User login

Satisfaction With Department of Veterans Affairs Prosthetics and Support Services as Reported by Women and Men Veterans

Satisfaction With Department of Veterans Affairs Prosthetics and Support Services as Reported by Women and Men Veterans

Limb loss is a significant and growing concern in the United States. Nearly 2 million Americans are living with limb loss, and up to 185,000 people undergo amputations annually.1-4 Of these patients, about 35% are women.5 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides about 10% of US amputations.6-8 Between 2015 and 2019, the number of prosthetic devices provided to female veterans increased from 3.3 million to 4.6 million.5,9,10

Previous research identified disparities in prosthetic care between men and women, both within and outside the VHA. These disparities include slower prosthesis prescription and receipt among women, in addition to differences in self-reported mobility, satisfaction, rates of prosthesis rejection, and challenges related to prosthesis appearance and fit.5,10,11 Recent studies suggest women tend to have worse outcomes following amputation, and are underrepresented in amputation research.12,13 However, these disparities are poorly described in a large, national sample. Because women represent a growing portion of patients with limb loss in the VHA, understanding their needs is critical.14

The Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, MD Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020 was enacted, in part, to improve the care provided to women veterans.15 The law required the VHA to conduct a survey of ≥ 50,000 veterans to assess the satisfaction of women veterans with prostheses provided by the VHA. To comply with this legislation and understand how women veterans rate their prostheses and related care in the VHA, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Center for Collaborative Evaluation (VACE) conducted a large national survey of veterans with limb loss that oversampled women veterans. This article describes the survey results, including characteristics of female veterans with limb loss receiving care from the VHA, assesses their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care, and highlights where their responses differ from those of male veterans.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, mixedmode survey of eligible amputees in the VHA Support Service Capital Assets Amputee Data Cube. We identified a cohort of veterans with any major amputation (above the ankle or wrist) or partial hand or foot amputation who received VHA care between October 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020. The final cohort yielded 46,646 potentially eligible veterans. Thirty-three had invalid contact information, leaving 46,613 veterans who were asked to participate, including 1356 women.

Survey

We created a survey instrument de novo that included questions from validated instruments, including the Trinity Amputation Prosthesis and Experience Scales to assess prosthetic device satisfaction, the Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire to assess quality of life (QOL) satisfaction, and the Orthotics Prosthetics Users Survey to assess prosthesis-related care satisfaction. 16-18 Additional questions were incorporated from a survey of veterans with upper limb amputation to assess the importance of cosmetic considerations related to the prosthesis and comfort with prosthesis use in intimate relationships.19 Questions were also included to assess amputation type, year of amputation, if a prosthesis was currently used, reasons for ceasing use of a prosthesis, reasons for never using a prosthesis, the types of prostheses used, intensity of prosthesis use, satisfaction with time required to receive a prosthetic limb, and if the prosthesis reflected the veteran’s selfidentified gender. Veterans were asked to answer questions based on their most recent amputation.

We tested the survey using cognitive interviews with 6 veterans to refine the survey and better understand how veterans interpreted the questions. Pilot testers completed the survey and participated in individual interviews with experienced interviewers (CL and RRK) to describe how they selected their responses.20 This feedback was used to refine the survey. The online survey was programmed using Qualtrics Software and manually translated into Spanish.

Given the multimodal design, surveys were distributed by email, text message, and US Postal Service (USPS). Surveys were emailed to all veterans for whom a valid email address was available. If emails were undeliverable, veterans were contacted via text message or the USPS. Surveys were distributed by text message to all veterans without an email address but with a cellphone number. We were unable to consistently identify invalid numbers among all text message recipients. Invitations with a survey URL and QR code were sent via USPS to veterans who had no valid email address or cellphone number. Targeted efforts were made to increase the response rate for women. A random sample of 200 women who had not completed the survey 2 weeks prior to the closing date (15% of women in sample) was selected to receive personal phone calls. Another random sample of 400 women was selected to receive personalized outreach emails. The survey data were confidential, and responses could not be traced to identifying information.

Data Analyses

We conducted a descriptive analysis, including percentages and means for responses to variables focused on describing amputation characteristics, prosthesis characteristics, and QOL. All data, including missing values, were used to document the percentage of respondents for each question. Removing missing data from the denominator when calculating percentages could introduce bias to the analysis because we cannot be certain data are missing at random. Missing variables were removed to avoid underinflation of mean scores.

We compared responses across 2 groups: individuals who self-identified as men and individuals who self-identified as women. For each question, we assessed whether each of these groups differed significantly from the remaining sample. For example, we examined whether the percentage of men who answered affirmatively to a question was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as male, and whether the percentage of women who answered affirmatively was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as female. We utilized x2 tests to determine significant differences for percentage calculations and t tests to determine significant differences in means across gender.

Since conducting multiple comparisons within a dataset may result in inflating statistical significance (type 1 errors), we used a more conservative estimate of statistical significance (α = 0.01) and high significance (α = 0.001). This study was deemed quality improvement by the VHA Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Services (12RPS) and acknowledged by the VA Research Office at Eastern Colorado Health Care System and was not subject to institutional review board review.

Results

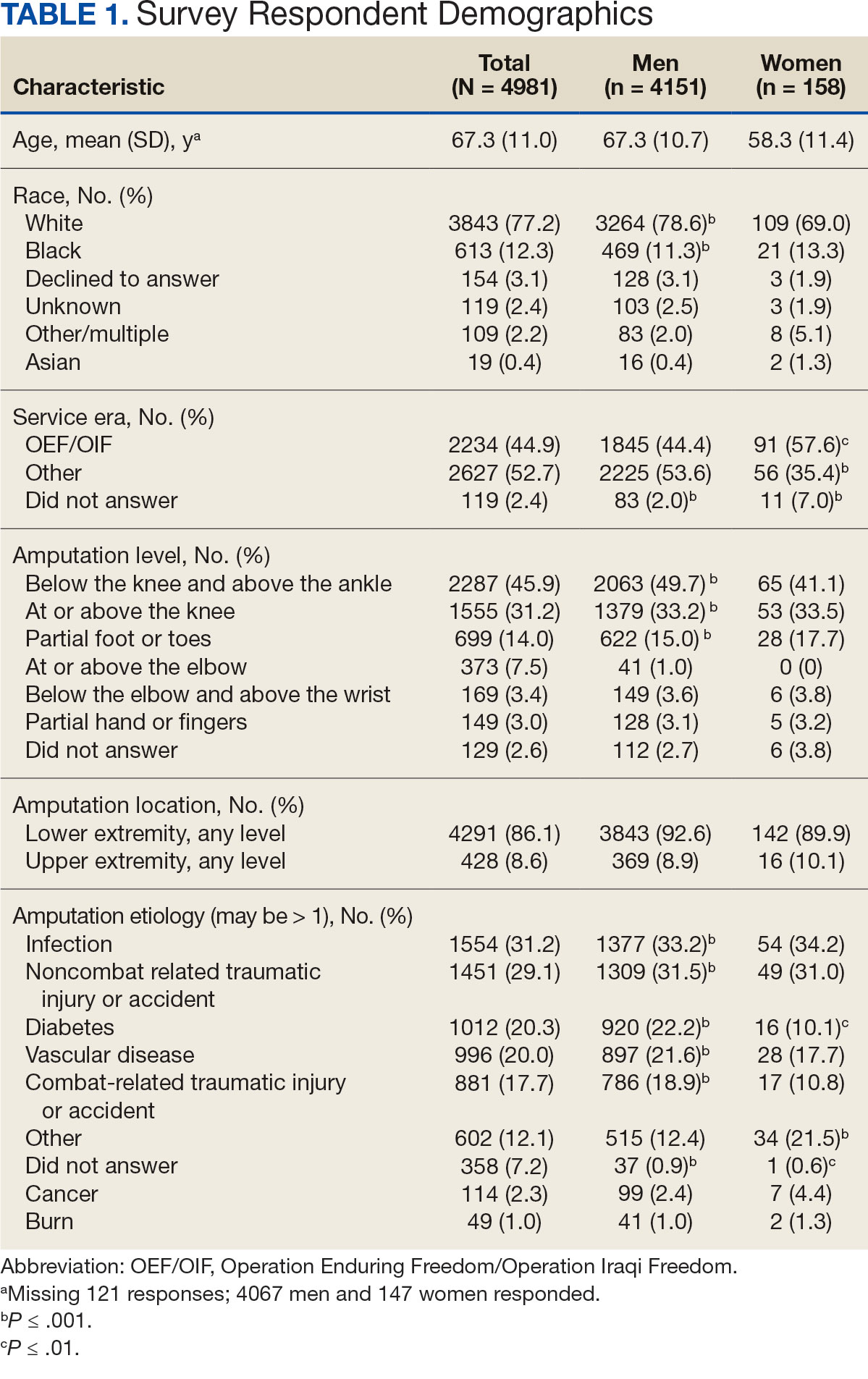

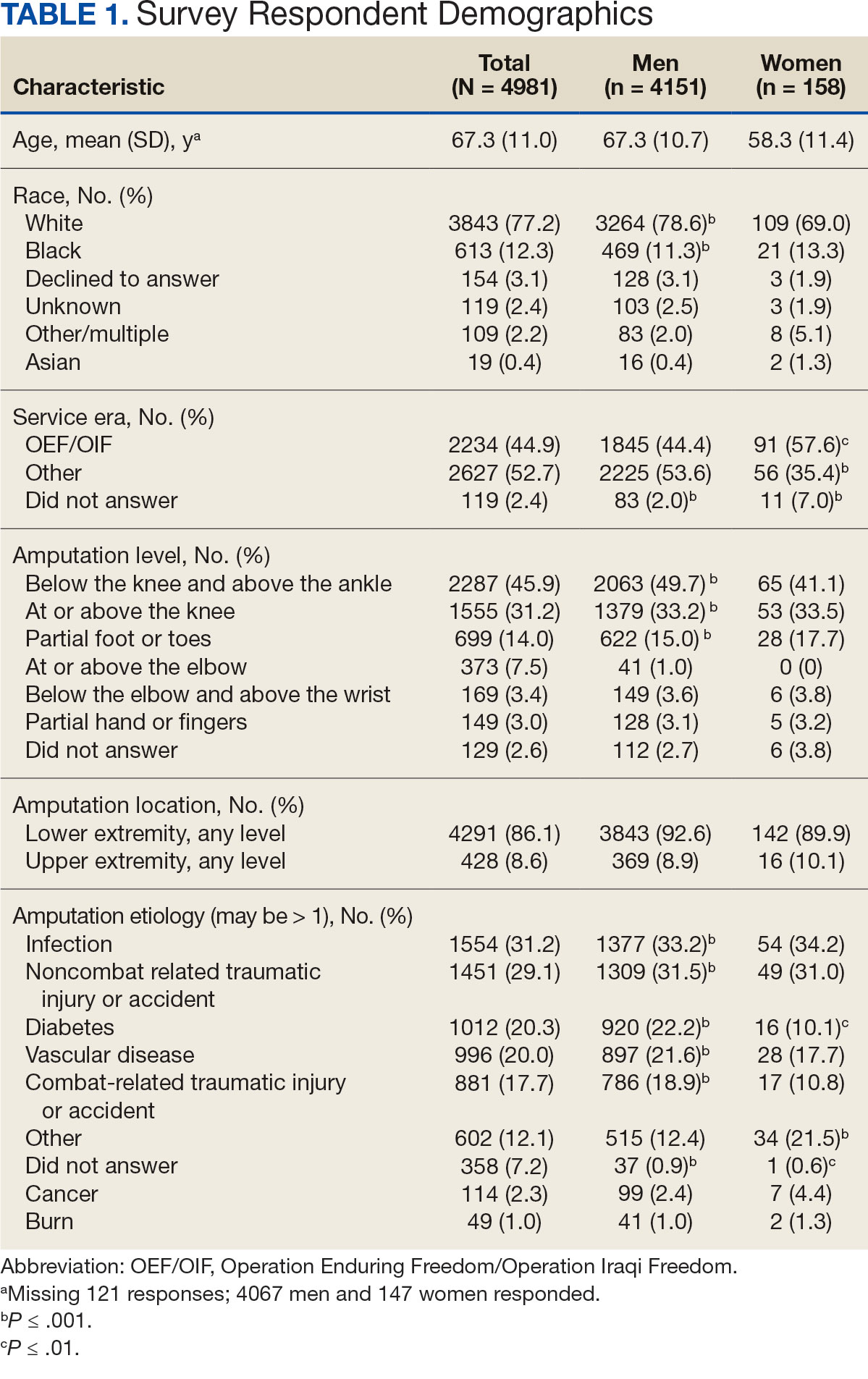

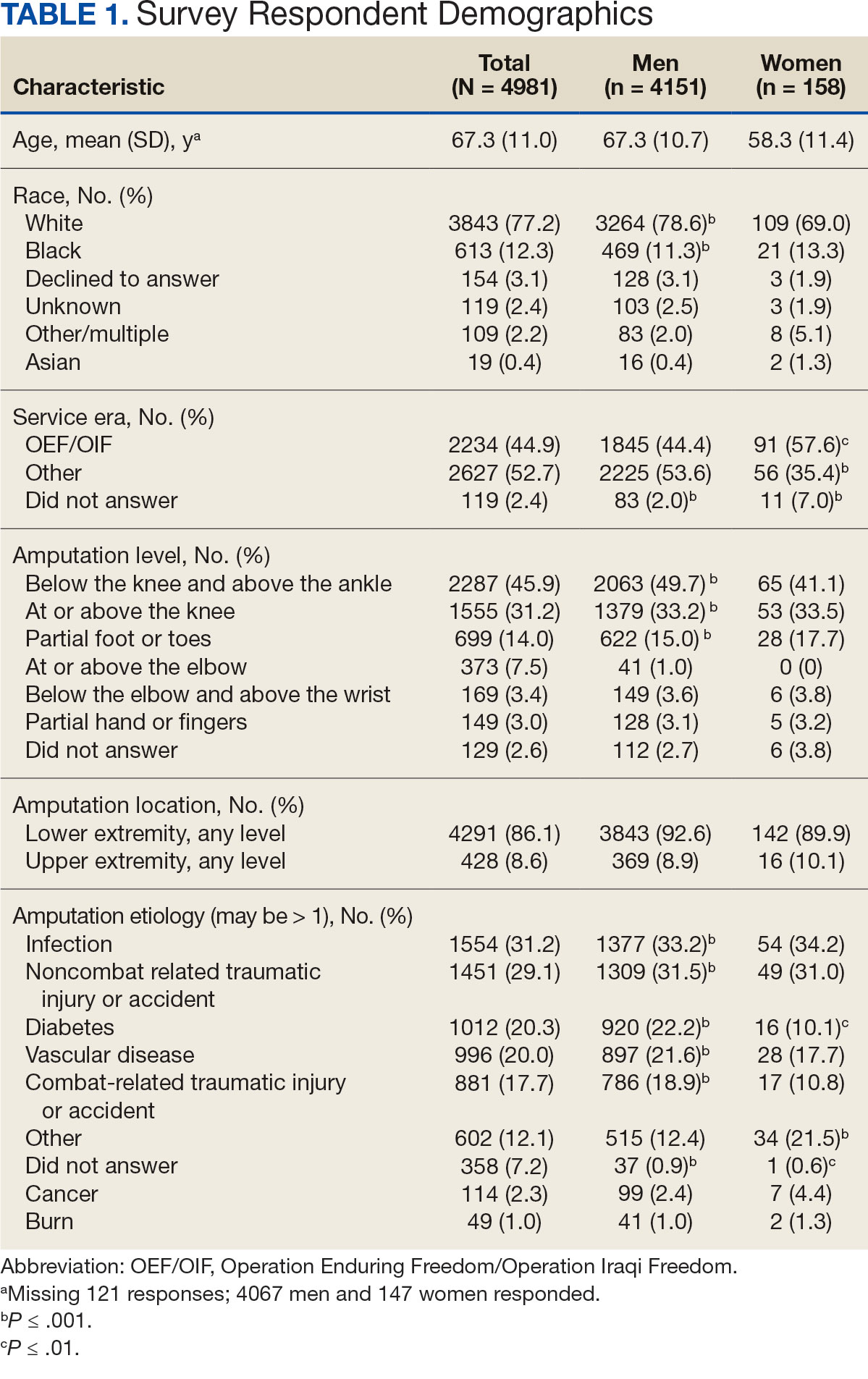

Surveys were distributed to 46,613 veterans and were completed by 4981 respondents for a 10.7% overall response rate. Survey respondents were generally similar to the eligible population invited to participate, but the proportion of women who completed the survey was higher than the proportion of women eligible to participate (2.0% of eligible population vs 16.7% of respondents), likely due to specific efforts to target women. Survey respondents were slightly younger than the general population (67.3 years vs 68.7 years), less likely to be male (97.1% vs 83.3%), showed similar representation of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans (4.4% vs 4.1%), and were less likely to have diabetes (58.0% vs 52.7% had diabetes) (Table 1).

The mean age of male respondents was 67.3 years, while the mean age of female respondents was 58.3 years. The majority of respondents were male (83.3%) and White (77.2%). Female respondents were less likely to have diabetes (35.4% of women vs 53.5% of men) and less likely to report that their most recent amputation resulted from diabetes (10.1% of women vs 22.2% of men). Women respondents were more likely to report an amputation due to other causes, such as adverse results of surgery, neurologic disease, suicide attempt, blood clots, tumors, rheumatoid arthritis, and revisions of previous amputations. Most women respondents did not serve during the OEF or OIF eras. The most common amputation site for women respondents was lower limb, either below the knee and above the ankle or above the knee.

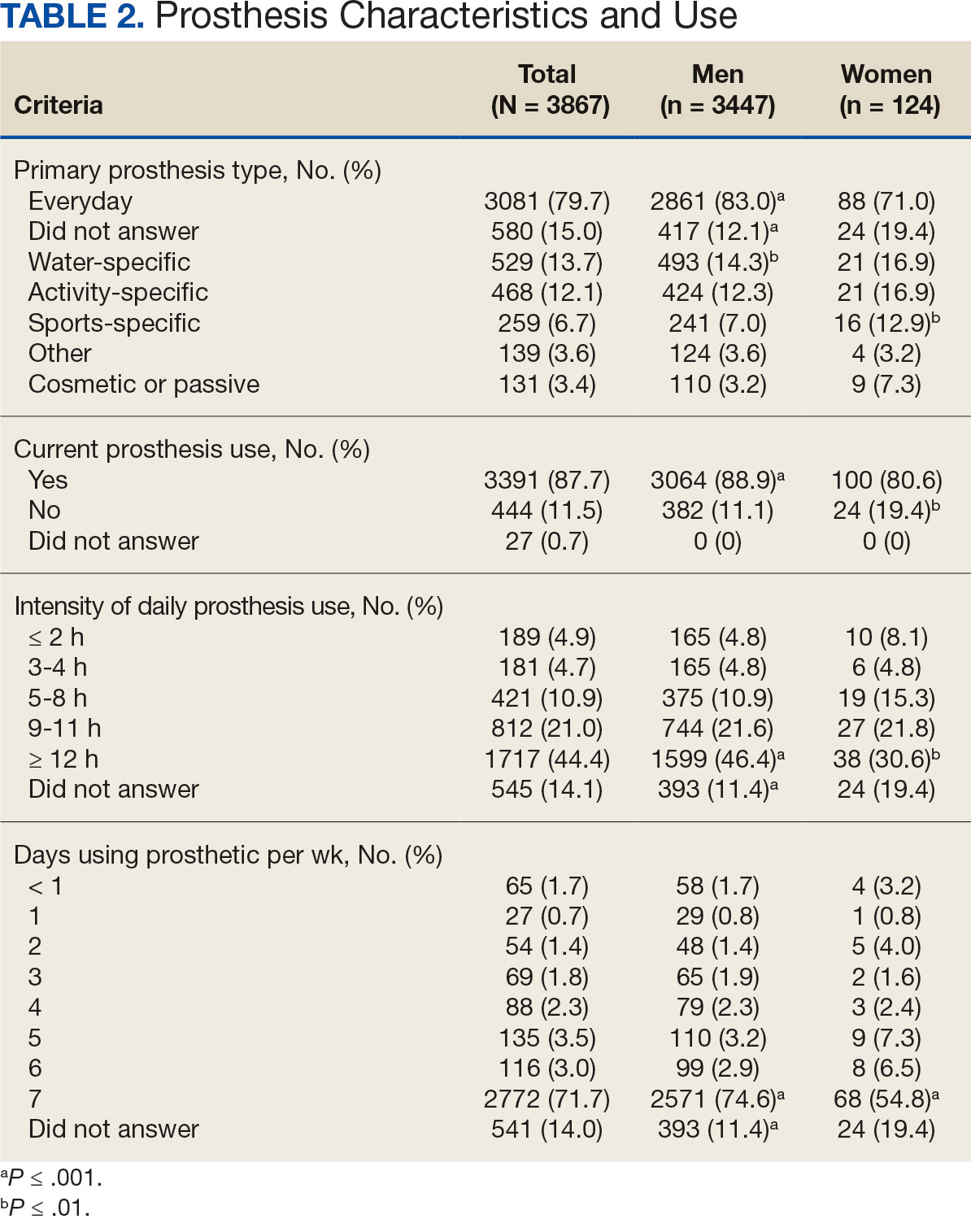

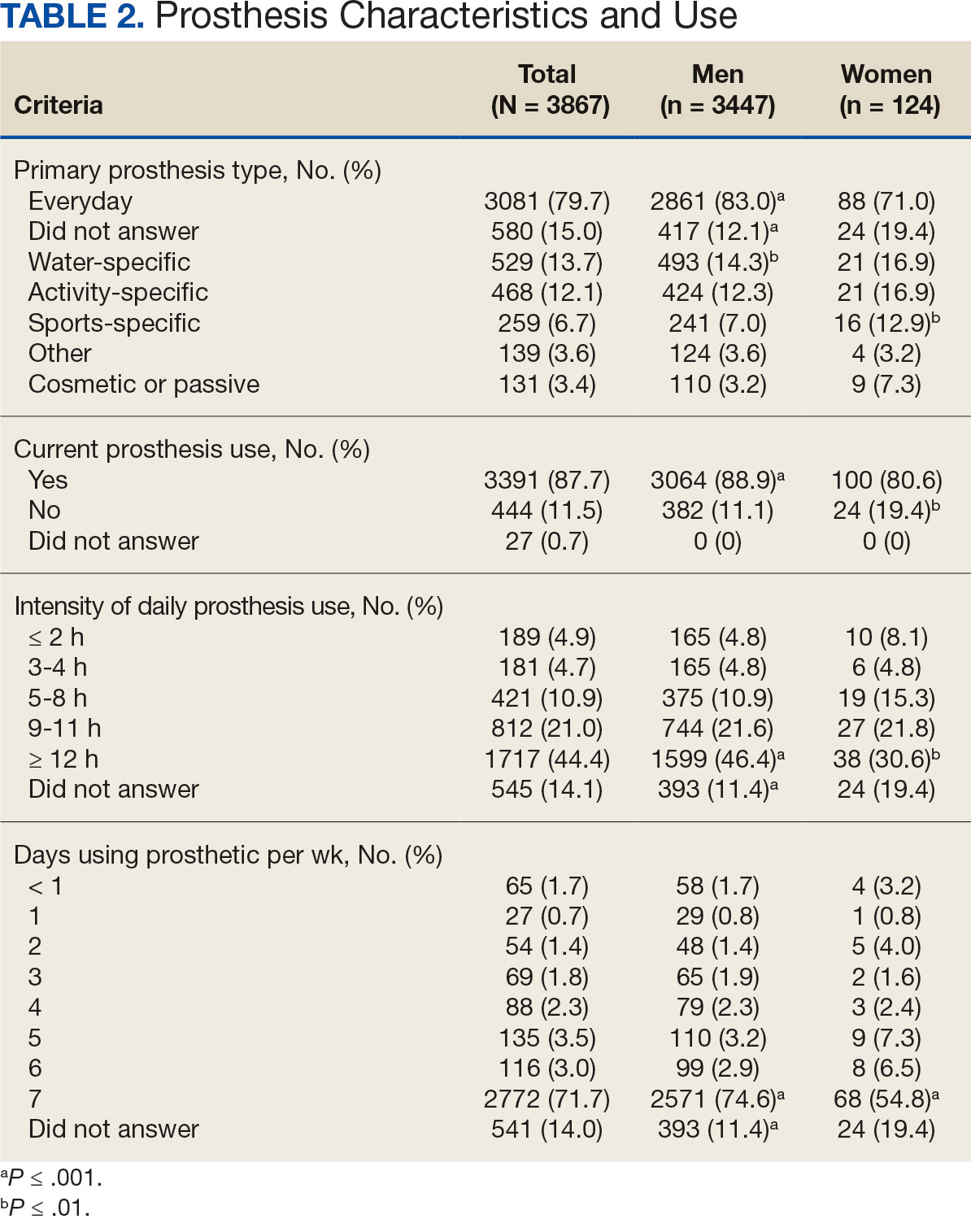

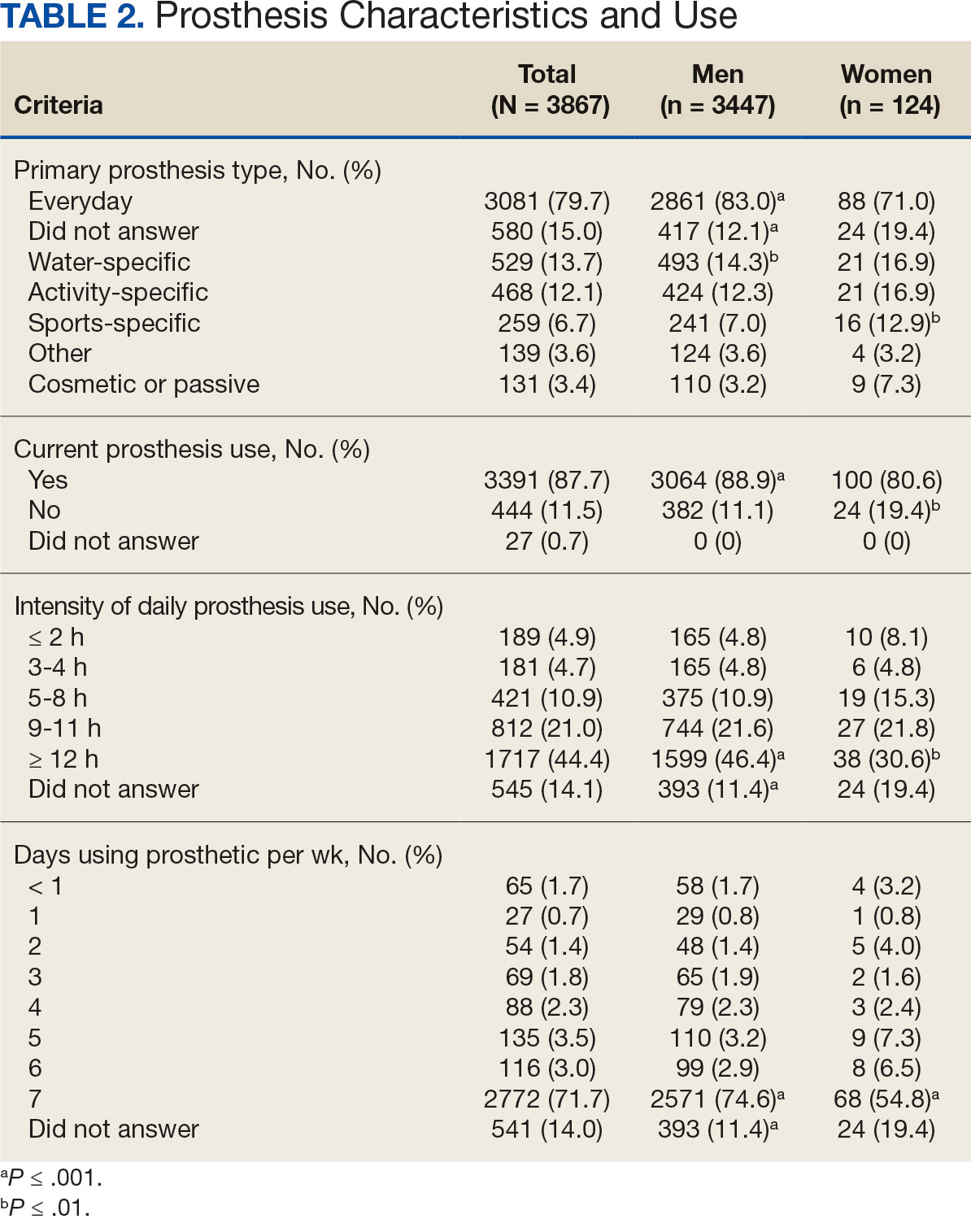

Most participants use an everyday prosthesis, but women were more likely to report using a sports-specific prosthesis (Table 2). Overall, most respondents report using a prosthesis (87.7%); however, women were more likely to report not using a prosthesis (19.4% of women vs 11.1% of men; P ≤ .01). Additionally, a lower proportion of women report using a prosthesis for < 12 hours per day (30.6% of women vs 46.4% of men; P ≤ .01) or using a prosthesis every day (54.8% of women vs 74.6% of men; P ≤ .001).

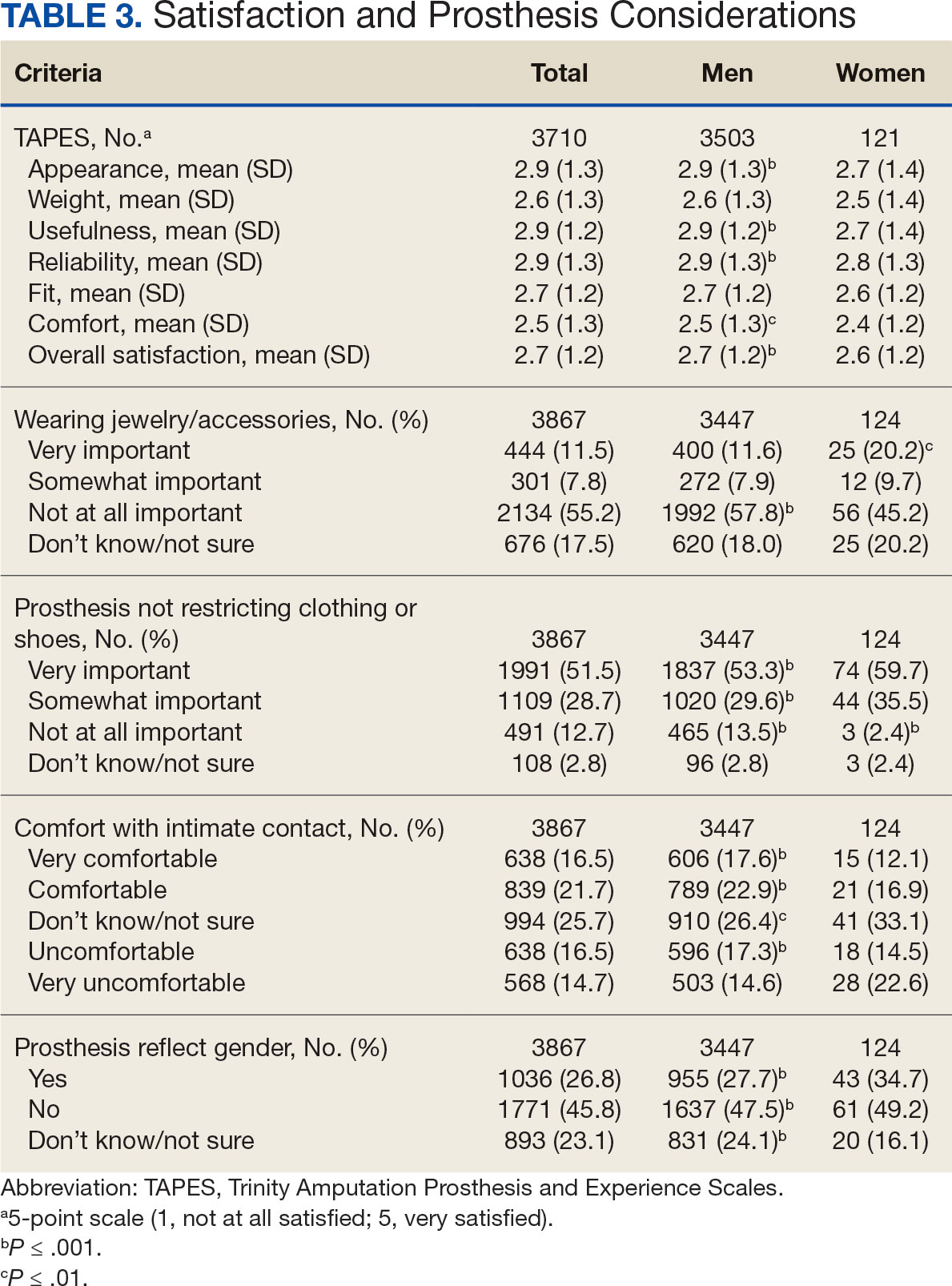

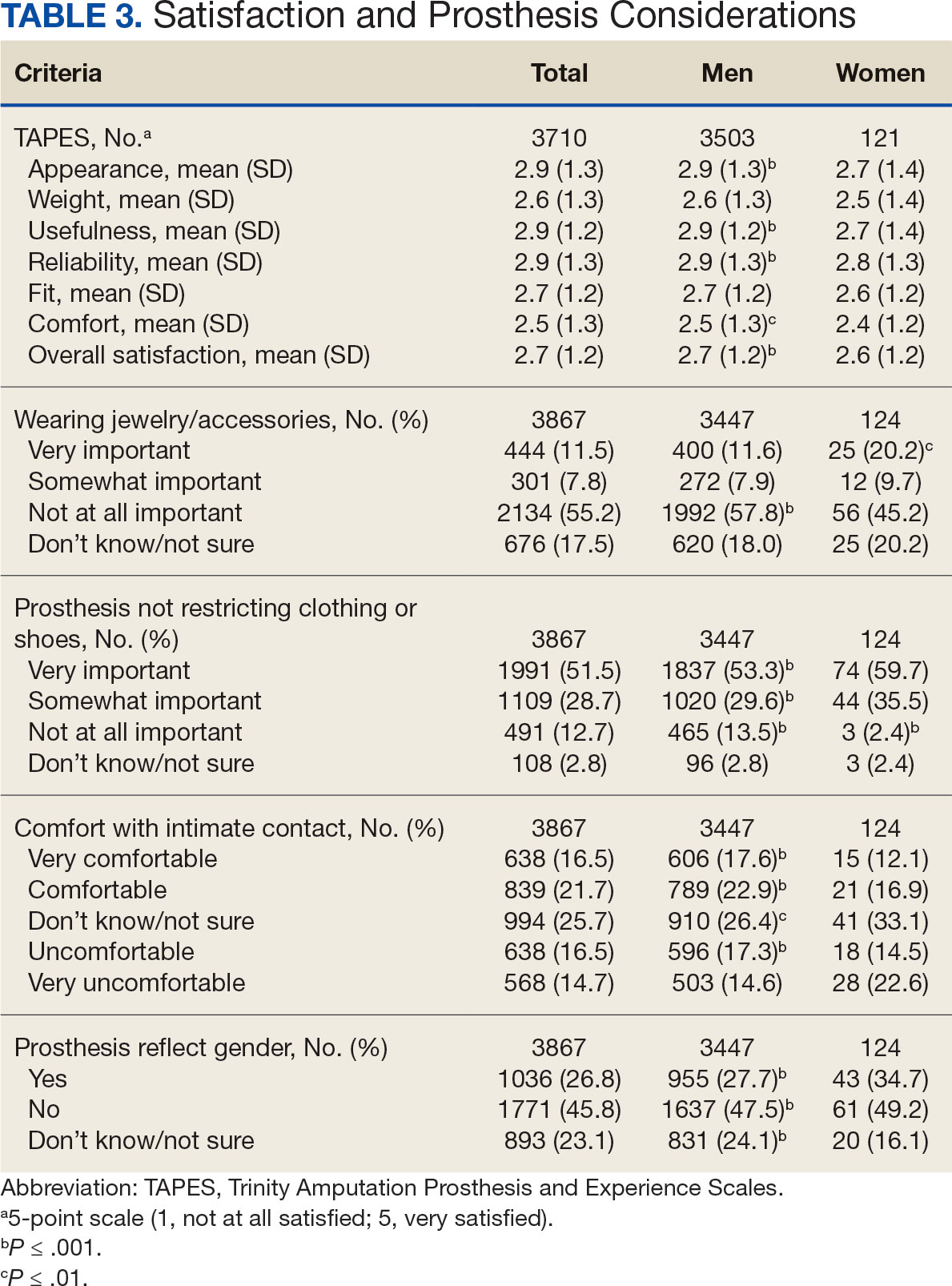

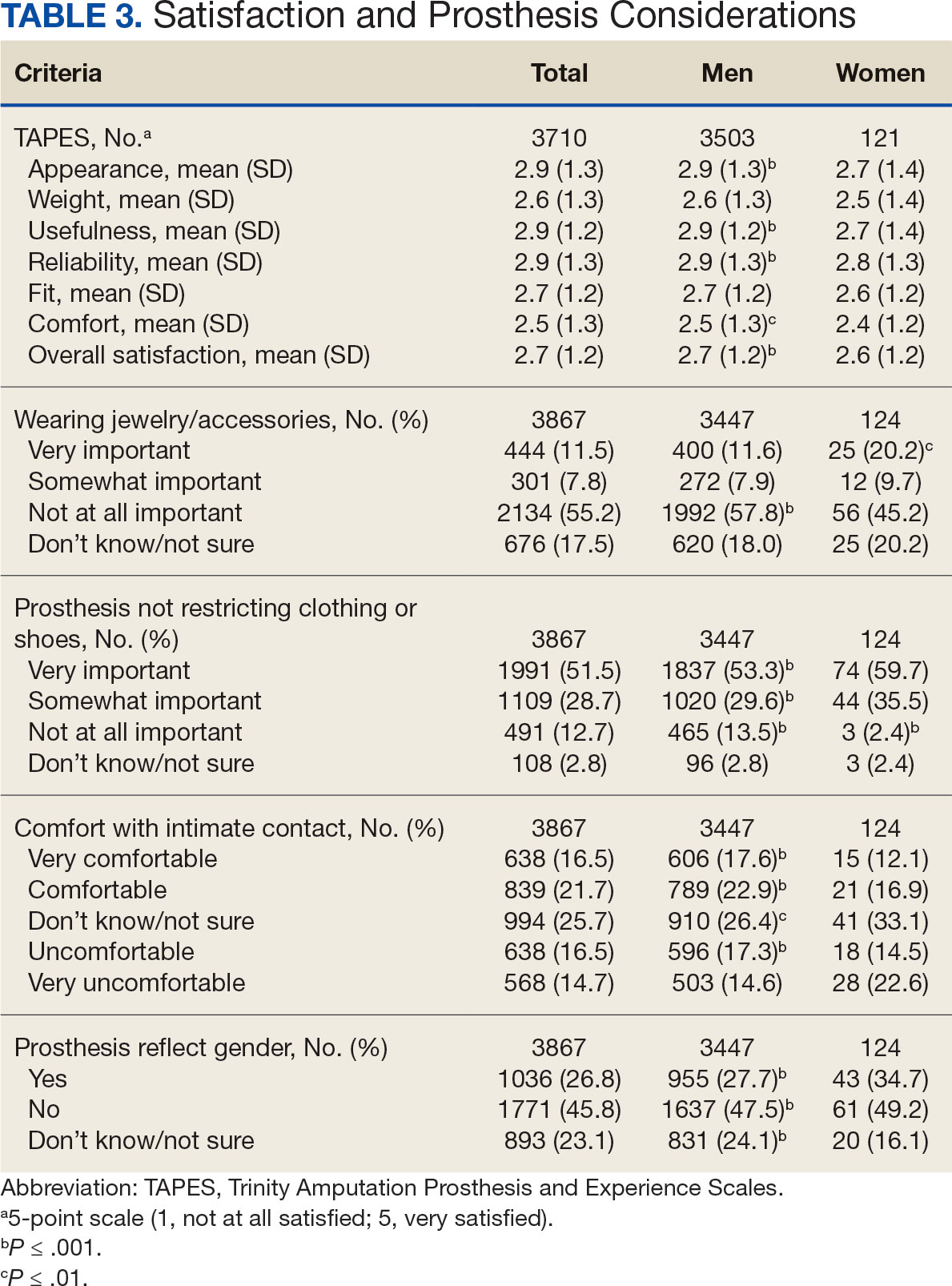

In the overall sample, the mean satisfaction score with a prosthesis was 2.7 on a 5-point scale, and women had slightly lower overall satisfaction scores (2.6 for women vs 2.7 for men; P ≤ .001) (Table 3). Women also had lower satisfaction scores related to appearance, usefulness, reliability, and comfort. Women were more likely to indicate that it was very important to be able to wear jewelry and accessories (20.2% of women vs 11.6% of men; P ≤ .01), while men were less likely to indicate that it was somewhat or very important that the prosthesis not restrict clothing or shoes (95.2% of women vs 82.9% of men; P ≤ .001). Men were more likely than women to report being comfortable or very comfortable using their prosthesis in intimate contact: 40.5% vs 29.0%, respectively (P ≤ .001).

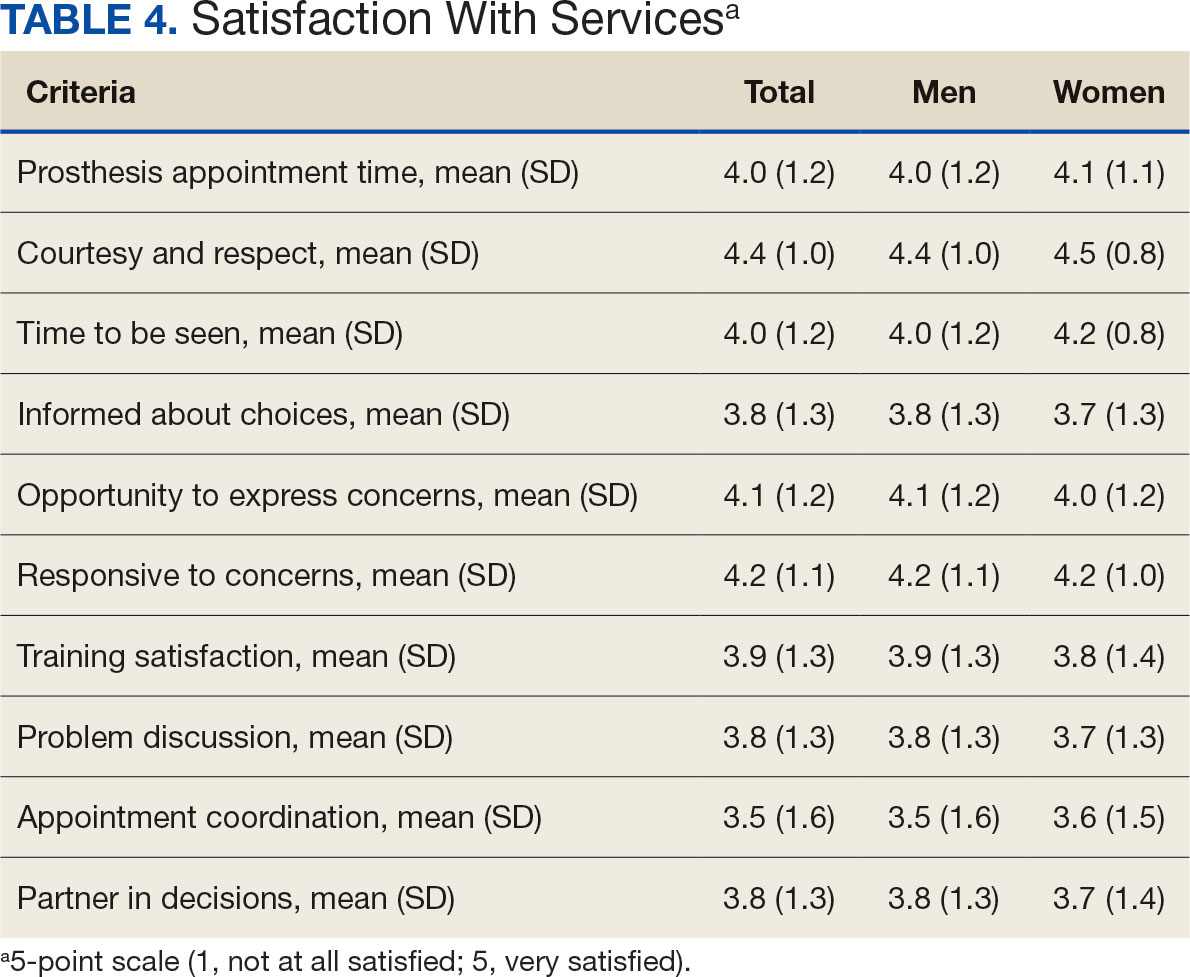

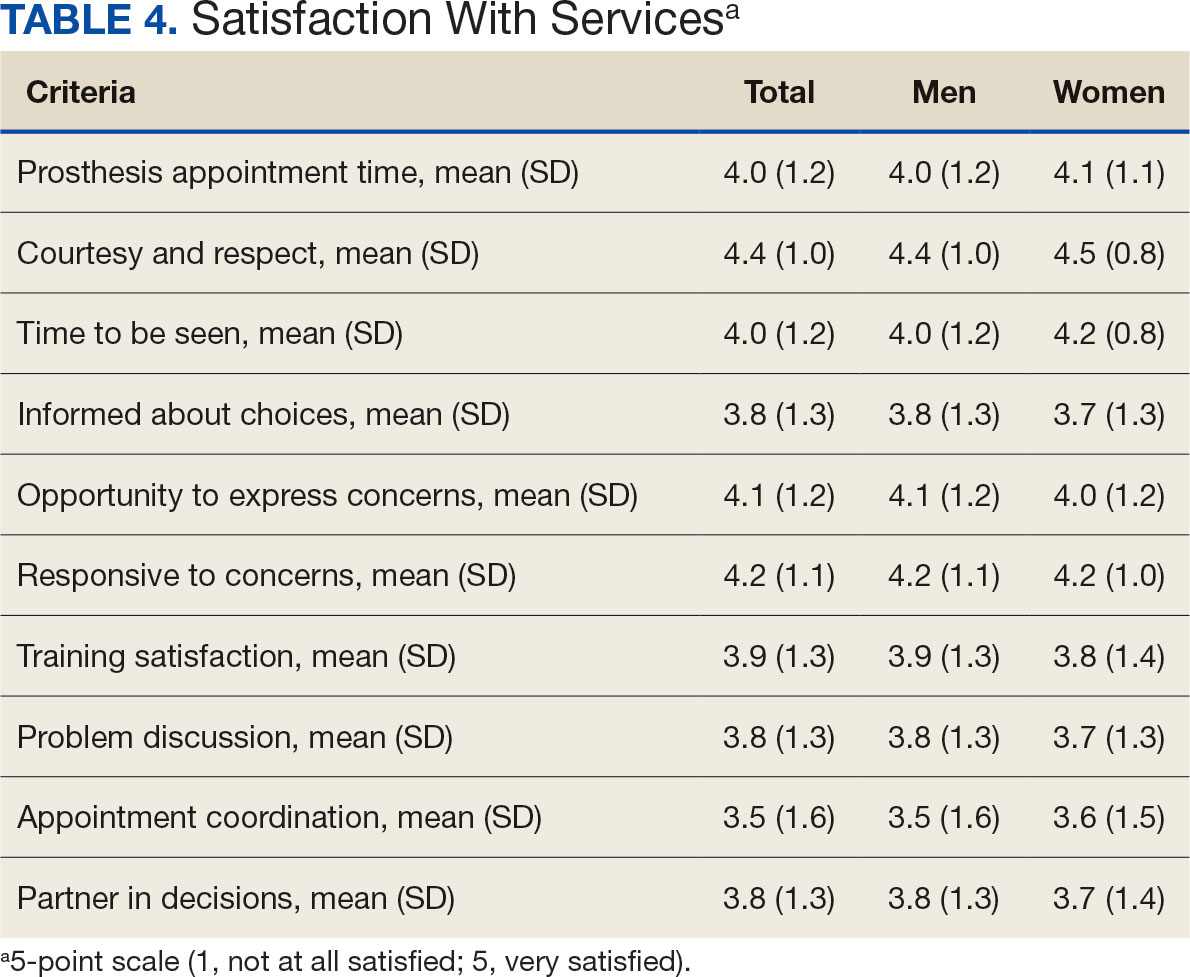

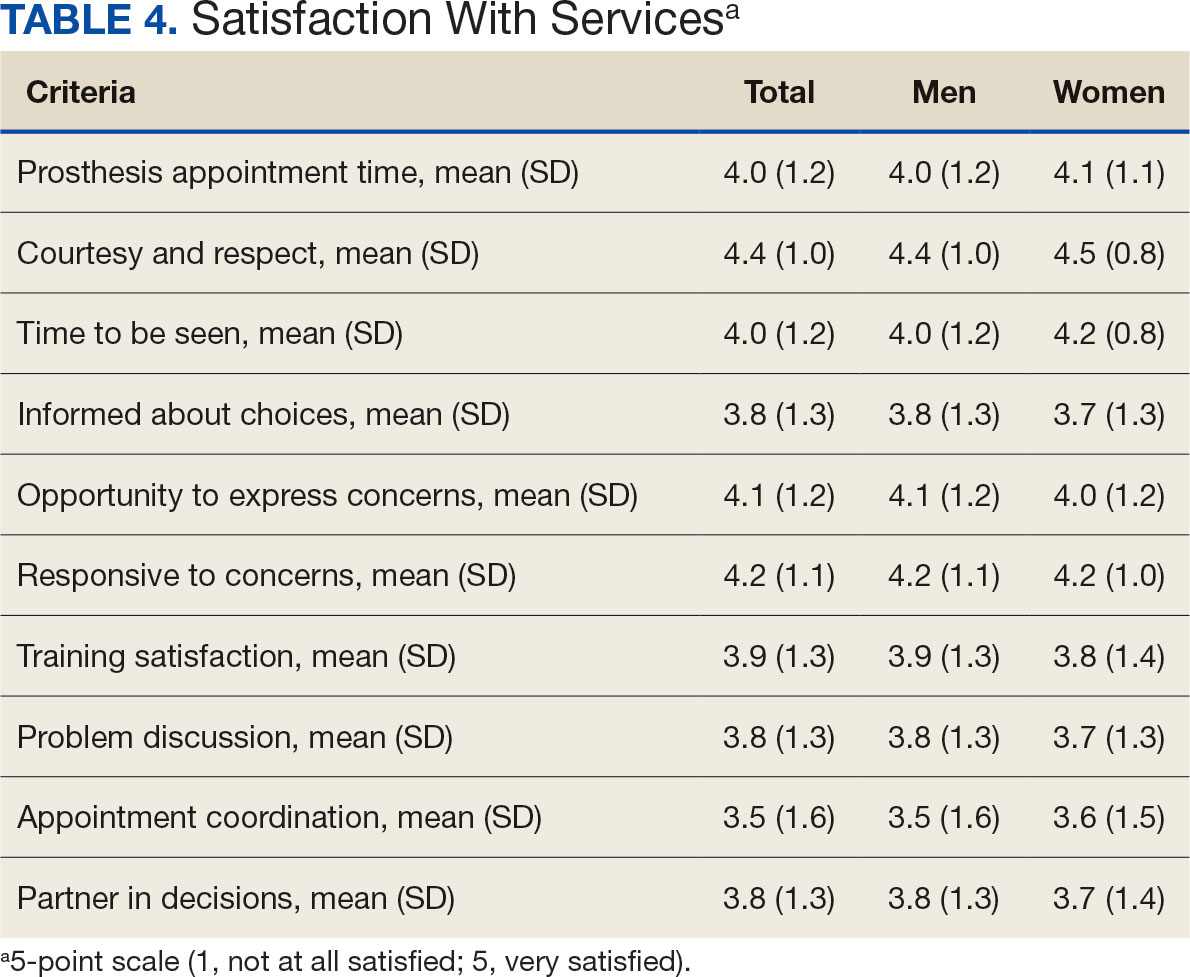

Overall, participants reported high satisfaction with appointment times, wait times, courteous treatment, opportunities to express concerns, and staff responsiveness. Men were slightly more likely than women to be satisfied with training (P ≤ 0.001) and problem discussion (P ≤ 0.01) (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences in satisfaction or QOL ratings between women and men. The overall sample rated both QOL and satisfaction with QOL 6.7 on a 10-point scale.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to characterize the experience of veterans with limb loss receiving care in the VHA and assess their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care. We received responses from nearly 5000 veterans, 158 of whom were women. Women veteran respondents were slightly younger and less likely to have an amputation due to diabetes. We did not observe significant differences in amputation level between men and women but women were less likely to use a prosthesis, reported lower intensity of prosthesis use, and were less satisfied with certain aspects of their prostheses. Women may also be less satisfied with prosthesis training and problem discussion. However, we found no differences in QOL ratings between men and women.

Findings indicating women were more likely to report not using a prosthesis and that a lower proportion of women report using a prosthesis for > 12 hours a day or every day are consistent with previous research. 21,22 Interestingly, women were more likely to report using a sports-specific prosthesis. This is notable because prior research suggests that individuals with amputations may avoid participating in sports and exercise, and a lack of access to sports-specific prostheses may inhibit physical activity.23,24 Women in this sample were slightly less satisfied with their prostheses overall and reported lower satisfaction scores regarding appearance, usefulness, reliability, and comfort, consistent with previous findings.25

A lower percentage of women in this sample reported being comfortable or very comfortable using their prosthesis during intimate contact. Previous research on prosthesis satisfaction suggests individuals who rate prosthesis satisfaction lower also report lower body image across genders. 26 While women in this sample did not rate their prosthesis satisfaction lower than men, they did report lower intensity of prosthesis use, suggesting potential issues with their prostheses this survey did not evaluate. Women indicated the importance of prostheses not restricting jewelry, accessories, clothing, or shoes. These results have significant clinical and social implications. A recent qualitative study emphasizes that women veterans feel prostheses are primarily designed for men and may not work well with their physiological needs.9 Research focused on limbs better suited to women’s bodies could result in better fitting sockets, lightweight limbs, or less bulky designs. Additional research has also explored the difficulties in accommodating a range of footwear for patients with lower limb amputation. One study found that varying footwear heights affect the function of adjustable prosthetic feet in ways that may not be optimal.27

Ratings of satisfaction with prosthesisrelated services between men and women in this sample are consistent with a recent study showing that women veterans do not have significant differences in satisfaction with prosthesis-related services.28 However, this study focused specifically on lower limb amputations, while the respondents of this study include those with both upper and lower limb amputations. Importantly, our findings that women are less likely to be satisfied with prosthesis training and problem discussions support recent qualitative findings in which women expressed a desire to work with prosthetists who listen to them, take their concerns seriously, and seek solutions that fit their needs. We did not observe a difference in QOL ratings between men and women in the sample despite lower satisfaction among women with some elements of prosthesis-related services. Previous research suggests many factors impact QOL after amputation, most notably time since amputation.16,29

Limitations

This survey was deployed in a short timeline that did not allow for careful sample selection or implementing strategies to increase response rate. Additionally, the study was conducted among veterans receiving care in the VHA, and findings may not be generalizable to limb loss in other settings. Finally, the discrepancy in number of respondents who identified as men vs women made it difficult to compare differences between the 2 groups.

Conclusions

This is the largest sample of survey respondents of veterans with limb loss to date. While the findings suggest veterans are generally satisfied with prosthetic-related services overall, they also highlight several areas for improvement with services or prostheses. Given that most veterans with limb loss are men, there is a significant discrepancy between the number of women and men respondents. Additional studies with more comparable numbers of men and women have found similar ratings of satisfaction with prostheses and services.28 Further research specifically focused on improving the experiences of women should focus on better characterizing their experiences and identifying how they differ from those of male veterans. For example, understanding how to engage female veterans with limb loss in prosthesis training and problem discussions may improve their experience with their care teams and improve their use of prostheses. Understanding experiences and needs that are specific to women could lead to the development of processes, resources, or devices that are tailored to the unique requirements of women with limb loss.

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(3):422-429. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.005

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ. Limb amputation and limb deficiency: epidemiology and recent trends in the united states. South Med J. 2002;95(8):875-883. doi:10.1097/00007611-200208000-00018

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, Shore AD. Reamputation, mortality, and health care costs among persons with dysvascular lower-limb amputations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(3):480-486. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.06.072

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ambulatory and inpatient procedures in the United States. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/98facts/ambulat.htm

- Ljung J, Iacangelo A. Identifying and acknowledging a sex gap in lower-limb prosthetics. JPO. 2024;36(1):e18-e24. doi:10.1097/JPO.0000000000000470

- Feinglass J, Brown JL, LoSasso A, et al. Rates of lower-extremity amputation and arterial reconstruction in the united states, 1979 to 1996. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(8):1222- 1227. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.8.1222

- Mayfield JA, Reiber GE, Maynard C, Czerniecki JM, Caps MT, Sangeorzan BJ. Trends in lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration, 1989-1998. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37(1):23-30.

- Feinglass J, Pearce WH, Martin GJ, et al. Postoperative and late survival outcomes after major amputation: findings from the department of veterans affairs national surgical quality improvement program. Surgery. 2001;130(1):21-29. doi:10.1067/msy.2001.115359

- Lehavot K, Young JP, Thomas RM, et al. Voices of women veterans with lower limb prostheses: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(3):799-805. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07572-8

- US Government Accountability Office. COVID-19: Opportunities to improve federal response. GAO-21-60. Published November 12, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-60

- Littman AJ, Peterson AC, Korpak A, et al. Differences in prosthetic prescription between men and women veterans after transtibial or transfemoral lowerextremity amputation: a longitudinal cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;104(8)1274-1281. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2023.02.011

- Cimino SR, Vijayakumar A, MacKay C, Mayo AL, Hitzig SL, Guilcher SJT. Sex and gender differences in quality of life and related domains for individuals with adult acquired lower-limb amputation: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022 Oct 23;44(22):6899-6925. doi:10.1080/09638288.2021.1974106

- DadeMatthews OO, Roper JA, Vazquez A, Shannon DM, Sefton JM. Prosthetic device and service satisfaction, quality of life, and functional performance in lower limb prosthesis clients. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2024;48(4):422-430. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000285

- Hamilton AB, Schwarz EB, Thomas HN, Goldstein KM. Moving women veterans’ health research forward: a special supplement. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Suppl3):665– 667. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07606-1

- US Congress. Public Law 116-315: An Act to Improve the Lives of Veterans, S 5108 (2) (F). 116th Congress; 2021. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ315/PLAW-116publ315.pdf

- Gallagher P, MacLachlan M. The Trinity amputation and prosthesis experience scales and quality of life in people with lower-limb amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):730-736. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.07.009

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931-938. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931-938. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9

- Heinemann AW, Bode RK, O’Reilly C. Development and measurement properties of the orthotics and prosthetics users’ survey (OPUS): a comprehensive set of clinical outcome instruments. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):191-206. doi:10.1080/03093640308726682

- Resnik LJ, Borgia ML, Clark MA. A national survey of prosthesis use in veterans with major upper limb amputation: comparisons by gender. PM R. 2020;12(11):1086-1098. doi:10.1002/pmrj.12351

- Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(3):229-238. doi:10.1023/a:1023254226592

- Østlie K, Lesjø IM, Franklin RJ, Garfelt B, Skjeldal OH, Magnus P. Prosthesis rejection in acquired major upper-limb amputees: a population-based survey. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(4):294-303. doi:10.3109/17483107.2011.635405

- Pezzin LE, Dillingham TR, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim P, Rossbach P. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic limb devices and related services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):723-729. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.002

- Deans S, Burns D, McGarry A, Murray K, Mutrie N. Motivations and barriers to prosthesis users participation in physical activity, exercise and sport: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2012;36(3):260-269. doi:10.1177/0309364612437905

- McDonald CL, Kahn A, Hafner BJ, Morgan SJ. Prevalence of secondary prosthesis use in lower limb prosthesis users. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;46(5):1016-1022. doi:10.1080/09638288.2023.2182919

- Baars EC, Schrier E, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB. Prosthesis satisfaction in lower limb amputees: a systematic review of associated factors and questionnaires. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(39):e12296. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012296

- Murray CD, Fox J. Body image and prosthesis satisfaction in the lower limb amputee. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(17):925–931. doi:10.1080/09638280210150014

- Major MJ, Quinlan J, Hansen AH, Esposito ER. Effects of women’s footwear on the mechanical function of heel-height accommodating prosthetic feet. PLoS One. 2022;17(1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262910.

- Kuo PB, Lehavot K, Thomas RM, et al. Gender differences in prosthesis-related outcomes among veterans: results of a national survey of U.S. veterans. PM R. 2024;16(3):239- 249. doi:10.1002/pmrj.13028

- Asano M, Rushton P, Miller WC, Deathe BA. Predictors of quality of life among individuals who have a lower limb amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32(2):231-243. doi:10.1080/03093640802024955

Limb loss is a significant and growing concern in the United States. Nearly 2 million Americans are living with limb loss, and up to 185,000 people undergo amputations annually.1-4 Of these patients, about 35% are women.5 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides about 10% of US amputations.6-8 Between 2015 and 2019, the number of prosthetic devices provided to female veterans increased from 3.3 million to 4.6 million.5,9,10

Previous research identified disparities in prosthetic care between men and women, both within and outside the VHA. These disparities include slower prosthesis prescription and receipt among women, in addition to differences in self-reported mobility, satisfaction, rates of prosthesis rejection, and challenges related to prosthesis appearance and fit.5,10,11 Recent studies suggest women tend to have worse outcomes following amputation, and are underrepresented in amputation research.12,13 However, these disparities are poorly described in a large, national sample. Because women represent a growing portion of patients with limb loss in the VHA, understanding their needs is critical.14

The Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, MD Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020 was enacted, in part, to improve the care provided to women veterans.15 The law required the VHA to conduct a survey of ≥ 50,000 veterans to assess the satisfaction of women veterans with prostheses provided by the VHA. To comply with this legislation and understand how women veterans rate their prostheses and related care in the VHA, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Center for Collaborative Evaluation (VACE) conducted a large national survey of veterans with limb loss that oversampled women veterans. This article describes the survey results, including characteristics of female veterans with limb loss receiving care from the VHA, assesses their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care, and highlights where their responses differ from those of male veterans.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, mixedmode survey of eligible amputees in the VHA Support Service Capital Assets Amputee Data Cube. We identified a cohort of veterans with any major amputation (above the ankle or wrist) or partial hand or foot amputation who received VHA care between October 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020. The final cohort yielded 46,646 potentially eligible veterans. Thirty-three had invalid contact information, leaving 46,613 veterans who were asked to participate, including 1356 women.

Survey

We created a survey instrument de novo that included questions from validated instruments, including the Trinity Amputation Prosthesis and Experience Scales to assess prosthetic device satisfaction, the Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire to assess quality of life (QOL) satisfaction, and the Orthotics Prosthetics Users Survey to assess prosthesis-related care satisfaction. 16-18 Additional questions were incorporated from a survey of veterans with upper limb amputation to assess the importance of cosmetic considerations related to the prosthesis and comfort with prosthesis use in intimate relationships.19 Questions were also included to assess amputation type, year of amputation, if a prosthesis was currently used, reasons for ceasing use of a prosthesis, reasons for never using a prosthesis, the types of prostheses used, intensity of prosthesis use, satisfaction with time required to receive a prosthetic limb, and if the prosthesis reflected the veteran’s selfidentified gender. Veterans were asked to answer questions based on their most recent amputation.

We tested the survey using cognitive interviews with 6 veterans to refine the survey and better understand how veterans interpreted the questions. Pilot testers completed the survey and participated in individual interviews with experienced interviewers (CL and RRK) to describe how they selected their responses.20 This feedback was used to refine the survey. The online survey was programmed using Qualtrics Software and manually translated into Spanish.

Given the multimodal design, surveys were distributed by email, text message, and US Postal Service (USPS). Surveys were emailed to all veterans for whom a valid email address was available. If emails were undeliverable, veterans were contacted via text message or the USPS. Surveys were distributed by text message to all veterans without an email address but with a cellphone number. We were unable to consistently identify invalid numbers among all text message recipients. Invitations with a survey URL and QR code were sent via USPS to veterans who had no valid email address or cellphone number. Targeted efforts were made to increase the response rate for women. A random sample of 200 women who had not completed the survey 2 weeks prior to the closing date (15% of women in sample) was selected to receive personal phone calls. Another random sample of 400 women was selected to receive personalized outreach emails. The survey data were confidential, and responses could not be traced to identifying information.

Data Analyses

We conducted a descriptive analysis, including percentages and means for responses to variables focused on describing amputation characteristics, prosthesis characteristics, and QOL. All data, including missing values, were used to document the percentage of respondents for each question. Removing missing data from the denominator when calculating percentages could introduce bias to the analysis because we cannot be certain data are missing at random. Missing variables were removed to avoid underinflation of mean scores.

We compared responses across 2 groups: individuals who self-identified as men and individuals who self-identified as women. For each question, we assessed whether each of these groups differed significantly from the remaining sample. For example, we examined whether the percentage of men who answered affirmatively to a question was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as male, and whether the percentage of women who answered affirmatively was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as female. We utilized x2 tests to determine significant differences for percentage calculations and t tests to determine significant differences in means across gender.

Since conducting multiple comparisons within a dataset may result in inflating statistical significance (type 1 errors), we used a more conservative estimate of statistical significance (α = 0.01) and high significance (α = 0.001). This study was deemed quality improvement by the VHA Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Services (12RPS) and acknowledged by the VA Research Office at Eastern Colorado Health Care System and was not subject to institutional review board review.

Results

Surveys were distributed to 46,613 veterans and were completed by 4981 respondents for a 10.7% overall response rate. Survey respondents were generally similar to the eligible population invited to participate, but the proportion of women who completed the survey was higher than the proportion of women eligible to participate (2.0% of eligible population vs 16.7% of respondents), likely due to specific efforts to target women. Survey respondents were slightly younger than the general population (67.3 years vs 68.7 years), less likely to be male (97.1% vs 83.3%), showed similar representation of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans (4.4% vs 4.1%), and were less likely to have diabetes (58.0% vs 52.7% had diabetes) (Table 1).

The mean age of male respondents was 67.3 years, while the mean age of female respondents was 58.3 years. The majority of respondents were male (83.3%) and White (77.2%). Female respondents were less likely to have diabetes (35.4% of women vs 53.5% of men) and less likely to report that their most recent amputation resulted from diabetes (10.1% of women vs 22.2% of men). Women respondents were more likely to report an amputation due to other causes, such as adverse results of surgery, neurologic disease, suicide attempt, blood clots, tumors, rheumatoid arthritis, and revisions of previous amputations. Most women respondents did not serve during the OEF or OIF eras. The most common amputation site for women respondents was lower limb, either below the knee and above the ankle or above the knee.

Most participants use an everyday prosthesis, but women were more likely to report using a sports-specific prosthesis (Table 2). Overall, most respondents report using a prosthesis (87.7%); however, women were more likely to report not using a prosthesis (19.4% of women vs 11.1% of men; P ≤ .01). Additionally, a lower proportion of women report using a prosthesis for < 12 hours per day (30.6% of women vs 46.4% of men; P ≤ .01) or using a prosthesis every day (54.8% of women vs 74.6% of men; P ≤ .001).

In the overall sample, the mean satisfaction score with a prosthesis was 2.7 on a 5-point scale, and women had slightly lower overall satisfaction scores (2.6 for women vs 2.7 for men; P ≤ .001) (Table 3). Women also had lower satisfaction scores related to appearance, usefulness, reliability, and comfort. Women were more likely to indicate that it was very important to be able to wear jewelry and accessories (20.2% of women vs 11.6% of men; P ≤ .01), while men were less likely to indicate that it was somewhat or very important that the prosthesis not restrict clothing or shoes (95.2% of women vs 82.9% of men; P ≤ .001). Men were more likely than women to report being comfortable or very comfortable using their prosthesis in intimate contact: 40.5% vs 29.0%, respectively (P ≤ .001).

Overall, participants reported high satisfaction with appointment times, wait times, courteous treatment, opportunities to express concerns, and staff responsiveness. Men were slightly more likely than women to be satisfied with training (P ≤ 0.001) and problem discussion (P ≤ 0.01) (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences in satisfaction or QOL ratings between women and men. The overall sample rated both QOL and satisfaction with QOL 6.7 on a 10-point scale.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to characterize the experience of veterans with limb loss receiving care in the VHA and assess their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care. We received responses from nearly 5000 veterans, 158 of whom were women. Women veteran respondents were slightly younger and less likely to have an amputation due to diabetes. We did not observe significant differences in amputation level between men and women but women were less likely to use a prosthesis, reported lower intensity of prosthesis use, and were less satisfied with certain aspects of their prostheses. Women may also be less satisfied with prosthesis training and problem discussion. However, we found no differences in QOL ratings between men and women.

Findings indicating women were more likely to report not using a prosthesis and that a lower proportion of women report using a prosthesis for > 12 hours a day or every day are consistent with previous research. 21,22 Interestingly, women were more likely to report using a sports-specific prosthesis. This is notable because prior research suggests that individuals with amputations may avoid participating in sports and exercise, and a lack of access to sports-specific prostheses may inhibit physical activity.23,24 Women in this sample were slightly less satisfied with their prostheses overall and reported lower satisfaction scores regarding appearance, usefulness, reliability, and comfort, consistent with previous findings.25

A lower percentage of women in this sample reported being comfortable or very comfortable using their prosthesis during intimate contact. Previous research on prosthesis satisfaction suggests individuals who rate prosthesis satisfaction lower also report lower body image across genders. 26 While women in this sample did not rate their prosthesis satisfaction lower than men, they did report lower intensity of prosthesis use, suggesting potential issues with their prostheses this survey did not evaluate. Women indicated the importance of prostheses not restricting jewelry, accessories, clothing, or shoes. These results have significant clinical and social implications. A recent qualitative study emphasizes that women veterans feel prostheses are primarily designed for men and may not work well with their physiological needs.9 Research focused on limbs better suited to women’s bodies could result in better fitting sockets, lightweight limbs, or less bulky designs. Additional research has also explored the difficulties in accommodating a range of footwear for patients with lower limb amputation. One study found that varying footwear heights affect the function of adjustable prosthetic feet in ways that may not be optimal.27

Ratings of satisfaction with prosthesisrelated services between men and women in this sample are consistent with a recent study showing that women veterans do not have significant differences in satisfaction with prosthesis-related services.28 However, this study focused specifically on lower limb amputations, while the respondents of this study include those with both upper and lower limb amputations. Importantly, our findings that women are less likely to be satisfied with prosthesis training and problem discussions support recent qualitative findings in which women expressed a desire to work with prosthetists who listen to them, take their concerns seriously, and seek solutions that fit their needs. We did not observe a difference in QOL ratings between men and women in the sample despite lower satisfaction among women with some elements of prosthesis-related services. Previous research suggests many factors impact QOL after amputation, most notably time since amputation.16,29

Limitations

This survey was deployed in a short timeline that did not allow for careful sample selection or implementing strategies to increase response rate. Additionally, the study was conducted among veterans receiving care in the VHA, and findings may not be generalizable to limb loss in other settings. Finally, the discrepancy in number of respondents who identified as men vs women made it difficult to compare differences between the 2 groups.

Conclusions

This is the largest sample of survey respondents of veterans with limb loss to date. While the findings suggest veterans are generally satisfied with prosthetic-related services overall, they also highlight several areas for improvement with services or prostheses. Given that most veterans with limb loss are men, there is a significant discrepancy between the number of women and men respondents. Additional studies with more comparable numbers of men and women have found similar ratings of satisfaction with prostheses and services.28 Further research specifically focused on improving the experiences of women should focus on better characterizing their experiences and identifying how they differ from those of male veterans. For example, understanding how to engage female veterans with limb loss in prosthesis training and problem discussions may improve their experience with their care teams and improve their use of prostheses. Understanding experiences and needs that are specific to women could lead to the development of processes, resources, or devices that are tailored to the unique requirements of women with limb loss.

Limb loss is a significant and growing concern in the United States. Nearly 2 million Americans are living with limb loss, and up to 185,000 people undergo amputations annually.1-4 Of these patients, about 35% are women.5 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides about 10% of US amputations.6-8 Between 2015 and 2019, the number of prosthetic devices provided to female veterans increased from 3.3 million to 4.6 million.5,9,10

Previous research identified disparities in prosthetic care between men and women, both within and outside the VHA. These disparities include slower prosthesis prescription and receipt among women, in addition to differences in self-reported mobility, satisfaction, rates of prosthesis rejection, and challenges related to prosthesis appearance and fit.5,10,11 Recent studies suggest women tend to have worse outcomes following amputation, and are underrepresented in amputation research.12,13 However, these disparities are poorly described in a large, national sample. Because women represent a growing portion of patients with limb loss in the VHA, understanding their needs is critical.14

The Johnny Isakson and David P. Roe, MD Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2020 was enacted, in part, to improve the care provided to women veterans.15 The law required the VHA to conduct a survey of ≥ 50,000 veterans to assess the satisfaction of women veterans with prostheses provided by the VHA. To comply with this legislation and understand how women veterans rate their prostheses and related care in the VHA, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Center for Collaborative Evaluation (VACE) conducted a large national survey of veterans with limb loss that oversampled women veterans. This article describes the survey results, including characteristics of female veterans with limb loss receiving care from the VHA, assesses their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care, and highlights where their responses differ from those of male veterans.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, mixedmode survey of eligible amputees in the VHA Support Service Capital Assets Amputee Data Cube. We identified a cohort of veterans with any major amputation (above the ankle or wrist) or partial hand or foot amputation who received VHA care between October 1, 2019, and September 30, 2020. The final cohort yielded 46,646 potentially eligible veterans. Thirty-three had invalid contact information, leaving 46,613 veterans who were asked to participate, including 1356 women.

Survey

We created a survey instrument de novo that included questions from validated instruments, including the Trinity Amputation Prosthesis and Experience Scales to assess prosthetic device satisfaction, the Prosthesis Evaluation Questionnaire to assess quality of life (QOL) satisfaction, and the Orthotics Prosthetics Users Survey to assess prosthesis-related care satisfaction. 16-18 Additional questions were incorporated from a survey of veterans with upper limb amputation to assess the importance of cosmetic considerations related to the prosthesis and comfort with prosthesis use in intimate relationships.19 Questions were also included to assess amputation type, year of amputation, if a prosthesis was currently used, reasons for ceasing use of a prosthesis, reasons for never using a prosthesis, the types of prostheses used, intensity of prosthesis use, satisfaction with time required to receive a prosthetic limb, and if the prosthesis reflected the veteran’s selfidentified gender. Veterans were asked to answer questions based on their most recent amputation.

We tested the survey using cognitive interviews with 6 veterans to refine the survey and better understand how veterans interpreted the questions. Pilot testers completed the survey and participated in individual interviews with experienced interviewers (CL and RRK) to describe how they selected their responses.20 This feedback was used to refine the survey. The online survey was programmed using Qualtrics Software and manually translated into Spanish.

Given the multimodal design, surveys were distributed by email, text message, and US Postal Service (USPS). Surveys were emailed to all veterans for whom a valid email address was available. If emails were undeliverable, veterans were contacted via text message or the USPS. Surveys were distributed by text message to all veterans without an email address but with a cellphone number. We were unable to consistently identify invalid numbers among all text message recipients. Invitations with a survey URL and QR code were sent via USPS to veterans who had no valid email address or cellphone number. Targeted efforts were made to increase the response rate for women. A random sample of 200 women who had not completed the survey 2 weeks prior to the closing date (15% of women in sample) was selected to receive personal phone calls. Another random sample of 400 women was selected to receive personalized outreach emails. The survey data were confidential, and responses could not be traced to identifying information.

Data Analyses

We conducted a descriptive analysis, including percentages and means for responses to variables focused on describing amputation characteristics, prosthesis characteristics, and QOL. All data, including missing values, were used to document the percentage of respondents for each question. Removing missing data from the denominator when calculating percentages could introduce bias to the analysis because we cannot be certain data are missing at random. Missing variables were removed to avoid underinflation of mean scores.

We compared responses across 2 groups: individuals who self-identified as men and individuals who self-identified as women. For each question, we assessed whether each of these groups differed significantly from the remaining sample. For example, we examined whether the percentage of men who answered affirmatively to a question was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as male, and whether the percentage of women who answered affirmatively was significantly higher or lower than that of individuals not identifying as female. We utilized x2 tests to determine significant differences for percentage calculations and t tests to determine significant differences in means across gender.

Since conducting multiple comparisons within a dataset may result in inflating statistical significance (type 1 errors), we used a more conservative estimate of statistical significance (α = 0.01) and high significance (α = 0.001). This study was deemed quality improvement by the VHA Rehabilitation and Prosthetic Services (12RPS) and acknowledged by the VA Research Office at Eastern Colorado Health Care System and was not subject to institutional review board review.

Results

Surveys were distributed to 46,613 veterans and were completed by 4981 respondents for a 10.7% overall response rate. Survey respondents were generally similar to the eligible population invited to participate, but the proportion of women who completed the survey was higher than the proportion of women eligible to participate (2.0% of eligible population vs 16.7% of respondents), likely due to specific efforts to target women. Survey respondents were slightly younger than the general population (67.3 years vs 68.7 years), less likely to be male (97.1% vs 83.3%), showed similar representation of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) veterans (4.4% vs 4.1%), and were less likely to have diabetes (58.0% vs 52.7% had diabetes) (Table 1).

The mean age of male respondents was 67.3 years, while the mean age of female respondents was 58.3 years. The majority of respondents were male (83.3%) and White (77.2%). Female respondents were less likely to have diabetes (35.4% of women vs 53.5% of men) and less likely to report that their most recent amputation resulted from diabetes (10.1% of women vs 22.2% of men). Women respondents were more likely to report an amputation due to other causes, such as adverse results of surgery, neurologic disease, suicide attempt, blood clots, tumors, rheumatoid arthritis, and revisions of previous amputations. Most women respondents did not serve during the OEF or OIF eras. The most common amputation site for women respondents was lower limb, either below the knee and above the ankle or above the knee.

Most participants use an everyday prosthesis, but women were more likely to report using a sports-specific prosthesis (Table 2). Overall, most respondents report using a prosthesis (87.7%); however, women were more likely to report not using a prosthesis (19.4% of women vs 11.1% of men; P ≤ .01). Additionally, a lower proportion of women report using a prosthesis for < 12 hours per day (30.6% of women vs 46.4% of men; P ≤ .01) or using a prosthesis every day (54.8% of women vs 74.6% of men; P ≤ .001).

In the overall sample, the mean satisfaction score with a prosthesis was 2.7 on a 5-point scale, and women had slightly lower overall satisfaction scores (2.6 for women vs 2.7 for men; P ≤ .001) (Table 3). Women also had lower satisfaction scores related to appearance, usefulness, reliability, and comfort. Women were more likely to indicate that it was very important to be able to wear jewelry and accessories (20.2% of women vs 11.6% of men; P ≤ .01), while men were less likely to indicate that it was somewhat or very important that the prosthesis not restrict clothing or shoes (95.2% of women vs 82.9% of men; P ≤ .001). Men were more likely than women to report being comfortable or very comfortable using their prosthesis in intimate contact: 40.5% vs 29.0%, respectively (P ≤ .001).

Overall, participants reported high satisfaction with appointment times, wait times, courteous treatment, opportunities to express concerns, and staff responsiveness. Men were slightly more likely than women to be satisfied with training (P ≤ 0.001) and problem discussion (P ≤ 0.01) (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences in satisfaction or QOL ratings between women and men. The overall sample rated both QOL and satisfaction with QOL 6.7 on a 10-point scale.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to characterize the experience of veterans with limb loss receiving care in the VHA and assess their satisfaction with prostheses and prosthetic care. We received responses from nearly 5000 veterans, 158 of whom were women. Women veteran respondents were slightly younger and less likely to have an amputation due to diabetes. We did not observe significant differences in amputation level between men and women but women were less likely to use a prosthesis, reported lower intensity of prosthesis use, and were less satisfied with certain aspects of their prostheses. Women may also be less satisfied with prosthesis training and problem discussion. However, we found no differences in QOL ratings between men and women.

Findings indicating women were more likely to report not using a prosthesis and that a lower proportion of women report using a prosthesis for > 12 hours a day or every day are consistent with previous research. 21,22 Interestingly, women were more likely to report using a sports-specific prosthesis. This is notable because prior research suggests that individuals with amputations may avoid participating in sports and exercise, and a lack of access to sports-specific prostheses may inhibit physical activity.23,24 Women in this sample were slightly less satisfied with their prostheses overall and reported lower satisfaction scores regarding appearance, usefulness, reliability, and comfort, consistent with previous findings.25

A lower percentage of women in this sample reported being comfortable or very comfortable using their prosthesis during intimate contact. Previous research on prosthesis satisfaction suggests individuals who rate prosthesis satisfaction lower also report lower body image across genders. 26 While women in this sample did not rate their prosthesis satisfaction lower than men, they did report lower intensity of prosthesis use, suggesting potential issues with their prostheses this survey did not evaluate. Women indicated the importance of prostheses not restricting jewelry, accessories, clothing, or shoes. These results have significant clinical and social implications. A recent qualitative study emphasizes that women veterans feel prostheses are primarily designed for men and may not work well with their physiological needs.9 Research focused on limbs better suited to women’s bodies could result in better fitting sockets, lightweight limbs, or less bulky designs. Additional research has also explored the difficulties in accommodating a range of footwear for patients with lower limb amputation. One study found that varying footwear heights affect the function of adjustable prosthetic feet in ways that may not be optimal.27

Ratings of satisfaction with prosthesisrelated services between men and women in this sample are consistent with a recent study showing that women veterans do not have significant differences in satisfaction with prosthesis-related services.28 However, this study focused specifically on lower limb amputations, while the respondents of this study include those with both upper and lower limb amputations. Importantly, our findings that women are less likely to be satisfied with prosthesis training and problem discussions support recent qualitative findings in which women expressed a desire to work with prosthetists who listen to them, take their concerns seriously, and seek solutions that fit their needs. We did not observe a difference in QOL ratings between men and women in the sample despite lower satisfaction among women with some elements of prosthesis-related services. Previous research suggests many factors impact QOL after amputation, most notably time since amputation.16,29

Limitations

This survey was deployed in a short timeline that did not allow for careful sample selection or implementing strategies to increase response rate. Additionally, the study was conducted among veterans receiving care in the VHA, and findings may not be generalizable to limb loss in other settings. Finally, the discrepancy in number of respondents who identified as men vs women made it difficult to compare differences between the 2 groups.

Conclusions

This is the largest sample of survey respondents of veterans with limb loss to date. While the findings suggest veterans are generally satisfied with prosthetic-related services overall, they also highlight several areas for improvement with services or prostheses. Given that most veterans with limb loss are men, there is a significant discrepancy between the number of women and men respondents. Additional studies with more comparable numbers of men and women have found similar ratings of satisfaction with prostheses and services.28 Further research specifically focused on improving the experiences of women should focus on better characterizing their experiences and identifying how they differ from those of male veterans. For example, understanding how to engage female veterans with limb loss in prosthesis training and problem discussions may improve their experience with their care teams and improve their use of prostheses. Understanding experiences and needs that are specific to women could lead to the development of processes, resources, or devices that are tailored to the unique requirements of women with limb loss.

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(3):422-429. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.005

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ. Limb amputation and limb deficiency: epidemiology and recent trends in the united states. South Med J. 2002;95(8):875-883. doi:10.1097/00007611-200208000-00018

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, Shore AD. Reamputation, mortality, and health care costs among persons with dysvascular lower-limb amputations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(3):480-486. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.06.072

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ambulatory and inpatient procedures in the United States. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/98facts/ambulat.htm

- Ljung J, Iacangelo A. Identifying and acknowledging a sex gap in lower-limb prosthetics. JPO. 2024;36(1):e18-e24. doi:10.1097/JPO.0000000000000470

- Feinglass J, Brown JL, LoSasso A, et al. Rates of lower-extremity amputation and arterial reconstruction in the united states, 1979 to 1996. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(8):1222- 1227. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.8.1222

- Mayfield JA, Reiber GE, Maynard C, Czerniecki JM, Caps MT, Sangeorzan BJ. Trends in lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration, 1989-1998. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37(1):23-30.

- Feinglass J, Pearce WH, Martin GJ, et al. Postoperative and late survival outcomes after major amputation: findings from the department of veterans affairs national surgical quality improvement program. Surgery. 2001;130(1):21-29. doi:10.1067/msy.2001.115359

- Lehavot K, Young JP, Thomas RM, et al. Voices of women veterans with lower limb prostheses: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(3):799-805. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07572-8

- US Government Accountability Office. COVID-19: Opportunities to improve federal response. GAO-21-60. Published November 12, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-60

- Littman AJ, Peterson AC, Korpak A, et al. Differences in prosthetic prescription between men and women veterans after transtibial or transfemoral lowerextremity amputation: a longitudinal cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;104(8)1274-1281. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2023.02.011

- Cimino SR, Vijayakumar A, MacKay C, Mayo AL, Hitzig SL, Guilcher SJT. Sex and gender differences in quality of life and related domains for individuals with adult acquired lower-limb amputation: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022 Oct 23;44(22):6899-6925. doi:10.1080/09638288.2021.1974106

- DadeMatthews OO, Roper JA, Vazquez A, Shannon DM, Sefton JM. Prosthetic device and service satisfaction, quality of life, and functional performance in lower limb prosthesis clients. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2024;48(4):422-430. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000285

- Hamilton AB, Schwarz EB, Thomas HN, Goldstein KM. Moving women veterans’ health research forward: a special supplement. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Suppl3):665– 667. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07606-1

- US Congress. Public Law 116-315: An Act to Improve the Lives of Veterans, S 5108 (2) (F). 116th Congress; 2021. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ315/PLAW-116publ315.pdf

- Gallagher P, MacLachlan M. The Trinity amputation and prosthesis experience scales and quality of life in people with lower-limb amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):730-736. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.07.009

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931-938. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931-938. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9

- Heinemann AW, Bode RK, O’Reilly C. Development and measurement properties of the orthotics and prosthetics users’ survey (OPUS): a comprehensive set of clinical outcome instruments. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):191-206. doi:10.1080/03093640308726682

- Resnik LJ, Borgia ML, Clark MA. A national survey of prosthesis use in veterans with major upper limb amputation: comparisons by gender. PM R. 2020;12(11):1086-1098. doi:10.1002/pmrj.12351

- Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(3):229-238. doi:10.1023/a:1023254226592

- Østlie K, Lesjø IM, Franklin RJ, Garfelt B, Skjeldal OH, Magnus P. Prosthesis rejection in acquired major upper-limb amputees: a population-based survey. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(4):294-303. doi:10.3109/17483107.2011.635405

- Pezzin LE, Dillingham TR, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim P, Rossbach P. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic limb devices and related services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):723-729. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.002

- Deans S, Burns D, McGarry A, Murray K, Mutrie N. Motivations and barriers to prosthesis users participation in physical activity, exercise and sport: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2012;36(3):260-269. doi:10.1177/0309364612437905

- McDonald CL, Kahn A, Hafner BJ, Morgan SJ. Prevalence of secondary prosthesis use in lower limb prosthesis users. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;46(5):1016-1022. doi:10.1080/09638288.2023.2182919

- Baars EC, Schrier E, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB. Prosthesis satisfaction in lower limb amputees: a systematic review of associated factors and questionnaires. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(39):e12296. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012296

- Murray CD, Fox J. Body image and prosthesis satisfaction in the lower limb amputee. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(17):925–931. doi:10.1080/09638280210150014

- Major MJ, Quinlan J, Hansen AH, Esposito ER. Effects of women’s footwear on the mechanical function of heel-height accommodating prosthetic feet. PLoS One. 2022;17(1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262910.

- Kuo PB, Lehavot K, Thomas RM, et al. Gender differences in prosthesis-related outcomes among veterans: results of a national survey of U.S. veterans. PM R. 2024;16(3):239- 249. doi:10.1002/pmrj.13028

- Asano M, Rushton P, Miller WC, Deathe BA. Predictors of quality of life among individuals who have a lower limb amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32(2):231-243. doi:10.1080/03093640802024955

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, Travison TG, Brookmeyer R. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(3):422-429. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.005

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, MacKenzie EJ. Limb amputation and limb deficiency: epidemiology and recent trends in the united states. South Med J. 2002;95(8):875-883. doi:10.1097/00007611-200208000-00018

- Dillingham TR, Pezzin LE, Shore AD. Reamputation, mortality, and health care costs among persons with dysvascular lower-limb amputations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(3):480-486. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.06.072

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ambulatory and inpatient procedures in the United States. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/98facts/ambulat.htm

- Ljung J, Iacangelo A. Identifying and acknowledging a sex gap in lower-limb prosthetics. JPO. 2024;36(1):e18-e24. doi:10.1097/JPO.0000000000000470

- Feinglass J, Brown JL, LoSasso A, et al. Rates of lower-extremity amputation and arterial reconstruction in the united states, 1979 to 1996. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(8):1222- 1227. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.8.1222

- Mayfield JA, Reiber GE, Maynard C, Czerniecki JM, Caps MT, Sangeorzan BJ. Trends in lower limb amputation in the Veterans Health Administration, 1989-1998. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37(1):23-30.

- Feinglass J, Pearce WH, Martin GJ, et al. Postoperative and late survival outcomes after major amputation: findings from the department of veterans affairs national surgical quality improvement program. Surgery. 2001;130(1):21-29. doi:10.1067/msy.2001.115359

- Lehavot K, Young JP, Thomas RM, et al. Voices of women veterans with lower limb prostheses: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(3):799-805. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07572-8

- US Government Accountability Office. COVID-19: Opportunities to improve federal response. GAO-21-60. Published November 12, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-60

- Littman AJ, Peterson AC, Korpak A, et al. Differences in prosthetic prescription between men and women veterans after transtibial or transfemoral lowerextremity amputation: a longitudinal cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;104(8)1274-1281. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2023.02.011

- Cimino SR, Vijayakumar A, MacKay C, Mayo AL, Hitzig SL, Guilcher SJT. Sex and gender differences in quality of life and related domains for individuals with adult acquired lower-limb amputation: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2022 Oct 23;44(22):6899-6925. doi:10.1080/09638288.2021.1974106

- DadeMatthews OO, Roper JA, Vazquez A, Shannon DM, Sefton JM. Prosthetic device and service satisfaction, quality of life, and functional performance in lower limb prosthesis clients. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2024;48(4):422-430. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000285

- Hamilton AB, Schwarz EB, Thomas HN, Goldstein KM. Moving women veterans’ health research forward: a special supplement. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Suppl3):665– 667. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07606-1

- US Congress. Public Law 116-315: An Act to Improve the Lives of Veterans, S 5108 (2) (F). 116th Congress; 2021. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ315/PLAW-116publ315.pdf

- Gallagher P, MacLachlan M. The Trinity amputation and prosthesis experience scales and quality of life in people with lower-limb amputation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):730-736. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.07.009

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931-938. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9

- Legro MW, Reiber GD, Smith DG, del Aguila M, Larsen J, Boone D. Prosthesis evaluation questionnaire for persons with lower limb amputations: assessing prosthesis-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(8):931-938. doi:10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90090-9

- Heinemann AW, Bode RK, O’Reilly C. Development and measurement properties of the orthotics and prosthetics users’ survey (OPUS): a comprehensive set of clinical outcome instruments. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):191-206. doi:10.1080/03093640308726682

- Resnik LJ, Borgia ML, Clark MA. A national survey of prosthesis use in veterans with major upper limb amputation: comparisons by gender. PM R. 2020;12(11):1086-1098. doi:10.1002/pmrj.12351

- Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(3):229-238. doi:10.1023/a:1023254226592

- Østlie K, Lesjø IM, Franklin RJ, Garfelt B, Skjeldal OH, Magnus P. Prosthesis rejection in acquired major upper-limb amputees: a population-based survey. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(4):294-303. doi:10.3109/17483107.2011.635405

- Pezzin LE, Dillingham TR, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim P, Rossbach P. Use and satisfaction with prosthetic limb devices and related services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(5):723-729. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.002

- Deans S, Burns D, McGarry A, Murray K, Mutrie N. Motivations and barriers to prosthesis users participation in physical activity, exercise and sport: a review of the literature. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2012;36(3):260-269. doi:10.1177/0309364612437905

- McDonald CL, Kahn A, Hafner BJ, Morgan SJ. Prevalence of secondary prosthesis use in lower limb prosthesis users. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;46(5):1016-1022. doi:10.1080/09638288.2023.2182919

- Baars EC, Schrier E, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB. Prosthesis satisfaction in lower limb amputees: a systematic review of associated factors and questionnaires. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(39):e12296. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012296

- Murray CD, Fox J. Body image and prosthesis satisfaction in the lower limb amputee. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(17):925–931. doi:10.1080/09638280210150014

- Major MJ, Quinlan J, Hansen AH, Esposito ER. Effects of women’s footwear on the mechanical function of heel-height accommodating prosthetic feet. PLoS One. 2022;17(1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262910.

- Kuo PB, Lehavot K, Thomas RM, et al. Gender differences in prosthesis-related outcomes among veterans: results of a national survey of U.S. veterans. PM R. 2024;16(3):239- 249. doi:10.1002/pmrj.13028

- Asano M, Rushton P, Miller WC, Deathe BA. Predictors of quality of life among individuals who have a lower limb amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32(2):231-243. doi:10.1080/03093640802024955

Satisfaction With Department of Veterans Affairs Prosthetics and Support Services as Reported by Women and Men Veterans

Satisfaction With Department of Veterans Affairs Prosthetics and Support Services as Reported by Women and Men Veterans

Vocacapsaicin Could Lessen Pain, Opioid Use Post Surgery

TOPLINE:

Compared with placebo, administration of vocacapsaicin during bunionectomy reduces pain and decreases opioid consumption in the first 96 hours after surgery, with no local or systemic toxicity.

METHODOLOGY:

- This triple-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial included 147 patients undergoing bunionectomy.

- Patients were randomly assigned to receive 14 mL of either 0.05 mg/mL vocacapsaicin, 0.15 mg/mL vocacapsaicin, 0.30 mg/mL vocacapsaicin, or placebo at the surgical site during wound closure. Except for the study drug, all patients received identical perioperative analgesics.

- Patients were observed for 96 hours post-surgery, with follow-up visits on days 8, 15, and 29 to monitor for pain and adverse events.

- The primary endpoint was overall levels of pain at rest through the first 96 hours after surgery for the 0.30-mg/mL vocacapsaicin group.

- The secondary endpoints included the percentage of patients who did not require opioids and total opioid consumption through 96 hours, as well as pain scores during the first postoperative week.

TAKEAWAY:

- Vocacapsaicin (0.30 mg/mL) reduced pain at rest by 33% over the first 96 hours, compared with placebo (P = .005).

- Overall, 26% of patients who received the 0.30-mg/mL dose of vocacapsaicin did not require opioids through 96 hours compared with 5% of patients receiving placebo (P = .025).

- The researchers reported no difference in the rate, type, or severity of adverse events in the four study groups, consistent with typical recovery from bunionectomy.

IN PRACTICE:

“These data suggest that intraoperative administration of vocacapsaicin may provide substantial benefits in other surgical procedures,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Steven L. Shafer, MD, of the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine at Stanford University in Stanford, California, and published in the June 2024 issue of Anesthesiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The use of opioids was restricted from 0 to 96 hours after surgery, which did not reflect typical clinical practice. The range of vocacapsaicin concentrations tested may not have been extensive enough, as concentrations > 0.30 mg/mL might have provided better analgesia.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Concentric Analgesics. Two authors declared being employed by Concentric Analgesics. Other authors declared having several ties with many sources, including the funding agency.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Compared with placebo, administration of vocacapsaicin during bunionectomy reduces pain and decreases opioid consumption in the first 96 hours after surgery, with no local or systemic toxicity.

METHODOLOGY:

- This triple-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial included 147 patients undergoing bunionectomy.

- Patients were randomly assigned to receive 14 mL of either 0.05 mg/mL vocacapsaicin, 0.15 mg/mL vocacapsaicin, 0.30 mg/mL vocacapsaicin, or placebo at the surgical site during wound closure. Except for the study drug, all patients received identical perioperative analgesics.

- Patients were observed for 96 hours post-surgery, with follow-up visits on days 8, 15, and 29 to monitor for pain and adverse events.

- The primary endpoint was overall levels of pain at rest through the first 96 hours after surgery for the 0.30-mg/mL vocacapsaicin group.

- The secondary endpoints included the percentage of patients who did not require opioids and total opioid consumption through 96 hours, as well as pain scores during the first postoperative week.

TAKEAWAY:

- Vocacapsaicin (0.30 mg/mL) reduced pain at rest by 33% over the first 96 hours, compared with placebo (P = .005).

- Overall, 26% of patients who received the 0.30-mg/mL dose of vocacapsaicin did not require opioids through 96 hours compared with 5% of patients receiving placebo (P = .025).

- The researchers reported no difference in the rate, type, or severity of adverse events in the four study groups, consistent with typical recovery from bunionectomy.

IN PRACTICE:

“These data suggest that intraoperative administration of vocacapsaicin may provide substantial benefits in other surgical procedures,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Steven L. Shafer, MD, of the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine at Stanford University in Stanford, California, and published in the June 2024 issue of Anesthesiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The use of opioids was restricted from 0 to 96 hours after surgery, which did not reflect typical clinical practice. The range of vocacapsaicin concentrations tested may not have been extensive enough, as concentrations > 0.30 mg/mL might have provided better analgesia.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Concentric Analgesics. Two authors declared being employed by Concentric Analgesics. Other authors declared having several ties with many sources, including the funding agency.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Compared with placebo, administration of vocacapsaicin during bunionectomy reduces pain and decreases opioid consumption in the first 96 hours after surgery, with no local or systemic toxicity.

METHODOLOGY:

- This triple-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial included 147 patients undergoing bunionectomy.

- Patients were randomly assigned to receive 14 mL of either 0.05 mg/mL vocacapsaicin, 0.15 mg/mL vocacapsaicin, 0.30 mg/mL vocacapsaicin, or placebo at the surgical site during wound closure. Except for the study drug, all patients received identical perioperative analgesics.

- Patients were observed for 96 hours post-surgery, with follow-up visits on days 8, 15, and 29 to monitor for pain and adverse events.

- The primary endpoint was overall levels of pain at rest through the first 96 hours after surgery for the 0.30-mg/mL vocacapsaicin group.

- The secondary endpoints included the percentage of patients who did not require opioids and total opioid consumption through 96 hours, as well as pain scores during the first postoperative week.

TAKEAWAY:

- Vocacapsaicin (0.30 mg/mL) reduced pain at rest by 33% over the first 96 hours, compared with placebo (P = .005).

- Overall, 26% of patients who received the 0.30-mg/mL dose of vocacapsaicin did not require opioids through 96 hours compared with 5% of patients receiving placebo (P = .025).

- The researchers reported no difference in the rate, type, or severity of adverse events in the four study groups, consistent with typical recovery from bunionectomy.

IN PRACTICE:

“These data suggest that intraoperative administration of vocacapsaicin may provide substantial benefits in other surgical procedures,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Steven L. Shafer, MD, of the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine at Stanford University in Stanford, California, and published in the June 2024 issue of Anesthesiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The use of opioids was restricted from 0 to 96 hours after surgery, which did not reflect typical clinical practice. The range of vocacapsaicin concentrations tested may not have been extensive enough, as concentrations > 0.30 mg/mL might have provided better analgesia.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Concentric Analgesics. Two authors declared being employed by Concentric Analgesics. Other authors declared having several ties with many sources, including the funding agency.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Life-Threatening Issue in Need of Help

The photo of the patient’s foot, sent from his campsite, included a cheeky note: “I remember you telling me that getting in trouble doing something was better than getting in trouble doing nothing. This lets me get out there and know that I have feedback.”

The “this” was the patient’s “foot selfie,” an approach that allows patients at a risk for diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) to snap a picture and send it to their healthcare providers for evaluation.

This particular patient had an extensive history of previous wounds. Some had essentially kept him house-bound in the past, as he was afraid to get another one.

This time, however, he got an all-clear to keep on camping, “and we scheduled him in on the following Tuesday [for follow-up],” said the camper’s physician David G. Armstrong, DPM, MD, PhD, professor of surgery and neurological surgery, USC Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles.

Dr. Armstrong is one of the researchers evaluating the concept of foot selfies. It’s a welcome advance, he and others said, and has been shown to help heal wounds and reverse pre-ulcer lesions. Research on foot selfies continues, but much more is needed to solve the issue of DFUs, diabetic foot infections (DFIs), and the high rates of reinfection, experts know.

Worldwide, about 18.6 million people have a DFU each year, including 1.6 million in the United States. About 50%-60% of ulcers become infected, with 20% of moderate to severe infections requiring amputation of the limb. The 5-year mortality rate for DFUs is 30%, but it climbs to 70% after amputation. While about 40% of ulcers heal within 12 weeks, 42% recur at the 1-year mark, setting up a vicious and costly cycle. Healthcare costs for patients with diabetes and DFUs are five times as high as costs for patients with diabetes but no DFUs. The per capita cost to treat a DFU in America is $17,500.

While the statistics paint a grim picture, progress is being made on several fronts:

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance on the development of drugs for DFUs, under evaluation, is forthcoming.

- New treatments are under study.

- A multidisciplinary team approach is known to improve outcomes.

Anatomy of a DFU

When neuropathy develops in those with diabetes, they no longer have what Dr. Armstrong calls the “gift” of pain perception. “They can wear a hole in their foot like you and I wear a hole in our sock or shoe,” he said. “That hole is called a diabetic foot ulcer.”

A DFU is an open wound on the foot, often occurring when bleeding develops beneath a callus and then the callus wears away. Deeper tissues of the foot are then exposed.

About half of the DFUs get infected, hence the FDA guidance, said Dr. Armstrong, who is also founding president of the American Limb Preservation Society, which aims to eliminate preventable amputations within the next generation. Every 20 seconds, Dr. Armstrong said, someone in the world loses a leg due to diabetes.

FDA Guidance on Drug Development for DFIs

In October, the FDA issued draft guidance for industry to articulate the design of clinical trials for developing antibacterial drugs to treat DFIs without concomitant bone and joint involvement. Comments closed on December 18. Among the points in the guidance, which is nonbinding, are to include DFIs of varying depths and extent in phase 3 trials and ideally to include only those patients who have not had prior antibacterial treatment for the current DFI.

According to an FDA spokesperson, “The agency is working to finalize the guidance. However, a timeline for its release has not yet been established.”

The good news about the upcoming FDA guidance, Dr. Armstrong said, is that the agency has realized the importance of treating the infections. Fully one third of direct costs of care for diabetes are spent on the lower extremities, he said. Keeping patients out of the hospital, uninfected, and “keeping legs on bodies” are all important goals, he said.