User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Early metformin minimizes antipsychotic-induced weight gain

MAR DEL PLATA, ARGENTINA – , according to a new evidence-based Irish guideline for the management of this common complication in adults with psychoses who are taking medications.

The document was discussed during one of the sessions of the XXXV Argentine Congress of Psychiatry of the Association of Argentine Psychiatrists. The document also was presented by one of its authors at the European Congress on Obesity 2022.

The guideline encourages psychiatrists not to underestimate the adverse metabolic effects of their treatments and encourages them to contemplate and carry out this prevention and management strategy, commented María Delia Michat, PhD, professor of clinical psychiatry and psychopharmacology at the APSA Postgraduate Training Institute, Buenos Aires.

“Although it is always good to work as a team, it is usually we psychiatrists who coordinate the pharmacological treatment of our patients, and we have to know how to manage drugs that can prevent cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Michat said in an interview.

“The new guideline is helpful because it protocolizes the use of metformin, which is the cheapest drug and has the most evidence for antipsychotic-induced weight gain,” she added.

Avoiding metabolic syndrome

In patients with schizophrenia, obesity rates are 40% higher than in the general population, and 80% of patients develop weight gain after their first treatment, noted Dr. Michat. “Right away, weight gain is seen in the first month. And it is a serious problem, because patients with schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder already have an increased risk of premature mortality, especially from cardiovascular diseases, and they have an increased risk of metabolic syndrome. And we sometimes give drugs that further increase that risk,” she said.

Being overweight is a major criterion for defining metabolic syndrome. Dr. Michat noted that, among the antipsychotic drugs that increase weight the most are clozapine, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, quetiapine, and risperidone, in addition to other psychoactive drugs, such as valproic acid, lithium, mirtazapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Several clinical trials, such as a pioneering Chinese study from 2008, have shown the potential of metformin to mitigate the weight gain induced by this type of drug.

However, Dr. Michat noted that so far the major guidelines (for example, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments [CANMAT]/International Society for Bipolar Disorders [ISBD] for bipolar disorder and the American Psychiatric Association [APA] for schizophrenia) “say very little” on how to address this complication. They propose what she defined as a “problematic” order of action in which the initial emphasis is on promoting lifestyle changes, which are difficult for these patients to carry out, as well as general proposals for changing medication (which is not simple to implement when the patient’s condition is stabilized) and eventual consultation with a clinician to start therapy with metformin or other drugs, such as liraglutide, semaglutide, and topiramate.

The new clinical practice guideline, which was published in Evidence-Based Mental Health (of the BMJ journal group), was written by a multidisciplinary team of pharmacists, psychiatrists, and mental health nurses from Ireland. It aims to fill that gap. The investigators reviewed 1,270 scientific articles and analyzed 26 of them in depth, including seven randomized clinical trials and a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis. The authors made a “strong” recommendation, for which there was moderate-quality evidence, that for patients for whom a lifestyle intervention is unacceptable or inappropriate the use of metformin is an “alternative first-line intervention” for antipsychotic drug–induced weight gain.

Likewise, as a strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence, the guidance encourages the use of metformin when nonpharmacologic intervention does not seem to be effective.

The guideline also says it is preferable to start metformin early for patients who gain more than 7% of their baseline weight within the first month of antipsychotic treatment. It also endorses metformin when weight gain is established.

Other recommendations include evaluating baseline kidney function before starting metformin treatment and suggest a dose adjustment when the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The guidance says the use of metformin is contraindicated for patients in whom eGFR is <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The proposed starting dosage is 500 mg twice per day with meals, with increments of 500 mg every 1-2 weeks until reaching a target dose of 2,000 mg/day. The guidance recommends that consideration always be given to individual tolerability and efficacy.

Treatment goals should be personalized and agreed upon with patients. In the case of early intervention, the guideline proposes initially stabilizing the weight gained or, if possible, reverse excess weight. When weight gain is established, the goal would be to lose at least 5% of the weight within the next 6 months.

The authors also recommend monitoring kidney function annually, as well as vitamin B12 levels and individual tolerability and compliance. Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be managed by dose reduction or slower dose titration. The risk of lactic acidosis, which affects 4.3 per 100,000 person-years among those taking metformin, can be attenuated by adjusting the dose according to kidney function or avoiding prescribing it to patients who have a history of alcohol abuse or who are receiving treatment that may interact with the drug.

Validating pharmacologic management

The lead author of the new guideline, Ita Fitzgerald, a teacher in clinical pharmacy and senior pharmacist at St. Patrick’s Mental Health Services in Dublin, pointed out that there is a bias toward not using drugs for weight management and shifting the responsibility onto the patients themselves, something that is very often out of their control.

“The purpose of the guideline was to decide on a range of criteria to maximize the use of metformin, to recognize that for many people, pharmacological management is a valid and important option that could and should be more widely used and to provide precise and practical guidance to physicians to facilitate a more widespread use,” Ms. Fitzgerald said in an interview.

According to Fitzgerald, who is pursuing her doctorate at University College Cork (Ireland), one of the most outstanding results of the work is that it highlights that the main benefit of metformin is to flatten rather than reverse antipsychotic-induced weight gain and that indicating it late can nullify that effect.

“In all the recommendations, we try very hard to shift the focus from metformin’s role as a weight reversal agent to one as a weight management agent that should be used early in treatment, which is when most weight gain occurs. If metformin succeeds in flattening that increase, that’s a huge potential benefit for an inexpensive and easily accessible drug. When people have already established weight gain, metformin may not be enough and alternative treatments should be used,” she said.

In addition to its effects on weight, metformin has many other potential health benefits. Of particular importance is that it reduces hyperphagia-mediated antipsychotic-induced weight gain, Ms. Fitzgerald pointed out.

“This is subjectively very important for patients and provides a more positive experience when taking antipsychotics. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain is one of the main reasons for premature discontinuation or incomplete adherence to these drugs and therefore needs to be addressed proactively,” she concluded.

Ms. Fitzgerald and Dr. Michat have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition.

MAR DEL PLATA, ARGENTINA – , according to a new evidence-based Irish guideline for the management of this common complication in adults with psychoses who are taking medications.

The document was discussed during one of the sessions of the XXXV Argentine Congress of Psychiatry of the Association of Argentine Psychiatrists. The document also was presented by one of its authors at the European Congress on Obesity 2022.

The guideline encourages psychiatrists not to underestimate the adverse metabolic effects of their treatments and encourages them to contemplate and carry out this prevention and management strategy, commented María Delia Michat, PhD, professor of clinical psychiatry and psychopharmacology at the APSA Postgraduate Training Institute, Buenos Aires.

“Although it is always good to work as a team, it is usually we psychiatrists who coordinate the pharmacological treatment of our patients, and we have to know how to manage drugs that can prevent cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Michat said in an interview.

“The new guideline is helpful because it protocolizes the use of metformin, which is the cheapest drug and has the most evidence for antipsychotic-induced weight gain,” she added.

Avoiding metabolic syndrome

In patients with schizophrenia, obesity rates are 40% higher than in the general population, and 80% of patients develop weight gain after their first treatment, noted Dr. Michat. “Right away, weight gain is seen in the first month. And it is a serious problem, because patients with schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder already have an increased risk of premature mortality, especially from cardiovascular diseases, and they have an increased risk of metabolic syndrome. And we sometimes give drugs that further increase that risk,” she said.

Being overweight is a major criterion for defining metabolic syndrome. Dr. Michat noted that, among the antipsychotic drugs that increase weight the most are clozapine, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, quetiapine, and risperidone, in addition to other psychoactive drugs, such as valproic acid, lithium, mirtazapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Several clinical trials, such as a pioneering Chinese study from 2008, have shown the potential of metformin to mitigate the weight gain induced by this type of drug.

However, Dr. Michat noted that so far the major guidelines (for example, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments [CANMAT]/International Society for Bipolar Disorders [ISBD] for bipolar disorder and the American Psychiatric Association [APA] for schizophrenia) “say very little” on how to address this complication. They propose what she defined as a “problematic” order of action in which the initial emphasis is on promoting lifestyle changes, which are difficult for these patients to carry out, as well as general proposals for changing medication (which is not simple to implement when the patient’s condition is stabilized) and eventual consultation with a clinician to start therapy with metformin or other drugs, such as liraglutide, semaglutide, and topiramate.

The new clinical practice guideline, which was published in Evidence-Based Mental Health (of the BMJ journal group), was written by a multidisciplinary team of pharmacists, psychiatrists, and mental health nurses from Ireland. It aims to fill that gap. The investigators reviewed 1,270 scientific articles and analyzed 26 of them in depth, including seven randomized clinical trials and a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis. The authors made a “strong” recommendation, for which there was moderate-quality evidence, that for patients for whom a lifestyle intervention is unacceptable or inappropriate the use of metformin is an “alternative first-line intervention” for antipsychotic drug–induced weight gain.

Likewise, as a strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence, the guidance encourages the use of metformin when nonpharmacologic intervention does not seem to be effective.

The guideline also says it is preferable to start metformin early for patients who gain more than 7% of their baseline weight within the first month of antipsychotic treatment. It also endorses metformin when weight gain is established.

Other recommendations include evaluating baseline kidney function before starting metformin treatment and suggest a dose adjustment when the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The guidance says the use of metformin is contraindicated for patients in whom eGFR is <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The proposed starting dosage is 500 mg twice per day with meals, with increments of 500 mg every 1-2 weeks until reaching a target dose of 2,000 mg/day. The guidance recommends that consideration always be given to individual tolerability and efficacy.

Treatment goals should be personalized and agreed upon with patients. In the case of early intervention, the guideline proposes initially stabilizing the weight gained or, if possible, reverse excess weight. When weight gain is established, the goal would be to lose at least 5% of the weight within the next 6 months.

The authors also recommend monitoring kidney function annually, as well as vitamin B12 levels and individual tolerability and compliance. Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be managed by dose reduction or slower dose titration. The risk of lactic acidosis, which affects 4.3 per 100,000 person-years among those taking metformin, can be attenuated by adjusting the dose according to kidney function or avoiding prescribing it to patients who have a history of alcohol abuse or who are receiving treatment that may interact with the drug.

Validating pharmacologic management

The lead author of the new guideline, Ita Fitzgerald, a teacher in clinical pharmacy and senior pharmacist at St. Patrick’s Mental Health Services in Dublin, pointed out that there is a bias toward not using drugs for weight management and shifting the responsibility onto the patients themselves, something that is very often out of their control.

“The purpose of the guideline was to decide on a range of criteria to maximize the use of metformin, to recognize that for many people, pharmacological management is a valid and important option that could and should be more widely used and to provide precise and practical guidance to physicians to facilitate a more widespread use,” Ms. Fitzgerald said in an interview.

According to Fitzgerald, who is pursuing her doctorate at University College Cork (Ireland), one of the most outstanding results of the work is that it highlights that the main benefit of metformin is to flatten rather than reverse antipsychotic-induced weight gain and that indicating it late can nullify that effect.

“In all the recommendations, we try very hard to shift the focus from metformin’s role as a weight reversal agent to one as a weight management agent that should be used early in treatment, which is when most weight gain occurs. If metformin succeeds in flattening that increase, that’s a huge potential benefit for an inexpensive and easily accessible drug. When people have already established weight gain, metformin may not be enough and alternative treatments should be used,” she said.

In addition to its effects on weight, metformin has many other potential health benefits. Of particular importance is that it reduces hyperphagia-mediated antipsychotic-induced weight gain, Ms. Fitzgerald pointed out.

“This is subjectively very important for patients and provides a more positive experience when taking antipsychotics. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain is one of the main reasons for premature discontinuation or incomplete adherence to these drugs and therefore needs to be addressed proactively,” she concluded.

Ms. Fitzgerald and Dr. Michat have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition.

MAR DEL PLATA, ARGENTINA – , according to a new evidence-based Irish guideline for the management of this common complication in adults with psychoses who are taking medications.

The document was discussed during one of the sessions of the XXXV Argentine Congress of Psychiatry of the Association of Argentine Psychiatrists. The document also was presented by one of its authors at the European Congress on Obesity 2022.

The guideline encourages psychiatrists not to underestimate the adverse metabolic effects of their treatments and encourages them to contemplate and carry out this prevention and management strategy, commented María Delia Michat, PhD, professor of clinical psychiatry and psychopharmacology at the APSA Postgraduate Training Institute, Buenos Aires.

“Although it is always good to work as a team, it is usually we psychiatrists who coordinate the pharmacological treatment of our patients, and we have to know how to manage drugs that can prevent cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Michat said in an interview.

“The new guideline is helpful because it protocolizes the use of metformin, which is the cheapest drug and has the most evidence for antipsychotic-induced weight gain,” she added.

Avoiding metabolic syndrome

In patients with schizophrenia, obesity rates are 40% higher than in the general population, and 80% of patients develop weight gain after their first treatment, noted Dr. Michat. “Right away, weight gain is seen in the first month. And it is a serious problem, because patients with schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder already have an increased risk of premature mortality, especially from cardiovascular diseases, and they have an increased risk of metabolic syndrome. And we sometimes give drugs that further increase that risk,” she said.

Being overweight is a major criterion for defining metabolic syndrome. Dr. Michat noted that, among the antipsychotic drugs that increase weight the most are clozapine, olanzapine, chlorpromazine, quetiapine, and risperidone, in addition to other psychoactive drugs, such as valproic acid, lithium, mirtazapine, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Several clinical trials, such as a pioneering Chinese study from 2008, have shown the potential of metformin to mitigate the weight gain induced by this type of drug.

However, Dr. Michat noted that so far the major guidelines (for example, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments [CANMAT]/International Society for Bipolar Disorders [ISBD] for bipolar disorder and the American Psychiatric Association [APA] for schizophrenia) “say very little” on how to address this complication. They propose what she defined as a “problematic” order of action in which the initial emphasis is on promoting lifestyle changes, which are difficult for these patients to carry out, as well as general proposals for changing medication (which is not simple to implement when the patient’s condition is stabilized) and eventual consultation with a clinician to start therapy with metformin or other drugs, such as liraglutide, semaglutide, and topiramate.

The new clinical practice guideline, which was published in Evidence-Based Mental Health (of the BMJ journal group), was written by a multidisciplinary team of pharmacists, psychiatrists, and mental health nurses from Ireland. It aims to fill that gap. The investigators reviewed 1,270 scientific articles and analyzed 26 of them in depth, including seven randomized clinical trials and a 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis. The authors made a “strong” recommendation, for which there was moderate-quality evidence, that for patients for whom a lifestyle intervention is unacceptable or inappropriate the use of metformin is an “alternative first-line intervention” for antipsychotic drug–induced weight gain.

Likewise, as a strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence, the guidance encourages the use of metformin when nonpharmacologic intervention does not seem to be effective.

The guideline also says it is preferable to start metformin early for patients who gain more than 7% of their baseline weight within the first month of antipsychotic treatment. It also endorses metformin when weight gain is established.

Other recommendations include evaluating baseline kidney function before starting metformin treatment and suggest a dose adjustment when the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The guidance says the use of metformin is contraindicated for patients in whom eGFR is <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2. The proposed starting dosage is 500 mg twice per day with meals, with increments of 500 mg every 1-2 weeks until reaching a target dose of 2,000 mg/day. The guidance recommends that consideration always be given to individual tolerability and efficacy.

Treatment goals should be personalized and agreed upon with patients. In the case of early intervention, the guideline proposes initially stabilizing the weight gained or, if possible, reverse excess weight. When weight gain is established, the goal would be to lose at least 5% of the weight within the next 6 months.

The authors also recommend monitoring kidney function annually, as well as vitamin B12 levels and individual tolerability and compliance. Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be managed by dose reduction or slower dose titration. The risk of lactic acidosis, which affects 4.3 per 100,000 person-years among those taking metformin, can be attenuated by adjusting the dose according to kidney function or avoiding prescribing it to patients who have a history of alcohol abuse or who are receiving treatment that may interact with the drug.

Validating pharmacologic management

The lead author of the new guideline, Ita Fitzgerald, a teacher in clinical pharmacy and senior pharmacist at St. Patrick’s Mental Health Services in Dublin, pointed out that there is a bias toward not using drugs for weight management and shifting the responsibility onto the patients themselves, something that is very often out of their control.

“The purpose of the guideline was to decide on a range of criteria to maximize the use of metformin, to recognize that for many people, pharmacological management is a valid and important option that could and should be more widely used and to provide precise and practical guidance to physicians to facilitate a more widespread use,” Ms. Fitzgerald said in an interview.

According to Fitzgerald, who is pursuing her doctorate at University College Cork (Ireland), one of the most outstanding results of the work is that it highlights that the main benefit of metformin is to flatten rather than reverse antipsychotic-induced weight gain and that indicating it late can nullify that effect.

“In all the recommendations, we try very hard to shift the focus from metformin’s role as a weight reversal agent to one as a weight management agent that should be used early in treatment, which is when most weight gain occurs. If metformin succeeds in flattening that increase, that’s a huge potential benefit for an inexpensive and easily accessible drug. When people have already established weight gain, metformin may not be enough and alternative treatments should be used,” she said.

In addition to its effects on weight, metformin has many other potential health benefits. Of particular importance is that it reduces hyperphagia-mediated antipsychotic-induced weight gain, Ms. Fitzgerald pointed out.

“This is subjectively very important for patients and provides a more positive experience when taking antipsychotics. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain is one of the main reasons for premature discontinuation or incomplete adherence to these drugs and therefore needs to be addressed proactively,” she concluded.

Ms. Fitzgerald and Dr. Michat have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish edition.

Refugees have a high burden of chronic pain associated with mental illness

The study covered in this summary was published in researchsquare.com and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Anxiety, , and PTSD are associated with higher levels of chronic pain in the refugee population studied.

- Being a male refugee is associated more strongly with anxiety and depression leading to functional impairment than being a woman. Being a woman is associated with higher odds of chronic pain. Gender acted as an effect modifier between mental illness and functional impairment.

- Future research aimed toward harmonizing and standardizing pain measurement to measure its effect on health burden is needed. Pain should be understood under an ethnocultural construct to enhance transcultural validity.

Why this matters

- The present cross-sectional survey of adult refugees from Syria resettled in Norway is only one of a few studies investigating the burden of chronic pain and how it relates to mental ill health in a general refugee population. Elevated rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety have been repeatedly found in refugee populations, and high levels of pain have also been documented.

- Attention to the association between chronic pain and mental health should be made by personnel working with refugees. Because of the gender-specific associations between mental illness and functional impairment, initiatives addressing mental health, chronic pain, or functional impairment in refugee populations should consider gender when tailoring their content and outreach.

Study design

- The study involved a cross-sectional, postal survey questionnaire of participants randomly drawn from full population registries in Norway. There was an initial low response. Invitations were sent out in November 2018 and did not close until September 2019. Several efforts were made to boost participation, including one postal or telephone reminder to all nonresponders.

- Participants were refugee adults from Syria aged 18 and older who arrived in Norway between 2015 and 2017. Gender was tested as an effect modifier.

- Chronic pain was measured with 10 items on the questionnaire and was defined as pain for 3 or more consecutive months in the last year. It included both musculoskeletal pain and pain in five other body regions (stomach, head, genital area, chest, other).

- Anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms were measured with the 25-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist, the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, and the Refugee Trauma History Checklist.

- Questionnaires on perceived general health regarding refugee perceptions of their own health, and functional impairment affecting daily activities because of illness, disability, and mental health were adapted from the European Social Survey 2010.

Key results

- A total of 902 participants who responded to the questionnaire were included in the study from roughly 10,000 invitations, giving a participation rate of about 10%, with no differences in gender distribution.

- The overall prevalence of severe chronic pain was 43.1%, and overall perception of poor general health was 39.9%.

- There was a strong association of chronic pain with all mental illness measured, poor perceived general health, and functional impairment (P < .001). All mental health variables were associated with increased odds of chronic pain (anxiety odds ratio), 2.42; depression, OR, 2.28; PTSD, OR, 1.97; all OR fully adjusted).

- Chronic pain was associated with poor perceived general health and functional impairment with no difference across gender. Mental health showed weaker association with poor perceived general health than chronic pain.

- Syrian men with mental health had three times higher odds of functional impairment. For women, there was no evidence of association between any of the mental ill health variables and functional impairment. Being a woman was associated with chronic pain and poor perceived general health but not functional impairment.

- Being a woman was associated with 50% higher odds of chronic pain in both unadjusted and adjusted models.

Limitations

- With a 10% response rate, selection bias in this cross-sectional study may have been present.

- The cross-sectional design of the study limits causality.

- The validity of the survey is questionable because of transcultural construct regarding pain and mental illness.

- Regression models were built with data at hand. Without preregistered plans for data handling, the findings should be viewed as exploratory with a risk for false-positive findings.

Disclosures

- No external funding was received. The study was funded by the Norwegian Center for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies.

- None of the authors disclosed relevant financial relationships.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “Chronic pain, mental health and functional impairment in adult refugees from Syria resettled in Norway: a cross-sectional study,” written by researchers at the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies in Oslo, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health in Oslo, and the Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City on Research Square. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on researchsquare.com. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study covered in this summary was published in researchsquare.com and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Anxiety, , and PTSD are associated with higher levels of chronic pain in the refugee population studied.

- Being a male refugee is associated more strongly with anxiety and depression leading to functional impairment than being a woman. Being a woman is associated with higher odds of chronic pain. Gender acted as an effect modifier between mental illness and functional impairment.

- Future research aimed toward harmonizing and standardizing pain measurement to measure its effect on health burden is needed. Pain should be understood under an ethnocultural construct to enhance transcultural validity.

Why this matters

- The present cross-sectional survey of adult refugees from Syria resettled in Norway is only one of a few studies investigating the burden of chronic pain and how it relates to mental ill health in a general refugee population. Elevated rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety have been repeatedly found in refugee populations, and high levels of pain have also been documented.

- Attention to the association between chronic pain and mental health should be made by personnel working with refugees. Because of the gender-specific associations between mental illness and functional impairment, initiatives addressing mental health, chronic pain, or functional impairment in refugee populations should consider gender when tailoring their content and outreach.

Study design

- The study involved a cross-sectional, postal survey questionnaire of participants randomly drawn from full population registries in Norway. There was an initial low response. Invitations were sent out in November 2018 and did not close until September 2019. Several efforts were made to boost participation, including one postal or telephone reminder to all nonresponders.

- Participants were refugee adults from Syria aged 18 and older who arrived in Norway between 2015 and 2017. Gender was tested as an effect modifier.

- Chronic pain was measured with 10 items on the questionnaire and was defined as pain for 3 or more consecutive months in the last year. It included both musculoskeletal pain and pain in five other body regions (stomach, head, genital area, chest, other).

- Anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms were measured with the 25-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist, the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, and the Refugee Trauma History Checklist.

- Questionnaires on perceived general health regarding refugee perceptions of their own health, and functional impairment affecting daily activities because of illness, disability, and mental health were adapted from the European Social Survey 2010.

Key results

- A total of 902 participants who responded to the questionnaire were included in the study from roughly 10,000 invitations, giving a participation rate of about 10%, with no differences in gender distribution.

- The overall prevalence of severe chronic pain was 43.1%, and overall perception of poor general health was 39.9%.

- There was a strong association of chronic pain with all mental illness measured, poor perceived general health, and functional impairment (P < .001). All mental health variables were associated with increased odds of chronic pain (anxiety odds ratio), 2.42; depression, OR, 2.28; PTSD, OR, 1.97; all OR fully adjusted).

- Chronic pain was associated with poor perceived general health and functional impairment with no difference across gender. Mental health showed weaker association with poor perceived general health than chronic pain.

- Syrian men with mental health had three times higher odds of functional impairment. For women, there was no evidence of association between any of the mental ill health variables and functional impairment. Being a woman was associated with chronic pain and poor perceived general health but not functional impairment.

- Being a woman was associated with 50% higher odds of chronic pain in both unadjusted and adjusted models.

Limitations

- With a 10% response rate, selection bias in this cross-sectional study may have been present.

- The cross-sectional design of the study limits causality.

- The validity of the survey is questionable because of transcultural construct regarding pain and mental illness.

- Regression models were built with data at hand. Without preregistered plans for data handling, the findings should be viewed as exploratory with a risk for false-positive findings.

Disclosures

- No external funding was received. The study was funded by the Norwegian Center for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies.

- None of the authors disclosed relevant financial relationships.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “Chronic pain, mental health and functional impairment in adult refugees from Syria resettled in Norway: a cross-sectional study,” written by researchers at the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies in Oslo, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health in Oslo, and the Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City on Research Square. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on researchsquare.com. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study covered in this summary was published in researchsquare.com and has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- Anxiety, , and PTSD are associated with higher levels of chronic pain in the refugee population studied.

- Being a male refugee is associated more strongly with anxiety and depression leading to functional impairment than being a woman. Being a woman is associated with higher odds of chronic pain. Gender acted as an effect modifier between mental illness and functional impairment.

- Future research aimed toward harmonizing and standardizing pain measurement to measure its effect on health burden is needed. Pain should be understood under an ethnocultural construct to enhance transcultural validity.

Why this matters

- The present cross-sectional survey of adult refugees from Syria resettled in Norway is only one of a few studies investigating the burden of chronic pain and how it relates to mental ill health in a general refugee population. Elevated rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety have been repeatedly found in refugee populations, and high levels of pain have also been documented.

- Attention to the association between chronic pain and mental health should be made by personnel working with refugees. Because of the gender-specific associations between mental illness and functional impairment, initiatives addressing mental health, chronic pain, or functional impairment in refugee populations should consider gender when tailoring their content and outreach.

Study design

- The study involved a cross-sectional, postal survey questionnaire of participants randomly drawn from full population registries in Norway. There was an initial low response. Invitations were sent out in November 2018 and did not close until September 2019. Several efforts were made to boost participation, including one postal or telephone reminder to all nonresponders.

- Participants were refugee adults from Syria aged 18 and older who arrived in Norway between 2015 and 2017. Gender was tested as an effect modifier.

- Chronic pain was measured with 10 items on the questionnaire and was defined as pain for 3 or more consecutive months in the last year. It included both musculoskeletal pain and pain in five other body regions (stomach, head, genital area, chest, other).

- Anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms were measured with the 25-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist, the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, and the Refugee Trauma History Checklist.

- Questionnaires on perceived general health regarding refugee perceptions of their own health, and functional impairment affecting daily activities because of illness, disability, and mental health were adapted from the European Social Survey 2010.

Key results

- A total of 902 participants who responded to the questionnaire were included in the study from roughly 10,000 invitations, giving a participation rate of about 10%, with no differences in gender distribution.

- The overall prevalence of severe chronic pain was 43.1%, and overall perception of poor general health was 39.9%.

- There was a strong association of chronic pain with all mental illness measured, poor perceived general health, and functional impairment (P < .001). All mental health variables were associated with increased odds of chronic pain (anxiety odds ratio), 2.42; depression, OR, 2.28; PTSD, OR, 1.97; all OR fully adjusted).

- Chronic pain was associated with poor perceived general health and functional impairment with no difference across gender. Mental health showed weaker association with poor perceived general health than chronic pain.

- Syrian men with mental health had three times higher odds of functional impairment. For women, there was no evidence of association between any of the mental ill health variables and functional impairment. Being a woman was associated with chronic pain and poor perceived general health but not functional impairment.

- Being a woman was associated with 50% higher odds of chronic pain in both unadjusted and adjusted models.

Limitations

- With a 10% response rate, selection bias in this cross-sectional study may have been present.

- The cross-sectional design of the study limits causality.

- The validity of the survey is questionable because of transcultural construct regarding pain and mental illness.

- Regression models were built with data at hand. Without preregistered plans for data handling, the findings should be viewed as exploratory with a risk for false-positive findings.

Disclosures

- No external funding was received. The study was funded by the Norwegian Center for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies.

- None of the authors disclosed relevant financial relationships.

This is a summary of a preprint research study, “Chronic pain, mental health and functional impairment in adult refugees from Syria resettled in Norway: a cross-sectional study,” written by researchers at the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies in Oslo, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health in Oslo, and the Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City on Research Square. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on researchsquare.com. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Psilocybin benefits in severe depression observed up to 12 weeks

NEW ORLEANS –

“This is easily the largest study of a psychedelic drug employing modern randomized controlled trial methodology [with] 22 sites and 10 countries, so it’s not your typical phase 2 trial,” the study’s lead author, Guy M. Goodwin, MD, emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, England, said in an interview.

“Importantly, 94% of the patients in the study were psilocybin naive, which is very important for generalizability,” Dr. Goodwin noted.

Long used as psychedelic ‘magic mushrooms,’ psilocybin has gained increased interest in psychiatry in recent years as a potential treatment for severe depression after showing benefits in patients with life-threatening cancers and others with major depressive disorder (MDD).

To put the therapy to test in a more rigorous, randomized trial, Dr. Goodwin and colleagues conducted the phase 2b study of a proprietary synthetic formulation of psilocybin, COMP360 (COMPASS Pathways), recruiting 233 patients with treatment-resistant depression at 22 centers.

The study was presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

After a 2-week washout period following the discontinuation of antidepressants, the patients were randomized to one of three groups: A single dose of 25 mg (n = 79), 10 mg (n = 75), or a subtherapeutic comparison of 1 mg (n = 79).

The psilocybin was administered in the presence of specially trained therapists who provided psychological support before, during, and after the 6- to 8-hour session.

Patients were then asked to refrain from antidepressant use for at least 3 weeks following the session, and had periodic follow-up for 12 weeks.

For the primary endpoint, those in the 25-mg group, but not the 10-mg dose, showed a significantly greater reduction in depression from baseline versus the 1-mg group on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale at week 3 (MADRS; -6.6; P < .001).

The benefit was observed at day 2 and week 1 following administration, “confirming the rapid-acting character of the effect,” the investigators reported.

Sustained responses, defined as at least a 50% change from baseline in MADRS total score, were further observed up to week 12 among 20.3% in the 25-mg group and among 5.3% in the 10-mg groups versus 10.1% in the 1-mg group.

On the day of psilocybin treatment, the treatment-emergent side effects that were reported were headache, nausea, and dizziness, with event rates of 83.5% in the 25-mg group, 74.7% in the 10-mg group, and 72.2% in the 1-mg group.

One participant in the 25-mg group experienced acute anxiety and was treated with lorazepam.

The incidence of treatment-emergent serious adverse events from day 2 to week 3 was 6.3% (five patients) in the 25-mg group, 8.0% (six patients) in the 10-mg group, and 1.3% (one patient) in the 1-mg group.

Serious AEs included suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury among two patients each in the 25-mg group, while in the 10-mg group, two had suicidal ideation and one had hospitalization for severe depression.

There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of vital signs or clinical laboratory tests.

Of note, two patients in the 25-mg group had a change from baseline in QTcF >60 msec on day 2. For one patient, the increase was within normal range, and the other had a QTcF interval duration >500 msec on day 2, but levels returned to normal by day 9.

Improvements in context

Dr. Goodwin noted that the improvements were swift and impressive when compared with those of the STAR*D trial, which is the largest prospective study of treatment outcomes in patients with MDD.

“In the STAR*D trial, third- and fourth-step treatments showed low response rates of under 15% and high relapse rates,” Dr. Goodwin said. “By comparison, our response rates at 12 weeks were 20%-25%, so almost double that seen for probably equivalent treatment steps in STAR*D, with a single treatment with 25 mg, and no additional antidepressant, so no side effect burden.

“We hope to follow up enough of these patients [in the new study] to get some idea of relapse rates,” Dr. Goodwin added. “These have been low in comparable studies with MDD patients: We will see.”

Commenting on the research, Balwinder Singh, MD, of the department of psychiatry and psychology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said the study represents a valuable addition to needed evidence on psilocybin – with some caveats.

“This study adds to the emerging evidence base of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression, at least in the short term,” he said in an interview. “I think the challenge in the real world would be to have access to 6-8 hours of therapy with psilocybin when patients struggle to find good therapists who could provide even weekly therapy for an hour.”

In addition, Dr. Singh questioned the durability of a single dose of psilocybin in the long term, noting a recent study (N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032994) that evaluated two doses of psilocybin (25 mg) 3 weeks apart, and failed to show any significant difference compared with the serotonergic antidepressant escitalopram at 6 weeks.

He further expressed concern about the emergence of suicidal behaviors in some patients, as well as the prolongation of QTc > 60 msec reported in the two patients.

“This is something to be carefully assessed in future studies, due to the risk of arrhythmias,” Dr. Singh said.

The study was sponsored by COMPASS Pathfinder Limited. Dr. Goodwin is chief medical officer for COMPASS Pathways. Dr. Singh had no disclosures to report.

NEW ORLEANS –

“This is easily the largest study of a psychedelic drug employing modern randomized controlled trial methodology [with] 22 sites and 10 countries, so it’s not your typical phase 2 trial,” the study’s lead author, Guy M. Goodwin, MD, emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, England, said in an interview.

“Importantly, 94% of the patients in the study were psilocybin naive, which is very important for generalizability,” Dr. Goodwin noted.

Long used as psychedelic ‘magic mushrooms,’ psilocybin has gained increased interest in psychiatry in recent years as a potential treatment for severe depression after showing benefits in patients with life-threatening cancers and others with major depressive disorder (MDD).

To put the therapy to test in a more rigorous, randomized trial, Dr. Goodwin and colleagues conducted the phase 2b study of a proprietary synthetic formulation of psilocybin, COMP360 (COMPASS Pathways), recruiting 233 patients with treatment-resistant depression at 22 centers.

The study was presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

After a 2-week washout period following the discontinuation of antidepressants, the patients were randomized to one of three groups: A single dose of 25 mg (n = 79), 10 mg (n = 75), or a subtherapeutic comparison of 1 mg (n = 79).

The psilocybin was administered in the presence of specially trained therapists who provided psychological support before, during, and after the 6- to 8-hour session.

Patients were then asked to refrain from antidepressant use for at least 3 weeks following the session, and had periodic follow-up for 12 weeks.

For the primary endpoint, those in the 25-mg group, but not the 10-mg dose, showed a significantly greater reduction in depression from baseline versus the 1-mg group on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale at week 3 (MADRS; -6.6; P < .001).

The benefit was observed at day 2 and week 1 following administration, “confirming the rapid-acting character of the effect,” the investigators reported.

Sustained responses, defined as at least a 50% change from baseline in MADRS total score, were further observed up to week 12 among 20.3% in the 25-mg group and among 5.3% in the 10-mg groups versus 10.1% in the 1-mg group.

On the day of psilocybin treatment, the treatment-emergent side effects that were reported were headache, nausea, and dizziness, with event rates of 83.5% in the 25-mg group, 74.7% in the 10-mg group, and 72.2% in the 1-mg group.

One participant in the 25-mg group experienced acute anxiety and was treated with lorazepam.

The incidence of treatment-emergent serious adverse events from day 2 to week 3 was 6.3% (five patients) in the 25-mg group, 8.0% (six patients) in the 10-mg group, and 1.3% (one patient) in the 1-mg group.

Serious AEs included suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury among two patients each in the 25-mg group, while in the 10-mg group, two had suicidal ideation and one had hospitalization for severe depression.

There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of vital signs or clinical laboratory tests.

Of note, two patients in the 25-mg group had a change from baseline in QTcF >60 msec on day 2. For one patient, the increase was within normal range, and the other had a QTcF interval duration >500 msec on day 2, but levels returned to normal by day 9.

Improvements in context

Dr. Goodwin noted that the improvements were swift and impressive when compared with those of the STAR*D trial, which is the largest prospective study of treatment outcomes in patients with MDD.

“In the STAR*D trial, third- and fourth-step treatments showed low response rates of under 15% and high relapse rates,” Dr. Goodwin said. “By comparison, our response rates at 12 weeks were 20%-25%, so almost double that seen for probably equivalent treatment steps in STAR*D, with a single treatment with 25 mg, and no additional antidepressant, so no side effect burden.

“We hope to follow up enough of these patients [in the new study] to get some idea of relapse rates,” Dr. Goodwin added. “These have been low in comparable studies with MDD patients: We will see.”

Commenting on the research, Balwinder Singh, MD, of the department of psychiatry and psychology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said the study represents a valuable addition to needed evidence on psilocybin – with some caveats.

“This study adds to the emerging evidence base of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression, at least in the short term,” he said in an interview. “I think the challenge in the real world would be to have access to 6-8 hours of therapy with psilocybin when patients struggle to find good therapists who could provide even weekly therapy for an hour.”

In addition, Dr. Singh questioned the durability of a single dose of psilocybin in the long term, noting a recent study (N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032994) that evaluated two doses of psilocybin (25 mg) 3 weeks apart, and failed to show any significant difference compared with the serotonergic antidepressant escitalopram at 6 weeks.

He further expressed concern about the emergence of suicidal behaviors in some patients, as well as the prolongation of QTc > 60 msec reported in the two patients.

“This is something to be carefully assessed in future studies, due to the risk of arrhythmias,” Dr. Singh said.

The study was sponsored by COMPASS Pathfinder Limited. Dr. Goodwin is chief medical officer for COMPASS Pathways. Dr. Singh had no disclosures to report.

NEW ORLEANS –

“This is easily the largest study of a psychedelic drug employing modern randomized controlled trial methodology [with] 22 sites and 10 countries, so it’s not your typical phase 2 trial,” the study’s lead author, Guy M. Goodwin, MD, emeritus professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, England, said in an interview.

“Importantly, 94% of the patients in the study were psilocybin naive, which is very important for generalizability,” Dr. Goodwin noted.

Long used as psychedelic ‘magic mushrooms,’ psilocybin has gained increased interest in psychiatry in recent years as a potential treatment for severe depression after showing benefits in patients with life-threatening cancers and others with major depressive disorder (MDD).

To put the therapy to test in a more rigorous, randomized trial, Dr. Goodwin and colleagues conducted the phase 2b study of a proprietary synthetic formulation of psilocybin, COMP360 (COMPASS Pathways), recruiting 233 patients with treatment-resistant depression at 22 centers.

The study was presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

After a 2-week washout period following the discontinuation of antidepressants, the patients were randomized to one of three groups: A single dose of 25 mg (n = 79), 10 mg (n = 75), or a subtherapeutic comparison of 1 mg (n = 79).

The psilocybin was administered in the presence of specially trained therapists who provided psychological support before, during, and after the 6- to 8-hour session.

Patients were then asked to refrain from antidepressant use for at least 3 weeks following the session, and had periodic follow-up for 12 weeks.

For the primary endpoint, those in the 25-mg group, but not the 10-mg dose, showed a significantly greater reduction in depression from baseline versus the 1-mg group on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale at week 3 (MADRS; -6.6; P < .001).

The benefit was observed at day 2 and week 1 following administration, “confirming the rapid-acting character of the effect,” the investigators reported.

Sustained responses, defined as at least a 50% change from baseline in MADRS total score, were further observed up to week 12 among 20.3% in the 25-mg group and among 5.3% in the 10-mg groups versus 10.1% in the 1-mg group.

On the day of psilocybin treatment, the treatment-emergent side effects that were reported were headache, nausea, and dizziness, with event rates of 83.5% in the 25-mg group, 74.7% in the 10-mg group, and 72.2% in the 1-mg group.

One participant in the 25-mg group experienced acute anxiety and was treated with lorazepam.

The incidence of treatment-emergent serious adverse events from day 2 to week 3 was 6.3% (five patients) in the 25-mg group, 8.0% (six patients) in the 10-mg group, and 1.3% (one patient) in the 1-mg group.

Serious AEs included suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury among two patients each in the 25-mg group, while in the 10-mg group, two had suicidal ideation and one had hospitalization for severe depression.

There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of vital signs or clinical laboratory tests.

Of note, two patients in the 25-mg group had a change from baseline in QTcF >60 msec on day 2. For one patient, the increase was within normal range, and the other had a QTcF interval duration >500 msec on day 2, but levels returned to normal by day 9.

Improvements in context

Dr. Goodwin noted that the improvements were swift and impressive when compared with those of the STAR*D trial, which is the largest prospective study of treatment outcomes in patients with MDD.

“In the STAR*D trial, third- and fourth-step treatments showed low response rates of under 15% and high relapse rates,” Dr. Goodwin said. “By comparison, our response rates at 12 weeks were 20%-25%, so almost double that seen for probably equivalent treatment steps in STAR*D, with a single treatment with 25 mg, and no additional antidepressant, so no side effect burden.

“We hope to follow up enough of these patients [in the new study] to get some idea of relapse rates,” Dr. Goodwin added. “These have been low in comparable studies with MDD patients: We will see.”

Commenting on the research, Balwinder Singh, MD, of the department of psychiatry and psychology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said the study represents a valuable addition to needed evidence on psilocybin – with some caveats.

“This study adds to the emerging evidence base of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression, at least in the short term,” he said in an interview. “I think the challenge in the real world would be to have access to 6-8 hours of therapy with psilocybin when patients struggle to find good therapists who could provide even weekly therapy for an hour.”

In addition, Dr. Singh questioned the durability of a single dose of psilocybin in the long term, noting a recent study (N Engl J Med. 2021 Apr 15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032994) that evaluated two doses of psilocybin (25 mg) 3 weeks apart, and failed to show any significant difference compared with the serotonergic antidepressant escitalopram at 6 weeks.

He further expressed concern about the emergence of suicidal behaviors in some patients, as well as the prolongation of QTc > 60 msec reported in the two patients.

“This is something to be carefully assessed in future studies, due to the risk of arrhythmias,” Dr. Singh said.

The study was sponsored by COMPASS Pathfinder Limited. Dr. Goodwin is chief medical officer for COMPASS Pathways. Dr. Singh had no disclosures to report.

AT APA 2022

Hearing, vision loss combo a colossal risk for cognitive decline

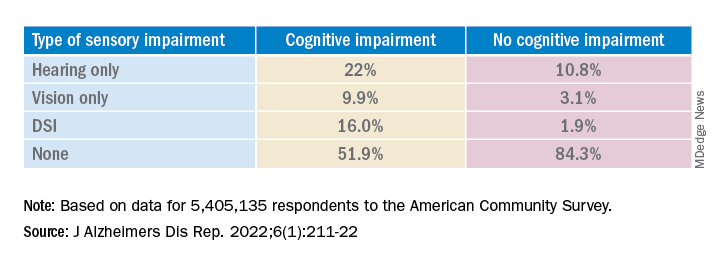

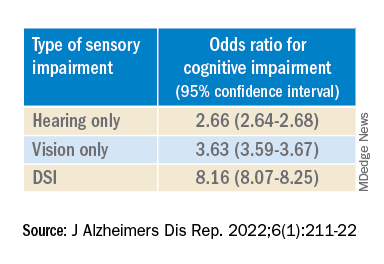

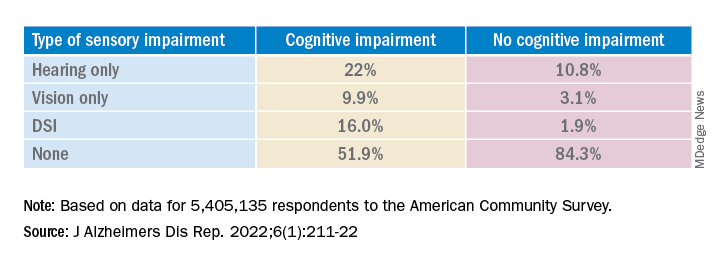

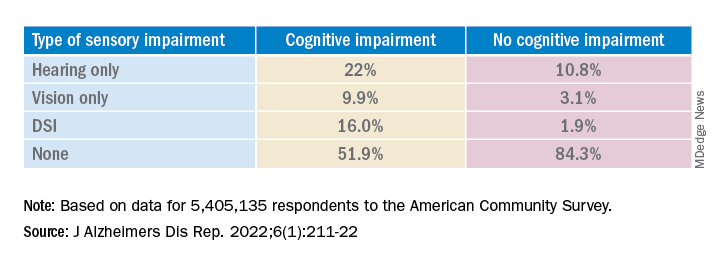

The combination of hearing loss and vision loss is linked to an eightfold increased risk of cognitive impairment, new research shows.

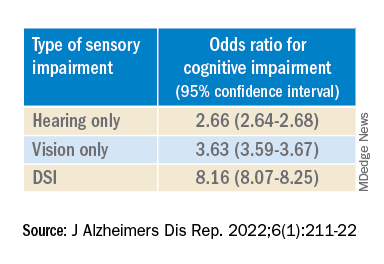

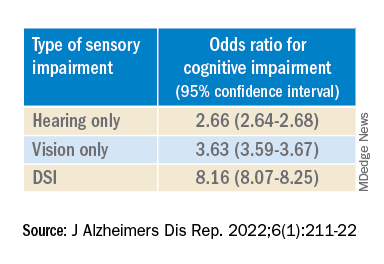

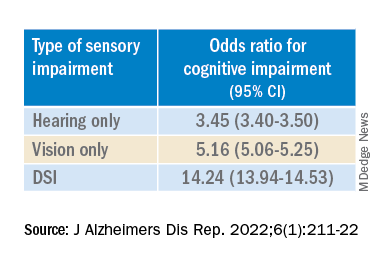

Investigators analyzed data on more than 5 million U.S. seniors. Adjusted results show that participants with hearing impairment alone had more than twice the odds of also having cognitive impairment, while those with vision impairment alone had more than triple the odds of cognitive impairment.

However, those with dual sensory impairment (DSI) had an eightfold higher risk for cognitive impairment.

In addition, half of the participants with DSI also had cognitive impairment. Of those with cognitive impairment, 16% had DSI, compared with only about 2% of their peers without cognitive impairment.

“The findings of the present study may inform interventions that can support older people with concurrent sensory impairment and cognitive impairment,” said lead author Esme Fuller-Thomson, PhD, professor, Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto.

“Special attention, in particular, should be given to those aged 65-74 who have serious hearing and/or vision impairment [because], if the relationship with dementia is found to be causal, such interventions can potentially mitigate the development of cognitive impairment,” said Dr. Fuller-Thomson, who is also director of the Institute for Life Course and Aging and a professor in the department of family and community medicine and faculty of nursing, all at the University of Toronto.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports.

Sensory isolation

Hearing and vision impairment increase with age; it is estimated that one-third of U.S. adults between the ages of 65 and 74 experience hearing loss, and 4% experience vision impairment, the investigators note.

“The link between dual hearing loss and seeing loss and mental health problems such as depression and social isolation have been well researched, but we were very interested in the link between dual sensory loss and cognitive problems,” Dr. Fuller-Thomson said.

Additionally, “there have been several studies in the past decade linking hearing loss to dementia and cognitive decline, but less attention has been paid to cognitive problems among those with DSI, despite this group being particularly isolated,” she said. Existing research into DSI suggests an association with cognitive decline; the current investigators sought to expand on this previous work.

To do so, they used merged data from 10 consecutive waves from 2008 to 2017 of the American Community Survey (ACS), which was conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. The ACS is a nationally representative sample of 3.5 million randomly selected U.S. addresses and includes community-dwelling adults and those residing in institutional settings.

Participants aged 65 or older (n = 5,405,135; 56.4% women) were asked yes/no questions regarding serious cognitive impairment, hearing impairment, and vision impairment. A proxy, such as a family member or nursing home staff member, provided answers for individuals not capable of self-report.

Potential confounding variables included age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, and household income.

Potential mechanisms

Results showed that, among those with cognitive impairment, there was a higher prevalence of hearing impairment, vision impairment, and DSI than among their peers without cognitive impairment; in addition, a lower percentage of these persons had no sensory impairment (P < .001).

The prevalence of DSI climbed with age, from 1.5% for respondents aged 65-74 years to 2.6% for those aged 75-84 and to 10.8% in those 85 years and older.

Individuals with higher levels of poverty also had higher levels of DSI. Among those who had not completed high school, the prevalence of DSI was higher, compared with high school or university graduates (6.3% vs. 3.1% and 1.85, respectively).

After controlling for age, race, education, and income, the researchers found “substantially” higher odds of cognitive impairment in those with vs. those without sensory impairments.

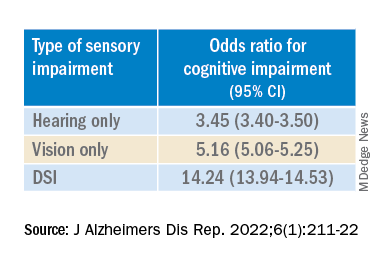

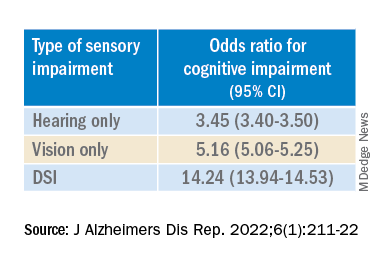

“The magnitude of the odds of cognitive impairment by sensory impairment was greatest for the youngest cohort (age 65-74) and lowest for the oldest cohort (age 85+),” the investigators wrote. Among participants in the youngest cohort, there was a “dose-response relationship” for those with hearing impairment only, visual impairment only, and DSI.

Because the study was observational, it “does not provide sufficient information to determine the reasons behind the observed link between sensory loss and cognitive problems,” Dr. Fuller-Thomson said. However, there are “several potential causal mechanisms [that] warrant future research.”

The “sensory deprivation hypothesis” suggests that DSI could cause cognitive deterioration because of decreased auditory and visual input. The “resource allocation hypothesis” posits that hearing- or vision-impaired older adults “may use more cognitive resources to accommodate for sensory deficits, allocating fewer cognitive resources for higher-order memory processes,” the researchers wrote. Hearing impairment “may also lead to social disengagement among older adults, hastening cognitive decline due to isolation and lack of stimulation,” they added.

Reverse causality is also possible. In the “cognitive load on perception” hypothesis, cognitive decline may lead to declines in hearing and vision because of “decreased resources for sensory processing.”

In addition, the association may be noncausal. “The ‘common cause hypothesis’ theorizes that sensory impairment and cognitive impairment may be due to shared age-related degeneration of the central nervous system ... or frailty,” Dr. Fuller-Thomson said.

Parallel findings

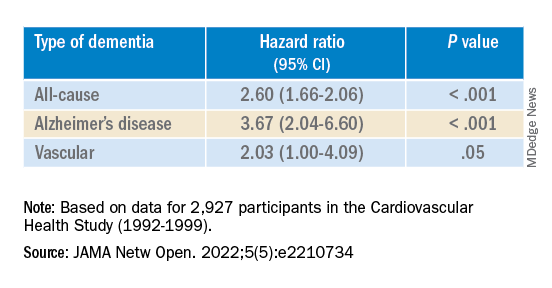

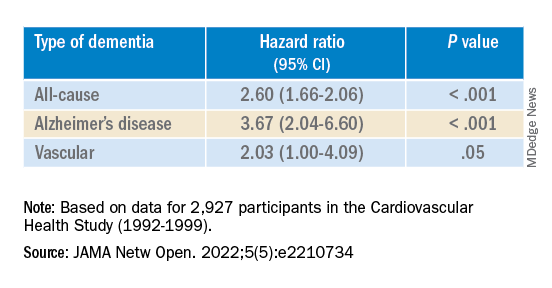

The results are similar to those from a study conducted by Phillip Hwang, PhD, of the department of anatomy and neurobiology, Boston University, and colleagues that was published online in JAMA Network Open.

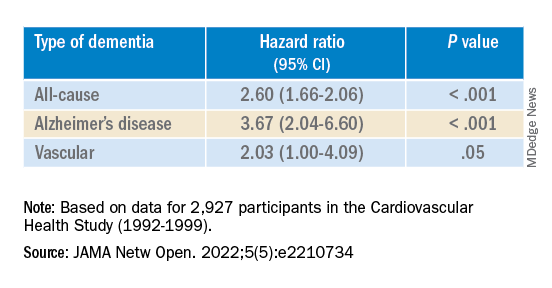

They analyzed data on 8 years of follow-up of 2,927 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study (mean age, 74.6 years; 58.2% women).

Compared with no sensory impairment, DSI was associated with increased risk for all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but not with vascular dementia.

“Future work in health care guidelines could consider incorporating screening of sensory impairment in older adults as part of risk assessment for dementia,” Nicholas Reed, AuD, and Esther Oh, MD, PhD, both of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Accurate testing

Commenting on both studies, Heather Whitson, MD, professor of medicine (geriatrics) and ophthalmology and director at the Duke University Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Durham, N.C., said both “add further strength to the evidence base, which has really converged in the last few years to support that there is a link between sensory health and cognitive health.”

However, “we still don’t know whether hearing/vision loss causes cognitive decline, though there are plausible ways that sensory loss could affect cognitive abilities like memory, language, and executive function,” she said

Dr. Whitson, who was not involved with the research, is also codirector of the Duke/University of North Carolina Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and the Durham VA Medical Center.

“The big question is whether we can improve patients’ cognitive performance by treating or accommodating their sensory impairments,” she said. “If safe and feasible things like hearing aids or cataract surgery improve cognitive health, even a little bit, it would be a huge benefit to society, because sensory loss is very common, and there are many treatment options,” Dr. Whitson added.

Dr. Fuller-Thomson emphasized that practitioners should “consider the full impact of sensory impairment on cognitive testing methods, as both auditory and visual testing methods may fail to take hearing and vision impairment into account.”

Thus, “when performing cognitive tests on older adults with sensory impairments, practitioners should ensure they are communicating audibly and/or using visual speech cues for hearing-impaired individuals, eliminating items from cognitive tests that rely on vision for those who are visually impaired, and using physical cues for individuals with hearing or dual sensory impairment, as this can help increase the accuracy of testing and prevent confounding,” she said.

The study by Fuller-Thomson et al. was funded by a donation from Janis Rotman. Its investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships. The study by Hwang et al. was funded by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hwang reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Reed received grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the study and has served on the advisory board of Neosensory outside the submitted work. Dr. Oh and Dr. Whitson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The combination of hearing loss and vision loss is linked to an eightfold increased risk of cognitive impairment, new research shows.

Investigators analyzed data on more than 5 million U.S. seniors. Adjusted results show that participants with hearing impairment alone had more than twice the odds of also having cognitive impairment, while those with vision impairment alone had more than triple the odds of cognitive impairment.

However, those with dual sensory impairment (DSI) had an eightfold higher risk for cognitive impairment.

In addition, half of the participants with DSI also had cognitive impairment. Of those with cognitive impairment, 16% had DSI, compared with only about 2% of their peers without cognitive impairment.

“The findings of the present study may inform interventions that can support older people with concurrent sensory impairment and cognitive impairment,” said lead author Esme Fuller-Thomson, PhD, professor, Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto.

“Special attention, in particular, should be given to those aged 65-74 who have serious hearing and/or vision impairment [because], if the relationship with dementia is found to be causal, such interventions can potentially mitigate the development of cognitive impairment,” said Dr. Fuller-Thomson, who is also director of the Institute for Life Course and Aging and a professor in the department of family and community medicine and faculty of nursing, all at the University of Toronto.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports.

Sensory isolation

Hearing and vision impairment increase with age; it is estimated that one-third of U.S. adults between the ages of 65 and 74 experience hearing loss, and 4% experience vision impairment, the investigators note.

“The link between dual hearing loss and seeing loss and mental health problems such as depression and social isolation have been well researched, but we were very interested in the link between dual sensory loss and cognitive problems,” Dr. Fuller-Thomson said.

Additionally, “there have been several studies in the past decade linking hearing loss to dementia and cognitive decline, but less attention has been paid to cognitive problems among those with DSI, despite this group being particularly isolated,” she said. Existing research into DSI suggests an association with cognitive decline; the current investigators sought to expand on this previous work.

To do so, they used merged data from 10 consecutive waves from 2008 to 2017 of the American Community Survey (ACS), which was conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. The ACS is a nationally representative sample of 3.5 million randomly selected U.S. addresses and includes community-dwelling adults and those residing in institutional settings.

Participants aged 65 or older (n = 5,405,135; 56.4% women) were asked yes/no questions regarding serious cognitive impairment, hearing impairment, and vision impairment. A proxy, such as a family member or nursing home staff member, provided answers for individuals not capable of self-report.

Potential confounding variables included age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, and household income.

Potential mechanisms

Results showed that, among those with cognitive impairment, there was a higher prevalence of hearing impairment, vision impairment, and DSI than among their peers without cognitive impairment; in addition, a lower percentage of these persons had no sensory impairment (P < .001).

The prevalence of DSI climbed with age, from 1.5% for respondents aged 65-74 years to 2.6% for those aged 75-84 and to 10.8% in those 85 years and older.

Individuals with higher levels of poverty also had higher levels of DSI. Among those who had not completed high school, the prevalence of DSI was higher, compared with high school or university graduates (6.3% vs. 3.1% and 1.85, respectively).

After controlling for age, race, education, and income, the researchers found “substantially” higher odds of cognitive impairment in those with vs. those without sensory impairments.

“The magnitude of the odds of cognitive impairment by sensory impairment was greatest for the youngest cohort (age 65-74) and lowest for the oldest cohort (age 85+),” the investigators wrote. Among participants in the youngest cohort, there was a “dose-response relationship” for those with hearing impairment only, visual impairment only, and DSI.

Because the study was observational, it “does not provide sufficient information to determine the reasons behind the observed link between sensory loss and cognitive problems,” Dr. Fuller-Thomson said. However, there are “several potential causal mechanisms [that] warrant future research.”

The “sensory deprivation hypothesis” suggests that DSI could cause cognitive deterioration because of decreased auditory and visual input. The “resource allocation hypothesis” posits that hearing- or vision-impaired older adults “may use more cognitive resources to accommodate for sensory deficits, allocating fewer cognitive resources for higher-order memory processes,” the researchers wrote. Hearing impairment “may also lead to social disengagement among older adults, hastening cognitive decline due to isolation and lack of stimulation,” they added.

Reverse causality is also possible. In the “cognitive load on perception” hypothesis, cognitive decline may lead to declines in hearing and vision because of “decreased resources for sensory processing.”

In addition, the association may be noncausal. “The ‘common cause hypothesis’ theorizes that sensory impairment and cognitive impairment may be due to shared age-related degeneration of the central nervous system ... or frailty,” Dr. Fuller-Thomson said.

Parallel findings

The results are similar to those from a study conducted by Phillip Hwang, PhD, of the department of anatomy and neurobiology, Boston University, and colleagues that was published online in JAMA Network Open.

They analyzed data on 8 years of follow-up of 2,927 participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study (mean age, 74.6 years; 58.2% women).

Compared with no sensory impairment, DSI was associated with increased risk for all-cause dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but not with vascular dementia.

“Future work in health care guidelines could consider incorporating screening of sensory impairment in older adults as part of risk assessment for dementia,” Nicholas Reed, AuD, and Esther Oh, MD, PhD, both of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Accurate testing

Commenting on both studies, Heather Whitson, MD, professor of medicine (geriatrics) and ophthalmology and director at the Duke University Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Durham, N.C., said both “add further strength to the evidence base, which has really converged in the last few years to support that there is a link between sensory health and cognitive health.”

However, “we still don’t know whether hearing/vision loss causes cognitive decline, though there are plausible ways that sensory loss could affect cognitive abilities like memory, language, and executive function,” she said

Dr. Whitson, who was not involved with the research, is also codirector of the Duke/University of North Carolina Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and the Durham VA Medical Center.

“The big question is whether we can improve patients’ cognitive performance by treating or accommodating their sensory impairments,” she said. “If safe and feasible things like hearing aids or cataract surgery improve cognitive health, even a little bit, it would be a huge benefit to society, because sensory loss is very common, and there are many treatment options,” Dr. Whitson added.

Dr. Fuller-Thomson emphasized that practitioners should “consider the full impact of sensory impairment on cognitive testing methods, as both auditory and visual testing methods may fail to take hearing and vision impairment into account.”

Thus, “when performing cognitive tests on older adults with sensory impairments, practitioners should ensure they are communicating audibly and/or using visual speech cues for hearing-impaired individuals, eliminating items from cognitive tests that rely on vision for those who are visually impaired, and using physical cues for individuals with hearing or dual sensory impairment, as this can help increase the accuracy of testing and prevent confounding,” she said.

The study by Fuller-Thomson et al. was funded by a donation from Janis Rotman. Its investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships. The study by Hwang et al. was funded by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Hwang reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Reed received grants from the National Institute on Aging during the conduct of the study and has served on the advisory board of Neosensory outside the submitted work. Dr. Oh and Dr. Whitson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The combination of hearing loss and vision loss is linked to an eightfold increased risk of cognitive impairment, new research shows.

Investigators analyzed data on more than 5 million U.S. seniors. Adjusted results show that participants with hearing impairment alone had more than twice the odds of also having cognitive impairment, while those with vision impairment alone had more than triple the odds of cognitive impairment.

However, those with dual sensory impairment (DSI) had an eightfold higher risk for cognitive impairment.

In addition, half of the participants with DSI also had cognitive impairment. Of those with cognitive impairment, 16% had DSI, compared with only about 2% of their peers without cognitive impairment.