User login

Imiquimod Induces Sustained Remission of Actinic Damage: A Case Report Spanning One Decade of Observation

Sun damage and chronic exposure to UV radiation have been recognized as causative factors for the development of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), its precursor actinic keratosis (AK), and basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Although surgical treatment is necessary for most advanced cases of skin cancer, several other therapeutic approaches have been described including the use of topical chemotherapy agents such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod. Unlike surgery, these agents provide the added benefit of treating larger fields of photodamaged skin. With the increasing prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), the use of multiple topical agents for treatment will continue to become more common.

We present the case of a patient who underwent field therapy with topical 5-FU for diffuse actinic damage and AKs. There was no subsequent inflammatory response within the perimeter of a BCC that had been treated with imiquimod 10 years prior.

Case Report

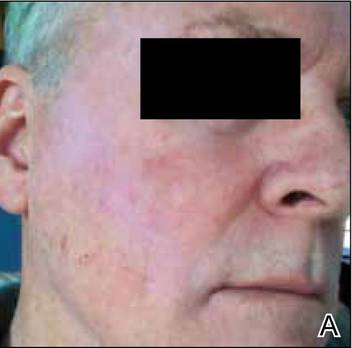

An otherwise healthy 58-year-old man with a history of long-standing diffuse sun damage and multiple prior NMSCs presented for treatment of a recurrent BCC on the right cheek. The patient reported that the BCC had initially been biopsied and excised by his primary care physician. Two months later local recurrence was noted by the primary care physician and the patient was subsequently referred to our dermatology office. A 2-month treatment course with daily imiquimod cream 5% was initiated. This treatment caused extensive inflammation of the right cheek but was otherwise well tolerated (Figure 1).

|

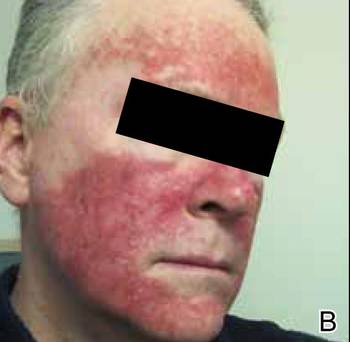

During a routine skin cancer screening 10 years later, no recurrence of the BCC was noted on the right cheek; however, the patient had developed multiple AKs on the face. Therapeutic options were discussed with the patient; he agreed to topical field therapy with 5-FU cream 0.5%. The patient applied the 5-FU cream to the entire face nightly for 1 month. During this time he experienced a brisk inflammatory response with painful cracking and redness of the skin. On follow-up, it was noted that the area on the right cheek that had been treated with imiquimod 10 years prior showed no inflammatory response despite nightly application of 5-FU cream to the area (Figure 2). The patient denied any routine use of sunscreen or other sun-protective practices.

Comment

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in the United States with an incidence of 1.4% to 2% per year. It has become more prevalent in recent decades, likely due to genetic predisposition and increasing cumulative sun exposure.1-4 A variety of treatment options are available. Surgical interventions include destruction via electrodesiccation and curettage, local excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery. One of the challenges in the management of BCC, as was the case in our patient, is the treatment of tumors that arise in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas. Approaches that minimize the amount of tissue removed while ensuring the highest possible cure rate are favorable. In addition to surgery, topical imiquimod has been established as a potential treatment of BCC. Imiquimod, a nucleoside analogue of the imidazoquinoline family, is an agonist of toll-like receptors 7 and 8 that promotes cytokine-induced cell death via nuclear factor kB and a helper T cell TH1-weighted antitumor inflammatory response.5,6 Although clearance rates with imiquimod vary by drug regimen, success rates of 43% to 100% for superficial BCCs, 42% to 100% for nodular BCCs, and 56% to 63% for infiltrative BCCs have been reported.7 In a 2007 randomized study of imiquimod cream 5%, 5-FU ointment 5%, or cryosurgery for the treatment of AK, imiquimod resulted in superior and more reliable clearance with lower recurrence rates.8

Similar to BCC, AK is closely linked to lifetime cumulative sun exposure.9 Actinic keratoses have been well established as precursors to SCC, and some researchers advocate for their reclassification as early SCC in situ.10 The incidence of malignant conversion of AK to SCC has been estimated at 0.025% to 16% annually, with an estimated lifetime risk for malignant transformation of 8% per individual AK.11,12 Cryotherapy has been a mainstay for the treatment of isolated AK, and alternative therapies including curettage, photodynamic therapy, and laser therapy have been employed. Field-directed therapy has become a popular alternative that targets multiple lesions and field cancerization.8,13,14 Field cancerization implies that if one cell in the patient’s epidermis has been exposed to enough UV radiation to develop into a precancerous lesion or early skin cancer, then many other cells in the same environment likely have some degree of UV radiation–induced atypia.15 5-Fluorouacil is a pyrimidine analogue chemotherapeutic agent that inhibits thymidylate synthase and interferes with DNA synthesis.16 This mechanism of 5-FU commonly causes an inflammatory response characterized by burning, dryness, and redness, but these effects rarely force early discontinuation of treatment. A randomized controlled trial comparing 5-FU cream 0.5% to a placebo found that complete clearance rates at 4 weeks posttreatment were significantly higher in the treatment group (47.5%) versus placebo (3.4%)(P<.001).13 Additional trials have established no significant superiority of 5-FU cream 5% over 5-FU cream 0.5%, with a decrease in side effects noted in patients treated with the lower concentration.17

Our patient had a history of a recurrent BCC and was previously treated with imiquimod. He showed no inflammatory response to field therapy with 5-FU within the perimeter of prior immunomodulatory therapy. Although no frank scaling or crusting papules consistent with AK were observed in the previously treated area prior to 5-FU therapy, subclinical field damage in that area was expected because 10 years of additional sun exposure had accumulated since imiquimod therapy was completed. Several conclusions can be drawn from this observation. Primarily, no new clinically significant actinic lesions occurred on the previously treated skin. This observation is consistent with 12-month follow-up data on AKs treated with either 5-FU, imiquimod, or cryosurgery that identified imiquimod as having the lowest recurrence rate.8 Thus, a photoprotective effect may be ascribed to imiquimod therapy that extends beyond its drug effects on atypical keratinocytes. It has been one author’s personal experience (M.Q.) that patients treated with 5-FU experience recurrence of AKs within 3 to 5 years versus 10 years of remission with imiquimod. In our patient, imiquimod therapy seemed to reset the patient’s skin at the location of the prior BCC and surrounding field cancerization.

Studies with long-term follow-up are needed to investigate the need for re-treatment with imiquimod or 5-FU. The longevity of imiquimod treatment may be of importance beyond the treatment of AKs or NMSCs. For instance, during the treatment of lentigo maligna with imiquimod, Metcalf et al18 found a significant reduction in solar elastosis (P=.0036), normalization of epidermal thickness (P=.0073), and increased papillary dermal fibroplasia in pre- and posttreatment biopsies (P<.0001), which have been described as antiaging effects in the laypress. Some of these mechanisms appear to be implicated in the observations noted in our patient. The 10-year period between the 2 courses of therapy in our patient suggests that imiquimod may cause sustained healing of skin that was previously classified both clinically and microscopically as UV damaged.

Conclusion

Both topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod and topical chemotherapeutic agents such as 5-FU have a role in the field treatment of AK and the focal treatment of superficial BCC and SCC. As multiple topical immunomodulators continue to be evaluated, long-term studies assessing the need for re-treatment as well as the degree of sustained remission of sun damage will be necessary. We expect that their individual roles will continue to become more precisely defined and distinct in the coming years.

1. Flohil SC, de Vries E, Neumann HA, et al. Incidence, prevalence and future trends of primary basal cell carcinoma in the Netherlands. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:24-30.

2. Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. No end in sight: the skin cancer epidemic continues. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30:3-5.

3. Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer. I. Basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:157-163.

4. Gailani MR, Leffell DJ, Ziegler A, et al. Relationship between sunlight exposure and a key genetic alteration in basal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:349-354.

5. Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway [published online ahead of print January 22, 2002]. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196-200.

6. Schön MP, Schön M. Imiquimod: mode of action. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):8-13.

7. Love WE, Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Topical imiquimod or fluorouracil therapy for basal and squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1431-1438.

8. Krawtchenko N, Roewert-Huber J, Ulrich M, et al. A randomised study of topical 5% imiquimod vs. topical5-fluorouracil vs. cryosurgery in immunocompetent patients with actinic keratoses: a comparison of clinical and histological outcomes including 1-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):34-40.

9. Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma revisited: clinical and treatment implications. Cutis. 2011;87:201-207.

10. Röwert-Huber J, Patel MJ, Forschner T, et al. Actinic keratosis is an early in situ squamous cell carcinoma: a proposal for reclassification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(suppl 3):8-12.

11. Glogau RG. The risk of progression to invasive disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1 pt 2):23-24.

12. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

13. Weiss J, Menter A, Hevia O, et al. Effective treatment of actinic keratosis with 0.5% fluorouracil cream for 1, 2, or 4 weeks. Cutis. 2002;70(2 suppl):22-29.

14. Almeida Gonçalves JC, De Noronha T. 5-fluouracil (5-FU) ointment in the treatment of skin tumours and keratoses. Dermatologica. 1970;140(suppl 1):97+.

15. Vanharanta S, Massagué J. Field cancerization: something new under the sun. Cell. 2012;149:1179-1181.

16. Robins P, Gupta AK. The use of topical fluorouracil to treat actinic keratosis. Cutis. 2002;70(2 suppl):4-7.

17. Kaur R, Alikhan A, Maibach H. Comparison of topical 5-fluorouracil formulations in actinic keratosis treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;2:267-271.

18. Metcalf S, Crowson AN, Naylor M, et al. Imiquimod as an antiaging agent [published online ahead of print December 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:422-425.

Sun damage and chronic exposure to UV radiation have been recognized as causative factors for the development of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), its precursor actinic keratosis (AK), and basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Although surgical treatment is necessary for most advanced cases of skin cancer, several other therapeutic approaches have been described including the use of topical chemotherapy agents such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod. Unlike surgery, these agents provide the added benefit of treating larger fields of photodamaged skin. With the increasing prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), the use of multiple topical agents for treatment will continue to become more common.

We present the case of a patient who underwent field therapy with topical 5-FU for diffuse actinic damage and AKs. There was no subsequent inflammatory response within the perimeter of a BCC that had been treated with imiquimod 10 years prior.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 58-year-old man with a history of long-standing diffuse sun damage and multiple prior NMSCs presented for treatment of a recurrent BCC on the right cheek. The patient reported that the BCC had initially been biopsied and excised by his primary care physician. Two months later local recurrence was noted by the primary care physician and the patient was subsequently referred to our dermatology office. A 2-month treatment course with daily imiquimod cream 5% was initiated. This treatment caused extensive inflammation of the right cheek but was otherwise well tolerated (Figure 1).

|

During a routine skin cancer screening 10 years later, no recurrence of the BCC was noted on the right cheek; however, the patient had developed multiple AKs on the face. Therapeutic options were discussed with the patient; he agreed to topical field therapy with 5-FU cream 0.5%. The patient applied the 5-FU cream to the entire face nightly for 1 month. During this time he experienced a brisk inflammatory response with painful cracking and redness of the skin. On follow-up, it was noted that the area on the right cheek that had been treated with imiquimod 10 years prior showed no inflammatory response despite nightly application of 5-FU cream to the area (Figure 2). The patient denied any routine use of sunscreen or other sun-protective practices.

Comment

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in the United States with an incidence of 1.4% to 2% per year. It has become more prevalent in recent decades, likely due to genetic predisposition and increasing cumulative sun exposure.1-4 A variety of treatment options are available. Surgical interventions include destruction via electrodesiccation and curettage, local excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery. One of the challenges in the management of BCC, as was the case in our patient, is the treatment of tumors that arise in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas. Approaches that minimize the amount of tissue removed while ensuring the highest possible cure rate are favorable. In addition to surgery, topical imiquimod has been established as a potential treatment of BCC. Imiquimod, a nucleoside analogue of the imidazoquinoline family, is an agonist of toll-like receptors 7 and 8 that promotes cytokine-induced cell death via nuclear factor kB and a helper T cell TH1-weighted antitumor inflammatory response.5,6 Although clearance rates with imiquimod vary by drug regimen, success rates of 43% to 100% for superficial BCCs, 42% to 100% for nodular BCCs, and 56% to 63% for infiltrative BCCs have been reported.7 In a 2007 randomized study of imiquimod cream 5%, 5-FU ointment 5%, or cryosurgery for the treatment of AK, imiquimod resulted in superior and more reliable clearance with lower recurrence rates.8

Similar to BCC, AK is closely linked to lifetime cumulative sun exposure.9 Actinic keratoses have been well established as precursors to SCC, and some researchers advocate for their reclassification as early SCC in situ.10 The incidence of malignant conversion of AK to SCC has been estimated at 0.025% to 16% annually, with an estimated lifetime risk for malignant transformation of 8% per individual AK.11,12 Cryotherapy has been a mainstay for the treatment of isolated AK, and alternative therapies including curettage, photodynamic therapy, and laser therapy have been employed. Field-directed therapy has become a popular alternative that targets multiple lesions and field cancerization.8,13,14 Field cancerization implies that if one cell in the patient’s epidermis has been exposed to enough UV radiation to develop into a precancerous lesion or early skin cancer, then many other cells in the same environment likely have some degree of UV radiation–induced atypia.15 5-Fluorouacil is a pyrimidine analogue chemotherapeutic agent that inhibits thymidylate synthase and interferes with DNA synthesis.16 This mechanism of 5-FU commonly causes an inflammatory response characterized by burning, dryness, and redness, but these effects rarely force early discontinuation of treatment. A randomized controlled trial comparing 5-FU cream 0.5% to a placebo found that complete clearance rates at 4 weeks posttreatment were significantly higher in the treatment group (47.5%) versus placebo (3.4%)(P<.001).13 Additional trials have established no significant superiority of 5-FU cream 5% over 5-FU cream 0.5%, with a decrease in side effects noted in patients treated with the lower concentration.17

Our patient had a history of a recurrent BCC and was previously treated with imiquimod. He showed no inflammatory response to field therapy with 5-FU within the perimeter of prior immunomodulatory therapy. Although no frank scaling or crusting papules consistent with AK were observed in the previously treated area prior to 5-FU therapy, subclinical field damage in that area was expected because 10 years of additional sun exposure had accumulated since imiquimod therapy was completed. Several conclusions can be drawn from this observation. Primarily, no new clinically significant actinic lesions occurred on the previously treated skin. This observation is consistent with 12-month follow-up data on AKs treated with either 5-FU, imiquimod, or cryosurgery that identified imiquimod as having the lowest recurrence rate.8 Thus, a photoprotective effect may be ascribed to imiquimod therapy that extends beyond its drug effects on atypical keratinocytes. It has been one author’s personal experience (M.Q.) that patients treated with 5-FU experience recurrence of AKs within 3 to 5 years versus 10 years of remission with imiquimod. In our patient, imiquimod therapy seemed to reset the patient’s skin at the location of the prior BCC and surrounding field cancerization.

Studies with long-term follow-up are needed to investigate the need for re-treatment with imiquimod or 5-FU. The longevity of imiquimod treatment may be of importance beyond the treatment of AKs or NMSCs. For instance, during the treatment of lentigo maligna with imiquimod, Metcalf et al18 found a significant reduction in solar elastosis (P=.0036), normalization of epidermal thickness (P=.0073), and increased papillary dermal fibroplasia in pre- and posttreatment biopsies (P<.0001), which have been described as antiaging effects in the laypress. Some of these mechanisms appear to be implicated in the observations noted in our patient. The 10-year period between the 2 courses of therapy in our patient suggests that imiquimod may cause sustained healing of skin that was previously classified both clinically and microscopically as UV damaged.

Conclusion

Both topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod and topical chemotherapeutic agents such as 5-FU have a role in the field treatment of AK and the focal treatment of superficial BCC and SCC. As multiple topical immunomodulators continue to be evaluated, long-term studies assessing the need for re-treatment as well as the degree of sustained remission of sun damage will be necessary. We expect that their individual roles will continue to become more precisely defined and distinct in the coming years.

Sun damage and chronic exposure to UV radiation have been recognized as causative factors for the development of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), its precursor actinic keratosis (AK), and basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Although surgical treatment is necessary for most advanced cases of skin cancer, several other therapeutic approaches have been described including the use of topical chemotherapy agents such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod. Unlike surgery, these agents provide the added benefit of treating larger fields of photodamaged skin. With the increasing prevalence of nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), the use of multiple topical agents for treatment will continue to become more common.

We present the case of a patient who underwent field therapy with topical 5-FU for diffuse actinic damage and AKs. There was no subsequent inflammatory response within the perimeter of a BCC that had been treated with imiquimod 10 years prior.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 58-year-old man with a history of long-standing diffuse sun damage and multiple prior NMSCs presented for treatment of a recurrent BCC on the right cheek. The patient reported that the BCC had initially been biopsied and excised by his primary care physician. Two months later local recurrence was noted by the primary care physician and the patient was subsequently referred to our dermatology office. A 2-month treatment course with daily imiquimod cream 5% was initiated. This treatment caused extensive inflammation of the right cheek but was otherwise well tolerated (Figure 1).

|

During a routine skin cancer screening 10 years later, no recurrence of the BCC was noted on the right cheek; however, the patient had developed multiple AKs on the face. Therapeutic options were discussed with the patient; he agreed to topical field therapy with 5-FU cream 0.5%. The patient applied the 5-FU cream to the entire face nightly for 1 month. During this time he experienced a brisk inflammatory response with painful cracking and redness of the skin. On follow-up, it was noted that the area on the right cheek that had been treated with imiquimod 10 years prior showed no inflammatory response despite nightly application of 5-FU cream to the area (Figure 2). The patient denied any routine use of sunscreen or other sun-protective practices.

Comment

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer in the United States with an incidence of 1.4% to 2% per year. It has become more prevalent in recent decades, likely due to genetic predisposition and increasing cumulative sun exposure.1-4 A variety of treatment options are available. Surgical interventions include destruction via electrodesiccation and curettage, local excision, and Mohs micrographic surgery. One of the challenges in the management of BCC, as was the case in our patient, is the treatment of tumors that arise in cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas. Approaches that minimize the amount of tissue removed while ensuring the highest possible cure rate are favorable. In addition to surgery, topical imiquimod has been established as a potential treatment of BCC. Imiquimod, a nucleoside analogue of the imidazoquinoline family, is an agonist of toll-like receptors 7 and 8 that promotes cytokine-induced cell death via nuclear factor kB and a helper T cell TH1-weighted antitumor inflammatory response.5,6 Although clearance rates with imiquimod vary by drug regimen, success rates of 43% to 100% for superficial BCCs, 42% to 100% for nodular BCCs, and 56% to 63% for infiltrative BCCs have been reported.7 In a 2007 randomized study of imiquimod cream 5%, 5-FU ointment 5%, or cryosurgery for the treatment of AK, imiquimod resulted in superior and more reliable clearance with lower recurrence rates.8

Similar to BCC, AK is closely linked to lifetime cumulative sun exposure.9 Actinic keratoses have been well established as precursors to SCC, and some researchers advocate for their reclassification as early SCC in situ.10 The incidence of malignant conversion of AK to SCC has been estimated at 0.025% to 16% annually, with an estimated lifetime risk for malignant transformation of 8% per individual AK.11,12 Cryotherapy has been a mainstay for the treatment of isolated AK, and alternative therapies including curettage, photodynamic therapy, and laser therapy have been employed. Field-directed therapy has become a popular alternative that targets multiple lesions and field cancerization.8,13,14 Field cancerization implies that if one cell in the patient’s epidermis has been exposed to enough UV radiation to develop into a precancerous lesion or early skin cancer, then many other cells in the same environment likely have some degree of UV radiation–induced atypia.15 5-Fluorouacil is a pyrimidine analogue chemotherapeutic agent that inhibits thymidylate synthase and interferes with DNA synthesis.16 This mechanism of 5-FU commonly causes an inflammatory response characterized by burning, dryness, and redness, but these effects rarely force early discontinuation of treatment. A randomized controlled trial comparing 5-FU cream 0.5% to a placebo found that complete clearance rates at 4 weeks posttreatment were significantly higher in the treatment group (47.5%) versus placebo (3.4%)(P<.001).13 Additional trials have established no significant superiority of 5-FU cream 5% over 5-FU cream 0.5%, with a decrease in side effects noted in patients treated with the lower concentration.17

Our patient had a history of a recurrent BCC and was previously treated with imiquimod. He showed no inflammatory response to field therapy with 5-FU within the perimeter of prior immunomodulatory therapy. Although no frank scaling or crusting papules consistent with AK were observed in the previously treated area prior to 5-FU therapy, subclinical field damage in that area was expected because 10 years of additional sun exposure had accumulated since imiquimod therapy was completed. Several conclusions can be drawn from this observation. Primarily, no new clinically significant actinic lesions occurred on the previously treated skin. This observation is consistent with 12-month follow-up data on AKs treated with either 5-FU, imiquimod, or cryosurgery that identified imiquimod as having the lowest recurrence rate.8 Thus, a photoprotective effect may be ascribed to imiquimod therapy that extends beyond its drug effects on atypical keratinocytes. It has been one author’s personal experience (M.Q.) that patients treated with 5-FU experience recurrence of AKs within 3 to 5 years versus 10 years of remission with imiquimod. In our patient, imiquimod therapy seemed to reset the patient’s skin at the location of the prior BCC and surrounding field cancerization.

Studies with long-term follow-up are needed to investigate the need for re-treatment with imiquimod or 5-FU. The longevity of imiquimod treatment may be of importance beyond the treatment of AKs or NMSCs. For instance, during the treatment of lentigo maligna with imiquimod, Metcalf et al18 found a significant reduction in solar elastosis (P=.0036), normalization of epidermal thickness (P=.0073), and increased papillary dermal fibroplasia in pre- and posttreatment biopsies (P<.0001), which have been described as antiaging effects in the laypress. Some of these mechanisms appear to be implicated in the observations noted in our patient. The 10-year period between the 2 courses of therapy in our patient suggests that imiquimod may cause sustained healing of skin that was previously classified both clinically and microscopically as UV damaged.

Conclusion

Both topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod and topical chemotherapeutic agents such as 5-FU have a role in the field treatment of AK and the focal treatment of superficial BCC and SCC. As multiple topical immunomodulators continue to be evaluated, long-term studies assessing the need for re-treatment as well as the degree of sustained remission of sun damage will be necessary. We expect that their individual roles will continue to become more precisely defined and distinct in the coming years.

1. Flohil SC, de Vries E, Neumann HA, et al. Incidence, prevalence and future trends of primary basal cell carcinoma in the Netherlands. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:24-30.

2. Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. No end in sight: the skin cancer epidemic continues. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30:3-5.

3. Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer. I. Basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:157-163.

4. Gailani MR, Leffell DJ, Ziegler A, et al. Relationship between sunlight exposure and a key genetic alteration in basal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:349-354.

5. Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway [published online ahead of print January 22, 2002]. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196-200.

6. Schön MP, Schön M. Imiquimod: mode of action. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):8-13.

7. Love WE, Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Topical imiquimod or fluorouracil therapy for basal and squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1431-1438.

8. Krawtchenko N, Roewert-Huber J, Ulrich M, et al. A randomised study of topical 5% imiquimod vs. topical5-fluorouracil vs. cryosurgery in immunocompetent patients with actinic keratoses: a comparison of clinical and histological outcomes including 1-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):34-40.

9. Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma revisited: clinical and treatment implications. Cutis. 2011;87:201-207.

10. Röwert-Huber J, Patel MJ, Forschner T, et al. Actinic keratosis is an early in situ squamous cell carcinoma: a proposal for reclassification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(suppl 3):8-12.

11. Glogau RG. The risk of progression to invasive disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1 pt 2):23-24.

12. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

13. Weiss J, Menter A, Hevia O, et al. Effective treatment of actinic keratosis with 0.5% fluorouracil cream for 1, 2, or 4 weeks. Cutis. 2002;70(2 suppl):22-29.

14. Almeida Gonçalves JC, De Noronha T. 5-fluouracil (5-FU) ointment in the treatment of skin tumours and keratoses. Dermatologica. 1970;140(suppl 1):97+.

15. Vanharanta S, Massagué J. Field cancerization: something new under the sun. Cell. 2012;149:1179-1181.

16. Robins P, Gupta AK. The use of topical fluorouracil to treat actinic keratosis. Cutis. 2002;70(2 suppl):4-7.

17. Kaur R, Alikhan A, Maibach H. Comparison of topical 5-fluorouracil formulations in actinic keratosis treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;2:267-271.

18. Metcalf S, Crowson AN, Naylor M, et al. Imiquimod as an antiaging agent [published online ahead of print December 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:422-425.

1. Flohil SC, de Vries E, Neumann HA, et al. Incidence, prevalence and future trends of primary basal cell carcinoma in the Netherlands. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:24-30.

2. Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. No end in sight: the skin cancer epidemic continues. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30:3-5.

3. Gallagher RP, Hill GB, Bajdik CD, et al. Sunlight exposure, pigmentary factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer. I. Basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:157-163.

4. Gailani MR, Leffell DJ, Ziegler A, et al. Relationship between sunlight exposure and a key genetic alteration in basal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:349-354.

5. Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway [published online ahead of print January 22, 2002]. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196-200.

6. Schön MP, Schön M. Imiquimod: mode of action. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):8-13.

7. Love WE, Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Topical imiquimod or fluorouracil therapy for basal and squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1431-1438.

8. Krawtchenko N, Roewert-Huber J, Ulrich M, et al. A randomised study of topical 5% imiquimod vs. topical5-fluorouracil vs. cryosurgery in immunocompetent patients with actinic keratoses: a comparison of clinical and histological outcomes including 1-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):34-40.

9. Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. Progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma revisited: clinical and treatment implications. Cutis. 2011;87:201-207.

10. Röwert-Huber J, Patel MJ, Forschner T, et al. Actinic keratosis is an early in situ squamous cell carcinoma: a proposal for reclassification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(suppl 3):8-12.

11. Glogau RG. The risk of progression to invasive disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1 pt 2):23-24.

12. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

13. Weiss J, Menter A, Hevia O, et al. Effective treatment of actinic keratosis with 0.5% fluorouracil cream for 1, 2, or 4 weeks. Cutis. 2002;70(2 suppl):22-29.

14. Almeida Gonçalves JC, De Noronha T. 5-fluouracil (5-FU) ointment in the treatment of skin tumours and keratoses. Dermatologica. 1970;140(suppl 1):97+.

15. Vanharanta S, Massagué J. Field cancerization: something new under the sun. Cell. 2012;149:1179-1181.

16. Robins P, Gupta AK. The use of topical fluorouracil to treat actinic keratosis. Cutis. 2002;70(2 suppl):4-7.

17. Kaur R, Alikhan A, Maibach H. Comparison of topical 5-fluorouracil formulations in actinic keratosis treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;2:267-271.

18. Metcalf S, Crowson AN, Naylor M, et al. Imiquimod as an antiaging agent [published online ahead of print December 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:422-425.

Practice Points

- Topical immunomodulators such as imiquimod and topical chemotherapeutics such as 5-fluorouracil are effective in the field treatment of actinic keratoses.

- Prior topical immunomodulator use for nonmelanoma skin cancer may induce a sustained remission of actinic damage.

- The field effect of imiquimod treatment in actinically damaged skin may persist for several years.

Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma and Other Slow-Growing Tumors in Acral Areas

First described by Fetsch et al1 in 2001, superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) is a rare fibromyxoid mesenchymal tumor that typically affects the fingers and toes with frequent involvement of the nail unit. It is not widely recognized and remains poorly understood. We describe a series of 3 cases of SAFM encountered at our institution and provide a review of the literature on this unique tumor.

Case Reports

Patient 1

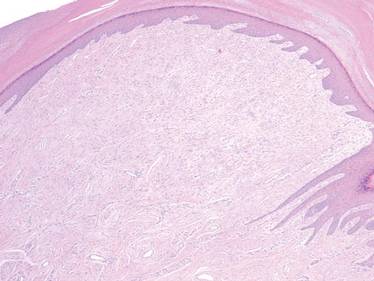

A 35-year-old man presented for treatment of a “wart” on the right fifth toe that had increased in size over the last year. He reported that the lesion was mildly painful and occasionally bled or drained clear fluid. He also noted cracking of the nail plate on the same toe. Physical examination revealed a firm, flesh-colored, 3-mm dermal papule on the proximal nail fold of the right fifth toe with subtle flattening of the underlying nail plate (Figure 1). The patient underwent biopsy of the involved proximal nail fold. Histopathology revealed a proliferation of small oval and spindle cells arranged in fascicles and bundles in the dermis (Figure 2). There was extensive mucin deposition associated with the spindle cell proliferation. Additionally, spindle cells and mucin surrounded and entrapped collagen bundles on the periphery of the lesion. Lesional cells were diffusely positive for CD34 and extended to the deep surgical margin (Figure 3). S-100 and factor XIIIa stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

|

Patient 2

A 47-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic growth on the left fourth toe that had increased in size over the last year. Physical examination revealed an 8-mm, firm, fleshy, flesh-colored, smooth and slightly pedunculated papule on the distal aspect of the left fourth toe. The nail plate and periungual region were not involved. A shave biopsy of the papule was obtained. Histopathology demonstrated dermal stellate spindle cells arranged in a loose fascicular pattern with marked mucin deposition throughout the dermis (Figure 4). Lesional cells were positive for CD34. An S-100 stain highlighted dermal dendritic cells, but lesional cells were negative. No further excision was undertaken, and there was no evidence of recurrence at 1-year follow-up. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Patient 3

A 45-year-old woman presented with asymptomatic distal onycholysis of the right thumbnail of 1 year’s duration. She denied any history of trauma, and no bleeding or pigmentary changes were noted. Physical examination revealed a 5-mm flesh-colored papule on the hyponychium of the right thumb with focal onycholysis (Figure 5). A wedge biopsy of the lesion was performed. Histopathology showed an intradermal nodular proliferation of bland spindle cells arranged in loose fascicles and bundles and embedded in a myxoid stroma (Figure 6). CD34 staining strongly highlighted lesional cells. S-100 and neurofilament stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Comment

Clinically, SAFM typically presents as a slow-growing solitary nodule on the distal fingers or toes. The great toe is the most commonly affected digit, and the tumor may be subungual in up to two-thirds of cases.1 Unusual locations, such as the heel, also have been reported.2 Onset typically occurs in the fifth or sixth decade, and there is an approximately 2-fold higher incidence in men than women.1-3

Histopathologically, SAFM is a characteristically well-circumscribed but unencapsulated dermal tumor composed of spindle and stellate cells in a loose storiform or fascicular arrangement embedded in a myxoid, myxocollagenous, or collagenous stroma.4 The tumor often occupies the entire dermis and may extend into the subcutis or occasionally the underlying fascia and bone.4,5 Mast cells often are prominent, and microvascular accentuation also may be seen. Inflammatory infiltrates and multinucleated giant cells typically are not seen.6 Although 2 cases of atypical SAFM have been described,2 cellular atypia is not a characteristic feature of SAFM.

The immunohistochemical profile of SAFM is characterized by diffuse or focal expression of CD34, focal expression of epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD99 expression, and varying numbers of factor XIIIa–positive histiocytes.2,3 Positive staining for vimentin also is common. Staining typically is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, keratin, smooth muscle actin, and desmin.

The standard treatment of SAFM is complete local resection of the tumor, though some patients have been treated with partial excision or biopsy and partial or complete digital amputation.1 Local recurrence may occur in up to 20% of cases; however, approximately two-thirds of the reported recurrences in the literature occurred after incomplete tumor excision.1,2 It may be more appropriate to consider these cases as persistent rather than recurrent tumors. Superficial acral fibromyxoma is considered a benign tumor, with no known cases of metastases.4

|

A broad differential diagnosis exists for SAFM and it can be difficult to differentiate it from a wide variety of benign and malignant tumors that may be seen on the nail unit and distal extremities (Table). Myxoid neurofibromas typically present as solitary lesions on the hands and feet. Similar to SAFM, myxoid neurofibromas are unencapsulated dermal tumors composed of spindle-shaped cells in which mast cells often are conspicuous.2,7 However, tumor cells in myxoid neurofibromas are S-100 positive, and the lesions typically do not show vasculature accentuation.4,7

Sclerosing perineuriomas are benign fibrous tumors of the fingers and palms. Histopathologically, bland spindle cells arranged in fascicles and whorls are observed in a hyalinized collagen matrix.8 Immunohistochemically, sclerosing perineuriomas are positive for EMA and negative for S-100, but unlike SAFM, these tumors usually are CD34 negative.8

Superficial angiomyxomas typically are located on the head and neck but also may be found in other locations such as the trunk. They present as cutaneous papules or polypoid lesions. Histopathologically, superficial angiomyxomas are poorly circumscribed with a lobular pattern. Spindle-shaped fibroblasts exist in a myxoid matrix with neutrophils and thin-walled capillaries. The fibroblasts are variably positive for CD34 but also are S-100 positive.1,9

Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, locally aggressive, mesenchymal tumor of the skin and subcutis2 that typically presents on the trunk, proximal extremities, or head and neck; occurrence on the fingers or toes is exceedingly rare.2,10 Histopathologically, a myxoid stroma contains sheets of bland spindle-shaped cells with minimal to no atypia, sometimes arranged in a storiform pattern. The tumor characteristically invades deeply into the subcutaneous tissues. CD34 is characteristically positive and S-100 is negative.2,10

Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma is a soft tissue sarcoma easily confused with other spindle cell tumors. It is one of the most common sarcomas in adults but rarely arises in acral areas.2 It is characterized by a nodular growth pattern with marked nuclear atypia and perivascular clustering of tumor cells. CD34 staining may be positive in some cases.11

Similar to SAFM, myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma has a predilection for the extremities.4 However, it typically presents as a subcutaneous mass and has no documented tendency for nail bed involvement. Also unlike SAFM, it has a remarkable inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic virocyte or Reed-Sternberg cells.12

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas are benign neoplasms that occur on fingers and toes; the classic clinical presentation is a solitary smooth nodule or dome, often with a characteristic projecting configuration and horn shape.1 Histopathologically, these tumors are paucicellular with thick, vertically oriented, interwoven collagen bundles; cells may be positive for CD34 but are negative for EMA.1,13 Related to acquired digital fibrokeratomas are Koenen tumors, which share a similar histology but are distinguished by their clinical characteristics. For example, Koenen tumors tend to be multifocal and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis. These tumors also have a tendency to recur.1

Conclusion

Our report of 3 typical cases of SAFM highlights the need to keep this increasingly recognized and well-defined clinicopathological entity in the differential for slow-growing tumors in acral locations, particularly those in the periungual and subungual regions.

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Al-Daraji WI, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 32 tumors including 4 in the heel. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1020-1026.

3. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

4. André J, Theunis A, Richert B, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: clinical and pathological features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:472-474.

5. Kazakov DV, Mentzel T, Burg G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2002;205:285-288.

6. Meyerle JH, Keller RA, Krivda SJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the index finger. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:134-136.

7. Graadt van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PC, Fletcher CD. Myxoid tumours of soft tissue. Histopathology. 1999;35:291-312.

8. Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

9. Calonje E, Guerin D, McCormick D, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series of distinctive but poorly recognized cutaneous tumors with tendency for recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:910-917.

10. Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

11. Wada T, Hasegawa T, Nagoya S, et al. Myxofibrosarcoma with an infiltrative growth pattern: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30:458-462.

12. Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: a low-grade tumor of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:911-924.

13. Bart RS, Andrade R, Kopf AW, et al. Acquired digital fibrokeratomas. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:120-129.

First described by Fetsch et al1 in 2001, superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) is a rare fibromyxoid mesenchymal tumor that typically affects the fingers and toes with frequent involvement of the nail unit. It is not widely recognized and remains poorly understood. We describe a series of 3 cases of SAFM encountered at our institution and provide a review of the literature on this unique tumor.

Case Reports

Patient 1

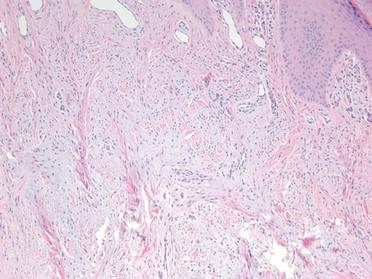

A 35-year-old man presented for treatment of a “wart” on the right fifth toe that had increased in size over the last year. He reported that the lesion was mildly painful and occasionally bled or drained clear fluid. He also noted cracking of the nail plate on the same toe. Physical examination revealed a firm, flesh-colored, 3-mm dermal papule on the proximal nail fold of the right fifth toe with subtle flattening of the underlying nail plate (Figure 1). The patient underwent biopsy of the involved proximal nail fold. Histopathology revealed a proliferation of small oval and spindle cells arranged in fascicles and bundles in the dermis (Figure 2). There was extensive mucin deposition associated with the spindle cell proliferation. Additionally, spindle cells and mucin surrounded and entrapped collagen bundles on the periphery of the lesion. Lesional cells were diffusely positive for CD34 and extended to the deep surgical margin (Figure 3). S-100 and factor XIIIa stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

|

Patient 2

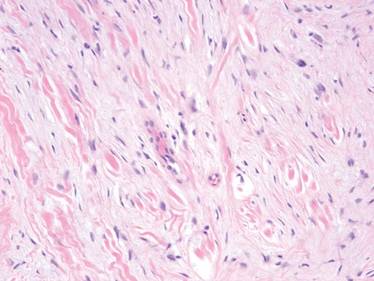

A 47-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic growth on the left fourth toe that had increased in size over the last year. Physical examination revealed an 8-mm, firm, fleshy, flesh-colored, smooth and slightly pedunculated papule on the distal aspect of the left fourth toe. The nail plate and periungual region were not involved. A shave biopsy of the papule was obtained. Histopathology demonstrated dermal stellate spindle cells arranged in a loose fascicular pattern with marked mucin deposition throughout the dermis (Figure 4). Lesional cells were positive for CD34. An S-100 stain highlighted dermal dendritic cells, but lesional cells were negative. No further excision was undertaken, and there was no evidence of recurrence at 1-year follow-up. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Patient 3

A 45-year-old woman presented with asymptomatic distal onycholysis of the right thumbnail of 1 year’s duration. She denied any history of trauma, and no bleeding or pigmentary changes were noted. Physical examination revealed a 5-mm flesh-colored papule on the hyponychium of the right thumb with focal onycholysis (Figure 5). A wedge biopsy of the lesion was performed. Histopathology showed an intradermal nodular proliferation of bland spindle cells arranged in loose fascicles and bundles and embedded in a myxoid stroma (Figure 6). CD34 staining strongly highlighted lesional cells. S-100 and neurofilament stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Comment

Clinically, SAFM typically presents as a slow-growing solitary nodule on the distal fingers or toes. The great toe is the most commonly affected digit, and the tumor may be subungual in up to two-thirds of cases.1 Unusual locations, such as the heel, also have been reported.2 Onset typically occurs in the fifth or sixth decade, and there is an approximately 2-fold higher incidence in men than women.1-3

Histopathologically, SAFM is a characteristically well-circumscribed but unencapsulated dermal tumor composed of spindle and stellate cells in a loose storiform or fascicular arrangement embedded in a myxoid, myxocollagenous, or collagenous stroma.4 The tumor often occupies the entire dermis and may extend into the subcutis or occasionally the underlying fascia and bone.4,5 Mast cells often are prominent, and microvascular accentuation also may be seen. Inflammatory infiltrates and multinucleated giant cells typically are not seen.6 Although 2 cases of atypical SAFM have been described,2 cellular atypia is not a characteristic feature of SAFM.

The immunohistochemical profile of SAFM is characterized by diffuse or focal expression of CD34, focal expression of epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD99 expression, and varying numbers of factor XIIIa–positive histiocytes.2,3 Positive staining for vimentin also is common. Staining typically is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, keratin, smooth muscle actin, and desmin.

The standard treatment of SAFM is complete local resection of the tumor, though some patients have been treated with partial excision or biopsy and partial or complete digital amputation.1 Local recurrence may occur in up to 20% of cases; however, approximately two-thirds of the reported recurrences in the literature occurred after incomplete tumor excision.1,2 It may be more appropriate to consider these cases as persistent rather than recurrent tumors. Superficial acral fibromyxoma is considered a benign tumor, with no known cases of metastases.4

|

A broad differential diagnosis exists for SAFM and it can be difficult to differentiate it from a wide variety of benign and malignant tumors that may be seen on the nail unit and distal extremities (Table). Myxoid neurofibromas typically present as solitary lesions on the hands and feet. Similar to SAFM, myxoid neurofibromas are unencapsulated dermal tumors composed of spindle-shaped cells in which mast cells often are conspicuous.2,7 However, tumor cells in myxoid neurofibromas are S-100 positive, and the lesions typically do not show vasculature accentuation.4,7

Sclerosing perineuriomas are benign fibrous tumors of the fingers and palms. Histopathologically, bland spindle cells arranged in fascicles and whorls are observed in a hyalinized collagen matrix.8 Immunohistochemically, sclerosing perineuriomas are positive for EMA and negative for S-100, but unlike SAFM, these tumors usually are CD34 negative.8

Superficial angiomyxomas typically are located on the head and neck but also may be found in other locations such as the trunk. They present as cutaneous papules or polypoid lesions. Histopathologically, superficial angiomyxomas are poorly circumscribed with a lobular pattern. Spindle-shaped fibroblasts exist in a myxoid matrix with neutrophils and thin-walled capillaries. The fibroblasts are variably positive for CD34 but also are S-100 positive.1,9

Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, locally aggressive, mesenchymal tumor of the skin and subcutis2 that typically presents on the trunk, proximal extremities, or head and neck; occurrence on the fingers or toes is exceedingly rare.2,10 Histopathologically, a myxoid stroma contains sheets of bland spindle-shaped cells with minimal to no atypia, sometimes arranged in a storiform pattern. The tumor characteristically invades deeply into the subcutaneous tissues. CD34 is characteristically positive and S-100 is negative.2,10

Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma is a soft tissue sarcoma easily confused with other spindle cell tumors. It is one of the most common sarcomas in adults but rarely arises in acral areas.2 It is characterized by a nodular growth pattern with marked nuclear atypia and perivascular clustering of tumor cells. CD34 staining may be positive in some cases.11

Similar to SAFM, myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma has a predilection for the extremities.4 However, it typically presents as a subcutaneous mass and has no documented tendency for nail bed involvement. Also unlike SAFM, it has a remarkable inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic virocyte or Reed-Sternberg cells.12

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas are benign neoplasms that occur on fingers and toes; the classic clinical presentation is a solitary smooth nodule or dome, often with a characteristic projecting configuration and horn shape.1 Histopathologically, these tumors are paucicellular with thick, vertically oriented, interwoven collagen bundles; cells may be positive for CD34 but are negative for EMA.1,13 Related to acquired digital fibrokeratomas are Koenen tumors, which share a similar histology but are distinguished by their clinical characteristics. For example, Koenen tumors tend to be multifocal and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis. These tumors also have a tendency to recur.1

Conclusion

Our report of 3 typical cases of SAFM highlights the need to keep this increasingly recognized and well-defined clinicopathological entity in the differential for slow-growing tumors in acral locations, particularly those in the periungual and subungual regions.

First described by Fetsch et al1 in 2001, superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) is a rare fibromyxoid mesenchymal tumor that typically affects the fingers and toes with frequent involvement of the nail unit. It is not widely recognized and remains poorly understood. We describe a series of 3 cases of SAFM encountered at our institution and provide a review of the literature on this unique tumor.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 35-year-old man presented for treatment of a “wart” on the right fifth toe that had increased in size over the last year. He reported that the lesion was mildly painful and occasionally bled or drained clear fluid. He also noted cracking of the nail plate on the same toe. Physical examination revealed a firm, flesh-colored, 3-mm dermal papule on the proximal nail fold of the right fifth toe with subtle flattening of the underlying nail plate (Figure 1). The patient underwent biopsy of the involved proximal nail fold. Histopathology revealed a proliferation of small oval and spindle cells arranged in fascicles and bundles in the dermis (Figure 2). There was extensive mucin deposition associated with the spindle cell proliferation. Additionally, spindle cells and mucin surrounded and entrapped collagen bundles on the periphery of the lesion. Lesional cells were diffusely positive for CD34 and extended to the deep surgical margin (Figure 3). S-100 and factor XIIIa stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

|

Patient 2

A 47-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic growth on the left fourth toe that had increased in size over the last year. Physical examination revealed an 8-mm, firm, fleshy, flesh-colored, smooth and slightly pedunculated papule on the distal aspect of the left fourth toe. The nail plate and periungual region were not involved. A shave biopsy of the papule was obtained. Histopathology demonstrated dermal stellate spindle cells arranged in a loose fascicular pattern with marked mucin deposition throughout the dermis (Figure 4). Lesional cells were positive for CD34. An S-100 stain highlighted dermal dendritic cells, but lesional cells were negative. No further excision was undertaken, and there was no evidence of recurrence at 1-year follow-up. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Patient 3

A 45-year-old woman presented with asymptomatic distal onycholysis of the right thumbnail of 1 year’s duration. She denied any history of trauma, and no bleeding or pigmentary changes were noted. Physical examination revealed a 5-mm flesh-colored papule on the hyponychium of the right thumb with focal onycholysis (Figure 5). A wedge biopsy of the lesion was performed. Histopathology showed an intradermal nodular proliferation of bland spindle cells arranged in loose fascicles and bundles and embedded in a myxoid stroma (Figure 6). CD34 staining strongly highlighted lesional cells. S-100 and neurofilament stains were negative. The diagnosis of SAFM was made based on the acral location, histopathologic appearance, and immunohistochemical profile of the tumor.

Comment

Clinically, SAFM typically presents as a slow-growing solitary nodule on the distal fingers or toes. The great toe is the most commonly affected digit, and the tumor may be subungual in up to two-thirds of cases.1 Unusual locations, such as the heel, also have been reported.2 Onset typically occurs in the fifth or sixth decade, and there is an approximately 2-fold higher incidence in men than women.1-3

Histopathologically, SAFM is a characteristically well-circumscribed but unencapsulated dermal tumor composed of spindle and stellate cells in a loose storiform or fascicular arrangement embedded in a myxoid, myxocollagenous, or collagenous stroma.4 The tumor often occupies the entire dermis and may extend into the subcutis or occasionally the underlying fascia and bone.4,5 Mast cells often are prominent, and microvascular accentuation also may be seen. Inflammatory infiltrates and multinucleated giant cells typically are not seen.6 Although 2 cases of atypical SAFM have been described,2 cellular atypia is not a characteristic feature of SAFM.

The immunohistochemical profile of SAFM is characterized by diffuse or focal expression of CD34, focal expression of epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD99 expression, and varying numbers of factor XIIIa–positive histiocytes.2,3 Positive staining for vimentin also is common. Staining typically is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, keratin, smooth muscle actin, and desmin.

The standard treatment of SAFM is complete local resection of the tumor, though some patients have been treated with partial excision or biopsy and partial or complete digital amputation.1 Local recurrence may occur in up to 20% of cases; however, approximately two-thirds of the reported recurrences in the literature occurred after incomplete tumor excision.1,2 It may be more appropriate to consider these cases as persistent rather than recurrent tumors. Superficial acral fibromyxoma is considered a benign tumor, with no known cases of metastases.4

|

A broad differential diagnosis exists for SAFM and it can be difficult to differentiate it from a wide variety of benign and malignant tumors that may be seen on the nail unit and distal extremities (Table). Myxoid neurofibromas typically present as solitary lesions on the hands and feet. Similar to SAFM, myxoid neurofibromas are unencapsulated dermal tumors composed of spindle-shaped cells in which mast cells often are conspicuous.2,7 However, tumor cells in myxoid neurofibromas are S-100 positive, and the lesions typically do not show vasculature accentuation.4,7

Sclerosing perineuriomas are benign fibrous tumors of the fingers and palms. Histopathologically, bland spindle cells arranged in fascicles and whorls are observed in a hyalinized collagen matrix.8 Immunohistochemically, sclerosing perineuriomas are positive for EMA and negative for S-100, but unlike SAFM, these tumors usually are CD34 negative.8

Superficial angiomyxomas typically are located on the head and neck but also may be found in other locations such as the trunk. They present as cutaneous papules or polypoid lesions. Histopathologically, superficial angiomyxomas are poorly circumscribed with a lobular pattern. Spindle-shaped fibroblasts exist in a myxoid matrix with neutrophils and thin-walled capillaries. The fibroblasts are variably positive for CD34 but also are S-100 positive.1,9

Myxoid dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, locally aggressive, mesenchymal tumor of the skin and subcutis2 that typically presents on the trunk, proximal extremities, or head and neck; occurrence on the fingers or toes is exceedingly rare.2,10 Histopathologically, a myxoid stroma contains sheets of bland spindle-shaped cells with minimal to no atypia, sometimes arranged in a storiform pattern. The tumor characteristically invades deeply into the subcutaneous tissues. CD34 is characteristically positive and S-100 is negative.2,10

Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma is a soft tissue sarcoma easily confused with other spindle cell tumors. It is one of the most common sarcomas in adults but rarely arises in acral areas.2 It is characterized by a nodular growth pattern with marked nuclear atypia and perivascular clustering of tumor cells. CD34 staining may be positive in some cases.11

Similar to SAFM, myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma has a predilection for the extremities.4 However, it typically presents as a subcutaneous mass and has no documented tendency for nail bed involvement. Also unlike SAFM, it has a remarkable inflammatory infiltrate and characteristic virocyte or Reed-Sternberg cells.12

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas are benign neoplasms that occur on fingers and toes; the classic clinical presentation is a solitary smooth nodule or dome, often with a characteristic projecting configuration and horn shape.1 Histopathologically, these tumors are paucicellular with thick, vertically oriented, interwoven collagen bundles; cells may be positive for CD34 but are negative for EMA.1,13 Related to acquired digital fibrokeratomas are Koenen tumors, which share a similar histology but are distinguished by their clinical characteristics. For example, Koenen tumors tend to be multifocal and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis. These tumors also have a tendency to recur.1

Conclusion

Our report of 3 typical cases of SAFM highlights the need to keep this increasingly recognized and well-defined clinicopathological entity in the differential for slow-growing tumors in acral locations, particularly those in the periungual and subungual regions.

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Al-Daraji WI, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 32 tumors including 4 in the heel. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1020-1026.

3. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

4. André J, Theunis A, Richert B, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: clinical and pathological features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:472-474.

5. Kazakov DV, Mentzel T, Burg G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2002;205:285-288.

6. Meyerle JH, Keller RA, Krivda SJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the index finger. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:134-136.

7. Graadt van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PC, Fletcher CD. Myxoid tumours of soft tissue. Histopathology. 1999;35:291-312.

8. Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

9. Calonje E, Guerin D, McCormick D, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series of distinctive but poorly recognized cutaneous tumors with tendency for recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:910-917.

10. Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

11. Wada T, Hasegawa T, Nagoya S, et al. Myxofibrosarcoma with an infiltrative growth pattern: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30:458-462.

12. Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: a low-grade tumor of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:911-924.

13. Bart RS, Andrade R, Kopf AW, et al. Acquired digital fibrokeratomas. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:120-129.

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Al-Daraji WI, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a clinicopathological analysis of 32 tumors including 4 in the heel. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1020-1026.

3. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

4. André J, Theunis A, Richert B, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: clinical and pathological features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:472-474.

5. Kazakov DV, Mentzel T, Burg G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2002;205:285-288.

6. Meyerle JH, Keller RA, Krivda SJ. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the index finger. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:134-136.

7. Graadt van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PC, Fletcher CD. Myxoid tumours of soft tissue. Histopathology. 1999;35:291-312.

8. Fetsch JF, Miettinen M. Sclerosing perineurioma: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases of a distinctive soft tissue lesion with a predilection for the fingers and palms of young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1433-1442.

9. Calonje E, Guerin D, McCormick D, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma: clinicopathologic analysis of a series of distinctive but poorly recognized cutaneous tumors with tendency for recurrence. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:910-917.

10. Taylor HB, Helwig EB. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. a study of 115 cases. Cancer. 1962;15:717-725.

11. Wada T, Hasegawa T, Nagoya S, et al. Myxofibrosarcoma with an infiltrative growth pattern: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2000;30:458-462.

12. Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG. Acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma: a low-grade tumor of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:911-924.

13. Bart RS, Andrade R, Kopf AW, et al. Acquired digital fibrokeratomas. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:120-129.

Practice Points

- Superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAFM) is a rare but distinct tumor that may affect the nail bed and nail plate, and it may clinically or histopathologically mimic other tumors of the distal extremities.

- Although SAFM is considered a benign tumor, it frequently persists or recurs after incomplete excision, and therefore complete local resection may be recommended, particularly for symptomatic lesions.

Sharp, left-sided back pain • bilateral leg weakness • degenerative disc disease • Dx?

THE CASE

An 84-year old woman came to the emergency department (ED) with sharp back pain on her left side that she’d had for 4 days. The pain radiated to her posterior hips when standing. She said her whole body felt achy and she was experiencing weakness in both legs.

The patient had a history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, and aortic stenosis; she’d received a bioprosthetic aortic valve 7 years ago. She was not immunocompromised or receiving steroids but was taking docusate, oxybutynin, carvedilol, amlodipine, atorvastatin, furosemide, rivaroxaban, and a multivitamin. Her physical exam, vital signs, and complete blood count (CBC) were normal. An x-ray of the lumbar spine showed degenerative joint/disc disease and spondylosis at L4-L5 and L5-S1. The patient was sent home with oxycodone/acetaminophen 5 mg/325 mg every 6 hours as needed for pain and told to follow up with her family physician (FP).

Six days later, the patient went to see her FP and told her that her symptoms hadn’t improved. She was afebrile and her blood pressure was 150/80 mm Hg. Her muscle strength was 4/5 with hip flexion bilaterally; the rest of her strength was 5/5. There was no lumbar paraspinal tenderness and she had a negative straight leg raise test. No other neurologic deficits were noted. The FP prescribed physical therapy at home with a licensed therapist, which consisted of stretching exercises and active, dynamic exercise to improve the patient’s range of motion. She also ordered outpatient lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

THE DIAGNOSIS

Approximately 3 weeks later, the patient’s MRI revealed osteomyelitis/discitis at the L3-L4 level and severe tricompartmental stenosis from L2-L3 through L4-L5. A day after receiving the results—and about a month after having first gone to the ED—the patient was admitted to the hospital. She was afebrile and her blood pressure was 148/75 mm Hg. Her physical exam revealed no leukocytosis or neurologic deficits, but did show a systolic murmur from her aortic valve.

She had an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 77 mm/hr (normal range for women, <30 mm/hr) and her C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 5.88 mg/dL (<.50 mg/dL indicates average risk for cardiovascular disease). A transesophageal echocardiogram was performed and there was no sign of vegetation or thrombi. However, blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus salivarius—a bacterium found on human dental plaque—which we determined was the cause of the osteomyelitis.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no other case reports that described S. salivarius as having caused osteomyelitis without concurrent endocarditis.

DISCUSSION

Back pain is a common and costly issue among primary care patients. More than two-thirds of adults suffer from low back pain at some point, primarily without underlying malignancy or neurologic deficits.1,2 Acute low back pain is often mechanical (97%); however, other causes, including infection, may be to blame (TABLE).1 Most acute back pain will improve with conservative treatment and patients need only reassurance of a favorable prognosis, but 20% of patients may develop chronic back pain.2

The diagnostic approach to low back pain varies widely.3 Some data indicate that early imaging of back pain can lead to unneeded follow-up testing, radiation exposure, unnecessary surgery, patient “labeling,” and increased health care costs, all of which suggest that routine imaging shouldn’t be pursued in acute low back pain.4

Red flags for acute low back pain that warrant imaging include age >50 years, fever, weight loss, elevated ESR, history of malignancy, trauma, motor deficits, steroid or illicit drug use, and litigation.1 If not already done, it’s also important to order a CBC, ESR, and CRP for patients with any of these red flags.

Imaging studies are important, but clinical correlation is crucial because imaging can reveal disk abnormalities even in healthy, asymptomatic patients.5 Computed tomography scans or MRI is indicated for patients with neurologic deficits or nerve root tension signs, but only if a patient is a potential candidate for surgery or epidural steroid injection.6,7 If you suspect an infection (such as spondylodiscitis or osteomyelitis), diagnosing the condition quickly is key.

Our patient had 2 red flags (age >50 years and elevated ESR) that helped us reach an unlikely diagnosis of lumbar osteomyelitis with S. salivarius as the cause. Degenerative spinal disease seen on x-ray may have delayed our patient’s diagnosis. If our patient had had an ESR or CRP test earlier, or if further imaging had been conducted sooner (given her proximal muscle weakness), the correct diagnosis would have been made more quickly and appropriate treatment provided sooner.

Our patient

The patient was started on a 6-week course of intravenous ceftriaxone 2g/d, which she continued to receive at home via a peripherally inserted central catheter. The patient was instructed at discharge (on Day 8) to follow up with her FP, which she did 12 days later. At that visit, her back pain was improved and her ESR and CRP levels were within normal ranges.

THE TAKEAWAY

When evaluating a patient who presents with low back pain, perform a focused history and be on the lookout for “red flags” that warrant further imaging and testing. Routine imaging is not recommended for patients with nonspecific low back pain, but imaging may be indicated for patients with neurologic deficits or nerve root tension signs.

A patient with low back pain caused by osteomyelitis may present with fever, elevated ESR, and/or motor deficits. Identifying the bacteria underlying the infection will help guide selection of appropriate antibiotics.

1. Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:363-370.

2. Deyo RA, Phillips WR. Low back pain. A primary care challenge. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:2826-2832.

3. Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Wheeler K, et al. Physician variation in diagnostic testing for low back pain. Who you see is what you get. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:15-22.

4. Srinivas SV, Deyo RA, Berger ZD. Application of “less is more” to low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1016-1020.

5. Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69-73.

6. Wipf JE, Deyo RA. Low back pain. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79:231-246.

7. Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al; Clinical Efficacy Assessment Committee of the American College of Physicians; American College of Physicians; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478-493.

THE CASE

An 84-year old woman came to the emergency department (ED) with sharp back pain on her left side that she’d had for 4 days. The pain radiated to her posterior hips when standing. She said her whole body felt achy and she was experiencing weakness in both legs.

The patient had a history of hypertension, coronary artery disease, and aortic stenosis; she’d received a bioprosthetic aortic valve 7 years ago. She was not immunocompromised or receiving steroids but was taking docusate, oxybutynin, carvedilol, amlodipine, atorvastatin, furosemide, rivaroxaban, and a multivitamin. Her physical exam, vital signs, and complete blood count (CBC) were normal. An x-ray of the lumbar spine showed degenerative joint/disc disease and spondylosis at L4-L5 and L5-S1. The patient was sent home with oxycodone/acetaminophen 5 mg/325 mg every 6 hours as needed for pain and told to follow up with her family physician (FP).

Six days later, the patient went to see her FP and told her that her symptoms hadn’t improved. She was afebrile and her blood pressure was 150/80 mm Hg. Her muscle strength was 4/5 with hip flexion bilaterally; the rest of her strength was 5/5. There was no lumbar paraspinal tenderness and she had a negative straight leg raise test. No other neurologic deficits were noted. The FP prescribed physical therapy at home with a licensed therapist, which consisted of stretching exercises and active, dynamic exercise to improve the patient’s range of motion. She also ordered outpatient lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

THE DIAGNOSIS

Approximately 3 weeks later, the patient’s MRI revealed osteomyelitis/discitis at the L3-L4 level and severe tricompartmental stenosis from L2-L3 through L4-L5. A day after receiving the results—and about a month after having first gone to the ED—the patient was admitted to the hospital. She was afebrile and her blood pressure was 148/75 mm Hg. Her physical exam revealed no leukocytosis or neurologic deficits, but did show a systolic murmur from her aortic valve.

She had an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 77 mm/hr (normal range for women, <30 mm/hr) and her C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 5.88 mg/dL (<.50 mg/dL indicates average risk for cardiovascular disease). A transesophageal echocardiogram was performed and there was no sign of vegetation or thrombi. However, blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus salivarius—a bacterium found on human dental plaque—which we determined was the cause of the osteomyelitis.

To the best of our knowledge, there have been no other case reports that described S. salivarius as having caused osteomyelitis without concurrent endocarditis.

DISCUSSION

Back pain is a common and costly issue among primary care patients. More than two-thirds of adults suffer from low back pain at some point, primarily without underlying malignancy or neurologic deficits.1,2 Acute low back pain is often mechanical (97%); however, other causes, including infection, may be to blame (TABLE).1 Most acute back pain will improve with conservative treatment and patients need only reassurance of a favorable prognosis, but 20% of patients may develop chronic back pain.2

The diagnostic approach to low back pain varies widely.3 Some data indicate that early imaging of back pain can lead to unneeded follow-up testing, radiation exposure, unnecessary surgery, patient “labeling,” and increased health care costs, all of which suggest that routine imaging shouldn’t be pursued in acute low back pain.4

Red flags for acute low back pain that warrant imaging include age >50 years, fever, weight loss, elevated ESR, history of malignancy, trauma, motor deficits, steroid or illicit drug use, and litigation.1 If not already done, it’s also important to order a CBC, ESR, and CRP for patients with any of these red flags.

Imaging studies are important, but clinical correlation is crucial because imaging can reveal disk abnormalities even in healthy, asymptomatic patients.5 Computed tomography scans or MRI is indicated for patients with neurologic deficits or nerve root tension signs, but only if a patient is a potential candidate for surgery or epidural steroid injection.6,7 If you suspect an infection (such as spondylodiscitis or osteomyelitis), diagnosing the condition quickly is key.

Our patient had 2 red flags (age >50 years and elevated ESR) that helped us reach an unlikely diagnosis of lumbar osteomyelitis with S. salivarius as the cause. Degenerative spinal disease seen on x-ray may have delayed our patient’s diagnosis. If our patient had had an ESR or CRP test earlier, or if further imaging had been conducted sooner (given her proximal muscle weakness), the correct diagnosis would have been made more quickly and appropriate treatment provided sooner.