User login

Ancillary Testing for Rotavirus

Rotavirus gastroenteritis (RGE) accounts for approximately 70,000 pediatric hospitalizations annually in the United States.1 Costly microbiological assays are frequently performed in these patients to exclude concurrent serious bacterial infection (SBI), though the actual incidence of SBI is quite low.28 Our objectives were to describe the incidence of SBI in children evaluated at a community hospital and subsequently diagnosed with laboratory‐confirmed RGE and to determine whether ancillary testing was associated with prolonged length of stay (LOS) in hospitalized patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Albert Einstein Medical Center (AEMC, Philadelphia, PA) and approved by the AEMC institutional review board. During the study period, there were approximately 20,000 pediatric outpatient evaluations and 2000 pediatric hospitalizations per year.

Participants, Study Protocol, and Data Collection

Children under 18 years of age were included if they were evaluated in the pediatric clinic, emergency department (ED), or admitted to the pediatric floor at AEMC between January 1, 1998 and May 31, 2003 and tested positive for stool rotavirus antigen. Study patients were identified using 3 methods: first, International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) discharge diagnosis code for enteritis due to rotavirus (ICD‐9‐CM, 008.61); then, pediatric ward admission logs identified gastroenteritis patients; and finally, review of microbiology laboratory records confirmed the presence of a positive stool rotavirus antigen test. Patients with nosocomial RGE, defined by gastroenteritis symptoms manifesting 3 or more days after hospitalization, were excluded.

Study Definitions

Prolonged LOS was defined as hospitalization of 3 days as this value represented the 75th percentile for LOS in our cohort. Patients discharged directly from the ED were classified as not having a prolonged LOS. Bacteremia was defined as isolation of a known bacterial pathogen from blood culture, excluding isolates that reflected commensal skin flora. Fever was defined as temperature >38.0C. Tachypnea and tachycardia were defined using previously published age‐specific definitions.9 Bacterial meningitis required isolation of a bacterial pathogen from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or, in patients who received antibiotics prior to evaluation, the combination of CSF pleocytosis (defined as white blood cell count 8/mm3) and bacteria detectable on CSF Gram stain. Urinary tract infection was defined as growth of a single pathogen yielding 50,000 colony forming units (cfu)/mL from a catheterized specimen. Significant past medical history constituted any preexisting medical diagnosis.

Stool samples were assayed for rotaviral antigen by means of ImmunoCard STAT! Rotavirus (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, OH). Abstracted data was entered onto standardized data collection forms and included demographic identifiers, clinical presentation, past medical history, laboratory investigations, and subsequent hospital course.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA version 9.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Categorical variables were described using counts and percentages. Continuous variables were described using median and interquartile range (IQR) values. Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine the association between potential risk factors and prolonged LOS. Categorical values were compared using either the 2 or the Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared with the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test. Adjusted analyses, using logistic regression, were then performed to identify factors independently associated with prolonged LOS. Variables with a P‐value <0.2 were considered for inclusion in the multivariable model. Candidate variables were entered into the model using a purposeful selection approach and included in the final multivariable model if they remained significant on adjusted analysis or if they were involved in confounding. Confounding was assumed to be present if adjustment for a variable produced an odds ratio (OR) that was >15% different than the unadjusted OR. Since prolonged LOS was defined as LOS >75th percentile for the cohort, we had 80% power (alpha = 0.05) to detect an OR of 4 or more for variables with a prevalence of 40% or greater in the study cohort.

Results

One hundred cases of RGE were initially identified; 6 patients were excluded4 with negative rotavirus stool antigen tests and 2 because the infection was nosocomially‐acquired. The remaining 94 cases were included in the analysis. Fifty‐eight (61.7%) of the patients were male, and 80 (85.1%) were African‐American. The median age was 8 months (IQR, 1 month to 16 years) and 83 patients (88.3%) were admitted to hospital. Fifty patients (53.2%) were febrile at presentation. The median length of stay was 2 days (IQR, 1‐3 days).

There were no patients with SBI (95% confidence interval [CI], 0%‐3.8%). Ten patients (12%) had received antibiotics in the 72 hours prior to evaluation; 6 of these 10 patients had blood cultures obtained. Peripheral blood cultures were drawn from 47 patients (50%). Of these, 43 (91.5%) were negative. Three cultures yielded viridans group streptococci, and 1 culture yielded vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus species (VRE). The cultures yielding viridans group streptococci were drawn from 3 infants aged 42 days, 4 months, and 12 months. All 3 infants were febrile at presentation. In 2 of the 3 infants, 2 sets of blood cultures were drawn and viridans group streptococci was isolated from only 1 of the 2 cultures. The third infant made a rapid clinical recovery without antibiotic intervention and was discharged in less than 48 hours, belying microbiological evidence of bacteremia. Therefore, we classified all 3 viridans group streptococci cultures as contaminated specimens. The difference in the frequency with which blood cultures were performed in children younger than (59%) or older than (44%) 6 months of age was not statistically significant (2, P = 0.143).

The patient with VRE isolated from blood culture was a 4‐month‐old male who presented with 2 days of vomiting and diarrhea and a fever to 38.7C. The VRE culture, while potentially representing bacterial translocation in the setting of RGE, was presumed to be a contaminant when a repeat peripheral culture was negative. The patient had received amoxicillin for the treatment of otitis media prior to presentation and acquisition of cultures. The susceptibility testing results for ampicillin or amoxicillin were not available; however, the patient did not receive antibiotics for treatment of the VRE blood culture isolate.

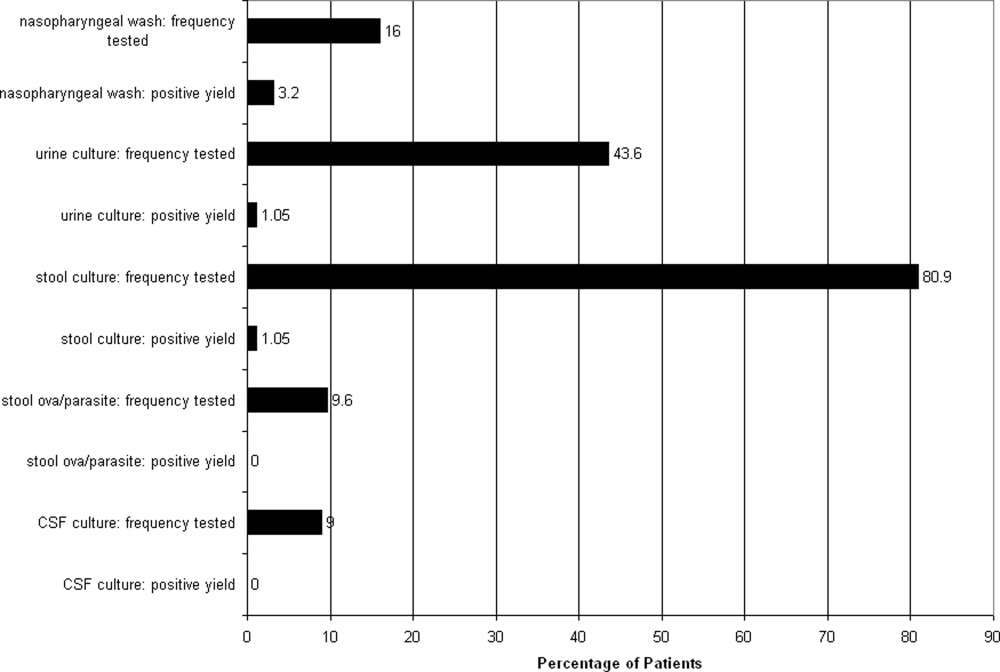

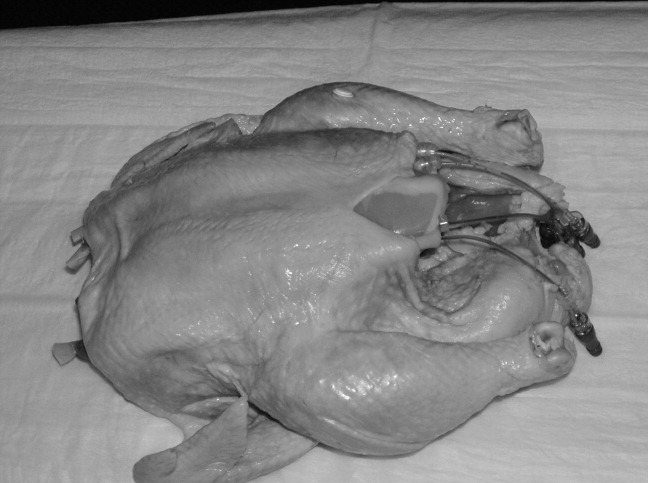

Multiple microbiological assays were performed (Figure 1). Many of the detected organisms were considered nonpathogenic. Stool bacterial cultures were obtained in 76 patients (80.9%) with only 1 (1.3%) positive isolate, Proteus mirabilis, considered nonpathogenic. Urine cultures from 41 patients (43.6%) yielded only 1 (2.4%) positive result, Staphylococcus aureus, deemed a contaminant. Nasopharyngeal washes from 15 patients (16%) revealed 3 (20%) positive results (respiratory syncytial virus in 2 patients and influenza virus in 1). Stool assayed for ova and parasites in 9 patients (9.6%) was negative. CSF cultured in 9 patients was also negative, although 3 samples demonstrated pleocytosis. Nonmicrobiological assays included 4 normal chest radiographs, 2 normal urinalyses, and 3 arterial blood gases revealing metabolic acidosis.

A complete blood count was obtained in 77 patients (81.9%). The median peripheral white blood cell count was 8800/mm3 (IQR, 6800 to 11,800). There were no differences between those with and without prolonged LOS on univariate analysis with regard to vital signs or initial symptoms such as tachypnea, fever, tachycardia, or other features associated with illness severity (eg, extent of dehydration). There were no differences in hematological or chemical parameters or with the performance of any other testing. In bivariate analyses, age 6 months (unadjusted OR, 3.43; 95% CI, 1.26‐9.50; P < 0.01) and collection of peripheral blood culture (OR, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.13‐8.98; P < 0.01) were associated with prolonged LOS. Other variables considered for inclusion in the multivariable model included duration of symptoms, presence of a preexisting medical condition, and performance of a nasopharyngeal wash for respiratory virus detection. In multivariable analysis, age <6 months (adjusted OR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.17‐7.74; P = 0.022) and the performance of a blood culture (adjusted OR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.03‐7.13; P = 0.043) were independently associated with a prolonged LOS.

Discussion

The absence of SBI in our relatively small cohort of children admitted to a community hospital with laboratory‐confirmed RGE supports earlier estimates of an incidence of less than 1%,5, 7 an incidence similar to that of occult bacteremia in febrile children 2 to 36 months of age following introduction of the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in 2000.10, 11 We found 13 cases reported in the English literature (Table 1). Several salient features are noted when comparing these case reports. All cases of SBI following laboratory‐confirmed RGE were characterized by the development of a second fever after the resolution of initial symptoms. These fevers presented at a mean day of hospitalization of 2.8 (range, 2‐5). Second fevers were high (mean, 39.2C; range, 38.2C to 40C). Cultures obtained other than peripheral blood cultures were only positive in 1 patient; this patient also had cellulitis and Escherichia coli was isolated from both blood and wound cultures.3 One of the reported children with bacteremia died, 2 cases of SBI following RGE were complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and 1 case by acute renal failure. Enterobacter cloacae (n = 4) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 3) were the most commonly isolated organisms from peripheral blood culture.

| References | Age (months)/Sex | Hospital day of bacteremia | Second fever (C)* | Organism Cultured from Peripheral Blood | Other Culture Results | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Adler et al.2 | 9/♂ | 3 | 39.5 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | None | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Adler et al.2 | 9/♂ | 2 | 40 | Escherichia coli | None | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Adler et al.2 | 0.74/♀ | 3 | 39 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Urine, CSF cultures negative | ARF, resolved to full recovery |

| Carneiro et al.4 | 10/♀ | 3 | 39.1 | ESBL‐producing Escherichia coli | Wound culture (cellulitis) from day 3 in PICU yielded ESBL‐producing Escherichia coli | Full recovery after DIC and transfer to PICU |

| Cicchetti et al.3 | 18/♂ | 2 | high | Pantoea agglomerans | None | DIC resolved with Protein C concentrate infusions |

| Gonzalez‐Carretero et al.5 | 1.5/♂ | 3 | 39.3 | Streptococcus viridans | Urine, CSF cultures negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Gonzalez‐Carretero et al.5 | 10/♂ | 5 | 38.3 | Enterobacter cloacae | Stool culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Kashiwagi et al.6 | 12/♂ | 7 | 38.0 | Klebsiella oxytoca | Not reported | Died |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 6/♂ | 3 | 40 | Enterobacter cloacae | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 4/♀ | 2 | 39.5 | Enterobacter cloacae | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course without antibiotic therapy |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 0.5/♀ | 3 | 38.2 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | CSF and urine cultures negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 13/♀ | 2 | 39.3 | Enterobacter cloacae | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Mel et. al8 | 16/♀ | 5 | 39.8 | ESBL‐producing Escherichia coli | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

Many children in our study had ancillary laboratory testing performed. The results of these tests were typically normal and rarely affected clinical management in a positive manner. Bacteria and parasites are relatively rare causes of gastroenteritis in the United States in comparison with rotavirus, particularly during the winter months. However, stool was sent for bacterial culture in over 80% of patients and for ova and parasite detection in almost 10% of patients ultimately diagnosed with RGE. Furthermore, despite the relatively low prevalence of bacteremia since licensure of the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, a majority of children had a complete blood count performed while one‐half also had blood obtained for culture. In our cohort, children 6 months and younger and those from whom a blood culture was collected were at an increased risk for prolonged LOS. It was not clear from medical record review whether children with prolonged LOS were kept in the hospital longer for the sole purpose of awaiting the results of blood cultures.

SBI rarely occurs in the context of RGE. While secondary fever seems to be a common manifestation, the sensitivity of secondary fever as a marker for SBI after RGE in this population is unknown. However, given the very low incidence, the potentially serious complications of SBI following laboratory confirmed RGE, and the likely successful management of these complications in the hospital setting, slightly longer hospitalizations for children under 1 year of age must be weighed against earlier discharges with instructions from clinicians to caregivers for careful monitoring of fever and outpatient follow‐up shortly after discharge.

This study has several limitations. First, the timing of the availability of the results of rotavirus antigen testing is not known. It is possible that the rapid availability of rotavirus test results in some circumstances encouraged clinicians to abandon tests seeking other sources of infection. Conversely, children with gastroenteritis in the context of a concurrent bacterial infection may have been less likely to undergo rotavirus stool antigen testing. This latter possibility would bias our findings toward underestimating the prevalence of concurrent bacterial infection among children with RGE. Second, this study was performed prior to licensure and widespread use of the currently‐licensed vaccine against rotavirus (Rotateq; Merck and Company, Whitehouse Station, NJ). Reductions in the burden of gastroenteritis caused by rotavirus may have a much more dramatic impact on resource utilization in the treatment of gastroenteritis than reductions in ancillary testing. Finally, this study was performed at a single urban community hospital and therefore cannot be generalized to other settings such as academic tertiary care centers. Furthermore, test ordering patterns may be local or regional and other community hospitals may exhibit different patterns. Further clarification of the role of ancillary testing in children presenting with diarrhea during the winter months is warranted since reducing the extent of such testing would dramatically reduce resource utilization for this illness. Finally, a blood culture was not obtained from all patients. Therefore, occult bacteremia attributable to RGE could not be detected. Since no patient in our study underwent subsequent clinical deterioration, we presume that any case of occult bacteremia resolved spontaneously and was not of clinical consequence, although such occurrences would cause us to underestimate the prevalence of SBI in this population.

Resource utilization in our cohort was high, while yield from microbiological investigations was low. This finding challenges the need to perform invasive, costly assays to exclude concurrent SBI in this population. It is possible that children with viral gastroenteritis caused by pathogens other than rotavirus are also at low risk of SBI. However, the diagnostic strategy that best identifies patients at risk for SBI following acute gastroenteritis is unknown. Further studies are needed to determine an ideal clinical approach to the infant with RGE.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalizations associated with rotavirus gastroenteritis in the United States, 1993‐2002.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(6):489–493.

- ,,,.Enteric gram‐negative sepsis complicating rotavirus gastroenteritis in previously healthy infants.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2005;44(4):351–354.

- ,,, et al.Septic shock complicating acute rotavirus‐associated diarrhea.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(6):571–572.

- ,,,,,.Pantoea agglomerans sepsis after rotavirus gastroenteritis.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(3):280–281.

- ,,.Rotavirus gastroenteritis leading to secondary bacteremia in previously healthy infants.Pediatrics.2006;118(5):2255–2256; author reply2256–2257.

- ,,, et al.Klebsiella oxytoca septicemia complicating rotavirus‐associated acute diarrhea.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2007;26(2):191–192.

- ,,,,.Secondary bacteremia after rotavirus gastroenteritis in infancy.Pediatrics.2006;117(1):224–226.

- ,,,.Extended spectrum beta‐lactamase‐positive Escherichia coli bacteremia complicating rotavirus gastroenteritis.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(10):962.

- ,,,.The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics.Philadelphia:Lippincott Williams and Wilkins;2005.

- ,,, et al.Changing epidemiology of outpatient bacteremia in 3‐ to 36‐month‐old children after the introduction of the heptavalent‐conjugated pneumococcal vaccine.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(4):293–300.

- ,.Incidence of occult bacteremia among highly febrile young children in the era of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a study from a Children's Hospital Emergency Department and Urgent Care Center.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2004;158(7):671–675.

Rotavirus gastroenteritis (RGE) accounts for approximately 70,000 pediatric hospitalizations annually in the United States.1 Costly microbiological assays are frequently performed in these patients to exclude concurrent serious bacterial infection (SBI), though the actual incidence of SBI is quite low.28 Our objectives were to describe the incidence of SBI in children evaluated at a community hospital and subsequently diagnosed with laboratory‐confirmed RGE and to determine whether ancillary testing was associated with prolonged length of stay (LOS) in hospitalized patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Albert Einstein Medical Center (AEMC, Philadelphia, PA) and approved by the AEMC institutional review board. During the study period, there were approximately 20,000 pediatric outpatient evaluations and 2000 pediatric hospitalizations per year.

Participants, Study Protocol, and Data Collection

Children under 18 years of age were included if they were evaluated in the pediatric clinic, emergency department (ED), or admitted to the pediatric floor at AEMC between January 1, 1998 and May 31, 2003 and tested positive for stool rotavirus antigen. Study patients were identified using 3 methods: first, International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) discharge diagnosis code for enteritis due to rotavirus (ICD‐9‐CM, 008.61); then, pediatric ward admission logs identified gastroenteritis patients; and finally, review of microbiology laboratory records confirmed the presence of a positive stool rotavirus antigen test. Patients with nosocomial RGE, defined by gastroenteritis symptoms manifesting 3 or more days after hospitalization, were excluded.

Study Definitions

Prolonged LOS was defined as hospitalization of 3 days as this value represented the 75th percentile for LOS in our cohort. Patients discharged directly from the ED were classified as not having a prolonged LOS. Bacteremia was defined as isolation of a known bacterial pathogen from blood culture, excluding isolates that reflected commensal skin flora. Fever was defined as temperature >38.0C. Tachypnea and tachycardia were defined using previously published age‐specific definitions.9 Bacterial meningitis required isolation of a bacterial pathogen from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or, in patients who received antibiotics prior to evaluation, the combination of CSF pleocytosis (defined as white blood cell count 8/mm3) and bacteria detectable on CSF Gram stain. Urinary tract infection was defined as growth of a single pathogen yielding 50,000 colony forming units (cfu)/mL from a catheterized specimen. Significant past medical history constituted any preexisting medical diagnosis.

Stool samples were assayed for rotaviral antigen by means of ImmunoCard STAT! Rotavirus (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, OH). Abstracted data was entered onto standardized data collection forms and included demographic identifiers, clinical presentation, past medical history, laboratory investigations, and subsequent hospital course.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA version 9.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Categorical variables were described using counts and percentages. Continuous variables were described using median and interquartile range (IQR) values. Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine the association between potential risk factors and prolonged LOS. Categorical values were compared using either the 2 or the Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared with the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test. Adjusted analyses, using logistic regression, were then performed to identify factors independently associated with prolonged LOS. Variables with a P‐value <0.2 were considered for inclusion in the multivariable model. Candidate variables were entered into the model using a purposeful selection approach and included in the final multivariable model if they remained significant on adjusted analysis or if they were involved in confounding. Confounding was assumed to be present if adjustment for a variable produced an odds ratio (OR) that was >15% different than the unadjusted OR. Since prolonged LOS was defined as LOS >75th percentile for the cohort, we had 80% power (alpha = 0.05) to detect an OR of 4 or more for variables with a prevalence of 40% or greater in the study cohort.

Results

One hundred cases of RGE were initially identified; 6 patients were excluded4 with negative rotavirus stool antigen tests and 2 because the infection was nosocomially‐acquired. The remaining 94 cases were included in the analysis. Fifty‐eight (61.7%) of the patients were male, and 80 (85.1%) were African‐American. The median age was 8 months (IQR, 1 month to 16 years) and 83 patients (88.3%) were admitted to hospital. Fifty patients (53.2%) were febrile at presentation. The median length of stay was 2 days (IQR, 1‐3 days).

There were no patients with SBI (95% confidence interval [CI], 0%‐3.8%). Ten patients (12%) had received antibiotics in the 72 hours prior to evaluation; 6 of these 10 patients had blood cultures obtained. Peripheral blood cultures were drawn from 47 patients (50%). Of these, 43 (91.5%) were negative. Three cultures yielded viridans group streptococci, and 1 culture yielded vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus species (VRE). The cultures yielding viridans group streptococci were drawn from 3 infants aged 42 days, 4 months, and 12 months. All 3 infants were febrile at presentation. In 2 of the 3 infants, 2 sets of blood cultures were drawn and viridans group streptococci was isolated from only 1 of the 2 cultures. The third infant made a rapid clinical recovery without antibiotic intervention and was discharged in less than 48 hours, belying microbiological evidence of bacteremia. Therefore, we classified all 3 viridans group streptococci cultures as contaminated specimens. The difference in the frequency with which blood cultures were performed in children younger than (59%) or older than (44%) 6 months of age was not statistically significant (2, P = 0.143).

The patient with VRE isolated from blood culture was a 4‐month‐old male who presented with 2 days of vomiting and diarrhea and a fever to 38.7C. The VRE culture, while potentially representing bacterial translocation in the setting of RGE, was presumed to be a contaminant when a repeat peripheral culture was negative. The patient had received amoxicillin for the treatment of otitis media prior to presentation and acquisition of cultures. The susceptibility testing results for ampicillin or amoxicillin were not available; however, the patient did not receive antibiotics for treatment of the VRE blood culture isolate.

Multiple microbiological assays were performed (Figure 1). Many of the detected organisms were considered nonpathogenic. Stool bacterial cultures were obtained in 76 patients (80.9%) with only 1 (1.3%) positive isolate, Proteus mirabilis, considered nonpathogenic. Urine cultures from 41 patients (43.6%) yielded only 1 (2.4%) positive result, Staphylococcus aureus, deemed a contaminant. Nasopharyngeal washes from 15 patients (16%) revealed 3 (20%) positive results (respiratory syncytial virus in 2 patients and influenza virus in 1). Stool assayed for ova and parasites in 9 patients (9.6%) was negative. CSF cultured in 9 patients was also negative, although 3 samples demonstrated pleocytosis. Nonmicrobiological assays included 4 normal chest radiographs, 2 normal urinalyses, and 3 arterial blood gases revealing metabolic acidosis.

A complete blood count was obtained in 77 patients (81.9%). The median peripheral white blood cell count was 8800/mm3 (IQR, 6800 to 11,800). There were no differences between those with and without prolonged LOS on univariate analysis with regard to vital signs or initial symptoms such as tachypnea, fever, tachycardia, or other features associated with illness severity (eg, extent of dehydration). There were no differences in hematological or chemical parameters or with the performance of any other testing. In bivariate analyses, age 6 months (unadjusted OR, 3.43; 95% CI, 1.26‐9.50; P < 0.01) and collection of peripheral blood culture (OR, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.13‐8.98; P < 0.01) were associated with prolonged LOS. Other variables considered for inclusion in the multivariable model included duration of symptoms, presence of a preexisting medical condition, and performance of a nasopharyngeal wash for respiratory virus detection. In multivariable analysis, age <6 months (adjusted OR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.17‐7.74; P = 0.022) and the performance of a blood culture (adjusted OR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.03‐7.13; P = 0.043) were independently associated with a prolonged LOS.

Discussion

The absence of SBI in our relatively small cohort of children admitted to a community hospital with laboratory‐confirmed RGE supports earlier estimates of an incidence of less than 1%,5, 7 an incidence similar to that of occult bacteremia in febrile children 2 to 36 months of age following introduction of the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in 2000.10, 11 We found 13 cases reported in the English literature (Table 1). Several salient features are noted when comparing these case reports. All cases of SBI following laboratory‐confirmed RGE were characterized by the development of a second fever after the resolution of initial symptoms. These fevers presented at a mean day of hospitalization of 2.8 (range, 2‐5). Second fevers were high (mean, 39.2C; range, 38.2C to 40C). Cultures obtained other than peripheral blood cultures were only positive in 1 patient; this patient also had cellulitis and Escherichia coli was isolated from both blood and wound cultures.3 One of the reported children with bacteremia died, 2 cases of SBI following RGE were complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and 1 case by acute renal failure. Enterobacter cloacae (n = 4) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 3) were the most commonly isolated organisms from peripheral blood culture.

| References | Age (months)/Sex | Hospital day of bacteremia | Second fever (C)* | Organism Cultured from Peripheral Blood | Other Culture Results | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Adler et al.2 | 9/♂ | 3 | 39.5 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | None | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Adler et al.2 | 9/♂ | 2 | 40 | Escherichia coli | None | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Adler et al.2 | 0.74/♀ | 3 | 39 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Urine, CSF cultures negative | ARF, resolved to full recovery |

| Carneiro et al.4 | 10/♀ | 3 | 39.1 | ESBL‐producing Escherichia coli | Wound culture (cellulitis) from day 3 in PICU yielded ESBL‐producing Escherichia coli | Full recovery after DIC and transfer to PICU |

| Cicchetti et al.3 | 18/♂ | 2 | high | Pantoea agglomerans | None | DIC resolved with Protein C concentrate infusions |

| Gonzalez‐Carretero et al.5 | 1.5/♂ | 3 | 39.3 | Streptococcus viridans | Urine, CSF cultures negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Gonzalez‐Carretero et al.5 | 10/♂ | 5 | 38.3 | Enterobacter cloacae | Stool culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Kashiwagi et al.6 | 12/♂ | 7 | 38.0 | Klebsiella oxytoca | Not reported | Died |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 6/♂ | 3 | 40 | Enterobacter cloacae | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 4/♀ | 2 | 39.5 | Enterobacter cloacae | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course without antibiotic therapy |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 0.5/♀ | 3 | 38.2 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | CSF and urine cultures negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 13/♀ | 2 | 39.3 | Enterobacter cloacae | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Mel et. al8 | 16/♀ | 5 | 39.8 | ESBL‐producing Escherichia coli | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

Many children in our study had ancillary laboratory testing performed. The results of these tests were typically normal and rarely affected clinical management in a positive manner. Bacteria and parasites are relatively rare causes of gastroenteritis in the United States in comparison with rotavirus, particularly during the winter months. However, stool was sent for bacterial culture in over 80% of patients and for ova and parasite detection in almost 10% of patients ultimately diagnosed with RGE. Furthermore, despite the relatively low prevalence of bacteremia since licensure of the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, a majority of children had a complete blood count performed while one‐half also had blood obtained for culture. In our cohort, children 6 months and younger and those from whom a blood culture was collected were at an increased risk for prolonged LOS. It was not clear from medical record review whether children with prolonged LOS were kept in the hospital longer for the sole purpose of awaiting the results of blood cultures.

SBI rarely occurs in the context of RGE. While secondary fever seems to be a common manifestation, the sensitivity of secondary fever as a marker for SBI after RGE in this population is unknown. However, given the very low incidence, the potentially serious complications of SBI following laboratory confirmed RGE, and the likely successful management of these complications in the hospital setting, slightly longer hospitalizations for children under 1 year of age must be weighed against earlier discharges with instructions from clinicians to caregivers for careful monitoring of fever and outpatient follow‐up shortly after discharge.

This study has several limitations. First, the timing of the availability of the results of rotavirus antigen testing is not known. It is possible that the rapid availability of rotavirus test results in some circumstances encouraged clinicians to abandon tests seeking other sources of infection. Conversely, children with gastroenteritis in the context of a concurrent bacterial infection may have been less likely to undergo rotavirus stool antigen testing. This latter possibility would bias our findings toward underestimating the prevalence of concurrent bacterial infection among children with RGE. Second, this study was performed prior to licensure and widespread use of the currently‐licensed vaccine against rotavirus (Rotateq; Merck and Company, Whitehouse Station, NJ). Reductions in the burden of gastroenteritis caused by rotavirus may have a much more dramatic impact on resource utilization in the treatment of gastroenteritis than reductions in ancillary testing. Finally, this study was performed at a single urban community hospital and therefore cannot be generalized to other settings such as academic tertiary care centers. Furthermore, test ordering patterns may be local or regional and other community hospitals may exhibit different patterns. Further clarification of the role of ancillary testing in children presenting with diarrhea during the winter months is warranted since reducing the extent of such testing would dramatically reduce resource utilization for this illness. Finally, a blood culture was not obtained from all patients. Therefore, occult bacteremia attributable to RGE could not be detected. Since no patient in our study underwent subsequent clinical deterioration, we presume that any case of occult bacteremia resolved spontaneously and was not of clinical consequence, although such occurrences would cause us to underestimate the prevalence of SBI in this population.

Resource utilization in our cohort was high, while yield from microbiological investigations was low. This finding challenges the need to perform invasive, costly assays to exclude concurrent SBI in this population. It is possible that children with viral gastroenteritis caused by pathogens other than rotavirus are also at low risk of SBI. However, the diagnostic strategy that best identifies patients at risk for SBI following acute gastroenteritis is unknown. Further studies are needed to determine an ideal clinical approach to the infant with RGE.

Rotavirus gastroenteritis (RGE) accounts for approximately 70,000 pediatric hospitalizations annually in the United States.1 Costly microbiological assays are frequently performed in these patients to exclude concurrent serious bacterial infection (SBI), though the actual incidence of SBI is quite low.28 Our objectives were to describe the incidence of SBI in children evaluated at a community hospital and subsequently diagnosed with laboratory‐confirmed RGE and to determine whether ancillary testing was associated with prolonged length of stay (LOS) in hospitalized patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Albert Einstein Medical Center (AEMC, Philadelphia, PA) and approved by the AEMC institutional review board. During the study period, there were approximately 20,000 pediatric outpatient evaluations and 2000 pediatric hospitalizations per year.

Participants, Study Protocol, and Data Collection

Children under 18 years of age were included if they were evaluated in the pediatric clinic, emergency department (ED), or admitted to the pediatric floor at AEMC between January 1, 1998 and May 31, 2003 and tested positive for stool rotavirus antigen. Study patients were identified using 3 methods: first, International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) discharge diagnosis code for enteritis due to rotavirus (ICD‐9‐CM, 008.61); then, pediatric ward admission logs identified gastroenteritis patients; and finally, review of microbiology laboratory records confirmed the presence of a positive stool rotavirus antigen test. Patients with nosocomial RGE, defined by gastroenteritis symptoms manifesting 3 or more days after hospitalization, were excluded.

Study Definitions

Prolonged LOS was defined as hospitalization of 3 days as this value represented the 75th percentile for LOS in our cohort. Patients discharged directly from the ED were classified as not having a prolonged LOS. Bacteremia was defined as isolation of a known bacterial pathogen from blood culture, excluding isolates that reflected commensal skin flora. Fever was defined as temperature >38.0C. Tachypnea and tachycardia were defined using previously published age‐specific definitions.9 Bacterial meningitis required isolation of a bacterial pathogen from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or, in patients who received antibiotics prior to evaluation, the combination of CSF pleocytosis (defined as white blood cell count 8/mm3) and bacteria detectable on CSF Gram stain. Urinary tract infection was defined as growth of a single pathogen yielding 50,000 colony forming units (cfu)/mL from a catheterized specimen. Significant past medical history constituted any preexisting medical diagnosis.

Stool samples were assayed for rotaviral antigen by means of ImmunoCard STAT! Rotavirus (Meridian Bioscience, Cincinnati, OH). Abstracted data was entered onto standardized data collection forms and included demographic identifiers, clinical presentation, past medical history, laboratory investigations, and subsequent hospital course.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA version 9.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Categorical variables were described using counts and percentages. Continuous variables were described using median and interquartile range (IQR) values. Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine the association between potential risk factors and prolonged LOS. Categorical values were compared using either the 2 or the Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared with the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test. Adjusted analyses, using logistic regression, were then performed to identify factors independently associated with prolonged LOS. Variables with a P‐value <0.2 were considered for inclusion in the multivariable model. Candidate variables were entered into the model using a purposeful selection approach and included in the final multivariable model if they remained significant on adjusted analysis or if they were involved in confounding. Confounding was assumed to be present if adjustment for a variable produced an odds ratio (OR) that was >15% different than the unadjusted OR. Since prolonged LOS was defined as LOS >75th percentile for the cohort, we had 80% power (alpha = 0.05) to detect an OR of 4 or more for variables with a prevalence of 40% or greater in the study cohort.

Results

One hundred cases of RGE were initially identified; 6 patients were excluded4 with negative rotavirus stool antigen tests and 2 because the infection was nosocomially‐acquired. The remaining 94 cases were included in the analysis. Fifty‐eight (61.7%) of the patients were male, and 80 (85.1%) were African‐American. The median age was 8 months (IQR, 1 month to 16 years) and 83 patients (88.3%) were admitted to hospital. Fifty patients (53.2%) were febrile at presentation. The median length of stay was 2 days (IQR, 1‐3 days).

There were no patients with SBI (95% confidence interval [CI], 0%‐3.8%). Ten patients (12%) had received antibiotics in the 72 hours prior to evaluation; 6 of these 10 patients had blood cultures obtained. Peripheral blood cultures were drawn from 47 patients (50%). Of these, 43 (91.5%) were negative. Three cultures yielded viridans group streptococci, and 1 culture yielded vancomycin‐resistant Enterococcus species (VRE). The cultures yielding viridans group streptococci were drawn from 3 infants aged 42 days, 4 months, and 12 months. All 3 infants were febrile at presentation. In 2 of the 3 infants, 2 sets of blood cultures were drawn and viridans group streptococci was isolated from only 1 of the 2 cultures. The third infant made a rapid clinical recovery without antibiotic intervention and was discharged in less than 48 hours, belying microbiological evidence of bacteremia. Therefore, we classified all 3 viridans group streptococci cultures as contaminated specimens. The difference in the frequency with which blood cultures were performed in children younger than (59%) or older than (44%) 6 months of age was not statistically significant (2, P = 0.143).

The patient with VRE isolated from blood culture was a 4‐month‐old male who presented with 2 days of vomiting and diarrhea and a fever to 38.7C. The VRE culture, while potentially representing bacterial translocation in the setting of RGE, was presumed to be a contaminant when a repeat peripheral culture was negative. The patient had received amoxicillin for the treatment of otitis media prior to presentation and acquisition of cultures. The susceptibility testing results for ampicillin or amoxicillin were not available; however, the patient did not receive antibiotics for treatment of the VRE blood culture isolate.

Multiple microbiological assays were performed (Figure 1). Many of the detected organisms were considered nonpathogenic. Stool bacterial cultures were obtained in 76 patients (80.9%) with only 1 (1.3%) positive isolate, Proteus mirabilis, considered nonpathogenic. Urine cultures from 41 patients (43.6%) yielded only 1 (2.4%) positive result, Staphylococcus aureus, deemed a contaminant. Nasopharyngeal washes from 15 patients (16%) revealed 3 (20%) positive results (respiratory syncytial virus in 2 patients and influenza virus in 1). Stool assayed for ova and parasites in 9 patients (9.6%) was negative. CSF cultured in 9 patients was also negative, although 3 samples demonstrated pleocytosis. Nonmicrobiological assays included 4 normal chest radiographs, 2 normal urinalyses, and 3 arterial blood gases revealing metabolic acidosis.

A complete blood count was obtained in 77 patients (81.9%). The median peripheral white blood cell count was 8800/mm3 (IQR, 6800 to 11,800). There were no differences between those with and without prolonged LOS on univariate analysis with regard to vital signs or initial symptoms such as tachypnea, fever, tachycardia, or other features associated with illness severity (eg, extent of dehydration). There were no differences in hematological or chemical parameters or with the performance of any other testing. In bivariate analyses, age 6 months (unadjusted OR, 3.43; 95% CI, 1.26‐9.50; P < 0.01) and collection of peripheral blood culture (OR, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.13‐8.98; P < 0.01) were associated with prolonged LOS. Other variables considered for inclusion in the multivariable model included duration of symptoms, presence of a preexisting medical condition, and performance of a nasopharyngeal wash for respiratory virus detection. In multivariable analysis, age <6 months (adjusted OR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.17‐7.74; P = 0.022) and the performance of a blood culture (adjusted OR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.03‐7.13; P = 0.043) were independently associated with a prolonged LOS.

Discussion

The absence of SBI in our relatively small cohort of children admitted to a community hospital with laboratory‐confirmed RGE supports earlier estimates of an incidence of less than 1%,5, 7 an incidence similar to that of occult bacteremia in febrile children 2 to 36 months of age following introduction of the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in 2000.10, 11 We found 13 cases reported in the English literature (Table 1). Several salient features are noted when comparing these case reports. All cases of SBI following laboratory‐confirmed RGE were characterized by the development of a second fever after the resolution of initial symptoms. These fevers presented at a mean day of hospitalization of 2.8 (range, 2‐5). Second fevers were high (mean, 39.2C; range, 38.2C to 40C). Cultures obtained other than peripheral blood cultures were only positive in 1 patient; this patient also had cellulitis and Escherichia coli was isolated from both blood and wound cultures.3 One of the reported children with bacteremia died, 2 cases of SBI following RGE were complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and 1 case by acute renal failure. Enterobacter cloacae (n = 4) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 3) were the most commonly isolated organisms from peripheral blood culture.

| References | Age (months)/Sex | Hospital day of bacteremia | Second fever (C)* | Organism Cultured from Peripheral Blood | Other Culture Results | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Adler et al.2 | 9/♂ | 3 | 39.5 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | None | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Adler et al.2 | 9/♂ | 2 | 40 | Escherichia coli | None | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Adler et al.2 | 0.74/♀ | 3 | 39 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Urine, CSF cultures negative | ARF, resolved to full recovery |

| Carneiro et al.4 | 10/♀ | 3 | 39.1 | ESBL‐producing Escherichia coli | Wound culture (cellulitis) from day 3 in PICU yielded ESBL‐producing Escherichia coli | Full recovery after DIC and transfer to PICU |

| Cicchetti et al.3 | 18/♂ | 2 | high | Pantoea agglomerans | None | DIC resolved with Protein C concentrate infusions |

| Gonzalez‐Carretero et al.5 | 1.5/♂ | 3 | 39.3 | Streptococcus viridans | Urine, CSF cultures negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Gonzalez‐Carretero et al.5 | 10/♂ | 5 | 38.3 | Enterobacter cloacae | Stool culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Kashiwagi et al.6 | 12/♂ | 7 | 38.0 | Klebsiella oxytoca | Not reported | Died |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 6/♂ | 3 | 40 | Enterobacter cloacae | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 4/♀ | 2 | 39.5 | Enterobacter cloacae | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course without antibiotic therapy |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 0.5/♀ | 3 | 38.2 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | CSF and urine cultures negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Lowenthal et. al7 | 13/♀ | 2 | 39.3 | Enterobacter cloacae | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

| Mel et. al8 | 16/♀ | 5 | 39.8 | ESBL‐producing Escherichia coli | Urine culture negative | Full recovery after uncomplicated course |

Many children in our study had ancillary laboratory testing performed. The results of these tests were typically normal and rarely affected clinical management in a positive manner. Bacteria and parasites are relatively rare causes of gastroenteritis in the United States in comparison with rotavirus, particularly during the winter months. However, stool was sent for bacterial culture in over 80% of patients and for ova and parasite detection in almost 10% of patients ultimately diagnosed with RGE. Furthermore, despite the relatively low prevalence of bacteremia since licensure of the Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine, a majority of children had a complete blood count performed while one‐half also had blood obtained for culture. In our cohort, children 6 months and younger and those from whom a blood culture was collected were at an increased risk for prolonged LOS. It was not clear from medical record review whether children with prolonged LOS were kept in the hospital longer for the sole purpose of awaiting the results of blood cultures.

SBI rarely occurs in the context of RGE. While secondary fever seems to be a common manifestation, the sensitivity of secondary fever as a marker for SBI after RGE in this population is unknown. However, given the very low incidence, the potentially serious complications of SBI following laboratory confirmed RGE, and the likely successful management of these complications in the hospital setting, slightly longer hospitalizations for children under 1 year of age must be weighed against earlier discharges with instructions from clinicians to caregivers for careful monitoring of fever and outpatient follow‐up shortly after discharge.

This study has several limitations. First, the timing of the availability of the results of rotavirus antigen testing is not known. It is possible that the rapid availability of rotavirus test results in some circumstances encouraged clinicians to abandon tests seeking other sources of infection. Conversely, children with gastroenteritis in the context of a concurrent bacterial infection may have been less likely to undergo rotavirus stool antigen testing. This latter possibility would bias our findings toward underestimating the prevalence of concurrent bacterial infection among children with RGE. Second, this study was performed prior to licensure and widespread use of the currently‐licensed vaccine against rotavirus (Rotateq; Merck and Company, Whitehouse Station, NJ). Reductions in the burden of gastroenteritis caused by rotavirus may have a much more dramatic impact on resource utilization in the treatment of gastroenteritis than reductions in ancillary testing. Finally, this study was performed at a single urban community hospital and therefore cannot be generalized to other settings such as academic tertiary care centers. Furthermore, test ordering patterns may be local or regional and other community hospitals may exhibit different patterns. Further clarification of the role of ancillary testing in children presenting with diarrhea during the winter months is warranted since reducing the extent of such testing would dramatically reduce resource utilization for this illness. Finally, a blood culture was not obtained from all patients. Therefore, occult bacteremia attributable to RGE could not be detected. Since no patient in our study underwent subsequent clinical deterioration, we presume that any case of occult bacteremia resolved spontaneously and was not of clinical consequence, although such occurrences would cause us to underestimate the prevalence of SBI in this population.

Resource utilization in our cohort was high, while yield from microbiological investigations was low. This finding challenges the need to perform invasive, costly assays to exclude concurrent SBI in this population. It is possible that children with viral gastroenteritis caused by pathogens other than rotavirus are also at low risk of SBI. However, the diagnostic strategy that best identifies patients at risk for SBI following acute gastroenteritis is unknown. Further studies are needed to determine an ideal clinical approach to the infant with RGE.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalizations associated with rotavirus gastroenteritis in the United States, 1993‐2002.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(6):489–493.

- ,,,.Enteric gram‐negative sepsis complicating rotavirus gastroenteritis in previously healthy infants.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2005;44(4):351–354.

- ,,, et al.Septic shock complicating acute rotavirus‐associated diarrhea.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(6):571–572.

- ,,,,,.Pantoea agglomerans sepsis after rotavirus gastroenteritis.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(3):280–281.

- ,,.Rotavirus gastroenteritis leading to secondary bacteremia in previously healthy infants.Pediatrics.2006;118(5):2255–2256; author reply2256–2257.

- ,,, et al.Klebsiella oxytoca septicemia complicating rotavirus‐associated acute diarrhea.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2007;26(2):191–192.

- ,,,,.Secondary bacteremia after rotavirus gastroenteritis in infancy.Pediatrics.2006;117(1):224–226.

- ,,,.Extended spectrum beta‐lactamase‐positive Escherichia coli bacteremia complicating rotavirus gastroenteritis.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(10):962.

- ,,,.The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics.Philadelphia:Lippincott Williams and Wilkins;2005.

- ,,, et al.Changing epidemiology of outpatient bacteremia in 3‐ to 36‐month‐old children after the introduction of the heptavalent‐conjugated pneumococcal vaccine.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(4):293–300.

- ,.Incidence of occult bacteremia among highly febrile young children in the era of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a study from a Children's Hospital Emergency Department and Urgent Care Center.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2004;158(7):671–675.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalizations associated with rotavirus gastroenteritis in the United States, 1993‐2002.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(6):489–493.

- ,,,.Enteric gram‐negative sepsis complicating rotavirus gastroenteritis in previously healthy infants.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2005;44(4):351–354.

- ,,, et al.Septic shock complicating acute rotavirus‐associated diarrhea.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(6):571–572.

- ,,,,,.Pantoea agglomerans sepsis after rotavirus gastroenteritis.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(3):280–281.

- ,,.Rotavirus gastroenteritis leading to secondary bacteremia in previously healthy infants.Pediatrics.2006;118(5):2255–2256; author reply2256–2257.

- ,,, et al.Klebsiella oxytoca septicemia complicating rotavirus‐associated acute diarrhea.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2007;26(2):191–192.

- ,,,,.Secondary bacteremia after rotavirus gastroenteritis in infancy.Pediatrics.2006;117(1):224–226.

- ,,,.Extended spectrum beta‐lactamase‐positive Escherichia coli bacteremia complicating rotavirus gastroenteritis.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(10):962.

- ,,,.The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics.Philadelphia:Lippincott Williams and Wilkins;2005.

- ,,, et al.Changing epidemiology of outpatient bacteremia in 3‐ to 36‐month‐old children after the introduction of the heptavalent‐conjugated pneumococcal vaccine.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2006;25(4):293–300.

- ,.Incidence of occult bacteremia among highly febrile young children in the era of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a study from a Children's Hospital Emergency Department and Urgent Care Center.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2004;158(7):671–675.

Copyright © 2009 Society of Hospital Medicine

New Therapies for UGH

Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (UGH) is a common cause of acute admission for hospitalization.13 However, recent advances in our understanding of erosive disease (ED) and peptic ulcer disease (PUD), 2 of the most common etiologies of UGH, have led to effective strategies to reduce the risk of UGH. Successful implementation of these strategies, such as treatment of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and selective cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors (COX‐2s) in place of traditional nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), may be able to significantly reduce rates of UGH caused by ED and PUD.47

Prior to these preventive treatments, PUD and ED, both acid‐related disorders, were the most common causes of UGH requiring admission to the hospital, accounting for 62% and 14% of all UGHs, respectively.2 Given the widespread treatment of H. pylori and use of PPIs and COX‐2s, we might expect that the distribution of etiologies of UGH may have changed. However, there are limited data on the distribution of etiologies of UGH in the era of effective preventive therapy.8 If the distribution of etiologies causing patients to present with UGH has fundamentally changed with these new treatments, established strategies of managing acute UGH may need to be reevaluated. Given that well‐established guidelines exist and that many hospitals use a protocol‐driven management strategy to decide on the need for admission and/or intensive care unit (ICU) admission, changes in the distribution of etiologies since the widespread use of these new pharmacologic approaches may affect the appropriateness of these protocols.9, 10 For example, if the eradication of H. pylori has dramatically reduced the proportion of UGH caused by PUD, then risk stratification studies developed when PUD was far more common may need to be revisited. This would be particularly important if bleeding from PUD was of significantly different severity than bleeding from other causes.

While patients with H. pylori‐related UGH from PUD should be treated for H. pylori eradication, several important questions remain surrounding the use of newer therapeutics that may mitigate the risk of UGH in some patients. It is unclear what proportion of patients admitted with UGH in this new era developed bleeding despite using preventive therapy. These treatment failures are known to occur, but it is not well known how much of the burden of UGH today is due to this breakthrough bleeding.5, 6, 11, 12 Contrastingly, there are also patients who are admitted with UGH who are not on preventive treatment. Current guidelines suggest that high‐risk patients requiring NSAIDs be given COX‐2s or traditional NSAIDs with a PPI.1315 However, there is significant disagreement between these national guidelines about what constitutes a high‐risk profile.1315 For example, some guidelines recommend that elderly patients requiring NSAIDs should be on a PPI while others do not make that recommendation. Similarly, while prior UGH is a well‐recognized risk factor for future bleeding risk even without NSAIDs, current guidelines do not provide guidance toward the use of preventive therapy in these patients. If there are few patients who present with UGH related to acid disease that are not on a preventive therapy, then these unanswered questions or conflicts within current guidelines become less important. However, if a large portion of UGH is due to acid‐related disease in patients not on preventive therapy, then these unanswered questions may become important for future research.

In contrast to previous studies, the current study examines the distribution of etiologies of UGH in the era of widespread use of effective preventive therapy for ED and PUD in 2 U.S. academic medical centers. Prior studies were done before the advent of new therapeutics and did not compare different sites, which may be important.16, 17

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Consecutive patients admitted with UGH were identified at 2 academic medical centers as part of a larger observational study examining the impact of hospitalist physicians on the care of acute medical patients.18 The sample was selected from the 12,091 consecutive general medical patients admitted from July 2001 to June 2003 with UGH identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9 CM) codes from administrative data and confirmed by chart abstraction. ICD‐9 CM codes for UGH included: esophageal varices with hemorrhage (456.0 and 456.20), Mallory‐Weiss syndrome (530.7), gastric ulcer with hemorrhage (531.00‐531.61), duodenal ulcer with hemorrhage (532.00‐532.61), peptic ulcer, site unspecified, with hemorrhage (533.00‐533.61), gastrojejunal ulcer with hemorrhage (534.00‐534.61), gastritis with hemorrhage (535.61), angiodysplasia of stomach/duodenum with hemorrhage (537.83), and hematemesis (578.0 and 578.9).19 Finally, the admission diagnoses for all patients in the larger cohort were reviewed and any with gastrointestinal hemorrhage were screened for possible inclusion to account for any missed ICD‐9 codes. Subjects were then included in this analysis if they had observed hematemesis, nasogastric (NG) tube aspirate with gross or hemoccult blood, or history of hematemesis, bloody diarrhea, or melena upon chart review.

Data

The inpatient medical records were abstracted by trained researchers. Etiologies of UGH were assessed by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) report, which listed findings and etiologies as assessed by the endoscopist. Multiple etiologies were allowed if more than 1 source of bleeding was identified. Prior medical history and preadmission medication use were obtained from 3 sources: (1) the emergency department medical record; (2) nursing admission documentation; and (3) the admission history and physical documentation. Risk factors and preadmission medication use were considered present if documented in any of the 3 sources. Relevant past medical history included known risk factors for UGH, including: end‐stage renal disease, alcohol abuse, prior history of UGH, and steroid use. Prior H. pylori status/testing could not reliably be obtained from these data sources. Preadmission medication use of interest included aspirin, NSAIDS, anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, as well as PPIs and COX‐2s. Demographics, including age, race, and gender, were obtained from administrative databases.

We defined subjects as at‐risk if they had any of the following risk factors: prior UGH (at any time), use of an NSAID (traditional or selective COX‐2), or use of an aspirin prior to admission. Patients taking COX‐2s were included for 2 reasons. First, while COX‐2 inhibitors are associated with a lower risk of UGH than traditional NSAIDs, it is likely that they still lead to an increased risk of UGH compared to placebo. Second, if a patient required NSAIDs of some type (traditional or selective), preadmission use of a COX‐2 rather than a traditional NSAID may reflect the intention of decreasing the risk of UGH compared to using traditional NSAIDs. In order to use the most conservative estimate of potential missed opportunities for prevention, preadmission use of a PPI or COX‐2 was considered preventive therapy. All preadmission medication use was obtained from chart review. Therefore, duration of and purpose for medication use were not available.

Development of the abstraction tool was performed by the authors. Testing of the tool was performed on a learning set of 20 charts at each center. All additional abstractors were trained with a learning set of at least 20 charts to assure uniform abstraction techniques.

Analysis

For each risk factor and etiology, we calculated the proportion of patients with the risk factor or etiology both overall and by site. Differences in risk factors between sites were assessed using chi‐square tests of association. Differences in etiologies between sites were assessed using unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) as well as ORs from logistic regression models controlling for age, gender, and race (black versus not black). Center 1 was the urban center and center 2 was the rural site.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine and the University of Chicago.

RESULTS

From the entire cohort of 12,091 admitted to the 2 inpatient medical services, 227 (1.9%) patients were identified as having UGH; 138 (61%) were from center 1, where 87% of patients were black and 89 (39%) were from center 2, where 89% of patients were white. Overall, the mean age was 59 years, 45% were female, and 41% were white (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Total (n = 227) | Center 1 (n = 138) | Center 2 (n = 89) | P Value Center 1 versus 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Mean age (years) | 58.6 | 59.5 | 57.1 | 0.317 |

| % Female | 44.5 | 48.6 | 38.2 | 0.126 |

| % White | 41.2 | 10.2 | 88.8 | <0.001 |

| % African American | 54.0 | 86.9 | 3.4 | <0.001 |

| % Other | 4.9 | 2.9 | 7.9 | <0.001 |

The most common etiologies of UGH were ED (44%), PUD (33%), and varices (17%) in the overall population. These same 3 etiologies were also the most common in both of the medical centers, although there were significant differences in the rates of etiologies between the 2 centers. ED was more common among subjects from center 1 (59%) than from center 2 (19%) (P < 0.001), while variceal bleeding was more common among subjects from center 2 (34%) than from center 1 (6.5%) (P = 0.009) (Table 2).

| Etiology | All n = 227 (%) | Center 1 n = 138 (%) | Center 2 n = 89 (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI): Center 1 versus 2 | P Value for Unadjusted OR | Adjusted* OR (95% CI): Center 1 versus 2 | P Value (for Adjusted OR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| ED | 43.6 | 59.4 | 19.1 | 6.20 (3.3111.62) | <0.001 | 7.10 (2.4820.31) | <0.001 |

| PUD | 33.0 | 37.0 | 27.0 | 1.59 (0.892.84) | 0.119 | 1.33 (0.483.67) | 0.578 |

| Varices | 17.2 | 6.5 | 33.7 | 0.14 (0.060.31) | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.030.60) | 0.009 |

| AVM | 5.3 | 2.9 | 9.0 | 0.30 (0.091.04) | 0.057 | 0.21 (0.031.69) | 0.141 |

| Mallory Weiss Tear | 4.9 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 0.76 (0.232.58) | 0.664 | 0.34 (0.024.85) | 0.425 |

| Cancer/masses | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.30 (0.237.24) | 0.766 | 0.62 (0.0312.12) | 0.751 |

In multivariate logistic regression analyses, only age and site remained independent predictors of etiologies. Advancing age was associated with a higher risk of arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) with the odds of AVMs increasing 6% for every additional year of life (P = 0.007). Site was associated with both ED and variceal bleeding. Patients from center 1 were significantly more likely to have UGH caused by ED, with an OR = 7.10 (P < 0.001), compared to subjects from center 2. However, subjects from center 1 had a significantly lower OR (OR = 0.12) than those subjects at center 2 (P = 0.009) of having UGH caused by a variceal bleed (Table 2).

Risk factors for UGH were common among the patients, including use of aspirin (25.1%), NSAIDs (22.9%), COX‐2s (4.9%), or prior history of UGH (43%). Additionally, 6.6% of patients were taking both an NSAID and aspirin. Differences between the 2 sites were seen only in aspirin use, with 34.8% of patients in the center 1 population using aspirin compared to 10.1% in center 2 (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

| Risk Factor | All (%) | Center 1 (%) | Center 2 (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Previous UGH | 42.7 | 41.3 | 45.2 | 0.586 |

| NSAID use | 22.9 | 21.7 | 24.7 | 0.602 |

| ASA use | 25.1 | 34.8 | 10.1 | <0.001 |

| NSAID + ASA | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 0.948 |

| COX‐2 use | 4.9 | 6.5 | 2.3 | 0.143 |

| PPI use | 18.5 | 18.1 | 19.1 | 0.852 |

Among the overall population, 68.7% of patients had identifiable risk factors (prior history of UGH or preadmission use of aspirin, NSAIDs, or COX‐2s). Of all subjects, 18.5% were on PPIs and 4.9% were taking COX‐2s while 21.1% of at risk subjects were on PPIs and 6.5% of these subjects were on a COX‐2.

Finally, we examined the effects of variations in preadmission medication use between the sites on the etiologies of UGH. None of the site‐based differences in etiologies could be explained by differences in preadmission medication patterns.

DISCUSSION

Despite the emergence of effective therapies for lowering the risk of ED and PUD, these remain the most common etiologies of UGH in our cohort of patients. In a dramatic change from historically reported patterns, ED was more common than PUD. In prior studies, PUD accounted for almost two‐thirds of all UGH.2 While some of the newer therapeutics such as PPIs and COX‐2s reduce the risk for acid‐related bleeding of all types, H. pylori eradication is effective primarily for PUD. Therefore, it may be that widespread testing and treatment of H. pylori have dramatically decreased rates of PUD. Unfortunately, this study does not allow us to directly evaluate the effect of H. pylori treatment on the changing epidemiology of UGH, as that would require a population‐based study.

While decreasing rates of PUD could explain a portion of the change in the distribution of etiologies, increasing rates of ED could also be playing a role. Prior studies have suggested that African Americans and the elderly are more susceptible to ED, particularly in the setting of NSAIDs and/or aspirin use, and less susceptible to cirrhosis.13, 16, 17, 2023 Our finding of a higher rate of ED and lower rates of cirrhosis in center 1 with a higher proportion of African Americans and greater aspirin use is consistent with these prior findings. However, in multivariate analyses, neither race nor preadmission medication use patterns explained the differences in etiologies seen. This suggests that some other factors must play a role in the differences between the 2 centers studied. These results emphasize the importance of local site characteristics in the interpretation and implementation of national guidelines and recommendations. This finding may be particularly important in diseases and clinical presentations that rely on protocol‐driven pathways, such as UGH. Current recommendations on implementing clinical pathways derived from national guidelines emphasize the fact that national development and local implementation optimization is probably the best approach for effective pathway utilization.24

It is important to understand why ED and PUD, for which we now have effective pharmacologic therapies, continue to account for such a large percentage of the burden of UGH. In this study, we found that a majority of subjects were known to have significant risk factors for UGH (aspirin use, NSAID use, COX‐2s, or prior UGH) and only 31% of the subjects could not have been identified as at‐risk prior to admission. PPIs or COX‐2s should not be used universally as preventive therapy, and they are not completely effective at preventing UGH in at‐risk patients. In this study, two‐thirds of patients with risk factors were not on preventive therapy, but almost one‐third of patients with risk factors had bleeding despite being on preventive therapy. A better understanding of why these treatment failures (bleeding despite preventive therapy) occur may be helpful in our future ability to prevent UGH. This study was not designed to determine if the two‐thirds of patients not taking preventive therapy were being treated consistent with established guidelines. However, current guidelines have significant variation in recommendations as to which patients are at high enough risk to warrant preventive therapy,1315 and there is no consensus as to which patients are at high enough risk to warrant preventive therapy. Our data suggest that additional studies will be required to determine the optimal recommendations for preventive therapy among at‐risk patients.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it only included 2 academic institutions. However, these institutions represented very different patient populations. Second, the study design is not a population‐based study. This limitation prevents us from addressing questions such as the effectiveness or cost‐effectiveness of interventions to prevent admission for UGH. Although we analyzed preadmission PPI or COX‐2 use in at‐risk patients as preventive therapy, we are unable to determine the actual intent of the physician in prescribing these drugs. Finally, although the mechanisms by which PPIs and COX‐2 affect the risk of UGH are fundamentally different and should not be considered equivalent choices, we chose to analyze either option as representing a preventive strategy in order to provide the most conservative estimate possible of preventive therapy utilization rates. However, our assumptions would generally overestimate the use of preventive therapy (as opposed to PPI use for symptom control), as we assumed all potentially preventive therapy was intended as such.

This study highlights several unanswered questions that may be important in the management of UGH. First, identifying factors that affect local patters of UGH may better inform local implementation of nationally developed guidelines. Second, a more complete understanding of the impact positive and negative risk factors for UGH have on specific patient populations may allow for a more consistent targeted approach to using preventive therapy in at‐risk patients.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, is to determine if the change in distribution of etiologies is in fact related to a decline in bleeding related to PUD. In addition to this being a marker of the success of the H. pylori story, it may have important implications on our understanding of the acute management of UGH. If PUD is of a different severity than other common causes of UGH, such as ED, current risk stratification prediction models may need to be revalidated. For example, if UGH secondary to PUD results in greater morbidity and mortality than UGH secondary to ED, our current models identifying who requires ICU admission, urgent endoscopy, and other therapeutic interventions may result in overutilization of these resource intensive interventions. However, if larger studies do not confirm this decline in PUD it suggests the need for additional studies to identify why PUD remains so prevalent despite the major advances in treatment and prevention of PUD through H. pylori identification and eradication.

- ,,, et al.Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists.Ann Int Med.2002;137(11):866–874.

- .Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population‐based study.Am J Gastroenterol.1995;90(2):206–210.

- ,,, et al.Epidemiology and course of acute upper gastro‐intestinal haemorrhage in four French geographical areas.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol.2000;12:175–181.

- ,,, et al.Prevention of ulcer recurrence after eradication of Helicobacter pylore: a prospective long‐term follow‐up study.Gastroenterology.1997;113:1082–1086.

- ,,, et al.Treatment of Helicobacter pylore in patients with duodenal ulcer hemorrhage‐a long‐term randomized, controlled study.Am J Gasterenterol.2000;95:2225–2232.

- ,,, et al.Preventing recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection who are taking low‐dose aspirin or naproxen.N Engl J Med.2001;344:967–973.

- ,,, et al.Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long‐term low‐dose aspirin use.N Engl J Med.2002;346:2033–2038.

- ,,, et al.Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change?: time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000.Am J Gastroenterol.2003;98:1494–1499.

- ,,, et al.Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage clinical guideline‐determining the optimal length of stay.Am J Med.1996;100:313–322.

- ,,.Consensus recommendations for managing patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.Ann Intern Med.2003;139:843–857.

- ,,, et al.Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group.N Engl J Med.2000;343:1520–1528.

- ,, et al.Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long‐term Arthritis Safety Study.JAMA.2000;284:1247–1255.

- AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons.The management of persistent pain in older persons.J Am Geriatr Soc.2002;50(6 Suppl):S205–S224.

- ,,, et al.Pain in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile chronic arthritis.2nd ed.Clinical practice guideline no. 2.Glenview, IL:American Pain Society (APS);2002:179 p.

- .Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee.Arthritis Rheum.2000;43:1905–1915.

- ,,, et al.Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom.BMJ.1995;311:222–226.

- ,,, et al.Risk factors for hospitalized gastrointestinal bleeding among older persons.J Am Geriatr Soc.2001;49:126–133.

- ,,, et al.Effects of inpatient experience on outcomes and costs in a multicenter trial of academic hospitalists.Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting2005.

- ,,,,,.Early endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: association with recurrent bleeding, surgery, and length of hospital stay.Gastrointest Endosc.1999;49(2):145–152.

- ,,, et al.A comparison of the spectrum of chronic hepatitis C virus between Caucasians and African Americans.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2004;2:469–473.

- ,,, et al.Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States.Gastroenterology.2004;126:1692–1699.

- ,,,.Risk factors for erosive reflux esophagitis: a case‐control study.Am J Gastroenterol.2001;96:41–46.

- ,.Upper gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in African‐American and Hispanic elderly patients.Ethn Dis.2003;13:528–533.

- ,.Evidence‐based quality improvement: the state of the science.Health Aff (Millwood).2005;24(1):138–150.

Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (UGH) is a common cause of acute admission for hospitalization.13 However, recent advances in our understanding of erosive disease (ED) and peptic ulcer disease (PUD), 2 of the most common etiologies of UGH, have led to effective strategies to reduce the risk of UGH. Successful implementation of these strategies, such as treatment of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and selective cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors (COX‐2s) in place of traditional nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), may be able to significantly reduce rates of UGH caused by ED and PUD.47

Prior to these preventive treatments, PUD and ED, both acid‐related disorders, were the most common causes of UGH requiring admission to the hospital, accounting for 62% and 14% of all UGHs, respectively.2 Given the widespread treatment of H. pylori and use of PPIs and COX‐2s, we might expect that the distribution of etiologies of UGH may have changed. However, there are limited data on the distribution of etiologies of UGH in the era of effective preventive therapy.8 If the distribution of etiologies causing patients to present with UGH has fundamentally changed with these new treatments, established strategies of managing acute UGH may need to be reevaluated. Given that well‐established guidelines exist and that many hospitals use a protocol‐driven management strategy to decide on the need for admission and/or intensive care unit (ICU) admission, changes in the distribution of etiologies since the widespread use of these new pharmacologic approaches may affect the appropriateness of these protocols.9, 10 For example, if the eradication of H. pylori has dramatically reduced the proportion of UGH caused by PUD, then risk stratification studies developed when PUD was far more common may need to be revisited. This would be particularly important if bleeding from PUD was of significantly different severity than bleeding from other causes.