User login

Online Question of the Month

New and Noteworthy Information—February 2014

Alcohol consumption may reduce the risk of developing multiple sclerosis (MS) and attenuate the effect of smoking, according to research published online ahead of print January 6 in JAMA Neurology. Scientists examined data from the Epidemiological Investigation of MS (EIMS), which included 745 cases and 1,761 controls, and from the Genes and Environment in MS (GEMS) study, which recruited 5,874 cases and 5,246 controls. In EIMS, women who reported high alcohol consumption (>112 g/week) had an odds ratio (OR) of 0.6 of developing MS, compared with nondrinking women. Men with high alcohol consumption (>168 g/week) in EIMS had an OR of 0.5, compared with nondrinking men. The OR for the comparison in GEMS was 0.7 for women and 0.7 for men. In both studies, the detrimental effect of smoking was more pronounced among nondrinkers.

A lentiviral vector-based gene therapy may be safe and improve motor behavior in patients with Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published online ahead of print January 10 in Lancet. In a phase I–II open-label trial, 15 patients received bilateral injections of gene therapy into the putamen and were followed up for 12 months. Participants received a low dose (1.9 × 107 transducing units [TU]), medium dose (4.0 × 107 TU), or a high dose (1 × 108 TU) of gene therapy. Patients reported 51 mild adverse events, three moderate adverse events, and no serious adverse events. The investigators noted a significant improvement in mean Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III motor scores off medication in all patients at six months, compared with baseline.

The FDA has approved a three-times-per-week formulation of Copaxone 40 mg/mL. The new formulation will enable a less-frequent dosing regimen to be administered subcutaneously to patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). The approval is based on data from the Phase III Glatiramer Acetate Low-Frequency Administration study of more than 1,400 patients. In the trial, investigators found that a 40-mg/mL dose of Copaxone administered subcutaneously three times per week significantly reduced relapse rates at 12 months and demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. In addition to the newly approved dose, daily Copaxone 20 mg/mL will continue to be available. The daily subcutaneous injection was approved in 1996. Both formulations are manufactured by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, which is headquartered in Jerusalem.

When administered with amitriptyline, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may result in greater reductions in days with headache and in migraine-related disability among young persons with chronic migraine, compared with headache education, according to research published December 25, 2013, in JAMA. In a randomized clinical trial, 135 children (ages 10 to 17) with chronic migraine and a Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Score (PedMIDAS) greater than 20 points were assigned to CBT plus amitriptyline or headache education plus amitriptyline. At the 20-week end point, days with headache were reduced by 11.5 for the CBT plus amitriptyline group, compared with 6.8 for the headache education plus amitriptyline group. The PedMIDAS decreased by 52.7 points for the CBT group and by 38.6 points for the headache education group.

Low levels of vitamin D early in the course of multiple sclerosis (MS) are a strong risk factor for long-term disease activity and progression in patients who were primarily treated with interferon beta-1b, according to a study published online January 20 in JAMA Neurology. Researchers compared early and delayed interferon beta-1b treatment in 468 patients with clinically isolated syndrome, measuring serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) at baseline and at six, 12, and 24 months. “A 50-nmol/L (20-ng/mL) increment in average serum 25(OH)D levels within the first 12 months predicted a 57% lower rate of new active lesions, 57% lower relapse rate, 25% lower yearly increase in T2 lesion volume, and 0.41% lower yearly loss in brain volume from months 12 to 60,” stated the study authors.

Excessive alcohol consumption in men was associated with faster cognitive decline, compared with light to moderate alcohol consumption, researchers reported online ahead of print January 15 in Neurology. The findings are based on data from 5,054 men and 2,099 women (mean age, 56) who had their alcohol consumption analyzed three times in the 10 years preceding the first cognitive assessment. In men, the investigators observed no differences in cognitive decline among alcohol abstainers, those who quit using alcohol, and light or moderate alcohol drinkers (<20 g/day). Alcohol consumption ≥36 g/day was associated with faster decline in all cognitive domains, compared with consumption between 0.1 and 19.9 g/day. In women, 10-year abstainers had a faster decline in the global cognitive score and executive function, compared with those drinking between 0.1 and 9.9 g/day of alcohol.

Vitamin D supplements may reduce pain in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome, according to a study in the February issue of Pain. The randomized controlled trial enrolled 30 women with fibromyalgia syndrome with serum calcifediol levels <32 ng/mL (80 nmol/L), in whom the goal was to achieve serum calcifediol levels between 32 and 48 ng/mL for 20 weeks with an oral cholecalciferol supplement. Re-evaluation was performed in both groups after an additional 24 weeks without cholecalciferol supplementation. The researchers observed a marked reduction in pain during the treatment period in those who received the supplement, and optimization of calcifediol levels had a positive effect on the perception of pain. “This economical therapy with a low side effect profile may well be considered in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome,” the researchers concluded.

A simple on-field blood test may help diagnose sports concussion. Relative and absolute increases in the astroglial protein, serum S100B, can accurately distinguish sports-related concussion from sports-related exertion, according to a study published online January 8 in PLOS One. Serum S100B was measured in 46 collegiate and semiprofessional contact sport athletes at preseason baseline, within three hours of injury, and at days 2, 3, and 7 post–sports-related concussion. Twenty-two athletes had a sports-related concussion, and 17 had S100B testing within three hours postinjury. The mean three-hour post–sports-related concussion S100B level was significantly higher than at preseason baseline, while the mean postexertion S100B level was not significantly different than that from the preseason baseline. S100B levels at postinjury days 2, 3, and 7 were significantly lower than at the three-hour level and were not different than at baseline.

Herpes zoster is an independent risk factor for vascular disease, particularly for stroke, transient ischemic attack, and myocardial infarction, in patients affected before age 40, researchers reported online ahead of print January 2 in Neurology. The findings are based on a retrospective cohort of 106,601 cases of herpes zoster and 213,202 controls from a general practice database in the United Kingdom. The investigators found that risk factors for vascular disease were significantly increased in patients with herpes zoster compared with controls. In addition, adjusted hazard ratios for TIA and myocardial infarction, but not stroke, were increased in all patients with herpes zoster. Stroke, TIA, and myocardial infarction were increased in cases in which herpes zoster occurred when the participants were younger than 40.

A study appearing January 22 online in Neurology found that a higher omega-3 index was correlated with larger total normal brain volume and hippocampal volume in postmenopausal women measured eight years later. Researchers assessed RBC eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and MRI brain volumes in 1,111 postmenopausal women from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. In fully adjusted models, a 1-SD greater RBC EPA + DHA (omega-3 index) level was correlated with 2.1 cm3 larger brain volume. “DHA was marginally correlated with total brain volume while EPA was less so,” reported the investigators. In fully adjusted models, a 1-SD greater omega-3 index was correlated with greater hippocampal volume. “While normal aging results in overall brain atrophy, lower omega-3 index may signal increased risk of hippocampal atrophy,” wrote the investigators.

Exposure to DDT may increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, particularly in people older than 60, according to a study published online ahead of print January 27 in JAMA Neurology. Researchers examined the level of DDE, the chemical compound produced when DDT breaks down in the body, in the blood of 86 patients with Alzheimer’s disease and 79 controls. Blood levels of DDE were almost four times higher in 74 of the patients with Alzheimer’s disease than in the controls. Patients with APOE4, which greatly increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, and high blood levels of DDE exhibited more severe cognitive impairment than patients without the gene. In addition, DDT and DDE apparently increased the amount of a protein associated with plaques believed to be a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

Mortality is higher among patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) than among Americans without the disease, according to research published online ahead of print December 26, 2013, in Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. Investigators extracted records from a US commercial health insurance database—the OptumInsight Research database—for 30,402 patients with MS and 89,818 healthy comparators. Patient data were recorded from 1996 to 2009. Annual mortality rates were 899/100,000 among patients with MS and 446/100,000 among comparators. Standardized mortality ratio was 1.70 for patients with MS and 0.80 for the general US population. Kaplan–Meier analysis yielded a median survival from birth that was six years lower among patients with MS than among comparators. The six-year decrement in lifespan is consistent with a decrement found in recent research conducted in Canada, said the investigators.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may increase the risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), researchers reported in the November 2013 issue of Mayo Clinic Proceedings. The investigators evaluated 1,927 patients (ages 70 to 89) enrolled in the population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Participants received a nurse assessment, neurologic evaluation, and neuropsychologic testing. A consensus panel diagnosed MCI according to standardized criteria. COPD was identified by the review of medical records. A total of 288 patients had COPD. Prevalence of MCI was 27% among patients with COPD and 15% among patients without COPD. The odds ratio for MCI was 1.60 in patients who had had COPD for five years or fewer and 2.10 in patients who had had COPD for more than five years.

—Erik Greb and Colby Stong

Alcohol consumption may reduce the risk of developing multiple sclerosis (MS) and attenuate the effect of smoking, according to research published online ahead of print January 6 in JAMA Neurology. Scientists examined data from the Epidemiological Investigation of MS (EIMS), which included 745 cases and 1,761 controls, and from the Genes and Environment in MS (GEMS) study, which recruited 5,874 cases and 5,246 controls. In EIMS, women who reported high alcohol consumption (>112 g/week) had an odds ratio (OR) of 0.6 of developing MS, compared with nondrinking women. Men with high alcohol consumption (>168 g/week) in EIMS had an OR of 0.5, compared with nondrinking men. The OR for the comparison in GEMS was 0.7 for women and 0.7 for men. In both studies, the detrimental effect of smoking was more pronounced among nondrinkers.

A lentiviral vector-based gene therapy may be safe and improve motor behavior in patients with Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published online ahead of print January 10 in Lancet. In a phase I–II open-label trial, 15 patients received bilateral injections of gene therapy into the putamen and were followed up for 12 months. Participants received a low dose (1.9 × 107 transducing units [TU]), medium dose (4.0 × 107 TU), or a high dose (1 × 108 TU) of gene therapy. Patients reported 51 mild adverse events, three moderate adverse events, and no serious adverse events. The investigators noted a significant improvement in mean Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III motor scores off medication in all patients at six months, compared with baseline.

The FDA has approved a three-times-per-week formulation of Copaxone 40 mg/mL. The new formulation will enable a less-frequent dosing regimen to be administered subcutaneously to patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). The approval is based on data from the Phase III Glatiramer Acetate Low-Frequency Administration study of more than 1,400 patients. In the trial, investigators found that a 40-mg/mL dose of Copaxone administered subcutaneously three times per week significantly reduced relapse rates at 12 months and demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. In addition to the newly approved dose, daily Copaxone 20 mg/mL will continue to be available. The daily subcutaneous injection was approved in 1996. Both formulations are manufactured by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, which is headquartered in Jerusalem.

When administered with amitriptyline, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may result in greater reductions in days with headache and in migraine-related disability among young persons with chronic migraine, compared with headache education, according to research published December 25, 2013, in JAMA. In a randomized clinical trial, 135 children (ages 10 to 17) with chronic migraine and a Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Score (PedMIDAS) greater than 20 points were assigned to CBT plus amitriptyline or headache education plus amitriptyline. At the 20-week end point, days with headache were reduced by 11.5 for the CBT plus amitriptyline group, compared with 6.8 for the headache education plus amitriptyline group. The PedMIDAS decreased by 52.7 points for the CBT group and by 38.6 points for the headache education group.

Low levels of vitamin D early in the course of multiple sclerosis (MS) are a strong risk factor for long-term disease activity and progression in patients who were primarily treated with interferon beta-1b, according to a study published online January 20 in JAMA Neurology. Researchers compared early and delayed interferon beta-1b treatment in 468 patients with clinically isolated syndrome, measuring serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) at baseline and at six, 12, and 24 months. “A 50-nmol/L (20-ng/mL) increment in average serum 25(OH)D levels within the first 12 months predicted a 57% lower rate of new active lesions, 57% lower relapse rate, 25% lower yearly increase in T2 lesion volume, and 0.41% lower yearly loss in brain volume from months 12 to 60,” stated the study authors.

Excessive alcohol consumption in men was associated with faster cognitive decline, compared with light to moderate alcohol consumption, researchers reported online ahead of print January 15 in Neurology. The findings are based on data from 5,054 men and 2,099 women (mean age, 56) who had their alcohol consumption analyzed three times in the 10 years preceding the first cognitive assessment. In men, the investigators observed no differences in cognitive decline among alcohol abstainers, those who quit using alcohol, and light or moderate alcohol drinkers (<20 g/day). Alcohol consumption ≥36 g/day was associated with faster decline in all cognitive domains, compared with consumption between 0.1 and 19.9 g/day. In women, 10-year abstainers had a faster decline in the global cognitive score and executive function, compared with those drinking between 0.1 and 9.9 g/day of alcohol.

Vitamin D supplements may reduce pain in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome, according to a study in the February issue of Pain. The randomized controlled trial enrolled 30 women with fibromyalgia syndrome with serum calcifediol levels <32 ng/mL (80 nmol/L), in whom the goal was to achieve serum calcifediol levels between 32 and 48 ng/mL for 20 weeks with an oral cholecalciferol supplement. Re-evaluation was performed in both groups after an additional 24 weeks without cholecalciferol supplementation. The researchers observed a marked reduction in pain during the treatment period in those who received the supplement, and optimization of calcifediol levels had a positive effect on the perception of pain. “This economical therapy with a low side effect profile may well be considered in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome,” the researchers concluded.

A simple on-field blood test may help diagnose sports concussion. Relative and absolute increases in the astroglial protein, serum S100B, can accurately distinguish sports-related concussion from sports-related exertion, according to a study published online January 8 in PLOS One. Serum S100B was measured in 46 collegiate and semiprofessional contact sport athletes at preseason baseline, within three hours of injury, and at days 2, 3, and 7 post–sports-related concussion. Twenty-two athletes had a sports-related concussion, and 17 had S100B testing within three hours postinjury. The mean three-hour post–sports-related concussion S100B level was significantly higher than at preseason baseline, while the mean postexertion S100B level was not significantly different than that from the preseason baseline. S100B levels at postinjury days 2, 3, and 7 were significantly lower than at the three-hour level and were not different than at baseline.

Herpes zoster is an independent risk factor for vascular disease, particularly for stroke, transient ischemic attack, and myocardial infarction, in patients affected before age 40, researchers reported online ahead of print January 2 in Neurology. The findings are based on a retrospective cohort of 106,601 cases of herpes zoster and 213,202 controls from a general practice database in the United Kingdom. The investigators found that risk factors for vascular disease were significantly increased in patients with herpes zoster compared with controls. In addition, adjusted hazard ratios for TIA and myocardial infarction, but not stroke, were increased in all patients with herpes zoster. Stroke, TIA, and myocardial infarction were increased in cases in which herpes zoster occurred when the participants were younger than 40.

A study appearing January 22 online in Neurology found that a higher omega-3 index was correlated with larger total normal brain volume and hippocampal volume in postmenopausal women measured eight years later. Researchers assessed RBC eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and MRI brain volumes in 1,111 postmenopausal women from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. In fully adjusted models, a 1-SD greater RBC EPA + DHA (omega-3 index) level was correlated with 2.1 cm3 larger brain volume. “DHA was marginally correlated with total brain volume while EPA was less so,” reported the investigators. In fully adjusted models, a 1-SD greater omega-3 index was correlated with greater hippocampal volume. “While normal aging results in overall brain atrophy, lower omega-3 index may signal increased risk of hippocampal atrophy,” wrote the investigators.

Exposure to DDT may increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, particularly in people older than 60, according to a study published online ahead of print January 27 in JAMA Neurology. Researchers examined the level of DDE, the chemical compound produced when DDT breaks down in the body, in the blood of 86 patients with Alzheimer’s disease and 79 controls. Blood levels of DDE were almost four times higher in 74 of the patients with Alzheimer’s disease than in the controls. Patients with APOE4, which greatly increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, and high blood levels of DDE exhibited more severe cognitive impairment than patients without the gene. In addition, DDT and DDE apparently increased the amount of a protein associated with plaques believed to be a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

Mortality is higher among patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) than among Americans without the disease, according to research published online ahead of print December 26, 2013, in Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. Investigators extracted records from a US commercial health insurance database—the OptumInsight Research database—for 30,402 patients with MS and 89,818 healthy comparators. Patient data were recorded from 1996 to 2009. Annual mortality rates were 899/100,000 among patients with MS and 446/100,000 among comparators. Standardized mortality ratio was 1.70 for patients with MS and 0.80 for the general US population. Kaplan–Meier analysis yielded a median survival from birth that was six years lower among patients with MS than among comparators. The six-year decrement in lifespan is consistent with a decrement found in recent research conducted in Canada, said the investigators.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may increase the risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), researchers reported in the November 2013 issue of Mayo Clinic Proceedings. The investigators evaluated 1,927 patients (ages 70 to 89) enrolled in the population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Participants received a nurse assessment, neurologic evaluation, and neuropsychologic testing. A consensus panel diagnosed MCI according to standardized criteria. COPD was identified by the review of medical records. A total of 288 patients had COPD. Prevalence of MCI was 27% among patients with COPD and 15% among patients without COPD. The odds ratio for MCI was 1.60 in patients who had had COPD for five years or fewer and 2.10 in patients who had had COPD for more than five years.

—Erik Greb and Colby Stong

Alcohol consumption may reduce the risk of developing multiple sclerosis (MS) and attenuate the effect of smoking, according to research published online ahead of print January 6 in JAMA Neurology. Scientists examined data from the Epidemiological Investigation of MS (EIMS), which included 745 cases and 1,761 controls, and from the Genes and Environment in MS (GEMS) study, which recruited 5,874 cases and 5,246 controls. In EIMS, women who reported high alcohol consumption (>112 g/week) had an odds ratio (OR) of 0.6 of developing MS, compared with nondrinking women. Men with high alcohol consumption (>168 g/week) in EIMS had an OR of 0.5, compared with nondrinking men. The OR for the comparison in GEMS was 0.7 for women and 0.7 for men. In both studies, the detrimental effect of smoking was more pronounced among nondrinkers.

A lentiviral vector-based gene therapy may be safe and improve motor behavior in patients with Parkinson’s disease, according to a study published online ahead of print January 10 in Lancet. In a phase I–II open-label trial, 15 patients received bilateral injections of gene therapy into the putamen and were followed up for 12 months. Participants received a low dose (1.9 × 107 transducing units [TU]), medium dose (4.0 × 107 TU), or a high dose (1 × 108 TU) of gene therapy. Patients reported 51 mild adverse events, three moderate adverse events, and no serious adverse events. The investigators noted a significant improvement in mean Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III motor scores off medication in all patients at six months, compared with baseline.

The FDA has approved a three-times-per-week formulation of Copaxone 40 mg/mL. The new formulation will enable a less-frequent dosing regimen to be administered subcutaneously to patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). The approval is based on data from the Phase III Glatiramer Acetate Low-Frequency Administration study of more than 1,400 patients. In the trial, investigators found that a 40-mg/mL dose of Copaxone administered subcutaneously three times per week significantly reduced relapse rates at 12 months and demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. In addition to the newly approved dose, daily Copaxone 20 mg/mL will continue to be available. The daily subcutaneous injection was approved in 1996. Both formulations are manufactured by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, which is headquartered in Jerusalem.

When administered with amitriptyline, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may result in greater reductions in days with headache and in migraine-related disability among young persons with chronic migraine, compared with headache education, according to research published December 25, 2013, in JAMA. In a randomized clinical trial, 135 children (ages 10 to 17) with chronic migraine and a Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Score (PedMIDAS) greater than 20 points were assigned to CBT plus amitriptyline or headache education plus amitriptyline. At the 20-week end point, days with headache were reduced by 11.5 for the CBT plus amitriptyline group, compared with 6.8 for the headache education plus amitriptyline group. The PedMIDAS decreased by 52.7 points for the CBT group and by 38.6 points for the headache education group.

Low levels of vitamin D early in the course of multiple sclerosis (MS) are a strong risk factor for long-term disease activity and progression in patients who were primarily treated with interferon beta-1b, according to a study published online January 20 in JAMA Neurology. Researchers compared early and delayed interferon beta-1b treatment in 468 patients with clinically isolated syndrome, measuring serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) at baseline and at six, 12, and 24 months. “A 50-nmol/L (20-ng/mL) increment in average serum 25(OH)D levels within the first 12 months predicted a 57% lower rate of new active lesions, 57% lower relapse rate, 25% lower yearly increase in T2 lesion volume, and 0.41% lower yearly loss in brain volume from months 12 to 60,” stated the study authors.

Excessive alcohol consumption in men was associated with faster cognitive decline, compared with light to moderate alcohol consumption, researchers reported online ahead of print January 15 in Neurology. The findings are based on data from 5,054 men and 2,099 women (mean age, 56) who had their alcohol consumption analyzed three times in the 10 years preceding the first cognitive assessment. In men, the investigators observed no differences in cognitive decline among alcohol abstainers, those who quit using alcohol, and light or moderate alcohol drinkers (<20 g/day). Alcohol consumption ≥36 g/day was associated with faster decline in all cognitive domains, compared with consumption between 0.1 and 19.9 g/day. In women, 10-year abstainers had a faster decline in the global cognitive score and executive function, compared with those drinking between 0.1 and 9.9 g/day of alcohol.

Vitamin D supplements may reduce pain in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome, according to a study in the February issue of Pain. The randomized controlled trial enrolled 30 women with fibromyalgia syndrome with serum calcifediol levels <32 ng/mL (80 nmol/L), in whom the goal was to achieve serum calcifediol levels between 32 and 48 ng/mL for 20 weeks with an oral cholecalciferol supplement. Re-evaluation was performed in both groups after an additional 24 weeks without cholecalciferol supplementation. The researchers observed a marked reduction in pain during the treatment period in those who received the supplement, and optimization of calcifediol levels had a positive effect on the perception of pain. “This economical therapy with a low side effect profile may well be considered in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome,” the researchers concluded.

A simple on-field blood test may help diagnose sports concussion. Relative and absolute increases in the astroglial protein, serum S100B, can accurately distinguish sports-related concussion from sports-related exertion, according to a study published online January 8 in PLOS One. Serum S100B was measured in 46 collegiate and semiprofessional contact sport athletes at preseason baseline, within three hours of injury, and at days 2, 3, and 7 post–sports-related concussion. Twenty-two athletes had a sports-related concussion, and 17 had S100B testing within three hours postinjury. The mean three-hour post–sports-related concussion S100B level was significantly higher than at preseason baseline, while the mean postexertion S100B level was not significantly different than that from the preseason baseline. S100B levels at postinjury days 2, 3, and 7 were significantly lower than at the three-hour level and were not different than at baseline.

Herpes zoster is an independent risk factor for vascular disease, particularly for stroke, transient ischemic attack, and myocardial infarction, in patients affected before age 40, researchers reported online ahead of print January 2 in Neurology. The findings are based on a retrospective cohort of 106,601 cases of herpes zoster and 213,202 controls from a general practice database in the United Kingdom. The investigators found that risk factors for vascular disease were significantly increased in patients with herpes zoster compared with controls. In addition, adjusted hazard ratios for TIA and myocardial infarction, but not stroke, were increased in all patients with herpes zoster. Stroke, TIA, and myocardial infarction were increased in cases in which herpes zoster occurred when the participants were younger than 40.

A study appearing January 22 online in Neurology found that a higher omega-3 index was correlated with larger total normal brain volume and hippocampal volume in postmenopausal women measured eight years later. Researchers assessed RBC eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and MRI brain volumes in 1,111 postmenopausal women from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. In fully adjusted models, a 1-SD greater RBC EPA + DHA (omega-3 index) level was correlated with 2.1 cm3 larger brain volume. “DHA was marginally correlated with total brain volume while EPA was less so,” reported the investigators. In fully adjusted models, a 1-SD greater omega-3 index was correlated with greater hippocampal volume. “While normal aging results in overall brain atrophy, lower omega-3 index may signal increased risk of hippocampal atrophy,” wrote the investigators.

Exposure to DDT may increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, particularly in people older than 60, according to a study published online ahead of print January 27 in JAMA Neurology. Researchers examined the level of DDE, the chemical compound produced when DDT breaks down in the body, in the blood of 86 patients with Alzheimer’s disease and 79 controls. Blood levels of DDE were almost four times higher in 74 of the patients with Alzheimer’s disease than in the controls. Patients with APOE4, which greatly increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, and high blood levels of DDE exhibited more severe cognitive impairment than patients without the gene. In addition, DDT and DDE apparently increased the amount of a protein associated with plaques believed to be a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease.

Mortality is higher among patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) than among Americans without the disease, according to research published online ahead of print December 26, 2013, in Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. Investigators extracted records from a US commercial health insurance database—the OptumInsight Research database—for 30,402 patients with MS and 89,818 healthy comparators. Patient data were recorded from 1996 to 2009. Annual mortality rates were 899/100,000 among patients with MS and 446/100,000 among comparators. Standardized mortality ratio was 1.70 for patients with MS and 0.80 for the general US population. Kaplan–Meier analysis yielded a median survival from birth that was six years lower among patients with MS than among comparators. The six-year decrement in lifespan is consistent with a decrement found in recent research conducted in Canada, said the investigators.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may increase the risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), researchers reported in the November 2013 issue of Mayo Clinic Proceedings. The investigators evaluated 1,927 patients (ages 70 to 89) enrolled in the population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Participants received a nurse assessment, neurologic evaluation, and neuropsychologic testing. A consensus panel diagnosed MCI according to standardized criteria. COPD was identified by the review of medical records. A total of 288 patients had COPD. Prevalence of MCI was 27% among patients with COPD and 15% among patients without COPD. The odds ratio for MCI was 1.60 in patients who had had COPD for five years or fewer and 2.10 in patients who had had COPD for more than five years.

—Erik Greb and Colby Stong

Regimen shows promise for ENKTL

SAN FRANCISCO—Results of a single-center study suggest that a 3-drug regimen may be a safe and effective treatment option for patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL).

The combination of pegaspargase, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin (P-Gemox) elicited a high rate of response in this cohort of 60 Chinese patients.

P-Gemox also produced higher survival rates than those previously observed with the EPOCH regimen.

Grade 1/2 myelosuppression occurred in more than half of patients in this study, and nearly three-quarters of patients experienced grade 1/2 nausea. But grade 3/4 adverse events were minimal.

Hui-qiang Huang, MD, PhD, of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, presented these results at the 6th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

Dr Huang noted that advanced ENKTL is relatively resistant to anthracycline-based chemotherapy. And although the SMILE and AspaMetDex regimens are effective, they confer relatively severe toxicities and are inconvenient to administer.

“So chemotherapeutic combinations with high efficacy and low toxicities are urgently needed,” he said.

With this in mind, he and his colleagues assessed P-Gemox in 61 patients with ENKTL. Thirty-six patients were newly diagnosed, and 25 had relapsed/refractory disease. Roughly 69% of patients were male, and about 86% were older than 60 years of age.

Overall, 36.1% of patients had stage IE disease, 31.1% had stage IIE, 4.9% had stage IIIE, and 27.9% had stage IVE.

The relapsed/refractory patients had received a range of prior treatment regimens, including CHOP/L-ASP+CHOP, EPOCH, V-EPOCH, ICE, IMVP-16, and SMILE. And 13 patients had received radiotherapy.

For this study, all 61 patients received intravenous gemcitabine at 1000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8, intravenous oxaliplatin at 130 mg/m2 on day 1, and intramuscular pegaspargase at 2500 U/m2 on day 1. This regimen was repeated every 3 weeks.

Patients with stage IE/IIE disease received 3 cycles followed by radiotherapy (50-56 Gy). Relapsed/refractory patients received 2 to 6 cycles, and those who responded well were recommended for autologous transplant.

Response and subsequent treatment

Sixty patients were evaluable for response. (One patient in the newly diagnosed group was not evaluable).

The overall response rate (ORR) was 90%, with 63.3% of patients achieving a complete response (CR), 26.7% achieving a partial response (PR), and 8.3% maintaining stable disease (SD).

Among newly diagnosed patients, the ORR was 94.3%. CRs occurred in 74.3% of patients, PRs in in 20%, and SD in 5.7%.

And among the relapsed/refractory patients, the ORR was 84%. CRs were seen in 48% of patients, PRs in 36%, and SD in 12%.

“For patients with early stage disease, we found P-Gemox can further improve the outcomes of radiotherapy,” Dr Huang noted.

The treatment also provided a good bridge to transplant. Eight patients underwent transplant after achieving CR. One of these patients died 9 months after the procedure, but the other 7 patients were still in CR at a median of 14.6 months (range, 4.8-19.7 months).

‘Encouraging’ survival

The median follow-up was 29.5 months. The researchers confirmed progressive disease in 18 of the 61 patients—7 in the newly diagnosed group and 11 in the relapsed/refractory group.

Nine patients died of disease progression—1 in the newly diagnosed group and 8 in the relapsed/refractory group.

The 2-year overall survival was 86%, and the 2-year progression-free survival was 75.6%. Both overall and progression-free survival were superior in the newly diagnosed patients (P=0.054 and P=0.004, respectively).

“For the relapsed/refractory cases, considering they had already received a lot of previous treatments, we thought this outcome with P-Gemox is still quite encouraging,” Dr Huang said.

When the researchers compared overall survival with P-Gemox to previous results observed with EPOCH in newly diagnosed ENKTL patients (Huang et al, Leuk & Lymph 2011), they found P-Gemox was superior.

‘Tolerable’ toxicity

Toxicity with P-Gemox was tolerable and manageable, according to Dr Huang. The main adverse events were nausea and myelosuppression. But the rate of grade 3/4 events was low, and there were no treatment-related deaths.

Specifically, the grade 1/2 adverse events included nausea (73.8%), neutropenia (58%), thrombocytopenia (52.4%), hypoprotinemia (52.4%), anemia (52.4%), vomiting (49.2%), prolonged APTT (44.2%), elevated transaminase (34.1%), elevated bilirubin (27.9%), mucositis (24.5%), decreased fibrinogen (23%), elevated BUN (4.9%), intracranial bleeding (1.6%), stomach bleeding (1.6%), pancreatitis (1.6%), and herpes (1.6%).

Grade 3/4 adverse events included neutropenia (19.7%), thrombocytopenia (16.4%), hypoprotinemia (1.6%), anemia (1.6%), vomiting (3.2%), elevated transaminase (1.6%), and decreased fibrinogen (1.6%).

“We found that P-Gemox is an effective, safe, and convenient regimen in Chinese patients with ENKTL, both treatment-naïve and relapsed/refractory,” Dr Huang concluded. “These results provide a basis for subsequent studies.”

Dr Huang and his colleagues also presented the results of this research at the ASH Annual Meeting in December as abstract 642. (Information presented at the T-cell Lymphoma Forum differs from that in the ASH abstract). ![]()

SAN FRANCISCO—Results of a single-center study suggest that a 3-drug regimen may be a safe and effective treatment option for patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL).

The combination of pegaspargase, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin (P-Gemox) elicited a high rate of response in this cohort of 60 Chinese patients.

P-Gemox also produced higher survival rates than those previously observed with the EPOCH regimen.

Grade 1/2 myelosuppression occurred in more than half of patients in this study, and nearly three-quarters of patients experienced grade 1/2 nausea. But grade 3/4 adverse events were minimal.

Hui-qiang Huang, MD, PhD, of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, presented these results at the 6th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

Dr Huang noted that advanced ENKTL is relatively resistant to anthracycline-based chemotherapy. And although the SMILE and AspaMetDex regimens are effective, they confer relatively severe toxicities and are inconvenient to administer.

“So chemotherapeutic combinations with high efficacy and low toxicities are urgently needed,” he said.

With this in mind, he and his colleagues assessed P-Gemox in 61 patients with ENKTL. Thirty-six patients were newly diagnosed, and 25 had relapsed/refractory disease. Roughly 69% of patients were male, and about 86% were older than 60 years of age.

Overall, 36.1% of patients had stage IE disease, 31.1% had stage IIE, 4.9% had stage IIIE, and 27.9% had stage IVE.

The relapsed/refractory patients had received a range of prior treatment regimens, including CHOP/L-ASP+CHOP, EPOCH, V-EPOCH, ICE, IMVP-16, and SMILE. And 13 patients had received radiotherapy.

For this study, all 61 patients received intravenous gemcitabine at 1000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8, intravenous oxaliplatin at 130 mg/m2 on day 1, and intramuscular pegaspargase at 2500 U/m2 on day 1. This regimen was repeated every 3 weeks.

Patients with stage IE/IIE disease received 3 cycles followed by radiotherapy (50-56 Gy). Relapsed/refractory patients received 2 to 6 cycles, and those who responded well were recommended for autologous transplant.

Response and subsequent treatment

Sixty patients were evaluable for response. (One patient in the newly diagnosed group was not evaluable).

The overall response rate (ORR) was 90%, with 63.3% of patients achieving a complete response (CR), 26.7% achieving a partial response (PR), and 8.3% maintaining stable disease (SD).

Among newly diagnosed patients, the ORR was 94.3%. CRs occurred in 74.3% of patients, PRs in in 20%, and SD in 5.7%.

And among the relapsed/refractory patients, the ORR was 84%. CRs were seen in 48% of patients, PRs in 36%, and SD in 12%.

“For patients with early stage disease, we found P-Gemox can further improve the outcomes of radiotherapy,” Dr Huang noted.

The treatment also provided a good bridge to transplant. Eight patients underwent transplant after achieving CR. One of these patients died 9 months after the procedure, but the other 7 patients were still in CR at a median of 14.6 months (range, 4.8-19.7 months).

‘Encouraging’ survival

The median follow-up was 29.5 months. The researchers confirmed progressive disease in 18 of the 61 patients—7 in the newly diagnosed group and 11 in the relapsed/refractory group.

Nine patients died of disease progression—1 in the newly diagnosed group and 8 in the relapsed/refractory group.

The 2-year overall survival was 86%, and the 2-year progression-free survival was 75.6%. Both overall and progression-free survival were superior in the newly diagnosed patients (P=0.054 and P=0.004, respectively).

“For the relapsed/refractory cases, considering they had already received a lot of previous treatments, we thought this outcome with P-Gemox is still quite encouraging,” Dr Huang said.

When the researchers compared overall survival with P-Gemox to previous results observed with EPOCH in newly diagnosed ENKTL patients (Huang et al, Leuk & Lymph 2011), they found P-Gemox was superior.

‘Tolerable’ toxicity

Toxicity with P-Gemox was tolerable and manageable, according to Dr Huang. The main adverse events were nausea and myelosuppression. But the rate of grade 3/4 events was low, and there were no treatment-related deaths.

Specifically, the grade 1/2 adverse events included nausea (73.8%), neutropenia (58%), thrombocytopenia (52.4%), hypoprotinemia (52.4%), anemia (52.4%), vomiting (49.2%), prolonged APTT (44.2%), elevated transaminase (34.1%), elevated bilirubin (27.9%), mucositis (24.5%), decreased fibrinogen (23%), elevated BUN (4.9%), intracranial bleeding (1.6%), stomach bleeding (1.6%), pancreatitis (1.6%), and herpes (1.6%).

Grade 3/4 adverse events included neutropenia (19.7%), thrombocytopenia (16.4%), hypoprotinemia (1.6%), anemia (1.6%), vomiting (3.2%), elevated transaminase (1.6%), and decreased fibrinogen (1.6%).

“We found that P-Gemox is an effective, safe, and convenient regimen in Chinese patients with ENKTL, both treatment-naïve and relapsed/refractory,” Dr Huang concluded. “These results provide a basis for subsequent studies.”

Dr Huang and his colleagues also presented the results of this research at the ASH Annual Meeting in December as abstract 642. (Information presented at the T-cell Lymphoma Forum differs from that in the ASH abstract). ![]()

SAN FRANCISCO—Results of a single-center study suggest that a 3-drug regimen may be a safe and effective treatment option for patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL).

The combination of pegaspargase, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin (P-Gemox) elicited a high rate of response in this cohort of 60 Chinese patients.

P-Gemox also produced higher survival rates than those previously observed with the EPOCH regimen.

Grade 1/2 myelosuppression occurred in more than half of patients in this study, and nearly three-quarters of patients experienced grade 1/2 nausea. But grade 3/4 adverse events were minimal.

Hui-qiang Huang, MD, PhD, of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, presented these results at the 6th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum.

Dr Huang noted that advanced ENKTL is relatively resistant to anthracycline-based chemotherapy. And although the SMILE and AspaMetDex regimens are effective, they confer relatively severe toxicities and are inconvenient to administer.

“So chemotherapeutic combinations with high efficacy and low toxicities are urgently needed,” he said.

With this in mind, he and his colleagues assessed P-Gemox in 61 patients with ENKTL. Thirty-six patients were newly diagnosed, and 25 had relapsed/refractory disease. Roughly 69% of patients were male, and about 86% were older than 60 years of age.

Overall, 36.1% of patients had stage IE disease, 31.1% had stage IIE, 4.9% had stage IIIE, and 27.9% had stage IVE.

The relapsed/refractory patients had received a range of prior treatment regimens, including CHOP/L-ASP+CHOP, EPOCH, V-EPOCH, ICE, IMVP-16, and SMILE. And 13 patients had received radiotherapy.

For this study, all 61 patients received intravenous gemcitabine at 1000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8, intravenous oxaliplatin at 130 mg/m2 on day 1, and intramuscular pegaspargase at 2500 U/m2 on day 1. This regimen was repeated every 3 weeks.

Patients with stage IE/IIE disease received 3 cycles followed by radiotherapy (50-56 Gy). Relapsed/refractory patients received 2 to 6 cycles, and those who responded well were recommended for autologous transplant.

Response and subsequent treatment

Sixty patients were evaluable for response. (One patient in the newly diagnosed group was not evaluable).

The overall response rate (ORR) was 90%, with 63.3% of patients achieving a complete response (CR), 26.7% achieving a partial response (PR), and 8.3% maintaining stable disease (SD).

Among newly diagnosed patients, the ORR was 94.3%. CRs occurred in 74.3% of patients, PRs in in 20%, and SD in 5.7%.

And among the relapsed/refractory patients, the ORR was 84%. CRs were seen in 48% of patients, PRs in 36%, and SD in 12%.

“For patients with early stage disease, we found P-Gemox can further improve the outcomes of radiotherapy,” Dr Huang noted.

The treatment also provided a good bridge to transplant. Eight patients underwent transplant after achieving CR. One of these patients died 9 months after the procedure, but the other 7 patients were still in CR at a median of 14.6 months (range, 4.8-19.7 months).

‘Encouraging’ survival

The median follow-up was 29.5 months. The researchers confirmed progressive disease in 18 of the 61 patients—7 in the newly diagnosed group and 11 in the relapsed/refractory group.

Nine patients died of disease progression—1 in the newly diagnosed group and 8 in the relapsed/refractory group.

The 2-year overall survival was 86%, and the 2-year progression-free survival was 75.6%. Both overall and progression-free survival were superior in the newly diagnosed patients (P=0.054 and P=0.004, respectively).

“For the relapsed/refractory cases, considering they had already received a lot of previous treatments, we thought this outcome with P-Gemox is still quite encouraging,” Dr Huang said.

When the researchers compared overall survival with P-Gemox to previous results observed with EPOCH in newly diagnosed ENKTL patients (Huang et al, Leuk & Lymph 2011), they found P-Gemox was superior.

‘Tolerable’ toxicity

Toxicity with P-Gemox was tolerable and manageable, according to Dr Huang. The main adverse events were nausea and myelosuppression. But the rate of grade 3/4 events was low, and there were no treatment-related deaths.

Specifically, the grade 1/2 adverse events included nausea (73.8%), neutropenia (58%), thrombocytopenia (52.4%), hypoprotinemia (52.4%), anemia (52.4%), vomiting (49.2%), prolonged APTT (44.2%), elevated transaminase (34.1%), elevated bilirubin (27.9%), mucositis (24.5%), decreased fibrinogen (23%), elevated BUN (4.9%), intracranial bleeding (1.6%), stomach bleeding (1.6%), pancreatitis (1.6%), and herpes (1.6%).

Grade 3/4 adverse events included neutropenia (19.7%), thrombocytopenia (16.4%), hypoprotinemia (1.6%), anemia (1.6%), vomiting (3.2%), elevated transaminase (1.6%), and decreased fibrinogen (1.6%).

“We found that P-Gemox is an effective, safe, and convenient regimen in Chinese patients with ENKTL, both treatment-naïve and relapsed/refractory,” Dr Huang concluded. “These results provide a basis for subsequent studies.”

Dr Huang and his colleagues also presented the results of this research at the ASH Annual Meeting in December as abstract 642. (Information presented at the T-cell Lymphoma Forum differs from that in the ASH abstract). ![]()

System allows precise gene editing in monkeys

Credit: Yuyu Niu et al.

Although monkeys can be useful as models of human disease, precisely modifying their genes has proven difficult.

Now, investigators say they’ve achieved precise gene modification in monkeys using the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

“Our study shows that the CRISPR/Cas9 system enables simultaneous disruption of 2 target genes in 1 step, without producing off-target mutations,” said Jiahao Sha, PhD, of Nanjing Medical University in Nanjing, China.

“Considering that many human diseases are caused by genetic abnormalities, targeted genetic modification in monkeys is invaluable for the generation of human disease models.”

Dr Sha and his colleagues described this research in Cell.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is a gene-editing tool capable of targeting specific DNA sequences in the genome. Cas9 proteins, which are directed by single-guide RNAs to specific sites in the genome, generate mutations by introducing double-stranded DNA breaks.

Until now, the CRISPR/Cas9 system and other targeted gene-editing techniques were successfully applied to mammals such as mice and rats, but not to primates.

Dr Sha and his colleagues injected messenger RNA encoding Cas9, as well as single-guide RNAs designed to target 3 specific genes, into one-cell-stage embryos of cynomolgus monkeys.

After sequencing DNA from 15 embryos, the team found that 8 of these embryos showed evidence of simultaneous mutations in 2 of the target genes.

The researchers then transferred genetically modified embryos into surrogate females, one of which gave birth to a set of twins. By sequencing the twins’ DNA, the team found mutations in 2 of the target genes.

Moreover, the CRISPR/Cas9 system did not produce mutations at genomic sites that were not targeted. And this suggests the tool will not cause undesirable effects when applied to monkeys.

“With the precise genomic targeting of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, we expect that many disease models will be generated in monkeys,” said Weizhi Ji, PhD, of the Yunnan Key Laboratory of Primate Biomedical Research in Kunming, China.

“[This] will significantly advance the development of therapeutic strategies in biomedical research.” ![]()

Credit: Yuyu Niu et al.

Although monkeys can be useful as models of human disease, precisely modifying their genes has proven difficult.

Now, investigators say they’ve achieved precise gene modification in monkeys using the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

“Our study shows that the CRISPR/Cas9 system enables simultaneous disruption of 2 target genes in 1 step, without producing off-target mutations,” said Jiahao Sha, PhD, of Nanjing Medical University in Nanjing, China.

“Considering that many human diseases are caused by genetic abnormalities, targeted genetic modification in monkeys is invaluable for the generation of human disease models.”

Dr Sha and his colleagues described this research in Cell.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is a gene-editing tool capable of targeting specific DNA sequences in the genome. Cas9 proteins, which are directed by single-guide RNAs to specific sites in the genome, generate mutations by introducing double-stranded DNA breaks.

Until now, the CRISPR/Cas9 system and other targeted gene-editing techniques were successfully applied to mammals such as mice and rats, but not to primates.

Dr Sha and his colleagues injected messenger RNA encoding Cas9, as well as single-guide RNAs designed to target 3 specific genes, into one-cell-stage embryos of cynomolgus monkeys.

After sequencing DNA from 15 embryos, the team found that 8 of these embryos showed evidence of simultaneous mutations in 2 of the target genes.

The researchers then transferred genetically modified embryos into surrogate females, one of which gave birth to a set of twins. By sequencing the twins’ DNA, the team found mutations in 2 of the target genes.

Moreover, the CRISPR/Cas9 system did not produce mutations at genomic sites that were not targeted. And this suggests the tool will not cause undesirable effects when applied to monkeys.

“With the precise genomic targeting of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, we expect that many disease models will be generated in monkeys,” said Weizhi Ji, PhD, of the Yunnan Key Laboratory of Primate Biomedical Research in Kunming, China.

“[This] will significantly advance the development of therapeutic strategies in biomedical research.” ![]()

Credit: Yuyu Niu et al.

Although monkeys can be useful as models of human disease, precisely modifying their genes has proven difficult.

Now, investigators say they’ve achieved precise gene modification in monkeys using the CRISPR/Cas9 system.

“Our study shows that the CRISPR/Cas9 system enables simultaneous disruption of 2 target genes in 1 step, without producing off-target mutations,” said Jiahao Sha, PhD, of Nanjing Medical University in Nanjing, China.

“Considering that many human diseases are caused by genetic abnormalities, targeted genetic modification in monkeys is invaluable for the generation of human disease models.”

Dr Sha and his colleagues described this research in Cell.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is a gene-editing tool capable of targeting specific DNA sequences in the genome. Cas9 proteins, which are directed by single-guide RNAs to specific sites in the genome, generate mutations by introducing double-stranded DNA breaks.

Until now, the CRISPR/Cas9 system and other targeted gene-editing techniques were successfully applied to mammals such as mice and rats, but not to primates.

Dr Sha and his colleagues injected messenger RNA encoding Cas9, as well as single-guide RNAs designed to target 3 specific genes, into one-cell-stage embryos of cynomolgus monkeys.

After sequencing DNA from 15 embryos, the team found that 8 of these embryos showed evidence of simultaneous mutations in 2 of the target genes.

The researchers then transferred genetically modified embryos into surrogate females, one of which gave birth to a set of twins. By sequencing the twins’ DNA, the team found mutations in 2 of the target genes.

Moreover, the CRISPR/Cas9 system did not produce mutations at genomic sites that were not targeted. And this suggests the tool will not cause undesirable effects when applied to monkeys.

“With the precise genomic targeting of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, we expect that many disease models will be generated in monkeys,” said Weizhi Ji, PhD, of the Yunnan Key Laboratory of Primate Biomedical Research in Kunming, China.

“[This] will significantly advance the development of therapeutic strategies in biomedical research.” ![]()

Inhibitor strengthens RBCs in PNH

Credit: NHLBI

The apoptosis inhibitor aurin tricarboxylic acid (ATA) is active against paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinemia (PNH), according to research published in PLOS ONE.

PNH is a rare condition in which red blood cells (RBCs) become vulnerable to attacks by the complement immune system and subsequently rupture.

This can lead to complications such as anemia, kidney disease, and fatal thromboses.

PNH results from a lack of 2 proteins that protect RBCs from destruction: decay-accelerating factor (CD55), an inhibitor of alternative pathway C3 convertase, and protectin (CD59), an inhibitor of membrane attack complex (MAC) formation.

Because previous studies suggested that ATA selectively blocks complement activation at the C3 convertase stage and MAC formation at the C9 insertion stage, researchers thought ATA might prove effective against PNH.

First, they compared RBCs from 5 patients with PNH (who were on long-term treatment with eculizumab) to RBCs from healthy individuals.

Despite the eculizumab, the PNH patients’ RBCs were twice as vulnerable to complement-induced lysis as the healthy subjects’ RBCs. And western blot revealed both C3 and C5 convertases on the membranes of patients’ RBCs.

However, when the researchers added ATA to patients’ blood samples, the RBCs were protected from complement attack. In fact, the drug restored the RBCs’ resistance to the same level as normal RBCs.

“Our study suggests that ATA could offer more complete protection as an oral treatment for PNH, while eliminating the need for infusions,” said study author Patrick McGeer, MD, PhD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

“PNH is a disease that may happen to anyone through a chance mutation, and, if nature were to design a perfect fix for this mutation, it would be ATA.”

Dr McGeer added that many diseases are caused or worsened by an overactive complement immune system. So his group’s findings could have implications for conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, macular degeneration, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

He and his colleagues are now proceeding with further testing, and Dr McGeer expects ATA could be available in clinics within a year. ![]()

Credit: NHLBI

The apoptosis inhibitor aurin tricarboxylic acid (ATA) is active against paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinemia (PNH), according to research published in PLOS ONE.

PNH is a rare condition in which red blood cells (RBCs) become vulnerable to attacks by the complement immune system and subsequently rupture.

This can lead to complications such as anemia, kidney disease, and fatal thromboses.

PNH results from a lack of 2 proteins that protect RBCs from destruction: decay-accelerating factor (CD55), an inhibitor of alternative pathway C3 convertase, and protectin (CD59), an inhibitor of membrane attack complex (MAC) formation.

Because previous studies suggested that ATA selectively blocks complement activation at the C3 convertase stage and MAC formation at the C9 insertion stage, researchers thought ATA might prove effective against PNH.

First, they compared RBCs from 5 patients with PNH (who were on long-term treatment with eculizumab) to RBCs from healthy individuals.

Despite the eculizumab, the PNH patients’ RBCs were twice as vulnerable to complement-induced lysis as the healthy subjects’ RBCs. And western blot revealed both C3 and C5 convertases on the membranes of patients’ RBCs.

However, when the researchers added ATA to patients’ blood samples, the RBCs were protected from complement attack. In fact, the drug restored the RBCs’ resistance to the same level as normal RBCs.

“Our study suggests that ATA could offer more complete protection as an oral treatment for PNH, while eliminating the need for infusions,” said study author Patrick McGeer, MD, PhD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

“PNH is a disease that may happen to anyone through a chance mutation, and, if nature were to design a perfect fix for this mutation, it would be ATA.”

Dr McGeer added that many diseases are caused or worsened by an overactive complement immune system. So his group’s findings could have implications for conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, macular degeneration, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

He and his colleagues are now proceeding with further testing, and Dr McGeer expects ATA could be available in clinics within a year. ![]()

Credit: NHLBI

The apoptosis inhibitor aurin tricarboxylic acid (ATA) is active against paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinemia (PNH), according to research published in PLOS ONE.

PNH is a rare condition in which red blood cells (RBCs) become vulnerable to attacks by the complement immune system and subsequently rupture.

This can lead to complications such as anemia, kidney disease, and fatal thromboses.

PNH results from a lack of 2 proteins that protect RBCs from destruction: decay-accelerating factor (CD55), an inhibitor of alternative pathway C3 convertase, and protectin (CD59), an inhibitor of membrane attack complex (MAC) formation.

Because previous studies suggested that ATA selectively blocks complement activation at the C3 convertase stage and MAC formation at the C9 insertion stage, researchers thought ATA might prove effective against PNH.

First, they compared RBCs from 5 patients with PNH (who were on long-term treatment with eculizumab) to RBCs from healthy individuals.

Despite the eculizumab, the PNH patients’ RBCs were twice as vulnerable to complement-induced lysis as the healthy subjects’ RBCs. And western blot revealed both C3 and C5 convertases on the membranes of patients’ RBCs.

However, when the researchers added ATA to patients’ blood samples, the RBCs were protected from complement attack. In fact, the drug restored the RBCs’ resistance to the same level as normal RBCs.

“Our study suggests that ATA could offer more complete protection as an oral treatment for PNH, while eliminating the need for infusions,” said study author Patrick McGeer, MD, PhD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

“PNH is a disease that may happen to anyone through a chance mutation, and, if nature were to design a perfect fix for this mutation, it would be ATA.”

Dr McGeer added that many diseases are caused or worsened by an overactive complement immune system. So his group’s findings could have implications for conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, macular degeneration, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

He and his colleagues are now proceeding with further testing, and Dr McGeer expects ATA could be available in clinics within a year. ![]()

Measuring Agreement After CICU Handoffs

Increasing attention has been paid to the need for effective handoffs between healthcare providers since the Joint Commission identified standardized handoff protocols as a National Patient Safety Goal in 2006.1 Aside from adverse consequences for patients, poor handoffs produce provider uncertainty about care plans.[2, 3] Agreement on clinical information after a handoff is critical because a significant proportion of data is not documented in the medical record, leaving providers reliant on verbal communication.[4, 5, 6] Providers may enter the handoff with differing opinions; however, to mitigate the potential safety consequences of discontinuity of care,[7] the goal should be to achieve consensus about proposed courses of action.

Given the recent focus on improving handoffs, rigorous, outcome‐driven measures of handoff quality are clearly needed, but measuring shift‐to‐shift handoff quality has proved challenging.[8, 9] Previous studies of physician handoffs surveyed receivers for satisfaction,[10, 11] compared reported omissions to audio recordings,[3] and developed evaluation tools for receivers to rate handoffs.[12, 13, 14, 15] None directly assess the underlying goal of a handoff: the transfer of understanding from sender to receiver, enabling safe transfer of patient care responsibility.[16] We therefore chose to measure agreement on patient condition and treatment plans following handoff as an indicator of the quality of the shared clinical understanding formed. Advantages of piloting this approach in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) include the relatively homogenous patient population and small number of medical providers. If effective, the strategy of tool development and evaluation could be generalized to different clinical environments and provider groups.

Our aim was to develop and validate a tool to measure the level of shared clinical understanding regarding the condition and treatment plan of a CICU patient after handoff. The tool we designed was the pediatric cardiology Patient Knowledge Assessment Tool (PKAT), a brief, multiple‐item questionnaire focused on key data elements for individual CICU patients. Although variation in provider opinion helps detect diagnostic or treatment errors,[8] the PKAT is based on the assumption that achieving consensus on clinical status and the next steps of care is the goal of the handoff.

METHODS

Setting

The CICU is a 24‐bed medical and surgical unit in a 500‐bed free standing children's hospital. CICU attending physicians work 12‐ or 24‐hour shifts and supervise front line clinicians (including subspecialty fellows, nurse practitioners, and hospitalists, referred to as clinicians in this article) who work day or night shifts. Handoffs occur twice daily, with no significant differences in handoff practices between the 2 times. Attending physicians (referred to as attendings in this article) conduct parallel but separate handoffs from clinicians. All providers work exclusively in the CICU with the exception of fellows, who rotate monthly.

This study was approved by the institutional review board at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. All provider subjects provided informed consent. Consent for patient subjects was waived.

Development of the PKAT

We developed the PKAT content domains based on findings from previous studies,[2, 3] unpublished survey data about handoff omissions in our CICU, and CICU attending expert opinion. Pilot testing included 39 attendings and clinicians involved in 60 handoffs representing a wide variety of admissions. Participants were encouraged to share opinions on tool content and design with study staff. The PKAT (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article) was refined iteratively based on this feedback.

Video Simulation Testing

We used video simulation to test the PKAT for inter‐rater reliability. Nine patient handoff scenarios were written with varying levels of patient complexity and clarity of dialogue. The scenarios were filmed using the same actors and location to minimize variability aside from content. We recruited 10 experienced provider subjects (attendings and senior fellows) to minimize the effect of knowledge deficits. For each simulated handoff, subjects were encouraged to annotate a mock sign‐out sheet, which mimicked the content and format of the CICU sign‐out sheet. After watching all 9 scenarios, subjects completed a PKAT for each handoff from the perspective of the receiver based on the videotape. These standardized conditions allowed for assessment of inter‐rater reliability.

In Situ Testing

We then tested the PKAT in situ in the CICU to assess construct validity. We chose to study the morning handoff because the timing and location are more consistent. We planned to study 90 patient handoffs because the standard practice for testing a new psychometric instrument is to collect 10 observations per item.[17] On study days, 4 providers completed a PKAT for each selected handoff: the sending attending, receiving attending, sending clinician, and receiving clinician.

Study days were scheduled over 2 months to encompass a range of providers. Given the small number of attendings, we did not exclude those who had participated in video simulation testing. On study days, 6 patients were enrolled using stratified sampling to ensure adequate representation of new admissions (ie, admitted within 24 hours). The sending attending received the PKAT forms prior to the handoff. The receiving attending and clinicians received the PKAT after handoff. This difference in administration was due to logistic concerns: sending attendings requested to receive the PKATs earlier because they had to complete all 6 PKATs, whereas other providers completed 3 or fewer per day. Thus, sending attendings could complete the PKAT before or after the handoff, whereas all other participants completed the instrument after the handoff.

To test for construct validity, we gathered data on participating providers and patients, hypothesizing that PKAT agreement levels would decrease in response to less experienced providers or more complex patients. Provider characteristics included previous handoff education and amount of time worked in our CICU. Attending CICU experience was dichotomized into first year versus second or greater year. Clinician experience was dichotomized into first or second month versus third or greater month of CICU service. Each PKAT asked the handoff receiver whether he or she had recently cared for this patient or gathered information prior to handoff (eg, speaking to bedside nurse).

Recorded patient characteristics included age, length of stay, and admission type including neonatal/preoperative observation, postoperative (first 7 days after operation), prolonged postoperative (>7 days after operation), and medical (all others). In recognition of differences in handoffs during the first 24 hours of admission and the right‐skewed length of stay in the CICU, we analyzed length of stay based on the following categories: new admission (<24 hours), days 2 to 7, days 8 to 14, days 15 to 31, and >31 days. Because the number of active medications has been shown to correlate with treatment regimen complexity[18] and physician ratings of illness severity,[19] we recorded this number as a surrogate measure of patient complexity. For analytic purposes, we categorized the number of active medications into quartiles.

Provider subject characteristics and PKAT responses were collected using paper forms and entered into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture; REDCap Consortium,

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome measure was the PKAT agreement level among providers evaluating the same handoff. For the reliability assessment, we calculated agreement across all providers analyzing the simulation videos, expecting that multiple providers should have high agreement for the same scenarios if the instrument has high inter‐rater reliability. For the validity assessment, we calculated agreement for each individual handoff by item and then calculated average levels of agreement for each item across provider and patient characteristics. We analyzed handoffs between attendings and clinicians separately. For items with mutually exclusive responses, simple yes/no agreement was calculated. For items requiring at least 1 response, agreement was coded when both respondents selected at least 1 response in common. For items that did not require a selection, credit was given if both subjects agreed that none of the conditions were present or if they agreed that at least 1 condition was present. In a secondary analysis, we repeated the analyses with unique sender‐receiver pair as the unit of analysis to account for correlation in the pair interaction.

Summary statistics were used to describe provider and patient characteristics. Mean rates of agreement with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each item. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare mean results between groups (eg, attendings vs clinicians). A nonparametric test for trend, which is an extension of the Wilcoxon rank sum test,[21] was used to compare mean results across ordered categories (eg, length of stay). All tests of significance were at P<0.05 level and 2‐tailed. All statistical analysis was done using Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Provider subject types are represented in Table 1. Handoffs between these 29 individuals resulted in 70 unique sender and receiver combinations with a median of 2 PKATs completed per unique sender‐receiver pair (range, 115). Attendings had lower rates of handoff education than clinicians (11% vs 85% for in situ testing participants, P=0.01). Attendings participating in in situ testing had worked in the CICU for a median of 3 years (range, 116 years). Clinicians participating in in situ testing had a median of 3 months of CICU experience (range, 195 months). Providers were 100% compliant with PKAT completion.

| Simulation Testing, n=10 | In Situ Testing, n=29 | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Attending physicians | 40% (4) | 31% (9) |

| Clinicians | 60% (6) | 69% (20) |

| Clinician type | ||

| Cardiology | 67% (4) | 35% (7) |

| Critical care medicine | 33% (2) | 25% (5) |

| CICU nurse practitioner | 25% (5) | |

| Anesthesia | 5% (1) | |

| Neonatology | 5% (1) | |

| Hospitalist | 5% (1) | |

Video Simulation Testing

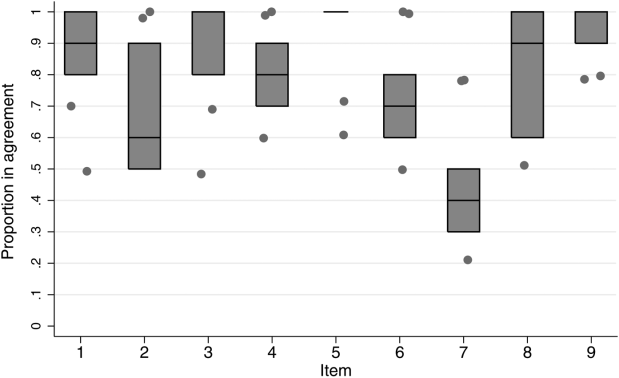

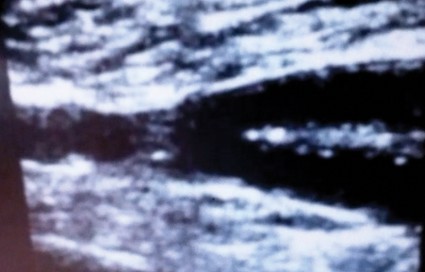

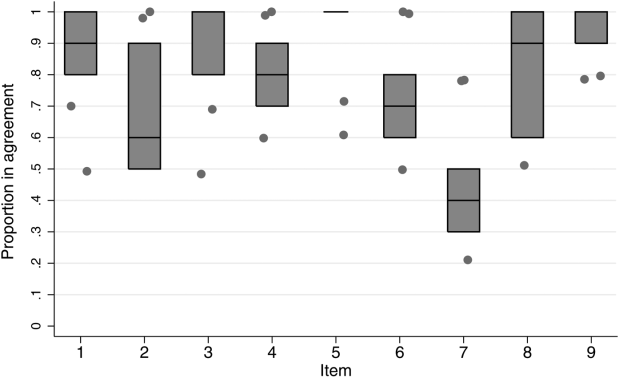

Inter‐rater agreement is shown in Figure 1. Raters achieved perfect agreement for 8/9 questions on at least 1 scenario, supporting high inter‐rater reliability for these items. Some items had particularly high reliability. For example, on item 3, subjects achieved perfect agreement for 5/9 scenarios, making 1 both the median and maximum value. Because item 7 (barriers to transfer) did not demonstrate high inter‐rater agreement, we excluded it from the in situ analysis.

In Situ Testing

Characteristics of patients whose handoffs were selected for in situ testing are listed in Table 2. Because some patients were selected on multiple study days, these 90 handoffs represented 58 unique patients. These 58 patients are representative of the CICU population (data not shown). The number of handoffs studied per patient ranged from 1 to 7 (median 1). A total of 19 patients were included in the study more than once; 13 were included twice.

| Characteristic | Categories | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Age | <1 month | 30 |

| 112 months | 34 | |

| 112 years | 28 | |

| 1318 years | 6 | |

| >18 years | 2 | |

| Type of admission | Postnatal observation/preoperative | 20 |

| Postoperative | 29 | |

| Prolonged postoperative (>7 days) | 33 | |

| Other admission | 18 | |

| CICU days | 1 | 31 |

| 27 | 22 | |

| 814 | 10 | |

| 1531 | 13 | |

| >31 | 23 | |

| Active medications | <8 | 26 |

| 811 | 26 | |

| 1218 | 26 | |

| >18 | 23 | |

Rates of agreement between handoff pairs, stratified by attending versus clinician, are shown in Table 3. Overall mean levels of agreement ranged from 0.41 to 0.87 (median 0.77). Except for the ratio of pulmonary to systemic blood flow question, there were no significant differences in agreement between attendings as compared to clinicians. When this analysis was repeated with unique sender‐receiver pair as the unit of analysis to account for within‐pair clustering, we obtained qualitatively similar results (data not shown).

| PKAT Item | Agreement Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attending Physician Pair | Clinician Pair | Pa | |||

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | ||

| |||||

| Clinical condition | 0.71 | 0.620.81 | 0.78 | 0.690.87 | 0.31 |

| Cardiovascular plan | 0.76 | 0.670.85 | 0.68 | 0.580.78 | 0.25 |

| Respiratory plan | 0.67 | 0.580.78 | 0.76 | 0.670.85 | 0.26 |

| Source of pulmonary blood flow | 0.83 | 0.750.91 | 0.87 | 0.800.94 | 0.53 |

| Ratio of pulmonary to systemic flow | 0.67 | 0.570.77 | 0.41 | 0.310.51 | <0.01 |

| Anticoagulation indication | 0.79 | 0.700.87 | 0.77 | 0.680.86 | 0.72 |

| Active cardiovascular issues | 0.87 | 0.800.94 | 0.76 | 0.670.85 | 0.06 |

| Active noncardiovascular issues | 0.80 | 0.720.88 | 0.78 | 0.690.87 | 0.72 |

Both length of stay and increasing number of medications affected agreement levels for PKAT items (Table 4). Increasing length of stay correlated directly with agreement on cardiovascular plan and ratio of pulmonary to systemic flow and inversely with indication for anticoagulation. Increasing number of medications had an inverse correlation with agreement on indication for anticoagulation, active cardiovascular issues, and active noncardiovascular issues.

| Item | CICU LOS | No. of Active Medications | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Day (n=56) | 27 Days (n=40) | 814 Days (n=18) | 1531 Days (n=24) | >31 Days (n=42) | Pa | 8 (n=46) | 811 (n=46) | 1218 (n=46) | >18 (n=42) | Pa | |

| |||||||||||

| Clinical condition | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.32 |

| Cardiovascular plan | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.86 | <0.01 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.81 | 0.16 |

| Respiratory plan | 0.68 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.68 |

| Source of pulmonary blood flow | 0.93 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.22 |

| Ratio of pulmonary to systemic flow | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.67 | 0.06 |

| Anticoagulation indication | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.60 | <0.01 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.62 | <0.01 |

| Active cardiovascular issues | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.92 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.87 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 0.55 | <0.01 |

| Active noncardiovascular issues | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.52 | <0.01 |

In contrast, there were no significant differences in item agreement levels based on provider characteristics, including experience, handoff education, prehandoff preparation, or continuity (data not shown).

CONCLUSIONS