User login

125I seed placement before neoadjuvant chemotherapy good marking method for metastatic lymph nodes in BC

Key clinical point: Targeted axillary dissection (TAD) by marking the metastatic lymph node with 125I seeds before neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) showed excellent identification rates and ruled out the need for remarking before surgery.

Major finding: The identification rates of the marked lymph node (MLN) and sentinel node (SN) were 99.3% and 91.5%, respectively, with the TAD procedure being successful in 91.5% of patients based on the identification of both MLN and SN. Overall, 40.8% of patients achieved axillary pathologic complete response and could be spared from surgery.

Study details: Findings are from a cohort study including 142 patients with BC who underwent TAD after 125I seeds were placed before NACT.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Helsefonden. The authors did not report conflicts of interest.

Source: Munck F et al. Targeted axillary dissection with 125I seed placement before neoadjuvant chemotherapy in a Danish multicenter cohort. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023 (Apr 16). Doi: 10.1245/s10434-023-13432-4

Key clinical point: Targeted axillary dissection (TAD) by marking the metastatic lymph node with 125I seeds before neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) showed excellent identification rates and ruled out the need for remarking before surgery.

Major finding: The identification rates of the marked lymph node (MLN) and sentinel node (SN) were 99.3% and 91.5%, respectively, with the TAD procedure being successful in 91.5% of patients based on the identification of both MLN and SN. Overall, 40.8% of patients achieved axillary pathologic complete response and could be spared from surgery.

Study details: Findings are from a cohort study including 142 patients with BC who underwent TAD after 125I seeds were placed before NACT.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Helsefonden. The authors did not report conflicts of interest.

Source: Munck F et al. Targeted axillary dissection with 125I seed placement before neoadjuvant chemotherapy in a Danish multicenter cohort. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023 (Apr 16). Doi: 10.1245/s10434-023-13432-4

Key clinical point: Targeted axillary dissection (TAD) by marking the metastatic lymph node with 125I seeds before neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) showed excellent identification rates and ruled out the need for remarking before surgery.

Major finding: The identification rates of the marked lymph node (MLN) and sentinel node (SN) were 99.3% and 91.5%, respectively, with the TAD procedure being successful in 91.5% of patients based on the identification of both MLN and SN. Overall, 40.8% of patients achieved axillary pathologic complete response and could be spared from surgery.

Study details: Findings are from a cohort study including 142 patients with BC who underwent TAD after 125I seeds were placed before NACT.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Helsefonden. The authors did not report conflicts of interest.

Source: Munck F et al. Targeted axillary dissection with 125I seed placement before neoadjuvant chemotherapy in a Danish multicenter cohort. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023 (Apr 16). Doi: 10.1245/s10434-023-13432-4

HER2+ early BC: Extent of disease at diagnosis may predict risk for relapse even after pCR

Key clinical point: Pretreatment tumor stage and nodal involvement could predict the risk for disease relapse in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) early breast cancer (BC) who had achieved pathologic complete response (pCR) with neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus anti-HER2 therapy.

Major finding: Patients who did vs did not achieve pCR had prolonged event-free survival (EFS; hazard ratio [HR] 0.39) and overall survival (HR 0.32; both P < .001). However, in patients with pCR, higher pretreatment tumor stage (cT3-4 vs cT1-2; P = .007) and presence of nodal involvement (cN+ vs cN−; P = .039) could worsen EFS.

Study details: This study analyzed the data of 3710 patients with HER2+ early BC from 11 trials who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy+anti-HER2 therapy, of which 40.4% of patients had achieved pCR.

Disclosures: This study was supported by author Sibylle Loibl. Several authors declared serving as consultants or advisors, receiving honoraria or research funding, or having other ties with various sources.

Source: van Mackelenbergh MT et al on behalf of the CTNeoBC project. Pathologic complete response and individual patient prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 therapy of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023 (Apr 19). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.02241

Key clinical point: Pretreatment tumor stage and nodal involvement could predict the risk for disease relapse in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) early breast cancer (BC) who had achieved pathologic complete response (pCR) with neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus anti-HER2 therapy.

Major finding: Patients who did vs did not achieve pCR had prolonged event-free survival (EFS; hazard ratio [HR] 0.39) and overall survival (HR 0.32; both P < .001). However, in patients with pCR, higher pretreatment tumor stage (cT3-4 vs cT1-2; P = .007) and presence of nodal involvement (cN+ vs cN−; P = .039) could worsen EFS.

Study details: This study analyzed the data of 3710 patients with HER2+ early BC from 11 trials who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy+anti-HER2 therapy, of which 40.4% of patients had achieved pCR.

Disclosures: This study was supported by author Sibylle Loibl. Several authors declared serving as consultants or advisors, receiving honoraria or research funding, or having other ties with various sources.

Source: van Mackelenbergh MT et al on behalf of the CTNeoBC project. Pathologic complete response and individual patient prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 therapy of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023 (Apr 19). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.02241

Key clinical point: Pretreatment tumor stage and nodal involvement could predict the risk for disease relapse in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) early breast cancer (BC) who had achieved pathologic complete response (pCR) with neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus anti-HER2 therapy.

Major finding: Patients who did vs did not achieve pCR had prolonged event-free survival (EFS; hazard ratio [HR] 0.39) and overall survival (HR 0.32; both P < .001). However, in patients with pCR, higher pretreatment tumor stage (cT3-4 vs cT1-2; P = .007) and presence of nodal involvement (cN+ vs cN−; P = .039) could worsen EFS.

Study details: This study analyzed the data of 3710 patients with HER2+ early BC from 11 trials who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy+anti-HER2 therapy, of which 40.4% of patients had achieved pCR.

Disclosures: This study was supported by author Sibylle Loibl. Several authors declared serving as consultants or advisors, receiving honoraria or research funding, or having other ties with various sources.

Source: van Mackelenbergh MT et al on behalf of the CTNeoBC project. Pathologic complete response and individual patient prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 therapy of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023 (Apr 19). Doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.02241

Postmastectomy implants did not increase risk for squamous cell carcinoma in BC patients

Key clinical point: The incidence rate of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was extremely low and, hence, of minimal public health concern in patients with non-SCC breast cancer (BC) or carcinoma in situ who underwent implant-based reconstruction.

Major finding: Only 1 woman was diagnosed with SCC after 52 months of BC diagnosis. The incidence rate of SCC after implant-based reconstruction was extremely low (2.37 per million person-years) and was not significantly higher in women with BC than in the general population (standardized incidence ratio 2.33; 95% CI 0.06-13.0).

Study details: Findings are from a cohort study including 56,785 women with BC or carcinoma in situ who underwent cancer-directed mastectomy with implant reconstruction.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute. Some authors declared receiving personal fees or grants or having other ties with several sources.

Source: Kinslow CJ et al. Risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the breast following postmastectomy implant reconstruction in women with breast cancer and carcinoma in situ. JAMA Surg. 2023 (Apr 19). Doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.0262

Key clinical point: The incidence rate of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was extremely low and, hence, of minimal public health concern in patients with non-SCC breast cancer (BC) or carcinoma in situ who underwent implant-based reconstruction.

Major finding: Only 1 woman was diagnosed with SCC after 52 months of BC diagnosis. The incidence rate of SCC after implant-based reconstruction was extremely low (2.37 per million person-years) and was not significantly higher in women with BC than in the general population (standardized incidence ratio 2.33; 95% CI 0.06-13.0).

Study details: Findings are from a cohort study including 56,785 women with BC or carcinoma in situ who underwent cancer-directed mastectomy with implant reconstruction.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute. Some authors declared receiving personal fees or grants or having other ties with several sources.

Source: Kinslow CJ et al. Risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the breast following postmastectomy implant reconstruction in women with breast cancer and carcinoma in situ. JAMA Surg. 2023 (Apr 19). Doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.0262

Key clinical point: The incidence rate of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was extremely low and, hence, of minimal public health concern in patients with non-SCC breast cancer (BC) or carcinoma in situ who underwent implant-based reconstruction.

Major finding: Only 1 woman was diagnosed with SCC after 52 months of BC diagnosis. The incidence rate of SCC after implant-based reconstruction was extremely low (2.37 per million person-years) and was not significantly higher in women with BC than in the general population (standardized incidence ratio 2.33; 95% CI 0.06-13.0).

Study details: Findings are from a cohort study including 56,785 women with BC or carcinoma in situ who underwent cancer-directed mastectomy with implant reconstruction.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute. Some authors declared receiving personal fees or grants or having other ties with several sources.

Source: Kinslow CJ et al. Risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the breast following postmastectomy implant reconstruction in women with breast cancer and carcinoma in situ. JAMA Surg. 2023 (Apr 19). Doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2023.0262

Better lifestyle index scores associated with improved mortality and disease recurrence in high-risk BC

Key clinical point: Adherence to the American Institute for Cancer Research and American Cancer Society’s lifestyle recommendations reduced the risk for disease recurrence and improved mortality in patients with high-risk breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: Patients in the highest vs lowest tertile of lifestyle index scores (LIS) experienced a 37% reduction in recurrence (hazard ratio [HR] 0.63; 95% CI 0.48-0.82) and those in the middle (HR 0.70; P = .03) and highest (HR 0.42; P < .001) vs lowest tertile of LIS had significant reductions in mortality.

Study details: Findings are from the prospective, observational, DELCaP (The Diet, Exercise, Lifestyles, and Cancer Prognosis) study including 1340 chemotherapy-naive women with high-risk stage I to III BC, of which the majority (65.3%) of women had hormone receptor-positive BC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute and The Breast Cancer Research Foundation, New York Some authors declared serving as members of independent data monitoring committees or receiving grants or personal fees from several sources.

Source: Cannioto RA et al. Adherence to cancer prevention lifestyle recommendations before, during, and 2 years after treatment for high-risk breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2311673 (May 4). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.11673

Key clinical point: Adherence to the American Institute for Cancer Research and American Cancer Society’s lifestyle recommendations reduced the risk for disease recurrence and improved mortality in patients with high-risk breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: Patients in the highest vs lowest tertile of lifestyle index scores (LIS) experienced a 37% reduction in recurrence (hazard ratio [HR] 0.63; 95% CI 0.48-0.82) and those in the middle (HR 0.70; P = .03) and highest (HR 0.42; P < .001) vs lowest tertile of LIS had significant reductions in mortality.

Study details: Findings are from the prospective, observational, DELCaP (The Diet, Exercise, Lifestyles, and Cancer Prognosis) study including 1340 chemotherapy-naive women with high-risk stage I to III BC, of which the majority (65.3%) of women had hormone receptor-positive BC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute and The Breast Cancer Research Foundation, New York Some authors declared serving as members of independent data monitoring committees or receiving grants or personal fees from several sources.

Source: Cannioto RA et al. Adherence to cancer prevention lifestyle recommendations before, during, and 2 years after treatment for high-risk breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2311673 (May 4). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.11673

Key clinical point: Adherence to the American Institute for Cancer Research and American Cancer Society’s lifestyle recommendations reduced the risk for disease recurrence and improved mortality in patients with high-risk breast cancer (BC).

Major finding: Patients in the highest vs lowest tertile of lifestyle index scores (LIS) experienced a 37% reduction in recurrence (hazard ratio [HR] 0.63; 95% CI 0.48-0.82) and those in the middle (HR 0.70; P = .03) and highest (HR 0.42; P < .001) vs lowest tertile of LIS had significant reductions in mortality.

Study details: Findings are from the prospective, observational, DELCaP (The Diet, Exercise, Lifestyles, and Cancer Prognosis) study including 1340 chemotherapy-naive women with high-risk stage I to III BC, of which the majority (65.3%) of women had hormone receptor-positive BC.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the US National Cancer Institute and The Breast Cancer Research Foundation, New York Some authors declared serving as members of independent data monitoring committees or receiving grants or personal fees from several sources.

Source: Cannioto RA et al. Adherence to cancer prevention lifestyle recommendations before, during, and 2 years after treatment for high-risk breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2311673 (May 4). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.11673

Anthracycline+taxane combo reduces BC recurrence more effectively than either drug alone

Key clinical point: Breast cancer (BC) recurrence rates are lower among patients treated with the combination of anthracycline and taxane compared with a taxane regimen without anthracycline or an anthracycline-based regimen without taxane.

Major finding: Anthracycline plus taxane reduced the rate of BC recurrence by 14% (rate ratio [RR] 0.86; P = .0004) compared with taxane only and by 13% (RR 0.87; P < .0001) compared with anthracycline only. The highest benefit was observed among patients receiving anthracycline concurrently with docetaxel+cyclophosphamide vs docetaxel+cyclophosphamide only (RR 0.58; P < .0001).

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis including more than 100,000 women with early-stage BC from 86 trials on anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapies.

Disclosures: This study is funded by Cancer Research UK. The authors declared receiving grants, payments, honoraria, consulting fees, or travel support from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Anthracycline-containing and taxane-containing chemotherapy for early-stage operable breast cancer: A patient-level meta-analysis of 100 000 women from 86 randomised trials. Lancet. 2023;401(10384):1277-1292 (Apr 15). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00285-4

Key clinical point: Breast cancer (BC) recurrence rates are lower among patients treated with the combination of anthracycline and taxane compared with a taxane regimen without anthracycline or an anthracycline-based regimen without taxane.

Major finding: Anthracycline plus taxane reduced the rate of BC recurrence by 14% (rate ratio [RR] 0.86; P = .0004) compared with taxane only and by 13% (RR 0.87; P < .0001) compared with anthracycline only. The highest benefit was observed among patients receiving anthracycline concurrently with docetaxel+cyclophosphamide vs docetaxel+cyclophosphamide only (RR 0.58; P < .0001).

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis including more than 100,000 women with early-stage BC from 86 trials on anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapies.

Disclosures: This study is funded by Cancer Research UK. The authors declared receiving grants, payments, honoraria, consulting fees, or travel support from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Anthracycline-containing and taxane-containing chemotherapy for early-stage operable breast cancer: A patient-level meta-analysis of 100 000 women from 86 randomised trials. Lancet. 2023;401(10384):1277-1292 (Apr 15). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00285-4

Key clinical point: Breast cancer (BC) recurrence rates are lower among patients treated with the combination of anthracycline and taxane compared with a taxane regimen without anthracycline or an anthracycline-based regimen without taxane.

Major finding: Anthracycline plus taxane reduced the rate of BC recurrence by 14% (rate ratio [RR] 0.86; P = .0004) compared with taxane only and by 13% (RR 0.87; P < .0001) compared with anthracycline only. The highest benefit was observed among patients receiving anthracycline concurrently with docetaxel+cyclophosphamide vs docetaxel+cyclophosphamide only (RR 0.58; P < .0001).

Study details: Findings are from a meta-analysis including more than 100,000 women with early-stage BC from 86 trials on anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapies.

Disclosures: This study is funded by Cancer Research UK. The authors declared receiving grants, payments, honoraria, consulting fees, or travel support from or having other ties with various sources.

Source: Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Anthracycline-containing and taxane-containing chemotherapy for early-stage operable breast cancer: A patient-level meta-analysis of 100 000 women from 86 randomised trials. Lancet. 2023;401(10384):1277-1292 (Apr 15). Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00285-4

Study explains link between fatty liver and CRC liver metastasis

according to the authors of new research.

These findings support the previously reported link between fatty liver and colorectal cancer (CRC) liver metastasis, and suggest that CRC patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may respond differently to treatment than CRC patients without NAFLD, wrote lead author Zhijun Wang, MD, PhD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and colleagues, in their paper.

“Obesity and NAFLD are the significant risk factors for CRC,” the investigators explained, in Cell Metabolism. “A growing body of epidemiological evidence indicates that fatty liver increases the occurrence of CRC liver metastasis and the local recurrence after resection of CRC liver metastases, thereby worsening prognosis ... There is an urgent need to understand the molecular mechanisms of metastasis in patients with fatty liver to manage those patients effectively.”

To this end, Dr. Wang and colleagues conducted a series of experiments involving mice, cell cultures, and human sera. They found that fatty liver increases risk of CRC liver metastasis via extracellular vesicles (EVs) that contain procarcinogenic miRNAs. As these EVs transfer microRNAs from fatty liver hepatocytes to metastatic cancer cells, YAP activity increases, which, in turn, suppresses immune activity within the tumor microenvironment, promoting growth of CRC metastasis.

Beyond the increased risk of liver metastasis presented by fatty liver, the investigators suggested that NAFLD may cause “more complex” metastatic tumor microenvironments, potentially explaining “diverse responses” to cancer therapies among patients with CRC and liver metastases.

“In summary, our study demonstrates that the pre- and prometastatic liver environment of fatty liver is induced by procarcinogenic EVs and results in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironemnt, in which YAP plays an important role,” the investigators concluded. “Our study provides new insight into [the] distinct liver tumor microenvironment in patients with fatty liver and without fatty liver, which may contribute to the aggressiveness of metastatic tumors and weak responses to anticancer therapy in patients with fatty liver. Additional studies are warranted to develop precision medicine for treating patients with CRC and liver metastasis.”

One of the study authors disclosed relationships with Altimmune, Cytodyn, Novo Nordisk, and others. The other investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

according to the authors of new research.

These findings support the previously reported link between fatty liver and colorectal cancer (CRC) liver metastasis, and suggest that CRC patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may respond differently to treatment than CRC patients without NAFLD, wrote lead author Zhijun Wang, MD, PhD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and colleagues, in their paper.

“Obesity and NAFLD are the significant risk factors for CRC,” the investigators explained, in Cell Metabolism. “A growing body of epidemiological evidence indicates that fatty liver increases the occurrence of CRC liver metastasis and the local recurrence after resection of CRC liver metastases, thereby worsening prognosis ... There is an urgent need to understand the molecular mechanisms of metastasis in patients with fatty liver to manage those patients effectively.”

To this end, Dr. Wang and colleagues conducted a series of experiments involving mice, cell cultures, and human sera. They found that fatty liver increases risk of CRC liver metastasis via extracellular vesicles (EVs) that contain procarcinogenic miRNAs. As these EVs transfer microRNAs from fatty liver hepatocytes to metastatic cancer cells, YAP activity increases, which, in turn, suppresses immune activity within the tumor microenvironment, promoting growth of CRC metastasis.

Beyond the increased risk of liver metastasis presented by fatty liver, the investigators suggested that NAFLD may cause “more complex” metastatic tumor microenvironments, potentially explaining “diverse responses” to cancer therapies among patients with CRC and liver metastases.

“In summary, our study demonstrates that the pre- and prometastatic liver environment of fatty liver is induced by procarcinogenic EVs and results in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironemnt, in which YAP plays an important role,” the investigators concluded. “Our study provides new insight into [the] distinct liver tumor microenvironment in patients with fatty liver and without fatty liver, which may contribute to the aggressiveness of metastatic tumors and weak responses to anticancer therapy in patients with fatty liver. Additional studies are warranted to develop precision medicine for treating patients with CRC and liver metastasis.”

One of the study authors disclosed relationships with Altimmune, Cytodyn, Novo Nordisk, and others. The other investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

according to the authors of new research.

These findings support the previously reported link between fatty liver and colorectal cancer (CRC) liver metastasis, and suggest that CRC patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) may respond differently to treatment than CRC patients without NAFLD, wrote lead author Zhijun Wang, MD, PhD, of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, and colleagues, in their paper.

“Obesity and NAFLD are the significant risk factors for CRC,” the investigators explained, in Cell Metabolism. “A growing body of epidemiological evidence indicates that fatty liver increases the occurrence of CRC liver metastasis and the local recurrence after resection of CRC liver metastases, thereby worsening prognosis ... There is an urgent need to understand the molecular mechanisms of metastasis in patients with fatty liver to manage those patients effectively.”

To this end, Dr. Wang and colleagues conducted a series of experiments involving mice, cell cultures, and human sera. They found that fatty liver increases risk of CRC liver metastasis via extracellular vesicles (EVs) that contain procarcinogenic miRNAs. As these EVs transfer microRNAs from fatty liver hepatocytes to metastatic cancer cells, YAP activity increases, which, in turn, suppresses immune activity within the tumor microenvironment, promoting growth of CRC metastasis.

Beyond the increased risk of liver metastasis presented by fatty liver, the investigators suggested that NAFLD may cause “more complex” metastatic tumor microenvironments, potentially explaining “diverse responses” to cancer therapies among patients with CRC and liver metastases.

“In summary, our study demonstrates that the pre- and prometastatic liver environment of fatty liver is induced by procarcinogenic EVs and results in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironemnt, in which YAP plays an important role,” the investigators concluded. “Our study provides new insight into [the] distinct liver tumor microenvironment in patients with fatty liver and without fatty liver, which may contribute to the aggressiveness of metastatic tumors and weak responses to anticancer therapy in patients with fatty liver. Additional studies are warranted to develop precision medicine for treating patients with CRC and liver metastasis.”

One of the study authors disclosed relationships with Altimmune, Cytodyn, Novo Nordisk, and others. The other investigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM CELL METABOLISM

HR+ early BC patients could briefly interrupt endocrine therapy to attempt pregnancy

Key clinical point: Temporarily discontinuing endocrine therapy (ET) to attempt pregnancy did not increase the recurrence risk for breast cancer (BC) in young women with early hormone receptor-positive (HR+) BC.

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 41 months, 44 patients had BC and the incidence of BC events was not higher among patients who interrupted ET vs control individuals with BC from an external cohort who received treatment with different adjuvant endocrine strategies (hazard ratio 0.81; 95% CI 0.57-1.15). Pregnancy was reported by 368 patients and 317 patients had ≥1 live birth.

Study details: Findings are from a single-group trial including 516 premenopausal women aged ≤42 years with stage I, II, or III HR+ BC treated with ET for 18-30 months who discontinued ET to attempt pregnancy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the ETOP IBCSG Partners Foundation and other sources. Some authors declared serving as consultants; receiving grants, contracts, or travel support; or having other ties with several sources.

Source: Partridge AH et al for the International Breast Cancer Study Group, and the POSITIVE Trial Collaborators. Interrupting endocrine therapy to attempt pregnancy after breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(18):1645-1656 (May 4). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212856

Key clinical point: Temporarily discontinuing endocrine therapy (ET) to attempt pregnancy did not increase the recurrence risk for breast cancer (BC) in young women with early hormone receptor-positive (HR+) BC.

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 41 months, 44 patients had BC and the incidence of BC events was not higher among patients who interrupted ET vs control individuals with BC from an external cohort who received treatment with different adjuvant endocrine strategies (hazard ratio 0.81; 95% CI 0.57-1.15). Pregnancy was reported by 368 patients and 317 patients had ≥1 live birth.

Study details: Findings are from a single-group trial including 516 premenopausal women aged ≤42 years with stage I, II, or III HR+ BC treated with ET for 18-30 months who discontinued ET to attempt pregnancy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the ETOP IBCSG Partners Foundation and other sources. Some authors declared serving as consultants; receiving grants, contracts, or travel support; or having other ties with several sources.

Source: Partridge AH et al for the International Breast Cancer Study Group, and the POSITIVE Trial Collaborators. Interrupting endocrine therapy to attempt pregnancy after breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(18):1645-1656 (May 4). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212856

Key clinical point: Temporarily discontinuing endocrine therapy (ET) to attempt pregnancy did not increase the recurrence risk for breast cancer (BC) in young women with early hormone receptor-positive (HR+) BC.

Major finding: After a median follow-up of 41 months, 44 patients had BC and the incidence of BC events was not higher among patients who interrupted ET vs control individuals with BC from an external cohort who received treatment with different adjuvant endocrine strategies (hazard ratio 0.81; 95% CI 0.57-1.15). Pregnancy was reported by 368 patients and 317 patients had ≥1 live birth.

Study details: Findings are from a single-group trial including 516 premenopausal women aged ≤42 years with stage I, II, or III HR+ BC treated with ET for 18-30 months who discontinued ET to attempt pregnancy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the ETOP IBCSG Partners Foundation and other sources. Some authors declared serving as consultants; receiving grants, contracts, or travel support; or having other ties with several sources.

Source: Partridge AH et al for the International Breast Cancer Study Group, and the POSITIVE Trial Collaborators. Interrupting endocrine therapy to attempt pregnancy after breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(18):1645-1656 (May 4). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212856

Acral Necrosis After PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy

To the Editor:

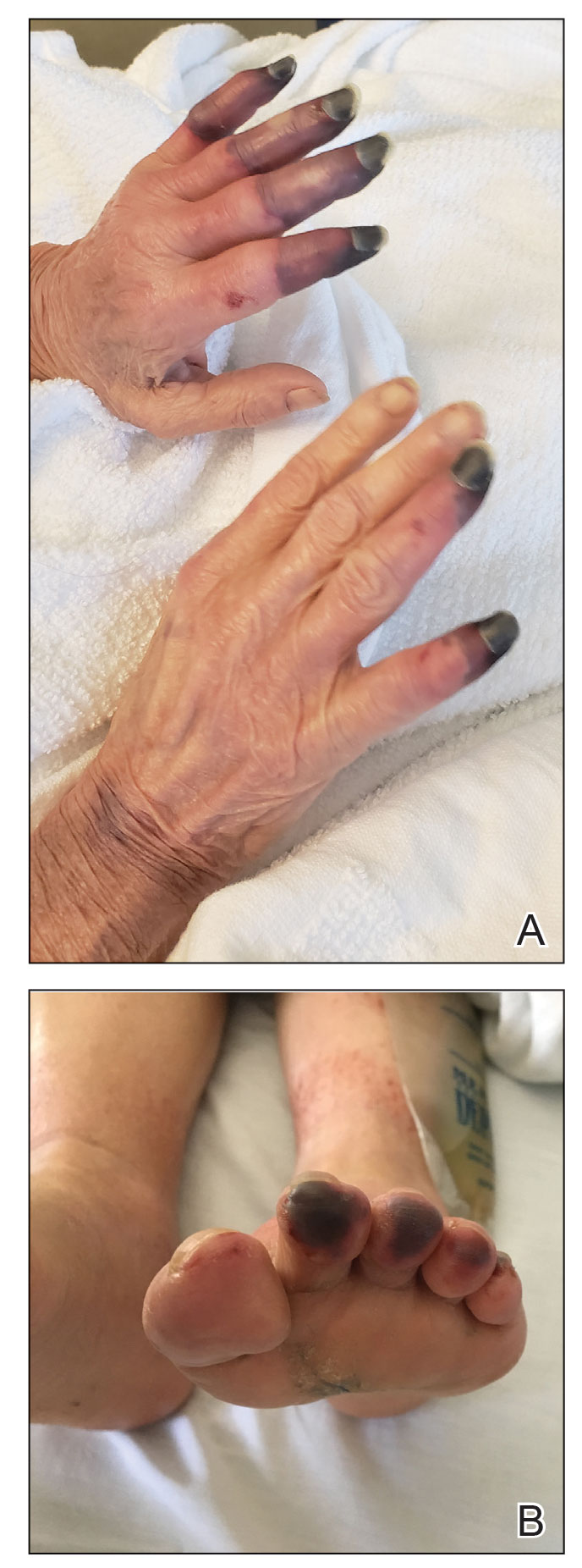

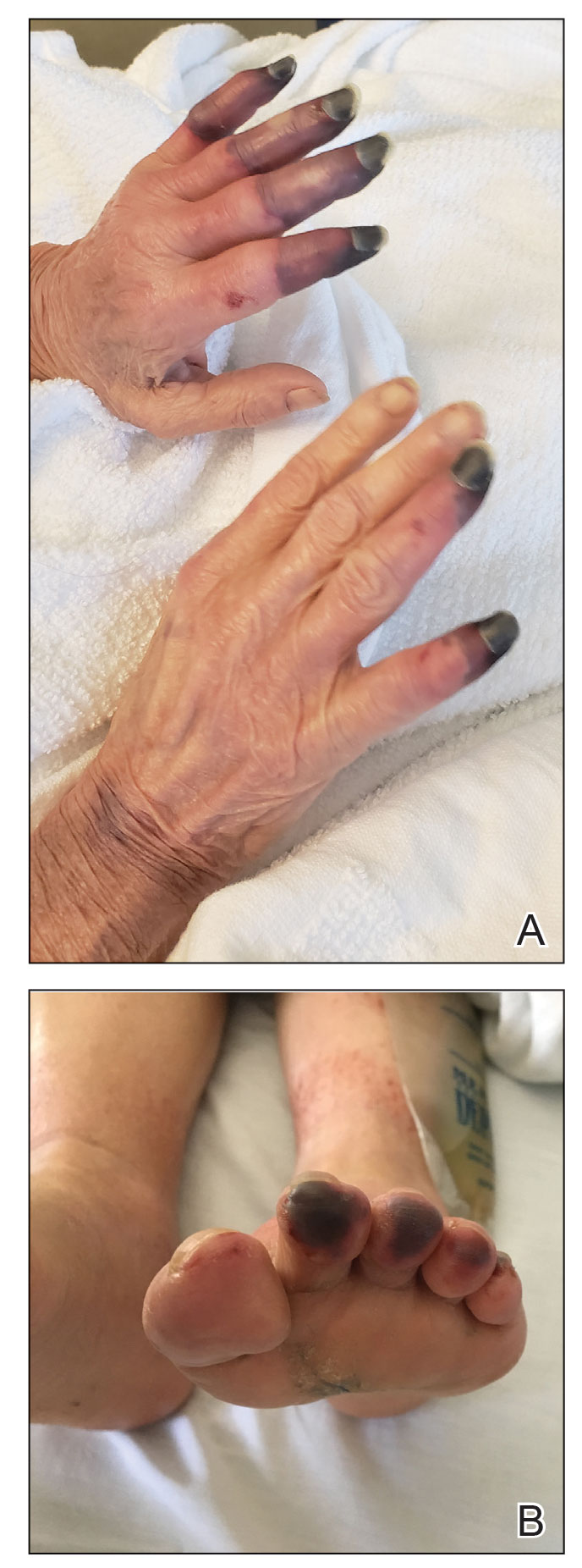

A 67-year-old woman presented to the hospital with painful hands and feet. Two weeks prior, the patient experienced a few days of intermittent purple discoloration of the fingers, followed by black discoloration of the fingers, toes, and nose with notable pain. She reported no illness preceding the presenting symptoms, and there was no progression of symptoms in the days preceding presentation.

The patient had a history of smoking. She had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as recurrent non–small cell lung cancer that was treated most recently with a 1-year course of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab (last treatment was 4 months prior to the current presentation).

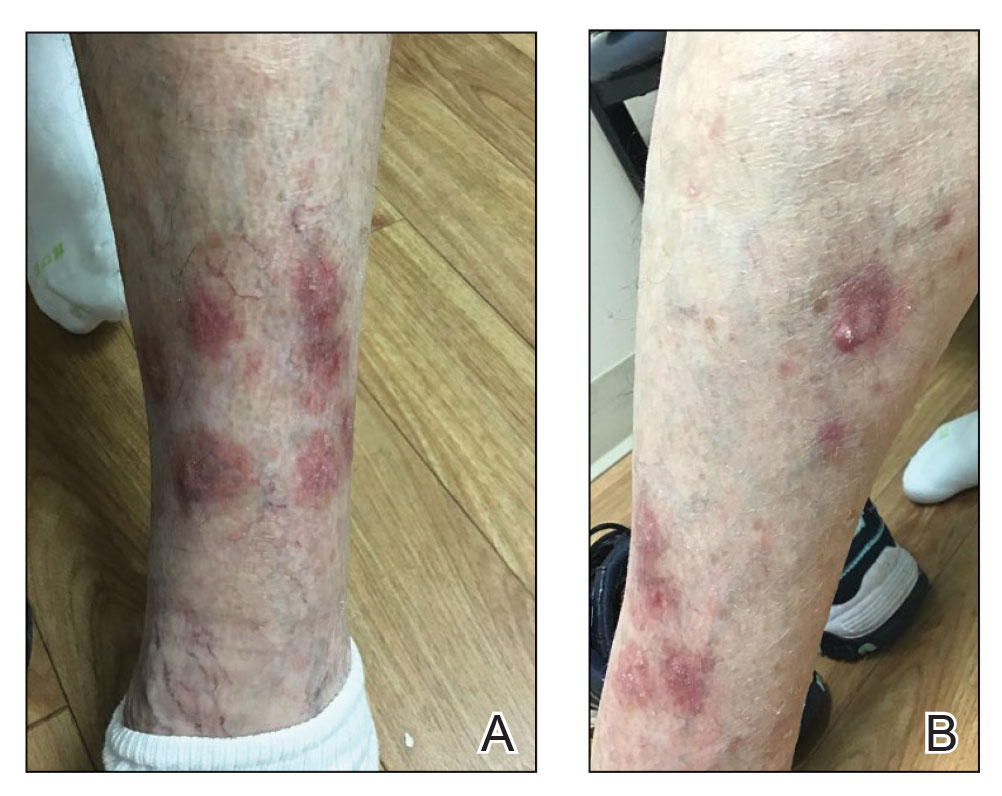

Physical examination revealed necrosis of the tips of the second, third, and fourth fingers of the left hand, as well as the tips of the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, progressing to purpura proximally on all involved fingers (Figure, A); scattered purpura and necrotic papules on the toe pads (Figure, B); and a 2- to 3-cm black plaque on the nasal tip. The patient was afebrile.

An embolic and vascular workup was performed. Transthoracic echocardiography was negative for thrombi, ankle brachial indices were within reference range, and computed tomography angiography revealed a few nonocclusive coronary plaques. Conventional angiography was not performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mildly elevated level of cryofibrinogens (cryocrit, 2.5%); cold agglutinins (1:32); mild monoclonal κ IgG gammopathy (0.1 g/dL); and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, 76 mg/L [reference range, 0–10 mg/L]; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; fibrinogen, 571 mg/dL [reference range, 150–450 mg/dL]; and ferritin, 394 ng/mL [reference range, 10–180 ng/mL]). Additional laboratory studies were negative or within reference range, including tests of anti-RNA polymerase antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3), cryoglobulins, and complement; human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C virus serologic studies; prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and lupus anticoagulant; and a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel.

A skin biopsy adjacent to an area of necrosis on the finger showed thickened walls of dermal vessels, sparse leukocytoclastic debris, and evidence of recanalizing medium-sized vessels. Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Based on the clinical history and histologic findings showing an absence of vasculitis, a diagnosis of acral necrosis associated with the PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab—a delayed immune-related event (DIRE)—was favored. The calcium channel blocker amlodipine was started at a dosage of 2.5 mg/d orally. Necrosis of the toes resolved over the course of 1 week; however, necrosis of the fingers remained unchanged. After 1 week of hospitalization, the patient was discharged at her request.

Acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been reported as a rare and recalcitrant immune-related adverse event (AE).1-4 However, our patient’s symptoms occurred months after treatment was discontinued, which is consistent with a DIRE.5 The course of acral necrosis begins with acrocyanosis (a Raynaud disease–like phenomenon) of the fingers that progresses to necrosis. A history of Raynaud disease or other autoimmune disorder generally is absent.1 Our patient’s history indicated actively smoking at the time of presentation, similar to a case described by Khaddour et al.1 Similarly, in a case presented by Comont et al,3 the patient also had a history of smoking. In a recent study of acute vascular events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 16 of 31 patients had a history of smoking.6

No definitive diagnostic laboratory or pathologic findings are associated with acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Histopathologic analysis does not demonstrate vasculitis or other overt vascular pathology.2,3

The optimal treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated digital necrosis is unclear. Corticosteroids and discontinuation of the immune checkpoint inhibitor generally are employed,1-4 though treatment response has been variable. Other therapies such as calcium channel blockers (as in our case), sympathectomy,1 epoprostenol, botulinum injection, rituximab,2 and alprostadil4 have been attempted without clear effect.

We considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in our patient, which was ruled out because the syndrome typically occurs in the setting of a worsening underlying malignancy7; our patient’s cancer was stable to improved. Thromboangiitis obliterans was ruled out by the absence of a characteristic thrombus on biopsy, the patient’s older age, and involvement of the nose.

We report an unusual case of acral necrosis occurring as a DIRE in response to administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Further description is needed to clarify the diagnostic criteria for and treatment of this rare autoimmune phenomenon.

- Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:449. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5661-x

- Padda A, Schiopu E, Sovich J, et al. Ipilimumab induced digital vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:12. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0321-2

- Comont T, Sibaud V, Mourey L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related acral vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:120. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0443-6

- Gambichler T, Strutzmann S, Tannapfel A, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:327. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3313-6

- Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:165. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6

- Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.021

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:47-52. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120474

To the Editor:

A 67-year-old woman presented to the hospital with painful hands and feet. Two weeks prior, the patient experienced a few days of intermittent purple discoloration of the fingers, followed by black discoloration of the fingers, toes, and nose with notable pain. She reported no illness preceding the presenting symptoms, and there was no progression of symptoms in the days preceding presentation.

The patient had a history of smoking. She had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as recurrent non–small cell lung cancer that was treated most recently with a 1-year course of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab (last treatment was 4 months prior to the current presentation).

Physical examination revealed necrosis of the tips of the second, third, and fourth fingers of the left hand, as well as the tips of the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, progressing to purpura proximally on all involved fingers (Figure, A); scattered purpura and necrotic papules on the toe pads (Figure, B); and a 2- to 3-cm black plaque on the nasal tip. The patient was afebrile.

An embolic and vascular workup was performed. Transthoracic echocardiography was negative for thrombi, ankle brachial indices were within reference range, and computed tomography angiography revealed a few nonocclusive coronary plaques. Conventional angiography was not performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mildly elevated level of cryofibrinogens (cryocrit, 2.5%); cold agglutinins (1:32); mild monoclonal κ IgG gammopathy (0.1 g/dL); and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, 76 mg/L [reference range, 0–10 mg/L]; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; fibrinogen, 571 mg/dL [reference range, 150–450 mg/dL]; and ferritin, 394 ng/mL [reference range, 10–180 ng/mL]). Additional laboratory studies were negative or within reference range, including tests of anti-RNA polymerase antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3), cryoglobulins, and complement; human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C virus serologic studies; prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and lupus anticoagulant; and a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel.

A skin biopsy adjacent to an area of necrosis on the finger showed thickened walls of dermal vessels, sparse leukocytoclastic debris, and evidence of recanalizing medium-sized vessels. Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Based on the clinical history and histologic findings showing an absence of vasculitis, a diagnosis of acral necrosis associated with the PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab—a delayed immune-related event (DIRE)—was favored. The calcium channel blocker amlodipine was started at a dosage of 2.5 mg/d orally. Necrosis of the toes resolved over the course of 1 week; however, necrosis of the fingers remained unchanged. After 1 week of hospitalization, the patient was discharged at her request.

Acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been reported as a rare and recalcitrant immune-related adverse event (AE).1-4 However, our patient’s symptoms occurred months after treatment was discontinued, which is consistent with a DIRE.5 The course of acral necrosis begins with acrocyanosis (a Raynaud disease–like phenomenon) of the fingers that progresses to necrosis. A history of Raynaud disease or other autoimmune disorder generally is absent.1 Our patient’s history indicated actively smoking at the time of presentation, similar to a case described by Khaddour et al.1 Similarly, in a case presented by Comont et al,3 the patient also had a history of smoking. In a recent study of acute vascular events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 16 of 31 patients had a history of smoking.6

No definitive diagnostic laboratory or pathologic findings are associated with acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Histopathologic analysis does not demonstrate vasculitis or other overt vascular pathology.2,3

The optimal treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated digital necrosis is unclear. Corticosteroids and discontinuation of the immune checkpoint inhibitor generally are employed,1-4 though treatment response has been variable. Other therapies such as calcium channel blockers (as in our case), sympathectomy,1 epoprostenol, botulinum injection, rituximab,2 and alprostadil4 have been attempted without clear effect.

We considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in our patient, which was ruled out because the syndrome typically occurs in the setting of a worsening underlying malignancy7; our patient’s cancer was stable to improved. Thromboangiitis obliterans was ruled out by the absence of a characteristic thrombus on biopsy, the patient’s older age, and involvement of the nose.

We report an unusual case of acral necrosis occurring as a DIRE in response to administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Further description is needed to clarify the diagnostic criteria for and treatment of this rare autoimmune phenomenon.

To the Editor:

A 67-year-old woman presented to the hospital with painful hands and feet. Two weeks prior, the patient experienced a few days of intermittent purple discoloration of the fingers, followed by black discoloration of the fingers, toes, and nose with notable pain. She reported no illness preceding the presenting symptoms, and there was no progression of symptoms in the days preceding presentation.

The patient had a history of smoking. She had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as recurrent non–small cell lung cancer that was treated most recently with a 1-year course of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab (last treatment was 4 months prior to the current presentation).

Physical examination revealed necrosis of the tips of the second, third, and fourth fingers of the left hand, as well as the tips of the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, progressing to purpura proximally on all involved fingers (Figure, A); scattered purpura and necrotic papules on the toe pads (Figure, B); and a 2- to 3-cm black plaque on the nasal tip. The patient was afebrile.

An embolic and vascular workup was performed. Transthoracic echocardiography was negative for thrombi, ankle brachial indices were within reference range, and computed tomography angiography revealed a few nonocclusive coronary plaques. Conventional angiography was not performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mildly elevated level of cryofibrinogens (cryocrit, 2.5%); cold agglutinins (1:32); mild monoclonal κ IgG gammopathy (0.1 g/dL); and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, 76 mg/L [reference range, 0–10 mg/L]; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; fibrinogen, 571 mg/dL [reference range, 150–450 mg/dL]; and ferritin, 394 ng/mL [reference range, 10–180 ng/mL]). Additional laboratory studies were negative or within reference range, including tests of anti-RNA polymerase antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3), cryoglobulins, and complement; human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C virus serologic studies; prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and lupus anticoagulant; and a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel.

A skin biopsy adjacent to an area of necrosis on the finger showed thickened walls of dermal vessels, sparse leukocytoclastic debris, and evidence of recanalizing medium-sized vessels. Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Based on the clinical history and histologic findings showing an absence of vasculitis, a diagnosis of acral necrosis associated with the PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab—a delayed immune-related event (DIRE)—was favored. The calcium channel blocker amlodipine was started at a dosage of 2.5 mg/d orally. Necrosis of the toes resolved over the course of 1 week; however, necrosis of the fingers remained unchanged. After 1 week of hospitalization, the patient was discharged at her request.

Acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been reported as a rare and recalcitrant immune-related adverse event (AE).1-4 However, our patient’s symptoms occurred months after treatment was discontinued, which is consistent with a DIRE.5 The course of acral necrosis begins with acrocyanosis (a Raynaud disease–like phenomenon) of the fingers that progresses to necrosis. A history of Raynaud disease or other autoimmune disorder generally is absent.1 Our patient’s history indicated actively smoking at the time of presentation, similar to a case described by Khaddour et al.1 Similarly, in a case presented by Comont et al,3 the patient also had a history of smoking. In a recent study of acute vascular events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 16 of 31 patients had a history of smoking.6

No definitive diagnostic laboratory or pathologic findings are associated with acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Histopathologic analysis does not demonstrate vasculitis or other overt vascular pathology.2,3

The optimal treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated digital necrosis is unclear. Corticosteroids and discontinuation of the immune checkpoint inhibitor generally are employed,1-4 though treatment response has been variable. Other therapies such as calcium channel blockers (as in our case), sympathectomy,1 epoprostenol, botulinum injection, rituximab,2 and alprostadil4 have been attempted without clear effect.

We considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in our patient, which was ruled out because the syndrome typically occurs in the setting of a worsening underlying malignancy7; our patient’s cancer was stable to improved. Thromboangiitis obliterans was ruled out by the absence of a characteristic thrombus on biopsy, the patient’s older age, and involvement of the nose.

We report an unusual case of acral necrosis occurring as a DIRE in response to administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Further description is needed to clarify the diagnostic criteria for and treatment of this rare autoimmune phenomenon.

- Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:449. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5661-x

- Padda A, Schiopu E, Sovich J, et al. Ipilimumab induced digital vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:12. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0321-2

- Comont T, Sibaud V, Mourey L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related acral vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:120. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0443-6

- Gambichler T, Strutzmann S, Tannapfel A, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:327. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3313-6

- Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:165. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6

- Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.021

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:47-52. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120474

- Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:449. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5661-x

- Padda A, Schiopu E, Sovich J, et al. Ipilimumab induced digital vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:12. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0321-2

- Comont T, Sibaud V, Mourey L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related acral vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:120. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0443-6

- Gambichler T, Strutzmann S, Tannapfel A, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:327. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3313-6

- Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:165. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6

- Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.021

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:47-52. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120474

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware of acral necrosis as a rare adverse event of treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

- Delayed immune-related events are sequelae of immune checkpoint inhibitors that can occur months after treatment is discontinued.

Eruptive Keratoacanthomas After Nivolumab Treatment of Stage III Melanoma

To the Editor:

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors have been widely used in the treatment of various cancers. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed cell death-ligand 2 located on cancer cells will bind to PD-1 receptors on T cells and suppress them, which will prevent cancer cell destruction. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors block the binding of PD-L1 to cancer cells, which then prevents T-cell immunosuppression.1 However, cutaneous adverse effects have been associated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatitis associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy occurs more frequently in patients with cutaneous tumors such as melanoma compared to those with head and neck cancers.2 Curry et al1 reported that treatment with an immune checkpoint blockade can lead to immune-related adverse effects, most commonly affecting the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and skin. The same report cited dermatologic toxicity as an adverse effect in approximately 39% of patients treated with anti–PD-1 and approximately 17% of anti–PD-L1.1 The 4 main categories of dermatologic toxicities to immunotherapies in general include inflammatory disorders, immunobullous disorders, alterations of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes. The most common adverse effects from the use of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab were skin rashes, not otherwise specified (14%–20%), pruritus (13%–18%), and vitiligo (~8%).1 Of the cutaneous dermatitic reactions to PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors that were biopsied, the 2 most common were lichenoid dermatitis and spongiotic dermatitis.2 Seldomly, there have been reports of keratoacanthomas (KAs) in association with anti–PD-1 therapy.3

A KA is a common skin tumor that appears most frequently as a solitary lesion and is thought to arise from the hair follicle.4 It resembles squamous cell carcinoma and commonly regresses within months without intervention. Exposure to UV light is a known risk factor for the development of KAs.

Eruptive KAs have been found in association with 10 cases of various cancers treated with the PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab.3 Multiple lesions on photodistributed areas of the body were reported in all 10 cases. Various treatments were used in these 10 cases—doxycycline and niacinamide, electrodesiccation and curettage, clobetasol ointment and/or intralesional triamcinolone, cryotherapy, imiquimod, or no treatment—as well as the cessation of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, with 4 cases continuing therapy and 6 cases discontinuing therapy. Nine cases regressed by 6 months; electrodesiccation and curettage of the lesions was used in the tenth case.3 We report a case of eruptive KA after 1 cycle of nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma.

A 79-year-old woman with stage III melanoma presented to her dermatologist after developing generalized pruritic lichenoid eruptions involving the torso, arms, and legs, as well as erosions on the lips, buccal mucosa, and palate 1 month after starting nivolumab therapy. The patient initially presented to dermatology with an irregularly shaped lesion on the left upper back 3 months prior. Biopsy results at that time revealed a diagnosis of malignant melanoma, lentigo maligna type. The lesion was 1.5-mm thick and classified as Clark level IV with a mitotic count of 6 per mm2. Molecular genetic studies showed expression of PD-L1 and no expression of c-KIT. The patient underwent wide local excision, and a sentinel lymph node biopsy was positive. Positron emission tomography did not show any hypermetabolic lesions, and magnetic resonance imaging did not indicate brain metastasis. The patient underwent an axillary dissection, which did not show any residual melanoma. She was started on adjuvant immunotherapy with intravenous nivolumab 480 mg monthly and developed pruritic crusted lesions on the arms, legs, and torso 1 month later, which prompted follow-up to dermatology.

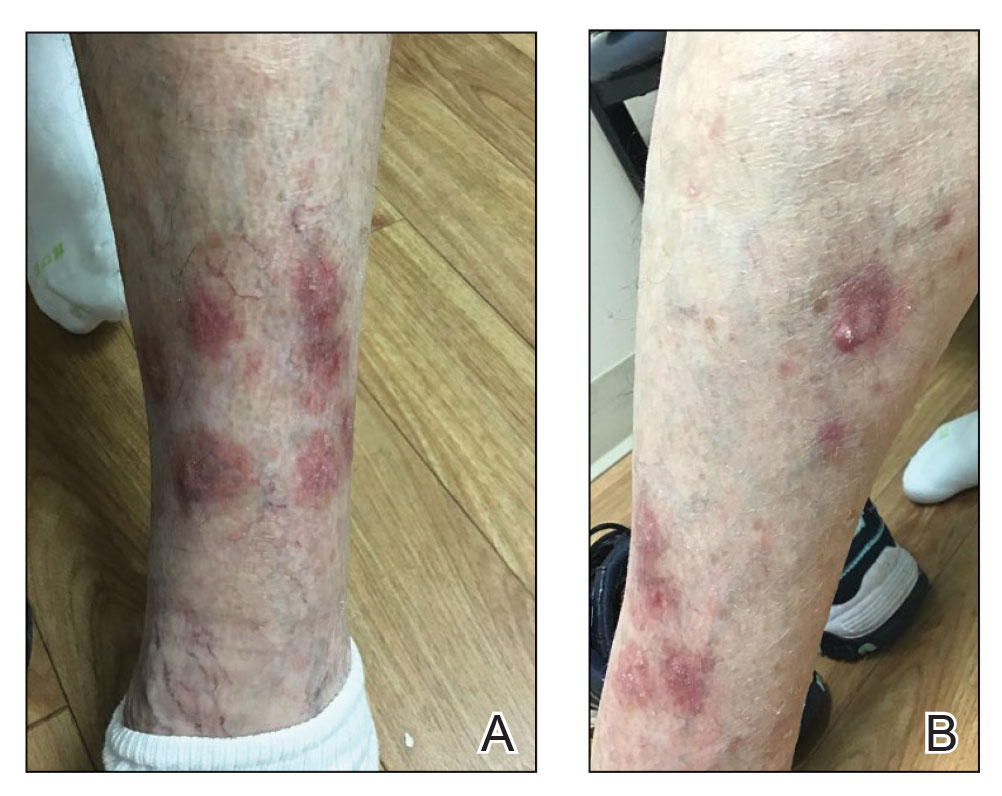

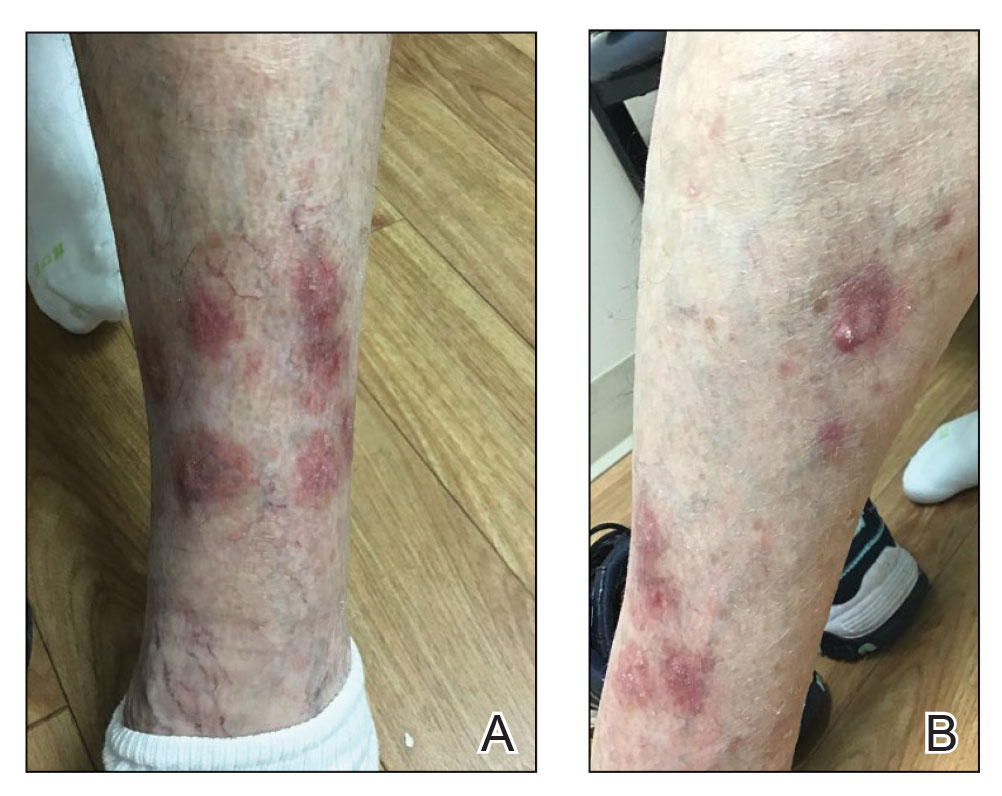

At the current presentation 4 months after the onset of lesions, physical examination revealed lichenoid patches with serous crusting that were concentrated on the torso but also affected the arms and legs. She developed erosions on the upper and lower lips, buccal mucosa, and hard and soft palates, as well as painful, erythematous, dome-shaped papules and nodules on the legs (Figure 1). Her oncologist previously had initiated treatment at the onset of the lesions with clobetasol cream and valacyclovir for the lesions, but the patient showed no improvement.

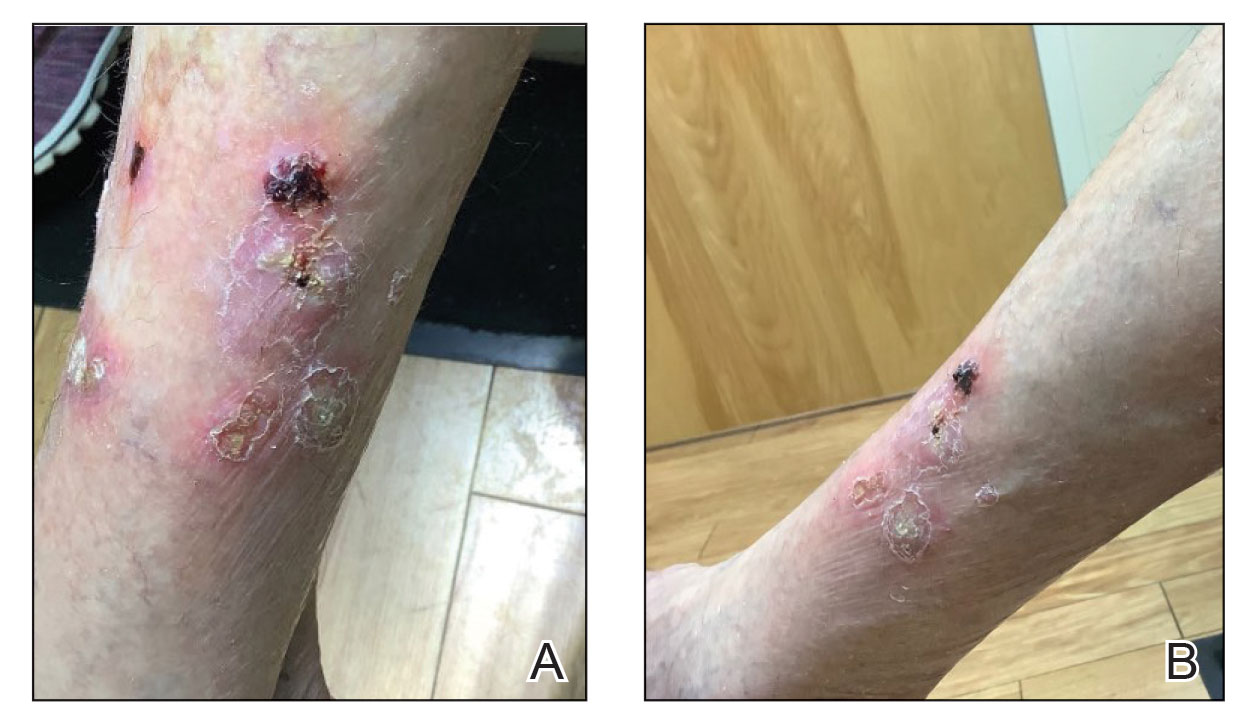

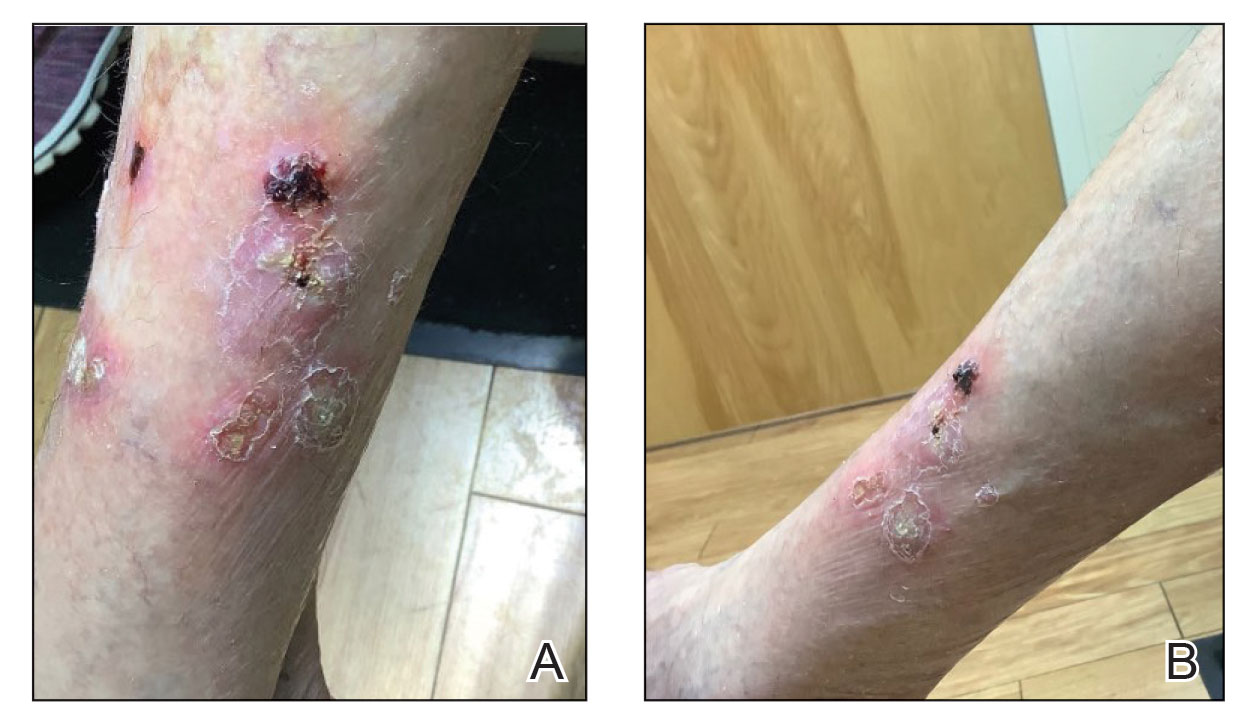

Four months after the onset of the lesions, the patient was re-referred to her dermatologist, and a biopsy was performed on the left lower leg that showed squamous cell carcinoma, KA type. Additionally, flat erythematous patches were seen on the legs that were consistent with a lichenoid drug eruption. Two weeks later, she was started on halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% for treatment of the KAs. At 2-week follow-up, 5 months after the onset of the lesions, the patient showed no signs of improvement. An oral prednisone taper of 60 mg for 3 days, 40 mg for 3 days, and then 20 mg daily for a total of 4 weeks was started to treat the lichenoid dermatitis and eruptive KAs. At the next follow-up 6.5 months following the first eruptive KAs, she was no longer using topical or oral steroids, she did not have any new eruptive KAs, and old lesions showed regression (Figure 2). The patient still experienced postinflammatory erythema and hyperpigmentation at the location of the KAs but showed improvement of the lichenoid drug eruption.

We describe a case of eruptive KAs after use of a PD-1 inhibitor for treatment of melanoma. Our patient developed eruptive KAs after only 1 nivolumab treatment. Another report described onset of eruptive KAs after 1 month of nivolumab infusions.3 The KAs experienced by our patient took 6.5 months to regress, which is unusual compared to other case reports in which the KAs self-resolved within a few months, though one other case described lesions that persisted for 6 months.3

Our patient was treated with topical steroids and an oral steroid taper for the concomitant lichenoid drug eruption. It is unknown if the steroids affected the course of the KAs or if they spontaneously regressed on their own. Freites-Martinez et al5 described that regression of KAs may be related to an immune response, but corticosteroids are inherently immunosuppressive. They hypothesized that corticosteroids help to temper the heightened immune response of eruptive KAs.5

Our patient had oral ulcers, which may have been indicative of an oral lichenoid drug eruption, as well as skin lesions representative of a cutaneous lichenoid drug eruption. This is a favorable reaction, as lichenoid dermatitis is thought to represent successful PD-1 inhibition and therefore a better response to oncologic therapies.2 Comorbid lichenoid drug eruption lesions and eruptive KAs may be suggestive of increased T-cell activity,2,6,7 though some prior case studies have reported eruptive KAs in isolation.3

Discontinuation of immunotherapy due to development of eruptive KAs presents a challenge in the treatment of underlying malignancies such as melanoma. Immunotherapy was discontinued in 7 of 11 cases due to these cutaneous reactions.3 Similarly, our patient underwent only 1 cycle of immunotherapy before developing eruptive KAs and discontinuing PD-1 inhibitor therapy. If we are better able to treat eruptive KAs, then patients can remain on immunotherapy to treat underlying malignancies. Crow et al8 showed improvement in lesions when 3 patients with eruptive KAs were treated with hydroxychloroquine; the Goeckerman regimen consisting of steroids, UVB phototherapy, and crude coal tar; and Unna boots with zinc oxide and compression stockings. The above may be added to a list of possible treatments to consider for hastening the regression of eruptive KAs.

Our patient’s clinical course was similar to reports on the regressive nature of eruptive KAs within 6 months after initial eruption. Although it is likely that KAs will regress on their own, treatment modalities that speed up recovery are a future source for research.

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176.

- Min Lee CK, Li S, Tran DC, et al. Characterization of dermatitis after PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy and association with multiple oncologic outcomes: a retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1047-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.035

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233.

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Bednarek R, Marks K, Lin G. Eruptive keratoacanthomas secondary to nivolumab immunotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:E28-E29.

- Feldstein SI, Patel F, Kim E, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas arising in the setting of lichenoid toxicity after programmed cell death 1 inhibition with nivolumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E58-E59.

- Crow LD, Perkins I, Twigg AR, et al. Treatment of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-induced dermatitis resolves concomitant eruptive keratoacanthomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:598-600. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0176

To the Editor:

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors have been widely used in the treatment of various cancers. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed cell death-ligand 2 located on cancer cells will bind to PD-1 receptors on T cells and suppress them, which will prevent cancer cell destruction. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors block the binding of PD-L1 to cancer cells, which then prevents T-cell immunosuppression.1 However, cutaneous adverse effects have been associated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatitis associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy occurs more frequently in patients with cutaneous tumors such as melanoma compared to those with head and neck cancers.2 Curry et al1 reported that treatment with an immune checkpoint blockade can lead to immune-related adverse effects, most commonly affecting the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and skin. The same report cited dermatologic toxicity as an adverse effect in approximately 39% of patients treated with anti–PD-1 and approximately 17% of anti–PD-L1.1 The 4 main categories of dermatologic toxicities to immunotherapies in general include inflammatory disorders, immunobullous disorders, alterations of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes. The most common adverse effects from the use of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab were skin rashes, not otherwise specified (14%–20%), pruritus (13%–18%), and vitiligo (~8%).1 Of the cutaneous dermatitic reactions to PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors that were biopsied, the 2 most common were lichenoid dermatitis and spongiotic dermatitis.2 Seldomly, there have been reports of keratoacanthomas (KAs) in association with anti–PD-1 therapy.3

A KA is a common skin tumor that appears most frequently as a solitary lesion and is thought to arise from the hair follicle.4 It resembles squamous cell carcinoma and commonly regresses within months without intervention. Exposure to UV light is a known risk factor for the development of KAs.

Eruptive KAs have been found in association with 10 cases of various cancers treated with the PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab.3 Multiple lesions on photodistributed areas of the body were reported in all 10 cases. Various treatments were used in these 10 cases—doxycycline and niacinamide, electrodesiccation and curettage, clobetasol ointment and/or intralesional triamcinolone, cryotherapy, imiquimod, or no treatment—as well as the cessation of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, with 4 cases continuing therapy and 6 cases discontinuing therapy. Nine cases regressed by 6 months; electrodesiccation and curettage of the lesions was used in the tenth case.3 We report a case of eruptive KA after 1 cycle of nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma.

A 79-year-old woman with stage III melanoma presented to her dermatologist after developing generalized pruritic lichenoid eruptions involving the torso, arms, and legs, as well as erosions on the lips, buccal mucosa, and palate 1 month after starting nivolumab therapy. The patient initially presented to dermatology with an irregularly shaped lesion on the left upper back 3 months prior. Biopsy results at that time revealed a diagnosis of malignant melanoma, lentigo maligna type. The lesion was 1.5-mm thick and classified as Clark level IV with a mitotic count of 6 per mm2. Molecular genetic studies showed expression of PD-L1 and no expression of c-KIT. The patient underwent wide local excision, and a sentinel lymph node biopsy was positive. Positron emission tomography did not show any hypermetabolic lesions, and magnetic resonance imaging did not indicate brain metastasis. The patient underwent an axillary dissection, which did not show any residual melanoma. She was started on adjuvant immunotherapy with intravenous nivolumab 480 mg monthly and developed pruritic crusted lesions on the arms, legs, and torso 1 month later, which prompted follow-up to dermatology.

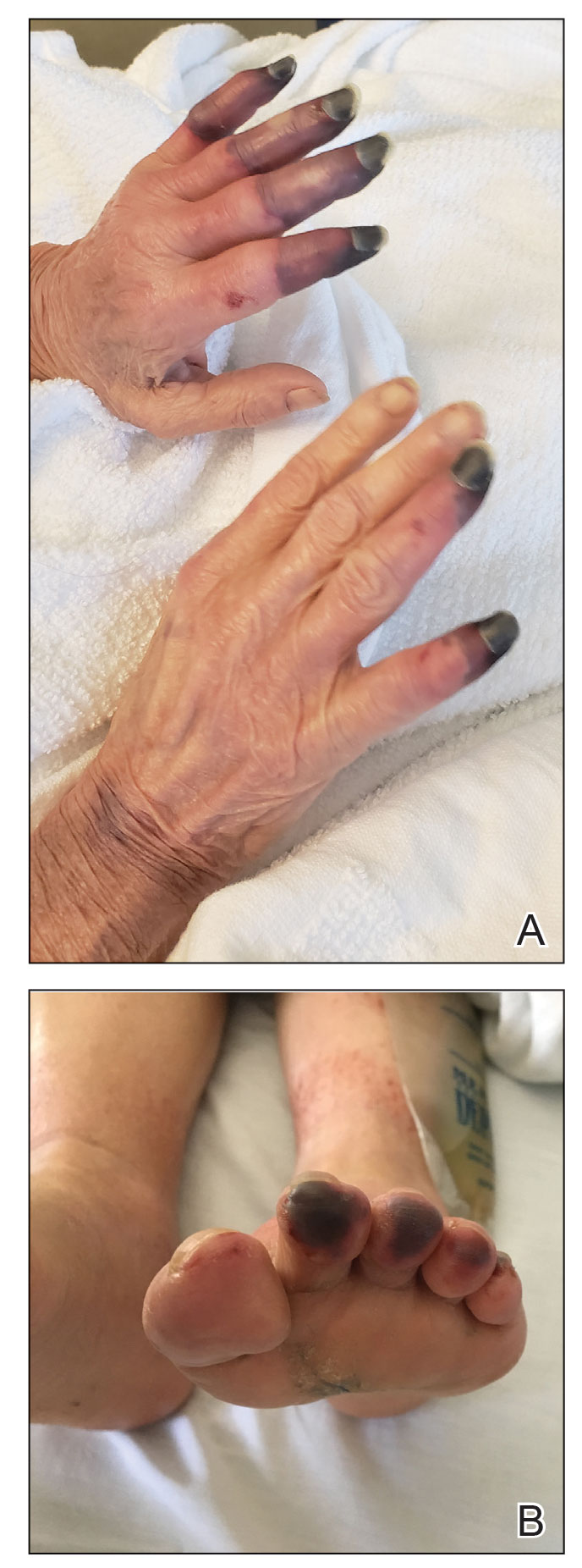

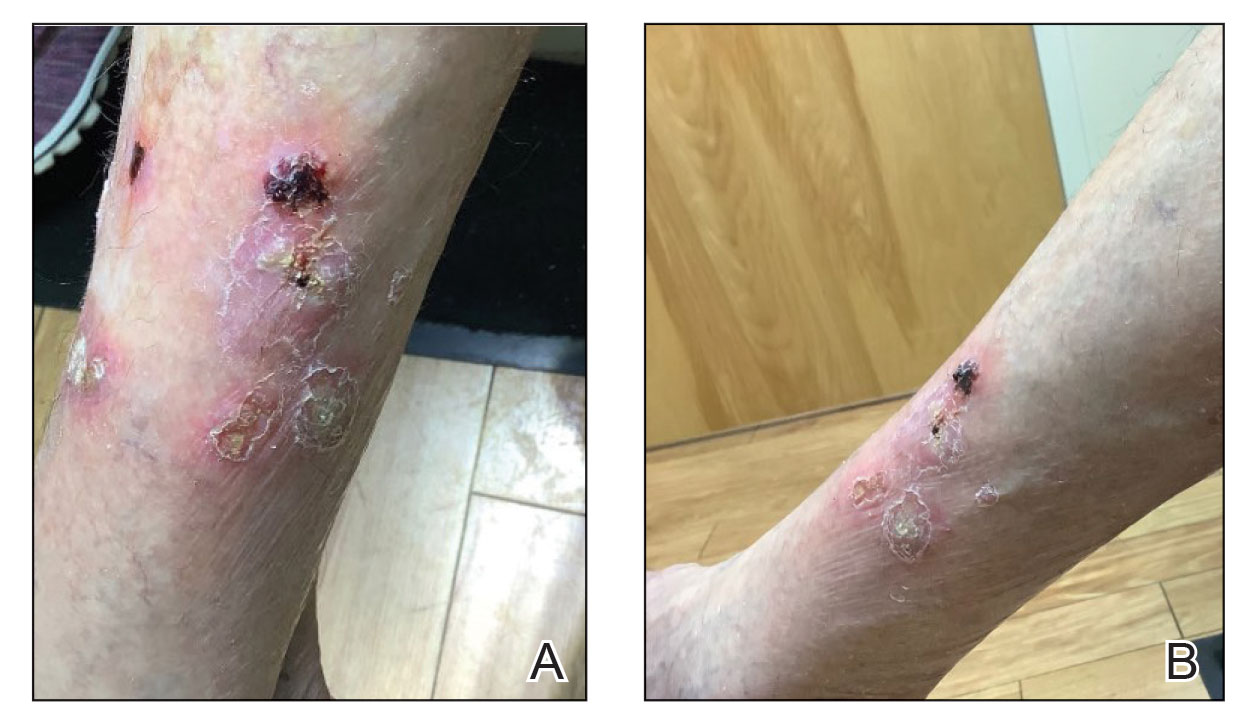

At the current presentation 4 months after the onset of lesions, physical examination revealed lichenoid patches with serous crusting that were concentrated on the torso but also affected the arms and legs. She developed erosions on the upper and lower lips, buccal mucosa, and hard and soft palates, as well as painful, erythematous, dome-shaped papules and nodules on the legs (Figure 1). Her oncologist previously had initiated treatment at the onset of the lesions with clobetasol cream and valacyclovir for the lesions, but the patient showed no improvement.

Four months after the onset of the lesions, the patient was re-referred to her dermatologist, and a biopsy was performed on the left lower leg that showed squamous cell carcinoma, KA type. Additionally, flat erythematous patches were seen on the legs that were consistent with a lichenoid drug eruption. Two weeks later, she was started on halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% for treatment of the KAs. At 2-week follow-up, 5 months after the onset of the lesions, the patient showed no signs of improvement. An oral prednisone taper of 60 mg for 3 days, 40 mg for 3 days, and then 20 mg daily for a total of 4 weeks was started to treat the lichenoid dermatitis and eruptive KAs. At the next follow-up 6.5 months following the first eruptive KAs, she was no longer using topical or oral steroids, she did not have any new eruptive KAs, and old lesions showed regression (Figure 2). The patient still experienced postinflammatory erythema and hyperpigmentation at the location of the KAs but showed improvement of the lichenoid drug eruption.

We describe a case of eruptive KAs after use of a PD-1 inhibitor for treatment of melanoma. Our patient developed eruptive KAs after only 1 nivolumab treatment. Another report described onset of eruptive KAs after 1 month of nivolumab infusions.3 The KAs experienced by our patient took 6.5 months to regress, which is unusual compared to other case reports in which the KAs self-resolved within a few months, though one other case described lesions that persisted for 6 months.3

Our patient was treated with topical steroids and an oral steroid taper for the concomitant lichenoid drug eruption. It is unknown if the steroids affected the course of the KAs or if they spontaneously regressed on their own. Freites-Martinez et al5 described that regression of KAs may be related to an immune response, but corticosteroids are inherently immunosuppressive. They hypothesized that corticosteroids help to temper the heightened immune response of eruptive KAs.5

Our patient had oral ulcers, which may have been indicative of an oral lichenoid drug eruption, as well as skin lesions representative of a cutaneous lichenoid drug eruption. This is a favorable reaction, as lichenoid dermatitis is thought to represent successful PD-1 inhibition and therefore a better response to oncologic therapies.2 Comorbid lichenoid drug eruption lesions and eruptive KAs may be suggestive of increased T-cell activity,2,6,7 though some prior case studies have reported eruptive KAs in isolation.3

Discontinuation of immunotherapy due to development of eruptive KAs presents a challenge in the treatment of underlying malignancies such as melanoma. Immunotherapy was discontinued in 7 of 11 cases due to these cutaneous reactions.3 Similarly, our patient underwent only 1 cycle of immunotherapy before developing eruptive KAs and discontinuing PD-1 inhibitor therapy. If we are better able to treat eruptive KAs, then patients can remain on immunotherapy to treat underlying malignancies. Crow et al8 showed improvement in lesions when 3 patients with eruptive KAs were treated with hydroxychloroquine; the Goeckerman regimen consisting of steroids, UVB phototherapy, and crude coal tar; and Unna boots with zinc oxide and compression stockings. The above may be added to a list of possible treatments to consider for hastening the regression of eruptive KAs.

Our patient’s clinical course was similar to reports on the regressive nature of eruptive KAs within 6 months after initial eruption. Although it is likely that KAs will regress on their own, treatment modalities that speed up recovery are a future source for research.

To the Editor:

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors have been widely used in the treatment of various cancers. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed cell death-ligand 2 located on cancer cells will bind to PD-1 receptors on T cells and suppress them, which will prevent cancer cell destruction. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors block the binding of PD-L1 to cancer cells, which then prevents T-cell immunosuppression.1 However, cutaneous adverse effects have been associated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatitis associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy occurs more frequently in patients with cutaneous tumors such as melanoma compared to those with head and neck cancers.2 Curry et al1 reported that treatment with an immune checkpoint blockade can lead to immune-related adverse effects, most commonly affecting the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and skin. The same report cited dermatologic toxicity as an adverse effect in approximately 39% of patients treated with anti–PD-1 and approximately 17% of anti–PD-L1.1 The 4 main categories of dermatologic toxicities to immunotherapies in general include inflammatory disorders, immunobullous disorders, alterations of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes. The most common adverse effects from the use of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab were skin rashes, not otherwise specified (14%–20%), pruritus (13%–18%), and vitiligo (~8%).1 Of the cutaneous dermatitic reactions to PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors that were biopsied, the 2 most common were lichenoid dermatitis and spongiotic dermatitis.2 Seldomly, there have been reports of keratoacanthomas (KAs) in association with anti–PD-1 therapy.3

A KA is a common skin tumor that appears most frequently as a solitary lesion and is thought to arise from the hair follicle.4 It resembles squamous cell carcinoma and commonly regresses within months without intervention. Exposure to UV light is a known risk factor for the development of KAs.

Eruptive KAs have been found in association with 10 cases of various cancers treated with the PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab.3 Multiple lesions on photodistributed areas of the body were reported in all 10 cases. Various treatments were used in these 10 cases—doxycycline and niacinamide, electrodesiccation and curettage, clobetasol ointment and/or intralesional triamcinolone, cryotherapy, imiquimod, or no treatment—as well as the cessation of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, with 4 cases continuing therapy and 6 cases discontinuing therapy. Nine cases regressed by 6 months; electrodesiccation and curettage of the lesions was used in the tenth case.3 We report a case of eruptive KA after 1 cycle of nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma.

A 79-year-old woman with stage III melanoma presented to her dermatologist after developing generalized pruritic lichenoid eruptions involving the torso, arms, and legs, as well as erosions on the lips, buccal mucosa, and palate 1 month after starting nivolumab therapy. The patient initially presented to dermatology with an irregularly shaped lesion on the left upper back 3 months prior. Biopsy results at that time revealed a diagnosis of malignant melanoma, lentigo maligna type. The lesion was 1.5-mm thick and classified as Clark level IV with a mitotic count of 6 per mm2. Molecular genetic studies showed expression of PD-L1 and no expression of c-KIT. The patient underwent wide local excision, and a sentinel lymph node biopsy was positive. Positron emission tomography did not show any hypermetabolic lesions, and magnetic resonance imaging did not indicate brain metastasis. The patient underwent an axillary dissection, which did not show any residual melanoma. She was started on adjuvant immunotherapy with intravenous nivolumab 480 mg monthly and developed pruritic crusted lesions on the arms, legs, and torso 1 month later, which prompted follow-up to dermatology.

At the current presentation 4 months after the onset of lesions, physical examination revealed lichenoid patches with serous crusting that were concentrated on the torso but also affected the arms and legs. She developed erosions on the upper and lower lips, buccal mucosa, and hard and soft palates, as well as painful, erythematous, dome-shaped papules and nodules on the legs (Figure 1). Her oncologist previously had initiated treatment at the onset of the lesions with clobetasol cream and valacyclovir for the lesions, but the patient showed no improvement.

Four months after the onset of the lesions, the patient was re-referred to her dermatologist, and a biopsy was performed on the left lower leg that showed squamous cell carcinoma, KA type. Additionally, flat erythematous patches were seen on the legs that were consistent with a lichenoid drug eruption. Two weeks later, she was started on halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% for treatment of the KAs. At 2-week follow-up, 5 months after the onset of the lesions, the patient showed no signs of improvement. An oral prednisone taper of 60 mg for 3 days, 40 mg for 3 days, and then 20 mg daily for a total of 4 weeks was started to treat the lichenoid dermatitis and eruptive KAs. At the next follow-up 6.5 months following the first eruptive KAs, she was no longer using topical or oral steroids, she did not have any new eruptive KAs, and old lesions showed regression (Figure 2). The patient still experienced postinflammatory erythema and hyperpigmentation at the location of the KAs but showed improvement of the lichenoid drug eruption.

We describe a case of eruptive KAs after use of a PD-1 inhibitor for treatment of melanoma. Our patient developed eruptive KAs after only 1 nivolumab treatment. Another report described onset of eruptive KAs after 1 month of nivolumab infusions.3 The KAs experienced by our patient took 6.5 months to regress, which is unusual compared to other case reports in which the KAs self-resolved within a few months, though one other case described lesions that persisted for 6 months.3

Our patient was treated with topical steroids and an oral steroid taper for the concomitant lichenoid drug eruption. It is unknown if the steroids affected the course of the KAs or if they spontaneously regressed on their own. Freites-Martinez et al5 described that regression of KAs may be related to an immune response, but corticosteroids are inherently immunosuppressive. They hypothesized that corticosteroids help to temper the heightened immune response of eruptive KAs.5

Our patient had oral ulcers, which may have been indicative of an oral lichenoid drug eruption, as well as skin lesions representative of a cutaneous lichenoid drug eruption. This is a favorable reaction, as lichenoid dermatitis is thought to represent successful PD-1 inhibition and therefore a better response to oncologic therapies.2 Comorbid lichenoid drug eruption lesions and eruptive KAs may be suggestive of increased T-cell activity,2,6,7 though some prior case studies have reported eruptive KAs in isolation.3

Discontinuation of immunotherapy due to development of eruptive KAs presents a challenge in the treatment of underlying malignancies such as melanoma. Immunotherapy was discontinued in 7 of 11 cases due to these cutaneous reactions.3 Similarly, our patient underwent only 1 cycle of immunotherapy before developing eruptive KAs and discontinuing PD-1 inhibitor therapy. If we are better able to treat eruptive KAs, then patients can remain on immunotherapy to treat underlying malignancies. Crow et al8 showed improvement in lesions when 3 patients with eruptive KAs were treated with hydroxychloroquine; the Goeckerman regimen consisting of steroids, UVB phototherapy, and crude coal tar; and Unna boots with zinc oxide and compression stockings. The above may be added to a list of possible treatments to consider for hastening the regression of eruptive KAs.

Our patient’s clinical course was similar to reports on the regressive nature of eruptive KAs within 6 months after initial eruption. Although it is likely that KAs will regress on their own, treatment modalities that speed up recovery are a future source for research.

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176.

- Min Lee CK, Li S, Tran DC, et al. Characterization of dermatitis after PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy and association with multiple oncologic outcomes: a retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1047-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.035

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233.

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Bednarek R, Marks K, Lin G. Eruptive keratoacanthomas secondary to nivolumab immunotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:E28-E29.

- Feldstein SI, Patel F, Kim E, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas arising in the setting of lichenoid toxicity after programmed cell death 1 inhibition with nivolumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E58-E59.

- Crow LD, Perkins I, Twigg AR, et al. Treatment of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-induced dermatitis resolves concomitant eruptive keratoacanthomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:598-600. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0176

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176.

- Min Lee CK, Li S, Tran DC, et al. Characterization of dermatitis after PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy and association with multiple oncologic outcomes: a retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1047-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.035