User login

Setting and Method of Measurement Affect Blood Pressure Readings in Older Veterans

Seventy-five percent of adults aged >75 years have hypertension.1-3 According to the Joint National Commission 8 (JNC 8), the recommended target blood pressure (BP) is < 150/80 mm Hg for adults aged > 60 years.4 In 2016 the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) suggested that more aggressive BP control with a goal of < 120/80 mm Hg reduced rates of cardiovascular disease and lowered the risk of death in adults aged > 50 years with hypertension.5 It is anticipated that as a result of the landmark SPRINT results, clinicians may attempt to treat hypertension more intensely in older patients with an increased risk of adverse consequences if BPs are not appropriately measured.

There is a standardized protocol for BP measurement, but these recommendations typically are not followed in routine office visits.6,7 Some studies have noted that home BP measurement may be more accurate than office measurement.8 However, clinicians may not always trust the accuracy of home BP readings, and many patients are not adherent with home measurement. As a result, physicians usually manage hypertension in older patients based on office readings, though it is likely that most office measurements do not follow protocol on proper measurement. Office measurements have been noted to be inaccurate with high likelihood of overestimating or underestimating BP control.9

Office BP measurements demonstrate poor correlation with home measurements and have not been shown to be as good of a predictor for target organ damage or long-term cardiovascular outcomes compared with that of home measurements.10,11 Although there have been studies comparing home and office BP measurements and comparing office and ambulatory BP measurement, no literature has been found that reports on the difference between routine office and standardized measurement of BP.9,12-14

This study seeks to identify the magnitude of difference among BP measured according to a standardized protocol, routine clinical, and home BP. The authors hypothesized that there would be a significant, clinically relevant difference among the 3 BP measurement methods, especially between the routine office and standardized office measurements. This study has implications for implementing intensive treatment of hypertension based on office measurements.

Methods

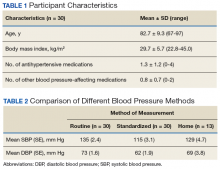

Participants included 30 male veterans aged > 65 years who were actively participating in the Gerofit program at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS). The Gerofit program is a model clinical demonstration exercise and health promotion program targeting older and veterans at risk for falls or institutionalization. Gerofit was established in 1987 at the Durham VA Health System and successfully implemented in 2014 at VAGLAHS. Supervised exercise is offered 3 times per week and consists of individually tailored exercises aimed at reducing functional deficits that are identified and monitored by an initial and quarterly functional assessment. Blood pressures are checked routinely once a week as a part of the program. Gerofit was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at VAGLAHS as a quality improvement/quality assurance project.

Data

Routine office and standardized protocol measurements were obtained by a single CasMED 740 (Branford, CT) automated BP machine and were conducted separately on different days. The CasMED 740 machine was not otherwise calibrated; however, a one-time correlation was performed between the CasMED 740 and the home BP monitor for each participant, when it was brought to VAGLAHS. Two measurements were made with the CasMed 740 automated BP machine on the arm that gave the higher BP reading throughout the standardized and routine protocol. Two subsequent measurements were made with the participant’s home automated BP cuff. Averages for the CasMED 740 and the home BP monitoring device were compared and assessed for significance by paired t test. No rest was scheduled prior to the first measurement, but there was a 1-minute rest after each subsequent measurement.

Mean values (SD) were used for participant characteristics and mean values (standard error [SE]) were used for BP measurements. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) and GraphPad Prism version 7.03 (San Diego, CA). T tests were used for analysis of home BP measurements due to low sample size. Values of P < .05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Routine office protocol. Automated BP was measured to mimic routine office visits. Upon arrival, participants sat down, and the BP cuff was placed around their arm. Any rest before a measurement was incidental and not intentionally structured. Appropriate cuff size was determined by visual estimation of arm circumference. Only 1 measurement was made unless BP was > 150/90 mm Hg, in which case a repeat measurement was made after 2 to 4 minutes of rest. The BP was then determined based on the average of 2 or more readings. The BPs were recorded by hand in a weekly log. Participants had at least 12 weeks of BP readings measured by the routine method, and these BPs were averaged over 12 weeks to yield their average routine measured BP.

Standardized protocol. Automated BP was measured according to the 2015 USPSTF Guidelines and Look AHEAD trial protocol.7,15 A participant’s arm circumference was measured, and appropriate cuff size was determined. The participant rested quietly in a chair for at least 5 minutes with feet flat on the floor and back supported. The cuff was snugly placed 2 to 3 cm above the antecubital fossa, and the arm was supported at the level of the right atrium during the measurement. Blood pressure was determined using the mean of 4 automated cuff readings, 2 on each arm, taken 1 minute apart. Participants did not necessarily have their BP measured by the standardized method immediately following the routine method but all measurements were performed during the same 12-week time period.

Home blood pressure protocol. Participants were given instructions according to the American Heart Association (AHA) recommendations for measuring home BP. Patients were instructed to use a calibrated, automated arm BP cuff. Home BP machines were not provided in advance, and each individual’s BP machine was not calibrated. They also were instructed to rest at least 5 minutes before measuring their BP. The mean home BP was determined by the cumulative average of 3 readings in the morning and evening, taken 1 minute between each reading, for a total of 6 readings/d. Participants recorded home BPs for 2 weeks before submitting their readings. Each participant affirmed clear understanding of how to measure BP by correctly demonstrating placement of the cuff 1 time under supervision.

Results

Thirty veterans aged > 65 years participated in the study. The average age (SD) was 82.7 (9.3) years. The average BMI (SD) was overweight at 29.7 kg/m2 (5.7). Most (87.6%) of the study participants had been diagnosed with hypertension prior to the study, and no new diagnoses were made as a result of the study.

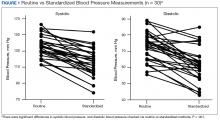

Both systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BPs (DBP) measured by the standardized method were significantly lower than those by the routine method (P < .01 and P < .01, respectively) (Figure 1).

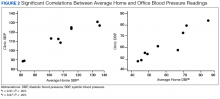

To determine the accuracy of the home BP monitors, the average routine VAGLAHS BP measure was compared with home BP results. For SBPs, there was a significant correlation coefficient of 0.91 (P < .01).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that standardized measurements of BP were lower than that of the routine method used in most office settings. These results suggest that there could be a risk of overtreatment for some patients those of whose results are higher than the SPRINT BP target of < 120/80 mm Hg. Clinicians might be treating BPs that are elevated due to improper measurement, which can lead to deleterious consequences in older adults, such as syncope and falls.16

Each participant exhibited a significantly lower BP reading with the standardized method than the routine method. The 20-point decrease in SBP and 10-point decrease in DBP are clinically significant. The routine method of measurement was intended to simulate BP measurement in outpatient settings. There is usually little time structured for rest, and because the protocol established by the AHA and other professional organizations is time consuming, it usually is not strictly followed. With guidelines proposed by JNC 8 and new findings from SPRINT, the method of BP readings should be reviewed in all clinical settings.

While changes in BP management are not necessarily immediate, the differences in recommendations proposed by SPRINT and JNC 8 can lead to confusion regarding how intensely to treat BP. These recommendations guide clinical practice, but clinicians’ best judgment ultimately determines BP management. Physicians who utilize routine office measurements likely rely on BP readings that are higher on average than are readings done under proper conditions. This leads to the prospect of overtreatment, where physicians attempt to control hypertension too aggressively, potentially leading to orthostatic hypotension, syncope, and increased risk for falls.16 With findings from SPRINT recommending even lower BPs than that by JNC 8, overtreatment risk becomes especially relevant. While BP protocol was strictly followed in SPRINT, some clinicians may not necessarily follow the same fastidious protocol.

The average differences between the home and standardized BPs were not statistically significant possibly due to the small sample size in the home BP measurements; however, the difference might represent some clinical relevance. There was a 15-point difference in SBP results between home (129 mm Hg) and standardized (115 mm Hg) measures. There also was a difference in DBP between home (69 mm Hg) and standardized (62 mm Hg) results. The close correlation between both home and BPs measured in VAGLAHS demonstrated that any difference was not due to variability in the measurement devices. Previous studies have demonstrated that home BPs are better indicators of cardiovascular risk than office BP.8

Despite lack of statistical significance, home BPs were lower than routine, which suggests that they still may be more reliable than routine office measurements. Definitive conclusions regarding the accuracy of the home BPs in the present study cannot be drawn due to the small sample size (n = 13). Further exploration with comparisons to ambulatory BP monitoring could yield more information on accuracy of home BP monitoring.

In this study’s cohort of older veterans, the average BMI was between 25 and 30 (overweight), which is a risk factor for hypertension.17 Every participant with hypertension was taking at least 1 antihypertensive medication and being actively managed. In this study, the authors accounted for other medications that may affect BP, such as α blockers used in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia.18 These could have potential elevating or lowering effects on BP measurements.

An issue in this study was the lack of adherence to home BP monitoring. Many patients forgot to bring in their records or to measure their BPs at home. The difficulties highlight real-life issues. Clinicians often request that patients monitor their BP at home, but few may actually remember, let alone keep diligent records. There are many barriers between measuring and reporting home BPs, which may prevent the usefulness of monitoring BP at home.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. There was no specific protocol for the routine method of BP measurement, as it was intended to simulate the haphazard nature of office measurements. However, this approach limits its reproducibility. For home BP monitoring, it would have been ideal to provide the same calibrated, automated BP device to each participant. This study of older veterans may not be applicable to the general population. Finally, the relatively small number of participants in the study (n = 30) may have limited power in drawing definitive conclusions.

Future Directions

For future studies, comparing the standardized method to ambulatory BP monitoring would provide more information on accuracy. In addition, the authors would like to evaluate the effect of exercise on BP measurements in the different settings: home, standardized, and routine methods.

1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29-e322.

2. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603.

3. Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(133):1-8.

4. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

5. Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al; SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥ 75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(24):2673-2682.

6. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al; Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee, American Heart Association. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans: an AHA scientific statement from the Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2005;7(2):102-109.

7. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):778-786.

8. Niiranen TJ, Hänninen MR, Johansson J, Reunanen A, Jula AM. Home-measured blood pressure is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular risk than office blood pressure: the Finn-Home study. Hypertension. 2010;55(6):1346-1351.

9. Reino-Gonzalez S, Pita-Fernández S, Seoane-Pillado T, López-Calviño B, Pértega Díaz S. How in-office and ambulatory BP monitoring compare: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Fam Pract. 2017;66(1):E5-E12.

10. Cohen JB, Cohen DL. Integrating out-of-office blood pressure in the diagnosis and management of hypertension. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(11):112.

11. Fuchs SC, Mello RB, Fuchs FC. Home blood pressure monitoring is better predictor of cardiovascular disease and target organ damage than office blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2013;15(11):413.

12. Imai Y, Obara T, Asamaya K, Ohkubo T. The reason why home blood pressure measurements are preferred over clinic or ambulatory blood pressure in Japan. Hypertens Res. 2013;36(8):661-672.

13. Bliziotis IA, Destounis A, Stergiou GS. Home versus ambulatory and office blood pressure in predicting target organ damage in hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2012;30(7):1289-1299.

14. Yang Y, Xu JZ, Wang Y, Gao PJ. Ambulatory versus clinic blood pressure in predicting overall subclinical target organ damage progression in essential hypertensive patients: a 3-year follow-up study. Blood Press Monit. 2016;21(6):319-326.

15. Espeland MA, Probstfield J, Hire D, et al; Look AHEAD Research Group; ACCORD Study Group. Systolic blood pressure control among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a comparative effectiveness analysis of three interventions. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(8):995-1009.

16. Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, et al. Benefits and harms of intensive blood pressure treatment in adults aged 60 years or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):419-429.

17. Nagai M, Ohkubo T, Murakami Y, et al; NIPPON DATA80/90/2010 Research Group. Secular trends of the impact of overweight and obesity on hypertension in Japan, 1980-2010. Hypertens Res. 2015;38(11):790-795.

18. Press Y, Punchik B, Freud T. Orthostatic hypotension and drug therapy in patients at an outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment unit. J Hypertens. 2016;34(2):351-358.

Seventy-five percent of adults aged >75 years have hypertension.1-3 According to the Joint National Commission 8 (JNC 8), the recommended target blood pressure (BP) is < 150/80 mm Hg for adults aged > 60 years.4 In 2016 the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) suggested that more aggressive BP control with a goal of < 120/80 mm Hg reduced rates of cardiovascular disease and lowered the risk of death in adults aged > 50 years with hypertension.5 It is anticipated that as a result of the landmark SPRINT results, clinicians may attempt to treat hypertension more intensely in older patients with an increased risk of adverse consequences if BPs are not appropriately measured.

There is a standardized protocol for BP measurement, but these recommendations typically are not followed in routine office visits.6,7 Some studies have noted that home BP measurement may be more accurate than office measurement.8 However, clinicians may not always trust the accuracy of home BP readings, and many patients are not adherent with home measurement. As a result, physicians usually manage hypertension in older patients based on office readings, though it is likely that most office measurements do not follow protocol on proper measurement. Office measurements have been noted to be inaccurate with high likelihood of overestimating or underestimating BP control.9

Office BP measurements demonstrate poor correlation with home measurements and have not been shown to be as good of a predictor for target organ damage or long-term cardiovascular outcomes compared with that of home measurements.10,11 Although there have been studies comparing home and office BP measurements and comparing office and ambulatory BP measurement, no literature has been found that reports on the difference between routine office and standardized measurement of BP.9,12-14

This study seeks to identify the magnitude of difference among BP measured according to a standardized protocol, routine clinical, and home BP. The authors hypothesized that there would be a significant, clinically relevant difference among the 3 BP measurement methods, especially between the routine office and standardized office measurements. This study has implications for implementing intensive treatment of hypertension based on office measurements.

Methods

Participants included 30 male veterans aged > 65 years who were actively participating in the Gerofit program at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS). The Gerofit program is a model clinical demonstration exercise and health promotion program targeting older and veterans at risk for falls or institutionalization. Gerofit was established in 1987 at the Durham VA Health System and successfully implemented in 2014 at VAGLAHS. Supervised exercise is offered 3 times per week and consists of individually tailored exercises aimed at reducing functional deficits that are identified and monitored by an initial and quarterly functional assessment. Blood pressures are checked routinely once a week as a part of the program. Gerofit was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at VAGLAHS as a quality improvement/quality assurance project.

Data

Routine office and standardized protocol measurements were obtained by a single CasMED 740 (Branford, CT) automated BP machine and were conducted separately on different days. The CasMED 740 machine was not otherwise calibrated; however, a one-time correlation was performed between the CasMED 740 and the home BP monitor for each participant, when it was brought to VAGLAHS. Two measurements were made with the CasMed 740 automated BP machine on the arm that gave the higher BP reading throughout the standardized and routine protocol. Two subsequent measurements were made with the participant’s home automated BP cuff. Averages for the CasMED 740 and the home BP monitoring device were compared and assessed for significance by paired t test. No rest was scheduled prior to the first measurement, but there was a 1-minute rest after each subsequent measurement.

Mean values (SD) were used for participant characteristics and mean values (standard error [SE]) were used for BP measurements. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) and GraphPad Prism version 7.03 (San Diego, CA). T tests were used for analysis of home BP measurements due to low sample size. Values of P < .05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Routine office protocol. Automated BP was measured to mimic routine office visits. Upon arrival, participants sat down, and the BP cuff was placed around their arm. Any rest before a measurement was incidental and not intentionally structured. Appropriate cuff size was determined by visual estimation of arm circumference. Only 1 measurement was made unless BP was > 150/90 mm Hg, in which case a repeat measurement was made after 2 to 4 minutes of rest. The BP was then determined based on the average of 2 or more readings. The BPs were recorded by hand in a weekly log. Participants had at least 12 weeks of BP readings measured by the routine method, and these BPs were averaged over 12 weeks to yield their average routine measured BP.

Standardized protocol. Automated BP was measured according to the 2015 USPSTF Guidelines and Look AHEAD trial protocol.7,15 A participant’s arm circumference was measured, and appropriate cuff size was determined. The participant rested quietly in a chair for at least 5 minutes with feet flat on the floor and back supported. The cuff was snugly placed 2 to 3 cm above the antecubital fossa, and the arm was supported at the level of the right atrium during the measurement. Blood pressure was determined using the mean of 4 automated cuff readings, 2 on each arm, taken 1 minute apart. Participants did not necessarily have their BP measured by the standardized method immediately following the routine method but all measurements were performed during the same 12-week time period.

Home blood pressure protocol. Participants were given instructions according to the American Heart Association (AHA) recommendations for measuring home BP. Patients were instructed to use a calibrated, automated arm BP cuff. Home BP machines were not provided in advance, and each individual’s BP machine was not calibrated. They also were instructed to rest at least 5 minutes before measuring their BP. The mean home BP was determined by the cumulative average of 3 readings in the morning and evening, taken 1 minute between each reading, for a total of 6 readings/d. Participants recorded home BPs for 2 weeks before submitting their readings. Each participant affirmed clear understanding of how to measure BP by correctly demonstrating placement of the cuff 1 time under supervision.

Results

Thirty veterans aged > 65 years participated in the study. The average age (SD) was 82.7 (9.3) years. The average BMI (SD) was overweight at 29.7 kg/m2 (5.7). Most (87.6%) of the study participants had been diagnosed with hypertension prior to the study, and no new diagnoses were made as a result of the study.

Both systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BPs (DBP) measured by the standardized method were significantly lower than those by the routine method (P < .01 and P < .01, respectively) (Figure 1).

To determine the accuracy of the home BP monitors, the average routine VAGLAHS BP measure was compared with home BP results. For SBPs, there was a significant correlation coefficient of 0.91 (P < .01).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that standardized measurements of BP were lower than that of the routine method used in most office settings. These results suggest that there could be a risk of overtreatment for some patients those of whose results are higher than the SPRINT BP target of < 120/80 mm Hg. Clinicians might be treating BPs that are elevated due to improper measurement, which can lead to deleterious consequences in older adults, such as syncope and falls.16

Each participant exhibited a significantly lower BP reading with the standardized method than the routine method. The 20-point decrease in SBP and 10-point decrease in DBP are clinically significant. The routine method of measurement was intended to simulate BP measurement in outpatient settings. There is usually little time structured for rest, and because the protocol established by the AHA and other professional organizations is time consuming, it usually is not strictly followed. With guidelines proposed by JNC 8 and new findings from SPRINT, the method of BP readings should be reviewed in all clinical settings.

While changes in BP management are not necessarily immediate, the differences in recommendations proposed by SPRINT and JNC 8 can lead to confusion regarding how intensely to treat BP. These recommendations guide clinical practice, but clinicians’ best judgment ultimately determines BP management. Physicians who utilize routine office measurements likely rely on BP readings that are higher on average than are readings done under proper conditions. This leads to the prospect of overtreatment, where physicians attempt to control hypertension too aggressively, potentially leading to orthostatic hypotension, syncope, and increased risk for falls.16 With findings from SPRINT recommending even lower BPs than that by JNC 8, overtreatment risk becomes especially relevant. While BP protocol was strictly followed in SPRINT, some clinicians may not necessarily follow the same fastidious protocol.

The average differences between the home and standardized BPs were not statistically significant possibly due to the small sample size in the home BP measurements; however, the difference might represent some clinical relevance. There was a 15-point difference in SBP results between home (129 mm Hg) and standardized (115 mm Hg) measures. There also was a difference in DBP between home (69 mm Hg) and standardized (62 mm Hg) results. The close correlation between both home and BPs measured in VAGLAHS demonstrated that any difference was not due to variability in the measurement devices. Previous studies have demonstrated that home BPs are better indicators of cardiovascular risk than office BP.8

Despite lack of statistical significance, home BPs were lower than routine, which suggests that they still may be more reliable than routine office measurements. Definitive conclusions regarding the accuracy of the home BPs in the present study cannot be drawn due to the small sample size (n = 13). Further exploration with comparisons to ambulatory BP monitoring could yield more information on accuracy of home BP monitoring.

In this study’s cohort of older veterans, the average BMI was between 25 and 30 (overweight), which is a risk factor for hypertension.17 Every participant with hypertension was taking at least 1 antihypertensive medication and being actively managed. In this study, the authors accounted for other medications that may affect BP, such as α blockers used in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia.18 These could have potential elevating or lowering effects on BP measurements.

An issue in this study was the lack of adherence to home BP monitoring. Many patients forgot to bring in their records or to measure their BPs at home. The difficulties highlight real-life issues. Clinicians often request that patients monitor their BP at home, but few may actually remember, let alone keep diligent records. There are many barriers between measuring and reporting home BPs, which may prevent the usefulness of monitoring BP at home.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. There was no specific protocol for the routine method of BP measurement, as it was intended to simulate the haphazard nature of office measurements. However, this approach limits its reproducibility. For home BP monitoring, it would have been ideal to provide the same calibrated, automated BP device to each participant. This study of older veterans may not be applicable to the general population. Finally, the relatively small number of participants in the study (n = 30) may have limited power in drawing definitive conclusions.

Future Directions

For future studies, comparing the standardized method to ambulatory BP monitoring would provide more information on accuracy. In addition, the authors would like to evaluate the effect of exercise on BP measurements in the different settings: home, standardized, and routine methods.

Seventy-five percent of adults aged >75 years have hypertension.1-3 According to the Joint National Commission 8 (JNC 8), the recommended target blood pressure (BP) is < 150/80 mm Hg for adults aged > 60 years.4 In 2016 the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) suggested that more aggressive BP control with a goal of < 120/80 mm Hg reduced rates of cardiovascular disease and lowered the risk of death in adults aged > 50 years with hypertension.5 It is anticipated that as a result of the landmark SPRINT results, clinicians may attempt to treat hypertension more intensely in older patients with an increased risk of adverse consequences if BPs are not appropriately measured.

There is a standardized protocol for BP measurement, but these recommendations typically are not followed in routine office visits.6,7 Some studies have noted that home BP measurement may be more accurate than office measurement.8 However, clinicians may not always trust the accuracy of home BP readings, and many patients are not adherent with home measurement. As a result, physicians usually manage hypertension in older patients based on office readings, though it is likely that most office measurements do not follow protocol on proper measurement. Office measurements have been noted to be inaccurate with high likelihood of overestimating or underestimating BP control.9

Office BP measurements demonstrate poor correlation with home measurements and have not been shown to be as good of a predictor for target organ damage or long-term cardiovascular outcomes compared with that of home measurements.10,11 Although there have been studies comparing home and office BP measurements and comparing office and ambulatory BP measurement, no literature has been found that reports on the difference between routine office and standardized measurement of BP.9,12-14

This study seeks to identify the magnitude of difference among BP measured according to a standardized protocol, routine clinical, and home BP. The authors hypothesized that there would be a significant, clinically relevant difference among the 3 BP measurement methods, especially between the routine office and standardized office measurements. This study has implications for implementing intensive treatment of hypertension based on office measurements.

Methods

Participants included 30 male veterans aged > 65 years who were actively participating in the Gerofit program at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS). The Gerofit program is a model clinical demonstration exercise and health promotion program targeting older and veterans at risk for falls or institutionalization. Gerofit was established in 1987 at the Durham VA Health System and successfully implemented in 2014 at VAGLAHS. Supervised exercise is offered 3 times per week and consists of individually tailored exercises aimed at reducing functional deficits that are identified and monitored by an initial and quarterly functional assessment. Blood pressures are checked routinely once a week as a part of the program. Gerofit was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at VAGLAHS as a quality improvement/quality assurance project.

Data

Routine office and standardized protocol measurements were obtained by a single CasMED 740 (Branford, CT) automated BP machine and were conducted separately on different days. The CasMED 740 machine was not otherwise calibrated; however, a one-time correlation was performed between the CasMED 740 and the home BP monitor for each participant, when it was brought to VAGLAHS. Two measurements were made with the CasMed 740 automated BP machine on the arm that gave the higher BP reading throughout the standardized and routine protocol. Two subsequent measurements were made with the participant’s home automated BP cuff. Averages for the CasMED 740 and the home BP monitoring device were compared and assessed for significance by paired t test. No rest was scheduled prior to the first measurement, but there was a 1-minute rest after each subsequent measurement.

Mean values (SD) were used for participant characteristics and mean values (standard error [SE]) were used for BP measurements. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) and GraphPad Prism version 7.03 (San Diego, CA). T tests were used for analysis of home BP measurements due to low sample size. Values of P < .05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Routine office protocol. Automated BP was measured to mimic routine office visits. Upon arrival, participants sat down, and the BP cuff was placed around their arm. Any rest before a measurement was incidental and not intentionally structured. Appropriate cuff size was determined by visual estimation of arm circumference. Only 1 measurement was made unless BP was > 150/90 mm Hg, in which case a repeat measurement was made after 2 to 4 minutes of rest. The BP was then determined based on the average of 2 or more readings. The BPs were recorded by hand in a weekly log. Participants had at least 12 weeks of BP readings measured by the routine method, and these BPs were averaged over 12 weeks to yield their average routine measured BP.

Standardized protocol. Automated BP was measured according to the 2015 USPSTF Guidelines and Look AHEAD trial protocol.7,15 A participant’s arm circumference was measured, and appropriate cuff size was determined. The participant rested quietly in a chair for at least 5 minutes with feet flat on the floor and back supported. The cuff was snugly placed 2 to 3 cm above the antecubital fossa, and the arm was supported at the level of the right atrium during the measurement. Blood pressure was determined using the mean of 4 automated cuff readings, 2 on each arm, taken 1 minute apart. Participants did not necessarily have their BP measured by the standardized method immediately following the routine method but all measurements were performed during the same 12-week time period.

Home blood pressure protocol. Participants were given instructions according to the American Heart Association (AHA) recommendations for measuring home BP. Patients were instructed to use a calibrated, automated arm BP cuff. Home BP machines were not provided in advance, and each individual’s BP machine was not calibrated. They also were instructed to rest at least 5 minutes before measuring their BP. The mean home BP was determined by the cumulative average of 3 readings in the morning and evening, taken 1 minute between each reading, for a total of 6 readings/d. Participants recorded home BPs for 2 weeks before submitting their readings. Each participant affirmed clear understanding of how to measure BP by correctly demonstrating placement of the cuff 1 time under supervision.

Results

Thirty veterans aged > 65 years participated in the study. The average age (SD) was 82.7 (9.3) years. The average BMI (SD) was overweight at 29.7 kg/m2 (5.7). Most (87.6%) of the study participants had been diagnosed with hypertension prior to the study, and no new diagnoses were made as a result of the study.

Both systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BPs (DBP) measured by the standardized method were significantly lower than those by the routine method (P < .01 and P < .01, respectively) (Figure 1).

To determine the accuracy of the home BP monitors, the average routine VAGLAHS BP measure was compared with home BP results. For SBPs, there was a significant correlation coefficient of 0.91 (P < .01).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that standardized measurements of BP were lower than that of the routine method used in most office settings. These results suggest that there could be a risk of overtreatment for some patients those of whose results are higher than the SPRINT BP target of < 120/80 mm Hg. Clinicians might be treating BPs that are elevated due to improper measurement, which can lead to deleterious consequences in older adults, such as syncope and falls.16

Each participant exhibited a significantly lower BP reading with the standardized method than the routine method. The 20-point decrease in SBP and 10-point decrease in DBP are clinically significant. The routine method of measurement was intended to simulate BP measurement in outpatient settings. There is usually little time structured for rest, and because the protocol established by the AHA and other professional organizations is time consuming, it usually is not strictly followed. With guidelines proposed by JNC 8 and new findings from SPRINT, the method of BP readings should be reviewed in all clinical settings.

While changes in BP management are not necessarily immediate, the differences in recommendations proposed by SPRINT and JNC 8 can lead to confusion regarding how intensely to treat BP. These recommendations guide clinical practice, but clinicians’ best judgment ultimately determines BP management. Physicians who utilize routine office measurements likely rely on BP readings that are higher on average than are readings done under proper conditions. This leads to the prospect of overtreatment, where physicians attempt to control hypertension too aggressively, potentially leading to orthostatic hypotension, syncope, and increased risk for falls.16 With findings from SPRINT recommending even lower BPs than that by JNC 8, overtreatment risk becomes especially relevant. While BP protocol was strictly followed in SPRINT, some clinicians may not necessarily follow the same fastidious protocol.

The average differences between the home and standardized BPs were not statistically significant possibly due to the small sample size in the home BP measurements; however, the difference might represent some clinical relevance. There was a 15-point difference in SBP results between home (129 mm Hg) and standardized (115 mm Hg) measures. There also was a difference in DBP between home (69 mm Hg) and standardized (62 mm Hg) results. The close correlation between both home and BPs measured in VAGLAHS demonstrated that any difference was not due to variability in the measurement devices. Previous studies have demonstrated that home BPs are better indicators of cardiovascular risk than office BP.8

Despite lack of statistical significance, home BPs were lower than routine, which suggests that they still may be more reliable than routine office measurements. Definitive conclusions regarding the accuracy of the home BPs in the present study cannot be drawn due to the small sample size (n = 13). Further exploration with comparisons to ambulatory BP monitoring could yield more information on accuracy of home BP monitoring.

In this study’s cohort of older veterans, the average BMI was between 25 and 30 (overweight), which is a risk factor for hypertension.17 Every participant with hypertension was taking at least 1 antihypertensive medication and being actively managed. In this study, the authors accounted for other medications that may affect BP, such as α blockers used in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia.18 These could have potential elevating or lowering effects on BP measurements.

An issue in this study was the lack of adherence to home BP monitoring. Many patients forgot to bring in their records or to measure their BPs at home. The difficulties highlight real-life issues. Clinicians often request that patients monitor their BP at home, but few may actually remember, let alone keep diligent records. There are many barriers between measuring and reporting home BPs, which may prevent the usefulness of monitoring BP at home.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. There was no specific protocol for the routine method of BP measurement, as it was intended to simulate the haphazard nature of office measurements. However, this approach limits its reproducibility. For home BP monitoring, it would have been ideal to provide the same calibrated, automated BP device to each participant. This study of older veterans may not be applicable to the general population. Finally, the relatively small number of participants in the study (n = 30) may have limited power in drawing definitive conclusions.

Future Directions

For future studies, comparing the standardized method to ambulatory BP monitoring would provide more information on accuracy. In addition, the authors would like to evaluate the effect of exercise on BP measurements in the different settings: home, standardized, and routine methods.

1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29-e322.

2. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603.

3. Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(133):1-8.

4. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

5. Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al; SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥ 75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(24):2673-2682.

6. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al; Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee, American Heart Association. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans: an AHA scientific statement from the Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2005;7(2):102-109.

7. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):778-786.

8. Niiranen TJ, Hänninen MR, Johansson J, Reunanen A, Jula AM. Home-measured blood pressure is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular risk than office blood pressure: the Finn-Home study. Hypertension. 2010;55(6):1346-1351.

9. Reino-Gonzalez S, Pita-Fernández S, Seoane-Pillado T, López-Calviño B, Pértega Díaz S. How in-office and ambulatory BP monitoring compare: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Fam Pract. 2017;66(1):E5-E12.

10. Cohen JB, Cohen DL. Integrating out-of-office blood pressure in the diagnosis and management of hypertension. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(11):112.

11. Fuchs SC, Mello RB, Fuchs FC. Home blood pressure monitoring is better predictor of cardiovascular disease and target organ damage than office blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2013;15(11):413.

12. Imai Y, Obara T, Asamaya K, Ohkubo T. The reason why home blood pressure measurements are preferred over clinic or ambulatory blood pressure in Japan. Hypertens Res. 2013;36(8):661-672.

13. Bliziotis IA, Destounis A, Stergiou GS. Home versus ambulatory and office blood pressure in predicting target organ damage in hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2012;30(7):1289-1299.

14. Yang Y, Xu JZ, Wang Y, Gao PJ. Ambulatory versus clinic blood pressure in predicting overall subclinical target organ damage progression in essential hypertensive patients: a 3-year follow-up study. Blood Press Monit. 2016;21(6):319-326.

15. Espeland MA, Probstfield J, Hire D, et al; Look AHEAD Research Group; ACCORD Study Group. Systolic blood pressure control among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a comparative effectiveness analysis of three interventions. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(8):995-1009.

16. Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, et al. Benefits and harms of intensive blood pressure treatment in adults aged 60 years or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):419-429.

17. Nagai M, Ohkubo T, Murakami Y, et al; NIPPON DATA80/90/2010 Research Group. Secular trends of the impact of overweight and obesity on hypertension in Japan, 1980-2010. Hypertens Res. 2015;38(11):790-795.

18. Press Y, Punchik B, Freud T. Orthostatic hypotension and drug therapy in patients at an outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment unit. J Hypertens. 2016;34(2):351-358.

1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29-e322.

2. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-e603.

3. Nwankwo T, Yoon SS, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;(133):1-8.

4. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

5. Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al; SPRINT Research Group. Intensive vs standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥ 75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(24):2673-2682.

6. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al; Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee, American Heart Association. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans: an AHA scientific statement from the Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2005;7(2):102-109.

7. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):778-786.

8. Niiranen TJ, Hänninen MR, Johansson J, Reunanen A, Jula AM. Home-measured blood pressure is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular risk than office blood pressure: the Finn-Home study. Hypertension. 2010;55(6):1346-1351.

9. Reino-Gonzalez S, Pita-Fernández S, Seoane-Pillado T, López-Calviño B, Pértega Díaz S. How in-office and ambulatory BP monitoring compare: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Fam Pract. 2017;66(1):E5-E12.

10. Cohen JB, Cohen DL. Integrating out-of-office blood pressure in the diagnosis and management of hypertension. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(11):112.

11. Fuchs SC, Mello RB, Fuchs FC. Home blood pressure monitoring is better predictor of cardiovascular disease and target organ damage than office blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2013;15(11):413.

12. Imai Y, Obara T, Asamaya K, Ohkubo T. The reason why home blood pressure measurements are preferred over clinic or ambulatory blood pressure in Japan. Hypertens Res. 2013;36(8):661-672.

13. Bliziotis IA, Destounis A, Stergiou GS. Home versus ambulatory and office blood pressure in predicting target organ damage in hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2012;30(7):1289-1299.

14. Yang Y, Xu JZ, Wang Y, Gao PJ. Ambulatory versus clinic blood pressure in predicting overall subclinical target organ damage progression in essential hypertensive patients: a 3-year follow-up study. Blood Press Monit. 2016;21(6):319-326.

15. Espeland MA, Probstfield J, Hire D, et al; Look AHEAD Research Group; ACCORD Study Group. Systolic blood pressure control among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a comparative effectiveness analysis of three interventions. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(8):995-1009.

16. Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, et al. Benefits and harms of intensive blood pressure treatment in adults aged 60 years or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(6):419-429.

17. Nagai M, Ohkubo T, Murakami Y, et al; NIPPON DATA80/90/2010 Research Group. Secular trends of the impact of overweight and obesity on hypertension in Japan, 1980-2010. Hypertens Res. 2015;38(11):790-795.

18. Press Y, Punchik B, Freud T. Orthostatic hypotension and drug therapy in patients at an outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment unit. J Hypertens. 2016;34(2):351-358.

Eltrombopag receives priority review designation for SAA

Eltrombopag (Promacta®) in combination with standard immunosuppressive therapy (IST) has received priority review designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for first-line treatment of severe aplastic anemia (SAA).

The drug is already approved for SAA in the refractory setting for patients who have had an insufficient response to IST.

And it is approved for adults and children with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) who are refractory to other treatments and for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection who are thrombocytopenic.

Eltrombopag, an oral thrombopoietin receptor agonist, had received breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA earlier this year for use in combination with IST as first-line treatment of SAA.

The priority review designation for the agent as a first-line treatment for SAA is supported by data from a phase 1/2 trial published in NEJM in April 2017 and subsequent data on file with Novartis.

The FDA intends to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The agency grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

Trial data

Ninety-two patients with previously untreated SAA were enrolled on the trial and received IST and eltrombopag in 3 different cohorts.

Cohorts varied by start day of eltrombopag and duration of eltrombopag therapy. Patients in cohort 1 received eltrombopag from day 14 to 6 months. Patients in cohort 2 received the drug from day 14 to 3 months. And patients in cohort 3 received eltrombopag from day 1 to 6 months.

The overall response rate (ORR) at 6 months was 80% (cohort 1), 87% (cohort 2), and 94% (cohort 3).

The complete response rate at 6 months was 33%, 26%, and 58% in the 3 cohorts, respectively.

At a median follow-up of 2 years, the overall survival rate was 97%.

In the corporate announcement of the priority review designation, Novartis reported an ORR of 85% at 6 months.

Adverse events included transient elevations in liver enzyme levels (7 patients) and 2 severe adverse events—grades 2 and 3 cutaneous eruption—related to eltrombopag that resulted in patients stopping the drug.

Eltrombopag is marketed as Revolade in countries outside the US.

Eltrombopag (Promacta®) in combination with standard immunosuppressive therapy (IST) has received priority review designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for first-line treatment of severe aplastic anemia (SAA).

The drug is already approved for SAA in the refractory setting for patients who have had an insufficient response to IST.

And it is approved for adults and children with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) who are refractory to other treatments and for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection who are thrombocytopenic.

Eltrombopag, an oral thrombopoietin receptor agonist, had received breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA earlier this year for use in combination with IST as first-line treatment of SAA.

The priority review designation for the agent as a first-line treatment for SAA is supported by data from a phase 1/2 trial published in NEJM in April 2017 and subsequent data on file with Novartis.

The FDA intends to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The agency grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

Trial data

Ninety-two patients with previously untreated SAA were enrolled on the trial and received IST and eltrombopag in 3 different cohorts.

Cohorts varied by start day of eltrombopag and duration of eltrombopag therapy. Patients in cohort 1 received eltrombopag from day 14 to 6 months. Patients in cohort 2 received the drug from day 14 to 3 months. And patients in cohort 3 received eltrombopag from day 1 to 6 months.

The overall response rate (ORR) at 6 months was 80% (cohort 1), 87% (cohort 2), and 94% (cohort 3).

The complete response rate at 6 months was 33%, 26%, and 58% in the 3 cohorts, respectively.

At a median follow-up of 2 years, the overall survival rate was 97%.

In the corporate announcement of the priority review designation, Novartis reported an ORR of 85% at 6 months.

Adverse events included transient elevations in liver enzyme levels (7 patients) and 2 severe adverse events—grades 2 and 3 cutaneous eruption—related to eltrombopag that resulted in patients stopping the drug.

Eltrombopag is marketed as Revolade in countries outside the US.

Eltrombopag (Promacta®) in combination with standard immunosuppressive therapy (IST) has received priority review designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for first-line treatment of severe aplastic anemia (SAA).

The drug is already approved for SAA in the refractory setting for patients who have had an insufficient response to IST.

And it is approved for adults and children with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) who are refractory to other treatments and for patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection who are thrombocytopenic.

Eltrombopag, an oral thrombopoietin receptor agonist, had received breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA earlier this year for use in combination with IST as first-line treatment of SAA.

The priority review designation for the agent as a first-line treatment for SAA is supported by data from a phase 1/2 trial published in NEJM in April 2017 and subsequent data on file with Novartis.

The FDA intends to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The agency grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

Trial data

Ninety-two patients with previously untreated SAA were enrolled on the trial and received IST and eltrombopag in 3 different cohorts.

Cohorts varied by start day of eltrombopag and duration of eltrombopag therapy. Patients in cohort 1 received eltrombopag from day 14 to 6 months. Patients in cohort 2 received the drug from day 14 to 3 months. And patients in cohort 3 received eltrombopag from day 1 to 6 months.

The overall response rate (ORR) at 6 months was 80% (cohort 1), 87% (cohort 2), and 94% (cohort 3).

The complete response rate at 6 months was 33%, 26%, and 58% in the 3 cohorts, respectively.

At a median follow-up of 2 years, the overall survival rate was 97%.

In the corporate announcement of the priority review designation, Novartis reported an ORR of 85% at 6 months.

Adverse events included transient elevations in liver enzyme levels (7 patients) and 2 severe adverse events—grades 2 and 3 cutaneous eruption—related to eltrombopag that resulted in patients stopping the drug.

Eltrombopag is marketed as Revolade in countries outside the US.

Equal treatment, equal or better prostate cancer outcomes for black men

CHICAGO – Black men with advanced prostate cancer have survival with chemotherapy that rivals or surpasses that of white men with advanced disease, and black men with castration-resistant prostate cancer have better outcomes with abiraterone than white men.

Those conclusions come from two studies presented here at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Taken together, they suggest that although there may be genetic or biologic differences in cancer presentation among different racial groups, receiving the appropriate care can level out those differences.

In the first study, Susan Halabi, PhD, from Duke University in Durham, N.C., and colleagues pooled data from nine randomized phase 3 chemotherapy trials in men with advanced prostate cancer and found that black and white men had the same median survival, 21 months, but black men had an adjusted hazard ratio [HR} for death of 0.81, compared with white men.

For the subpopulation of African Americans who were enrolled in trials funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the HR for death was 0.76 (P less than .0001).

“The bottom line, in a sense, is that African American men with advanced prostate cancer need to get to an oncologist and ideally need to get on a clinical trial, and if they do, their outcomes are every bit as good as Caucasian men, if not even a little bit better,” Richard Schilsky, MD, chief medical officer of ASCO, said at a briefing prior to presentation of the studies.

In the second study, a prospective clinical trial of abiraterone (Zytiga) in 100 men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), black men were more likely to have a decline in prostate-specific antigen (PSA), and a longer median time to PSA rise than white men (16.6 vs. 11.5 months), reported Daniel George, MD, also from Duke.

“There’s a 1.6 times greater likelihood that African Americans are diagnosed with prostate cancer, but a 2.4 times greater chance they die from that disease, and although there very well may be multi-factorial reasons for that, I think some of this is genetic,” he said.

Pooled analysis

In the United States, black men are more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their 40s and 50s than white men and are often diagnosed with advanced-stage and higher grade cancers. Black men also have double the rate of prostate cancer-specific deaths as white men.

Black men, however, are underrepresented in clinical trials, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about racial differences due to small sample sizes.

To overcome this problem, Dr. Halabi and colleagues pooled data on 8,452 patients with mCRPC - including 7,528 white men and 500 African American men – from nine randomized phase 3 trials of docetaxel and prednisone or a regimen containing those agents.

Median overall survival, the primary endpoint, was 21.0 months for black men and 21.2 months for white men.

In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, PSA, performance status, alkaline phosphatase, hemoglobin, and metastatic sites, the pooled hazard ratio (HR) for black vs. white men was 0.81 (P = .001) for all patients in the study, and when the analysis was restricted to those patients who received only docetaxel and prednisone (4,172), the results were similar, Dr. Halabi said.

“I would argue that what this tells us is pretty striking: that African-American men have potentially better survival by getting conventional therapy,” commented ASCO expert Robert Dreicer, MD, MS, from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

“The nihilism associated with prostate cancer in African-American men is not supported by this really interesting work,” he continued. “What it says to us is when we treat those with bad prostate cancer, African Americans, they do well.”

Abiraterone Study

In the abiraterone study, 50 men who self-identified as white and 50 as black were enrolled and treated with abiraterone acetate and prednisone until disease progression or intolerable toxicity.

Radiographic progression-free survival, the primary endpoint, was 16.8 months in each group. As previously noted, however, median PFS was 16.6 months for black patients, vs. 11.5 months for white men. Black men also had a longer median PSA PFS, with 82% of black men having a 30% or greater PSA decline, compared with 78% of white patients. Respective proportions of men having higher declines were 74% vs. 66% experiencing a PSA decline of at least 50%, and 48% vs. 38% having a decline of at least 90%.

Rates of tumor flare, however, were higher among African Americans, at 16% vs. 4%.

Adverse event rates were generally similar between the study arms, although more white than black patients experienced fatigue, and more black than white patients had hypokalemia.

Single-nucletoide polymorphism (SNP) profiling showed differences between the two groups in key genes involved in androgen metabolism and transport, which may explain the improved responses to abiraterone among African Americans.

“We talk about access to care; we have now demonstrated that if you treat African Americans with standard-of-care drugs for advanced prostate cancer, there’s compelling evidence that they respond as well or maybe better than white men,” Dr. Dreicer commented.

“[We are] beginning to understand the differences that drive differential responses,” he continued. “When African-American men are under-represented in clinical trials, the trial outcomes might be different, frankly, because people respond differently to drugs. I think those are the take homes.”

SOURCE: Halabi et al, George et al. ASCO 2018 Abstracts LBA5005 and LBA5009

CHICAGO – Black men with advanced prostate cancer have survival with chemotherapy that rivals or surpasses that of white men with advanced disease, and black men with castration-resistant prostate cancer have better outcomes with abiraterone than white men.

Those conclusions come from two studies presented here at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Taken together, they suggest that although there may be genetic or biologic differences in cancer presentation among different racial groups, receiving the appropriate care can level out those differences.

In the first study, Susan Halabi, PhD, from Duke University in Durham, N.C., and colleagues pooled data from nine randomized phase 3 chemotherapy trials in men with advanced prostate cancer and found that black and white men had the same median survival, 21 months, but black men had an adjusted hazard ratio [HR} for death of 0.81, compared with white men.

For the subpopulation of African Americans who were enrolled in trials funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the HR for death was 0.76 (P less than .0001).

“The bottom line, in a sense, is that African American men with advanced prostate cancer need to get to an oncologist and ideally need to get on a clinical trial, and if they do, their outcomes are every bit as good as Caucasian men, if not even a little bit better,” Richard Schilsky, MD, chief medical officer of ASCO, said at a briefing prior to presentation of the studies.

In the second study, a prospective clinical trial of abiraterone (Zytiga) in 100 men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), black men were more likely to have a decline in prostate-specific antigen (PSA), and a longer median time to PSA rise than white men (16.6 vs. 11.5 months), reported Daniel George, MD, also from Duke.

“There’s a 1.6 times greater likelihood that African Americans are diagnosed with prostate cancer, but a 2.4 times greater chance they die from that disease, and although there very well may be multi-factorial reasons for that, I think some of this is genetic,” he said.

Pooled analysis

In the United States, black men are more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their 40s and 50s than white men and are often diagnosed with advanced-stage and higher grade cancers. Black men also have double the rate of prostate cancer-specific deaths as white men.

Black men, however, are underrepresented in clinical trials, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about racial differences due to small sample sizes.

To overcome this problem, Dr. Halabi and colleagues pooled data on 8,452 patients with mCRPC - including 7,528 white men and 500 African American men – from nine randomized phase 3 trials of docetaxel and prednisone or a regimen containing those agents.

Median overall survival, the primary endpoint, was 21.0 months for black men and 21.2 months for white men.

In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, PSA, performance status, alkaline phosphatase, hemoglobin, and metastatic sites, the pooled hazard ratio (HR) for black vs. white men was 0.81 (P = .001) for all patients in the study, and when the analysis was restricted to those patients who received only docetaxel and prednisone (4,172), the results were similar, Dr. Halabi said.

“I would argue that what this tells us is pretty striking: that African-American men have potentially better survival by getting conventional therapy,” commented ASCO expert Robert Dreicer, MD, MS, from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

“The nihilism associated with prostate cancer in African-American men is not supported by this really interesting work,” he continued. “What it says to us is when we treat those with bad prostate cancer, African Americans, they do well.”

Abiraterone Study

In the abiraterone study, 50 men who self-identified as white and 50 as black were enrolled and treated with abiraterone acetate and prednisone until disease progression or intolerable toxicity.

Radiographic progression-free survival, the primary endpoint, was 16.8 months in each group. As previously noted, however, median PFS was 16.6 months for black patients, vs. 11.5 months for white men. Black men also had a longer median PSA PFS, with 82% of black men having a 30% or greater PSA decline, compared with 78% of white patients. Respective proportions of men having higher declines were 74% vs. 66% experiencing a PSA decline of at least 50%, and 48% vs. 38% having a decline of at least 90%.

Rates of tumor flare, however, were higher among African Americans, at 16% vs. 4%.

Adverse event rates were generally similar between the study arms, although more white than black patients experienced fatigue, and more black than white patients had hypokalemia.

Single-nucletoide polymorphism (SNP) profiling showed differences between the two groups in key genes involved in androgen metabolism and transport, which may explain the improved responses to abiraterone among African Americans.

“We talk about access to care; we have now demonstrated that if you treat African Americans with standard-of-care drugs for advanced prostate cancer, there’s compelling evidence that they respond as well or maybe better than white men,” Dr. Dreicer commented.

“[We are] beginning to understand the differences that drive differential responses,” he continued. “When African-American men are under-represented in clinical trials, the trial outcomes might be different, frankly, because people respond differently to drugs. I think those are the take homes.”

SOURCE: Halabi et al, George et al. ASCO 2018 Abstracts LBA5005 and LBA5009

CHICAGO – Black men with advanced prostate cancer have survival with chemotherapy that rivals or surpasses that of white men with advanced disease, and black men with castration-resistant prostate cancer have better outcomes with abiraterone than white men.

Those conclusions come from two studies presented here at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Taken together, they suggest that although there may be genetic or biologic differences in cancer presentation among different racial groups, receiving the appropriate care can level out those differences.

In the first study, Susan Halabi, PhD, from Duke University in Durham, N.C., and colleagues pooled data from nine randomized phase 3 chemotherapy trials in men with advanced prostate cancer and found that black and white men had the same median survival, 21 months, but black men had an adjusted hazard ratio [HR} for death of 0.81, compared with white men.

For the subpopulation of African Americans who were enrolled in trials funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the HR for death was 0.76 (P less than .0001).

“The bottom line, in a sense, is that African American men with advanced prostate cancer need to get to an oncologist and ideally need to get on a clinical trial, and if they do, their outcomes are every bit as good as Caucasian men, if not even a little bit better,” Richard Schilsky, MD, chief medical officer of ASCO, said at a briefing prior to presentation of the studies.

In the second study, a prospective clinical trial of abiraterone (Zytiga) in 100 men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), black men were more likely to have a decline in prostate-specific antigen (PSA), and a longer median time to PSA rise than white men (16.6 vs. 11.5 months), reported Daniel George, MD, also from Duke.

“There’s a 1.6 times greater likelihood that African Americans are diagnosed with prostate cancer, but a 2.4 times greater chance they die from that disease, and although there very well may be multi-factorial reasons for that, I think some of this is genetic,” he said.

Pooled analysis

In the United States, black men are more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their 40s and 50s than white men and are often diagnosed with advanced-stage and higher grade cancers. Black men also have double the rate of prostate cancer-specific deaths as white men.

Black men, however, are underrepresented in clinical trials, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about racial differences due to small sample sizes.

To overcome this problem, Dr. Halabi and colleagues pooled data on 8,452 patients with mCRPC - including 7,528 white men and 500 African American men – from nine randomized phase 3 trials of docetaxel and prednisone or a regimen containing those agents.

Median overall survival, the primary endpoint, was 21.0 months for black men and 21.2 months for white men.

In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, PSA, performance status, alkaline phosphatase, hemoglobin, and metastatic sites, the pooled hazard ratio (HR) for black vs. white men was 0.81 (P = .001) for all patients in the study, and when the analysis was restricted to those patients who received only docetaxel and prednisone (4,172), the results were similar, Dr. Halabi said.

“I would argue that what this tells us is pretty striking: that African-American men have potentially better survival by getting conventional therapy,” commented ASCO expert Robert Dreicer, MD, MS, from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

“The nihilism associated with prostate cancer in African-American men is not supported by this really interesting work,” he continued. “What it says to us is when we treat those with bad prostate cancer, African Americans, they do well.”

Abiraterone Study

In the abiraterone study, 50 men who self-identified as white and 50 as black were enrolled and treated with abiraterone acetate and prednisone until disease progression or intolerable toxicity.

Radiographic progression-free survival, the primary endpoint, was 16.8 months in each group. As previously noted, however, median PFS was 16.6 months for black patients, vs. 11.5 months for white men. Black men also had a longer median PSA PFS, with 82% of black men having a 30% or greater PSA decline, compared with 78% of white patients. Respective proportions of men having higher declines were 74% vs. 66% experiencing a PSA decline of at least 50%, and 48% vs. 38% having a decline of at least 90%.

Rates of tumor flare, however, were higher among African Americans, at 16% vs. 4%.

Adverse event rates were generally similar between the study arms, although more white than black patients experienced fatigue, and more black than white patients had hypokalemia.

Single-nucletoide polymorphism (SNP) profiling showed differences between the two groups in key genes involved in androgen metabolism and transport, which may explain the improved responses to abiraterone among African Americans.

“We talk about access to care; we have now demonstrated that if you treat African Americans with standard-of-care drugs for advanced prostate cancer, there’s compelling evidence that they respond as well or maybe better than white men,” Dr. Dreicer commented.

“[We are] beginning to understand the differences that drive differential responses,” he continued. “When African-American men are under-represented in clinical trials, the trial outcomes might be different, frankly, because people respond differently to drugs. I think those are the take homes.”

SOURCE: Halabi et al, George et al. ASCO 2018 Abstracts LBA5005 and LBA5009

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2018

Key clinical point: Apparent racial disparities in prostate cancer care may be reduced or eliminated with proper care and access to clinical trials.

Major finding: In a pooled analysis, black men with advanced prostate cancer treated with docetaxel prednisone had a 19% lower risk for death than white men,

Study details: Pooled analysis of 9 randomized phase III trials with a total of 8,452 men and a prospective trial with 100 men with advanced prostate cancer.

Disclosures: The study by Halabi et al was funded by Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs. The study by George et al was funded by Janssen. Dr. Halabi disclosed a consulting or advisory role with Tokai Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, and Bayer, and travel expenses from Bayer. Dr. George disclosed consulting/advising with Janssen and several other pharmaceutical companies, in addition to speakers’ bureau, travel expenses, and honoraria from various companies. He has also received institutional research funding from Exelixis, Genentech/Roche, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Millennium, Acerta Pharma, Bayer, Dendreon, and Innocrin Pharma.

Source: Halabi et al, George et al. ASCO 2018 Abstracts LBA5005 and LBA5009.

Post-traumatic osteoarthritis needs to be prevention focus

, Jackie Whittaker, PT, PhD, said at the World Congress of Osteoarthritis.

“We all know that the burden of this disease is enormous and it’s expanding at an alarming rate,” she said at the congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

“The only way that we have at this moment to try to reduce the burden of this disease is to shift our approach to management upstream and focus on prevention,” said Dr. Whittaker, who is an associate professor and research director at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.

According to the World Health Organization, OA is expected to become the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide by 2020. Furthermore, there will be a projected rise in prevalence from 12% to 25% in North America by 2030.

Dr. Whittaker suggested that it was time to try to identify those at risk of developing OA, such as after a joint injury, and ran through some suggestions on how posttraumatic OA (PTOA) might be preventable.

Secondary prevention of posttraumatic osteoarthritis

The prevention of PTOA can be split into primary, secondary and tertiary prevention, with primary prevention trying to prevent injuries from occurring in the first place.

“Strategies aimed at identifying and slowing down the onset of symptomatic osteoarthritis in preclinical populations would be referred to as secondary prevention,” Dr. Whittaker explained, adding that tertiary prevention would then be strategies aimed at improving function and reducing disability in those who already have symptomatic PTOA.

While there are programs that address primary and tertiary prevention – such as Footy First, an exercise training program adopted by the Australian Football League to reduce the risk of common leg injuries and the Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D®) education and supervised exercise program for those with symptomatic OA – there is more of a gap for secondary prevention.

Some of the first steps to developing a secondary prevention model would be to determine the extent of PTOA after joint injury and then identify risk factors or causal mechanisms. Then, prevention strategies could be developed and tested before implementation and effectiveness studies are performed.

Performing the necessary prospective cohort studies, however, is when things get challenging – PTOA can take 10–15 years to manifest and studies would potentially need to run for long periods of time, which comes at a cost. Other challenges are that there is no commonly agree definition. PTOA is multifactorial, and because people may be in their 20s, there could be other contributing factors to the disease course.

Identifying modifiable risk factors

There are a “fair number” of prospective and retrospective studies that have been done to try to identify patients at risk for OA after joint injury. Several have looked at unmodifiable risk factors, such as age and sex, and the type of injury. Others have looked at potentially modifiable factors such as the treatment approach and avoiding re-injury, joint mechanics and strength, body composition and aerobic fitness and behavioral characteristics such as physical activity and return to sport.