User login

Clinical and Radiographic Outcomes of Total Shoulder Arthroplasty With a Hybrid Dual-Radii Glenoid Component

Take-Home Points

- The authors have developed a total shoulder glenoid prosthesis that conforms with the humeral head in its center and is nonconforming on its peripheral edge.

- All clinical survey and range of motion parameters demonstrated statistically significant improvements at final follow-up.

- Only 3 shoulders (1.7%) required revision surgery.

- Eighty-six (63%) of 136 shoulders demonstrated no radiographic evidence of glenoid loosening.

- This is the first and largest study that evaluates the clinical and radiographic outcomes of this hybrid shoulder prosthesis.

Fixation of the glenoid component is the limiting factor in modern total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Glenoid loosening, the most common long-term complication, necessitates revision in up to 12% of patients.1-4 By contrast, humeral component loosening is relatively uncommon, affecting as few as 0.34% of patients.5 Multiple long-term studies have found consistently high rates (45%-93%) of radiolucencies around the glenoid component.3,6,7 Although their clinical significance has been debated, radiolucencies around the glenoid component raise concern about progressive loss of fixation.

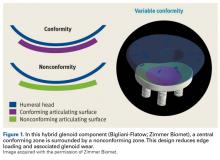

Since TSA was introduced in the 1970s, complications with the glenoid component have been addressed with 2 different designs: conforming (congruent) and nonconforming. In a congruent articulation, the radii of curvature of the glenoid and humeral head components are identical, whereas they differ in a nonconforming model. Joint conformity is inversely related to glenohumeral translation.8 Neer’s original TSA was made congruent in order to limit translation and maximize the contact area. However, this design results in edge loading and a so-called rocking-horse phenomenon, which may lead to glenoid loosening.9-13 Surgeons therefore have increasingly turned to nonconforming implants. In the nonconforming design, the radius of curvature of the humeral head is smaller than that of the glenoid. Although this design may reduce edge loading,14 it allows more translation and reduces the relative contact area of the glenohumeral joint. As a result, more contact stress is transmitted to the glenoid component, leading to polyethylene deformation and wear.15,16

Dual radii of curvature are designed to augment joint stability without increasing component wear. Biomechanical data have indicated that edge loading is not increased by having a central conforming region added to a nonconforming model.17 The clinical value of this prosthesis, however, has not been determined. Therefore, we conducted a study to describe the intermediate-term clinical and radiographic outcomes of TSAs that use a novel hybrid glenoid component.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved (protocol AAAD3473) by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University and was conducted in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations.

Patient Selection

At Columbia University Medical Center, Dr. Bigliani performed 196 TSAs with a hybrid glenoid component (Bigliani-Flatow; Zimmer Biomet) in 169 patients between September 1998 and November 2007. All patients had received a diagnosis of primary glenohumeral arthritis as defined by Neer.18 Patients with previous surgery such as rotator cuff repair or subacromial decompression were included in our review, and patients with a nonprimary form of arthritis, such as rheumatoid, posttraumatic, or post-capsulorrhaphy arthritis, were excluded.

Operative Technique

For all surgeries, Dr. Bigliani performed a subscapularis tenotomy with regional anesthesia and a standard deltopectoral approach. A partial anterior capsulectomy was performed to increase the glenoid’s visibility. The inferior labrum was removed with a needle-tip bovie while the axillary nerve was being protected with a metal finger or narrow Darrach retractor. After reaming and trialing, the final glenoid component was cemented into place. Cement was placed only in the peg or keel holes and pressurized twice before final implantation. Of the 196 glenoid components, 168 (86%) were pegged and 28 (14%) keeled; in addition,190 of these components were all-polyethylene, whereas 6 had trabecular-metal backing. All glenoid components incorporated the hybrid design of dual radii of curvature. After the glenoid was cemented, the final humeral component was placed in 30° of retroversion. Whenever posterior wear was found, retroversion was reduced by 5° to 10°. The humeral prosthesis was cemented in cases (104/196, 53%) of poor bone quality or a large canal.

After surgery, the patient’s sling was fitted with an abduction pillow and a swathe, to be worn the first 24 hours, and the arm was passively ranged. Patients typically were discharged on postoperative day 2. Then, for 2 weeks, they followed an assisted passive range of motion (ROM) protocol, with limited external rotation, for promotion of subscapularis healing.

Clinical Outcomes

Dr. Bigliani assessed preoperative ROM in all planes. During initial evaluation, patients completed a questionnaire that consisted of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey19,20 (SF-36) and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons21 (ASES) and Simple Shoulder Test22 (SST) surveys. Postoperative clinical data were collected from office follow-up visits, survey questionnaires, or both. Postoperative office data included ROM, subscapularis integrity testing (belly-press or lift-off), and any complications. Patients with <1 year of office follow-up were excluded. In addition, the same survey questionnaire that was used before surgery was mailed to all patients after surgery; then, for anyone who did not respond by mail, we attempted contact by telephone. Neer criteria were based on patients’ subjective assessment of each arm on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = very satisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = dissatisfied). Patients were also asked about any specific complications or revision operations since their index procedure.

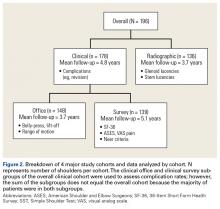

Physical examination and office follow-up data were obtained for 129 patients (148/196 shoulders, 76% follow-up) at a mean of 3.7 years (range 1.0-10.2 years) after surgery. Surveys were completed by 117 patients (139/196 shoulders, 71% follow-up) at a mean of 5.1 years (range, 1.6-11.2 years) after surgery. Only 15 patients had neither 1 year of office follow-up nor a completed questionnaire. The remaining 154 patients (178/196 shoulders, 91% follow-up) had clinical follow-up with office, mail, or telephone questionnaire at a mean of 4.8 years (range, 1.0-11.2 years) after surgery. This cohort of patients was used to determine rates of surgical revisions, subscapularis tears, dislocations, and other complications.

Radiographic Outcomes

Patients were included in the radiographic analysis if they had a shoulder radiograph at least 1 year after surgery. One hundred nineteen patients (136/196 shoulders, 69% follow-up) had radiographic follow-up at a mean of 3.7 years (range, 1.0-9.4 years) after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata Version 10.0. Paired t tests were used to compare preoperative and postoperative numerical data, including ROM and survey scores. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and set statistical significance at P < .05. For qualitative measures, the Fisher exact test was used. Survivorship analysis was performed according to the Kaplan-Meier method, with right-censored data for no event or missing data.25

Results

Clinical Analysis of Demographics

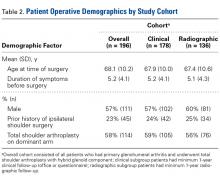

In demographics, the clinical and radiographic patient subgroups were similar to each other and to the overall study population (Table 2). Of 196 patients overall, 16 (8%) had a concomitant rotator cuff repair, and 27 (14%) underwent staged bilateral shoulder arthroplasties.

Clinical Analysis of ROM and Survey Scores

Operative shoulder ROM in forward elevation, external rotation at side, external rotation in abduction, and internal rotation all showed statistically significant (P < .001) improvement from before surgery to after surgery. Over 3.7 years, mean (SD) forward elevation improved from 107.3° (34.8°) to 159.0° (29.4°), external rotation at side improved from 20.4° (16.7°) to 49.4° (11.3°), and external rotation in abduction improved from 53.7° (24.3°) to 84.7° (9.1°). Internal rotation improved from a mean (SD) vertebral level of S1 (6.0 levels) to T9 (3.7 levels).

All validated survey scores also showed statistically significant (P < .001) improvement from before surgery to after surgery. Over 5.1 years, mean (SD) SF-36 scores improved from 64.9 (13.4) to 73.6 (17.1), ASES scores improved from 41.1 (22.5) to 82.7 (17.7), SST scores improved from 3.9 (2.8) to 9.7 (2.2), and visual analog scale pain scores improved from 5.6 (3.2) to 1.4 (2.1). Of 139 patients with follow-up, 130 (93.5%) were either satisfied or very satisfied with their TSA, and only 119 (86%) were either satisfied or very satisfied with the nonoperative shoulder.

Clinical Analysis of Postoperative Complications

Of the 178 shoulders evaluated for complications, 3 (1.7%) underwent revision surgery. Mean time to revision was 2.3 years (range, 1.5-3.9 years). Two revisions involved the glenoid component, and the third involved the humerus. In one of the glenoid cases, a 77-year-old woman fell and sustained a fracture at the base of the trabecular metal glenoid pegs; her component was revised to an all-polyethylene component, and she had no further complications. In the other glenoid case, a 73-year-old man’s all-polyethylene component loosened after 2 years and was revised to a trabecular metal implant, which loosened as well and was later converted to a hemiarthroplasty. In the humeral case, a 33-year-old man had his 4-year-old index TSA revised to a cemented stem and had no further complications.

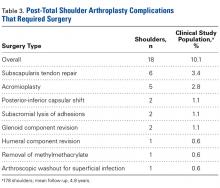

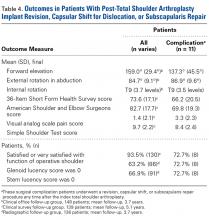

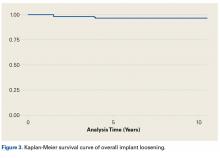

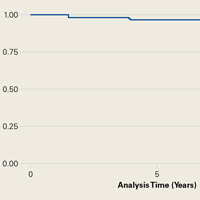

Table 4 compares the clinical and radiographic outcomes of patients who required subscapularis repair, capsular shift, or implant revision with the outcomes of all other study patients, and Figure 3 shows Kaplan-Meier survivorship.

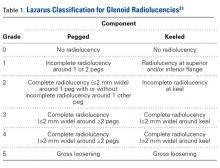

Postoperative Radiographic Analysis

Glenoid Component. At a mean of 3.7 years (minimum, 1 year) after surgery, 86 (63%) of 136 radiographically evaluated shoulders showed no glenoid lucencies; the other 50 (37%) showed ≥1 lucency. Of the 136 shoulders, 33 (24%) had a Lazarus score of 1, 15 (11%) had a score of 2, and only 2 (2%) had a score of 3. None of the shoulders had a score of 4 or 5.

Humeral Component. Of the 136 shoulders, 91 (67%) showed no lucencies in any of the 8 humeral stem zones; the other 45 (33%) showed 1 to 3 lucencies. Thirty (22%) of the 136 shoulders had 1 stem lucency zone, 8 (6%) had 2, and 3 (2%) had 3. None of the shoulders had >3 periprosthetic zones with lucent lines.

Discussion

In this article, we describe a hybrid glenoid TSA component with dual radii of curvature. Its central portion is congruent with the humeral head, and its peripheral portion is noncongruent and larger. The most significant finding of our study is the low rate (1.1%) of glenoid component revision 4.8 years after surgery. This rate is the lowest that has been reported in a study of ≥100 patients. Overall implant survival appeared as an almost flat Kaplan-Meir curve. We attribute this low revision rate to improved biomechanics with the hybrid glenoid design.

Symptomatic glenoid component loosening is the most common TSA complication.1,26-28 In a review of 73 Neer TSAs, Cofield7 found glenoid radiolucencies in 71% of patients 3.8 years after surgery. Radiographic evidence of loosening, defined as component migration, or tilt, or a circumferential lucency 1.5 mm thick, was present in another 11% of patients, and 4.1% developed symptomatic loosening that required glenoid revision. In a study with 12.2-year follow-up, Torchia and colleagues3 found rates of 84% for glenoid radiolucencies, 44% for radiographic loosening, and 5.6% for symptomatic loosening that required revision. In a systematic review of studies with follow-up of ≥10 years, Bohsali and colleagues27 found similar lucency and radiographic loosening rates and a 7% glenoid revision rate. These data suggest glenoid radiolucencies may progress to component loosening.

Degree of joint congruence is a key factor in glenoid loosening. Neer’s congruent design increases the contact area with concentric loading and reduces glenohumeral translation, which leads to reduced polyethylene wear and improved joint stability. In extreme arm positions, however, humeral head subluxation results in edge loading and a glenoid rocking-horse effect.9-13,17,29-31 Conversely, nonconforming implants allow increased glenohumeral translation without edge loading,14 though they also reduce the relative glenohumeral contact area and thus transmit more contact stress to the glenoid.16,17 A hybrid glenoid component with central conforming and peripheral nonconforming zones may reduce the rocking-horse effect while maximizing ROM and joint stability. Wang and colleagues32 studied the biomechanical properties of this glenoid design and found that the addition of a central conforming region did not increase edge loading.

Additional results from our study support the efficacy of a hybrid glenoid component. Patients’ clinical outcomes improved significantly. At 5.1 years after surgery, 93.5% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with their procedure and reported less satisfaction (86%) with the nonoperative shoulder. Also significant was the reduced number of radiolucencies. At 3.7 years after surgery, the overall percentage of shoulders with ≥1 glenoid radiolucency was 37%, considerably lower than the 82% reported by Cofield7 and the rates in more recent studies.3,16,33-36 Of the 178 shoulders in our study, 10 (5.6%) had subscapularis tears, and 6 (3.4%) of 178 had these tears surgically repaired. This 3.4% compares favorably with the 5.9% (of 119 patients) found by Miller and colleagues37 28 months after surgery. Of our 178 shoulders, 27 (15.2%) had clinically significant postoperative complications; 18 (10.1%) of the 178 had these complications surgically treated, and 9 (5.1%) had them managed nonoperatively. Bohsali and colleagues27 systematically reviewed 33 TSA studies and found a slightly higher complication rate (16.3%) 5.3 years after surgery. Furthermore, in our study, the 11 patients who underwent revision, capsular shift, or subscapularis repair had final outcomes comparable to those of the rest of our study population.

Our study had several potential weaknesses. First, its minimum clinical and radiographic follow-up was 1 year, whereas most long-term TSA series set a minimum of 2 years. We used 1 year because this was the first clinical study of the hybrid glenoid component design, and we wanted to maximize its sample size by reporting on intermediate-length outcomes. Even so, 93% (166/178) of our clinical patients and 83% (113/136) of our radiographic patients have had ≥2 years of follow-up, and we continue to follow all study patients for long-term outcomes. Another weakness of the study was its lack of a uniform group of patients with all the office, survey, complications, and radiographic data. Our retrospective study design made it difficult to obtain such a group without significantly reducing the sample size, so we divided patients into 4 data groups. A third potential weakness was the study’s variable method for collecting complications data. Rates of complications in the 178 shoulders were calculated from either office evaluation or patient self-report by mail or telephone. This data collection method is subject to recall bias, but mail and telephone contact was needed so the study would capture the large number of patients who had traveled to our institution for their surgery or had since moved away. Fourth, belly-press and lift-off tests were used in part to assess subscapularis function, but recent literature suggests post-TSA subscapularis assessment can be unreliable.38 These tests may be positive in up to two-thirds of patients after 2 years.39 Fifth, the generalizability of our findings to diagnoses such as rheumatoid and posttraumatic arthritis is limited. We had to restrict the study to patients with primary glenohumeral arthritis in order to minimize confounders.

This study’s main strength is its description of the clinical and radiographic outcomes of using a single prosthetic system in operations performed by a single surgeon in a large number of patients. This was the first and largest study evaluating the clinical and radiographic outcomes of this hybrid glenoid implant. Excluding patients with nonprimary arthritis allowed us to minimize potential confounding factors that affect patient outcomes. In conclusion, our study results showed the favorable clinical and radiographic outcomes of TSAs that have a hybrid glenoid component with dual radii of curvature. At a mean of 3.7 years after surgery, 63% of patients had no glenoid lucencies, and, at a mean of 4.8 years, only 1.7% of patients required revision. We continue to follow these patients to obtain long-term results of this innovative prosthesis.

1. Rodosky MW, Bigliani LU. Indications for glenoid resurfacing in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(3):231-248.

2. Boyd AD Jr, Thomas WH, Scott RD, Sledge CB, Thornhill TS. Total shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty. Indications for glenoid resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5(4):329-336.

3. Torchia ME, Cofield RH, Settergren CR. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis: long-term results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(6):495-505.

4. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(2):251-258.

5. Cofield RH. Degenerative and arthritic problems of the glenohumeral joint. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, eds. The Shoulder. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1990:740-745.

6. Neer CS 2nd, Watson KC, Stanton FJ. Recent experience in total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(3):319-337.

7. Cofield RH. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(6):899-906.

8. Karduna AR, Williams GR, Williams JL, Iannotti JP. Kinematics of the glenohumeral joint: influences of muscle forces, ligamentous constraints, and articular geometry. J Orthop Res. 1996;14(6):986-993.

9. Karduna AR, Williams GR, Iannotti JP, Williams JL. Total shoulder arthroplasty biomechanics: a study of the forces and strains at the glenoid component. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120(1):92-99.

10. Karduna AR, Williams GR, Williams JL, Iannotti JP. Glenohumeral joint translations before and after total shoulder arthroplasty. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(8):1166-1174.

11. Matsen FA 3rd, Clinton J, Lynch J, Bertelsen A, Richardson ML. Glenoid component failure in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(4):885-896.

12. Franklin JL, Barrett WP, Jackins SE, Matsen FA 3rd. Glenoid loosening in total shoulder arthroplasty. Association with rotator cuff deficiency. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3(1):39-46.

13. Barrett WP, Franklin JL, Jackins SE, Wyss CR, Matsen FA 3rd. Total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(6):865-872.

14. Harryman DT, Sidles JA, Harris SL, Lippitt SB, Matsen FA 3rd. The effect of articular conformity and the size of the humeral head component on laxity and motion after glenohumeral arthroplasty. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(4):555-563.

15. Flatow EL. Prosthetic design considerations in total shoulder arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplasty. 1995;6(4):233-244.

16. Klimkiewicz JJ, Iannotti JP, Rubash HE, Shanbhag AS. Aseptic loosening of the humeral component in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(4):422-426.

17. Wang VM, Krishnan R, Ugwonali OF, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU, Ateshian GA. Biomechanical evaluation of a novel glenoid design in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 suppl S):129S-140S.

18. Neer CS 2nd. Replacement arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56(1):1-13.

19. Boorman RS, Kopjar B, Fehringer E, Churchill RS, Smith K, Matsen FA 3rd. The effect of total shoulder arthroplasty on self-assessed health status is comparable to that of total hip arthroplasty and coronary artery bypass grafting. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(2):158-163.

20. Patel AA, Donegan D, Albert T. The 36-Item Short Form. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(2):126-134.

21. Richards RR, An KN, Bigliani LU, et al. A standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(6):347-352.

22. Wright RW, Baumgarten KM. Shoulder outcomes measures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(7):436-444.

23. Lazarus MD, Jensen KL, Southworth C, Matsen FA 3rd. The radiographic evaluation of keeled and pegged glenoid component insertion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(7):1174-1182.

24. Sperling JW, Cofield RH, O’Driscoll SW, Torchia ME, Rowland CM. Radiographic assessment of ingrowth total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(6):507-513.

25. Dinse GE, Lagakos SW. Nonparametric estimation of lifetime and disease onset distributions from incomplete observations. Biometrics. 1982;38(4):921-932.

26. Baumgarten KM, Lashgari CJ, Yamaguchi K. Glenoid resurfacing in shoulder arthroplasty: indications and contraindications. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:3-11.

27. Bohsali KI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2279-2292.

28. Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Complications of total shoulder-replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(4):603-616.

29. Poppen NK, Walker PS. Normal and abnormal motion of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(2):195-201.

30. Cotton RE, Rideout DF. Tears of the humeral rotator cuff; a radiological and pathological necropsy survey. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:314-328.

31. Bigliani LU, Kelkar R, Flatow EL, Pollock RG, Mow VC. Glenohumeral stability. Biomechanical properties of passive and active stabilizers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):13-30.

32. Wang VM, Sugalski MT, Levine WN, Pawluk RJ, Mow VC, Bigliani LU. Comparison of glenohumeral mechanics following a capsular shift and anterior tightening. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1312-1322.

33. Young A, Walch G, Boileau P, et al. A multicentre study of the long-term results of using a flat-back polyethylene glenoid component in shoulder replacement for primary osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(2):210-216.

34. Khan A, Bunker TD, Kitson JB. Clinical and radiological follow-up of the Aequalis third-generation cemented total shoulder replacement: a minimum ten-year study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(12):1594-1600.

35. Walch G, Edwards TB, Boulahia A, Boileau P, Mole D, Adeleine P. The influence of glenohumeral prosthetic mismatch on glenoid radiolucent lines: results of a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(12):2186-2191.

36. Bartelt R, Sperling JW, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged fifty-five years or younger with osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):123-130.

37. Miller BS, Joseph TA, Noonan TJ, Horan MP, Hawkins RJ. Rupture of the subscapularis tendon after shoulder arthroplasty: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):492-496.

38. Armstrong A, Lashgari C, Teefey S, Menendez J, Yamaguchi K, Galatz LM. Ultrasound evaluation and clinical correlation of subscapularis repair after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):541-548.

39. Miller SL, Hazrati Y, Klepps S, Chiang A, Flatow EL. Loss of subscapularis function after total shoulder replacement: a seldom recognized problem. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(1):29-34.

Take-Home Points

- The authors have developed a total shoulder glenoid prosthesis that conforms with the humeral head in its center and is nonconforming on its peripheral edge.

- All clinical survey and range of motion parameters demonstrated statistically significant improvements at final follow-up.

- Only 3 shoulders (1.7%) required revision surgery.

- Eighty-six (63%) of 136 shoulders demonstrated no radiographic evidence of glenoid loosening.

- This is the first and largest study that evaluates the clinical and radiographic outcomes of this hybrid shoulder prosthesis.

Fixation of the glenoid component is the limiting factor in modern total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Glenoid loosening, the most common long-term complication, necessitates revision in up to 12% of patients.1-4 By contrast, humeral component loosening is relatively uncommon, affecting as few as 0.34% of patients.5 Multiple long-term studies have found consistently high rates (45%-93%) of radiolucencies around the glenoid component.3,6,7 Although their clinical significance has been debated, radiolucencies around the glenoid component raise concern about progressive loss of fixation.

Since TSA was introduced in the 1970s, complications with the glenoid component have been addressed with 2 different designs: conforming (congruent) and nonconforming. In a congruent articulation, the radii of curvature of the glenoid and humeral head components are identical, whereas they differ in a nonconforming model. Joint conformity is inversely related to glenohumeral translation.8 Neer’s original TSA was made congruent in order to limit translation and maximize the contact area. However, this design results in edge loading and a so-called rocking-horse phenomenon, which may lead to glenoid loosening.9-13 Surgeons therefore have increasingly turned to nonconforming implants. In the nonconforming design, the radius of curvature of the humeral head is smaller than that of the glenoid. Although this design may reduce edge loading,14 it allows more translation and reduces the relative contact area of the glenohumeral joint. As a result, more contact stress is transmitted to the glenoid component, leading to polyethylene deformation and wear.15,16

Dual radii of curvature are designed to augment joint stability without increasing component wear. Biomechanical data have indicated that edge loading is not increased by having a central conforming region added to a nonconforming model.17 The clinical value of this prosthesis, however, has not been determined. Therefore, we conducted a study to describe the intermediate-term clinical and radiographic outcomes of TSAs that use a novel hybrid glenoid component.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved (protocol AAAD3473) by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University and was conducted in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations.

Patient Selection

At Columbia University Medical Center, Dr. Bigliani performed 196 TSAs with a hybrid glenoid component (Bigliani-Flatow; Zimmer Biomet) in 169 patients between September 1998 and November 2007. All patients had received a diagnosis of primary glenohumeral arthritis as defined by Neer.18 Patients with previous surgery such as rotator cuff repair or subacromial decompression were included in our review, and patients with a nonprimary form of arthritis, such as rheumatoid, posttraumatic, or post-capsulorrhaphy arthritis, were excluded.

Operative Technique

For all surgeries, Dr. Bigliani performed a subscapularis tenotomy with regional anesthesia and a standard deltopectoral approach. A partial anterior capsulectomy was performed to increase the glenoid’s visibility. The inferior labrum was removed with a needle-tip bovie while the axillary nerve was being protected with a metal finger or narrow Darrach retractor. After reaming and trialing, the final glenoid component was cemented into place. Cement was placed only in the peg or keel holes and pressurized twice before final implantation. Of the 196 glenoid components, 168 (86%) were pegged and 28 (14%) keeled; in addition,190 of these components were all-polyethylene, whereas 6 had trabecular-metal backing. All glenoid components incorporated the hybrid design of dual radii of curvature. After the glenoid was cemented, the final humeral component was placed in 30° of retroversion. Whenever posterior wear was found, retroversion was reduced by 5° to 10°. The humeral prosthesis was cemented in cases (104/196, 53%) of poor bone quality or a large canal.

After surgery, the patient’s sling was fitted with an abduction pillow and a swathe, to be worn the first 24 hours, and the arm was passively ranged. Patients typically were discharged on postoperative day 2. Then, for 2 weeks, they followed an assisted passive range of motion (ROM) protocol, with limited external rotation, for promotion of subscapularis healing.

Clinical Outcomes

Dr. Bigliani assessed preoperative ROM in all planes. During initial evaluation, patients completed a questionnaire that consisted of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey19,20 (SF-36) and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons21 (ASES) and Simple Shoulder Test22 (SST) surveys. Postoperative clinical data were collected from office follow-up visits, survey questionnaires, or both. Postoperative office data included ROM, subscapularis integrity testing (belly-press or lift-off), and any complications. Patients with <1 year of office follow-up were excluded. In addition, the same survey questionnaire that was used before surgery was mailed to all patients after surgery; then, for anyone who did not respond by mail, we attempted contact by telephone. Neer criteria were based on patients’ subjective assessment of each arm on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = very satisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = dissatisfied). Patients were also asked about any specific complications or revision operations since their index procedure.

Physical examination and office follow-up data were obtained for 129 patients (148/196 shoulders, 76% follow-up) at a mean of 3.7 years (range 1.0-10.2 years) after surgery. Surveys were completed by 117 patients (139/196 shoulders, 71% follow-up) at a mean of 5.1 years (range, 1.6-11.2 years) after surgery. Only 15 patients had neither 1 year of office follow-up nor a completed questionnaire. The remaining 154 patients (178/196 shoulders, 91% follow-up) had clinical follow-up with office, mail, or telephone questionnaire at a mean of 4.8 years (range, 1.0-11.2 years) after surgery. This cohort of patients was used to determine rates of surgical revisions, subscapularis tears, dislocations, and other complications.

Radiographic Outcomes

Patients were included in the radiographic analysis if they had a shoulder radiograph at least 1 year after surgery. One hundred nineteen patients (136/196 shoulders, 69% follow-up) had radiographic follow-up at a mean of 3.7 years (range, 1.0-9.4 years) after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata Version 10.0. Paired t tests were used to compare preoperative and postoperative numerical data, including ROM and survey scores. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and set statistical significance at P < .05. For qualitative measures, the Fisher exact test was used. Survivorship analysis was performed according to the Kaplan-Meier method, with right-censored data for no event or missing data.25

Results

Clinical Analysis of Demographics

In demographics, the clinical and radiographic patient subgroups were similar to each other and to the overall study population (Table 2). Of 196 patients overall, 16 (8%) had a concomitant rotator cuff repair, and 27 (14%) underwent staged bilateral shoulder arthroplasties.

Clinical Analysis of ROM and Survey Scores

Operative shoulder ROM in forward elevation, external rotation at side, external rotation in abduction, and internal rotation all showed statistically significant (P < .001) improvement from before surgery to after surgery. Over 3.7 years, mean (SD) forward elevation improved from 107.3° (34.8°) to 159.0° (29.4°), external rotation at side improved from 20.4° (16.7°) to 49.4° (11.3°), and external rotation in abduction improved from 53.7° (24.3°) to 84.7° (9.1°). Internal rotation improved from a mean (SD) vertebral level of S1 (6.0 levels) to T9 (3.7 levels).

All validated survey scores also showed statistically significant (P < .001) improvement from before surgery to after surgery. Over 5.1 years, mean (SD) SF-36 scores improved from 64.9 (13.4) to 73.6 (17.1), ASES scores improved from 41.1 (22.5) to 82.7 (17.7), SST scores improved from 3.9 (2.8) to 9.7 (2.2), and visual analog scale pain scores improved from 5.6 (3.2) to 1.4 (2.1). Of 139 patients with follow-up, 130 (93.5%) were either satisfied or very satisfied with their TSA, and only 119 (86%) were either satisfied or very satisfied with the nonoperative shoulder.

Clinical Analysis of Postoperative Complications

Of the 178 shoulders evaluated for complications, 3 (1.7%) underwent revision surgery. Mean time to revision was 2.3 years (range, 1.5-3.9 years). Two revisions involved the glenoid component, and the third involved the humerus. In one of the glenoid cases, a 77-year-old woman fell and sustained a fracture at the base of the trabecular metal glenoid pegs; her component was revised to an all-polyethylene component, and she had no further complications. In the other glenoid case, a 73-year-old man’s all-polyethylene component loosened after 2 years and was revised to a trabecular metal implant, which loosened as well and was later converted to a hemiarthroplasty. In the humeral case, a 33-year-old man had his 4-year-old index TSA revised to a cemented stem and had no further complications.

Table 4 compares the clinical and radiographic outcomes of patients who required subscapularis repair, capsular shift, or implant revision with the outcomes of all other study patients, and Figure 3 shows Kaplan-Meier survivorship.

Postoperative Radiographic Analysis

Glenoid Component. At a mean of 3.7 years (minimum, 1 year) after surgery, 86 (63%) of 136 radiographically evaluated shoulders showed no glenoid lucencies; the other 50 (37%) showed ≥1 lucency. Of the 136 shoulders, 33 (24%) had a Lazarus score of 1, 15 (11%) had a score of 2, and only 2 (2%) had a score of 3. None of the shoulders had a score of 4 or 5.

Humeral Component. Of the 136 shoulders, 91 (67%) showed no lucencies in any of the 8 humeral stem zones; the other 45 (33%) showed 1 to 3 lucencies. Thirty (22%) of the 136 shoulders had 1 stem lucency zone, 8 (6%) had 2, and 3 (2%) had 3. None of the shoulders had >3 periprosthetic zones with lucent lines.

Discussion

In this article, we describe a hybrid glenoid TSA component with dual radii of curvature. Its central portion is congruent with the humeral head, and its peripheral portion is noncongruent and larger. The most significant finding of our study is the low rate (1.1%) of glenoid component revision 4.8 years after surgery. This rate is the lowest that has been reported in a study of ≥100 patients. Overall implant survival appeared as an almost flat Kaplan-Meir curve. We attribute this low revision rate to improved biomechanics with the hybrid glenoid design.

Symptomatic glenoid component loosening is the most common TSA complication.1,26-28 In a review of 73 Neer TSAs, Cofield7 found glenoid radiolucencies in 71% of patients 3.8 years after surgery. Radiographic evidence of loosening, defined as component migration, or tilt, or a circumferential lucency 1.5 mm thick, was present in another 11% of patients, and 4.1% developed symptomatic loosening that required glenoid revision. In a study with 12.2-year follow-up, Torchia and colleagues3 found rates of 84% for glenoid radiolucencies, 44% for radiographic loosening, and 5.6% for symptomatic loosening that required revision. In a systematic review of studies with follow-up of ≥10 years, Bohsali and colleagues27 found similar lucency and radiographic loosening rates and a 7% glenoid revision rate. These data suggest glenoid radiolucencies may progress to component loosening.

Degree of joint congruence is a key factor in glenoid loosening. Neer’s congruent design increases the contact area with concentric loading and reduces glenohumeral translation, which leads to reduced polyethylene wear and improved joint stability. In extreme arm positions, however, humeral head subluxation results in edge loading and a glenoid rocking-horse effect.9-13,17,29-31 Conversely, nonconforming implants allow increased glenohumeral translation without edge loading,14 though they also reduce the relative glenohumeral contact area and thus transmit more contact stress to the glenoid.16,17 A hybrid glenoid component with central conforming and peripheral nonconforming zones may reduce the rocking-horse effect while maximizing ROM and joint stability. Wang and colleagues32 studied the biomechanical properties of this glenoid design and found that the addition of a central conforming region did not increase edge loading.

Additional results from our study support the efficacy of a hybrid glenoid component. Patients’ clinical outcomes improved significantly. At 5.1 years after surgery, 93.5% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with their procedure and reported less satisfaction (86%) with the nonoperative shoulder. Also significant was the reduced number of radiolucencies. At 3.7 years after surgery, the overall percentage of shoulders with ≥1 glenoid radiolucency was 37%, considerably lower than the 82% reported by Cofield7 and the rates in more recent studies.3,16,33-36 Of the 178 shoulders in our study, 10 (5.6%) had subscapularis tears, and 6 (3.4%) of 178 had these tears surgically repaired. This 3.4% compares favorably with the 5.9% (of 119 patients) found by Miller and colleagues37 28 months after surgery. Of our 178 shoulders, 27 (15.2%) had clinically significant postoperative complications; 18 (10.1%) of the 178 had these complications surgically treated, and 9 (5.1%) had them managed nonoperatively. Bohsali and colleagues27 systematically reviewed 33 TSA studies and found a slightly higher complication rate (16.3%) 5.3 years after surgery. Furthermore, in our study, the 11 patients who underwent revision, capsular shift, or subscapularis repair had final outcomes comparable to those of the rest of our study population.

Our study had several potential weaknesses. First, its minimum clinical and radiographic follow-up was 1 year, whereas most long-term TSA series set a minimum of 2 years. We used 1 year because this was the first clinical study of the hybrid glenoid component design, and we wanted to maximize its sample size by reporting on intermediate-length outcomes. Even so, 93% (166/178) of our clinical patients and 83% (113/136) of our radiographic patients have had ≥2 years of follow-up, and we continue to follow all study patients for long-term outcomes. Another weakness of the study was its lack of a uniform group of patients with all the office, survey, complications, and radiographic data. Our retrospective study design made it difficult to obtain such a group without significantly reducing the sample size, so we divided patients into 4 data groups. A third potential weakness was the study’s variable method for collecting complications data. Rates of complications in the 178 shoulders were calculated from either office evaluation or patient self-report by mail or telephone. This data collection method is subject to recall bias, but mail and telephone contact was needed so the study would capture the large number of patients who had traveled to our institution for their surgery or had since moved away. Fourth, belly-press and lift-off tests were used in part to assess subscapularis function, but recent literature suggests post-TSA subscapularis assessment can be unreliable.38 These tests may be positive in up to two-thirds of patients after 2 years.39 Fifth, the generalizability of our findings to diagnoses such as rheumatoid and posttraumatic arthritis is limited. We had to restrict the study to patients with primary glenohumeral arthritis in order to minimize confounders.

This study’s main strength is its description of the clinical and radiographic outcomes of using a single prosthetic system in operations performed by a single surgeon in a large number of patients. This was the first and largest study evaluating the clinical and radiographic outcomes of this hybrid glenoid implant. Excluding patients with nonprimary arthritis allowed us to minimize potential confounding factors that affect patient outcomes. In conclusion, our study results showed the favorable clinical and radiographic outcomes of TSAs that have a hybrid glenoid component with dual radii of curvature. At a mean of 3.7 years after surgery, 63% of patients had no glenoid lucencies, and, at a mean of 4.8 years, only 1.7% of patients required revision. We continue to follow these patients to obtain long-term results of this innovative prosthesis.

Take-Home Points

- The authors have developed a total shoulder glenoid prosthesis that conforms with the humeral head in its center and is nonconforming on its peripheral edge.

- All clinical survey and range of motion parameters demonstrated statistically significant improvements at final follow-up.

- Only 3 shoulders (1.7%) required revision surgery.

- Eighty-six (63%) of 136 shoulders demonstrated no radiographic evidence of glenoid loosening.

- This is the first and largest study that evaluates the clinical and radiographic outcomes of this hybrid shoulder prosthesis.

Fixation of the glenoid component is the limiting factor in modern total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Glenoid loosening, the most common long-term complication, necessitates revision in up to 12% of patients.1-4 By contrast, humeral component loosening is relatively uncommon, affecting as few as 0.34% of patients.5 Multiple long-term studies have found consistently high rates (45%-93%) of radiolucencies around the glenoid component.3,6,7 Although their clinical significance has been debated, radiolucencies around the glenoid component raise concern about progressive loss of fixation.

Since TSA was introduced in the 1970s, complications with the glenoid component have been addressed with 2 different designs: conforming (congruent) and nonconforming. In a congruent articulation, the radii of curvature of the glenoid and humeral head components are identical, whereas they differ in a nonconforming model. Joint conformity is inversely related to glenohumeral translation.8 Neer’s original TSA was made congruent in order to limit translation and maximize the contact area. However, this design results in edge loading and a so-called rocking-horse phenomenon, which may lead to glenoid loosening.9-13 Surgeons therefore have increasingly turned to nonconforming implants. In the nonconforming design, the radius of curvature of the humeral head is smaller than that of the glenoid. Although this design may reduce edge loading,14 it allows more translation and reduces the relative contact area of the glenohumeral joint. As a result, more contact stress is transmitted to the glenoid component, leading to polyethylene deformation and wear.15,16

Dual radii of curvature are designed to augment joint stability without increasing component wear. Biomechanical data have indicated that edge loading is not increased by having a central conforming region added to a nonconforming model.17 The clinical value of this prosthesis, however, has not been determined. Therefore, we conducted a study to describe the intermediate-term clinical and radiographic outcomes of TSAs that use a novel hybrid glenoid component.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved (protocol AAAD3473) by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University and was conducted in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations.

Patient Selection

At Columbia University Medical Center, Dr. Bigliani performed 196 TSAs with a hybrid glenoid component (Bigliani-Flatow; Zimmer Biomet) in 169 patients between September 1998 and November 2007. All patients had received a diagnosis of primary glenohumeral arthritis as defined by Neer.18 Patients with previous surgery such as rotator cuff repair or subacromial decompression were included in our review, and patients with a nonprimary form of arthritis, such as rheumatoid, posttraumatic, or post-capsulorrhaphy arthritis, were excluded.

Operative Technique

For all surgeries, Dr. Bigliani performed a subscapularis tenotomy with regional anesthesia and a standard deltopectoral approach. A partial anterior capsulectomy was performed to increase the glenoid’s visibility. The inferior labrum was removed with a needle-tip bovie while the axillary nerve was being protected with a metal finger or narrow Darrach retractor. After reaming and trialing, the final glenoid component was cemented into place. Cement was placed only in the peg or keel holes and pressurized twice before final implantation. Of the 196 glenoid components, 168 (86%) were pegged and 28 (14%) keeled; in addition,190 of these components were all-polyethylene, whereas 6 had trabecular-metal backing. All glenoid components incorporated the hybrid design of dual radii of curvature. After the glenoid was cemented, the final humeral component was placed in 30° of retroversion. Whenever posterior wear was found, retroversion was reduced by 5° to 10°. The humeral prosthesis was cemented in cases (104/196, 53%) of poor bone quality or a large canal.

After surgery, the patient’s sling was fitted with an abduction pillow and a swathe, to be worn the first 24 hours, and the arm was passively ranged. Patients typically were discharged on postoperative day 2. Then, for 2 weeks, they followed an assisted passive range of motion (ROM) protocol, with limited external rotation, for promotion of subscapularis healing.

Clinical Outcomes

Dr. Bigliani assessed preoperative ROM in all planes. During initial evaluation, patients completed a questionnaire that consisted of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey19,20 (SF-36) and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons21 (ASES) and Simple Shoulder Test22 (SST) surveys. Postoperative clinical data were collected from office follow-up visits, survey questionnaires, or both. Postoperative office data included ROM, subscapularis integrity testing (belly-press or lift-off), and any complications. Patients with <1 year of office follow-up were excluded. In addition, the same survey questionnaire that was used before surgery was mailed to all patients after surgery; then, for anyone who did not respond by mail, we attempted contact by telephone. Neer criteria were based on patients’ subjective assessment of each arm on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = very satisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = dissatisfied). Patients were also asked about any specific complications or revision operations since their index procedure.

Physical examination and office follow-up data were obtained for 129 patients (148/196 shoulders, 76% follow-up) at a mean of 3.7 years (range 1.0-10.2 years) after surgery. Surveys were completed by 117 patients (139/196 shoulders, 71% follow-up) at a mean of 5.1 years (range, 1.6-11.2 years) after surgery. Only 15 patients had neither 1 year of office follow-up nor a completed questionnaire. The remaining 154 patients (178/196 shoulders, 91% follow-up) had clinical follow-up with office, mail, or telephone questionnaire at a mean of 4.8 years (range, 1.0-11.2 years) after surgery. This cohort of patients was used to determine rates of surgical revisions, subscapularis tears, dislocations, and other complications.

Radiographic Outcomes

Patients were included in the radiographic analysis if they had a shoulder radiograph at least 1 year after surgery. One hundred nineteen patients (136/196 shoulders, 69% follow-up) had radiographic follow-up at a mean of 3.7 years (range, 1.0-9.4 years) after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Stata Version 10.0. Paired t tests were used to compare preoperative and postoperative numerical data, including ROM and survey scores. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and set statistical significance at P < .05. For qualitative measures, the Fisher exact test was used. Survivorship analysis was performed according to the Kaplan-Meier method, with right-censored data for no event or missing data.25

Results

Clinical Analysis of Demographics

In demographics, the clinical and radiographic patient subgroups were similar to each other and to the overall study population (Table 2). Of 196 patients overall, 16 (8%) had a concomitant rotator cuff repair, and 27 (14%) underwent staged bilateral shoulder arthroplasties.

Clinical Analysis of ROM and Survey Scores

Operative shoulder ROM in forward elevation, external rotation at side, external rotation in abduction, and internal rotation all showed statistically significant (P < .001) improvement from before surgery to after surgery. Over 3.7 years, mean (SD) forward elevation improved from 107.3° (34.8°) to 159.0° (29.4°), external rotation at side improved from 20.4° (16.7°) to 49.4° (11.3°), and external rotation in abduction improved from 53.7° (24.3°) to 84.7° (9.1°). Internal rotation improved from a mean (SD) vertebral level of S1 (6.0 levels) to T9 (3.7 levels).

All validated survey scores also showed statistically significant (P < .001) improvement from before surgery to after surgery. Over 5.1 years, mean (SD) SF-36 scores improved from 64.9 (13.4) to 73.6 (17.1), ASES scores improved from 41.1 (22.5) to 82.7 (17.7), SST scores improved from 3.9 (2.8) to 9.7 (2.2), and visual analog scale pain scores improved from 5.6 (3.2) to 1.4 (2.1). Of 139 patients with follow-up, 130 (93.5%) were either satisfied or very satisfied with their TSA, and only 119 (86%) were either satisfied or very satisfied with the nonoperative shoulder.

Clinical Analysis of Postoperative Complications

Of the 178 shoulders evaluated for complications, 3 (1.7%) underwent revision surgery. Mean time to revision was 2.3 years (range, 1.5-3.9 years). Two revisions involved the glenoid component, and the third involved the humerus. In one of the glenoid cases, a 77-year-old woman fell and sustained a fracture at the base of the trabecular metal glenoid pegs; her component was revised to an all-polyethylene component, and she had no further complications. In the other glenoid case, a 73-year-old man’s all-polyethylene component loosened after 2 years and was revised to a trabecular metal implant, which loosened as well and was later converted to a hemiarthroplasty. In the humeral case, a 33-year-old man had his 4-year-old index TSA revised to a cemented stem and had no further complications.

Table 4 compares the clinical and radiographic outcomes of patients who required subscapularis repair, capsular shift, or implant revision with the outcomes of all other study patients, and Figure 3 shows Kaplan-Meier survivorship.

Postoperative Radiographic Analysis

Glenoid Component. At a mean of 3.7 years (minimum, 1 year) after surgery, 86 (63%) of 136 radiographically evaluated shoulders showed no glenoid lucencies; the other 50 (37%) showed ≥1 lucency. Of the 136 shoulders, 33 (24%) had a Lazarus score of 1, 15 (11%) had a score of 2, and only 2 (2%) had a score of 3. None of the shoulders had a score of 4 or 5.

Humeral Component. Of the 136 shoulders, 91 (67%) showed no lucencies in any of the 8 humeral stem zones; the other 45 (33%) showed 1 to 3 lucencies. Thirty (22%) of the 136 shoulders had 1 stem lucency zone, 8 (6%) had 2, and 3 (2%) had 3. None of the shoulders had >3 periprosthetic zones with lucent lines.

Discussion

In this article, we describe a hybrid glenoid TSA component with dual radii of curvature. Its central portion is congruent with the humeral head, and its peripheral portion is noncongruent and larger. The most significant finding of our study is the low rate (1.1%) of glenoid component revision 4.8 years after surgery. This rate is the lowest that has been reported in a study of ≥100 patients. Overall implant survival appeared as an almost flat Kaplan-Meir curve. We attribute this low revision rate to improved biomechanics with the hybrid glenoid design.

Symptomatic glenoid component loosening is the most common TSA complication.1,26-28 In a review of 73 Neer TSAs, Cofield7 found glenoid radiolucencies in 71% of patients 3.8 years after surgery. Radiographic evidence of loosening, defined as component migration, or tilt, or a circumferential lucency 1.5 mm thick, was present in another 11% of patients, and 4.1% developed symptomatic loosening that required glenoid revision. In a study with 12.2-year follow-up, Torchia and colleagues3 found rates of 84% for glenoid radiolucencies, 44% for radiographic loosening, and 5.6% for symptomatic loosening that required revision. In a systematic review of studies with follow-up of ≥10 years, Bohsali and colleagues27 found similar lucency and radiographic loosening rates and a 7% glenoid revision rate. These data suggest glenoid radiolucencies may progress to component loosening.

Degree of joint congruence is a key factor in glenoid loosening. Neer’s congruent design increases the contact area with concentric loading and reduces glenohumeral translation, which leads to reduced polyethylene wear and improved joint stability. In extreme arm positions, however, humeral head subluxation results in edge loading and a glenoid rocking-horse effect.9-13,17,29-31 Conversely, nonconforming implants allow increased glenohumeral translation without edge loading,14 though they also reduce the relative glenohumeral contact area and thus transmit more contact stress to the glenoid.16,17 A hybrid glenoid component with central conforming and peripheral nonconforming zones may reduce the rocking-horse effect while maximizing ROM and joint stability. Wang and colleagues32 studied the biomechanical properties of this glenoid design and found that the addition of a central conforming region did not increase edge loading.

Additional results from our study support the efficacy of a hybrid glenoid component. Patients’ clinical outcomes improved significantly. At 5.1 years after surgery, 93.5% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with their procedure and reported less satisfaction (86%) with the nonoperative shoulder. Also significant was the reduced number of radiolucencies. At 3.7 years after surgery, the overall percentage of shoulders with ≥1 glenoid radiolucency was 37%, considerably lower than the 82% reported by Cofield7 and the rates in more recent studies.3,16,33-36 Of the 178 shoulders in our study, 10 (5.6%) had subscapularis tears, and 6 (3.4%) of 178 had these tears surgically repaired. This 3.4% compares favorably with the 5.9% (of 119 patients) found by Miller and colleagues37 28 months after surgery. Of our 178 shoulders, 27 (15.2%) had clinically significant postoperative complications; 18 (10.1%) of the 178 had these complications surgically treated, and 9 (5.1%) had them managed nonoperatively. Bohsali and colleagues27 systematically reviewed 33 TSA studies and found a slightly higher complication rate (16.3%) 5.3 years after surgery. Furthermore, in our study, the 11 patients who underwent revision, capsular shift, or subscapularis repair had final outcomes comparable to those of the rest of our study population.

Our study had several potential weaknesses. First, its minimum clinical and radiographic follow-up was 1 year, whereas most long-term TSA series set a minimum of 2 years. We used 1 year because this was the first clinical study of the hybrid glenoid component design, and we wanted to maximize its sample size by reporting on intermediate-length outcomes. Even so, 93% (166/178) of our clinical patients and 83% (113/136) of our radiographic patients have had ≥2 years of follow-up, and we continue to follow all study patients for long-term outcomes. Another weakness of the study was its lack of a uniform group of patients with all the office, survey, complications, and radiographic data. Our retrospective study design made it difficult to obtain such a group without significantly reducing the sample size, so we divided patients into 4 data groups. A third potential weakness was the study’s variable method for collecting complications data. Rates of complications in the 178 shoulders were calculated from either office evaluation or patient self-report by mail or telephone. This data collection method is subject to recall bias, but mail and telephone contact was needed so the study would capture the large number of patients who had traveled to our institution for their surgery or had since moved away. Fourth, belly-press and lift-off tests were used in part to assess subscapularis function, but recent literature suggests post-TSA subscapularis assessment can be unreliable.38 These tests may be positive in up to two-thirds of patients after 2 years.39 Fifth, the generalizability of our findings to diagnoses such as rheumatoid and posttraumatic arthritis is limited. We had to restrict the study to patients with primary glenohumeral arthritis in order to minimize confounders.

This study’s main strength is its description of the clinical and radiographic outcomes of using a single prosthetic system in operations performed by a single surgeon in a large number of patients. This was the first and largest study evaluating the clinical and radiographic outcomes of this hybrid glenoid implant. Excluding patients with nonprimary arthritis allowed us to minimize potential confounding factors that affect patient outcomes. In conclusion, our study results showed the favorable clinical and radiographic outcomes of TSAs that have a hybrid glenoid component with dual radii of curvature. At a mean of 3.7 years after surgery, 63% of patients had no glenoid lucencies, and, at a mean of 4.8 years, only 1.7% of patients required revision. We continue to follow these patients to obtain long-term results of this innovative prosthesis.

1. Rodosky MW, Bigliani LU. Indications for glenoid resurfacing in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(3):231-248.

2. Boyd AD Jr, Thomas WH, Scott RD, Sledge CB, Thornhill TS. Total shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty. Indications for glenoid resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5(4):329-336.

3. Torchia ME, Cofield RH, Settergren CR. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis: long-term results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(6):495-505.

4. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(2):251-258.

5. Cofield RH. Degenerative and arthritic problems of the glenohumeral joint. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, eds. The Shoulder. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1990:740-745.

6. Neer CS 2nd, Watson KC, Stanton FJ. Recent experience in total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(3):319-337.

7. Cofield RH. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(6):899-906.

8. Karduna AR, Williams GR, Williams JL, Iannotti JP. Kinematics of the glenohumeral joint: influences of muscle forces, ligamentous constraints, and articular geometry. J Orthop Res. 1996;14(6):986-993.

9. Karduna AR, Williams GR, Iannotti JP, Williams JL. Total shoulder arthroplasty biomechanics: a study of the forces and strains at the glenoid component. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120(1):92-99.

10. Karduna AR, Williams GR, Williams JL, Iannotti JP. Glenohumeral joint translations before and after total shoulder arthroplasty. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(8):1166-1174.

11. Matsen FA 3rd, Clinton J, Lynch J, Bertelsen A, Richardson ML. Glenoid component failure in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(4):885-896.

12. Franklin JL, Barrett WP, Jackins SE, Matsen FA 3rd. Glenoid loosening in total shoulder arthroplasty. Association with rotator cuff deficiency. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3(1):39-46.

13. Barrett WP, Franklin JL, Jackins SE, Wyss CR, Matsen FA 3rd. Total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(6):865-872.

14. Harryman DT, Sidles JA, Harris SL, Lippitt SB, Matsen FA 3rd. The effect of articular conformity and the size of the humeral head component on laxity and motion after glenohumeral arthroplasty. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(4):555-563.

15. Flatow EL. Prosthetic design considerations in total shoulder arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplasty. 1995;6(4):233-244.

16. Klimkiewicz JJ, Iannotti JP, Rubash HE, Shanbhag AS. Aseptic loosening of the humeral component in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(4):422-426.

17. Wang VM, Krishnan R, Ugwonali OF, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU, Ateshian GA. Biomechanical evaluation of a novel glenoid design in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 suppl S):129S-140S.

18. Neer CS 2nd. Replacement arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56(1):1-13.

19. Boorman RS, Kopjar B, Fehringer E, Churchill RS, Smith K, Matsen FA 3rd. The effect of total shoulder arthroplasty on self-assessed health status is comparable to that of total hip arthroplasty and coronary artery bypass grafting. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(2):158-163.

20. Patel AA, Donegan D, Albert T. The 36-Item Short Form. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(2):126-134.

21. Richards RR, An KN, Bigliani LU, et al. A standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(6):347-352.

22. Wright RW, Baumgarten KM. Shoulder outcomes measures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(7):436-444.

23. Lazarus MD, Jensen KL, Southworth C, Matsen FA 3rd. The radiographic evaluation of keeled and pegged glenoid component insertion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(7):1174-1182.

24. Sperling JW, Cofield RH, O’Driscoll SW, Torchia ME, Rowland CM. Radiographic assessment of ingrowth total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(6):507-513.

25. Dinse GE, Lagakos SW. Nonparametric estimation of lifetime and disease onset distributions from incomplete observations. Biometrics. 1982;38(4):921-932.

26. Baumgarten KM, Lashgari CJ, Yamaguchi K. Glenoid resurfacing in shoulder arthroplasty: indications and contraindications. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:3-11.

27. Bohsali KI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2279-2292.

28. Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Complications of total shoulder-replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(4):603-616.

29. Poppen NK, Walker PS. Normal and abnormal motion of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(2):195-201.

30. Cotton RE, Rideout DF. Tears of the humeral rotator cuff; a radiological and pathological necropsy survey. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:314-328.

31. Bigliani LU, Kelkar R, Flatow EL, Pollock RG, Mow VC. Glenohumeral stability. Biomechanical properties of passive and active stabilizers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):13-30.

32. Wang VM, Sugalski MT, Levine WN, Pawluk RJ, Mow VC, Bigliani LU. Comparison of glenohumeral mechanics following a capsular shift and anterior tightening. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1312-1322.

33. Young A, Walch G, Boileau P, et al. A multicentre study of the long-term results of using a flat-back polyethylene glenoid component in shoulder replacement for primary osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(2):210-216.

34. Khan A, Bunker TD, Kitson JB. Clinical and radiological follow-up of the Aequalis third-generation cemented total shoulder replacement: a minimum ten-year study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(12):1594-1600.

35. Walch G, Edwards TB, Boulahia A, Boileau P, Mole D, Adeleine P. The influence of glenohumeral prosthetic mismatch on glenoid radiolucent lines: results of a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(12):2186-2191.

36. Bartelt R, Sperling JW, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged fifty-five years or younger with osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):123-130.

37. Miller BS, Joseph TA, Noonan TJ, Horan MP, Hawkins RJ. Rupture of the subscapularis tendon after shoulder arthroplasty: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):492-496.

38. Armstrong A, Lashgari C, Teefey S, Menendez J, Yamaguchi K, Galatz LM. Ultrasound evaluation and clinical correlation of subscapularis repair after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):541-548.

39. Miller SL, Hazrati Y, Klepps S, Chiang A, Flatow EL. Loss of subscapularis function after total shoulder replacement: a seldom recognized problem. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(1):29-34.

1. Rodosky MW, Bigliani LU. Indications for glenoid resurfacing in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(3):231-248.

2. Boyd AD Jr, Thomas WH, Scott RD, Sledge CB, Thornhill TS. Total shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty. Indications for glenoid resurfacing. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5(4):329-336.

3. Torchia ME, Cofield RH, Settergren CR. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis: long-term results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(6):495-505.

4. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(2):251-258.

5. Cofield RH. Degenerative and arthritic problems of the glenohumeral joint. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, eds. The Shoulder. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1990:740-745.

6. Neer CS 2nd, Watson KC, Stanton FJ. Recent experience in total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(3):319-337.

7. Cofield RH. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(6):899-906.

8. Karduna AR, Williams GR, Williams JL, Iannotti JP. Kinematics of the glenohumeral joint: influences of muscle forces, ligamentous constraints, and articular geometry. J Orthop Res. 1996;14(6):986-993.

9. Karduna AR, Williams GR, Iannotti JP, Williams JL. Total shoulder arthroplasty biomechanics: a study of the forces and strains at the glenoid component. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120(1):92-99.

10. Karduna AR, Williams GR, Williams JL, Iannotti JP. Glenohumeral joint translations before and after total shoulder arthroplasty. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(8):1166-1174.

11. Matsen FA 3rd, Clinton J, Lynch J, Bertelsen A, Richardson ML. Glenoid component failure in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(4):885-896.

12. Franklin JL, Barrett WP, Jackins SE, Matsen FA 3rd. Glenoid loosening in total shoulder arthroplasty. Association with rotator cuff deficiency. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3(1):39-46.

13. Barrett WP, Franklin JL, Jackins SE, Wyss CR, Matsen FA 3rd. Total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(6):865-872.

14. Harryman DT, Sidles JA, Harris SL, Lippitt SB, Matsen FA 3rd. The effect of articular conformity and the size of the humeral head component on laxity and motion after glenohumeral arthroplasty. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(4):555-563.

15. Flatow EL. Prosthetic design considerations in total shoulder arthroplasty. Semin Arthroplasty. 1995;6(4):233-244.

16. Klimkiewicz JJ, Iannotti JP, Rubash HE, Shanbhag AS. Aseptic loosening of the humeral component in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(4):422-426.

17. Wang VM, Krishnan R, Ugwonali OF, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU, Ateshian GA. Biomechanical evaluation of a novel glenoid design in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 suppl S):129S-140S.

18. Neer CS 2nd. Replacement arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56(1):1-13.

19. Boorman RS, Kopjar B, Fehringer E, Churchill RS, Smith K, Matsen FA 3rd. The effect of total shoulder arthroplasty on self-assessed health status is comparable to that of total hip arthroplasty and coronary artery bypass grafting. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(2):158-163.

20. Patel AA, Donegan D, Albert T. The 36-Item Short Form. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(2):126-134.

21. Richards RR, An KN, Bigliani LU, et al. A standardized method for the assessment of shoulder function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(6):347-352.

22. Wright RW, Baumgarten KM. Shoulder outcomes measures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(7):436-444.

23. Lazarus MD, Jensen KL, Southworth C, Matsen FA 3rd. The radiographic evaluation of keeled and pegged glenoid component insertion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(7):1174-1182.

24. Sperling JW, Cofield RH, O’Driscoll SW, Torchia ME, Rowland CM. Radiographic assessment of ingrowth total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(6):507-513.

25. Dinse GE, Lagakos SW. Nonparametric estimation of lifetime and disease onset distributions from incomplete observations. Biometrics. 1982;38(4):921-932.

26. Baumgarten KM, Lashgari CJ, Yamaguchi K. Glenoid resurfacing in shoulder arthroplasty: indications and contraindications. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:3-11.

27. Bohsali KI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Complications of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2279-2292.

28. Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Complications of total shoulder-replacement arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(4):603-616.

29. Poppen NK, Walker PS. Normal and abnormal motion of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58(2):195-201.

30. Cotton RE, Rideout DF. Tears of the humeral rotator cuff; a radiological and pathological necropsy survey. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:314-328.

31. Bigliani LU, Kelkar R, Flatow EL, Pollock RG, Mow VC. Glenohumeral stability. Biomechanical properties of passive and active stabilizers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):13-30.

32. Wang VM, Sugalski MT, Levine WN, Pawluk RJ, Mow VC, Bigliani LU. Comparison of glenohumeral mechanics following a capsular shift and anterior tightening. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(6):1312-1322.

33. Young A, Walch G, Boileau P, et al. A multicentre study of the long-term results of using a flat-back polyethylene glenoid component in shoulder replacement for primary osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(2):210-216.

34. Khan A, Bunker TD, Kitson JB. Clinical and radiological follow-up of the Aequalis third-generation cemented total shoulder replacement: a minimum ten-year study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(12):1594-1600.

35. Walch G, Edwards TB, Boulahia A, Boileau P, Mole D, Adeleine P. The influence of glenohumeral prosthetic mismatch on glenoid radiolucent lines: results of a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(12):2186-2191.

36. Bartelt R, Sperling JW, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged fifty-five years or younger with osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):123-130.

37. Miller BS, Joseph TA, Noonan TJ, Horan MP, Hawkins RJ. Rupture of the subscapularis tendon after shoulder arthroplasty: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):492-496.

38. Armstrong A, Lashgari C, Teefey S, Menendez J, Yamaguchi K, Galatz LM. Ultrasound evaluation and clinical correlation of subscapularis repair after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):541-548.

39. Miller SL, Hazrati Y, Klepps S, Chiang A, Flatow EL. Loss of subscapularis function after total shoulder replacement: a seldom recognized problem. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(1):29-34.

Immunization information systems show progress over recent years

From 2013 to 2016, all U.S. immunization information systems showed progress in bidirectional information exchange with EHRs, said Neil Murthy, MD, and his associates at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta.

Across all 55 jurisdictions in 49 states and six cities in the United States using immunization information systems (IIS), 106% of U.S. births were registered in IIS in 2016, which is an increase from 102% in 2013; percentages may exceed 100%, because a child who is born in one state but who lives in a different state might be recorded in both IISs.

Bidirectional exchange of data with EHRs is an important part of an IIS. In 2016, 91% of jurisdictions had an IIS that used a platform-independent messaging system that received vaccination histories from providers and returned acknowledgment messages, compared with 87% in 2013, the investigators said.

“Clinical Decision Support (CDS) functionalities enable providers to evaluate the validity of vaccine doses administered to patients and forecast future vaccines that will be needed, based on recommendations developed by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices,” Dr. Murthy and his associates said. In 2016, 58% of the 55 jurisdictions sent a vaccine forecast to another system, compared with 31% in 2013.

In 2016, 95% of the 55 jurisdictions gave a “predefined, automatic report on immunization coverage by provider site,” compared with 89% of jurisdictions in 2013.

“IISs are integral components of routine clinical practice and public health surveillance for immunization,” Dr. Murthy and his associates said. “Availability of more complete IIS data also offers many benefits to health care providers and public health practitioners, including consolidating patients’ vaccination histories, identifying undervaccinated subgroups, and forecasting the needs of individual patients for recommended vaccines.”

Read more in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2017 Nov 3;66[43]:1178-81).

From 2013 to 2016, all U.S. immunization information systems showed progress in bidirectional information exchange with EHRs, said Neil Murthy, MD, and his associates at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta.

Across all 55 jurisdictions in 49 states and six cities in the United States using immunization information systems (IIS), 106% of U.S. births were registered in IIS in 2016, which is an increase from 102% in 2013; percentages may exceed 100%, because a child who is born in one state but who lives in a different state might be recorded in both IISs.

Bidirectional exchange of data with EHRs is an important part of an IIS. In 2016, 91% of jurisdictions had an IIS that used a platform-independent messaging system that received vaccination histories from providers and returned acknowledgment messages, compared with 87% in 2013, the investigators said.

“Clinical Decision Support (CDS) functionalities enable providers to evaluate the validity of vaccine doses administered to patients and forecast future vaccines that will be needed, based on recommendations developed by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices,” Dr. Murthy and his associates said. In 2016, 58% of the 55 jurisdictions sent a vaccine forecast to another system, compared with 31% in 2013.

In 2016, 95% of the 55 jurisdictions gave a “predefined, automatic report on immunization coverage by provider site,” compared with 89% of jurisdictions in 2013.

“IISs are integral components of routine clinical practice and public health surveillance for immunization,” Dr. Murthy and his associates said. “Availability of more complete IIS data also offers many benefits to health care providers and public health practitioners, including consolidating patients’ vaccination histories, identifying undervaccinated subgroups, and forecasting the needs of individual patients for recommended vaccines.”

Read more in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2017 Nov 3;66[43]:1178-81).

From 2013 to 2016, all U.S. immunization information systems showed progress in bidirectional information exchange with EHRs, said Neil Murthy, MD, and his associates at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta.

Across all 55 jurisdictions in 49 states and six cities in the United States using immunization information systems (IIS), 106% of U.S. births were registered in IIS in 2016, which is an increase from 102% in 2013; percentages may exceed 100%, because a child who is born in one state but who lives in a different state might be recorded in both IISs.

Bidirectional exchange of data with EHRs is an important part of an IIS. In 2016, 91% of jurisdictions had an IIS that used a platform-independent messaging system that received vaccination histories from providers and returned acknowledgment messages, compared with 87% in 2013, the investigators said.

“Clinical Decision Support (CDS) functionalities enable providers to evaluate the validity of vaccine doses administered to patients and forecast future vaccines that will be needed, based on recommendations developed by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices,” Dr. Murthy and his associates said. In 2016, 58% of the 55 jurisdictions sent a vaccine forecast to another system, compared with 31% in 2013.

In 2016, 95% of the 55 jurisdictions gave a “predefined, automatic report on immunization coverage by provider site,” compared with 89% of jurisdictions in 2013.

“IISs are integral components of routine clinical practice and public health surveillance for immunization,” Dr. Murthy and his associates said. “Availability of more complete IIS data also offers many benefits to health care providers and public health practitioners, including consolidating patients’ vaccination histories, identifying undervaccinated subgroups, and forecasting the needs of individual patients for recommended vaccines.”

Read more in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2017 Nov 3;66[43]:1178-81).

FROM MMWR

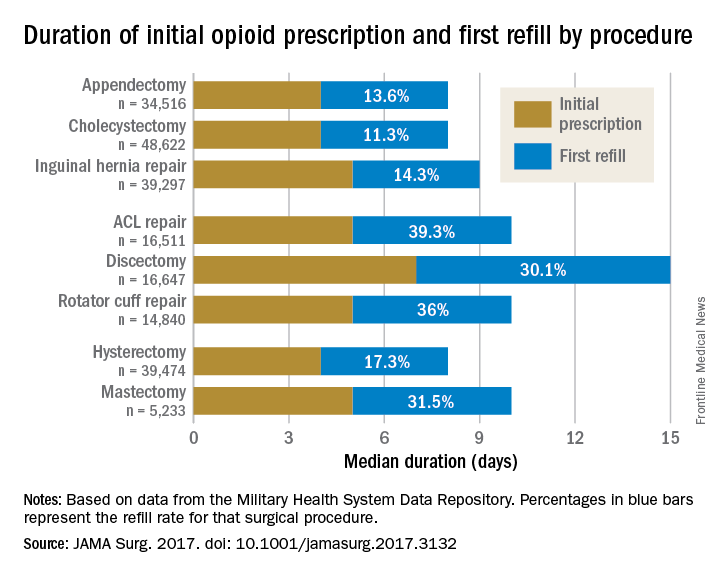

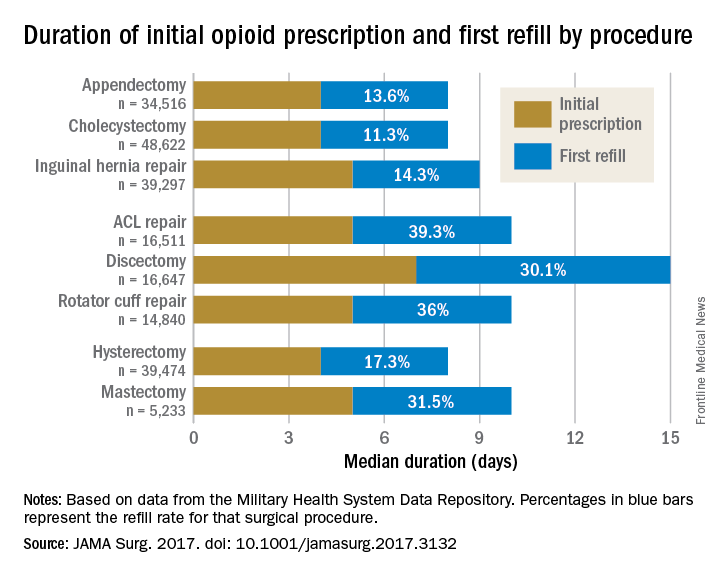

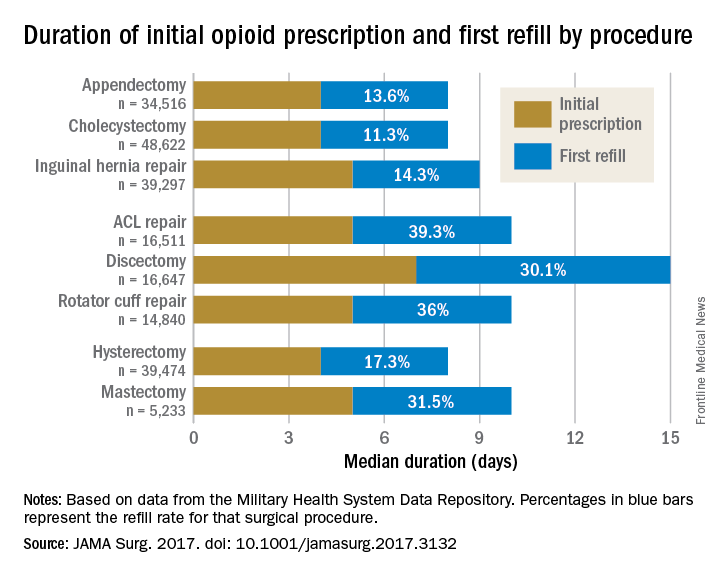

Seven days of opioids adequate for most hernia and other general surgery procedures

A 7-day limit on the initial opioid prescription may be sufficient for many common general surgery procedures, including hernia surgery and gynecologic procedures, findings of a large retrospective study suggest.