User login

School-based CBT program reduces depression, suicidality

Emotionally distressed Canadian students who completed a school-based cognitive-behavioral therapy program experienced significant improvements in depression and suicidality, according to a multicenter prospective study published in PLoS One.

At the end of the pilot program entitled Empowering a Multimodal Pathway Toward Healthy Youth (EMPATHY), the number of students who were actively suicidal fell by 73%, and depression scores dropped by about 15% across all schools and age groups, Dr. Peter Silverstone, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said in an interview.

Depressive disorders affect at least 10% of U.S. young people, and about 8% who live in the United States attempt suicide each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To explore solutions, Dr. Silverstone and his associates used tablets loaded with a specially designed software “app” to screen 3,244 Canadian students aged 11-18 years (6th-12th grades). The students attended the five middle schools and high schools in a single Alberta school district, and the screen incorporated questions from several short, free mental health scales (PLoS One 2015 [doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125527]).

Trained staff then interviewed students who were assessed as actively suicidal and met with them and their parents in order to create a safety plan, make referrals to appropriate health services, and invite students to participate in the guided Internet cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) program. Students who scored in the top 10% of a combined measure of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem also were invited to participate in the CBT program, and an eight-session version of the program was deployed for all seventh and eighth graders.

Among 503 high-risk students who were offered the CBT program, 151 (30%) enrolled, and 90% completed the program.

Parents and students had only a week to sign and return the consent forms, which led to the low participation rate in the pilot phase of the study, Dr. Silverstone noted. “We changed the processes after the pilot and got much higher acceptance rates, nearer to 70% percent.”

At 12-week follow-up, program participants had significantly improved from baseline, compared with nonparticipants in terms of the combined mental health, depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and quality of life scales, but not in terms of self-reported use of drugs, alcohol, or tobacco, the investigators reported.

Of the 104 actively suicidal students at baseline who completed both assessments, 76 (73%) were in the no-risk group at 12 weeks, a significant difference.

The results are promising, but their durability remains unclear, as other studies have reported strong short-term results that did not hold several years later, the investigators noted.

“All staff hired in the schools to implement the program had to have some experience working with youth, and many had an undergraduate degree,” the investigators added. “However, it is important to note that they were specifically not highly trained individuals (such as psychologists or teachers), as it was felt that it would not be feasible for widespread expansion if such highly trained (and expensive) staff were required.”

“We have follow-up data for 15 months, until the end of June 2015, that we hope to be able to start analyzing before the end of the year,” Dr. Silverstone said. But in the meantime, the new provincial government has cut the program’s funding, which he called a “major disappointment. We have had to abandon all further plans for the program,” he said, adding that it will terminate at the end of 2015.

Alberta Health Services funded the study. The researchers declared having no relevant competing interests.

Emotionally distressed Canadian students who completed a school-based cognitive-behavioral therapy program experienced significant improvements in depression and suicidality, according to a multicenter prospective study published in PLoS One.

At the end of the pilot program entitled Empowering a Multimodal Pathway Toward Healthy Youth (EMPATHY), the number of students who were actively suicidal fell by 73%, and depression scores dropped by about 15% across all schools and age groups, Dr. Peter Silverstone, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said in an interview.

Depressive disorders affect at least 10% of U.S. young people, and about 8% who live in the United States attempt suicide each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To explore solutions, Dr. Silverstone and his associates used tablets loaded with a specially designed software “app” to screen 3,244 Canadian students aged 11-18 years (6th-12th grades). The students attended the five middle schools and high schools in a single Alberta school district, and the screen incorporated questions from several short, free mental health scales (PLoS One 2015 [doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125527]).

Trained staff then interviewed students who were assessed as actively suicidal and met with them and their parents in order to create a safety plan, make referrals to appropriate health services, and invite students to participate in the guided Internet cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) program. Students who scored in the top 10% of a combined measure of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem also were invited to participate in the CBT program, and an eight-session version of the program was deployed for all seventh and eighth graders.

Among 503 high-risk students who were offered the CBT program, 151 (30%) enrolled, and 90% completed the program.

Parents and students had only a week to sign and return the consent forms, which led to the low participation rate in the pilot phase of the study, Dr. Silverstone noted. “We changed the processes after the pilot and got much higher acceptance rates, nearer to 70% percent.”

At 12-week follow-up, program participants had significantly improved from baseline, compared with nonparticipants in terms of the combined mental health, depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and quality of life scales, but not in terms of self-reported use of drugs, alcohol, or tobacco, the investigators reported.

Of the 104 actively suicidal students at baseline who completed both assessments, 76 (73%) were in the no-risk group at 12 weeks, a significant difference.

The results are promising, but their durability remains unclear, as other studies have reported strong short-term results that did not hold several years later, the investigators noted.

“All staff hired in the schools to implement the program had to have some experience working with youth, and many had an undergraduate degree,” the investigators added. “However, it is important to note that they were specifically not highly trained individuals (such as psychologists or teachers), as it was felt that it would not be feasible for widespread expansion if such highly trained (and expensive) staff were required.”

“We have follow-up data for 15 months, until the end of June 2015, that we hope to be able to start analyzing before the end of the year,” Dr. Silverstone said. But in the meantime, the new provincial government has cut the program’s funding, which he called a “major disappointment. We have had to abandon all further plans for the program,” he said, adding that it will terminate at the end of 2015.

Alberta Health Services funded the study. The researchers declared having no relevant competing interests.

Emotionally distressed Canadian students who completed a school-based cognitive-behavioral therapy program experienced significant improvements in depression and suicidality, according to a multicenter prospective study published in PLoS One.

At the end of the pilot program entitled Empowering a Multimodal Pathway Toward Healthy Youth (EMPATHY), the number of students who were actively suicidal fell by 73%, and depression scores dropped by about 15% across all schools and age groups, Dr. Peter Silverstone, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said in an interview.

Depressive disorders affect at least 10% of U.S. young people, and about 8% who live in the United States attempt suicide each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To explore solutions, Dr. Silverstone and his associates used tablets loaded with a specially designed software “app” to screen 3,244 Canadian students aged 11-18 years (6th-12th grades). The students attended the five middle schools and high schools in a single Alberta school district, and the screen incorporated questions from several short, free mental health scales (PLoS One 2015 [doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125527]).

Trained staff then interviewed students who were assessed as actively suicidal and met with them and their parents in order to create a safety plan, make referrals to appropriate health services, and invite students to participate in the guided Internet cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) program. Students who scored in the top 10% of a combined measure of depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem also were invited to participate in the CBT program, and an eight-session version of the program was deployed for all seventh and eighth graders.

Among 503 high-risk students who were offered the CBT program, 151 (30%) enrolled, and 90% completed the program.

Parents and students had only a week to sign and return the consent forms, which led to the low participation rate in the pilot phase of the study, Dr. Silverstone noted. “We changed the processes after the pilot and got much higher acceptance rates, nearer to 70% percent.”

At 12-week follow-up, program participants had significantly improved from baseline, compared with nonparticipants in terms of the combined mental health, depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and quality of life scales, but not in terms of self-reported use of drugs, alcohol, or tobacco, the investigators reported.

Of the 104 actively suicidal students at baseline who completed both assessments, 76 (73%) were in the no-risk group at 12 weeks, a significant difference.

The results are promising, but their durability remains unclear, as other studies have reported strong short-term results that did not hold several years later, the investigators noted.

“All staff hired in the schools to implement the program had to have some experience working with youth, and many had an undergraduate degree,” the investigators added. “However, it is important to note that they were specifically not highly trained individuals (such as psychologists or teachers), as it was felt that it would not be feasible for widespread expansion if such highly trained (and expensive) staff were required.”

“We have follow-up data for 15 months, until the end of June 2015, that we hope to be able to start analyzing before the end of the year,” Dr. Silverstone said. But in the meantime, the new provincial government has cut the program’s funding, which he called a “major disappointment. We have had to abandon all further plans for the program,” he said, adding that it will terminate at the end of 2015.

Alberta Health Services funded the study. The researchers declared having no relevant competing interests.

FROM PLOS ONE

Key clinical point: A school-based cognitive-behavioral therapy program was tied to substantial declines in adolescent depression and suicidality.

Major finding: At 12-week follow-up, the number of students who were actively suicidal was 73% lower than at baseline.

Data source: Multicenter Canadian prospective study of 3,244 students aged 11-18 years.

Disclosures: Alberta Health Services funded the study. The researchers declared having no relevant competing interests.

Cutaneous Infection With Mycobacterium kansasii in a Patient With Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Sweet Syndrome

To the Editor:

A 68-year-old man with a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and recurrent Sweet syndrome presented with left leg lesions of 3 months’ duration. The lesions originated as a solitary nodule on the left calf and subsequently developed into multiple nonpainful, nonpruritic, erythematous plaques of varying sizes with violaceous coloration and overlying necrotic eschar, occupying the entire anterior aspect of the left lower leg and left popliteal fossa (Figure). The patient denied any trauma or associated symptoms but had a history of Sweet syndrome that manifested as lesions on the arms and legs for which he took 6 mg of prednisone daily to prevent recurrence.

Histologic examination revealed nodular and diffuse chronic granulomatous and acute inflammatory infiltrate. Stains for bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast bacilli were negative. Cultures subsequently grew Mycobacterium kansasii, and the patient was started on isoniazid 300 mg daily, rifampin 600 mg daily, ethambutol 800 mg daily, and pyridoxine 50 mg daily. Chest radiograph and computed tomography showed no evidence of pulmonary disease and 2 blood cultures were negative for growth. The patient subsequently developed weakness that he attributed to the antibiotics and he decided to discontinue all treatment.

At 11 months the lesions showed no change; however, magnetic resonance imaging of the leg was suggestive of osteomyelitis. The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with planned addition of isoniazid. The patient refused any additional antibiotics but agreed to continue the clarithromycin treatment for one year. He was subsequently lost to dermatology follow-up.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection is a rare sequela of hematologic malignancy, seen in only 1.5% of patients.1 The NTM most commonly seen in hematologic malignancy are generally the fast-growing species Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium chelonae, Mycobacterium fortuitum, or Mycobacterium phlei, rather than slow growers Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium marinum, and Mycobacterium xenopi. Mycobacterium kansasii infection, such as seen in our patient, accounts for only 18% of cases.1 This case is further distinguished by the fact that cutaneous infections with NTM also are generally caused by fast-growing organisms such as Mycobacterium abscessus-chelonae complex and M fortuitum, rather than the slow-growing M kansasii.2,3

Mycobacterium kansasii is a slow-growing, acid-fast bacillus found in local water reservoirs, swimming pools, sewers, and tap water where it can live for up to 12 months.2,4,5Mycobacterium kansasii is traditionally considered the most virulent NTM.3,6 It most frequently causes a pulmonary infection in the immunosuppressed and patients with chronic bronchopulmonary disease.6,7 Disseminated disease is less common and is primarily seen in immunocompromised patients, particularly in human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, transplant recipients, and patients with hematologic malignancies.1,6,8 Disseminated disease rarely has been seen in patients with normal immune function.2,3

Cutaneous M kansasii infection has only infrequently been described. Most patients tend to be middle-aged men, with a median affected age of 43 years.2,7,9,10 One review of cutaneous cases found that 72% had some form of altered immunity and more than 50% of those patients were on chronic steroids. The same review found that of the cases of cutaneous M kansasii in patients with altered immunity, only 30% had disseminated disease.10 Our patient was immunocompromised but showed no evidence of disseminated disease, as displayed by negative chest radiograph and computed tomography, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative blood cultures. As a 68-year-old man with myelodysplastic syndrome on chronic steroids with no disseminated disease, our patient fits well into these demographics, aside from his advanced age.

Cutaneous M kansasii infection has a variable presentation, manifesting as solitary lesions, nodules, pustules, seromas, erythematous plaques, verrucous lesions, ulcers, and as cellulitis.5,7,9-12 Immune competent individuals were more likely to present with raised lesions or ulcers, whereas immune compromised individuals had a more diffuse presentation of cellulitis or seromas with variable histology.6,8 Our patient, though immune compromised, presented with multiple erythematous plaques with eschars, which further endorses having a high clinical suspicion, as the lesions display marked heterogeneity.

Treatment of M kansasii infection consists of at least 1 year of isoniazid 300 mg daily, rifampin 600 mg daily, and ethambutol 15 mg/kg daily, with possible addition of streptomycin.8,13Mycobacterium kansasii infection necessitates multidrug treatment due to the broad range of resistance exhibited by different isolated strains.14

Response to treatment in cutaneous M kansasii greatly depends on the underlying disease state of the individual. Generally, immune competent individuals do very well, while the course in immune compromised patients depends on their degree of illness. Patients with disseminated disease generally do poorly.4,7,10 In at least one case of cutaneous disease, dissemination developed as a sequela, thus suggesting treatment is needed even in stable lesions.2 Dissemination was a concern with our patient given the magnetic resonance imaging findings suggestive of osteomyelitis. Although treatment generally consists of triple therapy with isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol, given the high frequency of adverse effects due to isoniazid or rifampin, as was seen in our patient, the drug regimen might have to be altered to suit the patient. Susceptibility testing is desirable to aid in tailoring the treatment.8,13 Furthermore, as the duration of treatment is at least 1 year, diligent follow-up must be maintained to avoid incomplete treatment.

The unpredictable presentation of cutaneous M kansasii infection coupled with the variable history necessitates a high level of clinical suspicion and a low threshold for culturing lesions. Furthermore, the long duration and complexity of the antibiotic regimen and the high incidence of adverse reactions demands strict follow-up, especially given the risk for progression to disseminated disease.

1. Chen CY, Sheng WH, Lai CC. Mycobacterial infections in adult patients with hematological malignancy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1059-1066.

2. Han SH, Kim KM, Chin BS, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium kansasii infection associated with skin lesions: a case report and comprehensive review of the literature. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:304-308.

3. Razavi B, Cleveland MG. Cutaneous infection due to Mycobacterium kansasii. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;38:173-175.

4. Portaels F. Epidemiology of mycobacterial diseases. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:207-222.

5. Nomura Y, Nishie W, Shibaki A, et al. Disseminated cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection in a patient infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:625-626.

6. Bloch KC, Zwerling L, Pletcher MJ, et al. Incidence and clinical implications of isolation of Mycobacterium kansasii: results of a 5-year, population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:698-704.

7. Breathnach A, Levell N, Munro C, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:812-817.

8. Pintado V, Gómez-Mampaso E, Martín-Dávila P. Mycobacterium kansasii infection in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:582-586.

9. Stengem J, Grande KK, Hsu S. Localized primary cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection in an immunocompromised patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):854-856.

10. Czelusta A, Moore AY. Cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2, pt 2):359-363.

11. Curcó N, Pagerols X, Gómez L, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii infection limited to the skin in a patient with AIDS. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:324-326.

12. Hanke CW, Temofeew RK, Slama SL. Mycobacterium kansasii infection with multiple cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(5, pt 2):1122-1128.

13. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculousmycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

14. da Silva Telles MA, Chimara E, Ferrazoli L, Riley LW. Mycobacterium kansasii: antibiotic susceptibility and PCR-restriction analysis of clinical isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:975-979.

To the Editor:

A 68-year-old man with a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and recurrent Sweet syndrome presented with left leg lesions of 3 months’ duration. The lesions originated as a solitary nodule on the left calf and subsequently developed into multiple nonpainful, nonpruritic, erythematous plaques of varying sizes with violaceous coloration and overlying necrotic eschar, occupying the entire anterior aspect of the left lower leg and left popliteal fossa (Figure). The patient denied any trauma or associated symptoms but had a history of Sweet syndrome that manifested as lesions on the arms and legs for which he took 6 mg of prednisone daily to prevent recurrence.

Histologic examination revealed nodular and diffuse chronic granulomatous and acute inflammatory infiltrate. Stains for bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast bacilli were negative. Cultures subsequently grew Mycobacterium kansasii, and the patient was started on isoniazid 300 mg daily, rifampin 600 mg daily, ethambutol 800 mg daily, and pyridoxine 50 mg daily. Chest radiograph and computed tomography showed no evidence of pulmonary disease and 2 blood cultures were negative for growth. The patient subsequently developed weakness that he attributed to the antibiotics and he decided to discontinue all treatment.

At 11 months the lesions showed no change; however, magnetic resonance imaging of the leg was suggestive of osteomyelitis. The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with planned addition of isoniazid. The patient refused any additional antibiotics but agreed to continue the clarithromycin treatment for one year. He was subsequently lost to dermatology follow-up.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection is a rare sequela of hematologic malignancy, seen in only 1.5% of patients.1 The NTM most commonly seen in hematologic malignancy are generally the fast-growing species Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium chelonae, Mycobacterium fortuitum, or Mycobacterium phlei, rather than slow growers Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium marinum, and Mycobacterium xenopi. Mycobacterium kansasii infection, such as seen in our patient, accounts for only 18% of cases.1 This case is further distinguished by the fact that cutaneous infections with NTM also are generally caused by fast-growing organisms such as Mycobacterium abscessus-chelonae complex and M fortuitum, rather than the slow-growing M kansasii.2,3

Mycobacterium kansasii is a slow-growing, acid-fast bacillus found in local water reservoirs, swimming pools, sewers, and tap water where it can live for up to 12 months.2,4,5Mycobacterium kansasii is traditionally considered the most virulent NTM.3,6 It most frequently causes a pulmonary infection in the immunosuppressed and patients with chronic bronchopulmonary disease.6,7 Disseminated disease is less common and is primarily seen in immunocompromised patients, particularly in human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, transplant recipients, and patients with hematologic malignancies.1,6,8 Disseminated disease rarely has been seen in patients with normal immune function.2,3

Cutaneous M kansasii infection has only infrequently been described. Most patients tend to be middle-aged men, with a median affected age of 43 years.2,7,9,10 One review of cutaneous cases found that 72% had some form of altered immunity and more than 50% of those patients were on chronic steroids. The same review found that of the cases of cutaneous M kansasii in patients with altered immunity, only 30% had disseminated disease.10 Our patient was immunocompromised but showed no evidence of disseminated disease, as displayed by negative chest radiograph and computed tomography, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative blood cultures. As a 68-year-old man with myelodysplastic syndrome on chronic steroids with no disseminated disease, our patient fits well into these demographics, aside from his advanced age.

Cutaneous M kansasii infection has a variable presentation, manifesting as solitary lesions, nodules, pustules, seromas, erythematous plaques, verrucous lesions, ulcers, and as cellulitis.5,7,9-12 Immune competent individuals were more likely to present with raised lesions or ulcers, whereas immune compromised individuals had a more diffuse presentation of cellulitis or seromas with variable histology.6,8 Our patient, though immune compromised, presented with multiple erythematous plaques with eschars, which further endorses having a high clinical suspicion, as the lesions display marked heterogeneity.

Treatment of M kansasii infection consists of at least 1 year of isoniazid 300 mg daily, rifampin 600 mg daily, and ethambutol 15 mg/kg daily, with possible addition of streptomycin.8,13Mycobacterium kansasii infection necessitates multidrug treatment due to the broad range of resistance exhibited by different isolated strains.14

Response to treatment in cutaneous M kansasii greatly depends on the underlying disease state of the individual. Generally, immune competent individuals do very well, while the course in immune compromised patients depends on their degree of illness. Patients with disseminated disease generally do poorly.4,7,10 In at least one case of cutaneous disease, dissemination developed as a sequela, thus suggesting treatment is needed even in stable lesions.2 Dissemination was a concern with our patient given the magnetic resonance imaging findings suggestive of osteomyelitis. Although treatment generally consists of triple therapy with isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol, given the high frequency of adverse effects due to isoniazid or rifampin, as was seen in our patient, the drug regimen might have to be altered to suit the patient. Susceptibility testing is desirable to aid in tailoring the treatment.8,13 Furthermore, as the duration of treatment is at least 1 year, diligent follow-up must be maintained to avoid incomplete treatment.

The unpredictable presentation of cutaneous M kansasii infection coupled with the variable history necessitates a high level of clinical suspicion and a low threshold for culturing lesions. Furthermore, the long duration and complexity of the antibiotic regimen and the high incidence of adverse reactions demands strict follow-up, especially given the risk for progression to disseminated disease.

To the Editor:

A 68-year-old man with a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and recurrent Sweet syndrome presented with left leg lesions of 3 months’ duration. The lesions originated as a solitary nodule on the left calf and subsequently developed into multiple nonpainful, nonpruritic, erythematous plaques of varying sizes with violaceous coloration and overlying necrotic eschar, occupying the entire anterior aspect of the left lower leg and left popliteal fossa (Figure). The patient denied any trauma or associated symptoms but had a history of Sweet syndrome that manifested as lesions on the arms and legs for which he took 6 mg of prednisone daily to prevent recurrence.

Histologic examination revealed nodular and diffuse chronic granulomatous and acute inflammatory infiltrate. Stains for bacteria, fungi, and acid-fast bacilli were negative. Cultures subsequently grew Mycobacterium kansasii, and the patient was started on isoniazid 300 mg daily, rifampin 600 mg daily, ethambutol 800 mg daily, and pyridoxine 50 mg daily. Chest radiograph and computed tomography showed no evidence of pulmonary disease and 2 blood cultures were negative for growth. The patient subsequently developed weakness that he attributed to the antibiotics and he decided to discontinue all treatment.

At 11 months the lesions showed no change; however, magnetic resonance imaging of the leg was suggestive of osteomyelitis. The patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with planned addition of isoniazid. The patient refused any additional antibiotics but agreed to continue the clarithromycin treatment for one year. He was subsequently lost to dermatology follow-up.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infection is a rare sequela of hematologic malignancy, seen in only 1.5% of patients.1 The NTM most commonly seen in hematologic malignancy are generally the fast-growing species Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium chelonae, Mycobacterium fortuitum, or Mycobacterium phlei, rather than slow growers Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium marinum, and Mycobacterium xenopi. Mycobacterium kansasii infection, such as seen in our patient, accounts for only 18% of cases.1 This case is further distinguished by the fact that cutaneous infections with NTM also are generally caused by fast-growing organisms such as Mycobacterium abscessus-chelonae complex and M fortuitum, rather than the slow-growing M kansasii.2,3

Mycobacterium kansasii is a slow-growing, acid-fast bacillus found in local water reservoirs, swimming pools, sewers, and tap water where it can live for up to 12 months.2,4,5Mycobacterium kansasii is traditionally considered the most virulent NTM.3,6 It most frequently causes a pulmonary infection in the immunosuppressed and patients with chronic bronchopulmonary disease.6,7 Disseminated disease is less common and is primarily seen in immunocompromised patients, particularly in human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, transplant recipients, and patients with hematologic malignancies.1,6,8 Disseminated disease rarely has been seen in patients with normal immune function.2,3

Cutaneous M kansasii infection has only infrequently been described. Most patients tend to be middle-aged men, with a median affected age of 43 years.2,7,9,10 One review of cutaneous cases found that 72% had some form of altered immunity and more than 50% of those patients were on chronic steroids. The same review found that of the cases of cutaneous M kansasii in patients with altered immunity, only 30% had disseminated disease.10 Our patient was immunocompromised but showed no evidence of disseminated disease, as displayed by negative chest radiograph and computed tomography, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative blood cultures. As a 68-year-old man with myelodysplastic syndrome on chronic steroids with no disseminated disease, our patient fits well into these demographics, aside from his advanced age.

Cutaneous M kansasii infection has a variable presentation, manifesting as solitary lesions, nodules, pustules, seromas, erythematous plaques, verrucous lesions, ulcers, and as cellulitis.5,7,9-12 Immune competent individuals were more likely to present with raised lesions or ulcers, whereas immune compromised individuals had a more diffuse presentation of cellulitis or seromas with variable histology.6,8 Our patient, though immune compromised, presented with multiple erythematous plaques with eschars, which further endorses having a high clinical suspicion, as the lesions display marked heterogeneity.

Treatment of M kansasii infection consists of at least 1 year of isoniazid 300 mg daily, rifampin 600 mg daily, and ethambutol 15 mg/kg daily, with possible addition of streptomycin.8,13Mycobacterium kansasii infection necessitates multidrug treatment due to the broad range of resistance exhibited by different isolated strains.14

Response to treatment in cutaneous M kansasii greatly depends on the underlying disease state of the individual. Generally, immune competent individuals do very well, while the course in immune compromised patients depends on their degree of illness. Patients with disseminated disease generally do poorly.4,7,10 In at least one case of cutaneous disease, dissemination developed as a sequela, thus suggesting treatment is needed even in stable lesions.2 Dissemination was a concern with our patient given the magnetic resonance imaging findings suggestive of osteomyelitis. Although treatment generally consists of triple therapy with isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol, given the high frequency of adverse effects due to isoniazid or rifampin, as was seen in our patient, the drug regimen might have to be altered to suit the patient. Susceptibility testing is desirable to aid in tailoring the treatment.8,13 Furthermore, as the duration of treatment is at least 1 year, diligent follow-up must be maintained to avoid incomplete treatment.

The unpredictable presentation of cutaneous M kansasii infection coupled with the variable history necessitates a high level of clinical suspicion and a low threshold for culturing lesions. Furthermore, the long duration and complexity of the antibiotic regimen and the high incidence of adverse reactions demands strict follow-up, especially given the risk for progression to disseminated disease.

1. Chen CY, Sheng WH, Lai CC. Mycobacterial infections in adult patients with hematological malignancy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1059-1066.

2. Han SH, Kim KM, Chin BS, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium kansasii infection associated with skin lesions: a case report and comprehensive review of the literature. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:304-308.

3. Razavi B, Cleveland MG. Cutaneous infection due to Mycobacterium kansasii. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;38:173-175.

4. Portaels F. Epidemiology of mycobacterial diseases. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:207-222.

5. Nomura Y, Nishie W, Shibaki A, et al. Disseminated cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection in a patient infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:625-626.

6. Bloch KC, Zwerling L, Pletcher MJ, et al. Incidence and clinical implications of isolation of Mycobacterium kansasii: results of a 5-year, population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:698-704.

7. Breathnach A, Levell N, Munro C, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:812-817.

8. Pintado V, Gómez-Mampaso E, Martín-Dávila P. Mycobacterium kansasii infection in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:582-586.

9. Stengem J, Grande KK, Hsu S. Localized primary cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection in an immunocompromised patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):854-856.

10. Czelusta A, Moore AY. Cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2, pt 2):359-363.

11. Curcó N, Pagerols X, Gómez L, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii infection limited to the skin in a patient with AIDS. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:324-326.

12. Hanke CW, Temofeew RK, Slama SL. Mycobacterium kansasii infection with multiple cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(5, pt 2):1122-1128.

13. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculousmycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

14. da Silva Telles MA, Chimara E, Ferrazoli L, Riley LW. Mycobacterium kansasii: antibiotic susceptibility and PCR-restriction analysis of clinical isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:975-979.

1. Chen CY, Sheng WH, Lai CC. Mycobacterial infections in adult patients with hematological malignancy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1059-1066.

2. Han SH, Kim KM, Chin BS, et al. Disseminated Mycobacterium kansasii infection associated with skin lesions: a case report and comprehensive review of the literature. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:304-308.

3. Razavi B, Cleveland MG. Cutaneous infection due to Mycobacterium kansasii. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;38:173-175.

4. Portaels F. Epidemiology of mycobacterial diseases. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:207-222.

5. Nomura Y, Nishie W, Shibaki A, et al. Disseminated cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection in a patient infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:625-626.

6. Bloch KC, Zwerling L, Pletcher MJ, et al. Incidence and clinical implications of isolation of Mycobacterium kansasii: results of a 5-year, population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:698-704.

7. Breathnach A, Levell N, Munro C, et al. Cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:812-817.

8. Pintado V, Gómez-Mampaso E, Martín-Dávila P. Mycobacterium kansasii infection in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:582-586.

9. Stengem J, Grande KK, Hsu S. Localized primary cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection in an immunocompromised patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):854-856.

10. Czelusta A, Moore AY. Cutaneous Mycobacterium kansasii infection in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40(2, pt 2):359-363.

11. Curcó N, Pagerols X, Gómez L, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii infection limited to the skin in a patient with AIDS. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:324-326.

12. Hanke CW, Temofeew RK, Slama SL. Mycobacterium kansasii infection with multiple cutaneous lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(5, pt 2):1122-1128.

13. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculousmycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

14. da Silva Telles MA, Chimara E, Ferrazoli L, Riley LW. Mycobacterium kansasii: antibiotic susceptibility and PCR-restriction analysis of clinical isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:975-979.

Women with ACS showed improved outcomes, but remain underrepresented in trials

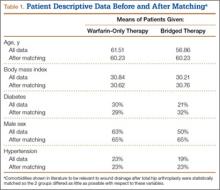

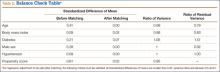

Though acute coronary syndromes are the leading cause of death in U.S. women, an analysis of clinical trials showed that enrollment among women remained disproportionately low from 1994 to 2010, reported Dr. Kristian Kragholm and coauthors at Duke Clinical Research Institute.

An analysis of data in 76,148 non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome patients from 11 phase III clinical trials found that women comprised just 33.3% of participants, which did not change significantly over the 17-year period. Women consistently had higher incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure, the authors reported.

Use of ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, thienopyridines, beta-blockers, and lipid-lowering drugs significantly increased over time for both sexes, as did use of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. Observed in-hospital, 30-day, and 6-month mortality decreased significantly in both men and women, Dr. Kragholm and colleagues said.

The findings suggest that “current efforts to representatively enroll women in NSTE ACS trials are insufficient,” the authors wrote. “Because safety and efficacy findings may differ according to sex, this disparity could undermine generalizability of clinical trial results to treatment of the overall NSTE ACS population.”

Read the full article here.

Though acute coronary syndromes are the leading cause of death in U.S. women, an analysis of clinical trials showed that enrollment among women remained disproportionately low from 1994 to 2010, reported Dr. Kristian Kragholm and coauthors at Duke Clinical Research Institute.

An analysis of data in 76,148 non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome patients from 11 phase III clinical trials found that women comprised just 33.3% of participants, which did not change significantly over the 17-year period. Women consistently had higher incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure, the authors reported.

Use of ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, thienopyridines, beta-blockers, and lipid-lowering drugs significantly increased over time for both sexes, as did use of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. Observed in-hospital, 30-day, and 6-month mortality decreased significantly in both men and women, Dr. Kragholm and colleagues said.

The findings suggest that “current efforts to representatively enroll women in NSTE ACS trials are insufficient,” the authors wrote. “Because safety and efficacy findings may differ according to sex, this disparity could undermine generalizability of clinical trial results to treatment of the overall NSTE ACS population.”

Read the full article here.

Though acute coronary syndromes are the leading cause of death in U.S. women, an analysis of clinical trials showed that enrollment among women remained disproportionately low from 1994 to 2010, reported Dr. Kristian Kragholm and coauthors at Duke Clinical Research Institute.

An analysis of data in 76,148 non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome patients from 11 phase III clinical trials found that women comprised just 33.3% of participants, which did not change significantly over the 17-year period. Women consistently had higher incidence of diabetes, hypertension, and heart failure, the authors reported.

Use of ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, thienopyridines, beta-blockers, and lipid-lowering drugs significantly increased over time for both sexes, as did use of coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. Observed in-hospital, 30-day, and 6-month mortality decreased significantly in both men and women, Dr. Kragholm and colleagues said.

The findings suggest that “current efforts to representatively enroll women in NSTE ACS trials are insufficient,” the authors wrote. “Because safety and efficacy findings may differ according to sex, this disparity could undermine generalizability of clinical trial results to treatment of the overall NSTE ACS population.”

Read the full article here.

Three Cheers for B3?

At the recent American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Martin et al presented data from the Australian Oral Nicotinamide to Reduce Actinic Cancer (ONTRAC) study. This prospective double-blind, randomized, controlled trial examined 386 immunocompetent patients with 2 or more nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) in the last 5 years (average, 8). The patients were randomized to receive oral nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily or placebo for 1 year, resulting in significant reduction of new NMSCs (average rate 1.77 vs 2.42; relative rate reduction, 23%; P=.02), with similar results for basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Actinic keratosis counts were reduced throughout the year by up to 20%, peaking at 9 months. No differences in adverse events were noted between the treatment and placebo groups.

What’s the issue?

High-risk NMSC patients present a challenge to dermatologists, as their need for constant surveillance, field therapy for actinic keratoses, and revolving visits between skin examinations and procedural modalities such as Mohs micrographic surgery can be staggering. Chemopreventive strategies pose difficulties, especially for elderly patients, due to tolerability and adherence, skin irritation and cosmetic limitations of topical therapies such as 5-fluorouracil, and inadequacy or financial inaccessibility of oral therapies such as acitretin.

Nicotinamide is a confusing supplement, as it is also called niacinamide. One of the 2 forms of vitamin B3, nicotinic acid (or niacin) is the other form and can be converted to nicotinamide in the body. It has cholesterol and vasodilatory/flushing effects that nicotinamide itself does not. Therefore, these supplement subtypes are not generally interchangeable.

Nicotinamide is postulated to enhance DNA repair and reverse UV immunosuppression in NMSC patients and is a well-tolerated and inexpensive supplement (approximately $10 a month for the dosage in this study). Although the decrease in skin cancer number per year seems modest in this study, my patients would likely welcome at least 1 fewer surgery per year and much less cryotherapy or 5-fluorouracil cream, especially if it is as simple as buying the supplement at the grocery store as they do for their fish oil capsules and probiotics. Does vitamin B3 hold promise for your high-risk NMSC patients?

At the recent American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Martin et al presented data from the Australian Oral Nicotinamide to Reduce Actinic Cancer (ONTRAC) study. This prospective double-blind, randomized, controlled trial examined 386 immunocompetent patients with 2 or more nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) in the last 5 years (average, 8). The patients were randomized to receive oral nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily or placebo for 1 year, resulting in significant reduction of new NMSCs (average rate 1.77 vs 2.42; relative rate reduction, 23%; P=.02), with similar results for basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Actinic keratosis counts were reduced throughout the year by up to 20%, peaking at 9 months. No differences in adverse events were noted between the treatment and placebo groups.

What’s the issue?

High-risk NMSC patients present a challenge to dermatologists, as their need for constant surveillance, field therapy for actinic keratoses, and revolving visits between skin examinations and procedural modalities such as Mohs micrographic surgery can be staggering. Chemopreventive strategies pose difficulties, especially for elderly patients, due to tolerability and adherence, skin irritation and cosmetic limitations of topical therapies such as 5-fluorouracil, and inadequacy or financial inaccessibility of oral therapies such as acitretin.

Nicotinamide is a confusing supplement, as it is also called niacinamide. One of the 2 forms of vitamin B3, nicotinic acid (or niacin) is the other form and can be converted to nicotinamide in the body. It has cholesterol and vasodilatory/flushing effects that nicotinamide itself does not. Therefore, these supplement subtypes are not generally interchangeable.

Nicotinamide is postulated to enhance DNA repair and reverse UV immunosuppression in NMSC patients and is a well-tolerated and inexpensive supplement (approximately $10 a month for the dosage in this study). Although the decrease in skin cancer number per year seems modest in this study, my patients would likely welcome at least 1 fewer surgery per year and much less cryotherapy or 5-fluorouracil cream, especially if it is as simple as buying the supplement at the grocery store as they do for their fish oil capsules and probiotics. Does vitamin B3 hold promise for your high-risk NMSC patients?

At the recent American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Martin et al presented data from the Australian Oral Nicotinamide to Reduce Actinic Cancer (ONTRAC) study. This prospective double-blind, randomized, controlled trial examined 386 immunocompetent patients with 2 or more nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) in the last 5 years (average, 8). The patients were randomized to receive oral nicotinamide 500 mg twice daily or placebo for 1 year, resulting in significant reduction of new NMSCs (average rate 1.77 vs 2.42; relative rate reduction, 23%; P=.02), with similar results for basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Actinic keratosis counts were reduced throughout the year by up to 20%, peaking at 9 months. No differences in adverse events were noted between the treatment and placebo groups.

What’s the issue?

High-risk NMSC patients present a challenge to dermatologists, as their need for constant surveillance, field therapy for actinic keratoses, and revolving visits between skin examinations and procedural modalities such as Mohs micrographic surgery can be staggering. Chemopreventive strategies pose difficulties, especially for elderly patients, due to tolerability and adherence, skin irritation and cosmetic limitations of topical therapies such as 5-fluorouracil, and inadequacy or financial inaccessibility of oral therapies such as acitretin.

Nicotinamide is a confusing supplement, as it is also called niacinamide. One of the 2 forms of vitamin B3, nicotinic acid (or niacin) is the other form and can be converted to nicotinamide in the body. It has cholesterol and vasodilatory/flushing effects that nicotinamide itself does not. Therefore, these supplement subtypes are not generally interchangeable.

Nicotinamide is postulated to enhance DNA repair and reverse UV immunosuppression in NMSC patients and is a well-tolerated and inexpensive supplement (approximately $10 a month for the dosage in this study). Although the decrease in skin cancer number per year seems modest in this study, my patients would likely welcome at least 1 fewer surgery per year and much less cryotherapy or 5-fluorouracil cream, especially if it is as simple as buying the supplement at the grocery store as they do for their fish oil capsules and probiotics. Does vitamin B3 hold promise for your high-risk NMSC patients?

Heroin use up across demographic groups from 2002 to 2013

Heroin use is rising across all demographic groups in the United States, and is gaining traction among groups that previously have been associated with lower use, doubling among women and more than doubling among non-Hispanic whites, Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in a July 7 telebriefing.

Between 2002 and 2013, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled, and more than 8,200 people died in 2013, according to the latest Vital Signs report, a combined project from the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration that analyzed data from the 2002-2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

In addition, the gaps between men and women, low and higher incomes, and people with Medicaid and private insurance have narrowed in the past decade, although the most at-risk groups are still non-Hispanic whites, men, 18- to 25-year-olds, people with an annual household incomes of less than $20,000, Medicaid recipients, and the uninsured.

Although people who are addicted to prescription opioid painkillers were 40 times more likely to abuse heroin, the general idea that people gravitating to heroin abuse are doing so because opiates have become harder to get is not true, Dr. Frieden noted. The study identified two factors that were likely responsible for the increase in heroin users – the combination of the increased supply of heroin and higher demand, as well as the number of people already addicted to opioids who are “primed” for a heroin addiction.

However, state agencies have a central role to play in curbing heroin abuse, and will need to increase support for drug monitoring and surveillance programs to make tracking opiate abusers easier and more efficient, Dr. Frieden said.

The CDC is addressing the epidemic by helping to create federal guidelines for pain management, and supporting research and development for less addictive pain medications, he said.

“Improving prescribing practices is part of the solution, not part of the cause,” Dr. Frieden said.

Individual health care providers can help by following best practices for responsible painkiller prescribing to reduce opioid painkiller addiction, and by providing training for ways to adequately and comprehensively address pain beyond simply prescribing painkillers.

“Opiates are very good at curbing severe pain ... But for chronic, noncancer pain, you really need to look at the risks and benefits,” said Christopher M. Jones, Pharm.D., the study’s coauthor and a senior adviser at the FDA.

Heroin use is rising across all demographic groups in the United States, and is gaining traction among groups that previously have been associated with lower use, doubling among women and more than doubling among non-Hispanic whites, Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in a July 7 telebriefing.

Between 2002 and 2013, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled, and more than 8,200 people died in 2013, according to the latest Vital Signs report, a combined project from the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration that analyzed data from the 2002-2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

In addition, the gaps between men and women, low and higher incomes, and people with Medicaid and private insurance have narrowed in the past decade, although the most at-risk groups are still non-Hispanic whites, men, 18- to 25-year-olds, people with an annual household incomes of less than $20,000, Medicaid recipients, and the uninsured.

Although people who are addicted to prescription opioid painkillers were 40 times more likely to abuse heroin, the general idea that people gravitating to heroin abuse are doing so because opiates have become harder to get is not true, Dr. Frieden noted. The study identified two factors that were likely responsible for the increase in heroin users – the combination of the increased supply of heroin and higher demand, as well as the number of people already addicted to opioids who are “primed” for a heroin addiction.

However, state agencies have a central role to play in curbing heroin abuse, and will need to increase support for drug monitoring and surveillance programs to make tracking opiate abusers easier and more efficient, Dr. Frieden said.

The CDC is addressing the epidemic by helping to create federal guidelines for pain management, and supporting research and development for less addictive pain medications, he said.

“Improving prescribing practices is part of the solution, not part of the cause,” Dr. Frieden said.

Individual health care providers can help by following best practices for responsible painkiller prescribing to reduce opioid painkiller addiction, and by providing training for ways to adequately and comprehensively address pain beyond simply prescribing painkillers.

“Opiates are very good at curbing severe pain ... But for chronic, noncancer pain, you really need to look at the risks and benefits,” said Christopher M. Jones, Pharm.D., the study’s coauthor and a senior adviser at the FDA.

Heroin use is rising across all demographic groups in the United States, and is gaining traction among groups that previously have been associated with lower use, doubling among women and more than doubling among non-Hispanic whites, Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in a July 7 telebriefing.

Between 2002 and 2013, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths nearly quadrupled, and more than 8,200 people died in 2013, according to the latest Vital Signs report, a combined project from the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration that analyzed data from the 2002-2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

In addition, the gaps between men and women, low and higher incomes, and people with Medicaid and private insurance have narrowed in the past decade, although the most at-risk groups are still non-Hispanic whites, men, 18- to 25-year-olds, people with an annual household incomes of less than $20,000, Medicaid recipients, and the uninsured.

Although people who are addicted to prescription opioid painkillers were 40 times more likely to abuse heroin, the general idea that people gravitating to heroin abuse are doing so because opiates have become harder to get is not true, Dr. Frieden noted. The study identified two factors that were likely responsible for the increase in heroin users – the combination of the increased supply of heroin and higher demand, as well as the number of people already addicted to opioids who are “primed” for a heroin addiction.

However, state agencies have a central role to play in curbing heroin abuse, and will need to increase support for drug monitoring and surveillance programs to make tracking opiate abusers easier and more efficient, Dr. Frieden said.

The CDC is addressing the epidemic by helping to create federal guidelines for pain management, and supporting research and development for less addictive pain medications, he said.

“Improving prescribing practices is part of the solution, not part of the cause,” Dr. Frieden said.

Individual health care providers can help by following best practices for responsible painkiller prescribing to reduce opioid painkiller addiction, and by providing training for ways to adequately and comprehensively address pain beyond simply prescribing painkillers.

“Opiates are very good at curbing severe pain ... But for chronic, noncancer pain, you really need to look at the risks and benefits,” said Christopher M. Jones, Pharm.D., the study’s coauthor and a senior adviser at the FDA.

FROM A CDC TELEBRIEFING

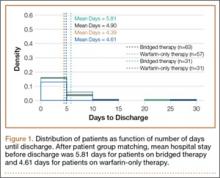

Extended warfarin delays return of unprovoked pulmonary embolism

Adding an extra 18 months of warfarin therapy to the standard 6 months of anticoagulation delays the recurrence of venous thrombosis in patients who have a first episode of unprovoked pulmonary embolism – but the risk of recurrence resumes as soon as the warfarin is discontinued, according to a report published online July 7 in JAMA.

“Our results suggest that patients such as those who participated in our study require long-term secondary prophylaxis measures. Whether these should include systematic treatment with vitamin K antagonists, new anticoagulants, or aspirin, or be tailored according to patient risk factors (including elevated D-dimer levels) needs further investigation,” said Dr. Francis Couturaud of the department of internal medicine and chest diseases, University of Brest (France) Hospital, and his associates (JAMA 2015;314:31-40).

Adults with a first episode of unprovoked VT are at much greater risk of recurrence when the standard 6 months of anticoagulation runs out, compared with those whose VT is provoked by a known, transient risk factor such as lengthy surgery, trauma with immobilization of the lower limbs, or bed rest extending longer than 72 hours.

Some experts have advocated extending anticoagulation further in such patients; but whether this is actually beneficial remains uncertain, the investigators said, because most studies have not pursued follow-up beyond the end of treatment.

The researchers performed a multicenter, double-blind trial in which 371 consecutive patients with a first episode of unprovoked PE completed 6 months of anticoagulation and then were randomly assigned to a further 18 months on either warfarin or matching placebo.

During this 18-month treatment period, the primary outcome – a composite of recurrent VT (including PE) and major bleeding – occurred in 3.3% of the warfarin group and 13.5% of the placebo group. That significant difference translated to a 78% reduction in favor of warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.22), Dr. Couturaud and his associates said.

However, after the treatment period ended, the composite outcome occurred in 17.7% of the warfarin group and 10.3% of the placebo group. Thus, the risk of recurrence returned to its normal high level once warfarin was discontinued, the study authors noted.

The study was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (the French Department of Health) and the University Hospital of Brest (France). Dr. Couturaud reported receiving research grants, honoraria, and travel pay from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Intermune, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Related Information

- Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) may be useful in the diagnosis of suspected PE, wrote Dr. Gregoire Le Gal and co-authors from the University of Ottawa. Alternately, a V/Q scan may be performed. The complete accompanying article on diagnostic testing methods for suspected pulmonary embolism can be found here.

- The recently approved anticoagulant edoxaban is similar to warfarin in its ability to treat acute VTE, according to a report published in the Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics in the same issue. However, further study is needed to evaluate its safety and efficacy compared with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, the three other oral anticoagulant drugs currently FDA-approved for acute VTE.

- A meta-analysis of 3,716 patients with VTE found that long-term treatment with Vitamin K antagonists was associated with lower rates of thromboembolic events (relative risk = 0.20) and higher rates of bleeding complications (RR = 3.44), compared with short-term therapy, Dr. Saskia Middeldorp and Dr. Barbara A. Hutten of the University of Amsterdam reported in the same issue. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

- Currently, recommended treatment duration for PE can range from three months to lifelong treatment, wrote Dr. Jill Jin in a clinical synopsis for patients published with the study.

- Read the full article and listen to the related podcast: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2015.7046

Madhu Rajaraman contributed to this report.

Adding an extra 18 months of warfarin therapy to the standard 6 months of anticoagulation delays the recurrence of venous thrombosis in patients who have a first episode of unprovoked pulmonary embolism – but the risk of recurrence resumes as soon as the warfarin is discontinued, according to a report published online July 7 in JAMA.

“Our results suggest that patients such as those who participated in our study require long-term secondary prophylaxis measures. Whether these should include systematic treatment with vitamin K antagonists, new anticoagulants, or aspirin, or be tailored according to patient risk factors (including elevated D-dimer levels) needs further investigation,” said Dr. Francis Couturaud of the department of internal medicine and chest diseases, University of Brest (France) Hospital, and his associates (JAMA 2015;314:31-40).

Adults with a first episode of unprovoked VT are at much greater risk of recurrence when the standard 6 months of anticoagulation runs out, compared with those whose VT is provoked by a known, transient risk factor such as lengthy surgery, trauma with immobilization of the lower limbs, or bed rest extending longer than 72 hours.

Some experts have advocated extending anticoagulation further in such patients; but whether this is actually beneficial remains uncertain, the investigators said, because most studies have not pursued follow-up beyond the end of treatment.

The researchers performed a multicenter, double-blind trial in which 371 consecutive patients with a first episode of unprovoked PE completed 6 months of anticoagulation and then were randomly assigned to a further 18 months on either warfarin or matching placebo.

During this 18-month treatment period, the primary outcome – a composite of recurrent VT (including PE) and major bleeding – occurred in 3.3% of the warfarin group and 13.5% of the placebo group. That significant difference translated to a 78% reduction in favor of warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.22), Dr. Couturaud and his associates said.

However, after the treatment period ended, the composite outcome occurred in 17.7% of the warfarin group and 10.3% of the placebo group. Thus, the risk of recurrence returned to its normal high level once warfarin was discontinued, the study authors noted.

The study was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (the French Department of Health) and the University Hospital of Brest (France). Dr. Couturaud reported receiving research grants, honoraria, and travel pay from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Intermune, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Related Information

- Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) may be useful in the diagnosis of suspected PE, wrote Dr. Gregoire Le Gal and co-authors from the University of Ottawa. Alternately, a V/Q scan may be performed. The complete accompanying article on diagnostic testing methods for suspected pulmonary embolism can be found here.

- The recently approved anticoagulant edoxaban is similar to warfarin in its ability to treat acute VTE, according to a report published in the Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics in the same issue. However, further study is needed to evaluate its safety and efficacy compared with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, the three other oral anticoagulant drugs currently FDA-approved for acute VTE.

- A meta-analysis of 3,716 patients with VTE found that long-term treatment with Vitamin K antagonists was associated with lower rates of thromboembolic events (relative risk = 0.20) and higher rates of bleeding complications (RR = 3.44), compared with short-term therapy, Dr. Saskia Middeldorp and Dr. Barbara A. Hutten of the University of Amsterdam reported in the same issue. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

- Currently, recommended treatment duration for PE can range from three months to lifelong treatment, wrote Dr. Jill Jin in a clinical synopsis for patients published with the study.

- Read the full article and listen to the related podcast: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2015.7046

Madhu Rajaraman contributed to this report.

Adding an extra 18 months of warfarin therapy to the standard 6 months of anticoagulation delays the recurrence of venous thrombosis in patients who have a first episode of unprovoked pulmonary embolism – but the risk of recurrence resumes as soon as the warfarin is discontinued, according to a report published online July 7 in JAMA.

“Our results suggest that patients such as those who participated in our study require long-term secondary prophylaxis measures. Whether these should include systematic treatment with vitamin K antagonists, new anticoagulants, or aspirin, or be tailored according to patient risk factors (including elevated D-dimer levels) needs further investigation,” said Dr. Francis Couturaud of the department of internal medicine and chest diseases, University of Brest (France) Hospital, and his associates (JAMA 2015;314:31-40).

Adults with a first episode of unprovoked VT are at much greater risk of recurrence when the standard 6 months of anticoagulation runs out, compared with those whose VT is provoked by a known, transient risk factor such as lengthy surgery, trauma with immobilization of the lower limbs, or bed rest extending longer than 72 hours.

Some experts have advocated extending anticoagulation further in such patients; but whether this is actually beneficial remains uncertain, the investigators said, because most studies have not pursued follow-up beyond the end of treatment.

The researchers performed a multicenter, double-blind trial in which 371 consecutive patients with a first episode of unprovoked PE completed 6 months of anticoagulation and then were randomly assigned to a further 18 months on either warfarin or matching placebo.

During this 18-month treatment period, the primary outcome – a composite of recurrent VT (including PE) and major bleeding – occurred in 3.3% of the warfarin group and 13.5% of the placebo group. That significant difference translated to a 78% reduction in favor of warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.22), Dr. Couturaud and his associates said.

However, after the treatment period ended, the composite outcome occurred in 17.7% of the warfarin group and 10.3% of the placebo group. Thus, the risk of recurrence returned to its normal high level once warfarin was discontinued, the study authors noted.

The study was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (the French Department of Health) and the University Hospital of Brest (France). Dr. Couturaud reported receiving research grants, honoraria, and travel pay from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Intermune, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Related Information

- Computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) may be useful in the diagnosis of suspected PE, wrote Dr. Gregoire Le Gal and co-authors from the University of Ottawa. Alternately, a V/Q scan may be performed. The complete accompanying article on diagnostic testing methods for suspected pulmonary embolism can be found here.

- The recently approved anticoagulant edoxaban is similar to warfarin in its ability to treat acute VTE, according to a report published in the Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics in the same issue. However, further study is needed to evaluate its safety and efficacy compared with dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban, the three other oral anticoagulant drugs currently FDA-approved for acute VTE.

- A meta-analysis of 3,716 patients with VTE found that long-term treatment with Vitamin K antagonists was associated with lower rates of thromboembolic events (relative risk = 0.20) and higher rates of bleeding complications (RR = 3.44), compared with short-term therapy, Dr. Saskia Middeldorp and Dr. Barbara A. Hutten of the University of Amsterdam reported in the same issue. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

- Currently, recommended treatment duration for PE can range from three months to lifelong treatment, wrote Dr. Jill Jin in a clinical synopsis for patients published with the study.

- Read the full article and listen to the related podcast: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2015.7046

Madhu Rajaraman contributed to this report.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Eighteen additional months of warfarin therapy delays the recurrence of unprovoked pulmonary embolism.

Major finding: During treatment, the primary outcome – a composite of recurrent venous thromboembolism and major bleeding – occurred in 3.3% of the warfarin group and 13.5% of the placebo group, a significant difference that translated to a 78% reduction in favor of warfarin (hazard ratio, 0.22).

Data source: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial involving 371 patients followed for a mean of 41 months.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (the French Department of Health) and the University Hospital of Brest (France). Dr. Couturaud reported receiving research grants, honoraria, and travel pay from Actelion, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, Intermune, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer, and his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Madelung Deformity and Extensor Tendon Rupture

Extensor tendon rupture in chronic Madelung deformity, as a result of tendon attrition on the dislocated distal ulna, occurs infrequently. However, it is often seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This issue has been reported in only a few English-language case reports. Here we report a case of multiple tendon ruptures in a previously undiagnosed Madelung deformity. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 56-year-old active woman presented with 50 days’ inability to extend the fourth and fifth fingers of her dominant right hand. The loss of finger extension progressed, over several weeks, to involve the third finger as well. The first 2 tendon ruptures had been triggered by lifting a light grocery bag, when she noticed a sharp sudden pain and “pop.” The third rupture occurred spontaneously with a snapping sound the night before surgery.

The patient had observed some prominence on the ulnar side of her right wrist since childhood but had never experienced any pain or functional disability. There was neither history of trauma, inflammatory disease, diabetes mellitus, or infection, nor positive family history of similar wrist deformity.

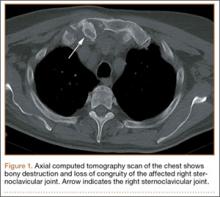

The physical examination showed a dorsally subluxated distal radioulnar joint, prominent ulnar styloid, and mild ulnar and volar deviation of the wrist along with limitation of wrist dorsiflexion. Complete loss of active extension of the 3 ulnar fingers was demonstrated, while neurovascular status and all other hand evaluations were normal. The wrist radiographs confirmed the typical findings of Madelung deformity (Figure 1).

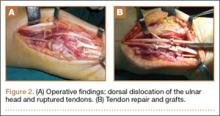

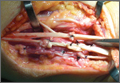

Repair of the ruptured tendons and resection of the prominent distal ulna (Darrach procedure) was planned. (Given the patient’s age and evidence of degenerative changes in the radiocarpal joint, correction of the Madelung deformity did not seem necessary). At time of surgery, the recently ruptured third finger extensor tendon was easily found and approximated, and end-to-end repair was performed. The fourth and fifth fingers, however, had to be fished out more proximally from dense granulation tissue. After the distal ulna was resected for a distance of 1.5 cm, meticulous repair of the ulnar collateral ligament and the capsule and periosteum over the end of the ulna was performed. Then, for grafting of the ruptured tendons, the extensor indicis proprius tendon was isolated and transected at the second metacarpophalangeal joint level. A piece of this tendon was used as interpositional graft for the fourth extensor tendon, and the main tendon unit was transferred to the fifth finger extensor. The extensor digiti quinti tendon, which was about to rupture, was further reinforced by suturing it side to side to the muscle and tendon of the extensor indicis proprius (Figure 2).

Postoperatively, the wrist was kept in extension in a cast for 3 weeks while the fingers were free for active movement. A removable wrist splint was used for an additional month. At 3-month follow-up, the patient had regained full and strong finger extension and wrist motion.

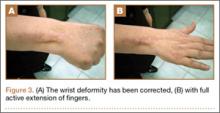

At 3-year follow-up, the patient was pain-free, and had full extension of all fingers, full forearm rotation, and near-normal motion (better than her preoperative motion). The grip power on the operated right hand was 215 N, and pinch power was 93 N. (The values for the left side were 254 N and 83 N, respectively, using the Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer [Patterson Medical].) The patient has had no additional tendon rupture (Figure 3).

Discussion

Madelung deformity was first described by Madelung in 1878 and several cases have reported this deformity. However, extensor tendon rupture caused by Madelung deformity is very rare, reported in few cases.1

Extensor tendon rupture caused by chronic Madelung deformity has been reported few times in the English literature. Goodwin1 apparently published the first report of such an occurrence in 1979. Ducloyer and colleagues2 from France reported 6 cases of extensor tendon rupture as a result of inferior distal radioulnar joint deformity of Madelung. Jebson and colleagues3 reported bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung deformity in 1992.

The mechanism of tendon rupture seems to be mechanical, resulting from continuous rubbing and erosion of tendons over the deformed ulnar head, which has a rough irregular surface4 and leads to fraying of the tendons and eventual rupture and retraction of the severed tendon ends. This rupture usually progresses stepwise from more medial to the lateral tendons.2 Older patients are, therefore, subject to chronic repetitive attritional trauma leading to tendon rupture.

Tendons may rupture as a result of a variety of conditions, such as chronic synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, or crystal deposition in gout.5-8 Some other metabolic or endocrine conditions that involve tendon ruptures include diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, and hyperparathyroidism. Steroid injection into the tendons also has a detrimental effect on tendon integrity and may cause tendon tear.9 Mechanical factors, such as erosion on bony prominences, are well-known etiologies for tendon rupture, as commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis, and have been reported in Kienböck disease,10 thumb carpometacarpal arthritis,11 Colles fracture, scaphoid fracture nonunion,12 and Madelung deformity.

Conclusion

Our case reflects the usual middle-aged female presentation of such a tendon rupture. The tendon ruptures were spontaneous in the reported order of ulnar to radial, beginning with the little and ring fingers, and progressed radially. The patient had isolated Madelung deformity with no other sign of dyschondrosteosis13 or dwarfism, conditions commonly mentioned in association with Madelung deformity. This case report should raise awareness about possible tendon rupture in any chronic case of Madelung deformity.

1. Goodwin DR, Michels CH, Weissman SL. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons in Madelung’s deformity. Hand. 1979;11(1):72-75.

2. Ducloyer P, Leclercq C, Lisfrance R, Saffar P. Spontaneous rupture of the extensor tendons of the fingers in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16(3):329-333.

3. Jebson PJ, Blair WF. Bilateral spontaneous extensor tendon ruptures in Madelung’s deformity. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(2):277-280.

4. Schulstad I. Madelung’s deformity with extensor tendon rupture. Case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1971;5(2):153-155.

5. Gong HS, Lee JO, Baek GH, et al. Extensor tendon rupture in rheumatoid arthritis: a survey of patients between 2005 and 2010 at five Korean hospitals. Hand Surg. 2012;17(1):43-47.

6. Oishi H, Oda R, Morisaki S, Fujiwara H, Tokunaga D, Kubo T. Spontaneous tendon rupture of the extensor digitrum communis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mod Rheumatol. 2013;23(3);608-610.

7. Kobayashi A, Futami T, Tadano I, Fujita M. Spontaneous rupture of extensor tendons at the wrist in a patient with mixed connective tissue disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2002;12(3):256-258.

8. Iwamoto T, Toki H, Ikari K, Yamanaka H, Momohara S. Multiple extensor tendon ruptures caused by tophaceous gout. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(2):210-212.

9. Nquyen ML, Jones NF. Rupture of both abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendon after steroid injection for de quervain tenosynovitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(5):883e-886e.

10. Hernández-Cortés P, Pajares-López M, Gómez-Sánchez R, Garrido-Gómez, Lara-Garcia F. Rupture of extensor tendon secondary to previously undiagnosed Kienböck disease. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2012;46(3-4):291-293.

11. Apard T, Marcucci L, Jarriges J. Spontaneous rupture of extensor pollicis longus in isolated trapeziometacarpal arthritis. Chir Main. 2011;30(5):349-351.