User login

Theorem helps pinpoint start of patient recovery

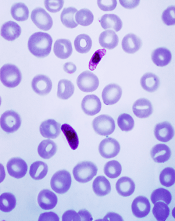

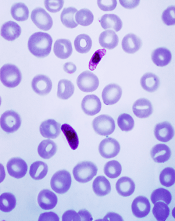

Credit: CDC

The 2500-year-old Pythagorean theorem could be the most effective way to identify the point at which a patient’s health begins to improve, a new study suggests.

Researchers made the discovery while examining receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, which are used to measure changes in a patient’s health status.

“It all comes down to choosing a point on a curve to determine when recovery has occurred,” said study author Rob Froud, PhD, of the University of Warwick in Coventry, UK.

“For many chronic conditions, epidemiologists agree that the correct point to choose is that which is closest to the top-left corner of the plot containing the curve. As we stopped to think about it, it struck us as obvious that the way to choose this point was by using Pythagoras’s theorem.”

The theorem states that, in a right-angled triangle, the sum of the squares of the 2 right-angled sides is equal to the square of the hypotenuse (the longer diagonal that joins the 2 right-angled sides).

With this formula (a2+b2=c2), a person can determine the length of the hypotenuse when given the length of the other 2 sides.

“We set about exploring the implications of this and how it might change conclusions in research,” Dr Froud said. “We conducted several experiments using real trial data, and it seems using Pythagoras’s theorem makes a material difference.”

“It helps to identify the point at which a patient has improved with more consistency and accuracy than other methods commonly used. The moral of the story is that, before you throw out the old stuff in the attic, just go through it one last time, as there may be something in there that is still relevant and useful.”

Dr Froud and his colleague Gary Abel, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK, described this research in PLOS ONE. ![]()

Credit: CDC

The 2500-year-old Pythagorean theorem could be the most effective way to identify the point at which a patient’s health begins to improve, a new study suggests.

Researchers made the discovery while examining receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, which are used to measure changes in a patient’s health status.

“It all comes down to choosing a point on a curve to determine when recovery has occurred,” said study author Rob Froud, PhD, of the University of Warwick in Coventry, UK.

“For many chronic conditions, epidemiologists agree that the correct point to choose is that which is closest to the top-left corner of the plot containing the curve. As we stopped to think about it, it struck us as obvious that the way to choose this point was by using Pythagoras’s theorem.”

The theorem states that, in a right-angled triangle, the sum of the squares of the 2 right-angled sides is equal to the square of the hypotenuse (the longer diagonal that joins the 2 right-angled sides).

With this formula (a2+b2=c2), a person can determine the length of the hypotenuse when given the length of the other 2 sides.

“We set about exploring the implications of this and how it might change conclusions in research,” Dr Froud said. “We conducted several experiments using real trial data, and it seems using Pythagoras’s theorem makes a material difference.”

“It helps to identify the point at which a patient has improved with more consistency and accuracy than other methods commonly used. The moral of the story is that, before you throw out the old stuff in the attic, just go through it one last time, as there may be something in there that is still relevant and useful.”

Dr Froud and his colleague Gary Abel, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK, described this research in PLOS ONE. ![]()

Credit: CDC

The 2500-year-old Pythagorean theorem could be the most effective way to identify the point at which a patient’s health begins to improve, a new study suggests.

Researchers made the discovery while examining receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, which are used to measure changes in a patient’s health status.

“It all comes down to choosing a point on a curve to determine when recovery has occurred,” said study author Rob Froud, PhD, of the University of Warwick in Coventry, UK.

“For many chronic conditions, epidemiologists agree that the correct point to choose is that which is closest to the top-left corner of the plot containing the curve. As we stopped to think about it, it struck us as obvious that the way to choose this point was by using Pythagoras’s theorem.”

The theorem states that, in a right-angled triangle, the sum of the squares of the 2 right-angled sides is equal to the square of the hypotenuse (the longer diagonal that joins the 2 right-angled sides).

With this formula (a2+b2=c2), a person can determine the length of the hypotenuse when given the length of the other 2 sides.

“We set about exploring the implications of this and how it might change conclusions in research,” Dr Froud said. “We conducted several experiments using real trial data, and it seems using Pythagoras’s theorem makes a material difference.”

“It helps to identify the point at which a patient has improved with more consistency and accuracy than other methods commonly used. The moral of the story is that, before you throw out the old stuff in the attic, just go through it one last time, as there may be something in there that is still relevant and useful.”

Dr Froud and his colleague Gary Abel, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK, described this research in PLOS ONE. ![]()

A renowned device innovator honored

In November last year, one of the highly prestigious National Medals of Technology and Innovation was presented to Thomas J. Fogarty, Fogarty Institute for Innovation, for his innovations in minimally invasive medical devices. U.S. President Obama presided at the ceremony and presented the award.

Dr. Fogarty is chairman, director and founder of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation, and has served as a founder, chairman, or board member of over 30 business and research companies. During the past 40 years, he acquired 135 surgical patents, including the Fogarty balloon catheter and the Aneurx Stent Graft, an endovascular device that replaces open surgery for aortic aneurysm.

Along with the recently awarded National Medal of Technology and Innovation, he has received the Jacobson Innovation Award of the American College of Surgeons and the 2000 Lemelson-MIT prize for Invention and Innovation. He was inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame in 2001.

Surgeon who saved Pope’s life thanked

Dr. Juan Carlos Parodi today is a prominent figure in the world vascular community, one famous for his work in the development of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) several decades ago.

But it was an emergency gall bladder operation many years ago, which he performed in his native Argentina, that caused him to rise to a unique prominence, illustrated in a more recent visit to Vatican City, where he had a 40-minute private audience with Pope Francis.

Dr. Parodi explained: “In 1980 I was called to treat a poor priest with a gangrenous cholecystitis caused by Clostridium. I took care of him without charging him, and after days of dialysis he survived. I forgot the experience until one day I received a call telling me that the poor priest I took care of became the Pope Francis. He invited me to visit him in the Vatican, and I went to visit him last year.

“Pope Francis received me saying: Welcome the surgeon who saved my life coming in the middle of the night to do an operation without asking for any compensation! I told him that as a physician we help people who need us, regardless of the lack of payment capacity. I was honored by being invited by him,” Dr. Parodi added.

Currently, Dr. Parodi is a professor of surgery at the University of Buenos Aires, and chief of vascular surgery at the Sanatorio Trinidad, Buenos Aires.

In November last year, one of the highly prestigious National Medals of Technology and Innovation was presented to Thomas J. Fogarty, Fogarty Institute for Innovation, for his innovations in minimally invasive medical devices. U.S. President Obama presided at the ceremony and presented the award.

Dr. Fogarty is chairman, director and founder of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation, and has served as a founder, chairman, or board member of over 30 business and research companies. During the past 40 years, he acquired 135 surgical patents, including the Fogarty balloon catheter and the Aneurx Stent Graft, an endovascular device that replaces open surgery for aortic aneurysm.

Along with the recently awarded National Medal of Technology and Innovation, he has received the Jacobson Innovation Award of the American College of Surgeons and the 2000 Lemelson-MIT prize for Invention and Innovation. He was inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame in 2001.

Surgeon who saved Pope’s life thanked

Dr. Juan Carlos Parodi today is a prominent figure in the world vascular community, one famous for his work in the development of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) several decades ago.

But it was an emergency gall bladder operation many years ago, which he performed in his native Argentina, that caused him to rise to a unique prominence, illustrated in a more recent visit to Vatican City, where he had a 40-minute private audience with Pope Francis.

Dr. Parodi explained: “In 1980 I was called to treat a poor priest with a gangrenous cholecystitis caused by Clostridium. I took care of him without charging him, and after days of dialysis he survived. I forgot the experience until one day I received a call telling me that the poor priest I took care of became the Pope Francis. He invited me to visit him in the Vatican, and I went to visit him last year.

“Pope Francis received me saying: Welcome the surgeon who saved my life coming in the middle of the night to do an operation without asking for any compensation! I told him that as a physician we help people who need us, regardless of the lack of payment capacity. I was honored by being invited by him,” Dr. Parodi added.

Currently, Dr. Parodi is a professor of surgery at the University of Buenos Aires, and chief of vascular surgery at the Sanatorio Trinidad, Buenos Aires.

In November last year, one of the highly prestigious National Medals of Technology and Innovation was presented to Thomas J. Fogarty, Fogarty Institute for Innovation, for his innovations in minimally invasive medical devices. U.S. President Obama presided at the ceremony and presented the award.

Dr. Fogarty is chairman, director and founder of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation, and has served as a founder, chairman, or board member of over 30 business and research companies. During the past 40 years, he acquired 135 surgical patents, including the Fogarty balloon catheter and the Aneurx Stent Graft, an endovascular device that replaces open surgery for aortic aneurysm.

Along with the recently awarded National Medal of Technology and Innovation, he has received the Jacobson Innovation Award of the American College of Surgeons and the 2000 Lemelson-MIT prize for Invention and Innovation. He was inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame in 2001.

Surgeon who saved Pope’s life thanked

Dr. Juan Carlos Parodi today is a prominent figure in the world vascular community, one famous for his work in the development of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) several decades ago.

But it was an emergency gall bladder operation many years ago, which he performed in his native Argentina, that caused him to rise to a unique prominence, illustrated in a more recent visit to Vatican City, where he had a 40-minute private audience with Pope Francis.

Dr. Parodi explained: “In 1980 I was called to treat a poor priest with a gangrenous cholecystitis caused by Clostridium. I took care of him without charging him, and after days of dialysis he survived. I forgot the experience until one day I received a call telling me that the poor priest I took care of became the Pope Francis. He invited me to visit him in the Vatican, and I went to visit him last year.

“Pope Francis received me saying: Welcome the surgeon who saved my life coming in the middle of the night to do an operation without asking for any compensation! I told him that as a physician we help people who need us, regardless of the lack of payment capacity. I was honored by being invited by him,” Dr. Parodi added.

Currently, Dr. Parodi is a professor of surgery at the University of Buenos Aires, and chief of vascular surgery at the Sanatorio Trinidad, Buenos Aires.

Tips on tics

As an experienced clinician who has seen tics and habits in your patients come and go, you may be surprised by the amount of concern parents express about them. At times, it seems, and may be, that the parent’s attention to the habit actually keeps it going! This does not always mean that the child keeps doing the habit to aggravate the parent, as parental correction may amp up the child’s anxiety, which may make the habit worse.

As with other parent concerns, both empathizing with their worry and providing evidence-based information is helpful in relieving their distress.

Habits are complex behaviors done the same way repeatedly. Habits can have a strong protective effect on our lives and be a foundation for success when they ensure that we wash our hands (protection from infection), help us know where the keys are (efficiency), or soothe us to sleep (bedtime routines).

Tics are “involuntary” (meaning often, but not always, suppressible), brief, abrupt, repeated movements usually of the face, head, or neck. More complex, apparently meaningless movements may fall into the category of stereotypies. If they last more than 4 weeks, are driven, and cause marked dysfunction or significant self-injury, they may even qualify as stereotypic movement disorder.

It is good to know that repeated behaviors such as thumb sucking, nail/lip biting, hair twirling, body rocking, self biting, and head banging are relatively common in childhood, and often (but not mostly) disappear after age 4. I like to set the expectation that one habit or tic often evolves to another to reduce panic when this happens. Thumb and hand sucking at a younger developmental age may be replaced by body rocking and head banging, and later by nail biting and finger and foot tapping.

Even in college, habits are common and stress-related such as touching the face; playing with hair, pens, or jewelry; shaking a leg; tapping fingers; or scratching the head. Parents may connect some of these to acne or poor hygiene (a good opening for coaching!) but more importantly they may be accompanied by general distress, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and impulsive aggressive symptoms, which need to be looked for and addressed.

Stereotypies occur in about 20% of typically developing children (called “primary”) and are classified into:

• Common behaviors (such as, rocking, head banging, finger drumming, pencil tapping, hair twisting),

• Head nodding.

• Complex motor movements (such as hand and arm flapping/waving).

Habits – including nail biting, lip chewing, and nose picking – also may be diagnosed as stereotypic movement disorders, although ICD-10 lists includes them as “other specified behavioral and emotional disorders.”

For both conditions, the behavior must not be better accounted for by a compulsion, a tic disorder, part of autism, hair pulling (trichotillomania), or paroxysmal dyskinesias.

So what is the difference between motor stereotypies and tics (and why do you care)? Motor stereotypies begin before 3 years in more than 60%, whereas tics appear later (mean 5-7 years). Stereotypies are more fixed in their pattern, compared with tics that keep shifting form, disappearing, and reappearing. Stereotypies frequently involve the arms, hands, or the entire body, while tics involve the eyes, face, head, and shoulders. Stereotypies are more fixed, rhythmic, and prolonged (most more than 10 seconds) than tics, which are mostly brief, rapid, random, and fluctuating.

One key distinguishing factor is that tics have a premonitory urge and result in a sense of relief after the tic is performed. This also means that they can be suppressed to some extent when the situation requires. While both may occur more during anxiety, excitement, or fatigue, stereotypic movements, unlike tics, also are common when the child is engrossed.

Tics can occur as a side effect of medications such as stimulants and may decrease by lowering the dose, but tics also come and go, so the impact of a medication can be hard to sort out.

One vocal or multiple motor tics occurring many times per day starting before age 18 years and lasting more than 1 year are considered chronic; those occurring less than 1 year are transient. Chronic multiple motor tics accompanied by vocalizations, even sniffing or throat clearing, qualify as Tourette syndrome. The feared component of Tourette of coprolalia (saying bad words or gestures) is fortunately rare. These diagnoses can only be made after ruling out the effects of medication or another neurological condition such as Sydenham’s chorea (resulting from infection via group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, the bacterium that causes rheumatic fever) or PANDAS (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections).

The importance of distinguishing tics from stereotypies is in the treatment options, differential diagnosis, and prognosis. Some families (and certainly the kids themselves) do not even notice that they are moving abnormally even though 25% have at least one family member with a similar behavior. But many parents are upset about the potential for teasing and stigmatization. When you ask them directly what they are afraid of, they often admit fearing an underlying diagnosis such as intellectual disability, autism, or Tourette syndrome. The first two are straightforward to rule in or out, but Tourette can be subtle. If parents don’t bring up the possibilities, it is worth telling them directly which underlying conditions can be ruled out.

There are many conditions comorbid with tics including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), learning disorder (LD), behavioral, developmental or social problems, and mood or anxiety disorders. This clearly means that a comprehensive evaluation looking specifically for these conditions is needed when a child has chronic tics. Typically developing children with complex arm or hand movements also are more likely to have ADHD (30%), LD (20%), obsessive-compulsive behaviors (10%), or tics (18%).

Tics and stereotypies may be annoying, but generally are not harmful or progressive, although repeated movements such as skin or nose picking may result in scars or infections, and severe head banging can lead to eye injuries. Frequently repeated motor acts can cause significant muscle pain and fatigue. The most common problems are probably injury to self-esteem or oppositional behavior as a result of repeated (and fruitless) nagging or punishment by parents, even if well-meaning.

Since they occur so often along with comorbid conditions, our job includes determining the most problematic aspect before advising on a treatment. Both tics and stereotypies may be reduced by distraction, but the effect on stereotypies is faster and more certain. You can make this intervention in the office by simply asking how the child can tell when they make the movement and have them plan out what they could do instead. An example might be to shift a hand flapping movement (that makes peers think of autism) into more acceptable fist clenching. Habit reversal training or differential reinforcement based on a functional analysis can be taught by psychologists when this simple suggestion is not effective. When tics are severe, teacher education and school accommodations (504 Plan with extended time, scribe, private location for tic breaks) may be needed.

Medication is not indicated for most tics because most are mild. If ADHD is present, tics may actually be reduced by stimulants or atomoxetine rather than worsened. If the tic is severe and habit reversal training has not been successful, alpha agonists such as clonidine or guanfacine, or typical or atypical neuroleptics may be helpful. Even baclofen, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, nicotine, and Botox have been used. These require consultation with a specialist.

As for other chronic medical conditions, tics and persisting stereotypies deserve a comprehensive approach, including repeated education of the parent and child, evaluation for comorbidity, school accommodations, building other strengths and social support, and only rarely pulling out your prescription pad.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She has no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

As an experienced clinician who has seen tics and habits in your patients come and go, you may be surprised by the amount of concern parents express about them. At times, it seems, and may be, that the parent’s attention to the habit actually keeps it going! This does not always mean that the child keeps doing the habit to aggravate the parent, as parental correction may amp up the child’s anxiety, which may make the habit worse.

As with other parent concerns, both empathizing with their worry and providing evidence-based information is helpful in relieving their distress.

Habits are complex behaviors done the same way repeatedly. Habits can have a strong protective effect on our lives and be a foundation for success when they ensure that we wash our hands (protection from infection), help us know where the keys are (efficiency), or soothe us to sleep (bedtime routines).

Tics are “involuntary” (meaning often, but not always, suppressible), brief, abrupt, repeated movements usually of the face, head, or neck. More complex, apparently meaningless movements may fall into the category of stereotypies. If they last more than 4 weeks, are driven, and cause marked dysfunction or significant self-injury, they may even qualify as stereotypic movement disorder.

It is good to know that repeated behaviors such as thumb sucking, nail/lip biting, hair twirling, body rocking, self biting, and head banging are relatively common in childhood, and often (but not mostly) disappear after age 4. I like to set the expectation that one habit or tic often evolves to another to reduce panic when this happens. Thumb and hand sucking at a younger developmental age may be replaced by body rocking and head banging, and later by nail biting and finger and foot tapping.

Even in college, habits are common and stress-related such as touching the face; playing with hair, pens, or jewelry; shaking a leg; tapping fingers; or scratching the head. Parents may connect some of these to acne or poor hygiene (a good opening for coaching!) but more importantly they may be accompanied by general distress, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and impulsive aggressive symptoms, which need to be looked for and addressed.

Stereotypies occur in about 20% of typically developing children (called “primary”) and are classified into:

• Common behaviors (such as, rocking, head banging, finger drumming, pencil tapping, hair twisting),

• Head nodding.

• Complex motor movements (such as hand and arm flapping/waving).

Habits – including nail biting, lip chewing, and nose picking – also may be diagnosed as stereotypic movement disorders, although ICD-10 lists includes them as “other specified behavioral and emotional disorders.”

For both conditions, the behavior must not be better accounted for by a compulsion, a tic disorder, part of autism, hair pulling (trichotillomania), or paroxysmal dyskinesias.

So what is the difference between motor stereotypies and tics (and why do you care)? Motor stereotypies begin before 3 years in more than 60%, whereas tics appear later (mean 5-7 years). Stereotypies are more fixed in their pattern, compared with tics that keep shifting form, disappearing, and reappearing. Stereotypies frequently involve the arms, hands, or the entire body, while tics involve the eyes, face, head, and shoulders. Stereotypies are more fixed, rhythmic, and prolonged (most more than 10 seconds) than tics, which are mostly brief, rapid, random, and fluctuating.

One key distinguishing factor is that tics have a premonitory urge and result in a sense of relief after the tic is performed. This also means that they can be suppressed to some extent when the situation requires. While both may occur more during anxiety, excitement, or fatigue, stereotypic movements, unlike tics, also are common when the child is engrossed.

Tics can occur as a side effect of medications such as stimulants and may decrease by lowering the dose, but tics also come and go, so the impact of a medication can be hard to sort out.

One vocal or multiple motor tics occurring many times per day starting before age 18 years and lasting more than 1 year are considered chronic; those occurring less than 1 year are transient. Chronic multiple motor tics accompanied by vocalizations, even sniffing or throat clearing, qualify as Tourette syndrome. The feared component of Tourette of coprolalia (saying bad words or gestures) is fortunately rare. These diagnoses can only be made after ruling out the effects of medication or another neurological condition such as Sydenham’s chorea (resulting from infection via group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, the bacterium that causes rheumatic fever) or PANDAS (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections).

The importance of distinguishing tics from stereotypies is in the treatment options, differential diagnosis, and prognosis. Some families (and certainly the kids themselves) do not even notice that they are moving abnormally even though 25% have at least one family member with a similar behavior. But many parents are upset about the potential for teasing and stigmatization. When you ask them directly what they are afraid of, they often admit fearing an underlying diagnosis such as intellectual disability, autism, or Tourette syndrome. The first two are straightforward to rule in or out, but Tourette can be subtle. If parents don’t bring up the possibilities, it is worth telling them directly which underlying conditions can be ruled out.

There are many conditions comorbid with tics including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), learning disorder (LD), behavioral, developmental or social problems, and mood or anxiety disorders. This clearly means that a comprehensive evaluation looking specifically for these conditions is needed when a child has chronic tics. Typically developing children with complex arm or hand movements also are more likely to have ADHD (30%), LD (20%), obsessive-compulsive behaviors (10%), or tics (18%).

Tics and stereotypies may be annoying, but generally are not harmful or progressive, although repeated movements such as skin or nose picking may result in scars or infections, and severe head banging can lead to eye injuries. Frequently repeated motor acts can cause significant muscle pain and fatigue. The most common problems are probably injury to self-esteem or oppositional behavior as a result of repeated (and fruitless) nagging or punishment by parents, even if well-meaning.

Since they occur so often along with comorbid conditions, our job includes determining the most problematic aspect before advising on a treatment. Both tics and stereotypies may be reduced by distraction, but the effect on stereotypies is faster and more certain. You can make this intervention in the office by simply asking how the child can tell when they make the movement and have them plan out what they could do instead. An example might be to shift a hand flapping movement (that makes peers think of autism) into more acceptable fist clenching. Habit reversal training or differential reinforcement based on a functional analysis can be taught by psychologists when this simple suggestion is not effective. When tics are severe, teacher education and school accommodations (504 Plan with extended time, scribe, private location for tic breaks) may be needed.

Medication is not indicated for most tics because most are mild. If ADHD is present, tics may actually be reduced by stimulants or atomoxetine rather than worsened. If the tic is severe and habit reversal training has not been successful, alpha agonists such as clonidine or guanfacine, or typical or atypical neuroleptics may be helpful. Even baclofen, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, nicotine, and Botox have been used. These require consultation with a specialist.

As for other chronic medical conditions, tics and persisting stereotypies deserve a comprehensive approach, including repeated education of the parent and child, evaluation for comorbidity, school accommodations, building other strengths and social support, and only rarely pulling out your prescription pad.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She has no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

As an experienced clinician who has seen tics and habits in your patients come and go, you may be surprised by the amount of concern parents express about them. At times, it seems, and may be, that the parent’s attention to the habit actually keeps it going! This does not always mean that the child keeps doing the habit to aggravate the parent, as parental correction may amp up the child’s anxiety, which may make the habit worse.

As with other parent concerns, both empathizing with their worry and providing evidence-based information is helpful in relieving their distress.

Habits are complex behaviors done the same way repeatedly. Habits can have a strong protective effect on our lives and be a foundation for success when they ensure that we wash our hands (protection from infection), help us know where the keys are (efficiency), or soothe us to sleep (bedtime routines).

Tics are “involuntary” (meaning often, but not always, suppressible), brief, abrupt, repeated movements usually of the face, head, or neck. More complex, apparently meaningless movements may fall into the category of stereotypies. If they last more than 4 weeks, are driven, and cause marked dysfunction or significant self-injury, they may even qualify as stereotypic movement disorder.

It is good to know that repeated behaviors such as thumb sucking, nail/lip biting, hair twirling, body rocking, self biting, and head banging are relatively common in childhood, and often (but not mostly) disappear after age 4. I like to set the expectation that one habit or tic often evolves to another to reduce panic when this happens. Thumb and hand sucking at a younger developmental age may be replaced by body rocking and head banging, and later by nail biting and finger and foot tapping.

Even in college, habits are common and stress-related such as touching the face; playing with hair, pens, or jewelry; shaking a leg; tapping fingers; or scratching the head. Parents may connect some of these to acne or poor hygiene (a good opening for coaching!) but more importantly they may be accompanied by general distress, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and impulsive aggressive symptoms, which need to be looked for and addressed.

Stereotypies occur in about 20% of typically developing children (called “primary”) and are classified into:

• Common behaviors (such as, rocking, head banging, finger drumming, pencil tapping, hair twisting),

• Head nodding.

• Complex motor movements (such as hand and arm flapping/waving).

Habits – including nail biting, lip chewing, and nose picking – also may be diagnosed as stereotypic movement disorders, although ICD-10 lists includes them as “other specified behavioral and emotional disorders.”

For both conditions, the behavior must not be better accounted for by a compulsion, a tic disorder, part of autism, hair pulling (trichotillomania), or paroxysmal dyskinesias.

So what is the difference between motor stereotypies and tics (and why do you care)? Motor stereotypies begin before 3 years in more than 60%, whereas tics appear later (mean 5-7 years). Stereotypies are more fixed in their pattern, compared with tics that keep shifting form, disappearing, and reappearing. Stereotypies frequently involve the arms, hands, or the entire body, while tics involve the eyes, face, head, and shoulders. Stereotypies are more fixed, rhythmic, and prolonged (most more than 10 seconds) than tics, which are mostly brief, rapid, random, and fluctuating.

One key distinguishing factor is that tics have a premonitory urge and result in a sense of relief after the tic is performed. This also means that they can be suppressed to some extent when the situation requires. While both may occur more during anxiety, excitement, or fatigue, stereotypic movements, unlike tics, also are common when the child is engrossed.

Tics can occur as a side effect of medications such as stimulants and may decrease by lowering the dose, but tics also come and go, so the impact of a medication can be hard to sort out.

One vocal or multiple motor tics occurring many times per day starting before age 18 years and lasting more than 1 year are considered chronic; those occurring less than 1 year are transient. Chronic multiple motor tics accompanied by vocalizations, even sniffing or throat clearing, qualify as Tourette syndrome. The feared component of Tourette of coprolalia (saying bad words or gestures) is fortunately rare. These diagnoses can only be made after ruling out the effects of medication or another neurological condition such as Sydenham’s chorea (resulting from infection via group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, the bacterium that causes rheumatic fever) or PANDAS (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections).

The importance of distinguishing tics from stereotypies is in the treatment options, differential diagnosis, and prognosis. Some families (and certainly the kids themselves) do not even notice that they are moving abnormally even though 25% have at least one family member with a similar behavior. But many parents are upset about the potential for teasing and stigmatization. When you ask them directly what they are afraid of, they often admit fearing an underlying diagnosis such as intellectual disability, autism, or Tourette syndrome. The first two are straightforward to rule in or out, but Tourette can be subtle. If parents don’t bring up the possibilities, it is worth telling them directly which underlying conditions can be ruled out.

There are many conditions comorbid with tics including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), learning disorder (LD), behavioral, developmental or social problems, and mood or anxiety disorders. This clearly means that a comprehensive evaluation looking specifically for these conditions is needed when a child has chronic tics. Typically developing children with complex arm or hand movements also are more likely to have ADHD (30%), LD (20%), obsessive-compulsive behaviors (10%), or tics (18%).

Tics and stereotypies may be annoying, but generally are not harmful or progressive, although repeated movements such as skin or nose picking may result in scars or infections, and severe head banging can lead to eye injuries. Frequently repeated motor acts can cause significant muscle pain and fatigue. The most common problems are probably injury to self-esteem or oppositional behavior as a result of repeated (and fruitless) nagging or punishment by parents, even if well-meaning.

Since they occur so often along with comorbid conditions, our job includes determining the most problematic aspect before advising on a treatment. Both tics and stereotypies may be reduced by distraction, but the effect on stereotypies is faster and more certain. You can make this intervention in the office by simply asking how the child can tell when they make the movement and have them plan out what they could do instead. An example might be to shift a hand flapping movement (that makes peers think of autism) into more acceptable fist clenching. Habit reversal training or differential reinforcement based on a functional analysis can be taught by psychologists when this simple suggestion is not effective. When tics are severe, teacher education and school accommodations (504 Plan with extended time, scribe, private location for tic breaks) may be needed.

Medication is not indicated for most tics because most are mild. If ADHD is present, tics may actually be reduced by stimulants or atomoxetine rather than worsened. If the tic is severe and habit reversal training has not been successful, alpha agonists such as clonidine or guanfacine, or typical or atypical neuroleptics may be helpful. Even baclofen, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, nicotine, and Botox have been used. These require consultation with a specialist.

As for other chronic medical conditions, tics and persisting stereotypies deserve a comprehensive approach, including repeated education of the parent and child, evaluation for comorbidity, school accommodations, building other strengths and social support, and only rarely pulling out your prescription pad.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She has no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

ACOG offers strategies to reduce unintended pregnancy

A new Committee Opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in Obstetrics & Gynecology outlines the current barriers women face when attempting to obtain contraception and provides strategies to overcome these barriers.

Unintended pregnancy and abortion rates are higher in the United States than in most other developed countries, says ACOG; the most recent data report that 49% of US pregnancies are unintended.1

The cost of unintended pregnancy

The human cost of unintended pregnancy is high, says ACOG, because women must choose to carry the pregnancy to term and keep the baby, decide for adoption, or undergo abortion. Women and their families struggle with this challenge for medical, ethical, social, legal, and financial reasons. US births from unintended pregnancies resulted in approximately $12.5 billion in government expenditures in 2008. Affordable access to contraceptives would not only improve health but also reduce costs, as each dollar spent on publicly funded contraceptive services saves the US health-care system nearly $6.1

“The most effective way to reduce abortion rates is to prevent unintended pregnancy by improving access to consistent, effective, and affordable contraception,” states the Committee Opinion.1

What are barriers to use?

Major barriers to contraceptive use include lack of knowledge, misperceptions, and exaggerated concerns about safety among patients and health-care professionals, says the Committee.

Patients are concerned that oral contraceptives are linked to major health problems, that intrauterine devices (IUDs) carry a high risk of infection, and that certain contraceptives are abortifacients (although no FDA-approved contraceptive is an abortifacient).

Health-care professionals also may have knowledge deficits: some are uncertain about the risks and benefits of IUDs and lack knowledge about correct patient selection and contraindications.1

What strategies does ACOG support?

One in four American women who obtain contraceptive services seek them at publicly funded family planning clinics, cites ACOG.1 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides that all FDA-approved contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and patient contraceptive education and counseling are covered for women without cost sharing for all new and revised health plans and Medicaid. However, many employers are now exempt. Women covered by exempted employers and those who remain uninsured will not benefit from ACA coverage. For these women, cost barriers persist and the most effective methods (IUDs, contraceptive implant) likely will be unattainable, says ACOG.1

Insurance companies, clinic systems, or pharmacy and therapeutics committees create additional barriers, including the number of products dispensed at one time. Insurance plans prevent 73% of women from receiving more than a 1 month supply of contraception at a time, yet most women are unable to obtain refills on a timely basis. Some systems require that women “fail” certain contraceptive methods before a more expensive method (IUD, implant) will be covered. ACOG states: “All FDA-approved contraceptive methods should be available to all insured women without cost sharing and without the need to ‘fail’ certain methods first. In the absence of contraindications, patient choice and efficacy should be the principal factors in choosing one method of contraception over another.”1

Additional strategies ACOG supports and recommends to ensure affordable and accessible contraception include:

- Full implementation of the ACA requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all FDA-approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options from within one method category (levonorgestrel as well as copper IUDs)

- Easily accessible alternative contraceptive coverage for women who receive health insurance through employers and plans exempted from the contraceptive coverage requirement

- Medicaid expansion in all states, an action critical to the ability of low-income women to obtain improved access to contraceptives

- Adequate funding for the federal Title X family planning program and Medicaid family planning services to ensure contraceptive availability for low-income women, including the use of public funds for contraceptive provision at the time of abortion

- Sufficient compensation for contraceptive services by public and private payers to ensure access, including appropriate payment for clinician services and acquisition-cost reimbursement for supplies

- Age-appropriate, medically accurate, comprehensive sexuality education that includes information on abstinence as well as the full range of FDA-approved contraceptives

- Confidential, comprehensive contraceptive care and access to contraceptive methods for adolescents without mandated parental notification or consent, including confidentiality in billing and insurance claims processing procedures

To see all of ACOG’s recommendations, access the full report.

Reference

- Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 615: Access to Contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):250–255. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20150102T2211197738.

A new Committee Opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in Obstetrics & Gynecology outlines the current barriers women face when attempting to obtain contraception and provides strategies to overcome these barriers.

Unintended pregnancy and abortion rates are higher in the United States than in most other developed countries, says ACOG; the most recent data report that 49% of US pregnancies are unintended.1

The cost of unintended pregnancy

The human cost of unintended pregnancy is high, says ACOG, because women must choose to carry the pregnancy to term and keep the baby, decide for adoption, or undergo abortion. Women and their families struggle with this challenge for medical, ethical, social, legal, and financial reasons. US births from unintended pregnancies resulted in approximately $12.5 billion in government expenditures in 2008. Affordable access to contraceptives would not only improve health but also reduce costs, as each dollar spent on publicly funded contraceptive services saves the US health-care system nearly $6.1

“The most effective way to reduce abortion rates is to prevent unintended pregnancy by improving access to consistent, effective, and affordable contraception,” states the Committee Opinion.1

What are barriers to use?

Major barriers to contraceptive use include lack of knowledge, misperceptions, and exaggerated concerns about safety among patients and health-care professionals, says the Committee.

Patients are concerned that oral contraceptives are linked to major health problems, that intrauterine devices (IUDs) carry a high risk of infection, and that certain contraceptives are abortifacients (although no FDA-approved contraceptive is an abortifacient).

Health-care professionals also may have knowledge deficits: some are uncertain about the risks and benefits of IUDs and lack knowledge about correct patient selection and contraindications.1

What strategies does ACOG support?

One in four American women who obtain contraceptive services seek them at publicly funded family planning clinics, cites ACOG.1 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides that all FDA-approved contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and patient contraceptive education and counseling are covered for women without cost sharing for all new and revised health plans and Medicaid. However, many employers are now exempt. Women covered by exempted employers and those who remain uninsured will not benefit from ACA coverage. For these women, cost barriers persist and the most effective methods (IUDs, contraceptive implant) likely will be unattainable, says ACOG.1

Insurance companies, clinic systems, or pharmacy and therapeutics committees create additional barriers, including the number of products dispensed at one time. Insurance plans prevent 73% of women from receiving more than a 1 month supply of contraception at a time, yet most women are unable to obtain refills on a timely basis. Some systems require that women “fail” certain contraceptive methods before a more expensive method (IUD, implant) will be covered. ACOG states: “All FDA-approved contraceptive methods should be available to all insured women without cost sharing and without the need to ‘fail’ certain methods first. In the absence of contraindications, patient choice and efficacy should be the principal factors in choosing one method of contraception over another.”1

Additional strategies ACOG supports and recommends to ensure affordable and accessible contraception include:

- Full implementation of the ACA requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all FDA-approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options from within one method category (levonorgestrel as well as copper IUDs)

- Easily accessible alternative contraceptive coverage for women who receive health insurance through employers and plans exempted from the contraceptive coverage requirement

- Medicaid expansion in all states, an action critical to the ability of low-income women to obtain improved access to contraceptives

- Adequate funding for the federal Title X family planning program and Medicaid family planning services to ensure contraceptive availability for low-income women, including the use of public funds for contraceptive provision at the time of abortion

- Sufficient compensation for contraceptive services by public and private payers to ensure access, including appropriate payment for clinician services and acquisition-cost reimbursement for supplies

- Age-appropriate, medically accurate, comprehensive sexuality education that includes information on abstinence as well as the full range of FDA-approved contraceptives

- Confidential, comprehensive contraceptive care and access to contraceptive methods for adolescents without mandated parental notification or consent, including confidentiality in billing and insurance claims processing procedures

To see all of ACOG’s recommendations, access the full report.

A new Committee Opinion published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in Obstetrics & Gynecology outlines the current barriers women face when attempting to obtain contraception and provides strategies to overcome these barriers.

Unintended pregnancy and abortion rates are higher in the United States than in most other developed countries, says ACOG; the most recent data report that 49% of US pregnancies are unintended.1

The cost of unintended pregnancy

The human cost of unintended pregnancy is high, says ACOG, because women must choose to carry the pregnancy to term and keep the baby, decide for adoption, or undergo abortion. Women and their families struggle with this challenge for medical, ethical, social, legal, and financial reasons. US births from unintended pregnancies resulted in approximately $12.5 billion in government expenditures in 2008. Affordable access to contraceptives would not only improve health but also reduce costs, as each dollar spent on publicly funded contraceptive services saves the US health-care system nearly $6.1

“The most effective way to reduce abortion rates is to prevent unintended pregnancy by improving access to consistent, effective, and affordable contraception,” states the Committee Opinion.1

What are barriers to use?

Major barriers to contraceptive use include lack of knowledge, misperceptions, and exaggerated concerns about safety among patients and health-care professionals, says the Committee.

Patients are concerned that oral contraceptives are linked to major health problems, that intrauterine devices (IUDs) carry a high risk of infection, and that certain contraceptives are abortifacients (although no FDA-approved contraceptive is an abortifacient).

Health-care professionals also may have knowledge deficits: some are uncertain about the risks and benefits of IUDs and lack knowledge about correct patient selection and contraindications.1

What strategies does ACOG support?

One in four American women who obtain contraceptive services seek them at publicly funded family planning clinics, cites ACOG.1 The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides that all FDA-approved contraceptive methods, sterilization procedures, and patient contraceptive education and counseling are covered for women without cost sharing for all new and revised health plans and Medicaid. However, many employers are now exempt. Women covered by exempted employers and those who remain uninsured will not benefit from ACA coverage. For these women, cost barriers persist and the most effective methods (IUDs, contraceptive implant) likely will be unattainable, says ACOG.1

Insurance companies, clinic systems, or pharmacy and therapeutics committees create additional barriers, including the number of products dispensed at one time. Insurance plans prevent 73% of women from receiving more than a 1 month supply of contraception at a time, yet most women are unable to obtain refills on a timely basis. Some systems require that women “fail” certain contraceptive methods before a more expensive method (IUD, implant) will be covered. ACOG states: “All FDA-approved contraceptive methods should be available to all insured women without cost sharing and without the need to ‘fail’ certain methods first. In the absence of contraindications, patient choice and efficacy should be the principal factors in choosing one method of contraception over another.”1

Additional strategies ACOG supports and recommends to ensure affordable and accessible contraception include:

- Full implementation of the ACA requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all FDA-approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options from within one method category (levonorgestrel as well as copper IUDs)

- Easily accessible alternative contraceptive coverage for women who receive health insurance through employers and plans exempted from the contraceptive coverage requirement

- Medicaid expansion in all states, an action critical to the ability of low-income women to obtain improved access to contraceptives

- Adequate funding for the federal Title X family planning program and Medicaid family planning services to ensure contraceptive availability for low-income women, including the use of public funds for contraceptive provision at the time of abortion

- Sufficient compensation for contraceptive services by public and private payers to ensure access, including appropriate payment for clinician services and acquisition-cost reimbursement for supplies

- Age-appropriate, medically accurate, comprehensive sexuality education that includes information on abstinence as well as the full range of FDA-approved contraceptives

- Confidential, comprehensive contraceptive care and access to contraceptive methods for adolescents without mandated parental notification or consent, including confidentiality in billing and insurance claims processing procedures

To see all of ACOG’s recommendations, access the full report.

Reference

- Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 615: Access to Contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):250–255. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20150102T2211197738.

Reference

- Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 615: Access to Contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):250–255. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20150102T2211197738.

Antifungal treatment may cause DNA strain type switching in onychomycosis

Although DNA strain type switches are known to be a natural occurrence in patients with onychomycosis, increases in strain type switching that follow treatment failure could be an antifungal-induced response, according to the results of a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“The dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum is responsible for the majority (~80%) of [onychomycosis] cases, many of which frequently relapse after successful antifungal treatment,” noted the study authors, led by Dr. Aditya K. Gupta of the University of Toronto. Despite several previous studies of various facets related to onychomycosis, “data outlining onychomycosis infections of T. rubrum with DNA strain type, treatments, outcome and geographical location are still warranted,” they added (Br. J. Dermatol. 2015;172:74-80).

Dr. Gupta and his associates examined 50 adults infected with T. rubrum, determined via analysis of toenail specimens from onychomycosis patients in southwest Ontario. The patients were divided into cohorts based on the treatment they received: oral terbinafine, laser, or placebo (no terbinafine and no laser). Typing of DNA strains was done only in culture-positive samples before and after treatment, leaving a study population of six in the terbinafine group, nine in the laser group, and eight in the placebo group.

Half of the terbinafine subjects were prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg/day for 12 weeks, while the other three received oral terbinafine 250 mg/day pulse therapy at on/off intervals of 2 weeks up to 12 weeks.

The investigators also used three DNA strains known to be common in Europe for comparison and found that six distinct strains, labeled A-F, accounted for 94% of the T. rubrum strains – these strains corresponded to the European ones. However, three other strains (6% of strains) were found that investigators concluded were native to North America.

Strain type switching occurred in five (83%) of the terbinafine subjects, five (56%) of the laser cohort subjects, and two (25%) of those in the placebo cohort. Roughly half of the type switches noted in the terbinafine cohort were associated with mycological cures and were followed by relapse shortly thereafter. Dr. Gupta and his associates also found that all DNA strains in this cohort were susceptible to terbinafine while in vitro. Strain types in the laser and placebo cohorts did not show any signs of intermittent cures.

The patients were sampled at intervals of 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 weeks of treatment, and T. rubrum DNA strain types were determined at week 0 (n = 6) and week 48 (n = 1) or 72 (n = 5). Patients in the laser cohort were treated at weeks 0, 8, and 16 and sampled at weeks 0, 8, 16, 24, and 48, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 9) and week 24 (n = 5) or 48 (n = 4). Finally, placebo patients were sampled at the same regularity as those in the laser cohort, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 8) and week 24 (n = 1) or 48 (n = 7), they reported.

“The T. rubrum DNA strain type switches observed in ongoing infections among all treatment groups could be attributed to microevolution or coinfections of DNA strains,” the researchers noted. “The presence of coinfecting T. rubrum DNA strains that flux with environmental conditions or local niches could account for the DNA strain type switches observed in all treatment groups, where only the relatively stable types are able to propagate in culture,” they added.

Dr. Gupta and his associates did not disclose any source of funding or any relevant conflicts of interest.

Although DNA strain type switches are known to be a natural occurrence in patients with onychomycosis, increases in strain type switching that follow treatment failure could be an antifungal-induced response, according to the results of a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“The dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum is responsible for the majority (~80%) of [onychomycosis] cases, many of which frequently relapse after successful antifungal treatment,” noted the study authors, led by Dr. Aditya K. Gupta of the University of Toronto. Despite several previous studies of various facets related to onychomycosis, “data outlining onychomycosis infections of T. rubrum with DNA strain type, treatments, outcome and geographical location are still warranted,” they added (Br. J. Dermatol. 2015;172:74-80).

Dr. Gupta and his associates examined 50 adults infected with T. rubrum, determined via analysis of toenail specimens from onychomycosis patients in southwest Ontario. The patients were divided into cohorts based on the treatment they received: oral terbinafine, laser, or placebo (no terbinafine and no laser). Typing of DNA strains was done only in culture-positive samples before and after treatment, leaving a study population of six in the terbinafine group, nine in the laser group, and eight in the placebo group.

Half of the terbinafine subjects were prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg/day for 12 weeks, while the other three received oral terbinafine 250 mg/day pulse therapy at on/off intervals of 2 weeks up to 12 weeks.

The investigators also used three DNA strains known to be common in Europe for comparison and found that six distinct strains, labeled A-F, accounted for 94% of the T. rubrum strains – these strains corresponded to the European ones. However, three other strains (6% of strains) were found that investigators concluded were native to North America.

Strain type switching occurred in five (83%) of the terbinafine subjects, five (56%) of the laser cohort subjects, and two (25%) of those in the placebo cohort. Roughly half of the type switches noted in the terbinafine cohort were associated with mycological cures and were followed by relapse shortly thereafter. Dr. Gupta and his associates also found that all DNA strains in this cohort were susceptible to terbinafine while in vitro. Strain types in the laser and placebo cohorts did not show any signs of intermittent cures.

The patients were sampled at intervals of 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 weeks of treatment, and T. rubrum DNA strain types were determined at week 0 (n = 6) and week 48 (n = 1) or 72 (n = 5). Patients in the laser cohort were treated at weeks 0, 8, and 16 and sampled at weeks 0, 8, 16, 24, and 48, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 9) and week 24 (n = 5) or 48 (n = 4). Finally, placebo patients were sampled at the same regularity as those in the laser cohort, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 8) and week 24 (n = 1) or 48 (n = 7), they reported.

“The T. rubrum DNA strain type switches observed in ongoing infections among all treatment groups could be attributed to microevolution or coinfections of DNA strains,” the researchers noted. “The presence of coinfecting T. rubrum DNA strains that flux with environmental conditions or local niches could account for the DNA strain type switches observed in all treatment groups, where only the relatively stable types are able to propagate in culture,” they added.

Dr. Gupta and his associates did not disclose any source of funding or any relevant conflicts of interest.

Although DNA strain type switches are known to be a natural occurrence in patients with onychomycosis, increases in strain type switching that follow treatment failure could be an antifungal-induced response, according to the results of a study published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“The dermatophyte Trichophyton rubrum is responsible for the majority (~80%) of [onychomycosis] cases, many of which frequently relapse after successful antifungal treatment,” noted the study authors, led by Dr. Aditya K. Gupta of the University of Toronto. Despite several previous studies of various facets related to onychomycosis, “data outlining onychomycosis infections of T. rubrum with DNA strain type, treatments, outcome and geographical location are still warranted,” they added (Br. J. Dermatol. 2015;172:74-80).

Dr. Gupta and his associates examined 50 adults infected with T. rubrum, determined via analysis of toenail specimens from onychomycosis patients in southwest Ontario. The patients were divided into cohorts based on the treatment they received: oral terbinafine, laser, or placebo (no terbinafine and no laser). Typing of DNA strains was done only in culture-positive samples before and after treatment, leaving a study population of six in the terbinafine group, nine in the laser group, and eight in the placebo group.

Half of the terbinafine subjects were prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg/day for 12 weeks, while the other three received oral terbinafine 250 mg/day pulse therapy at on/off intervals of 2 weeks up to 12 weeks.

The investigators also used three DNA strains known to be common in Europe for comparison and found that six distinct strains, labeled A-F, accounted for 94% of the T. rubrum strains – these strains corresponded to the European ones. However, three other strains (6% of strains) were found that investigators concluded were native to North America.

Strain type switching occurred in five (83%) of the terbinafine subjects, five (56%) of the laser cohort subjects, and two (25%) of those in the placebo cohort. Roughly half of the type switches noted in the terbinafine cohort were associated with mycological cures and were followed by relapse shortly thereafter. Dr. Gupta and his associates also found that all DNA strains in this cohort were susceptible to terbinafine while in vitro. Strain types in the laser and placebo cohorts did not show any signs of intermittent cures.

The patients were sampled at intervals of 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 weeks of treatment, and T. rubrum DNA strain types were determined at week 0 (n = 6) and week 48 (n = 1) or 72 (n = 5). Patients in the laser cohort were treated at weeks 0, 8, and 16 and sampled at weeks 0, 8, 16, 24, and 48, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 9) and week 24 (n = 5) or 48 (n = 4). Finally, placebo patients were sampled at the same regularity as those in the laser cohort, with T. rubrum DNA strain types determined at week 0 (n = 8) and week 24 (n = 1) or 48 (n = 7), they reported.

“The T. rubrum DNA strain type switches observed in ongoing infections among all treatment groups could be attributed to microevolution or coinfections of DNA strains,” the researchers noted. “The presence of coinfecting T. rubrum DNA strains that flux with environmental conditions or local niches could account for the DNA strain type switches observed in all treatment groups, where only the relatively stable types are able to propagate in culture,” they added.

Dr. Gupta and his associates did not disclose any source of funding or any relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Antifungal treatment of onychomycosis could induce higher rates of DNA strain type switching in certain patients.

Major finding: Strain type switching occurred in 83% of the terbinafine group, 56% of the laser group, and 25% of the placebo group.

Data source: Cohort study of 23 individuals selected from 50 adults with onychomycosis who contributed samples to determine strain types.

Disclosures: The study authors did not disclose any source of funding or any relevant conflicts of interest.

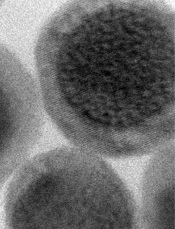

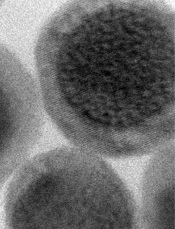

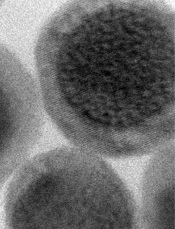

Gains in CLL are ‘Advance of the Year’

Credit: NIH

The “transformation” of treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the “Advance of the Year” for 2015, according to a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The report said 4 therapies that were recently approved in the US fill a major unmet need for CLL patients—obinutuzumab and ofatumumab for patients with previously untreated CLL and idelalisib and ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory CLL.

“For many older patients, especially, these drugs essentially offer the first chance at effective treatment, since the side effects of earlier options were simply too toxic for many to handle,” said Gregory Masters, MD, ASCO expert and co-executive editor of the report.

The report, “Clinical Cancer Advances 2015: ASCO’s Annual Report on Progress Against Cancer,” is available in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and on ASCO’s cancer research advocacy website, CancerProgress.net.

The report was developed under the direction of an 18-person editorial board of experts from a wide range of oncology specialties. It features:

- The top cancer research advances of the past year: Identifying major trends in cancer prevention and screening, treatment, quality of life, survivorship, and tumor biology

- A Decade in Review: Recounting improvements in cancer care since the first issue of Clinical Cancer Advances

- The 10-Year Horizon: Previewing trends likely to shape the next decade of cancer care, including genomic technology, nanomedicine, and health information technologies

- Progress in Rare Cancers: Highlighting promising early achievements in treating certain uncommon but devastating cancers.

“This has truly been a banner year for CLL and for clinical cancer research as a whole,” said ASCO President Peter P. Yu, MD. “Advances in cancer prevention and care, especially those in precision medicine, are offering stunning new possibilities for patients.” ![]()

Credit: NIH

The “transformation” of treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the “Advance of the Year” for 2015, according to a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The report said 4 therapies that were recently approved in the US fill a major unmet need for CLL patients—obinutuzumab and ofatumumab for patients with previously untreated CLL and idelalisib and ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory CLL.

“For many older patients, especially, these drugs essentially offer the first chance at effective treatment, since the side effects of earlier options were simply too toxic for many to handle,” said Gregory Masters, MD, ASCO expert and co-executive editor of the report.

The report, “Clinical Cancer Advances 2015: ASCO’s Annual Report on Progress Against Cancer,” is available in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and on ASCO’s cancer research advocacy website, CancerProgress.net.

The report was developed under the direction of an 18-person editorial board of experts from a wide range of oncology specialties. It features:

- The top cancer research advances of the past year: Identifying major trends in cancer prevention and screening, treatment, quality of life, survivorship, and tumor biology

- A Decade in Review: Recounting improvements in cancer care since the first issue of Clinical Cancer Advances

- The 10-Year Horizon: Previewing trends likely to shape the next decade of cancer care, including genomic technology, nanomedicine, and health information technologies

- Progress in Rare Cancers: Highlighting promising early achievements in treating certain uncommon but devastating cancers.

“This has truly been a banner year for CLL and for clinical cancer research as a whole,” said ASCO President Peter P. Yu, MD. “Advances in cancer prevention and care, especially those in precision medicine, are offering stunning new possibilities for patients.” ![]()

Credit: NIH

The “transformation” of treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the “Advance of the Year” for 2015, according to a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The report said 4 therapies that were recently approved in the US fill a major unmet need for CLL patients—obinutuzumab and ofatumumab for patients with previously untreated CLL and idelalisib and ibrutinib for patients with relapsed or refractory CLL.

“For many older patients, especially, these drugs essentially offer the first chance at effective treatment, since the side effects of earlier options were simply too toxic for many to handle,” said Gregory Masters, MD, ASCO expert and co-executive editor of the report.

The report, “Clinical Cancer Advances 2015: ASCO’s Annual Report on Progress Against Cancer,” is available in the Journal of Clinical Oncology and on ASCO’s cancer research advocacy website, CancerProgress.net.

The report was developed under the direction of an 18-person editorial board of experts from a wide range of oncology specialties. It features:

- The top cancer research advances of the past year: Identifying major trends in cancer prevention and screening, treatment, quality of life, survivorship, and tumor biology

- A Decade in Review: Recounting improvements in cancer care since the first issue of Clinical Cancer Advances

- The 10-Year Horizon: Previewing trends likely to shape the next decade of cancer care, including genomic technology, nanomedicine, and health information technologies

- Progress in Rare Cancers: Highlighting promising early achievements in treating certain uncommon but devastating cancers.

“This has truly been a banner year for CLL and for clinical cancer research as a whole,” said ASCO President Peter P. Yu, MD. “Advances in cancer prevention and care, especially those in precision medicine, are offering stunning new possibilities for patients.” ![]()

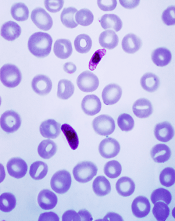

FDA puts drug on fast track to treat secondary AML

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation for CPX-351, a fixed-ratio combination of cytarabine and daunorubicin inside a lipid vesicle, to treat elderly patients with secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

In a phase 2 study of elderly AML patients, there was no significant difference in response or survival rates between patients who received CPX-351 and those who received cytarabine and daunorubicin.

However, CPX-351 conferred a significant response benefit among patients with poor cytogenetics and a significant survival benefit in patients with secondary AML.

“We are pleased that FDA has granted fast track status for CPX-351 for the treatment of elderly patients with secondary AML,” said Scott Jackson, Chief Executive Officer of Celator Pharmaceuticals, the company developing CPX-351.

“Our ongoing phase 3 study in these patients has completed enrollment, and we expect induction response rate data to be available in the second quarter of this year, and to have overall survival data, the primary endpoint of the study, in the first quarter of 2016.”

“If our phase 3 study comparing CPX-351 to the current standard of care is successful, the fast track designation may provide an added benefit of facilitating the [new drug application] review process.”

The FDA established the fast track designation process to expedite the review of drugs that are intended to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and that demonstrate the potential to address unmet medical needs.

The designation allows a drug’s developer to submit sections of a new drug application (NDA) on a rolling basis, so the FDA can review portions of the NDA as they are received instead of waiting for the entire NDA submission. A fast-track-designated product could be eligible for priority review if supported by clinical data at the time of NDA submission.

Phase 2 trial

In an article published in Blood last April, researchers reported results with CPX-351 in elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML. The study enrolled 126 patients who were 60 to 75 years of age.

They were randomized to receive CPX-351 (n=85) or “control” treatment consisting of cytarabine and daunorubicin (n=41). The treatment groups were well-balanced for disease and patient characteristics at baseline.

Overall, the response rate was 66.7% in the CPX-351 arm and 51.2% in the control arm (P=0.07). Among patients with adverse cytogenetics, the response rates were 77.3% and 38.5%, respectively (P=0.03). And among patients with secondary AML, response rates were 57.6% and 31.6%, respectively (P=0.06).

The median overall survival was 14.7 months in the CPX-351 arm and 12.9 months in the control arm. The median event-free survival was 6.5 months and 2.0 months, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant.

However, secondary AML patients treated with CPX-351 had significantly better overall survival than secondary AML patients in the control arm. The median overall survival was 12.1 months and 6.1 months, respectively (P=0.01). The median event-free survival was 4.5 months and 1.3 months, respectively (P=0.08).

Common adverse events included febrile neutropenia, infection, rash, diarrhea, nausea, edema, and constipation. There were minimal differences between the treatment arms in the incidence of these events.

The median time to neutrophil recovery was longer in the CPX-351 arm than in the control arm—36 days and 32 days, respectively. And the same was true for platelet recovery—37 days and 28 days, respectively.

Patients in the CPX-351 arm had a higher incidence of grade 3-4 infection than controls—70.6% and 43.9%, respectively—but not infection-related deaths—3.5% and 7.3%, respectively.

By day 60, 4.7% of patients in the CPX-351 arm and 14.6% of patients in the control arm had died. All of these deaths occurred in high-risk patients, particularly those with secondary AML. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation for CPX-351, a fixed-ratio combination of cytarabine and daunorubicin inside a lipid vesicle, to treat elderly patients with secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

In a phase 2 study of elderly AML patients, there was no significant difference in response or survival rates between patients who received CPX-351 and those who received cytarabine and daunorubicin.

However, CPX-351 conferred a significant response benefit among patients with poor cytogenetics and a significant survival benefit in patients with secondary AML.

“We are pleased that FDA has granted fast track status for CPX-351 for the treatment of elderly patients with secondary AML,” said Scott Jackson, Chief Executive Officer of Celator Pharmaceuticals, the company developing CPX-351.

“Our ongoing phase 3 study in these patients has completed enrollment, and we expect induction response rate data to be available in the second quarter of this year, and to have overall survival data, the primary endpoint of the study, in the first quarter of 2016.”

“If our phase 3 study comparing CPX-351 to the current standard of care is successful, the fast track designation may provide an added benefit of facilitating the [new drug application] review process.”

The FDA established the fast track designation process to expedite the review of drugs that are intended to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and that demonstrate the potential to address unmet medical needs.

The designation allows a drug’s developer to submit sections of a new drug application (NDA) on a rolling basis, so the FDA can review portions of the NDA as they are received instead of waiting for the entire NDA submission. A fast-track-designated product could be eligible for priority review if supported by clinical data at the time of NDA submission.

Phase 2 trial

In an article published in Blood last April, researchers reported results with CPX-351 in elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML. The study enrolled 126 patients who were 60 to 75 years of age.

They were randomized to receive CPX-351 (n=85) or “control” treatment consisting of cytarabine and daunorubicin (n=41). The treatment groups were well-balanced for disease and patient characteristics at baseline.

Overall, the response rate was 66.7% in the CPX-351 arm and 51.2% in the control arm (P=0.07). Among patients with adverse cytogenetics, the response rates were 77.3% and 38.5%, respectively (P=0.03). And among patients with secondary AML, response rates were 57.6% and 31.6%, respectively (P=0.06).