User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

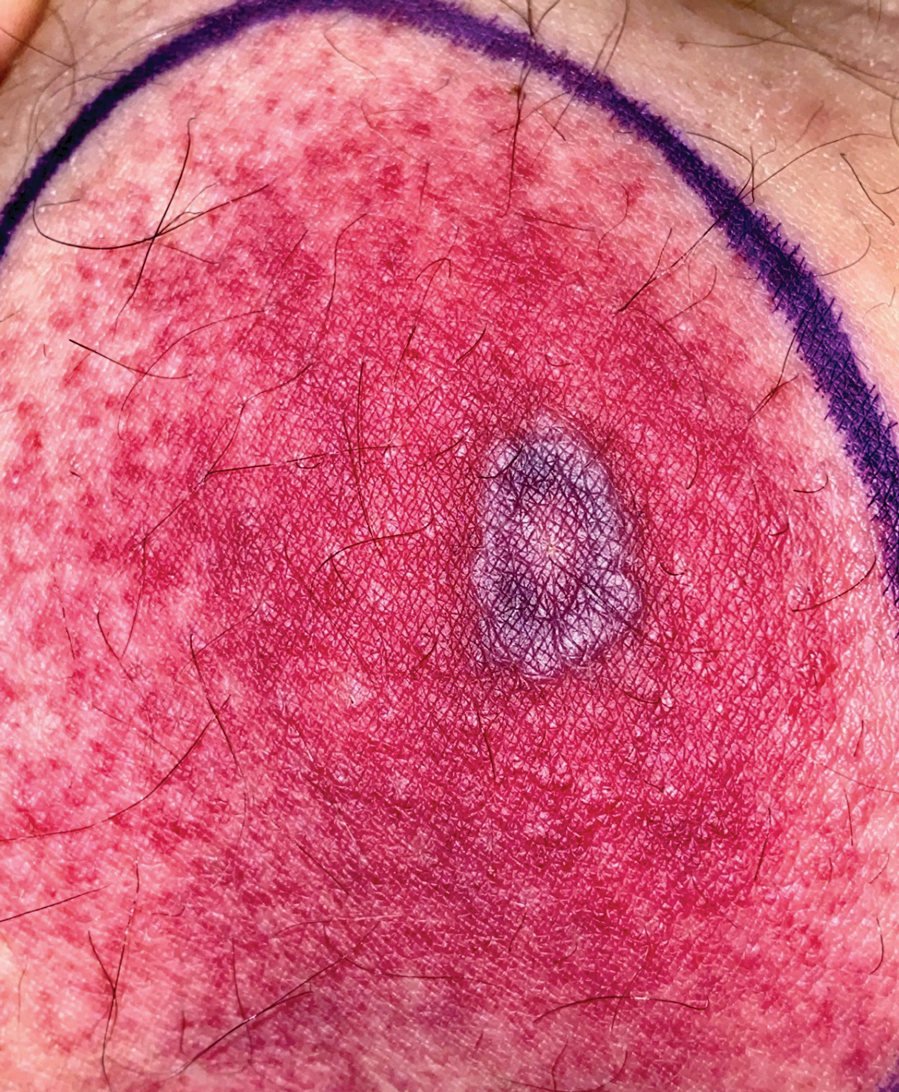

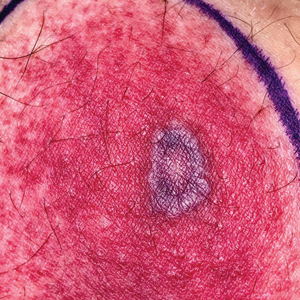

Tender Annular Plaque on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Gangrenosum

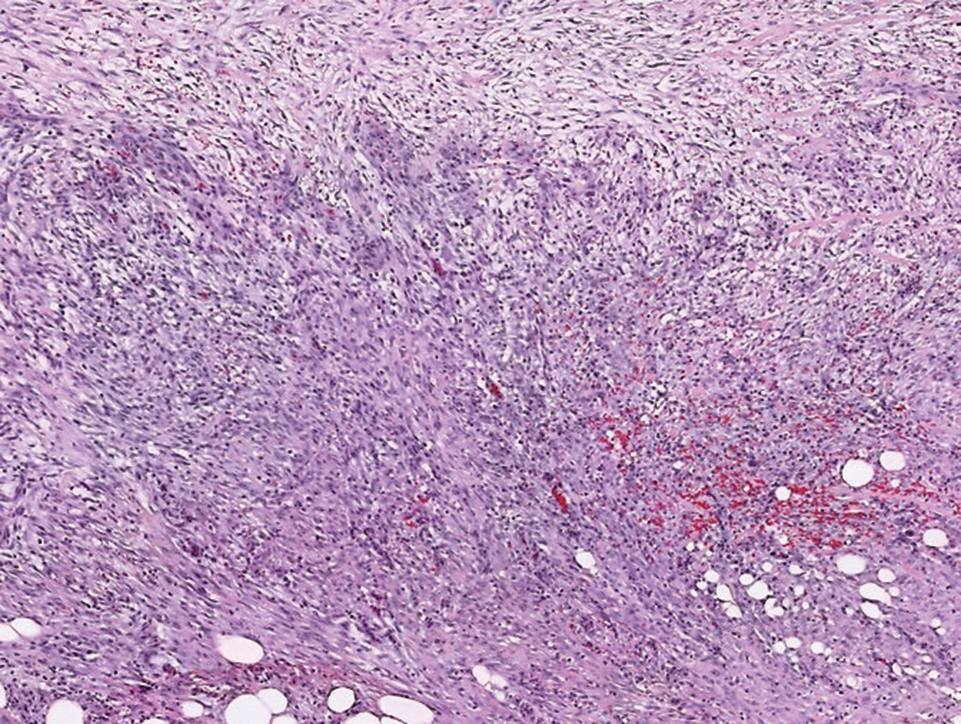

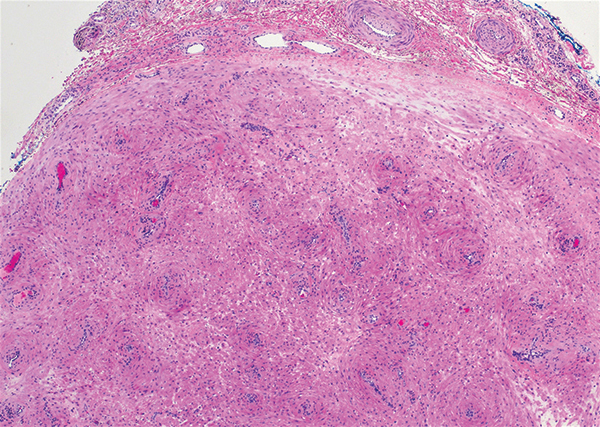

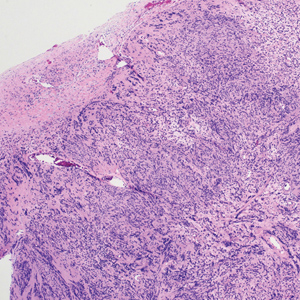

Histopathology revealed basophilic bacterial rods around necrotic vessels with thrombosis and edema (Figure). Blood and tissue cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of P aeruginosa–associated ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) was made. The patient’s symptoms resolved with intravenous cefepime, and he later was transitioned to oral levofloxacin for outpatient treatment.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of bacteremia that most commonly occurs secondary to P aeruginosa in immunocompromised patients, particularly patients with severe neutropenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy.1,2 Ecthyma gangrenosum can occur anywhere on the body, predominantly in moist areas such as the axillae and groin; the arms and legs, such as in our patient, as well as the trunk and face also may be involved.3 Other causes of EG skin lesions include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, fungi such as Candida, and viruses such as herpes simplex virus.2,4-6 Common predisposing conditions associated with EG include neutropenia, leukemia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, extensive burn wounds, and a history of immunosuppressive medications. It also has been known to occur in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent individuals with no difference in clinical manifestation.2

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic, with initial evaluation including blood and wound cultures as well as a complete blood cell count once EG is suspected. An excisional or punch biopsy is performed for confirmation, showing many gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria in cases of pseudomonal EG.7 Histopathology is characterized by bacterial perivascular invasion that then leads to secondary arteriole thrombosis, tissue edema, and separation of the epidermis.7,8 Resultant ischemic necrosis results in the classic macroscopic appearance of an erythematous macule that rapidly progresses into a central necrotic lesion surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous halo after undergoing a hemorrhagic bullous stage.1,9 A Wood lamp can be used to expedite the diagnosis, as Pseudomonas bacteria excretes a pigment (pyoverdine) that fluoresces yellowish green.10

Ecthyma gangrenosum can be classified as a primary skin lesion that may or may not be followed by bacteremia or as a lesion secondary to pseudomonal bacteremia.11 Bacteremia has been reported in half of cases, with hematogenous metastasis of the infection, likely in manifestations with multiple bilateral lesions.2 Our patient’s presentation of a single lesion revealed a positive blood culture result. Lesions also can develop by direct inoculation of the epidermis causing local destruction of the surrounding tissue. The nonbacteremic form of EG has been associated with a lower mortality rate of around 15% compared to patients with bacteremia ranging from 38% to 96%.12 The presence of neutropenia is the most important prognostic factor for mortality at the time of diagnosis.13

Prompt empiric therapy should be initiated after obtaining wound and blood cultures in those with infection until the causative organism and its susceptibility are identified. Pseudomonal infections account for 4% of all cases of hospital-acquired bacteremia and are the third leading cause of gram-negative bloodstream infection.7 Initial broad-spectrum antibiotics include antipseudomonal β-lactams (piperacillin-tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), and carbapenems (imipenem).1,7 Medical therapy alone may be sufficient without requiring extensive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue in some patients. Surgical debridement usually is warranted for lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter.3 Our patient was treated with intravenous cefepime with resolution and was followed with outpatient oral levofloxacin as appropriate. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for relapsing pseudomonal EG infection among patients with AIDS, as the reported recurrence rate is 57%.14

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of EG presenting in immunocompromised patients or individuals with underlying malignancy includes pyoderma gangrenosum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and leukemia cutis. An erythematous rash with central necrosis presenting in a patient with systemic symptoms is pathognomonic for erythema migrans and should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in areas endemic for Lyme disease in the United States, including the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central regions.15 A thorough history, physical examination, basic laboratory studies, and histopathology are critical to differentiate between these entities with similar macroscopic features. Pyoderma gangrenosum histologically manifests as a noninfectious, deep, suppurative folliculitis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 40% of cases.16 Although papulonecrotic tuberculid can present with dermal necrosis resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to antigenic components of mycobacteria, there typically are granulomatous infiltrates present and a lack of observed organisms on histopathology.17 Although leukemia cutis infrequently occurs in patients diagnosed with leukemia, its salient features on pathology are nodular or diffuse infiltrates of leukemic cells in the dermis and subcutis with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, often with prominent nucleoli.18 Lyme disease can present in various ways; however, cutaneous involvement in the primary lesion is histologically characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing plasma cells at the periphery of the expanding annular lesion and eosinophils present at the center.19

- Abdou A, Hassam B. Ecthyma gangrenosum [in French]. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:95. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.95.6244

- Vaiman M, Lazarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum and ecthyma-like lesions: review article. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:633-639. doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2277-6

- Vaiman M, Lasarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum versus ecthyma-like lesions: should we separate these conditions? Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2015;24:69-72. doi:10.15570 /actaapa.2015.18

- Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, et al. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl): S114-S117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.019

- Hawkley T, Chang D, Pollard W, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Citrobacter freundii [published online July 27, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220996

- Santhaseelan RG, Muralidhar V. Non-pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a chronic alcoholic patient [published online August 3, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220983m

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Croxatto A, et al. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212527. doi:10.7573/dic.212527

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegría V, Santos-Briz Á, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000766

- Sarkar S, Patra AK, Mondal M. Ecthyma gangrenosum in the periorbital region in a previously healthy immunocompetent woman without bacteremia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:36-39. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.174326

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Van den Broek PJ, Van der Meer JWM, Kunst MW. The pathogenesis of ecthyma gangrenosum. J Infect. 1979;1:263-267. doi:10.1016 /S0163-4453(79)91329-X

- Downey DM, O’Bryan MC, Burdette SD, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:198-202. doi:10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802CA481

- Martínez-Longoria CA, Rosales-Solis GM, Ocampo-Garza J, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a report of eight cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:698-700. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175580

- Khan MO, Montecalvo MA, Davis I, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:121-123.

- Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998; 352:557-565.

- Su WP, Schroeter AL, Perry HO, et al. Histopathologic and immunopathologic study of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Pathol. 1986;13:323-330. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1986.tb00466.x

- Tirumalae R, Yeliur IK, Antony M, et al. Papulonecrotic tuberculidclinicopathologic and molecular features of 12 Indian patients. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:17-22. doi:10.5826/dpc.0402a03

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis [published online August 15, 2015]. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6m18g35f

- Vasudevan B, Chatterjee M. Lyme borreliosis and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:167-174. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.110822

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Gangrenosum

Histopathology revealed basophilic bacterial rods around necrotic vessels with thrombosis and edema (Figure). Blood and tissue cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of P aeruginosa–associated ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) was made. The patient’s symptoms resolved with intravenous cefepime, and he later was transitioned to oral levofloxacin for outpatient treatment.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of bacteremia that most commonly occurs secondary to P aeruginosa in immunocompromised patients, particularly patients with severe neutropenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy.1,2 Ecthyma gangrenosum can occur anywhere on the body, predominantly in moist areas such as the axillae and groin; the arms and legs, such as in our patient, as well as the trunk and face also may be involved.3 Other causes of EG skin lesions include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, fungi such as Candida, and viruses such as herpes simplex virus.2,4-6 Common predisposing conditions associated with EG include neutropenia, leukemia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, extensive burn wounds, and a history of immunosuppressive medications. It also has been known to occur in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent individuals with no difference in clinical manifestation.2

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic, with initial evaluation including blood and wound cultures as well as a complete blood cell count once EG is suspected. An excisional or punch biopsy is performed for confirmation, showing many gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria in cases of pseudomonal EG.7 Histopathology is characterized by bacterial perivascular invasion that then leads to secondary arteriole thrombosis, tissue edema, and separation of the epidermis.7,8 Resultant ischemic necrosis results in the classic macroscopic appearance of an erythematous macule that rapidly progresses into a central necrotic lesion surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous halo after undergoing a hemorrhagic bullous stage.1,9 A Wood lamp can be used to expedite the diagnosis, as Pseudomonas bacteria excretes a pigment (pyoverdine) that fluoresces yellowish green.10

Ecthyma gangrenosum can be classified as a primary skin lesion that may or may not be followed by bacteremia or as a lesion secondary to pseudomonal bacteremia.11 Bacteremia has been reported in half of cases, with hematogenous metastasis of the infection, likely in manifestations with multiple bilateral lesions.2 Our patient’s presentation of a single lesion revealed a positive blood culture result. Lesions also can develop by direct inoculation of the epidermis causing local destruction of the surrounding tissue. The nonbacteremic form of EG has been associated with a lower mortality rate of around 15% compared to patients with bacteremia ranging from 38% to 96%.12 The presence of neutropenia is the most important prognostic factor for mortality at the time of diagnosis.13

Prompt empiric therapy should be initiated after obtaining wound and blood cultures in those with infection until the causative organism and its susceptibility are identified. Pseudomonal infections account for 4% of all cases of hospital-acquired bacteremia and are the third leading cause of gram-negative bloodstream infection.7 Initial broad-spectrum antibiotics include antipseudomonal β-lactams (piperacillin-tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), and carbapenems (imipenem).1,7 Medical therapy alone may be sufficient without requiring extensive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue in some patients. Surgical debridement usually is warranted for lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter.3 Our patient was treated with intravenous cefepime with resolution and was followed with outpatient oral levofloxacin as appropriate. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for relapsing pseudomonal EG infection among patients with AIDS, as the reported recurrence rate is 57%.14

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of EG presenting in immunocompromised patients or individuals with underlying malignancy includes pyoderma gangrenosum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and leukemia cutis. An erythematous rash with central necrosis presenting in a patient with systemic symptoms is pathognomonic for erythema migrans and should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in areas endemic for Lyme disease in the United States, including the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central regions.15 A thorough history, physical examination, basic laboratory studies, and histopathology are critical to differentiate between these entities with similar macroscopic features. Pyoderma gangrenosum histologically manifests as a noninfectious, deep, suppurative folliculitis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 40% of cases.16 Although papulonecrotic tuberculid can present with dermal necrosis resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to antigenic components of mycobacteria, there typically are granulomatous infiltrates present and a lack of observed organisms on histopathology.17 Although leukemia cutis infrequently occurs in patients diagnosed with leukemia, its salient features on pathology are nodular or diffuse infiltrates of leukemic cells in the dermis and subcutis with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, often with prominent nucleoli.18 Lyme disease can present in various ways; however, cutaneous involvement in the primary lesion is histologically characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing plasma cells at the periphery of the expanding annular lesion and eosinophils present at the center.19

The Diagnosis: Ecthyma Gangrenosum

Histopathology revealed basophilic bacterial rods around necrotic vessels with thrombosis and edema (Figure). Blood and tissue cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Based on the histopathology and clinical presentation, a diagnosis of P aeruginosa–associated ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) was made. The patient’s symptoms resolved with intravenous cefepime, and he later was transitioned to oral levofloxacin for outpatient treatment.

Ecthyma gangrenosum is an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of bacteremia that most commonly occurs secondary to P aeruginosa in immunocompromised patients, particularly patients with severe neutropenia in the setting of recent chemotherapy.1,2 Ecthyma gangrenosum can occur anywhere on the body, predominantly in moist areas such as the axillae and groin; the arms and legs, such as in our patient, as well as the trunk and face also may be involved.3 Other causes of EG skin lesions include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, fungi such as Candida, and viruses such as herpes simplex virus.2,4-6 Common predisposing conditions associated with EG include neutropenia, leukemia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, extensive burn wounds, and a history of immunosuppressive medications. It also has been known to occur in otherwise healthy, immunocompetent individuals with no difference in clinical manifestation.2

The diagnosis is clinicopathologic, with initial evaluation including blood and wound cultures as well as a complete blood cell count once EG is suspected. An excisional or punch biopsy is performed for confirmation, showing many gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria in cases of pseudomonal EG.7 Histopathology is characterized by bacterial perivascular invasion that then leads to secondary arteriole thrombosis, tissue edema, and separation of the epidermis.7,8 Resultant ischemic necrosis results in the classic macroscopic appearance of an erythematous macule that rapidly progresses into a central necrotic lesion surrounded by an erythematous or violaceous halo after undergoing a hemorrhagic bullous stage.1,9 A Wood lamp can be used to expedite the diagnosis, as Pseudomonas bacteria excretes a pigment (pyoverdine) that fluoresces yellowish green.10

Ecthyma gangrenosum can be classified as a primary skin lesion that may or may not be followed by bacteremia or as a lesion secondary to pseudomonal bacteremia.11 Bacteremia has been reported in half of cases, with hematogenous metastasis of the infection, likely in manifestations with multiple bilateral lesions.2 Our patient’s presentation of a single lesion revealed a positive blood culture result. Lesions also can develop by direct inoculation of the epidermis causing local destruction of the surrounding tissue. The nonbacteremic form of EG has been associated with a lower mortality rate of around 15% compared to patients with bacteremia ranging from 38% to 96%.12 The presence of neutropenia is the most important prognostic factor for mortality at the time of diagnosis.13

Prompt empiric therapy should be initiated after obtaining wound and blood cultures in those with infection until the causative organism and its susceptibility are identified. Pseudomonal infections account for 4% of all cases of hospital-acquired bacteremia and are the third leading cause of gram-negative bloodstream infection.7 Initial broad-spectrum antibiotics include antipseudomonal β-lactams (piperacillin-tazobactam), cephalosporins (cefepime), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin), and carbapenems (imipenem).1,7 Medical therapy alone may be sufficient without requiring extensive surgical debridement to remove necrotic tissue in some patients. Surgical debridement usually is warranted for lesions larger than 10 cm in diameter.3 Our patient was treated with intravenous cefepime with resolution and was followed with outpatient oral levofloxacin as appropriate. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for relapsing pseudomonal EG infection among patients with AIDS, as the reported recurrence rate is 57%.14

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of EG presenting in immunocompromised patients or individuals with underlying malignancy includes pyoderma gangrenosum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and leukemia cutis. An erythematous rash with central necrosis presenting in a patient with systemic symptoms is pathognomonic for erythema migrans and should be considered as a diagnostic possibility in areas endemic for Lyme disease in the United States, including the northeastern, mid-Atlantic, and north-central regions.15 A thorough history, physical examination, basic laboratory studies, and histopathology are critical to differentiate between these entities with similar macroscopic features. Pyoderma gangrenosum histologically manifests as a noninfectious, deep, suppurative folliculitis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis in 40% of cases.16 Although papulonecrotic tuberculid can present with dermal necrosis resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to antigenic components of mycobacteria, there typically are granulomatous infiltrates present and a lack of observed organisms on histopathology.17 Although leukemia cutis infrequently occurs in patients diagnosed with leukemia, its salient features on pathology are nodular or diffuse infiltrates of leukemic cells in the dermis and subcutis with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, often with prominent nucleoli.18 Lyme disease can present in various ways; however, cutaneous involvement in the primary lesion is histologically characterized by a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing plasma cells at the periphery of the expanding annular lesion and eosinophils present at the center.19

- Abdou A, Hassam B. Ecthyma gangrenosum [in French]. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:95. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.95.6244

- Vaiman M, Lazarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum and ecthyma-like lesions: review article. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:633-639. doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2277-6

- Vaiman M, Lasarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum versus ecthyma-like lesions: should we separate these conditions? Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2015;24:69-72. doi:10.15570 /actaapa.2015.18

- Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, et al. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl): S114-S117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.019

- Hawkley T, Chang D, Pollard W, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Citrobacter freundii [published online July 27, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220996

- Santhaseelan RG, Muralidhar V. Non-pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a chronic alcoholic patient [published online August 3, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220983m

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Croxatto A, et al. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212527. doi:10.7573/dic.212527

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegría V, Santos-Briz Á, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000766

- Sarkar S, Patra AK, Mondal M. Ecthyma gangrenosum in the periorbital region in a previously healthy immunocompetent woman without bacteremia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:36-39. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.174326

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Van den Broek PJ, Van der Meer JWM, Kunst MW. The pathogenesis of ecthyma gangrenosum. J Infect. 1979;1:263-267. doi:10.1016 /S0163-4453(79)91329-X

- Downey DM, O’Bryan MC, Burdette SD, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:198-202. doi:10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802CA481

- Martínez-Longoria CA, Rosales-Solis GM, Ocampo-Garza J, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a report of eight cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:698-700. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175580

- Khan MO, Montecalvo MA, Davis I, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:121-123.

- Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998; 352:557-565.

- Su WP, Schroeter AL, Perry HO, et al. Histopathologic and immunopathologic study of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Pathol. 1986;13:323-330. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1986.tb00466.x

- Tirumalae R, Yeliur IK, Antony M, et al. Papulonecrotic tuberculidclinicopathologic and molecular features of 12 Indian patients. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:17-22. doi:10.5826/dpc.0402a03

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis [published online August 15, 2015]. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6m18g35f

- Vasudevan B, Chatterjee M. Lyme borreliosis and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:167-174. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.110822

- Abdou A, Hassam B. Ecthyma gangrenosum [in French]. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:95. doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.30.95.6244

- Vaiman M, Lazarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum and ecthyma-like lesions: review article. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:633-639. doi:10.1007/s10096-014-2277-6

- Vaiman M, Lasarovitch T, Heller L, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum versus ecthyma-like lesions: should we separate these conditions? Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2015;24:69-72. doi:10.15570 /actaapa.2015.18

- Reich HL, Williams Fadeyi D, Naik NS, et al. Nonpseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl): S114-S117. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.019

- Hawkley T, Chang D, Pollard W, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum caused by Citrobacter freundii [published online July 27, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220996

- Santhaseelan RG, Muralidhar V. Non-pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a chronic alcoholic patient [published online August 3, 2017]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-220983m

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Croxatto A, et al. How to manage Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212527. doi:10.7573/dic.212527

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegría V, Santos-Briz Á, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000766

- Sarkar S, Patra AK, Mondal M. Ecthyma gangrenosum in the periorbital region in a previously healthy immunocompetent woman without bacteremia. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:36-39. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.174326

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Van den Broek PJ, Van der Meer JWM, Kunst MW. The pathogenesis of ecthyma gangrenosum. J Infect. 1979;1:263-267. doi:10.1016 /S0163-4453(79)91329-X

- Downey DM, O’Bryan MC, Burdette SD, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in a patient with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:198-202. doi:10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802CA481

- Martínez-Longoria CA, Rosales-Solis GM, Ocampo-Garza J, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum: a report of eight cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:698-700. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175580

- Khan MO, Montecalvo MA, Davis I, et al. Ecthyma gangrenosum in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:121-123.

- Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 1998; 352:557-565.

- Su WP, Schroeter AL, Perry HO, et al. Histopathologic and immunopathologic study of pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Pathol. 1986;13:323-330. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.1986.tb00466.x

- Tirumalae R, Yeliur IK, Antony M, et al. Papulonecrotic tuberculidclinicopathologic and molecular features of 12 Indian patients. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:17-22. doi:10.5826/dpc.0402a03

- Obiozor C, Ganguly S, Fraga GR. Leukemia cutis with lymphoglandular bodies: a clue to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cutis [published online August 15, 2015]. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21:13030/qt6m18g35f

- Vasudevan B, Chatterjee M. Lyme borreliosis and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:167-174. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.110822

A 58-year-old man who was receiving gilteritinib therapy for relapsed acute myeloid leukemia presented to the emergency department with a painful, rapidly enlarging lesion on the right medial thigh of 2 days’ duration that was accompanied by fever (temperature, 39.2 °C) and body aches. Physical examination revealed a tender annular plaque with a dark violaceous halo overlying a larger area of erythema and induration. Laboratory evaluation revealed a white blood cell count of 600/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL) and an absolute neutrophil count of 200/μL (reference range, 1800–7000/μL). A biopsy was performed.

Soft Nodule on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Schwannoma

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a benign encapsulated neoplasm of the peripheral nerve sheath that presents as a subcutaneous nodule.1 It also may present in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and viscera (eg, gastrointestinal tract, bone, upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes). It may occur as multiple lesions when associated with certain syndromes. It usually is an asymptomatic indolent tumor with neurologic symptoms, such as pain and tenderness, in the lesions that are deeper, larger, or closer in proximity to nearby structures.2,3

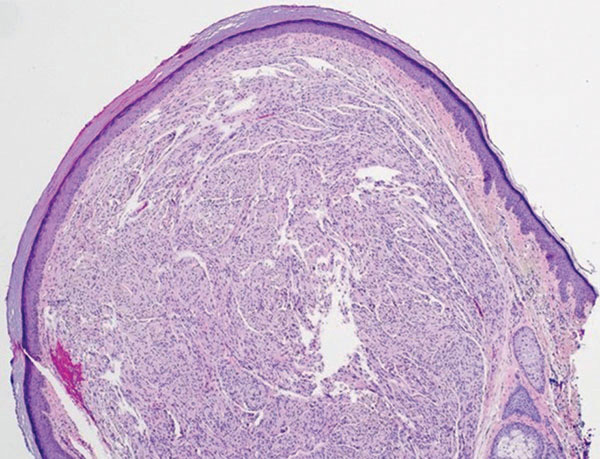

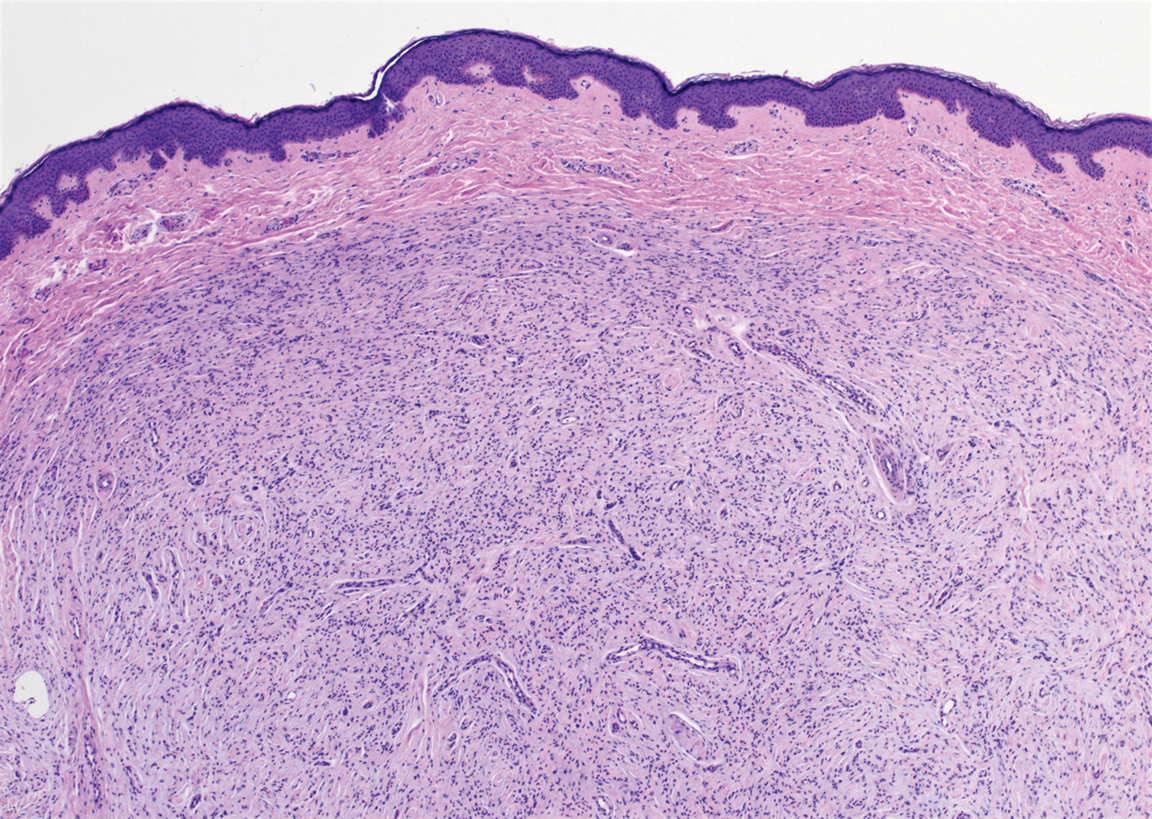

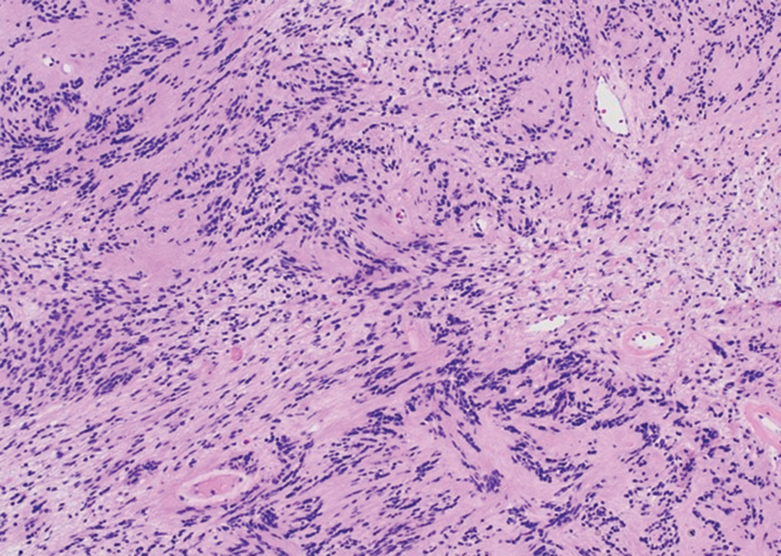

Histologically, a schwannoma is encapsulated by the perineurium of the nerve bundle from which it originates (quiz image [top]). The tumor consists of hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas. Antoni type A areas consist of tightly packed, spindleshaped cells with elongated wavy nuclei and indistinct cytoplasmic borders. These nuclei tend to align into parallel rows with intervening anuclear zones forming Verocay bodies (quiz image [bottom]).4 Verocay bodies are not seen in all schwannomas, and similar formations may be seen in other tumors as well. Solitary circumscribed neuromas also have Verocay bodies, whereas dermatofibromas and leiomyomas have Verocay-like bodies. Antoni type B areas have scattered spindled or ovoid cells in an edematous or myxoid matrix interspersed with inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and histiocytes. Vessels with thick hyalinized walls are a helpful feature in diagnosis.2 Schwann cells of a schwannoma stain diffusely positive with S-100 protein. The capsule stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen due to the presence of perineurial cells.2

The morphologic variants of this entity include conventional (common, solitary), cellular, plexiform, ancient, melanotic, epithelioid, pseudoglandular, neuroblastomalike, and microcystic/reticular schwannomas. There are additional variants that are associated with genetic syndromes, such as multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas linked with neurofibromatosis type 2, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting in Carney complex, schwannomatosis, and segmental schwannomatosis (a distinct form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas localized to one limb). Either presentation may have alteration or deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene, NF2, on chromosome 22.2,5

Nodular fasciitis is a benign tumor of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that usually arises in the subcutaneous tissues. It most commonly occurs in the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck. It presents as a single, often painful, rapidly growing, subcutaneous nodule. Histologically, lesions mostly are well circumscribed yet unencapsulated, in contrast to schwannomas. They may be hypocellular or hypercellular and are composed of uniform spindle cells with a feathery or fascicular (tissue culture–like) appearance in a loose, myxoid to collagenous stroma. There may be foci of hemorrhage and conspicuous mitoses but not atypical figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemically, the cells stain positively for smooth muscle actin and negatively for S-100 protein, which sets it apart from a schwannoma. Most cases contain fusion genes, with myosin heavy chain 9 ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, being the most common fusion product.6

Solitary circumscribed neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma) is a benign, usually solitary dermal lesion. It most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly adults as a small (<1 cm), firm, flesh-colored to pink papule on the face (ie, cheeks, nose, nasolabial folds) and less commonly in the oral and acral regions and on the eyelids and penis. The lesion usually is unilobular; however, other growth patterns such as plexiform, multilobular, and fungating variants have been identified. Histologically, it is a well-circumscribed nodule with a thin capsule of perineurium that is composed of interlacing bundles of Schwann cells with a characteristic clefting artifact (Figure 2). Cells have wavy dark nuclei with scant cytoplasm that occasionally form palisades or Verocay bodies causing these lesions to be confused with schwannomas. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positively with S-100 protein, and the perineurium stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, and Glut-1. Neurofilament protein stains axons throughout neuromas, whereas in schwannoma, the expression often is limited to entrapped axons at the periphery of the tumor.7

Angioleiomyoma is an uncommon, benign, smooth muscle neoplasm of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that originates from vascular smooth muscle. It most commonly presents in adult females aged 30 to 60 years, with a predilection for the lower limbs. These tumors typically are solitary, slow growing, and less than 2 cm in diameter and may be painful upon compression. Similar to schwannoma, angioleiomyoma is an encapsulated lesion composed of interlacing, uniform, smooth muscle bundles distributed around vessels (Figure 3). Smooth muscle cells have oval- or cigar-shaped nuclei with a small perinuclear vacuole of glycogen. Immunohistochemically, there is strong diffuse staining for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon. Recurrence after excision is rare.2,8

Neurofibroma is a common, mostly sporadic, benign tumor of nerve sheath origin. The solitary type may be localized (well circumscribed, unencapsulated) or diffuse. The presence of multiple, deep, and plexiform lesions is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) that is caused by germline mutations in the NF1 gene. Histologically, the tumor is composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and nerve axons within an extracellular myxoid to collagenous matrix (Figure 4). The diffuse type is an ill-defined proliferation that entraps adnexal structures. The plexiform type is defined by multinodular serpentine fascicles. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10). Epithelial membrane antigen stains admixed perineurial cells. Neurofilament protein highlights intratumoral axons, which generally are not found throughout schwannomas. Transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occurs in up to 10% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, usually in plexiform neurofibromas, and is characterized by increased cellularity, atypia, mitotic activity, and necrosis.9

- Ritter SE, Elston DM. Cutaneous schwannoma of the foot. Cutis. 2001;67:127-129.

- Calonje E, Damaskou V, Lazar AJ. Connective tissue tumors. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier Saunders; 2020:1698-1894.

- Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382-387.

- Lespi PJ, Smit R. Verocay body—prominent cutaneous leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:110-111.

- Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925-934.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Leblebici C, Savli TC, Yeni B, et al. Palisaded encapsulated (solitary circumscribed) neuroma: a review of 30 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:506-514.

- Yeung CM, Moore L, Lans J, et al. Angioleiomyoma of the hand: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020; 8:373-377.

- Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:157-166.

The Diagnosis: Schwannoma

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a benign encapsulated neoplasm of the peripheral nerve sheath that presents as a subcutaneous nodule.1 It also may present in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and viscera (eg, gastrointestinal tract, bone, upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes). It may occur as multiple lesions when associated with certain syndromes. It usually is an asymptomatic indolent tumor with neurologic symptoms, such as pain and tenderness, in the lesions that are deeper, larger, or closer in proximity to nearby structures.2,3

Histologically, a schwannoma is encapsulated by the perineurium of the nerve bundle from which it originates (quiz image [top]). The tumor consists of hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas. Antoni type A areas consist of tightly packed, spindleshaped cells with elongated wavy nuclei and indistinct cytoplasmic borders. These nuclei tend to align into parallel rows with intervening anuclear zones forming Verocay bodies (quiz image [bottom]).4 Verocay bodies are not seen in all schwannomas, and similar formations may be seen in other tumors as well. Solitary circumscribed neuromas also have Verocay bodies, whereas dermatofibromas and leiomyomas have Verocay-like bodies. Antoni type B areas have scattered spindled or ovoid cells in an edematous or myxoid matrix interspersed with inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and histiocytes. Vessels with thick hyalinized walls are a helpful feature in diagnosis.2 Schwann cells of a schwannoma stain diffusely positive with S-100 protein. The capsule stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen due to the presence of perineurial cells.2

The morphologic variants of this entity include conventional (common, solitary), cellular, plexiform, ancient, melanotic, epithelioid, pseudoglandular, neuroblastomalike, and microcystic/reticular schwannomas. There are additional variants that are associated with genetic syndromes, such as multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas linked with neurofibromatosis type 2, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting in Carney complex, schwannomatosis, and segmental schwannomatosis (a distinct form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas localized to one limb). Either presentation may have alteration or deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene, NF2, on chromosome 22.2,5

Nodular fasciitis is a benign tumor of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that usually arises in the subcutaneous tissues. It most commonly occurs in the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck. It presents as a single, often painful, rapidly growing, subcutaneous nodule. Histologically, lesions mostly are well circumscribed yet unencapsulated, in contrast to schwannomas. They may be hypocellular or hypercellular and are composed of uniform spindle cells with a feathery or fascicular (tissue culture–like) appearance in a loose, myxoid to collagenous stroma. There may be foci of hemorrhage and conspicuous mitoses but not atypical figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemically, the cells stain positively for smooth muscle actin and negatively for S-100 protein, which sets it apart from a schwannoma. Most cases contain fusion genes, with myosin heavy chain 9 ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, being the most common fusion product.6

Solitary circumscribed neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma) is a benign, usually solitary dermal lesion. It most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly adults as a small (<1 cm), firm, flesh-colored to pink papule on the face (ie, cheeks, nose, nasolabial folds) and less commonly in the oral and acral regions and on the eyelids and penis. The lesion usually is unilobular; however, other growth patterns such as plexiform, multilobular, and fungating variants have been identified. Histologically, it is a well-circumscribed nodule with a thin capsule of perineurium that is composed of interlacing bundles of Schwann cells with a characteristic clefting artifact (Figure 2). Cells have wavy dark nuclei with scant cytoplasm that occasionally form palisades or Verocay bodies causing these lesions to be confused with schwannomas. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positively with S-100 protein, and the perineurium stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, and Glut-1. Neurofilament protein stains axons throughout neuromas, whereas in schwannoma, the expression often is limited to entrapped axons at the periphery of the tumor.7

Angioleiomyoma is an uncommon, benign, smooth muscle neoplasm of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that originates from vascular smooth muscle. It most commonly presents in adult females aged 30 to 60 years, with a predilection for the lower limbs. These tumors typically are solitary, slow growing, and less than 2 cm in diameter and may be painful upon compression. Similar to schwannoma, angioleiomyoma is an encapsulated lesion composed of interlacing, uniform, smooth muscle bundles distributed around vessels (Figure 3). Smooth muscle cells have oval- or cigar-shaped nuclei with a small perinuclear vacuole of glycogen. Immunohistochemically, there is strong diffuse staining for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon. Recurrence after excision is rare.2,8

Neurofibroma is a common, mostly sporadic, benign tumor of nerve sheath origin. The solitary type may be localized (well circumscribed, unencapsulated) or diffuse. The presence of multiple, deep, and plexiform lesions is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) that is caused by germline mutations in the NF1 gene. Histologically, the tumor is composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and nerve axons within an extracellular myxoid to collagenous matrix (Figure 4). The diffuse type is an ill-defined proliferation that entraps adnexal structures. The plexiform type is defined by multinodular serpentine fascicles. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10). Epithelial membrane antigen stains admixed perineurial cells. Neurofilament protein highlights intratumoral axons, which generally are not found throughout schwannomas. Transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occurs in up to 10% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, usually in plexiform neurofibromas, and is characterized by increased cellularity, atypia, mitotic activity, and necrosis.9

The Diagnosis: Schwannoma

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a benign encapsulated neoplasm of the peripheral nerve sheath that presents as a subcutaneous nodule.1 It also may present in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and viscera (eg, gastrointestinal tract, bone, upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes). It may occur as multiple lesions when associated with certain syndromes. It usually is an asymptomatic indolent tumor with neurologic symptoms, such as pain and tenderness, in the lesions that are deeper, larger, or closer in proximity to nearby structures.2,3

Histologically, a schwannoma is encapsulated by the perineurium of the nerve bundle from which it originates (quiz image [top]). The tumor consists of hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas. Antoni type A areas consist of tightly packed, spindleshaped cells with elongated wavy nuclei and indistinct cytoplasmic borders. These nuclei tend to align into parallel rows with intervening anuclear zones forming Verocay bodies (quiz image [bottom]).4 Verocay bodies are not seen in all schwannomas, and similar formations may be seen in other tumors as well. Solitary circumscribed neuromas also have Verocay bodies, whereas dermatofibromas and leiomyomas have Verocay-like bodies. Antoni type B areas have scattered spindled or ovoid cells in an edematous or myxoid matrix interspersed with inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and histiocytes. Vessels with thick hyalinized walls are a helpful feature in diagnosis.2 Schwann cells of a schwannoma stain diffusely positive with S-100 protein. The capsule stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen due to the presence of perineurial cells.2

The morphologic variants of this entity include conventional (common, solitary), cellular, plexiform, ancient, melanotic, epithelioid, pseudoglandular, neuroblastomalike, and microcystic/reticular schwannomas. There are additional variants that are associated with genetic syndromes, such as multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas linked with neurofibromatosis type 2, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting in Carney complex, schwannomatosis, and segmental schwannomatosis (a distinct form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas localized to one limb). Either presentation may have alteration or deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene, NF2, on chromosome 22.2,5

Nodular fasciitis is a benign tumor of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that usually arises in the subcutaneous tissues. It most commonly occurs in the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck. It presents as a single, often painful, rapidly growing, subcutaneous nodule. Histologically, lesions mostly are well circumscribed yet unencapsulated, in contrast to schwannomas. They may be hypocellular or hypercellular and are composed of uniform spindle cells with a feathery or fascicular (tissue culture–like) appearance in a loose, myxoid to collagenous stroma. There may be foci of hemorrhage and conspicuous mitoses but not atypical figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemically, the cells stain positively for smooth muscle actin and negatively for S-100 protein, which sets it apart from a schwannoma. Most cases contain fusion genes, with myosin heavy chain 9 ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, being the most common fusion product.6

Solitary circumscribed neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma) is a benign, usually solitary dermal lesion. It most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly adults as a small (<1 cm), firm, flesh-colored to pink papule on the face (ie, cheeks, nose, nasolabial folds) and less commonly in the oral and acral regions and on the eyelids and penis. The lesion usually is unilobular; however, other growth patterns such as plexiform, multilobular, and fungating variants have been identified. Histologically, it is a well-circumscribed nodule with a thin capsule of perineurium that is composed of interlacing bundles of Schwann cells with a characteristic clefting artifact (Figure 2). Cells have wavy dark nuclei with scant cytoplasm that occasionally form palisades or Verocay bodies causing these lesions to be confused with schwannomas. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positively with S-100 protein, and the perineurium stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, and Glut-1. Neurofilament protein stains axons throughout neuromas, whereas in schwannoma, the expression often is limited to entrapped axons at the periphery of the tumor.7

Angioleiomyoma is an uncommon, benign, smooth muscle neoplasm of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that originates from vascular smooth muscle. It most commonly presents in adult females aged 30 to 60 years, with a predilection for the lower limbs. These tumors typically are solitary, slow growing, and less than 2 cm in diameter and may be painful upon compression. Similar to schwannoma, angioleiomyoma is an encapsulated lesion composed of interlacing, uniform, smooth muscle bundles distributed around vessels (Figure 3). Smooth muscle cells have oval- or cigar-shaped nuclei with a small perinuclear vacuole of glycogen. Immunohistochemically, there is strong diffuse staining for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon. Recurrence after excision is rare.2,8

Neurofibroma is a common, mostly sporadic, benign tumor of nerve sheath origin. The solitary type may be localized (well circumscribed, unencapsulated) or diffuse. The presence of multiple, deep, and plexiform lesions is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) that is caused by germline mutations in the NF1 gene. Histologically, the tumor is composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and nerve axons within an extracellular myxoid to collagenous matrix (Figure 4). The diffuse type is an ill-defined proliferation that entraps adnexal structures. The plexiform type is defined by multinodular serpentine fascicles. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10). Epithelial membrane antigen stains admixed perineurial cells. Neurofilament protein highlights intratumoral axons, which generally are not found throughout schwannomas. Transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occurs in up to 10% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, usually in plexiform neurofibromas, and is characterized by increased cellularity, atypia, mitotic activity, and necrosis.9

- Ritter SE, Elston DM. Cutaneous schwannoma of the foot. Cutis. 2001;67:127-129.

- Calonje E, Damaskou V, Lazar AJ. Connective tissue tumors. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier Saunders; 2020:1698-1894.

- Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382-387.

- Lespi PJ, Smit R. Verocay body—prominent cutaneous leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:110-111.

- Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925-934.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Leblebici C, Savli TC, Yeni B, et al. Palisaded encapsulated (solitary circumscribed) neuroma: a review of 30 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:506-514.

- Yeung CM, Moore L, Lans J, et al. Angioleiomyoma of the hand: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020; 8:373-377.

- Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:157-166.

- Ritter SE, Elston DM. Cutaneous schwannoma of the foot. Cutis. 2001;67:127-129.

- Calonje E, Damaskou V, Lazar AJ. Connective tissue tumors. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier Saunders; 2020:1698-1894.

- Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382-387.

- Lespi PJ, Smit R. Verocay body—prominent cutaneous leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:110-111.

- Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925-934.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Leblebici C, Savli TC, Yeni B, et al. Palisaded encapsulated (solitary circumscribed) neuroma: a review of 30 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:506-514.

- Yeung CM, Moore L, Lans J, et al. Angioleiomyoma of the hand: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020; 8:373-377.

- Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:157-166.

A 54-year-old woman presented with an enlarging mass on the right volar forearm. Physical examination revealed a 1-cm, soft, mobile, subcutaneous nodule. Excision revealed tan-pink, indurated, fibrous, nodular tissue.

Product News October 2021

Opzelura FDA Approved for Atopic Dermatitis Incyte

Corporation announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream 1.5% for the short-term and noncontinuous chronic treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) in nonimmunocompromised patients 12 years and older whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. Opzelura is formulated with ruxolitinib, a selective Janus kinase (JAK) 1/JAK2 inhibitor, to target key cytokine signals believed to contribute to itch and inflammation. For more information, visit www.opzelurahcp.com/.

Twyneo FDA Approved for Acne Vulgaris

Sol-Gel Technologies, Ltd, announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Twyneo (tretinoin 0.1% /benzoyl peroxide 3%) cream for the treatment of acne vulgaris in adult and pediatric patients 9 years and older. Tretinoin and benzoyl peroxide are widely prescribed separately for acne vulgaris; however, benzoyl peroxide causes degradation of the tretinoin molecule, thereby potentially reducing its effectiveness if used at the same time or combined in the same formulation. The formulation of Twyneo uses silica (silicon dioxide) core shell structures to separately microencapsulate tretinoin crystals and benzoyl peroxide crystals, enabling inclusion of the 2 active ingredients in the cream. For more information, visit www.sol-gel.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@mdedge.com.

Opzelura FDA Approved for Atopic Dermatitis Incyte

Corporation announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream 1.5% for the short-term and noncontinuous chronic treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) in nonimmunocompromised patients 12 years and older whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. Opzelura is formulated with ruxolitinib, a selective Janus kinase (JAK) 1/JAK2 inhibitor, to target key cytokine signals believed to contribute to itch and inflammation. For more information, visit www.opzelurahcp.com/.

Twyneo FDA Approved for Acne Vulgaris

Sol-Gel Technologies, Ltd, announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Twyneo (tretinoin 0.1% /benzoyl peroxide 3%) cream for the treatment of acne vulgaris in adult and pediatric patients 9 years and older. Tretinoin and benzoyl peroxide are widely prescribed separately for acne vulgaris; however, benzoyl peroxide causes degradation of the tretinoin molecule, thereby potentially reducing its effectiveness if used at the same time or combined in the same formulation. The formulation of Twyneo uses silica (silicon dioxide) core shell structures to separately microencapsulate tretinoin crystals and benzoyl peroxide crystals, enabling inclusion of the 2 active ingredients in the cream. For more information, visit www.sol-gel.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@mdedge.com.

Opzelura FDA Approved for Atopic Dermatitis Incyte

Corporation announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream 1.5% for the short-term and noncontinuous chronic treatment of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis (AD) in nonimmunocompromised patients 12 years and older whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable. Opzelura is formulated with ruxolitinib, a selective Janus kinase (JAK) 1/JAK2 inhibitor, to target key cytokine signals believed to contribute to itch and inflammation. For more information, visit www.opzelurahcp.com/.

Twyneo FDA Approved for Acne Vulgaris

Sol-Gel Technologies, Ltd, announces US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Twyneo (tretinoin 0.1% /benzoyl peroxide 3%) cream for the treatment of acne vulgaris in adult and pediatric patients 9 years and older. Tretinoin and benzoyl peroxide are widely prescribed separately for acne vulgaris; however, benzoyl peroxide causes degradation of the tretinoin molecule, thereby potentially reducing its effectiveness if used at the same time or combined in the same formulation. The formulation of Twyneo uses silica (silicon dioxide) core shell structures to separately microencapsulate tretinoin crystals and benzoyl peroxide crystals, enabling inclusion of the 2 active ingredients in the cream. For more information, visit www.sol-gel.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@mdedge.com.

Underrepresented Minority Students Applying to Dermatology Residency in the COVID-19 Era: Challenges and Considerations

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores

The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) traditionally has been used to select dermatology residency applicants, with high cutoff scores often excluding outstanding URM students. Research has suggested that the use of USMLE examination test scores for residency recruitment lacks validity because it has poor predictability of residency performance.6 Although the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to pass/fail scoring, applicants for the next cycle will still have a 3-digit numerical score.

We strongly recommend that dermatology programs transition from emphasizing scores of residency candidates to reviewing each candidate holistically. The AAMC defines “holistic review” as a “flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities, by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, competencies, and academic or scholarly metrics and, when considered in combination, how the individual might contribute value to the institution’s mission.”7 Furthermore, we recommend that dermatology residency programs have multiple faculty members review each application, including a representative of the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee.

Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Virtual Environment

In the COVID-19 era, dermatology externship opportunities that would have allowed URM students to work directly with potential residency programs, showcase their abilities, and network have been limited. Virtual residency interviews could make it more challenging to evaluate candidates, especially URM students from less prestigious programs or unusual socioeconomic backgrounds, or with lower board scores. In addition, virtual interviews can more easily become one-dimensional, depriving URM students of the opportunity to gauge their personal fit in a specific dermatology residency program and its community. Questions and concerns of URM students might include: Will I be appropriately supported and mentored? Will my cultural preferences, religion, sexual preference, hairstyle, and beliefs be accepted? Can I advocate for minorities and support antiracism and diversity and inclusion initiatives? To that end, we recommend that dermatology programs continue to host virtual meet-and-greet events for potential students to meet faculty and learn more about the program. In addition, programs should consider having current residents interact virtually with candidates to allow students to better understand the culture of the department and residents’ experiences as trainees in such an environment. For URM students, this is highly important because diversity, inclusion, and antiracism policies and initiatives might not be explicitly available on the institution’s website or residency information page.

Organizations Championing Diversity

Recently, multiple dermatology societies and organizations have been emphasizing the need for diversity and inclusion as well as promoting holistic application review. The American Academy of Dermatology pioneered the Diversity Champion Workshop in 2019 and continues to offer the Diversity Mentorship program, connecting URM students to mentors nationally. The Skin of Color Society offers yearly grants and awards to medical students to develop mentorship and research, and recently hosted webinars to guide medical students and residency programs on diversity and inclusion, residency application and review, and COVID-19 virtual interviews. Other national societies, such as the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, have been promoting workshops and interview mentoring for URM students, including dermatology-specific events. Although it is estimated that more than 90% of medical schools in the United States already perform holistic application review and that such review has been adopted by many dermatology programs nationwide, data regarding dermatology residency programs’ implementation of holistic application review are lacking.8

In addition, we encourage continuation of the proposed coordinated interview invite release from the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which was implemented in the 2020-2021 cycle. In light of the recent AAMC letter9 on the maldistribution of interview invitations to highest-tier applicants, coordination of interview release dates and other similar initiatives to prevent programs from offering more invites than their available slots and improve transparency about interview days are needed. Furthermore, continuing to offer optional virtual interviews for applicants in future cycles could make the process less cost-prohibitive for many URM students.4,5

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residency programs must intentionally guard against falling back to traditional standards of assessment as the only means of student evaluation, especially in this virtual era. It is our responsibility to remove artificial barriers that continue to stall progress in diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging in dermatology.

- Underrepresented in medicine definition. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

- Diversity in medicine: facts and figures 2019. table 13. practice specialty, males by race/ethnicity, 2018. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-13-practice-specialty-males-race/ethnicity-2018 1B

- US Census Bureau. Quick facts: United States. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed September 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Vasquez R, Jeong H, Florez-Pollack S, et al. What are the barriers faced by underrepresented minorities applying to dermatology? a qualitative cross-sectional study of applicants applying to a large dermatology residency program. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1770-1773. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.067

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4813

- Williams C, Kwan B, Pereira A, et al. A call to improve conditions for conducting holistic review in graduate medical education recruitment. MedEdPublish. 2019;8:6. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2019.000076.1

- Holistic principles in resident selection: an introduction. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-08/aa-member-capacity-building-holistic-review-transcript-activities-GME-081420.pdf

- Luke J, Cornelius L, Lim H. Dermatology resident selection: shifting toward holistic review? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;84:1208-1209. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.025

- Open letter on residency interviews from Alison Whelan, MD, AAMC Chief Medical Education Officer. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/media/50291/download

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores

The US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) traditionally has been used to select dermatology residency applicants, with high cutoff scores often excluding outstanding URM students. Research has suggested that the use of USMLE examination test scores for residency recruitment lacks validity because it has poor predictability of residency performance.6 Although the USMLE Step 1 examination is transitioning to pass/fail scoring, applicants for the next cycle will still have a 3-digit numerical score.

We strongly recommend that dermatology programs transition from emphasizing scores of residency candidates to reviewing each candidate holistically. The AAMC defines “holistic review” as a “flexible, individualized way of assessing an applicant’s capabilities, by which balanced consideration is given to experiences, attributes, competencies, and academic or scholarly metrics and, when considered in combination, how the individual might contribute value to the institution’s mission.”7 Furthermore, we recommend that dermatology residency programs have multiple faculty members review each application, including a representative of the diversity, inclusion, and equity committee.

Applying to Residency in the COVID-19 Virtual Environment

In the COVID-19 era, dermatology externship opportunities that would have allowed URM students to work directly with potential residency programs, showcase their abilities, and network have been limited. Virtual residency interviews could make it more challenging to evaluate candidates, especially URM students from less prestigious programs or unusual socioeconomic backgrounds, or with lower board scores. In addition, virtual interviews can more easily become one-dimensional, depriving URM students of the opportunity to gauge their personal fit in a specific dermatology residency program and its community. Questions and concerns of URM students might include: Will I be appropriately supported and mentored? Will my cultural preferences, religion, sexual preference, hairstyle, and beliefs be accepted? Can I advocate for minorities and support antiracism and diversity and inclusion initiatives? To that end, we recommend that dermatology programs continue to host virtual meet-and-greet events for potential students to meet faculty and learn more about the program. In addition, programs should consider having current residents interact virtually with candidates to allow students to better understand the culture of the department and residents’ experiences as trainees in such an environment. For URM students, this is highly important because diversity, inclusion, and antiracism policies and initiatives might not be explicitly available on the institution’s website or residency information page.

Organizations Championing Diversity

Recently, multiple dermatology societies and organizations have been emphasizing the need for diversity and inclusion as well as promoting holistic application review. The American Academy of Dermatology pioneered the Diversity Champion Workshop in 2019 and continues to offer the Diversity Mentorship program, connecting URM students to mentors nationally. The Skin of Color Society offers yearly grants and awards to medical students to develop mentorship and research, and recently hosted webinars to guide medical students and residency programs on diversity and inclusion, residency application and review, and COVID-19 virtual interviews. Other national societies, such as the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association, have been promoting workshops and interview mentoring for URM students, including dermatology-specific events. Although it is estimated that more than 90% of medical schools in the United States already perform holistic application review and that such review has been adopted by many dermatology programs nationwide, data regarding dermatology residency programs’ implementation of holistic application review are lacking.8

In addition, we encourage continuation of the proposed coordinated interview invite release from the Association of Professors of Dermatology, which was implemented in the 2020-2021 cycle. In light of the recent AAMC letter9 on the maldistribution of interview invitations to highest-tier applicants, coordination of interview release dates and other similar initiatives to prevent programs from offering more invites than their available slots and improve transparency about interview days are needed. Furthermore, continuing to offer optional virtual interviews for applicants in future cycles could make the process less cost-prohibitive for many URM students.4,5

Final Thoughts

Dermatology residency programs must intentionally guard against falling back to traditional standards of assessment as the only means of student evaluation, especially in this virtual era. It is our responsibility to remove artificial barriers that continue to stall progress in diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging in dermatology.

The COVID-19 pandemic has markedly changed the dermatology residency application process. As medical students head into this application cycle, the impacts of systemic racism and deeply rooted structural barriers continue to be exacerbated for students who identify as an underrepresented minority (URM) in medicine—historically defined as those who self-identify as Hispanic or Latinx; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native; or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines URMs as racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in medicine relative to their numbers in the general population.1 Although these groups account for approximately 34% of the population of the United States, they constitute only 11% of the country’s physician workforce.2,3

Of the total physician workforce in the United States, Black and African American physicians account for 5% of practicing physicians; Hispanic physicians, 5.8%; American Indian and Alaska Native physicians, 0.3%; and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander physicians, 0.1%.2 In competitive medical specialties, the disproportionality of these numbers compared to our current demographics in the United States as shown above is even more staggering. In 2018, for example, 10% of practicing dermatologists identified as female URM physicians; 6%, as male URM physicians.2 In this article, we discuss some of the challenges and considerations for URM students applying to dermatology residency in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Barriers for URM Students in Dermatology

Multiple studies have attempted to identify some of the barriers faced by URM students in medicine that might explain the lack of diversity in competitive specialties. Vasquez and colleagues4 identified 4 major factors that play a role in dermatology: lack of equitable resources, lack of support, financial limitations, and the lack of group identity. More than half of URM students surveyed (1) identified lack of support as a barrier and (2) reported having been encouraged to seek a specialty more reflective of their community.4

Soliman et al5 reported that URM barriers in dermatology extend to include lack of diversity in the field, socioeconomic factors, lack of mentorship, and a negative perception of minority students by residency programs. Dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine after orthopedic surgery, which, in and of itself, might further discourage URM students from applying to dermatology.5

With the minimal exposure that URM students have to the field of dermatology, the lack of pipeline programs, and reports that URMs often are encouraged to pursue primary care, the current diversity deficiency in dermatology comes as no surprise. In addition, the substantial disadvantage for URM students is perpetuated by the traditional highly selective process that favors grades, board scores, and honor society status over holistic assessment of the individual student and their unique experiences and potential for contribution.

Looking Beyond Test Scores