User login

Chemo has greater impact on male fertility

Photo by Nina Matthews

Results of a large study suggest that female survivors of childhood cancer may have more luck than their male peers when it comes to conceiving a child.

Both male and female childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) reported fewer pregnancies and live births than their healthy siblings.

However, chemotherapeutic agents appeared to have a much greater impact on the fertility of male CCSs than female CCSs.

Eric Chow, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Oncology.

Previous research has shown that fertility can be compromised by several types of chemotherapy, mainly alkylating drugs. However, little is known about the dose effects on pregnancy from newer drugs, such as ifosfamide and cisplatin, in CCSs.

With this in mind, Dr Chow and his colleagues analyzed data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, which tracks subjects who were diagnosed with the most common types of childhood cancer before the age of 21 and treated at 27 institutions across the US and Canada between 1970 and 1999.

Patients had been diagnosed with leukemias, lymphomas, and neuroblastoma, as well as kidney, brain, soft tissue, and bone tumors. All had survived at least 5 years after diagnosis.

The researchers examined the impact of various doses of 14 commonly used chemotherapy drugs on pregnancy and live birth in 10,938 male and female CCSs, compared with 3949 siblings.

The team specifically focused on CCSs who were treated with chemotherapy and did not receive any radiotherapy to the pelvis or the brain.

The drugs the researchers evaluated were busulfan, carboplatin, carmustine, chlorambucil, chlormethine, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, dacarbazine, ifosfamide, lomustine, melphalan, procarbazine, temozolomide, and thiotepa.

Outcomes

Multivariable analysis showed that CCSs were significantly less likely than their siblings to have or sire a pregnancy. For male CCSs, the hazard ratio (HR) was 0.63 (P<0.0001). For female CCSs, the HR was 0.87 (P<0.0001).

CCSs were also significantly less likely to have a live birth. For male CCSs, the HR was 0.63 (P<0.0001). For female CCSs, the HR was 0.82 (P<0.0001).

The researchers noted that, overall, female CCSs were less likely to conceive and have a child when compared to their siblings, but the effect was much smaller than that observed among the men.

In addition, the difference between CCSs and siblings was more pronounced for women who delayed pregnancy until they were 30 or older, possibly because chemotherapy exposure might accelerate the natural depletion of eggs and hasten menopause.

Impact of specific drugs

In male CCSs, the reduced likelihood of siring a pregnancy was associated with upper tertile doses of cyclophosphamide (HR=0.60, P<0.0001), ifosfamide (HR=0.42, P=0.0069), procarbazine (HR=0.30, P<0.0001), and cisplatin (HR=0.56, P=0.0023).

Cyclophosphamide-equivalent dose in male CCSs was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of siring a pregnancy per 5000 mg/m2 increments (HR=0.82, P<0.0001).

In female CCSs, the reduced likelihood of becoming pregnant was associated with busulfan—both at doses less than 450 mg/m2 (HR=0.22, P=0.020) and at doses of 450 mg/m2 or higher (HR=0.14, P=0.0051)—and with doses of lomustine at 411 mg/m2 or greater (HR=0.41, P=0.046).

Cyclophosphamide-equivalent dose in female CCSs was associated with risk only at the highest doses in analyses categorized by quartile (upper quartile vs no exposure, HR=0.85, P=0.023).

Limitations and implications

The researchers noted that a limitation of this study is that it relied on self-reported pregnancy and live birth, and some pregnancies may go unrecognized.

And although the findings are consistent with others in the field, this study did not account for other factors such as marital or cohabitation status, the intention to conceive, or length of time attempting to conceive.

The researchers also noted that, although the total number of CCSs in this study is large, the number of patients who were exposed to individual drugs varied significantly. So while the overall conclusions of the study are consistent with previous studies, more research is needed to estimate the exact risk of some less commonly used drugs.

“We think these results will be encouraging for most women who were treated with chemotherapy in childhood,” Dr Chow said. “However, I think we, as pediatric oncologists, still need to do a better job discussing fertility and fertility preservation options with patients and families upfront before starting cancer treatment.”

“In particular, all boys diagnosed post-puberty should be encouraged to bank their sperm to maximize their reproductive options in the future. The current options for post-pubertal girls remain more complicated but include oocyte and embryo cryopreservation.” ![]()

Photo by Nina Matthews

Results of a large study suggest that female survivors of childhood cancer may have more luck than their male peers when it comes to conceiving a child.

Both male and female childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) reported fewer pregnancies and live births than their healthy siblings.

However, chemotherapeutic agents appeared to have a much greater impact on the fertility of male CCSs than female CCSs.

Eric Chow, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Oncology.

Previous research has shown that fertility can be compromised by several types of chemotherapy, mainly alkylating drugs. However, little is known about the dose effects on pregnancy from newer drugs, such as ifosfamide and cisplatin, in CCSs.

With this in mind, Dr Chow and his colleagues analyzed data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, which tracks subjects who were diagnosed with the most common types of childhood cancer before the age of 21 and treated at 27 institutions across the US and Canada between 1970 and 1999.

Patients had been diagnosed with leukemias, lymphomas, and neuroblastoma, as well as kidney, brain, soft tissue, and bone tumors. All had survived at least 5 years after diagnosis.

The researchers examined the impact of various doses of 14 commonly used chemotherapy drugs on pregnancy and live birth in 10,938 male and female CCSs, compared with 3949 siblings.

The team specifically focused on CCSs who were treated with chemotherapy and did not receive any radiotherapy to the pelvis or the brain.

The drugs the researchers evaluated were busulfan, carboplatin, carmustine, chlorambucil, chlormethine, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, dacarbazine, ifosfamide, lomustine, melphalan, procarbazine, temozolomide, and thiotepa.

Outcomes

Multivariable analysis showed that CCSs were significantly less likely than their siblings to have or sire a pregnancy. For male CCSs, the hazard ratio (HR) was 0.63 (P<0.0001). For female CCSs, the HR was 0.87 (P<0.0001).

CCSs were also significantly less likely to have a live birth. For male CCSs, the HR was 0.63 (P<0.0001). For female CCSs, the HR was 0.82 (P<0.0001).

The researchers noted that, overall, female CCSs were less likely to conceive and have a child when compared to their siblings, but the effect was much smaller than that observed among the men.

In addition, the difference between CCSs and siblings was more pronounced for women who delayed pregnancy until they were 30 or older, possibly because chemotherapy exposure might accelerate the natural depletion of eggs and hasten menopause.

Impact of specific drugs

In male CCSs, the reduced likelihood of siring a pregnancy was associated with upper tertile doses of cyclophosphamide (HR=0.60, P<0.0001), ifosfamide (HR=0.42, P=0.0069), procarbazine (HR=0.30, P<0.0001), and cisplatin (HR=0.56, P=0.0023).

Cyclophosphamide-equivalent dose in male CCSs was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of siring a pregnancy per 5000 mg/m2 increments (HR=0.82, P<0.0001).

In female CCSs, the reduced likelihood of becoming pregnant was associated with busulfan—both at doses less than 450 mg/m2 (HR=0.22, P=0.020) and at doses of 450 mg/m2 or higher (HR=0.14, P=0.0051)—and with doses of lomustine at 411 mg/m2 or greater (HR=0.41, P=0.046).

Cyclophosphamide-equivalent dose in female CCSs was associated with risk only at the highest doses in analyses categorized by quartile (upper quartile vs no exposure, HR=0.85, P=0.023).

Limitations and implications

The researchers noted that a limitation of this study is that it relied on self-reported pregnancy and live birth, and some pregnancies may go unrecognized.

And although the findings are consistent with others in the field, this study did not account for other factors such as marital or cohabitation status, the intention to conceive, or length of time attempting to conceive.

The researchers also noted that, although the total number of CCSs in this study is large, the number of patients who were exposed to individual drugs varied significantly. So while the overall conclusions of the study are consistent with previous studies, more research is needed to estimate the exact risk of some less commonly used drugs.

“We think these results will be encouraging for most women who were treated with chemotherapy in childhood,” Dr Chow said. “However, I think we, as pediatric oncologists, still need to do a better job discussing fertility and fertility preservation options with patients and families upfront before starting cancer treatment.”

“In particular, all boys diagnosed post-puberty should be encouraged to bank their sperm to maximize their reproductive options in the future. The current options for post-pubertal girls remain more complicated but include oocyte and embryo cryopreservation.” ![]()

Photo by Nina Matthews

Results of a large study suggest that female survivors of childhood cancer may have more luck than their male peers when it comes to conceiving a child.

Both male and female childhood cancer survivors (CCSs) reported fewer pregnancies and live births than their healthy siblings.

However, chemotherapeutic agents appeared to have a much greater impact on the fertility of male CCSs than female CCSs.

Eric Chow, MD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Oncology.

Previous research has shown that fertility can be compromised by several types of chemotherapy, mainly alkylating drugs. However, little is known about the dose effects on pregnancy from newer drugs, such as ifosfamide and cisplatin, in CCSs.

With this in mind, Dr Chow and his colleagues analyzed data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, which tracks subjects who were diagnosed with the most common types of childhood cancer before the age of 21 and treated at 27 institutions across the US and Canada between 1970 and 1999.

Patients had been diagnosed with leukemias, lymphomas, and neuroblastoma, as well as kidney, brain, soft tissue, and bone tumors. All had survived at least 5 years after diagnosis.

The researchers examined the impact of various doses of 14 commonly used chemotherapy drugs on pregnancy and live birth in 10,938 male and female CCSs, compared with 3949 siblings.

The team specifically focused on CCSs who were treated with chemotherapy and did not receive any radiotherapy to the pelvis or the brain.

The drugs the researchers evaluated were busulfan, carboplatin, carmustine, chlorambucil, chlormethine, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, dacarbazine, ifosfamide, lomustine, melphalan, procarbazine, temozolomide, and thiotepa.

Outcomes

Multivariable analysis showed that CCSs were significantly less likely than their siblings to have or sire a pregnancy. For male CCSs, the hazard ratio (HR) was 0.63 (P<0.0001). For female CCSs, the HR was 0.87 (P<0.0001).

CCSs were also significantly less likely to have a live birth. For male CCSs, the HR was 0.63 (P<0.0001). For female CCSs, the HR was 0.82 (P<0.0001).

The researchers noted that, overall, female CCSs were less likely to conceive and have a child when compared to their siblings, but the effect was much smaller than that observed among the men.

In addition, the difference between CCSs and siblings was more pronounced for women who delayed pregnancy until they were 30 or older, possibly because chemotherapy exposure might accelerate the natural depletion of eggs and hasten menopause.

Impact of specific drugs

In male CCSs, the reduced likelihood of siring a pregnancy was associated with upper tertile doses of cyclophosphamide (HR=0.60, P<0.0001), ifosfamide (HR=0.42, P=0.0069), procarbazine (HR=0.30, P<0.0001), and cisplatin (HR=0.56, P=0.0023).

Cyclophosphamide-equivalent dose in male CCSs was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of siring a pregnancy per 5000 mg/m2 increments (HR=0.82, P<0.0001).

In female CCSs, the reduced likelihood of becoming pregnant was associated with busulfan—both at doses less than 450 mg/m2 (HR=0.22, P=0.020) and at doses of 450 mg/m2 or higher (HR=0.14, P=0.0051)—and with doses of lomustine at 411 mg/m2 or greater (HR=0.41, P=0.046).

Cyclophosphamide-equivalent dose in female CCSs was associated with risk only at the highest doses in analyses categorized by quartile (upper quartile vs no exposure, HR=0.85, P=0.023).

Limitations and implications

The researchers noted that a limitation of this study is that it relied on self-reported pregnancy and live birth, and some pregnancies may go unrecognized.

And although the findings are consistent with others in the field, this study did not account for other factors such as marital or cohabitation status, the intention to conceive, or length of time attempting to conceive.

The researchers also noted that, although the total number of CCSs in this study is large, the number of patients who were exposed to individual drugs varied significantly. So while the overall conclusions of the study are consistent with previous studies, more research is needed to estimate the exact risk of some less commonly used drugs.

“We think these results will be encouraging for most women who were treated with chemotherapy in childhood,” Dr Chow said. “However, I think we, as pediatric oncologists, still need to do a better job discussing fertility and fertility preservation options with patients and families upfront before starting cancer treatment.”

“In particular, all boys diagnosed post-puberty should be encouraged to bank their sperm to maximize their reproductive options in the future. The current options for post-pubertal girls remain more complicated but include oocyte and embryo cryopreservation.” ![]()

Flooring poses higher cancer risk than previously reported

while woman looks on

US government agencies have released a revised report on the health risks associated with formaldehyde in certain types of laminate flooring.

The new report corrects a previous error and reveals an increase in the estimated lifetime risk of cancers, including leukemias, for individuals who regularly breathe in formaldehyde from the flooring.

The report also suggests that irritation and breathing problems can result in anyone exposed to the flooring.

The report was compiled by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH).

About the report

On March 1, 2015, the CBS news program 60 Minutes reported that an American company, Lumber Liquidators®, was selling laminate wood flooring produced in China that released elevated levels of formaldehyde.

Based on this allegation, the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) tested laminate flooring samples manufactured in China from 2012 to 2014 that were sold at Lumber Liquidators® stores. The CPSC then requested that the NCEH and ATSDR evaluate the test results for possible health effects.

The NCEH and ATSDR published a report detailing the possible health effects on February 10, 2016. But the report was pulled on February 19, 2016, after the agencies were informed that the report’s indoor air model incorporated an incorrect value for ceiling height.

As a result, the health risks were calculated using airborne concentration estimates about 3 times lower than they should have been.

Since the discovery of the error, the NCEH and ATSDR revised the value in the model, conducted a review of the revised results, and re-evaluated the possible health implications.

In addition, the revised report has been reviewed by outside experts and experts from the CPSC, the US Environmental Protection Agency, and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Results

The revised report concludes that irritation and breathing problems could occur in everyone exposed to formaldehyde in the tested flooring.

The previous report suggested such problems might only occur in sensitive groups (eg, children) and people with pre-existing health conditions (eg, asthma).

The new report also increased the estimated lifetime cancer risk from breathing the highest levels of formaldehyde from the affected flooring all day, every day for 2 years.

The previous estimate of lifetime cancer risk was 2 to 9 extra cases for every 100,000 people.

The new estimate is 6 to 30 extra cases per 100,000 people.

There is conflicting data regarding the types of cancers associated with formaldehyde exposure, but many studies have suggested that formaldehyde causes cancer of the nasopharynx, sinuses, and nasal cavity, as well as leukemia, particularly myeloid leukemia.

Recommendations

Although the revised report shows an increase in health risks associated with the flooring, the NCEH and ATSDR said their recommendations remain the same.

They recommend that people with the affected flooring:

- Reduce their exposure to formaldehyde in their homes by opening windows, running exhaust fans, avoiding use of other products containing formaldehyde, etc.

- See a doctor for ongoing health symptoms such as breathing problems or irritation of the eyes, nose, or throat

- Weigh the pros and cons of professional air testing

- Consult a professional before removing the flooring, as removing it may release more formaldehyde into the home.

while woman looks on

US government agencies have released a revised report on the health risks associated with formaldehyde in certain types of laminate flooring.

The new report corrects a previous error and reveals an increase in the estimated lifetime risk of cancers, including leukemias, for individuals who regularly breathe in formaldehyde from the flooring.

The report also suggests that irritation and breathing problems can result in anyone exposed to the flooring.

The report was compiled by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH).

About the report

On March 1, 2015, the CBS news program 60 Minutes reported that an American company, Lumber Liquidators®, was selling laminate wood flooring produced in China that released elevated levels of formaldehyde.

Based on this allegation, the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) tested laminate flooring samples manufactured in China from 2012 to 2014 that were sold at Lumber Liquidators® stores. The CPSC then requested that the NCEH and ATSDR evaluate the test results for possible health effects.

The NCEH and ATSDR published a report detailing the possible health effects on February 10, 2016. But the report was pulled on February 19, 2016, after the agencies were informed that the report’s indoor air model incorporated an incorrect value for ceiling height.

As a result, the health risks were calculated using airborne concentration estimates about 3 times lower than they should have been.

Since the discovery of the error, the NCEH and ATSDR revised the value in the model, conducted a review of the revised results, and re-evaluated the possible health implications.

In addition, the revised report has been reviewed by outside experts and experts from the CPSC, the US Environmental Protection Agency, and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Results

The revised report concludes that irritation and breathing problems could occur in everyone exposed to formaldehyde in the tested flooring.

The previous report suggested such problems might only occur in sensitive groups (eg, children) and people with pre-existing health conditions (eg, asthma).

The new report also increased the estimated lifetime cancer risk from breathing the highest levels of formaldehyde from the affected flooring all day, every day for 2 years.

The previous estimate of lifetime cancer risk was 2 to 9 extra cases for every 100,000 people.

The new estimate is 6 to 30 extra cases per 100,000 people.

There is conflicting data regarding the types of cancers associated with formaldehyde exposure, but many studies have suggested that formaldehyde causes cancer of the nasopharynx, sinuses, and nasal cavity, as well as leukemia, particularly myeloid leukemia.

Recommendations

Although the revised report shows an increase in health risks associated with the flooring, the NCEH and ATSDR said their recommendations remain the same.

They recommend that people with the affected flooring:

- Reduce their exposure to formaldehyde in their homes by opening windows, running exhaust fans, avoiding use of other products containing formaldehyde, etc.

- See a doctor for ongoing health symptoms such as breathing problems or irritation of the eyes, nose, or throat

- Weigh the pros and cons of professional air testing

- Consult a professional before removing the flooring, as removing it may release more formaldehyde into the home.

while woman looks on

US government agencies have released a revised report on the health risks associated with formaldehyde in certain types of laminate flooring.

The new report corrects a previous error and reveals an increase in the estimated lifetime risk of cancers, including leukemias, for individuals who regularly breathe in formaldehyde from the flooring.

The report also suggests that irritation and breathing problems can result in anyone exposed to the flooring.

The report was compiled by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH).

About the report

On March 1, 2015, the CBS news program 60 Minutes reported that an American company, Lumber Liquidators®, was selling laminate wood flooring produced in China that released elevated levels of formaldehyde.

Based on this allegation, the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) tested laminate flooring samples manufactured in China from 2012 to 2014 that were sold at Lumber Liquidators® stores. The CPSC then requested that the NCEH and ATSDR evaluate the test results for possible health effects.

The NCEH and ATSDR published a report detailing the possible health effects on February 10, 2016. But the report was pulled on February 19, 2016, after the agencies were informed that the report’s indoor air model incorporated an incorrect value for ceiling height.

As a result, the health risks were calculated using airborne concentration estimates about 3 times lower than they should have been.

Since the discovery of the error, the NCEH and ATSDR revised the value in the model, conducted a review of the revised results, and re-evaluated the possible health implications.

In addition, the revised report has been reviewed by outside experts and experts from the CPSC, the US Environmental Protection Agency, and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Results

The revised report concludes that irritation and breathing problems could occur in everyone exposed to formaldehyde in the tested flooring.

The previous report suggested such problems might only occur in sensitive groups (eg, children) and people with pre-existing health conditions (eg, asthma).

The new report also increased the estimated lifetime cancer risk from breathing the highest levels of formaldehyde from the affected flooring all day, every day for 2 years.

The previous estimate of lifetime cancer risk was 2 to 9 extra cases for every 100,000 people.

The new estimate is 6 to 30 extra cases per 100,000 people.

There is conflicting data regarding the types of cancers associated with formaldehyde exposure, but many studies have suggested that formaldehyde causes cancer of the nasopharynx, sinuses, and nasal cavity, as well as leukemia, particularly myeloid leukemia.

Recommendations

Although the revised report shows an increase in health risks associated with the flooring, the NCEH and ATSDR said their recommendations remain the same.

They recommend that people with the affected flooring:

- Reduce their exposure to formaldehyde in their homes by opening windows, running exhaust fans, avoiding use of other products containing formaldehyde, etc.

- See a doctor for ongoing health symptoms such as breathing problems or irritation of the eyes, nose, or throat

- Weigh the pros and cons of professional air testing

- Consult a professional before removing the flooring, as removing it may release more formaldehyde into the home.

Parasite competition influences drug resistance

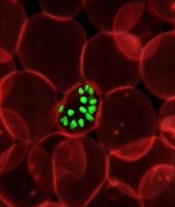

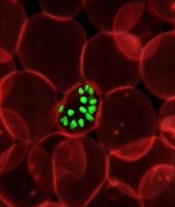

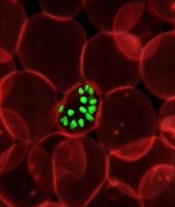

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers say they have documented how competition among different malaria parasite strains in human hosts could influence the spread of drug resistance.

“We found that when hosts are co-infected with drug-resistant and drug-sensitive strains, both strains are competitively suppressed,” said Mary Bushman, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

“Antimalarial therapy, by clearing drug-sensitive parasites from mixed infections, may result in competitive release of resistant strains.”

Bushman and her colleagues described these findings in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The researchers focused on the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which has developed resistance to former first-line therapies chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine.

“We’re now down to our last treatment, artemisinin combination therapy, or ACT, and resistance to that recently emerged in Southeast Asia,” Bushman said. “If ACT resistance continues to follow the same pattern, the world may soon be without reliable antimalarial drugs.”

In addition, people infected with P falciparum often have multiple strains of the parasite, especially in high-transmission areas such as sub-Saharan Africa, where infectious mosquito bites occur frequently. Many people have developed partial immunity, making asymptomatic infections common and further complicating control efforts.

With previous work in lab mice, the researchers found that competition between mixed strains of malaria parasites were a crucial determinant to the spread of resistance.

“In the mouse studies, we found that drug-sensitive parasites suppress resistant parasites,” said Jaap de Roode, PhD, of Emory University.

“We also found that by clearing these sensitive parasites with drugs, the resistant parasites had a big advantage, growing up to high numbers and transmitting to mosquitoes at high rates. Ever since doing that work, I have wanted to see if the same could apply to humans.”

To find out, Dr de Roode and his colleagues analyzed 1341 blood samples from untreated children with malaria living in Angola, Ghana, and Tanzania.

The researchers extracted the DNA of malaria parasites from the blood samples and used polymerase chain reaction technology to determine the densities of drug-resistant strains and drug-sensitive ones. About 15% of the samples had mixtures of both types.

Analyses showed that, in mixed-strain infections, densities of chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains were reduced in the presence of competitors.

The results also showed that, in the absence of chloroquine, the resistant strains had lower densities than sensitive strains.

“The results were really clear cut, which rarely happens in human studies,” Bushman said. “We found almost complete consistency between the 3 data sets [divided by country].”

Bushman added that the tendency is to use a “one-size-fits-all” strategy for controlling malaria, but this research suggests that more tailored approaches are needed.

For example, a strategy of mass drug administration might be effective in a place with a low prevalence of malaria and less likelihood of mixed-strain infections. However, that same strategy might actually boost drug resistance without reducing the burden of disease in areas where most of the population is infected with multiple strains of malaria parasites.

“The epidemiology of malaria infection is different for different places and different conditions,” Bushman said. “We hope that our work will spur development of new strategies to minimize resistance while maximizing the benefits of control measures.”

However, more questions must be answered to guide the development of these new strategies.

“As a first step, we need to determine if the observed suppression of resistance in humans also results in reduced transmission to mosquitoes,” Dr de Roode said.

Another avenue to explore is resistance among patients who have received antimalarial treatment.

“We need to find out if drug treatment of people infected with malaria removes competition and gives resistance a boost, as we have found in mice before,” Dr de Roode noted. ![]()

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers say they have documented how competition among different malaria parasite strains in human hosts could influence the spread of drug resistance.

“We found that when hosts are co-infected with drug-resistant and drug-sensitive strains, both strains are competitively suppressed,” said Mary Bushman, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

“Antimalarial therapy, by clearing drug-sensitive parasites from mixed infections, may result in competitive release of resistant strains.”

Bushman and her colleagues described these findings in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The researchers focused on the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which has developed resistance to former first-line therapies chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine.

“We’re now down to our last treatment, artemisinin combination therapy, or ACT, and resistance to that recently emerged in Southeast Asia,” Bushman said. “If ACT resistance continues to follow the same pattern, the world may soon be without reliable antimalarial drugs.”

In addition, people infected with P falciparum often have multiple strains of the parasite, especially in high-transmission areas such as sub-Saharan Africa, where infectious mosquito bites occur frequently. Many people have developed partial immunity, making asymptomatic infections common and further complicating control efforts.

With previous work in lab mice, the researchers found that competition between mixed strains of malaria parasites were a crucial determinant to the spread of resistance.

“In the mouse studies, we found that drug-sensitive parasites suppress resistant parasites,” said Jaap de Roode, PhD, of Emory University.

“We also found that by clearing these sensitive parasites with drugs, the resistant parasites had a big advantage, growing up to high numbers and transmitting to mosquitoes at high rates. Ever since doing that work, I have wanted to see if the same could apply to humans.”

To find out, Dr de Roode and his colleagues analyzed 1341 blood samples from untreated children with malaria living in Angola, Ghana, and Tanzania.

The researchers extracted the DNA of malaria parasites from the blood samples and used polymerase chain reaction technology to determine the densities of drug-resistant strains and drug-sensitive ones. About 15% of the samples had mixtures of both types.

Analyses showed that, in mixed-strain infections, densities of chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains were reduced in the presence of competitors.

The results also showed that, in the absence of chloroquine, the resistant strains had lower densities than sensitive strains.

“The results were really clear cut, which rarely happens in human studies,” Bushman said. “We found almost complete consistency between the 3 data sets [divided by country].”

Bushman added that the tendency is to use a “one-size-fits-all” strategy for controlling malaria, but this research suggests that more tailored approaches are needed.

For example, a strategy of mass drug administration might be effective in a place with a low prevalence of malaria and less likelihood of mixed-strain infections. However, that same strategy might actually boost drug resistance without reducing the burden of disease in areas where most of the population is infected with multiple strains of malaria parasites.

“The epidemiology of malaria infection is different for different places and different conditions,” Bushman said. “We hope that our work will spur development of new strategies to minimize resistance while maximizing the benefits of control measures.”

However, more questions must be answered to guide the development of these new strategies.

“As a first step, we need to determine if the observed suppression of resistance in humans also results in reduced transmission to mosquitoes,” Dr de Roode said.

Another avenue to explore is resistance among patients who have received antimalarial treatment.

“We need to find out if drug treatment of people infected with malaria removes competition and gives resistance a boost, as we have found in mice before,” Dr de Roode noted. ![]()

infecting a red blood cell

Image courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

Researchers say they have documented how competition among different malaria parasite strains in human hosts could influence the spread of drug resistance.

“We found that when hosts are co-infected with drug-resistant and drug-sensitive strains, both strains are competitively suppressed,” said Mary Bushman, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

“Antimalarial therapy, by clearing drug-sensitive parasites from mixed infections, may result in competitive release of resistant strains.”

Bushman and her colleagues described these findings in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The researchers focused on the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, which has developed resistance to former first-line therapies chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine.

“We’re now down to our last treatment, artemisinin combination therapy, or ACT, and resistance to that recently emerged in Southeast Asia,” Bushman said. “If ACT resistance continues to follow the same pattern, the world may soon be without reliable antimalarial drugs.”

In addition, people infected with P falciparum often have multiple strains of the parasite, especially in high-transmission areas such as sub-Saharan Africa, where infectious mosquito bites occur frequently. Many people have developed partial immunity, making asymptomatic infections common and further complicating control efforts.

With previous work in lab mice, the researchers found that competition between mixed strains of malaria parasites were a crucial determinant to the spread of resistance.

“In the mouse studies, we found that drug-sensitive parasites suppress resistant parasites,” said Jaap de Roode, PhD, of Emory University.

“We also found that by clearing these sensitive parasites with drugs, the resistant parasites had a big advantage, growing up to high numbers and transmitting to mosquitoes at high rates. Ever since doing that work, I have wanted to see if the same could apply to humans.”

To find out, Dr de Roode and his colleagues analyzed 1341 blood samples from untreated children with malaria living in Angola, Ghana, and Tanzania.

The researchers extracted the DNA of malaria parasites from the blood samples and used polymerase chain reaction technology to determine the densities of drug-resistant strains and drug-sensitive ones. About 15% of the samples had mixtures of both types.

Analyses showed that, in mixed-strain infections, densities of chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains were reduced in the presence of competitors.

The results also showed that, in the absence of chloroquine, the resistant strains had lower densities than sensitive strains.

“The results were really clear cut, which rarely happens in human studies,” Bushman said. “We found almost complete consistency between the 3 data sets [divided by country].”

Bushman added that the tendency is to use a “one-size-fits-all” strategy for controlling malaria, but this research suggests that more tailored approaches are needed.

For example, a strategy of mass drug administration might be effective in a place with a low prevalence of malaria and less likelihood of mixed-strain infections. However, that same strategy might actually boost drug resistance without reducing the burden of disease in areas where most of the population is infected with multiple strains of malaria parasites.

“The epidemiology of malaria infection is different for different places and different conditions,” Bushman said. “We hope that our work will spur development of new strategies to minimize resistance while maximizing the benefits of control measures.”

However, more questions must be answered to guide the development of these new strategies.

“As a first step, we need to determine if the observed suppression of resistance in humans also results in reduced transmission to mosquitoes,” Dr de Roode said.

Another avenue to explore is resistance among patients who have received antimalarial treatment.

“We need to find out if drug treatment of people infected with malaria removes competition and gives resistance a boost, as we have found in mice before,” Dr de Roode noted. ![]()

A Click Is Not a Clunk: Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in a Newborn

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Newborn hip evaluation algorithm

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), previously known as congenital dislocation of the hip, follows a spectrum of irregular anatomic hip development spanning from acetabular dysplasia to irreducible dislocation at birth. Early detection is critical to improve the overall prognosis. Prompt diagnosis requires understanding of potential risk factors, proficiency in physical examination techniques, and implementation of appropriate screening tools when indicated. Although current guidelines direct timing for physical exam screenings, imaging, and treatment, it is ultimately up to the provider to determine the best course of action on a case-by-case basis. This article provides a review of these topics and more.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed guidelines for detection of hip dysplasia, including recommendation of relevant physical exam screenings for all newborns.1 In 2007, the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA) encouraged providers to follow the AAP guidelines with a continued recommendation to perform newborn screening for hip instability and routine follow-up evaluations until the child achieves walking.2 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) also established clinical guidelines in 2014 that are endorsed by both AAP and POSNA.3 These guidelines support routine clinical screening; research evaluated infants up to 6 months old, however, limiting the recommendations to that age-group.

Failure to treat DDH early has been associated with serious negative sequelae that include chronic pain, degenerative arthritis, postural scoliosis, and early gait disturbances.4 Primary care providers are expected to perform thorough newborn hip exams with associated specialized tests (ie, Ortolani and Barlow, which are discussed in “Physical exam”) at each routine follow-up. Heightened clinical suspicion and risk factor awareness are key for primary care providers to promptly identify patients requiring orthopedic referral. With early diagnosis, a removable soft abduction brace can be applied as the initial treatment. When treatment is delayed, however, closed reduction under anesthesia or complex surgical intervention may be required.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The etiology for DDH remains unknown. Hip dysplasia typically presents unilaterally but can also occur bilaterally. DDH is more likely to affect the left hip than the right.5

Reported incidence varies, ranging from 0.06 to 76.1 per 1,000 live births, and is largely affected by race and geographic location.5 Incidence is higher in countries where routine screening is required, by either physical examination or ultrasound (1.6 to 28.5 and 34.0 to 60.3 per 1,000, respectively), compared with countries not requiring routine screening (1.3 per 1,000). This may suggest that the majority of hip dysplasia cases are transient and resolve spontaneously without treatment.6,7

RISK FACTORS AND PATIENT HISTORY

Known risk factors for DDH include breech presentation (see Figure 1), positive family history, and female gender.5,8-10 Female infants are eight times more likely than males to develop DDH.10 Firstborn status is also recognized as an associated risk factor, which may be attributable to space constraints in utero. This hypothesis is further supported by the relative DDH-protective effect of prematurity and low birth weight. Other potential risk factors include advanced maternal age, birth weight that is high for gestational age, decreased hip abduction, and joint laxity. However, the majority of patients with hip dysplasia have no identifiable risk factors.3,5,9,11,12

Swaddling, which often maintains the hips in an adducted and/or extended position, has also been strongly associated with hip dysplasia.5,13 Multiple organizations, including the AAOS,AAP, POSNA, and the International Hip Dysplasia Institute, have developed or endorsed hip-healthy swaddling recommendations to minimize the risk for DDH in swaddled infants.13-15 Such practices allow the infant’s legs to bend up and out at the hips, promoting free hip movement, flexion, and abduction.13,15 Swaddling has demonstrated multiple benefits (including improved sleep and relief of excessive crying13) and continues to be recommended by many US providers; however, those caring for infants at risk for DDH should avoid traditional swaddling and/or practice hip-healthy swaddling techniques.10,13,14 Early diagnosis starts with the clinician’s knowledge of DDH risk factors and the recommended screening protocols. The presence of multiple risk factors will increase the likelihood of this condition and should lower the clinician’s threshold for ordering additional screening, regardless of hip exam findings.

PHYSICAL EXAM

Both AAP and AAOS guidelines recommend clinical screening for DDH with physical exam in all newborns.1,3 A head-to-toe musculoskeletal exam is warranted during the initial evaluation of every newborn in order to assess for any known DDH-associated conditions, which may include neuromuscular disorders, torticollis, and metatarsus adductus.5

Initial evaluation of an infant with DDH may reveal nonspecific findings, including asymmetric skin folds and limb-length inequality. The Galeazzi sign should be sought by aligning flexed knees with the child in the supine position and assessing for uneven knee heights (see Figure 2). Unilateral posterior hip dislocation or femoral shortening represents a positive Galeazzi sign.16 Joint laxity and limited hip abduction have also been associated with DDH.1,10

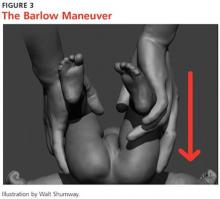

Barlow and Ortolani exams are more specific to DDH and should be completed at newborn screening and each subsequent well-baby exam.1 The Barlow maneuver is a provocative test with flexion, adduction, and posterior pressure through the infant’s hip (Figure 3). A palpable clunk during the Barlow maneuver indicates positive instability with posterior displacement. The Ortolani test is a reductive maneuver requiring abduction with posterior pressure to lift the greater trochanter (Figure 4). A clunk sensation with this test is positive for reduction of the hip.

The infant’s diaper should be removed during the hip evaluation. These exams are more reliable when each hip is evaluated separately with the pelvis stabilized.10 All physical exam findings must be carefully documented at each encounter.1,17

It is critical for the examiner to understand the appropriate technique and potential results when conducting each of these specialized hip exams. A true positive finding is the clunking sensation that occurs with the dislocation or relocation of the affected hip; this finding is better felt than heard. In contrast, a benign hip click with these maneuvers is a more subtle sensation—typically, a soft-tissue snapping or catching—and is not diagnostic of DDH. A click is not a clunk and is not indicative of DDH.1,3

DDH may present later in infancy or early childhood; therefore, DDH should remain within the differential diagnosis for gait asymmetry, unequal hip motion, or limb-length discrepancy. It may be beneficial to continue to evaluate for these developments during routine exams as part of a thorough pediatric musculoskeletal assessment, particularly in patients with documented risk factors for DDH.1,3,4 Delay in diagnosis of DDH, it should be noted, is a relatively common complaint in pediatric medical malpractice lawsuits; until the early 2000s, this condition represented about 75% of claims in one medical malpractice database.The decrease in claims has been attributed to better awareness and earlier diagnosis of DDH. 17

Continue for the diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

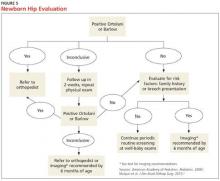

A positive Ortolani or Barlow sign is diagnostic and warrants prompt orthopedic referral (Figure 5). If physical examination results are equivocal or inconclusive, follow-up at two weeks is recommended, with continued routine follow-up until walking is achieved. Patients with persistent equivocal findings at the two-week follow-up warrant ultrasound at age 3 to 4 weeks or orthopedic referral. Infants with significant risk factors, particularly breech presentation at birth, should also undergo imaging.18 AAP recommends ultrasound at age 6 weeks or radiograph after 4 months of age.1,18 AAOS recommends performing an imaging study before age 6 months when at least one of the following risk factors is present: breech presentation, positive family history of DDH, or previous clinical instability (moderate level of evidence).3

IMAGING

Ultrasound is the diagnostic test of choice for infants because radiographs have limited value until the femoral heads begin to ossify at age 4 to 6 months.18 Ultrasonography allows for visualization of the cartilaginous portion of the acetabulum and femoral head.1 Dynamic stressing is performed during ultrasound to assess the level of hip stability. A provider trained in ultrasound will measure the depth of the acetabulum and identify any potential laxity or instability of the hip joint. Accuracy of these findings is largely dependent on the experience and skill of the examiner.

Ultrasound evaluation is not recommended until after age 3 to 4 weeks. Earlier findings may include mild laxity and immature morphology of the acetabulum, which often resolve spontaneously.1,18 Use of ultrasound is currently recommended only to confirm diagnostic suspicion, based on clinical findings, or for infants with significant risk factors.18 Universal ultrasound screening in newborns is not recommended and would incur unnecessary costs.1,3,9 Plain radiographs are used after age 4 months to confirm a diagnosis of DDH or to assess for residual dysplasia.3,18

Continue for management >>

MANAGEMENT

Once hip dysplasia is suggested by physical exam or imaging study, the child’s subsequent care should be provided by an orthopedic specialist with experience in treating this condition. Treatment is preferably initiated before age 6 weeks.12 The specifics of treatment are largely based on age at diagnosis and the severity of dysplasia.

The goal of treatment is to maintain the hips in a stable position with the femoral head well covered by the acetabulum. This will improve anatomic development and function. Early clinical diagnosis is often sufficient to justify initiating conservative treatment; additionally, early detection of DDH can considerably reduce the need for surgical intervention.12 Although the potential for spontaneous resolution is high, the consequences associated with delay in care can be significant.

Preferred initial management, which can be initiated before confirmation of DDH by ultrasound, involves implementation of soft abduction support.19 The Pavlik harness is the support design of choice (Figure 6).12 This harness maintains hip flexion and abduction, creating concentric reduction of the femoral head. The brace is highly successful when its use is initiated early. Treatment in a Pavlik harness requires nearly full-time wear and close monitoring by a clinician. Unlikely potential risks associated with this treatment include avascular necrosis and femoral nerve palsy.4

Ultrasonography is used to further monitor treatment and to determine length of wear. Long-term results suggest a success rate exceeding 90%.20,21 However, this rate may be falsely elevated due to the number of hips that likely would have improved spontaneously without treatment.6,19

The Pavlik harness becomes less effective with increasing age, and a more rigid abduction brace may be considered in infants older than 6 months.20 Overall outcomes improve once the femoral head is consistently maintained in the acetabulum. Delay in treatment is associated with an increase in the long-term complications associated with residual hip dysplasia.22

Once an infant is undergoing treatment for DDH in a Pavlik harness, there is no need for primary care providers to continue to perform provocative testing, such as the Ortolani or Barlow test, at routine well-baby checks. Unnecessary stress to the hips is not beneficial, and any new results will not change the treatment being provided by the orthopedic specialist. Adjustments to the fit of the harness should be made only by the orthopedist, unless femoral nerve palsy is noted on exam. This development warrants immediate discontinuation of harness use until symptoms resolve.21

Abduction bracing may not be suitable for all cases of hip dysplasia. Newborns with irreducible hips, more advanced dysplasia, or associated neuromuscular or syndromic disorder may require closed versus open reduction and casting. More invasive surgical options may also be considered in advanced dysplasia in order to reshape the joint and improve function.20,22

Continue for patient education >>

PATIENT EDUCATION

Parents should be fully educated on the options for managing hip dysplasia. Once DDH is diagnosed, prompt referral to an orthopedic specialist is critical in order to weigh the treatment options and to develop the appropriate individualized plan for each child. Once treatment is initiated, parental compliance is essential; frequent meetings between parents and the specialist are important.

Parents of infants with known risk factors for and/or suspicion of hip dysplasia should also be educated on hip-healthy swaddling to allow for free motion of the hips and knees.10,13 Advise them that some commercial baby carriers and slings may maintain the hips in an undesirable extended position. In both swaddling and with baby carriers, care should be taken to allow for hip abduction and flexion. Caution should also be taken during diaper changes to avoid lifting the legs and thereby causing unnecessary stress to the hips.

CONCLUSION

Developmental dysplasia of the hip can be a disabling pediatric condition. Early diagnosis improves the likelihood of successful treatment during infancy and can prevent serious complications. If untreated, DDH can lead to joint degeneration and premature arthritis. Recognition and treatment within the first six weeks of life is crucial to the overall outcome.

The role of a primary care provider is to identify hip dysplasia risk factors and recognize associated physical exam findings in order to refer to an orthopedic specialist in a timely manner. Guidelines from the AAP, POSNA, and AAOS help direct this process in order to effectively identify infants at risk and in need of treatment.

REFERENCES

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Clinical practice guideline: early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 1):896-905.

2. Schwend RM, Schoenecker P, Richards BS, et al. Screening the newborn for developmental dysplasia of the hip: now what do we do? J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):607-610.

3. Mulpuri K, Song KM, Goldberg MJ, Sevarino K. Detection and nonoperative management of pediatric developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants up to six months of age. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(3):202-205.

4. Thomas SRYW. A review of long-term outcomes for late presenting developmental hip dysplasia. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(6):729-733.

5. Loder RT, Skopelja EN. The epidemiology and demographics of hip dysplasia. ISRN Orthop. 2011;2011:238607.

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):898-902.

7. Shorter D, Hong T, Osborn DA. Screening programmes for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD004595.

8. Loder RT, Shafer C. The demographics of developmental hip dysplasia in the Midwestern United States (Indiana). J Child Orthop. 2015;9(1):93-98.

9. Paton RW, Hinduja K, Thomas CD. The significance of at-risk factors in ultrasound surveillance of developmental dysplasia of the hip: a ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1264-1266.

10. Alsaleem M, Set KK, Saadeh L. Developmental dysplasia of hip: a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54(10):921-928.

11. Chan A, McCaul KA, Cundy PJ, et al. Perinatal risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76(2):F94-F100.

12. Godley DR. Assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. JAAPA. 2013;26(3):54-58.

13. Van Sleuwen BE, Engelberts AC, Boere-Boonekamp MM, et al. Swaddling: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1097-e1106.

14. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Position statement: swaddling and developmental hip dysplasia. www.aaos.org/uploadedFiles/PreProduction/About/Opinion_Statements/position/1186%20Swaddling%20and%20Developmental%20Hip%20Dysplasia.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2016.

15. Clarke NM. Swaddling and hip dysplasia: an orthopaedic perspective. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(1):5-6.

16. Storer SK, Skaggs DL. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(8):1310-1316.

17. McAbee GN, Donn SM, Mendelson RA, et al. Medical diagnoses commonly associated with pediatric malpractice lawsuits in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1282-e1286.

18. Imrie M, Scott V, Stearns P, et al. Is ultrasound screening for DDH in babies born breech sufficient? J Child Orthop. 2010;4(1):3-8.

19. Chen HW, Chang CH, Tsai ST, et al. Natural progression of hip dysplasia in newborns: a reflection of hip ultrasonographic screenings in newborn nurseries. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19(5):418-423.

20. Gans I, Flynn JM, Sankar WN. Abduction bracing for residual acetabular dysplasia in infantile DDH. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33(7):714-718.

21. Murnaghan ML, Browne RH, Sucato DJ, Birch J. Femoral nerve palsy in Pavlik harness treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(5):493-499.

22. Dezateux C, Rosendahl K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1541-1552.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Newborn hip evaluation algorithm

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), previously known as congenital dislocation of the hip, follows a spectrum of irregular anatomic hip development spanning from acetabular dysplasia to irreducible dislocation at birth. Early detection is critical to improve the overall prognosis. Prompt diagnosis requires understanding of potential risk factors, proficiency in physical examination techniques, and implementation of appropriate screening tools when indicated. Although current guidelines direct timing for physical exam screenings, imaging, and treatment, it is ultimately up to the provider to determine the best course of action on a case-by-case basis. This article provides a review of these topics and more.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed guidelines for detection of hip dysplasia, including recommendation of relevant physical exam screenings for all newborns.1 In 2007, the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA) encouraged providers to follow the AAP guidelines with a continued recommendation to perform newborn screening for hip instability and routine follow-up evaluations until the child achieves walking.2 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) also established clinical guidelines in 2014 that are endorsed by both AAP and POSNA.3 These guidelines support routine clinical screening; research evaluated infants up to 6 months old, however, limiting the recommendations to that age-group.

Failure to treat DDH early has been associated with serious negative sequelae that include chronic pain, degenerative arthritis, postural scoliosis, and early gait disturbances.4 Primary care providers are expected to perform thorough newborn hip exams with associated specialized tests (ie, Ortolani and Barlow, which are discussed in “Physical exam”) at each routine follow-up. Heightened clinical suspicion and risk factor awareness are key for primary care providers to promptly identify patients requiring orthopedic referral. With early diagnosis, a removable soft abduction brace can be applied as the initial treatment. When treatment is delayed, however, closed reduction under anesthesia or complex surgical intervention may be required.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The etiology for DDH remains unknown. Hip dysplasia typically presents unilaterally but can also occur bilaterally. DDH is more likely to affect the left hip than the right.5

Reported incidence varies, ranging from 0.06 to 76.1 per 1,000 live births, and is largely affected by race and geographic location.5 Incidence is higher in countries where routine screening is required, by either physical examination or ultrasound (1.6 to 28.5 and 34.0 to 60.3 per 1,000, respectively), compared with countries not requiring routine screening (1.3 per 1,000). This may suggest that the majority of hip dysplasia cases are transient and resolve spontaneously without treatment.6,7

RISK FACTORS AND PATIENT HISTORY

Known risk factors for DDH include breech presentation (see Figure 1), positive family history, and female gender.5,8-10 Female infants are eight times more likely than males to develop DDH.10 Firstborn status is also recognized as an associated risk factor, which may be attributable to space constraints in utero. This hypothesis is further supported by the relative DDH-protective effect of prematurity and low birth weight. Other potential risk factors include advanced maternal age, birth weight that is high for gestational age, decreased hip abduction, and joint laxity. However, the majority of patients with hip dysplasia have no identifiable risk factors.3,5,9,11,12

Swaddling, which often maintains the hips in an adducted and/or extended position, has also been strongly associated with hip dysplasia.5,13 Multiple organizations, including the AAOS,AAP, POSNA, and the International Hip Dysplasia Institute, have developed or endorsed hip-healthy swaddling recommendations to minimize the risk for DDH in swaddled infants.13-15 Such practices allow the infant’s legs to bend up and out at the hips, promoting free hip movement, flexion, and abduction.13,15 Swaddling has demonstrated multiple benefits (including improved sleep and relief of excessive crying13) and continues to be recommended by many US providers; however, those caring for infants at risk for DDH should avoid traditional swaddling and/or practice hip-healthy swaddling techniques.10,13,14 Early diagnosis starts with the clinician’s knowledge of DDH risk factors and the recommended screening protocols. The presence of multiple risk factors will increase the likelihood of this condition and should lower the clinician’s threshold for ordering additional screening, regardless of hip exam findings.

PHYSICAL EXAM

Both AAP and AAOS guidelines recommend clinical screening for DDH with physical exam in all newborns.1,3 A head-to-toe musculoskeletal exam is warranted during the initial evaluation of every newborn in order to assess for any known DDH-associated conditions, which may include neuromuscular disorders, torticollis, and metatarsus adductus.5

Initial evaluation of an infant with DDH may reveal nonspecific findings, including asymmetric skin folds and limb-length inequality. The Galeazzi sign should be sought by aligning flexed knees with the child in the supine position and assessing for uneven knee heights (see Figure 2). Unilateral posterior hip dislocation or femoral shortening represents a positive Galeazzi sign.16 Joint laxity and limited hip abduction have also been associated with DDH.1,10

Barlow and Ortolani exams are more specific to DDH and should be completed at newborn screening and each subsequent well-baby exam.1 The Barlow maneuver is a provocative test with flexion, adduction, and posterior pressure through the infant’s hip (Figure 3). A palpable clunk during the Barlow maneuver indicates positive instability with posterior displacement. The Ortolani test is a reductive maneuver requiring abduction with posterior pressure to lift the greater trochanter (Figure 4). A clunk sensation with this test is positive for reduction of the hip.

The infant’s diaper should be removed during the hip evaluation. These exams are more reliable when each hip is evaluated separately with the pelvis stabilized.10 All physical exam findings must be carefully documented at each encounter.1,17

It is critical for the examiner to understand the appropriate technique and potential results when conducting each of these specialized hip exams. A true positive finding is the clunking sensation that occurs with the dislocation or relocation of the affected hip; this finding is better felt than heard. In contrast, a benign hip click with these maneuvers is a more subtle sensation—typically, a soft-tissue snapping or catching—and is not diagnostic of DDH. A click is not a clunk and is not indicative of DDH.1,3

DDH may present later in infancy or early childhood; therefore, DDH should remain within the differential diagnosis for gait asymmetry, unequal hip motion, or limb-length discrepancy. It may be beneficial to continue to evaluate for these developments during routine exams as part of a thorough pediatric musculoskeletal assessment, particularly in patients with documented risk factors for DDH.1,3,4 Delay in diagnosis of DDH, it should be noted, is a relatively common complaint in pediatric medical malpractice lawsuits; until the early 2000s, this condition represented about 75% of claims in one medical malpractice database.The decrease in claims has been attributed to better awareness and earlier diagnosis of DDH. 17

Continue for the diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

A positive Ortolani or Barlow sign is diagnostic and warrants prompt orthopedic referral (Figure 5). If physical examination results are equivocal or inconclusive, follow-up at two weeks is recommended, with continued routine follow-up until walking is achieved. Patients with persistent equivocal findings at the two-week follow-up warrant ultrasound at age 3 to 4 weeks or orthopedic referral. Infants with significant risk factors, particularly breech presentation at birth, should also undergo imaging.18 AAP recommends ultrasound at age 6 weeks or radiograph after 4 months of age.1,18 AAOS recommends performing an imaging study before age 6 months when at least one of the following risk factors is present: breech presentation, positive family history of DDH, or previous clinical instability (moderate level of evidence).3

IMAGING

Ultrasound is the diagnostic test of choice for infants because radiographs have limited value until the femoral heads begin to ossify at age 4 to 6 months.18 Ultrasonography allows for visualization of the cartilaginous portion of the acetabulum and femoral head.1 Dynamic stressing is performed during ultrasound to assess the level of hip stability. A provider trained in ultrasound will measure the depth of the acetabulum and identify any potential laxity or instability of the hip joint. Accuracy of these findings is largely dependent on the experience and skill of the examiner.

Ultrasound evaluation is not recommended until after age 3 to 4 weeks. Earlier findings may include mild laxity and immature morphology of the acetabulum, which often resolve spontaneously.1,18 Use of ultrasound is currently recommended only to confirm diagnostic suspicion, based on clinical findings, or for infants with significant risk factors.18 Universal ultrasound screening in newborns is not recommended and would incur unnecessary costs.1,3,9 Plain radiographs are used after age 4 months to confirm a diagnosis of DDH or to assess for residual dysplasia.3,18

Continue for management >>

MANAGEMENT

Once hip dysplasia is suggested by physical exam or imaging study, the child’s subsequent care should be provided by an orthopedic specialist with experience in treating this condition. Treatment is preferably initiated before age 6 weeks.12 The specifics of treatment are largely based on age at diagnosis and the severity of dysplasia.

The goal of treatment is to maintain the hips in a stable position with the femoral head well covered by the acetabulum. This will improve anatomic development and function. Early clinical diagnosis is often sufficient to justify initiating conservative treatment; additionally, early detection of DDH can considerably reduce the need for surgical intervention.12 Although the potential for spontaneous resolution is high, the consequences associated with delay in care can be significant.

Preferred initial management, which can be initiated before confirmation of DDH by ultrasound, involves implementation of soft abduction support.19 The Pavlik harness is the support design of choice (Figure 6).12 This harness maintains hip flexion and abduction, creating concentric reduction of the femoral head. The brace is highly successful when its use is initiated early. Treatment in a Pavlik harness requires nearly full-time wear and close monitoring by a clinician. Unlikely potential risks associated with this treatment include avascular necrosis and femoral nerve palsy.4

Ultrasonography is used to further monitor treatment and to determine length of wear. Long-term results suggest a success rate exceeding 90%.20,21 However, this rate may be falsely elevated due to the number of hips that likely would have improved spontaneously without treatment.6,19

The Pavlik harness becomes less effective with increasing age, and a more rigid abduction brace may be considered in infants older than 6 months.20 Overall outcomes improve once the femoral head is consistently maintained in the acetabulum. Delay in treatment is associated with an increase in the long-term complications associated with residual hip dysplasia.22

Once an infant is undergoing treatment for DDH in a Pavlik harness, there is no need for primary care providers to continue to perform provocative testing, such as the Ortolani or Barlow test, at routine well-baby checks. Unnecessary stress to the hips is not beneficial, and any new results will not change the treatment being provided by the orthopedic specialist. Adjustments to the fit of the harness should be made only by the orthopedist, unless femoral nerve palsy is noted on exam. This development warrants immediate discontinuation of harness use until symptoms resolve.21

Abduction bracing may not be suitable for all cases of hip dysplasia. Newborns with irreducible hips, more advanced dysplasia, or associated neuromuscular or syndromic disorder may require closed versus open reduction and casting. More invasive surgical options may also be considered in advanced dysplasia in order to reshape the joint and improve function.20,22

Continue for patient education >>

PATIENT EDUCATION

Parents should be fully educated on the options for managing hip dysplasia. Once DDH is diagnosed, prompt referral to an orthopedic specialist is critical in order to weigh the treatment options and to develop the appropriate individualized plan for each child. Once treatment is initiated, parental compliance is essential; frequent meetings between parents and the specialist are important.

Parents of infants with known risk factors for and/or suspicion of hip dysplasia should also be educated on hip-healthy swaddling to allow for free motion of the hips and knees.10,13 Advise them that some commercial baby carriers and slings may maintain the hips in an undesirable extended position. In both swaddling and with baby carriers, care should be taken to allow for hip abduction and flexion. Caution should also be taken during diaper changes to avoid lifting the legs and thereby causing unnecessary stress to the hips.

CONCLUSION

Developmental dysplasia of the hip can be a disabling pediatric condition. Early diagnosis improves the likelihood of successful treatment during infancy and can prevent serious complications. If untreated, DDH can lead to joint degeneration and premature arthritis. Recognition and treatment within the first six weeks of life is crucial to the overall outcome.

The role of a primary care provider is to identify hip dysplasia risk factors and recognize associated physical exam findings in order to refer to an orthopedic specialist in a timely manner. Guidelines from the AAP, POSNA, and AAOS help direct this process in order to effectively identify infants at risk and in need of treatment.

REFERENCES

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Clinical practice guideline: early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 1):896-905.

2. Schwend RM, Schoenecker P, Richards BS, et al. Screening the newborn for developmental dysplasia of the hip: now what do we do? J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):607-610.

3. Mulpuri K, Song KM, Goldberg MJ, Sevarino K. Detection and nonoperative management of pediatric developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants up to six months of age. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(3):202-205.

4. Thomas SRYW. A review of long-term outcomes for late presenting developmental hip dysplasia. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(6):729-733.

5. Loder RT, Skopelja EN. The epidemiology and demographics of hip dysplasia. ISRN Orthop. 2011;2011:238607.

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):898-902.

7. Shorter D, Hong T, Osborn DA. Screening programmes for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD004595.

8. Loder RT, Shafer C. The demographics of developmental hip dysplasia in the Midwestern United States (Indiana). J Child Orthop. 2015;9(1):93-98.

9. Paton RW, Hinduja K, Thomas CD. The significance of at-risk factors in ultrasound surveillance of developmental dysplasia of the hip: a ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1264-1266.

10. Alsaleem M, Set KK, Saadeh L. Developmental dysplasia of hip: a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54(10):921-928.

11. Chan A, McCaul KA, Cundy PJ, et al. Perinatal risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76(2):F94-F100.

12. Godley DR. Assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. JAAPA. 2013;26(3):54-58.

13. Van Sleuwen BE, Engelberts AC, Boere-Boonekamp MM, et al. Swaddling: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1097-e1106.

14. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Position statement: swaddling and developmental hip dysplasia. www.aaos.org/uploadedFiles/PreProduction/About/Opinion_Statements/position/1186%20Swaddling%20and%20Developmental%20Hip%20Dysplasia.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2016.

15. Clarke NM. Swaddling and hip dysplasia: an orthopaedic perspective. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(1):5-6.

16. Storer SK, Skaggs DL. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(8):1310-1316.

17. McAbee GN, Donn SM, Mendelson RA, et al. Medical diagnoses commonly associated with pediatric malpractice lawsuits in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1282-e1286.

18. Imrie M, Scott V, Stearns P, et al. Is ultrasound screening for DDH in babies born breech sufficient? J Child Orthop. 2010;4(1):3-8.

19. Chen HW, Chang CH, Tsai ST, et al. Natural progression of hip dysplasia in newborns: a reflection of hip ultrasonographic screenings in newborn nurseries. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19(5):418-423.

20. Gans I, Flynn JM, Sankar WN. Abduction bracing for residual acetabular dysplasia in infantile DDH. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33(7):714-718.

21. Murnaghan ML, Browne RH, Sucato DJ, Birch J. Femoral nerve palsy in Pavlik harness treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(5):493-499.

22. Dezateux C, Rosendahl K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1541-1552.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Newborn hip evaluation algorithm

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), previously known as congenital dislocation of the hip, follows a spectrum of irregular anatomic hip development spanning from acetabular dysplasia to irreducible dislocation at birth. Early detection is critical to improve the overall prognosis. Prompt diagnosis requires understanding of potential risk factors, proficiency in physical examination techniques, and implementation of appropriate screening tools when indicated. Although current guidelines direct timing for physical exam screenings, imaging, and treatment, it is ultimately up to the provider to determine the best course of action on a case-by-case basis. This article provides a review of these topics and more.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed guidelines for detection of hip dysplasia, including recommendation of relevant physical exam screenings for all newborns.1 In 2007, the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA) encouraged providers to follow the AAP guidelines with a continued recommendation to perform newborn screening for hip instability and routine follow-up evaluations until the child achieves walking.2 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) also established clinical guidelines in 2014 that are endorsed by both AAP and POSNA.3 These guidelines support routine clinical screening; research evaluated infants up to 6 months old, however, limiting the recommendations to that age-group.

Failure to treat DDH early has been associated with serious negative sequelae that include chronic pain, degenerative arthritis, postural scoliosis, and early gait disturbances.4 Primary care providers are expected to perform thorough newborn hip exams with associated specialized tests (ie, Ortolani and Barlow, which are discussed in “Physical exam”) at each routine follow-up. Heightened clinical suspicion and risk factor awareness are key for primary care providers to promptly identify patients requiring orthopedic referral. With early diagnosis, a removable soft abduction brace can be applied as the initial treatment. When treatment is delayed, however, closed reduction under anesthesia or complex surgical intervention may be required.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The etiology for DDH remains unknown. Hip dysplasia typically presents unilaterally but can also occur bilaterally. DDH is more likely to affect the left hip than the right.5

Reported incidence varies, ranging from 0.06 to 76.1 per 1,000 live births, and is largely affected by race and geographic location.5 Incidence is higher in countries where routine screening is required, by either physical examination or ultrasound (1.6 to 28.5 and 34.0 to 60.3 per 1,000, respectively), compared with countries not requiring routine screening (1.3 per 1,000). This may suggest that the majority of hip dysplasia cases are transient and resolve spontaneously without treatment.6,7

RISK FACTORS AND PATIENT HISTORY

Known risk factors for DDH include breech presentation (see Figure 1), positive family history, and female gender.5,8-10 Female infants are eight times more likely than males to develop DDH.10 Firstborn status is also recognized as an associated risk factor, which may be attributable to space constraints in utero. This hypothesis is further supported by the relative DDH-protective effect of prematurity and low birth weight. Other potential risk factors include advanced maternal age, birth weight that is high for gestational age, decreased hip abduction, and joint laxity. However, the majority of patients with hip dysplasia have no identifiable risk factors.3,5,9,11,12