User login

Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System Causes a Lichenoid Drug Eruption

To the Editor:

Numerous drugs have been implicated as possible causes of lichenoid drug eruptions (LDEs). We describe a case of an LDE secondary to placement of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (IUS).

A 28-year-old woman presented with an extensive pruritic rash of 2 months’ duration. She reported that it began on the wrists; progressed inward to involve the trunk; and then became generalized over the trunk, back, wrists, and legs. A levonorgestrel-releasing IUS had been placed 6 weeks prior to the onset of the rash. She was otherwise healthy and took loratadine and pseudoephedrine on occasion for environmental allergies. On examination there were violaceous, lichenified, flat-topped, polygonal papules scattered over the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). Some papules demonstrated a Köbner phenomenon. No Wickham striae or mucosal involvement was noted. Rapid plasma reagin and hepatitis panel were negative. The patient was treated empirically with fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily.

|

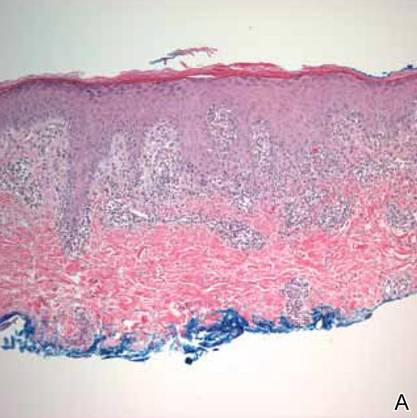

A shave biopsy was taken at the initial visit prior to steroid treatment. Histology revealed a classic lichenoid reaction pattern (Figure 2) and irregular acanthosis lying above the dense bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes with liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer, rare Civatte bodies in the epidermis, and melanophages in the dermis.

At 5-week follow-up, the patient showed some improvement but not complete control of the lesions with topical steroids. Because the patient was on no other regular medications, we recommended a 3-month trial removal of the IUS. The patient decided to have the IUS removed and noted complete clearance of the skin lesions within 1 month. Challenge with oral or intradermal levonorgestrel was not conducted after clearance of the rash, which is a weakness in this report. Accordingly, the possibility that this patient’s condition was caused by idiopathic lichen planus, which may resolve spontaneously, cannot be ruled out. However, because the patient noted substantial improvement following removal of the device and remained symptom free 2 years after removal, we concluded that the cutaneous lesions were secondary to an LDE in response to the IUS.

It should be noted that as-needed use of pseudoephedrine and loratadine continued during this 2-year follow-up period and again the patient experienced no return of symptoms, which is particularly important because both of these agents have been associated with drug eruption patterns akin to lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis patterns. Pseudoephedrine is particularly notorious for causing nonpigmenting fixed drug eruptions such as those that heal without hyperpigmentation, while antihistamines such as loratadine have been associated with lichenoid and subacute lupus erythematosus–pattern drug reactions.1,2

Lichenoid drug reactions fall into the category of lymphocyte-rich lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis skin disorders.3 There are currently 202 different drugs reported to cause lichen planus or lichenoid eruptions as collected in Litt’s Drug Eruption & Reaction Database.4 Some of the more common causes of an LDE include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, antimalarials, calcium channel blockers, gold salts, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.3,4 Lichenoid eruptions typically are attributed to oral hormonal contraceptives only.5,6 An eruption in response to intrauterine levonorgestrel treatment is rare. One case report of a lichenoid eruption in response to a copper IUS was hypothesized to be due to presence of nickel salts as a manufacturing contaminant; however, the manufacturer denied the presence of the contaminant.7

The manufacturer’s information for health care professionals prescribing levonorgestrel-releasing IUS describes rashes as an adverse reaction present in less than 5% of individuals.8 Levonorgestrel-releasing IUS consists of a polyethylene frame compounded with barium sulfate, 52 mg of levonorgestrel, silicone (polydimethylsiloxane), and a monofilament brown polyethylene removal thread. The device initially releases 20 μg levonorgestrel daily, with a stable levonorgestrel plasma level of 150 to 200 pg/mL reached after the first few weeks following insertion of the device.8 Levonorgestrel is an agonist at the progesterone and androgen receptors.9 In clinical trials, levonorgestrel was implicated as the cause of increased acne, hair loss, and hirsutism as cutaneous side effects from use of levonorgestrel implants.10 However, to our knowledge, none of the other components of the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS have previously been reported to cause lichen planus or LDE.

The levonorgestrel-releasing IUS has been implicated as the cause of biopsy-proven Sweet disease,11 exacerbation of preexisting seborrheic dermatitis,12 rosacea,13 and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.14 The skin findings in these cases resolved after removal of the IUS and appropriate treatment.

Identification of the causative drug can be difficult in LDE, as timing of the eruption can vary. The latent period has been reported to range from a few months to 1 to 2 years.15 Additionally, the clinical picture is often complicated in patients with a history of different drug dosages or multiple medications. When present, the histologic features of parakeratosis and eosinophils can be clues that a lichen planus–like eruption is drug related rather than idiopathic. However, the absence of these features does not rule out a medication or environmental trigger. In this case, the time-event relationship likely indicates that the eruption was related to the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS and not triggered by other medications or not idiopathic in nature. Lichenoid drug eruptions can resolve within a few weeks or up to 2 years after drug cessation and can occasionally be complicated by partial or complete resolution and recurrence even when the drug has not been discontinued.16,17 Lichenoid drug eruptions or idiopathic lichen planus generally are treated with topical immunomodulators or corticosteroids.3

Based on the time-event relationship, morphology, distribution, and histopathologic findings, we conclude that our patient developed LDE in response to the placement of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUS. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of LDE occurring as a rare adverse effect of these devices.

1. Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

2. Crowson AN, Magro CM. Lichenoid and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus-like dermatitis associated with antihistamine therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:95-99.

3. Sontheimer RD. Lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis: clinical and histological perspectives [published online ahead of print February 26, 2009]. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1088-1099.

4. Litt’s Drug Eruption & Reaction Database. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2015. http://www.drugeruptiondata.com/searchresults/index/reaction_type/id/1/char/L. Accessed June 11, 2015.

5. Coskey RJ. Eruptions due to oral contraceptives. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:333-334.

6. Thomas P, Dalle E, Revillon B, et al. Cutaneous effects in hormonal contraception [in French]. NPN Med. 1985;5:19-24.

7. Lombardi P, Campolmi P, Sertoli A. Lichenoid dermatitis caused by nickel salts? Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:520-521.

8. Mirena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2014.

9. Lemus AE, Vilchis F, Damsky R, et al. Mechanism of action of levonorgestrel: in vitro metabolism and specific interactions with steroid receptors in target organs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;41:881-890.

10. Brache V, Faundes A, Alvarex F, et al. Nonmenstrual adverse events during use of implantable contraceptives for women: data from clinical trials. Contraception. 2002;65:63-74.

11. Hamill M, Bowling J, Vega-Lopez F. Sweet’s syndrome and a Mirena intrauterine system. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2004;30:115-116.

12. Karri K, Mowbray D, Adams S, et al. Severe seborrhoeic dermatitis: side-effect of the Mirena intra-uterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2006;11:53-54.

13. Choudry K, Humphreys F, Menage J. Rosacea in association with the progesterone-releasing intrauterine contraceptive device. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:102.

14. Pereira A, Coker A. Hypersensitivity to Mirena—a rare complication. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:81.

15. Halevy S, Shai A. Lichenoid drug eruptions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):249-255.

16. Seehafer JR, Rogers RS 3rd, Fleming CR, et al. Lichen planus-like lesions caused by penicillamine in primary biliary cirrhosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:140-142.

17. Anderson TE. Lichen planus following quinidine therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1967;79:500.

To the Editor:

Numerous drugs have been implicated as possible causes of lichenoid drug eruptions (LDEs). We describe a case of an LDE secondary to placement of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (IUS).

A 28-year-old woman presented with an extensive pruritic rash of 2 months’ duration. She reported that it began on the wrists; progressed inward to involve the trunk; and then became generalized over the trunk, back, wrists, and legs. A levonorgestrel-releasing IUS had been placed 6 weeks prior to the onset of the rash. She was otherwise healthy and took loratadine and pseudoephedrine on occasion for environmental allergies. On examination there were violaceous, lichenified, flat-topped, polygonal papules scattered over the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). Some papules demonstrated a Köbner phenomenon. No Wickham striae or mucosal involvement was noted. Rapid plasma reagin and hepatitis panel were negative. The patient was treated empirically with fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily.

|

A shave biopsy was taken at the initial visit prior to steroid treatment. Histology revealed a classic lichenoid reaction pattern (Figure 2) and irregular acanthosis lying above the dense bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes with liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer, rare Civatte bodies in the epidermis, and melanophages in the dermis.

At 5-week follow-up, the patient showed some improvement but not complete control of the lesions with topical steroids. Because the patient was on no other regular medications, we recommended a 3-month trial removal of the IUS. The patient decided to have the IUS removed and noted complete clearance of the skin lesions within 1 month. Challenge with oral or intradermal levonorgestrel was not conducted after clearance of the rash, which is a weakness in this report. Accordingly, the possibility that this patient’s condition was caused by idiopathic lichen planus, which may resolve spontaneously, cannot be ruled out. However, because the patient noted substantial improvement following removal of the device and remained symptom free 2 years after removal, we concluded that the cutaneous lesions were secondary to an LDE in response to the IUS.

It should be noted that as-needed use of pseudoephedrine and loratadine continued during this 2-year follow-up period and again the patient experienced no return of symptoms, which is particularly important because both of these agents have been associated with drug eruption patterns akin to lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis patterns. Pseudoephedrine is particularly notorious for causing nonpigmenting fixed drug eruptions such as those that heal without hyperpigmentation, while antihistamines such as loratadine have been associated with lichenoid and subacute lupus erythematosus–pattern drug reactions.1,2

Lichenoid drug reactions fall into the category of lymphocyte-rich lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis skin disorders.3 There are currently 202 different drugs reported to cause lichen planus or lichenoid eruptions as collected in Litt’s Drug Eruption & Reaction Database.4 Some of the more common causes of an LDE include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, antimalarials, calcium channel blockers, gold salts, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.3,4 Lichenoid eruptions typically are attributed to oral hormonal contraceptives only.5,6 An eruption in response to intrauterine levonorgestrel treatment is rare. One case report of a lichenoid eruption in response to a copper IUS was hypothesized to be due to presence of nickel salts as a manufacturing contaminant; however, the manufacturer denied the presence of the contaminant.7

The manufacturer’s information for health care professionals prescribing levonorgestrel-releasing IUS describes rashes as an adverse reaction present in less than 5% of individuals.8 Levonorgestrel-releasing IUS consists of a polyethylene frame compounded with barium sulfate, 52 mg of levonorgestrel, silicone (polydimethylsiloxane), and a monofilament brown polyethylene removal thread. The device initially releases 20 μg levonorgestrel daily, with a stable levonorgestrel plasma level of 150 to 200 pg/mL reached after the first few weeks following insertion of the device.8 Levonorgestrel is an agonist at the progesterone and androgen receptors.9 In clinical trials, levonorgestrel was implicated as the cause of increased acne, hair loss, and hirsutism as cutaneous side effects from use of levonorgestrel implants.10 However, to our knowledge, none of the other components of the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS have previously been reported to cause lichen planus or LDE.

The levonorgestrel-releasing IUS has been implicated as the cause of biopsy-proven Sweet disease,11 exacerbation of preexisting seborrheic dermatitis,12 rosacea,13 and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.14 The skin findings in these cases resolved after removal of the IUS and appropriate treatment.

Identification of the causative drug can be difficult in LDE, as timing of the eruption can vary. The latent period has been reported to range from a few months to 1 to 2 years.15 Additionally, the clinical picture is often complicated in patients with a history of different drug dosages or multiple medications. When present, the histologic features of parakeratosis and eosinophils can be clues that a lichen planus–like eruption is drug related rather than idiopathic. However, the absence of these features does not rule out a medication or environmental trigger. In this case, the time-event relationship likely indicates that the eruption was related to the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS and not triggered by other medications or not idiopathic in nature. Lichenoid drug eruptions can resolve within a few weeks or up to 2 years after drug cessation and can occasionally be complicated by partial or complete resolution and recurrence even when the drug has not been discontinued.16,17 Lichenoid drug eruptions or idiopathic lichen planus generally are treated with topical immunomodulators or corticosteroids.3

Based on the time-event relationship, morphology, distribution, and histopathologic findings, we conclude that our patient developed LDE in response to the placement of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUS. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of LDE occurring as a rare adverse effect of these devices.

To the Editor:

Numerous drugs have been implicated as possible causes of lichenoid drug eruptions (LDEs). We describe a case of an LDE secondary to placement of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (IUS).

A 28-year-old woman presented with an extensive pruritic rash of 2 months’ duration. She reported that it began on the wrists; progressed inward to involve the trunk; and then became generalized over the trunk, back, wrists, and legs. A levonorgestrel-releasing IUS had been placed 6 weeks prior to the onset of the rash. She was otherwise healthy and took loratadine and pseudoephedrine on occasion for environmental allergies. On examination there were violaceous, lichenified, flat-topped, polygonal papules scattered over the arms, legs, and trunk (Figure 1). Some papules demonstrated a Köbner phenomenon. No Wickham striae or mucosal involvement was noted. Rapid plasma reagin and hepatitis panel were negative. The patient was treated empirically with fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily.

|

A shave biopsy was taken at the initial visit prior to steroid treatment. Histology revealed a classic lichenoid reaction pattern (Figure 2) and irregular acanthosis lying above the dense bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes with liquefaction degeneration of the basal layer, rare Civatte bodies in the epidermis, and melanophages in the dermis.

At 5-week follow-up, the patient showed some improvement but not complete control of the lesions with topical steroids. Because the patient was on no other regular medications, we recommended a 3-month trial removal of the IUS. The patient decided to have the IUS removed and noted complete clearance of the skin lesions within 1 month. Challenge with oral or intradermal levonorgestrel was not conducted after clearance of the rash, which is a weakness in this report. Accordingly, the possibility that this patient’s condition was caused by idiopathic lichen planus, which may resolve spontaneously, cannot be ruled out. However, because the patient noted substantial improvement following removal of the device and remained symptom free 2 years after removal, we concluded that the cutaneous lesions were secondary to an LDE in response to the IUS.

It should be noted that as-needed use of pseudoephedrine and loratadine continued during this 2-year follow-up period and again the patient experienced no return of symptoms, which is particularly important because both of these agents have been associated with drug eruption patterns akin to lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis patterns. Pseudoephedrine is particularly notorious for causing nonpigmenting fixed drug eruptions such as those that heal without hyperpigmentation, while antihistamines such as loratadine have been associated with lichenoid and subacute lupus erythematosus–pattern drug reactions.1,2

Lichenoid drug reactions fall into the category of lymphocyte-rich lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis skin disorders.3 There are currently 202 different drugs reported to cause lichen planus or lichenoid eruptions as collected in Litt’s Drug Eruption & Reaction Database.4 Some of the more common causes of an LDE include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, antimalarials, calcium channel blockers, gold salts, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.3,4 Lichenoid eruptions typically are attributed to oral hormonal contraceptives only.5,6 An eruption in response to intrauterine levonorgestrel treatment is rare. One case report of a lichenoid eruption in response to a copper IUS was hypothesized to be due to presence of nickel salts as a manufacturing contaminant; however, the manufacturer denied the presence of the contaminant.7

The manufacturer’s information for health care professionals prescribing levonorgestrel-releasing IUS describes rashes as an adverse reaction present in less than 5% of individuals.8 Levonorgestrel-releasing IUS consists of a polyethylene frame compounded with barium sulfate, 52 mg of levonorgestrel, silicone (polydimethylsiloxane), and a monofilament brown polyethylene removal thread. The device initially releases 20 μg levonorgestrel daily, with a stable levonorgestrel plasma level of 150 to 200 pg/mL reached after the first few weeks following insertion of the device.8 Levonorgestrel is an agonist at the progesterone and androgen receptors.9 In clinical trials, levonorgestrel was implicated as the cause of increased acne, hair loss, and hirsutism as cutaneous side effects from use of levonorgestrel implants.10 However, to our knowledge, none of the other components of the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS have previously been reported to cause lichen planus or LDE.

The levonorgestrel-releasing IUS has been implicated as the cause of biopsy-proven Sweet disease,11 exacerbation of preexisting seborrheic dermatitis,12 rosacea,13 and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.14 The skin findings in these cases resolved after removal of the IUS and appropriate treatment.

Identification of the causative drug can be difficult in LDE, as timing of the eruption can vary. The latent period has been reported to range from a few months to 1 to 2 years.15 Additionally, the clinical picture is often complicated in patients with a history of different drug dosages or multiple medications. When present, the histologic features of parakeratosis and eosinophils can be clues that a lichen planus–like eruption is drug related rather than idiopathic. However, the absence of these features does not rule out a medication or environmental trigger. In this case, the time-event relationship likely indicates that the eruption was related to the levonorgestrel-releasing IUS and not triggered by other medications or not idiopathic in nature. Lichenoid drug eruptions can resolve within a few weeks or up to 2 years after drug cessation and can occasionally be complicated by partial or complete resolution and recurrence even when the drug has not been discontinued.16,17 Lichenoid drug eruptions or idiopathic lichen planus generally are treated with topical immunomodulators or corticosteroids.3

Based on the time-event relationship, morphology, distribution, and histopathologic findings, we conclude that our patient developed LDE in response to the placement of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUS. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of LDE occurring as a rare adverse effect of these devices.

1. Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

2. Crowson AN, Magro CM. Lichenoid and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus-like dermatitis associated with antihistamine therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:95-99.

3. Sontheimer RD. Lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis: clinical and histological perspectives [published online ahead of print February 26, 2009]. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1088-1099.

4. Litt’s Drug Eruption & Reaction Database. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2015. http://www.drugeruptiondata.com/searchresults/index/reaction_type/id/1/char/L. Accessed June 11, 2015.

5. Coskey RJ. Eruptions due to oral contraceptives. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:333-334.

6. Thomas P, Dalle E, Revillon B, et al. Cutaneous effects in hormonal contraception [in French]. NPN Med. 1985;5:19-24.

7. Lombardi P, Campolmi P, Sertoli A. Lichenoid dermatitis caused by nickel salts? Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:520-521.

8. Mirena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2014.

9. Lemus AE, Vilchis F, Damsky R, et al. Mechanism of action of levonorgestrel: in vitro metabolism and specific interactions with steroid receptors in target organs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;41:881-890.

10. Brache V, Faundes A, Alvarex F, et al. Nonmenstrual adverse events during use of implantable contraceptives for women: data from clinical trials. Contraception. 2002;65:63-74.

11. Hamill M, Bowling J, Vega-Lopez F. Sweet’s syndrome and a Mirena intrauterine system. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2004;30:115-116.

12. Karri K, Mowbray D, Adams S, et al. Severe seborrhoeic dermatitis: side-effect of the Mirena intra-uterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2006;11:53-54.

13. Choudry K, Humphreys F, Menage J. Rosacea in association with the progesterone-releasing intrauterine contraceptive device. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:102.

14. Pereira A, Coker A. Hypersensitivity to Mirena—a rare complication. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:81.

15. Halevy S, Shai A. Lichenoid drug eruptions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):249-255.

16. Seehafer JR, Rogers RS 3rd, Fleming CR, et al. Lichen planus-like lesions caused by penicillamine in primary biliary cirrhosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:140-142.

17. Anderson TE. Lichen planus following quinidine therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1967;79:500.

1. Shelley WB, Shelley ED. Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption as a distinctive reaction pattern: examples caused by sensitivity to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and tetrahydrozoline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:403-407.

2. Crowson AN, Magro CM. Lichenoid and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus-like dermatitis associated with antihistamine therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:95-99.

3. Sontheimer RD. Lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis: clinical and histological perspectives [published online ahead of print February 26, 2009]. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1088-1099.

4. Litt’s Drug Eruption & Reaction Database. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group; 2015. http://www.drugeruptiondata.com/searchresults/index/reaction_type/id/1/char/L. Accessed June 11, 2015.

5. Coskey RJ. Eruptions due to oral contraceptives. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:333-334.

6. Thomas P, Dalle E, Revillon B, et al. Cutaneous effects in hormonal contraception [in French]. NPN Med. 1985;5:19-24.

7. Lombardi P, Campolmi P, Sertoli A. Lichenoid dermatitis caused by nickel salts? Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:520-521.

8. Mirena [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2014.

9. Lemus AE, Vilchis F, Damsky R, et al. Mechanism of action of levonorgestrel: in vitro metabolism and specific interactions with steroid receptors in target organs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;41:881-890.

10. Brache V, Faundes A, Alvarex F, et al. Nonmenstrual adverse events during use of implantable contraceptives for women: data from clinical trials. Contraception. 2002;65:63-74.

11. Hamill M, Bowling J, Vega-Lopez F. Sweet’s syndrome and a Mirena intrauterine system. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2004;30:115-116.

12. Karri K, Mowbray D, Adams S, et al. Severe seborrhoeic dermatitis: side-effect of the Mirena intra-uterine system. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2006;11:53-54.

13. Choudry K, Humphreys F, Menage J. Rosacea in association with the progesterone-releasing intrauterine contraceptive device. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:102.

14. Pereira A, Coker A. Hypersensitivity to Mirena—a rare complication. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:81.

15. Halevy S, Shai A. Lichenoid drug eruptions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):249-255.

16. Seehafer JR, Rogers RS 3rd, Fleming CR, et al. Lichen planus-like lesions caused by penicillamine in primary biliary cirrhosis. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:140-142.

17. Anderson TE. Lichen planus following quinidine therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1967;79:500.

Guidelines, appropriateness, and quality of care in PAD

Symptomatic PAD is among the most common reasons for referral to a vascular specialist. The volume of invasive procedures for PAD, and the attendant cost, has risen dramatically over the last decade. The majority of these interventions are for treatment of intermittent claudication (IC). Patients with IC have a broad range of disabilities and comorbid conditions. Medical therapy, smoking cessation, and exercise are of proven value for symptom improvement and long-term vascular health. In appropriately selected patients, revascularization for IC can relieve pain and improve ambulatory function. As a vascular surgeon keenly interested in PAD, I perform both open and endovascular interventions for IC in my practice.

Recent reports have highlighted rising concerns about the overuse of invasive procedures in PAD. A New York Times article1 cited the dramatic growth of stent procedures, raising a red flag among multiple stakeholders and consumers of vascular care. Although a closer look at the NY Times data highlights the explosion of stenting for venous disease, much of the subsequent discussion focused on PAD treatment, with its decade-long trend of rising volumes.

Another recent report2 documented the growing volume and costs of office-based percutaneous interventions for PAD in the United States, coincident with changes in Medicare reimbursement that greatly incentivized providers. This has turned the spotlight on office-based angiography suites, and how they are monitored. Improved, less invasive technology is often cited as a rational basis for offering intervention more readily to PAD patients. Unfortunately, the data on efficacy of interventions in IC is shockingly limited, leaving a wide gap in evidence supplanted by poor quality studies, overemphasis on technical success, market forces, and naked economics.

Just prior to the publication of the New York Times article on stent use, the SVS released a clinical practice guideline on the management of asymptomatic PAD and claudication.3 Systematic evidence reviews were undertaken4,5 and an expert panel of clinicians developed a list of specific recommendations. Medical therapy and exercise, preferably supervised exercise, were strongly recommended as first-line therapy for IC. Revascularization was considered reasonable for those patients with significant disability, acceptable risk, and after pharmacologic or exercise therapy have failed. An important recommendation in the guideline addresses a minimal effectiveness standard for revascularization in IC. Physicians should carefully consider the likelihood of functional benefit of a procedure based on patient risk, degree of impairment, and anatomic/technical factors that are known to impact patency.

The guideline suggests that a recommended intervention for IC should have a minimum expectation of >50% likelihood of sustained benefit for at least 2 years. At a recent local vascular symposium attended by more than 100 vascular providers, I asked the following question: “If you were a PAD patient considering an invasive procedure for claudication, what is the minimum likelihood of durable walking improvement you would expect?” The choices were >50% likelihood for at least 1 year, 2 years, or 3 years. Nearly 80% voted that they would want a 3-year, 50% minimum “guarantee” to consent to treatment. That seems quite rational to me.

Surgical and endovascular interventions for even advanced forms of aorto-iliac disease would generally meet the “>50% patency for at least 2-3 years” bar. But infrainguinal intervention is quite a different story. Although technology continues to advance with drug elution and improved stent designs for femoro-popliteal occlusive disease (FPOD), it has been incremental. I think it is fair to say that 3-year durability of an endovascular intervention for extensive FPOD is much more the exception than the rule. Now let’s consider a bit of “claudication math”. FPOD is commonly bilateral and symmetric.

How does one approach bilateral significant FPOD in a claudicant? If an intervention of long segment FPOD has a 60% chance of patency for 2 years, what’s the likelihood of a successful patient outcome if both legs are treated? Since we can usually assume two good legs are required for walking, it would be 0.6 x 0.6= 0.36! The best treatment we have for FPOD is a vein bypass graft, with a 70%-80% 3-year outcome. Bilateral fem-pop vein bypass grafts would just make the 50%, 3-year minimum expectation threshold, at the expense of two open procedures with their potential complications and costs. All of this means what we have always known: that we need to choose very wisely when intervening for claudication to get successful and satisfying outcomes. The old dictum “stop smoking and start walking” should not be replaced by “lets do a Duplex and take a look at your blockage, then we’ll see.”

Practice guidelines are important because they represent consensus recommendations, but they often leave considerable room for interpretation, particularly where the evidence is less strong. “Appropriateness” criteria, rather than addressing care of a specific clinical condition, focus on indications for specific procedures. Because the notion of “inappropriate” carries liability implications, appropriateness criteria tend to be even more liberal. What we really need are criteria for “rational use” of interventions, and I believe the “50%/2-year” minimum threshold for claudication in the SVS guideline is a good place to start.

Payers, most importantly Medicare, are getting increasingly interested in measuring quality of care in PAD. I believe that there are too many interventions being done in mild to moderate PAD, without adequate patient education, medical therapy, and exercise trials. I believe that informed consent is inconsistent at best, and that patients largely lack the tools for true “shared decision making” in these interactions. I believe that provider implementation of guideline-recommended medical therapy and follow-up care after invasive procedures is highly variable.

So here is what I would do if I were the CEO of a large payer looking at this state of affairs: I would offer qualified coverage for exercise therapy for 3-6 months for IC, and stipulate that outside of vocation-limiting disability, revascularization would not be covered unless a bona fide trial of exercise was made. I would contract with vascular practices that met a high standard of pre- and post-procedural guideline adherence, including prescription of cardioprotective drugs and surveillance. And I would mandate that authorized vascular providers on my panel collect follow-up data for at least 1 year in a high percentage of their PAD interventions, using VQI or a similar tool. Of course real change will require a better alignment of incentives, and by that I don’t mean just penalties, but also rewards for meeting benchmarks. The SVS should continue to broadly promote the development of higher quality standards in PAD care, for the long-term benefit of our patients and our specialty.

References:

1. Medicare payment surge for stents to unblock blood vessels in limbs. New York Times. Jan. 29, 2015 (online).

2. J. Amer. Coll. Card. 2015; 65:920-7.

3. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015;61 (3 suppl):2S-41S.

4. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015;61 (3 suppl):42S-53S.

5. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015; 61 (3 suppl):54S-73S.

Dr. Conte is professor of surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, co-chair of the SVS Lower Extremity Practice Guidelines Committee, and one of three co-editors leading the GVG CLTI Guidelines Steering Committee. He reported that he is on the Cook Medical–Scientific Advisory Board and the Medtronic Inc. Scientific Advisory Board, and is a lecturer for Cook Medical.

Symptomatic PAD is among the most common reasons for referral to a vascular specialist. The volume of invasive procedures for PAD, and the attendant cost, has risen dramatically over the last decade. The majority of these interventions are for treatment of intermittent claudication (IC). Patients with IC have a broad range of disabilities and comorbid conditions. Medical therapy, smoking cessation, and exercise are of proven value for symptom improvement and long-term vascular health. In appropriately selected patients, revascularization for IC can relieve pain and improve ambulatory function. As a vascular surgeon keenly interested in PAD, I perform both open and endovascular interventions for IC in my practice.

Recent reports have highlighted rising concerns about the overuse of invasive procedures in PAD. A New York Times article1 cited the dramatic growth of stent procedures, raising a red flag among multiple stakeholders and consumers of vascular care. Although a closer look at the NY Times data highlights the explosion of stenting for venous disease, much of the subsequent discussion focused on PAD treatment, with its decade-long trend of rising volumes.

Another recent report2 documented the growing volume and costs of office-based percutaneous interventions for PAD in the United States, coincident with changes in Medicare reimbursement that greatly incentivized providers. This has turned the spotlight on office-based angiography suites, and how they are monitored. Improved, less invasive technology is often cited as a rational basis for offering intervention more readily to PAD patients. Unfortunately, the data on efficacy of interventions in IC is shockingly limited, leaving a wide gap in evidence supplanted by poor quality studies, overemphasis on technical success, market forces, and naked economics.

Just prior to the publication of the New York Times article on stent use, the SVS released a clinical practice guideline on the management of asymptomatic PAD and claudication.3 Systematic evidence reviews were undertaken4,5 and an expert panel of clinicians developed a list of specific recommendations. Medical therapy and exercise, preferably supervised exercise, were strongly recommended as first-line therapy for IC. Revascularization was considered reasonable for those patients with significant disability, acceptable risk, and after pharmacologic or exercise therapy have failed. An important recommendation in the guideline addresses a minimal effectiveness standard for revascularization in IC. Physicians should carefully consider the likelihood of functional benefit of a procedure based on patient risk, degree of impairment, and anatomic/technical factors that are known to impact patency.

The guideline suggests that a recommended intervention for IC should have a minimum expectation of >50% likelihood of sustained benefit for at least 2 years. At a recent local vascular symposium attended by more than 100 vascular providers, I asked the following question: “If you were a PAD patient considering an invasive procedure for claudication, what is the minimum likelihood of durable walking improvement you would expect?” The choices were >50% likelihood for at least 1 year, 2 years, or 3 years. Nearly 80% voted that they would want a 3-year, 50% minimum “guarantee” to consent to treatment. That seems quite rational to me.

Surgical and endovascular interventions for even advanced forms of aorto-iliac disease would generally meet the “>50% patency for at least 2-3 years” bar. But infrainguinal intervention is quite a different story. Although technology continues to advance with drug elution and improved stent designs for femoro-popliteal occlusive disease (FPOD), it has been incremental. I think it is fair to say that 3-year durability of an endovascular intervention for extensive FPOD is much more the exception than the rule. Now let’s consider a bit of “claudication math”. FPOD is commonly bilateral and symmetric.

How does one approach bilateral significant FPOD in a claudicant? If an intervention of long segment FPOD has a 60% chance of patency for 2 years, what’s the likelihood of a successful patient outcome if both legs are treated? Since we can usually assume two good legs are required for walking, it would be 0.6 x 0.6= 0.36! The best treatment we have for FPOD is a vein bypass graft, with a 70%-80% 3-year outcome. Bilateral fem-pop vein bypass grafts would just make the 50%, 3-year minimum expectation threshold, at the expense of two open procedures with their potential complications and costs. All of this means what we have always known: that we need to choose very wisely when intervening for claudication to get successful and satisfying outcomes. The old dictum “stop smoking and start walking” should not be replaced by “lets do a Duplex and take a look at your blockage, then we’ll see.”

Practice guidelines are important because they represent consensus recommendations, but they often leave considerable room for interpretation, particularly where the evidence is less strong. “Appropriateness” criteria, rather than addressing care of a specific clinical condition, focus on indications for specific procedures. Because the notion of “inappropriate” carries liability implications, appropriateness criteria tend to be even more liberal. What we really need are criteria for “rational use” of interventions, and I believe the “50%/2-year” minimum threshold for claudication in the SVS guideline is a good place to start.

Payers, most importantly Medicare, are getting increasingly interested in measuring quality of care in PAD. I believe that there are too many interventions being done in mild to moderate PAD, without adequate patient education, medical therapy, and exercise trials. I believe that informed consent is inconsistent at best, and that patients largely lack the tools for true “shared decision making” in these interactions. I believe that provider implementation of guideline-recommended medical therapy and follow-up care after invasive procedures is highly variable.

So here is what I would do if I were the CEO of a large payer looking at this state of affairs: I would offer qualified coverage for exercise therapy for 3-6 months for IC, and stipulate that outside of vocation-limiting disability, revascularization would not be covered unless a bona fide trial of exercise was made. I would contract with vascular practices that met a high standard of pre- and post-procedural guideline adherence, including prescription of cardioprotective drugs and surveillance. And I would mandate that authorized vascular providers on my panel collect follow-up data for at least 1 year in a high percentage of their PAD interventions, using VQI or a similar tool. Of course real change will require a better alignment of incentives, and by that I don’t mean just penalties, but also rewards for meeting benchmarks. The SVS should continue to broadly promote the development of higher quality standards in PAD care, for the long-term benefit of our patients and our specialty.

References:

1. Medicare payment surge for stents to unblock blood vessels in limbs. New York Times. Jan. 29, 2015 (online).

2. J. Amer. Coll. Card. 2015; 65:920-7.

3. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015;61 (3 suppl):2S-41S.

4. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015;61 (3 suppl):42S-53S.

5. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015; 61 (3 suppl):54S-73S.

Dr. Conte is professor of surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, co-chair of the SVS Lower Extremity Practice Guidelines Committee, and one of three co-editors leading the GVG CLTI Guidelines Steering Committee. He reported that he is on the Cook Medical–Scientific Advisory Board and the Medtronic Inc. Scientific Advisory Board, and is a lecturer for Cook Medical.

Symptomatic PAD is among the most common reasons for referral to a vascular specialist. The volume of invasive procedures for PAD, and the attendant cost, has risen dramatically over the last decade. The majority of these interventions are for treatment of intermittent claudication (IC). Patients with IC have a broad range of disabilities and comorbid conditions. Medical therapy, smoking cessation, and exercise are of proven value for symptom improvement and long-term vascular health. In appropriately selected patients, revascularization for IC can relieve pain and improve ambulatory function. As a vascular surgeon keenly interested in PAD, I perform both open and endovascular interventions for IC in my practice.

Recent reports have highlighted rising concerns about the overuse of invasive procedures in PAD. A New York Times article1 cited the dramatic growth of stent procedures, raising a red flag among multiple stakeholders and consumers of vascular care. Although a closer look at the NY Times data highlights the explosion of stenting for venous disease, much of the subsequent discussion focused on PAD treatment, with its decade-long trend of rising volumes.

Another recent report2 documented the growing volume and costs of office-based percutaneous interventions for PAD in the United States, coincident with changes in Medicare reimbursement that greatly incentivized providers. This has turned the spotlight on office-based angiography suites, and how they are monitored. Improved, less invasive technology is often cited as a rational basis for offering intervention more readily to PAD patients. Unfortunately, the data on efficacy of interventions in IC is shockingly limited, leaving a wide gap in evidence supplanted by poor quality studies, overemphasis on technical success, market forces, and naked economics.

Just prior to the publication of the New York Times article on stent use, the SVS released a clinical practice guideline on the management of asymptomatic PAD and claudication.3 Systematic evidence reviews were undertaken4,5 and an expert panel of clinicians developed a list of specific recommendations. Medical therapy and exercise, preferably supervised exercise, were strongly recommended as first-line therapy for IC. Revascularization was considered reasonable for those patients with significant disability, acceptable risk, and after pharmacologic or exercise therapy have failed. An important recommendation in the guideline addresses a minimal effectiveness standard for revascularization in IC. Physicians should carefully consider the likelihood of functional benefit of a procedure based on patient risk, degree of impairment, and anatomic/technical factors that are known to impact patency.

The guideline suggests that a recommended intervention for IC should have a minimum expectation of >50% likelihood of sustained benefit for at least 2 years. At a recent local vascular symposium attended by more than 100 vascular providers, I asked the following question: “If you were a PAD patient considering an invasive procedure for claudication, what is the minimum likelihood of durable walking improvement you would expect?” The choices were >50% likelihood for at least 1 year, 2 years, or 3 years. Nearly 80% voted that they would want a 3-year, 50% minimum “guarantee” to consent to treatment. That seems quite rational to me.

Surgical and endovascular interventions for even advanced forms of aorto-iliac disease would generally meet the “>50% patency for at least 2-3 years” bar. But infrainguinal intervention is quite a different story. Although technology continues to advance with drug elution and improved stent designs for femoro-popliteal occlusive disease (FPOD), it has been incremental. I think it is fair to say that 3-year durability of an endovascular intervention for extensive FPOD is much more the exception than the rule. Now let’s consider a bit of “claudication math”. FPOD is commonly bilateral and symmetric.

How does one approach bilateral significant FPOD in a claudicant? If an intervention of long segment FPOD has a 60% chance of patency for 2 years, what’s the likelihood of a successful patient outcome if both legs are treated? Since we can usually assume two good legs are required for walking, it would be 0.6 x 0.6= 0.36! The best treatment we have for FPOD is a vein bypass graft, with a 70%-80% 3-year outcome. Bilateral fem-pop vein bypass grafts would just make the 50%, 3-year minimum expectation threshold, at the expense of two open procedures with their potential complications and costs. All of this means what we have always known: that we need to choose very wisely when intervening for claudication to get successful and satisfying outcomes. The old dictum “stop smoking and start walking” should not be replaced by “lets do a Duplex and take a look at your blockage, then we’ll see.”

Practice guidelines are important because they represent consensus recommendations, but they often leave considerable room for interpretation, particularly where the evidence is less strong. “Appropriateness” criteria, rather than addressing care of a specific clinical condition, focus on indications for specific procedures. Because the notion of “inappropriate” carries liability implications, appropriateness criteria tend to be even more liberal. What we really need are criteria for “rational use” of interventions, and I believe the “50%/2-year” minimum threshold for claudication in the SVS guideline is a good place to start.

Payers, most importantly Medicare, are getting increasingly interested in measuring quality of care in PAD. I believe that there are too many interventions being done in mild to moderate PAD, without adequate patient education, medical therapy, and exercise trials. I believe that informed consent is inconsistent at best, and that patients largely lack the tools for true “shared decision making” in these interactions. I believe that provider implementation of guideline-recommended medical therapy and follow-up care after invasive procedures is highly variable.

So here is what I would do if I were the CEO of a large payer looking at this state of affairs: I would offer qualified coverage for exercise therapy for 3-6 months for IC, and stipulate that outside of vocation-limiting disability, revascularization would not be covered unless a bona fide trial of exercise was made. I would contract with vascular practices that met a high standard of pre- and post-procedural guideline adherence, including prescription of cardioprotective drugs and surveillance. And I would mandate that authorized vascular providers on my panel collect follow-up data for at least 1 year in a high percentage of their PAD interventions, using VQI or a similar tool. Of course real change will require a better alignment of incentives, and by that I don’t mean just penalties, but also rewards for meeting benchmarks. The SVS should continue to broadly promote the development of higher quality standards in PAD care, for the long-term benefit of our patients and our specialty.

References:

1. Medicare payment surge for stents to unblock blood vessels in limbs. New York Times. Jan. 29, 2015 (online).

2. J. Amer. Coll. Card. 2015; 65:920-7.

3. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015;61 (3 suppl):2S-41S.

4. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015;61 (3 suppl):42S-53S.

5. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015; 61 (3 suppl):54S-73S.

Dr. Conte is professor of surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, co-chair of the SVS Lower Extremity Practice Guidelines Committee, and one of three co-editors leading the GVG CLTI Guidelines Steering Committee. He reported that he is on the Cook Medical–Scientific Advisory Board and the Medtronic Inc. Scientific Advisory Board, and is a lecturer for Cook Medical.

Society of Hospital Medicine Events, Online Tools, Programs for Hospitalists

Career Advancers: SHM Events, Online Tools, and Programs

Hospitalists can advance their careers and the hospital medicine movement at the same time, with in-person events, online tools, and other programs designed specifically for people providing care to hospitalized patients.

When hospitalists meet face to face, good things happen. Solutions are shared. Challenges are addressed. But most importantly, SHM’s meetings are sources of energy and inspiration for the thousands of hospitalists who attend them every year.

July 23-26, San Antonio

There’s still time to register for the fast-growing national event organized specifically for pediatric hospitalists. This year, the meeting will focus on mentoring, networking, and partnerships to improve children’s health locally and globally.

Meeting attendees should plan on downloading the PHM 2015 app to get session materials, download presentations, and find their way at the conference.

![]()

October 19-22, Austin

Have you taken on more leadership responsibilities at your hospital?

Or are you ready to demonstrate that you’re ready to take them on?

SHM’s Leadership Academy has trained thousands of hospitalists to lead groups more effectively and to understand the financial realities of running a hospital

medicine practice. www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

![]()

March 6-9, 2016, San Diego

Every year, thousands of hospitalists gather for educational sessions, professional networking, and time to catch up with friends in the hospital medicine movement. Now is the time to schedule time off and register! www.hospitalmedicine2016.org

Meet-Ups for Medical Students and Residents

Chicago and Los Angeles

Are you in the Chicago or Los Angeles area? Do you know medical students and residents exploring their career options? Make sure they know about SHM’s

Future of Hospital Medicine events later this year. Each event features hospitalist leaders talking about their careers and—of course—there will be food. The first event was held in May at University of Chicago. Upcoming events will be at Rush University in Chicago on September 24 and David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA on October 22. Visit the website below for details, and share with your colleagues! www.futureofhospitalmedicine.org/events

If you can’t make it to in-person events, SHM brings some of the very best of the hospital medicine movement to your smartphone, tablet, and computer.

New at the Learning Portal: “Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment” and “Patient Safety Tools”

Free CME is available to all SHM members at www.shmlearningportal.org, and new modules are added all the time. Recently, SHM has added two new modules:

- Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment. Perioperative cardiac complications are the most widely feared medical issues for the anesthesiologist, surgeon, and medical consultant as they approach a patient with the option of surgery. To assess for pre-operative cardiac risk, hospitalists should follow a step-wise algorithm. This new module reviews the risk assessment process and enables the hospitalist to order appropriate pre-operative testing.

- Patient Safety Tools: Root Cause Analysis and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis 2015. This updated online learning module begins with a lesson and contains a 10-question post-test with accompanying answers, rationales, and references. When the participant selects an answer, immediate feedback is given explaining the correct answer.

Quality Improvement Webinars

![]()

SHM is hosting nine webinars between now and September. Hospitalists can attend the webinars in real time or download them from the SHM website at www.hospitalmedicine.org/qiwebinar.

Project BOOST webinar series:

- Project BOOST Teach-Back;

- Project BOOST Presents “Partnering with Skilled Nursing Facilities”; and

- Project BOOST Presents “Approaches to Readmission Risk Stratification.”

Glycemic control webinar series:

- Perioperative Management of Hyperglycemia;

- Hypoglycemia Management and Prevention; and

- Subcutaneous Insulin Order Sets in the Inpatient Setting: Design and Implementation.

General QI webinars:

- Quality Improvement for Hospital Medicine Groups: Self-Assessment and Self-Improvement Using the SHM Key Characteristics;

- Coaching a Quality Improvement Team: Basics for Being Sure Any QI Team and Project Are on the Right Track; and

- Elevating Provider Experience to Improve Patient Experience.

Evaluate Your Performance with the ACS Performance Improvement CME Program

![]()

The ACS PI-CME is a self-directed, web-based activity designed to help you evaluate your practice. Registration is FREE. Upon completion of the activity, participants will receive 20 CME Credits.

For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/acs and click “REGISTER.”

Career Advancers: SHM Events, Online Tools, and Programs

Hospitalists can advance their careers and the hospital medicine movement at the same time, with in-person events, online tools, and other programs designed specifically for people providing care to hospitalized patients.

When hospitalists meet face to face, good things happen. Solutions are shared. Challenges are addressed. But most importantly, SHM’s meetings are sources of energy and inspiration for the thousands of hospitalists who attend them every year.

July 23-26, San Antonio

There’s still time to register for the fast-growing national event organized specifically for pediatric hospitalists. This year, the meeting will focus on mentoring, networking, and partnerships to improve children’s health locally and globally.

Meeting attendees should plan on downloading the PHM 2015 app to get session materials, download presentations, and find their way at the conference.

![]()

October 19-22, Austin

Have you taken on more leadership responsibilities at your hospital?

Or are you ready to demonstrate that you’re ready to take them on?

SHM’s Leadership Academy has trained thousands of hospitalists to lead groups more effectively and to understand the financial realities of running a hospital

medicine practice. www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

![]()

March 6-9, 2016, San Diego

Every year, thousands of hospitalists gather for educational sessions, professional networking, and time to catch up with friends in the hospital medicine movement. Now is the time to schedule time off and register! www.hospitalmedicine2016.org

Meet-Ups for Medical Students and Residents

Chicago and Los Angeles

Are you in the Chicago or Los Angeles area? Do you know medical students and residents exploring their career options? Make sure they know about SHM’s

Future of Hospital Medicine events later this year. Each event features hospitalist leaders talking about their careers and—of course—there will be food. The first event was held in May at University of Chicago. Upcoming events will be at Rush University in Chicago on September 24 and David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA on October 22. Visit the website below for details, and share with your colleagues! www.futureofhospitalmedicine.org/events

If you can’t make it to in-person events, SHM brings some of the very best of the hospital medicine movement to your smartphone, tablet, and computer.

New at the Learning Portal: “Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment” and “Patient Safety Tools”

Free CME is available to all SHM members at www.shmlearningportal.org, and new modules are added all the time. Recently, SHM has added two new modules:

- Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment. Perioperative cardiac complications are the most widely feared medical issues for the anesthesiologist, surgeon, and medical consultant as they approach a patient with the option of surgery. To assess for pre-operative cardiac risk, hospitalists should follow a step-wise algorithm. This new module reviews the risk assessment process and enables the hospitalist to order appropriate pre-operative testing.

- Patient Safety Tools: Root Cause Analysis and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis 2015. This updated online learning module begins with a lesson and contains a 10-question post-test with accompanying answers, rationales, and references. When the participant selects an answer, immediate feedback is given explaining the correct answer.

Quality Improvement Webinars

![]()

SHM is hosting nine webinars between now and September. Hospitalists can attend the webinars in real time or download them from the SHM website at www.hospitalmedicine.org/qiwebinar.

Project BOOST webinar series:

- Project BOOST Teach-Back;

- Project BOOST Presents “Partnering with Skilled Nursing Facilities”; and

- Project BOOST Presents “Approaches to Readmission Risk Stratification.”

Glycemic control webinar series:

- Perioperative Management of Hyperglycemia;

- Hypoglycemia Management and Prevention; and

- Subcutaneous Insulin Order Sets in the Inpatient Setting: Design and Implementation.

General QI webinars:

- Quality Improvement for Hospital Medicine Groups: Self-Assessment and Self-Improvement Using the SHM Key Characteristics;

- Coaching a Quality Improvement Team: Basics for Being Sure Any QI Team and Project Are on the Right Track; and

- Elevating Provider Experience to Improve Patient Experience.

Evaluate Your Performance with the ACS Performance Improvement CME Program

![]()

The ACS PI-CME is a self-directed, web-based activity designed to help you evaluate your practice. Registration is FREE. Upon completion of the activity, participants will receive 20 CME Credits.

For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/acs and click “REGISTER.”

Career Advancers: SHM Events, Online Tools, and Programs

Hospitalists can advance their careers and the hospital medicine movement at the same time, with in-person events, online tools, and other programs designed specifically for people providing care to hospitalized patients.

When hospitalists meet face to face, good things happen. Solutions are shared. Challenges are addressed. But most importantly, SHM’s meetings are sources of energy and inspiration for the thousands of hospitalists who attend them every year.

July 23-26, San Antonio

There’s still time to register for the fast-growing national event organized specifically for pediatric hospitalists. This year, the meeting will focus on mentoring, networking, and partnerships to improve children’s health locally and globally.

Meeting attendees should plan on downloading the PHM 2015 app to get session materials, download presentations, and find their way at the conference.

![]()

October 19-22, Austin

Have you taken on more leadership responsibilities at your hospital?

Or are you ready to demonstrate that you’re ready to take them on?

SHM’s Leadership Academy has trained thousands of hospitalists to lead groups more effectively and to understand the financial realities of running a hospital

medicine practice. www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

![]()

March 6-9, 2016, San Diego

Every year, thousands of hospitalists gather for educational sessions, professional networking, and time to catch up with friends in the hospital medicine movement. Now is the time to schedule time off and register! www.hospitalmedicine2016.org

Meet-Ups for Medical Students and Residents

Chicago and Los Angeles

Are you in the Chicago or Los Angeles area? Do you know medical students and residents exploring their career options? Make sure they know about SHM’s

Future of Hospital Medicine events later this year. Each event features hospitalist leaders talking about their careers and—of course—there will be food. The first event was held in May at University of Chicago. Upcoming events will be at Rush University in Chicago on September 24 and David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA on October 22. Visit the website below for details, and share with your colleagues! www.futureofhospitalmedicine.org/events

If you can’t make it to in-person events, SHM brings some of the very best of the hospital medicine movement to your smartphone, tablet, and computer.

New at the Learning Portal: “Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment” and “Patient Safety Tools”

Free CME is available to all SHM members at www.shmlearningportal.org, and new modules are added all the time. Recently, SHM has added two new modules:

- Perioperative Cardiac Risk Assessment. Perioperative cardiac complications are the most widely feared medical issues for the anesthesiologist, surgeon, and medical consultant as they approach a patient with the option of surgery. To assess for pre-operative cardiac risk, hospitalists should follow a step-wise algorithm. This new module reviews the risk assessment process and enables the hospitalist to order appropriate pre-operative testing.

- Patient Safety Tools: Root Cause Analysis and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis 2015. This updated online learning module begins with a lesson and contains a 10-question post-test with accompanying answers, rationales, and references. When the participant selects an answer, immediate feedback is given explaining the correct answer.

Quality Improvement Webinars

![]()

SHM is hosting nine webinars between now and September. Hospitalists can attend the webinars in real time or download them from the SHM website at www.hospitalmedicine.org/qiwebinar.

Project BOOST webinar series:

- Project BOOST Teach-Back;

- Project BOOST Presents “Partnering with Skilled Nursing Facilities”; and

- Project BOOST Presents “Approaches to Readmission Risk Stratification.”

Glycemic control webinar series:

- Perioperative Management of Hyperglycemia;

- Hypoglycemia Management and Prevention; and

- Subcutaneous Insulin Order Sets in the Inpatient Setting: Design and Implementation.

General QI webinars:

- Quality Improvement for Hospital Medicine Groups: Self-Assessment and Self-Improvement Using the SHM Key Characteristics;

- Coaching a Quality Improvement Team: Basics for Being Sure Any QI Team and Project Are on the Right Track; and

- Elevating Provider Experience to Improve Patient Experience.

Evaluate Your Performance with the ACS Performance Improvement CME Program

![]()

The ACS PI-CME is a self-directed, web-based activity designed to help you evaluate your practice. Registration is FREE. Upon completion of the activity, participants will receive 20 CME Credits.

For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/acs and click “REGISTER.”

Society of Hospital Medicine Membership Ambassador Program Benefits Hospitalists

![]()

Now, through SHM’s Membership Ambassador Program, SHM members can earn 2016-2017 dues credits and special recognition for recruiting new physician, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, or affiliate members. And for every new member recruited, hospitalists will receive one entry into a grand prize drawing to receive complimentary registration to Hospital Medicine 2016 in San Diego.

Demonstrating leadership by becoming a Fellow or Senior Fellow in Hospital Medicine is another great way to move it forward—and propel your career at the same time. July and August are excellent months to begin the FHM or SFHM application process.

Click for more details and great SHM merchandise.

![]()

Now, through SHM’s Membership Ambassador Program, SHM members can earn 2016-2017 dues credits and special recognition for recruiting new physician, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, or affiliate members. And for every new member recruited, hospitalists will receive one entry into a grand prize drawing to receive complimentary registration to Hospital Medicine 2016 in San Diego.

Demonstrating leadership by becoming a Fellow or Senior Fellow in Hospital Medicine is another great way to move it forward—and propel your career at the same time. July and August are excellent months to begin the FHM or SFHM application process.

Click for more details and great SHM merchandise.

![]()

Now, through SHM’s Membership Ambassador Program, SHM members can earn 2016-2017 dues credits and special recognition for recruiting new physician, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, or affiliate members. And for every new member recruited, hospitalists will receive one entry into a grand prize drawing to receive complimentary registration to Hospital Medicine 2016 in San Diego.

Demonstrating leadership by becoming a Fellow or Senior Fellow in Hospital Medicine is another great way to move it forward—and propel your career at the same time. July and August are excellent months to begin the FHM or SFHM application process.

Click for more details and great SHM merchandise.

Proton Pump Inhibitors Commonly Prescribed, Not Always Necessary

Robert Coben, MD, academic coordinator for the Gastrointestinal Fellowship Program at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, says that when patients get admitted with chest pain for reasons other than a heart-related problem, he is frequently called on to do an endoscopy right away.

But that’s usually not the best starting point, he says.

“I would say the best test would be to just place the patient on a high-dose proton pump inhibitor once or twice a day first, to see if those symptoms resolve,” he says. “Many times we’re called in to do an upper endoscopy. … And many times that’s not really indicated unless they’re

having other alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, and weight loss.”

Marcelo Vela, MD, gastroenterologist and hepatologist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., and an associate editor with Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, adds that it’s okay to start a patient with non-cardiac chest pain on PPIs when they have concomitant, typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)—heartburn and acid regurgitation. But in patients without such symptoms, further testing is needed to confirm GERD, he says (Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(3):308–328, Table 1).

This evaluation is usually done in the outpatient setting, he says.

Dr. Vela suggests more care might be needed in the prescribing of PPIs. He says he frequently sees patients who have been hospitalized and put on a PPI without a clear reason.

“They get admitted for various reasons—DVT [deep vein thrombosis], pneumonia, whatever, and then in the hospital, they get started on a proton pump inhibitor for unclear reasons. And then they leave and they stay on it,” Dr. Vela says.

When he asks why, patients just say, “On my last hospitalization, they put me on it,” he says.

“I think you should only leave the hospital on a PPI with a very clear indication—either you found an ulcer or the patient clearly has GERD” or some other reason, he says. “They’re fairly benign medications, but if there’s no indication for it, there’s no benefit.”

Robert Coben, MD, academic coordinator for the Gastrointestinal Fellowship Program at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, says that when patients get admitted with chest pain for reasons other than a heart-related problem, he is frequently called on to do an endoscopy right away.

But that’s usually not the best starting point, he says.

“I would say the best test would be to just place the patient on a high-dose proton pump inhibitor once or twice a day first, to see if those symptoms resolve,” he says. “Many times we’re called in to do an upper endoscopy. … And many times that’s not really indicated unless they’re

having other alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, and weight loss.”

Marcelo Vela, MD, gastroenterologist and hepatologist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., and an associate editor with Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, adds that it’s okay to start a patient with non-cardiac chest pain on PPIs when they have concomitant, typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)—heartburn and acid regurgitation. But in patients without such symptoms, further testing is needed to confirm GERD, he says (Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(3):308–328, Table 1).

This evaluation is usually done in the outpatient setting, he says.

Dr. Vela suggests more care might be needed in the prescribing of PPIs. He says he frequently sees patients who have been hospitalized and put on a PPI without a clear reason.

“They get admitted for various reasons—DVT [deep vein thrombosis], pneumonia, whatever, and then in the hospital, they get started on a proton pump inhibitor for unclear reasons. And then they leave and they stay on it,” Dr. Vela says.

When he asks why, patients just say, “On my last hospitalization, they put me on it,” he says.

“I think you should only leave the hospital on a PPI with a very clear indication—either you found an ulcer or the patient clearly has GERD” or some other reason, he says. “They’re fairly benign medications, but if there’s no indication for it, there’s no benefit.”

Robert Coben, MD, academic coordinator for the Gastrointestinal Fellowship Program at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, says that when patients get admitted with chest pain for reasons other than a heart-related problem, he is frequently called on to do an endoscopy right away.

But that’s usually not the best starting point, he says.

“I would say the best test would be to just place the patient on a high-dose proton pump inhibitor once or twice a day first, to see if those symptoms resolve,” he says. “Many times we’re called in to do an upper endoscopy. … And many times that’s not really indicated unless they’re

having other alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, and weight loss.”

Marcelo Vela, MD, gastroenterologist and hepatologist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., and an associate editor with Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, adds that it’s okay to start a patient with non-cardiac chest pain on PPIs when they have concomitant, typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)—heartburn and acid regurgitation. But in patients without such symptoms, further testing is needed to confirm GERD, he says (Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(3):308–328, Table 1).

This evaluation is usually done in the outpatient setting, he says.

Dr. Vela suggests more care might be needed in the prescribing of PPIs. He says he frequently sees patients who have been hospitalized and put on a PPI without a clear reason.

“They get admitted for various reasons—DVT [deep vein thrombosis], pneumonia, whatever, and then in the hospital, they get started on a proton pump inhibitor for unclear reasons. And then they leave and they stay on it,” Dr. Vela says.

When he asks why, patients just say, “On my last hospitalization, they put me on it,” he says.

“I think you should only leave the hospital on a PPI with a very clear indication—either you found an ulcer or the patient clearly has GERD” or some other reason, he says. “They’re fairly benign medications, but if there’s no indication for it, there’s no benefit.”

ProMISe Trial Adds Skepticism to Early Goal-Directed Therapy for Sepsis

Clinical question: Does EGDT for sepsis reduce mortality at 90 days compared with standard therapy?

Background: EGDT is recommended in international guidelines for the resuscitation of patients presenting with early septic shock; however, adoption has been limited, and uncertainty about its effectiveness remains.

Study design: Pragmatic, multicenter, randomized controlled trial (RCT) with intention to treat analysis.

Setting: Fifty-six National Health Service EDs in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: ProMISe trial enrolled 1,251 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock and patients were randomized to usual-care group (as determined by the treating clinicians) or algorithm-driven EGDT, which included continuous central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) using the original EGDT protocol. The primary outcome of all-cause mortality at 90 days was not significantly different between the two groups: 29.5% in EGDT and 29.2% in the usual-care group (P=0.9). This translated into a relative risk of 1.01% (95% CI 0.85-1.20) in the EGDT group. There were no meaningful differences in secondary outcomes.

Both groups in this study were actually well matched for most interventions. The main difference was in the use of continuous ScvO2 measurement and central venous pressure to guide management. Perhaps we should not completely dismiss the term EGDT. Most of our “usual care” consists of early intervention and goal-directed therapy.

Bottom line: In patients identified early with septic shock, the use of EGDT vs. “usual” care did not result in a statistical difference in 90-day mortality.

Citation: Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, et al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1301-1311.

Clinical question: Does EGDT for sepsis reduce mortality at 90 days compared with standard therapy?

Background: EGDT is recommended in international guidelines for the resuscitation of patients presenting with early septic shock; however, adoption has been limited, and uncertainty about its effectiveness remains.

Study design: Pragmatic, multicenter, randomized controlled trial (RCT) with intention to treat analysis.

Setting: Fifty-six National Health Service EDs in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: ProMISe trial enrolled 1,251 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock and patients were randomized to usual-care group (as determined by the treating clinicians) or algorithm-driven EGDT, which included continuous central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) using the original EGDT protocol. The primary outcome of all-cause mortality at 90 days was not significantly different between the two groups: 29.5% in EGDT and 29.2% in the usual-care group (P=0.9). This translated into a relative risk of 1.01% (95% CI 0.85-1.20) in the EGDT group. There were no meaningful differences in secondary outcomes.

Both groups in this study were actually well matched for most interventions. The main difference was in the use of continuous ScvO2 measurement and central venous pressure to guide management. Perhaps we should not completely dismiss the term EGDT. Most of our “usual care” consists of early intervention and goal-directed therapy.

Bottom line: In patients identified early with septic shock, the use of EGDT vs. “usual” care did not result in a statistical difference in 90-day mortality.

Citation: Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, et al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1301-1311.

Clinical question: Does EGDT for sepsis reduce mortality at 90 days compared with standard therapy?

Background: EGDT is recommended in international guidelines for the resuscitation of patients presenting with early septic shock; however, adoption has been limited, and uncertainty about its effectiveness remains.

Study design: Pragmatic, multicenter, randomized controlled trial (RCT) with intention to treat analysis.

Setting: Fifty-six National Health Service EDs in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: ProMISe trial enrolled 1,251 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock and patients were randomized to usual-care group (as determined by the treating clinicians) or algorithm-driven EGDT, which included continuous central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) using the original EGDT protocol. The primary outcome of all-cause mortality at 90 days was not significantly different between the two groups: 29.5% in EGDT and 29.2% in the usual-care group (P=0.9). This translated into a relative risk of 1.01% (95% CI 0.85-1.20) in the EGDT group. There were no meaningful differences in secondary outcomes.