User login

Cluster headache is associated with increased suicidality

Short- and long-term cluster headache disease burden, as well as depressive symptoms, contributes to suicidality, according to research published online Cephalalgia. Development of treatments that reduce the headache-related burden and prevent future bouts could reduce suicidality, said the researchers.

Although cluster headache has been called the “suicide headache,” few studies have examined suicidality in patients with cluster headache. Research by Rozen et al. found that the rate of suicidal attempt among patients was similar to that among the general population. The results have not been replicated, however, and the investigators did not examine whether suicidality varied according to the phases of the disorder.

A prospective, multicenter study

Mi Ji Lee, MD, PhD, clinical assistant professor of neurology at Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues conducted a prospective study to investigate the suicidality associated with cluster headache and the factors associated with increased suicidality in that disorder. The researchers enrolled 193 consecutive patients with cluster headache between September 2016 and August 2018 at 15 hospitals. They examined the patients and used the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the General Anxiety Disorder–7 item scale (GAD-7) screening tools. During the ictal and interictal phases, the researchers asked the patients whether they had had passive suicidal ideation, active suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, or suicidal attempt. Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses to evaluate the factors associated with high ictal suicidality, which was defined as two or more positive responses during the ictal phase. Participants were followed up during the between-bout phase.

The researchers excluded 18 patients from analysis because they were between bouts at enrollment. The mean age of the remaining 175 patients was 38.4 years. Mean age at onset was 29.9 years. About 85% of the patients were male. The diagnosis was definite cluster headache for 87.4% of the sample and probable cluster headache for 12.6%. In addition, 88% of the population had episodic cluster headache.

Suicidal ideation increased during the ictal phase

During the ictal phase, 64.2% of participants reported passive suicidal ideation, and 35.8% reported active suicidal ideation. Furthermore, 5.8% of patients had a suicidal plan, and 2.3% attempted suicide. In the interictal phase, 4.0% of patients reported passive suicidal ideation, and 3.5% reported active suicidal ideation. Interictal suicidal planning was reported by 2.9% of participants, and 1.2% of participants attempted suicide interictally. The results were similar between patients with definite and probable cluster headache.

The ictal phase increased the odds of passive suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR], 42.46), active suicidal ideation (OR, 15.55), suicidal planning (OR, 2.06), and suicidal attempt (OR, 2.02), compared with the interictal phase. The differences in suicidal planning and suicidal attempt between the ictal and interictal phases, however, were not statistically significant.

Longer disease duration, higher attack intensity, higher Headache Impact Test–6 (HIT-6) score, GAD-7 score, and PHQ-9 score were associated with high ictal suicidality. Disease duration, HIT-6, and PHQ-9 remained significantly associated with high ictal suicidality in the multivariate analysis. Younger age at onset, longer disease duration, total number of lifetime bouts, and higher GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were significantly associated with interictal suicidality in the univariable analysis. The total number of lifetime bouts and the PHQ-9 scores remained significant in the multivariable analysis.

In all, 54 patients were followed up between bouts. None reported passive suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported active suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported suicidal planning, and none reported suicidal attempt. Compared with the between-bouts period, the ictal phase was associated with significantly higher odds of active suicidal ideation (OR, 37.32) and nonsignificantly increased suicidal planning (OR, 3.20).

Patients need a disease-modifying treatment

Taken together, the study results underscore the importance of proper management of cluster headache to reduce its burden, said the authors. “Given that greater headache-related impact was independently associated with ictal suicidality, an intensive treatment to reduce the headache-related impact might be beneficial to prevent suicide in cluster headache patients,” they said. In addition to reducing headache-related impact and headache intensity, “a disease-modifying treatment to prevent further bouts is warranted to decrease suicidality in cluster headache patients.”

Although patients with cluster headache had increased suicidality in the ictal and interictal phases, they had lower suicidality between bouts, compared with the general population. This result suggests that patients remain mentally healthy when the bouts are over, and that “a strategy to shorten the length of bout is warranted,” said Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues. Furthermore, the fact that suicidality did not differ significantly between patients with definite cluster headache and those with probable cluster headache “prompts clinicians for an increased identification and intensive treatment strategy for probable cluster headache.”

The current study is the first prospective investigation of suicidality in the various phases of cluster headache, according to the investigators. It nevertheless has several limitations. The prevalence of chronic cluster headache was low in the study population, and not all patients presented for follow-up during the period between bouts. In addition, the data were obtained from recall, and consequently may be less accurate than those gained from prospective recording. Finally, Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues did not gather information on personality disorders, insomnia, substance abuse, or addiction, even though these factors can influence suicidality in patients with chronic pain.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by a grant from the Korean Neurological Association.

SOURCE: Ji Lee M et al. Cephalalgia. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1177/0333102419845660.

Short- and long-term cluster headache disease burden, as well as depressive symptoms, contributes to suicidality, according to research published online Cephalalgia. Development of treatments that reduce the headache-related burden and prevent future bouts could reduce suicidality, said the researchers.

Although cluster headache has been called the “suicide headache,” few studies have examined suicidality in patients with cluster headache. Research by Rozen et al. found that the rate of suicidal attempt among patients was similar to that among the general population. The results have not been replicated, however, and the investigators did not examine whether suicidality varied according to the phases of the disorder.

A prospective, multicenter study

Mi Ji Lee, MD, PhD, clinical assistant professor of neurology at Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues conducted a prospective study to investigate the suicidality associated with cluster headache and the factors associated with increased suicidality in that disorder. The researchers enrolled 193 consecutive patients with cluster headache between September 2016 and August 2018 at 15 hospitals. They examined the patients and used the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the General Anxiety Disorder–7 item scale (GAD-7) screening tools. During the ictal and interictal phases, the researchers asked the patients whether they had had passive suicidal ideation, active suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, or suicidal attempt. Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses to evaluate the factors associated with high ictal suicidality, which was defined as two or more positive responses during the ictal phase. Participants were followed up during the between-bout phase.

The researchers excluded 18 patients from analysis because they were between bouts at enrollment. The mean age of the remaining 175 patients was 38.4 years. Mean age at onset was 29.9 years. About 85% of the patients were male. The diagnosis was definite cluster headache for 87.4% of the sample and probable cluster headache for 12.6%. In addition, 88% of the population had episodic cluster headache.

Suicidal ideation increased during the ictal phase

During the ictal phase, 64.2% of participants reported passive suicidal ideation, and 35.8% reported active suicidal ideation. Furthermore, 5.8% of patients had a suicidal plan, and 2.3% attempted suicide. In the interictal phase, 4.0% of patients reported passive suicidal ideation, and 3.5% reported active suicidal ideation. Interictal suicidal planning was reported by 2.9% of participants, and 1.2% of participants attempted suicide interictally. The results were similar between patients with definite and probable cluster headache.

The ictal phase increased the odds of passive suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR], 42.46), active suicidal ideation (OR, 15.55), suicidal planning (OR, 2.06), and suicidal attempt (OR, 2.02), compared with the interictal phase. The differences in suicidal planning and suicidal attempt between the ictal and interictal phases, however, were not statistically significant.

Longer disease duration, higher attack intensity, higher Headache Impact Test–6 (HIT-6) score, GAD-7 score, and PHQ-9 score were associated with high ictal suicidality. Disease duration, HIT-6, and PHQ-9 remained significantly associated with high ictal suicidality in the multivariate analysis. Younger age at onset, longer disease duration, total number of lifetime bouts, and higher GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were significantly associated with interictal suicidality in the univariable analysis. The total number of lifetime bouts and the PHQ-9 scores remained significant in the multivariable analysis.

In all, 54 patients were followed up between bouts. None reported passive suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported active suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported suicidal planning, and none reported suicidal attempt. Compared with the between-bouts period, the ictal phase was associated with significantly higher odds of active suicidal ideation (OR, 37.32) and nonsignificantly increased suicidal planning (OR, 3.20).

Patients need a disease-modifying treatment

Taken together, the study results underscore the importance of proper management of cluster headache to reduce its burden, said the authors. “Given that greater headache-related impact was independently associated with ictal suicidality, an intensive treatment to reduce the headache-related impact might be beneficial to prevent suicide in cluster headache patients,” they said. In addition to reducing headache-related impact and headache intensity, “a disease-modifying treatment to prevent further bouts is warranted to decrease suicidality in cluster headache patients.”

Although patients with cluster headache had increased suicidality in the ictal and interictal phases, they had lower suicidality between bouts, compared with the general population. This result suggests that patients remain mentally healthy when the bouts are over, and that “a strategy to shorten the length of bout is warranted,” said Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues. Furthermore, the fact that suicidality did not differ significantly between patients with definite cluster headache and those with probable cluster headache “prompts clinicians for an increased identification and intensive treatment strategy for probable cluster headache.”

The current study is the first prospective investigation of suicidality in the various phases of cluster headache, according to the investigators. It nevertheless has several limitations. The prevalence of chronic cluster headache was low in the study population, and not all patients presented for follow-up during the period between bouts. In addition, the data were obtained from recall, and consequently may be less accurate than those gained from prospective recording. Finally, Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues did not gather information on personality disorders, insomnia, substance abuse, or addiction, even though these factors can influence suicidality in patients with chronic pain.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by a grant from the Korean Neurological Association.

SOURCE: Ji Lee M et al. Cephalalgia. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1177/0333102419845660.

Short- and long-term cluster headache disease burden, as well as depressive symptoms, contributes to suicidality, according to research published online Cephalalgia. Development of treatments that reduce the headache-related burden and prevent future bouts could reduce suicidality, said the researchers.

Although cluster headache has been called the “suicide headache,” few studies have examined suicidality in patients with cluster headache. Research by Rozen et al. found that the rate of suicidal attempt among patients was similar to that among the general population. The results have not been replicated, however, and the investigators did not examine whether suicidality varied according to the phases of the disorder.

A prospective, multicenter study

Mi Ji Lee, MD, PhD, clinical assistant professor of neurology at Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues conducted a prospective study to investigate the suicidality associated with cluster headache and the factors associated with increased suicidality in that disorder. The researchers enrolled 193 consecutive patients with cluster headache between September 2016 and August 2018 at 15 hospitals. They examined the patients and used the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the General Anxiety Disorder–7 item scale (GAD-7) screening tools. During the ictal and interictal phases, the researchers asked the patients whether they had had passive suicidal ideation, active suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, or suicidal attempt. Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues performed univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses to evaluate the factors associated with high ictal suicidality, which was defined as two or more positive responses during the ictal phase. Participants were followed up during the between-bout phase.

The researchers excluded 18 patients from analysis because they were between bouts at enrollment. The mean age of the remaining 175 patients was 38.4 years. Mean age at onset was 29.9 years. About 85% of the patients were male. The diagnosis was definite cluster headache for 87.4% of the sample and probable cluster headache for 12.6%. In addition, 88% of the population had episodic cluster headache.

Suicidal ideation increased during the ictal phase

During the ictal phase, 64.2% of participants reported passive suicidal ideation, and 35.8% reported active suicidal ideation. Furthermore, 5.8% of patients had a suicidal plan, and 2.3% attempted suicide. In the interictal phase, 4.0% of patients reported passive suicidal ideation, and 3.5% reported active suicidal ideation. Interictal suicidal planning was reported by 2.9% of participants, and 1.2% of participants attempted suicide interictally. The results were similar between patients with definite and probable cluster headache.

The ictal phase increased the odds of passive suicidal ideation (odds ratio [OR], 42.46), active suicidal ideation (OR, 15.55), suicidal planning (OR, 2.06), and suicidal attempt (OR, 2.02), compared with the interictal phase. The differences in suicidal planning and suicidal attempt between the ictal and interictal phases, however, were not statistically significant.

Longer disease duration, higher attack intensity, higher Headache Impact Test–6 (HIT-6) score, GAD-7 score, and PHQ-9 score were associated with high ictal suicidality. Disease duration, HIT-6, and PHQ-9 remained significantly associated with high ictal suicidality in the multivariate analysis. Younger age at onset, longer disease duration, total number of lifetime bouts, and higher GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were significantly associated with interictal suicidality in the univariable analysis. The total number of lifetime bouts and the PHQ-9 scores remained significant in the multivariable analysis.

In all, 54 patients were followed up between bouts. None reported passive suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported active suicidal ideation, 1.9% reported suicidal planning, and none reported suicidal attempt. Compared with the between-bouts period, the ictal phase was associated with significantly higher odds of active suicidal ideation (OR, 37.32) and nonsignificantly increased suicidal planning (OR, 3.20).

Patients need a disease-modifying treatment

Taken together, the study results underscore the importance of proper management of cluster headache to reduce its burden, said the authors. “Given that greater headache-related impact was independently associated with ictal suicidality, an intensive treatment to reduce the headache-related impact might be beneficial to prevent suicide in cluster headache patients,” they said. In addition to reducing headache-related impact and headache intensity, “a disease-modifying treatment to prevent further bouts is warranted to decrease suicidality in cluster headache patients.”

Although patients with cluster headache had increased suicidality in the ictal and interictal phases, they had lower suicidality between bouts, compared with the general population. This result suggests that patients remain mentally healthy when the bouts are over, and that “a strategy to shorten the length of bout is warranted,” said Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues. Furthermore, the fact that suicidality did not differ significantly between patients with definite cluster headache and those with probable cluster headache “prompts clinicians for an increased identification and intensive treatment strategy for probable cluster headache.”

The current study is the first prospective investigation of suicidality in the various phases of cluster headache, according to the investigators. It nevertheless has several limitations. The prevalence of chronic cluster headache was low in the study population, and not all patients presented for follow-up during the period between bouts. In addition, the data were obtained from recall, and consequently may be less accurate than those gained from prospective recording. Finally, Dr. Ji Lee and colleagues did not gather information on personality disorders, insomnia, substance abuse, or addiction, even though these factors can influence suicidality in patients with chronic pain.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest related to their research. The study was supported by a grant from the Korean Neurological Association.

SOURCE: Ji Lee M et al. Cephalalgia. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1177/0333102419845660.

FROM CEPHALAGIA

Key clinical point: Cluster headache is associated with increased suicidality during attacks and within the active period.

Major finding: Cluster headache attacks increased the risk of active suicidal ideation (odds ratio, 15.55).

Study details: A prospective, multicenter study of 175 patients with cluster headache.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the Korean Neurological Association.

Source: Ji Lee M et al. Cephalalgia. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1177/0333102419845660.

Out-of-pocket costs for neurologic medications rise sharply

The out-of-pocket cost of multiple sclerosis (MS) treatments increased the most, with a 20-fold increase during that time. The average out-of-pocket cost for MS therapy was $15/month in 2004, compared with $309/month in 2016. Patients also had to pay more for brand name medications for peripheral neuropathy, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease, researchers said.

“Out-of-pocket costs vary widely both across and within conditions,” said study author Brian C. Callaghan, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and research colleagues. “To minimize patient financial burden, neurologists require access to precise cost information when making treatment decisions.”

Prior studies have found that high drug costs “can create burdens such as medical debt, skipping food or other essentials, or even not taking drugs as often as necessary,” Dr. Callaghan said in a news release.

To assess how out-of-pocket costs affect patients with neurologic conditions, the investigators analyzed data from a large, privately insured health care claims database. They determined medication costs for patients with MS, peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease who were seen by outpatient neurologists. They also compared costs for high-deductible and traditional plans and explored cumulative out-of-pocket costs during the first 2 years after diagnosis.

The analysis examined the five most commonly prescribed drugs by neurologists for each condition based on Medicare data. In addition, the researchers included in their analysis all approved MS medications, lacosamide as a brand name epilepsy drug, and venlafaxine, a peripheral neuropathy medication that transitioned from brand to generic.

In all, the study population included 105,355 patients with MS, 314,530 with peripheral neuropathy, 281,073 with epilepsy, 120,720 with dementia, and 90,801 with Parkinson’s disease.

In 2016, patients in high-deductible health plans had an average monthly out-of-pocket expense that was approximately twice that of patients not in those plans – $661 versus $246 among patients with MS, and $40 versus $18 among patients with epilepsy.

In the 2 years after diagnosis in 2012 or 2013, cumulative out-of-pocket costs for patients with MS were a mean of $2,238, but costs varied widely. Cumulative costs were no more than $90 for patients in the bottom 5% of expenses, whereas they exceeded $9,800 for patients in the top 5% of expenses. Among patients with epilepsy, cumulative out-of-pocket costs were $230 in the 2 years after diagnosis.

“In 2004, out-of-pocket costs were of such low magnitude that physicians could typically ignore these costs for most patients and not adversely affect the financial status of patients or their adherence to medications. However, by 2016, out-of-pockets costs have risen to the point where neurologists should consider out-of-pocket costs for most medications and for most patients,” Dr. Callaghan and colleagues wrote.

Ralph L. Sacco, MD, president of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), said in a news release that the AAN has created a Neurology Drug Pricing Task Force and is advocating for better drug-pricing policies. “This study provides important information to help us better understand how these problems can directly affect our patients,” Dr. Sacco said.

“Everyone deserves affordable access to the medications that will be most beneficial, but if the drugs are too expensive, people may simply not take them, possibly leading to medical complications and higher costs later,” Dr. Sacco said.

The study was supported by the AAN. Several authors are supported by National Institutes of Health grants. Dr. Callaghan receives research support from Impeto Medical and performs consulting work.

SOURCE: Callaghan BC et al. Neurology. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007564.

The out-of-pocket cost of multiple sclerosis (MS) treatments increased the most, with a 20-fold increase during that time. The average out-of-pocket cost for MS therapy was $15/month in 2004, compared with $309/month in 2016. Patients also had to pay more for brand name medications for peripheral neuropathy, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease, researchers said.

“Out-of-pocket costs vary widely both across and within conditions,” said study author Brian C. Callaghan, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and research colleagues. “To minimize patient financial burden, neurologists require access to precise cost information when making treatment decisions.”

Prior studies have found that high drug costs “can create burdens such as medical debt, skipping food or other essentials, or even not taking drugs as often as necessary,” Dr. Callaghan said in a news release.

To assess how out-of-pocket costs affect patients with neurologic conditions, the investigators analyzed data from a large, privately insured health care claims database. They determined medication costs for patients with MS, peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease who were seen by outpatient neurologists. They also compared costs for high-deductible and traditional plans and explored cumulative out-of-pocket costs during the first 2 years after diagnosis.

The analysis examined the five most commonly prescribed drugs by neurologists for each condition based on Medicare data. In addition, the researchers included in their analysis all approved MS medications, lacosamide as a brand name epilepsy drug, and venlafaxine, a peripheral neuropathy medication that transitioned from brand to generic.

In all, the study population included 105,355 patients with MS, 314,530 with peripheral neuropathy, 281,073 with epilepsy, 120,720 with dementia, and 90,801 with Parkinson’s disease.

In 2016, patients in high-deductible health plans had an average monthly out-of-pocket expense that was approximately twice that of patients not in those plans – $661 versus $246 among patients with MS, and $40 versus $18 among patients with epilepsy.

In the 2 years after diagnosis in 2012 or 2013, cumulative out-of-pocket costs for patients with MS were a mean of $2,238, but costs varied widely. Cumulative costs were no more than $90 for patients in the bottom 5% of expenses, whereas they exceeded $9,800 for patients in the top 5% of expenses. Among patients with epilepsy, cumulative out-of-pocket costs were $230 in the 2 years after diagnosis.

“In 2004, out-of-pocket costs were of such low magnitude that physicians could typically ignore these costs for most patients and not adversely affect the financial status of patients or their adherence to medications. However, by 2016, out-of-pockets costs have risen to the point where neurologists should consider out-of-pocket costs for most medications and for most patients,” Dr. Callaghan and colleagues wrote.

Ralph L. Sacco, MD, president of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), said in a news release that the AAN has created a Neurology Drug Pricing Task Force and is advocating for better drug-pricing policies. “This study provides important information to help us better understand how these problems can directly affect our patients,” Dr. Sacco said.

“Everyone deserves affordable access to the medications that will be most beneficial, but if the drugs are too expensive, people may simply not take them, possibly leading to medical complications and higher costs later,” Dr. Sacco said.

The study was supported by the AAN. Several authors are supported by National Institutes of Health grants. Dr. Callaghan receives research support from Impeto Medical and performs consulting work.

SOURCE: Callaghan BC et al. Neurology. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007564.

The out-of-pocket cost of multiple sclerosis (MS) treatments increased the most, with a 20-fold increase during that time. The average out-of-pocket cost for MS therapy was $15/month in 2004, compared with $309/month in 2016. Patients also had to pay more for brand name medications for peripheral neuropathy, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease, researchers said.

“Out-of-pocket costs vary widely both across and within conditions,” said study author Brian C. Callaghan, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and research colleagues. “To minimize patient financial burden, neurologists require access to precise cost information when making treatment decisions.”

Prior studies have found that high drug costs “can create burdens such as medical debt, skipping food or other essentials, or even not taking drugs as often as necessary,” Dr. Callaghan said in a news release.

To assess how out-of-pocket costs affect patients with neurologic conditions, the investigators analyzed data from a large, privately insured health care claims database. They determined medication costs for patients with MS, peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease who were seen by outpatient neurologists. They also compared costs for high-deductible and traditional plans and explored cumulative out-of-pocket costs during the first 2 years after diagnosis.

The analysis examined the five most commonly prescribed drugs by neurologists for each condition based on Medicare data. In addition, the researchers included in their analysis all approved MS medications, lacosamide as a brand name epilepsy drug, and venlafaxine, a peripheral neuropathy medication that transitioned from brand to generic.

In all, the study population included 105,355 patients with MS, 314,530 with peripheral neuropathy, 281,073 with epilepsy, 120,720 with dementia, and 90,801 with Parkinson’s disease.

In 2016, patients in high-deductible health plans had an average monthly out-of-pocket expense that was approximately twice that of patients not in those plans – $661 versus $246 among patients with MS, and $40 versus $18 among patients with epilepsy.

In the 2 years after diagnosis in 2012 or 2013, cumulative out-of-pocket costs for patients with MS were a mean of $2,238, but costs varied widely. Cumulative costs were no more than $90 for patients in the bottom 5% of expenses, whereas they exceeded $9,800 for patients in the top 5% of expenses. Among patients with epilepsy, cumulative out-of-pocket costs were $230 in the 2 years after diagnosis.

“In 2004, out-of-pocket costs were of such low magnitude that physicians could typically ignore these costs for most patients and not adversely affect the financial status of patients or their adherence to medications. However, by 2016, out-of-pockets costs have risen to the point where neurologists should consider out-of-pocket costs for most medications and for most patients,” Dr. Callaghan and colleagues wrote.

Ralph L. Sacco, MD, president of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), said in a news release that the AAN has created a Neurology Drug Pricing Task Force and is advocating for better drug-pricing policies. “This study provides important information to help us better understand how these problems can directly affect our patients,” Dr. Sacco said.

“Everyone deserves affordable access to the medications that will be most beneficial, but if the drugs are too expensive, people may simply not take them, possibly leading to medical complications and higher costs later,” Dr. Sacco said.

The study was supported by the AAN. Several authors are supported by National Institutes of Health grants. Dr. Callaghan receives research support from Impeto Medical and performs consulting work.

SOURCE: Callaghan BC et al. Neurology. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007564.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Long-term antibiotic use may heighten stroke, CHD risk

, according to a study in the European Heart Journal.

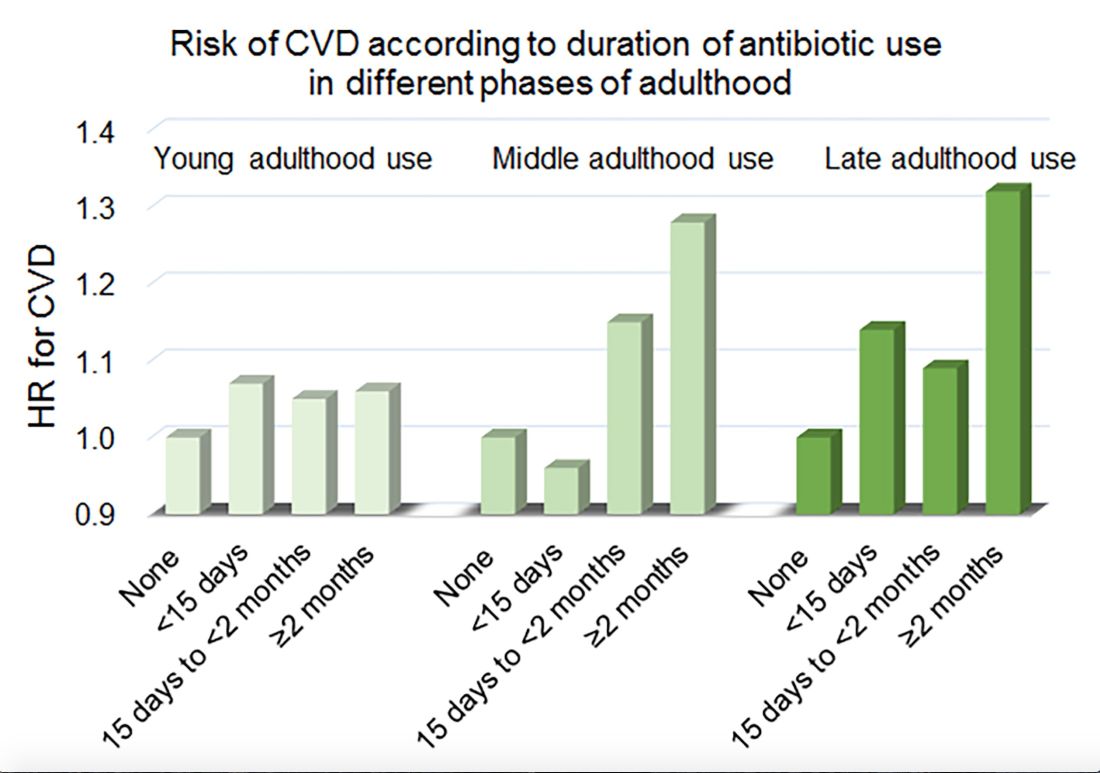

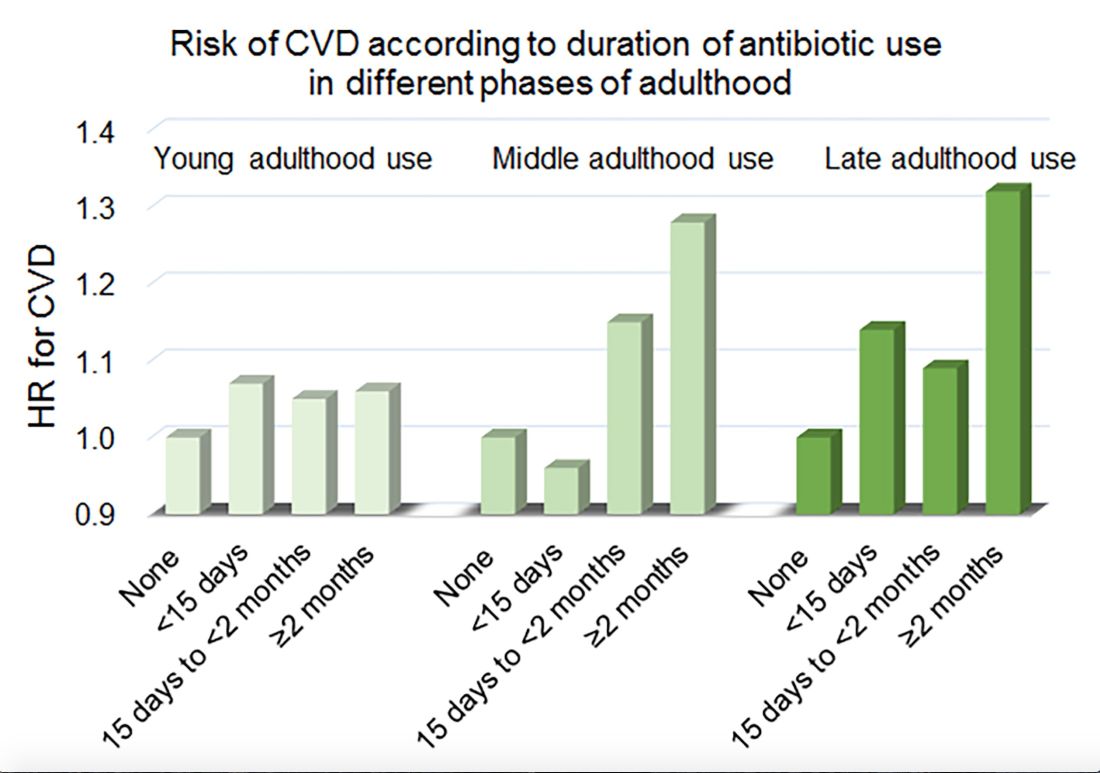

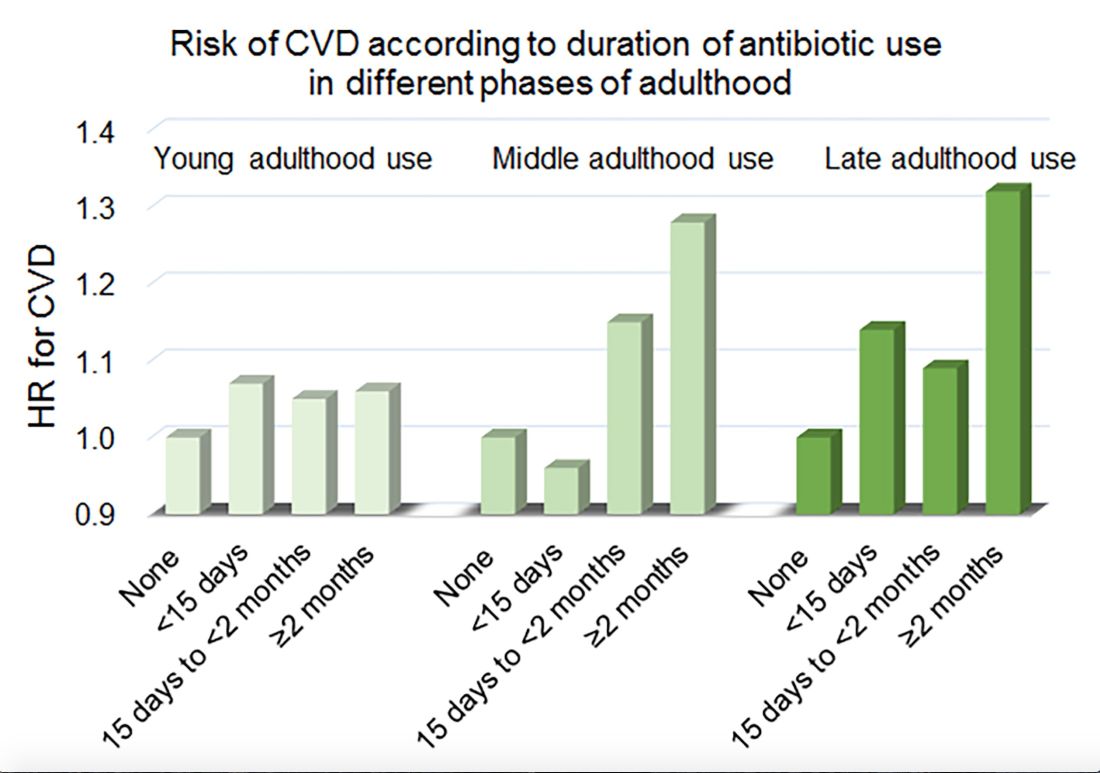

Women in the Nurses’ Health Study who used antibiotics for 2 or more months between ages 40 and 59 years or at age 60 years and older had a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease, compared with those who did not use antibiotics. Antibiotic use between 20 and 39 years old was not significantly related to cardiovascular disease.

Prior research has found that antibiotics may have long-lasting effects on gut microbiota and relate to cardiovascular disease risk.

“Antibiotic use is the most critical factor in altering the balance of microorganisms in the gut,” said lead investigator Lu Qi, MD, PhD, in a news release. “Previous studies have shown a link between alterations in the microbiotic environment of the gut and inflammation and narrowing of the blood vessels, stroke, and heart disease,” said Dr. Qi, who is the director of the Tulane University Obesity Research Center in New Orleans and an adjunct professor of nutrition at Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

To evaluate associations between life stage, antibiotic exposure, and subsequent cardiovascular disease, researchers analyzed data from 36,429 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study. The women were at least 60 years old and had no history of cardiovascular disease or cancer when they completed a 2004 questionnaire about antibiotic usage during young, middle, and late adulthood. The questionnaire asked participants to indicate the total time using antibiotics with eight categories ranging from none to 5 or more years.

The researchers defined incident cardiovascular disease as a composite endpoint of coronary heart disease (nonfatal myocardial infarction or fatal coronary heart disease) and stroke (nonfatal or fatal). They calculated person-years of follow-up from the questionnaire return date until date of cardiovascular disease diagnosis, death, or end of follow-up in 2012.

Women with longer duration of antibiotic use were more likely to use other medications and have unfavorable cardiovascular risk profiles, including family history of myocardial infarction and higher body mass index. Antibiotics most often were used to treat respiratory infections. During an average follow-up of 7.6 years, 1,056 participants developed cardiovascular disease.

In a multivariable model that adjusted for demographics, diet, lifestyle, reason for antibiotic use, medications, overweight status, and other factors, long-term antibiotic use – 2 months or more – in late adulthood was associated with significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 1.32), as was long-term antibiotic use in middle adulthood (HR, 1.28).

Although antibiotic use was self-reported, which could lead to misclassification, the participants were health professionals, which may mitigate this limitation, the authors noted. Whether these findings apply to men and other populations requires further study, they said.

Because of the study’s observational design, the results “cannot show that antibiotics cause heart disease and stroke, only that there is a link between them,” Dr. Qi said. “It’s possible that women who reported more antibiotic use might be sicker in other ways that we were unable to measure, or there may be other factors that could affect the results that we have not been able take account of.”

“Our study suggests that antibiotics should be used only when they are absolutely needed,” he concluded. “Considering the potentially cumulative adverse effects, the shorter time of antibiotic use the better.”

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants, the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center, and the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation. One author received support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Heianza Y et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz231.

, according to a study in the European Heart Journal.

Women in the Nurses’ Health Study who used antibiotics for 2 or more months between ages 40 and 59 years or at age 60 years and older had a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease, compared with those who did not use antibiotics. Antibiotic use between 20 and 39 years old was not significantly related to cardiovascular disease.

Prior research has found that antibiotics may have long-lasting effects on gut microbiota and relate to cardiovascular disease risk.

“Antibiotic use is the most critical factor in altering the balance of microorganisms in the gut,” said lead investigator Lu Qi, MD, PhD, in a news release. “Previous studies have shown a link between alterations in the microbiotic environment of the gut and inflammation and narrowing of the blood vessels, stroke, and heart disease,” said Dr. Qi, who is the director of the Tulane University Obesity Research Center in New Orleans and an adjunct professor of nutrition at Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

To evaluate associations between life stage, antibiotic exposure, and subsequent cardiovascular disease, researchers analyzed data from 36,429 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study. The women were at least 60 years old and had no history of cardiovascular disease or cancer when they completed a 2004 questionnaire about antibiotic usage during young, middle, and late adulthood. The questionnaire asked participants to indicate the total time using antibiotics with eight categories ranging from none to 5 or more years.

The researchers defined incident cardiovascular disease as a composite endpoint of coronary heart disease (nonfatal myocardial infarction or fatal coronary heart disease) and stroke (nonfatal or fatal). They calculated person-years of follow-up from the questionnaire return date until date of cardiovascular disease diagnosis, death, or end of follow-up in 2012.

Women with longer duration of antibiotic use were more likely to use other medications and have unfavorable cardiovascular risk profiles, including family history of myocardial infarction and higher body mass index. Antibiotics most often were used to treat respiratory infections. During an average follow-up of 7.6 years, 1,056 participants developed cardiovascular disease.

In a multivariable model that adjusted for demographics, diet, lifestyle, reason for antibiotic use, medications, overweight status, and other factors, long-term antibiotic use – 2 months or more – in late adulthood was associated with significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 1.32), as was long-term antibiotic use in middle adulthood (HR, 1.28).

Although antibiotic use was self-reported, which could lead to misclassification, the participants were health professionals, which may mitigate this limitation, the authors noted. Whether these findings apply to men and other populations requires further study, they said.

Because of the study’s observational design, the results “cannot show that antibiotics cause heart disease and stroke, only that there is a link between them,” Dr. Qi said. “It’s possible that women who reported more antibiotic use might be sicker in other ways that we were unable to measure, or there may be other factors that could affect the results that we have not been able take account of.”

“Our study suggests that antibiotics should be used only when they are absolutely needed,” he concluded. “Considering the potentially cumulative adverse effects, the shorter time of antibiotic use the better.”

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants, the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center, and the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation. One author received support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Heianza Y et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz231.

, according to a study in the European Heart Journal.

Women in the Nurses’ Health Study who used antibiotics for 2 or more months between ages 40 and 59 years or at age 60 years and older had a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease, compared with those who did not use antibiotics. Antibiotic use between 20 and 39 years old was not significantly related to cardiovascular disease.

Prior research has found that antibiotics may have long-lasting effects on gut microbiota and relate to cardiovascular disease risk.

“Antibiotic use is the most critical factor in altering the balance of microorganisms in the gut,” said lead investigator Lu Qi, MD, PhD, in a news release. “Previous studies have shown a link between alterations in the microbiotic environment of the gut and inflammation and narrowing of the blood vessels, stroke, and heart disease,” said Dr. Qi, who is the director of the Tulane University Obesity Research Center in New Orleans and an adjunct professor of nutrition at Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

To evaluate associations between life stage, antibiotic exposure, and subsequent cardiovascular disease, researchers analyzed data from 36,429 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study. The women were at least 60 years old and had no history of cardiovascular disease or cancer when they completed a 2004 questionnaire about antibiotic usage during young, middle, and late adulthood. The questionnaire asked participants to indicate the total time using antibiotics with eight categories ranging from none to 5 or more years.

The researchers defined incident cardiovascular disease as a composite endpoint of coronary heart disease (nonfatal myocardial infarction or fatal coronary heart disease) and stroke (nonfatal or fatal). They calculated person-years of follow-up from the questionnaire return date until date of cardiovascular disease diagnosis, death, or end of follow-up in 2012.

Women with longer duration of antibiotic use were more likely to use other medications and have unfavorable cardiovascular risk profiles, including family history of myocardial infarction and higher body mass index. Antibiotics most often were used to treat respiratory infections. During an average follow-up of 7.6 years, 1,056 participants developed cardiovascular disease.

In a multivariable model that adjusted for demographics, diet, lifestyle, reason for antibiotic use, medications, overweight status, and other factors, long-term antibiotic use – 2 months or more – in late adulthood was associated with significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 1.32), as was long-term antibiotic use in middle adulthood (HR, 1.28).

Although antibiotic use was self-reported, which could lead to misclassification, the participants were health professionals, which may mitigate this limitation, the authors noted. Whether these findings apply to men and other populations requires further study, they said.

Because of the study’s observational design, the results “cannot show that antibiotics cause heart disease and stroke, only that there is a link between them,” Dr. Qi said. “It’s possible that women who reported more antibiotic use might be sicker in other ways that we were unable to measure, or there may be other factors that could affect the results that we have not been able take account of.”

“Our study suggests that antibiotics should be used only when they are absolutely needed,” he concluded. “Considering the potentially cumulative adverse effects, the shorter time of antibiotic use the better.”

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants, the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center, and the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation. One author received support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Heianza Y et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz231.

FROM THE EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL

Key clinical point: Among middle-aged and older women, 2 or more months’ exposure to antibiotics is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease or stroke.

Major finding: Long-term antibiotic use in late adulthood was associated with significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 1.32), as was long-term antibiotic use in middle adulthood (HR, 1.28).

Study details: An analysis of data from nearly 36,500 women in the Nurses’ Health Study.

Disclosures: The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants, the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center, and the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation. One author received support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Heianza Y et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz231.

TMS is associated with improved recollection in older adults

according to a small pilot study published online ahead of print April 17 in Neurology. Stimulation also increased functional MRI signals associated with recollection throughout the hippocampal-cortical network.

“Disruption and abnormal functioning of the hippocampal-cortical network, the region of the brain involved in memory formation, has been linked to age-related memory decline, so it’s exciting to see that, by targeting this region, magnetic stimulation may help improve memory in older adults,” said Joel L. Voss, PhD, of Northwestern University in Chicago. “These results may help us better understand how this network supports memory.”

Recollection is the type of memory most impaired during normal aging. Other types of memory, such as recognition, are relatively spared. Research indicates that multiple sessions of TMS improve recollection and hippocampal-cortical network function in young adults.

Dr. Voss and colleagues performed a pilot study to evaluate whether TMS could improve recollection in older adults. They enrolled 15 cognitively normal older adults (mean age, 72.46 years) into a sham-controlled, single-blind, counterbalanced experiment. Eleven subjects were women. Participants underwent fMRI while learning objects paired with scenes and locations. Investigators administered TMS to lateral parietal locations that were based on each participant’s fMRI connectivity with the hippocampus. Using a within-subjects crossover design, Dr. Voss’s group assessed participants’ recollection and recognition memory at baseline and 24 hours and also 1 week after five consecutive daily sessions of full-intensity stimulation, compared with low-intensity sham stimulation.

At baseline, participants had impaired recollection, but not impaired recognition, compared with a historical sample of younger adults. At 24 hours, TMS provided robust recollection improvement and weak recognition improvement, compared with sham. TMS improved recollection by 31.1% from baseline, and sham yielded a nonsignificant change of −3.1%. Recollection improvements after TMS were consistent across participants. Recognition changed by a nonsignificant 2.8% following TMS and by a nonsignificant −2.9% following sham.

The investigators also found a significant and consistent increase in fMRI recollection activity for the targeted hippocampal-cortical network, but not for the control frontal-parietal network. They observed no increased fMRI activity for recognition.

“These findings demonstrate a causal link between recollection and the hippocampal-cortical network in older adults,” said Dr. Voss. “While our small study examined age-related memory loss, it did not examine this stimulation in people with memory loss from more serious conditions such as mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease.” Furthermore, the study was designed to test for neural and behavioral target engagement, but not clinical efficacy, he added.

The study’s limitations included its small sample size, its single-site design, and its lack of active control stimulation. Nevertheless, it identified specific and consistent effects of stimulation across participants that were consistent with previous findings in younger adults. “These findings motivate future studies to optimize the effectiveness of noninvasive stimulation for treatment of age-related memory impairment and to improve mechanistic understanding of the hippocampal-cortical networks that support episodic memory across the lifespan,” said Dr. Voss.

The National Institute on Aging, as well as the Northwestern University Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center, supported the study.

SOURCE: Nilakantan AS et al. Neurology. 2019 Apr 17 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007502.

according to a small pilot study published online ahead of print April 17 in Neurology. Stimulation also increased functional MRI signals associated with recollection throughout the hippocampal-cortical network.

“Disruption and abnormal functioning of the hippocampal-cortical network, the region of the brain involved in memory formation, has been linked to age-related memory decline, so it’s exciting to see that, by targeting this region, magnetic stimulation may help improve memory in older adults,” said Joel L. Voss, PhD, of Northwestern University in Chicago. “These results may help us better understand how this network supports memory.”

Recollection is the type of memory most impaired during normal aging. Other types of memory, such as recognition, are relatively spared. Research indicates that multiple sessions of TMS improve recollection and hippocampal-cortical network function in young adults.

Dr. Voss and colleagues performed a pilot study to evaluate whether TMS could improve recollection in older adults. They enrolled 15 cognitively normal older adults (mean age, 72.46 years) into a sham-controlled, single-blind, counterbalanced experiment. Eleven subjects were women. Participants underwent fMRI while learning objects paired with scenes and locations. Investigators administered TMS to lateral parietal locations that were based on each participant’s fMRI connectivity with the hippocampus. Using a within-subjects crossover design, Dr. Voss’s group assessed participants’ recollection and recognition memory at baseline and 24 hours and also 1 week after five consecutive daily sessions of full-intensity stimulation, compared with low-intensity sham stimulation.

At baseline, participants had impaired recollection, but not impaired recognition, compared with a historical sample of younger adults. At 24 hours, TMS provided robust recollection improvement and weak recognition improvement, compared with sham. TMS improved recollection by 31.1% from baseline, and sham yielded a nonsignificant change of −3.1%. Recollection improvements after TMS were consistent across participants. Recognition changed by a nonsignificant 2.8% following TMS and by a nonsignificant −2.9% following sham.

The investigators also found a significant and consistent increase in fMRI recollection activity for the targeted hippocampal-cortical network, but not for the control frontal-parietal network. They observed no increased fMRI activity for recognition.

“These findings demonstrate a causal link between recollection and the hippocampal-cortical network in older adults,” said Dr. Voss. “While our small study examined age-related memory loss, it did not examine this stimulation in people with memory loss from more serious conditions such as mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease.” Furthermore, the study was designed to test for neural and behavioral target engagement, but not clinical efficacy, he added.

The study’s limitations included its small sample size, its single-site design, and its lack of active control stimulation. Nevertheless, it identified specific and consistent effects of stimulation across participants that were consistent with previous findings in younger adults. “These findings motivate future studies to optimize the effectiveness of noninvasive stimulation for treatment of age-related memory impairment and to improve mechanistic understanding of the hippocampal-cortical networks that support episodic memory across the lifespan,” said Dr. Voss.

The National Institute on Aging, as well as the Northwestern University Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center, supported the study.

SOURCE: Nilakantan AS et al. Neurology. 2019 Apr 17 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007502.

according to a small pilot study published online ahead of print April 17 in Neurology. Stimulation also increased functional MRI signals associated with recollection throughout the hippocampal-cortical network.

“Disruption and abnormal functioning of the hippocampal-cortical network, the region of the brain involved in memory formation, has been linked to age-related memory decline, so it’s exciting to see that, by targeting this region, magnetic stimulation may help improve memory in older adults,” said Joel L. Voss, PhD, of Northwestern University in Chicago. “These results may help us better understand how this network supports memory.”

Recollection is the type of memory most impaired during normal aging. Other types of memory, such as recognition, are relatively spared. Research indicates that multiple sessions of TMS improve recollection and hippocampal-cortical network function in young adults.

Dr. Voss and colleagues performed a pilot study to evaluate whether TMS could improve recollection in older adults. They enrolled 15 cognitively normal older adults (mean age, 72.46 years) into a sham-controlled, single-blind, counterbalanced experiment. Eleven subjects were women. Participants underwent fMRI while learning objects paired with scenes and locations. Investigators administered TMS to lateral parietal locations that were based on each participant’s fMRI connectivity with the hippocampus. Using a within-subjects crossover design, Dr. Voss’s group assessed participants’ recollection and recognition memory at baseline and 24 hours and also 1 week after five consecutive daily sessions of full-intensity stimulation, compared with low-intensity sham stimulation.

At baseline, participants had impaired recollection, but not impaired recognition, compared with a historical sample of younger adults. At 24 hours, TMS provided robust recollection improvement and weak recognition improvement, compared with sham. TMS improved recollection by 31.1% from baseline, and sham yielded a nonsignificant change of −3.1%. Recollection improvements after TMS were consistent across participants. Recognition changed by a nonsignificant 2.8% following TMS and by a nonsignificant −2.9% following sham.

The investigators also found a significant and consistent increase in fMRI recollection activity for the targeted hippocampal-cortical network, but not for the control frontal-parietal network. They observed no increased fMRI activity for recognition.

“These findings demonstrate a causal link between recollection and the hippocampal-cortical network in older adults,” said Dr. Voss. “While our small study examined age-related memory loss, it did not examine this stimulation in people with memory loss from more serious conditions such as mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease.” Furthermore, the study was designed to test for neural and behavioral target engagement, but not clinical efficacy, he added.

The study’s limitations included its small sample size, its single-site design, and its lack of active control stimulation. Nevertheless, it identified specific and consistent effects of stimulation across participants that were consistent with previous findings in younger adults. “These findings motivate future studies to optimize the effectiveness of noninvasive stimulation for treatment of age-related memory impairment and to improve mechanistic understanding of the hippocampal-cortical networks that support episodic memory across the lifespan,” said Dr. Voss.

The National Institute on Aging, as well as the Northwestern University Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center, supported the study.

SOURCE: Nilakantan AS et al. Neurology. 2019 Apr 17 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007502.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Plasma levels of neurofilament light track neurodegeneration in MCI and Alzheimer’s disease

Plasma levels of the axonal protein also correlated with its presence in cerebrospinal fluid, and mirrored the changes in amyloid beta (Abeta) 42, Niklas Mattsson, MD, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Neurology.

“Taken together, these findings suggest that the neurofilament light level is a dynamic biomarker that changes throughout the course of Alzheimer’s disease and is sensitive to progressive neurodegeneration,” wrote Dr. Mattsson of Lund (Sweden) University and his coauthors. “This has important implications, given the unmet need for noninvasive blood-based methods to objectively track longitudinal neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease.”

A blood-based biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease progression could open a new door for drug trials, the authors noted. Previously, NfL levels have only been available by lumbar puncture – a invasive and expensive test that many patients resist. If NfL plasma levels do reliably track dementia progression, the test could become a standard part of clinical trials, providing regular drug response data as the study progresses.

Neurofilaments are polypeptides that give structure to the neuronal cytoskeleton and regulate microtubule function. Injured cells release the protein very quickly. Neurofilaments are elevated in traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, and some psychiatric illnesses. Neurofilament levels have even been used to predict neurologic recovery after cardiac arrest.

Dr. Mattsson and his team used data obtained over 11 years from 1,583 subjects enrolled in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study. The sample comprised three groups: cognitively unimpaired controls (401), patients with MCI (855), and patients with Alzheimer’s dementia (327). The investigators analyzed 4,326 samples.

In addition to the NfL measurements, they tracked Abeta and tau in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), structural brain changes by 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET and MRI, and cognitive and functional performance. The primary outcome was NfL’s association with these changes. The team set the lower limit of NfL as 6.7 ng/L and the upper, 1,620 ng/L.

At baseline, only advancing age correlated with NfL levels. But it was significantly higher in patients with MCI (37.9 ng/L) and Alzheimer’s dementia (45.9 ng/L) than it was in the control subjects (32.1 ng/L). Over the years of follow-up, levels increased in all groups, but NfL increased more rapidly among patients with MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia than controls (2.7 vs. 2.4 ng/L per year). The difference was most pronounced when comparing levels in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI with controls. However, control subjects who were Abeta positive by CSF had greater NfL changes than Abeta-negative controls.

Baseline measures of CSF Abeta and tau, as well as hippocampal and ventricular volume and cortical thickness, also correlated with NfL levels, as did cognition and functional scores.

During follow-up, the diagnostic groups showed different NfL trajectories, which correlated strongly with the other measures.

In the control group, NfL increases correlated with lower FDG-PET measures, lower CSF Abeta, reduced hippocampal volume, and higher ventricular volume. Among patients with MCI, NfL increases correlated most strongly with hippocampal volume, temporal region, and cognition. Among patients with Alzheimer’s dementia, the NfL increase most strongly tracked cognitive decline,

When the investigators applied these findings to the A/T/N (amyloid, tau, neurodegeneration) classification system, NfL most often correlated with neurodegeneration, but not always. This might suggest that the neuronal damage occurred separately from Abeta changes. In all three groups, rapid NfL increases mirrored the rate of change in most other measures.

“In controls and patients with MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia, greater rates of NfL were associated with accelerated reduction in FDG-PET measures … expansion of ventricular volume,” and a reduction in cognitive and functional performance, Dr. Mattsson and his colleagues wrote.“ In addition, greater increases in NfL levels were associated with accelerated loss of hippocampal volume and entorhinal cortical thickness in controls and patients with MCI and with accelerated increases in total tau level, phosphorylated tau level, and white matter lesions in patients with MCI. In general, the concentrations of blood-based NfL appears to reflect the intensity of the neuronal injury.”

Dr Mattsson reported being a consultant for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

SOURCE: Mattsson N et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0765.

This is an impressive study that convincingly demonstrates the sensitivity of plasma neurofilament light (NfL) to disease progression in patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort.

It is known that NfL is sensitive to neuronal damage that can result from a variety of pathologies, not limited to Alzheimer’s disease, so it is not diagnostically specific. In the present study there was even overlap of values between the cognitively unimpaired and mild cognitive impairment groups at baseline as well, although the levels separated over time.

In the right setting, NfL might still be a clinically useful diagnostic marker, especially for mild-stage disease when other clinical measures such as mental status scores and structural brain scans are inconclusive, and further study seems warranted for such a possibility.

Its greatest utility, however, will likely be in clinical trials. It would have been of the greatest interest to know how NfL levels changed in the setting of demonstrated cerebral amyloid clearance by agents such as aducanumab that failed to halt dementia progression, or in the setting of BACE1 inhibitor-related worsening of cognition. Did NfL levels remain static in the former and rise in the latter? Looking ahead, it seems likely that this easily accessed biomarker will become an integral part of clinical trial design. Assuming cost is not overly burdensome, it may even find its way eventually into clinical practice.

Dr. Caselli is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale and associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

This is an impressive study that convincingly demonstrates the sensitivity of plasma neurofilament light (NfL) to disease progression in patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort.

It is known that NfL is sensitive to neuronal damage that can result from a variety of pathologies, not limited to Alzheimer’s disease, so it is not diagnostically specific. In the present study there was even overlap of values between the cognitively unimpaired and mild cognitive impairment groups at baseline as well, although the levels separated over time.

In the right setting, NfL might still be a clinically useful diagnostic marker, especially for mild-stage disease when other clinical measures such as mental status scores and structural brain scans are inconclusive, and further study seems warranted for such a possibility.

Its greatest utility, however, will likely be in clinical trials. It would have been of the greatest interest to know how NfL levels changed in the setting of demonstrated cerebral amyloid clearance by agents such as aducanumab that failed to halt dementia progression, or in the setting of BACE1 inhibitor-related worsening of cognition. Did NfL levels remain static in the former and rise in the latter? Looking ahead, it seems likely that this easily accessed biomarker will become an integral part of clinical trial design. Assuming cost is not overly burdensome, it may even find its way eventually into clinical practice.

Dr. Caselli is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale and associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

This is an impressive study that convincingly demonstrates the sensitivity of plasma neurofilament light (NfL) to disease progression in patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort.

It is known that NfL is sensitive to neuronal damage that can result from a variety of pathologies, not limited to Alzheimer’s disease, so it is not diagnostically specific. In the present study there was even overlap of values between the cognitively unimpaired and mild cognitive impairment groups at baseline as well, although the levels separated over time.

In the right setting, NfL might still be a clinically useful diagnostic marker, especially for mild-stage disease when other clinical measures such as mental status scores and structural brain scans are inconclusive, and further study seems warranted for such a possibility.

Its greatest utility, however, will likely be in clinical trials. It would have been of the greatest interest to know how NfL levels changed in the setting of demonstrated cerebral amyloid clearance by agents such as aducanumab that failed to halt dementia progression, or in the setting of BACE1 inhibitor-related worsening of cognition. Did NfL levels remain static in the former and rise in the latter? Looking ahead, it seems likely that this easily accessed biomarker will become an integral part of clinical trial design. Assuming cost is not overly burdensome, it may even find its way eventually into clinical practice.

Dr. Caselli is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale and associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

Plasma levels of the axonal protein also correlated with its presence in cerebrospinal fluid, and mirrored the changes in amyloid beta (Abeta) 42, Niklas Mattsson, MD, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Neurology.

“Taken together, these findings suggest that the neurofilament light level is a dynamic biomarker that changes throughout the course of Alzheimer’s disease and is sensitive to progressive neurodegeneration,” wrote Dr. Mattsson of Lund (Sweden) University and his coauthors. “This has important implications, given the unmet need for noninvasive blood-based methods to objectively track longitudinal neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease.”

A blood-based biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease progression could open a new door for drug trials, the authors noted. Previously, NfL levels have only been available by lumbar puncture – a invasive and expensive test that many patients resist. If NfL plasma levels do reliably track dementia progression, the test could become a standard part of clinical trials, providing regular drug response data as the study progresses.

Neurofilaments are polypeptides that give structure to the neuronal cytoskeleton and regulate microtubule function. Injured cells release the protein very quickly. Neurofilaments are elevated in traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, and some psychiatric illnesses. Neurofilament levels have even been used to predict neurologic recovery after cardiac arrest.

Dr. Mattsson and his team used data obtained over 11 years from 1,583 subjects enrolled in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study. The sample comprised three groups: cognitively unimpaired controls (401), patients with MCI (855), and patients with Alzheimer’s dementia (327). The investigators analyzed 4,326 samples.

In addition to the NfL measurements, they tracked Abeta and tau in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), structural brain changes by 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET and MRI, and cognitive and functional performance. The primary outcome was NfL’s association with these changes. The team set the lower limit of NfL as 6.7 ng/L and the upper, 1,620 ng/L.

At baseline, only advancing age correlated with NfL levels. But it was significantly higher in patients with MCI (37.9 ng/L) and Alzheimer’s dementia (45.9 ng/L) than it was in the control subjects (32.1 ng/L). Over the years of follow-up, levels increased in all groups, but NfL increased more rapidly among patients with MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia than controls (2.7 vs. 2.4 ng/L per year). The difference was most pronounced when comparing levels in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI with controls. However, control subjects who were Abeta positive by CSF had greater NfL changes than Abeta-negative controls.

Baseline measures of CSF Abeta and tau, as well as hippocampal and ventricular volume and cortical thickness, also correlated with NfL levels, as did cognition and functional scores.

During follow-up, the diagnostic groups showed different NfL trajectories, which correlated strongly with the other measures.

In the control group, NfL increases correlated with lower FDG-PET measures, lower CSF Abeta, reduced hippocampal volume, and higher ventricular volume. Among patients with MCI, NfL increases correlated most strongly with hippocampal volume, temporal region, and cognition. Among patients with Alzheimer’s dementia, the NfL increase most strongly tracked cognitive decline,

When the investigators applied these findings to the A/T/N (amyloid, tau, neurodegeneration) classification system, NfL most often correlated with neurodegeneration, but not always. This might suggest that the neuronal damage occurred separately from Abeta changes. In all three groups, rapid NfL increases mirrored the rate of change in most other measures.

“In controls and patients with MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia, greater rates of NfL were associated with accelerated reduction in FDG-PET measures … expansion of ventricular volume,” and a reduction in cognitive and functional performance, Dr. Mattsson and his colleagues wrote.“ In addition, greater increases in NfL levels were associated with accelerated loss of hippocampal volume and entorhinal cortical thickness in controls and patients with MCI and with accelerated increases in total tau level, phosphorylated tau level, and white matter lesions in patients with MCI. In general, the concentrations of blood-based NfL appears to reflect the intensity of the neuronal injury.”

Dr Mattsson reported being a consultant for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

SOURCE: Mattsson N et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0765.

Plasma levels of the axonal protein also correlated with its presence in cerebrospinal fluid, and mirrored the changes in amyloid beta (Abeta) 42, Niklas Mattsson, MD, and colleagues wrote in JAMA Neurology.

“Taken together, these findings suggest that the neurofilament light level is a dynamic biomarker that changes throughout the course of Alzheimer’s disease and is sensitive to progressive neurodegeneration,” wrote Dr. Mattsson of Lund (Sweden) University and his coauthors. “This has important implications, given the unmet need for noninvasive blood-based methods to objectively track longitudinal neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease.”

A blood-based biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease progression could open a new door for drug trials, the authors noted. Previously, NfL levels have only been available by lumbar puncture – a invasive and expensive test that many patients resist. If NfL plasma levels do reliably track dementia progression, the test could become a standard part of clinical trials, providing regular drug response data as the study progresses.

Neurofilaments are polypeptides that give structure to the neuronal cytoskeleton and regulate microtubule function. Injured cells release the protein very quickly. Neurofilaments are elevated in traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, and some psychiatric illnesses. Neurofilament levels have even been used to predict neurologic recovery after cardiac arrest.

Dr. Mattsson and his team used data obtained over 11 years from 1,583 subjects enrolled in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative study. The sample comprised three groups: cognitively unimpaired controls (401), patients with MCI (855), and patients with Alzheimer’s dementia (327). The investigators analyzed 4,326 samples.

In addition to the NfL measurements, they tracked Abeta and tau in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), structural brain changes by 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–PET and MRI, and cognitive and functional performance. The primary outcome was NfL’s association with these changes. The team set the lower limit of NfL as 6.7 ng/L and the upper, 1,620 ng/L.

At baseline, only advancing age correlated with NfL levels. But it was significantly higher in patients with MCI (37.9 ng/L) and Alzheimer’s dementia (45.9 ng/L) than it was in the control subjects (32.1 ng/L). Over the years of follow-up, levels increased in all groups, but NfL increased more rapidly among patients with MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia than controls (2.7 vs. 2.4 ng/L per year). The difference was most pronounced when comparing levels in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI with controls. However, control subjects who were Abeta positive by CSF had greater NfL changes than Abeta-negative controls.

Baseline measures of CSF Abeta and tau, as well as hippocampal and ventricular volume and cortical thickness, also correlated with NfL levels, as did cognition and functional scores.

During follow-up, the diagnostic groups showed different NfL trajectories, which correlated strongly with the other measures.

In the control group, NfL increases correlated with lower FDG-PET measures, lower CSF Abeta, reduced hippocampal volume, and higher ventricular volume. Among patients with MCI, NfL increases correlated most strongly with hippocampal volume, temporal region, and cognition. Among patients with Alzheimer’s dementia, the NfL increase most strongly tracked cognitive decline,

When the investigators applied these findings to the A/T/N (amyloid, tau, neurodegeneration) classification system, NfL most often correlated with neurodegeneration, but not always. This might suggest that the neuronal damage occurred separately from Abeta changes. In all three groups, rapid NfL increases mirrored the rate of change in most other measures.

“In controls and patients with MCI and Alzheimer’s dementia, greater rates of NfL were associated with accelerated reduction in FDG-PET measures … expansion of ventricular volume,” and a reduction in cognitive and functional performance, Dr. Mattsson and his colleagues wrote.“ In addition, greater increases in NfL levels were associated with accelerated loss of hippocampal volume and entorhinal cortical thickness in controls and patients with MCI and with accelerated increases in total tau level, phosphorylated tau level, and white matter lesions in patients with MCI. In general, the concentrations of blood-based NfL appears to reflect the intensity of the neuronal injury.”

Dr Mattsson reported being a consultant for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

SOURCE: Mattsson N et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 22. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0765.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Can immune checkpoint inhibitors treat PML?

investigators reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Three research teams described 10 cases in which patients with PML received pembrolizumab or nivolumab.

In one study, researchers administered pembrolizumab to eight adults with PML. Five patients had clinical improvement or stabilization, whereas 3 patients did not. Among the patients with clinical improvement, treatment led to reduced JC viral load in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and increased CD4+ and CD8+ anti–JC virus activity in vitro. Among patients without clinical improvement, treatment did not meaningfully change viral load or antiviral cellular immune response.

In a separate letter, researchers in Germany described an additional patient with PML who had clinical stabilization and no disease progression on MRI after treatment with pembrolizumab.

In another letter, researchers in France described a patient with PML whose condition improved after treatment with nivolumab.

“Do pembrolizumab and nivolumab fit the bill for treatment of PML? The current reports are encouraging but suggest that the presence of JC virus–specific T cells in the blood is a prerequisite for their use,” said Igor J. Koralnik, MD, of the department of neurological sciences at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, in an accompanying editorial. “A controlled trial may be needed to determine whether immune checkpoint inhibitors are indeed able to keep JC virus in check in patients with PML.”

Reinvigorating T cells

Both monoclonal antibodies target programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), which inhibits T-cell proliferation and cytokine production when it binds its associated ligand, Dr. Koralnik said. Pembrolizumab and nivolumab block this inhibition and have been used to spur T-cell activity against tumors in patients with cancer.

PML, an often fatal brain infection caused by the JC virus in patients with immunosuppression, has no specific treatment. Management hinges on “recovery of the immune system, either by treating the underlying cause of immunosuppression or by discontinuing the use of immunosuppressive medications,” said Dr. Koralnik.

Pembrolizumab

Prior studies have found that PD-1 expression is elevated on T lymphocytes of patients with PML. To determine whether PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab reinvigorates anti–JC virus immune activity in patients with PML, Irene Cortese, MD, of the National Institutes of Health’s Neuroimmunology Clinic and her research colleagues administered pembrolizumab at a dose of 2 mg/kg of body weight every 4-6 weeks to eight adults with PML. The patients received 1-3 doses, and each patient had a different underlying condition.

In all patients, treatment induced down-regulation of PD-1 expression on lymphocytes in CSF and peripheral blood, and five of the eight patients had clinical stabilization or improvement. Of the other three patients who did not improve, one had stabilized prior to treatment and remained stable. The other two patients died from PML.

Additional reports

Separately, Sebastian Rauer, MD, of Albert Ludwigs University in Freiburg, Germany, and his colleagues reported that a patient with PML whose symptoms culminated in mutism in February 2018 began speaking again after receiving five infusions of pembrolizumab over 10 weeks. “In addition, the size and number of lesions on MRI decreased, and JCV was no longer detectable in CSF,” Dr. Rauer and his colleagues wrote. “The patient has remained stable as of the end of March 2019, with persistent but abating psychomotor slowing, aphasia, and disorientation.”