User login

Case Studies in Toxicology: Double Take—Is Re-exposure Necessary to Explain Delayed Recurrent Opioid Toxicity?

Case

A previously healthy 10-month-old girl was brought to the ED by her mother, who noted that the child had been excessively drowsy throughout the day. She reported that her husband had dropped an unknown amount of his morphine sulfate extended-release 60-mg tablets and oxycodone 10-mg/acetaminophen 325-mg tablets on the floor 5 days earlier. Although unsure of how many tablets he had dropped, the father believed he had located all of them. The mother, however, found some of the tablets around the crib in their daughter’s room.

When the child arrived to the ED, her vital signs were: blood pressure, 95/60 mm Hg; heart rate, 102 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 18 breaths/minute; and temperature, 98.4°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. On physical examination, the child was lethargic, her pupils were less than 1 mm in diameter, and her bowel sounds were absent. After the administration of intravenous (IV) naloxone 0.4 mg, the patient became less drowsy and her RR normalized. Approximately 1 hour later, though, the child again became lethargic; she was given a repeat dose of IV naloxone 0.4 mg, and a naloxone infusion was initiated at 0.3 mg/h. Over approximately 20 hours, the infusion was tapered and discontinued. Three hours after the infusion was stopped, the child’s vital signs and behavior were both normal. After a social worker and representative from the Administration for Children’s Services reviewed the patient’s case, she was discharged home with her parents.

Less than 1 hour later, however, the mother returned to the ED with the child, who was again unresponsive. Although the girl’s RR was normal, she had pinpoint pupils. After she was given IV naloxone 0.4 mg, the child awoke and remained responsive for 20 minutes before returning to a somnolent state. Another IV dose of naloxone 0.4 mg was administered, which showed partial improvement in responsiveness. A naloxone infusion was then initiated and titrated up to 1 mg/h to maintain wakefulness and ventilation. In the pediatric intensive care unit, the child required titration of the naloxone infusion to 2 mg/h to which she responded well. Over the next 12 hours, the infusion was tapered off and the child was discharged home with her parents.

Blood samples from both the initial visit and the return visit were sent for toxicologic analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Serum from the first visit contained morphine at a concentration of 3,000 ng/mL; serum from the second visit contained morphine at 420 ng/mL. Both samples were negative for oxycodone or any of the other substances checked on the extended GC-MS screen.

What is the toxicologic differential?

Although this patient’s extreme somnolence was suspected to be opioid-induced, and was confirmed by an appropriate response to naloxone, children may present to the ED somnolent for a variety of unknown reasons. Even with a fairly clear history, the clinician should also consider metabolic, neurological, infectious, traumatic, and psychiatric causes of altered mental status.1 The toxicologic causes of altered mental status are expansive and include the effects of many medications used therapeutically or in overdose. Opioids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, α-2 agonists (eg, clonidine), sleep aids (eg, zolpidem, diphenhydramine), and ethanol are common causes of induced an altered mental status. When taking a toxicologic history, it is important to inquire not only about the patient’s medications but also the medications of other members of the household to which the patient may have access. This includes not only prescription medications but also over-the-counter, complementary, and herbal preparations.

Why did this child have delayed recurrent opioid toxicity?

When used as directed, opioids cause analgesia and euphoria. Analgesia is mediated by agonism at the μ- , κ-, and δ-opioid receptors throughout the brain and spinal cord. The majority of morphine’s analgesic activity comes from activation of the μ-opioid receptors.2 In overdose, opioids classically cause a toxidrome characterized by miosis, coma, decreased bowel sounds, and respiratory depression. These signs can give clues to a patient’s exposure.

Supportive care is the cornerstone of treatment for patients with opioid toxicity, and maintaining the airway and monitoring the respiratory status are extremely important. When ventilation decreases due to the actions of opioids (typically denoted by a RR of <12 breaths/minute in adults, but may be marked by a reduction in depth of breathing as well), the use of an opioid antagonist is appropriate.4 The most commonly used antagonist is naloxone, an antidote with antagonism at all opioid receptor subtypes.5

In patients who are not dependent on opioids, IV naloxone 0.4 mg is an appropriate initial dose—regardless of patient size or specifics of the exposure. Patients with opioid dependency (eg, patients taking opioids for chronic pain or palliative care, or in those with suspected or confirmed opioid abuse), should receive smaller initial doses of naloxone (eg, 0.04 mg); the dose should be titrated up to effect to avoid precipitating acute opioid withdrawal. The goal of opioid antagonism is to allow the patient to breathe spontaneously and at an appropriate rate and depth without precipitating withdrawal. The duration of action of naloxone is 20 to 90 minutes in adults.

Patients presenting with heroin overdose should be monitored for at least 2 hours after naloxone administration (some suggest 3 hours) to determine whether or not additional dosing will be necessary. After oral opioid exposures, particularly with extended-release or long-acting formulations, longer periods of observation are required (this is unrelated to the naloxone pharmacokinetics, but rather to the slow rise in blood levels from some of these formulations). If repeated opioid toxicity occurs in adults, a naloxone infusion may be helpful to reduce the need for repetitive re-dosing. Initially, an hourly infusion equal to two-thirds of the dose of naloxone that reversed the patient’s respiratory depression is suggested6

Naloxone is eliminated by conjugation with glucuronic acid before is it excreted from the body. Due to decreased hepatic conjugation and prolonged metabolization of drugs in pediatric patients, naloxone may have a longer half-life in children—especially neonates and infants7; in children, the half-life of naloxone may extend up to three times that of adults.8 This extended half-life can lead to a false sense of assurance that a child is free of opioid effects 120 minutes after receiving naloxone—the time by which an adult patient would likely be without significant systemic effects of naloxone—when in fact the effect of naloxone has not yet sufficiently waned. This in turn may prompt discharge before sufficient time has passed to exclude recrudescence of opioid toxicity: The presence of persistent opioid agonist concentrations in the blood, even at consequential amounts, remains masked by the persistent presence of naloxone.

The goal of opioid antagonism is to allow the patient to breathe spontaneously and at an appropriate rate and depth without precipitating withdrawal. In this patient, it is not surprising that the the ingestion of an extended-relief form of morphine should produce a prolonged opioid effect. At therapeutic concentrations in children (~10 ng/mL), the half-life of morphine is slightly longer than in adults (~3 hours vs 2 hours) and is likely even longer with very high serum concentrations. It is metabolized to morphine 6-glucuronide, which is active and longer lasting than the parent compound. This may account for additional clinical effects beyond the time that the serum morphine concentration falls, and is particularly relevant following immediate-release morphine overdose.

In this case it is also important to consider whether or not the patient was re-exposed to an opioid between the first and second ED visit. The dramatically elevated initial serum morphine concentrations and the relatively appropriate fall in magnitude of the second sample suggest that the recurrence of respiratory depression was not the result of re-exposure. The patient’s recurrent effects, even a day out from exposure, can be explained by the immediate-release morphine exposure and the discharge prior to waning of the naloxone. In children with opioid toxicity, another potential option, though not directly studied, is to administer the long-acting opioid antagonist naltrexone to the patient prior to discharge.

Case Conclusion

When used appropriately and under the correct circumstances, naloxone is safe and effective for the reversal of opioid toxicity. As with any antidote, patients must be appropriately monitored for any adverse effects or recurrence of toxicity. Moreover, the clinician should be mindful of the pharmacokinetic differences between adults and young children and the possibility of a later-than-expected recurrence of opioid toxicity in pediatric patients.

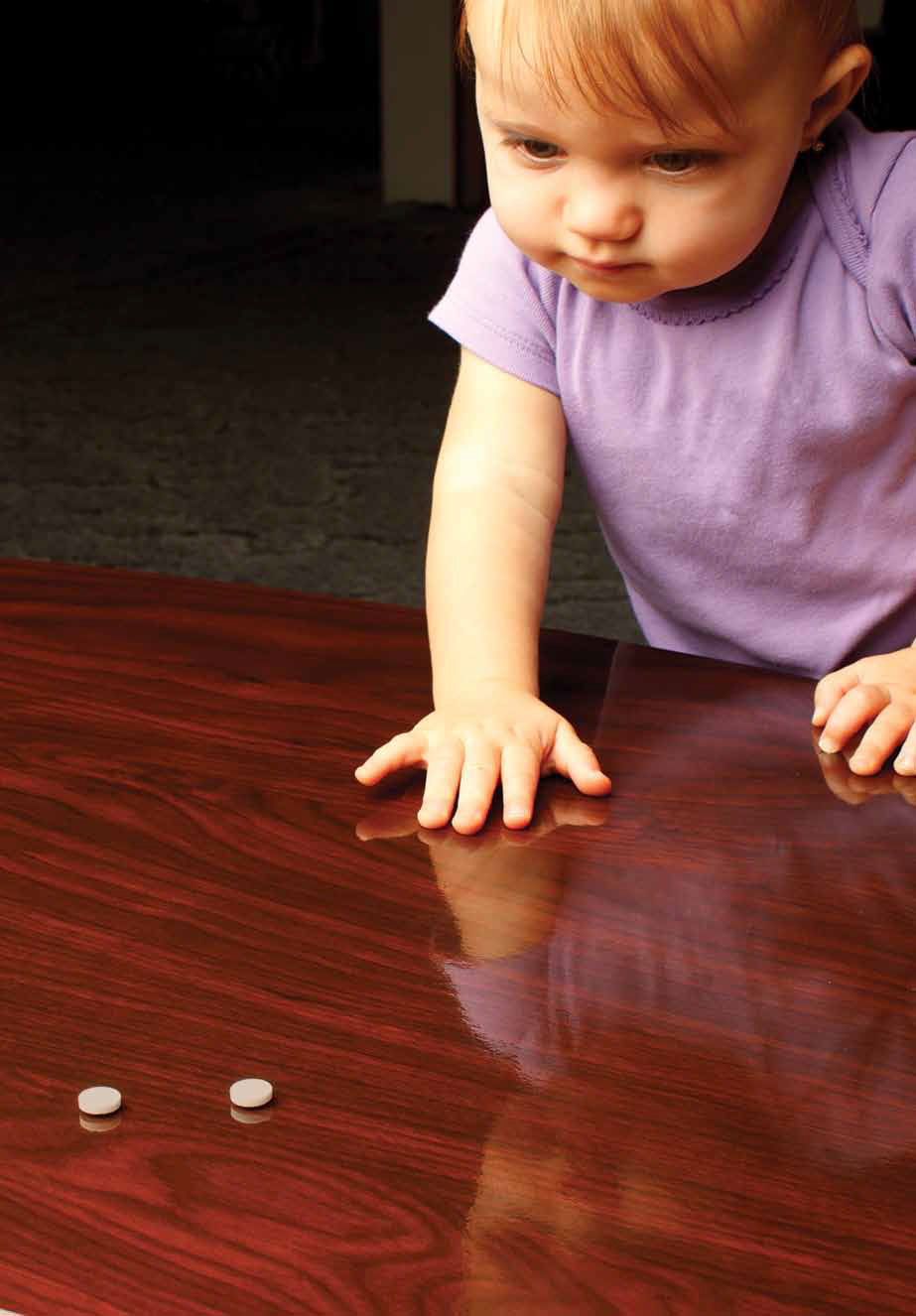

This case is a reminder of the importance of safe medication storage. Infants and young children who are crawling and exploring their environment are especially vulnerable to toxicity from medications found on the floor. Regardless of age, quick recognition of opioid-induced respiratory depression and appropriate use of naloxone can help to decrease the morbidity associated with excessive opioid exposures in all patients.

Dr Berman is a senior medical toxicology fellow at North Shore-Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board. Dr Majlesi is the director of medical toxicology at Staten Island University Hospital, New York.

- Lehman RK, Mink J. Altered mental status. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2008;9:68-75.

- Chang SH, Maney KM, Phillips JP, Langford RM, Mehta V. A comparison of the respiratory effects of oxycodone versus morphine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(10):1007-1012.

- Holstege CP, Borek HA. Toxidromes. Crit Care Clin. 2012;28(4):479-498.

- Hoffman JR, Schriger DL, Luo JS. The empiric use of naloxone in patients with altered mental status: a reappraisal. Ann Emerg Men. 1991;20(3):246-252.

- Howland MA, Nelson LS. Chapter A6. Opioid antagonists. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2011:579-585.

- Goldfrank L, Weisman RS, Errick JK, Lo MW. A dosing nomogram for continuous infusion intravenous naloxone. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):566-570.

- Moreland TA, Brice JE, Walker CH, Parija AC. Naloxone pharmacokinetics in the newborn. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;9(6):609-612.

- Ngai SH, Berkowitz BA, Yang JC, et al. Pharmacokinetics of naloxone in rats and in man: basis for its potency and short duration of action. Anesthesiology. 1976;44(5):398-401.

Case

A previously healthy 10-month-old girl was brought to the ED by her mother, who noted that the child had been excessively drowsy throughout the day. She reported that her husband had dropped an unknown amount of his morphine sulfate extended-release 60-mg tablets and oxycodone 10-mg/acetaminophen 325-mg tablets on the floor 5 days earlier. Although unsure of how many tablets he had dropped, the father believed he had located all of them. The mother, however, found some of the tablets around the crib in their daughter’s room.

When the child arrived to the ED, her vital signs were: blood pressure, 95/60 mm Hg; heart rate, 102 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 18 breaths/minute; and temperature, 98.4°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. On physical examination, the child was lethargic, her pupils were less than 1 mm in diameter, and her bowel sounds were absent. After the administration of intravenous (IV) naloxone 0.4 mg, the patient became less drowsy and her RR normalized. Approximately 1 hour later, though, the child again became lethargic; she was given a repeat dose of IV naloxone 0.4 mg, and a naloxone infusion was initiated at 0.3 mg/h. Over approximately 20 hours, the infusion was tapered and discontinued. Three hours after the infusion was stopped, the child’s vital signs and behavior were both normal. After a social worker and representative from the Administration for Children’s Services reviewed the patient’s case, she was discharged home with her parents.

Less than 1 hour later, however, the mother returned to the ED with the child, who was again unresponsive. Although the girl’s RR was normal, she had pinpoint pupils. After she was given IV naloxone 0.4 mg, the child awoke and remained responsive for 20 minutes before returning to a somnolent state. Another IV dose of naloxone 0.4 mg was administered, which showed partial improvement in responsiveness. A naloxone infusion was then initiated and titrated up to 1 mg/h to maintain wakefulness and ventilation. In the pediatric intensive care unit, the child required titration of the naloxone infusion to 2 mg/h to which she responded well. Over the next 12 hours, the infusion was tapered off and the child was discharged home with her parents.

Blood samples from both the initial visit and the return visit were sent for toxicologic analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Serum from the first visit contained morphine at a concentration of 3,000 ng/mL; serum from the second visit contained morphine at 420 ng/mL. Both samples were negative for oxycodone or any of the other substances checked on the extended GC-MS screen.

What is the toxicologic differential?

Although this patient’s extreme somnolence was suspected to be opioid-induced, and was confirmed by an appropriate response to naloxone, children may present to the ED somnolent for a variety of unknown reasons. Even with a fairly clear history, the clinician should also consider metabolic, neurological, infectious, traumatic, and psychiatric causes of altered mental status.1 The toxicologic causes of altered mental status are expansive and include the effects of many medications used therapeutically or in overdose. Opioids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, α-2 agonists (eg, clonidine), sleep aids (eg, zolpidem, diphenhydramine), and ethanol are common causes of induced an altered mental status. When taking a toxicologic history, it is important to inquire not only about the patient’s medications but also the medications of other members of the household to which the patient may have access. This includes not only prescription medications but also over-the-counter, complementary, and herbal preparations.

Why did this child have delayed recurrent opioid toxicity?

When used as directed, opioids cause analgesia and euphoria. Analgesia is mediated by agonism at the μ- , κ-, and δ-opioid receptors throughout the brain and spinal cord. The majority of morphine’s analgesic activity comes from activation of the μ-opioid receptors.2 In overdose, opioids classically cause a toxidrome characterized by miosis, coma, decreased bowel sounds, and respiratory depression. These signs can give clues to a patient’s exposure.

Supportive care is the cornerstone of treatment for patients with opioid toxicity, and maintaining the airway and monitoring the respiratory status are extremely important. When ventilation decreases due to the actions of opioids (typically denoted by a RR of <12 breaths/minute in adults, but may be marked by a reduction in depth of breathing as well), the use of an opioid antagonist is appropriate.4 The most commonly used antagonist is naloxone, an antidote with antagonism at all opioid receptor subtypes.5

In patients who are not dependent on opioids, IV naloxone 0.4 mg is an appropriate initial dose—regardless of patient size or specifics of the exposure. Patients with opioid dependency (eg, patients taking opioids for chronic pain or palliative care, or in those with suspected or confirmed opioid abuse), should receive smaller initial doses of naloxone (eg, 0.04 mg); the dose should be titrated up to effect to avoid precipitating acute opioid withdrawal. The goal of opioid antagonism is to allow the patient to breathe spontaneously and at an appropriate rate and depth without precipitating withdrawal. The duration of action of naloxone is 20 to 90 minutes in adults.

Patients presenting with heroin overdose should be monitored for at least 2 hours after naloxone administration (some suggest 3 hours) to determine whether or not additional dosing will be necessary. After oral opioid exposures, particularly with extended-release or long-acting formulations, longer periods of observation are required (this is unrelated to the naloxone pharmacokinetics, but rather to the slow rise in blood levels from some of these formulations). If repeated opioid toxicity occurs in adults, a naloxone infusion may be helpful to reduce the need for repetitive re-dosing. Initially, an hourly infusion equal to two-thirds of the dose of naloxone that reversed the patient’s respiratory depression is suggested6

Naloxone is eliminated by conjugation with glucuronic acid before is it excreted from the body. Due to decreased hepatic conjugation and prolonged metabolization of drugs in pediatric patients, naloxone may have a longer half-life in children—especially neonates and infants7; in children, the half-life of naloxone may extend up to three times that of adults.8 This extended half-life can lead to a false sense of assurance that a child is free of opioid effects 120 minutes after receiving naloxone—the time by which an adult patient would likely be without significant systemic effects of naloxone—when in fact the effect of naloxone has not yet sufficiently waned. This in turn may prompt discharge before sufficient time has passed to exclude recrudescence of opioid toxicity: The presence of persistent opioid agonist concentrations in the blood, even at consequential amounts, remains masked by the persistent presence of naloxone.

The goal of opioid antagonism is to allow the patient to breathe spontaneously and at an appropriate rate and depth without precipitating withdrawal. In this patient, it is not surprising that the the ingestion of an extended-relief form of morphine should produce a prolonged opioid effect. At therapeutic concentrations in children (~10 ng/mL), the half-life of morphine is slightly longer than in adults (~3 hours vs 2 hours) and is likely even longer with very high serum concentrations. It is metabolized to morphine 6-glucuronide, which is active and longer lasting than the parent compound. This may account for additional clinical effects beyond the time that the serum morphine concentration falls, and is particularly relevant following immediate-release morphine overdose.

In this case it is also important to consider whether or not the patient was re-exposed to an opioid between the first and second ED visit. The dramatically elevated initial serum morphine concentrations and the relatively appropriate fall in magnitude of the second sample suggest that the recurrence of respiratory depression was not the result of re-exposure. The patient’s recurrent effects, even a day out from exposure, can be explained by the immediate-release morphine exposure and the discharge prior to waning of the naloxone. In children with opioid toxicity, another potential option, though not directly studied, is to administer the long-acting opioid antagonist naltrexone to the patient prior to discharge.

Case Conclusion

When used appropriately and under the correct circumstances, naloxone is safe and effective for the reversal of opioid toxicity. As with any antidote, patients must be appropriately monitored for any adverse effects or recurrence of toxicity. Moreover, the clinician should be mindful of the pharmacokinetic differences between adults and young children and the possibility of a later-than-expected recurrence of opioid toxicity in pediatric patients.

This case is a reminder of the importance of safe medication storage. Infants and young children who are crawling and exploring their environment are especially vulnerable to toxicity from medications found on the floor. Regardless of age, quick recognition of opioid-induced respiratory depression and appropriate use of naloxone can help to decrease the morbidity associated with excessive opioid exposures in all patients.

Dr Berman is a senior medical toxicology fellow at North Shore-Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board. Dr Majlesi is the director of medical toxicology at Staten Island University Hospital, New York.

Case

A previously healthy 10-month-old girl was brought to the ED by her mother, who noted that the child had been excessively drowsy throughout the day. She reported that her husband had dropped an unknown amount of his morphine sulfate extended-release 60-mg tablets and oxycodone 10-mg/acetaminophen 325-mg tablets on the floor 5 days earlier. Although unsure of how many tablets he had dropped, the father believed he had located all of them. The mother, however, found some of the tablets around the crib in their daughter’s room.

When the child arrived to the ED, her vital signs were: blood pressure, 95/60 mm Hg; heart rate, 102 beats/minute; respiratory rate (RR), 18 breaths/minute; and temperature, 98.4°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. On physical examination, the child was lethargic, her pupils were less than 1 mm in diameter, and her bowel sounds were absent. After the administration of intravenous (IV) naloxone 0.4 mg, the patient became less drowsy and her RR normalized. Approximately 1 hour later, though, the child again became lethargic; she was given a repeat dose of IV naloxone 0.4 mg, and a naloxone infusion was initiated at 0.3 mg/h. Over approximately 20 hours, the infusion was tapered and discontinued. Three hours after the infusion was stopped, the child’s vital signs and behavior were both normal. After a social worker and representative from the Administration for Children’s Services reviewed the patient’s case, she was discharged home with her parents.

Less than 1 hour later, however, the mother returned to the ED with the child, who was again unresponsive. Although the girl’s RR was normal, she had pinpoint pupils. After she was given IV naloxone 0.4 mg, the child awoke and remained responsive for 20 minutes before returning to a somnolent state. Another IV dose of naloxone 0.4 mg was administered, which showed partial improvement in responsiveness. A naloxone infusion was then initiated and titrated up to 1 mg/h to maintain wakefulness and ventilation. In the pediatric intensive care unit, the child required titration of the naloxone infusion to 2 mg/h to which she responded well. Over the next 12 hours, the infusion was tapered off and the child was discharged home with her parents.

Blood samples from both the initial visit and the return visit were sent for toxicologic analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Serum from the first visit contained morphine at a concentration of 3,000 ng/mL; serum from the second visit contained morphine at 420 ng/mL. Both samples were negative for oxycodone or any of the other substances checked on the extended GC-MS screen.

What is the toxicologic differential?

Although this patient’s extreme somnolence was suspected to be opioid-induced, and was confirmed by an appropriate response to naloxone, children may present to the ED somnolent for a variety of unknown reasons. Even with a fairly clear history, the clinician should also consider metabolic, neurological, infectious, traumatic, and psychiatric causes of altered mental status.1 The toxicologic causes of altered mental status are expansive and include the effects of many medications used therapeutically or in overdose. Opioids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, α-2 agonists (eg, clonidine), sleep aids (eg, zolpidem, diphenhydramine), and ethanol are common causes of induced an altered mental status. When taking a toxicologic history, it is important to inquire not only about the patient’s medications but also the medications of other members of the household to which the patient may have access. This includes not only prescription medications but also over-the-counter, complementary, and herbal preparations.

Why did this child have delayed recurrent opioid toxicity?

When used as directed, opioids cause analgesia and euphoria. Analgesia is mediated by agonism at the μ- , κ-, and δ-opioid receptors throughout the brain and spinal cord. The majority of morphine’s analgesic activity comes from activation of the μ-opioid receptors.2 In overdose, opioids classically cause a toxidrome characterized by miosis, coma, decreased bowel sounds, and respiratory depression. These signs can give clues to a patient’s exposure.

Supportive care is the cornerstone of treatment for patients with opioid toxicity, and maintaining the airway and monitoring the respiratory status are extremely important. When ventilation decreases due to the actions of opioids (typically denoted by a RR of <12 breaths/minute in adults, but may be marked by a reduction in depth of breathing as well), the use of an opioid antagonist is appropriate.4 The most commonly used antagonist is naloxone, an antidote with antagonism at all opioid receptor subtypes.5

In patients who are not dependent on opioids, IV naloxone 0.4 mg is an appropriate initial dose—regardless of patient size or specifics of the exposure. Patients with opioid dependency (eg, patients taking opioids for chronic pain or palliative care, or in those with suspected or confirmed opioid abuse), should receive smaller initial doses of naloxone (eg, 0.04 mg); the dose should be titrated up to effect to avoid precipitating acute opioid withdrawal. The goal of opioid antagonism is to allow the patient to breathe spontaneously and at an appropriate rate and depth without precipitating withdrawal. The duration of action of naloxone is 20 to 90 minutes in adults.

Patients presenting with heroin overdose should be monitored for at least 2 hours after naloxone administration (some suggest 3 hours) to determine whether or not additional dosing will be necessary. After oral opioid exposures, particularly with extended-release or long-acting formulations, longer periods of observation are required (this is unrelated to the naloxone pharmacokinetics, but rather to the slow rise in blood levels from some of these formulations). If repeated opioid toxicity occurs in adults, a naloxone infusion may be helpful to reduce the need for repetitive re-dosing. Initially, an hourly infusion equal to two-thirds of the dose of naloxone that reversed the patient’s respiratory depression is suggested6

Naloxone is eliminated by conjugation with glucuronic acid before is it excreted from the body. Due to decreased hepatic conjugation and prolonged metabolization of drugs in pediatric patients, naloxone may have a longer half-life in children—especially neonates and infants7; in children, the half-life of naloxone may extend up to three times that of adults.8 This extended half-life can lead to a false sense of assurance that a child is free of opioid effects 120 minutes after receiving naloxone—the time by which an adult patient would likely be without significant systemic effects of naloxone—when in fact the effect of naloxone has not yet sufficiently waned. This in turn may prompt discharge before sufficient time has passed to exclude recrudescence of opioid toxicity: The presence of persistent opioid agonist concentrations in the blood, even at consequential amounts, remains masked by the persistent presence of naloxone.

The goal of opioid antagonism is to allow the patient to breathe spontaneously and at an appropriate rate and depth without precipitating withdrawal. In this patient, it is not surprising that the the ingestion of an extended-relief form of morphine should produce a prolonged opioid effect. At therapeutic concentrations in children (~10 ng/mL), the half-life of morphine is slightly longer than in adults (~3 hours vs 2 hours) and is likely even longer with very high serum concentrations. It is metabolized to morphine 6-glucuronide, which is active and longer lasting than the parent compound. This may account for additional clinical effects beyond the time that the serum morphine concentration falls, and is particularly relevant following immediate-release morphine overdose.

In this case it is also important to consider whether or not the patient was re-exposed to an opioid between the first and second ED visit. The dramatically elevated initial serum morphine concentrations and the relatively appropriate fall in magnitude of the second sample suggest that the recurrence of respiratory depression was not the result of re-exposure. The patient’s recurrent effects, even a day out from exposure, can be explained by the immediate-release morphine exposure and the discharge prior to waning of the naloxone. In children with opioid toxicity, another potential option, though not directly studied, is to administer the long-acting opioid antagonist naltrexone to the patient prior to discharge.

Case Conclusion

When used appropriately and under the correct circumstances, naloxone is safe and effective for the reversal of opioid toxicity. As with any antidote, patients must be appropriately monitored for any adverse effects or recurrence of toxicity. Moreover, the clinician should be mindful of the pharmacokinetic differences between adults and young children and the possibility of a later-than-expected recurrence of opioid toxicity in pediatric patients.

This case is a reminder of the importance of safe medication storage. Infants and young children who are crawling and exploring their environment are especially vulnerable to toxicity from medications found on the floor. Regardless of age, quick recognition of opioid-induced respiratory depression and appropriate use of naloxone can help to decrease the morbidity associated with excessive opioid exposures in all patients.

Dr Berman is a senior medical toxicology fellow at North Shore-Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New York. Dr Nelson, editor of “Case Studies in Toxicology,” is a professor in the department of emergency medicine and director of the medical toxicology fellowship program at the New York University School of Medicine and the New York City Poison Control Center. He is also associate editor, toxicology, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board. Dr Majlesi is the director of medical toxicology at Staten Island University Hospital, New York.

- Lehman RK, Mink J. Altered mental status. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2008;9:68-75.

- Chang SH, Maney KM, Phillips JP, Langford RM, Mehta V. A comparison of the respiratory effects of oxycodone versus morphine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(10):1007-1012.

- Holstege CP, Borek HA. Toxidromes. Crit Care Clin. 2012;28(4):479-498.

- Hoffman JR, Schriger DL, Luo JS. The empiric use of naloxone in patients with altered mental status: a reappraisal. Ann Emerg Men. 1991;20(3):246-252.

- Howland MA, Nelson LS. Chapter A6. Opioid antagonists. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2011:579-585.

- Goldfrank L, Weisman RS, Errick JK, Lo MW. A dosing nomogram for continuous infusion intravenous naloxone. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):566-570.

- Moreland TA, Brice JE, Walker CH, Parija AC. Naloxone pharmacokinetics in the newborn. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;9(6):609-612.

- Ngai SH, Berkowitz BA, Yang JC, et al. Pharmacokinetics of naloxone in rats and in man: basis for its potency and short duration of action. Anesthesiology. 1976;44(5):398-401.

- Lehman RK, Mink J. Altered mental status. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2008;9:68-75.

- Chang SH, Maney KM, Phillips JP, Langford RM, Mehta V. A comparison of the respiratory effects of oxycodone versus morphine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(10):1007-1012.

- Holstege CP, Borek HA. Toxidromes. Crit Care Clin. 2012;28(4):479-498.

- Hoffman JR, Schriger DL, Luo JS. The empiric use of naloxone in patients with altered mental status: a reappraisal. Ann Emerg Men. 1991;20(3):246-252.

- Howland MA, Nelson LS. Chapter A6. Opioid antagonists. In: Nelson LS, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2011:579-585.

- Goldfrank L, Weisman RS, Errick JK, Lo MW. A dosing nomogram for continuous infusion intravenous naloxone. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):566-570.

- Moreland TA, Brice JE, Walker CH, Parija AC. Naloxone pharmacokinetics in the newborn. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;9(6):609-612.

- Ngai SH, Berkowitz BA, Yang JC, et al. Pharmacokinetics of naloxone in rats and in man: basis for its potency and short duration of action. Anesthesiology. 1976;44(5):398-401.

Intragrade Intramedullary Nailing of an Open Tibial Shaft Fracture in a Patient With Concomitant Ipsilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty

Fracture of the tibial shaft below an ipsilateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an infrequently occurring injury pattern that presents a unique treatment scenario. The high predilection for open wounds associated with these diaphyseal fractures further complicates the treatment algorithm.1,2 The standard principles of treatment for open tibial shaft fractures entail open fracture débridement followed by adequate fracture reduction and stable skeletal fixation in a manner that limits adverse complications of this injury, which include nonunion, malunion, infection, soft-tissue compromise, and reoperation.3,4

Antegrade intramedullary (IM) tibial nailing has become standard treatment for tibial shaft fractures.5-7 This minimally invasive method of fixation limits damage to the soft-tissue envelope, provides superior neutralization of the mechanical forces to provide a template for biologic fracture healing, and allows the best options for revision procedures in the event of inadequate healing. This case report examines treatment options for an open tibial shaft fracture of an ipsilateral TKA, complicating the standard treatment of antegrade tibial nailing. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 66-year-old woman became light-headed and fell down a flight of stairs at her home. She was taken to the local emergency room where she presented with left leg pain, deformity, and a skin wound. The wound was dressed with sterile gauze and the extremity immobilized in a temporary plaster splint after which the patient was transferred to our level I trauma center. The accident occurred shortly after dawn, and she received definitive evaluation at the level I trauma center before noon the same day, making the time from injury to evaluation less than 6 hours.

The patient’s medical history was significant for depressive and anxiety disorders, fibromyalgia, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and lymphedema. Her surgical history was significant for a remote left TKA and remote open reduction with internal fixation of a left lateral malleolus fracture. She was prescribed antidepressant and anti-anxiolytic medications, narcotic medication, and antihypertensive therapy. She smoked 1 pack of cigarettes per day for approximately 20 years and denied alcohol consumption or illicit drug use. Her body mass index was 37.5, and she ambulated independently in the community.

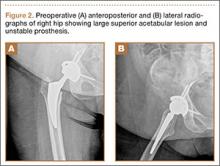

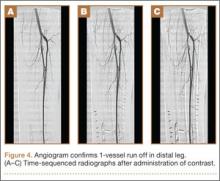

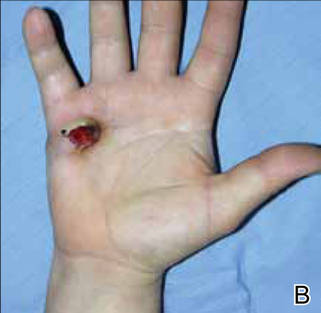

Upon presentation at our hospital, the patient was hemodynamically stable with no discernable systemic compromise from the extremity injury. An examination of the left lower extremity showed a large longitudinal skin wound over the anteromedial surface of the lower leg measuring roughly 10 cm in length with obvious periosteal stripping and protrusion of the proximal fracture segment. Neurologic motor and sensory function was intact in the lower extremities and pulses were strong. Lower leg compartments were soft. Radiographic imaging confirmed a short oblique fracture of the distal third of the tibial diaphysis. The left TKA was intact with no signs of component loosening or periprosthetic fracture (Figures 1A, 1B).

The patient urgently received broad-spectrum antibiotics with intravenous (IV) cefazolin and IV gentamicin as well as tetanus vaccination. Her fracture was temporarily stabilized in a long-leg splint before she was transported to the operating room. Based upon the characteristics of the patient and the open fracture, we had an extensive discussion with the patient regarding the severity of her injury and treatment options, including nonoperative treatment, operative irrigation and débridement with skeletal stabilization, or below-knee amputation. The patient was adamant that limb salvage be attempted despite adequate understanding that she was exposing herself to risk of multiple reoperations from potential complications, as well as systemic medical compromise. Thus, we considered possible techniques for internal fixation of the tibial shaft fracture and treatment of the open wound.

Two primary technical concerns were addressed in the preoperative planning phase: the first was the need for primary closure of the open wound. This patient had a large wound over the anteromedial surface of the distal third of the tibia with scant soft-tissue coverage. Consequently, skin graft alone would not be adequate. While a muscle flap is another option, it would be prone to failure because of the patient’s age and comorbidities, including hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, lymphedema, and tobacco use. Therefore, we hoped to achieve primary closure. Our second major concern was that the method of fixation must be biomechanically sound without impeding our first goal of primary wound closure. In the setting of an ipsilateral TKA, standard antegrade IM nail fixation would not be possible. While we considered plate fixation, it is biomechanically less stable than an IM nail, and we had great concerns about wound complications. External fixation—uniplanar and mutliplanar (eg, Ilizarov)—was limited by issues of long-term fracture stability and risk of pin-site infection. Both methods appeared less desirable compared with IM nail fixation. Thus, we devised an innovative technique to implant an IM nail into the tibial canal.

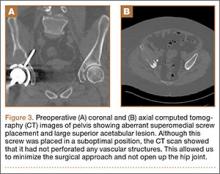

The operative procedure first entailed standard open fracture care comprising débridement of nonviable soft tissue from the traumatic anteromedial tibial wound, curettage of the fractured bone ends, and irrigation with pulse-jet lavage. Then, we turned to reduction and internal fixation of the bony injury. The large traumatic wound was not extended and was used as the primary surgical approach to permit introduction of the IM nail into the canal. Through the traumatic wound, we performed limited reaming of the proximal and distal fracture segments. Using a cannulated technique over guide wires, we reamed to 11 mm (Figure 2). The tourniquet was not used during the IM reaming. We determined the maximum nail length (approximately 22 cm) by measuring the distance from the fracture to the bone interface with the tibial component. We used a 10×200-mm femoral retrograde Synthes nail (Synthes, Inc, West Chester, Pennsylvania) for the procedure, although we considered an IM humerus nail. Through the traumatic wound, the nail was advanced in its entirety into the proximal tibial segment (Figure 3). The fracture was reduced anatomically and held with a bone tenaculum (Figures 4A, 4B). A medial cortical window proximal to the proximal extent of the IM nail was created through which the Synthes IM reduction tool (aluminum femoral finger) was advanced to impact the IM nail antegrade through the fracture site into the distal segment (Figure 5). After placement of the nail was complete, the excised fragment of bone was reinserted into the cortical window. The Synthes IM reduction tool was chosen for its diameter, length, and, most important, its relative flexibility. While maintaining reduction of the fracture, cross-locking of the nail was performed at the distal and proximal ends with perfect circle technique through stab incisions. Length, alignment, and rotation of the affected tibia were deemed symmetric to the contralateral side based on preoperative clinical measurements. Final fluoroscopic images showed appropriate alignment and proper implant placement.

Following open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture, the traumatic and surgical wounds were closed in a layered fashion. A subcutaneous drain and an incisional vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device were applied to the closed traumatic wound, and a second subcutaneous drain was placed at the site of the cortical window. The patient tolerated the procedure well without perioperative complications.

In the acute period after surgery, the patient’s neurologic and vascular status remained stable. Her muscular compartments remained soft and compressible on physical examination, and her pain was well controlled. The incisional VAC and the 2 Hemovac drains were removed within a few days of the operation. Intravenous cefazolin was continued through her hospital stay and she was transitioned to oral cephalexin at discharge as recommended by our infectious disease colleagues to complete a 10-day course of antibiotic therapy.

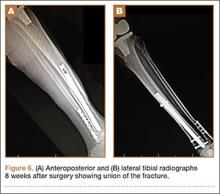

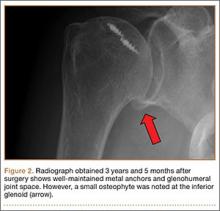

At the time of discharge—within 1 week of her initial injury—the patient’s wounds were dry and she was ambulatory with a walker. She was instructed to remain non-weight-bearing and to keep her wounds clean and dry with follow-up in 2 weeks. Over 6 to 8 weeks after surgery, the patient’s weight-bearing status was gradually advanced to full weight-bearing, and she achieved union of the fracture and uneventful healing of the traumatic wound (Figures 6A, 6B, 7).

Discussion

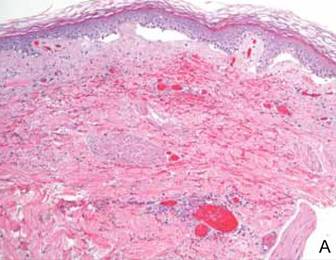

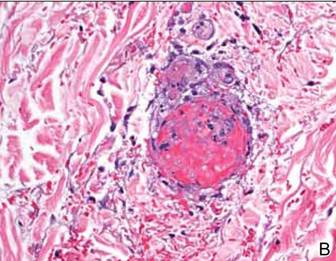

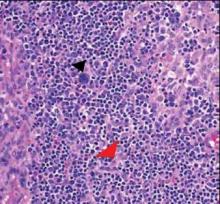

We have presented a case of an open distal-third tibial shaft fracture in a 66-year-old obese woman with an ipsilateral TKA. Open fracture of the tibial shaft is potentially limb-threatening because of the challenging management of the bone and soft-tissue injury. The presence of an ipsilateral TKA adds a degree of complexity. From a biomechanical standpoint, the lower interdigitation of cortical bone, coupled with weight-bearing of the lower extremity, subjects the tibia diaphysis to issues of rotation, length, and angular control.8 Due to the diaphyseal nature of the fracture, consisting of cortical bone with comparably lower vascularity and a small soft-tissue envelope, these fractures heal very slowly and often take as many as 6 to 9 months to achieve union.9,10 Furthermore, as was the case here, short oblique fractures of the tibial shaft often occur under bending stresses that also cause significant damage to the tibial soft-tissue envelope and periosteum, as indicated by the open wound. This disruption deprives the fracture and soft tissues of important vascular supply that is critical to healing and to avoiding infection and soft-tissue necrosis.11-13 The effects of treatment may magnify these biomechanical and biologic consequences. Ideal fixation serves to minimize potential complications by neutralizing the biomechanical forces to permit fracture healing while also limiting the amount of soft-tissue trauma and tension. Because the challenges associated with treatment of open tibial shaft fractures make it a limb-threatening injury in a patient with poor peripheral circulation, it is appropriate to consider primary amputation.14

If circumstances warrant an attempt at limb salvage, IM nailing with static interlocking screws would typically be the standard of care for treatment of an open fracture of the tibia shaft. This provides stable internal fixation that controls tibial alignment in 6° of freedom and neutralizes bending forces with less strain on the implant because of the IM position.15,16 In addition to superior neutralization of the biomechanical forces, IM nailing is also a minimally invasive approach that limits further trauma to the periosteum and soft-tissue envelope surrounding the fracture site. This optimizes biologic fracture healing and minimizes complications of malunion, infection, and nonunion.17-19 Moreover, by limiting further damage to the surrounding soft tissue, there is a diminished need for a plastic surgery procedure to reestablish soft-tissue integrity overlying the fracture site. This is particularly advantageous in patients with medical comorbidities that make skin grafts and muscle flaps less likely to succeed. For these reasons, IM nailing was our preferred method of fixation in our patient; however, the presence of an ipsilateral TKA made this standard treatment through an antegrade approach impossible.

Consequently, we considered other methods of fixation, including internal fixation with plate application or external fixation with a multiplanar construct, such as an Ilizarov frame. Some orthopedists consider plate application a superior technique for achieving fracture union because it results in interfragmentary compression, which promotes primary healing. Interestingly, some would argue that the absolute stability provided by the plate may be too rigid a construct to enable optimal fracture healing biology if compression is not achieved.20 However, to allow primary healing to complete fracture union, absolute stability with rigid and strong fixation must be provided. In the tibial shaft, with large bending forces and rotational moments, this is difficult to achieve with plate fixation alone.8 Furthermore, plate application often requires relatively extensive soft-tissue dissection and may impede biologic factors in healing of the bone and soft tissue, increasing the likelihood of infection.21 Finally, adequate plate fixation would significantly increase the soft-tissue volume at this location, further compromising the soft tissues and impeding our goal of primary wound closure.

A uniplanar or mutliplanar external fixator would be an appealing option for definitive fixation because of minimal additional soft-tissue damage that is created during its application. However, it is difficult to achieve adequate stability to encourage either primary, or more commonly, secondary healing in the adult or elderly population.22 An Ilizarov frame is a multiplanar external construct, which allows reconstructive applications because of multiple points of fixation in bone.23 However, the multiple fixation points result in burdensome size of the implant for the patient and requires patient compliance to minimize risk of pin-site infection, which is magnified in a patient with multiple medical comorbid conditions. Furthermore, when comparing treatment options that aim to minimize additional soft-tissue trauma at the site of injury, there is little evidence to show a lower risk of infection at the open fracture site compared with IM nailing.24,25 Thus, in our patient, customary treatment of an open tibial shaft fracture using antegrade IM nailing was not possible, while plate application and external fixation, though potential treatment options, would be relatively contraindicated due to a higher likelihood of failure.

Consequently, primary amputation may be the most appropriate treatment option in a patient with multiple comorbid medical conditions, including peripheral vascular disease. Primary amputation prevents morbidity and mortality associated with complications related to the aforementioned treatment options, as well as limiting risks associated with multiple reoperations.14,25 Studies illustrate that patient functional outcomes after primary amputation are equal to and, in some cases, superior to those patients undergoing limb salvage procedures for open tibial shaft fractures.26-28

Despite the appropriateness of primary amputation in this case, the patient requested limb salvage. Therefore, other innovative treatment options were explored to achieve our goals of primary wound closure and stable internal fixation. Previous case reports have examined retrograde IM nailing as a means of rigidly fixing tibial shaft fractures in the setting of poor soft tissues or ipsilateral knee arthroplasty.29-31 However, the retrograde approach to IM nailing requires passage of reamers through the subtalar and ankle joints, leading to associated arthritis in these joints or, more commonly, rigidity because the final nail position often crosses these joints in addition to the fracture site. Therefore, a novel approach for IM nailing was performed using the large open-fracture wound. Through the traumatic wound, open-fracture débridement was first performed, followed by placement of a nail into the medullary canal with little additional disruption of the surrounding periosteum or soft tissue.

Possible complications of this novel method for IM nail passage warrant discussion. First, potentially unfavorable aspects associated with IM reaming include impairment of endosteal blood circulation in the subacute postoperative period.32-34 If the patient develops complications, such as deep infection, nonunion, hardware failure, or periprosthetic fracture, treatment options that require removal of the nail would be very difficult to execute because this nail was passed “intragrade,” or through the fracture site, not from the knee or the calcaneus. However, unique to this case of intragrade nailing, complications associated with the proximal cortical window may occur. In particular, unintended cortical fracture may happen during impaction of the nail into the distal segment of the fracture after reduction. However, this complication may be avoided with the use of a 1-cm wide and 2-cm long window and the use of the malleable aluminum femoral finger (Synthes). Furthermore, use of a femoral nail is recommended because the Herzog curve of a tibial nail cannot be inserted in the proximal tibial segment using an “intragrade” nailing technique. However, fracture may occur intraoperatively or during rehabilitation after surgery because the cortical window creates a region of high stress distal to the tibial arthroplasty component. Likewise, the area of bone between the proximal extent of the IM nail and tibial component of the TKA represents an area of high stress susceptible to periprosthetic fracture.

Conclusion

We have presented a case of a high-energy open distal tibial diaphyseal fracture in a 66-year-old woman with medical comorbidities and treatment complicated by the presence of an ipsilateral TKA. Intramedullary nailing has become the standard of care for open fractures of the tibial diaphysis because of the high rate of union with little additional soft-tissue damage at the fracture site. Despite these advantages, the ipsilateral TKA complicated the placement of an antegrade tibial nail. An alternative treatment, such as an external fixation using an Ilizarov frame, would present equally challenging treatment aspects, including patient compliance, with little proven benefit over an IM nail. Application of a plate would be less desirable because of increased risk of infection at the fracture site, soft-tissue and periosteum disruption, and muscle necrosis compared with other treatment options. Primary amputation was an appropriate consideration for this patient given her comorbid medical circumstances, but the patient refused this treatment option. Therefore, we created a novel approach to place an IM nail, using the traumatic wound to achieve access to the medullary canal proximally and distally.

1. Patzakis MJ, Wilkins J. Factors influencing infection rate in open fracture wounds. Clin Orthop. 1989;243:36-40.

2. Court-Brown CM, McBirnie J. The epidemiology of tibial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(3):417-421.

3. Puno RM, Teynor JT, Nagano J, Gustilo RB. Critical analysis of results of treatment of 201 tibial shaft fractures. Clin Orthop. 1986;212:113-121.

4. Melvin JS, Dombroski DG, Torbert JT, Kovach SJ, Esterhal JL, Mehta S. Open tibial shaft fractures: I. Evaluation and initial wound management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(1):10-19.

5. Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Swiontkowski MF, Schemitsch EH. Treatment of open fractures of the shaft of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(1):62-68.

6. SPRINT Investigators, Bhandari M, Guyatt G, Tornetta P 3rd, et al. Study to prospectively evaluate reamed intramedually nails in patients with tibial fractures (S.P.R.I.N.T.): study rationale and design. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:91.

7. Study to Prospectively Evaluate Reamed Intramedullary Nails in Patients with Tibial Fractures Investigators, Bhandari M, Guyatt G, Tornetta P 3rd, et al. Randomized trial of reamed and unreamed intramedullary nailing of tibial shaft fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(12):2567-2578.

8. Burr DB, Milgrom C, Fyhrie D, et al. In vivo measurement of human tibial strains during vigorous activity. Bone. 1996;18(5):405-410.

9. Edwards P. Fracture of the shaft of the tibia: 492 consecutive cases in adults: Importance of soft tissue injury. Acta Orthop Scand (Suppl). 1965;76(suppl 76):1-82.

10. Papakostidis C, Kanakaris NK, Pretel J, Faour O, Morell DJ, Giannoudis PV. Prevalence of complications of open tibial shaft fractures stratified as per the Gustilo–Anderson classification. Injury. 2011;42(12):1408-1415.

11. Gustilo RB, Mendoza RM, Williams DN. Problems in the management of type III (severe) open fractures: a new classification of type III open fractures. J Trauma. 1984;24(8):742-746.

12. DeLong WG Jr, Born CT, Wei SY, Petrik ME, Ponzio R, Schwab CW. Aggressive treatment of 119 open fracture wounds. J Trauma. 1999;46(6):1049-1054.

13. Tielinen L, Lindahl JE, Tukiainen EJ. Acute unreamed intramedullary nailing and soft tissue reconstruction with muscle flaps for the treatment of severe open tibial shaft fractures. Injury. 2007;38(8):906-912.

14. Georgiadis GM, Behrens FF, Joyce MJ, Earle AS, Simmons AL. Open tibial fractures with severe soft-tissue loss. Limb salvage compared with below-the-knee amputation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(10):1431-1441.

15. Hansen M, Mehler D, Hessmann MH, Blum J, Rommens PM. Intramedullary stabilization of extraarticular proximal tibial fractures: a biomechanical comparison of intramedullary and extramedullary implants including a new proximal tibia nail (PTN). J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21(10):701-709.

16. Hoegel FW, Hoffmann S, Weninger P, Bühren V, Augat P. Biomechanical comparison of locked plate osteosynthesis, reamed and unreamed nailing in conventional interlocking technique, and unreamed angle stable nailing in distal tibia fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(4):933-938.

17. Brumback RJ, Reilly JP, Poka A, Lakatos RP, Bathon GH, Burgess AR. Intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures. Part 1: Decision-making errors with interlocking fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(10):1441-1452.

18. Hooper GJ, Keddell RG, Penny ID. Conservative management or closed nailing for tibial shaft fractures. A randomised prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(1):83-85.

19. Karladani AH, Granhed H, Edshage B, Jerre R, Styf J. Displaced tibial shaft fractures: a prospective randomized study of closed intramedullary nailing versus cast treatment in 53 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(12):160-167.

20. Kenwright J, Richardson JB, Goodship AE, et al. Effect of controlled axial micromovement on healing of tibial fractures. Lancet. 1986;22(8517):1185-1187.

21. Im GI, Tae SK. Distal metaphyseal fractures of tibia: a prospective randomized trial of closed reduction and intramedullary nail versus open reduction and plate and screws fixation. J Trauma. 2005;59(5):1219-1223.

22. Henley MB, Chapman JR, Agel J, Harvey EJ, Whorton AM, Swiontkowski MF. Treatment of type II, IIIA, and IIIB open fractures of the tibial shaft: a prospective comparison of unreamed interlocking intramedullary nails and half-pin external fixators. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(1):1-7.

23. Ramos T, Ekholm C, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J, Nistor L. The Ilizarov external fixator - a useful alternative for the treatment of proximal tibial fractures. A prospective observational study of 30 consecutive patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:11.

24. Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Swiontkowski MF, Schemitsch EH. Treatment of open fractures of the shaft of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(1):62-68.

25. Webb LX, Bosse MJ, Castillo RC, MacKenzie EJ; LEAP Study Group. Analysis of surgeon-controlled variables in the treatment of limb-threatening type-III open tibial diaphyseal fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(5):923-928.

26. Bondurant FJ, Cotler HB, Buckle R, Miller-Crotchett P, Browner BD. The medical and economic impact of severely injured lower extremities. J Trauma. 1988;28(8):1270-1273.

27. Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Kellam JF, et al. An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation of leg-threatening injuries. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(24):1924-1931.

28. MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Pollak AN, et al. Long-term persistence of disability following severe lower-limb trauma. Results of a seven-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1801-1809.

29. Doulens KM, Joshi AB, Wagner RA. Tibial fracture after total knee arthroplasty treated with retrograde intramedullary fixation. Am J Orthop. 2007;36(7):E111-E113.

30. Zafra-Jiménez JA, Pretell-Mazzini J, Resines-Erasun C. Distal tibial fracture below a total knee arthroplasty: retrograde intramedullary nailing as an alternative method of treatment: a case report. J Orthop Trauma. 2011;25(7):e74-e76.

31. Loosen S, Preuss S, Zelle BA, Pape HC, Tarken IS. Multimorbid patients with poor soft tissue conditions: Treatment of distal tibia fractures with retrograde intramedullary nailing. Unfallchirurg. 2012;116(6):553-558.

32. Kessler SB, Hallfeldt KJ, Perren SM, Schweiberer L. The effects of reaming and intramedullary nailing on fracture healing. Clin Orthop. 1986;212:18-25.

33. Klein MP, Rahn BA, Frigg R, Kessler S, Perren SM. Reaming versus non-reaming in medullary nailing: interference with cortical circulation of the canine tibia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1990;109(6):314-316.

34. Reichert IL, McCarthy ID, Hughes SP. The acute vascular response to intramedullary reaming. Microsphere estimation of blood flow in the intact ovine tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(3):490-493.

Fracture of the tibial shaft below an ipsilateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an infrequently occurring injury pattern that presents a unique treatment scenario. The high predilection for open wounds associated with these diaphyseal fractures further complicates the treatment algorithm.1,2 The standard principles of treatment for open tibial shaft fractures entail open fracture débridement followed by adequate fracture reduction and stable skeletal fixation in a manner that limits adverse complications of this injury, which include nonunion, malunion, infection, soft-tissue compromise, and reoperation.3,4

Antegrade intramedullary (IM) tibial nailing has become standard treatment for tibial shaft fractures.5-7 This minimally invasive method of fixation limits damage to the soft-tissue envelope, provides superior neutralization of the mechanical forces to provide a template for biologic fracture healing, and allows the best options for revision procedures in the event of inadequate healing. This case report examines treatment options for an open tibial shaft fracture of an ipsilateral TKA, complicating the standard treatment of antegrade tibial nailing. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 66-year-old woman became light-headed and fell down a flight of stairs at her home. She was taken to the local emergency room where she presented with left leg pain, deformity, and a skin wound. The wound was dressed with sterile gauze and the extremity immobilized in a temporary plaster splint after which the patient was transferred to our level I trauma center. The accident occurred shortly after dawn, and she received definitive evaluation at the level I trauma center before noon the same day, making the time from injury to evaluation less than 6 hours.

The patient’s medical history was significant for depressive and anxiety disorders, fibromyalgia, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and lymphedema. Her surgical history was significant for a remote left TKA and remote open reduction with internal fixation of a left lateral malleolus fracture. She was prescribed antidepressant and anti-anxiolytic medications, narcotic medication, and antihypertensive therapy. She smoked 1 pack of cigarettes per day for approximately 20 years and denied alcohol consumption or illicit drug use. Her body mass index was 37.5, and she ambulated independently in the community.

Upon presentation at our hospital, the patient was hemodynamically stable with no discernable systemic compromise from the extremity injury. An examination of the left lower extremity showed a large longitudinal skin wound over the anteromedial surface of the lower leg measuring roughly 10 cm in length with obvious periosteal stripping and protrusion of the proximal fracture segment. Neurologic motor and sensory function was intact in the lower extremities and pulses were strong. Lower leg compartments were soft. Radiographic imaging confirmed a short oblique fracture of the distal third of the tibial diaphysis. The left TKA was intact with no signs of component loosening or periprosthetic fracture (Figures 1A, 1B).

The patient urgently received broad-spectrum antibiotics with intravenous (IV) cefazolin and IV gentamicin as well as tetanus vaccination. Her fracture was temporarily stabilized in a long-leg splint before she was transported to the operating room. Based upon the characteristics of the patient and the open fracture, we had an extensive discussion with the patient regarding the severity of her injury and treatment options, including nonoperative treatment, operative irrigation and débridement with skeletal stabilization, or below-knee amputation. The patient was adamant that limb salvage be attempted despite adequate understanding that she was exposing herself to risk of multiple reoperations from potential complications, as well as systemic medical compromise. Thus, we considered possible techniques for internal fixation of the tibial shaft fracture and treatment of the open wound.

Two primary technical concerns were addressed in the preoperative planning phase: the first was the need for primary closure of the open wound. This patient had a large wound over the anteromedial surface of the distal third of the tibia with scant soft-tissue coverage. Consequently, skin graft alone would not be adequate. While a muscle flap is another option, it would be prone to failure because of the patient’s age and comorbidities, including hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, lymphedema, and tobacco use. Therefore, we hoped to achieve primary closure. Our second major concern was that the method of fixation must be biomechanically sound without impeding our first goal of primary wound closure. In the setting of an ipsilateral TKA, standard antegrade IM nail fixation would not be possible. While we considered plate fixation, it is biomechanically less stable than an IM nail, and we had great concerns about wound complications. External fixation—uniplanar and mutliplanar (eg, Ilizarov)—was limited by issues of long-term fracture stability and risk of pin-site infection. Both methods appeared less desirable compared with IM nail fixation. Thus, we devised an innovative technique to implant an IM nail into the tibial canal.

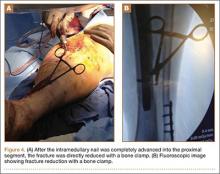

The operative procedure first entailed standard open fracture care comprising débridement of nonviable soft tissue from the traumatic anteromedial tibial wound, curettage of the fractured bone ends, and irrigation with pulse-jet lavage. Then, we turned to reduction and internal fixation of the bony injury. The large traumatic wound was not extended and was used as the primary surgical approach to permit introduction of the IM nail into the canal. Through the traumatic wound, we performed limited reaming of the proximal and distal fracture segments. Using a cannulated technique over guide wires, we reamed to 11 mm (Figure 2). The tourniquet was not used during the IM reaming. We determined the maximum nail length (approximately 22 cm) by measuring the distance from the fracture to the bone interface with the tibial component. We used a 10×200-mm femoral retrograde Synthes nail (Synthes, Inc, West Chester, Pennsylvania) for the procedure, although we considered an IM humerus nail. Through the traumatic wound, the nail was advanced in its entirety into the proximal tibial segment (Figure 3). The fracture was reduced anatomically and held with a bone tenaculum (Figures 4A, 4B). A medial cortical window proximal to the proximal extent of the IM nail was created through which the Synthes IM reduction tool (aluminum femoral finger) was advanced to impact the IM nail antegrade through the fracture site into the distal segment (Figure 5). After placement of the nail was complete, the excised fragment of bone was reinserted into the cortical window. The Synthes IM reduction tool was chosen for its diameter, length, and, most important, its relative flexibility. While maintaining reduction of the fracture, cross-locking of the nail was performed at the distal and proximal ends with perfect circle technique through stab incisions. Length, alignment, and rotation of the affected tibia were deemed symmetric to the contralateral side based on preoperative clinical measurements. Final fluoroscopic images showed appropriate alignment and proper implant placement.

Following open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture, the traumatic and surgical wounds were closed in a layered fashion. A subcutaneous drain and an incisional vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device were applied to the closed traumatic wound, and a second subcutaneous drain was placed at the site of the cortical window. The patient tolerated the procedure well without perioperative complications.

In the acute period after surgery, the patient’s neurologic and vascular status remained stable. Her muscular compartments remained soft and compressible on physical examination, and her pain was well controlled. The incisional VAC and the 2 Hemovac drains were removed within a few days of the operation. Intravenous cefazolin was continued through her hospital stay and she was transitioned to oral cephalexin at discharge as recommended by our infectious disease colleagues to complete a 10-day course of antibiotic therapy.

At the time of discharge—within 1 week of her initial injury—the patient’s wounds were dry and she was ambulatory with a walker. She was instructed to remain non-weight-bearing and to keep her wounds clean and dry with follow-up in 2 weeks. Over 6 to 8 weeks after surgery, the patient’s weight-bearing status was gradually advanced to full weight-bearing, and she achieved union of the fracture and uneventful healing of the traumatic wound (Figures 6A, 6B, 7).

Discussion

We have presented a case of an open distal-third tibial shaft fracture in a 66-year-old obese woman with an ipsilateral TKA. Open fracture of the tibial shaft is potentially limb-threatening because of the challenging management of the bone and soft-tissue injury. The presence of an ipsilateral TKA adds a degree of complexity. From a biomechanical standpoint, the lower interdigitation of cortical bone, coupled with weight-bearing of the lower extremity, subjects the tibia diaphysis to issues of rotation, length, and angular control.8 Due to the diaphyseal nature of the fracture, consisting of cortical bone with comparably lower vascularity and a small soft-tissue envelope, these fractures heal very slowly and often take as many as 6 to 9 months to achieve union.9,10 Furthermore, as was the case here, short oblique fractures of the tibial shaft often occur under bending stresses that also cause significant damage to the tibial soft-tissue envelope and periosteum, as indicated by the open wound. This disruption deprives the fracture and soft tissues of important vascular supply that is critical to healing and to avoiding infection and soft-tissue necrosis.11-13 The effects of treatment may magnify these biomechanical and biologic consequences. Ideal fixation serves to minimize potential complications by neutralizing the biomechanical forces to permit fracture healing while also limiting the amount of soft-tissue trauma and tension. Because the challenges associated with treatment of open tibial shaft fractures make it a limb-threatening injury in a patient with poor peripheral circulation, it is appropriate to consider primary amputation.14

If circumstances warrant an attempt at limb salvage, IM nailing with static interlocking screws would typically be the standard of care for treatment of an open fracture of the tibia shaft. This provides stable internal fixation that controls tibial alignment in 6° of freedom and neutralizes bending forces with less strain on the implant because of the IM position.15,16 In addition to superior neutralization of the biomechanical forces, IM nailing is also a minimally invasive approach that limits further trauma to the periosteum and soft-tissue envelope surrounding the fracture site. This optimizes biologic fracture healing and minimizes complications of malunion, infection, and nonunion.17-19 Moreover, by limiting further damage to the surrounding soft tissue, there is a diminished need for a plastic surgery procedure to reestablish soft-tissue integrity overlying the fracture site. This is particularly advantageous in patients with medical comorbidities that make skin grafts and muscle flaps less likely to succeed. For these reasons, IM nailing was our preferred method of fixation in our patient; however, the presence of an ipsilateral TKA made this standard treatment through an antegrade approach impossible.

Consequently, we considered other methods of fixation, including internal fixation with plate application or external fixation with a multiplanar construct, such as an Ilizarov frame. Some orthopedists consider plate application a superior technique for achieving fracture union because it results in interfragmentary compression, which promotes primary healing. Interestingly, some would argue that the absolute stability provided by the plate may be too rigid a construct to enable optimal fracture healing biology if compression is not achieved.20 However, to allow primary healing to complete fracture union, absolute stability with rigid and strong fixation must be provided. In the tibial shaft, with large bending forces and rotational moments, this is difficult to achieve with plate fixation alone.8 Furthermore, plate application often requires relatively extensive soft-tissue dissection and may impede biologic factors in healing of the bone and soft tissue, increasing the likelihood of infection.21 Finally, adequate plate fixation would significantly increase the soft-tissue volume at this location, further compromising the soft tissues and impeding our goal of primary wound closure.

A uniplanar or mutliplanar external fixator would be an appealing option for definitive fixation because of minimal additional soft-tissue damage that is created during its application. However, it is difficult to achieve adequate stability to encourage either primary, or more commonly, secondary healing in the adult or elderly population.22 An Ilizarov frame is a multiplanar external construct, which allows reconstructive applications because of multiple points of fixation in bone.23 However, the multiple fixation points result in burdensome size of the implant for the patient and requires patient compliance to minimize risk of pin-site infection, which is magnified in a patient with multiple medical comorbid conditions. Furthermore, when comparing treatment options that aim to minimize additional soft-tissue trauma at the site of injury, there is little evidence to show a lower risk of infection at the open fracture site compared with IM nailing.24,25 Thus, in our patient, customary treatment of an open tibial shaft fracture using antegrade IM nailing was not possible, while plate application and external fixation, though potential treatment options, would be relatively contraindicated due to a higher likelihood of failure.

Consequently, primary amputation may be the most appropriate treatment option in a patient with multiple comorbid medical conditions, including peripheral vascular disease. Primary amputation prevents morbidity and mortality associated with complications related to the aforementioned treatment options, as well as limiting risks associated with multiple reoperations.14,25 Studies illustrate that patient functional outcomes after primary amputation are equal to and, in some cases, superior to those patients undergoing limb salvage procedures for open tibial shaft fractures.26-28

Despite the appropriateness of primary amputation in this case, the patient requested limb salvage. Therefore, other innovative treatment options were explored to achieve our goals of primary wound closure and stable internal fixation. Previous case reports have examined retrograde IM nailing as a means of rigidly fixing tibial shaft fractures in the setting of poor soft tissues or ipsilateral knee arthroplasty.29-31 However, the retrograde approach to IM nailing requires passage of reamers through the subtalar and ankle joints, leading to associated arthritis in these joints or, more commonly, rigidity because the final nail position often crosses these joints in addition to the fracture site. Therefore, a novel approach for IM nailing was performed using the large open-fracture wound. Through the traumatic wound, open-fracture débridement was first performed, followed by placement of a nail into the medullary canal with little additional disruption of the surrounding periosteum or soft tissue.

Possible complications of this novel method for IM nail passage warrant discussion. First, potentially unfavorable aspects associated with IM reaming include impairment of endosteal blood circulation in the subacute postoperative period.32-34 If the patient develops complications, such as deep infection, nonunion, hardware failure, or periprosthetic fracture, treatment options that require removal of the nail would be very difficult to execute because this nail was passed “intragrade,” or through the fracture site, not from the knee or the calcaneus. However, unique to this case of intragrade nailing, complications associated with the proximal cortical window may occur. In particular, unintended cortical fracture may happen during impaction of the nail into the distal segment of the fracture after reduction. However, this complication may be avoided with the use of a 1-cm wide and 2-cm long window and the use of the malleable aluminum femoral finger (Synthes). Furthermore, use of a femoral nail is recommended because the Herzog curve of a tibial nail cannot be inserted in the proximal tibial segment using an “intragrade” nailing technique. However, fracture may occur intraoperatively or during rehabilitation after surgery because the cortical window creates a region of high stress distal to the tibial arthroplasty component. Likewise, the area of bone between the proximal extent of the IM nail and tibial component of the TKA represents an area of high stress susceptible to periprosthetic fracture.

Conclusion

We have presented a case of a high-energy open distal tibial diaphyseal fracture in a 66-year-old woman with medical comorbidities and treatment complicated by the presence of an ipsilateral TKA. Intramedullary nailing has become the standard of care for open fractures of the tibial diaphysis because of the high rate of union with little additional soft-tissue damage at the fracture site. Despite these advantages, the ipsilateral TKA complicated the placement of an antegrade tibial nail. An alternative treatment, such as an external fixation using an Ilizarov frame, would present equally challenging treatment aspects, including patient compliance, with little proven benefit over an IM nail. Application of a plate would be less desirable because of increased risk of infection at the fracture site, soft-tissue and periosteum disruption, and muscle necrosis compared with other treatment options. Primary amputation was an appropriate consideration for this patient given her comorbid medical circumstances, but the patient refused this treatment option. Therefore, we created a novel approach to place an IM nail, using the traumatic wound to achieve access to the medullary canal proximally and distally.

Fracture of the tibial shaft below an ipsilateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is an infrequently occurring injury pattern that presents a unique treatment scenario. The high predilection for open wounds associated with these diaphyseal fractures further complicates the treatment algorithm.1,2 The standard principles of treatment for open tibial shaft fractures entail open fracture débridement followed by adequate fracture reduction and stable skeletal fixation in a manner that limits adverse complications of this injury, which include nonunion, malunion, infection, soft-tissue compromise, and reoperation.3,4

Antegrade intramedullary (IM) tibial nailing has become standard treatment for tibial shaft fractures.5-7 This minimally invasive method of fixation limits damage to the soft-tissue envelope, provides superior neutralization of the mechanical forces to provide a template for biologic fracture healing, and allows the best options for revision procedures in the event of inadequate healing. This case report examines treatment options for an open tibial shaft fracture of an ipsilateral TKA, complicating the standard treatment of antegrade tibial nailing. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report