User login

Endologix announces FDA approval of AFX2 Bifurcated Endograft

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the AFX2 Bifurcated Endograft System for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), the device’s manufacturer, Endologix, announced in a statement.

Endologix also touts the AFX2 as a way to facilitate percutaneous endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) by providing low-profile contralateral access through a 7F introducer. The device incorporates Endologix’s ActiveSeal technology, DuraPly expanded polytetrafluoroethylene graft material, and the Vela proximal endograft.

The AFX2 is expected to hit the market in the United States in the first quarter of 2016.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the AFX2 Bifurcated Endograft System for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), the device’s manufacturer, Endologix, announced in a statement.

Endologix also touts the AFX2 as a way to facilitate percutaneous endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) by providing low-profile contralateral access through a 7F introducer. The device incorporates Endologix’s ActiveSeal technology, DuraPly expanded polytetrafluoroethylene graft material, and the Vela proximal endograft.

The AFX2 is expected to hit the market in the United States in the first quarter of 2016.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the AFX2 Bifurcated Endograft System for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), the device’s manufacturer, Endologix, announced in a statement.

Endologix also touts the AFX2 as a way to facilitate percutaneous endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) by providing low-profile contralateral access through a 7F introducer. The device incorporates Endologix’s ActiveSeal technology, DuraPly expanded polytetrafluoroethylene graft material, and the Vela proximal endograft.

The AFX2 is expected to hit the market in the United States in the first quarter of 2016.

White tea

White tea, like green tea, is derived from the plant Camellia sinensis, a member of the Theaceae family and the source of all the globally popular “true tea” beverages.

Of the four main true teas, green and white are unfermented (white is the least processed), black tea is fermented, and oolong tea is semifermented.1,2,3 White tea actually comes from the tips of the green tea leaves or leaves that have not yet fully opened, with buds covered by fine white hair. As a commodity, white tea is more expensive than green tea because it is more difficult to obtain. EGCG [(-)epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate], the most abundant and biologically active polyphenolic catechin found in green tea, is also the constituent in white tea that accounts for its antioxidant properties.4,5 Indeed, white tea is included in topical products for its antioxidant as well as antiseptic activity, and is considered a more potent antioxidant additive medium than green tea.6,1

As an ingredient in a combination formula

White tea is included in the dietary supplement Imedeen Prime Renewal, along with fish protein polysaccharides, vitamins C and E, zinc, and extracts from soy, grape seed, chamomile, and tomato.

In 2006, Skovgaard et al. conducted a 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study on 80 healthy postmenopausal women (38 in the treatment group, 42 in the placebo group completed the study) to determine antiaging effects on the skin. Subjects took 2 tablets of the supplement or placebo twice daily. Clinical, photo, and ultrasound evaluations showed significantly greater improvements in the treatment group, compared with the placebo group, in the face (forehead, periocular, and perioral wrinkles; mottled pigmentation, laxity, sagging, dark circles under the eyes; and overall appearance), hands, and décolletage.7

Antioxidant and antiaging activity

In 2009, Thring et al. studied the antiaging and antioxidant characteristics of 23 plant extracts (from 21 species) by considering antielastase and anticollagenase activities. White tea was found to exhibit the greatest inhibitory activity against both elastase and collagenase, greater than burdock root and angelica in terms of antielastase activity, and greater than green tea, rose tincture, and lavender in relation to anticollagenase activity. The Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity assay also showed that white tea displayed the highest antioxidant activity. The investigators noted the very high phenolic content of white tea in characterizing its potent inhibitory activity against enzymes that accelerate cutaneous aging.6

Earlier in 2009, Camouse et al. examined skin samples from volunteers or skin explants treated with topical white or green tea after ultraviolet exposure to ascertain that the antioxidant could prevent simulated solar radiation–induced damage to DNA and Langerhans cells. They noted that each product displayed a sun protection factor of 1, suggesting that the photoprotection conferred was not due to direct UV absorption. Both forms of topically applied tea extracts were equally effective and judged by the researchers to be potential photoprotective agents when used along with other substantiated approaches to skin protection. These findings provided the first reported evidence of topically applied white tea preventing UV-induced immunosuppression. The researchers further suggested that the color of white tea might render it more cosmetically desirable than green tea.8

It should be noted that a systematic review performed by Hunt et al. in 2010 of MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), and AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) databases up to 2009 identified 11 randomized clinical or controlled clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of botanical extracts for diminishing wrinkling and other signs of cutaneous aging. No significant reductions in wrinkling were associated with the use of green tea or Vitaphenol (a combination of green and white teas, mangosteen, and pomegranate extract). The authors noted, however, that all of the trials that they identified were characterized by poor methodologic quality.9

Thring et al. conducted an in vitro study in 2011 to evaluate the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of white tea, rose, and witch hazel extracts in primary human skin fibroblasts. The investigators measured significant anticollagenase, antielastase, and antioxidant activities for the white tea extracts, which also spurred a significant reduction in the interleukin-8 amount synthesized by fibroblasts, compared with controls. They concluded that white tea (as well as the other extracts) yielded a protective effect on fibroblasts against damage induced by hydrogen peroxide exposure.10

In 2014, Azman et al. used the spin trap method and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to show that among white tea constituents, EGCG and epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG) exhibit the greatest antiradical activity against the methoxy radical.1

Conclusion

Tea is one of the most popular beverages in the world and is touted for its antioxidant and anticancer properties. While the ingredients of green tea polyphenols have inspired a spate of recent research, much is yet to be learned about the potential health benefits of white tea, which is even less processed. Some evidence appears to suggest that white tea may be shown to be more effective overall, and in the dermatologic realm, than green tea. I look forward to seeing more research.

References

1. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(1):5743-8.

2. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(7 Pt 2):873-80.

3. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012:2012:560682.

4. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;206(1-2):125-32.

5. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(11-12):1427-35.

6. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:27.

7. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(10):1201-6.

8. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(6):522-6.

9. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(12):973-85.

10. J Inflamm (Lond). 2011;8(1):27).

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Dermatology News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” was published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera Biopharmaceuticals, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

White tea, like green tea, is derived from the plant Camellia sinensis, a member of the Theaceae family and the source of all the globally popular “true tea” beverages.

Of the four main true teas, green and white are unfermented (white is the least processed), black tea is fermented, and oolong tea is semifermented.1,2,3 White tea actually comes from the tips of the green tea leaves or leaves that have not yet fully opened, with buds covered by fine white hair. As a commodity, white tea is more expensive than green tea because it is more difficult to obtain. EGCG [(-)epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate], the most abundant and biologically active polyphenolic catechin found in green tea, is also the constituent in white tea that accounts for its antioxidant properties.4,5 Indeed, white tea is included in topical products for its antioxidant as well as antiseptic activity, and is considered a more potent antioxidant additive medium than green tea.6,1

As an ingredient in a combination formula

White tea is included in the dietary supplement Imedeen Prime Renewal, along with fish protein polysaccharides, vitamins C and E, zinc, and extracts from soy, grape seed, chamomile, and tomato.

In 2006, Skovgaard et al. conducted a 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study on 80 healthy postmenopausal women (38 in the treatment group, 42 in the placebo group completed the study) to determine antiaging effects on the skin. Subjects took 2 tablets of the supplement or placebo twice daily. Clinical, photo, and ultrasound evaluations showed significantly greater improvements in the treatment group, compared with the placebo group, in the face (forehead, periocular, and perioral wrinkles; mottled pigmentation, laxity, sagging, dark circles under the eyes; and overall appearance), hands, and décolletage.7

Antioxidant and antiaging activity

In 2009, Thring et al. studied the antiaging and antioxidant characteristics of 23 plant extracts (from 21 species) by considering antielastase and anticollagenase activities. White tea was found to exhibit the greatest inhibitory activity against both elastase and collagenase, greater than burdock root and angelica in terms of antielastase activity, and greater than green tea, rose tincture, and lavender in relation to anticollagenase activity. The Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity assay also showed that white tea displayed the highest antioxidant activity. The investigators noted the very high phenolic content of white tea in characterizing its potent inhibitory activity against enzymes that accelerate cutaneous aging.6

Earlier in 2009, Camouse et al. examined skin samples from volunteers or skin explants treated with topical white or green tea after ultraviolet exposure to ascertain that the antioxidant could prevent simulated solar radiation–induced damage to DNA and Langerhans cells. They noted that each product displayed a sun protection factor of 1, suggesting that the photoprotection conferred was not due to direct UV absorption. Both forms of topically applied tea extracts were equally effective and judged by the researchers to be potential photoprotective agents when used along with other substantiated approaches to skin protection. These findings provided the first reported evidence of topically applied white tea preventing UV-induced immunosuppression. The researchers further suggested that the color of white tea might render it more cosmetically desirable than green tea.8

It should be noted that a systematic review performed by Hunt et al. in 2010 of MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), and AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) databases up to 2009 identified 11 randomized clinical or controlled clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of botanical extracts for diminishing wrinkling and other signs of cutaneous aging. No significant reductions in wrinkling were associated with the use of green tea or Vitaphenol (a combination of green and white teas, mangosteen, and pomegranate extract). The authors noted, however, that all of the trials that they identified were characterized by poor methodologic quality.9

Thring et al. conducted an in vitro study in 2011 to evaluate the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of white tea, rose, and witch hazel extracts in primary human skin fibroblasts. The investigators measured significant anticollagenase, antielastase, and antioxidant activities for the white tea extracts, which also spurred a significant reduction in the interleukin-8 amount synthesized by fibroblasts, compared with controls. They concluded that white tea (as well as the other extracts) yielded a protective effect on fibroblasts against damage induced by hydrogen peroxide exposure.10

In 2014, Azman et al. used the spin trap method and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to show that among white tea constituents, EGCG and epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG) exhibit the greatest antiradical activity against the methoxy radical.1

Conclusion

Tea is one of the most popular beverages in the world and is touted for its antioxidant and anticancer properties. While the ingredients of green tea polyphenols have inspired a spate of recent research, much is yet to be learned about the potential health benefits of white tea, which is even less processed. Some evidence appears to suggest that white tea may be shown to be more effective overall, and in the dermatologic realm, than green tea. I look forward to seeing more research.

References

1. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(1):5743-8.

2. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(7 Pt 2):873-80.

3. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012:2012:560682.

4. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;206(1-2):125-32.

5. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(11-12):1427-35.

6. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:27.

7. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(10):1201-6.

8. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(6):522-6.

9. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(12):973-85.

10. J Inflamm (Lond). 2011;8(1):27).

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Dermatology News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” was published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera Biopharmaceuticals, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

White tea, like green tea, is derived from the plant Camellia sinensis, a member of the Theaceae family and the source of all the globally popular “true tea” beverages.

Of the four main true teas, green and white are unfermented (white is the least processed), black tea is fermented, and oolong tea is semifermented.1,2,3 White tea actually comes from the tips of the green tea leaves or leaves that have not yet fully opened, with buds covered by fine white hair. As a commodity, white tea is more expensive than green tea because it is more difficult to obtain. EGCG [(-)epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate], the most abundant and biologically active polyphenolic catechin found in green tea, is also the constituent in white tea that accounts for its antioxidant properties.4,5 Indeed, white tea is included in topical products for its antioxidant as well as antiseptic activity, and is considered a more potent antioxidant additive medium than green tea.6,1

As an ingredient in a combination formula

White tea is included in the dietary supplement Imedeen Prime Renewal, along with fish protein polysaccharides, vitamins C and E, zinc, and extracts from soy, grape seed, chamomile, and tomato.

In 2006, Skovgaard et al. conducted a 6-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study on 80 healthy postmenopausal women (38 in the treatment group, 42 in the placebo group completed the study) to determine antiaging effects on the skin. Subjects took 2 tablets of the supplement or placebo twice daily. Clinical, photo, and ultrasound evaluations showed significantly greater improvements in the treatment group, compared with the placebo group, in the face (forehead, periocular, and perioral wrinkles; mottled pigmentation, laxity, sagging, dark circles under the eyes; and overall appearance), hands, and décolletage.7

Antioxidant and antiaging activity

In 2009, Thring et al. studied the antiaging and antioxidant characteristics of 23 plant extracts (from 21 species) by considering antielastase and anticollagenase activities. White tea was found to exhibit the greatest inhibitory activity against both elastase and collagenase, greater than burdock root and angelica in terms of antielastase activity, and greater than green tea, rose tincture, and lavender in relation to anticollagenase activity. The Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity assay also showed that white tea displayed the highest antioxidant activity. The investigators noted the very high phenolic content of white tea in characterizing its potent inhibitory activity against enzymes that accelerate cutaneous aging.6

Earlier in 2009, Camouse et al. examined skin samples from volunteers or skin explants treated with topical white or green tea after ultraviolet exposure to ascertain that the antioxidant could prevent simulated solar radiation–induced damage to DNA and Langerhans cells. They noted that each product displayed a sun protection factor of 1, suggesting that the photoprotection conferred was not due to direct UV absorption. Both forms of topically applied tea extracts were equally effective and judged by the researchers to be potential photoprotective agents when used along with other substantiated approaches to skin protection. These findings provided the first reported evidence of topically applied white tea preventing UV-induced immunosuppression. The researchers further suggested that the color of white tea might render it more cosmetically desirable than green tea.8

It should be noted that a systematic review performed by Hunt et al. in 2010 of MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), and AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) databases up to 2009 identified 11 randomized clinical or controlled clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of botanical extracts for diminishing wrinkling and other signs of cutaneous aging. No significant reductions in wrinkling were associated with the use of green tea or Vitaphenol (a combination of green and white teas, mangosteen, and pomegranate extract). The authors noted, however, that all of the trials that they identified were characterized by poor methodologic quality.9

Thring et al. conducted an in vitro study in 2011 to evaluate the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of white tea, rose, and witch hazel extracts in primary human skin fibroblasts. The investigators measured significant anticollagenase, antielastase, and antioxidant activities for the white tea extracts, which also spurred a significant reduction in the interleukin-8 amount synthesized by fibroblasts, compared with controls. They concluded that white tea (as well as the other extracts) yielded a protective effect on fibroblasts against damage induced by hydrogen peroxide exposure.10

In 2014, Azman et al. used the spin trap method and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy to show that among white tea constituents, EGCG and epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG) exhibit the greatest antiradical activity against the methoxy radical.1

Conclusion

Tea is one of the most popular beverages in the world and is touted for its antioxidant and anticancer properties. While the ingredients of green tea polyphenols have inspired a spate of recent research, much is yet to be learned about the potential health benefits of white tea, which is even less processed. Some evidence appears to suggest that white tea may be shown to be more effective overall, and in the dermatologic realm, than green tea. I look forward to seeing more research.

References

1. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(1):5743-8.

2. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(7 Pt 2):873-80.

3. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012:2012:560682.

4. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;206(1-2):125-32.

5. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(11-12):1427-35.

6. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:27.

7. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(10):1201-6.

8. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(6):522-6.

9. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(12):973-85.

10. J Inflamm (Lond). 2011;8(1):27).

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in the Design District in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Dermatology News since January 2001. Her latest book, “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” was published in November 2014. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Evolus, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Kythera Biopharmaceuticals, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

BMI negatively associated with acne lesion counts in postadolescent women

Body mass index was negatively associated with the number of acne lesions in a study of Taiwanese women, report Dr. P.H. Lu and coauthors at National Yang-Ming University in Taipei, Taiwan.

A study of 104 Taiwanese women aged 25-45 years with moderate to severe postadolescent acne vulgaris found a negative association between body mass index (BMI) and acne lesion count (P = .001).

In addition to BMI, other recorded measurements included blood pressure, fasting glucose, triglyceride levels, cholesterol levels, waist circumference, and hip circumference. Subjects were classified into four categories: BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2, BMI of 18.5 kg/m2–23.9 kg/m2, BMI of 24 kg/m2–26.9 kg/m2), or BMI greater than or equal to 27.

Acne severity was determined by the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA), with inclusion criteria being a score of 3 or 4 on a scale of 0 to 5. Inflammatory lesion counts were recorded by counting papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts. Noninflammatory lesions were recorded by counting comedones.

Women in the lowest BMI category had a mean of 35.5 inflammatory lesions, 7.4 noninflammatory lesions, and 42.9 total lesions, compared with patients in the 18.5-23.9 range (27.9 inflammatory, 6.6 noninflammatory, 34.0 total), and those who were in the two higher categories (18.1 inflammatory, 4.4 noninflammatory, 22.0 total), the authors reported.

“Further investigation is warranted into the association between BMI and acne in this subset of women,” Dr. Lu and associates concluded.

Read the full study in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Body mass index was negatively associated with the number of acne lesions in a study of Taiwanese women, report Dr. P.H. Lu and coauthors at National Yang-Ming University in Taipei, Taiwan.

A study of 104 Taiwanese women aged 25-45 years with moderate to severe postadolescent acne vulgaris found a negative association between body mass index (BMI) and acne lesion count (P = .001).

In addition to BMI, other recorded measurements included blood pressure, fasting glucose, triglyceride levels, cholesterol levels, waist circumference, and hip circumference. Subjects were classified into four categories: BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2, BMI of 18.5 kg/m2–23.9 kg/m2, BMI of 24 kg/m2–26.9 kg/m2), or BMI greater than or equal to 27.

Acne severity was determined by the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA), with inclusion criteria being a score of 3 or 4 on a scale of 0 to 5. Inflammatory lesion counts were recorded by counting papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts. Noninflammatory lesions were recorded by counting comedones.

Women in the lowest BMI category had a mean of 35.5 inflammatory lesions, 7.4 noninflammatory lesions, and 42.9 total lesions, compared with patients in the 18.5-23.9 range (27.9 inflammatory, 6.6 noninflammatory, 34.0 total), and those who were in the two higher categories (18.1 inflammatory, 4.4 noninflammatory, 22.0 total), the authors reported.

“Further investigation is warranted into the association between BMI and acne in this subset of women,” Dr. Lu and associates concluded.

Read the full study in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Body mass index was negatively associated with the number of acne lesions in a study of Taiwanese women, report Dr. P.H. Lu and coauthors at National Yang-Ming University in Taipei, Taiwan.

A study of 104 Taiwanese women aged 25-45 years with moderate to severe postadolescent acne vulgaris found a negative association between body mass index (BMI) and acne lesion count (P = .001).

In addition to BMI, other recorded measurements included blood pressure, fasting glucose, triglyceride levels, cholesterol levels, waist circumference, and hip circumference. Subjects were classified into four categories: BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2, BMI of 18.5 kg/m2–23.9 kg/m2, BMI of 24 kg/m2–26.9 kg/m2), or BMI greater than or equal to 27.

Acne severity was determined by the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA), with inclusion criteria being a score of 3 or 4 on a scale of 0 to 5. Inflammatory lesion counts were recorded by counting papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts. Noninflammatory lesions were recorded by counting comedones.

Women in the lowest BMI category had a mean of 35.5 inflammatory lesions, 7.4 noninflammatory lesions, and 42.9 total lesions, compared with patients in the 18.5-23.9 range (27.9 inflammatory, 6.6 noninflammatory, 34.0 total), and those who were in the two higher categories (18.1 inflammatory, 4.4 noninflammatory, 22.0 total), the authors reported.

“Further investigation is warranted into the association between BMI and acne in this subset of women,” Dr. Lu and associates concluded.

Read the full study in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Health Canada approves drug for acquired hemophilia A

Photo courtesy of

Baxter International Inc.

Health Canada has approved a recombinant porcine factor VIII (FVIII) product (Obizur) to treat bleeding episodes in patients with acquired hemophilia A caused by autoantibodies to FVIII.

Obizur is the first recombinant porcine treatment to be made available for acquired hemophilia A in Canada.

It is specifically designed so physicians can monitor treatment response by measuring FVIII activity levels in addition to making clinical assessments.

Health Canada’s approval is based on a phase 2/3 trial in which patients with acquired hemophilia A received Obizur as treatment for serious bleeding episodes.

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled in this trial and evaluated for safety. Researchers determined that one of the patients did not actually have acquired hemophilia A, so this patient could not be evaluated for efficacy.

At 24 hours after the initial infusion, all 28 patients in the efficacy analysis had a positive response to Obizur. This meant that bleeding stopped or decreased, the patients experienced clinical stabilization or improvement, and FVIII levels were 20% or higher.

Eighty-six percent of patients (24/28) had successful treatment of their initial bleeding episode. The overall treatment success was determined by the investigator based on the ability to discontinue or reduce the dose and/or dosing frequency of Obizur.

The adverse event most frequently reported in the 29 patients in the safety analysis was the development of inhibitors to porcine FVIII.

Nineteen patients were negative for anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, and 5 of these patients (26%) developed anti-porcine FVIII antibodies following exposure to Obizur.

Of the 10 patients with detectable anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, 2 (20%) experienced an increase in titer, and 8 (80%) decreased to a non-detectable titer.

Obizur is under development by Baxalta Incorporated. The drug is currently approved for use in the US and is under regulatory review in the European Union, Switzerland, Australia, and Colombia. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Baxter International Inc.

Health Canada has approved a recombinant porcine factor VIII (FVIII) product (Obizur) to treat bleeding episodes in patients with acquired hemophilia A caused by autoantibodies to FVIII.

Obizur is the first recombinant porcine treatment to be made available for acquired hemophilia A in Canada.

It is specifically designed so physicians can monitor treatment response by measuring FVIII activity levels in addition to making clinical assessments.

Health Canada’s approval is based on a phase 2/3 trial in which patients with acquired hemophilia A received Obizur as treatment for serious bleeding episodes.

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled in this trial and evaluated for safety. Researchers determined that one of the patients did not actually have acquired hemophilia A, so this patient could not be evaluated for efficacy.

At 24 hours after the initial infusion, all 28 patients in the efficacy analysis had a positive response to Obizur. This meant that bleeding stopped or decreased, the patients experienced clinical stabilization or improvement, and FVIII levels were 20% or higher.

Eighty-six percent of patients (24/28) had successful treatment of their initial bleeding episode. The overall treatment success was determined by the investigator based on the ability to discontinue or reduce the dose and/or dosing frequency of Obizur.

The adverse event most frequently reported in the 29 patients in the safety analysis was the development of inhibitors to porcine FVIII.

Nineteen patients were negative for anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, and 5 of these patients (26%) developed anti-porcine FVIII antibodies following exposure to Obizur.

Of the 10 patients with detectable anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, 2 (20%) experienced an increase in titer, and 8 (80%) decreased to a non-detectable titer.

Obizur is under development by Baxalta Incorporated. The drug is currently approved for use in the US and is under regulatory review in the European Union, Switzerland, Australia, and Colombia. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Baxter International Inc.

Health Canada has approved a recombinant porcine factor VIII (FVIII) product (Obizur) to treat bleeding episodes in patients with acquired hemophilia A caused by autoantibodies to FVIII.

Obizur is the first recombinant porcine treatment to be made available for acquired hemophilia A in Canada.

It is specifically designed so physicians can monitor treatment response by measuring FVIII activity levels in addition to making clinical assessments.

Health Canada’s approval is based on a phase 2/3 trial in which patients with acquired hemophilia A received Obizur as treatment for serious bleeding episodes.

Twenty-nine patients were enrolled in this trial and evaluated for safety. Researchers determined that one of the patients did not actually have acquired hemophilia A, so this patient could not be evaluated for efficacy.

At 24 hours after the initial infusion, all 28 patients in the efficacy analysis had a positive response to Obizur. This meant that bleeding stopped or decreased, the patients experienced clinical stabilization or improvement, and FVIII levels were 20% or higher.

Eighty-six percent of patients (24/28) had successful treatment of their initial bleeding episode. The overall treatment success was determined by the investigator based on the ability to discontinue or reduce the dose and/or dosing frequency of Obizur.

The adverse event most frequently reported in the 29 patients in the safety analysis was the development of inhibitors to porcine FVIII.

Nineteen patients were negative for anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, and 5 of these patients (26%) developed anti-porcine FVIII antibodies following exposure to Obizur.

Of the 10 patients with detectable anti-porcine FVIII antibodies at baseline, 2 (20%) experienced an increase in titer, and 8 (80%) decreased to a non-detectable titer.

Obizur is under development by Baxalta Incorporated. The drug is currently approved for use in the US and is under regulatory review in the European Union, Switzerland, Australia, and Colombia. ![]()

COMP recommends orphan designations for KTE-C19

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) has adopted positive opinions recommending orphan designation for KTE-C19 to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma.

KTE-C19 is an investigational chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy designed to target CD19, a protein expressed on the surface of B cells.

The CAR T-cell therapy already has orphan designation for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the US and the European Union (EU).

KTE-C19 also has COMP positive opinions for orphan designation in the EU for primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma.

About orphan designation

The COMP adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for endorsement.

In the EU, orphan designation is granted to therapies intended to treat a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition that affects no more than 5 in 10,000 persons and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Companies that obtain orphan designation for a drug benefit from a number of incentives, including protocol assistance, a type of scientific advice specific for designated orphan medicines, and 10 years of market exclusivity once the medicine is approved. Fee reductions are also available, depending on the status of the sponsor and the type of service required.

KTE-C19 research

Last year, researchers reported results with KTE-C19 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The study included 15 patients with advanced B-cell malignancies.

The patients received a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine, followed 1 day later by a single infusion of the CAR T-cell therapy. The researchers noted that the conditioning regimen is known to be active against B-cell malignancies and could have made a direct contribution to patient responses.

Thirteen patients were evaluable for response. Eight patients achieved a complete response (CR), and 4 had a partial response (PR).

Of the 7 patients with chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 4 achieved a CR, 2 achieved a PR, and 1 had stable disease. Of the 4 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 3 had a CR, and 1 had a PR. Among the 2 patients with indolent lymphomas, 1 achieved a CR, and 1 had a PR.

KTE-C19 was associated with fever, low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits, and delirium. Toxicities largely occurred in the first 2 weeks after infusion.

All but 2 patients experienced grade 3/4 adverse events. Four patients had grade 3/4 hypotension.

All patients had elevations in serum interferon gamma and/or interleukin 6 around the time of peak toxicity, but most did not develop elevations in serum tumor necrosis factor.

Neurologic toxicities included confusion and obtundation, which have been reported in previous studies. However, 3 patients developed unexpected neurologic abnormalities.

KTE-C19 is currently under investigation in a phase 1/2 trial (ZUMA-1) of patients with refractory, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Kite Pharma, Inc., the company developing KTE-C19, plans to present top-line phase 1 data at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) has adopted positive opinions recommending orphan designation for KTE-C19 to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma.

KTE-C19 is an investigational chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy designed to target CD19, a protein expressed on the surface of B cells.

The CAR T-cell therapy already has orphan designation for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the US and the European Union (EU).

KTE-C19 also has COMP positive opinions for orphan designation in the EU for primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma.

About orphan designation

The COMP adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for endorsement.

In the EU, orphan designation is granted to therapies intended to treat a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition that affects no more than 5 in 10,000 persons and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Companies that obtain orphan designation for a drug benefit from a number of incentives, including protocol assistance, a type of scientific advice specific for designated orphan medicines, and 10 years of market exclusivity once the medicine is approved. Fee reductions are also available, depending on the status of the sponsor and the type of service required.

KTE-C19 research

Last year, researchers reported results with KTE-C19 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The study included 15 patients with advanced B-cell malignancies.

The patients received a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine, followed 1 day later by a single infusion of the CAR T-cell therapy. The researchers noted that the conditioning regimen is known to be active against B-cell malignancies and could have made a direct contribution to patient responses.

Thirteen patients were evaluable for response. Eight patients achieved a complete response (CR), and 4 had a partial response (PR).

Of the 7 patients with chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 4 achieved a CR, 2 achieved a PR, and 1 had stable disease. Of the 4 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 3 had a CR, and 1 had a PR. Among the 2 patients with indolent lymphomas, 1 achieved a CR, and 1 had a PR.

KTE-C19 was associated with fever, low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits, and delirium. Toxicities largely occurred in the first 2 weeks after infusion.

All but 2 patients experienced grade 3/4 adverse events. Four patients had grade 3/4 hypotension.

All patients had elevations in serum interferon gamma and/or interleukin 6 around the time of peak toxicity, but most did not develop elevations in serum tumor necrosis factor.

Neurologic toxicities included confusion and obtundation, which have been reported in previous studies. However, 3 patients developed unexpected neurologic abnormalities.

KTE-C19 is currently under investigation in a phase 1/2 trial (ZUMA-1) of patients with refractory, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Kite Pharma, Inc., the company developing KTE-C19, plans to present top-line phase 1 data at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP) has adopted positive opinions recommending orphan designation for KTE-C19 to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma.

KTE-C19 is an investigational chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy designed to target CD19, a protein expressed on the surface of B cells.

The CAR T-cell therapy already has orphan designation for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the US and the European Union (EU).

KTE-C19 also has COMP positive opinions for orphan designation in the EU for primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma.

About orphan designation

The COMP adopts an opinion on the granting of orphan designation, and that opinion is submitted to the European Commission for endorsement.

In the EU, orphan designation is granted to therapies intended to treat a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition that affects no more than 5 in 10,000 persons and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Companies that obtain orphan designation for a drug benefit from a number of incentives, including protocol assistance, a type of scientific advice specific for designated orphan medicines, and 10 years of market exclusivity once the medicine is approved. Fee reductions are also available, depending on the status of the sponsor and the type of service required.

KTE-C19 research

Last year, researchers reported results with KTE-C19 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The study included 15 patients with advanced B-cell malignancies.

The patients received a conditioning regimen of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine, followed 1 day later by a single infusion of the CAR T-cell therapy. The researchers noted that the conditioning regimen is known to be active against B-cell malignancies and could have made a direct contribution to patient responses.

Thirteen patients were evaluable for response. Eight patients achieved a complete response (CR), and 4 had a partial response (PR).

Of the 7 patients with chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 4 achieved a CR, 2 achieved a PR, and 1 had stable disease. Of the 4 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 3 had a CR, and 1 had a PR. Among the 2 patients with indolent lymphomas, 1 achieved a CR, and 1 had a PR.

KTE-C19 was associated with fever, low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits, and delirium. Toxicities largely occurred in the first 2 weeks after infusion.

All but 2 patients experienced grade 3/4 adverse events. Four patients had grade 3/4 hypotension.

All patients had elevations in serum interferon gamma and/or interleukin 6 around the time of peak toxicity, but most did not develop elevations in serum tumor necrosis factor.

Neurologic toxicities included confusion and obtundation, which have been reported in previous studies. However, 3 patients developed unexpected neurologic abnormalities.

KTE-C19 is currently under investigation in a phase 1/2 trial (ZUMA-1) of patients with refractory, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Kite Pharma, Inc., the company developing KTE-C19, plans to present top-line phase 1 data at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting. ![]()

Watchdog condemns FDA oversight of dabigatran

The US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) oversight of the oral anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) raises questions about the agency’s reliability, according to a report by the Project On Government Oversight (POGO).

POGO’s report describes a series of “questionable” calls the FDA has made in its oversight of dabigatran.

The report calls attention to issues with the clinical trial used to support dabigatran’s approval.

It also details concerns regarding FDA advisory committee members, the distribution of potentially misleading information about dabigatran, the possibility that patients receiving dabigatran may actually need to be monitored, and other issues.

“The deeply disturbing part is that the public has to trust the FDA to keep it safe, and the way the agency handled Pradaxa doesn’t inspire confidence,” said Daniel Brian, POGO’s executive director.

This is not the first time the safety of dabigatran and results of dabigatran trials have been called into question.

Following post-marketing reports of adverse events and deaths related to dabigatran, the FDA conducted its own studies investigating the drug’s safety. The agency ultimately concluded that dabigatran’s benefits outweigh any detriments.

Still, a paper published in JAMA in 2012 suggested the FDA may have approved dabigatran too soon.

And several papers published in The BMJ last year indicated that Boehringer Ingelheim, the company developing dabigatran, underreported events associated with the drug and withheld data showing that monitoring and dose adjustment could improve the safety of dabigatran without compromising its efficacy.

The company has denied these allegations, but POGO’s report appears to support these claims, in addition to raising other concerns.

Trial issues

Dabigatran was initially approved by the FDA in 2010 on the basis of the RE-LY trial, in which researchers compared dabigatran and warfarin.

POGO’s report notes that this was an unblinded trial and suggests that investigators treated patients in the dabigatran arm differently than those in the warfarin arm. An FDA review showed that, when study subjects showed “signs of trouble,” those in the dabigatran arm were more likely to stop receiving treatment. This may have prevented adverse events such as hemorrhagic strokes.

FDA inspections also revealed that RE-LY investigators mismanaged parts of the trial. For example, they enrolled patients who were supposed to be excluded and failed to promptly inform Boehringer Ingelheim about possible adverse effects of dabigatran, among other infractions.

POGO’s report also cites FDA documents showing that the agency allowed Boehringer Ingelheim to finalize the scoring system for the RE-LY trial after it was over and the data had been gathered. A subsequent FDA review suggested that this allowance worked in dabigatran’s favor.

Advisory committee concerns

POGO’s report points out that members of the committee that advised the FDA on dabigatran’s approval have financial ties to the drug’s maker.

According to public databases, 2 of the advisory committee members who voted to approve dabigatran went on to receive tens of thousands of dollars from Boehringer Ingelheim.

POGO also found that when Boehringer Ingelheim held a practice session to prepare for questioning by the FDA advisory committee, a former member and a former chairman of that committee were paid to play roles in the rehearsal.

‘Misleading’ information

Another of POGO’s concerns is that the FDA redacted information from a public memo announcing and explaining its decision to approve dabigatran. The deleted section said that patients who were well-treated using warfarin had no reason to switch to dabigatran.

POGO’s report also points out that the FDA initially refused to allow Boehringer Ingelheim to claim that dabigatran was superior to warfarin but later changed its mind without providing much explanation.

In addition, the FDA allowed Boehringer Ingelheim to advertise that, in a clinical trial, dabigatran “reduced stroke risk 35% more than warfarin.” But after dabigatran had been on the market for more than 2.5 years, the FDA decided this claim was misleading.

The agency told Boehringer Ingelheim to add the following clarification: “That means that, in a large clinical study, 3.4% of patients taking warfarin had a stroke, compared to 2.2% of patients taking Pradaxa.” So, in absolute terms, the difference between the drugs was 1.2%.

Potential need for monitoring

According to POGO, Boehringer Ingelheim has been the target of thousands of lawsuits regarding adverse events and deaths thought to be related to dabigatran. In 2013, Boehringer Ingelheim was fined by a federal judge for withholding or failing to preserve records.

Some of these documents suggested that patients taking dabigatran may require monitoring to ensure they remain within a therapeutic range. A scientist at Boehringer Ingelheim, Thorsten Lehr, drafted a paper concluding that there is a therapeutic range for dabigatran.

But company emails indicated that other employees were against publishing this paper. An email from Boehringer Ingelheim’s Jutta Heinrich-Nols said publishing the paper would “make any defense of no monitoring . . . extremely difficult . . . and undermine our efforts to compete” with other new anticoagulants.

For more details, see POGO’s full report. POGO is a nonpartisan, independent watchdog that champions government reform. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) oversight of the oral anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) raises questions about the agency’s reliability, according to a report by the Project On Government Oversight (POGO).

POGO’s report describes a series of “questionable” calls the FDA has made in its oversight of dabigatran.

The report calls attention to issues with the clinical trial used to support dabigatran’s approval.

It also details concerns regarding FDA advisory committee members, the distribution of potentially misleading information about dabigatran, the possibility that patients receiving dabigatran may actually need to be monitored, and other issues.

“The deeply disturbing part is that the public has to trust the FDA to keep it safe, and the way the agency handled Pradaxa doesn’t inspire confidence,” said Daniel Brian, POGO’s executive director.

This is not the first time the safety of dabigatran and results of dabigatran trials have been called into question.

Following post-marketing reports of adverse events and deaths related to dabigatran, the FDA conducted its own studies investigating the drug’s safety. The agency ultimately concluded that dabigatran’s benefits outweigh any detriments.

Still, a paper published in JAMA in 2012 suggested the FDA may have approved dabigatran too soon.

And several papers published in The BMJ last year indicated that Boehringer Ingelheim, the company developing dabigatran, underreported events associated with the drug and withheld data showing that monitoring and dose adjustment could improve the safety of dabigatran without compromising its efficacy.

The company has denied these allegations, but POGO’s report appears to support these claims, in addition to raising other concerns.

Trial issues

Dabigatran was initially approved by the FDA in 2010 on the basis of the RE-LY trial, in which researchers compared dabigatran and warfarin.

POGO’s report notes that this was an unblinded trial and suggests that investigators treated patients in the dabigatran arm differently than those in the warfarin arm. An FDA review showed that, when study subjects showed “signs of trouble,” those in the dabigatran arm were more likely to stop receiving treatment. This may have prevented adverse events such as hemorrhagic strokes.

FDA inspections also revealed that RE-LY investigators mismanaged parts of the trial. For example, they enrolled patients who were supposed to be excluded and failed to promptly inform Boehringer Ingelheim about possible adverse effects of dabigatran, among other infractions.

POGO’s report also cites FDA documents showing that the agency allowed Boehringer Ingelheim to finalize the scoring system for the RE-LY trial after it was over and the data had been gathered. A subsequent FDA review suggested that this allowance worked in dabigatran’s favor.

Advisory committee concerns

POGO’s report points out that members of the committee that advised the FDA on dabigatran’s approval have financial ties to the drug’s maker.

According to public databases, 2 of the advisory committee members who voted to approve dabigatran went on to receive tens of thousands of dollars from Boehringer Ingelheim.

POGO also found that when Boehringer Ingelheim held a practice session to prepare for questioning by the FDA advisory committee, a former member and a former chairman of that committee were paid to play roles in the rehearsal.

‘Misleading’ information

Another of POGO’s concerns is that the FDA redacted information from a public memo announcing and explaining its decision to approve dabigatran. The deleted section said that patients who were well-treated using warfarin had no reason to switch to dabigatran.

POGO’s report also points out that the FDA initially refused to allow Boehringer Ingelheim to claim that dabigatran was superior to warfarin but later changed its mind without providing much explanation.

In addition, the FDA allowed Boehringer Ingelheim to advertise that, in a clinical trial, dabigatran “reduced stroke risk 35% more than warfarin.” But after dabigatran had been on the market for more than 2.5 years, the FDA decided this claim was misleading.

The agency told Boehringer Ingelheim to add the following clarification: “That means that, in a large clinical study, 3.4% of patients taking warfarin had a stroke, compared to 2.2% of patients taking Pradaxa.” So, in absolute terms, the difference between the drugs was 1.2%.

Potential need for monitoring

According to POGO, Boehringer Ingelheim has been the target of thousands of lawsuits regarding adverse events and deaths thought to be related to dabigatran. In 2013, Boehringer Ingelheim was fined by a federal judge for withholding or failing to preserve records.

Some of these documents suggested that patients taking dabigatran may require monitoring to ensure they remain within a therapeutic range. A scientist at Boehringer Ingelheim, Thorsten Lehr, drafted a paper concluding that there is a therapeutic range for dabigatran.

But company emails indicated that other employees were against publishing this paper. An email from Boehringer Ingelheim’s Jutta Heinrich-Nols said publishing the paper would “make any defense of no monitoring . . . extremely difficult . . . and undermine our efforts to compete” with other new anticoagulants.

For more details, see POGO’s full report. POGO is a nonpartisan, independent watchdog that champions government reform. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) oversight of the oral anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa) raises questions about the agency’s reliability, according to a report by the Project On Government Oversight (POGO).

POGO’s report describes a series of “questionable” calls the FDA has made in its oversight of dabigatran.

The report calls attention to issues with the clinical trial used to support dabigatran’s approval.

It also details concerns regarding FDA advisory committee members, the distribution of potentially misleading information about dabigatran, the possibility that patients receiving dabigatran may actually need to be monitored, and other issues.

“The deeply disturbing part is that the public has to trust the FDA to keep it safe, and the way the agency handled Pradaxa doesn’t inspire confidence,” said Daniel Brian, POGO’s executive director.

This is not the first time the safety of dabigatran and results of dabigatran trials have been called into question.

Following post-marketing reports of adverse events and deaths related to dabigatran, the FDA conducted its own studies investigating the drug’s safety. The agency ultimately concluded that dabigatran’s benefits outweigh any detriments.

Still, a paper published in JAMA in 2012 suggested the FDA may have approved dabigatran too soon.

And several papers published in The BMJ last year indicated that Boehringer Ingelheim, the company developing dabigatran, underreported events associated with the drug and withheld data showing that monitoring and dose adjustment could improve the safety of dabigatran without compromising its efficacy.

The company has denied these allegations, but POGO’s report appears to support these claims, in addition to raising other concerns.

Trial issues

Dabigatran was initially approved by the FDA in 2010 on the basis of the RE-LY trial, in which researchers compared dabigatran and warfarin.

POGO’s report notes that this was an unblinded trial and suggests that investigators treated patients in the dabigatran arm differently than those in the warfarin arm. An FDA review showed that, when study subjects showed “signs of trouble,” those in the dabigatran arm were more likely to stop receiving treatment. This may have prevented adverse events such as hemorrhagic strokes.

FDA inspections also revealed that RE-LY investigators mismanaged parts of the trial. For example, they enrolled patients who were supposed to be excluded and failed to promptly inform Boehringer Ingelheim about possible adverse effects of dabigatran, among other infractions.

POGO’s report also cites FDA documents showing that the agency allowed Boehringer Ingelheim to finalize the scoring system for the RE-LY trial after it was over and the data had been gathered. A subsequent FDA review suggested that this allowance worked in dabigatran’s favor.

Advisory committee concerns

POGO’s report points out that members of the committee that advised the FDA on dabigatran’s approval have financial ties to the drug’s maker.

According to public databases, 2 of the advisory committee members who voted to approve dabigatran went on to receive tens of thousands of dollars from Boehringer Ingelheim.

POGO also found that when Boehringer Ingelheim held a practice session to prepare for questioning by the FDA advisory committee, a former member and a former chairman of that committee were paid to play roles in the rehearsal.

‘Misleading’ information

Another of POGO’s concerns is that the FDA redacted information from a public memo announcing and explaining its decision to approve dabigatran. The deleted section said that patients who were well-treated using warfarin had no reason to switch to dabigatran.

POGO’s report also points out that the FDA initially refused to allow Boehringer Ingelheim to claim that dabigatran was superior to warfarin but later changed its mind without providing much explanation.

In addition, the FDA allowed Boehringer Ingelheim to advertise that, in a clinical trial, dabigatran “reduced stroke risk 35% more than warfarin.” But after dabigatran had been on the market for more than 2.5 years, the FDA decided this claim was misleading.

The agency told Boehringer Ingelheim to add the following clarification: “That means that, in a large clinical study, 3.4% of patients taking warfarin had a stroke, compared to 2.2% of patients taking Pradaxa.” So, in absolute terms, the difference between the drugs was 1.2%.

Potential need for monitoring

According to POGO, Boehringer Ingelheim has been the target of thousands of lawsuits regarding adverse events and deaths thought to be related to dabigatran. In 2013, Boehringer Ingelheim was fined by a federal judge for withholding or failing to preserve records.

Some of these documents suggested that patients taking dabigatran may require monitoring to ensure they remain within a therapeutic range. A scientist at Boehringer Ingelheim, Thorsten Lehr, drafted a paper concluding that there is a therapeutic range for dabigatran.

But company emails indicated that other employees were against publishing this paper. An email from Boehringer Ingelheim’s Jutta Heinrich-Nols said publishing the paper would “make any defense of no monitoring . . . extremely difficult . . . and undermine our efforts to compete” with other new anticoagulants.

For more details, see POGO’s full report. POGO is a nonpartisan, independent watchdog that champions government reform. ![]()

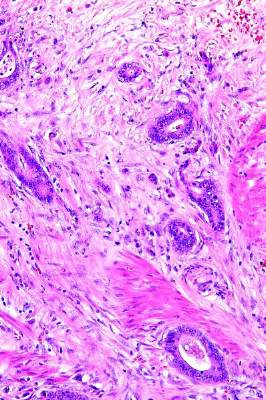

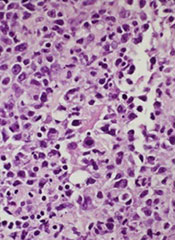

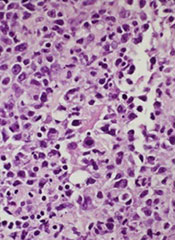

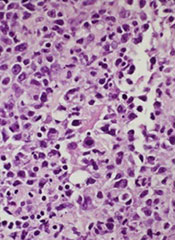

MMF may increase risk of CNS lymphoma

A new study has linked the immunosuppressive drug mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to an increased risk of central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma in solid organ transplant recipients.

However, the research also suggests that calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), when given alone or in combination with MMF, may protect transplant recipients from CNS lymphoma.

Researchers reported these findings in Oncotarget.

“MMF remains one of the best current medications for immunosuppression that we have,” said study author Amy Duffield, MD, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions in Baltimore, Maryland.

“But a better understanding of its association with CNS lymphoproliferative disease will be crucial to further improving patients’ transplant regimens based on all of the risks these patients face.”

Dr Duffield and her colleagues noted that lymphomas and leukemias are known to be complications of solid organ transplants, but these malignancies rarely start in the CNS.

Still, in recent years, clinicians have begun to notice a rise in primary CNS lymphoproliferative disorders among transplant recipients. The current study is thought to be the first large enough to identify a link between MMF and these tumors.

For this work, Dr Duffield and her colleagues analyzed information on 177 patients with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) who were seen at Johns Hopkins Hospital between 1986 and 2014.

In that group, 29 patients—mostly kidney transplant recipients—were diagnosed with primary CNS lymphoproliferative disorders. The researchers said these were predominantly classified as monomorphic PTLD (72%), and most of the classifiable lymphomas were large B-cell lymphomas.

There were no cases of primary CNS PTLD diagnosed between 1986 and 1997, but the diagnosis increased markedly in the next decades.

The proportion of primary CNS PTLD cases compared to other PTLDs was 4.4-fold higher in the period from 2005 to 2014 than in the period from 1995 to 2004 (P<0.0001), even though the total number of PTLD cases remained relatively stable over time.

The researchers had prescription records on 16 of the patients who developed primary CNS lymphoproliferative disease.

Fifteen of the 16 patients had been taking MMF in the year prior to, or at the time of, their PTLD diagnosis. On the other hand, 37 of the 102 patients with PTLD outside the CNS had taken MMF (P<0.001).

The researchers also found that patients who took CNIs, either alone or in combination with MMF, seemed to be protected from developing primary CNS disease.

Primary CNS lymphoproliferative disease accounted for 66.7% of PTLDs among patients who took MMF but not a CNI (n=6), 23.9% of PTLDs among patients who took both an MMF and a CNI (n=46), and 1.7% of PTLDs among patients who took just a CNI (n=60).

The researchers found similar trends in a set of 6966 patients with PTLD. Those patients’ records were gleaned from an organ transplant database managed by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the United Network for Organ Sharing.

“More research needs to be done to confirm our results,” said Genevieve Crane, MD, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

“But our work suggests that, at least in some patients, the combination of MMF and CNIs may be protective against CNS lymphoproliferative disease in a way that had not previously been appreciated.” ![]()

A new study has linked the immunosuppressive drug mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to an increased risk of central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma in solid organ transplant recipients.

However, the research also suggests that calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), when given alone or in combination with MMF, may protect transplant recipients from CNS lymphoma.

Researchers reported these findings in Oncotarget.

“MMF remains one of the best current medications for immunosuppression that we have,” said study author Amy Duffield, MD, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions in Baltimore, Maryland.

“But a better understanding of its association with CNS lymphoproliferative disease will be crucial to further improving patients’ transplant regimens based on all of the risks these patients face.”

Dr Duffield and her colleagues noted that lymphomas and leukemias are known to be complications of solid organ transplants, but these malignancies rarely start in the CNS.

Still, in recent years, clinicians have begun to notice a rise in primary CNS lymphoproliferative disorders among transplant recipients. The current study is thought to be the first large enough to identify a link between MMF and these tumors.

For this work, Dr Duffield and her colleagues analyzed information on 177 patients with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) who were seen at Johns Hopkins Hospital between 1986 and 2014.

In that group, 29 patients—mostly kidney transplant recipients—were diagnosed with primary CNS lymphoproliferative disorders. The researchers said these were predominantly classified as monomorphic PTLD (72%), and most of the classifiable lymphomas were large B-cell lymphomas.

There were no cases of primary CNS PTLD diagnosed between 1986 and 1997, but the diagnosis increased markedly in the next decades.

The proportion of primary CNS PTLD cases compared to other PTLDs was 4.4-fold higher in the period from 2005 to 2014 than in the period from 1995 to 2004 (P<0.0001), even though the total number of PTLD cases remained relatively stable over time.

The researchers had prescription records on 16 of the patients who developed primary CNS lymphoproliferative disease.

Fifteen of the 16 patients had been taking MMF in the year prior to, or at the time of, their PTLD diagnosis. On the other hand, 37 of the 102 patients with PTLD outside the CNS had taken MMF (P<0.001).

The researchers also found that patients who took CNIs, either alone or in combination with MMF, seemed to be protected from developing primary CNS disease.

Primary CNS lymphoproliferative disease accounted for 66.7% of PTLDs among patients who took MMF but not a CNI (n=6), 23.9% of PTLDs among patients who took both an MMF and a CNI (n=46), and 1.7% of PTLDs among patients who took just a CNI (n=60).

The researchers found similar trends in a set of 6966 patients with PTLD. Those patients’ records were gleaned from an organ transplant database managed by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the United Network for Organ Sharing.

“More research needs to be done to confirm our results,” said Genevieve Crane, MD, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

“But our work suggests that, at least in some patients, the combination of MMF and CNIs may be protective against CNS lymphoproliferative disease in a way that had not previously been appreciated.” ![]()

A new study has linked the immunosuppressive drug mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to an increased risk of central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma in solid organ transplant recipients.

However, the research also suggests that calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), when given alone or in combination with MMF, may protect transplant recipients from CNS lymphoma.

Researchers reported these findings in Oncotarget.

“MMF remains one of the best current medications for immunosuppression that we have,” said study author Amy Duffield, MD, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions in Baltimore, Maryland.

“But a better understanding of its association with CNS lymphoproliferative disease will be crucial to further improving patients’ transplant regimens based on all of the risks these patients face.”

Dr Duffield and her colleagues noted that lymphomas and leukemias are known to be complications of solid organ transplants, but these malignancies rarely start in the CNS.

Still, in recent years, clinicians have begun to notice a rise in primary CNS lymphoproliferative disorders among transplant recipients. The current study is thought to be the first large enough to identify a link between MMF and these tumors.

For this work, Dr Duffield and her colleagues analyzed information on 177 patients with post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) who were seen at Johns Hopkins Hospital between 1986 and 2014.

In that group, 29 patients—mostly kidney transplant recipients—were diagnosed with primary CNS lymphoproliferative disorders. The researchers said these were predominantly classified as monomorphic PTLD (72%), and most of the classifiable lymphomas were large B-cell lymphomas.

There were no cases of primary CNS PTLD diagnosed between 1986 and 1997, but the diagnosis increased markedly in the next decades.

The proportion of primary CNS PTLD cases compared to other PTLDs was 4.4-fold higher in the period from 2005 to 2014 than in the period from 1995 to 2004 (P<0.0001), even though the total number of PTLD cases remained relatively stable over time.

The researchers had prescription records on 16 of the patients who developed primary CNS lymphoproliferative disease.

Fifteen of the 16 patients had been taking MMF in the year prior to, or at the time of, their PTLD diagnosis. On the other hand, 37 of the 102 patients with PTLD outside the CNS had taken MMF (P<0.001).

The researchers also found that patients who took CNIs, either alone or in combination with MMF, seemed to be protected from developing primary CNS disease.

Primary CNS lymphoproliferative disease accounted for 66.7% of PTLDs among patients who took MMF but not a CNI (n=6), 23.9% of PTLDs among patients who took both an MMF and a CNI (n=46), and 1.7% of PTLDs among patients who took just a CNI (n=60).

The researchers found similar trends in a set of 6966 patients with PTLD. Those patients’ records were gleaned from an organ transplant database managed by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the United Network for Organ Sharing.

“More research needs to be done to confirm our results,” said Genevieve Crane, MD, PhD, of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

“But our work suggests that, at least in some patients, the combination of MMF and CNIs may be protective against CNS lymphoproliferative disease in a way that had not previously been appreciated.” ![]()

Code Status Discussions

Informed consent is one of the ethical, legal, and moral foundations of modern medicine.[1] Key elements of informed consent include: details of the procedure, benefits of the procedure, significant risks involved, likelihood of the outcome if predictable, and alternative therapeutic options.[2] Although rarely identified as such, conversations eliciting patient preferences about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) are among the most common examples of obtaining informed consent. Nevertheless, discussing CPR preference, often called code status discussions, differs from other examples of obtaining informed consent in 2 important ways. First, they occur well in advance of the potential need for CPR, so that the patient is well enough to participate meaningfully in the discussion. Second, because the default assumption is for patients to undergo the intervention (i.e. CPR), the focus of code status discussions is often on informed refusal, namely a decision about a do not resuscitate(DNR) order.

Since the institution of the Patient Self‐Determination Act in 1990, hospitals are obliged to educate patients about choices regarding end‐of‐life care at the time of hospital admission.[3] In many teaching hospitals, this responsibility falls to the admitting physician, often a trainee, who determines the patient's preferences regarding CPR and documents whether the patient is full code or DNR.

Prior studies have raised concerns about the quality of these conversations, highlighting their superficial nature and revealing trainee dissatisfaction with the results.[4, 5] Importantly, studies have shown that patients are capable of assimilating information about CPR when presented accurately and completely, and that such information can dramatically alter their choices.[6, 7, 8] These findings suggest that patients who are adequately educated will make more informed decisions regarding CPR, and that well‐informed choices about CPR may differ from poorly informed ones.

Although several studies have questioned the quality of code status discussions, none of these studies frames these interactions as examples of informed consent. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to examine the content of code status discussions as reported by internal medicine residents to determine whether they meet the basic tenets of informed consent, thereby facilitating informed decision making.

METHODS

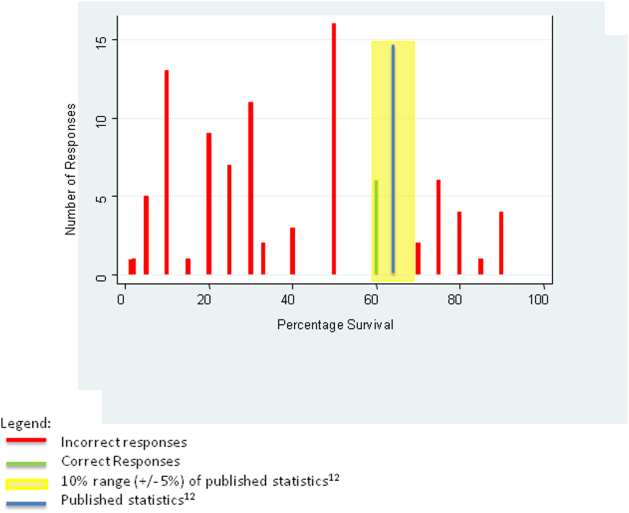

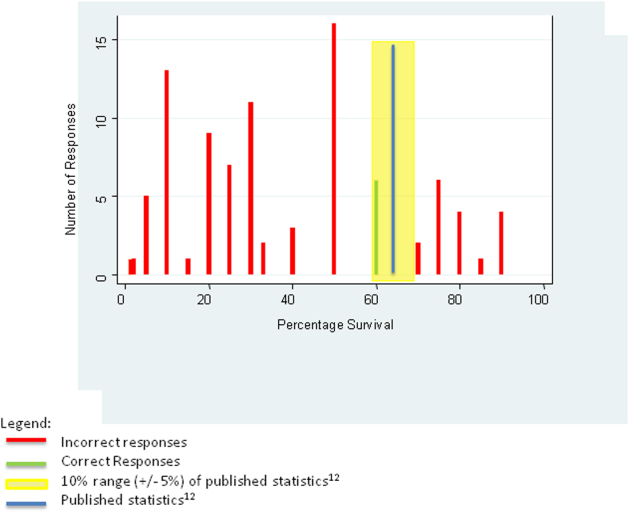

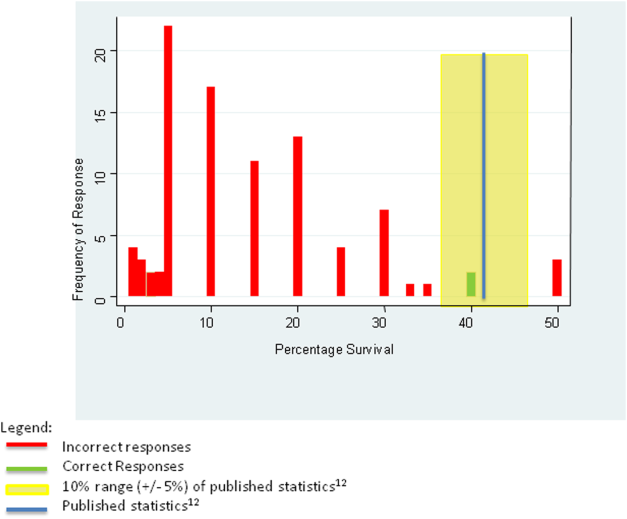

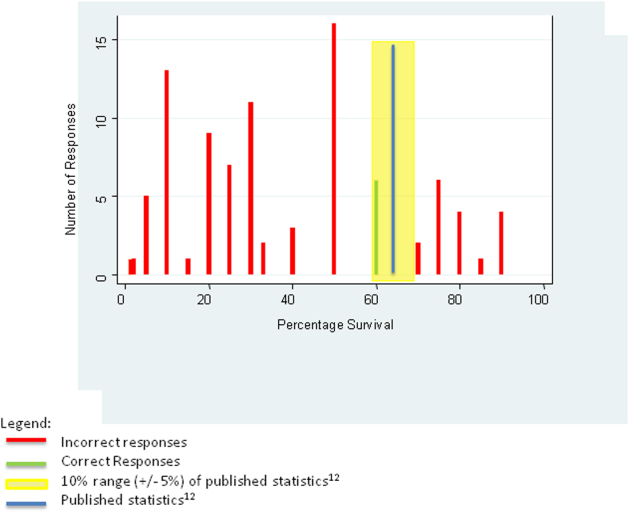

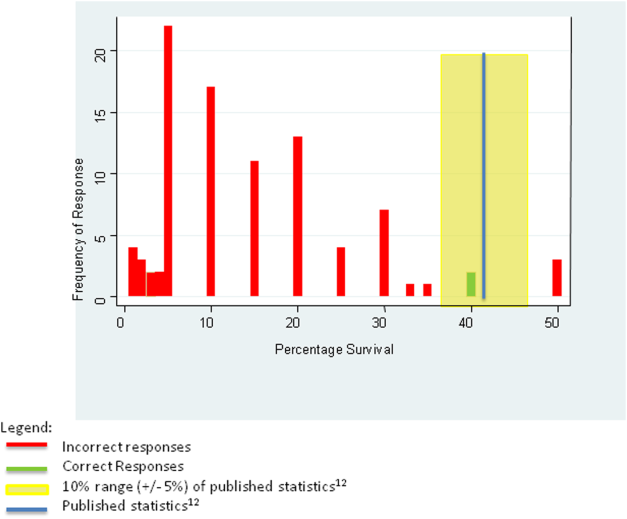

In an iterative, collaborative process, authors A.F.B. and M.K.B. (an internal medicine resident at the time of the study and a board‐certified palliative care specialist/oncologist with experience in survey development, respectively) developed a survey adapted from previously published surveys.[9, 10, 11] The survey solicited respondent demographics, frequency of code status conversations, content of these discussions, and barriers to discussions. The survey instrument can be viewed in the Supporting Information, Appendix A, in the online version of this article. We used a 5‐point frequency scale (almost nevernearly always) for questions regarding: specific aspects of the informed consent related to code status discussions, resident confidence in conducting code status discussions, and barriers to code status discussions. We used a checklist for questions regarding content of code status discussions and patient characteristics influencing code status discussions. Residents provided a numeric percentage answer to 2 knowledge‐based questions of postarrest outcomes: (1) likelihood a patient would survive a witnessed pulseless ventricular tachycardia event and (2) likelihood of survival of a pulseless electrical activity event. The survey was revised by a hospitalist with experience in survey design (G.C.H.). We piloted the survey with 15 residents not part of the subject population and made revisions based on their input.

We sent a link to the online survey over secure email to all 159 internal medicine residents at our urban‐based academic medical center in January 2012. The email described the purpose of the study and stated that participation in the study (or lack thereof) was voluntary, anonymous, and would not have ramifications within the residency program. As part of the recruitment email, we explicitly included the elements of informed consent for the study participants. Not all the questions were mandatory to complete the survey. We sent a reminder e‐mail on a weekly basis for a total of 3 times and closed the survey after 1 month. Our goal was a 60% (N = 95) response rate.

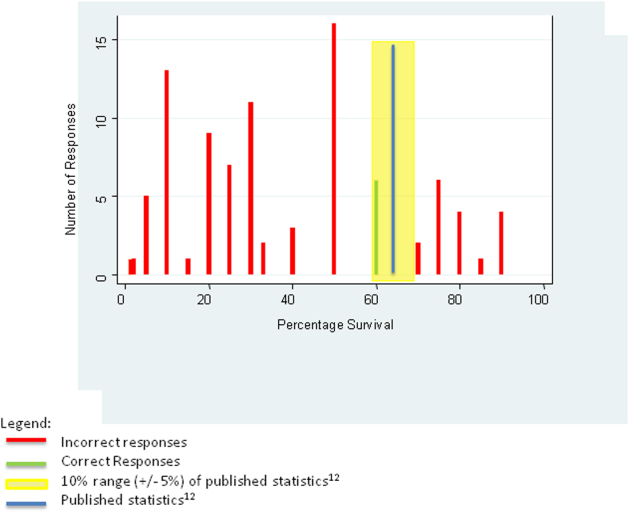

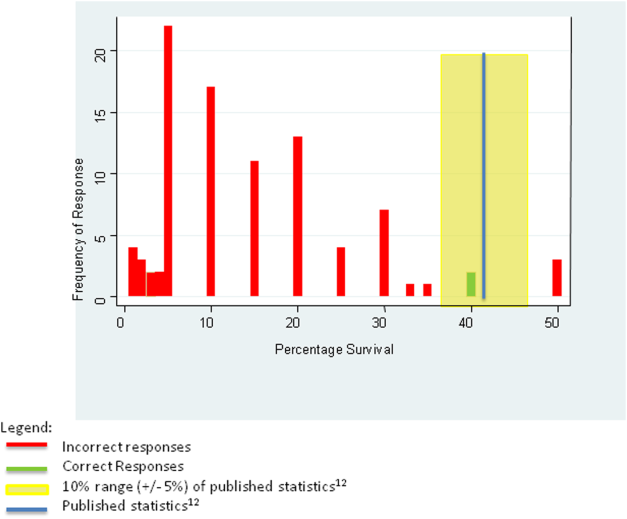

We tabulated the results by question. For analytic purposes, we aligned the content questions with key elements of informed consent as follows: step‐by‐step description of the events (details), patient‐specific likelihood of discharge if resuscitated (benefits), complications of resuscitation (risks), population‐based likelihood of discharge if resuscitated (likelihood), and opportunity for changing code status (alternatives). For the knowledge‐based questions, we deemed the answer correct if it was within 10% (5%) of published statistics from the 2010 national registry of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.[12] We stratified the key elements of informed consent and level of confidence by postgraduate year (PGY), comparing PGY1 residents versus PGY2 and PGY3 residents using 2 tests (or Fisher exact test for observations 5). We performed a univariate logistic regression analysis examining the relationship between confidence and reported use of informed consent elements in code discussions. The dependent variable of confidence in sufficient information having been provided for fully informed decision making was dichotomized as most of the time or nearly always versus other responses, whereas the independent variable was dichotomized as residents who reported using all 5 informed consent elements versus those who did not. We analyzed data using Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

The institutional review board of the Beth Israel Deaconess reviewed the study protocol and determined that it was exempt from institutional review board review.

RESULTS

One hundred of 159 (62.3%) internal medicine residents responded to the survey. Of the respondents 93% (N = 93) completed the survey. The 7% (N = 7) who did not complete the survey omitted the knowledge‐based questions and demographics. Approximately half of participants (54%, N = 50) were male. The majority of residents (85%, N = 79) had either occasional or frequent exposure to palliative care, with 10% (N = 9) having completed a palliative care rotation (Table 1).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| |

| Sex, male | 50 (54) |

| PGY level | |

| PGY1 | 35 (38) |

| PGY2 | 33 (35) |

| PGY3 | 25 (27) |

| Exposure to palliative care | |

| Very little | 5 (5) |

| Occasional | 55 (59) |

| Frequent | 24 (26) |

| Completed palliative care elective | 9 (10) |

| What type of teaching did you have with code status discussions (check all that apply)? | |

| No teaching | 6 (6) |

| Lectures | 35 (38) |

| Small group teaching sessions | 57 (61) |

| Direct observation and feedback | 50 (54) |

| Exposure to palliative care consultation while rotating on the wards | 54 (58) |

| Other | 4 (4) |

| How much has your previous teaching about resuscitative measures influenced your behavior? | |

| Not at all | 1 (1) |

| Not very much | 15 (16) |

| A little bit | 39 (42) |

| A lot | 38 (41) |