User login

Historical Patterns and Variation in Treatment of Injuries in NFL (National Football League) Players and NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) Division I Football Players

Among National Football League (NFL) and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) team physicians, there is no consensus on the management of various injuries. At national and regional meetings, the management of football injuries often is debated.

Given the high level of interest in the treatment of elite football players, we wanted to determine treatment patterns by surveying orthopedic team physicians. We conducted a study to determine the demographics of NFL and NCAA team physicians and to identify patterns and variations in the management of common injuries in these groups of elite football players.

Materials and Methods

The study was reviewed by an Institutional Review Board before data collection and was classified as exempt. The study population consisted of head orthopedic team physicians for NFL teams and NCAA Division I universities. The survey (Appendix),

Chi-square tests were used to determine significant differences between groups. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Responses were received from 31 (97%) of the 32 NFL and 111 (93%) of the 119 NCAA team physicians. The 2 groups’ surveys were identical with the exception of question 3, regarding NFL division or NCAA conference.

Team Physician Demographics

All survey respondents were the head orthopedic physicians for their teams. Seventy-one percent were the head team physicians as well; another 25% named a primary care physician as the head team physician. Thirty-nine percent of the NFL team physicians had been a team physician at the NFL level for more than 15 years, and 58% of the NCAA team physicians had been a team physician at the Division I level for more than 15 years. Eighty-one percent of NFL and 66% of NCAA team physicians had fellowship training in sports medicine. For away games, 10% of NFL vs 65% of NCAA teams traveled with 2 physicians; 90% of NFL and 28% of NCAA teams traveled with 3 or more physicians.

Only a small percentage of respondents (NFL, 10%; NCAA, 14%) indicated they had received advertising in exchange for services. Most respondents (NFL, 93%; NCAA, 89%) did not pay to provide team coverage. In contrast, 97% of NFL vs only 31% of NCAA physicians indicated they received a monetary stipend for providing orthopedic coverage.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructions

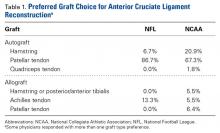

Eighty-seven percent of NFL and 67% of NCAA respondents indicated that patellar tendon autograft was their preferred graft choice (Table 1).

Anterior Shoulder Dislocations (Without Bony Bankart)

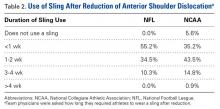

Sling use after reduction of anterior shoulder dislocation was varied, with most physicians using a sling 2 weeks or less (Table 2).

Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries

Roughly two-thirds of respondents (NFL, 60%; NCAA, 69%) indicated that, during a game, they managed acute acromioclavicular (AC) joint injuries (type I/II) with injection of a local anesthetic that allowed return to play. In addition, a majority (NFL, 90%; NCAA, 87%) indicated they gave such athletes pregame injections that allowed them to play. About half the physicians (NFL, 57%; NCAA, 52%) injected the AC joint with cortisone during the acute/subacute period (<1 month) to decrease inflammation.

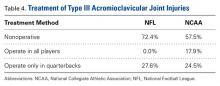

No significant difference was found between the 2 groups in terms of proportion of surgeons electing to treat type III AC joint injuries operatively versus nonoperatively (Table 4).

Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries

There was a significant (P < .0001) difference in use of prophylactic bracing for medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries (NFL, 28%; NCAA, 89%).

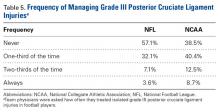

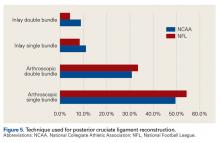

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries

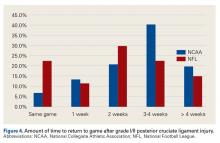

The percentage of physicians who allowed athletes to return to play after a grade I/II posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury was significantly (P = .01) higher in NFL physicians (22%) than in NCAA physicians (7%). The amount of time varied up to more than 4 weeks (Figure 4).

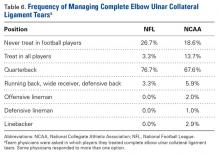

Elbow Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears

A majority of respondents indicated they would treat a complete elbow ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) tear in a quarterback; a much smaller percentage preferred operative repair in athletes playing other positions (Table 6).

Thumb Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears

For athletes with in-season thumb UCL tears, 63% of NFL and 54% of NCAA physicians indicated they cast the thumb and allowed return to play. Others recommended operative repair and either cast the thumb and allowed return to play (NFL, 30%; NCAA, 41%) or let the thumb heal before allowing return to play (NFL, 7%; NCAA, 5%).

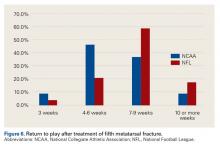

Fifth Metatarsal Fractures

For a large majority of physicians (NFL, 100%; NCAA, 94%), the preferred treatment for fifth metatarsal fractures was screw fixation.

Tibia Fractures

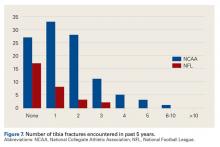

In the 5-year period before the survey, 43% of NFL and 75% of NCAA physicians managed at least one tibia fracture (P < .001) (Figure 7).

Ketorolac Injections

Intramuscular ketorolac injections were frequently given to elite football players, significantly (P < .01) more so in the NFL (93%) than in the NCAA (62%). The average number of injections varied among physicians, though a significantly (P < .0001) higher percentage of NFL (79%) than NCAA (13%) physicians gave 5 or more injections per game.

Discussion

This survey on managing common injuries in elite football players had an overall response rate of 94%. All NFL divisions and NCAA conferences were represented in physicians’ responses. Ninety percent of NFL and 65% of NCAA head team physicians were orthopedists. These findings differ from those of Stockard1 (1997), who surveyed athletic directors at Division I schools and reported 45% of head team physicians were family medicine-trained and 41% were orthopedists.

Given the high visibility of team coverage and the economics of college football’s highest division, one might expect team physicians to receive financial remuneration. This was not the case, according to our survey: Only 30% of physicians received a monetary stipend for team coverage, and only 14% received advertising in exchange for their services. Twelve NCAA team physicians indicated they pay to be allowed to provide team coverage.

Injury Management

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. For NFL and NCAA team physicians, the preferred graft choice for ACL reconstruction was patellar tendon autograft. This finding is similar to what Erickson and colleagues2 reported from a survey of NFL and NCAA team physicians: 86% of surgeons preferred bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) autograft. However, only 1 surgeon (0.7%) in that study, vs 16% in ours, preferred allograft. Allograft use may be somewhat controversial, as relevant data on competitive athletes are lacking, and it has been shown that the graft rupture rate3 is higher for BPTB allograft than for BPTB autograft in young patients. However, much of the data on higher failure rates with use of allograft in young patients4,5 has appeared since our data were collected.

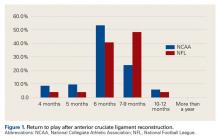

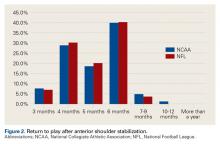

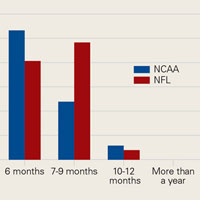

Our return-to-play data are similar to data from other studies.2,6 According to our survey, the most common length of time from ACL reconstruction to return to football was 6 months, and 94% of team physicians allowed return to football by 9 months. In the survey by Erickson and colleagues,2 55% of surgeons waited a minimum of 6 months before returning athletes to play, and only 12% waited at least 9 months. In the study by Bradley and colleagues6 (2002), 84% of surgeons waited at least 6 months before returning athletes to play. Of note, we found a significantly higher percentage of NCAA football players than NFL players returning within 6 months after surgery. The difference may be attributable to a more cautious approach being taken with NFL players, whereas most NCAA players are limited in the time remaining in their football careers and want to return to the playing field as soon as possible.

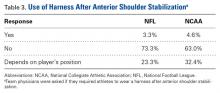

Shoulder Dislocations. Responses to the 5 survey questions on anterior shoulder dislocation showed little consensus with respect to management. The exception pertained to use of a harness for in-season return to play with a dislocation—92% of physicians preferred management with a harness. Of note, 7 of 10 team surgeons performed anterior stabilization through an arthroscopic approach. Despite historical recommendations to perform open anterior stabilization in collision athletes, NFL and NCAA physicians’ practice patterns have evolved.7 Although return to contact activity was varied among responses, 94% of physicians allowed return to contact within 6 months.

Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries. For college football players, AC joint injuries are the most common shoulder injuries.8 In the NFL Combine, the incidence of AC joint injuries was 15.7 per 100 players.8 Several studies have cited favorable results with nonoperative management of type III AC joint injuries.9-12 Nonoperative management was the preferred treatment in our study as well, yet 26% of surgeons still preferred operative treatment in quarterbacks. Opinions about operative repair of type III injuries in overhead athletes vary,13 but nonoperative management clearly is the preferred method for elite football players. A 2013 study by Lynch and colleagues14 found that only 2 of 40 NFL players with type III AC joint injuries underwent surgery.

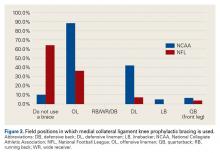

For type I and II AC joint injuries that occur during a game, more than two-thirds of the NCAA team physicians in our study favored injecting a local anesthetic to reduce pain and allow return to play in the same game. An even larger majority indicated they gave a pregame injection of an anesthetic to allow play. Similar use of injections for AC joint injuries has been reported in Australian-rules football and rugby.15Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries. Whether bracing is prophylactic against MCL injuries is controversial.16 Some studies have found it effective.17,18 According to our survey, 89% of Division I football teams used prophylactic knee bracing, mainly in offensive linemen but frequently in defensive linemen, too. No schools used bracing in athletes who played skill positions, except quarterbacks. Six schools used bracing on a quarterback’s front leg.

The percentage of teams that used prophylactic MCL bracing was significantly higher in the NCAA than in the NFL. NCAA team physicians generally have more control over players and therefore can implement widespread use of this bracing.

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. These injuries are infrequent. According to Parolie and Bergfeld,19 only 2% of college football players at the NFL Combine had a PCL injury. Treatment in athletes remains controversial. Our survey showed physicians’ willingness to return players to competition within 4 weeks after grade I/II PCL injuries. There is no consensus on management or on postinjury bracing. In operative cases, however, the preferred graft is allograft, and the preferred repair method is the arthroscopic single-bundle technique. These findings mirror those of a 2004 survey of the Herodicus Society by Dennis and colleagues.20 Elbow Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears. In throwing athletes with UCL tears, operative treatment has been recommended.21,22 A majority of our survey respondents preferred operative treatment for quarterbacks. However, operative treatment is still controversial, and quarterbacks differ from baseball players in their throwing motions and in the stresses acting on the UCLs during throwing. Two systematic reviews of UCL reconstruction have affirmed the positive outcomes of operative treatment in throwing athletes.21,22 However, most of the studies covered by these reviews focused on baseball players. In athletes playing positions other than quarterback, these injuries were typically treated nonoperatively.

Thumb Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears. Our survey respondents differed in their opinions on treating thumb UCL tears. About half recommended cast treatment, and the other half recommended operative treatment. Previous data suggest that delaying surgical treatment may be deleterious to the eventual outcome.23,24Fifth Metatarsal Fractures. For fifth metatarsal fractures, screw fixation was preferred by 90% of our survey respondents—vs 73% of NFL team physicians in a 2004 study by Low and colleagues.25 What remains controversial is the length of time before return to play. Our most frequent response was 4 to 6 weeks, and 46% of our respondents indicated they would wait 7 weeks or longer. These times differ significantly from what Low and colleagues25 reported: 86% of their physicians allowed return to competition after 6 to 12 weeks.

Tibia Fractures. Management of tibia fractures in US football players has not been reported. Chang and colleagues26 described 24 tibial shaft fractures in UK soccer players. Eleven fractures (~50%) were treated with intramedullary nails, 2 with plating, and 11 with conservative management. All players returned to activity, the operative group at 23.3 weeks and the nonoperative group at 27.6 weeks. Our respondents reported treating at least 150 tibial shaft fractures in the 5-year period before our survey, demonstrating the incidence and importance of this type of injury. A vast majority of team surgeons (96%) opted for treatment with intramedullary nailing. This choice may reflect an ability to return to play earlier—the ability to move the knee and maintain strength in the legs. Some have suggested it is important to remove the nail before the player returns to the football field, but this was not common practice among our groups of team surgeons. Other studies have not found any advantage to tibial nail removal.27Ketorolac Injections. Authors have described using ketorolac for the treatment of acute or pregame pain in professional football players.28-30 According to a 2000 survey, 93% of NFL teams used intramuscular ketorolac, and on average 15 players per team were treated, primarily on game day. Our survey found frequent use of ketorolac, with almost two-thirds of team orthopedists indicating pregame use. Ketorolac use was popular, particularly because of its effect in reducing postoperative pain and its potent effect in reducing pain on game day. However, injections by football team physicians have declined significantly in recent years, ever since an NFL Physician Society task force published recommendations on ketorolac use.31

Conclusion

There is a wide variety of patterns in treating athletes who play football at the highest levels of competition. Our findings can initiate further discussion on these topics and assist orthopedists providing game coverage at all levels of play in their decision-making process by helping to define the standard of care for their injured players.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E319-E327. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Stockard AR. Team physician preferences at National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I universities. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1997;97(2):89-95.

2. Erickson BJ, Harris JD, Fillingham YA, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction practice patterns by NFL and NCAA football team physicians. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):731-738.

3. Kraeutler MJ, Bravman JT, McCarty EC. Bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft versus allograft in outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a meta-analysis of 5182 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2439-2448.

4. Bottoni CR, Smith EL, Shaha J, et al. Autograft versus allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized clinical study with a minimum 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(10):2501-2509.

5. Sun K, Tian S, Zhang J, Xia C, Zhang C, Yu T. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with BPTB autograft, irradiated versus non-irradiated allograft: a prospective randomized clinical study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(5):464-474.

6. Bradley JP, Klimkiewicz JJ, Rytel MJ, Powell JW. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and current treatment trends among team physicians. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(5):502-509.

7. Rhee YG, Ha JH, Cho NS. Anterior shoulder stabilization in collision athletes: arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):979-985.

8. Brophy RH, Barnes R, Rodeo SA, Warren RF. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders at the NFL Combine—trends from 1987 to 2000. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(1):22-27.

9. Bishop JY, Kaeding C. Treatment of the acute traumatic acromioclavicular separation. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):237-245.

10. Mazzocca AD, Arciero RA, Bicos J. Evaluation and treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):316-329.

11. Schlegel TF, Burks RT, Marcus RL, Dunn HK. A prospective evaluation of untreated acute grade III acromioclavicular separations. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):699-703.

12. Spencer EE Jr. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular joint injuries: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(455):38-44.

13. Kraeutler MJ, Williams GR Jr, Cohen SB, et al. Inter- and intraobserver reliability of the radiographic diagnosis and treatment of acromioclavicular joint separations. Orthopedics. 2012;35(10):e1483-e1487.

14. Lynch TS, Saltzman MD, Ghodasra JH, Bilimoria KY, Bowen MK, Nuber GW. Acromioclavicular joint injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and management. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(12):2904-2908.

15. Orchard JW. Benefits and risks of using local anaesthetic for pain relief to allow early return to play in professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(3):209-213.

16. Salata MJ, Gibbs AE, Sekiya JK. The effectiveness of prophylactic knee bracing in American football: a systematic review. Sports Health. 2010;2(5):375-379.

17. Albright JP, Powell JW, Smith W, et al. Medial collateral ligament knee sprains in college football. Effectiveness of preventive braces. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):12-18.

18. Sitler M, Ryan J, Hopkinson W, et al. The efficacy of a prophylactic knee brace to reduce knee injuries in football. A prospective, randomized study at West Point. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(3):310-315.

19. Parolie JM, Bergfeld JA. Long-term results of nonoperative treatment of isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in the athlete. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14(1):35-38.

20. Dennis MG, Fox JA, Alford JW, Hayden JK, Bach BR Jr. Posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: current trends. J Knee Surg. 2004;17(3):133-139.

21. Purcell DB, Matava MJ, Wright RW. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(455):72-77.

22. Vitale MA, Ahmad CS. The outcome of elbow ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in overhead athletes: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1193-1205.

23. Fricker R, Hintermann B. Skier’s thumb. Treatment, prevention and recommendations. Sports Med. 1995;19(1):73-79.

24. Smith RJ. Post-traumatic instability of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(1):14-21.

25. Low K, Noblin JD, Browne JE, Barnthouse CD, Scott AR. Jones fractures in the elite football player. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2004;13(3):156-160.

26. Chang WR, Kapasi Z, Daisley S, Leach WJ. Tibial shaft fractures in football players. J Orthop Surg Res. 2007;2:11.

27. Karladani AH, Ericsson PA, Granhed H, Karlsson L, Nyberg P. Tibial intramedullary nails—should they be removed? A retrospective study of 71 patients. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(5):668-671.

28. Eichner ER. Intramuscular ketorolac injections: the pregame Toradol parade. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(4):169-170.

29. Nepple JJ, Matava MJ. Soft tissue injections in the athlete. Sports Health. 2009;1(5):396-404.

30. Powell ET, Tokish JM, Hawkins RJ. Toradol use in the athletic population. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002;1(4):191.

31. Matava M, Brater DC, Gritter N, et al. Recommendations of the National Football League physician society task force on the use of toradol® ketorolac in the National Football League. Sports Health. 2012;4(5):377-383.

Among National Football League (NFL) and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) team physicians, there is no consensus on the management of various injuries. At national and regional meetings, the management of football injuries often is debated.

Given the high level of interest in the treatment of elite football players, we wanted to determine treatment patterns by surveying orthopedic team physicians. We conducted a study to determine the demographics of NFL and NCAA team physicians and to identify patterns and variations in the management of common injuries in these groups of elite football players.

Materials and Methods

The study was reviewed by an Institutional Review Board before data collection and was classified as exempt. The study population consisted of head orthopedic team physicians for NFL teams and NCAA Division I universities. The survey (Appendix),

Chi-square tests were used to determine significant differences between groups. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Responses were received from 31 (97%) of the 32 NFL and 111 (93%) of the 119 NCAA team physicians. The 2 groups’ surveys were identical with the exception of question 3, regarding NFL division or NCAA conference.

Team Physician Demographics

All survey respondents were the head orthopedic physicians for their teams. Seventy-one percent were the head team physicians as well; another 25% named a primary care physician as the head team physician. Thirty-nine percent of the NFL team physicians had been a team physician at the NFL level for more than 15 years, and 58% of the NCAA team physicians had been a team physician at the Division I level for more than 15 years. Eighty-one percent of NFL and 66% of NCAA team physicians had fellowship training in sports medicine. For away games, 10% of NFL vs 65% of NCAA teams traveled with 2 physicians; 90% of NFL and 28% of NCAA teams traveled with 3 or more physicians.

Only a small percentage of respondents (NFL, 10%; NCAA, 14%) indicated they had received advertising in exchange for services. Most respondents (NFL, 93%; NCAA, 89%) did not pay to provide team coverage. In contrast, 97% of NFL vs only 31% of NCAA physicians indicated they received a monetary stipend for providing orthopedic coverage.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructions

Eighty-seven percent of NFL and 67% of NCAA respondents indicated that patellar tendon autograft was their preferred graft choice (Table 1).

Anterior Shoulder Dislocations (Without Bony Bankart)

Sling use after reduction of anterior shoulder dislocation was varied, with most physicians using a sling 2 weeks or less (Table 2).

Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries

Roughly two-thirds of respondents (NFL, 60%; NCAA, 69%) indicated that, during a game, they managed acute acromioclavicular (AC) joint injuries (type I/II) with injection of a local anesthetic that allowed return to play. In addition, a majority (NFL, 90%; NCAA, 87%) indicated they gave such athletes pregame injections that allowed them to play. About half the physicians (NFL, 57%; NCAA, 52%) injected the AC joint with cortisone during the acute/subacute period (<1 month) to decrease inflammation.

No significant difference was found between the 2 groups in terms of proportion of surgeons electing to treat type III AC joint injuries operatively versus nonoperatively (Table 4).

Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries

There was a significant (P < .0001) difference in use of prophylactic bracing for medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries (NFL, 28%; NCAA, 89%).

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries

The percentage of physicians who allowed athletes to return to play after a grade I/II posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury was significantly (P = .01) higher in NFL physicians (22%) than in NCAA physicians (7%). The amount of time varied up to more than 4 weeks (Figure 4).

Elbow Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears

A majority of respondents indicated they would treat a complete elbow ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) tear in a quarterback; a much smaller percentage preferred operative repair in athletes playing other positions (Table 6).

Thumb Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears

For athletes with in-season thumb UCL tears, 63% of NFL and 54% of NCAA physicians indicated they cast the thumb and allowed return to play. Others recommended operative repair and either cast the thumb and allowed return to play (NFL, 30%; NCAA, 41%) or let the thumb heal before allowing return to play (NFL, 7%; NCAA, 5%).

Fifth Metatarsal Fractures

For a large majority of physicians (NFL, 100%; NCAA, 94%), the preferred treatment for fifth metatarsal fractures was screw fixation.

Tibia Fractures

In the 5-year period before the survey, 43% of NFL and 75% of NCAA physicians managed at least one tibia fracture (P < .001) (Figure 7).

Ketorolac Injections

Intramuscular ketorolac injections were frequently given to elite football players, significantly (P < .01) more so in the NFL (93%) than in the NCAA (62%). The average number of injections varied among physicians, though a significantly (P < .0001) higher percentage of NFL (79%) than NCAA (13%) physicians gave 5 or more injections per game.

Discussion

This survey on managing common injuries in elite football players had an overall response rate of 94%. All NFL divisions and NCAA conferences were represented in physicians’ responses. Ninety percent of NFL and 65% of NCAA head team physicians were orthopedists. These findings differ from those of Stockard1 (1997), who surveyed athletic directors at Division I schools and reported 45% of head team physicians were family medicine-trained and 41% were orthopedists.

Given the high visibility of team coverage and the economics of college football’s highest division, one might expect team physicians to receive financial remuneration. This was not the case, according to our survey: Only 30% of physicians received a monetary stipend for team coverage, and only 14% received advertising in exchange for their services. Twelve NCAA team physicians indicated they pay to be allowed to provide team coverage.

Injury Management

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. For NFL and NCAA team physicians, the preferred graft choice for ACL reconstruction was patellar tendon autograft. This finding is similar to what Erickson and colleagues2 reported from a survey of NFL and NCAA team physicians: 86% of surgeons preferred bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) autograft. However, only 1 surgeon (0.7%) in that study, vs 16% in ours, preferred allograft. Allograft use may be somewhat controversial, as relevant data on competitive athletes are lacking, and it has been shown that the graft rupture rate3 is higher for BPTB allograft than for BPTB autograft in young patients. However, much of the data on higher failure rates with use of allograft in young patients4,5 has appeared since our data were collected.

Our return-to-play data are similar to data from other studies.2,6 According to our survey, the most common length of time from ACL reconstruction to return to football was 6 months, and 94% of team physicians allowed return to football by 9 months. In the survey by Erickson and colleagues,2 55% of surgeons waited a minimum of 6 months before returning athletes to play, and only 12% waited at least 9 months. In the study by Bradley and colleagues6 (2002), 84% of surgeons waited at least 6 months before returning athletes to play. Of note, we found a significantly higher percentage of NCAA football players than NFL players returning within 6 months after surgery. The difference may be attributable to a more cautious approach being taken with NFL players, whereas most NCAA players are limited in the time remaining in their football careers and want to return to the playing field as soon as possible.

Shoulder Dislocations. Responses to the 5 survey questions on anterior shoulder dislocation showed little consensus with respect to management. The exception pertained to use of a harness for in-season return to play with a dislocation—92% of physicians preferred management with a harness. Of note, 7 of 10 team surgeons performed anterior stabilization through an arthroscopic approach. Despite historical recommendations to perform open anterior stabilization in collision athletes, NFL and NCAA physicians’ practice patterns have evolved.7 Although return to contact activity was varied among responses, 94% of physicians allowed return to contact within 6 months.

Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries. For college football players, AC joint injuries are the most common shoulder injuries.8 In the NFL Combine, the incidence of AC joint injuries was 15.7 per 100 players.8 Several studies have cited favorable results with nonoperative management of type III AC joint injuries.9-12 Nonoperative management was the preferred treatment in our study as well, yet 26% of surgeons still preferred operative treatment in quarterbacks. Opinions about operative repair of type III injuries in overhead athletes vary,13 but nonoperative management clearly is the preferred method for elite football players. A 2013 study by Lynch and colleagues14 found that only 2 of 40 NFL players with type III AC joint injuries underwent surgery.

For type I and II AC joint injuries that occur during a game, more than two-thirds of the NCAA team physicians in our study favored injecting a local anesthetic to reduce pain and allow return to play in the same game. An even larger majority indicated they gave a pregame injection of an anesthetic to allow play. Similar use of injections for AC joint injuries has been reported in Australian-rules football and rugby.15Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries. Whether bracing is prophylactic against MCL injuries is controversial.16 Some studies have found it effective.17,18 According to our survey, 89% of Division I football teams used prophylactic knee bracing, mainly in offensive linemen but frequently in defensive linemen, too. No schools used bracing in athletes who played skill positions, except quarterbacks. Six schools used bracing on a quarterback’s front leg.

The percentage of teams that used prophylactic MCL bracing was significantly higher in the NCAA than in the NFL. NCAA team physicians generally have more control over players and therefore can implement widespread use of this bracing.

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. These injuries are infrequent. According to Parolie and Bergfeld,19 only 2% of college football players at the NFL Combine had a PCL injury. Treatment in athletes remains controversial. Our survey showed physicians’ willingness to return players to competition within 4 weeks after grade I/II PCL injuries. There is no consensus on management or on postinjury bracing. In operative cases, however, the preferred graft is allograft, and the preferred repair method is the arthroscopic single-bundle technique. These findings mirror those of a 2004 survey of the Herodicus Society by Dennis and colleagues.20 Elbow Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears. In throwing athletes with UCL tears, operative treatment has been recommended.21,22 A majority of our survey respondents preferred operative treatment for quarterbacks. However, operative treatment is still controversial, and quarterbacks differ from baseball players in their throwing motions and in the stresses acting on the UCLs during throwing. Two systematic reviews of UCL reconstruction have affirmed the positive outcomes of operative treatment in throwing athletes.21,22 However, most of the studies covered by these reviews focused on baseball players. In athletes playing positions other than quarterback, these injuries were typically treated nonoperatively.

Thumb Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears. Our survey respondents differed in their opinions on treating thumb UCL tears. About half recommended cast treatment, and the other half recommended operative treatment. Previous data suggest that delaying surgical treatment may be deleterious to the eventual outcome.23,24Fifth Metatarsal Fractures. For fifth metatarsal fractures, screw fixation was preferred by 90% of our survey respondents—vs 73% of NFL team physicians in a 2004 study by Low and colleagues.25 What remains controversial is the length of time before return to play. Our most frequent response was 4 to 6 weeks, and 46% of our respondents indicated they would wait 7 weeks or longer. These times differ significantly from what Low and colleagues25 reported: 86% of their physicians allowed return to competition after 6 to 12 weeks.

Tibia Fractures. Management of tibia fractures in US football players has not been reported. Chang and colleagues26 described 24 tibial shaft fractures in UK soccer players. Eleven fractures (~50%) were treated with intramedullary nails, 2 with plating, and 11 with conservative management. All players returned to activity, the operative group at 23.3 weeks and the nonoperative group at 27.6 weeks. Our respondents reported treating at least 150 tibial shaft fractures in the 5-year period before our survey, demonstrating the incidence and importance of this type of injury. A vast majority of team surgeons (96%) opted for treatment with intramedullary nailing. This choice may reflect an ability to return to play earlier—the ability to move the knee and maintain strength in the legs. Some have suggested it is important to remove the nail before the player returns to the football field, but this was not common practice among our groups of team surgeons. Other studies have not found any advantage to tibial nail removal.27Ketorolac Injections. Authors have described using ketorolac for the treatment of acute or pregame pain in professional football players.28-30 According to a 2000 survey, 93% of NFL teams used intramuscular ketorolac, and on average 15 players per team were treated, primarily on game day. Our survey found frequent use of ketorolac, with almost two-thirds of team orthopedists indicating pregame use. Ketorolac use was popular, particularly because of its effect in reducing postoperative pain and its potent effect in reducing pain on game day. However, injections by football team physicians have declined significantly in recent years, ever since an NFL Physician Society task force published recommendations on ketorolac use.31

Conclusion

There is a wide variety of patterns in treating athletes who play football at the highest levels of competition. Our findings can initiate further discussion on these topics and assist orthopedists providing game coverage at all levels of play in their decision-making process by helping to define the standard of care for their injured players.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E319-E327. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Among National Football League (NFL) and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) team physicians, there is no consensus on the management of various injuries. At national and regional meetings, the management of football injuries often is debated.

Given the high level of interest in the treatment of elite football players, we wanted to determine treatment patterns by surveying orthopedic team physicians. We conducted a study to determine the demographics of NFL and NCAA team physicians and to identify patterns and variations in the management of common injuries in these groups of elite football players.

Materials and Methods

The study was reviewed by an Institutional Review Board before data collection and was classified as exempt. The study population consisted of head orthopedic team physicians for NFL teams and NCAA Division I universities. The survey (Appendix),

Chi-square tests were used to determine significant differences between groups. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Responses were received from 31 (97%) of the 32 NFL and 111 (93%) of the 119 NCAA team physicians. The 2 groups’ surveys were identical with the exception of question 3, regarding NFL division or NCAA conference.

Team Physician Demographics

All survey respondents were the head orthopedic physicians for their teams. Seventy-one percent were the head team physicians as well; another 25% named a primary care physician as the head team physician. Thirty-nine percent of the NFL team physicians had been a team physician at the NFL level for more than 15 years, and 58% of the NCAA team physicians had been a team physician at the Division I level for more than 15 years. Eighty-one percent of NFL and 66% of NCAA team physicians had fellowship training in sports medicine. For away games, 10% of NFL vs 65% of NCAA teams traveled with 2 physicians; 90% of NFL and 28% of NCAA teams traveled with 3 or more physicians.

Only a small percentage of respondents (NFL, 10%; NCAA, 14%) indicated they had received advertising in exchange for services. Most respondents (NFL, 93%; NCAA, 89%) did not pay to provide team coverage. In contrast, 97% of NFL vs only 31% of NCAA physicians indicated they received a monetary stipend for providing orthopedic coverage.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructions

Eighty-seven percent of NFL and 67% of NCAA respondents indicated that patellar tendon autograft was their preferred graft choice (Table 1).

Anterior Shoulder Dislocations (Without Bony Bankart)

Sling use after reduction of anterior shoulder dislocation was varied, with most physicians using a sling 2 weeks or less (Table 2).

Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries

Roughly two-thirds of respondents (NFL, 60%; NCAA, 69%) indicated that, during a game, they managed acute acromioclavicular (AC) joint injuries (type I/II) with injection of a local anesthetic that allowed return to play. In addition, a majority (NFL, 90%; NCAA, 87%) indicated they gave such athletes pregame injections that allowed them to play. About half the physicians (NFL, 57%; NCAA, 52%) injected the AC joint with cortisone during the acute/subacute period (<1 month) to decrease inflammation.

No significant difference was found between the 2 groups in terms of proportion of surgeons electing to treat type III AC joint injuries operatively versus nonoperatively (Table 4).

Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries

There was a significant (P < .0001) difference in use of prophylactic bracing for medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries (NFL, 28%; NCAA, 89%).

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries

The percentage of physicians who allowed athletes to return to play after a grade I/II posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injury was significantly (P = .01) higher in NFL physicians (22%) than in NCAA physicians (7%). The amount of time varied up to more than 4 weeks (Figure 4).

Elbow Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears

A majority of respondents indicated they would treat a complete elbow ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) tear in a quarterback; a much smaller percentage preferred operative repair in athletes playing other positions (Table 6).

Thumb Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears

For athletes with in-season thumb UCL tears, 63% of NFL and 54% of NCAA physicians indicated they cast the thumb and allowed return to play. Others recommended operative repair and either cast the thumb and allowed return to play (NFL, 30%; NCAA, 41%) or let the thumb heal before allowing return to play (NFL, 7%; NCAA, 5%).

Fifth Metatarsal Fractures

For a large majority of physicians (NFL, 100%; NCAA, 94%), the preferred treatment for fifth metatarsal fractures was screw fixation.

Tibia Fractures

In the 5-year period before the survey, 43% of NFL and 75% of NCAA physicians managed at least one tibia fracture (P < .001) (Figure 7).

Ketorolac Injections

Intramuscular ketorolac injections were frequently given to elite football players, significantly (P < .01) more so in the NFL (93%) than in the NCAA (62%). The average number of injections varied among physicians, though a significantly (P < .0001) higher percentage of NFL (79%) than NCAA (13%) physicians gave 5 or more injections per game.

Discussion

This survey on managing common injuries in elite football players had an overall response rate of 94%. All NFL divisions and NCAA conferences were represented in physicians’ responses. Ninety percent of NFL and 65% of NCAA head team physicians were orthopedists. These findings differ from those of Stockard1 (1997), who surveyed athletic directors at Division I schools and reported 45% of head team physicians were family medicine-trained and 41% were orthopedists.

Given the high visibility of team coverage and the economics of college football’s highest division, one might expect team physicians to receive financial remuneration. This was not the case, according to our survey: Only 30% of physicians received a monetary stipend for team coverage, and only 14% received advertising in exchange for their services. Twelve NCAA team physicians indicated they pay to be allowed to provide team coverage.

Injury Management

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. For NFL and NCAA team physicians, the preferred graft choice for ACL reconstruction was patellar tendon autograft. This finding is similar to what Erickson and colleagues2 reported from a survey of NFL and NCAA team physicians: 86% of surgeons preferred bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) autograft. However, only 1 surgeon (0.7%) in that study, vs 16% in ours, preferred allograft. Allograft use may be somewhat controversial, as relevant data on competitive athletes are lacking, and it has been shown that the graft rupture rate3 is higher for BPTB allograft than for BPTB autograft in young patients. However, much of the data on higher failure rates with use of allograft in young patients4,5 has appeared since our data were collected.

Our return-to-play data are similar to data from other studies.2,6 According to our survey, the most common length of time from ACL reconstruction to return to football was 6 months, and 94% of team physicians allowed return to football by 9 months. In the survey by Erickson and colleagues,2 55% of surgeons waited a minimum of 6 months before returning athletes to play, and only 12% waited at least 9 months. In the study by Bradley and colleagues6 (2002), 84% of surgeons waited at least 6 months before returning athletes to play. Of note, we found a significantly higher percentage of NCAA football players than NFL players returning within 6 months after surgery. The difference may be attributable to a more cautious approach being taken with NFL players, whereas most NCAA players are limited in the time remaining in their football careers and want to return to the playing field as soon as possible.

Shoulder Dislocations. Responses to the 5 survey questions on anterior shoulder dislocation showed little consensus with respect to management. The exception pertained to use of a harness for in-season return to play with a dislocation—92% of physicians preferred management with a harness. Of note, 7 of 10 team surgeons performed anterior stabilization through an arthroscopic approach. Despite historical recommendations to perform open anterior stabilization in collision athletes, NFL and NCAA physicians’ practice patterns have evolved.7 Although return to contact activity was varied among responses, 94% of physicians allowed return to contact within 6 months.

Acromioclavicular Joint Injuries. For college football players, AC joint injuries are the most common shoulder injuries.8 In the NFL Combine, the incidence of AC joint injuries was 15.7 per 100 players.8 Several studies have cited favorable results with nonoperative management of type III AC joint injuries.9-12 Nonoperative management was the preferred treatment in our study as well, yet 26% of surgeons still preferred operative treatment in quarterbacks. Opinions about operative repair of type III injuries in overhead athletes vary,13 but nonoperative management clearly is the preferred method for elite football players. A 2013 study by Lynch and colleagues14 found that only 2 of 40 NFL players with type III AC joint injuries underwent surgery.

For type I and II AC joint injuries that occur during a game, more than two-thirds of the NCAA team physicians in our study favored injecting a local anesthetic to reduce pain and allow return to play in the same game. An even larger majority indicated they gave a pregame injection of an anesthetic to allow play. Similar use of injections for AC joint injuries has been reported in Australian-rules football and rugby.15Medial Collateral Ligament Injuries. Whether bracing is prophylactic against MCL injuries is controversial.16 Some studies have found it effective.17,18 According to our survey, 89% of Division I football teams used prophylactic knee bracing, mainly in offensive linemen but frequently in defensive linemen, too. No schools used bracing in athletes who played skill positions, except quarterbacks. Six schools used bracing on a quarterback’s front leg.

The percentage of teams that used prophylactic MCL bracing was significantly higher in the NCAA than in the NFL. NCAA team physicians generally have more control over players and therefore can implement widespread use of this bracing.

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. These injuries are infrequent. According to Parolie and Bergfeld,19 only 2% of college football players at the NFL Combine had a PCL injury. Treatment in athletes remains controversial. Our survey showed physicians’ willingness to return players to competition within 4 weeks after grade I/II PCL injuries. There is no consensus on management or on postinjury bracing. In operative cases, however, the preferred graft is allograft, and the preferred repair method is the arthroscopic single-bundle technique. These findings mirror those of a 2004 survey of the Herodicus Society by Dennis and colleagues.20 Elbow Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears. In throwing athletes with UCL tears, operative treatment has been recommended.21,22 A majority of our survey respondents preferred operative treatment for quarterbacks. However, operative treatment is still controversial, and quarterbacks differ from baseball players in their throwing motions and in the stresses acting on the UCLs during throwing. Two systematic reviews of UCL reconstruction have affirmed the positive outcomes of operative treatment in throwing athletes.21,22 However, most of the studies covered by these reviews focused on baseball players. In athletes playing positions other than quarterback, these injuries were typically treated nonoperatively.

Thumb Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears. Our survey respondents differed in their opinions on treating thumb UCL tears. About half recommended cast treatment, and the other half recommended operative treatment. Previous data suggest that delaying surgical treatment may be deleterious to the eventual outcome.23,24Fifth Metatarsal Fractures. For fifth metatarsal fractures, screw fixation was preferred by 90% of our survey respondents—vs 73% of NFL team physicians in a 2004 study by Low and colleagues.25 What remains controversial is the length of time before return to play. Our most frequent response was 4 to 6 weeks, and 46% of our respondents indicated they would wait 7 weeks or longer. These times differ significantly from what Low and colleagues25 reported: 86% of their physicians allowed return to competition after 6 to 12 weeks.

Tibia Fractures. Management of tibia fractures in US football players has not been reported. Chang and colleagues26 described 24 tibial shaft fractures in UK soccer players. Eleven fractures (~50%) were treated with intramedullary nails, 2 with plating, and 11 with conservative management. All players returned to activity, the operative group at 23.3 weeks and the nonoperative group at 27.6 weeks. Our respondents reported treating at least 150 tibial shaft fractures in the 5-year period before our survey, demonstrating the incidence and importance of this type of injury. A vast majority of team surgeons (96%) opted for treatment with intramedullary nailing. This choice may reflect an ability to return to play earlier—the ability to move the knee and maintain strength in the legs. Some have suggested it is important to remove the nail before the player returns to the football field, but this was not common practice among our groups of team surgeons. Other studies have not found any advantage to tibial nail removal.27Ketorolac Injections. Authors have described using ketorolac for the treatment of acute or pregame pain in professional football players.28-30 According to a 2000 survey, 93% of NFL teams used intramuscular ketorolac, and on average 15 players per team were treated, primarily on game day. Our survey found frequent use of ketorolac, with almost two-thirds of team orthopedists indicating pregame use. Ketorolac use was popular, particularly because of its effect in reducing postoperative pain and its potent effect in reducing pain on game day. However, injections by football team physicians have declined significantly in recent years, ever since an NFL Physician Society task force published recommendations on ketorolac use.31

Conclusion

There is a wide variety of patterns in treating athletes who play football at the highest levels of competition. Our findings can initiate further discussion on these topics and assist orthopedists providing game coverage at all levels of play in their decision-making process by helping to define the standard of care for their injured players.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(6):E319-E327. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Stockard AR. Team physician preferences at National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I universities. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1997;97(2):89-95.

2. Erickson BJ, Harris JD, Fillingham YA, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction practice patterns by NFL and NCAA football team physicians. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):731-738.

3. Kraeutler MJ, Bravman JT, McCarty EC. Bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft versus allograft in outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a meta-analysis of 5182 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2439-2448.

4. Bottoni CR, Smith EL, Shaha J, et al. Autograft versus allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized clinical study with a minimum 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(10):2501-2509.

5. Sun K, Tian S, Zhang J, Xia C, Zhang C, Yu T. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with BPTB autograft, irradiated versus non-irradiated allograft: a prospective randomized clinical study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(5):464-474.

6. Bradley JP, Klimkiewicz JJ, Rytel MJ, Powell JW. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and current treatment trends among team physicians. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(5):502-509.

7. Rhee YG, Ha JH, Cho NS. Anterior shoulder stabilization in collision athletes: arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):979-985.

8. Brophy RH, Barnes R, Rodeo SA, Warren RF. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders at the NFL Combine—trends from 1987 to 2000. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(1):22-27.

9. Bishop JY, Kaeding C. Treatment of the acute traumatic acromioclavicular separation. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):237-245.

10. Mazzocca AD, Arciero RA, Bicos J. Evaluation and treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):316-329.

11. Schlegel TF, Burks RT, Marcus RL, Dunn HK. A prospective evaluation of untreated acute grade III acromioclavicular separations. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):699-703.

12. Spencer EE Jr. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular joint injuries: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(455):38-44.

13. Kraeutler MJ, Williams GR Jr, Cohen SB, et al. Inter- and intraobserver reliability of the radiographic diagnosis and treatment of acromioclavicular joint separations. Orthopedics. 2012;35(10):e1483-e1487.

14. Lynch TS, Saltzman MD, Ghodasra JH, Bilimoria KY, Bowen MK, Nuber GW. Acromioclavicular joint injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and management. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(12):2904-2908.

15. Orchard JW. Benefits and risks of using local anaesthetic for pain relief to allow early return to play in professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(3):209-213.

16. Salata MJ, Gibbs AE, Sekiya JK. The effectiveness of prophylactic knee bracing in American football: a systematic review. Sports Health. 2010;2(5):375-379.

17. Albright JP, Powell JW, Smith W, et al. Medial collateral ligament knee sprains in college football. Effectiveness of preventive braces. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):12-18.

18. Sitler M, Ryan J, Hopkinson W, et al. The efficacy of a prophylactic knee brace to reduce knee injuries in football. A prospective, randomized study at West Point. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(3):310-315.

19. Parolie JM, Bergfeld JA. Long-term results of nonoperative treatment of isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in the athlete. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14(1):35-38.

20. Dennis MG, Fox JA, Alford JW, Hayden JK, Bach BR Jr. Posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: current trends. J Knee Surg. 2004;17(3):133-139.

21. Purcell DB, Matava MJ, Wright RW. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(455):72-77.

22. Vitale MA, Ahmad CS. The outcome of elbow ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in overhead athletes: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1193-1205.

23. Fricker R, Hintermann B. Skier’s thumb. Treatment, prevention and recommendations. Sports Med. 1995;19(1):73-79.

24. Smith RJ. Post-traumatic instability of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(1):14-21.

25. Low K, Noblin JD, Browne JE, Barnthouse CD, Scott AR. Jones fractures in the elite football player. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2004;13(3):156-160.

26. Chang WR, Kapasi Z, Daisley S, Leach WJ. Tibial shaft fractures in football players. J Orthop Surg Res. 2007;2:11.

27. Karladani AH, Ericsson PA, Granhed H, Karlsson L, Nyberg P. Tibial intramedullary nails—should they be removed? A retrospective study of 71 patients. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(5):668-671.

28. Eichner ER. Intramuscular ketorolac injections: the pregame Toradol parade. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(4):169-170.

29. Nepple JJ, Matava MJ. Soft tissue injections in the athlete. Sports Health. 2009;1(5):396-404.

30. Powell ET, Tokish JM, Hawkins RJ. Toradol use in the athletic population. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002;1(4):191.

31. Matava M, Brater DC, Gritter N, et al. Recommendations of the National Football League physician society task force on the use of toradol® ketorolac in the National Football League. Sports Health. 2012;4(5):377-383.

1. Stockard AR. Team physician preferences at National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I universities. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1997;97(2):89-95.

2. Erickson BJ, Harris JD, Fillingham YA, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction practice patterns by NFL and NCAA football team physicians. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):731-738.

3. Kraeutler MJ, Bravman JT, McCarty EC. Bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft versus allograft in outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a meta-analysis of 5182 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2439-2448.

4. Bottoni CR, Smith EL, Shaha J, et al. Autograft versus allograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized clinical study with a minimum 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(10):2501-2509.

5. Sun K, Tian S, Zhang J, Xia C, Zhang C, Yu T. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with BPTB autograft, irradiated versus non-irradiated allograft: a prospective randomized clinical study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(5):464-474.

6. Bradley JP, Klimkiewicz JJ, Rytel MJ, Powell JW. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and current treatment trends among team physicians. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(5):502-509.

7. Rhee YG, Ha JH, Cho NS. Anterior shoulder stabilization in collision athletes: arthroscopic versus open Bankart repair. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):979-985.

8. Brophy RH, Barnes R, Rodeo SA, Warren RF. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders at the NFL Combine—trends from 1987 to 2000. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(1):22-27.

9. Bishop JY, Kaeding C. Treatment of the acute traumatic acromioclavicular separation. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):237-245.

10. Mazzocca AD, Arciero RA, Bicos J. Evaluation and treatment of acromioclavicular joint injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):316-329.

11. Schlegel TF, Burks RT, Marcus RL, Dunn HK. A prospective evaluation of untreated acute grade III acromioclavicular separations. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):699-703.

12. Spencer EE Jr. Treatment of grade III acromioclavicular joint injuries: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(455):38-44.

13. Kraeutler MJ, Williams GR Jr, Cohen SB, et al. Inter- and intraobserver reliability of the radiographic diagnosis and treatment of acromioclavicular joint separations. Orthopedics. 2012;35(10):e1483-e1487.

14. Lynch TS, Saltzman MD, Ghodasra JH, Bilimoria KY, Bowen MK, Nuber GW. Acromioclavicular joint injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and management. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(12):2904-2908.

15. Orchard JW. Benefits and risks of using local anaesthetic for pain relief to allow early return to play in professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(3):209-213.

16. Salata MJ, Gibbs AE, Sekiya JK. The effectiveness of prophylactic knee bracing in American football: a systematic review. Sports Health. 2010;2(5):375-379.

17. Albright JP, Powell JW, Smith W, et al. Medial collateral ligament knee sprains in college football. Effectiveness of preventive braces. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):12-18.

18. Sitler M, Ryan J, Hopkinson W, et al. The efficacy of a prophylactic knee brace to reduce knee injuries in football. A prospective, randomized study at West Point. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(3):310-315.

19. Parolie JM, Bergfeld JA. Long-term results of nonoperative treatment of isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries in the athlete. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14(1):35-38.

20. Dennis MG, Fox JA, Alford JW, Hayden JK, Bach BR Jr. Posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: current trends. J Knee Surg. 2004;17(3):133-139.

21. Purcell DB, Matava MJ, Wright RW. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;(455):72-77.

22. Vitale MA, Ahmad CS. The outcome of elbow ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in overhead athletes: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1193-1205.

23. Fricker R, Hintermann B. Skier’s thumb. Treatment, prevention and recommendations. Sports Med. 1995;19(1):73-79.

24. Smith RJ. Post-traumatic instability of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(1):14-21.

25. Low K, Noblin JD, Browne JE, Barnthouse CD, Scott AR. Jones fractures in the elite football player. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2004;13(3):156-160.

26. Chang WR, Kapasi Z, Daisley S, Leach WJ. Tibial shaft fractures in football players. J Orthop Surg Res. 2007;2:11.

27. Karladani AH, Ericsson PA, Granhed H, Karlsson L, Nyberg P. Tibial intramedullary nails—should they be removed? A retrospective study of 71 patients. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(5):668-671.

28. Eichner ER. Intramuscular ketorolac injections: the pregame Toradol parade. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(4):169-170.

29. Nepple JJ, Matava MJ. Soft tissue injections in the athlete. Sports Health. 2009;1(5):396-404.

30. Powell ET, Tokish JM, Hawkins RJ. Toradol use in the athletic population. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002;1(4):191.

31. Matava M, Brater DC, Gritter N, et al. Recommendations of the National Football League physician society task force on the use of toradol® ketorolac in the National Football League. Sports Health. 2012;4(5):377-383.

Finding Balance: New Strategies to Optimize Care for Patients With Parkinson’s Disease Psychosis

This activity is supported by an independent educational grant from ACADIA Pharmaceuticals LLC

After reading this CME supplement, health care providers will have improved their ability to:

|

This CME supplement entitles the reader to 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™

Click here to read supplement.

After reading the supplement, click here to access the CME posttest

This activity is supported by an independent educational grant from ACADIA Pharmaceuticals LLC

After reading this CME supplement, health care providers will have improved their ability to:

|

This CME supplement entitles the reader to 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™

Click here to read supplement.

After reading the supplement, click here to access the CME posttest

This activity is supported by an independent educational grant from ACADIA Pharmaceuticals LLC

After reading this CME supplement, health care providers will have improved their ability to:

|

This CME supplement entitles the reader to 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™

Click here to read supplement.

After reading the supplement, click here to access the CME posttest

Thigh Injuries in American Football

American football has the highest injury rate of any team sport in the United States at the high school, collegiate, and professional levels.1-3 Muscle strains and contusions constitute a large proportion of football injuries. For example, at the high school level, muscle strains comprise 12% to 24% of all injuries;2 at the collegiate level, they account for approximately 20% of all practice injuries, with nearly half of all strains occurring within the thigh.1,4 Among a single National Football League (NFL) team, Feeley and colleagues5 reported that muscle strains accounted for 46% of practice and 22% of preseason game injuries. The hamstrings, followed by the quadriceps, are the most commonly strained muscle groups among both professional and amateur athletes,5,6 with hamstring and quadriceps injuries making up approximately 13% of all injuries among NFL players.7 Given the relatively large surface area and muscle volume of the anterior and posterior thigh, as well as the activities and maneuvers necessitated by the various football positions, it is not surprising that the thigh is frequently involved in football-related injuries.

The purpose of this review is to describe the clinical manifestations of thigh-related soft-tissue injuries seen in football players. Two of these conditions—muscle strains and contusions—are relatively common, while a third condition—the Morel-Lavallée lesion—is a rare, yet relevant injury that warrants discussion.

Quadriceps Contusion

Pathophysiology

Contusion to the quadriceps muscle is a common injury in contact sports generally resulting from a direct blow from a helmet, knee, or shoulder.8 Bleeding within the musculature causes swelling, pain, stiffness, and limitation of quadriceps excursion, ultimately resulting in loss of knee flexion and an inability to run or squat. The injury is typically confined to a single quadriceps muscle.8 The use of thigh padding, though helpful, does not completely eliminate the risk of this injury.

History and Physical Examination

Immediately after injury, the athlete may complain only of thigh pain. However, swelling, pain, and diminished range of knee motion may develop within the first 24 hours depending on the severity of injury and how quickly treatment is instituted.8 Jackson and Feagin9 developed an injury grading system for quadriceps contusions based on the limitation of knee flexion observed (Table 1).

Imaging

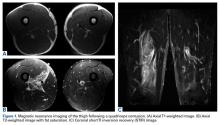

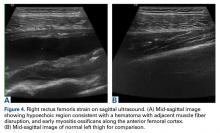

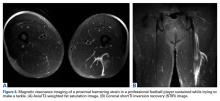

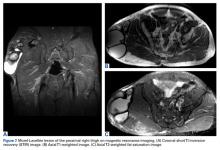

A quadriceps contusion is a clinical diagnosis based on a typical history and physical examination; therefore, advanced imaging usually does not need to be obtained except to gauge the severity of injury, to rule out concurrent injuries (ie, tendon rupture), and to identify the presence of a hematoma that may necessitate aspiration. Plain radiographs are typically unremarkable in the acute setting. Appearance on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) varies by injury severity, with increased signal throughout the affected muscle belly and a diffuse, feathery appearance centered at the point of impact on short TI inversion recovery (STIR) and T2-weighted images reflecting edema and possibly hematoma (Figures 1A-1C).8,11

Treatment

Treatment of a quadriceps contusion is nonoperative and consists of a 3-phase recovery.10 The first phase lasts approximately 2 days and consists of rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) to limit hemorrhage. The knee should be rested in a flexed position to maintain quadriceps muscle fiber length in order to promote muscle compression and limit knee stiffness. For severe contusions in which there is a question of an acute thigh compartment syndrome, compression should be avoided with appropriate treatment based on typical symptoms and intra-compartmental pressure measurement.12 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may be administered to diminish pain as well as the risk of myositis ossificans. While there is no data on the efficacy of NSAIDs in preventing myositis ossificans following quadriceps contusions, both COX-2 selective (ie, celecoxib) and nonselective (ie, naproxen, indomethacin) COX inhibitors have been demonstrated to significantly reduce the incidence of heterotopic ossification following hip surgery—a condition occurring from a similar pathophysiologic process as myositis ossificans.13-17 However, this class of drugs should not be given any sooner than 48 to 72 hours after injury to decrease further bleeding risk, given its inhibitory effect on platelet function.18 Narcotic pain medications are rarely required.

The second phase focuses on restoring active and passive knee and hip flexion and begins when permitted by pain.8 Icing, pain control, and physical therapy modalities are also continued in order to reduce pain and swelling as knee motion is progressed. The third phase begins once full range of knee and hip motion is restored and consists of quadriceps strengthening and functional rehabilitation of the lower extremity.8,19 Return to athletic activities and eventually competition should take place when a full, painless range of motion is restored and strength returns to baseline. Isokinetic strength testing may be utilized to more accurately assess strength and endurance. Noncontact, position-specific drills are incorporated as clinical improvement allows. A full recovery should be expected within 4 weeks of injury, with faster resolution and return to play seen in less severe contusions depending on the athlete’s position.8 Continued quadriceps stretching is recommended to prevent recurrence once the athlete returns to play. A protective hard shell may also be utilized both during rehabilitation as well as once the athlete returns to play in order to protect the thigh from reinjury, which may increase the risk of myositis ossificans.8

Complications

A prolonged recovery or persistent symptoms should alert the treating physician to the possibility of complications, including myositis ossificans.8,20 Myositis ossificans typically results from moderate to severe contusions, which may present initially as a painful, indurated mass that later becomes quite firm. This mass may be seen on plain radiographs as early as 2 to 4 weeks following injury if the athlete complains of persistent pain or a palpable thigh mass (Figure 2).9

Mani-Babu and colleagues23 reported a case of a 14-year-old male football player who sustained a quadriceps contusion after a direct blow from an opponent’s helmet to the lateral thigh. Persistent pain and limitation of motion at 2 months follow-up prompted imaging studies that demonstrated myositis ossificans. The patient was treated with intravenous pamidronate (a bisphosphonate) twice over a 3-month period and demonstrated a full recovery within 5 months.

Acute compartment syndrome of the thigh has also been reported following severe quadriceps contusions, with the majority occurring in the anterior compartment.12,24-28 When injury from blunt trauma extends into and disrupts the muscular layer adjacent to the femur, vascular disruption can cause hematoma formation, muscle edema, and significant swelling, thereby increasing intracompartmental pressure. The relatively large volume of the anterior thigh compartment and lack of a rigid deep fascial envelope may be protective from the development of compartment syndrome compared to other sites.28 It can be difficult to distinguish a severe contusion from a compartment syndrome, as both can occur from the same mechanism and have similar presenting signs and symptoms. Signs of a compartment syndrome include pain out of proportion to the injury that is aggravated by passive stretch of the quadriceps muscles, an increasingly firm muscle compartment to palpation, and neurovascular deficits.29 Both acute compartment syndrome and a severe contusion may present with significant pain, inability to bear weight, tense swelling, tenderness to palpation, and pain with passive knee flexion.24 While the successful conservative treatment of athletes with acute compartment syndrome of the thigh has been reported, it is important to closely monitor the patient’s condition and consider intracompartmental pressure monitoring if the patient’s clinical condition deteriorates.12 An acute fasciotomy should be strongly considered when intracompartmental pressures are within 30 mm Hg of diastolic pressure.24-27 Fortunately, it is highly uncommon for thigh compartment pressure to rise to this level. Percutaneous compartment decompression using liposuction equipment or a large cannula has been described to decrease intracompartmental pressure, potentially expediting recovery and minimizing morbidity.18 Interestingly, reports of fasciotomies for acute thigh compartment syndrome following closed athletic injuries have not described necrotic or non-contractile muscle typical of an acute compartment syndrome, calling into question the need for fasciotomy following closed blunt athletic trauma to the thigh.18

Quadriceps Strain

Pathophysiology

Acute quadriceps strains occur during sudden forceful eccentric contraction of the extensor mechanism. Occasionally, in the absence of a clear mechanism, these injuries mistakenly appear as a contusion resulting from a direct blow to the thigh.30,31 The rectus femoris is the most frequently strained quadriceps muscle due, in part, to its superficial location and predominance of type II muscle fibers, which are more likely to be strained.11,32 Although classically described as occurring along the distal portion of the rectus femoris at the musculotendinous junction, quadriceps strains most commonly occur at the mid to proximal aspect of the rectus femoris.30,33 The quadriceps muscle complex crosses 2 joints and, as a result, is more predisposed to eccentric injury than mono-articular muscles.34 We have had a subset of complete myotendinous tears of the rectus femoris that occur in the plant leg of placekickers that result in significant disability.

Risk Factors

Quadriceps and thigh injuries comprise approximately 4.5% of injuries among NFL players.7 Several risk factors for quadriceps strains have been described. In a study of Australian Rules football players, Orchard35 demonstrated that for all muscle strains, the strongest risk factor was a recent history of the same injury, with the next strongest risk factor being a past history of the same injury. Increasing age was found to be a risk factor for hamstring strains but not quadriceps strains. Muscle fatigue may also contribute to injury susceptibility.36

History and Physical Examination

Injuries typically occur during kicking, jumping, or a sudden change in direction while running.30 Athletes may localize pain anywhere along the quadriceps muscle, although strains most commonly occur at the proximal to mid portion of the rectus femoris.30,33 The grading system for quadriceps strains described by Kary30 is based on level of pain, quadriceps strength, and the presence or absence of a palpable defect (Table 2).

The athlete typically walks with an antalgic gait. Visible swelling and/or ecchymosis may be present depending on when the athlete is seen, as ecchymosis may develop within the first 24 hours of injury. The examiner should palpate along the entire length of the injured muscle. High-grade strains or complete tears may present with a bulge or defect in the muscle belly, but in most cases no defect will be palpable. There may be loss of knee flexion similar to a quadriceps contusion. Strength testing should be performed in both the sitting and prone position with the hip both flexed and extended to assess resisted knee extension strength.30 Loss of strength is proportional to the degree of injury.

Imaging

While most quadriceps strains are adequately diagnosed clinically without the need for imaging studies, ultrasound or MRI can be used to evaluate for partial or complete rupture.30,33 In milder cases, MRI usually demonstrates interstitial edema and hemorrhage with a feathery appearance on STIR and T2-weighted imaging (Figures 3A-3C).11

Treatment

Acute treatment of quadriceps strains focuses on minimizing bleeding using the principles of RICE treatment.37 NSAIDs may be used immediately to assist with pain control.30 COX-2-specific NSAIDs are preferred due to their lack of any inhibitory effect on platelet function in order to reduce the risk of further bleeding within the muscle compartment. For the first 24 to 72 hours following injury, the quadriceps should be maintained relatively immobilized to prevent further injury.38 High-grade injuries might necessitate crutches for ambulatory assistance.

Depending on injury severity, the active phase of treatment usually begins within 5 days of injury and consists of stretching and knee/hip range of motion. An active warm-up should precede rehabilitation exercises to activate neural pathways within the muscle and improve muscle elasticity.38 Ballistic stretching should be avoided to prevent additional injury to the muscle fibers. Strengthening should proceed when the athlete recovers a pain-free range of motion. When isometric exercises can be completed at increasing degrees of knee flexion, isotonic exercises may be implemented into the rehabilitation program.30 Return to football can be considered when the athlete has recovered knee and hip range of motion, is pain-free, and has near-normal strength compared to the contralateral side. The athlete should also perform satisfactorily in simulated position-specific activities in a noncontact fashion prior to return to full competition.30

Hamstring Strain

Pathophysiology

Hamstring strains are the most common noncontact injuries in football resulting from excessive muscle stretching during eccentric contraction generally occurring at the musculotendinous junction.5,39 Because the hamstrings cross both the hip and knee, simultaneous hip flexion and knee extension results in maximal lengthening, making them most vulnerable to injury at the terminal swing phase of gait just prior to heel strike.39-42 The long head of the biceps femoris undergoes the greatest stretch, reaching 110% of resting length during terminal swing phase and is the most commonly injured hamstring muscle.43,44 Injury occurs when the force of eccentric contraction, and resulting muscle strain, exceeds the mechanical limits of the tissue.42,45 It remains to be shown whether hamstring strains occur as a result of accumulated microscopic muscle damage or secondary to a single event that exceeds the mechanical limits of the muscle.42

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The majority of hamstring strains are sustained during noncontact activities, with most athletes citing sprinting as the activity at the time of injury.3 Approximately 93% of injuries occur during noncontact activities among defensive backs and wide receivers.3 Hamstring strains are the second-most common injury among NFL players, comprising approximately 9% of all injuries,5,7 with 16% to 31% of these injuries associated with recurrence.3,5,35,46 Using the NFL’s Injury Surveillance System, Elliott and colleagues3 reported 1716 hamstring strains over a 10-year period (1989-1998). Fifty-one percent of hamstring strains occurred during the 7-week preseason, with a greater than 4-fold increased injury rate noted during the preseason compared to the 16-week regular season. An increased incidence in the preseason is partially attributable to relative deconditioning over the offseason. Defensive backs, wide receivers, and special teams players accounted for the majority of injured players, suggesting that speed position players and those who must “backpedal” (run backwards) are at an increased risk for injury.

Several risk factors for hamstring strain have been described, including prior injury, older age, quadriceps-hamstring strength imbalances, limited hip and knee flexibility, and fatigue.39,42,47 Inadequate rehabilitation and premature return to competition are also likely important factors predisposing to recurrent injury.39,48

History and Physical Examination

The majority of hamstring strains occur in the acute setting when the player experiences the sudden onset of pain in the posterior thigh during strenuous exercise, most commonly while sprinting.39 The injury typically occurs in the early or late stage of practice or competition due, in part, to inadequate warm-up or fatigue. The athlete may describe an audible pop and an inability to continue play, depending on injury severity.