practices from Kaiser Permanente Colorado to offer usual care and four practices to the intervention, during January to June 2013. They limited the practices to those with a similar proportion of African American and Hispanic patients, a similar number of patients aged 11-17 years, and a similar proportion of Medicaid-covered patients. At the start of the study, the intervention sites had an 18% rate for the first dose of the HPV vaccine and a 6% series completion rate, compared with 20% and 7%, respectively, at the control sites.

When parents brought their children in for the first dose of the HPV vaccine, staff at the intervention practices asked the parents if they wanted to receive a reminder about the next dose. If they did, they chose whether they wanted a text message, an email, or an automated phone message (they could choose up to two) and whether they wanted their child contacted as well. Parents of 43% of the 867 eligible adolescents participated.

The researchers compared HPV vaccines series completion rates between those 374 adolescents and the 555 eligible adolescents at the control practices. At the intervention practices, 83% of the teens received the second dose, and 63% completed the vaccine series. At the control practice, 71% of the teens received the second dose, and 38% completed the series – similar to the 33% completion rate of unenrolled teens at the intervention practices. Overall, 46% of all the teens – enrolled and unenrolled – at the intervention practices completed the series, compared with 38% at the control practices – for an adjusted risk ratio of 1.22 (P less than .01)

The most popular recall method was text messaging alone, requested by 39% of parents and particularly preferred by parents of Hispanic adolescents. Both text and email were requested by 19% of parents, while 18% of parents requested email only, 9% requested text and phone, and 9% requested phone only. Only 6% requested phone and email, yet this was the only recall method associated with higher series completion rates that significantly differed from the other methods. Nearly one in five parents (19%) requested the practice to remind their child too, but these reminders had no apparent impact on completion rates.

“Whether this method [of preference-based recall] could also increase initiation of the series also should be examined, as barriers to initiation and to completion have been shown to differ,” the authors wrote.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. The authors reported no disclosures.

Asking parents how they want to be reminded of the need for their child’s second dose of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine appears to increase the likelihood of their child completing the three-dose series, a recent study found.

“For the promise of the HPV vaccine to be realized, rates of vaccine initiation and series completion must be markedly increased,” wrote Dr. Allison Kempe of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and her associates. “Results of this study demonstrate that preference-based recall could have a major impact on increasing HPV series completion rates and in increasing the timeliness of full vaccination” (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2857). “The intervention was most effective for younger adolescents, and reminding the adolescent, in addition to the parent, did not increase effectiveness.”

The researchers randomly assigned three pediatric practices from Kaiser Permanente Colorado to offer usual care and four practices to the intervention, during January to June 2013. They limited the practices to those with a similar proportion of African American and Hispanic patients, a similar number of patients aged 11-17 years, and a similar proportion of Medicaid-covered patients. At the start of the study, the intervention sites had an 18% rate for the first dose of the HPV vaccine and a 6% series completion rate, compared with 20% and 7%, respectively, at the control sites.

When parents brought their children in for the first dose of the HPV vaccine, staff at the intervention practices asked the parents if they wanted to receive a reminder about the next dose. If they did, they chose whether they wanted a text message, an email, or an automated phone message (they could choose up to two) and whether they wanted their child contacted as well. Parents of 43% of the 867 eligible adolescents participated.

The researchers compared HPV vaccines series completion rates between those 374 adolescents and the 555 eligible adolescents at the control practices. At the intervention practices, 83% of the teens received the second dose, and 63% completed the vaccine series. At the control practice, 71% of the teens received the second dose, and 38% completed the series – similar to the 33% completion rate of unenrolled teens at the intervention practices. Overall, 46% of all the teens – enrolled and unenrolled – at the intervention practices completed the series, compared with 38% at the control practices – for an adjusted risk ratio of 1.22 (P less than .01)

The most popular recall method was text messaging alone, requested by 39% of parents and particularly preferred by parents of Hispanic adolescents. Both text and email were requested by 19% of parents, while 18% of parents requested email only, 9% requested text and phone, and 9% requested phone only. Only 6% requested phone and email, yet this was the only recall method associated with higher series completion rates that significantly differed from the other methods. Nearly one in five parents (19%) requested the practice to remind their child too, but these reminders had no apparent impact on completion rates.

“Whether this method [of preference-based recall] could also increase initiation of the series also should be examined, as barriers to initiation and to completion have been shown to differ,” the authors wrote.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. The authors reported no disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Preference-based reminders increased HPV vaccine series completion rates.

Major finding: 46% of adolescents at intervention practices completed the series, compared with 38% at practices providing usual care.

Data source: The findings are based on a cluster randomized trial of seven pediatric practices in the Kaiser Permanent Colorado system involving 1,422 patients aged 11-17 years.

Disclosures: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. The authors reported no disclosures.

Pediatric BMI increases linked to rises in blood pressure, hypertension risk

Children’s and adolescents’ risk of blood pressure increases and hypertension rose as their body mass index increased, even over a short period of a few years, according to a recent study.

“Obesity, especially severe obesity, at a young age confers an increased risk of early onset of cardiometabolic diseases such as hypertension,” wrote Emily D. Parker, Ph.D., of the HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research in Minneapolis, and her associates online (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 19. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1662). “The significant adverse effect of weight gain and obesity early in life, and over a short period of time, emphasizes the importance of developing early and effective clinical and public health strategies directed at the primary prevention of overweight and obesity.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed the health care records of 100,606 children and adolescents, aged 3-17 years, who received care from HealthPartners Medical Group in Minnesota, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, or Kaiser Permanente Northern California. All the patients had not been hypertensive within the 6 months before baseline measurements and had at least three primary care visits with blood pressure measurements between January 2007 and December 2011.

At baseline, 16% of the patients were overweight, 2% were obese, and 4% were severely obese. The majority (92%) were below the 90th percentile for their systolic blood pressure at baseline, while 4% were prehypertensive and 4% were hypertensive (at or above 95th percentile). Over a median 3.1 years of follow-up per person, 0.3% of the patients became hypertensive, translating to an incidence rate of 0.15 new cases per year.

After accounting for demographics, baseline blood pressure percentiles, year, and site, both children (aged 3-11) and adolescents with obesity were about twice as likely as children and adolescents with low healthy weights to develop hypertension (hazard ratio, 2.02 and HR, 2.20, respectively). Children and adolescents with severe obesity had more than a four times greater risk of developing hypertension (HR, 4.42 and HR, 4.46, respectively), compared with those with a low healthy weight. These were significant differences. No association appeared between those with low-normal weights at baseline and either high-normal or overweight categories during follow-up.

Forty percent of the children and 24% of the adolescents dropped from severely obese to obese during follow-up, and 45% of the children and 55% of the adolescents who were obese at baseline remained so throughout follow-up. Among children overweight at baseline, 19% became obese, 0.7% became severely obese, and 44% became a healthy weight. Among initially overweight adolescents, 13% became obese, 0.1% became severely obese, and 34% became a healthy weight.

“There was a strong association between change in BMI [body mass index] category and change in blood pressure across BMI categories in both age groups and genders,” Dr. Parker and her associates wrote. “In girls and boys 3-11 years old, both systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure percentiles increased significantly when BMI increased from normal to either overweight or obese and when it increased from overweight to obese.” Similar but greater changes were seen among the adolescents, particularly among girls aged 12-17 years.

Correspondingly, children and teens who dropped from a higher to a lower BMI category had statistically significant drops in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Risk of hypertension tripled for those with obesity at baseline who remained obese through follow-up (HR, 3.71 for children; HR, 3.64 for teens).

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Most of the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Joan C. Lo has received previous research funding from Sanofi unrelated to this study.

Children’s and adolescents’ risk of blood pressure increases and hypertension rose as their body mass index increased, even over a short period of a few years, according to a recent study.

“Obesity, especially severe obesity, at a young age confers an increased risk of early onset of cardiometabolic diseases such as hypertension,” wrote Emily D. Parker, Ph.D., of the HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research in Minneapolis, and her associates online (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 19. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1662). “The significant adverse effect of weight gain and obesity early in life, and over a short period of time, emphasizes the importance of developing early and effective clinical and public health strategies directed at the primary prevention of overweight and obesity.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed the health care records of 100,606 children and adolescents, aged 3-17 years, who received care from HealthPartners Medical Group in Minnesota, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, or Kaiser Permanente Northern California. All the patients had not been hypertensive within the 6 months before baseline measurements and had at least three primary care visits with blood pressure measurements between January 2007 and December 2011.

At baseline, 16% of the patients were overweight, 2% were obese, and 4% were severely obese. The majority (92%) were below the 90th percentile for their systolic blood pressure at baseline, while 4% were prehypertensive and 4% were hypertensive (at or above 95th percentile). Over a median 3.1 years of follow-up per person, 0.3% of the patients became hypertensive, translating to an incidence rate of 0.15 new cases per year.

After accounting for demographics, baseline blood pressure percentiles, year, and site, both children (aged 3-11) and adolescents with obesity were about twice as likely as children and adolescents with low healthy weights to develop hypertension (hazard ratio, 2.02 and HR, 2.20, respectively). Children and adolescents with severe obesity had more than a four times greater risk of developing hypertension (HR, 4.42 and HR, 4.46, respectively), compared with those with a low healthy weight. These were significant differences. No association appeared between those with low-normal weights at baseline and either high-normal or overweight categories during follow-up.

Forty percent of the children and 24% of the adolescents dropped from severely obese to obese during follow-up, and 45% of the children and 55% of the adolescents who were obese at baseline remained so throughout follow-up. Among children overweight at baseline, 19% became obese, 0.7% became severely obese, and 44% became a healthy weight. Among initially overweight adolescents, 13% became obese, 0.1% became severely obese, and 34% became a healthy weight.

“There was a strong association between change in BMI [body mass index] category and change in blood pressure across BMI categories in both age groups and genders,” Dr. Parker and her associates wrote. “In girls and boys 3-11 years old, both systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure percentiles increased significantly when BMI increased from normal to either overweight or obese and when it increased from overweight to obese.” Similar but greater changes were seen among the adolescents, particularly among girls aged 12-17 years.

Correspondingly, children and teens who dropped from a higher to a lower BMI category had statistically significant drops in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Risk of hypertension tripled for those with obesity at baseline who remained obese through follow-up (HR, 3.71 for children; HR, 3.64 for teens).

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Most of the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Joan C. Lo has received previous research funding from Sanofi unrelated to this study.

Children’s and adolescents’ risk of blood pressure increases and hypertension rose as their body mass index increased, even over a short period of a few years, according to a recent study.

“Obesity, especially severe obesity, at a young age confers an increased risk of early onset of cardiometabolic diseases such as hypertension,” wrote Emily D. Parker, Ph.D., of the HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research in Minneapolis, and her associates online (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 19. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1662). “The significant adverse effect of weight gain and obesity early in life, and over a short period of time, emphasizes the importance of developing early and effective clinical and public health strategies directed at the primary prevention of overweight and obesity.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed the health care records of 100,606 children and adolescents, aged 3-17 years, who received care from HealthPartners Medical Group in Minnesota, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, or Kaiser Permanente Northern California. All the patients had not been hypertensive within the 6 months before baseline measurements and had at least three primary care visits with blood pressure measurements between January 2007 and December 2011.

At baseline, 16% of the patients were overweight, 2% were obese, and 4% were severely obese. The majority (92%) were below the 90th percentile for their systolic blood pressure at baseline, while 4% were prehypertensive and 4% were hypertensive (at or above 95th percentile). Over a median 3.1 years of follow-up per person, 0.3% of the patients became hypertensive, translating to an incidence rate of 0.15 new cases per year.

After accounting for demographics, baseline blood pressure percentiles, year, and site, both children (aged 3-11) and adolescents with obesity were about twice as likely as children and adolescents with low healthy weights to develop hypertension (hazard ratio, 2.02 and HR, 2.20, respectively). Children and adolescents with severe obesity had more than a four times greater risk of developing hypertension (HR, 4.42 and HR, 4.46, respectively), compared with those with a low healthy weight. These were significant differences. No association appeared between those with low-normal weights at baseline and either high-normal or overweight categories during follow-up.

Forty percent of the children and 24% of the adolescents dropped from severely obese to obese during follow-up, and 45% of the children and 55% of the adolescents who were obese at baseline remained so throughout follow-up. Among children overweight at baseline, 19% became obese, 0.7% became severely obese, and 44% became a healthy weight. Among initially overweight adolescents, 13% became obese, 0.1% became severely obese, and 34% became a healthy weight.

“There was a strong association between change in BMI [body mass index] category and change in blood pressure across BMI categories in both age groups and genders,” Dr. Parker and her associates wrote. “In girls and boys 3-11 years old, both systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure percentiles increased significantly when BMI increased from normal to either overweight or obese and when it increased from overweight to obese.” Similar but greater changes were seen among the adolescents, particularly among girls aged 12-17 years.

Correspondingly, children and teens who dropped from a higher to a lower BMI category had statistically significant drops in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

Risk of hypertension tripled for those with obesity at baseline who remained obese through follow-up (HR, 3.71 for children; HR, 3.64 for teens).

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Most of the investigators had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Joan C. Lo has received previous research funding from Sanofi unrelated to this study.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: The risk of blood pressure increases and even hypertension rises with increasing BMI among youth aged 3-17 years.

Major finding: Incident hypertension risk doubled for children and adolescents with obesity (HR, 2.02 and HR, 2.20, respectively) and quadrupled for those with severe obesity (HR, 4.42 and HR, 4.46, respectively).

Data source: The findings are based on a retrospective cohort study of 100,606 individuals, aged 3-17 years, from one of three U.S. health systems who were tracked over a median 3.1 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Lo has received previous research funding from Sanofi.

Tdap effectiveness wanes rapidly in teens

The Tdap vaccine’s effectiveness against pertussis wanes so rapidly in the year after administration in teens that it provides too little protection to prevent outbreaks, according to results of a new study.

The Tdap is the booster vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis that adults and children ages 10 and older can receive. The corresponding acellular pertussis vaccine for children ages 6 and younger is the DTaP.

“Widespread Tdap vaccination, although associated with a transient decrease in pertussis incidence, did not prevent outbreaks among this population of teenagers who have only ever received acellular pertussis vaccines,” reported Dr. Nicola P. Klein and her associates at the Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center in Oakland, Calif. “This study demonstrates that despite high rates of Tdap vaccination, the growing cohort of adolescents who have only received acellular pertussis vaccines continue to be at high risk of contracting pertussis and sustaining epidemics,” they wrote online (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 5. [doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3326]).

The researchers tracked 279,493 members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California who had received only DTaP vaccines, as opposed to the whole-cell DTwP formulation previously used, from age 10 onward. These included all members who were born from 1999 onward or were born from 1996-1998 and received three infant doses of DTaP, excluding children who had previously received Tdap or had pertussis. Among these, 175,094 children received the Tdap.

For the purposes of tracking pertussis cases in unvaccinated versus vaccinated adolescents, individuals were considered unvaccinated in the analysis until they received their first Tdap, after which they were vaccinated and time since vaccination was a continuous variable. Overall, 96.5% of the children were vaccinated by their 14th birthday.

Across 792,418 person-years between January 2006 and March 2015, including 418,595 vaccinated person-years for the children who received the Tdap, 1,207 cases of pertussis occurred. The vast majority of these – 85% – occurred among those ages 10-13 years. Teens aged 14-16 years comprised 15% of the cases, and only 0.5% of cases occurred among older teens. During each year of outbreaks, incidence dropped off precipitously among the age groups composed of children who would have received the whole-cell pertussis vaccine.

For example, “pertussis incidence in the 2010 outbreak sharply declined after this peak [of 10- to 11-year-olds] and stayed low at older ages, a decline that we have previously demonstrated to be associated with the receipt of whole cell instead of acellular pertussis vaccines in infancy and childhood as well as with Tdap receipt,” the authors wrote.

The researchers estimated the Tdap’s effectiveness at 69% throughout the first year after vaccination. This dropped to 57% in the second year after vaccination and then to 25% in the third year. By 4 years or later after Tdap receipt, the vaccine’s effectiveness sat at just 9%.

For each year after Tdap vaccination, children’s risk of pertussis increased 35% (hazard ratio, 1.35), and cases were mild or moderate regardless of vaccination status. Nearly all (98%) of the children with pertussis had visited the doctor within 5 days on either side of their positive polymerase chain reaction test, 86% received a diagnosis of pertussis, and 96% received a prescription for azithromycin, except for 1 for erythromycin. In addition, 4% (50) of the cases visited the emergency department. No differences in rate of ED visits or prescriptions existed between vaccinated and unvaccinated children.

“The strategy of routinely vaccinating adolescents to prevent future disease did not prevent the 2014 epidemic, arguably because the protection afforded by a dose of Tdap was too short-lived,” the authors noted. They also pointed out that Tdap waning estimates likely also include ongoing DTaP waning.“This study was unable to disentangle the waning of Tdap effectiveness from the ongoing waning of previous doses of DTaP because the years since vaccination for Tdap and the fifth DTaP dose are closely correlated,” they wrote.

Most of the Tdap vaccines administered were Adacel (Sanofi Pasteur), but Boostrix (GlaxoSmithKline) was used as well. Waning occurred in both brands, and although not directly compared, no major differences in waning seemed to exist.

“We expect future pertussis epidemics to be larger as the cohort that has only received acellular pertussis vaccines ages,” the authors concluded. “The results in this study raise serious questions regarding the benefits of routinely administering a single dose of Tdap to every adolescent aged 11 or 12 years.”

The research was funded by Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Klein has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline for a separate pertussis vaccine effectiveness study, and Dr. Klein and one coauthor also have received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, Merck, Novartis, Protein Science, Nuron Biotech, and MedImmune. The remaining coauthors said they had no relevant financial disclosures. GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Pasteur manufacture the pertussis vaccines purchased by Kaiser Permanente for this study.

When adolescents contract whooping cough, a.k.a. pertussis, they usually don’t whoop but they cough, sometimes for 3 months. The illness is impactful for them and they are contagious to others, so the infection spreads to classmates and within families. Waning immunity after experiencing pertussis infection, after receiving the old DTwP vaccine that was discontinued in the United States years ago due to safety issues, and after receiving the newer DTaP and Tdap vaccines, has been known to occur for many years. What is new in this article is the rapidity of waning immunity in the study population.

|

Dr. Michael E. Pichichero |

First, it is important to note that the study population is from California, a state where pertussis has been circulating much more than in most other states. The exact reasons for a higher prevalence of pertussis in California are not fully understood, but a high rate of vaccine refusers may be a significant factor. Secondly, the study uses a mathematical model, so it is an estimate of waning immunity. Nevertheless, the observations alert health care providers and the community that pertussis can occur even in vaccinated persons, especially as time passes after vaccination.

The solutions are few at this time. Public health care officials are unlikely to recommend boosters more frequently than already advocated, although that is an option. Alternative formulations of Tdap to include other or additional ingredients could be a path forward, but the vaccine industry is tackling so many new diseases with vaccine development programs that a push for a better DTaP or Tdap is unlikely in the near term.

Dr. Michael E. Pichichero, specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

When adolescents contract whooping cough, a.k.a. pertussis, they usually don’t whoop but they cough, sometimes for 3 months. The illness is impactful for them and they are contagious to others, so the infection spreads to classmates and within families. Waning immunity after experiencing pertussis infection, after receiving the old DTwP vaccine that was discontinued in the United States years ago due to safety issues, and after receiving the newer DTaP and Tdap vaccines, has been known to occur for many years. What is new in this article is the rapidity of waning immunity in the study population.

|

Dr. Michael E. Pichichero |

First, it is important to note that the study population is from California, a state where pertussis has been circulating much more than in most other states. The exact reasons for a higher prevalence of pertussis in California are not fully understood, but a high rate of vaccine refusers may be a significant factor. Secondly, the study uses a mathematical model, so it is an estimate of waning immunity. Nevertheless, the observations alert health care providers and the community that pertussis can occur even in vaccinated persons, especially as time passes after vaccination.

The solutions are few at this time. Public health care officials are unlikely to recommend boosters more frequently than already advocated, although that is an option. Alternative formulations of Tdap to include other or additional ingredients could be a path forward, but the vaccine industry is tackling so many new diseases with vaccine development programs that a push for a better DTaP or Tdap is unlikely in the near term.

Dr. Michael E. Pichichero, specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

When adolescents contract whooping cough, a.k.a. pertussis, they usually don’t whoop but they cough, sometimes for 3 months. The illness is impactful for them and they are contagious to others, so the infection spreads to classmates and within families. Waning immunity after experiencing pertussis infection, after receiving the old DTwP vaccine that was discontinued in the United States years ago due to safety issues, and after receiving the newer DTaP and Tdap vaccines, has been known to occur for many years. What is new in this article is the rapidity of waning immunity in the study population.

|

Dr. Michael E. Pichichero |

First, it is important to note that the study population is from California, a state where pertussis has been circulating much more than in most other states. The exact reasons for a higher prevalence of pertussis in California are not fully understood, but a high rate of vaccine refusers may be a significant factor. Secondly, the study uses a mathematical model, so it is an estimate of waning immunity. Nevertheless, the observations alert health care providers and the community that pertussis can occur even in vaccinated persons, especially as time passes after vaccination.

The solutions are few at this time. Public health care officials are unlikely to recommend boosters more frequently than already advocated, although that is an option. Alternative formulations of Tdap to include other or additional ingredients could be a path forward, but the vaccine industry is tackling so many new diseases with vaccine development programs that a push for a better DTaP or Tdap is unlikely in the near term.

Dr. Michael E. Pichichero, specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The Tdap vaccine’s effectiveness against pertussis wanes so rapidly in the year after administration in teens that it provides too little protection to prevent outbreaks, according to results of a new study.

The Tdap is the booster vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis that adults and children ages 10 and older can receive. The corresponding acellular pertussis vaccine for children ages 6 and younger is the DTaP.

“Widespread Tdap vaccination, although associated with a transient decrease in pertussis incidence, did not prevent outbreaks among this population of teenagers who have only ever received acellular pertussis vaccines,” reported Dr. Nicola P. Klein and her associates at the Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center in Oakland, Calif. “This study demonstrates that despite high rates of Tdap vaccination, the growing cohort of adolescents who have only received acellular pertussis vaccines continue to be at high risk of contracting pertussis and sustaining epidemics,” they wrote online (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb 5. [doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3326]).