User login

Many EMS protocols for status epilepticus do not follow evidence-based guidelines

“Many protocols did not follow evidence-based guidelines and did not accurately define generalized convulsive status epilepticus,” said John P. Betjemann, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues. They reported their findings in the March 26 issue of JAMA.

Generalized convulsive status epilepticus is a neurologic emergency, and trials published in 2001 and 2012 found that benzodiazepines are effective prehospital treatments for patients with generalized convulsive status epilepticus. These trials informed a 2016 evidence-based guideline that cites level A evidence for intramuscular midazolam, IV lorazepam, and IV diazepam as initial treatment options for adults.

To determine whether EMS system protocols follow these recommendations, the investigators reviewed treatment protocols from 33 EMS systems that cover the 58 counties in California. The researchers reviewed EMS system protocols between May and June 2018 to determine when they were last updated and whether they defined generalized convulsive status epilepticus according to the guideline (namely, 5 or more minutes of continuous seizure or two or more discrete seizures between which a patient has incomplete recovery of consciousness). They also determined whether the protocols included any of the three benzodiazepines in the guideline and, if so, at what dose and using which route of administration.

Protocols’ most recent revision dates ranged between 2007 and 2018. Twenty-seven protocols (81.8%) were revised after the second clinical trial was published in 2012, and 17 (51.5%) were revised after the 2016 guideline. Seven EMS system protocols (21.2%) defined generalized convulsive status epilepticus according to the guideline. Thirty-two protocols (97.0%) included intramuscular midazolam, 2 (6.1%) included IV lorazepam, and 5 (15.2%) included IV diazepam.

Although the protocols “appropriately emphasized” intramuscular midazolam, the protocol doses often were lower than those used in the trials or recommended in the guideline. In addition, most protocols listed IV and intraosseous midazolam as options, although these treatments were not studied in the trials nor recommended in the guideline. In all, six of the protocols (18.2%) recommended at least one medication by the route and dose suggested in the trials or in the guideline.

“Why EMS system protocols deviate from the evidence and how this affects patient outcomes deserves further study,” the authors said.

The researchers noted that they examined EMS protocols in only one state and that “protocols may not necessarily reflect what emergency medical technicians actually do in practice.” In addition, the researchers accessed the most recent protocols by consulting EMS system websites rather than by contacting each EMS system for its most up-to-date protocol.

The authors reported personal compensation from JAMA Neurology and from Continuum Audio unrelated to the present study, as well as grants from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Betjemann JP et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 26.

“Many protocols did not follow evidence-based guidelines and did not accurately define generalized convulsive status epilepticus,” said John P. Betjemann, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues. They reported their findings in the March 26 issue of JAMA.

Generalized convulsive status epilepticus is a neurologic emergency, and trials published in 2001 and 2012 found that benzodiazepines are effective prehospital treatments for patients with generalized convulsive status epilepticus. These trials informed a 2016 evidence-based guideline that cites level A evidence for intramuscular midazolam, IV lorazepam, and IV diazepam as initial treatment options for adults.

To determine whether EMS system protocols follow these recommendations, the investigators reviewed treatment protocols from 33 EMS systems that cover the 58 counties in California. The researchers reviewed EMS system protocols between May and June 2018 to determine when they were last updated and whether they defined generalized convulsive status epilepticus according to the guideline (namely, 5 or more minutes of continuous seizure or two or more discrete seizures between which a patient has incomplete recovery of consciousness). They also determined whether the protocols included any of the three benzodiazepines in the guideline and, if so, at what dose and using which route of administration.

Protocols’ most recent revision dates ranged between 2007 and 2018. Twenty-seven protocols (81.8%) were revised after the second clinical trial was published in 2012, and 17 (51.5%) were revised after the 2016 guideline. Seven EMS system protocols (21.2%) defined generalized convulsive status epilepticus according to the guideline. Thirty-two protocols (97.0%) included intramuscular midazolam, 2 (6.1%) included IV lorazepam, and 5 (15.2%) included IV diazepam.

Although the protocols “appropriately emphasized” intramuscular midazolam, the protocol doses often were lower than those used in the trials or recommended in the guideline. In addition, most protocols listed IV and intraosseous midazolam as options, although these treatments were not studied in the trials nor recommended in the guideline. In all, six of the protocols (18.2%) recommended at least one medication by the route and dose suggested in the trials or in the guideline.

“Why EMS system protocols deviate from the evidence and how this affects patient outcomes deserves further study,” the authors said.

The researchers noted that they examined EMS protocols in only one state and that “protocols may not necessarily reflect what emergency medical technicians actually do in practice.” In addition, the researchers accessed the most recent protocols by consulting EMS system websites rather than by contacting each EMS system for its most up-to-date protocol.

The authors reported personal compensation from JAMA Neurology and from Continuum Audio unrelated to the present study, as well as grants from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Betjemann JP et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 26.

“Many protocols did not follow evidence-based guidelines and did not accurately define generalized convulsive status epilepticus,” said John P. Betjemann, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues. They reported their findings in the March 26 issue of JAMA.

Generalized convulsive status epilepticus is a neurologic emergency, and trials published in 2001 and 2012 found that benzodiazepines are effective prehospital treatments for patients with generalized convulsive status epilepticus. These trials informed a 2016 evidence-based guideline that cites level A evidence for intramuscular midazolam, IV lorazepam, and IV diazepam as initial treatment options for adults.

To determine whether EMS system protocols follow these recommendations, the investigators reviewed treatment protocols from 33 EMS systems that cover the 58 counties in California. The researchers reviewed EMS system protocols between May and June 2018 to determine when they were last updated and whether they defined generalized convulsive status epilepticus according to the guideline (namely, 5 or more minutes of continuous seizure or two or more discrete seizures between which a patient has incomplete recovery of consciousness). They also determined whether the protocols included any of the three benzodiazepines in the guideline and, if so, at what dose and using which route of administration.

Protocols’ most recent revision dates ranged between 2007 and 2018. Twenty-seven protocols (81.8%) were revised after the second clinical trial was published in 2012, and 17 (51.5%) were revised after the 2016 guideline. Seven EMS system protocols (21.2%) defined generalized convulsive status epilepticus according to the guideline. Thirty-two protocols (97.0%) included intramuscular midazolam, 2 (6.1%) included IV lorazepam, and 5 (15.2%) included IV diazepam.

Although the protocols “appropriately emphasized” intramuscular midazolam, the protocol doses often were lower than those used in the trials or recommended in the guideline. In addition, most protocols listed IV and intraosseous midazolam as options, although these treatments were not studied in the trials nor recommended in the guideline. In all, six of the protocols (18.2%) recommended at least one medication by the route and dose suggested in the trials or in the guideline.

“Why EMS system protocols deviate from the evidence and how this affects patient outcomes deserves further study,” the authors said.

The researchers noted that they examined EMS protocols in only one state and that “protocols may not necessarily reflect what emergency medical technicians actually do in practice.” In addition, the researchers accessed the most recent protocols by consulting EMS system websites rather than by contacting each EMS system for its most up-to-date protocol.

The authors reported personal compensation from JAMA Neurology and from Continuum Audio unrelated to the present study, as well as grants from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Betjemann JP et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 26.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Many emergency medical services (EMS) system protocols may not follow evidence-based guidelines or accurately define generalized convulsive status epilepticus.

Major finding: In all, 18.2% of the protocols recommended at least one medication by the route and at the dose suggested in clinical trials or in an evidence-based guideline.

Study details: A review of treatment protocols from 33 EMS systems that cover the 58 counties in California.

Disclosures: The authors reported personal compensation from JAMA Neurology and Continuum Audio unrelated to the present study and grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Betjemann JP et al. JAMA. 2019 March 26.

Can intraputamenal infusions of GDNF treat Parkinson’s disease?

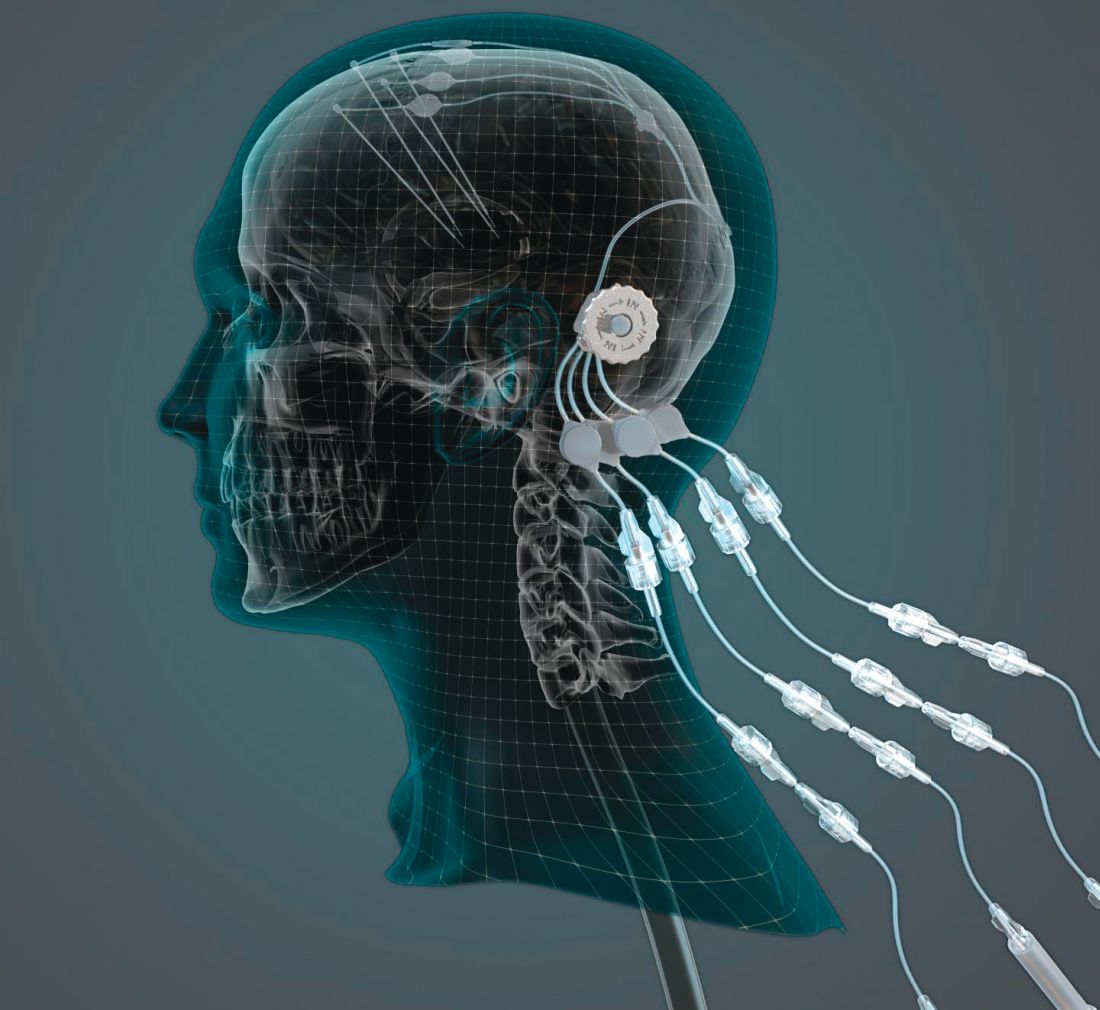

researchers reported. The investigational therapy, delivered through a skull-mounted port, was well tolerated in a 40-week, randomized, controlled trial and a 40-week, open-label extension.

Neither study met its primary endpoint, but post hoc analyses suggest possible clinical benefits. In addition, PET imaging after the 40-week, randomized trial found significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake in patients who received GDNF. The randomized trial was published in the March 2019 issue of Brain; data from the open-label extension were published online ahead of print Feb. 26, 2019, in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease.

“The spatial and relative magnitude of the improvement in the brain scans is beyond anything seen previously in trials of surgically delivered growth-factor treatments for Parkinson’s [disease],” said principal investigator Alan L. Whone, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol (England) and North Bristol National Health Service Trust. “This represents some of the most compelling evidence yet that we may have a means to possibly reawaken and restore the dopamine brain cells that are gradually destroyed in Parkinson’s [disease].”

Nevertheless, the trial did not confirm clinical benefits. The hypothesis that growth factors can benefit patients with Parkinson’s disease may be incorrect, the researchers acknowledged. It also is possible that the hypothesis is valid and that a trial with a higher GDNF dose, longer treatment duration, patients with an earlier disease stage, or different outcome measures would yield positive results. GDNF warrants further study, they wrote.

The findings could have implications for other neurologic disorders as well.

“This trial has shown that we can safely and repeatedly infuse drugs directly into patients’ brains over months or years. This is a significant breakthrough in our ability to treat neurologic conditions ... because most drugs that might work cannot cross from the bloodstream into the brain,” said Steven Gill, MB, MS. Mr. Gill, of the North Bristol NHS Trust and the U.K.-based engineering firm Renishaw, designed the convection-enhanced delivery system used in the studies.

A neurotrophic protein

GDNF has neurorestorative and neuroprotective effects in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. In open-label studies, continuous, low-rate intraputamenal administration of GDNF has shown signs of potential efficacy, but a placebo-controlled trial did not replicate clinical benefits. In the present studies, the researchers assessed intermittent GDNF administration using convection-enhanced delivery, which can achieve wider and more even distribution of GDNF, compared with the previous approach.

The researchers conducted a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to study this novel administration approach. Patients were aged 35-75 years, had motor symptoms for at least 5 years, and had moderate disease severity in the off state (that is, Hoehn and Yahr stage 2-3 and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor score–part III [UPDRS-III] of 25-45).

In a pilot stage of the trial, six patients were randomized 2:1 to receive GDNF (120 mcg per putamen) or placebo. In the primary stage, another 35 patients were randomized 1:1 to GDNF or placebo. The primary outcome was the percentage change from baseline to week 40 in the off-state UPDRS-III among patients from the primary stage of the trial. Further analyses included all 41 patients from the pilot and primary stages.

Patients in the primary analysis had a mean age of 56.4 years and mean disease duration of 10.9 years. About half were female.

Results on primary and secondary clinical endpoints did not significantly differ between the groups. Average off state UPDRS motor score decreased by 17.3 in the active treatment group, compared with 11.8 in the placebo group.

A post hoc analysis, however, found that nine patients (43%) in the active-treatment group had a large, clinically important motor improvement of 10 or more points in the off state, whereas no placebo patients did. These “10-point responders in the GDNF group are a potential focus of interest; however, as this is a post hoc finding we would not wish to overinterpret its meaning,” Dr. Whone and his colleagues wrote. Among patients who received GDNF, PET imaging demonstrated significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake throughout the putamen, ranging from a 25% increase in the left anterior putamen to a 100% increase in both posterior putamena, whereas patients who received placebo did not have significantly increased uptake.

No drug-related serious adverse events were reported. “The majority of device-related adverse events were port site associated, most commonly local hypertrophic scarring or infections, amenable to antibiotics,” the investigators wrote. “The frequency of these declined during the trial as surgical and device handling experience improved.”

Open-label extension

By week 80, when all participants had received GDNF, both groups showed moderate to large improvement in symptoms, compared with baseline. From baseline to week 80, percentage change in UPDRS motor score in the off state did not significantly differ between patients who received GDNF for 80 weeks and patients who received placebo followed by GDNF (26.7% vs. 27.6%). Secondary endpoints also did not differ between the groups. Treatment compliance was 97.8%; no patients discontinued the study.

The trials were funded by Parkinson’s UK with support from the Cure Parkinson’s Trust and in association with the North Bristol NHS Trust. GDNF and additional resources and funding were provided by MedGenesis Therapeutix, which owns the license for GDNF and received funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Renishaw manufactured the convection-enhanced delivery device on behalf of North Bristol NHS Trust. The Gatsby Foundation provided a 3T MRI scanner. Some study authors are employed by and have shares or share options with MedGenesis Therapeutix. Other authors are employees of Renishaw. Dr. Gill is Renishaw’s medical director and may have a future royalty share from the drug delivery system that he invented.

SOURCES: Whone AL et al. Brain. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz023; Whone AL et al. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191576.

researchers reported. The investigational therapy, delivered through a skull-mounted port, was well tolerated in a 40-week, randomized, controlled trial and a 40-week, open-label extension.

Neither study met its primary endpoint, but post hoc analyses suggest possible clinical benefits. In addition, PET imaging after the 40-week, randomized trial found significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake in patients who received GDNF. The randomized trial was published in the March 2019 issue of Brain; data from the open-label extension were published online ahead of print Feb. 26, 2019, in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease.

“The spatial and relative magnitude of the improvement in the brain scans is beyond anything seen previously in trials of surgically delivered growth-factor treatments for Parkinson’s [disease],” said principal investigator Alan L. Whone, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol (England) and North Bristol National Health Service Trust. “This represents some of the most compelling evidence yet that we may have a means to possibly reawaken and restore the dopamine brain cells that are gradually destroyed in Parkinson’s [disease].”

Nevertheless, the trial did not confirm clinical benefits. The hypothesis that growth factors can benefit patients with Parkinson’s disease may be incorrect, the researchers acknowledged. It also is possible that the hypothesis is valid and that a trial with a higher GDNF dose, longer treatment duration, patients with an earlier disease stage, or different outcome measures would yield positive results. GDNF warrants further study, they wrote.

The findings could have implications for other neurologic disorders as well.

“This trial has shown that we can safely and repeatedly infuse drugs directly into patients’ brains over months or years. This is a significant breakthrough in our ability to treat neurologic conditions ... because most drugs that might work cannot cross from the bloodstream into the brain,” said Steven Gill, MB, MS. Mr. Gill, of the North Bristol NHS Trust and the U.K.-based engineering firm Renishaw, designed the convection-enhanced delivery system used in the studies.

A neurotrophic protein

GDNF has neurorestorative and neuroprotective effects in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. In open-label studies, continuous, low-rate intraputamenal administration of GDNF has shown signs of potential efficacy, but a placebo-controlled trial did not replicate clinical benefits. In the present studies, the researchers assessed intermittent GDNF administration using convection-enhanced delivery, which can achieve wider and more even distribution of GDNF, compared with the previous approach.

The researchers conducted a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to study this novel administration approach. Patients were aged 35-75 years, had motor symptoms for at least 5 years, and had moderate disease severity in the off state (that is, Hoehn and Yahr stage 2-3 and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor score–part III [UPDRS-III] of 25-45).

In a pilot stage of the trial, six patients were randomized 2:1 to receive GDNF (120 mcg per putamen) or placebo. In the primary stage, another 35 patients were randomized 1:1 to GDNF or placebo. The primary outcome was the percentage change from baseline to week 40 in the off-state UPDRS-III among patients from the primary stage of the trial. Further analyses included all 41 patients from the pilot and primary stages.

Patients in the primary analysis had a mean age of 56.4 years and mean disease duration of 10.9 years. About half were female.

Results on primary and secondary clinical endpoints did not significantly differ between the groups. Average off state UPDRS motor score decreased by 17.3 in the active treatment group, compared with 11.8 in the placebo group.

A post hoc analysis, however, found that nine patients (43%) in the active-treatment group had a large, clinically important motor improvement of 10 or more points in the off state, whereas no placebo patients did. These “10-point responders in the GDNF group are a potential focus of interest; however, as this is a post hoc finding we would not wish to overinterpret its meaning,” Dr. Whone and his colleagues wrote. Among patients who received GDNF, PET imaging demonstrated significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake throughout the putamen, ranging from a 25% increase in the left anterior putamen to a 100% increase in both posterior putamena, whereas patients who received placebo did not have significantly increased uptake.

No drug-related serious adverse events were reported. “The majority of device-related adverse events were port site associated, most commonly local hypertrophic scarring or infections, amenable to antibiotics,” the investigators wrote. “The frequency of these declined during the trial as surgical and device handling experience improved.”

Open-label extension

By week 80, when all participants had received GDNF, both groups showed moderate to large improvement in symptoms, compared with baseline. From baseline to week 80, percentage change in UPDRS motor score in the off state did not significantly differ between patients who received GDNF for 80 weeks and patients who received placebo followed by GDNF (26.7% vs. 27.6%). Secondary endpoints also did not differ between the groups. Treatment compliance was 97.8%; no patients discontinued the study.

The trials were funded by Parkinson’s UK with support from the Cure Parkinson’s Trust and in association with the North Bristol NHS Trust. GDNF and additional resources and funding were provided by MedGenesis Therapeutix, which owns the license for GDNF and received funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Renishaw manufactured the convection-enhanced delivery device on behalf of North Bristol NHS Trust. The Gatsby Foundation provided a 3T MRI scanner. Some study authors are employed by and have shares or share options with MedGenesis Therapeutix. Other authors are employees of Renishaw. Dr. Gill is Renishaw’s medical director and may have a future royalty share from the drug delivery system that he invented.

SOURCES: Whone AL et al. Brain. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz023; Whone AL et al. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191576.

researchers reported. The investigational therapy, delivered through a skull-mounted port, was well tolerated in a 40-week, randomized, controlled trial and a 40-week, open-label extension.

Neither study met its primary endpoint, but post hoc analyses suggest possible clinical benefits. In addition, PET imaging after the 40-week, randomized trial found significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake in patients who received GDNF. The randomized trial was published in the March 2019 issue of Brain; data from the open-label extension were published online ahead of print Feb. 26, 2019, in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease.

“The spatial and relative magnitude of the improvement in the brain scans is beyond anything seen previously in trials of surgically delivered growth-factor treatments for Parkinson’s [disease],” said principal investigator Alan L. Whone, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol (England) and North Bristol National Health Service Trust. “This represents some of the most compelling evidence yet that we may have a means to possibly reawaken and restore the dopamine brain cells that are gradually destroyed in Parkinson’s [disease].”

Nevertheless, the trial did not confirm clinical benefits. The hypothesis that growth factors can benefit patients with Parkinson’s disease may be incorrect, the researchers acknowledged. It also is possible that the hypothesis is valid and that a trial with a higher GDNF dose, longer treatment duration, patients with an earlier disease stage, or different outcome measures would yield positive results. GDNF warrants further study, they wrote.

The findings could have implications for other neurologic disorders as well.

“This trial has shown that we can safely and repeatedly infuse drugs directly into patients’ brains over months or years. This is a significant breakthrough in our ability to treat neurologic conditions ... because most drugs that might work cannot cross from the bloodstream into the brain,” said Steven Gill, MB, MS. Mr. Gill, of the North Bristol NHS Trust and the U.K.-based engineering firm Renishaw, designed the convection-enhanced delivery system used in the studies.

A neurotrophic protein

GDNF has neurorestorative and neuroprotective effects in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. In open-label studies, continuous, low-rate intraputamenal administration of GDNF has shown signs of potential efficacy, but a placebo-controlled trial did not replicate clinical benefits. In the present studies, the researchers assessed intermittent GDNF administration using convection-enhanced delivery, which can achieve wider and more even distribution of GDNF, compared with the previous approach.

The researchers conducted a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to study this novel administration approach. Patients were aged 35-75 years, had motor symptoms for at least 5 years, and had moderate disease severity in the off state (that is, Hoehn and Yahr stage 2-3 and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor score–part III [UPDRS-III] of 25-45).

In a pilot stage of the trial, six patients were randomized 2:1 to receive GDNF (120 mcg per putamen) or placebo. In the primary stage, another 35 patients were randomized 1:1 to GDNF or placebo. The primary outcome was the percentage change from baseline to week 40 in the off-state UPDRS-III among patients from the primary stage of the trial. Further analyses included all 41 patients from the pilot and primary stages.

Patients in the primary analysis had a mean age of 56.4 years and mean disease duration of 10.9 years. About half were female.

Results on primary and secondary clinical endpoints did not significantly differ between the groups. Average off state UPDRS motor score decreased by 17.3 in the active treatment group, compared with 11.8 in the placebo group.

A post hoc analysis, however, found that nine patients (43%) in the active-treatment group had a large, clinically important motor improvement of 10 or more points in the off state, whereas no placebo patients did. These “10-point responders in the GDNF group are a potential focus of interest; however, as this is a post hoc finding we would not wish to overinterpret its meaning,” Dr. Whone and his colleagues wrote. Among patients who received GDNF, PET imaging demonstrated significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake throughout the putamen, ranging from a 25% increase in the left anterior putamen to a 100% increase in both posterior putamena, whereas patients who received placebo did not have significantly increased uptake.

No drug-related serious adverse events were reported. “The majority of device-related adverse events were port site associated, most commonly local hypertrophic scarring or infections, amenable to antibiotics,” the investigators wrote. “The frequency of these declined during the trial as surgical and device handling experience improved.”

Open-label extension

By week 80, when all participants had received GDNF, both groups showed moderate to large improvement in symptoms, compared with baseline. From baseline to week 80, percentage change in UPDRS motor score in the off state did not significantly differ between patients who received GDNF for 80 weeks and patients who received placebo followed by GDNF (26.7% vs. 27.6%). Secondary endpoints also did not differ between the groups. Treatment compliance was 97.8%; no patients discontinued the study.

The trials were funded by Parkinson’s UK with support from the Cure Parkinson’s Trust and in association with the North Bristol NHS Trust. GDNF and additional resources and funding were provided by MedGenesis Therapeutix, which owns the license for GDNF and received funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Renishaw manufactured the convection-enhanced delivery device on behalf of North Bristol NHS Trust. The Gatsby Foundation provided a 3T MRI scanner. Some study authors are employed by and have shares or share options with MedGenesis Therapeutix. Other authors are employees of Renishaw. Dr. Gill is Renishaw’s medical director and may have a future royalty share from the drug delivery system that he invented.

SOURCES: Whone AL et al. Brain. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz023; Whone AL et al. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191576.

Does adherence to a Mediterranean diet reduce the risk of Parkinson’s disease?

Among older adults, adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, according to research published in Movement Disorders.

“Recommending the Mediterranean diet pattern, either to reduce the risk or lessen the effects ... of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, needs to be considered and further explored,” said lead author Maria I. Maraki, PhD, of the department of nutrition and dietetics at Harokopio University in Athens, Greece, and her research colleagues.

Evidence regarding the effect of a Mediterranean diet on Parkinson’s disease risk remains limited, however, and physicians should be cautious in interpreting the data, researchers noted in accompanying editorials.

“There is a puzzling constellation of information and data that cannot be reconciled with a simple model accounting for the role of diet, vascular risk factors, and the neurodegenerative process and mechanisms underlying Parkinson’s disease,” Connie Marras, MD, PhD, and Jose A. Obeso, MD, PhD, said in an editorial. Given Maraki et al.’s findings, “most of us would be glad to accept that such a causal inverse association exists and can therefore be strongly recommended to our patients,” but “further work is needed before definitive conclusions can be reached,” Dr. Marras and Dr. Obeso wrote. Dr. Marras is affiliated with the University Health Network and the University of Toronto. Dr. Obeso is affiliated with University Hospital HM Puerta del Sur, CEU San Pablo University, Móstoles, Spain.

The role of diet

Prior research has suggested that adherence to the Mediterranean diet – characterized by consumption of nonrefined cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, potatoes, fish, and olive oil – may be associated with reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, studies have found that adherence to the Mediterranean diet may be protective in other diseases, including dementia and cardiovascular disease. Dr. Maraki and her colleagues sought to assess whether adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with the likelihood of prodromal Parkinson’s disease or its manifestations. To calculate the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the investigators used a tool created by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) that takes into account baseline risk factors as well as prodromal markers such as constipation and motor slowing.

They analyzed data from 1,731 participants in the population-based Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) cohort in Greece. Participants, 41% of whom were male, were aged 65 years or older and did not have Parkinson’s disease. They completed a detailed food frequency questionnaire, and the researchers calculated how closely each participant’s diet adhered to the Mediterranean diet. Diet adherence scores ranged from 0 to 55, with higher scores indicating greater adherence.

The median probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease was 1.9% (range, 0.2%-96.7%), and the probability was lower among those with greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet. This difference was “driven mostly by nonmotor markers of prodromal Parkinson’s disease,” including depression, constipation, urinary dysfunction, and daytime somnolence, the researchers said. “Each unit increase in Mediterranean diet score was associated with a 2% decreased probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.” Compared with participants in the lowest quartile of Mediterranean diet adherence, those in the highest quartile had an approximately 21% lower probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Potential confounding

“This study pushes the prodromal criteria into performing a job they were never designed to do,” which presents potential pitfalls, Ronald B. Postuma, MD, of the department of neurology at Montreal General Hospital in Quebec, said in an accompanying editorial.

While the MDS criteria were designed to assess the likelihood that any person over age 50 years is in a state of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the present study aimed to evaluate whether a single putative risk factor for Parkinson’s disease is associated with the likelihood of its prodromal state.

In addition, the analysis did not include some of the prodromal markers that are part of the MDS criteria, including olfaction, polysomnographic-proven REM sleep behavior disorder, and dopaminergic functional neuroimaging.

“As pointed out by the researchers, many of the risk factors in the prodromal criteria are potentially confounded by factors other than Parkinson’s disease; for example, one could imagine that older people, men, or farmers (with their higher pesticide exposure) are less likely to follow the Mediterranean diet simply because of different cultural lifestyle patterns,” Dr. Postuma said.

It is also possible that the Mediterranean diet affects prodromal markers such as constipation, sleep, or depression without affecting underlying neurodegenerative disease. In any case, the effect sizes observed in the study were small, and there was no evidence that participants who adhered most closely to a Mediterranean diet had less parkinsonism, Dr. Postuma said.

These limitations do not preclude physicians from recommending the diet for other reasons. “Numerous studies, reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials consistently rank the Mediterranean diet as among the healthiest diets available,” Dr. Postuma said. “So, one can clearly recommend diets such as these, even if not necessarily for Parkinson’s disease prevention.”

Adding insights

The researchers used a Mediterranean diet score that was developed in a population of adults from metropolitan Athens, “an area not unlike the one in which the score is being applied in the HELIAD study,” Christy C. Tangney, PhD, professor of clinical nutrition and preventive medicine and associate dean for research at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said in a separate editorial. As expected, the average Mediterranean diet adherence score in this study was higher than that in the Chicago Health and Aging Project (33.2 vs. 28.2).

“If we can identify differences in diet or lifestyle patterns and risk of this latent phase of Parkinson’s disease neurodegeneration, we may be one step closer to identifying preventive measures,” she said. Follow-up reports from HELIAD and other cohorts may allow researchers to assess how changes in dietary patterns relate to changes in Parkinson’s disease markers, the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, and incident Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Tangney said.

The study authors had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. The study was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, an ESPA‐EU grant cofunded by the European Social Fund and Greek National resources, and a grant from the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity (Greece). Dr. Maraki and a coauthor have received financial support from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation. Dr. Tangney and Dr. Postuma had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Maraki MI et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1002/mds.27489.

Among older adults, adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, according to research published in Movement Disorders.

“Recommending the Mediterranean diet pattern, either to reduce the risk or lessen the effects ... of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, needs to be considered and further explored,” said lead author Maria I. Maraki, PhD, of the department of nutrition and dietetics at Harokopio University in Athens, Greece, and her research colleagues.

Evidence regarding the effect of a Mediterranean diet on Parkinson’s disease risk remains limited, however, and physicians should be cautious in interpreting the data, researchers noted in accompanying editorials.

“There is a puzzling constellation of information and data that cannot be reconciled with a simple model accounting for the role of diet, vascular risk factors, and the neurodegenerative process and mechanisms underlying Parkinson’s disease,” Connie Marras, MD, PhD, and Jose A. Obeso, MD, PhD, said in an editorial. Given Maraki et al.’s findings, “most of us would be glad to accept that such a causal inverse association exists and can therefore be strongly recommended to our patients,” but “further work is needed before definitive conclusions can be reached,” Dr. Marras and Dr. Obeso wrote. Dr. Marras is affiliated with the University Health Network and the University of Toronto. Dr. Obeso is affiliated with University Hospital HM Puerta del Sur, CEU San Pablo University, Móstoles, Spain.

The role of diet

Prior research has suggested that adherence to the Mediterranean diet – characterized by consumption of nonrefined cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, potatoes, fish, and olive oil – may be associated with reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, studies have found that adherence to the Mediterranean diet may be protective in other diseases, including dementia and cardiovascular disease. Dr. Maraki and her colleagues sought to assess whether adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with the likelihood of prodromal Parkinson’s disease or its manifestations. To calculate the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the investigators used a tool created by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) that takes into account baseline risk factors as well as prodromal markers such as constipation and motor slowing.

They analyzed data from 1,731 participants in the population-based Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) cohort in Greece. Participants, 41% of whom were male, were aged 65 years or older and did not have Parkinson’s disease. They completed a detailed food frequency questionnaire, and the researchers calculated how closely each participant’s diet adhered to the Mediterranean diet. Diet adherence scores ranged from 0 to 55, with higher scores indicating greater adherence.

The median probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease was 1.9% (range, 0.2%-96.7%), and the probability was lower among those with greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet. This difference was “driven mostly by nonmotor markers of prodromal Parkinson’s disease,” including depression, constipation, urinary dysfunction, and daytime somnolence, the researchers said. “Each unit increase in Mediterranean diet score was associated with a 2% decreased probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.” Compared with participants in the lowest quartile of Mediterranean diet adherence, those in the highest quartile had an approximately 21% lower probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Potential confounding

“This study pushes the prodromal criteria into performing a job they were never designed to do,” which presents potential pitfalls, Ronald B. Postuma, MD, of the department of neurology at Montreal General Hospital in Quebec, said in an accompanying editorial.

While the MDS criteria were designed to assess the likelihood that any person over age 50 years is in a state of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the present study aimed to evaluate whether a single putative risk factor for Parkinson’s disease is associated with the likelihood of its prodromal state.

In addition, the analysis did not include some of the prodromal markers that are part of the MDS criteria, including olfaction, polysomnographic-proven REM sleep behavior disorder, and dopaminergic functional neuroimaging.

“As pointed out by the researchers, many of the risk factors in the prodromal criteria are potentially confounded by factors other than Parkinson’s disease; for example, one could imagine that older people, men, or farmers (with their higher pesticide exposure) are less likely to follow the Mediterranean diet simply because of different cultural lifestyle patterns,” Dr. Postuma said.

It is also possible that the Mediterranean diet affects prodromal markers such as constipation, sleep, or depression without affecting underlying neurodegenerative disease. In any case, the effect sizes observed in the study were small, and there was no evidence that participants who adhered most closely to a Mediterranean diet had less parkinsonism, Dr. Postuma said.

These limitations do not preclude physicians from recommending the diet for other reasons. “Numerous studies, reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials consistently rank the Mediterranean diet as among the healthiest diets available,” Dr. Postuma said. “So, one can clearly recommend diets such as these, even if not necessarily for Parkinson’s disease prevention.”

Adding insights

The researchers used a Mediterranean diet score that was developed in a population of adults from metropolitan Athens, “an area not unlike the one in which the score is being applied in the HELIAD study,” Christy C. Tangney, PhD, professor of clinical nutrition and preventive medicine and associate dean for research at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said in a separate editorial. As expected, the average Mediterranean diet adherence score in this study was higher than that in the Chicago Health and Aging Project (33.2 vs. 28.2).

“If we can identify differences in diet or lifestyle patterns and risk of this latent phase of Parkinson’s disease neurodegeneration, we may be one step closer to identifying preventive measures,” she said. Follow-up reports from HELIAD and other cohorts may allow researchers to assess how changes in dietary patterns relate to changes in Parkinson’s disease markers, the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, and incident Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Tangney said.

The study authors had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. The study was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, an ESPA‐EU grant cofunded by the European Social Fund and Greek National resources, and a grant from the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity (Greece). Dr. Maraki and a coauthor have received financial support from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation. Dr. Tangney and Dr. Postuma had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Maraki MI et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1002/mds.27489.

Among older adults, adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, according to research published in Movement Disorders.

“Recommending the Mediterranean diet pattern, either to reduce the risk or lessen the effects ... of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, needs to be considered and further explored,” said lead author Maria I. Maraki, PhD, of the department of nutrition and dietetics at Harokopio University in Athens, Greece, and her research colleagues.

Evidence regarding the effect of a Mediterranean diet on Parkinson’s disease risk remains limited, however, and physicians should be cautious in interpreting the data, researchers noted in accompanying editorials.

“There is a puzzling constellation of information and data that cannot be reconciled with a simple model accounting for the role of diet, vascular risk factors, and the neurodegenerative process and mechanisms underlying Parkinson’s disease,” Connie Marras, MD, PhD, and Jose A. Obeso, MD, PhD, said in an editorial. Given Maraki et al.’s findings, “most of us would be glad to accept that such a causal inverse association exists and can therefore be strongly recommended to our patients,” but “further work is needed before definitive conclusions can be reached,” Dr. Marras and Dr. Obeso wrote. Dr. Marras is affiliated with the University Health Network and the University of Toronto. Dr. Obeso is affiliated with University Hospital HM Puerta del Sur, CEU San Pablo University, Móstoles, Spain.

The role of diet

Prior research has suggested that adherence to the Mediterranean diet – characterized by consumption of nonrefined cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, potatoes, fish, and olive oil – may be associated with reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, studies have found that adherence to the Mediterranean diet may be protective in other diseases, including dementia and cardiovascular disease. Dr. Maraki and her colleagues sought to assess whether adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with the likelihood of prodromal Parkinson’s disease or its manifestations. To calculate the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the investigators used a tool created by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) that takes into account baseline risk factors as well as prodromal markers such as constipation and motor slowing.

They analyzed data from 1,731 participants in the population-based Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) cohort in Greece. Participants, 41% of whom were male, were aged 65 years or older and did not have Parkinson’s disease. They completed a detailed food frequency questionnaire, and the researchers calculated how closely each participant’s diet adhered to the Mediterranean diet. Diet adherence scores ranged from 0 to 55, with higher scores indicating greater adherence.

The median probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease was 1.9% (range, 0.2%-96.7%), and the probability was lower among those with greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet. This difference was “driven mostly by nonmotor markers of prodromal Parkinson’s disease,” including depression, constipation, urinary dysfunction, and daytime somnolence, the researchers said. “Each unit increase in Mediterranean diet score was associated with a 2% decreased probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.” Compared with participants in the lowest quartile of Mediterranean diet adherence, those in the highest quartile had an approximately 21% lower probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Potential confounding

“This study pushes the prodromal criteria into performing a job they were never designed to do,” which presents potential pitfalls, Ronald B. Postuma, MD, of the department of neurology at Montreal General Hospital in Quebec, said in an accompanying editorial.

While the MDS criteria were designed to assess the likelihood that any person over age 50 years is in a state of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the present study aimed to evaluate whether a single putative risk factor for Parkinson’s disease is associated with the likelihood of its prodromal state.

In addition, the analysis did not include some of the prodromal markers that are part of the MDS criteria, including olfaction, polysomnographic-proven REM sleep behavior disorder, and dopaminergic functional neuroimaging.

“As pointed out by the researchers, many of the risk factors in the prodromal criteria are potentially confounded by factors other than Parkinson’s disease; for example, one could imagine that older people, men, or farmers (with their higher pesticide exposure) are less likely to follow the Mediterranean diet simply because of different cultural lifestyle patterns,” Dr. Postuma said.

It is also possible that the Mediterranean diet affects prodromal markers such as constipation, sleep, or depression without affecting underlying neurodegenerative disease. In any case, the effect sizes observed in the study were small, and there was no evidence that participants who adhered most closely to a Mediterranean diet had less parkinsonism, Dr. Postuma said.

These limitations do not preclude physicians from recommending the diet for other reasons. “Numerous studies, reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials consistently rank the Mediterranean diet as among the healthiest diets available,” Dr. Postuma said. “So, one can clearly recommend diets such as these, even if not necessarily for Parkinson’s disease prevention.”

Adding insights

The researchers used a Mediterranean diet score that was developed in a population of adults from metropolitan Athens, “an area not unlike the one in which the score is being applied in the HELIAD study,” Christy C. Tangney, PhD, professor of clinical nutrition and preventive medicine and associate dean for research at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said in a separate editorial. As expected, the average Mediterranean diet adherence score in this study was higher than that in the Chicago Health and Aging Project (33.2 vs. 28.2).

“If we can identify differences in diet or lifestyle patterns and risk of this latent phase of Parkinson’s disease neurodegeneration, we may be one step closer to identifying preventive measures,” she said. Follow-up reports from HELIAD and other cohorts may allow researchers to assess how changes in dietary patterns relate to changes in Parkinson’s disease markers, the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, and incident Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Tangney said.

The study authors had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. The study was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, an ESPA‐EU grant cofunded by the European Social Fund and Greek National resources, and a grant from the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity (Greece). Dr. Maraki and a coauthor have received financial support from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation. Dr. Tangney and Dr. Postuma had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Maraki MI et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1002/mds.27489.

FROM MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Key clinical point: Adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Major finding: Each 1-unit increase in Mediterranean diet score was associated with a 2% decreased probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Study details: A study of 1,731 older adults in the population-based Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) cohort in Greece.

Disclosures: The study authors had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. The study was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, an ESPA‐EU grant cofunded by the European Social Fund and Greek National resources, and a grant from the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity (Greece). Dr. Maraki and a coauthor have received financial support from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation.

Source: Maraki MI et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Oct 10. doi:10.1002/mds.27489.

International survey probes oxygen’s efficacy for cluster headache

According to the results, triptans also are highly effective, with some side effects. Newer medications deserve further study, the researchers said.

To assess the effectiveness and adverse effects of acute cluster headache medications in a large international sample, Stuart M. Pearson, a researcher in the department of psychology at the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, and his coauthors analyzed data from the Cluster Headache Questionnaire. Respondents from more than 50 countries completed the online survey; most were from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. The survey included questions about cluster headache diagnostic criteria and medication effectiveness, complications, and access to medications.

In all, 3,251 subjects participated in the questionnaire, and 2,193 respondents met criteria for the study; 1,604 had cluster headache, and 589 had probable cluster headache. Among the respondents with cluster headache, 68.8% were male, 78.0% had episodic cluster headache, and the average age was 46 years. More than half of respondents reported complete or very effective treatment for triptans (54%) and oxygen (also 54%). The proportion of respondents who reported that ergot derivatives, caffeine or energy drinks, and intranasal ketamine were completely or very effective ranged from 14% to 25%. Patients were less likely to report high levels of efficacy for opioids (6%), intranasal capsaicin (5%), and intranasal lidocaine (2%).

Participants experienced few complications from oxygen, with 99% reporting no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 97% reporting no or minimal psychological and emotional complications. Patients also reported few complications from intranasal lidocaine, intranasal ketamine, intranasal capsaicin, and caffeine and energy drinks. For triptans, 74% of respondents reported no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 85% reported no or minimal psychological and emotional complications.

Among the 139 participants with cluster headache who were aged 65 years or older, responses were similar to those for the entire population. In addition, the 589 respondents with probable cluster headache reported similar efficacy data, compared with respondents with a full diagnosis of cluster headache.

“Oxygen in particular had a high rate of complete effectiveness, a low rate of ineffectiveness, and a low rate of physical, medical, emotional, and psychological side effects,” the investigators said. “However, respondents reported that it was difficult to obtain.”

Limited insurance coverage of oxygen may affect access, even though the treatment has a Level A recommendation for the acute treatment of cluster headache in the American Headache Society guidelines, the authors said. Physicians also may pose a barrier. A prior study found that 12% of providers did not prescribe oxygen for cluster headache because they doubted its efficacy or did not know about it. In addition, there may be concerns that the treatment could be a fire hazard in a patient population that has high rates of smoking, the researchers said.

Limitations of the study include the survey’s use of nonvalidated questions, the lack of a formal clinical diagnosis of cluster headache, and the grouping of all triptans, rather than assessing individual triptan medications, such as sumatriptan subcutaneous, alone.

The study received funding from Autonomic Technologies and Clusterbusters. One of the authors has served as a paid consultant to Eli Lilly as a member of the data monitoring committee for clinical trials of galcanezumab for cluster headache and migraine.

This article was updated 3/7/2019.

SOURCE: Pearson SM et al. Headache. 2019 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13473.

According to the results, triptans also are highly effective, with some side effects. Newer medications deserve further study, the researchers said.

To assess the effectiveness and adverse effects of acute cluster headache medications in a large international sample, Stuart M. Pearson, a researcher in the department of psychology at the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, and his coauthors analyzed data from the Cluster Headache Questionnaire. Respondents from more than 50 countries completed the online survey; most were from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. The survey included questions about cluster headache diagnostic criteria and medication effectiveness, complications, and access to medications.

In all, 3,251 subjects participated in the questionnaire, and 2,193 respondents met criteria for the study; 1,604 had cluster headache, and 589 had probable cluster headache. Among the respondents with cluster headache, 68.8% were male, 78.0% had episodic cluster headache, and the average age was 46 years. More than half of respondents reported complete or very effective treatment for triptans (54%) and oxygen (also 54%). The proportion of respondents who reported that ergot derivatives, caffeine or energy drinks, and intranasal ketamine were completely or very effective ranged from 14% to 25%. Patients were less likely to report high levels of efficacy for opioids (6%), intranasal capsaicin (5%), and intranasal lidocaine (2%).

Participants experienced few complications from oxygen, with 99% reporting no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 97% reporting no or minimal psychological and emotional complications. Patients also reported few complications from intranasal lidocaine, intranasal ketamine, intranasal capsaicin, and caffeine and energy drinks. For triptans, 74% of respondents reported no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 85% reported no or minimal psychological and emotional complications.

Among the 139 participants with cluster headache who were aged 65 years or older, responses were similar to those for the entire population. In addition, the 589 respondents with probable cluster headache reported similar efficacy data, compared with respondents with a full diagnosis of cluster headache.

“Oxygen in particular had a high rate of complete effectiveness, a low rate of ineffectiveness, and a low rate of physical, medical, emotional, and psychological side effects,” the investigators said. “However, respondents reported that it was difficult to obtain.”

Limited insurance coverage of oxygen may affect access, even though the treatment has a Level A recommendation for the acute treatment of cluster headache in the American Headache Society guidelines, the authors said. Physicians also may pose a barrier. A prior study found that 12% of providers did not prescribe oxygen for cluster headache because they doubted its efficacy or did not know about it. In addition, there may be concerns that the treatment could be a fire hazard in a patient population that has high rates of smoking, the researchers said.

Limitations of the study include the survey’s use of nonvalidated questions, the lack of a formal clinical diagnosis of cluster headache, and the grouping of all triptans, rather than assessing individual triptan medications, such as sumatriptan subcutaneous, alone.

The study received funding from Autonomic Technologies and Clusterbusters. One of the authors has served as a paid consultant to Eli Lilly as a member of the data monitoring committee for clinical trials of galcanezumab for cluster headache and migraine.

This article was updated 3/7/2019.

SOURCE: Pearson SM et al. Headache. 2019 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13473.

According to the results, triptans also are highly effective, with some side effects. Newer medications deserve further study, the researchers said.

To assess the effectiveness and adverse effects of acute cluster headache medications in a large international sample, Stuart M. Pearson, a researcher in the department of psychology at the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, and his coauthors analyzed data from the Cluster Headache Questionnaire. Respondents from more than 50 countries completed the online survey; most were from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. The survey included questions about cluster headache diagnostic criteria and medication effectiveness, complications, and access to medications.

In all, 3,251 subjects participated in the questionnaire, and 2,193 respondents met criteria for the study; 1,604 had cluster headache, and 589 had probable cluster headache. Among the respondents with cluster headache, 68.8% were male, 78.0% had episodic cluster headache, and the average age was 46 years. More than half of respondents reported complete or very effective treatment for triptans (54%) and oxygen (also 54%). The proportion of respondents who reported that ergot derivatives, caffeine or energy drinks, and intranasal ketamine were completely or very effective ranged from 14% to 25%. Patients were less likely to report high levels of efficacy for opioids (6%), intranasal capsaicin (5%), and intranasal lidocaine (2%).

Participants experienced few complications from oxygen, with 99% reporting no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 97% reporting no or minimal psychological and emotional complications. Patients also reported few complications from intranasal lidocaine, intranasal ketamine, intranasal capsaicin, and caffeine and energy drinks. For triptans, 74% of respondents reported no or minimal physical and medical complications, and 85% reported no or minimal psychological and emotional complications.

Among the 139 participants with cluster headache who were aged 65 years or older, responses were similar to those for the entire population. In addition, the 589 respondents with probable cluster headache reported similar efficacy data, compared with respondents with a full diagnosis of cluster headache.

“Oxygen in particular had a high rate of complete effectiveness, a low rate of ineffectiveness, and a low rate of physical, medical, emotional, and psychological side effects,” the investigators said. “However, respondents reported that it was difficult to obtain.”

Limited insurance coverage of oxygen may affect access, even though the treatment has a Level A recommendation for the acute treatment of cluster headache in the American Headache Society guidelines, the authors said. Physicians also may pose a barrier. A prior study found that 12% of providers did not prescribe oxygen for cluster headache because they doubted its efficacy or did not know about it. In addition, there may be concerns that the treatment could be a fire hazard in a patient population that has high rates of smoking, the researchers said.

Limitations of the study include the survey’s use of nonvalidated questions, the lack of a formal clinical diagnosis of cluster headache, and the grouping of all triptans, rather than assessing individual triptan medications, such as sumatriptan subcutaneous, alone.

The study received funding from Autonomic Technologies and Clusterbusters. One of the authors has served as a paid consultant to Eli Lilly as a member of the data monitoring committee for clinical trials of galcanezumab for cluster headache and migraine.

This article was updated 3/7/2019.

SOURCE: Pearson SM et al. Headache. 2019 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13473.

FROM HEADACHE

Key clinical point: Oxygen is a highly effective treatment for cluster headache with few complications.

Major finding: More than half of respondents (54%) reported that triptans and oxygen were completely or very effective.

Study details: Analysis of data from 1,604 people with cluster headache who completed the online Cluster Headache Questionnaire.

Disclosures: The study received funding from Autonomic Technologies and Clusterbusters. One of the authors has served as a paid consultant to Eli Lilly as a member of the data monitoring committee for clinical trials of galcanezumab for cluster headache and migraine.

Source: Pearson SM et al. Headache. 2019 Jan 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13473.

Cloud of inconsistency hangs over cannabis data

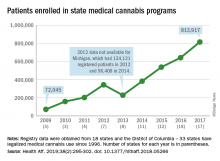

More people are using medical cannabis as it becomes legal in more states, but the lack of standardization in states’ data collection hindered investigators’ efforts to track that use.

Legalized medical cannabis is now available in 33 states and the District of Columbia, and the number of users has risen from just over 72,000 in 2009 to almost 814,000 in 2017. That 814,000, however, covers only 16 states and D.C., since 1 state (Connecticut) does not publish reports on medical cannabis use, 12 did not have statistics available, 2 (New York and Vermont) didn’t report data for 2017, and 2 (California and Maine) have voluntary registries that are unlikely to be accurate, according to Kevin F. Boehnke, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

Michigan had the largest reported number of patients enrolled in its medical cannabis program in 2017, almost 270,000. California – the state with the oldest medical cannabis legislation (passed in 1996) and the largest overall population but a voluntary cannabis registry – reported its highest number of enrollees, 12,659, in 2009-2010, the investigators said. Colorado had more than 116,000 patients in its medical cannabis program in 2010 (Health Aff. 2019;38[2]:295-302).

The “many inconsistencies in data quality across states [suggest] the need for further standardization of data collection. Such standardization would add transparency to understanding how medical cannabis programs are used, which would help guide both research and policy needs,” Dr. Boehnke and his associates wrote.

More consistency was seen in the reasons for using medical cannabis. Chronic pain made up 62.2% of all qualifying conditions reported by patients during 1999-2016, with the annual average varying between 33.3% and 73%. Multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms had the second-highest number of reports over the study period, followed by chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cancer, they reported.

The investigators also looked at the appropriateness of cannabis and determined that its use in 85.5% of patient-reported conditions was “supported by conclusive or substantial evidence of therapeutic effectiveness, according to the 2017 National Academies report” on the health effects of cannabis.

“We believe not only that it is inappropriate for cannabis to remain a Schedule I substance, but also that state and federal policy makers should begin evaluating evidence-based ways for safely integrating cannabis research and products into the health care system,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Boehnke KF et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):295-302.

More people are using medical cannabis as it becomes legal in more states, but the lack of standardization in states’ data collection hindered investigators’ efforts to track that use.

Legalized medical cannabis is now available in 33 states and the District of Columbia, and the number of users has risen from just over 72,000 in 2009 to almost 814,000 in 2017. That 814,000, however, covers only 16 states and D.C., since 1 state (Connecticut) does not publish reports on medical cannabis use, 12 did not have statistics available, 2 (New York and Vermont) didn’t report data for 2017, and 2 (California and Maine) have voluntary registries that are unlikely to be accurate, according to Kevin F. Boehnke, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

Michigan had the largest reported number of patients enrolled in its medical cannabis program in 2017, almost 270,000. California – the state with the oldest medical cannabis legislation (passed in 1996) and the largest overall population but a voluntary cannabis registry – reported its highest number of enrollees, 12,659, in 2009-2010, the investigators said. Colorado had more than 116,000 patients in its medical cannabis program in 2010 (Health Aff. 2019;38[2]:295-302).

The “many inconsistencies in data quality across states [suggest] the need for further standardization of data collection. Such standardization would add transparency to understanding how medical cannabis programs are used, which would help guide both research and policy needs,” Dr. Boehnke and his associates wrote.

More consistency was seen in the reasons for using medical cannabis. Chronic pain made up 62.2% of all qualifying conditions reported by patients during 1999-2016, with the annual average varying between 33.3% and 73%. Multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms had the second-highest number of reports over the study period, followed by chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cancer, they reported.

The investigators also looked at the appropriateness of cannabis and determined that its use in 85.5% of patient-reported conditions was “supported by conclusive or substantial evidence of therapeutic effectiveness, according to the 2017 National Academies report” on the health effects of cannabis.

“We believe not only that it is inappropriate for cannabis to remain a Schedule I substance, but also that state and federal policy makers should begin evaluating evidence-based ways for safely integrating cannabis research and products into the health care system,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Boehnke KF et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):295-302.

More people are using medical cannabis as it becomes legal in more states, but the lack of standardization in states’ data collection hindered investigators’ efforts to track that use.

Legalized medical cannabis is now available in 33 states and the District of Columbia, and the number of users has risen from just over 72,000 in 2009 to almost 814,000 in 2017. That 814,000, however, covers only 16 states and D.C., since 1 state (Connecticut) does not publish reports on medical cannabis use, 12 did not have statistics available, 2 (New York and Vermont) didn’t report data for 2017, and 2 (California and Maine) have voluntary registries that are unlikely to be accurate, according to Kevin F. Boehnke, PhD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

Michigan had the largest reported number of patients enrolled in its medical cannabis program in 2017, almost 270,000. California – the state with the oldest medical cannabis legislation (passed in 1996) and the largest overall population but a voluntary cannabis registry – reported its highest number of enrollees, 12,659, in 2009-2010, the investigators said. Colorado had more than 116,000 patients in its medical cannabis program in 2010 (Health Aff. 2019;38[2]:295-302).

The “many inconsistencies in data quality across states [suggest] the need for further standardization of data collection. Such standardization would add transparency to understanding how medical cannabis programs are used, which would help guide both research and policy needs,” Dr. Boehnke and his associates wrote.

More consistency was seen in the reasons for using medical cannabis. Chronic pain made up 62.2% of all qualifying conditions reported by patients during 1999-2016, with the annual average varying between 33.3% and 73%. Multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms had the second-highest number of reports over the study period, followed by chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cancer, they reported.

The investigators also looked at the appropriateness of cannabis and determined that its use in 85.5% of patient-reported conditions was “supported by conclusive or substantial evidence of therapeutic effectiveness, according to the 2017 National Academies report” on the health effects of cannabis.

“We believe not only that it is inappropriate for cannabis to remain a Schedule I substance, but also that state and federal policy makers should begin evaluating evidence-based ways for safely integrating cannabis research and products into the health care system,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Boehnke KF et al. Health Aff. 2019;38(2):295-302.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Clinical benefits persist 5 years after thymectomy for myasthenia gravis

Thymectomy may continue to benefit patients with myasthenia gravis 5 years after the procedure, according to an extension study published in Lancet Neurology.

The study evaluated the clinical status, medication requirements, and adverse events of patients with myasthenia gravis who completed a randomized controlled trial of thymectomy plus prednisone versus prednisone alone and agreed to participate in a rater-blinded 2-year extension.

“Thymectomy within the first few years of the disease course in addition to prednisone therapy confers benefits that persist for 5 years ... in patients with generalized nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis,” said lead study author Gil I. Wolfe, MD, chair of the department of neurology at the University at Buffalo in New York, and his research colleagues. “Results from the extension study provide further support for the use of thymectomy in management of myasthenia gravis and should encourage serious consideration of this treatment option in discussions between clinicians and their patients,” they wrote. “Our results should lead to revision of clinical guidelines in favor of thymectomy and could potentially reverse downward trends in the use of thymectomy in overall management of myasthenia gravis.”

The main 3-year results of the Thymectomy Trial in Nonthymomatous Myasthenia Gravis Patients Receiving Prednisone (MGTX) were reported in 2016; the international trial found that thymectomy plus prednisone was superior to prednisone alone at 3 years (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 11;375[6]:511-22). The extension study aimed to assess the durability of the treatment response.

MGTX enrolled patients aged 18-65 years who had generalized nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis of less than 5 years’ duration and Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Clinical Classification Class II-IV disease. Of 111 patients who completed MGTX, 68 entered the extension study, and 50 completed the 60-month assessment (24 patients in the prednisone alone group and 26 patients in the prednisone plus thymectomy group).

At 5 years, patients in the thymectomy plus prednisone group had significantly lower time-weighted average Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis (QMG) scores (5.47 vs. 9.34) and mean alternate-day prednisone doses (24 mg vs. 48 mg), compared with patients who received prednisone alone. Twelve of 35 patients in the thymectomy group and 14 of 33 patients in the prednisone group had at least one adverse event by month 60. No treatment-related deaths occurred in the extension phase.

At 5 years, significantly more patients who underwent thymectomy had minimal manifestation status (i.e., no functional limitations from the disease other than some muscle weakness) – 88% versus 58%. The corresponding figures at 3 years were 67% and 47%.

In addition, 3-year and 5-year data indicate that the need for hospitalization is reduced after surgery, compared with medical therapy alone, Dr. Wolfe said.

Two patients in each treatment arm had an increase of 2 points or more in the QMG score, indicating clinical worsening.

“Our current findings reinforce the benefit of thymectomy seen in [MGTX], dispelling doubts about the procedure’s benefits and how long those benefits last,” said Dr. Wolfe. “We do hope that the new findings help reverse the apparent reluctance to do thymectomy and that the proportion of patients with myasthenia gravis who undergo thymectomy will increase.”

The authors noted that the small sample size of the extension study may limit its generalizability.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wolfe reported grants from the NIH, the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America, CSL-Behring, and ArgenX, as well as personal fees from Grifols, Shire, and Alexion Pharmaceuticals. Coauthors reported working with and receiving funds from agencies, foundations, and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Wolfe GI et al. Lancet Neurol. 2019 Jan 25. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30392-2.

Thymectomy may continue to benefit patients with myasthenia gravis 5 years after the procedure, according to an extension study published in Lancet Neurology.

The study evaluated the clinical status, medication requirements, and adverse events of patients with myasthenia gravis who completed a randomized controlled trial of thymectomy plus prednisone versus prednisone alone and agreed to participate in a rater-blinded 2-year extension.

“Thymectomy within the first few years of the disease course in addition to prednisone therapy confers benefits that persist for 5 years ... in patients with generalized nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis,” said lead study author Gil I. Wolfe, MD, chair of the department of neurology at the University at Buffalo in New York, and his research colleagues. “Results from the extension study provide further support for the use of thymectomy in management of myasthenia gravis and should encourage serious consideration of this treatment option in discussions between clinicians and their patients,” they wrote. “Our results should lead to revision of clinical guidelines in favor of thymectomy and could potentially reverse downward trends in the use of thymectomy in overall management of myasthenia gravis.”

The main 3-year results of the Thymectomy Trial in Nonthymomatous Myasthenia Gravis Patients Receiving Prednisone (MGTX) were reported in 2016; the international trial found that thymectomy plus prednisone was superior to prednisone alone at 3 years (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 11;375[6]:511-22). The extension study aimed to assess the durability of the treatment response.

MGTX enrolled patients aged 18-65 years who had generalized nonthymomatous myasthenia gravis of less than 5 years’ duration and Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Clinical Classification Class II-IV disease. Of 111 patients who completed MGTX, 68 entered the extension study, and 50 completed the 60-month assessment (24 patients in the prednisone alone group and 26 patients in the prednisone plus thymectomy group).

At 5 years, patients in the thymectomy plus prednisone group had significantly lower time-weighted average Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis (QMG) scores (5.47 vs. 9.34) and mean alternate-day prednisone doses (24 mg vs. 48 mg), compared with patients who received prednisone alone. Twelve of 35 patients in the thymectomy group and 14 of 33 patients in the prednisone group had at least one adverse event by month 60. No treatment-related deaths occurred in the extension phase.

At 5 years, significantly more patients who underwent thymectomy had minimal manifestation status (i.e., no functional limitations from the disease other than some muscle weakness) – 88% versus 58%. The corresponding figures at 3 years were 67% and 47%.

In addition, 3-year and 5-year data indicate that the need for hospitalization is reduced after surgery, compared with medical therapy alone, Dr. Wolfe said.

Two patients in each treatment arm had an increase of 2 points or more in the QMG score, indicating clinical worsening.