User login

Tardive dyskinesia: Screening and management

The DNA of psychiatric practice: A covenant with our patients

As the end of the academic year approaches, I always think of one last message to send to the freshly minted psychiatrists who will complete their 4 years of post-MD training. This year, I thought of emphasizing the principles of psychiatric practice, which the graduates will deliver for the next 4 to 5 decades of their professional lives. Those essential principles are coded in the DNA of psychiatric practice, just as the construction of all organs in the human body is coded within the DNA of the 22,000 genes that comprise our 23 chromosomes.

So here are the principles of psychiatry that I propose govern the relationship of psychiatrists with their patients, encrypted within the DNA of our esteemed medical specialty:

- Provide total dedication to helping psychiatric patients recover from their illness and regain their wellness.

- Maintain total and unimpeachable confidentiality.

- Demonstrate unconditional acceptance and respect to every patient.

- Adopt a nonjudgmental stance toward all patients.

- Establish a strong therapeutic alliance as early as possible. It is the center of the doctor–patient relationship.

- Provide the same standard of care to all patients—the same care you would want your family members to receive.

- Provide evidence-based treatments first, and if no response, use unapproved treatments judiciously, but above all, do no harm.

- Educate patients, and their families, about the illness, and discuss the benefits and risks of various treatments.

- Do not practice “naked psychopharmacology.” Psychotherapy must always be provided side-by-side with medications.

- Support the patient’s family. Their burden often is very heavy.

- Emphasize adherence as a key patient responsibility, and address it at every visit.

- Do not hesitate to consult a seasoned colleague about your complex clinical cases.

- Deal effectively with negative countertransference. Recognize it, and refer the patient to another colleague if you cannot resolve it.

- Always inquire about thoughts of harming self or others and act accordingly.

- Always ask about alcohol and substance use, and about over-the-counter drugs as well. They all can complicate your patient’s treatment course and outcome.

- Never breach boundaries with your patient, and firmly guide the patient about breaching boundaries with you.

- Uphold the medical tenet that all “mental” disorders of thought, mood, affect, behavior, and cognition are generated by disruptions of brain structure and/or function, whether molecular, cellular, or connectomic, caused by various combinations of genetic and/or environmental etiologies.

- Check your patients’ physical health status, including all treatments they received from other specialists, and always rule out iatrogenesis and disruptive pharmacokinetic interactions that may trigger or exacerbate psychiatric symptoms.

- Learn and use clinical rating scales to quantify symptom severity and adverse effects at baseline and at each visit. Measuring the severity of psychosis, depression, or anxiety in psychiatry is like measuring fasting glucose, triglycerides, or blood pressure in internal medicine.

- Use rational adjunctive and augmentation therapies when indicated, but avoid irrational and hazardous polypharmacy.

- Document your clinical findings, diagnosis, and treatment plan conscientiously and accurately. The medical record is a clinical, billing, legal, and research document.

- Advocate tirelessly for psychiatric patients to increase their access to care, and fight the unfair and hurtful stigma vigorously until it is completely erased. A psychiatric disorder should have no more stigma than a broken leg or peptic ulcer, and insurance parity must be identical as well.

- Establish collaborative care for each of your patients and link them to a primary care provider if they do not already have one. Disorders of the body and the brain are bidirectional in their effects and psychiatric patients often suffer from multiple organ diseases.

- Do some pro bono care for indigent or uninsured patients, and actively ask companies to provide free drugs to patients who cannot afford the medication you believe they need.

- Recognize that every treatment you use as the current standard of care was at one time a research project. Know that the research of today is the treatment of tomorrow. So support the creation of new medical knowledge by referring patients to FDA clinical trials or to National Institutes of Health–funded biologic investigations.

- No matter how busy you are, write a case report or a letter to the editor about an unusual response or adverse effect. This generates hypotheses that researchers can pursue and test.

- Volunteer to serve as a clinical supervisor for medical students and residents from your local medical school. Most academic departments of psychiatry appreciate their community-based volunteer faculty.

You, the readers of

As the end of the academic year approaches, I always think of one last message to send to the freshly minted psychiatrists who will complete their 4 years of post-MD training. This year, I thought of emphasizing the principles of psychiatric practice, which the graduates will deliver for the next 4 to 5 decades of their professional lives. Those essential principles are coded in the DNA of psychiatric practice, just as the construction of all organs in the human body is coded within the DNA of the 22,000 genes that comprise our 23 chromosomes.

So here are the principles of psychiatry that I propose govern the relationship of psychiatrists with their patients, encrypted within the DNA of our esteemed medical specialty:

- Provide total dedication to helping psychiatric patients recover from their illness and regain their wellness.

- Maintain total and unimpeachable confidentiality.

- Demonstrate unconditional acceptance and respect to every patient.

- Adopt a nonjudgmental stance toward all patients.

- Establish a strong therapeutic alliance as early as possible. It is the center of the doctor–patient relationship.

- Provide the same standard of care to all patients—the same care you would want your family members to receive.

- Provide evidence-based treatments first, and if no response, use unapproved treatments judiciously, but above all, do no harm.

- Educate patients, and their families, about the illness, and discuss the benefits and risks of various treatments.

- Do not practice “naked psychopharmacology.” Psychotherapy must always be provided side-by-side with medications.

- Support the patient’s family. Their burden often is very heavy.

- Emphasize adherence as a key patient responsibility, and address it at every visit.

- Do not hesitate to consult a seasoned colleague about your complex clinical cases.

- Deal effectively with negative countertransference. Recognize it, and refer the patient to another colleague if you cannot resolve it.

- Always inquire about thoughts of harming self or others and act accordingly.

- Always ask about alcohol and substance use, and about over-the-counter drugs as well. They all can complicate your patient’s treatment course and outcome.

- Never breach boundaries with your patient, and firmly guide the patient about breaching boundaries with you.

- Uphold the medical tenet that all “mental” disorders of thought, mood, affect, behavior, and cognition are generated by disruptions of brain structure and/or function, whether molecular, cellular, or connectomic, caused by various combinations of genetic and/or environmental etiologies.

- Check your patients’ physical health status, including all treatments they received from other specialists, and always rule out iatrogenesis and disruptive pharmacokinetic interactions that may trigger or exacerbate psychiatric symptoms.

- Learn and use clinical rating scales to quantify symptom severity and adverse effects at baseline and at each visit. Measuring the severity of psychosis, depression, or anxiety in psychiatry is like measuring fasting glucose, triglycerides, or blood pressure in internal medicine.

- Use rational adjunctive and augmentation therapies when indicated, but avoid irrational and hazardous polypharmacy.

- Document your clinical findings, diagnosis, and treatment plan conscientiously and accurately. The medical record is a clinical, billing, legal, and research document.

- Advocate tirelessly for psychiatric patients to increase their access to care, and fight the unfair and hurtful stigma vigorously until it is completely erased. A psychiatric disorder should have no more stigma than a broken leg or peptic ulcer, and insurance parity must be identical as well.

- Establish collaborative care for each of your patients and link them to a primary care provider if they do not already have one. Disorders of the body and the brain are bidirectional in their effects and psychiatric patients often suffer from multiple organ diseases.

- Do some pro bono care for indigent or uninsured patients, and actively ask companies to provide free drugs to patients who cannot afford the medication you believe they need.

- Recognize that every treatment you use as the current standard of care was at one time a research project. Know that the research of today is the treatment of tomorrow. So support the creation of new medical knowledge by referring patients to FDA clinical trials or to National Institutes of Health–funded biologic investigations.

- No matter how busy you are, write a case report or a letter to the editor about an unusual response or adverse effect. This generates hypotheses that researchers can pursue and test.

- Volunteer to serve as a clinical supervisor for medical students and residents from your local medical school. Most academic departments of psychiatry appreciate their community-based volunteer faculty.

You, the readers of

As the end of the academic year approaches, I always think of one last message to send to the freshly minted psychiatrists who will complete their 4 years of post-MD training. This year, I thought of emphasizing the principles of psychiatric practice, which the graduates will deliver for the next 4 to 5 decades of their professional lives. Those essential principles are coded in the DNA of psychiatric practice, just as the construction of all organs in the human body is coded within the DNA of the 22,000 genes that comprise our 23 chromosomes.

So here are the principles of psychiatry that I propose govern the relationship of psychiatrists with their patients, encrypted within the DNA of our esteemed medical specialty:

- Provide total dedication to helping psychiatric patients recover from their illness and regain their wellness.

- Maintain total and unimpeachable confidentiality.

- Demonstrate unconditional acceptance and respect to every patient.

- Adopt a nonjudgmental stance toward all patients.

- Establish a strong therapeutic alliance as early as possible. It is the center of the doctor–patient relationship.

- Provide the same standard of care to all patients—the same care you would want your family members to receive.

- Provide evidence-based treatments first, and if no response, use unapproved treatments judiciously, but above all, do no harm.

- Educate patients, and their families, about the illness, and discuss the benefits and risks of various treatments.

- Do not practice “naked psychopharmacology.” Psychotherapy must always be provided side-by-side with medications.

- Support the patient’s family. Their burden often is very heavy.

- Emphasize adherence as a key patient responsibility, and address it at every visit.

- Do not hesitate to consult a seasoned colleague about your complex clinical cases.

- Deal effectively with negative countertransference. Recognize it, and refer the patient to another colleague if you cannot resolve it.

- Always inquire about thoughts of harming self or others and act accordingly.

- Always ask about alcohol and substance use, and about over-the-counter drugs as well. They all can complicate your patient’s treatment course and outcome.

- Never breach boundaries with your patient, and firmly guide the patient about breaching boundaries with you.

- Uphold the medical tenet that all “mental” disorders of thought, mood, affect, behavior, and cognition are generated by disruptions of brain structure and/or function, whether molecular, cellular, or connectomic, caused by various combinations of genetic and/or environmental etiologies.

- Check your patients’ physical health status, including all treatments they received from other specialists, and always rule out iatrogenesis and disruptive pharmacokinetic interactions that may trigger or exacerbate psychiatric symptoms.

- Learn and use clinical rating scales to quantify symptom severity and adverse effects at baseline and at each visit. Measuring the severity of psychosis, depression, or anxiety in psychiatry is like measuring fasting glucose, triglycerides, or blood pressure in internal medicine.

- Use rational adjunctive and augmentation therapies when indicated, but avoid irrational and hazardous polypharmacy.

- Document your clinical findings, diagnosis, and treatment plan conscientiously and accurately. The medical record is a clinical, billing, legal, and research document.

- Advocate tirelessly for psychiatric patients to increase their access to care, and fight the unfair and hurtful stigma vigorously until it is completely erased. A psychiatric disorder should have no more stigma than a broken leg or peptic ulcer, and insurance parity must be identical as well.

- Establish collaborative care for each of your patients and link them to a primary care provider if they do not already have one. Disorders of the body and the brain are bidirectional in their effects and psychiatric patients often suffer from multiple organ diseases.

- Do some pro bono care for indigent or uninsured patients, and actively ask companies to provide free drugs to patients who cannot afford the medication you believe they need.

- Recognize that every treatment you use as the current standard of care was at one time a research project. Know that the research of today is the treatment of tomorrow. So support the creation of new medical knowledge by referring patients to FDA clinical trials or to National Institutes of Health–funded biologic investigations.

- No matter how busy you are, write a case report or a letter to the editor about an unusual response or adverse effect. This generates hypotheses that researchers can pursue and test.

- Volunteer to serve as a clinical supervisor for medical students and residents from your local medical school. Most academic departments of psychiatry appreciate their community-based volunteer faculty.

You, the readers of

The Goldwater Rule and free speech, the current 'political morass', and more

In his editorial, “The toxic zeitgeist of hyper-partisanship: A psychiatric perspective” (From the Editor,

One’s political views do not inform us of his or her mental health status. This appreciation can be obtained only by a thorough psychological assessment. This is the basis of the Goldwater Rule, coupled with the ethical responsibility not to discuss patients’ private communications.

Today, this rule is tested by the behavior and actions of President Donald Trump. Proponents of the Goldwater Rule state that a psychiatrist cannot diagnose someone without performing a face-to-face diagnostic evaluation. This assumes psychiatrists diagnose patients only by interviewing them. However, any psychiatrist who has worked in an emergency room has signed involuntary commitment papers for a patient who refuses to talk to them. This clinical action typically is based on reports of the patient’s potential dangerousness from family, friends, or the police.

The diagnostic criteria for some personality disorders are based only on observed or reported behavior. They do not indicate a need for an interview. The diagnosis of a personality disorder cannot be made solely by interviewing an individual without knowledge of his or her behavior. Interviewing Bernie Madoff would not have revealed his sociopathic behavior.

The critical question may not be whether one could ethically make a psychiatric diagnosis of the President (I believe you can), but rather would it indicate or imply that he is dangerous? History informs us that the existence of a psychiatric disorder does not determine a politician’s fitness for office or if they are dangerous. Behavioral accounts of President Abraham Lincoln and his self-reports seem to confirm that at times he was depressed, but he clearly served our country with distinction.

Finally, it is not clear whether the Goldwater Rule is legal. It arguably interferes with a psychiatrist’s right of free speech without the risk of being accused of unethical behavior. I wonder what would happen if it were tested in court. Does the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protect a psychiatrist’s right to speak freely?

Sidney Weissman, MD

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science

Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern University

Chicago, Illinois

The current ‘political morass’

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah, for the wonderful synopsis of the current political morass in your editorial (From the Editor,

James Gallagher, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Des Moines, Iowa

Continue to: The biological etiology of compulsive sexual behavior

The biological etiology of compulsive sexual behavior

Dr. Grant’s article, “Compulsive sexual behavior: A nonjudgmental approach” (Evidence-Based Reviews,

Mukesh Sanghadia, MD, MRCPsych (UK), Diplomate ABPN

PsychiatristCommunity Research Foundation

San Diego, California

The author responds

Dr. Sanghadia highlights the lack of possible biological etiology of compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) in my article. This is a fair comment. The lack of agreed-upon diagnostic criteria, however, has resulted in a vast literature discussing sexual behaviors that may or may not be related to each other, and even suggest that what is currently referred to as CSB may in fact be quite heterogeneous. My article mentions the few neuroimaging and neurocognitive studies that address a more rigorously defined CSB. Other possible etiologies have been suggested for a range of out-of-control sexual behaviors, but have not been studied with a focus on this formal diagnostic category. For example, endocrine issues have been explored to some extent in individuals with paraphilic sexual behaviors (behaviors that appear to many to have no relationship to CSB as discussed in my article), and in those cases of paraphilic sexual behavior, a range of endocrine hormones have been examined—gonadotropin-releasing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, testosterone/dihydrotestosterone, and estrogen/progesterone. But these studies have yielded no conclusive outcomes in terms of findings or treatments.

In summary, the biology of CSB lags far behind that of other mental health disorders (and even other psychiatric disorders lack conclusive biological etiologies). Establishing this behavior as a legitimate diagnostic entity with agreed-upon criteria may be the first step in furthering our understanding of its possible biology.

Jon E. Grant, JD, MD, MPH

Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine

Chicago, Illinois

Continue to: A different view of patients with schizophrenia

A different view of patients with schizophrenia

After treating patients with schizophrenia for more than 30 years, I’ve observed a continuous flood of information about them. This overload has been consistent since my residency back in the 1980s. Theories ranging from the psychoanalytic to the biologic are numerous and valuable additions to our understanding of those who suffer with this malady, yet they provide no summation or overview with which to understand it.

For instance, we know that schizophrenia usually begins in the late teens or early twenties. We know that antidopaminergic medications usually help to varying degrees. Psychosocial interventions may contribute greatly to the ultimate outcome. Substance use invariably makes it worse. Establishing a connection with the patient can often be helpful. Medication compliance is crucial.

It is more or less accepted that there is deterioration of higher brain functions, hypofrontality, as well as so-called dysconnectivity of white matter. There is a genetic vulnerability, and there seems to be an excess of inflammation and changes in mitochondria. Most patients have low functioning, poor compensation, and a lack of social adeptness. However, some patients can recover quite nicely. Although most of us would agree that this is not dementia, we’d also concede that these patients’ cognitive functioning is not what it used to be. Electroconvulsive therapy also can sometimes be helpful.

So, how are we to view our patients with schizophrenia in a way that can be illuminating and give us a deeper sense of understanding this quizzical disorder? It has been helpful to me to regard these individuals as a people whose brain function has been usurped by a more primitive organization that is characterized by:

- a reduction in mental development, where patients function in a more childlike way with magical thinking and impaired reality-testing

- atrophy of higher brain structures, leading to hallucinatory experiences

- a hyper-dominergic state

- a usually gradual onset with some evidence of struggle between the old and new brain organizations

- impaired prepulse inhibition that’s likely secondary to diffuseness of thought

- eventual demise of higher brain structures with an inability to respond to anti-dopaminergics. (Antipsychotics can push the brain organization closer to the adult structure attained before the onset of the disease, at least initially.)

The list goes on. Thinking about patients with schizophrenia in this way allows me to appreciate what I feel is a more encompassing view of who they are and how they got there. I have some theories about where this more primitive organization may have originated, but whatever its origin, in a small percentage of people it is there, ready to assume control of their thinking just as they are reaching reproductive age. Early intervention and medication compliance may minimize damage.

If a theory helps us gain a greater understanding of our patients, then it’s worth considering. This proposition fits much of what we know about schizophrenia. Reading patients’ firsthand accounts of the illness helps confirm, in my opinion, this point of view.

Steven Lesk, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Fridley, Minnesota

Continue to: Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia

Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia

The authors of “Suspicious, sleepless, and smoking” (Cases That Test Your Skills,

During the past 15 years, I have routinely measured cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Some have no impairment, some have severe impairment, and some fall in between these extremes. Most often, impairment occurs in the area of executive function, which can lead to significant disability. Indeed, positive symptoms can clear up completely with treatment, but the deficits in executive functioning can remain.

I think it is fair to say that cognitive impairment is a common, although not nearly universal, feature of schizophrenia that sometimes improves with antipsychotic medication. I look forward to the advent of more clinicians paying attention to the issue of cognition in schizophrenia and, hopefully, better treatments for it.

John M. Mahoney, PhD

Shasta Psychiatric Hospital

Redding, California

The authors respond

We thank Dr. Mahoney for his thoughtful letter and queries into the case of Mr. F.

First, regarding the prevalence of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia, it is our opinion that cognitive impairment is a distinct, core, and nearly universal feature of schizophrenia. This also is the conclusion of many clinicians and researchers based on their significant work in the field; still, just as in our initial case study, we concede that these symptoms are not part of the DSM-5’s formal diagnostic criteria.

The core question Dr. Mahoney seems to pose is whether we contradicted ourselves. We assert that cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is not effectively treated with existing medications, and yet we described Mr. F’s cognitive improvement after he received risperidone, 2 mg/d, titrated up to 2 mg twice daily. We first pointed out that part of our treatment strategy was to target comorbid depression in this patient; nonetheless, Dr. Mahoney’s question remains valid, and we will attempt to answer.

Dr. Mahoney has observed that his patients with schizophrenia variably experience improved cognition, and notes that executive function is a particularly common lingering impairment. On this we wholly agree; this is a helpful point of clarification, and a useful distinction in light of the above question. Improvement in positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, as psychosis resolves, is a well-known and studied effect of antipsychotic therapy. As a result, the sensorium becomes more congruent with external reality, and one would expect the patient to display improved orientation. This then might be reasonably expected to produce mental status improvements; however, while some improvement is frequently observed, this is neither consistent nor complete improvement. In the case of Mr. F, we document improvement, but also significant continued impairment. Thus, we maintain that treating the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia with antipsychotics has been largely ineffective.

We do not see this as a slight distinction or an argument of minutiae. That patients frequently experience some degree of lingering impairment is a salient point. Neurocognitive impairment is a strong contributor to and predictor of disability in schizophrenia, and neurocognitive abilities most strongly predict functional outcomes. From a patient’s point of view, these symptoms have real-world consequences. Thus, we believe they should be evaluated and treated as aggressively and consistently as other schizophrenia symptoms.

In our case, we attempted to convey one primary message: Despite the challenges of treatment, there are viable options that should be pursued in the treatment of schizophrenia-related cognitive impairments. Nonpharmacologic modalities have shown encouraging results. Cognitive remediation therapy produces durable cognitive improvement—especially when combined with adjunctive therapies, such as small group therapy and vocational rehabilitation, and when comorbid conditions (major depressive disorder in Mr. F’s case) are treated.

In summary, we reiterate that cognitive impairments in schizophrenia represent a strong predictor of patient-oriented outcomes; we maintain our assertion regarding their inadequate treatment with existing medications; and we suggest that future trials attempt to find effective alternative strategies. We encourage psychiatric clinicians to approach treatment of this facet of pathology with an open mind, and to utilize alternative multi-modal therapies for the benefit of their patients with schizophrenia while waiting for new safe and effective pharmaceutical regimens.

Jarrett Dawson, MD

Family medicine resident

Department of Psychiatry

Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

Catalina Belean, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

In his editorial, “The toxic zeitgeist of hyper-partisanship: A psychiatric perspective” (From the Editor,

One’s political views do not inform us of his or her mental health status. This appreciation can be obtained only by a thorough psychological assessment. This is the basis of the Goldwater Rule, coupled with the ethical responsibility not to discuss patients’ private communications.

Today, this rule is tested by the behavior and actions of President Donald Trump. Proponents of the Goldwater Rule state that a psychiatrist cannot diagnose someone without performing a face-to-face diagnostic evaluation. This assumes psychiatrists diagnose patients only by interviewing them. However, any psychiatrist who has worked in an emergency room has signed involuntary commitment papers for a patient who refuses to talk to them. This clinical action typically is based on reports of the patient’s potential dangerousness from family, friends, or the police.

The diagnostic criteria for some personality disorders are based only on observed or reported behavior. They do not indicate a need for an interview. The diagnosis of a personality disorder cannot be made solely by interviewing an individual without knowledge of his or her behavior. Interviewing Bernie Madoff would not have revealed his sociopathic behavior.

The critical question may not be whether one could ethically make a psychiatric diagnosis of the President (I believe you can), but rather would it indicate or imply that he is dangerous? History informs us that the existence of a psychiatric disorder does not determine a politician’s fitness for office or if they are dangerous. Behavioral accounts of President Abraham Lincoln and his self-reports seem to confirm that at times he was depressed, but he clearly served our country with distinction.

Finally, it is not clear whether the Goldwater Rule is legal. It arguably interferes with a psychiatrist’s right of free speech without the risk of being accused of unethical behavior. I wonder what would happen if it were tested in court. Does the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protect a psychiatrist’s right to speak freely?

Sidney Weissman, MD

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science

Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern University

Chicago, Illinois

The current ‘political morass’

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah, for the wonderful synopsis of the current political morass in your editorial (From the Editor,

James Gallagher, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Des Moines, Iowa

Continue to: The biological etiology of compulsive sexual behavior

The biological etiology of compulsive sexual behavior

Dr. Grant’s article, “Compulsive sexual behavior: A nonjudgmental approach” (Evidence-Based Reviews,

Mukesh Sanghadia, MD, MRCPsych (UK), Diplomate ABPN

PsychiatristCommunity Research Foundation

San Diego, California

The author responds

Dr. Sanghadia highlights the lack of possible biological etiology of compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) in my article. This is a fair comment. The lack of agreed-upon diagnostic criteria, however, has resulted in a vast literature discussing sexual behaviors that may or may not be related to each other, and even suggest that what is currently referred to as CSB may in fact be quite heterogeneous. My article mentions the few neuroimaging and neurocognitive studies that address a more rigorously defined CSB. Other possible etiologies have been suggested for a range of out-of-control sexual behaviors, but have not been studied with a focus on this formal diagnostic category. For example, endocrine issues have been explored to some extent in individuals with paraphilic sexual behaviors (behaviors that appear to many to have no relationship to CSB as discussed in my article), and in those cases of paraphilic sexual behavior, a range of endocrine hormones have been examined—gonadotropin-releasing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, testosterone/dihydrotestosterone, and estrogen/progesterone. But these studies have yielded no conclusive outcomes in terms of findings or treatments.

In summary, the biology of CSB lags far behind that of other mental health disorders (and even other psychiatric disorders lack conclusive biological etiologies). Establishing this behavior as a legitimate diagnostic entity with agreed-upon criteria may be the first step in furthering our understanding of its possible biology.

Jon E. Grant, JD, MD, MPH

Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine

Chicago, Illinois

Continue to: A different view of patients with schizophrenia

A different view of patients with schizophrenia

After treating patients with schizophrenia for more than 30 years, I’ve observed a continuous flood of information about them. This overload has been consistent since my residency back in the 1980s. Theories ranging from the psychoanalytic to the biologic are numerous and valuable additions to our understanding of those who suffer with this malady, yet they provide no summation or overview with which to understand it.

For instance, we know that schizophrenia usually begins in the late teens or early twenties. We know that antidopaminergic medications usually help to varying degrees. Psychosocial interventions may contribute greatly to the ultimate outcome. Substance use invariably makes it worse. Establishing a connection with the patient can often be helpful. Medication compliance is crucial.

It is more or less accepted that there is deterioration of higher brain functions, hypofrontality, as well as so-called dysconnectivity of white matter. There is a genetic vulnerability, and there seems to be an excess of inflammation and changes in mitochondria. Most patients have low functioning, poor compensation, and a lack of social adeptness. However, some patients can recover quite nicely. Although most of us would agree that this is not dementia, we’d also concede that these patients’ cognitive functioning is not what it used to be. Electroconvulsive therapy also can sometimes be helpful.

So, how are we to view our patients with schizophrenia in a way that can be illuminating and give us a deeper sense of understanding this quizzical disorder? It has been helpful to me to regard these individuals as a people whose brain function has been usurped by a more primitive organization that is characterized by:

- a reduction in mental development, where patients function in a more childlike way with magical thinking and impaired reality-testing

- atrophy of higher brain structures, leading to hallucinatory experiences

- a hyper-dominergic state

- a usually gradual onset with some evidence of struggle between the old and new brain organizations

- impaired prepulse inhibition that’s likely secondary to diffuseness of thought

- eventual demise of higher brain structures with an inability to respond to anti-dopaminergics. (Antipsychotics can push the brain organization closer to the adult structure attained before the onset of the disease, at least initially.)

The list goes on. Thinking about patients with schizophrenia in this way allows me to appreciate what I feel is a more encompassing view of who they are and how they got there. I have some theories about where this more primitive organization may have originated, but whatever its origin, in a small percentage of people it is there, ready to assume control of their thinking just as they are reaching reproductive age. Early intervention and medication compliance may minimize damage.

If a theory helps us gain a greater understanding of our patients, then it’s worth considering. This proposition fits much of what we know about schizophrenia. Reading patients’ firsthand accounts of the illness helps confirm, in my opinion, this point of view.

Steven Lesk, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Fridley, Minnesota

Continue to: Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia

Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia

The authors of “Suspicious, sleepless, and smoking” (Cases That Test Your Skills,

During the past 15 years, I have routinely measured cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Some have no impairment, some have severe impairment, and some fall in between these extremes. Most often, impairment occurs in the area of executive function, which can lead to significant disability. Indeed, positive symptoms can clear up completely with treatment, but the deficits in executive functioning can remain.

I think it is fair to say that cognitive impairment is a common, although not nearly universal, feature of schizophrenia that sometimes improves with antipsychotic medication. I look forward to the advent of more clinicians paying attention to the issue of cognition in schizophrenia and, hopefully, better treatments for it.

John M. Mahoney, PhD

Shasta Psychiatric Hospital

Redding, California

The authors respond

We thank Dr. Mahoney for his thoughtful letter and queries into the case of Mr. F.

First, regarding the prevalence of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia, it is our opinion that cognitive impairment is a distinct, core, and nearly universal feature of schizophrenia. This also is the conclusion of many clinicians and researchers based on their significant work in the field; still, just as in our initial case study, we concede that these symptoms are not part of the DSM-5’s formal diagnostic criteria.

The core question Dr. Mahoney seems to pose is whether we contradicted ourselves. We assert that cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is not effectively treated with existing medications, and yet we described Mr. F’s cognitive improvement after he received risperidone, 2 mg/d, titrated up to 2 mg twice daily. We first pointed out that part of our treatment strategy was to target comorbid depression in this patient; nonetheless, Dr. Mahoney’s question remains valid, and we will attempt to answer.

Dr. Mahoney has observed that his patients with schizophrenia variably experience improved cognition, and notes that executive function is a particularly common lingering impairment. On this we wholly agree; this is a helpful point of clarification, and a useful distinction in light of the above question. Improvement in positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, as psychosis resolves, is a well-known and studied effect of antipsychotic therapy. As a result, the sensorium becomes more congruent with external reality, and one would expect the patient to display improved orientation. This then might be reasonably expected to produce mental status improvements; however, while some improvement is frequently observed, this is neither consistent nor complete improvement. In the case of Mr. F, we document improvement, but also significant continued impairment. Thus, we maintain that treating the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia with antipsychotics has been largely ineffective.

We do not see this as a slight distinction or an argument of minutiae. That patients frequently experience some degree of lingering impairment is a salient point. Neurocognitive impairment is a strong contributor to and predictor of disability in schizophrenia, and neurocognitive abilities most strongly predict functional outcomes. From a patient’s point of view, these symptoms have real-world consequences. Thus, we believe they should be evaluated and treated as aggressively and consistently as other schizophrenia symptoms.

In our case, we attempted to convey one primary message: Despite the challenges of treatment, there are viable options that should be pursued in the treatment of schizophrenia-related cognitive impairments. Nonpharmacologic modalities have shown encouraging results. Cognitive remediation therapy produces durable cognitive improvement—especially when combined with adjunctive therapies, such as small group therapy and vocational rehabilitation, and when comorbid conditions (major depressive disorder in Mr. F’s case) are treated.

In summary, we reiterate that cognitive impairments in schizophrenia represent a strong predictor of patient-oriented outcomes; we maintain our assertion regarding their inadequate treatment with existing medications; and we suggest that future trials attempt to find effective alternative strategies. We encourage psychiatric clinicians to approach treatment of this facet of pathology with an open mind, and to utilize alternative multi-modal therapies for the benefit of their patients with schizophrenia while waiting for new safe and effective pharmaceutical regimens.

Jarrett Dawson, MD

Family medicine resident

Department of Psychiatry

Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

Catalina Belean, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

In his editorial, “The toxic zeitgeist of hyper-partisanship: A psychiatric perspective” (From the Editor,

One’s political views do not inform us of his or her mental health status. This appreciation can be obtained only by a thorough psychological assessment. This is the basis of the Goldwater Rule, coupled with the ethical responsibility not to discuss patients’ private communications.

Today, this rule is tested by the behavior and actions of President Donald Trump. Proponents of the Goldwater Rule state that a psychiatrist cannot diagnose someone without performing a face-to-face diagnostic evaluation. This assumes psychiatrists diagnose patients only by interviewing them. However, any psychiatrist who has worked in an emergency room has signed involuntary commitment papers for a patient who refuses to talk to them. This clinical action typically is based on reports of the patient’s potential dangerousness from family, friends, or the police.

The diagnostic criteria for some personality disorders are based only on observed or reported behavior. They do not indicate a need for an interview. The diagnosis of a personality disorder cannot be made solely by interviewing an individual without knowledge of his or her behavior. Interviewing Bernie Madoff would not have revealed his sociopathic behavior.

The critical question may not be whether one could ethically make a psychiatric diagnosis of the President (I believe you can), but rather would it indicate or imply that he is dangerous? History informs us that the existence of a psychiatric disorder does not determine a politician’s fitness for office or if they are dangerous. Behavioral accounts of President Abraham Lincoln and his self-reports seem to confirm that at times he was depressed, but he clearly served our country with distinction.

Finally, it is not clear whether the Goldwater Rule is legal. It arguably interferes with a psychiatrist’s right of free speech without the risk of being accused of unethical behavior. I wonder what would happen if it were tested in court. Does the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protect a psychiatrist’s right to speak freely?

Sidney Weissman, MD

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science

Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern University

Chicago, Illinois

The current ‘political morass’

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah, for the wonderful synopsis of the current political morass in your editorial (From the Editor,

James Gallagher, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Des Moines, Iowa

Continue to: The biological etiology of compulsive sexual behavior

The biological etiology of compulsive sexual behavior

Dr. Grant’s article, “Compulsive sexual behavior: A nonjudgmental approach” (Evidence-Based Reviews,

Mukesh Sanghadia, MD, MRCPsych (UK), Diplomate ABPN

PsychiatristCommunity Research Foundation

San Diego, California

The author responds

Dr. Sanghadia highlights the lack of possible biological etiology of compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) in my article. This is a fair comment. The lack of agreed-upon diagnostic criteria, however, has resulted in a vast literature discussing sexual behaviors that may or may not be related to each other, and even suggest that what is currently referred to as CSB may in fact be quite heterogeneous. My article mentions the few neuroimaging and neurocognitive studies that address a more rigorously defined CSB. Other possible etiologies have been suggested for a range of out-of-control sexual behaviors, but have not been studied with a focus on this formal diagnostic category. For example, endocrine issues have been explored to some extent in individuals with paraphilic sexual behaviors (behaviors that appear to many to have no relationship to CSB as discussed in my article), and in those cases of paraphilic sexual behavior, a range of endocrine hormones have been examined—gonadotropin-releasing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, testosterone/dihydrotestosterone, and estrogen/progesterone. But these studies have yielded no conclusive outcomes in terms of findings or treatments.

In summary, the biology of CSB lags far behind that of other mental health disorders (and even other psychiatric disorders lack conclusive biological etiologies). Establishing this behavior as a legitimate diagnostic entity with agreed-upon criteria may be the first step in furthering our understanding of its possible biology.

Jon E. Grant, JD, MD, MPH

Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience

University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine

Chicago, Illinois

Continue to: A different view of patients with schizophrenia

A different view of patients with schizophrenia

After treating patients with schizophrenia for more than 30 years, I’ve observed a continuous flood of information about them. This overload has been consistent since my residency back in the 1980s. Theories ranging from the psychoanalytic to the biologic are numerous and valuable additions to our understanding of those who suffer with this malady, yet they provide no summation or overview with which to understand it.

For instance, we know that schizophrenia usually begins in the late teens or early twenties. We know that antidopaminergic medications usually help to varying degrees. Psychosocial interventions may contribute greatly to the ultimate outcome. Substance use invariably makes it worse. Establishing a connection with the patient can often be helpful. Medication compliance is crucial.

It is more or less accepted that there is deterioration of higher brain functions, hypofrontality, as well as so-called dysconnectivity of white matter. There is a genetic vulnerability, and there seems to be an excess of inflammation and changes in mitochondria. Most patients have low functioning, poor compensation, and a lack of social adeptness. However, some patients can recover quite nicely. Although most of us would agree that this is not dementia, we’d also concede that these patients’ cognitive functioning is not what it used to be. Electroconvulsive therapy also can sometimes be helpful.

So, how are we to view our patients with schizophrenia in a way that can be illuminating and give us a deeper sense of understanding this quizzical disorder? It has been helpful to me to regard these individuals as a people whose brain function has been usurped by a more primitive organization that is characterized by:

- a reduction in mental development, where patients function in a more childlike way with magical thinking and impaired reality-testing

- atrophy of higher brain structures, leading to hallucinatory experiences

- a hyper-dominergic state

- a usually gradual onset with some evidence of struggle between the old and new brain organizations

- impaired prepulse inhibition that’s likely secondary to diffuseness of thought

- eventual demise of higher brain structures with an inability to respond to anti-dopaminergics. (Antipsychotics can push the brain organization closer to the adult structure attained before the onset of the disease, at least initially.)

The list goes on. Thinking about patients with schizophrenia in this way allows me to appreciate what I feel is a more encompassing view of who they are and how they got there. I have some theories about where this more primitive organization may have originated, but whatever its origin, in a small percentage of people it is there, ready to assume control of their thinking just as they are reaching reproductive age. Early intervention and medication compliance may minimize damage.

If a theory helps us gain a greater understanding of our patients, then it’s worth considering. This proposition fits much of what we know about schizophrenia. Reading patients’ firsthand accounts of the illness helps confirm, in my opinion, this point of view.

Steven Lesk, MD

Private psychiatric practice

Fridley, Minnesota

Continue to: Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia

Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia

The authors of “Suspicious, sleepless, and smoking” (Cases That Test Your Skills,

During the past 15 years, I have routinely measured cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Some have no impairment, some have severe impairment, and some fall in between these extremes. Most often, impairment occurs in the area of executive function, which can lead to significant disability. Indeed, positive symptoms can clear up completely with treatment, but the deficits in executive functioning can remain.

I think it is fair to say that cognitive impairment is a common, although not nearly universal, feature of schizophrenia that sometimes improves with antipsychotic medication. I look forward to the advent of more clinicians paying attention to the issue of cognition in schizophrenia and, hopefully, better treatments for it.

John M. Mahoney, PhD

Shasta Psychiatric Hospital

Redding, California

The authors respond

We thank Dr. Mahoney for his thoughtful letter and queries into the case of Mr. F.

First, regarding the prevalence of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia, it is our opinion that cognitive impairment is a distinct, core, and nearly universal feature of schizophrenia. This also is the conclusion of many clinicians and researchers based on their significant work in the field; still, just as in our initial case study, we concede that these symptoms are not part of the DSM-5’s formal diagnostic criteria.

The core question Dr. Mahoney seems to pose is whether we contradicted ourselves. We assert that cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is not effectively treated with existing medications, and yet we described Mr. F’s cognitive improvement after he received risperidone, 2 mg/d, titrated up to 2 mg twice daily. We first pointed out that part of our treatment strategy was to target comorbid depression in this patient; nonetheless, Dr. Mahoney’s question remains valid, and we will attempt to answer.

Dr. Mahoney has observed that his patients with schizophrenia variably experience improved cognition, and notes that executive function is a particularly common lingering impairment. On this we wholly agree; this is a helpful point of clarification, and a useful distinction in light of the above question. Improvement in positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, as psychosis resolves, is a well-known and studied effect of antipsychotic therapy. As a result, the sensorium becomes more congruent with external reality, and one would expect the patient to display improved orientation. This then might be reasonably expected to produce mental status improvements; however, while some improvement is frequently observed, this is neither consistent nor complete improvement. In the case of Mr. F, we document improvement, but also significant continued impairment. Thus, we maintain that treating the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia with antipsychotics has been largely ineffective.

We do not see this as a slight distinction or an argument of minutiae. That patients frequently experience some degree of lingering impairment is a salient point. Neurocognitive impairment is a strong contributor to and predictor of disability in schizophrenia, and neurocognitive abilities most strongly predict functional outcomes. From a patient’s point of view, these symptoms have real-world consequences. Thus, we believe they should be evaluated and treated as aggressively and consistently as other schizophrenia symptoms.

In our case, we attempted to convey one primary message: Despite the challenges of treatment, there are viable options that should be pursued in the treatment of schizophrenia-related cognitive impairments. Nonpharmacologic modalities have shown encouraging results. Cognitive remediation therapy produces durable cognitive improvement—especially when combined with adjunctive therapies, such as small group therapy and vocational rehabilitation, and when comorbid conditions (major depressive disorder in Mr. F’s case) are treated.

In summary, we reiterate that cognitive impairments in schizophrenia represent a strong predictor of patient-oriented outcomes; we maintain our assertion regarding their inadequate treatment with existing medications; and we suggest that future trials attempt to find effective alternative strategies. We encourage psychiatric clinicians to approach treatment of this facet of pathology with an open mind, and to utilize alternative multi-modal therapies for the benefit of their patients with schizophrenia while waiting for new safe and effective pharmaceutical regimens.

Jarrett Dawson, MD

Family medicine resident

Department of Psychiatry

Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

Catalina Belean, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Saint Louis University

St. Louis, Missouri

Aggressive outbursts and emotional lability in a 16-year-old boy

Mr. X, age 16, has cerebral palsy (CP), idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH), and a history of impulse control disorder and behavioral instability, including episodes of aggression or combativeness. Mr. X’s mother reports that these episodes are almost always preceded by inappropriate laughing or crying. His outbursts and emotional lability have gotten worse during the last 6 months. Due to his disruptive behaviors, Mr. X has been unable to attend school, and his parents are considering group home placement. Although they were previously able to control their son’s aggressive behaviors, they fear for his safety, and after one such episode, they call 911. Mr. X is transported by police in handcuffs to the comprehensive psychiatric emergency room (CPEP) for evaluation.

While in CPEP, Mr. X remains uncooperative and disruptive; subsequently, he is placed in 4-point restraints and given

[polldaddy:9991896]

The authors’ observations

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) is a disorder characterized by sporadic episodes of inappropriate laughing and/or crying that are incongruent with situational context and are frequently exaggerated in comparison with the actual feelings of the patient. The duration of PBA episodes can last seconds to minutes and arise unpredictably.

PBA typically develops secondary to a neurologic disorder, most commonly Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease (PD), stroke, or traumatic brain injury (TBI).1 PBA symptoms are present in an estimated 29.3% of patients with AD, 44.8% of patients with ALS, 45.8% of patients with MS, 26% of patients with PD, 37.8% of patients with stroke, and 52.4% of patients with TBI.2 Although PBA appears far more frequently in patients with MS or ALS compared with those with PD, PD represents an under-recognized and larger patient population. A small fraction of patients also develops PBA secondary to hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, Graves’ disease, Wilson’s disease, brain tumors, and a multitude of encephalopathies.3 These neurologic disorders cause dysregulation of the corticopontine-cerebellar circuitry, resulting in functional impediment to the normal affect modulator action of the cerebellum.4

The neurologic insults that can result in PBA may include CP or iNPH. Cerebellar injury is a frequent pathological finding in CP.5 In patients with iNPH, in addition to altered CSF flow, enlarged ventricles compress the corticospinal tracts in the lateral ventricles,6 which is theorized to induce PBA symptoms.

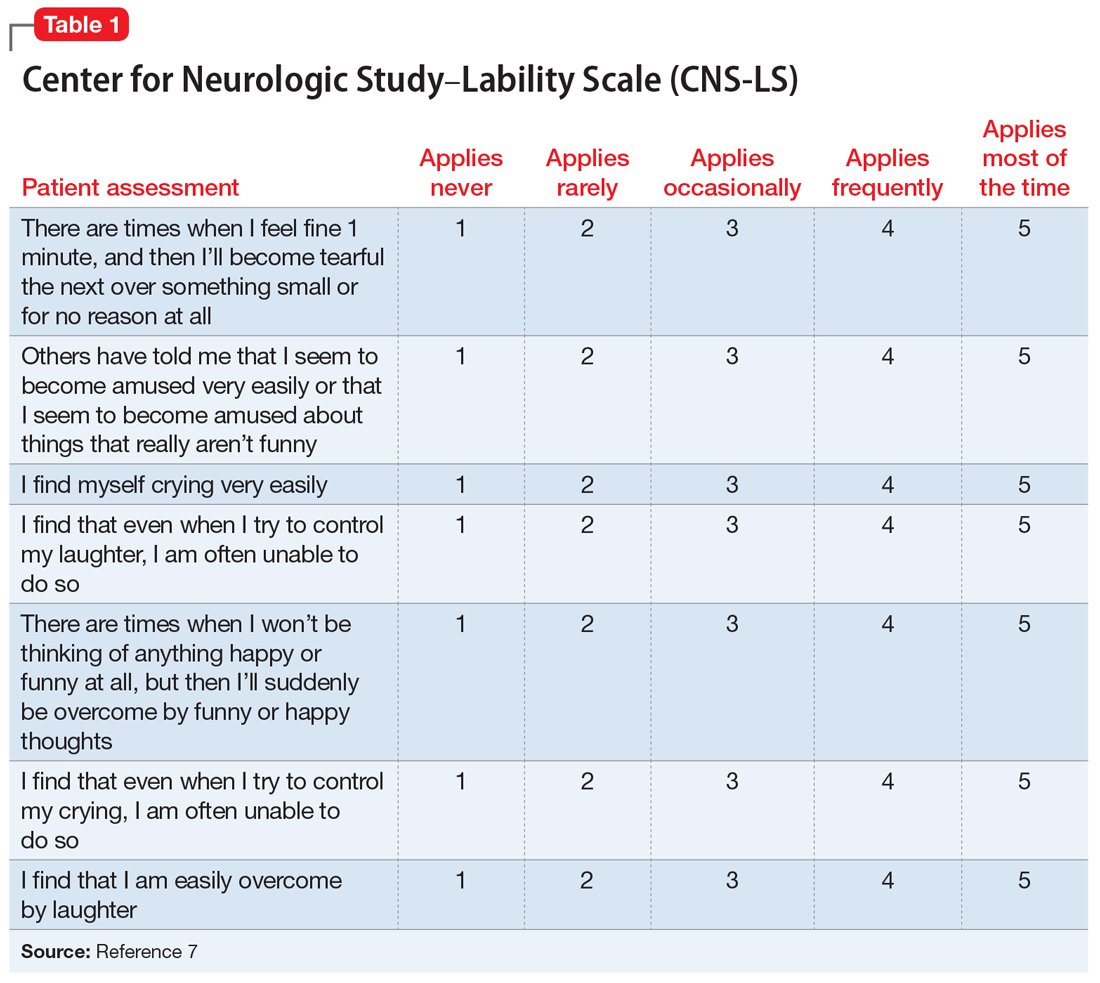

PBA is diagnosed by subjective clinical evaluation and by using the Center for Neurologic Study–Lability Scale (CNS-LS). The CNS-LS is a 7-question survey that addresses the severity of affect lability (Table 17). It may be completed by the patient or caregiver. Each question ranges in score from 1 to 5, with the total score ranging from 7 to 35. The minimum score required for the diagnosis of PBA is 13.7

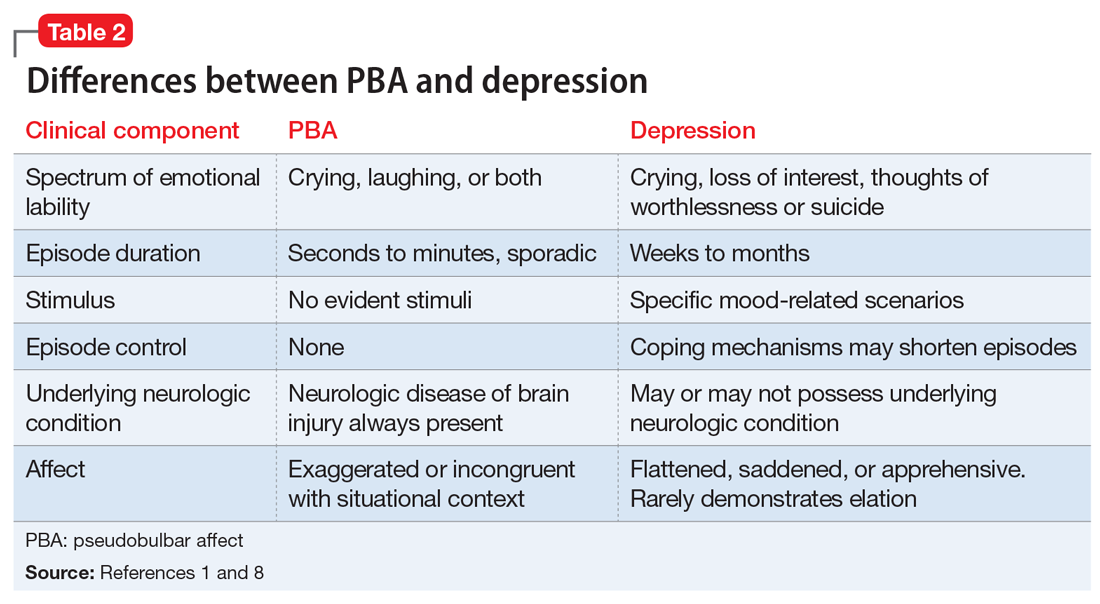

PBA is frequently misdiagnosed as depression, although the 2 disorders can occur simultaneously (Table 21,8). A crucial distinguishing factor between depression and PBA is the extent of symptoms. Depression presents as feelings of sadness associated with crying and disinterest that occur for weeks to months. In contrast, PBA presents as brief, uncontrollable episodes of laughing and/or crying that last seconds to minutes. Unlike depression, the behaviors associated with PBA are exaggerated or do not match the patient’s feelings. Furthermore, a neurologic disease or brain injury is always present in a patient with PBA, but is not imperative for the diagnosis of depression.

Continue to: Compared with individuals without PBA...

Compared with individuals without PBA, patients with PBA also experience more distress, embarrassment, and social disability, and are consequently more likely to suffer from other psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety/panic attacks, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, psychotic disorder, and schizophrenia.1 The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a tool for measuring depression severity, can be used in addition to the CNS-LS to determine if the patient has both depression and PBA.

HISTORY Poor response to anxiolytics and antipsychotics

Mr. X previously received a ventriculoperitoneal shunt for treating iNPH. He was not taking any medications for CP. To address his impulse control disorder, he was prescribed olanzapine, 20 mg/d, risperidone, 2 mg/d, and diazepam, 5 mg three times a day. Mr. X is uncontrolled on these medications, experiencing frequent behavioral outbursts at home. His mother completes a CNS-LS for him. He receives a score of 20, which suggests a diagnosis of PBA. His PHQ-9 score is 8, indicating mild depression.

[polldaddy:9991899]

TREATMENT Introducing a new medication

Mr. X is started on

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Decreasing the severity and frequency of episodes constitutes the mainstay of treating PBA. In the past, off-label treatments, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants, were prescribed to reduce PBA symptoms.5 Currently, dextromethorphan/quinidine is the only FDA-approved medication for treating PBA; however, its use in patients younger than age 18 is considered investigational.

Atypical antipsychotics, such as olanzapine and risperidone, have more warnings and precautions than dextromethorphan/quinidine. Risperidone has a “black-box” warning for QT prolongation, in addition to death and stroke in elderly patients.10 Although dextromethorphan/quinidine does not have a black-box warning, it does increase the risk of QT prolongation, and patients with cardiac risk factors should undergo an electrocardiogram before starting this medication. Additionally, risperidone and olanzapine are known to cause significant weight gain, which can increase the risk of developing hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.10,11 Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a potentially life-threatening adverse effect of all antipsychotics. NMS is characterized by fever, rigidity, altered consciousness, and increased heart and respiratory rates.12

Quinidine increases the bioavailability of dextromethorphan by inhibiting CYP2D6. When dextromethorphan/quinidine is simultaneously used with an SSRI that also inhibits CYP2D6, such as paroxetine or fluoxetine, the patient may be at increased risk for developing adverse effects such as respiratory depression and serotonin syndrome.13

[polldaddy:9991902]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Although the exact pathophysiology of PBA is unknown, multiple theories may explain the principle elements of the condition. In the absence of a neurologic insult, the cerebellum acts as an affect regulator, inhibiting laughter and crying at times in which they are considered inappropriate. Parvizi et al4 have theorized that the lesions involved in PBA disrupt the corticopontine-cerebellar circuitry, which impedes the ability of the cerebellum to function as an affect modulator.3 In addition to the dysregulation of cerebellar circuitry, altered serotonin and glutamate levels are believed to contribute to the deficient affect regulation observed in PBA; therefore, adding dextromethorphan/quinidine potentiates serotonin and glutamate levels in the synaptic cleft, resulting in a reduction in PBA episodes.4

OUTCOME Affect stability

Seven months after beginning dextromethorphan/quinidine, Mr. X has experienced resolution of his PBA episodes. His PHQ-9 score was reduced to 0 (no clinical signs of depression) within 1 month of starting this medication and his PHQ-9 scores remain below 5, representing minimal depressive severity. The CNS-LS scale is not conducted at further visits because the patient’s mother reported no further PBA episodes. Mr. X no longer exhibits episodes of aggression. These episodes seemed to have been a manifestation of his frustration and difficulty in controlling his PBA episodes. Furthermore, his dosage of diazepam was reduced, and he was weaned off risperidone. Mr. X’s parents report that he has a drastically improved affect. He continues to tolerate his medication well and no longer demonstrates any exacerbations of his psychiatric symptoms.

Bottom Line

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) may occur secondary to various neurologic insults, including cerebral palsy and idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. The condition is diagnosed by a subjective clinical evaluation and use of the Center for Neurologic Study–Lability Scale. Dextromethorphan/quinidine can significantly reduce PBA symptoms.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anthony S. Graziano and Rachel M. Watt, both Physician Assistant students, Daemen College, Amherst, New York.

Related Resources

- Frock B, Williams A, Caplan JP. Pseudobulbar affect: when patients laugh or cry, but don’t know why. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(9):56-60,63.

- Crumpacker DW. Enhancing approaches to the identification and management of pseudobulbar affect. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(9):e1155.

Drug Brand Names

Dextromethorphan/quinidine • Nuedexta

Diazepam • Valium

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paroxetine • Paxil

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Colamonico J, Formella A, Bradley W. Pseudobulbar affect: burden of illness in the USA. Adv Ther. 2012;29(9):775-798.

2. Brooks BR, Crumpacker D, Fellus J, et al. PRISM: a novel research tool to assess the prevalence of pseudobulbar affect symptoms across neurological conditions. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072232.

3. Schiffer R, Pope LE. Review of pseudobulbar affect including a novel and potential therapy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(4):447-454.

4. Parvizi J, Anderson SW, Martin CO, et al. Pathological laughter and crying: a link to the cerebellum. Brain. 2001;124(pt 9):1708-1719.

5. Johnsen SD, Bodensteiner JB, Lotze TE. Frequency and nature of cerebellar injury in the extremely premature survivor with cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol. 2005;20(1):60-64.

6. Kamiya K, Hori M, Miyajima M, et al. Axon diameter and intra-axonal volume fraction of the corticospinal tract in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus measured by Q-Space imaging. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103842.

7. Moore SR, Gresham LS, Bromberg MB, et al. A self report measuredextromethorphan of affective lability. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;63(1):89-93.

8. Ahmed A, Simmons Z. Pseudobulbar affect: prevalence and management. Ther Clinical Risk Manag. 2013;9:483-489.

9. Cruz MP. Nuedexta for the treatment of pseudobulbar affect. A condition of involuntary crying or laughing. P T. 2013;38(6):325-328.

10. Goëb JL, Marco S, Duhamel A, et al. Metabolic side effects of risperidone in children and adolescents with early onset schizophrenia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(6):486-487.

11. Nemeroff CB. Dosing the antipsychotic medication olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(suppl 10):45-49.

12. Troller JN, Chen X, Sachdev PS. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with atypical antipsychotic drugs. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(6):477-492.

13. Schoedel KA, Pope LE, Sellers EM. Randomized open-label drug-drug interaction trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine and paroxetine in healthy volunteers. Clin Drug Investig. 2012;32(3):157-169.

Mr. X, age 16, has cerebral palsy (CP), idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH), and a history of impulse control disorder and behavioral instability, including episodes of aggression or combativeness. Mr. X’s mother reports that these episodes are almost always preceded by inappropriate laughing or crying. His outbursts and emotional lability have gotten worse during the last 6 months. Due to his disruptive behaviors, Mr. X has been unable to attend school, and his parents are considering group home placement. Although they were previously able to control their son’s aggressive behaviors, they fear for his safety, and after one such episode, they call 911. Mr. X is transported by police in handcuffs to the comprehensive psychiatric emergency room (CPEP) for evaluation.

While in CPEP, Mr. X remains uncooperative and disruptive; subsequently, he is placed in 4-point restraints and given

[polldaddy:9991896]

The authors’ observations

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) is a disorder characterized by sporadic episodes of inappropriate laughing and/or crying that are incongruent with situational context and are frequently exaggerated in comparison with the actual feelings of the patient. The duration of PBA episodes can last seconds to minutes and arise unpredictably.

PBA typically develops secondary to a neurologic disorder, most commonly Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease (PD), stroke, or traumatic brain injury (TBI).1 PBA symptoms are present in an estimated 29.3% of patients with AD, 44.8% of patients with ALS, 45.8% of patients with MS, 26% of patients with PD, 37.8% of patients with stroke, and 52.4% of patients with TBI.2 Although PBA appears far more frequently in patients with MS or ALS compared with those with PD, PD represents an under-recognized and larger patient population. A small fraction of patients also develops PBA secondary to hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, Graves’ disease, Wilson’s disease, brain tumors, and a multitude of encephalopathies.3 These neurologic disorders cause dysregulation of the corticopontine-cerebellar circuitry, resulting in functional impediment to the normal affect modulator action of the cerebellum.4

The neurologic insults that can result in PBA may include CP or iNPH. Cerebellar injury is a frequent pathological finding in CP.5 In patients with iNPH, in addition to altered CSF flow, enlarged ventricles compress the corticospinal tracts in the lateral ventricles,6 which is theorized to induce PBA symptoms.

PBA is diagnosed by subjective clinical evaluation and by using the Center for Neurologic Study–Lability Scale (CNS-LS). The CNS-LS is a 7-question survey that addresses the severity of affect lability (Table 17). It may be completed by the patient or caregiver. Each question ranges in score from 1 to 5, with the total score ranging from 7 to 35. The minimum score required for the diagnosis of PBA is 13.7

PBA is frequently misdiagnosed as depression, although the 2 disorders can occur simultaneously (Table 21,8). A crucial distinguishing factor between depression and PBA is the extent of symptoms. Depression presents as feelings of sadness associated with crying and disinterest that occur for weeks to months. In contrast, PBA presents as brief, uncontrollable episodes of laughing and/or crying that last seconds to minutes. Unlike depression, the behaviors associated with PBA are exaggerated or do not match the patient’s feelings. Furthermore, a neurologic disease or brain injury is always present in a patient with PBA, but is not imperative for the diagnosis of depression.

Continue to: Compared with individuals without PBA...

Compared with individuals without PBA, patients with PBA also experience more distress, embarrassment, and social disability, and are consequently more likely to suffer from other psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety/panic attacks, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, psychotic disorder, and schizophrenia.1 The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a tool for measuring depression severity, can be used in addition to the CNS-LS to determine if the patient has both depression and PBA.

HISTORY Poor response to anxiolytics and antipsychotics

Mr. X previously received a ventriculoperitoneal shunt for treating iNPH. He was not taking any medications for CP. To address his impulse control disorder, he was prescribed olanzapine, 20 mg/d, risperidone, 2 mg/d, and diazepam, 5 mg three times a day. Mr. X is uncontrolled on these medications, experiencing frequent behavioral outbursts at home. His mother completes a CNS-LS for him. He receives a score of 20, which suggests a diagnosis of PBA. His PHQ-9 score is 8, indicating mild depression.

[polldaddy:9991899]

TREATMENT Introducing a new medication

Mr. X is started on

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Decreasing the severity and frequency of episodes constitutes the mainstay of treating PBA. In the past, off-label treatments, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants, were prescribed to reduce PBA symptoms.5 Currently, dextromethorphan/quinidine is the only FDA-approved medication for treating PBA; however, its use in patients younger than age 18 is considered investigational.

Atypical antipsychotics, such as olanzapine and risperidone, have more warnings and precautions than dextromethorphan/quinidine. Risperidone has a “black-box” warning for QT prolongation, in addition to death and stroke in elderly patients.10 Although dextromethorphan/quinidine does not have a black-box warning, it does increase the risk of QT prolongation, and patients with cardiac risk factors should undergo an electrocardiogram before starting this medication. Additionally, risperidone and olanzapine are known to cause significant weight gain, which can increase the risk of developing hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.10,11 Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a potentially life-threatening adverse effect of all antipsychotics. NMS is characterized by fever, rigidity, altered consciousness, and increased heart and respiratory rates.12

Quinidine increases the bioavailability of dextromethorphan by inhibiting CYP2D6. When dextromethorphan/quinidine is simultaneously used with an SSRI that also inhibits CYP2D6, such as paroxetine or fluoxetine, the patient may be at increased risk for developing adverse effects such as respiratory depression and serotonin syndrome.13

[polldaddy:9991902]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Although the exact pathophysiology of PBA is unknown, multiple theories may explain the principle elements of the condition. In the absence of a neurologic insult, the cerebellum acts as an affect regulator, inhibiting laughter and crying at times in which they are considered inappropriate. Parvizi et al4 have theorized that the lesions involved in PBA disrupt the corticopontine-cerebellar circuitry, which impedes the ability of the cerebellum to function as an affect modulator.3 In addition to the dysregulation of cerebellar circuitry, altered serotonin and glutamate levels are believed to contribute to the deficient affect regulation observed in PBA; therefore, adding dextromethorphan/quinidine potentiates serotonin and glutamate levels in the synaptic cleft, resulting in a reduction in PBA episodes.4

OUTCOME Affect stability

Seven months after beginning dextromethorphan/quinidine, Mr. X has experienced resolution of his PBA episodes. His PHQ-9 score was reduced to 0 (no clinical signs of depression) within 1 month of starting this medication and his PHQ-9 scores remain below 5, representing minimal depressive severity. The CNS-LS scale is not conducted at further visits because the patient’s mother reported no further PBA episodes. Mr. X no longer exhibits episodes of aggression. These episodes seemed to have been a manifestation of his frustration and difficulty in controlling his PBA episodes. Furthermore, his dosage of diazepam was reduced, and he was weaned off risperidone. Mr. X’s parents report that he has a drastically improved affect. He continues to tolerate his medication well and no longer demonstrates any exacerbations of his psychiatric symptoms.

Bottom Line

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) may occur secondary to various neurologic insults, including cerebral palsy and idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. The condition is diagnosed by a subjective clinical evaluation and use of the Center for Neurologic Study–Lability Scale. Dextromethorphan/quinidine can significantly reduce PBA symptoms.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anthony S. Graziano and Rachel M. Watt, both Physician Assistant students, Daemen College, Amherst, New York.

Related Resources

- Frock B, Williams A, Caplan JP. Pseudobulbar affect: when patients laugh or cry, but don’t know why. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(9):56-60,63.

- Crumpacker DW. Enhancing approaches to the identification and management of pseudobulbar affect. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(9):e1155.

Drug Brand Names

Dextromethorphan/quinidine • Nuedexta

Diazepam • Valium

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lorazepam • Ativan

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paroxetine • Paxil

Risperidone • Risperdal

Mr. X, age 16, has cerebral palsy (CP), idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH), and a history of impulse control disorder and behavioral instability, including episodes of aggression or combativeness. Mr. X’s mother reports that these episodes are almost always preceded by inappropriate laughing or crying. His outbursts and emotional lability have gotten worse during the last 6 months. Due to his disruptive behaviors, Mr. X has been unable to attend school, and his parents are considering group home placement. Although they were previously able to control their son’s aggressive behaviors, they fear for his safety, and after one such episode, they call 911. Mr. X is transported by police in handcuffs to the comprehensive psychiatric emergency room (CPEP) for evaluation.

While in CPEP, Mr. X remains uncooperative and disruptive; subsequently, he is placed in 4-point restraints and given

[polldaddy:9991896]

The authors’ observations

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) is a disorder characterized by sporadic episodes of inappropriate laughing and/or crying that are incongruent with situational context and are frequently exaggerated in comparison with the actual feelings of the patient. The duration of PBA episodes can last seconds to minutes and arise unpredictably.

PBA typically develops secondary to a neurologic disorder, most commonly Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS), Parkinson’s disease (PD), stroke, or traumatic brain injury (TBI).1 PBA symptoms are present in an estimated 29.3% of patients with AD, 44.8% of patients with ALS, 45.8% of patients with MS, 26% of patients with PD, 37.8% of patients with stroke, and 52.4% of patients with TBI.2 Although PBA appears far more frequently in patients with MS or ALS compared with those with PD, PD represents an under-recognized and larger patient population. A small fraction of patients also develops PBA secondary to hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, Graves’ disease, Wilson’s disease, brain tumors, and a multitude of encephalopathies.3 These neurologic disorders cause dysregulation of the corticopontine-cerebellar circuitry, resulting in functional impediment to the normal affect modulator action of the cerebellum.4

The neurologic insults that can result in PBA may include CP or iNPH. Cerebellar injury is a frequent pathological finding in CP.5 In patients with iNPH, in addition to altered CSF flow, enlarged ventricles compress the corticospinal tracts in the lateral ventricles,6 which is theorized to induce PBA symptoms.

PBA is diagnosed by subjective clinical evaluation and by using the Center for Neurologic Study–Lability Scale (CNS-LS). The CNS-LS is a 7-question survey that addresses the severity of affect lability (Table 17). It may be completed by the patient or caregiver. Each question ranges in score from 1 to 5, with the total score ranging from 7 to 35. The minimum score required for the diagnosis of PBA is 13.7