User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

New PAD guidelines expected to boost awareness and treatment

NEW ORLEANS – The latest revision of U.S. guidelines for diagnosing and managing lower-extremity peripheral artery disease is seen by several experts as primarily a renewed call to action by American physicians to more diligently identify at-risk people in their practices, diagnose the disease with ankle-brachial index measurement, and appropriately treat patients who have the disease.

The new lower-extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) guidelines “give us a platform to get something done,” said Heather L. Gornik, MD, vice chair of the guidelines panel and medical director of the noninvasive vascular lab at the Cleveland Clinic. Improved PAD identification and care “starts with the fundamentals of recognizing who is at risk for PAD and then doing some clinical investigation to find it, because it’s there. You just need to ask patients if they have leg symptoms, have them take off their socks and examine their feet,” Dr. Gornik said in an interview following a program devoted to the revised guidelines at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The new guidelines are “a clarion call to action,” commented Alan T. Hirsch, MD, professor of medicine, epidemiology, and community health and director of the vascular medicine program at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. PAD “is the single most morbid and fatal of all cardiovascular diseases, so why in 2016 are we challenged to have every cardiologist trained in basic PAD competency?” asked Dr. Hirsch, who chaired the 2005 guidelines panel.

The AHA wants to “elevate awareness of PAD among the public and health professionals, and we want to better understand how we can be a catalyst for change,” said Terri Wiggins, the organization’s vice president for vascular health programs. AHA publications now stress that clinicians need to have patients “take off their socks and look at the patient’s feet,” she said.

The problem with the way many U.S. physicians handle PAD goes beyond a failure to properly screen and diagnose the disease. Analysis of data collected by the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey during 2006-2013 showed that, among an average of 3.9 million patients seen each year with PAD, just 38% received treatment with an antiplatelet drug, 35% received a statin, and among those patients who smoked, 36% received counseling for smoking cessation, Jeffrey S. Berger, MD, reported in a separate talk at the meeting. These rates were roughly constant throughout the 8-year period he examined.

“These data are eye-opening. They highlight a clear opportunity to improve the care of patients with PAD with guideline-directed therapy. PAD is problematic because only 10%-15% of patients have typical symptoms, so many physicians have a false perception that these patients are not at high risk,” Dr. Berger said in an interview. “What the AHA is doing is great” for raising awareness, he added.

The revised 2016 PAD guidelines made several changes, compared with what had been on the books from the 2005 guidelines and 2011 update, including classifying vorapaxar (Zontivity) treatment a class IIb recommendation with “uncertain” incremental benefit when used as an add-on agent on top of standard antiplatelet therapy, endorsement of annual influenza vaccination as something every PAD patient should receive and a class I recommendation, and acknowledgment that selected patients with critical limb ischemia are candidates for an “endovascular first” approach to revascularization,

Perhaps just as important was inclusion for the first time in the new guidelines of three advocacy priorities for initiatives by various professional societies with an interest in PAD: easy availability of ankle-brachial index measurement as the initial test to establish a diagnosis of PAD in patients with physical examination findings suggestive of the disease; access to supervised exercise programs for patients diagnosed with PAD; and incorporation of patient-centered outcomes into the regulatory approval process of new medical therapies and revascularization technologies for treating PAD.

The new guidelines “ form the basis for the AHA establishing a Get With The Guidelines program for PAD so that clinicians can be held accountable for delivering these treatments,” said Naomi M. Hamburg, MD, chief of vascular biology at Boston University and a member of the guidelines panel.

Dr. Gornik has an ownership interest in Summit Doppler Systems and Zin Medical and has received research support from AstraZeneca and Theravasc. Dr. Hamburg has been a consultant to Acceleron and has received research support from Everest Genomics, Hershey’s, Unex, and Welch’s. Dr. Hirsch, Ms. Wiggins, and Dr. Berger had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NEW ORLEANS – The latest revision of U.S. guidelines for diagnosing and managing lower-extremity peripheral artery disease is seen by several experts as primarily a renewed call to action by American physicians to more diligently identify at-risk people in their practices, diagnose the disease with ankle-brachial index measurement, and appropriately treat patients who have the disease.

The new lower-extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) guidelines “give us a platform to get something done,” said Heather L. Gornik, MD, vice chair of the guidelines panel and medical director of the noninvasive vascular lab at the Cleveland Clinic. Improved PAD identification and care “starts with the fundamentals of recognizing who is at risk for PAD and then doing some clinical investigation to find it, because it’s there. You just need to ask patients if they have leg symptoms, have them take off their socks and examine their feet,” Dr. Gornik said in an interview following a program devoted to the revised guidelines at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The new guidelines are “a clarion call to action,” commented Alan T. Hirsch, MD, professor of medicine, epidemiology, and community health and director of the vascular medicine program at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. PAD “is the single most morbid and fatal of all cardiovascular diseases, so why in 2016 are we challenged to have every cardiologist trained in basic PAD competency?” asked Dr. Hirsch, who chaired the 2005 guidelines panel.

The AHA wants to “elevate awareness of PAD among the public and health professionals, and we want to better understand how we can be a catalyst for change,” said Terri Wiggins, the organization’s vice president for vascular health programs. AHA publications now stress that clinicians need to have patients “take off their socks and look at the patient’s feet,” she said.

The problem with the way many U.S. physicians handle PAD goes beyond a failure to properly screen and diagnose the disease. Analysis of data collected by the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey during 2006-2013 showed that, among an average of 3.9 million patients seen each year with PAD, just 38% received treatment with an antiplatelet drug, 35% received a statin, and among those patients who smoked, 36% received counseling for smoking cessation, Jeffrey S. Berger, MD, reported in a separate talk at the meeting. These rates were roughly constant throughout the 8-year period he examined.

“These data are eye-opening. They highlight a clear opportunity to improve the care of patients with PAD with guideline-directed therapy. PAD is problematic because only 10%-15% of patients have typical symptoms, so many physicians have a false perception that these patients are not at high risk,” Dr. Berger said in an interview. “What the AHA is doing is great” for raising awareness, he added.

The revised 2016 PAD guidelines made several changes, compared with what had been on the books from the 2005 guidelines and 2011 update, including classifying vorapaxar (Zontivity) treatment a class IIb recommendation with “uncertain” incremental benefit when used as an add-on agent on top of standard antiplatelet therapy, endorsement of annual influenza vaccination as something every PAD patient should receive and a class I recommendation, and acknowledgment that selected patients with critical limb ischemia are candidates for an “endovascular first” approach to revascularization,

Perhaps just as important was inclusion for the first time in the new guidelines of three advocacy priorities for initiatives by various professional societies with an interest in PAD: easy availability of ankle-brachial index measurement as the initial test to establish a diagnosis of PAD in patients with physical examination findings suggestive of the disease; access to supervised exercise programs for patients diagnosed with PAD; and incorporation of patient-centered outcomes into the regulatory approval process of new medical therapies and revascularization technologies for treating PAD.

The new guidelines “ form the basis for the AHA establishing a Get With The Guidelines program for PAD so that clinicians can be held accountable for delivering these treatments,” said Naomi M. Hamburg, MD, chief of vascular biology at Boston University and a member of the guidelines panel.

Dr. Gornik has an ownership interest in Summit Doppler Systems and Zin Medical and has received research support from AstraZeneca and Theravasc. Dr. Hamburg has been a consultant to Acceleron and has received research support from Everest Genomics, Hershey’s, Unex, and Welch’s. Dr. Hirsch, Ms. Wiggins, and Dr. Berger had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NEW ORLEANS – The latest revision of U.S. guidelines for diagnosing and managing lower-extremity peripheral artery disease is seen by several experts as primarily a renewed call to action by American physicians to more diligently identify at-risk people in their practices, diagnose the disease with ankle-brachial index measurement, and appropriately treat patients who have the disease.

The new lower-extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) guidelines “give us a platform to get something done,” said Heather L. Gornik, MD, vice chair of the guidelines panel and medical director of the noninvasive vascular lab at the Cleveland Clinic. Improved PAD identification and care “starts with the fundamentals of recognizing who is at risk for PAD and then doing some clinical investigation to find it, because it’s there. You just need to ask patients if they have leg symptoms, have them take off their socks and examine their feet,” Dr. Gornik said in an interview following a program devoted to the revised guidelines at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The new guidelines are “a clarion call to action,” commented Alan T. Hirsch, MD, professor of medicine, epidemiology, and community health and director of the vascular medicine program at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. PAD “is the single most morbid and fatal of all cardiovascular diseases, so why in 2016 are we challenged to have every cardiologist trained in basic PAD competency?” asked Dr. Hirsch, who chaired the 2005 guidelines panel.

The AHA wants to “elevate awareness of PAD among the public and health professionals, and we want to better understand how we can be a catalyst for change,” said Terri Wiggins, the organization’s vice president for vascular health programs. AHA publications now stress that clinicians need to have patients “take off their socks and look at the patient’s feet,” she said.

The problem with the way many U.S. physicians handle PAD goes beyond a failure to properly screen and diagnose the disease. Analysis of data collected by the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey during 2006-2013 showed that, among an average of 3.9 million patients seen each year with PAD, just 38% received treatment with an antiplatelet drug, 35% received a statin, and among those patients who smoked, 36% received counseling for smoking cessation, Jeffrey S. Berger, MD, reported in a separate talk at the meeting. These rates were roughly constant throughout the 8-year period he examined.

“These data are eye-opening. They highlight a clear opportunity to improve the care of patients with PAD with guideline-directed therapy. PAD is problematic because only 10%-15% of patients have typical symptoms, so many physicians have a false perception that these patients are not at high risk,” Dr. Berger said in an interview. “What the AHA is doing is great” for raising awareness, he added.

The revised 2016 PAD guidelines made several changes, compared with what had been on the books from the 2005 guidelines and 2011 update, including classifying vorapaxar (Zontivity) treatment a class IIb recommendation with “uncertain” incremental benefit when used as an add-on agent on top of standard antiplatelet therapy, endorsement of annual influenza vaccination as something every PAD patient should receive and a class I recommendation, and acknowledgment that selected patients with critical limb ischemia are candidates for an “endovascular first” approach to revascularization,

Perhaps just as important was inclusion for the first time in the new guidelines of three advocacy priorities for initiatives by various professional societies with an interest in PAD: easy availability of ankle-brachial index measurement as the initial test to establish a diagnosis of PAD in patients with physical examination findings suggestive of the disease; access to supervised exercise programs for patients diagnosed with PAD; and incorporation of patient-centered outcomes into the regulatory approval process of new medical therapies and revascularization technologies for treating PAD.

The new guidelines “ form the basis for the AHA establishing a Get With The Guidelines program for PAD so that clinicians can be held accountable for delivering these treatments,” said Naomi M. Hamburg, MD, chief of vascular biology at Boston University and a member of the guidelines panel.

Dr. Gornik has an ownership interest in Summit Doppler Systems and Zin Medical and has received research support from AstraZeneca and Theravasc. Dr. Hamburg has been a consultant to Acceleron and has received research support from Everest Genomics, Hershey’s, Unex, and Welch’s. Dr. Hirsch, Ms. Wiggins, and Dr. Berger had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Readmissions after bariatric surgery more common among black patients

WASHINGTON – Readmissions after bariatric surgery are significantly higher among black patients than among whites.

The reasons aren’t entirely clear, but since long-term morbidity and mortality are equivalent, they are probably more related to socioeconomics than clinical factors, Matthew Whealon, MD, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“I think they are multifactorial,” said Dr. Whealon of the University of California, Irvine. “Some of it may be related to comorbidities, but other factors could be socioeconomic status, insurance status, access to primary care and follow-up care, even home support systems and patient expectations after surgery. I think it’s incumbent upon us to try and identify some of these risk factors and address them before surgery to reduce this disparity in readmissions.”

Black patients undergoing Roux-en-Y bypass were significantly younger (43 vs. 45 years), and more often women (86% vs. 78%). They also had significantly higher body mass index than did white patients (48 vs. 46 kg/m2). More black individuals had a BMI of 50 kg/m2 or higher.

There were no significant differences in the severity of comorbidities. About 70% of each group had severe comorbidities as classified by the American Anesthesiologists Society risk assessment profile.

However, those comorbidities were different. Among black patients, steroid use, heart failure, hypertension, and end-stage renal disease were significantly more common. Among white patients, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bleeding disorders were more common.

There were no differences in 30-day mortality (less than 1% of each group); serious morbidity (3%) or any morbidity (5%); length of stay (2.4 days); or reoperation (2.6%).

However, readmissions were significantly more likely among black patients (8% vs. 5.6%). This translated to a 29% increased risk of readmission (OR 1.29).

Compared to whites, blacks who had a laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy were also significantly younger (42 vs. 45 years); more often women (87% vs. 76%); and heavier (BMI 47 vs. 45 kg/m2). Again, they were more likely to have a BMI of more than 50 kg/m2 (28% vs. 21%).

Significantly more were in the ASA class 3 of severe comorbidities (70% vs.66%). There were also differences in the comorbidities, with blacks more likely to have heart failure, hypertension, and end-stage renal disease, and whites more likely to have diabetes, smoking, dyspnea, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Among these patients, 30-day mortality was not different (less than 1%). Serious morbidity was also similar (about 2%), as was any morbidity (about 3%). The reoperation rate was the same (1.2%).

Length of stay was longer among black patients but this was not clinically significant, Dr. Whealon said: It still hovered right around 2 days.

But readmissions were significantly more common among blacks (5% vs. 3%). This difference translated to a 35% increased risk of readmission (odds ratio 1.35).

The nature of the NSQIP data makes it impossible to tease out any other factors that might have contributed to this finding. However, Dr. Whealon said, the equivalent findings on morbidity and mortality are very encouraging and represent a big improvement.

“We have done very well in driving down morbidity and mortality among these patients. Mortality rates are one tenth of what we were seeing a decade ago.”

This change hasn’t been well documented yet because many of the large studies showing racial and ethnic mortality disparities include data drawn from open bariatric surgery, which has been almost completely abandoned in favor of the much safer laparoscopic approaches.

Dr. Whealon had no financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

WASHINGTON – Readmissions after bariatric surgery are significantly higher among black patients than among whites.

The reasons aren’t entirely clear, but since long-term morbidity and mortality are equivalent, they are probably more related to socioeconomics than clinical factors, Matthew Whealon, MD, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“I think they are multifactorial,” said Dr. Whealon of the University of California, Irvine. “Some of it may be related to comorbidities, but other factors could be socioeconomic status, insurance status, access to primary care and follow-up care, even home support systems and patient expectations after surgery. I think it’s incumbent upon us to try and identify some of these risk factors and address them before surgery to reduce this disparity in readmissions.”

Black patients undergoing Roux-en-Y bypass were significantly younger (43 vs. 45 years), and more often women (86% vs. 78%). They also had significantly higher body mass index than did white patients (48 vs. 46 kg/m2). More black individuals had a BMI of 50 kg/m2 or higher.

There were no significant differences in the severity of comorbidities. About 70% of each group had severe comorbidities as classified by the American Anesthesiologists Society risk assessment profile.

However, those comorbidities were different. Among black patients, steroid use, heart failure, hypertension, and end-stage renal disease were significantly more common. Among white patients, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bleeding disorders were more common.

There were no differences in 30-day mortality (less than 1% of each group); serious morbidity (3%) or any morbidity (5%); length of stay (2.4 days); or reoperation (2.6%).

However, readmissions were significantly more likely among black patients (8% vs. 5.6%). This translated to a 29% increased risk of readmission (OR 1.29).

Compared to whites, blacks who had a laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy were also significantly younger (42 vs. 45 years); more often women (87% vs. 76%); and heavier (BMI 47 vs. 45 kg/m2). Again, they were more likely to have a BMI of more than 50 kg/m2 (28% vs. 21%).

Significantly more were in the ASA class 3 of severe comorbidities (70% vs.66%). There were also differences in the comorbidities, with blacks more likely to have heart failure, hypertension, and end-stage renal disease, and whites more likely to have diabetes, smoking, dyspnea, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Among these patients, 30-day mortality was not different (less than 1%). Serious morbidity was also similar (about 2%), as was any morbidity (about 3%). The reoperation rate was the same (1.2%).

Length of stay was longer among black patients but this was not clinically significant, Dr. Whealon said: It still hovered right around 2 days.

But readmissions were significantly more common among blacks (5% vs. 3%). This difference translated to a 35% increased risk of readmission (odds ratio 1.35).

The nature of the NSQIP data makes it impossible to tease out any other factors that might have contributed to this finding. However, Dr. Whealon said, the equivalent findings on morbidity and mortality are very encouraging and represent a big improvement.

“We have done very well in driving down morbidity and mortality among these patients. Mortality rates are one tenth of what we were seeing a decade ago.”

This change hasn’t been well documented yet because many of the large studies showing racial and ethnic mortality disparities include data drawn from open bariatric surgery, which has been almost completely abandoned in favor of the much safer laparoscopic approaches.

Dr. Whealon had no financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

WASHINGTON – Readmissions after bariatric surgery are significantly higher among black patients than among whites.

The reasons aren’t entirely clear, but since long-term morbidity and mortality are equivalent, they are probably more related to socioeconomics than clinical factors, Matthew Whealon, MD, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“I think they are multifactorial,” said Dr. Whealon of the University of California, Irvine. “Some of it may be related to comorbidities, but other factors could be socioeconomic status, insurance status, access to primary care and follow-up care, even home support systems and patient expectations after surgery. I think it’s incumbent upon us to try and identify some of these risk factors and address them before surgery to reduce this disparity in readmissions.”

Black patients undergoing Roux-en-Y bypass were significantly younger (43 vs. 45 years), and more often women (86% vs. 78%). They also had significantly higher body mass index than did white patients (48 vs. 46 kg/m2). More black individuals had a BMI of 50 kg/m2 or higher.

There were no significant differences in the severity of comorbidities. About 70% of each group had severe comorbidities as classified by the American Anesthesiologists Society risk assessment profile.

However, those comorbidities were different. Among black patients, steroid use, heart failure, hypertension, and end-stage renal disease were significantly more common. Among white patients, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bleeding disorders were more common.

There were no differences in 30-day mortality (less than 1% of each group); serious morbidity (3%) or any morbidity (5%); length of stay (2.4 days); or reoperation (2.6%).

However, readmissions were significantly more likely among black patients (8% vs. 5.6%). This translated to a 29% increased risk of readmission (OR 1.29).

Compared to whites, blacks who had a laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy were also significantly younger (42 vs. 45 years); more often women (87% vs. 76%); and heavier (BMI 47 vs. 45 kg/m2). Again, they were more likely to have a BMI of more than 50 kg/m2 (28% vs. 21%).

Significantly more were in the ASA class 3 of severe comorbidities (70% vs.66%). There were also differences in the comorbidities, with blacks more likely to have heart failure, hypertension, and end-stage renal disease, and whites more likely to have diabetes, smoking, dyspnea, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Among these patients, 30-day mortality was not different (less than 1%). Serious morbidity was also similar (about 2%), as was any morbidity (about 3%). The reoperation rate was the same (1.2%).

Length of stay was longer among black patients but this was not clinically significant, Dr. Whealon said: It still hovered right around 2 days.

But readmissions were significantly more common among blacks (5% vs. 3%). This difference translated to a 35% increased risk of readmission (odds ratio 1.35).

The nature of the NSQIP data makes it impossible to tease out any other factors that might have contributed to this finding. However, Dr. Whealon said, the equivalent findings on morbidity and mortality are very encouraging and represent a big improvement.

“We have done very well in driving down morbidity and mortality among these patients. Mortality rates are one tenth of what we were seeing a decade ago.”

This change hasn’t been well documented yet because many of the large studies showing racial and ethnic mortality disparities include data drawn from open bariatric surgery, which has been almost completely abandoned in favor of the much safer laparoscopic approaches.

Dr. Whealon had no financial disclosures.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Black patients were 29% more likely to be readmitted after Roux-en-Y and 35% more likely to be readmitted after sleeve gastrectomy.

Data source: The NSQIP database review comprised about 62,000 surgeries.

Disclosures: Dr. Whealon had no financial disclosures.

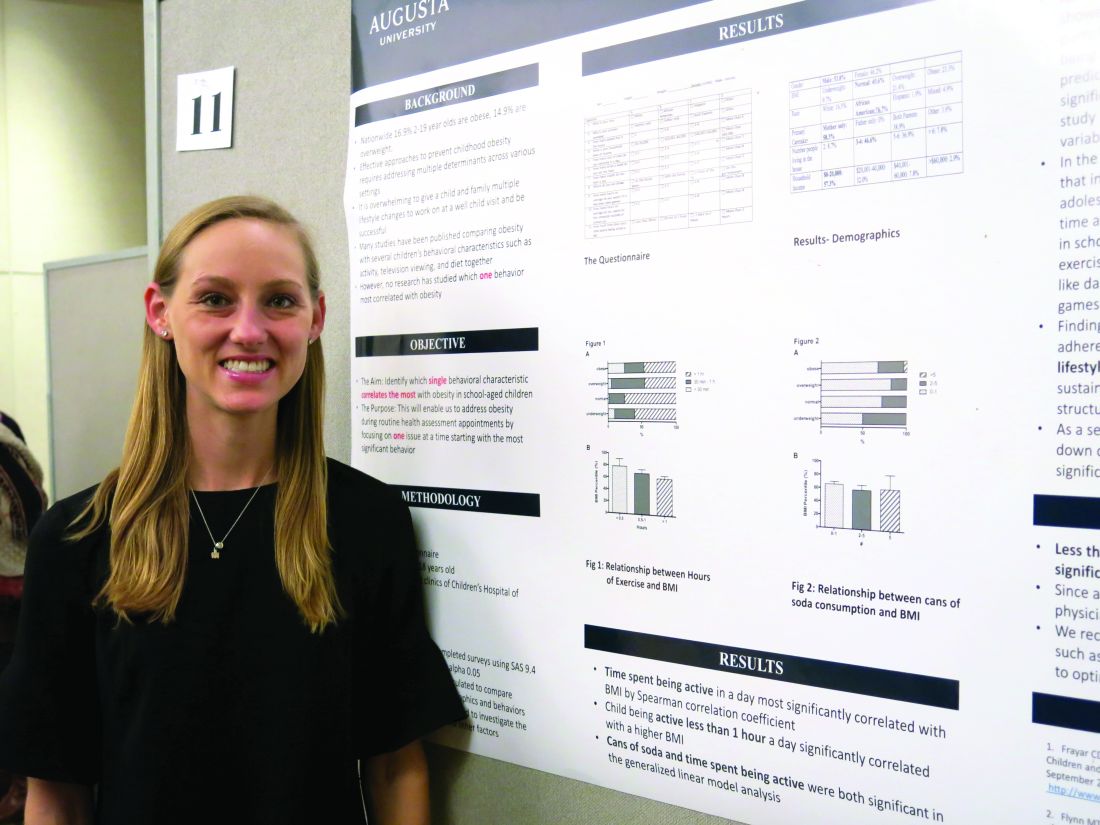

Obesity risk rises when kids aren’t active 1 hour a day

SAN FRANCISCO – The behavioral characteristic that correlated the most with obesity in school-age children was being active less than 1 hour per day, according to findings from a prospective study.

Meredith Johnston, DO, of Eau Claire Cooperative in Columbia, S.C., performed the study with Nirupma Sharma, MD, at Children’s Hospital of Georgia in Augusta. The prospective, questionnaire-based study was conducted with 103 children, aged 5-18 years, over a 6-month period. Dr. Johnston reported the results in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Giving a child one modifiable lifestyle factor to incorporate into their lifestyle instead of overwhelming them with multiple changes is more likely to produce significant change to prevent obesity,” Dr. Johnston said in an interview. “And finding an activity that the child enjoys will produce the best adherence and greatest long-term effects.”

Considering the findings of the study, “children should exercise 30 minutes to 1 hour a day to prevent childhood obesity,” she explained.

A recent review in the Annual Review of Public Health has shown a change in teen physical activity patterns due to an increase in screen time and a decrease in opportunities for physical activities at school and in the community. Giving patients tools for exercise such as dancing to YouTube videos or playing active video games might be a good idea, Dr. Johnston said.

Drinking more than five cans of soda in a day also was significantly associated with a higher BMI (P = .001). That lifestyle factor could be addressed at subsequent well-child visits.

Such efforts are critical, she noted, because an estimated 17% of 2- to 19-year-olds are obese, and 15% are overweight.

Dr. Johnston said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – The behavioral characteristic that correlated the most with obesity in school-age children was being active less than 1 hour per day, according to findings from a prospective study.

Meredith Johnston, DO, of Eau Claire Cooperative in Columbia, S.C., performed the study with Nirupma Sharma, MD, at Children’s Hospital of Georgia in Augusta. The prospective, questionnaire-based study was conducted with 103 children, aged 5-18 years, over a 6-month period. Dr. Johnston reported the results in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Giving a child one modifiable lifestyle factor to incorporate into their lifestyle instead of overwhelming them with multiple changes is more likely to produce significant change to prevent obesity,” Dr. Johnston said in an interview. “And finding an activity that the child enjoys will produce the best adherence and greatest long-term effects.”

Considering the findings of the study, “children should exercise 30 minutes to 1 hour a day to prevent childhood obesity,” she explained.

A recent review in the Annual Review of Public Health has shown a change in teen physical activity patterns due to an increase in screen time and a decrease in opportunities for physical activities at school and in the community. Giving patients tools for exercise such as dancing to YouTube videos or playing active video games might be a good idea, Dr. Johnston said.

Drinking more than five cans of soda in a day also was significantly associated with a higher BMI (P = .001). That lifestyle factor could be addressed at subsequent well-child visits.

Such efforts are critical, she noted, because an estimated 17% of 2- to 19-year-olds are obese, and 15% are overweight.

Dr. Johnston said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – The behavioral characteristic that correlated the most with obesity in school-age children was being active less than 1 hour per day, according to findings from a prospective study.

Meredith Johnston, DO, of Eau Claire Cooperative in Columbia, S.C., performed the study with Nirupma Sharma, MD, at Children’s Hospital of Georgia in Augusta. The prospective, questionnaire-based study was conducted with 103 children, aged 5-18 years, over a 6-month period. Dr. Johnston reported the results in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“Giving a child one modifiable lifestyle factor to incorporate into their lifestyle instead of overwhelming them with multiple changes is more likely to produce significant change to prevent obesity,” Dr. Johnston said in an interview. “And finding an activity that the child enjoys will produce the best adherence and greatest long-term effects.”

Considering the findings of the study, “children should exercise 30 minutes to 1 hour a day to prevent childhood obesity,” she explained.

A recent review in the Annual Review of Public Health has shown a change in teen physical activity patterns due to an increase in screen time and a decrease in opportunities for physical activities at school and in the community. Giving patients tools for exercise such as dancing to YouTube videos or playing active video games might be a good idea, Dr. Johnston said.

Drinking more than five cans of soda in a day also was significantly associated with a higher BMI (P = .001). That lifestyle factor could be addressed at subsequent well-child visits.

Such efforts are critical, she noted, because an estimated 17% of 2- to 19-year-olds are obese, and 15% are overweight.

Dr. Johnston said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AAP 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Being active less than 1 hour per day was significantly associated with a higher body mass index in children (P = .006 for 30 minutes to 1 hour, and P = .017 for less than 30 minutes).

Data source: A prospective, questionnaire-based study involving 103 children, aged 5-18 years, over a 6-month period.

Disclosures: Dr. Johnston said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Risk tool labels 59%-81% of adults as prediabetic

A Web-based risk test endorsed by the American Medical Association, the American Diabetes Association, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would label 59%-81% of adults as prediabetic if it were applied to the general U.S. population, according to a Research Letter to the Editor published online Oct. 3 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The test is intended to evaluate the risk for prediabetes of any adult patient, and it advises those it identifies as prediabetic to see their physicians for confirmatory blood glucose testing. But given the results of their study, labeling this many people as prediabetic constitutes overmedicalization and could have the unintended consequence of diluting access to health care for people who actually have type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions, said Saeid Shahraz, MD, PhD, of the Predictive Analytics and Comparative Effectiveness Center, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and his associates.

The investigators assessed how many people this test would classify as prediabetic by analyzing data for a nationally representative sample of 10,175 adults who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2013-2014. They extracted the same information from participant responses to the NHANES survey that is elicited by the Web-based test: age, sex, history of gestational diabetes, first-degree relatives with diabetes, hypertension, physical activity level, and weight.

Among Americans aged 40 years and older, this test would classify an estimated 73.3 million, or 58.7%, as prediabetic; among those aged 60 years and older, it would classify 80.8% as prediabetic. The test also would advise all those people to see their physicians and undergo blood glucose testing for confirmation, Dr. Shahraz and his associates said (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5919).

This would be “premature” for many reasons. Intensive lifestyle modifications are not known to be beneficial for such patients, even those who are found to have impaired glucose tolerance. And there is no direct evidence that preventing type 2 diabetes actually reduces the risk for diabetes-related complications. Moreover, the natural progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes is likely to be slow, which calls into question the need for any intervention, particularly for older patients likely to die from competing causes, the researchers noted.

“A valid method to examine for prediabetes should avoid unnecessary medicalization by labeling a disease predecessor as a medical condition and seek to concentrate on people at highest risk to allow for efficient distribution of limited health care resources,” they added.

A Web-based risk test endorsed by the American Medical Association, the American Diabetes Association, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would label 59%-81% of adults as prediabetic if it were applied to the general U.S. population, according to a Research Letter to the Editor published online Oct. 3 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The test is intended to evaluate the risk for prediabetes of any adult patient, and it advises those it identifies as prediabetic to see their physicians for confirmatory blood glucose testing. But given the results of their study, labeling this many people as prediabetic constitutes overmedicalization and could have the unintended consequence of diluting access to health care for people who actually have type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions, said Saeid Shahraz, MD, PhD, of the Predictive Analytics and Comparative Effectiveness Center, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and his associates.

The investigators assessed how many people this test would classify as prediabetic by analyzing data for a nationally representative sample of 10,175 adults who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2013-2014. They extracted the same information from participant responses to the NHANES survey that is elicited by the Web-based test: age, sex, history of gestational diabetes, first-degree relatives with diabetes, hypertension, physical activity level, and weight.

Among Americans aged 40 years and older, this test would classify an estimated 73.3 million, or 58.7%, as prediabetic; among those aged 60 years and older, it would classify 80.8% as prediabetic. The test also would advise all those people to see their physicians and undergo blood glucose testing for confirmation, Dr. Shahraz and his associates said (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5919).

This would be “premature” for many reasons. Intensive lifestyle modifications are not known to be beneficial for such patients, even those who are found to have impaired glucose tolerance. And there is no direct evidence that preventing type 2 diabetes actually reduces the risk for diabetes-related complications. Moreover, the natural progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes is likely to be slow, which calls into question the need for any intervention, particularly for older patients likely to die from competing causes, the researchers noted.

“A valid method to examine for prediabetes should avoid unnecessary medicalization by labeling a disease predecessor as a medical condition and seek to concentrate on people at highest risk to allow for efficient distribution of limited health care resources,” they added.

A Web-based risk test endorsed by the American Medical Association, the American Diabetes Association, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would label 59%-81% of adults as prediabetic if it were applied to the general U.S. population, according to a Research Letter to the Editor published online Oct. 3 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The test is intended to evaluate the risk for prediabetes of any adult patient, and it advises those it identifies as prediabetic to see their physicians for confirmatory blood glucose testing. But given the results of their study, labeling this many people as prediabetic constitutes overmedicalization and could have the unintended consequence of diluting access to health care for people who actually have type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions, said Saeid Shahraz, MD, PhD, of the Predictive Analytics and Comparative Effectiveness Center, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, and his associates.

The investigators assessed how many people this test would classify as prediabetic by analyzing data for a nationally representative sample of 10,175 adults who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2013-2014. They extracted the same information from participant responses to the NHANES survey that is elicited by the Web-based test: age, sex, history of gestational diabetes, first-degree relatives with diabetes, hypertension, physical activity level, and weight.

Among Americans aged 40 years and older, this test would classify an estimated 73.3 million, or 58.7%, as prediabetic; among those aged 60 years and older, it would classify 80.8% as prediabetic. The test also would advise all those people to see their physicians and undergo blood glucose testing for confirmation, Dr. Shahraz and his associates said (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5919).

This would be “premature” for many reasons. Intensive lifestyle modifications are not known to be beneficial for such patients, even those who are found to have impaired glucose tolerance. And there is no direct evidence that preventing type 2 diabetes actually reduces the risk for diabetes-related complications. Moreover, the natural progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes is likely to be slow, which calls into question the need for any intervention, particularly for older patients likely to die from competing causes, the researchers noted.

“A valid method to examine for prediabetes should avoid unnecessary medicalization by labeling a disease predecessor as a medical condition and seek to concentrate on people at highest risk to allow for efficient distribution of limited health care resources,” they added.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among Americans aged 40 years and older, this test would classify 58.7%, as prediabetic, and among those aged 60 years and older, it would classify 80.8% as prediabetic.

Data source: An analysis of NHANES data for 10,175 adults in 2013-2014.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Diseases and the National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. Dr. Shahraz and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Early menopause a risk factor for type 2 diabetes

“What we see in our data is that indeed, early onset of menopause is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes, and this association is independent of potential intermediate risk factors: obesity, insulin, glucose, inflammation, but also of estradiol and other endogenous sex hormone levels,” said Taulant Muka, MD, PhD, in an interview.

Dr. Muka, a postdoctoral fellow at Erasmus Medical College, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, presented the analysis from a large, prospective cohort of menopausal women at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

In an interview, Dr. Muka noted that the study investigated whether the association between early age at natural menopause (ANM) and type 2 diabetes is independent of intermediate risk factors for type 2 diabetes, such as obesity. Finally, the study also assessed whether endogenous sex hormone levels play a role in the link between early ANM and type 2 diabetes.

Enrollment in the Rotterdam study has been continuing in waves since the 1990s, with enrollment for participants in this particular study cohort occurring in 1997 and with additional cohorts enrolled in 2000-2001 and 2006-2008.

“I think this is the first prospective study with such long follow-up data and with a broad adjustment for confounding factors. Previous studies have been mainly cross-sectional, providing conflicting results,” said Dr. Muka.

Using self-reported age at menopause, the investigators excluded from the study women whose menopausal status was not known, who were actually not menopausal, or whose menopause had not occurred naturally. The study population also excluded women with prevalent type 2 diabetes or for whom no information about diabetes follow-up could be found.

The remaining 3,210 women who were included in the study had a median age of 67 years and had reached menopause at a median of 49.9 years. Most women (82.6%) had an ANM of 45-55 years; ANM for 8.8% was 40-44 years, while just 2.3% had an ANM of under 40 years. Mean body mass index was 27.1 kg/m2.

Participants were considered to have incident diabetes based on several sources: a general practitioner’s records, hospital discharge paperwork, or glucose measurements from visits during the Rotterdam study. Participants also were classified as having diabetes if they used a hypoglycemic medication or had a fasting blood glucose level of at least 7 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or, in the absence of a fasting blood glucose measurement, a nonfasting blood glucose of at least 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL).

Dr. Muka said he and his coinvestigators identified and adjusted for a large number of variables, using a series of three Cox proportion hazard models.

The first model adjusted for age, which wave of enrollment (cohort) participants were in, hormone therapy status, age at menarche, and the number of pregnancies that reached at least 6 months’ gestation.

The second model used all of the factors in model 1, and added BMI and glucose and insulin levels. The third model used all of the factors in model 2, and also added total cholesterol level, systolic blood pressure, the use of lipid-lowering or antihypertensive medications, alcohol and tobacco use, educational level, prevalent cardiovascular disease, and C-reactive protein levels.

The association of early ANM with the risk of type 2 diabetes was statistically significant in all three models (P less than .001), with very similar hazard ratios (HRs) in all models. For the third, the most comprehensive model, the HR was 1.42 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-2.45).

Extensive sensitivity analyses were carried out, and the association held independent of physical activity level, smoking status, use of hormone therapy, and age. The investigators also used multivariable analyses to ensure that the effect was not mediated by serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, dihydroepiandosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate, estradiol, testosterone, sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), or androstenedione.

This study was the first in this population to obtain and adjust for serum sex hormone and SHBG levels, said Dr. Muka.

The prospective design of the study and the long follow-up period were study strengths, said Dr. Muka. Additionally, blood glucose readings taken at study visits, together with electronically linked pharmacy dispensing records, were used for incident diabetes diagnoses.

Study limitations, Dr. Muka said, included the possibility of survival bias, since enrollees “may represent survivors of early menopause who did not develop [type 2 diabetes] or die prior to enrollment.” However, he said, this would mean that “we have underestimated the association, so the risk would be even higher.” Also, all study participants were white, so the results cannot be extrapolated to nonwhite populations.

Dr. Muka said that the largely American audience for his presentation was interested in the fact that the association existed independent of BMI, an obesity marker, based on questions and comments following the talk. “Indeed, we stratified the analysis, and we didn’t find any difference between participants who were obese and nonobese.” Also, he said that there were queries about whether the analyses had corrected for DEXA measurements, in order to assess lean versus fat body composition more accurately. This analysis has not been done, but Dr. Muka plans to complete it on his return to Rotterdam, he said.

Up to 10% of women will reach menopause before the age of 45, said Dr. Muka, so this analysis has the potential to impact primary care for millions of women. “Women who undergo early menopause may be a target for type 2 diabetes prevention measures and might need to be screened for other cardiovascular risk factors like high blood pressure and dyslipidemia, since they are also at risk for cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Muka reported no outside funding sources and had no relevant financial disclosures.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

“What we see in our data is that indeed, early onset of menopause is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes, and this association is independent of potential intermediate risk factors: obesity, insulin, glucose, inflammation, but also of estradiol and other endogenous sex hormone levels,” said Taulant Muka, MD, PhD, in an interview.

Dr. Muka, a postdoctoral fellow at Erasmus Medical College, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, presented the analysis from a large, prospective cohort of menopausal women at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

In an interview, Dr. Muka noted that the study investigated whether the association between early age at natural menopause (ANM) and type 2 diabetes is independent of intermediate risk factors for type 2 diabetes, such as obesity. Finally, the study also assessed whether endogenous sex hormone levels play a role in the link between early ANM and type 2 diabetes.

Enrollment in the Rotterdam study has been continuing in waves since the 1990s, with enrollment for participants in this particular study cohort occurring in 1997 and with additional cohorts enrolled in 2000-2001 and 2006-2008.

“I think this is the first prospective study with such long follow-up data and with a broad adjustment for confounding factors. Previous studies have been mainly cross-sectional, providing conflicting results,” said Dr. Muka.

Using self-reported age at menopause, the investigators excluded from the study women whose menopausal status was not known, who were actually not menopausal, or whose menopause had not occurred naturally. The study population also excluded women with prevalent type 2 diabetes or for whom no information about diabetes follow-up could be found.

The remaining 3,210 women who were included in the study had a median age of 67 years and had reached menopause at a median of 49.9 years. Most women (82.6%) had an ANM of 45-55 years; ANM for 8.8% was 40-44 years, while just 2.3% had an ANM of under 40 years. Mean body mass index was 27.1 kg/m2.

Participants were considered to have incident diabetes based on several sources: a general practitioner’s records, hospital discharge paperwork, or glucose measurements from visits during the Rotterdam study. Participants also were classified as having diabetes if they used a hypoglycemic medication or had a fasting blood glucose level of at least 7 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or, in the absence of a fasting blood glucose measurement, a nonfasting blood glucose of at least 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL).

Dr. Muka said he and his coinvestigators identified and adjusted for a large number of variables, using a series of three Cox proportion hazard models.

The first model adjusted for age, which wave of enrollment (cohort) participants were in, hormone therapy status, age at menarche, and the number of pregnancies that reached at least 6 months’ gestation.

The second model used all of the factors in model 1, and added BMI and glucose and insulin levels. The third model used all of the factors in model 2, and also added total cholesterol level, systolic blood pressure, the use of lipid-lowering or antihypertensive medications, alcohol and tobacco use, educational level, prevalent cardiovascular disease, and C-reactive protein levels.

The association of early ANM with the risk of type 2 diabetes was statistically significant in all three models (P less than .001), with very similar hazard ratios (HRs) in all models. For the third, the most comprehensive model, the HR was 1.42 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-2.45).

Extensive sensitivity analyses were carried out, and the association held independent of physical activity level, smoking status, use of hormone therapy, and age. The investigators also used multivariable analyses to ensure that the effect was not mediated by serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, dihydroepiandosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate, estradiol, testosterone, sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), or androstenedione.

This study was the first in this population to obtain and adjust for serum sex hormone and SHBG levels, said Dr. Muka.

The prospective design of the study and the long follow-up period were study strengths, said Dr. Muka. Additionally, blood glucose readings taken at study visits, together with electronically linked pharmacy dispensing records, were used for incident diabetes diagnoses.

Study limitations, Dr. Muka said, included the possibility of survival bias, since enrollees “may represent survivors of early menopause who did not develop [type 2 diabetes] or die prior to enrollment.” However, he said, this would mean that “we have underestimated the association, so the risk would be even higher.” Also, all study participants were white, so the results cannot be extrapolated to nonwhite populations.

Dr. Muka said that the largely American audience for his presentation was interested in the fact that the association existed independent of BMI, an obesity marker, based on questions and comments following the talk. “Indeed, we stratified the analysis, and we didn’t find any difference between participants who were obese and nonobese.” Also, he said that there were queries about whether the analyses had corrected for DEXA measurements, in order to assess lean versus fat body composition more accurately. This analysis has not been done, but Dr. Muka plans to complete it on his return to Rotterdam, he said.

Up to 10% of women will reach menopause before the age of 45, said Dr. Muka, so this analysis has the potential to impact primary care for millions of women. “Women who undergo early menopause may be a target for type 2 diabetes prevention measures and might need to be screened for other cardiovascular risk factors like high blood pressure and dyslipidemia, since they are also at risk for cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Muka reported no outside funding sources and had no relevant financial disclosures.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

“What we see in our data is that indeed, early onset of menopause is associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes, and this association is independent of potential intermediate risk factors: obesity, insulin, glucose, inflammation, but also of estradiol and other endogenous sex hormone levels,” said Taulant Muka, MD, PhD, in an interview.

Dr. Muka, a postdoctoral fellow at Erasmus Medical College, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, presented the analysis from a large, prospective cohort of menopausal women at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

In an interview, Dr. Muka noted that the study investigated whether the association between early age at natural menopause (ANM) and type 2 diabetes is independent of intermediate risk factors for type 2 diabetes, such as obesity. Finally, the study also assessed whether endogenous sex hormone levels play a role in the link between early ANM and type 2 diabetes.

Enrollment in the Rotterdam study has been continuing in waves since the 1990s, with enrollment for participants in this particular study cohort occurring in 1997 and with additional cohorts enrolled in 2000-2001 and 2006-2008.

“I think this is the first prospective study with such long follow-up data and with a broad adjustment for confounding factors. Previous studies have been mainly cross-sectional, providing conflicting results,” said Dr. Muka.

Using self-reported age at menopause, the investigators excluded from the study women whose menopausal status was not known, who were actually not menopausal, or whose menopause had not occurred naturally. The study population also excluded women with prevalent type 2 diabetes or for whom no information about diabetes follow-up could be found.

The remaining 3,210 women who were included in the study had a median age of 67 years and had reached menopause at a median of 49.9 years. Most women (82.6%) had an ANM of 45-55 years; ANM for 8.8% was 40-44 years, while just 2.3% had an ANM of under 40 years. Mean body mass index was 27.1 kg/m2.

Participants were considered to have incident diabetes based on several sources: a general practitioner’s records, hospital discharge paperwork, or glucose measurements from visits during the Rotterdam study. Participants also were classified as having diabetes if they used a hypoglycemic medication or had a fasting blood glucose level of at least 7 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or, in the absence of a fasting blood glucose measurement, a nonfasting blood glucose of at least 11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL).

Dr. Muka said he and his coinvestigators identified and adjusted for a large number of variables, using a series of three Cox proportion hazard models.

The first model adjusted for age, which wave of enrollment (cohort) participants were in, hormone therapy status, age at menarche, and the number of pregnancies that reached at least 6 months’ gestation.

The second model used all of the factors in model 1, and added BMI and glucose and insulin levels. The third model used all of the factors in model 2, and also added total cholesterol level, systolic blood pressure, the use of lipid-lowering or antihypertensive medications, alcohol and tobacco use, educational level, prevalent cardiovascular disease, and C-reactive protein levels.

The association of early ANM with the risk of type 2 diabetes was statistically significant in all three models (P less than .001), with very similar hazard ratios (HRs) in all models. For the third, the most comprehensive model, the HR was 1.42 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-2.45).

Extensive sensitivity analyses were carried out, and the association held independent of physical activity level, smoking status, use of hormone therapy, and age. The investigators also used multivariable analyses to ensure that the effect was not mediated by serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, dihydroepiandosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate, estradiol, testosterone, sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), or androstenedione.

This study was the first in this population to obtain and adjust for serum sex hormone and SHBG levels, said Dr. Muka.

The prospective design of the study and the long follow-up period were study strengths, said Dr. Muka. Additionally, blood glucose readings taken at study visits, together with electronically linked pharmacy dispensing records, were used for incident diabetes diagnoses.

Study limitations, Dr. Muka said, included the possibility of survival bias, since enrollees “may represent survivors of early menopause who did not develop [type 2 diabetes] or die prior to enrollment.” However, he said, this would mean that “we have underestimated the association, so the risk would be even higher.” Also, all study participants were white, so the results cannot be extrapolated to nonwhite populations.

Dr. Muka said that the largely American audience for his presentation was interested in the fact that the association existed independent of BMI, an obesity marker, based on questions and comments following the talk. “Indeed, we stratified the analysis, and we didn’t find any difference between participants who were obese and nonobese.” Also, he said that there were queries about whether the analyses had corrected for DEXA measurements, in order to assess lean versus fat body composition more accurately. This analysis has not been done, but Dr. Muka plans to complete it on his return to Rotterdam, he said.

Up to 10% of women will reach menopause before the age of 45, said Dr. Muka, so this analysis has the potential to impact primary care for millions of women. “Women who undergo early menopause may be a target for type 2 diabetes prevention measures and might need to be screened for other cardiovascular risk factors like high blood pressure and dyslipidemia, since they are also at risk for cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Muka reported no outside funding sources and had no relevant financial disclosures.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

Key clinical point: Early menopause is associated with an increased risk for type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: Age at menopause between 40 and 45 was associated with a relative risk of 1.49 for type 2 diabetes.

Data source: A prospective cohort study of an initial cohort of 3,210 menopausal women.

Disclosures: No outside funding source was reported. Dr. Muka reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Type 2 diabetes in youth needs new treatment options

NEW ORLEANS – For adolescents and children with type 2 diabetes, there aren’t a lot of therapeutic options other than insulin and metformin. And the situation isn’t likely to change without extraordinary collaboration, Kristen J. Nadeau, MD, research director of the department of pediatric endocrinology at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Colorado Springs, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Type 2 diabetes in youth appears to differ not only from pediatric type 1 diabetes, but also from adult type 2 diabetes, and current treatment options are limited,” Dr. Nadeau said. The estimated number of type 2 diabetes cases in the United States per year stands at 1,469,000 cases (12.3 per 100) in adults, compared with 5,100 (0.5 per 100) in youth. In adults there is a slight male predominance, whereas in kids girls are almost twice as likely as boys to be affected. Moreover, beta cell function declines faster in youth with type 2 diabetes.

The majority of insulins used by adults with type 2 diabetes are also approved for use in children and adolescents, but the only non-insulin medication approved for youth is metformin. According to Dr. Nadeau, 11 clinical safety and efficacy studies and 3 pharmacokinetic studies are ongoing for four DPP-4 inhibitors, two GLP-1 analogs, three SGLT2 inhibitors, colesevelam, bromocriptine, and insulins. A total of 5,000 youth are needed to complete current and planned trials, which “would require 100% participation from every child diagnosed in the next year, which is not feasible,” she said.

The required safety and efficacy studies are too difficult “because of the combination of unique challenges of the target population, study design concerns, and a lack of collaboration between agencies,” Dr. Nadeau said during a session that focused on the conclusions of the American Diabetes Association’s consensus conference on youth with type 2 diabetes, which took place on Oct. 20, 2015 in Alexandria, Va.

The consensus report was published online in Diabetes Care, and addresses the current status of type 2 diabetes in youth, the challenges of treatment, and priorities for research. Dr. Nadeau co-chaired the effort along with Dr. Philip Zeitler, section head of pediatric endocrinology at Children’s Hospital Colorado and medical director of the Children’s Hospital Colorado Clinical and Translational Research Center, Denver. Collaborators included the American Academy of Pediatrics, the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, and the Pediatric Endocrine Society.

One example of the research challenges is evident in data from the Today trial, which found that only about 39% of kids with type 2 diabetes live with both parents (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jan; 96[1]:159-67). “Whenever you have only one parent in the home, there are difficulties with transportation by definition, so it’s a lot harder for these kids to participate in studies,” Dr. Nadeau said. “In addition, only 17% of their parents had a college or advanced education and 41% had a household income of less than $25,000 per year.”

The social environment is critical, she continued, because the lifestyle factors associated with type 2 diabetes often result in poor outcomes. “It’s very hard to make lifestyle changes if there is a socioeconomic challenge,” she said. “We can’t make change without understanding the community and culture that these youth live in. It’s also critical that we have participation of minorities and other research participants with diverse backgrounds in order for [clinical] trials to be effective for the population that this disease is affecting.”

Another issue keeping drug trials of youth with type 2 diabetes from being completed is the entry criteria. Some studies require youth to be drug naive and have a hemoglobin A1c greater than 7%. “This is difficult, because many youth that are referred to our diabetes center already come in on metformin, leaving only about 7% of subjects available for this criteria,” Dr. Nadeau explained. Another common study entry criterion is being on metformin and having a hemoglobin A1c of about 7%, “so basically being a metformin failure,” she said. “This is difficult to meet because metformin is relatively effective in the early stages of diabetes.”

“We need clear strategies for research, prevention, and treatment. Clarifying unique pathophysiology, complications, and psychosocial impact will enable industry, academia, funding agencies, advocacy groups, and regulators to collectively evaluate the best approaches to research, treatment, and prevention,” Dr. Nadeau said.

The consensus conference participants recommended the following objectives: clarify the biology of type 2 diabetes in youth, obtain new pediatric information on drugs, encourage the use of appropriate medications, and inform clinical decision-making. “We have a desperate need to understand the actions of drugs in type 2 diabetes youth,” Dr. Nadeau said. “Our current approach is not working. Potential solutions include considering efficacy outcomes besides A1c, potentially looking at improvement in insulin sensitivity, preservation of beta-cell function, trying to prevent the A1c increase instead of looking for an A1c reduction, and trying to extrapolate from effects in adults, if we can understand enough to do that.”

The conference participants also called for infrastructure changes, such as creating a resource for patients with type 2 diabetes in the model of the Type 1 Diabetes Exchange. “We need to have collaborations internationally,” she said. “We also need support for teams and clinical groups to work together to be able to accomplish these collaboratively.”

Dr. Nadeau reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – For adolescents and children with type 2 diabetes, there aren’t a lot of therapeutic options other than insulin and metformin. And the situation isn’t likely to change without extraordinary collaboration, Kristen J. Nadeau, MD, research director of the department of pediatric endocrinology at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Colorado Springs, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Type 2 diabetes in youth appears to differ not only from pediatric type 1 diabetes, but also from adult type 2 diabetes, and current treatment options are limited,” Dr. Nadeau said. The estimated number of type 2 diabetes cases in the United States per year stands at 1,469,000 cases (12.3 per 100) in adults, compared with 5,100 (0.5 per 100) in youth. In adults there is a slight male predominance, whereas in kids girls are almost twice as likely as boys to be affected. Moreover, beta cell function declines faster in youth with type 2 diabetes.

The majority of insulins used by adults with type 2 diabetes are also approved for use in children and adolescents, but the only non-insulin medication approved for youth is metformin. According to Dr. Nadeau, 11 clinical safety and efficacy studies and 3 pharmacokinetic studies are ongoing for four DPP-4 inhibitors, two GLP-1 analogs, three SGLT2 inhibitors, colesevelam, bromocriptine, and insulins. A total of 5,000 youth are needed to complete current and planned trials, which “would require 100% participation from every child diagnosed in the next year, which is not feasible,” she said.

The required safety and efficacy studies are too difficult “because of the combination of unique challenges of the target population, study design concerns, and a lack of collaboration between agencies,” Dr. Nadeau said during a session that focused on the conclusions of the American Diabetes Association’s consensus conference on youth with type 2 diabetes, which took place on Oct. 20, 2015 in Alexandria, Va.

The consensus report was published online in Diabetes Care, and addresses the current status of type 2 diabetes in youth, the challenges of treatment, and priorities for research. Dr. Nadeau co-chaired the effort along with Dr. Philip Zeitler, section head of pediatric endocrinology at Children’s Hospital Colorado and medical director of the Children’s Hospital Colorado Clinical and Translational Research Center, Denver. Collaborators included the American Academy of Pediatrics, the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, and the Pediatric Endocrine Society.

One example of the research challenges is evident in data from the Today trial, which found that only about 39% of kids with type 2 diabetes live with both parents (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jan; 96[1]:159-67). “Whenever you have only one parent in the home, there are difficulties with transportation by definition, so it’s a lot harder for these kids to participate in studies,” Dr. Nadeau said. “In addition, only 17% of their parents had a college or advanced education and 41% had a household income of less than $25,000 per year.”

The social environment is critical, she continued, because the lifestyle factors associated with type 2 diabetes often result in poor outcomes. “It’s very hard to make lifestyle changes if there is a socioeconomic challenge,” she said. “We can’t make change without understanding the community and culture that these youth live in. It’s also critical that we have participation of minorities and other research participants with diverse backgrounds in order for [clinical] trials to be effective for the population that this disease is affecting.”

Another issue keeping drug trials of youth with type 2 diabetes from being completed is the entry criteria. Some studies require youth to be drug naive and have a hemoglobin A1c greater than 7%. “This is difficult, because many youth that are referred to our diabetes center already come in on metformin, leaving only about 7% of subjects available for this criteria,” Dr. Nadeau explained. Another common study entry criterion is being on metformin and having a hemoglobin A1c of about 7%, “so basically being a metformin failure,” she said. “This is difficult to meet because metformin is relatively effective in the early stages of diabetes.”

“We need clear strategies for research, prevention, and treatment. Clarifying unique pathophysiology, complications, and psychosocial impact will enable industry, academia, funding agencies, advocacy groups, and regulators to collectively evaluate the best approaches to research, treatment, and prevention,” Dr. Nadeau said.

The consensus conference participants recommended the following objectives: clarify the biology of type 2 diabetes in youth, obtain new pediatric information on drugs, encourage the use of appropriate medications, and inform clinical decision-making. “We have a desperate need to understand the actions of drugs in type 2 diabetes youth,” Dr. Nadeau said. “Our current approach is not working. Potential solutions include considering efficacy outcomes besides A1c, potentially looking at improvement in insulin sensitivity, preservation of beta-cell function, trying to prevent the A1c increase instead of looking for an A1c reduction, and trying to extrapolate from effects in adults, if we can understand enough to do that.”

The conference participants also called for infrastructure changes, such as creating a resource for patients with type 2 diabetes in the model of the Type 1 Diabetes Exchange. “We need to have collaborations internationally,” she said. “We also need support for teams and clinical groups to work together to be able to accomplish these collaboratively.”

Dr. Nadeau reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – For adolescents and children with type 2 diabetes, there aren’t a lot of therapeutic options other than insulin and metformin. And the situation isn’t likely to change without extraordinary collaboration, Kristen J. Nadeau, MD, research director of the department of pediatric endocrinology at Children’s Hospital Colorado, Colorado Springs, said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Type 2 diabetes in youth appears to differ not only from pediatric type 1 diabetes, but also from adult type 2 diabetes, and current treatment options are limited,” Dr. Nadeau said. The estimated number of type 2 diabetes cases in the United States per year stands at 1,469,000 cases (12.3 per 100) in adults, compared with 5,100 (0.5 per 100) in youth. In adults there is a slight male predominance, whereas in kids girls are almost twice as likely as boys to be affected. Moreover, beta cell function declines faster in youth with type 2 diabetes.

The majority of insulins used by adults with type 2 diabetes are also approved for use in children and adolescents, but the only non-insulin medication approved for youth is metformin. According to Dr. Nadeau, 11 clinical safety and efficacy studies and 3 pharmacokinetic studies are ongoing for four DPP-4 inhibitors, two GLP-1 analogs, three SGLT2 inhibitors, colesevelam, bromocriptine, and insulins. A total of 5,000 youth are needed to complete current and planned trials, which “would require 100% participation from every child diagnosed in the next year, which is not feasible,” she said.

The required safety and efficacy studies are too difficult “because of the combination of unique challenges of the target population, study design concerns, and a lack of collaboration between agencies,” Dr. Nadeau said during a session that focused on the conclusions of the American Diabetes Association’s consensus conference on youth with type 2 diabetes, which took place on Oct. 20, 2015 in Alexandria, Va.

The consensus report was published online in Diabetes Care, and addresses the current status of type 2 diabetes in youth, the challenges of treatment, and priorities for research. Dr. Nadeau co-chaired the effort along with Dr. Philip Zeitler, section head of pediatric endocrinology at Children’s Hospital Colorado and medical director of the Children’s Hospital Colorado Clinical and Translational Research Center, Denver. Collaborators included the American Academy of Pediatrics, the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes, and the Pediatric Endocrine Society.

One example of the research challenges is evident in data from the Today trial, which found that only about 39% of kids with type 2 diabetes live with both parents (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jan; 96[1]:159-67). “Whenever you have only one parent in the home, there are difficulties with transportation by definition, so it’s a lot harder for these kids to participate in studies,” Dr. Nadeau said. “In addition, only 17% of their parents had a college or advanced education and 41% had a household income of less than $25,000 per year.”

The social environment is critical, she continued, because the lifestyle factors associated with type 2 diabetes often result in poor outcomes. “It’s very hard to make lifestyle changes if there is a socioeconomic challenge,” she said. “We can’t make change without understanding the community and culture that these youth live in. It’s also critical that we have participation of minorities and other research participants with diverse backgrounds in order for [clinical] trials to be effective for the population that this disease is affecting.”

Another issue keeping drug trials of youth with type 2 diabetes from being completed is the entry criteria. Some studies require youth to be drug naive and have a hemoglobin A1c greater than 7%. “This is difficult, because many youth that are referred to our diabetes center already come in on metformin, leaving only about 7% of subjects available for this criteria,” Dr. Nadeau explained. Another common study entry criterion is being on metformin and having a hemoglobin A1c of about 7%, “so basically being a metformin failure,” she said. “This is difficult to meet because metformin is relatively effective in the early stages of diabetes.”

“We need clear strategies for research, prevention, and treatment. Clarifying unique pathophysiology, complications, and psychosocial impact will enable industry, academia, funding agencies, advocacy groups, and regulators to collectively evaluate the best approaches to research, treatment, and prevention,” Dr. Nadeau said.

The consensus conference participants recommended the following objectives: clarify the biology of type 2 diabetes in youth, obtain new pediatric information on drugs, encourage the use of appropriate medications, and inform clinical decision-making. “We have a desperate need to understand the actions of drugs in type 2 diabetes youth,” Dr. Nadeau said. “Our current approach is not working. Potential solutions include considering efficacy outcomes besides A1c, potentially looking at improvement in insulin sensitivity, preservation of beta-cell function, trying to prevent the A1c increase instead of looking for an A1c reduction, and trying to extrapolate from effects in adults, if we can understand enough to do that.”

The conference participants also called for infrastructure changes, such as creating a resource for patients with type 2 diabetes in the model of the Type 1 Diabetes Exchange. “We need to have collaborations internationally,” she said. “We also need support for teams and clinical groups to work together to be able to accomplish these collaboratively.”

Dr. Nadeau reported having no financial disclosures.

Patient-specific model takes variability out of blood glucose average

Researchers have identified a patient-specific correction factor based on the age of a patient’s red blood cells that can improve the accuracy of average blood glucose estimations from hemoglobin A1c measures in patients with diabetes.

“The true average glucose concentration of a nondiabetic and a poorly controlled diabetic may differ by less than 15 mg/dL, but patients with identical HbA1c values may have true average glucose concentrations that differ by more than 60 mg/dL,” wrote Roy Malka, PhD, a mathematician and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates.

In an article published in the Oct. 5 online edition of Science Translational Medicine, the researchers reported the development of a mathematical model for HbA1c formation inside the red blood cell, based on the chemical contributions of glycemic and nonglycemic factors, as well as the average age of a patient’s red blood cells.

Using existing continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data from four different groups – totaling more than 200 diabetes patients – the researchers then personalized the parameters of the model to each patient to see the impact of patient-specific variation in the relationship between average concentration of glucose in the blood and HbA1c.