User login

February 2018

Gastroenterology:

Living like an academic athlete: How to improve clinical and academic productivity as a gastroenterologist. Benchimol E et al.

2018 Jan;154(1):8-14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.017.

“Spending your life wisely”: How to create an asset management plan. Adams MA et al.

2017 Dec;153(6):1469-72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.032.

How to balance clinical work and research in the current era of academic medicine. Katzka DA.

2017 Nov;153(5):1177-80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.09.024.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.:

New models of gastroenterology practice. Allen JI et al.

2018 Jan;16(1):3-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.003.

Cracking the clinician educator code in gastroenterology. Shapiro JM et al.

2017 Dec;15(12):1828-32. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.040.

Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.:

Setting up a lab: The early years. Habtezion A.

2017 Nov; 4(3): 445-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.08.003.

Gastroenterology:

Living like an academic athlete: How to improve clinical and academic productivity as a gastroenterologist. Benchimol E et al.

2018 Jan;154(1):8-14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.017.

“Spending your life wisely”: How to create an asset management plan. Adams MA et al.

2017 Dec;153(6):1469-72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.032.

How to balance clinical work and research in the current era of academic medicine. Katzka DA.

2017 Nov;153(5):1177-80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.09.024.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.:

New models of gastroenterology practice. Allen JI et al.

2018 Jan;16(1):3-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.003.

Cracking the clinician educator code in gastroenterology. Shapiro JM et al.

2017 Dec;15(12):1828-32. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.040.

Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.:

Setting up a lab: The early years. Habtezion A.

2017 Nov; 4(3): 445-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.08.003.

Gastroenterology:

Living like an academic athlete: How to improve clinical and academic productivity as a gastroenterologist. Benchimol E et al.

2018 Jan;154(1):8-14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.017.

“Spending your life wisely”: How to create an asset management plan. Adams MA et al.

2017 Dec;153(6):1469-72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.10.032.

How to balance clinical work and research in the current era of academic medicine. Katzka DA.

2017 Nov;153(5):1177-80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.09.024.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.:

New models of gastroenterology practice. Allen JI et al.

2018 Jan;16(1):3-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.10.003.

Cracking the clinician educator code in gastroenterology. Shapiro JM et al.

2017 Dec;15(12):1828-32. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.040.

Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol.:

Setting up a lab: The early years. Habtezion A.

2017 Nov; 4(3): 445-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.08.003.

Impact of Drug Shortages on Patient Safety and Pharmacy Operation Costs

Drug product shortages threaten health care quality and public health by creating barriers to optimal care. The frequency of drug shortages has risen dramatically since 2005 and now influences broad areas of health care practice. More than 400 generic drug products have been affected, forcing institutions to purchase costly brand-name products, substitute alternative therapies, or procure from gray market vendors at increased institutional costs.1 Scarcity and cost have potential to negatively impact patient outcomes and the ability of health care organizations to respond to the needs of their patients.

Background

Although constantly fluctuating, the number of active shortages reached a height of 320 products at the end the third quarter of 2014.2 A 2011 analysis from Premier Healthcare Alliance estimated the added cost of purchasing brand, generic, or alternative drugs due to shortage may have inflated hospital costs by $200 million annually.1 In 2016, the number of active shortages dropped to 176, suggesting a downward trend. However, the drug supply chain remains a concern for pharmacies in the U.S.

Despite creative approaches to shortage management, the variable characteristics of shortages make planning difficult. For example, the drug product in short supply may or may not have an alternative for use in similar clinical scenarios. The impact of shortages of medications lacking an equivalent alternative product has been documented, such as the past shortage of succinylcholine for anesthesia, resulting in surgery cancellations when an alternative paralytic agent was not appropriate.3 In 2016, the Cleveland Clinic reported undertaking “military-style triage” in determining patients who required use of aminocaproic acid during open heart surgery due to its limited supply.4 Decisions to reserve drug supply for emergency use and prefilling syringes under pharmacy supervision to extend stability and shelf life are short-term solutions to larger, systemic issues. Unfortunately, these scenarios have the potential to disrupt patient care and diminish health outcomes.

Shortages of products that have an available therapeutic substitution may seem easily manageable, but additional considerations may be present. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is considered the drug of choice for bladder cancer. In 2011, there was a shortage of the BCG vaccine after mold was discovered in the formulation.5 Providers were forced to choose between reducing or reallocating the dose of BCG, turning away patient, or substituting mitomycin C, which is less effective and costlier. When tamsulosin capsules became difficult to obtain in 2014, some institutions began switching patients to alfuzosin.6 Although alfuzosin is similar in mechanism to tamsulosin, it may prolong the QTc interval. Not only did this substitution present a contraindication for patients with elevated QTc intervals or who were already receiving concomitant medications that prolonged the QTc interval, but also it required additional cost and resources needed to update electrocardiograms.

VA Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacies

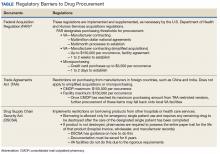

The VHA serves nearly 9 million patients at more than 1,200 facilities across the U.S.7 This large patient population results in an estimated 149 million outpatient prescriptions annually.8 About 80% of these are distributed by mail through 7 VA consolidated mail outpatient pharmacies (CMOPs). When drug scarcity impedes the ability of the CMOP to respond to medication demand, the local facility must fill these prescriptions. These rejections sent back to the facility impact workload, patient wait times, and access to medication therapy. Barriers to medication procurement in the VA also stem from regulations based on legislation, including the Trade Agreements Act, Drug Supply Chain Security Act, and the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) (Table).

The impact of drug shortages has been described previously in the private sector, particularly for emergency medicine and chemotherapy.9,10 However, the impact of drug shortages on health care provision to veteran populations within the VA has not previously been analyzed. Due to the unique procurement regulations that influence the VA and the importance of continuing to provide optimal health care services to veterans, assessing the impact of drug shortages on patient safety and health care costs is necessary in informing policy decisions and guiding recommendations for mitigation strategies. The purpose of this study was to assess the influence of drug shortages on institutional costs and patient care within VA facilities and formulate recommendations for enhanced mitigation of this issue.

Methods

The primary outcome of this study was to characterize the impact of drug shortages on institutional cost and patient safety events among VHA facilities. Secondary outcomes included subgroup evaluation in reported drug shortage impact among 1a, 1b, and 1c complexity VA facility survey respondents and assessment of drug shortage impact on CMOP prescription order fulfillment and operation cost.

Definitions

The complexity ranking system is a facility grouping method used within the VA to characterize the level of service provision, teaching and research opportunities, patient volume, intensive care unit level, and other factors offered by a VA site. Rankings start from 1 (highest level of services offered) to 3 (lowest level of services offered), with level 1 facilities further divided into a, b, and c subdivisions. A level 1a facility will be larger with more services offered than a 1b, which is larger and offers more services than a 1c facility. The VA facilities are further characterized by regional distribution. Sites are grouped under VISNs of which there are currently 21.

The CMOP program was responsible for dispensing about 119 million outpatient prescriptions in 2016 and includes designated sites for the dispensing of controlled substances and supply items. The VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) oversees formulary management, plans national drug policy, promotes safe and appropriate drug therapy, and delivers high-quality and sustainable pharmacy benefits for veterans.

Study Design

A descriptive study was initiated to characterize the impact of drug shortages among VA facilities. An analysis of administrative medication safety event reporting and institutional costs data at the Denver VAMC in Colorado was done, focusing on predetermined drug products involved in a recent shortage. The analysis was accomplished through a review of the VA adverse drug events reporting system (VA ADERS) reports and a local medication errors quality improvement database and paper procurement records, respectively. Concurrently, a survey was disseminated among qualifying VA facilities across the country that sought to characterize the impact of drug shortages nationally.

Sample Selection

Denver VAMC. The Denver VAMC, where the authors were located, was selected as the local sample site. The intention was to compare the strategies used locally with strategies used among similar (level 1a, 1b, and 1c) facilities. Preselected “cost-impacting” drug products were identified through a review of historic shortages with a significant local impact. These drugs were defined as low cost/high utilization (eg, tamsulosin 0.4-mg capsules and ketorolac solution), medium cost/utilization (eg, piperacillin/tazobactam IV solutions and aminocaproic acid solution), and high cost/low utilization (eg, nitroprusside IV solution and BCG vaccine solution). Additionally, patient safety event data reported internally for quality improvement and locally via VA ADERS were reviewed for preselected “safety impact” drug products and included BCG vaccine, tamsulosin capsules, IV fluid products, calcium gluconate and chloride injections, and aminocaproic acid injection.

National Survey. The authors identified 84 level 1 complexity facilities and used the PBM pharmacy directory to contact the administrative personnel representing each facility. These representatives identified a point of contact to aid in survey completion. A separate survey also was sent to the CMOP facilities (survey outlines available at www.fedprac.com).

Data Collection

Denver VAMC. Financial data were sampled through a manual review of paper procurement records stored by date in the inpatient pharmacy of the Denver VAMC. Variables included units of product used over the period of drug shortage, cost per unit during shortage, and cost per unit before shortage. This information also was supplemented with data from the prescription processing software’s drug file. Patient safety data were gathered through query of the identified event reporting databases for the prespecified drug on shortage. These variables included the type of error and the effect the error had on the patient.

National Survey. Data collection focused on notable drug shortages and patient safety reporting between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2016. The survey was maintained in a facility-specific spreadsheet. Editing capabilities were disabled for all actions other than responding to questions. Recipients were followed up with a courtesy e-mail after 2 weeks and another 2 times unless a survey was received. Data were de-identified and aggregated for analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) descriptive statistics were used to relay information from this assessment. Extrapolations from procurement cost data and drug product utilization were used to estimate the enhanced direct cost associated with identified drug shortages. Similar extrapolations were used to estimate the cost associated with shortages leading to CMOP rejection and local fill.

Results

Survey completion totaled 20% of invited facilities (n = 17). Good geographic and VISN distribution was noted with representatives from VISNs 2, 4, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 16, 21, and 22. VISNs 10 and 12 provided the most representation with 3 participants, each. Level 1a facilities participated most (n = 9), followed by 1b (n = 6) and 1c (n = 2). Participating facilities reported a mean (SD) of 54 (21.5) pharmacists and 34 (15.3) pharmacy technician staff members employed. The most common reason for not participating was lack of personnel resources and competing demands. The CMOP participation was 100% (n = 7) and completed through a coordinated response.

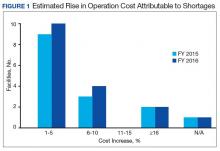

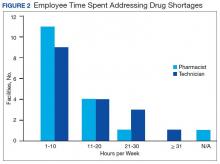

Results of the budgetary increase and staff member time allocation survey assessments are provided (Figures 1 and 2). Five facilities provided an annual estimate of increased cost due to acquisition of drugs on shortage through open market purchases that ranged from about $150,000 to $750,000. Nearly half of the surveyed facilities endorsed having a drug shortage task force (n = 8) to respond to drug shortages and mitigate their impact.

Regarding drug product allocation, only 2 facilities did not have current restrictions for use due to a shortage. Many had between 1 and 10 of these restrictions implemented to conserve supply (n = 11, 64%), 2 facilities reported 11 to 20 restrictions, and 2 facilities noted more than 30 restrictions. Similarly, 3 facilities had not needed to revise any current treatment protocols due to drug shortages. The majority of facilities had revised 1 to 5 current protocols (n = 12, 70%), 1 revised 6 to 10 protocols, and 1 facility revised more than 10 protocols.

In assessing patient safety concerns, 1 facility identified a history of transferring patients to alternative medical sites for the patients to obtain necessary medication impacted by a local shortage. Additionally, during the BCG vaccine shortage, 6 facilities (35.3%) substituted mitomycin C for the treatment of urinary bladder cancer.

Most participants either agreed (n = 8, 47.0%) or strongly agreed (n = 4, 23.5%) that modifications to FAR to increase purchasing opportunities from foreign distributors during drug shortage would help mitigate the impact of such shortages. Similarly, most participants agreed (n = 10, 58.8%) or strongly agreed (n = 3, 17.6%) that PBM guidance on drug shortage management would help efficiently and effectively respond to issues that might arise. The consensus of participants also agreed (n = 13, 76.5%) that organized collaborations or working groups within each VISN might help assist in drug shortage management.

The CMOP facility data revealed that 2 sites did not require dedicated staffing to respond to shortages, and 3 sites had not experienced cost increases because of shortages. Pharmacist use varied between sites, with 2 facilities using 1 to 10 pharmacist h/wk, and 1 facility using 11 to 20 pharmacist h/wk, and 1 facility using 21 to 30 pharmacist h/wk. Technician utilization was more pronounced, with 2 facilities using more than 30 technician h/wk, and 2 facilities using 1 to 10 technician h/wk. Workload and costs may have been influenced in other ways as 3 sites endorsed using overtime pay, shifting product responsibility between CMOPs, prolonging patient wait times, and close monitoring for each. In fiscal year 2015, some sites experienced a 1% to 5% (n = 2) and 6% to 10% (n = 1) increase in operation cost attributable to shortage. Results from fiscal year 2016 showed that some sites continued to see a 1% to 5% (n = 1) and 6% to 10% (n = 2) increase in operation cost attributable to shortage.

Through aggregation of CMOP responses on the number of prescriptions sent back to local facility for fill due to back order, a downward trend in the total number of rejections was seen over the 2.5 fiscal years assessed. This amounted to more than 1 million rejections in fiscal year 2015, about 788,000 rejections in 2016, and about 318,000 rejections through the first 2 quarters of 2017.

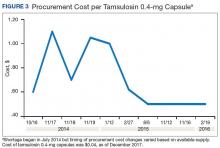

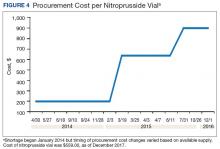

A consistent rise in the medication procurement budget requirement was characterized within the single VA facility review. The quarterly median increase was 2.7% over 2.5 years (min: -1.4%; max: 6.6%) for total outpatient medication costs, excluding hepatitis C antiviral therapies. Procurement cost records were insufficient to characterize historic expenditures for 4 of the prespecified drug products. The data collected on tamsulosin capsule and nitroprusside vial procurement during shortage is provided (Figures 3 and 4). Over the time frame of procurement records found on review, the added costs of nitroprusside vials and tamsulosin capsules were $22,766.09 (+167.9% of base cost) and $17,433.70 (+657.3% of base cost), respectively. No patient safety data were found on review.

Discussion

Drug product shortages represent a barrier to quality and efficiency across health care institutions. A survey of health system pharmacies in the southeastern U.S. found that the majority of respondents tracking shortage data reported a 300% to 500% markup by alternative or gray market suppliers for hard-to-find medications.11 These reports are similar to the authors’ analyses of the trends in increased procurement expenditures documented during the tamsulosin capsule and nitroprusside vial shortages and indirectly correlate with the survey results indicating that most facilities endorsed a trend in operation cost increase attributable to drugs product shortage. The estimated annual costs for open market purchases further informs the financial burden aggregated by this issue.

Indirect costs from drug shortage further complicated quantifying the impact of shortages. Many facilities acknowledged the indirect influence drug shortages have on staffing and workload due to the implementation of mitigation strategies. Most participants found it necessary to establish restrictions for use in addition to altering protocols. These required the time investment of essential personnel from development through execution and education. Situations also can arise for mass therapeutic substitution. In this example, pharmacy staff may be required to oversee medication transition from the product on shortage to an appropriate alternative. When substitution involves hundreds or thousands of outpatient prescriptions, such as the tamsulosin shortage, the process may be tedious and time consuming, depending on the level of clinical decision making needed to determine patient candidacy for transitioning products.

Improving institutional cost efficiency becomes a significant challenge with persistent drug shortages. Professional advocacy groups, such as the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), help provide guidance to organizations constrained by specific drug shortages.12 Staff knowledgeable in allocation, supply considerations, and product repackaging and stability data also are essential. Other mitigation strategies include automatic substitutions, restrictions for use or inventory control strategies, and open market procurement, or borrowing from other institutions.

Data gathered from the survey of CMOP facilities also helped elucidate strategies used to mitigate drug shortage impacts for those respondents impacted by shortage. Likely, the 2 CMOP facilities without dedicated staff focused on shortages are those whose outpatient prescription fulfillment responsibility were focused on supply items or controlled substances. The impacted CMOP respondents cited overtime pay, shifting product responsibility, and prolonging patient wait times as the most frequently employed mitigation strategies. When these and other strategies fail to manage a shortage, prescriptions are often sent back to the local facility to be filled. Unfortunately for these facilities, the same mitigation strategies used by CMOP are not always feasible. Overtime pay may not be possible given staffing and budgetary resources, sending prescriptions back to facilities in itself prolongs patient wait times, and local medical centers do not have the option of shifting product responsibility between sites or sending the prescription to another facility. Herein lies 1 rationale for the CMOP effort to reduce the volume of prescriptions sent back to local medical centers.

Multiple offices within the FDA have roles in the mitigation of national drug shortages within their regulatory purview. Much of the recent focus stems from provisions enacted under Title X of the FDA Safety and Innovation Act of 2012, which addresses problems in the drug-supply chain.12 Rectifying a shortage involves short- and long-term strategic planning to address supply, distribution, and market reaction to need. Collaboration between the FDA and manufacturers is one method by which demand can be satisfied through the coordination of resources, expedition of inspections, and root cause analysis of the shortage.

Similar collaborations within the VA were viewed favorably by respondents and might yield productive relationships if regional or VISN working groups were to be established. Alternative long-term strategies are executed through regulation, particularly concerning the importation of foreign manufactured drugs and regulatory discretion on supplier vetting. Despite a strong respondent consensus that regulatory modifications of foreign product importation in the setting of a drug shortage may be beneficial, such a change would require a congressional action and is not likely to be timely. Unfortunately, gray market pharmaceutical distribution, driven by wholesaler stockpiling to raise prices, is separate from manufacturer driven shortages and falls outside the FDA’s regulatory purview and institutional mitigation strategies.

Although based on this limited survey, general agreement existed on the importance of greater national collaboration and communication regarding drug shortage management strategies. This could include PBM guidance on specific shortage management opportunities or establishing collaborations by region or VISN. These possibilities may be more realistically attainable in comparison to modifying federal regulations on drug product procurement during active shortages, which requires an act of Congress. Many of the survey participants endorsed a drug shortage task force within their facility. Coordinating interaction between preexisting or newly established task forces or working groups on a monthly or quarterly basis may provide fruitful interactions and the exchange of strategies to reduce shortage impact on institutional cost, efficiency, and patient care.

Limitations

Quantifying the extent of drug shortage impact on patient safety and institutional costs is a difficult task. The procurement records data used for the analysis of a single VAMC were gathered through manual review of stored paper invoices, opening the possibility for missing data. It is also difficult to extrapolate the sum of indirect costs such as process changes, alternative product utilization, and pharmacy staffing resources as additional financial burdens to the affected institution. Any quantifiable cost assessment also is biased by contract terms between the VA and wholesalers in which unavailable products that must be purchased off-contract are subsequently reimbursed through credit or alternative means.

Patient safety events are frequently underreported, leading to underestimation of true safety event incidence. Given that these events are documented by multiple disciplines and that many of these documenters may not be aware consistently of the drug products and volume impacted by shortage, elucidating safety events unfolding in relation to shortage also is difficult to quantify.

The response rate for the survey was low but near the expected rate for this methodology. Feedback from several facilities was received, citing competing demands and workforce shortage as barriers to participation. The survey also was limited by reporting bias and recall bias. As assessment of prespecified past drug shortages may require intimate knowledge of pharmacy department processes and mitigation strategies, the accuracy of question answering may have been limited to the length of time the points of contact had been in their current position.

Conclusion

Drug shortages are a pervasive barrier to patient care within larger facilities of the VA health care system, similar to what has been characterized in the private sector. As a result of these shortages and the mitigation strategies to reduce their burden, many facilities endorsed trends in increasing workload for staff, institutional operation costs, and risk for patient safety and care quality concerns. Due to the demands of shortages, some facilities have implemented drug shortage task forces or equivalent groups to specifically manage these issues. Moving forward, the VA health care system may benefit from similar task forces or working groups at the VISN level, to aid in collaborative efforts to respond to shortage. Support for revising federal regulations on procurement in times of shortage and enhanced PBM drug shortage management guidance also was endorsed.

1. Cherici C, Frazier J, Feldman M, et al. Navigating drug shortages in American healthcare: a premier healthcare alliance analysis. https://www.heartland.org/_template-assets/documents/publications/30103.pdf. Published March 2011. Accessed December 5, 2017.

2. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP drug shortage statistics. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Shortage-Resources/Drug-Shortages-Statistics. Updated 2017. Accessed December 5, 2017.

3. Dooren JC. Most hospitals face drug shortages. The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304584404576442211187884744. Published July 13, 2011. Accessed December 5, 2017.

4. Fink S. Drug shortages forcing hard decisions on rationing treatment. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/29/us/drug-shortages-forcing-hard-decisions-on-rationing-treatments.html. Published January 29, 2016. Accessed December 5, 2017.

5. Loftus P. Drug shortages frustrate doctors, patients. The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-drug-shortages-frustrate-doctors-patients-1433125793. Published May, 31, 2015. Accessed December 5, 2017.

6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Strategic plan for preventing and mitigating drug shortages. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugShortages/UCM372566.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed August 22, 2016.

7. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Quick facts. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Quick_Facts.asp. Updated November 20, 2017. Accessed December 5, 2017.

8. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of the Inspector General. Audit of Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy Program. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-15-05255-422.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2017.

9. Mazer-Amirshahi M, Pourmand A, Singer S, Pines JM, van den Anker J. Critical drug shortages: implications for emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(6):704-711.

10. McBride A, Holle LM, Westendorf C, et al. National survey on the effect of oncology drug shortages on cancer care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(7):609-617.

11. Caulder CR, Mehta B, Bookstaver PB, Sims LD, Stevenson B; South Carolina Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Impact of drug shortages on health system pharmacies in the southeastern United States. Hosp Pharm. 2015;50(4):279-286.

12. Florida Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Conservation strategies for IV fluids. http://www.fshp.org/news/165998/Conservation-Strategies-for-IV-Fluid.htm. Accessed December 11, 2017.

13. Federal Acquisition Regulation Site. FAR—Part 13 Simplified Acquisition Procedures, 13 CFR §§ 201-302. http://farsite.hill.af.mil/reghtml/regs/far2afmcfars/fardfars/far/13.htm. Updated January 13, 2017. Accessed December 5, 2017.

Drug product shortages threaten health care quality and public health by creating barriers to optimal care. The frequency of drug shortages has risen dramatically since 2005 and now influences broad areas of health care practice. More than 400 generic drug products have been affected, forcing institutions to purchase costly brand-name products, substitute alternative therapies, or procure from gray market vendors at increased institutional costs.1 Scarcity and cost have potential to negatively impact patient outcomes and the ability of health care organizations to respond to the needs of their patients.

Background

Although constantly fluctuating, the number of active shortages reached a height of 320 products at the end the third quarter of 2014.2 A 2011 analysis from Premier Healthcare Alliance estimated the added cost of purchasing brand, generic, or alternative drugs due to shortage may have inflated hospital costs by $200 million annually.1 In 2016, the number of active shortages dropped to 176, suggesting a downward trend. However, the drug supply chain remains a concern for pharmacies in the U.S.

Despite creative approaches to shortage management, the variable characteristics of shortages make planning difficult. For example, the drug product in short supply may or may not have an alternative for use in similar clinical scenarios. The impact of shortages of medications lacking an equivalent alternative product has been documented, such as the past shortage of succinylcholine for anesthesia, resulting in surgery cancellations when an alternative paralytic agent was not appropriate.3 In 2016, the Cleveland Clinic reported undertaking “military-style triage” in determining patients who required use of aminocaproic acid during open heart surgery due to its limited supply.4 Decisions to reserve drug supply for emergency use and prefilling syringes under pharmacy supervision to extend stability and shelf life are short-term solutions to larger, systemic issues. Unfortunately, these scenarios have the potential to disrupt patient care and diminish health outcomes.

Shortages of products that have an available therapeutic substitution may seem easily manageable, but additional considerations may be present. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is considered the drug of choice for bladder cancer. In 2011, there was a shortage of the BCG vaccine after mold was discovered in the formulation.5 Providers were forced to choose between reducing or reallocating the dose of BCG, turning away patient, or substituting mitomycin C, which is less effective and costlier. When tamsulosin capsules became difficult to obtain in 2014, some institutions began switching patients to alfuzosin.6 Although alfuzosin is similar in mechanism to tamsulosin, it may prolong the QTc interval. Not only did this substitution present a contraindication for patients with elevated QTc intervals or who were already receiving concomitant medications that prolonged the QTc interval, but also it required additional cost and resources needed to update electrocardiograms.

VA Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacies

The VHA serves nearly 9 million patients at more than 1,200 facilities across the U.S.7 This large patient population results in an estimated 149 million outpatient prescriptions annually.8 About 80% of these are distributed by mail through 7 VA consolidated mail outpatient pharmacies (CMOPs). When drug scarcity impedes the ability of the CMOP to respond to medication demand, the local facility must fill these prescriptions. These rejections sent back to the facility impact workload, patient wait times, and access to medication therapy. Barriers to medication procurement in the VA also stem from regulations based on legislation, including the Trade Agreements Act, Drug Supply Chain Security Act, and the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) (Table).

The impact of drug shortages has been described previously in the private sector, particularly for emergency medicine and chemotherapy.9,10 However, the impact of drug shortages on health care provision to veteran populations within the VA has not previously been analyzed. Due to the unique procurement regulations that influence the VA and the importance of continuing to provide optimal health care services to veterans, assessing the impact of drug shortages on patient safety and health care costs is necessary in informing policy decisions and guiding recommendations for mitigation strategies. The purpose of this study was to assess the influence of drug shortages on institutional costs and patient care within VA facilities and formulate recommendations for enhanced mitigation of this issue.

Methods

The primary outcome of this study was to characterize the impact of drug shortages on institutional cost and patient safety events among VHA facilities. Secondary outcomes included subgroup evaluation in reported drug shortage impact among 1a, 1b, and 1c complexity VA facility survey respondents and assessment of drug shortage impact on CMOP prescription order fulfillment and operation cost.

Definitions

The complexity ranking system is a facility grouping method used within the VA to characterize the level of service provision, teaching and research opportunities, patient volume, intensive care unit level, and other factors offered by a VA site. Rankings start from 1 (highest level of services offered) to 3 (lowest level of services offered), with level 1 facilities further divided into a, b, and c subdivisions. A level 1a facility will be larger with more services offered than a 1b, which is larger and offers more services than a 1c facility. The VA facilities are further characterized by regional distribution. Sites are grouped under VISNs of which there are currently 21.

The CMOP program was responsible for dispensing about 119 million outpatient prescriptions in 2016 and includes designated sites for the dispensing of controlled substances and supply items. The VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) oversees formulary management, plans national drug policy, promotes safe and appropriate drug therapy, and delivers high-quality and sustainable pharmacy benefits for veterans.

Study Design

A descriptive study was initiated to characterize the impact of drug shortages among VA facilities. An analysis of administrative medication safety event reporting and institutional costs data at the Denver VAMC in Colorado was done, focusing on predetermined drug products involved in a recent shortage. The analysis was accomplished through a review of the VA adverse drug events reporting system (VA ADERS) reports and a local medication errors quality improvement database and paper procurement records, respectively. Concurrently, a survey was disseminated among qualifying VA facilities across the country that sought to characterize the impact of drug shortages nationally.

Sample Selection

Denver VAMC. The Denver VAMC, where the authors were located, was selected as the local sample site. The intention was to compare the strategies used locally with strategies used among similar (level 1a, 1b, and 1c) facilities. Preselected “cost-impacting” drug products were identified through a review of historic shortages with a significant local impact. These drugs were defined as low cost/high utilization (eg, tamsulosin 0.4-mg capsules and ketorolac solution), medium cost/utilization (eg, piperacillin/tazobactam IV solutions and aminocaproic acid solution), and high cost/low utilization (eg, nitroprusside IV solution and BCG vaccine solution). Additionally, patient safety event data reported internally for quality improvement and locally via VA ADERS were reviewed for preselected “safety impact” drug products and included BCG vaccine, tamsulosin capsules, IV fluid products, calcium gluconate and chloride injections, and aminocaproic acid injection.

National Survey. The authors identified 84 level 1 complexity facilities and used the PBM pharmacy directory to contact the administrative personnel representing each facility. These representatives identified a point of contact to aid in survey completion. A separate survey also was sent to the CMOP facilities (survey outlines available at www.fedprac.com).

Data Collection

Denver VAMC. Financial data were sampled through a manual review of paper procurement records stored by date in the inpatient pharmacy of the Denver VAMC. Variables included units of product used over the period of drug shortage, cost per unit during shortage, and cost per unit before shortage. This information also was supplemented with data from the prescription processing software’s drug file. Patient safety data were gathered through query of the identified event reporting databases for the prespecified drug on shortage. These variables included the type of error and the effect the error had on the patient.

National Survey. Data collection focused on notable drug shortages and patient safety reporting between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2016. The survey was maintained in a facility-specific spreadsheet. Editing capabilities were disabled for all actions other than responding to questions. Recipients were followed up with a courtesy e-mail after 2 weeks and another 2 times unless a survey was received. Data were de-identified and aggregated for analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) descriptive statistics were used to relay information from this assessment. Extrapolations from procurement cost data and drug product utilization were used to estimate the enhanced direct cost associated with identified drug shortages. Similar extrapolations were used to estimate the cost associated with shortages leading to CMOP rejection and local fill.

Results

Survey completion totaled 20% of invited facilities (n = 17). Good geographic and VISN distribution was noted with representatives from VISNs 2, 4, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 16, 21, and 22. VISNs 10 and 12 provided the most representation with 3 participants, each. Level 1a facilities participated most (n = 9), followed by 1b (n = 6) and 1c (n = 2). Participating facilities reported a mean (SD) of 54 (21.5) pharmacists and 34 (15.3) pharmacy technician staff members employed. The most common reason for not participating was lack of personnel resources and competing demands. The CMOP participation was 100% (n = 7) and completed through a coordinated response.

Results of the budgetary increase and staff member time allocation survey assessments are provided (Figures 1 and 2). Five facilities provided an annual estimate of increased cost due to acquisition of drugs on shortage through open market purchases that ranged from about $150,000 to $750,000. Nearly half of the surveyed facilities endorsed having a drug shortage task force (n = 8) to respond to drug shortages and mitigate their impact.

Regarding drug product allocation, only 2 facilities did not have current restrictions for use due to a shortage. Many had between 1 and 10 of these restrictions implemented to conserve supply (n = 11, 64%), 2 facilities reported 11 to 20 restrictions, and 2 facilities noted more than 30 restrictions. Similarly, 3 facilities had not needed to revise any current treatment protocols due to drug shortages. The majority of facilities had revised 1 to 5 current protocols (n = 12, 70%), 1 revised 6 to 10 protocols, and 1 facility revised more than 10 protocols.

In assessing patient safety concerns, 1 facility identified a history of transferring patients to alternative medical sites for the patients to obtain necessary medication impacted by a local shortage. Additionally, during the BCG vaccine shortage, 6 facilities (35.3%) substituted mitomycin C for the treatment of urinary bladder cancer.

Most participants either agreed (n = 8, 47.0%) or strongly agreed (n = 4, 23.5%) that modifications to FAR to increase purchasing opportunities from foreign distributors during drug shortage would help mitigate the impact of such shortages. Similarly, most participants agreed (n = 10, 58.8%) or strongly agreed (n = 3, 17.6%) that PBM guidance on drug shortage management would help efficiently and effectively respond to issues that might arise. The consensus of participants also agreed (n = 13, 76.5%) that organized collaborations or working groups within each VISN might help assist in drug shortage management.

The CMOP facility data revealed that 2 sites did not require dedicated staffing to respond to shortages, and 3 sites had not experienced cost increases because of shortages. Pharmacist use varied between sites, with 2 facilities using 1 to 10 pharmacist h/wk, and 1 facility using 11 to 20 pharmacist h/wk, and 1 facility using 21 to 30 pharmacist h/wk. Technician utilization was more pronounced, with 2 facilities using more than 30 technician h/wk, and 2 facilities using 1 to 10 technician h/wk. Workload and costs may have been influenced in other ways as 3 sites endorsed using overtime pay, shifting product responsibility between CMOPs, prolonging patient wait times, and close monitoring for each. In fiscal year 2015, some sites experienced a 1% to 5% (n = 2) and 6% to 10% (n = 1) increase in operation cost attributable to shortage. Results from fiscal year 2016 showed that some sites continued to see a 1% to 5% (n = 1) and 6% to 10% (n = 2) increase in operation cost attributable to shortage.

Through aggregation of CMOP responses on the number of prescriptions sent back to local facility for fill due to back order, a downward trend in the total number of rejections was seen over the 2.5 fiscal years assessed. This amounted to more than 1 million rejections in fiscal year 2015, about 788,000 rejections in 2016, and about 318,000 rejections through the first 2 quarters of 2017.

A consistent rise in the medication procurement budget requirement was characterized within the single VA facility review. The quarterly median increase was 2.7% over 2.5 years (min: -1.4%; max: 6.6%) for total outpatient medication costs, excluding hepatitis C antiviral therapies. Procurement cost records were insufficient to characterize historic expenditures for 4 of the prespecified drug products. The data collected on tamsulosin capsule and nitroprusside vial procurement during shortage is provided (Figures 3 and 4). Over the time frame of procurement records found on review, the added costs of nitroprusside vials and tamsulosin capsules were $22,766.09 (+167.9% of base cost) and $17,433.70 (+657.3% of base cost), respectively. No patient safety data were found on review.

Discussion

Drug product shortages represent a barrier to quality and efficiency across health care institutions. A survey of health system pharmacies in the southeastern U.S. found that the majority of respondents tracking shortage data reported a 300% to 500% markup by alternative or gray market suppliers for hard-to-find medications.11 These reports are similar to the authors’ analyses of the trends in increased procurement expenditures documented during the tamsulosin capsule and nitroprusside vial shortages and indirectly correlate with the survey results indicating that most facilities endorsed a trend in operation cost increase attributable to drugs product shortage. The estimated annual costs for open market purchases further informs the financial burden aggregated by this issue.

Indirect costs from drug shortage further complicated quantifying the impact of shortages. Many facilities acknowledged the indirect influence drug shortages have on staffing and workload due to the implementation of mitigation strategies. Most participants found it necessary to establish restrictions for use in addition to altering protocols. These required the time investment of essential personnel from development through execution and education. Situations also can arise for mass therapeutic substitution. In this example, pharmacy staff may be required to oversee medication transition from the product on shortage to an appropriate alternative. When substitution involves hundreds or thousands of outpatient prescriptions, such as the tamsulosin shortage, the process may be tedious and time consuming, depending on the level of clinical decision making needed to determine patient candidacy for transitioning products.

Improving institutional cost efficiency becomes a significant challenge with persistent drug shortages. Professional advocacy groups, such as the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), help provide guidance to organizations constrained by specific drug shortages.12 Staff knowledgeable in allocation, supply considerations, and product repackaging and stability data also are essential. Other mitigation strategies include automatic substitutions, restrictions for use or inventory control strategies, and open market procurement, or borrowing from other institutions.

Data gathered from the survey of CMOP facilities also helped elucidate strategies used to mitigate drug shortage impacts for those respondents impacted by shortage. Likely, the 2 CMOP facilities without dedicated staff focused on shortages are those whose outpatient prescription fulfillment responsibility were focused on supply items or controlled substances. The impacted CMOP respondents cited overtime pay, shifting product responsibility, and prolonging patient wait times as the most frequently employed mitigation strategies. When these and other strategies fail to manage a shortage, prescriptions are often sent back to the local facility to be filled. Unfortunately for these facilities, the same mitigation strategies used by CMOP are not always feasible. Overtime pay may not be possible given staffing and budgetary resources, sending prescriptions back to facilities in itself prolongs patient wait times, and local medical centers do not have the option of shifting product responsibility between sites or sending the prescription to another facility. Herein lies 1 rationale for the CMOP effort to reduce the volume of prescriptions sent back to local medical centers.

Multiple offices within the FDA have roles in the mitigation of national drug shortages within their regulatory purview. Much of the recent focus stems from provisions enacted under Title X of the FDA Safety and Innovation Act of 2012, which addresses problems in the drug-supply chain.12 Rectifying a shortage involves short- and long-term strategic planning to address supply, distribution, and market reaction to need. Collaboration between the FDA and manufacturers is one method by which demand can be satisfied through the coordination of resources, expedition of inspections, and root cause analysis of the shortage.

Similar collaborations within the VA were viewed favorably by respondents and might yield productive relationships if regional or VISN working groups were to be established. Alternative long-term strategies are executed through regulation, particularly concerning the importation of foreign manufactured drugs and regulatory discretion on supplier vetting. Despite a strong respondent consensus that regulatory modifications of foreign product importation in the setting of a drug shortage may be beneficial, such a change would require a congressional action and is not likely to be timely. Unfortunately, gray market pharmaceutical distribution, driven by wholesaler stockpiling to raise prices, is separate from manufacturer driven shortages and falls outside the FDA’s regulatory purview and institutional mitigation strategies.

Although based on this limited survey, general agreement existed on the importance of greater national collaboration and communication regarding drug shortage management strategies. This could include PBM guidance on specific shortage management opportunities or establishing collaborations by region or VISN. These possibilities may be more realistically attainable in comparison to modifying federal regulations on drug product procurement during active shortages, which requires an act of Congress. Many of the survey participants endorsed a drug shortage task force within their facility. Coordinating interaction between preexisting or newly established task forces or working groups on a monthly or quarterly basis may provide fruitful interactions and the exchange of strategies to reduce shortage impact on institutional cost, efficiency, and patient care.

Limitations

Quantifying the extent of drug shortage impact on patient safety and institutional costs is a difficult task. The procurement records data used for the analysis of a single VAMC were gathered through manual review of stored paper invoices, opening the possibility for missing data. It is also difficult to extrapolate the sum of indirect costs such as process changes, alternative product utilization, and pharmacy staffing resources as additional financial burdens to the affected institution. Any quantifiable cost assessment also is biased by contract terms between the VA and wholesalers in which unavailable products that must be purchased off-contract are subsequently reimbursed through credit or alternative means.

Patient safety events are frequently underreported, leading to underestimation of true safety event incidence. Given that these events are documented by multiple disciplines and that many of these documenters may not be aware consistently of the drug products and volume impacted by shortage, elucidating safety events unfolding in relation to shortage also is difficult to quantify.

The response rate for the survey was low but near the expected rate for this methodology. Feedback from several facilities was received, citing competing demands and workforce shortage as barriers to participation. The survey also was limited by reporting bias and recall bias. As assessment of prespecified past drug shortages may require intimate knowledge of pharmacy department processes and mitigation strategies, the accuracy of question answering may have been limited to the length of time the points of contact had been in their current position.

Conclusion

Drug shortages are a pervasive barrier to patient care within larger facilities of the VA health care system, similar to what has been characterized in the private sector. As a result of these shortages and the mitigation strategies to reduce their burden, many facilities endorsed trends in increasing workload for staff, institutional operation costs, and risk for patient safety and care quality concerns. Due to the demands of shortages, some facilities have implemented drug shortage task forces or equivalent groups to specifically manage these issues. Moving forward, the VA health care system may benefit from similar task forces or working groups at the VISN level, to aid in collaborative efforts to respond to shortage. Support for revising federal regulations on procurement in times of shortage and enhanced PBM drug shortage management guidance also was endorsed.

Drug product shortages threaten health care quality and public health by creating barriers to optimal care. The frequency of drug shortages has risen dramatically since 2005 and now influences broad areas of health care practice. More than 400 generic drug products have been affected, forcing institutions to purchase costly brand-name products, substitute alternative therapies, or procure from gray market vendors at increased institutional costs.1 Scarcity and cost have potential to negatively impact patient outcomes and the ability of health care organizations to respond to the needs of their patients.

Background

Although constantly fluctuating, the number of active shortages reached a height of 320 products at the end the third quarter of 2014.2 A 2011 analysis from Premier Healthcare Alliance estimated the added cost of purchasing brand, generic, or alternative drugs due to shortage may have inflated hospital costs by $200 million annually.1 In 2016, the number of active shortages dropped to 176, suggesting a downward trend. However, the drug supply chain remains a concern for pharmacies in the U.S.

Despite creative approaches to shortage management, the variable characteristics of shortages make planning difficult. For example, the drug product in short supply may or may not have an alternative for use in similar clinical scenarios. The impact of shortages of medications lacking an equivalent alternative product has been documented, such as the past shortage of succinylcholine for anesthesia, resulting in surgery cancellations when an alternative paralytic agent was not appropriate.3 In 2016, the Cleveland Clinic reported undertaking “military-style triage” in determining patients who required use of aminocaproic acid during open heart surgery due to its limited supply.4 Decisions to reserve drug supply for emergency use and prefilling syringes under pharmacy supervision to extend stability and shelf life are short-term solutions to larger, systemic issues. Unfortunately, these scenarios have the potential to disrupt patient care and diminish health outcomes.

Shortages of products that have an available therapeutic substitution may seem easily manageable, but additional considerations may be present. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is considered the drug of choice for bladder cancer. In 2011, there was a shortage of the BCG vaccine after mold was discovered in the formulation.5 Providers were forced to choose between reducing or reallocating the dose of BCG, turning away patient, or substituting mitomycin C, which is less effective and costlier. When tamsulosin capsules became difficult to obtain in 2014, some institutions began switching patients to alfuzosin.6 Although alfuzosin is similar in mechanism to tamsulosin, it may prolong the QTc interval. Not only did this substitution present a contraindication for patients with elevated QTc intervals or who were already receiving concomitant medications that prolonged the QTc interval, but also it required additional cost and resources needed to update electrocardiograms.

VA Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacies

The VHA serves nearly 9 million patients at more than 1,200 facilities across the U.S.7 This large patient population results in an estimated 149 million outpatient prescriptions annually.8 About 80% of these are distributed by mail through 7 VA consolidated mail outpatient pharmacies (CMOPs). When drug scarcity impedes the ability of the CMOP to respond to medication demand, the local facility must fill these prescriptions. These rejections sent back to the facility impact workload, patient wait times, and access to medication therapy. Barriers to medication procurement in the VA also stem from regulations based on legislation, including the Trade Agreements Act, Drug Supply Chain Security Act, and the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) (Table).

The impact of drug shortages has been described previously in the private sector, particularly for emergency medicine and chemotherapy.9,10 However, the impact of drug shortages on health care provision to veteran populations within the VA has not previously been analyzed. Due to the unique procurement regulations that influence the VA and the importance of continuing to provide optimal health care services to veterans, assessing the impact of drug shortages on patient safety and health care costs is necessary in informing policy decisions and guiding recommendations for mitigation strategies. The purpose of this study was to assess the influence of drug shortages on institutional costs and patient care within VA facilities and formulate recommendations for enhanced mitigation of this issue.

Methods

The primary outcome of this study was to characterize the impact of drug shortages on institutional cost and patient safety events among VHA facilities. Secondary outcomes included subgroup evaluation in reported drug shortage impact among 1a, 1b, and 1c complexity VA facility survey respondents and assessment of drug shortage impact on CMOP prescription order fulfillment and operation cost.

Definitions

The complexity ranking system is a facility grouping method used within the VA to characterize the level of service provision, teaching and research opportunities, patient volume, intensive care unit level, and other factors offered by a VA site. Rankings start from 1 (highest level of services offered) to 3 (lowest level of services offered), with level 1 facilities further divided into a, b, and c subdivisions. A level 1a facility will be larger with more services offered than a 1b, which is larger and offers more services than a 1c facility. The VA facilities are further characterized by regional distribution. Sites are grouped under VISNs of which there are currently 21.

The CMOP program was responsible for dispensing about 119 million outpatient prescriptions in 2016 and includes designated sites for the dispensing of controlled substances and supply items. The VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Service (PBM) oversees formulary management, plans national drug policy, promotes safe and appropriate drug therapy, and delivers high-quality and sustainable pharmacy benefits for veterans.

Study Design

A descriptive study was initiated to characterize the impact of drug shortages among VA facilities. An analysis of administrative medication safety event reporting and institutional costs data at the Denver VAMC in Colorado was done, focusing on predetermined drug products involved in a recent shortage. The analysis was accomplished through a review of the VA adverse drug events reporting system (VA ADERS) reports and a local medication errors quality improvement database and paper procurement records, respectively. Concurrently, a survey was disseminated among qualifying VA facilities across the country that sought to characterize the impact of drug shortages nationally.

Sample Selection

Denver VAMC. The Denver VAMC, where the authors were located, was selected as the local sample site. The intention was to compare the strategies used locally with strategies used among similar (level 1a, 1b, and 1c) facilities. Preselected “cost-impacting” drug products were identified through a review of historic shortages with a significant local impact. These drugs were defined as low cost/high utilization (eg, tamsulosin 0.4-mg capsules and ketorolac solution), medium cost/utilization (eg, piperacillin/tazobactam IV solutions and aminocaproic acid solution), and high cost/low utilization (eg, nitroprusside IV solution and BCG vaccine solution). Additionally, patient safety event data reported internally for quality improvement and locally via VA ADERS were reviewed for preselected “safety impact” drug products and included BCG vaccine, tamsulosin capsules, IV fluid products, calcium gluconate and chloride injections, and aminocaproic acid injection.

National Survey. The authors identified 84 level 1 complexity facilities and used the PBM pharmacy directory to contact the administrative personnel representing each facility. These representatives identified a point of contact to aid in survey completion. A separate survey also was sent to the CMOP facilities (survey outlines available at www.fedprac.com).

Data Collection

Denver VAMC. Financial data were sampled through a manual review of paper procurement records stored by date in the inpatient pharmacy of the Denver VAMC. Variables included units of product used over the period of drug shortage, cost per unit during shortage, and cost per unit before shortage. This information also was supplemented with data from the prescription processing software’s drug file. Patient safety data were gathered through query of the identified event reporting databases for the prespecified drug on shortage. These variables included the type of error and the effect the error had on the patient.

National Survey. Data collection focused on notable drug shortages and patient safety reporting between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2016. The survey was maintained in a facility-specific spreadsheet. Editing capabilities were disabled for all actions other than responding to questions. Recipients were followed up with a courtesy e-mail after 2 weeks and another 2 times unless a survey was received. Data were de-identified and aggregated for analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) descriptive statistics were used to relay information from this assessment. Extrapolations from procurement cost data and drug product utilization were used to estimate the enhanced direct cost associated with identified drug shortages. Similar extrapolations were used to estimate the cost associated with shortages leading to CMOP rejection and local fill.

Results

Survey completion totaled 20% of invited facilities (n = 17). Good geographic and VISN distribution was noted with representatives from VISNs 2, 4, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 16, 21, and 22. VISNs 10 and 12 provided the most representation with 3 participants, each. Level 1a facilities participated most (n = 9), followed by 1b (n = 6) and 1c (n = 2). Participating facilities reported a mean (SD) of 54 (21.5) pharmacists and 34 (15.3) pharmacy technician staff members employed. The most common reason for not participating was lack of personnel resources and competing demands. The CMOP participation was 100% (n = 7) and completed through a coordinated response.

Results of the budgetary increase and staff member time allocation survey assessments are provided (Figures 1 and 2). Five facilities provided an annual estimate of increased cost due to acquisition of drugs on shortage through open market purchases that ranged from about $150,000 to $750,000. Nearly half of the surveyed facilities endorsed having a drug shortage task force (n = 8) to respond to drug shortages and mitigate their impact.

Regarding drug product allocation, only 2 facilities did not have current restrictions for use due to a shortage. Many had between 1 and 10 of these restrictions implemented to conserve supply (n = 11, 64%), 2 facilities reported 11 to 20 restrictions, and 2 facilities noted more than 30 restrictions. Similarly, 3 facilities had not needed to revise any current treatment protocols due to drug shortages. The majority of facilities had revised 1 to 5 current protocols (n = 12, 70%), 1 revised 6 to 10 protocols, and 1 facility revised more than 10 protocols.

In assessing patient safety concerns, 1 facility identified a history of transferring patients to alternative medical sites for the patients to obtain necessary medication impacted by a local shortage. Additionally, during the BCG vaccine shortage, 6 facilities (35.3%) substituted mitomycin C for the treatment of urinary bladder cancer.

Most participants either agreed (n = 8, 47.0%) or strongly agreed (n = 4, 23.5%) that modifications to FAR to increase purchasing opportunities from foreign distributors during drug shortage would help mitigate the impact of such shortages. Similarly, most participants agreed (n = 10, 58.8%) or strongly agreed (n = 3, 17.6%) that PBM guidance on drug shortage management would help efficiently and effectively respond to issues that might arise. The consensus of participants also agreed (n = 13, 76.5%) that organized collaborations or working groups within each VISN might help assist in drug shortage management.

The CMOP facility data revealed that 2 sites did not require dedicated staffing to respond to shortages, and 3 sites had not experienced cost increases because of shortages. Pharmacist use varied between sites, with 2 facilities using 1 to 10 pharmacist h/wk, and 1 facility using 11 to 20 pharmacist h/wk, and 1 facility using 21 to 30 pharmacist h/wk. Technician utilization was more pronounced, with 2 facilities using more than 30 technician h/wk, and 2 facilities using 1 to 10 technician h/wk. Workload and costs may have been influenced in other ways as 3 sites endorsed using overtime pay, shifting product responsibility between CMOPs, prolonging patient wait times, and close monitoring for each. In fiscal year 2015, some sites experienced a 1% to 5% (n = 2) and 6% to 10% (n = 1) increase in operation cost attributable to shortage. Results from fiscal year 2016 showed that some sites continued to see a 1% to 5% (n = 1) and 6% to 10% (n = 2) increase in operation cost attributable to shortage.

Through aggregation of CMOP responses on the number of prescriptions sent back to local facility for fill due to back order, a downward trend in the total number of rejections was seen over the 2.5 fiscal years assessed. This amounted to more than 1 million rejections in fiscal year 2015, about 788,000 rejections in 2016, and about 318,000 rejections through the first 2 quarters of 2017.

A consistent rise in the medication procurement budget requirement was characterized within the single VA facility review. The quarterly median increase was 2.7% over 2.5 years (min: -1.4%; max: 6.6%) for total outpatient medication costs, excluding hepatitis C antiviral therapies. Procurement cost records were insufficient to characterize historic expenditures for 4 of the prespecified drug products. The data collected on tamsulosin capsule and nitroprusside vial procurement during shortage is provided (Figures 3 and 4). Over the time frame of procurement records found on review, the added costs of nitroprusside vials and tamsulosin capsules were $22,766.09 (+167.9% of base cost) and $17,433.70 (+657.3% of base cost), respectively. No patient safety data were found on review.

Discussion

Drug product shortages represent a barrier to quality and efficiency across health care institutions. A survey of health system pharmacies in the southeastern U.S. found that the majority of respondents tracking shortage data reported a 300% to 500% markup by alternative or gray market suppliers for hard-to-find medications.11 These reports are similar to the authors’ analyses of the trends in increased procurement expenditures documented during the tamsulosin capsule and nitroprusside vial shortages and indirectly correlate with the survey results indicating that most facilities endorsed a trend in operation cost increase attributable to drugs product shortage. The estimated annual costs for open market purchases further informs the financial burden aggregated by this issue.

Indirect costs from drug shortage further complicated quantifying the impact of shortages. Many facilities acknowledged the indirect influence drug shortages have on staffing and workload due to the implementation of mitigation strategies. Most participants found it necessary to establish restrictions for use in addition to altering protocols. These required the time investment of essential personnel from development through execution and education. Situations also can arise for mass therapeutic substitution. In this example, pharmacy staff may be required to oversee medication transition from the product on shortage to an appropriate alternative. When substitution involves hundreds or thousands of outpatient prescriptions, such as the tamsulosin shortage, the process may be tedious and time consuming, depending on the level of clinical decision making needed to determine patient candidacy for transitioning products.

Improving institutional cost efficiency becomes a significant challenge with persistent drug shortages. Professional advocacy groups, such as the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), help provide guidance to organizations constrained by specific drug shortages.12 Staff knowledgeable in allocation, supply considerations, and product repackaging and stability data also are essential. Other mitigation strategies include automatic substitutions, restrictions for use or inventory control strategies, and open market procurement, or borrowing from other institutions.

Data gathered from the survey of CMOP facilities also helped elucidate strategies used to mitigate drug shortage impacts for those respondents impacted by shortage. Likely, the 2 CMOP facilities without dedicated staff focused on shortages are those whose outpatient prescription fulfillment responsibility were focused on supply items or controlled substances. The impacted CMOP respondents cited overtime pay, shifting product responsibility, and prolonging patient wait times as the most frequently employed mitigation strategies. When these and other strategies fail to manage a shortage, prescriptions are often sent back to the local facility to be filled. Unfortunately for these facilities, the same mitigation strategies used by CMOP are not always feasible. Overtime pay may not be possible given staffing and budgetary resources, sending prescriptions back to facilities in itself prolongs patient wait times, and local medical centers do not have the option of shifting product responsibility between sites or sending the prescription to another facility. Herein lies 1 rationale for the CMOP effort to reduce the volume of prescriptions sent back to local medical centers.

Multiple offices within the FDA have roles in the mitigation of national drug shortages within their regulatory purview. Much of the recent focus stems from provisions enacted under Title X of the FDA Safety and Innovation Act of 2012, which addresses problems in the drug-supply chain.12 Rectifying a shortage involves short- and long-term strategic planning to address supply, distribution, and market reaction to need. Collaboration between the FDA and manufacturers is one method by which demand can be satisfied through the coordination of resources, expedition of inspections, and root cause analysis of the shortage.

Similar collaborations within the VA were viewed favorably by respondents and might yield productive relationships if regional or VISN working groups were to be established. Alternative long-term strategies are executed through regulation, particularly concerning the importation of foreign manufactured drugs and regulatory discretion on supplier vetting. Despite a strong respondent consensus that regulatory modifications of foreign product importation in the setting of a drug shortage may be beneficial, such a change would require a congressional action and is not likely to be timely. Unfortunately, gray market pharmaceutical distribution, driven by wholesaler stockpiling to raise prices, is separate from manufacturer driven shortages and falls outside the FDA’s regulatory purview and institutional mitigation strategies.

Although based on this limited survey, general agreement existed on the importance of greater national collaboration and communication regarding drug shortage management strategies. This could include PBM guidance on specific shortage management opportunities or establishing collaborations by region or VISN. These possibilities may be more realistically attainable in comparison to modifying federal regulations on drug product procurement during active shortages, which requires an act of Congress. Many of the survey participants endorsed a drug shortage task force within their facility. Coordinating interaction between preexisting or newly established task forces or working groups on a monthly or quarterly basis may provide fruitful interactions and the exchange of strategies to reduce shortage impact on institutional cost, efficiency, and patient care.

Limitations

Quantifying the extent of drug shortage impact on patient safety and institutional costs is a difficult task. The procurement records data used for the analysis of a single VAMC were gathered through manual review of stored paper invoices, opening the possibility for missing data. It is also difficult to extrapolate the sum of indirect costs such as process changes, alternative product utilization, and pharmacy staffing resources as additional financial burdens to the affected institution. Any quantifiable cost assessment also is biased by contract terms between the VA and wholesalers in which unavailable products that must be purchased off-contract are subsequently reimbursed through credit or alternative means.

Patient safety events are frequently underreported, leading to underestimation of true safety event incidence. Given that these events are documented by multiple disciplines and that many of these documenters may not be aware consistently of the drug products and volume impacted by shortage, elucidating safety events unfolding in relation to shortage also is difficult to quantify.

The response rate for the survey was low but near the expected rate for this methodology. Feedback from several facilities was received, citing competing demands and workforce shortage as barriers to participation. The survey also was limited by reporting bias and recall bias. As assessment of prespecified past drug shortages may require intimate knowledge of pharmacy department processes and mitigation strategies, the accuracy of question answering may have been limited to the length of time the points of contact had been in their current position.

Conclusion

Drug shortages are a pervasive barrier to patient care within larger facilities of the VA health care system, similar to what has been characterized in the private sector. As a result of these shortages and the mitigation strategies to reduce their burden, many facilities endorsed trends in increasing workload for staff, institutional operation costs, and risk for patient safety and care quality concerns. Due to the demands of shortages, some facilities have implemented drug shortage task forces or equivalent groups to specifically manage these issues. Moving forward, the VA health care system may benefit from similar task forces or working groups at the VISN level, to aid in collaborative efforts to respond to shortage. Support for revising federal regulations on procurement in times of shortage and enhanced PBM drug shortage management guidance also was endorsed.

1. Cherici C, Frazier J, Feldman M, et al. Navigating drug shortages in American healthcare: a premier healthcare alliance analysis. https://www.heartland.org/_template-assets/documents/publications/30103.pdf. Published March 2011. Accessed December 5, 2017.

2. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP drug shortage statistics. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Shortage-Resources/Drug-Shortages-Statistics. Updated 2017. Accessed December 5, 2017.

3. Dooren JC. Most hospitals face drug shortages. The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304584404576442211187884744. Published July 13, 2011. Accessed December 5, 2017.

4. Fink S. Drug shortages forcing hard decisions on rationing treatment. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/29/us/drug-shortages-forcing-hard-decisions-on-rationing-treatments.html. Published January 29, 2016. Accessed December 5, 2017.

5. Loftus P. Drug shortages frustrate doctors, patients. The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-drug-shortages-frustrate-doctors-patients-1433125793. Published May, 31, 2015. Accessed December 5, 2017.

6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Strategic plan for preventing and mitigating drug shortages. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugShortages/UCM372566.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed August 22, 2016.

7. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Quick facts. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Quick_Facts.asp. Updated November 20, 2017. Accessed December 5, 2017.

8. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of the Inspector General. Audit of Consolidated Mail Outpatient Pharmacy Program. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-15-05255-422.pdf. Accessed December 11, 2017.

9. Mazer-Amirshahi M, Pourmand A, Singer S, Pines JM, van den Anker J. Critical drug shortages: implications for emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(6):704-711.

10. McBride A, Holle LM, Westendorf C, et al. National survey on the effect of oncology drug shortages on cancer care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(7):609-617.

11. Caulder CR, Mehta B, Bookstaver PB, Sims LD, Stevenson B; South Carolina Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Impact of drug shortages on health system pharmacies in the southeastern United States. Hosp Pharm. 2015;50(4):279-286.

12. Florida Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Conservation strategies for IV fluids. http://www.fshp.org/news/165998/Conservation-Strategies-for-IV-Fluid.htm. Accessed December 11, 2017.

13. Federal Acquisition Regulation Site. FAR—Part 13 Simplified Acquisition Procedures, 13 CFR §§ 201-302. http://farsite.hill.af.mil/reghtml/regs/far2afmcfars/fardfars/far/13.htm. Updated January 13, 2017. Accessed December 5, 2017.

1. Cherici C, Frazier J, Feldman M, et al. Navigating drug shortages in American healthcare: a premier healthcare alliance analysis. https://www.heartland.org/_template-assets/documents/publications/30103.pdf. Published March 2011. Accessed December 5, 2017.

2. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP drug shortage statistics. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Shortage-Resources/Drug-Shortages-Statistics. Updated 2017. Accessed December 5, 2017.

3. Dooren JC. Most hospitals face drug shortages. The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304584404576442211187884744. Published July 13, 2011. Accessed December 5, 2017.

4. Fink S. Drug shortages forcing hard decisions on rationing treatment. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/29/us/drug-shortages-forcing-hard-decisions-on-rationing-treatments.html. Published January 29, 2016. Accessed December 5, 2017.

5. Loftus P. Drug shortages frustrate doctors, patients. The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-drug-shortages-frustrate-doctors-patients-1433125793. Published May, 31, 2015. Accessed December 5, 2017.

6. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Strategic plan for preventing and mitigating drug shortages. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugShortages/UCM372566.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed August 22, 2016.

7. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Quick facts. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Quick_Facts.asp. Updated November 20, 2017. Accessed December 5, 2017.