User login

A Veteran With Recurrent, Painful Knee Effusion

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old Air Force veteran was admitted to the US Department of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) for evaluation of recurrent, painful right knee effusions. On presentation, his vital signs were stable, and the examination was significant for a right knee with a large effusion and tenderness to palpation without erythema or warmth. His white blood cell count was 12.0 cells/L with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 23 mm/h and C-reactive protein of 11.87 mg/L. He was in remission from alcohol use but had relapsed on alcohol in the past day to treat the pain. He had a history of IV drug use but was in remission. He was previously active and enjoyed long hikes. Nine months prior to presentation, he developed his first large right knee effusion associated with pain. He reported no antecedent trauma. At that time, he presented to another hospital and underwent arthrocentesis with orthopedic surgery, but this did not lead to a diagnosis, and the effusion reaccumulated within 24 hours. Four months later, he received a corticosteroid injection that provided only minor, temporary relief. He received 5 additional arthrocenteses over 9 months, all without definitive diagnosis and with rapid reaccumulation of the fluid. His most recent arthrocentesis was 3 weeks before admission.

►Lauren E. Merz, MD, MSc, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS: Dr. Jindal, what is your approach and differential diagnosis for joint effusions in hospitalized patients?

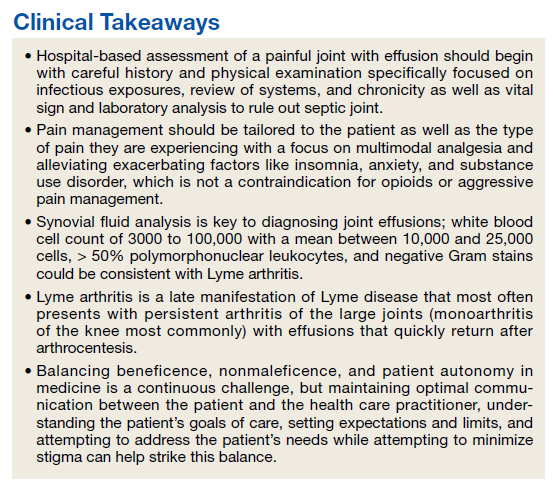

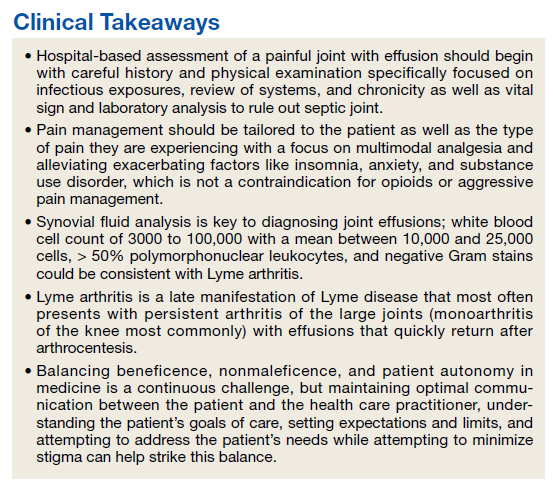

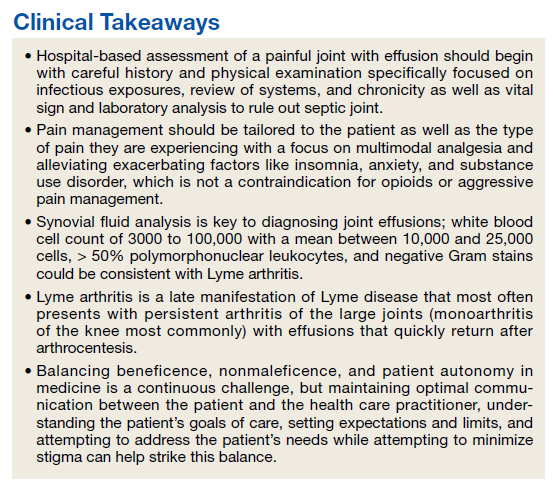

►Shivani Jindal, MD, MPH, Hospitalist, VABHS, Instructor in Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM): A thorough history and physical examination are important. I specifically ask about chronicity, pain, and trauma. A medical history of potential infectious exposures and the history of the present illness are also important, such as the risk of sexually transmitted infections, exposure to Lyme disease or other viral illnesses. Gonococcal arthritis is one of the most common causes of nontraumatic monoarthritis in young adults but can also present as a migratory polyarthritis.1

It sounds like he was quite active and liked to hike so a history of tick exposure is important to ascertain. I would also ask about eye inflammation and back pain to assess possible ankylosing spondyarthritis. Other inflammatory etiologies, such as gout are common, but it would be surprising to miss this diagnosis on repeated arthocenteses. A physical examination can confirm monoarthritis over polyarthritis and assess for signs of inflammatory arthritis (eg, warmth and erythema). The most important etiology to assess for and rule out in a person admitted to the hospital is septic arthritis. The severe pain, mild leukocytosis, and mildly elevated inflammatory markers could be consistent with this diagnosis but are nonspecific. However, the chronicity of this patient’s presentation and hemodynamic stability make septic arthritis less likely overall and a more indolent infection or other inflammatory process more likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient’s medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and antisocial personality disorder with multiple prior suicide attempts. He also had a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) with prior overdose and alcohol use disorder (AUD). Given his stated preference to avoid opioids and normal liver function and liver chemistry testing, the initial treatment was with acetaminophen. After this failed to provide satisfactory pain control, IV hydromorphone was added.

Dr. Jindal, how do you approach pain control in the hospital for musculoskeletal issues like this?

►Dr. Jindal: Typically, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are most effective for musculoskeletal pain, often in the form of ketorolac or ibuprofen. However, we are often limited in our NSAID use by kidney disease, gastritis, or cardiovascular disease.

►Dr. Merz: On hospital day 1, the patient asked to leave to consume alcohol to ease unremitting pain. He also expressed suicidal ideation and discharge was therefore felt to be unsafe. He was reluctant to engage with psychiatry and became physically combative while attempting to leave the hospital, necessitating the use of sedating medications and physical restraints.

Dr. Shahal, what factors led to the decision to place an involuntary hold, and how do you balance patient autonomy and patient safety?

►Dr. Talya Shahal, MD, Consult-Liaison Psychiatry Service, VABHS, Instructor in Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School: This is a delicate balance that requires constant reassessment. The patient initially presented to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, stating he was not able to tolerate the pain and thus resumed alcohol consumption after a period of nonuse. He had multiple risk factors for suicide, including 9 prior suicide attempts with the latest less than a year before presentation, active substance use with alcohol and other recreational drugs, PTSD, pain, veteran status, male sex, single status, and a history of trauma.3,4 He was also displaying impulsivity and limited insight, did not engage in his psychiatric assessment, and attempted to assault staff. As such, his suicide risk was assessed to be high at the time of the evaluation, which led to the decision to place an involuntary hold. However, we reevaluate this decision at least daily in order to reassess the risk and ensure that the balance between patient safety and autonomy are maintained.

►Dr. Merz: The involuntary hold was removed within 48 hours as the patient remained calm and engaged with the primary and consulting teams. He requested escalating doses of opioids as he felt the short-acting IV medications were not providing sustained relief. However, he was also noted to be walking outside of the hospital without assistance, and he repeatedly declined nonopioid pain modalities as well as buprenorphine/naloxone. The chronic pain service was consulted but was unable to see the patient as he was frequently outside of his room.

Dr. Shahal, how do you address OUD, pain, and stigma in the hospital?

►Dr. Shahal: It is important to remember that patients with substance use disorder (SUD) and mental illness frequently have physical causes for pain and are often undertreated.5 Patients with SUD may also have higher tolerance for opioids and may need higher doses to treat the pain.5 Modalities like buprenorphine/naloxone can be effective to treat OUD and pain, but these usually cannot be initiated while the patient is on short-acting opioids as this would precipitate withdrawal.6 However, withdrawal can be managed while inpatient, and this can be a good time to start these medications as practitioners can aggressively help with symptom control. Proactively addressing mental health concerns, particularly anxiety, AUD, insomnia, PTSD, and depression, can also have a direct impact on the perception of pain and assist with better control.2 In addition, nonpharmacologic options, such as meditation, deep breathing, and even acupuncture and Reiki can be helpful and of course less harmful to treat pain.2

► Dr. Merz: An X-ray of the knee showed no acute fracture or joint space narrowing. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a large knee effusion with no evidence of ligament injury. Synovial fluid showed turbid, yellow fluid with 14,110 nucleated cells (84% segmented cells and 4000 RBCs). Gram stain was negative, culture had no growth, and there were no crystals. Anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), rheumatoid factor, HIV testing, and HLA-B27 were negative.

Dr. Serrao, what do these studies tell us about the joint effusion and the possible diagnoses?

► Dr. Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, Clinical Associate Professor in Medicine, BUSM: I would expect the white blood cell (WBC) count to be > 50,000 cells with > 75% polymorphonuclear cells and a positive Gram stain if this was a bacterial infection resulting in septic arthritis.7 This patient’s studies are not consistent with this diagnosis nor is the chronicity of his presentation. There are 2 important bacteria that can present with inflammatory arthritis and less pronounced findings on arthrocentesis: Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacteria causing Lyme arthritis) and Neisseria gonorrhea. Lyme arthritis could be consistent with this relapsing remitting presentation as you expect a WBC count between 3000 and 100,000 cells with a mean value between 10,000 and 25,000 cells, > 50% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and negative Gram stains.8 Gonococcal infections often do not have marked elevations in the WBC count and the Gram stain can be variable, but you still expect the WBC count to be > 30,000 cells.7 Inflammatory causes such as gout or autoimmune conditions such as lupus often have a WBC count between 2000 and 100,000 with a negative Gram stain, which could be consistent with this patient’s presentation.7 However, the lack of crystals rules out gout and the negative anti-CCP, rheumatoid factor, and HLA-B27 make rheumatologic diseases less likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient received a phone call from another hospital where an arthrocentesis had been performed 3 weeks before. The results included a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for Lyme disease in the synovial fluid. A subsequent serum Lyme screen was positive for 1 of 3 immunoglobulin (Ig) M bands and 10 of 10 IgG bands.

Dr. Serrao, how does Lyme arthritis typically present, and are there aspects of this case that make you suspect the diagnosis? Does the serum Lyme test give us any additional information?

►Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of Lyme disease. Patients typically have persistent or intermittent arthritis, and large joints are more commonly impacted than small joints. Monoarthritis of the knee is the most common, but oligoarthritis is possible as well. The swelling usually begins abruptly, lasts for weeks to months, and effusions typically recur quickly after aspiration. These findings are consistent with the patient’s clinical history.

For diagnostics, the IgG Western blot is positive if 5 of the 10 bands are positive.9 This patient far exceeds the IgG band number to diagnose Lyme disease. All patients with Lyme arthritis will have positive IgG serologies since Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of the infection. IgM reactivity may be present, but are not necessary to diagnose Lyme arthritis.10 Synovial fluid is often not analyzed for antibody responses as they are susceptible to false positive results, but synovial PCR testing like this patient had detects approximately 70% of patients with untreated Lyme arthritis.11 However, PCR positivity does not necessarily equate with active infection. Serologic testing for Lyme disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot as well as careful history and the exclusion of other diagnoses are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.

► Dr. Merz: On further history the patient reported that 5 years prior he found a tick on his skin with a bull’s-eye rash. He was treated with 28 days of doxycycline at that time. He did not recall any tick bites or rashes in the years since.

Dr. Serrao, is it surprising that he developed Lyme arthritis 5 years after exposure and after being treated appropriately? What is the typical treatment approach for a patient like this?

►Dr. Serrao: It is atypical to develop Lyme arthritis 5 years after reported treatment of what appeared to be early localized disease, namely, erythema migrans. This stage is usually cured with 10 days of treatment alone (he received 28 days) and is generally abortive of subsequent stages, including Lyme arthritis. Furthermore, the patient reported no symptoms of arthritis until recently since that time. Therefore, one can argue that the excessively long span of time from treatment to these first episodes of arthritis suggests the patient could have been reinfected. When available, comparing the types and number of Western blot bands (eg, new and/or more bands on subsequent serologic testing) can support a reinfection diagnosis. A delayed postinfectious inflammatory process from excessive proinflammatory immune responses that block wound repair resulting in proliferative synovitis is also possible.12 This is defined as the postinfectious, postantibiotic, or antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis, a diagnosis of exclusion more apparent only after patients receive appropriate antibiotic courses for the possibility of untreated Lyme as an active infection.12

Given the inherent diagnostic uncertainty between an active infection and posttreatment Lyme arthritis syndromes, it is best to approach most cases of Lyme arthritis as an active infection first especially if not yet treated with antibiotics. Diagnosis of postinflammatory processes should be considered if symptoms persist after appropriate antibiotics, and then short-term use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, rather than further courses of antibiotics, is recommended.

► Dr. Merz: The patient was initiated on doxycycline with the plan to transition to ceftriaxone if there was no response. One day after diagnosis and treatment initiation and in the setting of continued pain, the patient again asked to leave the hospital to drink alcohol. After eloping and becoming intoxicated with alcohol, he returned to his room. He remained concerned about his continued pain and lack of adequate pain control. At the time, he was receiving hydromorphone, ketorolac, lorazepam, gabapentin, and quetiapine.

Dr. Serrao, do you expect this degree of pain from Lyme arthritis?

► Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is typically less painful than other forms of infectious or inflammatory arthritis. Pain is usually caused by the pressure from the acute accumulation and reaccumulation of fluid. In this case, the rapid accumulation of fluid that this patient experienced as well as relief with arthrocentesis suggests that the size and acuity of the effusion was causing great discomfort. Repeated arthrocentesis can prove to be a preventative strategy to minimize synovial herniation.

►Dr. Merz: Dr. Shahal, how do you balance the patient subjectively telling you that they are in pain with objective signs that they may be tolerating the pain like walking around unassisted? Is there anything else that could have been done to prevent this adverse outcome?

►Dr. Shahal: This is one of the hardest pieces of pain management. We want to practice beneficence by believing our patients and addressing their discomfort, but we also want to practice nonmaleficence by avoiding inappropriate long-term pain treatments like opioids that have significant harm as well as avoiding exacerbating this patient’s underlying SUD. An agent like buprenorphine/naloxone could have been an excellent fit to treat pain and SUD, but the patient’s lack of interest and the frequent use of short-acting opioids were major barriers. A chronic pain consult early on is helpful in cases like this as well, but they were unable to see him since he was often out of his room. Repeated arthrocentesis may also have helped the pain. Treatment of anxiety and insomnia with medications like hydroxyzine, trazodone, melatonin, gabapentin, or buspirone as well as interventions like sleep hygiene protocols or spiritual care may have helped somewhat as well.

We know that there is a vicious cycle between pain and poorly controlled mood symptoms. Many of our veterans have PTSD, anxiety, and SUD that are exacerbated by hospitalization and pain. Maintaining optimal communication between the patient and the practitioners, using trauma-informed care, understanding the patient’s goals of care, setting expectations and limits, and attempting to address the patient’s needs while attempting to minimize stigma might be helpful. However, despite optimal care, sometimes these events cannot be avoided.

►Dr. Merz: The patient was ultimately transferred to an inpatient psychiatric unit where a taper plan for the short-acting opioids was implemented. He was psychiatrically stabilized and discharged a few days later off opioids and on doxycycline. On follow-up a few weeks later, his pain had markedly improved, and the effusion was significantly reduced in size. His mood and impulsivity had stabilized. He continues to follow-up in the infectious disease clinic.

1. Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, Brasington R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):83-90.

2. Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: a clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):739-748. doi:10.7326/M19-3602

3. Silverman MM, Berman AL. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part I: a focus on suicide ideation in assessing suicide risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):420-431. doi:10.1111/sltb.12065

4. Berman AL, Silverman MM. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part II: Suicide risk formulation and the determination of levels of risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):432-443. doi:10.1111/sltb.12067

5. Quinlan J, Cox F. Acute pain management in patients with drug dependence syndrome. Pain Rep. 2017;2(4):e611. Published 2017 Jul 27. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000611

6. Chou R, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, et al. Treatments for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566506/

7. Seidman AJ, Limaiem F. Synovial fluid analysis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537114

8. Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(2):269-280. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.004

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. JAMA. 1995;274(12):937.

10. Craft JE, Grodzicki RL, Steere AC. Antibody response in Lyme disease: evaluation of diagnostic tests. J Infect Dis. 1984;149(5):789-795. doi:10.1093/infdis/149.5.789

11. Nocton JJ, Dressler F, Rutledge BJ, Rys PN, Persing DH, Steere AC. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid from patients with Lyme arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(4):229-234. doi:10.1056/NEJM199401273300401

12. Steere AC. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndromes: distinct pathogenesis caused by maladaptive host responses. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2148-2151. doi:10.1172/JCI138062

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old Air Force veteran was admitted to the US Department of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) for evaluation of recurrent, painful right knee effusions. On presentation, his vital signs were stable, and the examination was significant for a right knee with a large effusion and tenderness to palpation without erythema or warmth. His white blood cell count was 12.0 cells/L with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 23 mm/h and C-reactive protein of 11.87 mg/L. He was in remission from alcohol use but had relapsed on alcohol in the past day to treat the pain. He had a history of IV drug use but was in remission. He was previously active and enjoyed long hikes. Nine months prior to presentation, he developed his first large right knee effusion associated with pain. He reported no antecedent trauma. At that time, he presented to another hospital and underwent arthrocentesis with orthopedic surgery, but this did not lead to a diagnosis, and the effusion reaccumulated within 24 hours. Four months later, he received a corticosteroid injection that provided only minor, temporary relief. He received 5 additional arthrocenteses over 9 months, all without definitive diagnosis and with rapid reaccumulation of the fluid. His most recent arthrocentesis was 3 weeks before admission.

►Lauren E. Merz, MD, MSc, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS: Dr. Jindal, what is your approach and differential diagnosis for joint effusions in hospitalized patients?

►Shivani Jindal, MD, MPH, Hospitalist, VABHS, Instructor in Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM): A thorough history and physical examination are important. I specifically ask about chronicity, pain, and trauma. A medical history of potential infectious exposures and the history of the present illness are also important, such as the risk of sexually transmitted infections, exposure to Lyme disease or other viral illnesses. Gonococcal arthritis is one of the most common causes of nontraumatic monoarthritis in young adults but can also present as a migratory polyarthritis.1

It sounds like he was quite active and liked to hike so a history of tick exposure is important to ascertain. I would also ask about eye inflammation and back pain to assess possible ankylosing spondyarthritis. Other inflammatory etiologies, such as gout are common, but it would be surprising to miss this diagnosis on repeated arthocenteses. A physical examination can confirm monoarthritis over polyarthritis and assess for signs of inflammatory arthritis (eg, warmth and erythema). The most important etiology to assess for and rule out in a person admitted to the hospital is septic arthritis. The severe pain, mild leukocytosis, and mildly elevated inflammatory markers could be consistent with this diagnosis but are nonspecific. However, the chronicity of this patient’s presentation and hemodynamic stability make septic arthritis less likely overall and a more indolent infection or other inflammatory process more likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient’s medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and antisocial personality disorder with multiple prior suicide attempts. He also had a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) with prior overdose and alcohol use disorder (AUD). Given his stated preference to avoid opioids and normal liver function and liver chemistry testing, the initial treatment was with acetaminophen. After this failed to provide satisfactory pain control, IV hydromorphone was added.

Dr. Jindal, how do you approach pain control in the hospital for musculoskeletal issues like this?

►Dr. Jindal: Typically, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are most effective for musculoskeletal pain, often in the form of ketorolac or ibuprofen. However, we are often limited in our NSAID use by kidney disease, gastritis, or cardiovascular disease.

►Dr. Merz: On hospital day 1, the patient asked to leave to consume alcohol to ease unremitting pain. He also expressed suicidal ideation and discharge was therefore felt to be unsafe. He was reluctant to engage with psychiatry and became physically combative while attempting to leave the hospital, necessitating the use of sedating medications and physical restraints.

Dr. Shahal, what factors led to the decision to place an involuntary hold, and how do you balance patient autonomy and patient safety?

►Dr. Talya Shahal, MD, Consult-Liaison Psychiatry Service, VABHS, Instructor in Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School: This is a delicate balance that requires constant reassessment. The patient initially presented to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, stating he was not able to tolerate the pain and thus resumed alcohol consumption after a period of nonuse. He had multiple risk factors for suicide, including 9 prior suicide attempts with the latest less than a year before presentation, active substance use with alcohol and other recreational drugs, PTSD, pain, veteran status, male sex, single status, and a history of trauma.3,4 He was also displaying impulsivity and limited insight, did not engage in his psychiatric assessment, and attempted to assault staff. As such, his suicide risk was assessed to be high at the time of the evaluation, which led to the decision to place an involuntary hold. However, we reevaluate this decision at least daily in order to reassess the risk and ensure that the balance between patient safety and autonomy are maintained.

►Dr. Merz: The involuntary hold was removed within 48 hours as the patient remained calm and engaged with the primary and consulting teams. He requested escalating doses of opioids as he felt the short-acting IV medications were not providing sustained relief. However, he was also noted to be walking outside of the hospital without assistance, and he repeatedly declined nonopioid pain modalities as well as buprenorphine/naloxone. The chronic pain service was consulted but was unable to see the patient as he was frequently outside of his room.

Dr. Shahal, how do you address OUD, pain, and stigma in the hospital?

►Dr. Shahal: It is important to remember that patients with substance use disorder (SUD) and mental illness frequently have physical causes for pain and are often undertreated.5 Patients with SUD may also have higher tolerance for opioids and may need higher doses to treat the pain.5 Modalities like buprenorphine/naloxone can be effective to treat OUD and pain, but these usually cannot be initiated while the patient is on short-acting opioids as this would precipitate withdrawal.6 However, withdrawal can be managed while inpatient, and this can be a good time to start these medications as practitioners can aggressively help with symptom control. Proactively addressing mental health concerns, particularly anxiety, AUD, insomnia, PTSD, and depression, can also have a direct impact on the perception of pain and assist with better control.2 In addition, nonpharmacologic options, such as meditation, deep breathing, and even acupuncture and Reiki can be helpful and of course less harmful to treat pain.2

► Dr. Merz: An X-ray of the knee showed no acute fracture or joint space narrowing. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a large knee effusion with no evidence of ligament injury. Synovial fluid showed turbid, yellow fluid with 14,110 nucleated cells (84% segmented cells and 4000 RBCs). Gram stain was negative, culture had no growth, and there were no crystals. Anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), rheumatoid factor, HIV testing, and HLA-B27 were negative.

Dr. Serrao, what do these studies tell us about the joint effusion and the possible diagnoses?

► Dr. Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, Clinical Associate Professor in Medicine, BUSM: I would expect the white blood cell (WBC) count to be > 50,000 cells with > 75% polymorphonuclear cells and a positive Gram stain if this was a bacterial infection resulting in septic arthritis.7 This patient’s studies are not consistent with this diagnosis nor is the chronicity of his presentation. There are 2 important bacteria that can present with inflammatory arthritis and less pronounced findings on arthrocentesis: Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacteria causing Lyme arthritis) and Neisseria gonorrhea. Lyme arthritis could be consistent with this relapsing remitting presentation as you expect a WBC count between 3000 and 100,000 cells with a mean value between 10,000 and 25,000 cells, > 50% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and negative Gram stains.8 Gonococcal infections often do not have marked elevations in the WBC count and the Gram stain can be variable, but you still expect the WBC count to be > 30,000 cells.7 Inflammatory causes such as gout or autoimmune conditions such as lupus often have a WBC count between 2000 and 100,000 with a negative Gram stain, which could be consistent with this patient’s presentation.7 However, the lack of crystals rules out gout and the negative anti-CCP, rheumatoid factor, and HLA-B27 make rheumatologic diseases less likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient received a phone call from another hospital where an arthrocentesis had been performed 3 weeks before. The results included a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for Lyme disease in the synovial fluid. A subsequent serum Lyme screen was positive for 1 of 3 immunoglobulin (Ig) M bands and 10 of 10 IgG bands.

Dr. Serrao, how does Lyme arthritis typically present, and are there aspects of this case that make you suspect the diagnosis? Does the serum Lyme test give us any additional information?

►Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of Lyme disease. Patients typically have persistent or intermittent arthritis, and large joints are more commonly impacted than small joints. Monoarthritis of the knee is the most common, but oligoarthritis is possible as well. The swelling usually begins abruptly, lasts for weeks to months, and effusions typically recur quickly after aspiration. These findings are consistent with the patient’s clinical history.

For diagnostics, the IgG Western blot is positive if 5 of the 10 bands are positive.9 This patient far exceeds the IgG band number to diagnose Lyme disease. All patients with Lyme arthritis will have positive IgG serologies since Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of the infection. IgM reactivity may be present, but are not necessary to diagnose Lyme arthritis.10 Synovial fluid is often not analyzed for antibody responses as they are susceptible to false positive results, but synovial PCR testing like this patient had detects approximately 70% of patients with untreated Lyme arthritis.11 However, PCR positivity does not necessarily equate with active infection. Serologic testing for Lyme disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot as well as careful history and the exclusion of other diagnoses are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.

► Dr. Merz: On further history the patient reported that 5 years prior he found a tick on his skin with a bull’s-eye rash. He was treated with 28 days of doxycycline at that time. He did not recall any tick bites or rashes in the years since.

Dr. Serrao, is it surprising that he developed Lyme arthritis 5 years after exposure and after being treated appropriately? What is the typical treatment approach for a patient like this?

►Dr. Serrao: It is atypical to develop Lyme arthritis 5 years after reported treatment of what appeared to be early localized disease, namely, erythema migrans. This stage is usually cured with 10 days of treatment alone (he received 28 days) and is generally abortive of subsequent stages, including Lyme arthritis. Furthermore, the patient reported no symptoms of arthritis until recently since that time. Therefore, one can argue that the excessively long span of time from treatment to these first episodes of arthritis suggests the patient could have been reinfected. When available, comparing the types and number of Western blot bands (eg, new and/or more bands on subsequent serologic testing) can support a reinfection diagnosis. A delayed postinfectious inflammatory process from excessive proinflammatory immune responses that block wound repair resulting in proliferative synovitis is also possible.12 This is defined as the postinfectious, postantibiotic, or antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis, a diagnosis of exclusion more apparent only after patients receive appropriate antibiotic courses for the possibility of untreated Lyme as an active infection.12

Given the inherent diagnostic uncertainty between an active infection and posttreatment Lyme arthritis syndromes, it is best to approach most cases of Lyme arthritis as an active infection first especially if not yet treated with antibiotics. Diagnosis of postinflammatory processes should be considered if symptoms persist after appropriate antibiotics, and then short-term use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, rather than further courses of antibiotics, is recommended.

► Dr. Merz: The patient was initiated on doxycycline with the plan to transition to ceftriaxone if there was no response. One day after diagnosis and treatment initiation and in the setting of continued pain, the patient again asked to leave the hospital to drink alcohol. After eloping and becoming intoxicated with alcohol, he returned to his room. He remained concerned about his continued pain and lack of adequate pain control. At the time, he was receiving hydromorphone, ketorolac, lorazepam, gabapentin, and quetiapine.

Dr. Serrao, do you expect this degree of pain from Lyme arthritis?

► Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is typically less painful than other forms of infectious or inflammatory arthritis. Pain is usually caused by the pressure from the acute accumulation and reaccumulation of fluid. In this case, the rapid accumulation of fluid that this patient experienced as well as relief with arthrocentesis suggests that the size and acuity of the effusion was causing great discomfort. Repeated arthrocentesis can prove to be a preventative strategy to minimize synovial herniation.

►Dr. Merz: Dr. Shahal, how do you balance the patient subjectively telling you that they are in pain with objective signs that they may be tolerating the pain like walking around unassisted? Is there anything else that could have been done to prevent this adverse outcome?

►Dr. Shahal: This is one of the hardest pieces of pain management. We want to practice beneficence by believing our patients and addressing their discomfort, but we also want to practice nonmaleficence by avoiding inappropriate long-term pain treatments like opioids that have significant harm as well as avoiding exacerbating this patient’s underlying SUD. An agent like buprenorphine/naloxone could have been an excellent fit to treat pain and SUD, but the patient’s lack of interest and the frequent use of short-acting opioids were major barriers. A chronic pain consult early on is helpful in cases like this as well, but they were unable to see him since he was often out of his room. Repeated arthrocentesis may also have helped the pain. Treatment of anxiety and insomnia with medications like hydroxyzine, trazodone, melatonin, gabapentin, or buspirone as well as interventions like sleep hygiene protocols or spiritual care may have helped somewhat as well.

We know that there is a vicious cycle between pain and poorly controlled mood symptoms. Many of our veterans have PTSD, anxiety, and SUD that are exacerbated by hospitalization and pain. Maintaining optimal communication between the patient and the practitioners, using trauma-informed care, understanding the patient’s goals of care, setting expectations and limits, and attempting to address the patient’s needs while attempting to minimize stigma might be helpful. However, despite optimal care, sometimes these events cannot be avoided.

►Dr. Merz: The patient was ultimately transferred to an inpatient psychiatric unit where a taper plan for the short-acting opioids was implemented. He was psychiatrically stabilized and discharged a few days later off opioids and on doxycycline. On follow-up a few weeks later, his pain had markedly improved, and the effusion was significantly reduced in size. His mood and impulsivity had stabilized. He continues to follow-up in the infectious disease clinic.

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old Air Force veteran was admitted to the US Department of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) for evaluation of recurrent, painful right knee effusions. On presentation, his vital signs were stable, and the examination was significant for a right knee with a large effusion and tenderness to palpation without erythema or warmth. His white blood cell count was 12.0 cells/L with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 23 mm/h and C-reactive protein of 11.87 mg/L. He was in remission from alcohol use but had relapsed on alcohol in the past day to treat the pain. He had a history of IV drug use but was in remission. He was previously active and enjoyed long hikes. Nine months prior to presentation, he developed his first large right knee effusion associated with pain. He reported no antecedent trauma. At that time, he presented to another hospital and underwent arthrocentesis with orthopedic surgery, but this did not lead to a diagnosis, and the effusion reaccumulated within 24 hours. Four months later, he received a corticosteroid injection that provided only minor, temporary relief. He received 5 additional arthrocenteses over 9 months, all without definitive diagnosis and with rapid reaccumulation of the fluid. His most recent arthrocentesis was 3 weeks before admission.

►Lauren E. Merz, MD, MSc, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS: Dr. Jindal, what is your approach and differential diagnosis for joint effusions in hospitalized patients?

►Shivani Jindal, MD, MPH, Hospitalist, VABHS, Instructor in Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM): A thorough history and physical examination are important. I specifically ask about chronicity, pain, and trauma. A medical history of potential infectious exposures and the history of the present illness are also important, such as the risk of sexually transmitted infections, exposure to Lyme disease or other viral illnesses. Gonococcal arthritis is one of the most common causes of nontraumatic monoarthritis in young adults but can also present as a migratory polyarthritis.1

It sounds like he was quite active and liked to hike so a history of tick exposure is important to ascertain. I would also ask about eye inflammation and back pain to assess possible ankylosing spondyarthritis. Other inflammatory etiologies, such as gout are common, but it would be surprising to miss this diagnosis on repeated arthocenteses. A physical examination can confirm monoarthritis over polyarthritis and assess for signs of inflammatory arthritis (eg, warmth and erythema). The most important etiology to assess for and rule out in a person admitted to the hospital is septic arthritis. The severe pain, mild leukocytosis, and mildly elevated inflammatory markers could be consistent with this diagnosis but are nonspecific. However, the chronicity of this patient’s presentation and hemodynamic stability make septic arthritis less likely overall and a more indolent infection or other inflammatory process more likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient’s medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and antisocial personality disorder with multiple prior suicide attempts. He also had a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) with prior overdose and alcohol use disorder (AUD). Given his stated preference to avoid opioids and normal liver function and liver chemistry testing, the initial treatment was with acetaminophen. After this failed to provide satisfactory pain control, IV hydromorphone was added.

Dr. Jindal, how do you approach pain control in the hospital for musculoskeletal issues like this?

►Dr. Jindal: Typically, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are most effective for musculoskeletal pain, often in the form of ketorolac or ibuprofen. However, we are often limited in our NSAID use by kidney disease, gastritis, or cardiovascular disease.

►Dr. Merz: On hospital day 1, the patient asked to leave to consume alcohol to ease unremitting pain. He also expressed suicidal ideation and discharge was therefore felt to be unsafe. He was reluctant to engage with psychiatry and became physically combative while attempting to leave the hospital, necessitating the use of sedating medications and physical restraints.

Dr. Shahal, what factors led to the decision to place an involuntary hold, and how do you balance patient autonomy and patient safety?

►Dr. Talya Shahal, MD, Consult-Liaison Psychiatry Service, VABHS, Instructor in Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School: This is a delicate balance that requires constant reassessment. The patient initially presented to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, stating he was not able to tolerate the pain and thus resumed alcohol consumption after a period of nonuse. He had multiple risk factors for suicide, including 9 prior suicide attempts with the latest less than a year before presentation, active substance use with alcohol and other recreational drugs, PTSD, pain, veteran status, male sex, single status, and a history of trauma.3,4 He was also displaying impulsivity and limited insight, did not engage in his psychiatric assessment, and attempted to assault staff. As such, his suicide risk was assessed to be high at the time of the evaluation, which led to the decision to place an involuntary hold. However, we reevaluate this decision at least daily in order to reassess the risk and ensure that the balance between patient safety and autonomy are maintained.

►Dr. Merz: The involuntary hold was removed within 48 hours as the patient remained calm and engaged with the primary and consulting teams. He requested escalating doses of opioids as he felt the short-acting IV medications were not providing sustained relief. However, he was also noted to be walking outside of the hospital without assistance, and he repeatedly declined nonopioid pain modalities as well as buprenorphine/naloxone. The chronic pain service was consulted but was unable to see the patient as he was frequently outside of his room.

Dr. Shahal, how do you address OUD, pain, and stigma in the hospital?

►Dr. Shahal: It is important to remember that patients with substance use disorder (SUD) and mental illness frequently have physical causes for pain and are often undertreated.5 Patients with SUD may also have higher tolerance for opioids and may need higher doses to treat the pain.5 Modalities like buprenorphine/naloxone can be effective to treat OUD and pain, but these usually cannot be initiated while the patient is on short-acting opioids as this would precipitate withdrawal.6 However, withdrawal can be managed while inpatient, and this can be a good time to start these medications as practitioners can aggressively help with symptom control. Proactively addressing mental health concerns, particularly anxiety, AUD, insomnia, PTSD, and depression, can also have a direct impact on the perception of pain and assist with better control.2 In addition, nonpharmacologic options, such as meditation, deep breathing, and even acupuncture and Reiki can be helpful and of course less harmful to treat pain.2

► Dr. Merz: An X-ray of the knee showed no acute fracture or joint space narrowing. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a large knee effusion with no evidence of ligament injury. Synovial fluid showed turbid, yellow fluid with 14,110 nucleated cells (84% segmented cells and 4000 RBCs). Gram stain was negative, culture had no growth, and there were no crystals. Anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), rheumatoid factor, HIV testing, and HLA-B27 were negative.

Dr. Serrao, what do these studies tell us about the joint effusion and the possible diagnoses?

► Dr. Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, Clinical Associate Professor in Medicine, BUSM: I would expect the white blood cell (WBC) count to be > 50,000 cells with > 75% polymorphonuclear cells and a positive Gram stain if this was a bacterial infection resulting in septic arthritis.7 This patient’s studies are not consistent with this diagnosis nor is the chronicity of his presentation. There are 2 important bacteria that can present with inflammatory arthritis and less pronounced findings on arthrocentesis: Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacteria causing Lyme arthritis) and Neisseria gonorrhea. Lyme arthritis could be consistent with this relapsing remitting presentation as you expect a WBC count between 3000 and 100,000 cells with a mean value between 10,000 and 25,000 cells, > 50% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and negative Gram stains.8 Gonococcal infections often do not have marked elevations in the WBC count and the Gram stain can be variable, but you still expect the WBC count to be > 30,000 cells.7 Inflammatory causes such as gout or autoimmune conditions such as lupus often have a WBC count between 2000 and 100,000 with a negative Gram stain, which could be consistent with this patient’s presentation.7 However, the lack of crystals rules out gout and the negative anti-CCP, rheumatoid factor, and HLA-B27 make rheumatologic diseases less likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient received a phone call from another hospital where an arthrocentesis had been performed 3 weeks before. The results included a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for Lyme disease in the synovial fluid. A subsequent serum Lyme screen was positive for 1 of 3 immunoglobulin (Ig) M bands and 10 of 10 IgG bands.

Dr. Serrao, how does Lyme arthritis typically present, and are there aspects of this case that make you suspect the diagnosis? Does the serum Lyme test give us any additional information?

►Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of Lyme disease. Patients typically have persistent or intermittent arthritis, and large joints are more commonly impacted than small joints. Monoarthritis of the knee is the most common, but oligoarthritis is possible as well. The swelling usually begins abruptly, lasts for weeks to months, and effusions typically recur quickly after aspiration. These findings are consistent with the patient’s clinical history.

For diagnostics, the IgG Western blot is positive if 5 of the 10 bands are positive.9 This patient far exceeds the IgG band number to diagnose Lyme disease. All patients with Lyme arthritis will have positive IgG serologies since Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of the infection. IgM reactivity may be present, but are not necessary to diagnose Lyme arthritis.10 Synovial fluid is often not analyzed for antibody responses as they are susceptible to false positive results, but synovial PCR testing like this patient had detects approximately 70% of patients with untreated Lyme arthritis.11 However, PCR positivity does not necessarily equate with active infection. Serologic testing for Lyme disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot as well as careful history and the exclusion of other diagnoses are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.

► Dr. Merz: On further history the patient reported that 5 years prior he found a tick on his skin with a bull’s-eye rash. He was treated with 28 days of doxycycline at that time. He did not recall any tick bites or rashes in the years since.

Dr. Serrao, is it surprising that he developed Lyme arthritis 5 years after exposure and after being treated appropriately? What is the typical treatment approach for a patient like this?

►Dr. Serrao: It is atypical to develop Lyme arthritis 5 years after reported treatment of what appeared to be early localized disease, namely, erythema migrans. This stage is usually cured with 10 days of treatment alone (he received 28 days) and is generally abortive of subsequent stages, including Lyme arthritis. Furthermore, the patient reported no symptoms of arthritis until recently since that time. Therefore, one can argue that the excessively long span of time from treatment to these first episodes of arthritis suggests the patient could have been reinfected. When available, comparing the types and number of Western blot bands (eg, new and/or more bands on subsequent serologic testing) can support a reinfection diagnosis. A delayed postinfectious inflammatory process from excessive proinflammatory immune responses that block wound repair resulting in proliferative synovitis is also possible.12 This is defined as the postinfectious, postantibiotic, or antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis, a diagnosis of exclusion more apparent only after patients receive appropriate antibiotic courses for the possibility of untreated Lyme as an active infection.12

Given the inherent diagnostic uncertainty between an active infection and posttreatment Lyme arthritis syndromes, it is best to approach most cases of Lyme arthritis as an active infection first especially if not yet treated with antibiotics. Diagnosis of postinflammatory processes should be considered if symptoms persist after appropriate antibiotics, and then short-term use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, rather than further courses of antibiotics, is recommended.

► Dr. Merz: The patient was initiated on doxycycline with the plan to transition to ceftriaxone if there was no response. One day after diagnosis and treatment initiation and in the setting of continued pain, the patient again asked to leave the hospital to drink alcohol. After eloping and becoming intoxicated with alcohol, he returned to his room. He remained concerned about his continued pain and lack of adequate pain control. At the time, he was receiving hydromorphone, ketorolac, lorazepam, gabapentin, and quetiapine.

Dr. Serrao, do you expect this degree of pain from Lyme arthritis?

► Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is typically less painful than other forms of infectious or inflammatory arthritis. Pain is usually caused by the pressure from the acute accumulation and reaccumulation of fluid. In this case, the rapid accumulation of fluid that this patient experienced as well as relief with arthrocentesis suggests that the size and acuity of the effusion was causing great discomfort. Repeated arthrocentesis can prove to be a preventative strategy to minimize synovial herniation.

►Dr. Merz: Dr. Shahal, how do you balance the patient subjectively telling you that they are in pain with objective signs that they may be tolerating the pain like walking around unassisted? Is there anything else that could have been done to prevent this adverse outcome?

►Dr. Shahal: This is one of the hardest pieces of pain management. We want to practice beneficence by believing our patients and addressing their discomfort, but we also want to practice nonmaleficence by avoiding inappropriate long-term pain treatments like opioids that have significant harm as well as avoiding exacerbating this patient’s underlying SUD. An agent like buprenorphine/naloxone could have been an excellent fit to treat pain and SUD, but the patient’s lack of interest and the frequent use of short-acting opioids were major barriers. A chronic pain consult early on is helpful in cases like this as well, but they were unable to see him since he was often out of his room. Repeated arthrocentesis may also have helped the pain. Treatment of anxiety and insomnia with medications like hydroxyzine, trazodone, melatonin, gabapentin, or buspirone as well as interventions like sleep hygiene protocols or spiritual care may have helped somewhat as well.

We know that there is a vicious cycle between pain and poorly controlled mood symptoms. Many of our veterans have PTSD, anxiety, and SUD that are exacerbated by hospitalization and pain. Maintaining optimal communication between the patient and the practitioners, using trauma-informed care, understanding the patient’s goals of care, setting expectations and limits, and attempting to address the patient’s needs while attempting to minimize stigma might be helpful. However, despite optimal care, sometimes these events cannot be avoided.

►Dr. Merz: The patient was ultimately transferred to an inpatient psychiatric unit where a taper plan for the short-acting opioids was implemented. He was psychiatrically stabilized and discharged a few days later off opioids and on doxycycline. On follow-up a few weeks later, his pain had markedly improved, and the effusion was significantly reduced in size. His mood and impulsivity had stabilized. He continues to follow-up in the infectious disease clinic.

1. Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, Brasington R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):83-90.

2. Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: a clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):739-748. doi:10.7326/M19-3602

3. Silverman MM, Berman AL. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part I: a focus on suicide ideation in assessing suicide risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):420-431. doi:10.1111/sltb.12065

4. Berman AL, Silverman MM. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part II: Suicide risk formulation and the determination of levels of risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):432-443. doi:10.1111/sltb.12067

5. Quinlan J, Cox F. Acute pain management in patients with drug dependence syndrome. Pain Rep. 2017;2(4):e611. Published 2017 Jul 27. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000611

6. Chou R, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, et al. Treatments for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566506/

7. Seidman AJ, Limaiem F. Synovial fluid analysis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537114

8. Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(2):269-280. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.004

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. JAMA. 1995;274(12):937.

10. Craft JE, Grodzicki RL, Steere AC. Antibody response in Lyme disease: evaluation of diagnostic tests. J Infect Dis. 1984;149(5):789-795. doi:10.1093/infdis/149.5.789

11. Nocton JJ, Dressler F, Rutledge BJ, Rys PN, Persing DH, Steere AC. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid from patients with Lyme arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(4):229-234. doi:10.1056/NEJM199401273300401

12. Steere AC. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndromes: distinct pathogenesis caused by maladaptive host responses. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2148-2151. doi:10.1172/JCI138062

1. Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, Brasington R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):83-90.

2. Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: a clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):739-748. doi:10.7326/M19-3602

3. Silverman MM, Berman AL. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part I: a focus on suicide ideation in assessing suicide risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):420-431. doi:10.1111/sltb.12065

4. Berman AL, Silverman MM. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part II: Suicide risk formulation and the determination of levels of risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):432-443. doi:10.1111/sltb.12067

5. Quinlan J, Cox F. Acute pain management in patients with drug dependence syndrome. Pain Rep. 2017;2(4):e611. Published 2017 Jul 27. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000611

6. Chou R, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, et al. Treatments for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566506/

7. Seidman AJ, Limaiem F. Synovial fluid analysis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537114

8. Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(2):269-280. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.004

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. JAMA. 1995;274(12):937.

10. Craft JE, Grodzicki RL, Steere AC. Antibody response in Lyme disease: evaluation of diagnostic tests. J Infect Dis. 1984;149(5):789-795. doi:10.1093/infdis/149.5.789

11. Nocton JJ, Dressler F, Rutledge BJ, Rys PN, Persing DH, Steere AC. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid from patients with Lyme arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(4):229-234. doi:10.1056/NEJM199401273300401

12. Steere AC. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndromes: distinct pathogenesis caused by maladaptive host responses. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2148-2151. doi:10.1172/JCI138062

Appropriateness of Pharmacologic Thromboprophylaxis Prescribing Based on Padua Score Among Inpatient Veterans

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) presents as deep venous thromboembolism (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). VTE is the third most common vascular disease and a leading cardiovascular complication.1,2 Hospitalized patients are at increased risk of developing VTE due to multiple factors such as inflammatory processes from acute illness, recent surgery or trauma leading to hypercoagulable states, and prolonged periods of immobilization.3 Additional risk factors for complications include presence of malignancy, obesity, and prior history of VTE. About half of VTE cases in the community setting occur as a result of a hospital admission for recent or ongoing acute illness or surgery.1 Hospitalized patients are often categorized as high risk for VTE, and this risk may persist postdischarge.4

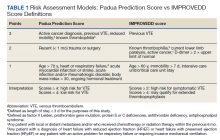

The risk of hospital-associated VTE may be mitigated with either mechanical or pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.5 Risk assessment models (RAMs), such as Padua Prediction Score (PPS) and IMPROVEDD, have been developed to assist in evaluating hospitalized patients’ risk of VTE and need for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (Table 1).1,5 The PPS is externally validated and can assist clinicians in VTE risk assessment when integrated into clinical decision making.6 Patients with a PPS ≥ 4 are deemed high risk for VTE, and pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is indicated as long as the patient is not at high risk for bleeding. IMPROVEDD added D-dimer as an additional risk factor to IMPROVE and was validated in 2017 to help predict the risk of symptomatic VTE in acutely ill patients hospitalized for up to 77 days.7 IMPROVEDD scores ≥ 2 identify patients at high risk for symptomatic VTE through 77 days hospitalization, while scores ≥ 4 identify patients who may qualify for extended thromboprophylaxis.7 Despite their utility, RAMs may not be used appropriately within clinical practice, and whether patients should receive extended-duration thromboprophylaxis postdischarge and for how long is debatable.5

VTE events contribute to increased health care spending, morbidity, and mortality, thus it is imperative to evaluate current hospital practices with respect to appropriate prescribing of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.8 Appropriately identifying high-risk patients and prescribing pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis to limit preventable VTEs is essential. Conversely, it is important to withhold pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis from those deemed low risk to limit bleeding complications.9 Health care professionals must be good stewards of anticoagulant prescribing when implementing these tools along with clinical knowledge to weigh the risks vs benefits to promote medication safety and prevent further complications.10This quality improvement project aimed to evaluate if VTE thromboprophylaxis was appropriately given or withheld in hospitalized medical patients based on PPS calculated upon admission using a link to an online calculator embedded within an admission order set. Additionally, this study aimed to characterize patients readmitted for VTE within 45 days postdischarge to generate hypotheses for future stu

Methods

This was an observational, retrospective cohort study that took place at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS). TVHS is a multisite health care system with campuses in Nashville and Murfreesboro. Clinical pharmacists employed at the study site and the primary research investigators designed this study and oversaw its execution. The study was reviewed and deemed exempt as a quality improvement study by the TVHS Institutional Review Board.

This study included adult veterans aged ≥ 18 years admitted to a general medicine floor or the medical intensive care unit between June 1, 2017, and June 30, 2020. Patients were excluded if they were on chronic therapeutic anticoagulation prior to their index hospitalization, required therapeutic anticoagulation on admission for index hospitalization (ie, acute coronary syndrome requiring a heparin drip), or were bedded within the surgical intensive care unit. All patients admitted to the TVHS within the prespecified date range were extracted from the electronic health record. A second subset of patients meeting inclusion criteria and readmitted for VTE within 45 days of index hospitalization with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) descriptions including thrombosis or embolism were extracted for review of a secondary endpoint. Patients with preexisting clots, history of prior DVT or PE, or history of portal vein thrombosis were not reviewed.

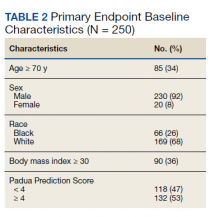

The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients for whom pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was appropriately initiated or withheld based on a PPS calculated upon admission (Table 2). PPS was chosen for review as it is the only RAM currently used at TVHS. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of patients with documented rationale for ordering thromboprophylaxis when not indicated, based on PPS, or withholding despite indication as well as the number of patients readmitted to TVHS for VTE within 45 days of discharge with IMPROVEDD scores ≥ 4 and < 4 (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0291). The primary investigators performed a manual health record review of all patients meeting inclusion criteria. Descriptive statistics were used given this was a quality improvement study, therefore, sample size and power calculations were not necessary. Data were stored in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets that were encrypted and password protected. To maintain security of personal health information, all study files were kept on the TVHS internal network, and access was limited to the research investigators.

Results

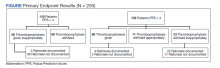

Two hundred fifty patients meeting inclusion criteria were randomly selected for review for the primary endpoint. Of the patients reviewed for the primary endpoint, 118 had a PPS < 4 and 132 a PPS ≥ 4 (Figure). Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was inappropriately given or withheld based on their PPS for 91 (36.4%) patients. This included 58 (49.2%) patients in the low-risk group (PPS < 4) who had thromboprophylaxis inappropriately given and 33 (25.0%) patients in the high-risk group (PPS ≥ 4) who had thromboprophylaxis inappropriately withheld. Of the 58 patients with a PPS < 4 who were given prophylaxis, only 2 (3.4%) patients had documented rationale as to why anticoagulation was administered. Of the 132 patients with a PPS ≥ 4, 44 patients had thromboprophylaxis withheld. Eleven (8.3%) patients had thromboprophylaxis appropriately withheld due to presence or concern for bleeding. Commonly documented rationale for inappropriately withholding thromboprophylaxis when indicated included use of sequential compression devices (40.9%), pancytopenia (18.2%), dual antiplatelet therapy (9.1%), or patient was ambulatory (4.5%).

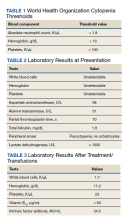

A secondary endpoint characterized patients at highest risk for developing a VTE after hospitalization for an acute illness. Seventy patients were readmitted within 45 days of discharge from the index hospitalization with ICD descriptions for embolism or thrombosis. Only 15 of those patients were readmitted with a newly diagnosed VTE not previously identified; 14 (93.3%) had a PPS ≥ 4 upon index admission and 10 (66.7%) appropriately received pharmacologic prophylaxis within 24 hours of admission. Of the 15 patients, 3 (20.0%) did not receive pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis within 24 hours of admission and 1 (6.7%) received thromboprophylaxis despite having a PPS < 4.

Looking at IMPROVEDD scores for the 15 patients at the index hospitalization discharge, 1 (6.7%) patient had an IMPROVEDD score < 2, 11 (73.3%) patients had IMPROVEDD scores ≥ 2, and 3 (20.0%) patients had IMPROVEDD scores ≥ 4. Two of the patients with IMPROVEDD scores ≥ 4 had a history of VTE and were aged > 60 years. Of the 15 patients reviewed, 7 had a diagnosis of cancer, and 3 were actively undergoing chemotherapy.

Discussion

PPS is the RAM embedded in our system’s order set, which identifies hospitalized medical patients at risk for VTE.6 In the original study that validated PPS, the results suggested that implementation of preventive measures during hospitalization in patients labeled as having high thrombotic risk confers longstanding protection against thromboembolic complications in comparison with untreated patients.6 However, PPS must be used consistently and appropriately to realize this benefit. Our results showed that pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is frequently inappropriately given or withheld despite the incorporation of a RAM in an admission order set, suggesting there is a significant gap between written policy and actual practice. More than one-third of patients had thromboprophylaxis given or withheld inappropriately according to the PPS calculated manually on review. With this, there is concern for over- and underprescribing of thromboprophylaxis, which increases the risk of adverse events. Overprescribing can lead to unnecessary bleeding complications, whereas underprescribing can lead to preventable VTE.

One issue identified during this study was the need for a user-friendly interface. The PPS calculator currently embedded in our admission order set is a hyperlink to an online calculator. This is time consuming and cumbersome for clinicians tending to a high volume of patients, which may cause them to overlook the calculator and estimate risk based on clinician judgement. Noted areas for improvement regarding thromboprophylaxis during inpatient admissions include the failure to implement or adhere to risk stratification protocols, lack of appropriate assessment for thromboprophylaxis, and the overutilization of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in low-risk patients.11

Certain patients develop a VTE postdischarge despite efforts at prevention during their index hospitalization, which led us to explore our secondary endpoint looking at readmissions. Regarding thromboprophylaxis postdischarge, the duration of therapy is an area of current debate.5 Extended-duration thromboprophylaxis is defined as anticoagulation prescribed beyond hospitalization for up to 42 days total.1,12 To date, there have been 5 clinical trials to evaluate the utility of extended-duration thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medically ill patients. While routine use is not recommended by the 2018 American Society of Hematology guidelines for management of VTE, more recent data suggest certain medically ill patients may derive benefit from extended-duration thromboprophylaxis.4 The IMPROVEDD score aimed to address this need, which is why it was calculated on index discharge for our patients readmitted within 45 days. Research is still needed to identify such patients and RAMs for capturing these subpopulations.1,11

Our secondary endpoint sought to characterize patients at highest risk for developing a VTE postdischarge. Of the 15 patients reviewed, 7 had a diagnosis of cancer and 3 were actively undergoing chemotherapy. With that, the Khorana Risk Score may have been a more appropriate RAM for some given the Khorana score is validated in ambulatory patients undergoing chemotherapy. D-dimer was only collected for 1 of the 15 patients, therefore, VTE risk could have been underestimated with the IMPROVEDD scores calculated. More than 75% of patients readmitted for VTE appropriately received thromboprophylaxis on index admission yet still went on to develop a VTE. It is essential to increase clinician awareness about hospital-acquired and postdischarge VTE. In line with guidance from the North American Thrombosis Forum, extended-duration thromboprophylaxis should be thoughtfully considered in high-risk patients.5 Pathways, including follow-up, are needed to implement postdischarge thromboprophylaxis when appropriate

Limitations

There were some inherent limitations to this study with its retrospective nature and small sample size. Data extraction was limited to health records within the VA, so there is a chance relevant history could be missed via incomplete documentation. Thus, our results could be an underestimation of postdischarge VTE prevalence if patients sought medical attention outside of the VA. Given this study was a retrospective chart review, data collection was limited to what was explicitly documented in the chart. Rationale for giving thromboprophylaxis when not indicated or holding when indicated may have been underestimated if clinicians did not document thoroughly in the electronic health record. Last, for the secondary endpoint reviewing the IMPROVEDD score, a D-dimer was not consistently obtained on admission, which could lead to underestimation of risk.

Conclusions

The results of this study showed that more than one-third of patients admitted to our facility within the prespecified timeframe had pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis inappropriately given or withheld according to a PPS manually calculated on admission. The PPS calculator currently embedded within our admission order set is not being utilized appropriately or consistently in clinical practice. Additionally, results from the secondary endpoint looking at IMPROVEDD scores highlight an unmet need for thromboprophylaxis at discharge. Pathways are needed to implement postdischarge thromboprophylaxis when appropriate for patients at highest thromboembolic risk.

1. Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3198-3225. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2018022954

2. Heit JA. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(8):464-474. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2015.83

3. Turpie AG, Chin BS, Lip GY. Venous thromboembolism: pathophysiology, clinical features, and prevention. BMJ. 2002;325(7369):887-890. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7369.887

4. Bajaj NS, Vaduganathan M, Qamar A, et al. Extended prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism after hospitalization for medical illness: A trial sequential and cumulative meta-analysis. Cannegieter SC, ed. PLoS Med. 2019;16(4):e1002797. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002797

5. Barkoudah E, Piazza G, Hecht TEH, et al. Extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medically ill patients: an NATF anticoagulation action initiative. Am J Med. 2020;133 (suppl 1):1-27. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.12.001

6. Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2450-7. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04044.x

7. Gibson CM, Spyropoulos AC, Cohen AT, et al. The IMPROVEDD VTE risk score: incorporation of D-dimer into the IMPROVE score to improve venous thromboembolism risk stratification. TH Open. 2017;1(1):e56-e65. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1603929

8. ISTH Steering Committee for World Thrombosis Day. Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. Thromb Res. 2014;134(5):931-938. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2014.08.014

9. Pavon JM, Sloane RJ, Pieper CF, et al. Poor adherence to risk stratification guidelines results in overuse of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(6):403-404. doi:10.12788/jhm.2916

10. Core elements of anticoagulation stewardship programs. Anticoagulation Forum. 2019. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://acforum-excellence.org/Resource-Center/resource_files/-2019-09-18-110254.pdf

11. Core elements of anticoagulation stewardship programs administrative oversight gap analysis: hospital and skilled nursing facilities. Anticoagulation Forum. 2019. Accessed June 6, 2022. https://acforum.org/web/downloads/ACF%20Gap%20Analysis%20Report.pdf

12. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e278S-e325S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2404

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) presents as deep venous thromboembolism (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE). VTE is the third most common vascular disease and a leading cardiovascular complication.1,2 Hospitalized patients are at increased risk of developing VTE due to multiple factors such as inflammatory processes from acute illness, recent surgery or trauma leading to hypercoagulable states, and prolonged periods of immobilization.3 Additional risk factors for complications include presence of malignancy, obesity, and prior history of VTE. About half of VTE cases in the community setting occur as a result of a hospital admission for recent or ongoing acute illness or surgery.1 Hospitalized patients are often categorized as high risk for VTE, and this risk may persist postdischarge.4

The risk of hospital-associated VTE may be mitigated with either mechanical or pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.5 Risk assessment models (RAMs), such as Padua Prediction Score (PPS) and IMPROVEDD, have been developed to assist in evaluating hospitalized patients’ risk of VTE and need for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (Table 1).1,5 The PPS is externally validated and can assist clinicians in VTE risk assessment when integrated into clinical decision making.6 Patients with a PPS ≥ 4 are deemed high risk for VTE, and pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis is indicated as long as the patient is not at high risk for bleeding. IMPROVEDD added D-dimer as an additional risk factor to IMPROVE and was validated in 2017 to help predict the risk of symptomatic VTE in acutely ill patients hospitalized for up to 77 days.7 IMPROVEDD scores ≥ 2 identify patients at high risk for symptomatic VTE through 77 days hospitalization, while scores ≥ 4 identify patients who may qualify for extended thromboprophylaxis.7 Despite their utility, RAMs may not be used appropriately within clinical practice, and whether patients should receive extended-duration thromboprophylaxis postdischarge and for how long is debatable.5

VTE events contribute to increased health care spending, morbidity, and mortality, thus it is imperative to evaluate current hospital practices with respect to appropriate prescribing of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.8 Appropriately identifying high-risk patients and prescribing pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis to limit preventable VTEs is essential. Conversely, it is important to withhold pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis from those deemed low risk to limit bleeding complications.9 Health care professionals must be good stewards of anticoagulant prescribing when implementing these tools along with clinical knowledge to weigh the risks vs benefits to promote medication safety and prevent further complications.10This quality improvement project aimed to evaluate if VTE thromboprophylaxis was appropriately given or withheld in hospitalized medical patients based on PPS calculated upon admission using a link to an online calculator embedded within an admission order set. Additionally, this study aimed to characterize patients readmitted for VTE within 45 days postdischarge to generate hypotheses for future stu

Methods

This was an observational, retrospective cohort study that took place at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Tennessee Valley Healthcare System (TVHS). TVHS is a multisite health care system with campuses in Nashville and Murfreesboro. Clinical pharmacists employed at the study site and the primary research investigators designed this study and oversaw its execution. The study was reviewed and deemed exempt as a quality improvement study by the TVHS Institutional Review Board.

This study included adult veterans aged ≥ 18 years admitted to a general medicine floor or the medical intensive care unit between June 1, 2017, and June 30, 2020. Patients were excluded if they were on chronic therapeutic anticoagulation prior to their index hospitalization, required therapeutic anticoagulation on admission for index hospitalization (ie, acute coronary syndrome requiring a heparin drip), or were bedded within the surgical intensive care unit. All patients admitted to the TVHS within the prespecified date range were extracted from the electronic health record. A second subset of patients meeting inclusion criteria and readmitted for VTE within 45 days of index hospitalization with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) descriptions including thrombosis or embolism were extracted for review of a secondary endpoint. Patients with preexisting clots, history of prior DVT or PE, or history of portal vein thrombosis were not reviewed.

The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients for whom pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was appropriately initiated or withheld based on a PPS calculated upon admission (Table 2). PPS was chosen for review as it is the only RAM currently used at TVHS. Secondary endpoints were the percentage of patients with documented rationale for ordering thromboprophylaxis when not indicated, based on PPS, or withholding despite indication as well as the number of patients readmitted to TVHS for VTE within 45 days of discharge with IMPROVEDD scores ≥ 4 and < 4 (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0291). The primary investigators performed a manual health record review of all patients meeting inclusion criteria. Descriptive statistics were used given this was a quality improvement study, therefore, sample size and power calculations were not necessary. Data were stored in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets that were encrypted and password protected. To maintain security of personal health information, all study files were kept on the TVHS internal network, and access was limited to the research investigators.

Results