User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Continuous glucose monitoring benefits patients with type 1 diabetes

, according to two separate randomized trials reported online Jan. 24 in JAMA.

Compared with usual care, continuous glucose monitoring decreased mean HbA1c levels by 0.6% in a multicenter open-label U.S. study involving 158 participants and by 0.4% in a multicenter open-label crossover trial in Sweden. Both research groups noted that lengthier trials are needed to assess longer-term effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in this patient population, the possible adverse effects of long-term use, and whether the reduction in HbA1c levels translates into improved clinical outcomes.

The first trial, which was conducted at 24 U.S. endocrinology practices, involved patients aged 25 and older (mean age, 48 years) who had had type 1 diabetes for a median of 19 years and whose baseline HbA1c levels ranged from 7.5% to 10%. A total of 105 of these participants were randomly assigned to use continuous glucose monitoring (CGM group) and 53 to receive usual care (control group) for 24 weeks, said Roy W. Beck, MD, PhD, of the Jaeb Center for Health Research, Tampa, and his associates.

The CGM group was instructed to wear the device on at least 85% of days and to calibrate it at least twice per day, and they were to verify their glucose level by doing blood glucose meter testing at least three times daily before injecting insulin. The control group was instructed to do blood glucose meter testing at least four times per day.

The primary outcome, reduction in HbA1c level, was 1.1% at 12 weeks and 1% at 24 weeks with CGM, compared with 0.5% at 12 weeks and 0.4% at 24 weeks with usual care. At the end of the treatment period, the mean difference between the two study groups in HbA1c reduction was 0.6%.

Secondary outcomes also favored CGM, including the time spent with glucose levels within the target range of 70-180 mg/dL, duration of hypoglycemia, duration of hyperglycemia, and glycemic variability. In addition, patients reported a high level of satisfaction with CGM, Dr. Beck and his associates said (JAMA. 2017 Jan 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19975).

The second trial was conducted at 15 medical centers in Sweden and involved 161 adults aged 18 and older (mean age, 44 years) whose baseline HbA1c levels were 7.5% or higher. The participants served as their own controls, randomly assigned to use either CGM or usual care for 26 weeks and then to crossover to the other group for 26 weeks, said Marcus Lind, MD, PhD, of the diabetes outpatient clinic, Uddevalla (Sweden) Hospital, and his associates.

The primary outcome, reduction in HbA1c level, was lower by 0.4% with CGM than with usual care. In addition, secondary outcomes also favored CGM, including treatment satisfaction, patient concern about having a hypoglycemic episode, overall well-being, and mean glucose levels. However, in this study, patients measured their blood glucose levels less often with CGM (2.7 measurements per day) than with usual care (3.7 measurements per day).

One patient developed an allergic reaction to the device’s internal sensor and had it removed, according to Dr. Lind and his associates (JAMA. 2017 Jan 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19976).

Dr. Beck’s study was sponsored by Dexcom, maker of the CGM device, which also participated in designing the study, writing the protocol, reviewing and approving the manuscripts, and interpreting the data. Dr. Beck reported financial relationships with Dexcom and Abbott Diabetes Care, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. Dr. Lind’s study was sponsored by the NU Hospital Group and Dexcom. Dr. Lind reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Rubin Medical, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Both of these studies show a clear benefit with continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 1 diabetes, but there are a few concerns.

First, CGM is expensive, and insurers may be reluctant to pay for this device in light of the relatively modest benefits reported by Beck et al. and Lind et al. Second, CGM is invasive and still requires patients to monitor their blood glucose with needle sticks several times per day – two factors that may limit its acceptability to many patients.

Third, the clinicians in these trials were experienced with using CGM and instructing patients in its use. Most clinicians who are not endocrinologists, and even some endocrinologists, would not have the time to manage the volume of data generated by the device and to guide patients’ lifestyle and insulin dosage changes accordingly, given the current time constraints in managing diabetes care.

Mayer B. Davidson, MD, is at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Davidson made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA. 2017;317:363-4).

Both of these studies show a clear benefit with continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 1 diabetes, but there are a few concerns.

First, CGM is expensive, and insurers may be reluctant to pay for this device in light of the relatively modest benefits reported by Beck et al. and Lind et al. Second, CGM is invasive and still requires patients to monitor their blood glucose with needle sticks several times per day – two factors that may limit its acceptability to many patients.

Third, the clinicians in these trials were experienced with using CGM and instructing patients in its use. Most clinicians who are not endocrinologists, and even some endocrinologists, would not have the time to manage the volume of data generated by the device and to guide patients’ lifestyle and insulin dosage changes accordingly, given the current time constraints in managing diabetes care.

Mayer B. Davidson, MD, is at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Davidson made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA. 2017;317:363-4).

Both of these studies show a clear benefit with continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 1 diabetes, but there are a few concerns.

First, CGM is expensive, and insurers may be reluctant to pay for this device in light of the relatively modest benefits reported by Beck et al. and Lind et al. Second, CGM is invasive and still requires patients to monitor their blood glucose with needle sticks several times per day – two factors that may limit its acceptability to many patients.

Third, the clinicians in these trials were experienced with using CGM and instructing patients in its use. Most clinicians who are not endocrinologists, and even some endocrinologists, would not have the time to manage the volume of data generated by the device and to guide patients’ lifestyle and insulin dosage changes accordingly, given the current time constraints in managing diabetes care.

Mayer B. Davidson, MD, is at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Davidson made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA. 2017;317:363-4).

, according to two separate randomized trials reported online Jan. 24 in JAMA.

Compared with usual care, continuous glucose monitoring decreased mean HbA1c levels by 0.6% in a multicenter open-label U.S. study involving 158 participants and by 0.4% in a multicenter open-label crossover trial in Sweden. Both research groups noted that lengthier trials are needed to assess longer-term effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in this patient population, the possible adverse effects of long-term use, and whether the reduction in HbA1c levels translates into improved clinical outcomes.

The first trial, which was conducted at 24 U.S. endocrinology practices, involved patients aged 25 and older (mean age, 48 years) who had had type 1 diabetes for a median of 19 years and whose baseline HbA1c levels ranged from 7.5% to 10%. A total of 105 of these participants were randomly assigned to use continuous glucose monitoring (CGM group) and 53 to receive usual care (control group) for 24 weeks, said Roy W. Beck, MD, PhD, of the Jaeb Center for Health Research, Tampa, and his associates.

The CGM group was instructed to wear the device on at least 85% of days and to calibrate it at least twice per day, and they were to verify their glucose level by doing blood glucose meter testing at least three times daily before injecting insulin. The control group was instructed to do blood glucose meter testing at least four times per day.

The primary outcome, reduction in HbA1c level, was 1.1% at 12 weeks and 1% at 24 weeks with CGM, compared with 0.5% at 12 weeks and 0.4% at 24 weeks with usual care. At the end of the treatment period, the mean difference between the two study groups in HbA1c reduction was 0.6%.

Secondary outcomes also favored CGM, including the time spent with glucose levels within the target range of 70-180 mg/dL, duration of hypoglycemia, duration of hyperglycemia, and glycemic variability. In addition, patients reported a high level of satisfaction with CGM, Dr. Beck and his associates said (JAMA. 2017 Jan 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19975).

The second trial was conducted at 15 medical centers in Sweden and involved 161 adults aged 18 and older (mean age, 44 years) whose baseline HbA1c levels were 7.5% or higher. The participants served as their own controls, randomly assigned to use either CGM or usual care for 26 weeks and then to crossover to the other group for 26 weeks, said Marcus Lind, MD, PhD, of the diabetes outpatient clinic, Uddevalla (Sweden) Hospital, and his associates.

The primary outcome, reduction in HbA1c level, was lower by 0.4% with CGM than with usual care. In addition, secondary outcomes also favored CGM, including treatment satisfaction, patient concern about having a hypoglycemic episode, overall well-being, and mean glucose levels. However, in this study, patients measured their blood glucose levels less often with CGM (2.7 measurements per day) than with usual care (3.7 measurements per day).

One patient developed an allergic reaction to the device’s internal sensor and had it removed, according to Dr. Lind and his associates (JAMA. 2017 Jan 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19976).

Dr. Beck’s study was sponsored by Dexcom, maker of the CGM device, which also participated in designing the study, writing the protocol, reviewing and approving the manuscripts, and interpreting the data. Dr. Beck reported financial relationships with Dexcom and Abbott Diabetes Care, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. Dr. Lind’s study was sponsored by the NU Hospital Group and Dexcom. Dr. Lind reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Rubin Medical, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

, according to two separate randomized trials reported online Jan. 24 in JAMA.

Compared with usual care, continuous glucose monitoring decreased mean HbA1c levels by 0.6% in a multicenter open-label U.S. study involving 158 participants and by 0.4% in a multicenter open-label crossover trial in Sweden. Both research groups noted that lengthier trials are needed to assess longer-term effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in this patient population, the possible adverse effects of long-term use, and whether the reduction in HbA1c levels translates into improved clinical outcomes.

The first trial, which was conducted at 24 U.S. endocrinology practices, involved patients aged 25 and older (mean age, 48 years) who had had type 1 diabetes for a median of 19 years and whose baseline HbA1c levels ranged from 7.5% to 10%. A total of 105 of these participants were randomly assigned to use continuous glucose monitoring (CGM group) and 53 to receive usual care (control group) for 24 weeks, said Roy W. Beck, MD, PhD, of the Jaeb Center for Health Research, Tampa, and his associates.

The CGM group was instructed to wear the device on at least 85% of days and to calibrate it at least twice per day, and they were to verify their glucose level by doing blood glucose meter testing at least three times daily before injecting insulin. The control group was instructed to do blood glucose meter testing at least four times per day.

The primary outcome, reduction in HbA1c level, was 1.1% at 12 weeks and 1% at 24 weeks with CGM, compared with 0.5% at 12 weeks and 0.4% at 24 weeks with usual care. At the end of the treatment period, the mean difference between the two study groups in HbA1c reduction was 0.6%.

Secondary outcomes also favored CGM, including the time spent with glucose levels within the target range of 70-180 mg/dL, duration of hypoglycemia, duration of hyperglycemia, and glycemic variability. In addition, patients reported a high level of satisfaction with CGM, Dr. Beck and his associates said (JAMA. 2017 Jan 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19975).

The second trial was conducted at 15 medical centers in Sweden and involved 161 adults aged 18 and older (mean age, 44 years) whose baseline HbA1c levels were 7.5% or higher. The participants served as their own controls, randomly assigned to use either CGM or usual care for 26 weeks and then to crossover to the other group for 26 weeks, said Marcus Lind, MD, PhD, of the diabetes outpatient clinic, Uddevalla (Sweden) Hospital, and his associates.

The primary outcome, reduction in HbA1c level, was lower by 0.4% with CGM than with usual care. In addition, secondary outcomes also favored CGM, including treatment satisfaction, patient concern about having a hypoglycemic episode, overall well-being, and mean glucose levels. However, in this study, patients measured their blood glucose levels less often with CGM (2.7 measurements per day) than with usual care (3.7 measurements per day).

One patient developed an allergic reaction to the device’s internal sensor and had it removed, according to Dr. Lind and his associates (JAMA. 2017 Jan 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19976).

Dr. Beck’s study was sponsored by Dexcom, maker of the CGM device, which also participated in designing the study, writing the protocol, reviewing and approving the manuscripts, and interpreting the data. Dr. Beck reported financial relationships with Dexcom and Abbott Diabetes Care, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. Dr. Lind’s study was sponsored by the NU Hospital Group and Dexcom. Dr. Lind reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Rubin Medical, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: A 6-month course of continuous glucose monitoring modestly reduced HbA1c levels in patients with type 1 diabetes who used multiple daily insulin injections.

Major finding: Compared with usual care, continuous glucose monitoring decreased mean HbA1c by 0.6% in a multicenter open-label U.S. study involving 158 participants and by 0.4% in a multicenter open-label crossover trial in Sweden.

Data source: Two separate short-term randomized trials comparing the effect of continuous glucose monitoring against usual care in 319 adults with type 1 diabetes.

Disclosures: Dr. Beck’s study was sponsored by Dexcom, maker of the CGM device, which also participated in designing the study, writing the protocol, reviewing and approving the manuscripts, and interpreting the data. Dr. Beck reported financial relationships with Dexcom and Abbott Diabetes Care, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources. Dr. Lind’s study was sponsored by the NU Hospital Group and Dexcom. Dr. Lind reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Rubin Medical, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Unique microbiota mix found in guts of T1D patients

potentially offering early insight into possible links between the disease and gut germs.

The findings by an Italian team don’t confirm any connection between bacteria in the digestive system and diabetes. Still, “this study is probably the best example to date in the literature of inflammatory events happening in the gut that are correlated with type 1 diabetes,” said Aleksandar Kostic, PhD, of the department of microbiology and immunobiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who conducts similar research.

At issue: What role, if any, does the gut play in the development of type 1 diabetes (T1D)? Scientists already believe that the gut microbiome directly affects metabolism and the development of type 2 diabetes, according to Dr. Kostic. But T1D is an autoimmune disease, not a metabolic one, he said, “and the mechanisms are very different. For type 1, we don’t know a whole lot. We’re in the very early days.”

Still, “there’s a theory that inflammatory stimulus in the gut that is somehow partially responsible for causing T1D. The idea is that the microbiome is less diverse, which means that it loses its integrity in some way and loses the ability to crowd out inflammatory organisms,” he said in an interview.

For the new study, researchers led by scientists at Milan’s IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute measured inflammation and the microbiome in the duodenal mucosa of 19 patients with T1D, 19 with celiac disease, and 16 healthy controls. They reported their findings online Jan. 19 (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3222).

The researchers found a unique inflammation profile through an analysis of gene expression in the patients with T1D. They called it a “peculiar signature” that’s notable for increased numbers of infiltration from the monocyte/macrophage lineage.

“In T1D patients, we didn’t observe any correlation between gene expression and [hemoglobin A1c] level, duration of diabetes, presence of secondary complications or the reason that led to endoscopy, indicating that gene expression was not influenced by these variables,” the researchers write.

They also found a “specific microbiota composition” featuring a reduction in the role of Proteobacteria and an increase in Firmicutes; this was unique to the T1D patients. Bacteroidetes “showed a trend to reduction” in both T1D and celiac patients compared to the controls.

“The expression of genes specific for T1D inflammation was associated with the abundance of specific bacteria in duodenum,” the researchers added.

Elena Barengolts, MD, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Illinois, Chicago, who’s familiar with the study, said it appears to be valid. However, the methods used have limited powers to define specific types of bacteria, making it difficult to know if the germs in question are “bad” or “good,” she said in an interview.

For his part, Dr. Kostic said the findings are “really neat” and consistent with previous findings regarding the role of the gut microbiome and T1D. He pointed to a study he led that found less-diverse microbiomes in the guts of Finnish infants with T1D (Cell Host Microbe. 2015 Feb 11;17[2]:260-73).

As a result, the gut microbiome is “functionally capable of doing fewer things, and the community gets overrun by certain pathogens,” he said. “We saw that a lot of organisms were capable of promoting inflammation in the gut.”

Dr. Kostic, Dr. Barengolts, and the study authors report no relevant disclosures.

potentially offering early insight into possible links between the disease and gut germs.

The findings by an Italian team don’t confirm any connection between bacteria in the digestive system and diabetes. Still, “this study is probably the best example to date in the literature of inflammatory events happening in the gut that are correlated with type 1 diabetes,” said Aleksandar Kostic, PhD, of the department of microbiology and immunobiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who conducts similar research.

At issue: What role, if any, does the gut play in the development of type 1 diabetes (T1D)? Scientists already believe that the gut microbiome directly affects metabolism and the development of type 2 diabetes, according to Dr. Kostic. But T1D is an autoimmune disease, not a metabolic one, he said, “and the mechanisms are very different. For type 1, we don’t know a whole lot. We’re in the very early days.”

Still, “there’s a theory that inflammatory stimulus in the gut that is somehow partially responsible for causing T1D. The idea is that the microbiome is less diverse, which means that it loses its integrity in some way and loses the ability to crowd out inflammatory organisms,” he said in an interview.

For the new study, researchers led by scientists at Milan’s IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute measured inflammation and the microbiome in the duodenal mucosa of 19 patients with T1D, 19 with celiac disease, and 16 healthy controls. They reported their findings online Jan. 19 (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3222).

The researchers found a unique inflammation profile through an analysis of gene expression in the patients with T1D. They called it a “peculiar signature” that’s notable for increased numbers of infiltration from the monocyte/macrophage lineage.

“In T1D patients, we didn’t observe any correlation between gene expression and [hemoglobin A1c] level, duration of diabetes, presence of secondary complications or the reason that led to endoscopy, indicating that gene expression was not influenced by these variables,” the researchers write.

They also found a “specific microbiota composition” featuring a reduction in the role of Proteobacteria and an increase in Firmicutes; this was unique to the T1D patients. Bacteroidetes “showed a trend to reduction” in both T1D and celiac patients compared to the controls.

“The expression of genes specific for T1D inflammation was associated with the abundance of specific bacteria in duodenum,” the researchers added.

Elena Barengolts, MD, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Illinois, Chicago, who’s familiar with the study, said it appears to be valid. However, the methods used have limited powers to define specific types of bacteria, making it difficult to know if the germs in question are “bad” or “good,” she said in an interview.

For his part, Dr. Kostic said the findings are “really neat” and consistent with previous findings regarding the role of the gut microbiome and T1D. He pointed to a study he led that found less-diverse microbiomes in the guts of Finnish infants with T1D (Cell Host Microbe. 2015 Feb 11;17[2]:260-73).

As a result, the gut microbiome is “functionally capable of doing fewer things, and the community gets overrun by certain pathogens,” he said. “We saw that a lot of organisms were capable of promoting inflammation in the gut.”

Dr. Kostic, Dr. Barengolts, and the study authors report no relevant disclosures.

potentially offering early insight into possible links between the disease and gut germs.

The findings by an Italian team don’t confirm any connection between bacteria in the digestive system and diabetes. Still, “this study is probably the best example to date in the literature of inflammatory events happening in the gut that are correlated with type 1 diabetes,” said Aleksandar Kostic, PhD, of the department of microbiology and immunobiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who conducts similar research.

At issue: What role, if any, does the gut play in the development of type 1 diabetes (T1D)? Scientists already believe that the gut microbiome directly affects metabolism and the development of type 2 diabetes, according to Dr. Kostic. But T1D is an autoimmune disease, not a metabolic one, he said, “and the mechanisms are very different. For type 1, we don’t know a whole lot. We’re in the very early days.”

Still, “there’s a theory that inflammatory stimulus in the gut that is somehow partially responsible for causing T1D. The idea is that the microbiome is less diverse, which means that it loses its integrity in some way and loses the ability to crowd out inflammatory organisms,” he said in an interview.

For the new study, researchers led by scientists at Milan’s IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute measured inflammation and the microbiome in the duodenal mucosa of 19 patients with T1D, 19 with celiac disease, and 16 healthy controls. They reported their findings online Jan. 19 (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3222).

The researchers found a unique inflammation profile through an analysis of gene expression in the patients with T1D. They called it a “peculiar signature” that’s notable for increased numbers of infiltration from the monocyte/macrophage lineage.

“In T1D patients, we didn’t observe any correlation between gene expression and [hemoglobin A1c] level, duration of diabetes, presence of secondary complications or the reason that led to endoscopy, indicating that gene expression was not influenced by these variables,” the researchers write.

They also found a “specific microbiota composition” featuring a reduction in the role of Proteobacteria and an increase in Firmicutes; this was unique to the T1D patients. Bacteroidetes “showed a trend to reduction” in both T1D and celiac patients compared to the controls.

“The expression of genes specific for T1D inflammation was associated with the abundance of specific bacteria in duodenum,” the researchers added.

Elena Barengolts, MD, of the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Illinois, Chicago, who’s familiar with the study, said it appears to be valid. However, the methods used have limited powers to define specific types of bacteria, making it difficult to know if the germs in question are “bad” or “good,” she said in an interview.

For his part, Dr. Kostic said the findings are “really neat” and consistent with previous findings regarding the role of the gut microbiome and T1D. He pointed to a study he led that found less-diverse microbiomes in the guts of Finnish infants with T1D (Cell Host Microbe. 2015 Feb 11;17[2]:260-73).

As a result, the gut microbiome is “functionally capable of doing fewer things, and the community gets overrun by certain pathogens,” he said. “We saw that a lot of organisms were capable of promoting inflammation in the gut.”

Dr. Kostic, Dr. Barengolts, and the study authors report no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM

Key clinical point: Patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) show signs of unique inflammation and microbiota in the duodenal mucosa, compared with controls and celiac patients.

Major finding: T1D patients had a “peculiar” inflammation signature and a unique microbiota composition, and there’s a sign of a link between inflammation and bacteria levels.

Data source: An analysis of 19 patients with T1D, 19 with celiac disease, and 16 healthy controls.

Disclosures: The study was supported by institutional funds, and the authors report no relevant disclosures.

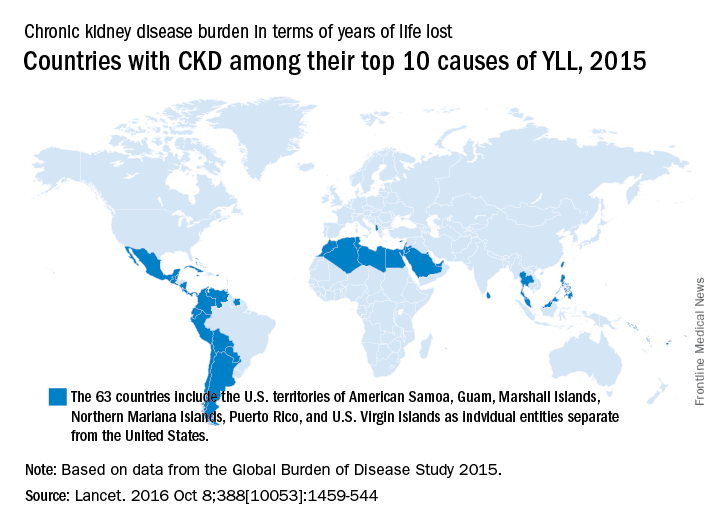

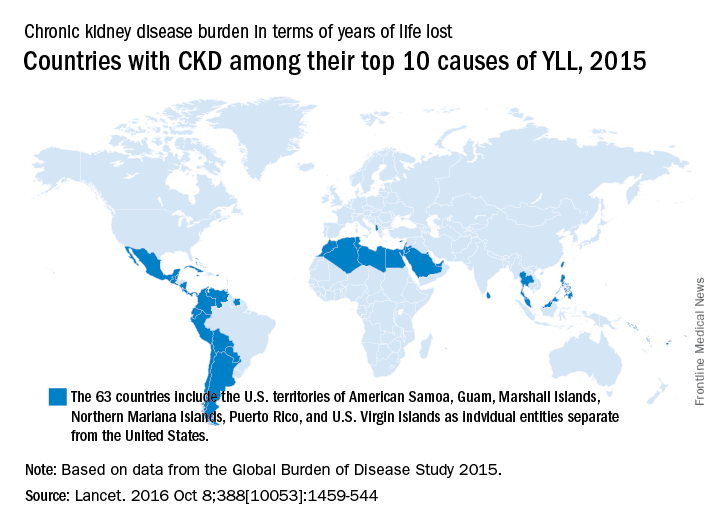

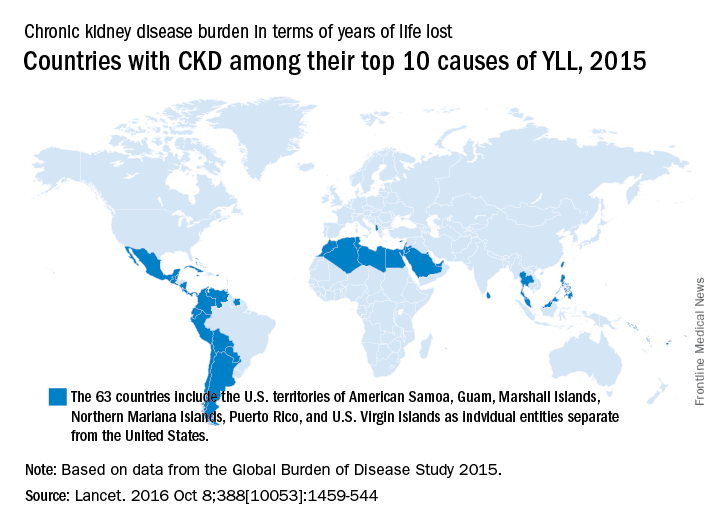

CKD death rate highest in Mexico

A global measure of chronic kidney disease dropped by 3.9% from 2005 to 2015, but CKD remains a top-10 burden in 63 countries, according to the Global Burden of Disease 2015 study.

The age-standardized rate of years of life lost (YLL) for CKD dropped by 3.9%, even though its global YLL rank rose from 21st to 17th and total CKD mortality was up by almost 32%, the Global Burden of Disease 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators reported (Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388[10053]:1459-544). The increase in the number of deaths comes largely “because of improved estimates within countries with large populations such as China, India, and Russia,” the collaborators pointed out.

“In 2015, Latin America had the highest chronic kidney disease death rates in the world. Within Mexico, the country with the highest chronic kidney disease death rate, more than half of patients with incident end-stage renal disease have an underlying diagnosis of diabetes mellitus,” the investigators wrote.

The study is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

A global measure of chronic kidney disease dropped by 3.9% from 2005 to 2015, but CKD remains a top-10 burden in 63 countries, according to the Global Burden of Disease 2015 study.

The age-standardized rate of years of life lost (YLL) for CKD dropped by 3.9%, even though its global YLL rank rose from 21st to 17th and total CKD mortality was up by almost 32%, the Global Burden of Disease 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators reported (Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388[10053]:1459-544). The increase in the number of deaths comes largely “because of improved estimates within countries with large populations such as China, India, and Russia,” the collaborators pointed out.

“In 2015, Latin America had the highest chronic kidney disease death rates in the world. Within Mexico, the country with the highest chronic kidney disease death rate, more than half of patients with incident end-stage renal disease have an underlying diagnosis of diabetes mellitus,” the investigators wrote.

The study is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

A global measure of chronic kidney disease dropped by 3.9% from 2005 to 2015, but CKD remains a top-10 burden in 63 countries, according to the Global Burden of Disease 2015 study.

The age-standardized rate of years of life lost (YLL) for CKD dropped by 3.9%, even though its global YLL rank rose from 21st to 17th and total CKD mortality was up by almost 32%, the Global Burden of Disease 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators reported (Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388[10053]:1459-544). The increase in the number of deaths comes largely “because of improved estimates within countries with large populations such as China, India, and Russia,” the collaborators pointed out.

“In 2015, Latin America had the highest chronic kidney disease death rates in the world. Within Mexico, the country with the highest chronic kidney disease death rate, more than half of patients with incident end-stage renal disease have an underlying diagnosis of diabetes mellitus,” the investigators wrote.

The study is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

FROM THE LANCET

VIDEO: Protein-rich diet can help manage type 2 diabetes, NAFLD

Patients with type 2 diabetes should be put on diets rich in either animal or plant protein to reduce not only liver fat, but insulin resistance and hepatic necroinflammation markers as well, according to a study published in the February issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.007).

“High-protein diets have shown variable and sometimes even favorable effects on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity in people with type 2 diabetes and it is unclear which metabolic pathways are involved,” wrote the authors of the study, led by Mariya Markova, MD, of the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke in Nuthetal, Germany.

SOURCE: American Gastroenterological Association

Obesity and insulin resistance have long been linked to liver fat, with excessive amounts of the latter causing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), with a significant risk of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) developing as well. Compounding this issue, at least in the United States, are widespread dietary and nutritional habits that promote consumption of animal protein, carbohydrates, and saturated fats. This “hypercaloric Western style diet,” as the authors call it, exacerbates the accumulation of fat deposits in the liver and complicates the health of patients across the country, regardless of weight.

“Remarkably, diets restricted in methionine were shown to prevent the development of insulin resistance and of the metabolic syndrome in animal models [so] the type of protein may elicit different metabolic responses depending on the amino acid composition,” Dr. Markova and her coinvestigators noted. “It is therefore hypothesized that high-plant-protein diets exert favorable effects on hepatic fat content and metabolic responses as compared to high intake of animal protein rich in BCAA [branched-chain amino acids] and methionine,” both of which can be found in suitably low levels via plant protein.

Dr. Markova and her team devised a prospective, randomized, open-label clinical trial involving 44 patients with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD, all of whom were recruited at the department of clinical nutrition of the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke between June 2013 and March 2015. Subjects were randomized into one of two cohorts, each of which were assigned a diet rich in either animal protein (AP) or plant protein (PP) for a period of 6 weeks. Median body mass index in the AP cohort was 31.0 ± 0.8, and was 29.4 ± 1.0 in the PP cohort.

The AP cohort diet consisted mainly of meat and dairy products, while legumes constituted the bulk of the PP cohort diet. Both diets were isocaloric and had the same macronutrient makeup: 30% protein, 40% carbohydrates, and 30% fat. Seven subjects dropped out prior to completion of the study; of the 37 that remained all the way through – 19 in the AP cohort, 18 in the PP cohort – the age range was 49-78 years. Subjects maintained the same physical exercise regimens throughout the study that they had beforehand, and were asked not to alter them. Hemoglobin A1c levels ranged from 5.8% to 8.8% at baseline, and evaluations were carried out at fasting levels for each subject.

Patients in both cohorts saw significant decreases in intrahepatic fat content by the end of the trial period. Those in the AP cohort saw decreases of 48.0% (P = .0002), while those in the PP cohort saw a decrease of 35.7% (P = .001). Perhaps most importantly, the reductions in both cohorts were not correlated to body weight. In addition, levels of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), which has been shown to be a predictive marker of NAFLD, decreased by nearly 50% for both AP and PP cohorts (P less than .0002 for both).

“Despite the elevated intake and postprandial uptake of methionine and BCAA in the AP group, there was no indication of negative effects of these components,” the authors stated in the study. “The origin of protein – animal or plant – did not play a major role. Both high-protein diets unexpectedly induced strong reductions of FGF21, which was associated with metabolic improvements and the decrease of IHL.”

Despite these findings, however, the 6-week time span used here is not sufficient to determine just how viable this diet may be in the long term, according to the authors. Further studies will be needed, and will need to take place over longer periods of time, to “show the durability of the responses and eventual adverse effects of the diets.” Furthermore, different age groups must be examined to find out if the benefits observed by Dr. Markova and her coinvestigators were somehow related to the age of these subjects.

The study was funded by grants from German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and German Center for Diabetes Research. Dr. Markova and her coauthors did not report any financial disclosures.

Human studies to assess the effects of isocaloric macronutrient substitution are fraught with difficulty. If one macronutrient is increased, what happens to the others? If you observe an effect, is it the phenomenon you were seeking due to the macronutrient you altered, or an epiphenomenon due to changes in the others?

Markova et al. attempted to study a 6-week “isocaloric” increase of animal vs. plant protein (from 17% to 30% of calories as protein). However, a decrease of percent fat from 41% to 30%, and a reduction in carbohydrate from 42% to 40% occurred commensurately. This brings up three concerns. First, despite the diet’s being “isocaloric,” weight and body mass index decreased by 2 kg and 0.8 kg/m2, respectively. Reductions in intrahepatic, visceral, and subcutaneous fat, and an increase in lean body mass were noted. So was the diet isocaloric? Protein reduces plasma ghrelin levels and is more satiating. Furthermore, metabolism of protein to ATP is inefficient compared to that of carbohydrate or fat. The authors say only that calories were “unrestricted.” These issues do not engender “isocaloric” confidence.

Lastly, the type of carbohydrate was not controlled for. Fructose is significantly more lipogenic than glucose. Yet they were lumped together as “carbohydrate,” and were uncontrolled. So what macronutrient really caused the reduction in liver fat? These methodological issues detract from the author’s message, and this study must be considered preliminary.

Robert H. Lustig, MD, MSL, is in the division of pediatric endocrinology, UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, San Francisco; member, UCSF Institute for Health Policy Studies. Dr. Lustig declared no conflicts of interest.

Human studies to assess the effects of isocaloric macronutrient substitution are fraught with difficulty. If one macronutrient is increased, what happens to the others? If you observe an effect, is it the phenomenon you were seeking due to the macronutrient you altered, or an epiphenomenon due to changes in the others?

Markova et al. attempted to study a 6-week “isocaloric” increase of animal vs. plant protein (from 17% to 30% of calories as protein). However, a decrease of percent fat from 41% to 30%, and a reduction in carbohydrate from 42% to 40% occurred commensurately. This brings up three concerns. First, despite the diet’s being “isocaloric,” weight and body mass index decreased by 2 kg and 0.8 kg/m2, respectively. Reductions in intrahepatic, visceral, and subcutaneous fat, and an increase in lean body mass were noted. So was the diet isocaloric? Protein reduces plasma ghrelin levels and is more satiating. Furthermore, metabolism of protein to ATP is inefficient compared to that of carbohydrate or fat. The authors say only that calories were “unrestricted.” These issues do not engender “isocaloric” confidence.

Lastly, the type of carbohydrate was not controlled for. Fructose is significantly more lipogenic than glucose. Yet they were lumped together as “carbohydrate,” and were uncontrolled. So what macronutrient really caused the reduction in liver fat? These methodological issues detract from the author’s message, and this study must be considered preliminary.

Robert H. Lustig, MD, MSL, is in the division of pediatric endocrinology, UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, San Francisco; member, UCSF Institute for Health Policy Studies. Dr. Lustig declared no conflicts of interest.

Human studies to assess the effects of isocaloric macronutrient substitution are fraught with difficulty. If one macronutrient is increased, what happens to the others? If you observe an effect, is it the phenomenon you were seeking due to the macronutrient you altered, or an epiphenomenon due to changes in the others?

Markova et al. attempted to study a 6-week “isocaloric” increase of animal vs. plant protein (from 17% to 30% of calories as protein). However, a decrease of percent fat from 41% to 30%, and a reduction in carbohydrate from 42% to 40% occurred commensurately. This brings up three concerns. First, despite the diet’s being “isocaloric,” weight and body mass index decreased by 2 kg and 0.8 kg/m2, respectively. Reductions in intrahepatic, visceral, and subcutaneous fat, and an increase in lean body mass were noted. So was the diet isocaloric? Protein reduces plasma ghrelin levels and is more satiating. Furthermore, metabolism of protein to ATP is inefficient compared to that of carbohydrate or fat. The authors say only that calories were “unrestricted.” These issues do not engender “isocaloric” confidence.

Lastly, the type of carbohydrate was not controlled for. Fructose is significantly more lipogenic than glucose. Yet they were lumped together as “carbohydrate,” and were uncontrolled. So what macronutrient really caused the reduction in liver fat? These methodological issues detract from the author’s message, and this study must be considered preliminary.

Robert H. Lustig, MD, MSL, is in the division of pediatric endocrinology, UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, San Francisco; member, UCSF Institute for Health Policy Studies. Dr. Lustig declared no conflicts of interest.

Patients with type 2 diabetes should be put on diets rich in either animal or plant protein to reduce not only liver fat, but insulin resistance and hepatic necroinflammation markers as well, according to a study published in the February issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.007).

“High-protein diets have shown variable and sometimes even favorable effects on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity in people with type 2 diabetes and it is unclear which metabolic pathways are involved,” wrote the authors of the study, led by Mariya Markova, MD, of the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke in Nuthetal, Germany.

SOURCE: American Gastroenterological Association

Obesity and insulin resistance have long been linked to liver fat, with excessive amounts of the latter causing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), with a significant risk of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) developing as well. Compounding this issue, at least in the United States, are widespread dietary and nutritional habits that promote consumption of animal protein, carbohydrates, and saturated fats. This “hypercaloric Western style diet,” as the authors call it, exacerbates the accumulation of fat deposits in the liver and complicates the health of patients across the country, regardless of weight.

“Remarkably, diets restricted in methionine were shown to prevent the development of insulin resistance and of the metabolic syndrome in animal models [so] the type of protein may elicit different metabolic responses depending on the amino acid composition,” Dr. Markova and her coinvestigators noted. “It is therefore hypothesized that high-plant-protein diets exert favorable effects on hepatic fat content and metabolic responses as compared to high intake of animal protein rich in BCAA [branched-chain amino acids] and methionine,” both of which can be found in suitably low levels via plant protein.

Dr. Markova and her team devised a prospective, randomized, open-label clinical trial involving 44 patients with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD, all of whom were recruited at the department of clinical nutrition of the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke between June 2013 and March 2015. Subjects were randomized into one of two cohorts, each of which were assigned a diet rich in either animal protein (AP) or plant protein (PP) for a period of 6 weeks. Median body mass index in the AP cohort was 31.0 ± 0.8, and was 29.4 ± 1.0 in the PP cohort.

The AP cohort diet consisted mainly of meat and dairy products, while legumes constituted the bulk of the PP cohort diet. Both diets were isocaloric and had the same macronutrient makeup: 30% protein, 40% carbohydrates, and 30% fat. Seven subjects dropped out prior to completion of the study; of the 37 that remained all the way through – 19 in the AP cohort, 18 in the PP cohort – the age range was 49-78 years. Subjects maintained the same physical exercise regimens throughout the study that they had beforehand, and were asked not to alter them. Hemoglobin A1c levels ranged from 5.8% to 8.8% at baseline, and evaluations were carried out at fasting levels for each subject.

Patients in both cohorts saw significant decreases in intrahepatic fat content by the end of the trial period. Those in the AP cohort saw decreases of 48.0% (P = .0002), while those in the PP cohort saw a decrease of 35.7% (P = .001). Perhaps most importantly, the reductions in both cohorts were not correlated to body weight. In addition, levels of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), which has been shown to be a predictive marker of NAFLD, decreased by nearly 50% for both AP and PP cohorts (P less than .0002 for both).

“Despite the elevated intake and postprandial uptake of methionine and BCAA in the AP group, there was no indication of negative effects of these components,” the authors stated in the study. “The origin of protein – animal or plant – did not play a major role. Both high-protein diets unexpectedly induced strong reductions of FGF21, which was associated with metabolic improvements and the decrease of IHL.”

Despite these findings, however, the 6-week time span used here is not sufficient to determine just how viable this diet may be in the long term, according to the authors. Further studies will be needed, and will need to take place over longer periods of time, to “show the durability of the responses and eventual adverse effects of the diets.” Furthermore, different age groups must be examined to find out if the benefits observed by Dr. Markova and her coinvestigators were somehow related to the age of these subjects.

The study was funded by grants from German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and German Center for Diabetes Research. Dr. Markova and her coauthors did not report any financial disclosures.

Patients with type 2 diabetes should be put on diets rich in either animal or plant protein to reduce not only liver fat, but insulin resistance and hepatic necroinflammation markers as well, according to a study published in the February issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.007).

“High-protein diets have shown variable and sometimes even favorable effects on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity in people with type 2 diabetes and it is unclear which metabolic pathways are involved,” wrote the authors of the study, led by Mariya Markova, MD, of the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke in Nuthetal, Germany.

SOURCE: American Gastroenterological Association

Obesity and insulin resistance have long been linked to liver fat, with excessive amounts of the latter causing nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), with a significant risk of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) developing as well. Compounding this issue, at least in the United States, are widespread dietary and nutritional habits that promote consumption of animal protein, carbohydrates, and saturated fats. This “hypercaloric Western style diet,” as the authors call it, exacerbates the accumulation of fat deposits in the liver and complicates the health of patients across the country, regardless of weight.

“Remarkably, diets restricted in methionine were shown to prevent the development of insulin resistance and of the metabolic syndrome in animal models [so] the type of protein may elicit different metabolic responses depending on the amino acid composition,” Dr. Markova and her coinvestigators noted. “It is therefore hypothesized that high-plant-protein diets exert favorable effects on hepatic fat content and metabolic responses as compared to high intake of animal protein rich in BCAA [branched-chain amino acids] and methionine,” both of which can be found in suitably low levels via plant protein.

Dr. Markova and her team devised a prospective, randomized, open-label clinical trial involving 44 patients with type 2 diabetes and NAFLD, all of whom were recruited at the department of clinical nutrition of the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke between June 2013 and March 2015. Subjects were randomized into one of two cohorts, each of which were assigned a diet rich in either animal protein (AP) or plant protein (PP) for a period of 6 weeks. Median body mass index in the AP cohort was 31.0 ± 0.8, and was 29.4 ± 1.0 in the PP cohort.

The AP cohort diet consisted mainly of meat and dairy products, while legumes constituted the bulk of the PP cohort diet. Both diets were isocaloric and had the same macronutrient makeup: 30% protein, 40% carbohydrates, and 30% fat. Seven subjects dropped out prior to completion of the study; of the 37 that remained all the way through – 19 in the AP cohort, 18 in the PP cohort – the age range was 49-78 years. Subjects maintained the same physical exercise regimens throughout the study that they had beforehand, and were asked not to alter them. Hemoglobin A1c levels ranged from 5.8% to 8.8% at baseline, and evaluations were carried out at fasting levels for each subject.

Patients in both cohorts saw significant decreases in intrahepatic fat content by the end of the trial period. Those in the AP cohort saw decreases of 48.0% (P = .0002), while those in the PP cohort saw a decrease of 35.7% (P = .001). Perhaps most importantly, the reductions in both cohorts were not correlated to body weight. In addition, levels of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), which has been shown to be a predictive marker of NAFLD, decreased by nearly 50% for both AP and PP cohorts (P less than .0002 for both).

“Despite the elevated intake and postprandial uptake of methionine and BCAA in the AP group, there was no indication of negative effects of these components,” the authors stated in the study. “The origin of protein – animal or plant – did not play a major role. Both high-protein diets unexpectedly induced strong reductions of FGF21, which was associated with metabolic improvements and the decrease of IHL.”

Despite these findings, however, the 6-week time span used here is not sufficient to determine just how viable this diet may be in the long term, according to the authors. Further studies will be needed, and will need to take place over longer periods of time, to “show the durability of the responses and eventual adverse effects of the diets.” Furthermore, different age groups must be examined to find out if the benefits observed by Dr. Markova and her coinvestigators were somehow related to the age of these subjects.

The study was funded by grants from German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and German Center for Diabetes Research. Dr. Markova and her coauthors did not report any financial disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Animal- and plant-protein diets reduced liver fat for type 2 diabetes patients by 36%-48% over the course of 6 months (P = .0002 and P = .001, respectively).

Data source: Prospective study of 37 type 2 diabetes patients from June 2013 to March 2015.

Disclosures: The German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and German Center for Diabetes Research supported the study. The authors did not report any financial disclosures.

Diabetes, ischemic heart disease, pain lead health spending

Diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and back and neck pain are the top three conditions accounting for the highest spending on personal health care in the United States, according to a report published online Dec. 27 in JAMA.

In addition, spending on pharmaceuticals – particularly diabetes therapies, antihypertensive drugs, and medications for hyperlipidemia – drove much of the massive increase in health care spending during the past 2 decades, said Joseph L. Dieleman, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, and his associates.

Recent increases in health care spending are well documented, but less is known about what is spent for individual conditions, in different health care settings, and in various patient age groups. To assess health care spending across these categories, the investigators collected and analyzed data for 1996 through 2013 from nationally representative surveys of households, nationally representative surveys of medical facilities, insurance claims, government budgets, and other official records.

They grouped the data into six type-of-care categories: inpatient care, ambulatory care, emergency department care, nursing facility care, dental care, and prescribed pharmaceuticals. “Spending on the six types of personal health care was then disaggregated across 155 mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive conditions and 38 age and sex groups,” with each sex being divided into 5-year age groups, the researchers noted.

Based on these data, the investigators came to the following conclusions:

• Twenty conditions accounted for approximately 58% of personal health care spending, which totaled an estimated $1.2 trillion in 2013.

• More resources were spent on diabetes than any other condition in 2013, at an estimated $101.4 billion. Prescribed medications accounted for nearly 60% of diabetes costs.

• The second-highest amount of health care spending was for ischemic heart disease, which accounted for $88.1 billion in 2013. Most such spending occurred in inpatient settings.

• Low-back and neck pain, comprising the third-highest level of spending, cost an estimated $87.6 billion. Approximately 60% of this spending occurred in ambulatory settings.

• Among all 155 conditions, spending for diabetes and low-back and neck pain increased the most during the 18-year study period.

• Among all six types of care, spending on pharmaceuticals and emergency care increased the most during the study period.

It is important to note that for the purposes of this study, cancer was disaggregated into 29 separate conditions, and none of them placed in the top 20 for health care spending, Dr. Dieleman and his associates noted (JAMA. 2016;316[24]:2627-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16885).

When spending was categorized by patient age groups, working-age adults accounted for the greatest amount spent in 2013, estimated at $1,070.1 billion. But that was followed closely by patients aged 65 and older, who accounted for an estimated $796.5 billion, much of which was spent on care in nursing facilities. The smallest amount of health care spending was in children over age 1 and adolescents, who accounted for an estimated $233.5 billion.

Among the other study findings:

• Spending on pharmaceutical treatment of two conditions, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, increased at more than double the rate of total health care spending. It totaled an estimated $135.7 billion in 2013.

• Other top-20 conditions included falls, depression, skin disorders such as acne and eczema, sense disorders such as vision correction and hearing loss, dental care, urinary disorders, and lower respiratory tract infection.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Vitality Institute. Dr. Dieleman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Dieleman et al. have “followed” the health care money, and the trail could ultimately lead to the United States changing how it spends a staggering, almost unimaginable amount – roughly $3.2 trillion in 2015 – on health care.

At the very least, their data indicate that the United States should pay more attention to managing physical pain, controlling the costs of pharmaceuticals, and promoting lifestyle interventions that prevent or ameliorate obesity and other factors contributing to diabetes and heart disease.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, is provost of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine and in the department of health care management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported receiving speaking fees from numerous industry sources. Dr. Emanuel made these remarks in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Dieleman’s report (JAMA 2016;316:2604-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16739).

Dieleman et al. have “followed” the health care money, and the trail could ultimately lead to the United States changing how it spends a staggering, almost unimaginable amount – roughly $3.2 trillion in 2015 – on health care.

At the very least, their data indicate that the United States should pay more attention to managing physical pain, controlling the costs of pharmaceuticals, and promoting lifestyle interventions that prevent or ameliorate obesity and other factors contributing to diabetes and heart disease.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, is provost of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine and in the department of health care management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported receiving speaking fees from numerous industry sources. Dr. Emanuel made these remarks in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Dieleman’s report (JAMA 2016;316:2604-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16739).

Dieleman et al. have “followed” the health care money, and the trail could ultimately lead to the United States changing how it spends a staggering, almost unimaginable amount – roughly $3.2 trillion in 2015 – on health care.

At the very least, their data indicate that the United States should pay more attention to managing physical pain, controlling the costs of pharmaceuticals, and promoting lifestyle interventions that prevent or ameliorate obesity and other factors contributing to diabetes and heart disease.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel, MD, is provost of the department of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine and in the department of health care management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported receiving speaking fees from numerous industry sources. Dr. Emanuel made these remarks in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Dieleman’s report (JAMA 2016;316:2604-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16739).

Diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and back and neck pain are the top three conditions accounting for the highest spending on personal health care in the United States, according to a report published online Dec. 27 in JAMA.

In addition, spending on pharmaceuticals – particularly diabetes therapies, antihypertensive drugs, and medications for hyperlipidemia – drove much of the massive increase in health care spending during the past 2 decades, said Joseph L. Dieleman, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, and his associates.

Recent increases in health care spending are well documented, but less is known about what is spent for individual conditions, in different health care settings, and in various patient age groups. To assess health care spending across these categories, the investigators collected and analyzed data for 1996 through 2013 from nationally representative surveys of households, nationally representative surveys of medical facilities, insurance claims, government budgets, and other official records.

They grouped the data into six type-of-care categories: inpatient care, ambulatory care, emergency department care, nursing facility care, dental care, and prescribed pharmaceuticals. “Spending on the six types of personal health care was then disaggregated across 155 mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive conditions and 38 age and sex groups,” with each sex being divided into 5-year age groups, the researchers noted.

Based on these data, the investigators came to the following conclusions:

• Twenty conditions accounted for approximately 58% of personal health care spending, which totaled an estimated $1.2 trillion in 2013.

• More resources were spent on diabetes than any other condition in 2013, at an estimated $101.4 billion. Prescribed medications accounted for nearly 60% of diabetes costs.

• The second-highest amount of health care spending was for ischemic heart disease, which accounted for $88.1 billion in 2013. Most such spending occurred in inpatient settings.

• Low-back and neck pain, comprising the third-highest level of spending, cost an estimated $87.6 billion. Approximately 60% of this spending occurred in ambulatory settings.

• Among all 155 conditions, spending for diabetes and low-back and neck pain increased the most during the 18-year study period.

• Among all six types of care, spending on pharmaceuticals and emergency care increased the most during the study period.

It is important to note that for the purposes of this study, cancer was disaggregated into 29 separate conditions, and none of them placed in the top 20 for health care spending, Dr. Dieleman and his associates noted (JAMA. 2016;316[24]:2627-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16885).

When spending was categorized by patient age groups, working-age adults accounted for the greatest amount spent in 2013, estimated at $1,070.1 billion. But that was followed closely by patients aged 65 and older, who accounted for an estimated $796.5 billion, much of which was spent on care in nursing facilities. The smallest amount of health care spending was in children over age 1 and adolescents, who accounted for an estimated $233.5 billion.

Among the other study findings:

• Spending on pharmaceutical treatment of two conditions, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, increased at more than double the rate of total health care spending. It totaled an estimated $135.7 billion in 2013.

• Other top-20 conditions included falls, depression, skin disorders such as acne and eczema, sense disorders such as vision correction and hearing loss, dental care, urinary disorders, and lower respiratory tract infection.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Vitality Institute. Dr. Dieleman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and back and neck pain are the top three conditions accounting for the highest spending on personal health care in the United States, according to a report published online Dec. 27 in JAMA.

In addition, spending on pharmaceuticals – particularly diabetes therapies, antihypertensive drugs, and medications for hyperlipidemia – drove much of the massive increase in health care spending during the past 2 decades, said Joseph L. Dieleman, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, University of Washington, Seattle, and his associates.

Recent increases in health care spending are well documented, but less is known about what is spent for individual conditions, in different health care settings, and in various patient age groups. To assess health care spending across these categories, the investigators collected and analyzed data for 1996 through 2013 from nationally representative surveys of households, nationally representative surveys of medical facilities, insurance claims, government budgets, and other official records.

They grouped the data into six type-of-care categories: inpatient care, ambulatory care, emergency department care, nursing facility care, dental care, and prescribed pharmaceuticals. “Spending on the six types of personal health care was then disaggregated across 155 mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive conditions and 38 age and sex groups,” with each sex being divided into 5-year age groups, the researchers noted.

Based on these data, the investigators came to the following conclusions:

• Twenty conditions accounted for approximately 58% of personal health care spending, which totaled an estimated $1.2 trillion in 2013.

• More resources were spent on diabetes than any other condition in 2013, at an estimated $101.4 billion. Prescribed medications accounted for nearly 60% of diabetes costs.

• The second-highest amount of health care spending was for ischemic heart disease, which accounted for $88.1 billion in 2013. Most such spending occurred in inpatient settings.

• Low-back and neck pain, comprising the third-highest level of spending, cost an estimated $87.6 billion. Approximately 60% of this spending occurred in ambulatory settings.

• Among all 155 conditions, spending for diabetes and low-back and neck pain increased the most during the 18-year study period.

• Among all six types of care, spending on pharmaceuticals and emergency care increased the most during the study period.

It is important to note that for the purposes of this study, cancer was disaggregated into 29 separate conditions, and none of them placed in the top 20 for health care spending, Dr. Dieleman and his associates noted (JAMA. 2016;316[24]:2627-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16885).

When spending was categorized by patient age groups, working-age adults accounted for the greatest amount spent in 2013, estimated at $1,070.1 billion. But that was followed closely by patients aged 65 and older, who accounted for an estimated $796.5 billion, much of which was spent on care in nursing facilities. The smallest amount of health care spending was in children over age 1 and adolescents, who accounted for an estimated $233.5 billion.

Among the other study findings:

• Spending on pharmaceutical treatment of two conditions, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, increased at more than double the rate of total health care spending. It totaled an estimated $135.7 billion in 2013.

• Other top-20 conditions included falls, depression, skin disorders such as acne and eczema, sense disorders such as vision correction and hearing loss, dental care, urinary disorders, and lower respiratory tract infection.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Vitality Institute. Dr. Dieleman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: More resources were spent on diabetes than any other condition in 2013, at an estimated $101.4 billion.

Data source: A comprehensive estimate of U.S. spending on personal health care, based on information collected from nationally representative surveys of households and medical facilities, government budgets, insurance claims, and official records from 1996 through 2013.

Disclosures: The National Institute on Aging and the Vitality Institute supported the work. Dr. Dieleman and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Prepregnancy overweight boosts risk of depressive symptoms in pregnancy

NEW ORLEANS – Prepregnancy overweight and obesity are associated with increased incidence and severity of depressive symptoms during pregnancy, independent of preeclampsia and other hypertensive pregnancy disorders or gestational diabetes, Satu Kumpulainen reported at Obesity Week 2016.

The implications of this novel finding are clear: “Prepregnancy interventions targeting overweight and obesity and mental health will not only benefit the pregnant mother’s health but will also provide optimal odds for healthy development of the fetus as well,” said Ms. Kumpulainen, a doctoral student at the University of Helsinki Institute of Behavioral Sciences.

It’s well established that prepregnancy obesity is a risk factor for gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and depression during pregnancy. This study was carried out to learn if a high prepregnancy BMI boosts the risk of prenatal depression independent of the cardiometabolic complications of pregnancy, Ms. Kumpulainen explained at the meeting, which was presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

This proved to be the case in the Finnish women, 67.3% of whom were normal weight before pregnancy; 19.1% were overweight and 13.6% obese. Gestational diabetes occurred in 10.6% of the PREDO participants, and hypertension-spectrum disorders of pregnancy occurred in 8.2%.

The women who were obese or overweight prepregnancy reported higher rates of clinically meaningful depressive symptoms throughout pregnancy, compared with women who were normal weight. Using a CES-D score of 16 or more to define clinically significant depressive symptoms, such symptoms were reported as early as gestational week 12 and on multiple occasions thereafter by 19.9% of the women who were normal weight before pregnancy, 23.3% of those who were overweight, and 27.4% of those who were obese. The differences were statistically significant.

The risk of clinically significant depressive symptoms during pregnancy was no higher in prepregnancy normal-weight women who developed gestational diabetes or preeclampsia than in those who did not, Ms. Kumpulainen reported.

“Our findings suggest that cardiometabolic pregnancy disorders per se don’t trigger higher levels of depressive symptoms, but women with prepregnancy overweight and obesity feel more depressed right from the beginning of pregnancy,” Ms. Kumpulainen said.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest related to the study, which was supported by Finnish scientific research grants.

NEW ORLEANS – Prepregnancy overweight and obesity are associated with increased incidence and severity of depressive symptoms during pregnancy, independent of preeclampsia and other hypertensive pregnancy disorders or gestational diabetes, Satu Kumpulainen reported at Obesity Week 2016.

The implications of this novel finding are clear: “Prepregnancy interventions targeting overweight and obesity and mental health will not only benefit the pregnant mother’s health but will also provide optimal odds for healthy development of the fetus as well,” said Ms. Kumpulainen, a doctoral student at the University of Helsinki Institute of Behavioral Sciences.

It’s well established that prepregnancy obesity is a risk factor for gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and depression during pregnancy. This study was carried out to learn if a high prepregnancy BMI boosts the risk of prenatal depression independent of the cardiometabolic complications of pregnancy, Ms. Kumpulainen explained at the meeting, which was presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

This proved to be the case in the Finnish women, 67.3% of whom were normal weight before pregnancy; 19.1% were overweight and 13.6% obese. Gestational diabetes occurred in 10.6% of the PREDO participants, and hypertension-spectrum disorders of pregnancy occurred in 8.2%.

The women who were obese or overweight prepregnancy reported higher rates of clinically meaningful depressive symptoms throughout pregnancy, compared with women who were normal weight. Using a CES-D score of 16 or more to define clinically significant depressive symptoms, such symptoms were reported as early as gestational week 12 and on multiple occasions thereafter by 19.9% of the women who were normal weight before pregnancy, 23.3% of those who were overweight, and 27.4% of those who were obese. The differences were statistically significant.

The risk of clinically significant depressive symptoms during pregnancy was no higher in prepregnancy normal-weight women who developed gestational diabetes or preeclampsia than in those who did not, Ms. Kumpulainen reported.

“Our findings suggest that cardiometabolic pregnancy disorders per se don’t trigger higher levels of depressive symptoms, but women with prepregnancy overweight and obesity feel more depressed right from the beginning of pregnancy,” Ms. Kumpulainen said.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest related to the study, which was supported by Finnish scientific research grants.

NEW ORLEANS – Prepregnancy overweight and obesity are associated with increased incidence and severity of depressive symptoms during pregnancy, independent of preeclampsia and other hypertensive pregnancy disorders or gestational diabetes, Satu Kumpulainen reported at Obesity Week 2016.

The implications of this novel finding are clear: “Prepregnancy interventions targeting overweight and obesity and mental health will not only benefit the pregnant mother’s health but will also provide optimal odds for healthy development of the fetus as well,” said Ms. Kumpulainen, a doctoral student at the University of Helsinki Institute of Behavioral Sciences.

It’s well established that prepregnancy obesity is a risk factor for gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and depression during pregnancy. This study was carried out to learn if a high prepregnancy BMI boosts the risk of prenatal depression independent of the cardiometabolic complications of pregnancy, Ms. Kumpulainen explained at the meeting, which was presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

This proved to be the case in the Finnish women, 67.3% of whom were normal weight before pregnancy; 19.1% were overweight and 13.6% obese. Gestational diabetes occurred in 10.6% of the PREDO participants, and hypertension-spectrum disorders of pregnancy occurred in 8.2%.

The women who were obese or overweight prepregnancy reported higher rates of clinically meaningful depressive symptoms throughout pregnancy, compared with women who were normal weight. Using a CES-D score of 16 or more to define clinically significant depressive symptoms, such symptoms were reported as early as gestational week 12 and on multiple occasions thereafter by 19.9% of the women who were normal weight before pregnancy, 23.3% of those who were overweight, and 27.4% of those who were obese. The differences were statistically significant.

The risk of clinically significant depressive symptoms during pregnancy was no higher in prepregnancy normal-weight women who developed gestational diabetes or preeclampsia than in those who did not, Ms. Kumpulainen reported.

“Our findings suggest that cardiometabolic pregnancy disorders per se don’t trigger higher levels of depressive symptoms, but women with prepregnancy overweight and obesity feel more depressed right from the beginning of pregnancy,” Ms. Kumpulainen said.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest related to the study, which was supported by Finnish scientific research grants.

AT OBESITY WEEK 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Women who were obese prior to pregnancy were over 50% more likely to experience clinically significant depressive symptoms throughout pregnancy, compared with women who were normal weight before pregnancy, independent of whether the women developed gestational diabetes or preeclampsia.

Data source: This was a secondary analysis from a prospective study of more than 3,000 pregnant Finnish women.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Finnish scientific research grants. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest related to the study.

Unless it is diagnosed, obesity won’t be treated

NEW ORLEANS – Obesity has been formally diagnosed in less than half of patients with a body-mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher in the Cleveland Clinic’s large multispecialty database, and Bartolome Burguera, MD, believes it’s the same story elsewhere.

“I think pretty much all over the country obesity is really not well diagnosed,” Dr. Burguera, director of obesity programs at the Cleveland Clinic, said at Obesity Week 2016.

And that which hasn’t been diagnosed doesn’t get treated.

The diagnosis rate went up with higher BMIs; still, of the 25,137 patients with obesity class 3 as defined by a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or higher, only 75% had a formal diagnosis of obesity in their record, the endocrinologist said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“For many years, physicians thought that obesity is not a disease. And even though it was considered a disease by some, they didn’t feel they had the tools, the knowledge, the support, the medications, or the time to take care of obesity, especially when they thought of it as a self-inflicted disease,” Dr. Burguera explained in an interview. He believes physician attitudes are slowly changing.

“In our clinic we’ve taken measures to change attitudes, for sure. Now, when we look in the electronic health record we get an automatic alert if the patient has a BMI of 30 or more,” he said.

“I think, in general, many more people now think of obesity as a disease. But it’s a chronic disease and you have to have chronic therapy. We have to make sure we make the diagnosis, and once you make the diagnosis you have to discuss treatment with the patient. If you don’t feel comfortable for whatever reason, I think you have to refer the patient to a colleague to take care of the obesity. Because when you take care of the obesity all the comorbidities get better: the diabetes, the blood pressure, the cholesterol. Obesity is the primary problem in so many other comorbidities. We have put little effort to this point in taking care of the obesity. We’ve put more effort into treating the diabetes and the other comorbidities,” Dr. Burguera said.

The Medicare obesity benefit provides reimbursement in primary care settings for intensive behavioral therapy with face-to-face counseling and motivational interviewing. The billing code is G0447. Coverage is provided for 22 visits over the course of a year, each lasting 15 minutes.

Dr. Batsis presented highlights of his published serial cross-sectional analysis of fee-for-service Medicare claims data for 2012 and 2013. Among Medicare beneficiaries eligible for the obesity benefit because they had a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or above, only 0.35% used the benefit in 2012. There was a tiny uptick to 0.6% in 2013, but even in the tiny fraction of eligible patients who availed themselves of the benefit, the average number of behavioral therapy sessions was just 2.1 visits out of the 22 for which physician reimbursement is available (Obesity. 2016 Sep;24[9]:1983-8).

“Let’s hope the 2014 data look a little better,” commented Dr. Batsis of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice in Lebanon, N.H.

There was marked regional variation in utilization of the Medicare obesity benefit across the U.S. in 2013. Rates were highest in Colorado – the state with the lowest obesity rate in the country – as well as Nebraska, Wisconsin, Vermont, and New Hampshire. Rates were lowest across the Southwest.

Dr. Burguera’s study was funded by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Batsis reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

NEW ORLEANS – Obesity has been formally diagnosed in less than half of patients with a body-mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher in the Cleveland Clinic’s large multispecialty database, and Bartolome Burguera, MD, believes it’s the same story elsewhere.

“I think pretty much all over the country obesity is really not well diagnosed,” Dr. Burguera, director of obesity programs at the Cleveland Clinic, said at Obesity Week 2016.

And that which hasn’t been diagnosed doesn’t get treated.