User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

FDA approves injectable diabetes drug that improves A1c scores

The Food and Drug Administration has approved semaglutide (OZEMPIC) injections for treatment of type 2 diabetes in adults, according to a press release from Novo Nordisk.

Semaglutide is a once-weekly injection of glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) receptor agonist that, combined with diet and exercise, can improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Weekly injections are administered by health care providers in a prefilled pen subcutaneously in the stomach, abdomen, thigh, or upper arm as a 0.5-mg or 1-mg formulation. It is important that all doses be administered on the same day each week, according to the OZEMPIC package insert.

“The OZEMPIC (semaglutide) approval builds on Novo Nordisk’s commitment to offering health care professionals a range of treatments that effectively addresses the complex needs of diabetes management and fits their patients’ lifestyles,” said Todd Hobbs, vice president and U.S. chief medical officer of Novo Nordisk.

To ensure access to semaglutide, Novo Nordisk is pricing the drug competitively with other GLP-1 receptor agonists and will offer an associated savings card program to reduce copays for insured patients, the company said. Novo Nordisk expects to launch OZEMPIC in the United States in the first quarter of 2018, and is working on contracting solutions with health insurance providers to increase patient access to the drug.

According to the Novo Nordisk statement, clinicians should not consider semaglutide as a first choice option for treating diabetes or as a substitute for insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes and diabetic ketoacidosis. Whether semaglutide can be used by people who have had pancreatitis or is safe in patients under the age of 18 years old remains to be seen.

“Type 2 diabetes is a serious condition that affects more than 28 million people in the U.S., and despite advancements in treatment, some people with type 2 diabetes do not achieve their A1c goals,” said Helena Rodbard, MD, past president of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. “The approval of semaglutide offers health care professionals an important new treatment option to help adults with type 2 diabetes meet their A1c goals.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved semaglutide (OZEMPIC) injections for treatment of type 2 diabetes in adults, according to a press release from Novo Nordisk.

Semaglutide is a once-weekly injection of glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) receptor agonist that, combined with diet and exercise, can improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Weekly injections are administered by health care providers in a prefilled pen subcutaneously in the stomach, abdomen, thigh, or upper arm as a 0.5-mg or 1-mg formulation. It is important that all doses be administered on the same day each week, according to the OZEMPIC package insert.

“The OZEMPIC (semaglutide) approval builds on Novo Nordisk’s commitment to offering health care professionals a range of treatments that effectively addresses the complex needs of diabetes management and fits their patients’ lifestyles,” said Todd Hobbs, vice president and U.S. chief medical officer of Novo Nordisk.

To ensure access to semaglutide, Novo Nordisk is pricing the drug competitively with other GLP-1 receptor agonists and will offer an associated savings card program to reduce copays for insured patients, the company said. Novo Nordisk expects to launch OZEMPIC in the United States in the first quarter of 2018, and is working on contracting solutions with health insurance providers to increase patient access to the drug.

According to the Novo Nordisk statement, clinicians should not consider semaglutide as a first choice option for treating diabetes or as a substitute for insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes and diabetic ketoacidosis. Whether semaglutide can be used by people who have had pancreatitis or is safe in patients under the age of 18 years old remains to be seen.

“Type 2 diabetes is a serious condition that affects more than 28 million people in the U.S., and despite advancements in treatment, some people with type 2 diabetes do not achieve their A1c goals,” said Helena Rodbard, MD, past president of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. “The approval of semaglutide offers health care professionals an important new treatment option to help adults with type 2 diabetes meet their A1c goals.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved semaglutide (OZEMPIC) injections for treatment of type 2 diabetes in adults, according to a press release from Novo Nordisk.

Semaglutide is a once-weekly injection of glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) receptor agonist that, combined with diet and exercise, can improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Weekly injections are administered by health care providers in a prefilled pen subcutaneously in the stomach, abdomen, thigh, or upper arm as a 0.5-mg or 1-mg formulation. It is important that all doses be administered on the same day each week, according to the OZEMPIC package insert.

“The OZEMPIC (semaglutide) approval builds on Novo Nordisk’s commitment to offering health care professionals a range of treatments that effectively addresses the complex needs of diabetes management and fits their patients’ lifestyles,” said Todd Hobbs, vice president and U.S. chief medical officer of Novo Nordisk.

To ensure access to semaglutide, Novo Nordisk is pricing the drug competitively with other GLP-1 receptor agonists and will offer an associated savings card program to reduce copays for insured patients, the company said. Novo Nordisk expects to launch OZEMPIC in the United States in the first quarter of 2018, and is working on contracting solutions with health insurance providers to increase patient access to the drug.

According to the Novo Nordisk statement, clinicians should not consider semaglutide as a first choice option for treating diabetes or as a substitute for insulin in patients with type 1 diabetes and diabetic ketoacidosis. Whether semaglutide can be used by people who have had pancreatitis or is safe in patients under the age of 18 years old remains to be seen.

“Type 2 diabetes is a serious condition that affects more than 28 million people in the U.S., and despite advancements in treatment, some people with type 2 diabetes do not achieve their A1c goals,” said Helena Rodbard, MD, past president of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. “The approval of semaglutide offers health care professionals an important new treatment option to help adults with type 2 diabetes meet their A1c goals.”

Aim for BP a bit above SPRINT

ANAHEIM – If blood pressure isn’t measured the way it was in the SPRINT trial, it shouldn’t be treated all the way down to the SPRINT target of less than 120 mm Hg; it’s best to aim a little higher, according to investigators from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California.

SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) found that treating hypertension to below 120 mm Hg – as opposed to below 140 mm Hg – reduced the risk of cardiovascular events and death, but blood pressure wasn’t measured the way it usually is in standard practice. Among other differences, SPRINT subjects rested for 5 minutes beforehand, sometimes unobserved, and then three automated measurements were taken and averaged (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2103-16).

In a review of 73,522 hypertensive patients, the Kaiser investigators found that those treated to a mean systolic BP (SBP) of 122 mm Hg – based on standard office measurement – actually had worse outcomes than did those treated to a mean of 132 mm Hg, with a greater incidence of cardiovascular events, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

“The way SPRINT measured BP was systematically different than the BPs we rely on to treat patients in clinical practice. We think that, unless you are going to implement a SPRINT-like protocol, aiming for a slightly higher target of around a mean of 130-132 mm Hg will achieve optimal outcomes. You are likely achieving a SPRINT BP of around 120-125 mm Hg,” said Alan Go, MD, director of the comprehensive clinical research unit at Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, Oakland.

Meanwhile, “if you [treat] to 120 mm Hg, you are probably getting around a SPRINT 114 mm Hg. That runs the risk of hypotension, which we did see. There is also the potential for coronary ischemia because you are no longer providing adequate coronary perfusion,” he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In their “SPRINT to translation” study, Dr. Go and his team reviewed Kaiser’s electronic medical records to identify patients with baseline BPs of 130-180 mm Hg who met SPRINT criteria and then evaluated how they fared over about 6 years of blood pressure management, with at least one BP taken every 6 months; 7,213 patients were treated to an SBP of 140-149 mm Hg and a mean of 143 mm Hg; 44,847 were treated to an SBP of 126-139 mm Hg and a mean of 132 mm Hg; and 21,462 were treated to 115-125 mm Hg and a mean of 122 mm Hg.

After extensive adjustment for potential confounders, patients treated to 140-149 mm Hg, versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, had a 70% increased risk of the composite outcome of acute MI, unstable angina, heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular death, and a 28% increased risk of all-cause mortality. They also had an increased risk of acute kidney injury, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

More surprisingly, patients treated to 115-125 mm Hg, again versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, also had an increased risk of the composite outcome of 9%. They had lower rates of MI and ischemic stroke, but higher rates of heart failure and cardiovascular death. There was also a 17% increased risk of acute kidney injury and a 51% increased risk of hypotension requiring ED or hospital treatment, as well as more electrolyte abnormalities.

The 115-125 mm Hg group also had a 48% increased risk of all-cause mortality. The magnitude of the increase suggests that low blood pressure was a secondary effect of terminal illness in some cases, but Dr. Go didn’t think that was the entire explanation.

The participants had a mean age of 70 years; 63% were women and 75% were white. As in SPRINT, patients with baseline heart failure, stroke, systolic dysfunction, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, and cancer were among those excluded.

There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

ANAHEIM – If blood pressure isn’t measured the way it was in the SPRINT trial, it shouldn’t be treated all the way down to the SPRINT target of less than 120 mm Hg; it’s best to aim a little higher, according to investigators from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California.

SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) found that treating hypertension to below 120 mm Hg – as opposed to below 140 mm Hg – reduced the risk of cardiovascular events and death, but blood pressure wasn’t measured the way it usually is in standard practice. Among other differences, SPRINT subjects rested for 5 minutes beforehand, sometimes unobserved, and then three automated measurements were taken and averaged (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2103-16).

In a review of 73,522 hypertensive patients, the Kaiser investigators found that those treated to a mean systolic BP (SBP) of 122 mm Hg – based on standard office measurement – actually had worse outcomes than did those treated to a mean of 132 mm Hg, with a greater incidence of cardiovascular events, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

“The way SPRINT measured BP was systematically different than the BPs we rely on to treat patients in clinical practice. We think that, unless you are going to implement a SPRINT-like protocol, aiming for a slightly higher target of around a mean of 130-132 mm Hg will achieve optimal outcomes. You are likely achieving a SPRINT BP of around 120-125 mm Hg,” said Alan Go, MD, director of the comprehensive clinical research unit at Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, Oakland.

Meanwhile, “if you [treat] to 120 mm Hg, you are probably getting around a SPRINT 114 mm Hg. That runs the risk of hypotension, which we did see. There is also the potential for coronary ischemia because you are no longer providing adequate coronary perfusion,” he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In their “SPRINT to translation” study, Dr. Go and his team reviewed Kaiser’s electronic medical records to identify patients with baseline BPs of 130-180 mm Hg who met SPRINT criteria and then evaluated how they fared over about 6 years of blood pressure management, with at least one BP taken every 6 months; 7,213 patients were treated to an SBP of 140-149 mm Hg and a mean of 143 mm Hg; 44,847 were treated to an SBP of 126-139 mm Hg and a mean of 132 mm Hg; and 21,462 were treated to 115-125 mm Hg and a mean of 122 mm Hg.

After extensive adjustment for potential confounders, patients treated to 140-149 mm Hg, versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, had a 70% increased risk of the composite outcome of acute MI, unstable angina, heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular death, and a 28% increased risk of all-cause mortality. They also had an increased risk of acute kidney injury, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

More surprisingly, patients treated to 115-125 mm Hg, again versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, also had an increased risk of the composite outcome of 9%. They had lower rates of MI and ischemic stroke, but higher rates of heart failure and cardiovascular death. There was also a 17% increased risk of acute kidney injury and a 51% increased risk of hypotension requiring ED or hospital treatment, as well as more electrolyte abnormalities.

The 115-125 mm Hg group also had a 48% increased risk of all-cause mortality. The magnitude of the increase suggests that low blood pressure was a secondary effect of terminal illness in some cases, but Dr. Go didn’t think that was the entire explanation.

The participants had a mean age of 70 years; 63% were women and 75% were white. As in SPRINT, patients with baseline heart failure, stroke, systolic dysfunction, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, and cancer were among those excluded.

There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

ANAHEIM – If blood pressure isn’t measured the way it was in the SPRINT trial, it shouldn’t be treated all the way down to the SPRINT target of less than 120 mm Hg; it’s best to aim a little higher, according to investigators from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California.

SPRINT (the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) found that treating hypertension to below 120 mm Hg – as opposed to below 140 mm Hg – reduced the risk of cardiovascular events and death, but blood pressure wasn’t measured the way it usually is in standard practice. Among other differences, SPRINT subjects rested for 5 minutes beforehand, sometimes unobserved, and then three automated measurements were taken and averaged (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2103-16).

In a review of 73,522 hypertensive patients, the Kaiser investigators found that those treated to a mean systolic BP (SBP) of 122 mm Hg – based on standard office measurement – actually had worse outcomes than did those treated to a mean of 132 mm Hg, with a greater incidence of cardiovascular events, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

“The way SPRINT measured BP was systematically different than the BPs we rely on to treat patients in clinical practice. We think that, unless you are going to implement a SPRINT-like protocol, aiming for a slightly higher target of around a mean of 130-132 mm Hg will achieve optimal outcomes. You are likely achieving a SPRINT BP of around 120-125 mm Hg,” said Alan Go, MD, director of the comprehensive clinical research unit at Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, Oakland.

Meanwhile, “if you [treat] to 120 mm Hg, you are probably getting around a SPRINT 114 mm Hg. That runs the risk of hypotension, which we did see. There is also the potential for coronary ischemia because you are no longer providing adequate coronary perfusion,” he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In their “SPRINT to translation” study, Dr. Go and his team reviewed Kaiser’s electronic medical records to identify patients with baseline BPs of 130-180 mm Hg who met SPRINT criteria and then evaluated how they fared over about 6 years of blood pressure management, with at least one BP taken every 6 months; 7,213 patients were treated to an SBP of 140-149 mm Hg and a mean of 143 mm Hg; 44,847 were treated to an SBP of 126-139 mm Hg and a mean of 132 mm Hg; and 21,462 were treated to 115-125 mm Hg and a mean of 122 mm Hg.

After extensive adjustment for potential confounders, patients treated to 140-149 mm Hg, versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, had a 70% increased risk of the composite outcome of acute MI, unstable angina, heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular death, and a 28% increased risk of all-cause mortality. They also had an increased risk of acute kidney injury, electrolyte abnormalities, and other problems.

More surprisingly, patients treated to 115-125 mm Hg, again versus those treated to 126-139 mm Hg, also had an increased risk of the composite outcome of 9%. They had lower rates of MI and ischemic stroke, but higher rates of heart failure and cardiovascular death. There was also a 17% increased risk of acute kidney injury and a 51% increased risk of hypotension requiring ED or hospital treatment, as well as more electrolyte abnormalities.

The 115-125 mm Hg group also had a 48% increased risk of all-cause mortality. The magnitude of the increase suggests that low blood pressure was a secondary effect of terminal illness in some cases, but Dr. Go didn’t think that was the entire explanation.

The participants had a mean age of 70 years; 63% were women and 75% were white. As in SPRINT, patients with baseline heart failure, stroke, systolic dysfunction, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, and cancer were among those excluded.

There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Cardiovascular events were 9% more likely in patients treated to 115-125 mm Hg vs. those treated to 126-139 mm Hg.

Data source: Review of 73,522 hypertensive patients at Kaiser Permanente of Northern California

Disclosures: There was no external funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

The Liver Meeting 2017 NAFLD debrief – key abstracts

WASHINGTON – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a complex disease that involves multiple systems, and several standout abstracts at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases emphasized the importance of multisystem management and the potential of combination therapies, Kymberly D. Watt, MD, said during the final debrief.

“The actual underlying mechanisms and the underlying processes that are going on are way more complicated than just inflammation and scarring,” said Dr. Watt, associate professor of medicine and medical director of liver transplantation at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. “We have numerous areas to target, including insulin resistance, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, inflammation, immune modulation, cell death, etc.”

She noted several studies that evaluated the prevalence of NAFLD, including a study that found that “about one-third of patients walking through the door of the clinic had nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH],” suggesting physicians should consider screening at-risk patients (abstract 58). A Korean study found about 18% of asymptomatic lean individuals (body mass index less than 23 kg/m2) had NAFLD and identified sarcopenia as a significant risk factor for NAFLD in these lean patients (abstract 59). “Sarcopenia is something that we really need to pay a lot more attention to,” Dr. Watt said.

Other studies better outlined the increasing association between NAFLD and hepatocellular carcinoma, Dr. Watt noted (abstracts 2119 and 2102). Another study confirmed that men with NAFLD/NASH have almost twice the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as women — 0.43%-0.5% vs. 0.22%-0.28%, with both groups significantly higher than the general population (abstract 2116). “And looking further, we can actually quote an HCC incidence in NASH of 0.009%,” she added.

Again emphasizing the multisystem impact of NAFLD, Dr. Watt cited a study that calculated the cardiovascular risks incumbent with liver disease. Researchers reported that men and women at the time of NAFLD diagnosis had significantly higher rates of either angina/ischemic heart disease or heart failure (abstract 55). Women, specifically, had a higher risk for cardiovascular events earlier than men and overall are at equal risk to men, unlike in the general population where women are at lower risk. “We need to start looking at screening and prevention of other diseases in our patients with NASH,” Dr. Watt said. “In addition, we need to be more aware of the elevated risk in these patients and not just approach them in the same way as the general population.”

Physicians may be tempted to discontinue statin therapy in patients with chronic liver disease, but Dr. Watt cited a poster that showed that this results in worse outcomes (abstract 2106). The researchers found that continued statin use was associated with a lower risk of death with compensated and decompensated liver function. “These data help to educate certain patients of their risk of decompensation over time,” Dr. Watt said.

An international study determined that the severity of advanced compensated liver disease is a key determinant in outcomes, finding that those with bridging fibrosis are at greater risk of vascular events, but those with cirrhosis and Child-Turcotte-Pugh A5 and A6 disease have much higher risks of hepatic decompensation and HCC out to 14 years (abstract 60). “The reason to look at these is to be able to tell your patients that they probably have a 30% increased risk of decompensation by 4 years,” Dr. Watt said.

Dr. Watt pointed out three studies that shed more light on important biomarkers of NAFLD. One study reported that three biomarkers – alpha-2-macroglobulin, hyaluronic acid, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 – have a high sensitivity for differentiating low-stage and stage F3-F4 disease (abstract 95). Another study found that a measure using Pro-C3 and other clinical markers were predictive of F3 or F4 fibrosis in NAFLD (abstract 93). And, other researchers found that a HepQuant-STAT measure of greater than 0.50 microM in patients who ingested deuterated cholic acid (d4-CA) solution may be a minimally invasive alternative to biopsy for diagnosing NASH (abstract 96).

Management studies focusing on varying targets were also presented. A trial of fibroblast growth factor–21 for treatment of NAFLD found that patients in the 10- and 20-mg dose arms showed improvement in MRI hepatic fat fraction, ALT, AST, and liver stiffness at 16 weeks vs. placebo. A few patients had some mild elevation to their liver enzymes on treatment (abstract 182). “So I think we need to remain cautious and watch these patients closely, but overall it seems to be reasonably safe data,” she said. Another drug trial of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitor GS-0976 also showed promise for overall improvement in MRI steatosis measures (abstract LB-9).

Three preclinical studies of dual-agent therapies in animals have demonstrated improvement in inflammatory and fibrosis scores, Dr. Watt noted (abstracts 2,000, 2,002 and 2,052). “There’s no one drug that’s going to be likely the magic cure,” Dr. Watt said. “There will likely be a lot more focus and data coming out on dual-action agents.” Another animal study addressed the burning question if decaffeinated coffee has the same protective effect against NASH as caffeinated coffee (abstract 2093). Said Dr. Watt: “If you are interested in the potential benefits of coffee but really can’t handle the caffeine, this study suggests, you may still be OK.”

Finally, Dr. Watt noted an early study of three-dimensional printing has shown potential for replicating NASH tissue for bench studies (abstract 1963). “3-D printing is certainly a wave of the future,” she said, pointing out that researchers have created a 3-D model that has some metabolic equivalency to NASH, with the inflammatory cytokine release, hepatic stellate cell activation, “and all of the features that we see in NASH. This may be of potential use down the road to avoid relying on animal models in preclinical studies.”

The Liver Meeting next convenes Nov. 9-13, 2018, in San Francisco.

Dr. Watt disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, and Seattle Genetics.

WASHINGTON – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a complex disease that involves multiple systems, and several standout abstracts at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases emphasized the importance of multisystem management and the potential of combination therapies, Kymberly D. Watt, MD, said during the final debrief.

“The actual underlying mechanisms and the underlying processes that are going on are way more complicated than just inflammation and scarring,” said Dr. Watt, associate professor of medicine and medical director of liver transplantation at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. “We have numerous areas to target, including insulin resistance, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, inflammation, immune modulation, cell death, etc.”

She noted several studies that evaluated the prevalence of NAFLD, including a study that found that “about one-third of patients walking through the door of the clinic had nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH],” suggesting physicians should consider screening at-risk patients (abstract 58). A Korean study found about 18% of asymptomatic lean individuals (body mass index less than 23 kg/m2) had NAFLD and identified sarcopenia as a significant risk factor for NAFLD in these lean patients (abstract 59). “Sarcopenia is something that we really need to pay a lot more attention to,” Dr. Watt said.

Other studies better outlined the increasing association between NAFLD and hepatocellular carcinoma, Dr. Watt noted (abstracts 2119 and 2102). Another study confirmed that men with NAFLD/NASH have almost twice the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as women — 0.43%-0.5% vs. 0.22%-0.28%, with both groups significantly higher than the general population (abstract 2116). “And looking further, we can actually quote an HCC incidence in NASH of 0.009%,” she added.

Again emphasizing the multisystem impact of NAFLD, Dr. Watt cited a study that calculated the cardiovascular risks incumbent with liver disease. Researchers reported that men and women at the time of NAFLD diagnosis had significantly higher rates of either angina/ischemic heart disease or heart failure (abstract 55). Women, specifically, had a higher risk for cardiovascular events earlier than men and overall are at equal risk to men, unlike in the general population where women are at lower risk. “We need to start looking at screening and prevention of other diseases in our patients with NASH,” Dr. Watt said. “In addition, we need to be more aware of the elevated risk in these patients and not just approach them in the same way as the general population.”

Physicians may be tempted to discontinue statin therapy in patients with chronic liver disease, but Dr. Watt cited a poster that showed that this results in worse outcomes (abstract 2106). The researchers found that continued statin use was associated with a lower risk of death with compensated and decompensated liver function. “These data help to educate certain patients of their risk of decompensation over time,” Dr. Watt said.

An international study determined that the severity of advanced compensated liver disease is a key determinant in outcomes, finding that those with bridging fibrosis are at greater risk of vascular events, but those with cirrhosis and Child-Turcotte-Pugh A5 and A6 disease have much higher risks of hepatic decompensation and HCC out to 14 years (abstract 60). “The reason to look at these is to be able to tell your patients that they probably have a 30% increased risk of decompensation by 4 years,” Dr. Watt said.

Dr. Watt pointed out three studies that shed more light on important biomarkers of NAFLD. One study reported that three biomarkers – alpha-2-macroglobulin, hyaluronic acid, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 – have a high sensitivity for differentiating low-stage and stage F3-F4 disease (abstract 95). Another study found that a measure using Pro-C3 and other clinical markers were predictive of F3 or F4 fibrosis in NAFLD (abstract 93). And, other researchers found that a HepQuant-STAT measure of greater than 0.50 microM in patients who ingested deuterated cholic acid (d4-CA) solution may be a minimally invasive alternative to biopsy for diagnosing NASH (abstract 96).

Management studies focusing on varying targets were also presented. A trial of fibroblast growth factor–21 for treatment of NAFLD found that patients in the 10- and 20-mg dose arms showed improvement in MRI hepatic fat fraction, ALT, AST, and liver stiffness at 16 weeks vs. placebo. A few patients had some mild elevation to their liver enzymes on treatment (abstract 182). “So I think we need to remain cautious and watch these patients closely, but overall it seems to be reasonably safe data,” she said. Another drug trial of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitor GS-0976 also showed promise for overall improvement in MRI steatosis measures (abstract LB-9).

Three preclinical studies of dual-agent therapies in animals have demonstrated improvement in inflammatory and fibrosis scores, Dr. Watt noted (abstracts 2,000, 2,002 and 2,052). “There’s no one drug that’s going to be likely the magic cure,” Dr. Watt said. “There will likely be a lot more focus and data coming out on dual-action agents.” Another animal study addressed the burning question if decaffeinated coffee has the same protective effect against NASH as caffeinated coffee (abstract 2093). Said Dr. Watt: “If you are interested in the potential benefits of coffee but really can’t handle the caffeine, this study suggests, you may still be OK.”

Finally, Dr. Watt noted an early study of three-dimensional printing has shown potential for replicating NASH tissue for bench studies (abstract 1963). “3-D printing is certainly a wave of the future,” she said, pointing out that researchers have created a 3-D model that has some metabolic equivalency to NASH, with the inflammatory cytokine release, hepatic stellate cell activation, “and all of the features that we see in NASH. This may be of potential use down the road to avoid relying on animal models in preclinical studies.”

The Liver Meeting next convenes Nov. 9-13, 2018, in San Francisco.

Dr. Watt disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, and Seattle Genetics.

WASHINGTON – Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a complex disease that involves multiple systems, and several standout abstracts at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases emphasized the importance of multisystem management and the potential of combination therapies, Kymberly D. Watt, MD, said during the final debrief.

“The actual underlying mechanisms and the underlying processes that are going on are way more complicated than just inflammation and scarring,” said Dr. Watt, associate professor of medicine and medical director of liver transplantation at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. “We have numerous areas to target, including insulin resistance, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, inflammation, immune modulation, cell death, etc.”

She noted several studies that evaluated the prevalence of NAFLD, including a study that found that “about one-third of patients walking through the door of the clinic had nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH],” suggesting physicians should consider screening at-risk patients (abstract 58). A Korean study found about 18% of asymptomatic lean individuals (body mass index less than 23 kg/m2) had NAFLD and identified sarcopenia as a significant risk factor for NAFLD in these lean patients (abstract 59). “Sarcopenia is something that we really need to pay a lot more attention to,” Dr. Watt said.

Other studies better outlined the increasing association between NAFLD and hepatocellular carcinoma, Dr. Watt noted (abstracts 2119 and 2102). Another study confirmed that men with NAFLD/NASH have almost twice the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as women — 0.43%-0.5% vs. 0.22%-0.28%, with both groups significantly higher than the general population (abstract 2116). “And looking further, we can actually quote an HCC incidence in NASH of 0.009%,” she added.

Again emphasizing the multisystem impact of NAFLD, Dr. Watt cited a study that calculated the cardiovascular risks incumbent with liver disease. Researchers reported that men and women at the time of NAFLD diagnosis had significantly higher rates of either angina/ischemic heart disease or heart failure (abstract 55). Women, specifically, had a higher risk for cardiovascular events earlier than men and overall are at equal risk to men, unlike in the general population where women are at lower risk. “We need to start looking at screening and prevention of other diseases in our patients with NASH,” Dr. Watt said. “In addition, we need to be more aware of the elevated risk in these patients and not just approach them in the same way as the general population.”

Physicians may be tempted to discontinue statin therapy in patients with chronic liver disease, but Dr. Watt cited a poster that showed that this results in worse outcomes (abstract 2106). The researchers found that continued statin use was associated with a lower risk of death with compensated and decompensated liver function. “These data help to educate certain patients of their risk of decompensation over time,” Dr. Watt said.

An international study determined that the severity of advanced compensated liver disease is a key determinant in outcomes, finding that those with bridging fibrosis are at greater risk of vascular events, but those with cirrhosis and Child-Turcotte-Pugh A5 and A6 disease have much higher risks of hepatic decompensation and HCC out to 14 years (abstract 60). “The reason to look at these is to be able to tell your patients that they probably have a 30% increased risk of decompensation by 4 years,” Dr. Watt said.

Dr. Watt pointed out three studies that shed more light on important biomarkers of NAFLD. One study reported that three biomarkers – alpha-2-macroglobulin, hyaluronic acid, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 – have a high sensitivity for differentiating low-stage and stage F3-F4 disease (abstract 95). Another study found that a measure using Pro-C3 and other clinical markers were predictive of F3 or F4 fibrosis in NAFLD (abstract 93). And, other researchers found that a HepQuant-STAT measure of greater than 0.50 microM in patients who ingested deuterated cholic acid (d4-CA) solution may be a minimally invasive alternative to biopsy for diagnosing NASH (abstract 96).

Management studies focusing on varying targets were also presented. A trial of fibroblast growth factor–21 for treatment of NAFLD found that patients in the 10- and 20-mg dose arms showed improvement in MRI hepatic fat fraction, ALT, AST, and liver stiffness at 16 weeks vs. placebo. A few patients had some mild elevation to their liver enzymes on treatment (abstract 182). “So I think we need to remain cautious and watch these patients closely, but overall it seems to be reasonably safe data,” she said. Another drug trial of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitor GS-0976 also showed promise for overall improvement in MRI steatosis measures (abstract LB-9).

Three preclinical studies of dual-agent therapies in animals have demonstrated improvement in inflammatory and fibrosis scores, Dr. Watt noted (abstracts 2,000, 2,002 and 2,052). “There’s no one drug that’s going to be likely the magic cure,” Dr. Watt said. “There will likely be a lot more focus and data coming out on dual-action agents.” Another animal study addressed the burning question if decaffeinated coffee has the same protective effect against NASH as caffeinated coffee (abstract 2093). Said Dr. Watt: “If you are interested in the potential benefits of coffee but really can’t handle the caffeine, this study suggests, you may still be OK.”

Finally, Dr. Watt noted an early study of three-dimensional printing has shown potential for replicating NASH tissue for bench studies (abstract 1963). “3-D printing is certainly a wave of the future,” she said, pointing out that researchers have created a 3-D model that has some metabolic equivalency to NASH, with the inflammatory cytokine release, hepatic stellate cell activation, “and all of the features that we see in NASH. This may be of potential use down the road to avoid relying on animal models in preclinical studies.”

The Liver Meeting next convenes Nov. 9-13, 2018, in San Francisco.

Dr. Watt disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, and Seattle Genetics.

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2017

Key clinical point: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease involves treatment and management of multiple systems.

Major finding: Physicians managing NAFLD must target insulin resistance, lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, and more.

Data source: Debrief of key abstracts on NAFLD presented at the Liver Meeting 2017.

Disclosures: Dr. Watt reported having relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, and Seattle Genetics.

VIDEO: U.S. hypertension guidelines reset threshold to 130/80 mm Hg

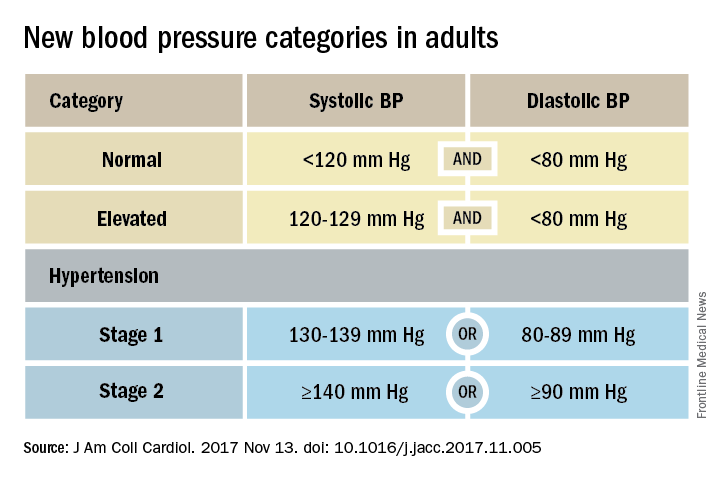

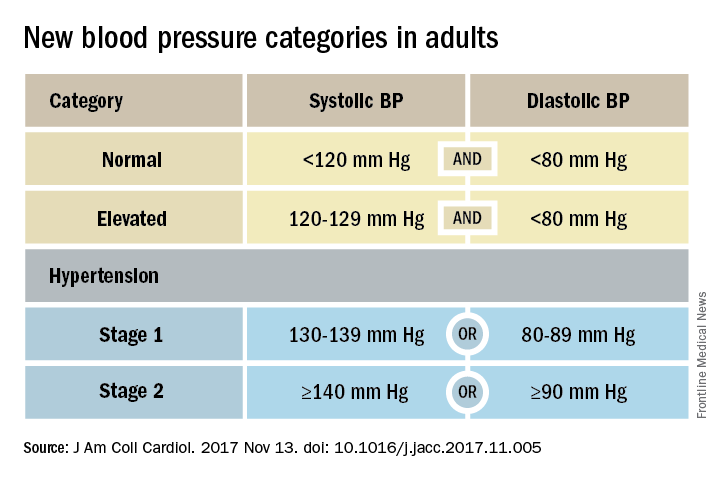

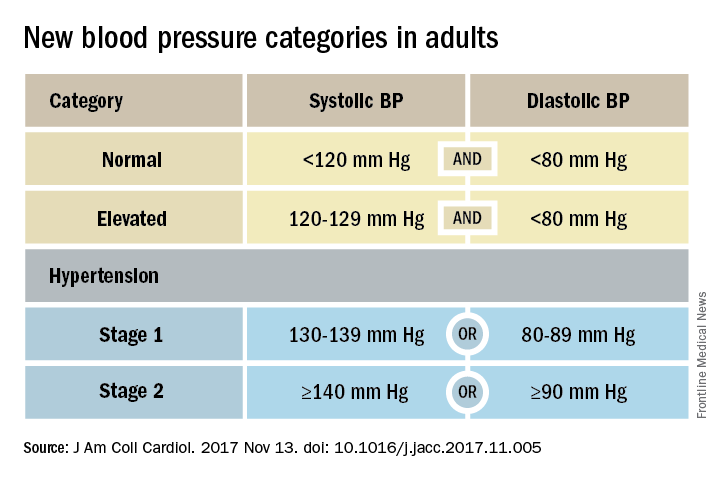

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Experts question insulin as top choice in GDM

WASHINGTON – The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ conclusion that insulin should be considered the first-line pharmacologic treatment for gestational diabetes came under fire at a recent meeting on diabetes in pregnancy, indicating the extent to which controversy persists over the use of oral antidiabetic medications in pregnancy.

“Like many others, I’m perplexed by the strong endorsement,” Mark Landon, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Ohio State University, Columbus, said during an open discussion of oral hypoglycemic agents held at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

Dr. Landon and several other researchers and experts in diabetes in pregnancy expressed discontent with any firm prioritization of the drugs most commonly used for gestational diabetes, saying that there are not yet enough data to do so.

The endorsement of insulin as the first-line option when pharmacologic treatment is needed is a level A conclusion/recommendation in ACOG’s updated practice bulletin on gestational diabetes mellitus, released in July 2017 (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130[1]:e17-37). In accompanying level B recommendations, ACOG stated that in women who decline insulin therapy or who are believed to be “unable to safely administer insulin,” metformin is a “reasonable second-line choice.” Glyburide “should not be recommended as a first-line pharmacologic treatment because, in most studies, it does not yield equivalent outcomes to insulin.”

Level A recommendations are defined as “based on good and consistent scientific evidence,” while the evidence for level B recommendations is “limited or inconsistent.”

Asked to comment on the concerns voiced at the meeting, an ACOG spokeswoman said that the recommendations were developed after a thorough literature review, but that the evidence was being reexamined with the option of updating the practice bulletin.

Current recommendations

In its practice bulletin, ACOG noted that oral antidiabetic medications, such as glyburide and metformin, are increasingly used among women with GDM, despite not being approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication and even though insulin continues to be the recommended as first-line therapy by the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

The ADA, in a summary of its 2017 guideline on the management of diabetes in pregnancy, stated that insulin is the “preferred medication for treating hyperglycemia in gestational diabetes mellitus, as it does not cross the placenta to a measurable extent.” Metformin and glyburide are options, “but both cross the placenta to the fetus, with metformin likely crossing to a greater extent than glyburide” (Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40[Suppl 1]:S114- 9).Regarding metformin, the ACOG bulletin cited two trials that randomized women to metformin or insulin – one in which both groups experienced similar rates of a composite outcome of perinatal morbidity, and another in which women receiving metformin had lower mean glucose levels, less gestational weight gain, and neonates with lower rates of hypoglycemia.

ACOG also cited a meta-analysis, that found “minimal differences” between neonates of women randomized to metformin versus insulin, but also noted that “interestingly, women randomized to metformin experienced a higher rate of preterm birth” and a lower rate of gestational hypertension (BMJ. 2015;350:h102).

With respect to glyburide, the ACOG bulletin said that two recent meta-analyses had demonstrated worse neonatal outcomes with glyburide, compared with insulin, and that observational studies have shown higher rates of preeclampsia, hyperbilirubinemia, and stillbirth with the use of glyburide, compared with insulin. However, many other outcomes have not been statistically significantly different, according to the practice bulletin.

Additionally, at least 4%-16% of women eventually require the addition of insulin when glyburide is used as initial treatment, as do 26%-46% of women who take metformin, according to ACOG.

Regarding placental transfer, ACOG’s bulletin said that while one study that analyzed umbilical cord blood revealed no detectable glyburide in exposed pregnancies, another study demonstrated that glyburide does cross the placenta. Metformin has also been found to cross the placenta, with the fetus exposed to concentrations similar to maternal levels, the bulletin noted.

“Although current data demonstrate no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal health from oral diabetic therapy during pregnancy, long-term outcomes are not yet available,” ACOG wrote in the practice bulletin.

Concerns about research

As Thomas Moore, MD, sees it, the quality of available data is insufficient to recommend insulin over oral agents, or one oral agent over another. “We really need to focus [the National Institutes of Health] on putting together proper studies,” he said at the meeting.

In a later interview, Dr. Moore referred to two recent Cochrane reviews. One review, published in January 2017, analyzed eight studies of oral antidiabetic therapies for GDM and concluded there was “insufficient high-quality evidence to be able to draw any meaningful conclusions as to the benefits of one oral antidiabetic pharmacological therapy over another” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 25;1:CD011967).

The other Cochrane review, published in November 2017, concluded that insulin and oral antidiabetic agents have similar effects on key health outcomes, and that each one has minimal harms. The quality of evidence, the authors said, ranged from “very low to moderate, with downgrading decisions due to imprecision, risk of bias, and inconsistency” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 5;11:CD012037).

Dr. Moore, professor of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of California, San Diego, cautioned against presuming that placental transfer of an antidiabetic drug is “ipso facto dangerous or terrible.” Moreover, he said that it’s not yet clear whether glyburide crosses the placenta in the first place.

Dr. Moore, Dr. Landon, and others at the meeting said they are eagerly awaiting long-term follow-up data from the Metformin in Gestational Diabetes (MiG) trial underway in Australia. The prospective randomized trial is designed to compare metformin with insulin and finished recruiting women in 2006. A recently published analysis found similar neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring at 2 years, but it’s the longer-term data looking into early puberty that experts now want to see (Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309602).

In the meantime, Dr. Landon said the “short-term safety record for oral antidiabetic medications is actually pretty good.” There are studies “suggesting an increased risk for large babies with glyburide, but these are very small RCTs [randomized controlled trials],” he said in an interview.

Data from population-based studies, moreover, are “flawed in as much as we don’t know the thresholds for initiating glyburide treatment, nor do we know whether the women were really good candidates for this therapy,” Dr. Landon said. “It’s conceivable, and it’s been my experience, that glyburide has been overprescribed and inappropriately prescribed in certain women with GDM who really should receive insulin therapy.”

Whether glyburide and metformin are being prescribed for GDM in optimal doses is another growing question – one that interests Steve N. Caritis, MD. The drugs are typically prescribed to be taken twice a day every 12 hours, but he said he is finding that some patients may need more frequent, individually tailored dosing.

“We may have come to conclusions in [the studies published thus far] that may not be the correct conclusions,” Dr. Caritis, who coleads obstetric pharmacology research at the Magee-Womens Research Institute in Pittsburgh, said at the DPSG meeting. “The question is, If the dosing were appropriate, would we have the same outcomes?”

“We were asked, Are people using [oral antidiabetic medications] properly? Could the fact that glyburide may not have had the efficacy we’d hoped for [in published studies] be due to it not being used properly?” Dr. Catalano said.

Individualizing drug choice

Dosing aside, there may be populations of women who respond poorly to a medication because of the underlying pathophysiology of their GDM, said Maisa N. Feghali, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh.

A study published in 2016 demonstrated the heterogeneity of the physiologic processes underlying hyperglycemia in 67 women with GDM. Almost one-third of women with GDM had predominant insulin secretion deficit, one-half had predominant insulin resistance, and the remaining 20% had a mixed “metabolic profile” (Diabetes Care. 2016 Jun;39[6]:1052-5).

This study prompted Dr. Feghali and her colleagues to design a pilot study aimed at testing an individualized approach that matches treatment to GDM mechanism. “We [currently] have the expectation that all glucose-lowering agents will be similarly effective despite significant variation in underlying GDM pathophysiology,” she said during a presentation at the DPSG meeting. “But I think we have a mismatch between variations in GDM and the uniformity of treatment.”

In her pilot study, women diagnosed with GDM who fail dietary control will be randomized into usual treatment or matched treatment (metformin for predominant insulin resistance, glyburide or insulin for predominant insulin secretion defects, and one of the three for combined insulin resistance and insulin secretion defects).

The MATCh-GDM study (Metabolic Analysis for Treatment Choice of GDM) is just getting underway. Patients will be monitored for consistency of GDM mechanism and glucose control, and routine clinical variables (hypertensive diseases, cesarean delivery, and birth weight) will be studied, as well as neonatal body composition, cord blood glucose, and cord blood C-peptide.

WASHINGTON – The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ conclusion that insulin should be considered the first-line pharmacologic treatment for gestational diabetes came under fire at a recent meeting on diabetes in pregnancy, indicating the extent to which controversy persists over the use of oral antidiabetic medications in pregnancy.

“Like many others, I’m perplexed by the strong endorsement,” Mark Landon, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Ohio State University, Columbus, said during an open discussion of oral hypoglycemic agents held at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

Dr. Landon and several other researchers and experts in diabetes in pregnancy expressed discontent with any firm prioritization of the drugs most commonly used for gestational diabetes, saying that there are not yet enough data to do so.

The endorsement of insulin as the first-line option when pharmacologic treatment is needed is a level A conclusion/recommendation in ACOG’s updated practice bulletin on gestational diabetes mellitus, released in July 2017 (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130[1]:e17-37). In accompanying level B recommendations, ACOG stated that in women who decline insulin therapy or who are believed to be “unable to safely administer insulin,” metformin is a “reasonable second-line choice.” Glyburide “should not be recommended as a first-line pharmacologic treatment because, in most studies, it does not yield equivalent outcomes to insulin.”

Level A recommendations are defined as “based on good and consistent scientific evidence,” while the evidence for level B recommendations is “limited or inconsistent.”

Asked to comment on the concerns voiced at the meeting, an ACOG spokeswoman said that the recommendations were developed after a thorough literature review, but that the evidence was being reexamined with the option of updating the practice bulletin.

Current recommendations

In its practice bulletin, ACOG noted that oral antidiabetic medications, such as glyburide and metformin, are increasingly used among women with GDM, despite not being approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication and even though insulin continues to be the recommended as first-line therapy by the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

The ADA, in a summary of its 2017 guideline on the management of diabetes in pregnancy, stated that insulin is the “preferred medication for treating hyperglycemia in gestational diabetes mellitus, as it does not cross the placenta to a measurable extent.” Metformin and glyburide are options, “but both cross the placenta to the fetus, with metformin likely crossing to a greater extent than glyburide” (Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40[Suppl 1]:S114- 9).Regarding metformin, the ACOG bulletin cited two trials that randomized women to metformin or insulin – one in which both groups experienced similar rates of a composite outcome of perinatal morbidity, and another in which women receiving metformin had lower mean glucose levels, less gestational weight gain, and neonates with lower rates of hypoglycemia.

ACOG also cited a meta-analysis, that found “minimal differences” between neonates of women randomized to metformin versus insulin, but also noted that “interestingly, women randomized to metformin experienced a higher rate of preterm birth” and a lower rate of gestational hypertension (BMJ. 2015;350:h102).

With respect to glyburide, the ACOG bulletin said that two recent meta-analyses had demonstrated worse neonatal outcomes with glyburide, compared with insulin, and that observational studies have shown higher rates of preeclampsia, hyperbilirubinemia, and stillbirth with the use of glyburide, compared with insulin. However, many other outcomes have not been statistically significantly different, according to the practice bulletin.

Additionally, at least 4%-16% of women eventually require the addition of insulin when glyburide is used as initial treatment, as do 26%-46% of women who take metformin, according to ACOG.

Regarding placental transfer, ACOG’s bulletin said that while one study that analyzed umbilical cord blood revealed no detectable glyburide in exposed pregnancies, another study demonstrated that glyburide does cross the placenta. Metformin has also been found to cross the placenta, with the fetus exposed to concentrations similar to maternal levels, the bulletin noted.

“Although current data demonstrate no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal health from oral diabetic therapy during pregnancy, long-term outcomes are not yet available,” ACOG wrote in the practice bulletin.

Concerns about research

As Thomas Moore, MD, sees it, the quality of available data is insufficient to recommend insulin over oral agents, or one oral agent over another. “We really need to focus [the National Institutes of Health] on putting together proper studies,” he said at the meeting.

In a later interview, Dr. Moore referred to two recent Cochrane reviews. One review, published in January 2017, analyzed eight studies of oral antidiabetic therapies for GDM and concluded there was “insufficient high-quality evidence to be able to draw any meaningful conclusions as to the benefits of one oral antidiabetic pharmacological therapy over another” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 25;1:CD011967).

The other Cochrane review, published in November 2017, concluded that insulin and oral antidiabetic agents have similar effects on key health outcomes, and that each one has minimal harms. The quality of evidence, the authors said, ranged from “very low to moderate, with downgrading decisions due to imprecision, risk of bias, and inconsistency” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 5;11:CD012037).

Dr. Moore, professor of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of California, San Diego, cautioned against presuming that placental transfer of an antidiabetic drug is “ipso facto dangerous or terrible.” Moreover, he said that it’s not yet clear whether glyburide crosses the placenta in the first place.

Dr. Moore, Dr. Landon, and others at the meeting said they are eagerly awaiting long-term follow-up data from the Metformin in Gestational Diabetes (MiG) trial underway in Australia. The prospective randomized trial is designed to compare metformin with insulin and finished recruiting women in 2006. A recently published analysis found similar neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring at 2 years, but it’s the longer-term data looking into early puberty that experts now want to see (Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309602).

In the meantime, Dr. Landon said the “short-term safety record for oral antidiabetic medications is actually pretty good.” There are studies “suggesting an increased risk for large babies with glyburide, but these are very small RCTs [randomized controlled trials],” he said in an interview.

Data from population-based studies, moreover, are “flawed in as much as we don’t know the thresholds for initiating glyburide treatment, nor do we know whether the women were really good candidates for this therapy,” Dr. Landon said. “It’s conceivable, and it’s been my experience, that glyburide has been overprescribed and inappropriately prescribed in certain women with GDM who really should receive insulin therapy.”

Whether glyburide and metformin are being prescribed for GDM in optimal doses is another growing question – one that interests Steve N. Caritis, MD. The drugs are typically prescribed to be taken twice a day every 12 hours, but he said he is finding that some patients may need more frequent, individually tailored dosing.

“We may have come to conclusions in [the studies published thus far] that may not be the correct conclusions,” Dr. Caritis, who coleads obstetric pharmacology research at the Magee-Womens Research Institute in Pittsburgh, said at the DPSG meeting. “The question is, If the dosing were appropriate, would we have the same outcomes?”

“We were asked, Are people using [oral antidiabetic medications] properly? Could the fact that glyburide may not have had the efficacy we’d hoped for [in published studies] be due to it not being used properly?” Dr. Catalano said.

Individualizing drug choice

Dosing aside, there may be populations of women who respond poorly to a medication because of the underlying pathophysiology of their GDM, said Maisa N. Feghali, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh.

A study published in 2016 demonstrated the heterogeneity of the physiologic processes underlying hyperglycemia in 67 women with GDM. Almost one-third of women with GDM had predominant insulin secretion deficit, one-half had predominant insulin resistance, and the remaining 20% had a mixed “metabolic profile” (Diabetes Care. 2016 Jun;39[6]:1052-5).

This study prompted Dr. Feghali and her colleagues to design a pilot study aimed at testing an individualized approach that matches treatment to GDM mechanism. “We [currently] have the expectation that all glucose-lowering agents will be similarly effective despite significant variation in underlying GDM pathophysiology,” she said during a presentation at the DPSG meeting. “But I think we have a mismatch between variations in GDM and the uniformity of treatment.”

In her pilot study, women diagnosed with GDM who fail dietary control will be randomized into usual treatment or matched treatment (metformin for predominant insulin resistance, glyburide or insulin for predominant insulin secretion defects, and one of the three for combined insulin resistance and insulin secretion defects).

The MATCh-GDM study (Metabolic Analysis for Treatment Choice of GDM) is just getting underway. Patients will be monitored for consistency of GDM mechanism and glucose control, and routine clinical variables (hypertensive diseases, cesarean delivery, and birth weight) will be studied, as well as neonatal body composition, cord blood glucose, and cord blood C-peptide.

WASHINGTON – The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ conclusion that insulin should be considered the first-line pharmacologic treatment for gestational diabetes came under fire at a recent meeting on diabetes in pregnancy, indicating the extent to which controversy persists over the use of oral antidiabetic medications in pregnancy.

“Like many others, I’m perplexed by the strong endorsement,” Mark Landon, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Ohio State University, Columbus, said during an open discussion of oral hypoglycemic agents held at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

Dr. Landon and several other researchers and experts in diabetes in pregnancy expressed discontent with any firm prioritization of the drugs most commonly used for gestational diabetes, saying that there are not yet enough data to do so.

The endorsement of insulin as the first-line option when pharmacologic treatment is needed is a level A conclusion/recommendation in ACOG’s updated practice bulletin on gestational diabetes mellitus, released in July 2017 (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130[1]:e17-37). In accompanying level B recommendations, ACOG stated that in women who decline insulin therapy or who are believed to be “unable to safely administer insulin,” metformin is a “reasonable second-line choice.” Glyburide “should not be recommended as a first-line pharmacologic treatment because, in most studies, it does not yield equivalent outcomes to insulin.”

Level A recommendations are defined as “based on good and consistent scientific evidence,” while the evidence for level B recommendations is “limited or inconsistent.”

Asked to comment on the concerns voiced at the meeting, an ACOG spokeswoman said that the recommendations were developed after a thorough literature review, but that the evidence was being reexamined with the option of updating the practice bulletin.

Current recommendations

In its practice bulletin, ACOG noted that oral antidiabetic medications, such as glyburide and metformin, are increasingly used among women with GDM, despite not being approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication and even though insulin continues to be the recommended as first-line therapy by the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

The ADA, in a summary of its 2017 guideline on the management of diabetes in pregnancy, stated that insulin is the “preferred medication for treating hyperglycemia in gestational diabetes mellitus, as it does not cross the placenta to a measurable extent.” Metformin and glyburide are options, “but both cross the placenta to the fetus, with metformin likely crossing to a greater extent than glyburide” (Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40[Suppl 1]:S114- 9).Regarding metformin, the ACOG bulletin cited two trials that randomized women to metformin or insulin – one in which both groups experienced similar rates of a composite outcome of perinatal morbidity, and another in which women receiving metformin had lower mean glucose levels, less gestational weight gain, and neonates with lower rates of hypoglycemia.

ACOG also cited a meta-analysis, that found “minimal differences” between neonates of women randomized to metformin versus insulin, but also noted that “interestingly, women randomized to metformin experienced a higher rate of preterm birth” and a lower rate of gestational hypertension (BMJ. 2015;350:h102).

With respect to glyburide, the ACOG bulletin said that two recent meta-analyses had demonstrated worse neonatal outcomes with glyburide, compared with insulin, and that observational studies have shown higher rates of preeclampsia, hyperbilirubinemia, and stillbirth with the use of glyburide, compared with insulin. However, many other outcomes have not been statistically significantly different, according to the practice bulletin.

Additionally, at least 4%-16% of women eventually require the addition of insulin when glyburide is used as initial treatment, as do 26%-46% of women who take metformin, according to ACOG.

Regarding placental transfer, ACOG’s bulletin said that while one study that analyzed umbilical cord blood revealed no detectable glyburide in exposed pregnancies, another study demonstrated that glyburide does cross the placenta. Metformin has also been found to cross the placenta, with the fetus exposed to concentrations similar to maternal levels, the bulletin noted.

“Although current data demonstrate no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal health from oral diabetic therapy during pregnancy, long-term outcomes are not yet available,” ACOG wrote in the practice bulletin.

Concerns about research