User login

Pseudobulbar affect: More common than you’d think

ORLANDO – The prevalence of pseudobulbar affect symptoms – that is, uncontrollable, disruptive outbursts of crying and/or laughing – is considerably greater across a range of neurologic disorders than previously appreciated, according to the largest-ever study to screen for this condition.

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) symptoms were found in the study to be more common among neurology patients under age 65; however, the adverse impact of PBA symptoms upon quality of life was greater in the elderly, Dr. David W. Crumpacker reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

He presented the results of the PRISM (PBA Registry Series) study, which enrolled 5,290 patients on the basis of having any of six neurologic disorders: Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, or traumatic brain injury. They were screened for the presence of PBA symptoms using the validated Center for Neurologic Study–Lability Scale (CNS-LS). A score of 13 or more was deemed positive, based upon its demonstrated good predictive value for physician diagnosis of PBA in patients with ALS.

The CNS-LS is a simple test that can be completed quickly by either the patient or caregiver. The test is well-suited for routine use in clinical practice, noted Dr. W. Crumpacker, a psychiatrist at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas.

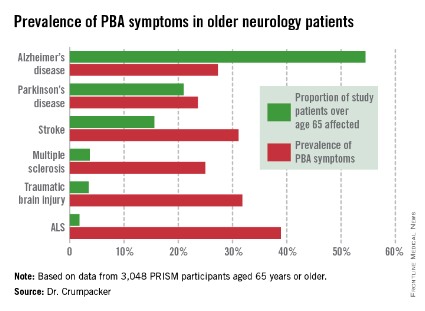

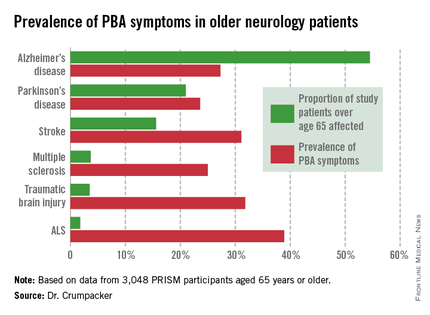

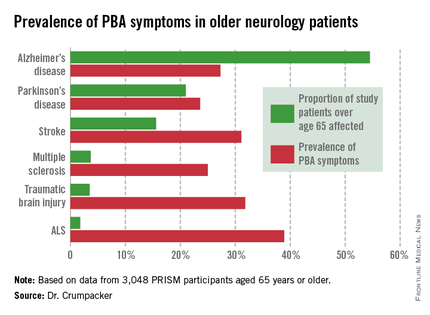

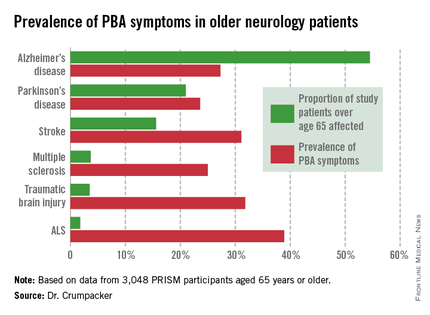

The overall prevalence of PBA symptoms among the 3,048 PRISM participants aged 65 years or older was 27.4%, with the highest rate seen in patients having ALS (see chart). In contrast, the prevalence of PBA symptoms among patients under age 65 years was 49.5%, with the highest rate – 56.9% – being seen in traumatic brain injury patients.

Patients or caregivers were asked to rate on a 0-10 scale the impact their primary neurologic disease has had on their quality of life. Patients 65 years and older with PBA symptoms reported a significantly greater negative impact than did those without PBA symptoms, with mean scores on the quality of life impact scale of 6.3 vs. 4.6. The quality of life difference between those with PBA symptoms and those without was significant for patients with each of the neurologic diseases except for ALS.

As another measure of the adverse impact of having PBA symptoms, 56% of affected older patients were on at least one antipsychotic or antidepressant, compared with 35% of older patients without PBA symptoms.

PBA is thought to result from injury to neurologic pathways that regulate emotional expression as a secondary consequence of a variety of neurologic disorders.

In an interview, Dr. Crumpacker said PBA is greatly underdiagnosed and often gets misdiagnosed as depression.

"The symptoms are extremely disturbing to others, and patients are acutely aware of that. I tell my friends in neurology, it’s the psychiatric pathology that causes people problems in their lives. No one gets divorced over neurologic pathology, they get divorced over psychiatric pathology. It’s not, ‘I got a divorce because he had a stroke.’ " "It’s "We got divorced because he had a stroke and it changed his personality; he was a different person and I couldn’t be around him anymore,’ " the psychiatrist said.

PBA became a diagnosable disorder with its own ICD-9 code, albeit a diagnosis that can’t be made in the absence of neurologic pathology, at the behest of the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Crumpacker explained. The impetus was the discovery of an effective treatment, dextromethorphan HBr and quinidine sulfate (Nuedexta), which received FDA approval for PBA 3 years ago.

Nuedexta’s development as the sole medication indicated for PBA was serendipitous, according to Dr. Crumpacker.

"The drug was being tested in Alzheimer’s disease. The jury is still out on whether it helps. But families of study participants came back saying, ‘You know that stuff dad used to do – the crying, the inappropriate laughter, the anger? He doesn’t do those kinds of things anymore,’ " Dr. Crumpacker recalled.

He reported serving on a scientific advisory board for Avanir Pharmaceuticals, which markets Nuedexta.

ORLANDO – The prevalence of pseudobulbar affect symptoms – that is, uncontrollable, disruptive outbursts of crying and/or laughing – is considerably greater across a range of neurologic disorders than previously appreciated, according to the largest-ever study to screen for this condition.

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) symptoms were found in the study to be more common among neurology patients under age 65; however, the adverse impact of PBA symptoms upon quality of life was greater in the elderly, Dr. David W. Crumpacker reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

He presented the results of the PRISM (PBA Registry Series) study, which enrolled 5,290 patients on the basis of having any of six neurologic disorders: Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, or traumatic brain injury. They were screened for the presence of PBA symptoms using the validated Center for Neurologic Study–Lability Scale (CNS-LS). A score of 13 or more was deemed positive, based upon its demonstrated good predictive value for physician diagnosis of PBA in patients with ALS.

The CNS-LS is a simple test that can be completed quickly by either the patient or caregiver. The test is well-suited for routine use in clinical practice, noted Dr. W. Crumpacker, a psychiatrist at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas.

The overall prevalence of PBA symptoms among the 3,048 PRISM participants aged 65 years or older was 27.4%, with the highest rate seen in patients having ALS (see chart). In contrast, the prevalence of PBA symptoms among patients under age 65 years was 49.5%, with the highest rate – 56.9% – being seen in traumatic brain injury patients.

Patients or caregivers were asked to rate on a 0-10 scale the impact their primary neurologic disease has had on their quality of life. Patients 65 years and older with PBA symptoms reported a significantly greater negative impact than did those without PBA symptoms, with mean scores on the quality of life impact scale of 6.3 vs. 4.6. The quality of life difference between those with PBA symptoms and those without was significant for patients with each of the neurologic diseases except for ALS.

As another measure of the adverse impact of having PBA symptoms, 56% of affected older patients were on at least one antipsychotic or antidepressant, compared with 35% of older patients without PBA symptoms.

PBA is thought to result from injury to neurologic pathways that regulate emotional expression as a secondary consequence of a variety of neurologic disorders.

In an interview, Dr. Crumpacker said PBA is greatly underdiagnosed and often gets misdiagnosed as depression.

"The symptoms are extremely disturbing to others, and patients are acutely aware of that. I tell my friends in neurology, it’s the psychiatric pathology that causes people problems in their lives. No one gets divorced over neurologic pathology, they get divorced over psychiatric pathology. It’s not, ‘I got a divorce because he had a stroke.’ " "It’s "We got divorced because he had a stroke and it changed his personality; he was a different person and I couldn’t be around him anymore,’ " the psychiatrist said.

PBA became a diagnosable disorder with its own ICD-9 code, albeit a diagnosis that can’t be made in the absence of neurologic pathology, at the behest of the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Crumpacker explained. The impetus was the discovery of an effective treatment, dextromethorphan HBr and quinidine sulfate (Nuedexta), which received FDA approval for PBA 3 years ago.

Nuedexta’s development as the sole medication indicated for PBA was serendipitous, according to Dr. Crumpacker.

"The drug was being tested in Alzheimer’s disease. The jury is still out on whether it helps. But families of study participants came back saying, ‘You know that stuff dad used to do – the crying, the inappropriate laughter, the anger? He doesn’t do those kinds of things anymore,’ " Dr. Crumpacker recalled.

He reported serving on a scientific advisory board for Avanir Pharmaceuticals, which markets Nuedexta.

ORLANDO – The prevalence of pseudobulbar affect symptoms – that is, uncontrollable, disruptive outbursts of crying and/or laughing – is considerably greater across a range of neurologic disorders than previously appreciated, according to the largest-ever study to screen for this condition.

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) symptoms were found in the study to be more common among neurology patients under age 65; however, the adverse impact of PBA symptoms upon quality of life was greater in the elderly, Dr. David W. Crumpacker reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry.

He presented the results of the PRISM (PBA Registry Series) study, which enrolled 5,290 patients on the basis of having any of six neurologic disorders: Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, or traumatic brain injury. They were screened for the presence of PBA symptoms using the validated Center for Neurologic Study–Lability Scale (CNS-LS). A score of 13 or more was deemed positive, based upon its demonstrated good predictive value for physician diagnosis of PBA in patients with ALS.

The CNS-LS is a simple test that can be completed quickly by either the patient or caregiver. The test is well-suited for routine use in clinical practice, noted Dr. W. Crumpacker, a psychiatrist at Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas.

The overall prevalence of PBA symptoms among the 3,048 PRISM participants aged 65 years or older was 27.4%, with the highest rate seen in patients having ALS (see chart). In contrast, the prevalence of PBA symptoms among patients under age 65 years was 49.5%, with the highest rate – 56.9% – being seen in traumatic brain injury patients.

Patients or caregivers were asked to rate on a 0-10 scale the impact their primary neurologic disease has had on their quality of life. Patients 65 years and older with PBA symptoms reported a significantly greater negative impact than did those without PBA symptoms, with mean scores on the quality of life impact scale of 6.3 vs. 4.6. The quality of life difference between those with PBA symptoms and those without was significant for patients with each of the neurologic diseases except for ALS.

As another measure of the adverse impact of having PBA symptoms, 56% of affected older patients were on at least one antipsychotic or antidepressant, compared with 35% of older patients without PBA symptoms.

PBA is thought to result from injury to neurologic pathways that regulate emotional expression as a secondary consequence of a variety of neurologic disorders.

In an interview, Dr. Crumpacker said PBA is greatly underdiagnosed and often gets misdiagnosed as depression.

"The symptoms are extremely disturbing to others, and patients are acutely aware of that. I tell my friends in neurology, it’s the psychiatric pathology that causes people problems in their lives. No one gets divorced over neurologic pathology, they get divorced over psychiatric pathology. It’s not, ‘I got a divorce because he had a stroke.’ " "It’s "We got divorced because he had a stroke and it changed his personality; he was a different person and I couldn’t be around him anymore,’ " the psychiatrist said.

PBA became a diagnosable disorder with its own ICD-9 code, albeit a diagnosis that can’t be made in the absence of neurologic pathology, at the behest of the Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Crumpacker explained. The impetus was the discovery of an effective treatment, dextromethorphan HBr and quinidine sulfate (Nuedexta), which received FDA approval for PBA 3 years ago.

Nuedexta’s development as the sole medication indicated for PBA was serendipitous, according to Dr. Crumpacker.

"The drug was being tested in Alzheimer’s disease. The jury is still out on whether it helps. But families of study participants came back saying, ‘You know that stuff dad used to do – the crying, the inappropriate laughter, the anger? He doesn’t do those kinds of things anymore,’ " Dr. Crumpacker recalled.

He reported serving on a scientific advisory board for Avanir Pharmaceuticals, which markets Nuedexta.

AT THE AAGP ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: The prevalence of PBA symptoms among patients over age 65 years with any of six underlying neurologic disorders was 27.4%. That was significantly less than in younger patients with the same disorders, but the adverse effect of having PBA symptoms upon quality of life was markedly greater in the older group.

Data source: The PRISM study included 5,290 patients with Alzheimer’s disease or any of five other less common neurologic disorders, all of whom were screened for the presence of PBA symptoms using a brief validated measure.

Disclosures: The presenter serves on a scientific advisory board for Avanir Pharmaceuticals, which funded the PRISM study.

Why the ACA makes me appreciate hospital medicine more each day

When I moved to Maryland over a decade ago, my first job was at Kaiser Permanente, where I had a panel of office patients and occasionally rounded at the hospital. Ultimately, management gave us the option of being solely office-based and giving up hospital rounds or continuing to do both. Most of my colleagues jumped at the chance to give up the grueling 24-hour shifts – a full day in the office followed by in-house night call at our hospital. Ouch!

But a little voice inside my head told me not to give up my hospital skills, and I’m so glad I listened. Little did I know that I would soon be offered a full-time hospitalist position. What a lifestyle change! I went from working Monday through Friday with occasional weekend and night shifts, counting the months until my next vacation, to working block shifts and having "vacation" time every month. What’s more, unlike my days in private practice, when I often struggled to make ends meet, I could count on a steady paycheck.

And while many of our office-based colleagues currently thrive in primary care, the Affordable Care Act has made many rethink their future. The ACA has ushered in new payment rates and regulations that make it more challenging for some small practices to stay afloat, and impossible for others.

Since the ACA was passed in 2010, many hospitals have aggressively pursued and acquired physician practices, which allows them to reap the benefits of some incentives available under the Affordable Care Act, potentially a win-win for hospitals and struggling physicians alike. In addition, many primary care physicians have joined independent accountable care organizations to mitigate the challenges and reap the potential rewards of the ACA.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg. For instance, in its recently released 2015 budget request, the administration proposed cutting an additional $2 billion from health care through decreased payments to rural hospitals, reductions to postacute care, and reimbursements for care given to those Medicare beneficiaries whose bills go unpaid. Meanwhile, the Federation of American Hospitals, an organization representing over 1,000 providers of health care, is working on a study it hopes will help persuade lawmakers to forgo the proposed cuts.

In this seemingly never-ending flux of our new health care system, it appears that we hospitalists, for the moment, are faring quite well. And, relatively unburdened by these forces of flux, we are free to focus our energies on top-notch patient care.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

When I moved to Maryland over a decade ago, my first job was at Kaiser Permanente, where I had a panel of office patients and occasionally rounded at the hospital. Ultimately, management gave us the option of being solely office-based and giving up hospital rounds or continuing to do both. Most of my colleagues jumped at the chance to give up the grueling 24-hour shifts – a full day in the office followed by in-house night call at our hospital. Ouch!

But a little voice inside my head told me not to give up my hospital skills, and I’m so glad I listened. Little did I know that I would soon be offered a full-time hospitalist position. What a lifestyle change! I went from working Monday through Friday with occasional weekend and night shifts, counting the months until my next vacation, to working block shifts and having "vacation" time every month. What’s more, unlike my days in private practice, when I often struggled to make ends meet, I could count on a steady paycheck.

And while many of our office-based colleagues currently thrive in primary care, the Affordable Care Act has made many rethink their future. The ACA has ushered in new payment rates and regulations that make it more challenging for some small practices to stay afloat, and impossible for others.

Since the ACA was passed in 2010, many hospitals have aggressively pursued and acquired physician practices, which allows them to reap the benefits of some incentives available under the Affordable Care Act, potentially a win-win for hospitals and struggling physicians alike. In addition, many primary care physicians have joined independent accountable care organizations to mitigate the challenges and reap the potential rewards of the ACA.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg. For instance, in its recently released 2015 budget request, the administration proposed cutting an additional $2 billion from health care through decreased payments to rural hospitals, reductions to postacute care, and reimbursements for care given to those Medicare beneficiaries whose bills go unpaid. Meanwhile, the Federation of American Hospitals, an organization representing over 1,000 providers of health care, is working on a study it hopes will help persuade lawmakers to forgo the proposed cuts.

In this seemingly never-ending flux of our new health care system, it appears that we hospitalists, for the moment, are faring quite well. And, relatively unburdened by these forces of flux, we are free to focus our energies on top-notch patient care.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

When I moved to Maryland over a decade ago, my first job was at Kaiser Permanente, where I had a panel of office patients and occasionally rounded at the hospital. Ultimately, management gave us the option of being solely office-based and giving up hospital rounds or continuing to do both. Most of my colleagues jumped at the chance to give up the grueling 24-hour shifts – a full day in the office followed by in-house night call at our hospital. Ouch!

But a little voice inside my head told me not to give up my hospital skills, and I’m so glad I listened. Little did I know that I would soon be offered a full-time hospitalist position. What a lifestyle change! I went from working Monday through Friday with occasional weekend and night shifts, counting the months until my next vacation, to working block shifts and having "vacation" time every month. What’s more, unlike my days in private practice, when I often struggled to make ends meet, I could count on a steady paycheck.

And while many of our office-based colleagues currently thrive in primary care, the Affordable Care Act has made many rethink their future. The ACA has ushered in new payment rates and regulations that make it more challenging for some small practices to stay afloat, and impossible for others.

Since the ACA was passed in 2010, many hospitals have aggressively pursued and acquired physician practices, which allows them to reap the benefits of some incentives available under the Affordable Care Act, potentially a win-win for hospitals and struggling physicians alike. In addition, many primary care physicians have joined independent accountable care organizations to mitigate the challenges and reap the potential rewards of the ACA.

But this is only the tip of the iceberg. For instance, in its recently released 2015 budget request, the administration proposed cutting an additional $2 billion from health care through decreased payments to rural hospitals, reductions to postacute care, and reimbursements for care given to those Medicare beneficiaries whose bills go unpaid. Meanwhile, the Federation of American Hospitals, an organization representing over 1,000 providers of health care, is working on a study it hopes will help persuade lawmakers to forgo the proposed cuts.

In this seemingly never-ending flux of our new health care system, it appears that we hospitalists, for the moment, are faring quite well. And, relatively unburdened by these forces of flux, we are free to focus our energies on top-notch patient care.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a patient-engagement app for iOS.

Online reviews

The last time I gave the talk, "Help! I’ve Been Yelped!" to physicians, there was a full house, a sometimes defiant, sometimes incredulous but always engaged full house. Most physicians don’t like Yelp and other online doctor rating sites because of the potential for negative reviews.

In past columns, I’ve written about these sites and how to respond to negative reviews and comments. Now, I’m going to share data on the use of online reviews and why they are important.

We live in a digital world that values reviews. We compare hotels on TripAdvisor.com before booking them and read reviews on Amazon.com before ordering products. We "like" or "dislike" Facebook pages and give thumbs up or thumbs down to videos on YouTube. We even rate physicians’ comments on medical question-and-answer sites such as HealthTap.com.

But how much do all of these online ratings really matter? A 2012 Nielsen report that surveyed more than 28,000 Internet users in 56 countries found that online consumer reviews are the second-most-trusted source of brand information, following only recommendations from family and friends. In other words, we trust online reviews and use them to make our own decisions.

The same is true when it comes to shopping for a doctor. According to an Internet-based survey of 2,137 adults published in the February issue of JAMA, 59% of respondents said that online doctor ratings were either "somewhat important" or "very important" when choosing a physician (2014;11:734-5).

Similarly, the "2013 Industry View Report" by Software Advice found that 62% of respondents said they read online reviews when seeking a new doctor. Although HealthGrades.com was the most commonly used site, Yelp.com was the most trusted. Forty-four percent of those respondents considered Yelp the most trustworthy review site followed by Health Grades (31%), Vitals.com (17%), and ZocDoc.com (7%).

Whether or not we trust Yelp and other online review sites, our patients do. In the JAMA survey, 35% of respondents said that they selected a physician based on good ratings, while 37% said that they avoided a physician with negative reviews. The 2013 Industry View Report also found that 45% of respondents ranked "quality of care" as the most important type of information sought about a doctor. And since many patients equate service with quality, reviews that focus on service matter.

This isn’t an entirely bad thing. If we really listen to what patients are saying, their comments can help us to improve service and communication. And, in some instances, it can lead to stronger doctor-patient relationships. Like many other industries, health care is moving toward transparency, and doctor rating sites are a key component of that.

Dr. Jeffrey Benabio is a partner physician in the department of dermatology of the Southern California Permanente Group in San Diego and a volunteer clinical assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego. He has published numerous scientific articles and is a member and fellow of the American Academy of Dermatology, and a member of the Telemedicine Association and the American Medical Association, among others. He is board certified in dermatology as well as medicine and surgery in the state of California. Dr. Benabio has a special interest in the uses of social media for education and building dermatology practice. He is the founder of The Derm Blog, an educational website that has had more than 2 million unique visitors. Dr. Benabio is also a founding member and the skin care expert for Livestrong.com, a health and wellness website of Lance Armstrong’s the Livestrong Foundation. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter.

The last time I gave the talk, "Help! I’ve Been Yelped!" to physicians, there was a full house, a sometimes defiant, sometimes incredulous but always engaged full house. Most physicians don’t like Yelp and other online doctor rating sites because of the potential for negative reviews.

In past columns, I’ve written about these sites and how to respond to negative reviews and comments. Now, I’m going to share data on the use of online reviews and why they are important.

We live in a digital world that values reviews. We compare hotels on TripAdvisor.com before booking them and read reviews on Amazon.com before ordering products. We "like" or "dislike" Facebook pages and give thumbs up or thumbs down to videos on YouTube. We even rate physicians’ comments on medical question-and-answer sites such as HealthTap.com.

But how much do all of these online ratings really matter? A 2012 Nielsen report that surveyed more than 28,000 Internet users in 56 countries found that online consumer reviews are the second-most-trusted source of brand information, following only recommendations from family and friends. In other words, we trust online reviews and use them to make our own decisions.

The same is true when it comes to shopping for a doctor. According to an Internet-based survey of 2,137 adults published in the February issue of JAMA, 59% of respondents said that online doctor ratings were either "somewhat important" or "very important" when choosing a physician (2014;11:734-5).

Similarly, the "2013 Industry View Report" by Software Advice found that 62% of respondents said they read online reviews when seeking a new doctor. Although HealthGrades.com was the most commonly used site, Yelp.com was the most trusted. Forty-four percent of those respondents considered Yelp the most trustworthy review site followed by Health Grades (31%), Vitals.com (17%), and ZocDoc.com (7%).

Whether or not we trust Yelp and other online review sites, our patients do. In the JAMA survey, 35% of respondents said that they selected a physician based on good ratings, while 37% said that they avoided a physician with negative reviews. The 2013 Industry View Report also found that 45% of respondents ranked "quality of care" as the most important type of information sought about a doctor. And since many patients equate service with quality, reviews that focus on service matter.

This isn’t an entirely bad thing. If we really listen to what patients are saying, their comments can help us to improve service and communication. And, in some instances, it can lead to stronger doctor-patient relationships. Like many other industries, health care is moving toward transparency, and doctor rating sites are a key component of that.

Dr. Jeffrey Benabio is a partner physician in the department of dermatology of the Southern California Permanente Group in San Diego and a volunteer clinical assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego. He has published numerous scientific articles and is a member and fellow of the American Academy of Dermatology, and a member of the Telemedicine Association and the American Medical Association, among others. He is board certified in dermatology as well as medicine and surgery in the state of California. Dr. Benabio has a special interest in the uses of social media for education and building dermatology practice. He is the founder of The Derm Blog, an educational website that has had more than 2 million unique visitors. Dr. Benabio is also a founding member and the skin care expert for Livestrong.com, a health and wellness website of Lance Armstrong’s the Livestrong Foundation. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter.

The last time I gave the talk, "Help! I’ve Been Yelped!" to physicians, there was a full house, a sometimes defiant, sometimes incredulous but always engaged full house. Most physicians don’t like Yelp and other online doctor rating sites because of the potential for negative reviews.

In past columns, I’ve written about these sites and how to respond to negative reviews and comments. Now, I’m going to share data on the use of online reviews and why they are important.

We live in a digital world that values reviews. We compare hotels on TripAdvisor.com before booking them and read reviews on Amazon.com before ordering products. We "like" or "dislike" Facebook pages and give thumbs up or thumbs down to videos on YouTube. We even rate physicians’ comments on medical question-and-answer sites such as HealthTap.com.

But how much do all of these online ratings really matter? A 2012 Nielsen report that surveyed more than 28,000 Internet users in 56 countries found that online consumer reviews are the second-most-trusted source of brand information, following only recommendations from family and friends. In other words, we trust online reviews and use them to make our own decisions.

The same is true when it comes to shopping for a doctor. According to an Internet-based survey of 2,137 adults published in the February issue of JAMA, 59% of respondents said that online doctor ratings were either "somewhat important" or "very important" when choosing a physician (2014;11:734-5).

Similarly, the "2013 Industry View Report" by Software Advice found that 62% of respondents said they read online reviews when seeking a new doctor. Although HealthGrades.com was the most commonly used site, Yelp.com was the most trusted. Forty-four percent of those respondents considered Yelp the most trustworthy review site followed by Health Grades (31%), Vitals.com (17%), and ZocDoc.com (7%).

Whether or not we trust Yelp and other online review sites, our patients do. In the JAMA survey, 35% of respondents said that they selected a physician based on good ratings, while 37% said that they avoided a physician with negative reviews. The 2013 Industry View Report also found that 45% of respondents ranked "quality of care" as the most important type of information sought about a doctor. And since many patients equate service with quality, reviews that focus on service matter.

This isn’t an entirely bad thing. If we really listen to what patients are saying, their comments can help us to improve service and communication. And, in some instances, it can lead to stronger doctor-patient relationships. Like many other industries, health care is moving toward transparency, and doctor rating sites are a key component of that.

Dr. Jeffrey Benabio is a partner physician in the department of dermatology of the Southern California Permanente Group in San Diego and a volunteer clinical assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego. He has published numerous scientific articles and is a member and fellow of the American Academy of Dermatology, and a member of the Telemedicine Association and the American Medical Association, among others. He is board certified in dermatology as well as medicine and surgery in the state of California. Dr. Benabio has a special interest in the uses of social media for education and building dermatology practice. He is the founder of The Derm Blog, an educational website that has had more than 2 million unique visitors. Dr. Benabio is also a founding member and the skin care expert for Livestrong.com, a health and wellness website of Lance Armstrong’s the Livestrong Foundation. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter.

Cervical cancer screening

Numerous screening methods for cervical cancer have been proposed internationally by various professional societies, including Pap cytology alone, cytology with human papillomavirus testing as triage (HPV testing for atypical squamous cells of unknown significance [ASCUS] on cytology), cytology with HPV cotesting (cytology and HPV testing obtained together), HPV testing alone, or HPV testing followed by Pap cytology triage (cytology in patients who are positive for high-risk oncogenic subtypes of HPV). Recommendations for use of cervical cytology and HPV testing continue to vary among professional societies, with variable adoption of these guidelines by providers as well. (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013;45:175-81).

In 2012, updated cervical cancer screening recommendations were published by ASCCP (the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) (Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012;137:516-42); the USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force ); and ACOG (the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1409-20).

These most recent guidelines show a greater degree of harmony across these governing bodies than did prior guidelines. All three professional societies recommend initiating screening at age 21 years and ceasing screening at age 65 years with an adequate screening history. All groups recommend against HPV cotesting in women under 30 years of age; however, after age 30 years, ASCCP and ACOG recommend HPV cotesting every 5 years as the preferred method of cervical cancer screening, while USPSTF suggests this only as an "option." Primary HPV testing without concurrent cytology for cervical cancer screening is not currently recommended by ASCCP and USPSTF and is not addressed by ACOG.

Efficacy of screening modalities

The rationale behind these screening recommendations depends on the efficacy of both cervical cytology and HPV testing to identify preinvasive cases or invasive cervical cancer. Multiple studies have addressed the sensitivity and specificity of cytology in cervical cancer screening. Overall, the sensitivity of Pap cytology is low at approximately 51%, while specificity is high at 96%-98% (Ann. Intern. Med. 2000;132:810-9; Vaccine 2008;26 Suppl. 10:K29-41). Since the initiation of cervical cytology for cancer screening, serial annual screening has compensated for the overall poor sensitivity of the test. Two consecutive annual Pap tests can increase overall sensitivity for detection of cervical cancer to 76%, and three consecutive annual Pap tests can increase overall sensitivity to 88%.

Unlike Pap cytology, HPV testing has a high sensitivity, ranging from 81%-97% in detection of cervical cancer (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1579-88). As a result, HPV testing does not rely on serial testing for accuracy and has a high negative predictive value, making negative results very reassuring. However, HPV testing has a slightly lower specificity of 94%, which results in a higher number of false positives. Furthermore, many patients who screen positive for high-risk HPV subtypes may have transient HPV infections, which are not clinically significant, and may not cause invasive cervical cancer.

Several randomized studies have compared Pap cytology to HPV testing for use in cervical cancer screening. A Canadian study randomized more than 10,000 women to either Pap cytology or HPV testing to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 or higher grade cervical lesions (Int. J. Cancer. 2006;119:615-23). Findings showed a sensitivity of 55.4% for Pap cytology vs. 94.6% for HPV testing. Pap cytology had a specificity of 96.8% while HPV testing had a specificity of 94.1%. The negative predictive value of HPV testing was 100%.

Swedescreen, a Swedish study of more 12,000 women (J. Med. Virol. 2007;79:1169-75), and POBASCAM, a large Dutch study of more than 18,000 women (Lancet 2007;370:1764-72), both compared HPV testing combined with Pap cytology (cotesting) to cytology alone. Both studies found that patients screened with Pap cytology alone had more CIN2 or greater lesions in follow-up than did patients screened with cytology in combination with HPV testing (relative risk, 0.53-0.58 for CIN 2+ and RR 0.45-0.53 for CIN 3+) (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009;101:88-99).

Because of the higher sensitivity of HPV testing compared with Pap cytology, some have advocated the use of HPV testing as primary screening with cytology triage rather than the reverse (cytology with HPV triage), which is more commonly used today. A Finnish study showed that primary HPV testing with cytology performed only in patients who screened positive for high risk oncogenic subtypes of HPV was more sensitive than was conventional cytology in identifying cervical dysplasia and cancer. Additionally, in women over age 35 years, HPV testing combined with Pap cytology triage was more specific than cytology alone, and decreased colposcopy referrals and follow-up tests, making this screening option cost effective (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1612-23). Nowhere else in medicine is a more specific test used prior to a more sensitive test when screening for disease; the screening test is typically the more sensitive, while the confirmatory test is the more specific.

HPV vaccination and effects on screening

Currently, given that the HPV vaccines available do not protect women from all oncogenic HPV types, the ASCCP, USPSTF, and ACOG all recommend screening vaccinated women in an identical fashion to unvaccinated women. Increasing vaccination rates will likely have an impact on the efficacy of the various cervical cancer screening modalities. Vaccination will result in a reduction in the prevalence of cytologic abnormalities. As disease prevalence decreases and screening intervals increase based on current guidelines, the positive predictive value of Pap cytology also will decline, resulting in more false-positive diagnoses and possibly unnecessary procedures and patient stress (Vaccine 2013;31:5495-9). As prevalence of disease decreases, Pap cytology has the potential to become less reliable. While the positive predictive value of HPV testing also declines with decreasing disease prevalence, HPV testing is more reproducible than interpretation of Pap cytology, so the extent of increasing false-positive results may be less (Vaccine 2006;24 Suppl 3:S3/171-7).

Future directions

HPV testing as primary screening for cervical cancer is not currently recommended. However, in the post-HPV vaccination era, this may become an increasingly reasonable approach, particularly in conjunction with Pap cytology used to triage patients who test positive for high-risk HPV subtypes. HPV testing has much greater sensitivity than Pap cytology does and can better identify patients who are likely to have a cytologic abnormality. In this group of patients with greater disease prevalence, the slightly higher specificity of Pap cytology can then be used to identify precancerous lesions and guide treatment. Once this group of patients with higher lesion prevalence than the general population has been identified through HPV testing, Pap cytology can then be used and will perform better than in a lower prevalence population.

The importance of Pap cytology and HPV testing in cervical cancer screening continues to evolve, particularly in the current era of HPV vaccination. The combination of HPV testing followed by Pap cytology has potential for becoming a highly effective screening strategy; however, the optimal administration of these tests is yet to be determined. As current screening modalities improve and new technologies emerge, ongoing work is needed to identify the most effective screening method for cervical cancer.

Dr. Wysham is currently a fellow in the department of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Kim is the department of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Numerous screening methods for cervical cancer have been proposed internationally by various professional societies, including Pap cytology alone, cytology with human papillomavirus testing as triage (HPV testing for atypical squamous cells of unknown significance [ASCUS] on cytology), cytology with HPV cotesting (cytology and HPV testing obtained together), HPV testing alone, or HPV testing followed by Pap cytology triage (cytology in patients who are positive for high-risk oncogenic subtypes of HPV). Recommendations for use of cervical cytology and HPV testing continue to vary among professional societies, with variable adoption of these guidelines by providers as well. (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013;45:175-81).

In 2012, updated cervical cancer screening recommendations were published by ASCCP (the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) (Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012;137:516-42); the USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force ); and ACOG (the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1409-20).

These most recent guidelines show a greater degree of harmony across these governing bodies than did prior guidelines. All three professional societies recommend initiating screening at age 21 years and ceasing screening at age 65 years with an adequate screening history. All groups recommend against HPV cotesting in women under 30 years of age; however, after age 30 years, ASCCP and ACOG recommend HPV cotesting every 5 years as the preferred method of cervical cancer screening, while USPSTF suggests this only as an "option." Primary HPV testing without concurrent cytology for cervical cancer screening is not currently recommended by ASCCP and USPSTF and is not addressed by ACOG.

Efficacy of screening modalities

The rationale behind these screening recommendations depends on the efficacy of both cervical cytology and HPV testing to identify preinvasive cases or invasive cervical cancer. Multiple studies have addressed the sensitivity and specificity of cytology in cervical cancer screening. Overall, the sensitivity of Pap cytology is low at approximately 51%, while specificity is high at 96%-98% (Ann. Intern. Med. 2000;132:810-9; Vaccine 2008;26 Suppl. 10:K29-41). Since the initiation of cervical cytology for cancer screening, serial annual screening has compensated for the overall poor sensitivity of the test. Two consecutive annual Pap tests can increase overall sensitivity for detection of cervical cancer to 76%, and three consecutive annual Pap tests can increase overall sensitivity to 88%.

Unlike Pap cytology, HPV testing has a high sensitivity, ranging from 81%-97% in detection of cervical cancer (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1579-88). As a result, HPV testing does not rely on serial testing for accuracy and has a high negative predictive value, making negative results very reassuring. However, HPV testing has a slightly lower specificity of 94%, which results in a higher number of false positives. Furthermore, many patients who screen positive for high-risk HPV subtypes may have transient HPV infections, which are not clinically significant, and may not cause invasive cervical cancer.

Several randomized studies have compared Pap cytology to HPV testing for use in cervical cancer screening. A Canadian study randomized more than 10,000 women to either Pap cytology or HPV testing to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 or higher grade cervical lesions (Int. J. Cancer. 2006;119:615-23). Findings showed a sensitivity of 55.4% for Pap cytology vs. 94.6% for HPV testing. Pap cytology had a specificity of 96.8% while HPV testing had a specificity of 94.1%. The negative predictive value of HPV testing was 100%.

Swedescreen, a Swedish study of more 12,000 women (J. Med. Virol. 2007;79:1169-75), and POBASCAM, a large Dutch study of more than 18,000 women (Lancet 2007;370:1764-72), both compared HPV testing combined with Pap cytology (cotesting) to cytology alone. Both studies found that patients screened with Pap cytology alone had more CIN2 or greater lesions in follow-up than did patients screened with cytology in combination with HPV testing (relative risk, 0.53-0.58 for CIN 2+ and RR 0.45-0.53 for CIN 3+) (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009;101:88-99).

Because of the higher sensitivity of HPV testing compared with Pap cytology, some have advocated the use of HPV testing as primary screening with cytology triage rather than the reverse (cytology with HPV triage), which is more commonly used today. A Finnish study showed that primary HPV testing with cytology performed only in patients who screened positive for high risk oncogenic subtypes of HPV was more sensitive than was conventional cytology in identifying cervical dysplasia and cancer. Additionally, in women over age 35 years, HPV testing combined with Pap cytology triage was more specific than cytology alone, and decreased colposcopy referrals and follow-up tests, making this screening option cost effective (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1612-23). Nowhere else in medicine is a more specific test used prior to a more sensitive test when screening for disease; the screening test is typically the more sensitive, while the confirmatory test is the more specific.

HPV vaccination and effects on screening

Currently, given that the HPV vaccines available do not protect women from all oncogenic HPV types, the ASCCP, USPSTF, and ACOG all recommend screening vaccinated women in an identical fashion to unvaccinated women. Increasing vaccination rates will likely have an impact on the efficacy of the various cervical cancer screening modalities. Vaccination will result in a reduction in the prevalence of cytologic abnormalities. As disease prevalence decreases and screening intervals increase based on current guidelines, the positive predictive value of Pap cytology also will decline, resulting in more false-positive diagnoses and possibly unnecessary procedures and patient stress (Vaccine 2013;31:5495-9). As prevalence of disease decreases, Pap cytology has the potential to become less reliable. While the positive predictive value of HPV testing also declines with decreasing disease prevalence, HPV testing is more reproducible than interpretation of Pap cytology, so the extent of increasing false-positive results may be less (Vaccine 2006;24 Suppl 3:S3/171-7).

Future directions

HPV testing as primary screening for cervical cancer is not currently recommended. However, in the post-HPV vaccination era, this may become an increasingly reasonable approach, particularly in conjunction with Pap cytology used to triage patients who test positive for high-risk HPV subtypes. HPV testing has much greater sensitivity than Pap cytology does and can better identify patients who are likely to have a cytologic abnormality. In this group of patients with greater disease prevalence, the slightly higher specificity of Pap cytology can then be used to identify precancerous lesions and guide treatment. Once this group of patients with higher lesion prevalence than the general population has been identified through HPV testing, Pap cytology can then be used and will perform better than in a lower prevalence population.

The importance of Pap cytology and HPV testing in cervical cancer screening continues to evolve, particularly in the current era of HPV vaccination. The combination of HPV testing followed by Pap cytology has potential for becoming a highly effective screening strategy; however, the optimal administration of these tests is yet to be determined. As current screening modalities improve and new technologies emerge, ongoing work is needed to identify the most effective screening method for cervical cancer.

Dr. Wysham is currently a fellow in the department of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Kim is the department of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Numerous screening methods for cervical cancer have been proposed internationally by various professional societies, including Pap cytology alone, cytology with human papillomavirus testing as triage (HPV testing for atypical squamous cells of unknown significance [ASCUS] on cytology), cytology with HPV cotesting (cytology and HPV testing obtained together), HPV testing alone, or HPV testing followed by Pap cytology triage (cytology in patients who are positive for high-risk oncogenic subtypes of HPV). Recommendations for use of cervical cytology and HPV testing continue to vary among professional societies, with variable adoption of these guidelines by providers as well. (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013;45:175-81).

In 2012, updated cervical cancer screening recommendations were published by ASCCP (the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) (Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012;137:516-42); the USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force ); and ACOG (the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) (Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;114:1409-20).

These most recent guidelines show a greater degree of harmony across these governing bodies than did prior guidelines. All three professional societies recommend initiating screening at age 21 years and ceasing screening at age 65 years with an adequate screening history. All groups recommend against HPV cotesting in women under 30 years of age; however, after age 30 years, ASCCP and ACOG recommend HPV cotesting every 5 years as the preferred method of cervical cancer screening, while USPSTF suggests this only as an "option." Primary HPV testing without concurrent cytology for cervical cancer screening is not currently recommended by ASCCP and USPSTF and is not addressed by ACOG.

Efficacy of screening modalities

The rationale behind these screening recommendations depends on the efficacy of both cervical cytology and HPV testing to identify preinvasive cases or invasive cervical cancer. Multiple studies have addressed the sensitivity and specificity of cytology in cervical cancer screening. Overall, the sensitivity of Pap cytology is low at approximately 51%, while specificity is high at 96%-98% (Ann. Intern. Med. 2000;132:810-9; Vaccine 2008;26 Suppl. 10:K29-41). Since the initiation of cervical cytology for cancer screening, serial annual screening has compensated for the overall poor sensitivity of the test. Two consecutive annual Pap tests can increase overall sensitivity for detection of cervical cancer to 76%, and three consecutive annual Pap tests can increase overall sensitivity to 88%.

Unlike Pap cytology, HPV testing has a high sensitivity, ranging from 81%-97% in detection of cervical cancer (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1579-88). As a result, HPV testing does not rely on serial testing for accuracy and has a high negative predictive value, making negative results very reassuring. However, HPV testing has a slightly lower specificity of 94%, which results in a higher number of false positives. Furthermore, many patients who screen positive for high-risk HPV subtypes may have transient HPV infections, which are not clinically significant, and may not cause invasive cervical cancer.

Several randomized studies have compared Pap cytology to HPV testing for use in cervical cancer screening. A Canadian study randomized more than 10,000 women to either Pap cytology or HPV testing to detect cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 or higher grade cervical lesions (Int. J. Cancer. 2006;119:615-23). Findings showed a sensitivity of 55.4% for Pap cytology vs. 94.6% for HPV testing. Pap cytology had a specificity of 96.8% while HPV testing had a specificity of 94.1%. The negative predictive value of HPV testing was 100%.

Swedescreen, a Swedish study of more 12,000 women (J. Med. Virol. 2007;79:1169-75), and POBASCAM, a large Dutch study of more than 18,000 women (Lancet 2007;370:1764-72), both compared HPV testing combined with Pap cytology (cotesting) to cytology alone. Both studies found that patients screened with Pap cytology alone had more CIN2 or greater lesions in follow-up than did patients screened with cytology in combination with HPV testing (relative risk, 0.53-0.58 for CIN 2+ and RR 0.45-0.53 for CIN 3+) (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009;101:88-99).

Because of the higher sensitivity of HPV testing compared with Pap cytology, some have advocated the use of HPV testing as primary screening with cytology triage rather than the reverse (cytology with HPV triage), which is more commonly used today. A Finnish study showed that primary HPV testing with cytology performed only in patients who screened positive for high risk oncogenic subtypes of HPV was more sensitive than was conventional cytology in identifying cervical dysplasia and cancer. Additionally, in women over age 35 years, HPV testing combined with Pap cytology triage was more specific than cytology alone, and decreased colposcopy referrals and follow-up tests, making this screening option cost effective (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1612-23). Nowhere else in medicine is a more specific test used prior to a more sensitive test when screening for disease; the screening test is typically the more sensitive, while the confirmatory test is the more specific.

HPV vaccination and effects on screening

Currently, given that the HPV vaccines available do not protect women from all oncogenic HPV types, the ASCCP, USPSTF, and ACOG all recommend screening vaccinated women in an identical fashion to unvaccinated women. Increasing vaccination rates will likely have an impact on the efficacy of the various cervical cancer screening modalities. Vaccination will result in a reduction in the prevalence of cytologic abnormalities. As disease prevalence decreases and screening intervals increase based on current guidelines, the positive predictive value of Pap cytology also will decline, resulting in more false-positive diagnoses and possibly unnecessary procedures and patient stress (Vaccine 2013;31:5495-9). As prevalence of disease decreases, Pap cytology has the potential to become less reliable. While the positive predictive value of HPV testing also declines with decreasing disease prevalence, HPV testing is more reproducible than interpretation of Pap cytology, so the extent of increasing false-positive results may be less (Vaccine 2006;24 Suppl 3:S3/171-7).

Future directions

HPV testing as primary screening for cervical cancer is not currently recommended. However, in the post-HPV vaccination era, this may become an increasingly reasonable approach, particularly in conjunction with Pap cytology used to triage patients who test positive for high-risk HPV subtypes. HPV testing has much greater sensitivity than Pap cytology does and can better identify patients who are likely to have a cytologic abnormality. In this group of patients with greater disease prevalence, the slightly higher specificity of Pap cytology can then be used to identify precancerous lesions and guide treatment. Once this group of patients with higher lesion prevalence than the general population has been identified through HPV testing, Pap cytology can then be used and will perform better than in a lower prevalence population.

The importance of Pap cytology and HPV testing in cervical cancer screening continues to evolve, particularly in the current era of HPV vaccination. The combination of HPV testing followed by Pap cytology has potential for becoming a highly effective screening strategy; however, the optimal administration of these tests is yet to be determined. As current screening modalities improve and new technologies emerge, ongoing work is needed to identify the most effective screening method for cervical cancer.

Dr. Wysham is currently a fellow in the department of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Kim is the department of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Preventing Weight Loss in Patients With Dementia

The link between dementia and weight loss has been established: Weight loss is associated with even mild dementia, increasing with advancing disease severity and duration. But with a large multicountry study, researchers from the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, King’s College London and Newcastle University, both in the United Kingdom, and Universidad Nacional Pedro Henriquez Ureña in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, add new information about the universality of the association.

The researchers surveyed 16,538 older adults, asking them or a caregiver whether the patient had lost ≥ 10 pounds in the previous 3 months. The prevalence of weight loss ranged from 2% in China to 26% in the Dominican Republic and was lowest for participants with no dementia and highest in those with a Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Severity of two-thirds in all countries. The association increased and strengthened linearly through stages of dementia severity in all the study countries.

Weight loss in people with dementia can lead to further morbidity, worse prognosis, and death, the researchers note. They call for more studies, but in the meantime, they emphasize that treating and preventing weight loss is critical, particularly for institutionalized dementia patients.

One intervention that could help is giving patients nutritionally complete oral supplements, say researchers from The Royal Berkshire Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Reading, both in the United Kingdom. They reviewed 12 studies involving 1,824 patients. Most interventions, which ranged from 3 weeks to 1 year, were compared with a normal diet and care.

Two findings had to do with how weight loss is measured in older people. Skin-fold thickness and arm muscle circumference are not affected by supplement use, the researchers found. They add that those anthropometric measurements have a low level of reproducibility and are not an accurate method for obtaining evidence of changes in body composition (mid-arm muscle circumference is calculated from the skin-fold measurements). Further, measuring by body mass index (BMI) is less accurate in older patients, they note, when determining fat mass and subsequent nutritional status due to changes in height and age-related redistribution of fat mass.

However, the studies were short enough to allow BMI and weight measurements to detect the influence of the supplements. And the conclusion was that the nutritional supplement drinks had positive effects on weight gain and BMI. Overall, the consumption was “fairly good”; however, consumption was lowest in one of the longest studies. That might have been due to changes in staff behavior—increased vigilance and verbal prompting, common in the shorter studies, may have dropped off in longer studies.

Supplement use was significantly associated with improved overall energy intake and a small but statistically significant change in weight and BMI (P < .0001). However, where the control was a macro- or micronutrient supplement, findings were less positive. That may indicate that comparisons of nutritional supplements to vitamin/mineral tablets and high protein-calorie shots needs more research, the researchers conclude.

Sources

Albanese E, Taylor C, Siervo M, Stewart R, Prince MJ, Acosta D. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2013;9(6):649-656.

doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.014.

Allen VJ, Methven L, Gosney MA. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(6):950-957.

doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.03.015.

The link between dementia and weight loss has been established: Weight loss is associated with even mild dementia, increasing with advancing disease severity and duration. But with a large multicountry study, researchers from the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, King’s College London and Newcastle University, both in the United Kingdom, and Universidad Nacional Pedro Henriquez Ureña in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, add new information about the universality of the association.

The researchers surveyed 16,538 older adults, asking them or a caregiver whether the patient had lost ≥ 10 pounds in the previous 3 months. The prevalence of weight loss ranged from 2% in China to 26% in the Dominican Republic and was lowest for participants with no dementia and highest in those with a Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Severity of two-thirds in all countries. The association increased and strengthened linearly through stages of dementia severity in all the study countries.

Weight loss in people with dementia can lead to further morbidity, worse prognosis, and death, the researchers note. They call for more studies, but in the meantime, they emphasize that treating and preventing weight loss is critical, particularly for institutionalized dementia patients.

One intervention that could help is giving patients nutritionally complete oral supplements, say researchers from The Royal Berkshire Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Reading, both in the United Kingdom. They reviewed 12 studies involving 1,824 patients. Most interventions, which ranged from 3 weeks to 1 year, were compared with a normal diet and care.

Two findings had to do with how weight loss is measured in older people. Skin-fold thickness and arm muscle circumference are not affected by supplement use, the researchers found. They add that those anthropometric measurements have a low level of reproducibility and are not an accurate method for obtaining evidence of changes in body composition (mid-arm muscle circumference is calculated from the skin-fold measurements). Further, measuring by body mass index (BMI) is less accurate in older patients, they note, when determining fat mass and subsequent nutritional status due to changes in height and age-related redistribution of fat mass.

However, the studies were short enough to allow BMI and weight measurements to detect the influence of the supplements. And the conclusion was that the nutritional supplement drinks had positive effects on weight gain and BMI. Overall, the consumption was “fairly good”; however, consumption was lowest in one of the longest studies. That might have been due to changes in staff behavior—increased vigilance and verbal prompting, common in the shorter studies, may have dropped off in longer studies.

Supplement use was significantly associated with improved overall energy intake and a small but statistically significant change in weight and BMI (P < .0001). However, where the control was a macro- or micronutrient supplement, findings were less positive. That may indicate that comparisons of nutritional supplements to vitamin/mineral tablets and high protein-calorie shots needs more research, the researchers conclude.

Sources

Albanese E, Taylor C, Siervo M, Stewart R, Prince MJ, Acosta D. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2013;9(6):649-656.

doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.014.

Allen VJ, Methven L, Gosney MA. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(6):950-957.

doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.03.015.

The link between dementia and weight loss has been established: Weight loss is associated with even mild dementia, increasing with advancing disease severity and duration. But with a large multicountry study, researchers from the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, King’s College London and Newcastle University, both in the United Kingdom, and Universidad Nacional Pedro Henriquez Ureña in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, add new information about the universality of the association.

The researchers surveyed 16,538 older adults, asking them or a caregiver whether the patient had lost ≥ 10 pounds in the previous 3 months. The prevalence of weight loss ranged from 2% in China to 26% in the Dominican Republic and was lowest for participants with no dementia and highest in those with a Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Severity of two-thirds in all countries. The association increased and strengthened linearly through stages of dementia severity in all the study countries.

Weight loss in people with dementia can lead to further morbidity, worse prognosis, and death, the researchers note. They call for more studies, but in the meantime, they emphasize that treating and preventing weight loss is critical, particularly for institutionalized dementia patients.

One intervention that could help is giving patients nutritionally complete oral supplements, say researchers from The Royal Berkshire Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Reading, both in the United Kingdom. They reviewed 12 studies involving 1,824 patients. Most interventions, which ranged from 3 weeks to 1 year, were compared with a normal diet and care.

Two findings had to do with how weight loss is measured in older people. Skin-fold thickness and arm muscle circumference are not affected by supplement use, the researchers found. They add that those anthropometric measurements have a low level of reproducibility and are not an accurate method for obtaining evidence of changes in body composition (mid-arm muscle circumference is calculated from the skin-fold measurements). Further, measuring by body mass index (BMI) is less accurate in older patients, they note, when determining fat mass and subsequent nutritional status due to changes in height and age-related redistribution of fat mass.

However, the studies were short enough to allow BMI and weight measurements to detect the influence of the supplements. And the conclusion was that the nutritional supplement drinks had positive effects on weight gain and BMI. Overall, the consumption was “fairly good”; however, consumption was lowest in one of the longest studies. That might have been due to changes in staff behavior—increased vigilance and verbal prompting, common in the shorter studies, may have dropped off in longer studies.

Supplement use was significantly associated with improved overall energy intake and a small but statistically significant change in weight and BMI (P < .0001). However, where the control was a macro- or micronutrient supplement, findings were less positive. That may indicate that comparisons of nutritional supplements to vitamin/mineral tablets and high protein-calorie shots needs more research, the researchers conclude.

Sources

Albanese E, Taylor C, Siervo M, Stewart R, Prince MJ, Acosta D. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2013;9(6):649-656.

doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.014.

Allen VJ, Methven L, Gosney MA. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(6):950-957.

doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.03.015.

FDA approves IV formulation of antifungal agent

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved an intravenous formulation of posaconazole (Noxafil), which is expected to be available at wholesalers in mid-April.

The antifungal agent is already available as delayed-release tablets and in an oral suspension formulation.

In any formulation, posaconazole is indicated for prophylaxis of invasive Aspergillus and Candida infections in immunocompromised patients who are at high risk of developing these infections.

This includes patients who have developed graft-vs-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplant and patients with hematologic malignancies who have prolonged neutropenia resulting from chemotherapy.

Posaconazole injection is indicated for use in patients 18 years of age and older. The delayed-release tablets and oral suspension are indicated for patients 13 years of age and older.

Posaconazole injection is administered with a loading dose of 300 mg (one 300 mg vial) twice a day on the first day of therapy, then 300 mg once a day thereafter. It is given through a central venous line by slow intravenous infusion over approximately 90 minutes.

Once combined with a mixture of intravenous solution (150 mL of 5% dextrose in water or sodium chloride 0.9%), posaconazole injection should be administered immediately. If not used immediately, the solution can be stored up to 24 hours if refrigerated at 2-8 degrees C (36-46 degrees F).

Co-administration of drugs that can decrease the plasma concentration of posaconazole should be avoided unless the benefit outweighs the risk. If such drugs are necessary, patients should be monitored closely for breakthrough fungal infections.

In clinical trials, the adverse reactions reported for posaconazole injection were generally similar to those reported in trials of posaconazole oral suspension. The most frequently reported adverse reactions with an onset during the posaconazole intravenous phase of dosing 300 mg once-daily therapy were diarrhea (32%), hypokalemia (22%), fever (21%), and nausea (19%).

Patients who are allergic to posaconazole or other azole antifungal medicines should not receive posaconazole. The drug should not be given along with sirolimus, pimozide, quinidine, atorvastatin, lovastatin, simvastatin, or ergot alkaloids.

Drugs such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus require dose adjustments and frequent blood monitoring when administered with posaconazole. Serious side effects, including nephrotoxicity, leukoencephalopathy, and death, have been reported in patients with increased cyclosporine or tacrolimus blood levels.

Healthcare professionals should use caution when administering posaconazole to patients at risk of developing an irregular heart rhythm, as the drug has been shown to prolong the QT interval, and cases of potentially fatal irregular heart rhythm (torsades de pointes) have been reported in patients taking posaconazole.

For more details, see the complete prescribing information. Posaconazole is marketed as Noxafil by Merck. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved an intravenous formulation of posaconazole (Noxafil), which is expected to be available at wholesalers in mid-April.

The antifungal agent is already available as delayed-release tablets and in an oral suspension formulation.

In any formulation, posaconazole is indicated for prophylaxis of invasive Aspergillus and Candida infections in immunocompromised patients who are at high risk of developing these infections.

This includes patients who have developed graft-vs-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplant and patients with hematologic malignancies who have prolonged neutropenia resulting from chemotherapy.

Posaconazole injection is indicated for use in patients 18 years of age and older. The delayed-release tablets and oral suspension are indicated for patients 13 years of age and older.

Posaconazole injection is administered with a loading dose of 300 mg (one 300 mg vial) twice a day on the first day of therapy, then 300 mg once a day thereafter. It is given through a central venous line by slow intravenous infusion over approximately 90 minutes.

Once combined with a mixture of intravenous solution (150 mL of 5% dextrose in water or sodium chloride 0.9%), posaconazole injection should be administered immediately. If not used immediately, the solution can be stored up to 24 hours if refrigerated at 2-8 degrees C (36-46 degrees F).

Co-administration of drugs that can decrease the plasma concentration of posaconazole should be avoided unless the benefit outweighs the risk. If such drugs are necessary, patients should be monitored closely for breakthrough fungal infections.

In clinical trials, the adverse reactions reported for posaconazole injection were generally similar to those reported in trials of posaconazole oral suspension. The most frequently reported adverse reactions with an onset during the posaconazole intravenous phase of dosing 300 mg once-daily therapy were diarrhea (32%), hypokalemia (22%), fever (21%), and nausea (19%).

Patients who are allergic to posaconazole or other azole antifungal medicines should not receive posaconazole. The drug should not be given along with sirolimus, pimozide, quinidine, atorvastatin, lovastatin, simvastatin, or ergot alkaloids.

Drugs such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus require dose adjustments and frequent blood monitoring when administered with posaconazole. Serious side effects, including nephrotoxicity, leukoencephalopathy, and death, have been reported in patients with increased cyclosporine or tacrolimus blood levels.

Healthcare professionals should use caution when administering posaconazole to patients at risk of developing an irregular heart rhythm, as the drug has been shown to prolong the QT interval, and cases of potentially fatal irregular heart rhythm (torsades de pointes) have been reported in patients taking posaconazole.

For more details, see the complete prescribing information. Posaconazole is marketed as Noxafil by Merck. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved an intravenous formulation of posaconazole (Noxafil), which is expected to be available at wholesalers in mid-April.

The antifungal agent is already available as delayed-release tablets and in an oral suspension formulation.

In any formulation, posaconazole is indicated for prophylaxis of invasive Aspergillus and Candida infections in immunocompromised patients who are at high risk of developing these infections.

This includes patients who have developed graft-vs-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplant and patients with hematologic malignancies who have prolonged neutropenia resulting from chemotherapy.

Posaconazole injection is indicated for use in patients 18 years of age and older. The delayed-release tablets and oral suspension are indicated for patients 13 years of age and older.

Posaconazole injection is administered with a loading dose of 300 mg (one 300 mg vial) twice a day on the first day of therapy, then 300 mg once a day thereafter. It is given through a central venous line by slow intravenous infusion over approximately 90 minutes.

Once combined with a mixture of intravenous solution (150 mL of 5% dextrose in water or sodium chloride 0.9%), posaconazole injection should be administered immediately. If not used immediately, the solution can be stored up to 24 hours if refrigerated at 2-8 degrees C (36-46 degrees F).

Co-administration of drugs that can decrease the plasma concentration of posaconazole should be avoided unless the benefit outweighs the risk. If such drugs are necessary, patients should be monitored closely for breakthrough fungal infections.

In clinical trials, the adverse reactions reported for posaconazole injection were generally similar to those reported in trials of posaconazole oral suspension. The most frequently reported adverse reactions with an onset during the posaconazole intravenous phase of dosing 300 mg once-daily therapy were diarrhea (32%), hypokalemia (22%), fever (21%), and nausea (19%).

Patients who are allergic to posaconazole or other azole antifungal medicines should not receive posaconazole. The drug should not be given along with sirolimus, pimozide, quinidine, atorvastatin, lovastatin, simvastatin, or ergot alkaloids.

Drugs such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus require dose adjustments and frequent blood monitoring when administered with posaconazole. Serious side effects, including nephrotoxicity, leukoencephalopathy, and death, have been reported in patients with increased cyclosporine or tacrolimus blood levels.

Healthcare professionals should use caution when administering posaconazole to patients at risk of developing an irregular heart rhythm, as the drug has been shown to prolong the QT interval, and cases of potentially fatal irregular heart rhythm (torsades de pointes) have been reported in patients taking posaconazole.

For more details, see the complete prescribing information. Posaconazole is marketed as Noxafil by Merck. ![]()

High cost of eculizumab needs explaining, NICE says

Credit: Bill Branson

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has asked the manufacturer of eculizumab (Soliris) to explain the high cost of the drug.

Research has suggested that eculizumab can be effective against atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), a rare disease that often proves difficult to treat.

So the National Health Service (NHS) has made eculizumab available for these patients on an interim basis, pending NICE appraisal.

However, an advisory committee for NICE has estimated that routine use of eculizumab would cost the NHS about £58 million in the first year, and costs would exceed £80 million in 5 years.

Therefore, in its draft guidance for eculizumab, the committee has asked the drug’s manufacturer, Alexion Pharma, to explain its costs.

“[The committee has] asked for clarification from the company on aspects of the manufacturing, research, and development costs of a medicinal product for the treatment of a very rare condition,” said Sir Andrew Dillon, Chief Executive at NICE.

“It has also asked NHS England for clarification on treatment costs for a highly specialized technology in the context of a highly specialized service. The information provided will be considered at the next meeting of the evaluation committee in April.”

The committee will also consider comments on its draft guidance at the meeting. The guidance is available for public comment until midday on March 25.

About aHUS

Estimated to affect more than 200 people in England, aHUS is a chronic condition that causes severe inflammation of blood vessels and thrombus formation in small blood vessels throughout the body.

Patients with aHUS can experience significant kidney impairment, thrombosis, heart failure, and brain injury. In about 70% of patients, aHUS is associated with an underlying genetic or acquired abnormality of proteins in the complement immune system.

Before eculizumab became available, plasma therapy (infusion and/or exchange) was the main treatment for aHUS. However, not all patients with aHUS respond to plasma therapy. And up to 40% of patients may die or progress to end-stage renal failure and require dialysis with the first clinical aHUS manifestation, despite the use of plasma therapy.

Some patients may be eligible for a kidney or combined kidney-liver transplantation. However, there is a high risk of organ rejection following recurrent disease.

Eculizumab in aHUS: Treatment and cost