User login

The Essential Guide to Estate Planning for Physicians: Securing Your Legacy and Protecting Your Wealth

As a physician, you’ve spent years building a career that not only provides financial security for your family but also allows you to make a meaningful impact in your community. However, without a comprehensive estate plan in place, much of what you’ve worked so hard to build may not be preserved according to your wishes.

Many physicians delay estate planning, assuming it’s something to consider later in life. However, the most successful estate plans are those that are established early and evolve over time. Proper planning ensures that your assets are protected, your loved ones are provided for, and your legacy is preserved in the most tax-efficient and legally-sound manner possible.1

This article explores why estate planning is particularly crucial for physicians, the key elements of a strong estate plan, and how beginning early can create long-term financial advantages.

Why Estate Planning Matters for Physicians

Physicians are in a unique financial position compared to many other professionals. With high earning potential, specialized assets, and significant liability exposure, their estate planning needs differ from those of the average individual. A well-structured estate plan not only facilitates the smooth transfer of wealth but also protects assets from excessive taxation, legal complications, and potential risks such as malpractice claims.

1. High Net-Worth Considerations

Physicians often accumulate substantial wealth over time. Without a clear estate plan, your estate could face excessive taxation, with a large portion of your assets potentially going to the government rather than your heirs. Estate taxes, probate costs, and legal fees can significantly erode your legacy if not properly planned for.

2. Asset Protection from Liability Risks

Unlike most professionals, physicians are at a higher risk of litigation. A comprehensive estate plan can incorporate asset protection strategies, such as irrevocable trusts, family limited partnerships, or liability insurance, to shield your wealth from lawsuits or creditor claims.

3. Family and Generational Wealth Planning

Many physicians prioritize ensuring their family’s financial stability. Whether you want to provide for your spouse, children, or even charitable causes, estate planning allows you to dictate how your wealth is distributed. Establishing trusts for your children or grandchildren can help manage how and when they receive their inheritance, preventing mismanagement and ensuring financial responsibility.

4. Business and Practice Continuity

If you own a medical practice, succession planning should be part of your estate plan. Without clear directives, the future of your practice may be uncertain in the event of your passing or incapacitation. A well-drafted estate plan provides a roadmap for ownership transition, ensuring continuity for patients, employees, and business partners.

Key Elements of an Effective Estate Plan

Every estate plan should be customized based on your financial situation, goals, and family dynamics. However, certain fundamental components apply to nearly all high-net-worth individuals, including physicians.

1. Revocable Living Trusts

A revocable living trust allows you to manage your assets during your lifetime while providing a clear path for distribution after your passing. Unlike a will, a trust helps your estate avoid probate, ensuring a smoother and more private transition of wealth. You maintain control over your assets while also establishing clear rules for distribution, particularly useful if you have minor children or complex family structures.2

2. Irrevocable Trusts for Asset Protection

For physicians concerned about lawsuits or estate tax exposure, irrevocable trusts can offer robust asset protection. Since assets placed in these trusts are no longer legally owned by you, they are shielded from creditors and legal claims while also reducing your taxable estate.2

3. Powers of Attorney and Healthcare Directives

Estate planning isn’t just about what happens after your passing—it’s also about protecting you and your family if you become incapacitated. A durable power of attorney allows a trusted individual to manage your financial affairs, while a healthcare directive ensures your medical decisions align with your wishes.3

4. Life Insurance Planning

Life insurance is an essential estate planning tool for physicians, providing liquidity to cover estate taxes, debts, or income replacement for your family. A properly structured life insurance trust can help ensure that policy proceeds remain outside of your taxable estate while being efficiently distributed according to your wishes.4

5. Business Succession Planning

If you own a medical practice, a well-designed succession plan can ensure that your business continues to operate smoothly in your absence. This may involve buy-sell agreements, key-person insurance, or identifying a successor to take over your role.5

The Long-Term Benefits of Early Estate Planning

Estate planning is not a one-time event—it’s a process that should evolve with your career, financial growth, and family dynamics. The earlier you begin, the more control you have over your financial future. Here’s why starting early is a strategic advantage:

1. Maximizing Tax Efficiency

Many estate planning strategies, such as gifting assets or establishing irrevocable trusts, are most effective when implemented over time. By spreading out wealth transfers and taking advantage of annual gift exclusions, you can significantly reduce estate tax liability while maintaining financial security.

2. Adjusting for Life Changes

Your financial situation and family needs will change over the years. Marriages, births, career advancements, and new investments all impact your estate planning needs. By starting early, you can make gradual adjustments rather than facing an overwhelming restructuring later in life.1

3. Ensuring Asset Protection Strategies Are in Place

Many asset protection strategies require time to be effective. For instance, certain types of trusts must be in place for a number of years before they fully shield assets from legal claims. Delaying planning could leave your wealth unnecessarily exposed.

4. Creating a Legacy Beyond Wealth

Estate planning is not just about finances—it’s about legacy. Whether you want to support a charitable cause, endow a scholarship, or establish a foundation, early planning gives you the ability to shape your long-term impact.

5. Adapt to Ever Changing Legislation

Estate planning needs to be adaptable. The federal government can change the estate tax exemption at any time; this was even a topic of the last election cycle. Early planning allows you to implement necessary changes throughout your life to minimize estate taxes. At present, unless new policy is enacted, the exemption per individual will reduce by half in 2026 (see Figure 1).

Final Thoughts: Taking Action Today

The complexity of physician finances—ranging from high income and significant assets to legal risks—makes individualized estate planning an absolute necessity.

By taking proactive steps today, you can maximize tax efficiency, safeguard your assets, and ensure your wishes are carried out without unnecessary delays or legal battles. Working with a financial advisor and estate planning attorney who understands the unique needs of physicians can help you craft a plan that aligns with your goals and evolves as your career progresses.

Mr. Gardner is a financial advisor at Lifetime Financial Growth, LLC, in Columbus, Ohio, one of the largest privately held wealth management firms in the country. John has had a passion for finance since his early years in college when his tennis coach introduced him. He also has a passion for helping physicians, as his wife is a gastroenterologist at Ohio State University. He reports no relevant disclosures relevant to this article. If you have additional questions, please contact John at 740-403-4891 or john_s_gardner@glic.com.

References

1. The Law Offices of Diron Rutty, LLC. https://www.dironruttyllc.com/reasons-to-start-estate-planning-early/.

2. Physician Side Gigs. https://www.physiciansidegigs.com/estateplanning.

3. Afshar, A & MacBeth, S. https://www.schwabe.com/publication/estate-planning-for-physicians-why-its-important-and-how-to-get-started/. December 2024.

4. Skeeles, JC. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/ep-1. July 2012.

5. Rosenfeld, J. Physician estate planning guide. Medical Economics. 2022 Nov. https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/physician-estate-planning-guide.

As a physician, you’ve spent years building a career that not only provides financial security for your family but also allows you to make a meaningful impact in your community. However, without a comprehensive estate plan in place, much of what you’ve worked so hard to build may not be preserved according to your wishes.

Many physicians delay estate planning, assuming it’s something to consider later in life. However, the most successful estate plans are those that are established early and evolve over time. Proper planning ensures that your assets are protected, your loved ones are provided for, and your legacy is preserved in the most tax-efficient and legally-sound manner possible.1

This article explores why estate planning is particularly crucial for physicians, the key elements of a strong estate plan, and how beginning early can create long-term financial advantages.

Why Estate Planning Matters for Physicians

Physicians are in a unique financial position compared to many other professionals. With high earning potential, specialized assets, and significant liability exposure, their estate planning needs differ from those of the average individual. A well-structured estate plan not only facilitates the smooth transfer of wealth but also protects assets from excessive taxation, legal complications, and potential risks such as malpractice claims.

1. High Net-Worth Considerations

Physicians often accumulate substantial wealth over time. Without a clear estate plan, your estate could face excessive taxation, with a large portion of your assets potentially going to the government rather than your heirs. Estate taxes, probate costs, and legal fees can significantly erode your legacy if not properly planned for.

2. Asset Protection from Liability Risks

Unlike most professionals, physicians are at a higher risk of litigation. A comprehensive estate plan can incorporate asset protection strategies, such as irrevocable trusts, family limited partnerships, or liability insurance, to shield your wealth from lawsuits or creditor claims.

3. Family and Generational Wealth Planning

Many physicians prioritize ensuring their family’s financial stability. Whether you want to provide for your spouse, children, or even charitable causes, estate planning allows you to dictate how your wealth is distributed. Establishing trusts for your children or grandchildren can help manage how and when they receive their inheritance, preventing mismanagement and ensuring financial responsibility.

4. Business and Practice Continuity

If you own a medical practice, succession planning should be part of your estate plan. Without clear directives, the future of your practice may be uncertain in the event of your passing or incapacitation. A well-drafted estate plan provides a roadmap for ownership transition, ensuring continuity for patients, employees, and business partners.

Key Elements of an Effective Estate Plan

Every estate plan should be customized based on your financial situation, goals, and family dynamics. However, certain fundamental components apply to nearly all high-net-worth individuals, including physicians.

1. Revocable Living Trusts

A revocable living trust allows you to manage your assets during your lifetime while providing a clear path for distribution after your passing. Unlike a will, a trust helps your estate avoid probate, ensuring a smoother and more private transition of wealth. You maintain control over your assets while also establishing clear rules for distribution, particularly useful if you have minor children or complex family structures.2

2. Irrevocable Trusts for Asset Protection

For physicians concerned about lawsuits or estate tax exposure, irrevocable trusts can offer robust asset protection. Since assets placed in these trusts are no longer legally owned by you, they are shielded from creditors and legal claims while also reducing your taxable estate.2

3. Powers of Attorney and Healthcare Directives

Estate planning isn’t just about what happens after your passing—it’s also about protecting you and your family if you become incapacitated. A durable power of attorney allows a trusted individual to manage your financial affairs, while a healthcare directive ensures your medical decisions align with your wishes.3

4. Life Insurance Planning

Life insurance is an essential estate planning tool for physicians, providing liquidity to cover estate taxes, debts, or income replacement for your family. A properly structured life insurance trust can help ensure that policy proceeds remain outside of your taxable estate while being efficiently distributed according to your wishes.4

5. Business Succession Planning

If you own a medical practice, a well-designed succession plan can ensure that your business continues to operate smoothly in your absence. This may involve buy-sell agreements, key-person insurance, or identifying a successor to take over your role.5

The Long-Term Benefits of Early Estate Planning

Estate planning is not a one-time event—it’s a process that should evolve with your career, financial growth, and family dynamics. The earlier you begin, the more control you have over your financial future. Here’s why starting early is a strategic advantage:

1. Maximizing Tax Efficiency

Many estate planning strategies, such as gifting assets or establishing irrevocable trusts, are most effective when implemented over time. By spreading out wealth transfers and taking advantage of annual gift exclusions, you can significantly reduce estate tax liability while maintaining financial security.

2. Adjusting for Life Changes

Your financial situation and family needs will change over the years. Marriages, births, career advancements, and new investments all impact your estate planning needs. By starting early, you can make gradual adjustments rather than facing an overwhelming restructuring later in life.1

3. Ensuring Asset Protection Strategies Are in Place

Many asset protection strategies require time to be effective. For instance, certain types of trusts must be in place for a number of years before they fully shield assets from legal claims. Delaying planning could leave your wealth unnecessarily exposed.

4. Creating a Legacy Beyond Wealth

Estate planning is not just about finances—it’s about legacy. Whether you want to support a charitable cause, endow a scholarship, or establish a foundation, early planning gives you the ability to shape your long-term impact.

5. Adapt to Ever Changing Legislation

Estate planning needs to be adaptable. The federal government can change the estate tax exemption at any time; this was even a topic of the last election cycle. Early planning allows you to implement necessary changes throughout your life to minimize estate taxes. At present, unless new policy is enacted, the exemption per individual will reduce by half in 2026 (see Figure 1).

Final Thoughts: Taking Action Today

The complexity of physician finances—ranging from high income and significant assets to legal risks—makes individualized estate planning an absolute necessity.

By taking proactive steps today, you can maximize tax efficiency, safeguard your assets, and ensure your wishes are carried out without unnecessary delays or legal battles. Working with a financial advisor and estate planning attorney who understands the unique needs of physicians can help you craft a plan that aligns with your goals and evolves as your career progresses.

Mr. Gardner is a financial advisor at Lifetime Financial Growth, LLC, in Columbus, Ohio, one of the largest privately held wealth management firms in the country. John has had a passion for finance since his early years in college when his tennis coach introduced him. He also has a passion for helping physicians, as his wife is a gastroenterologist at Ohio State University. He reports no relevant disclosures relevant to this article. If you have additional questions, please contact John at 740-403-4891 or john_s_gardner@glic.com.

References

1. The Law Offices of Diron Rutty, LLC. https://www.dironruttyllc.com/reasons-to-start-estate-planning-early/.

2. Physician Side Gigs. https://www.physiciansidegigs.com/estateplanning.

3. Afshar, A & MacBeth, S. https://www.schwabe.com/publication/estate-planning-for-physicians-why-its-important-and-how-to-get-started/. December 2024.

4. Skeeles, JC. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/ep-1. July 2012.

5. Rosenfeld, J. Physician estate planning guide. Medical Economics. 2022 Nov. https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/physician-estate-planning-guide.

As a physician, you’ve spent years building a career that not only provides financial security for your family but also allows you to make a meaningful impact in your community. However, without a comprehensive estate plan in place, much of what you’ve worked so hard to build may not be preserved according to your wishes.

Many physicians delay estate planning, assuming it’s something to consider later in life. However, the most successful estate plans are those that are established early and evolve over time. Proper planning ensures that your assets are protected, your loved ones are provided for, and your legacy is preserved in the most tax-efficient and legally-sound manner possible.1

This article explores why estate planning is particularly crucial for physicians, the key elements of a strong estate plan, and how beginning early can create long-term financial advantages.

Why Estate Planning Matters for Physicians

Physicians are in a unique financial position compared to many other professionals. With high earning potential, specialized assets, and significant liability exposure, their estate planning needs differ from those of the average individual. A well-structured estate plan not only facilitates the smooth transfer of wealth but also protects assets from excessive taxation, legal complications, and potential risks such as malpractice claims.

1. High Net-Worth Considerations

Physicians often accumulate substantial wealth over time. Without a clear estate plan, your estate could face excessive taxation, with a large portion of your assets potentially going to the government rather than your heirs. Estate taxes, probate costs, and legal fees can significantly erode your legacy if not properly planned for.

2. Asset Protection from Liability Risks

Unlike most professionals, physicians are at a higher risk of litigation. A comprehensive estate plan can incorporate asset protection strategies, such as irrevocable trusts, family limited partnerships, or liability insurance, to shield your wealth from lawsuits or creditor claims.

3. Family and Generational Wealth Planning

Many physicians prioritize ensuring their family’s financial stability. Whether you want to provide for your spouse, children, or even charitable causes, estate planning allows you to dictate how your wealth is distributed. Establishing trusts for your children or grandchildren can help manage how and when they receive their inheritance, preventing mismanagement and ensuring financial responsibility.

4. Business and Practice Continuity

If you own a medical practice, succession planning should be part of your estate plan. Without clear directives, the future of your practice may be uncertain in the event of your passing or incapacitation. A well-drafted estate plan provides a roadmap for ownership transition, ensuring continuity for patients, employees, and business partners.

Key Elements of an Effective Estate Plan

Every estate plan should be customized based on your financial situation, goals, and family dynamics. However, certain fundamental components apply to nearly all high-net-worth individuals, including physicians.

1. Revocable Living Trusts

A revocable living trust allows you to manage your assets during your lifetime while providing a clear path for distribution after your passing. Unlike a will, a trust helps your estate avoid probate, ensuring a smoother and more private transition of wealth. You maintain control over your assets while also establishing clear rules for distribution, particularly useful if you have minor children or complex family structures.2

2. Irrevocable Trusts for Asset Protection

For physicians concerned about lawsuits or estate tax exposure, irrevocable trusts can offer robust asset protection. Since assets placed in these trusts are no longer legally owned by you, they are shielded from creditors and legal claims while also reducing your taxable estate.2

3. Powers of Attorney and Healthcare Directives

Estate planning isn’t just about what happens after your passing—it’s also about protecting you and your family if you become incapacitated. A durable power of attorney allows a trusted individual to manage your financial affairs, while a healthcare directive ensures your medical decisions align with your wishes.3

4. Life Insurance Planning

Life insurance is an essential estate planning tool for physicians, providing liquidity to cover estate taxes, debts, or income replacement for your family. A properly structured life insurance trust can help ensure that policy proceeds remain outside of your taxable estate while being efficiently distributed according to your wishes.4

5. Business Succession Planning

If you own a medical practice, a well-designed succession plan can ensure that your business continues to operate smoothly in your absence. This may involve buy-sell agreements, key-person insurance, or identifying a successor to take over your role.5

The Long-Term Benefits of Early Estate Planning

Estate planning is not a one-time event—it’s a process that should evolve with your career, financial growth, and family dynamics. The earlier you begin, the more control you have over your financial future. Here’s why starting early is a strategic advantage:

1. Maximizing Tax Efficiency

Many estate planning strategies, such as gifting assets or establishing irrevocable trusts, are most effective when implemented over time. By spreading out wealth transfers and taking advantage of annual gift exclusions, you can significantly reduce estate tax liability while maintaining financial security.

2. Adjusting for Life Changes

Your financial situation and family needs will change over the years. Marriages, births, career advancements, and new investments all impact your estate planning needs. By starting early, you can make gradual adjustments rather than facing an overwhelming restructuring later in life.1

3. Ensuring Asset Protection Strategies Are in Place

Many asset protection strategies require time to be effective. For instance, certain types of trusts must be in place for a number of years before they fully shield assets from legal claims. Delaying planning could leave your wealth unnecessarily exposed.

4. Creating a Legacy Beyond Wealth

Estate planning is not just about finances—it’s about legacy. Whether you want to support a charitable cause, endow a scholarship, or establish a foundation, early planning gives you the ability to shape your long-term impact.

5. Adapt to Ever Changing Legislation

Estate planning needs to be adaptable. The federal government can change the estate tax exemption at any time; this was even a topic of the last election cycle. Early planning allows you to implement necessary changes throughout your life to minimize estate taxes. At present, unless new policy is enacted, the exemption per individual will reduce by half in 2026 (see Figure 1).

Final Thoughts: Taking Action Today

The complexity of physician finances—ranging from high income and significant assets to legal risks—makes individualized estate planning an absolute necessity.

By taking proactive steps today, you can maximize tax efficiency, safeguard your assets, and ensure your wishes are carried out without unnecessary delays or legal battles. Working with a financial advisor and estate planning attorney who understands the unique needs of physicians can help you craft a plan that aligns with your goals and evolves as your career progresses.

Mr. Gardner is a financial advisor at Lifetime Financial Growth, LLC, in Columbus, Ohio, one of the largest privately held wealth management firms in the country. John has had a passion for finance since his early years in college when his tennis coach introduced him. He also has a passion for helping physicians, as his wife is a gastroenterologist at Ohio State University. He reports no relevant disclosures relevant to this article. If you have additional questions, please contact John at 740-403-4891 or john_s_gardner@glic.com.

References

1. The Law Offices of Diron Rutty, LLC. https://www.dironruttyllc.com/reasons-to-start-estate-planning-early/.

2. Physician Side Gigs. https://www.physiciansidegigs.com/estateplanning.

3. Afshar, A & MacBeth, S. https://www.schwabe.com/publication/estate-planning-for-physicians-why-its-important-and-how-to-get-started/. December 2024.

4. Skeeles, JC. https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/ep-1. July 2012.

5. Rosenfeld, J. Physician estate planning guide. Medical Economics. 2022 Nov. https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/physician-estate-planning-guide.

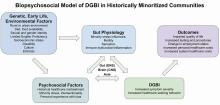

Improving Care for Patients from Historically Minoritized and Marginalized Communities with Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction

Introduction: Cases

Patient 1: A 57-year-old man with post-prandial distress variant functional dyspepsia (FD) was recommended to start nortriptyline. He previously established primary care with a physician he met at a barbershop health fair in Harlem, who referred him for specialty evaluation. Today, he presents for follow-up and reports he did not take this medication because he heard it is an antidepressant. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: A 61-year-old woman was previously diagnosed with mixed variant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-M). Her symptoms have not significantly changed. Her prior workup has been reassuring and consistent with IBS-M. Despite this, the patient pushes to repeat a colonoscopy, fearful that something is being missed or that she is not being offered care because of her undocumented status. How do you respond?

Patient 3: A 36-year-old man is followed for the management of generalized anxiety disorder and functional heartburn. He was started on low-dose amitriptyline with some benefit, but follow-up has been sporadic. On further discussion, he reports financial stressors, time barriers, and difficulty scheduling a meeting with his union representative for work accommodations as he lives in a more rural community. How do you reply?

Patient 4: A 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who uses a wheelchair has functional constipation that is well controlled on his current regimen. He has never undergone colon cancer screening. He occasionally notices blood in his stool, so a colonoscopy was recommended to confirm that his hematochezia reflects functional constipation complicated by hemorrhoids. He is concerned about the bowel preparation required for a colonoscopy given his limited mobility, as his insurance does not cover assistance at home. He does not have family members to help him. How can you assist him?

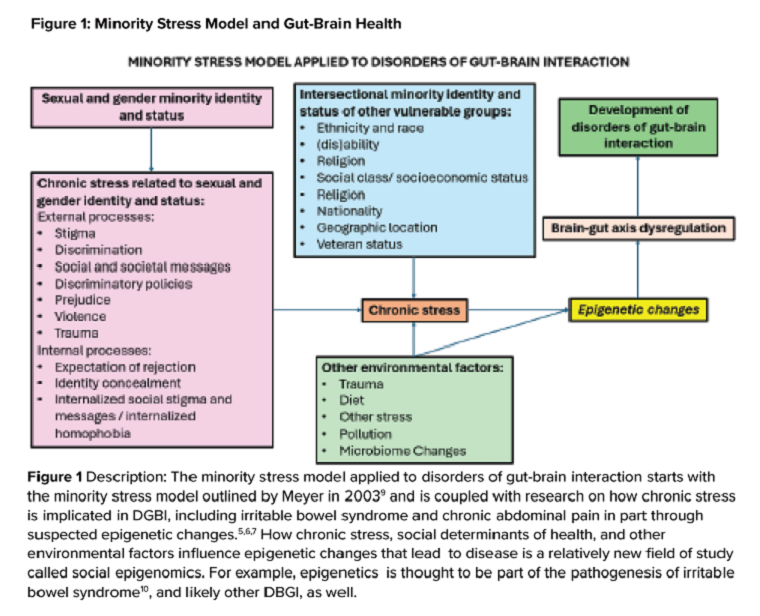

Social determinants of health, health disparities, and DGBIs

Social determinants of health affect all aspects of patient care, with an increasing body of published work looking at potential disparities in organ-based and structural diseases.1,2,3,4 However, little has been done to explore their influence on disorders of gut-brain interaction or DGBIs.

. As DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory or endoscopic test, the patient history is of the utmost importance and physician-patient rapport is paramount in their treatment. Such rapport may be more difficult to establish in patients coming from historically marginalized and minoritized communities who may be distrustful of healthcare as an institution of (discriminatory) power.

Potential DGBI management pitfalls in historically marginalized or minoritized communities

For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, disparities in healthcare take on many forms. People from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive a gastroenterology consultation and those with IBS are more likely to undergo procedures as compared to White patients with IBS.6 Implicit bias may lead to fewer specialist referrals, and specialty care may be limited or unavailable in some areas. Patients may prefer seeing providers in their own community, with whom they share racial or ethnic identities, which could lead to fewer referrals to specialists outside of the community.

Historical discrimination contributes to a lack of trust in healthcare professionals, which may lead patients to favor more objective diagnostics such as endoscopy or view being counseled against invasive procedures as having necessary care denied. Due to a broader cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, patients may be more hesitant to utilize neuromodulators, which have historically been used for psychiatric diagnoses, as it may lead them to conflate their GI illness with mental illness.7,8

Since DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single test or managed with a single treatment modality, providing excellent care for patients with DGBIs requires clear communication. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), access to high-quality language assistance is the foundation of comprehensive care. Interpreter use (or lack thereof) may limit the ability to obtain a complete and accurate clinical history, which can lead to fewer referrals to specialists and increased reliance on endoscopic evaluations that may not be clinically indicated.

These language barriers affect patients on many levels – in their ability to understand instructions for medication administration, preparation for procedures, and return precautions – which may ultimately lead to poorer responses to therapy or delays in care. LEP alone is broadly associated with fewer referrals for outpatient follow-up, adverse health outcomes and complications, and longer hospital stays.9 These disparities can be mitigated by investing in high-quality interpreter services, providing instructions and forms in multiple languages, and engaging the patient’s family and social supports according to their preferences.

People experiencing poverty (urban and rural) face challenges across multiple domains including access to healthcare, health insurance, stable housing and employment, and more. Many patients seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may face greater difficulties coordinating care with external gastroenterologists.10

Insurance barriers limit access to essential medications, tests, and procedures, and create delays in establishing care with specialists. Significant psychological stress and higher rates of comorbid anxiety and depression contribute to increased IBS severity.11 Financial limitations may limit dietary choices, which can further exacerbate DGBI symptoms. Long work hours with limited flexibility may prohibit them from presenting for regular follow-ups and establishing advanced DGBI care such as with a dietitian or psychologist.

Patients with disabilities face many of the health inequities previously discussed, as well as additional challenges with physical accessibility, transportation, exclusion from education and employment, discrimination, and stigma. Higher prevalence of comorbid mental illness and higher rates of intimate partner violence and interpersonal violence all contribute to DGBI severity and challenges with access to care.12,13 Patients with disabilities may struggle to arrive at appointments, maneuver through the building or exam room, and ultimately follow recommended care plans.

How to approach DGBIs in historically marginalized and minoritized communities

Returning to the patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them?

Patient 1: We can discuss with the patient how nortriptyline and other typical antidepressants can and often are used for indications other than depression. These medications modify centrally-mediated pain signaling and many patients with functional dyspepsia experience a significant benefit. It is critical to build on the rapport that was established at the community health outreach event and to explore the patient’s concerns thoroughly.

Patient 2: We would begin by inquiring about her underlying fears associated with her symptoms and seek to understand her goals for repeat intervention. We can review the risks of endoscopy and shift the focus to improving her symptoms. If we can improve her bowel habits or her pain, her desire for further interventions may lessen.

Patient 3: It will be important to work within the realistic time and monetary constraints in this patient’s life. We can validate him and the challenges he is facing, provide positive reinforcement for the progress he has made so far, and avoid disparaging him for the aspects of the treatment plan he has been unable to follow through with. As he reported a benefit from amitriptyline, we can consider increasing his dose as a feasible next step.

Patient 4: We can encourage the patient to discuss with his primary care physician how they may be able to coordinate an inpatient admission for colonoscopy preparation. Given his co-morbidities, this avenue will provide him dedicated support to help him adequately prep to ensure a higher quality examination and limit the need for repeat procedures.

DGBI care in historically marginalized and minoritized communities: A call to action

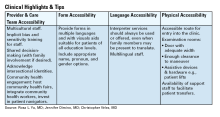

Understanding cultural differences and existing disparities in care is essential to improving care for patients from historically minoritized communities with DGBIs. Motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, with acknowledgment of social and cultural differences, allow us to work together with patients and their support systems to set and achieve feasible goals.14

To address known health disparities, offices can take steps to ensure the accessibility of language, forms, physical space, providers, and care teams. Providing culturally sensitive care and lowering barriers to care are the first steps to effecting meaningful change for patients with DGBIs from historically minoritized communities.

Dr. Yu is based at Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Boston Medical Center and Boston University, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Dimino and Dr. Vélez are based at the Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Yu, Dr. Dimino, and Dr. Vélez do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

Additional Online Resources

Form Accessibility

- Intake Form Guidance for Providers

- Making Your Clinic Welcoming to LGBTQ Patients

- Transgender data collection in the electronic health record: Current concepts and issues

Language Accessibility

Physical Accessibility

- Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities

- Making your medical office accessible

References

1. Zavala VA, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6.

2. Kardashian A, et al. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1002/hep.32743.

3. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, Gender, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1002/lt.25996.

4. Anyane-Yeboa A, et al. The Impact of the Social Determinants of Health on Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.011.

5. Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032.

6. Silvernale C, et al. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039.

7. Hearn M, et al. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: a taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30348-6.

8. Yan XJ, et al. The impact of stigma on medication adherence in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13956.

9. Twersky SE, et al. The Impact of Limited English Proficiency on Healthcare Access and Outcomes in the U.S.: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jan. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12030364.

10. Bayly JE, et al. Limited English proficiency and reported receipt of colorectal cancer screening among adults 45-75 in 2019 and 2021. Prev Med Rep. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102638.

11. Cheng K, et al. Epidemiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Large Academic Safety-Net Hospital. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.3390/jcm13051314.

12. Breiding MJ, Armour BS. The association between disability and intimate partner violence in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.017.

13. Mitra M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence against men with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.030.

14. Bahafzallah L, et al. Motivational Interviewing in Ethnic Populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00940-3.

Introduction: Cases

Patient 1: A 57-year-old man with post-prandial distress variant functional dyspepsia (FD) was recommended to start nortriptyline. He previously established primary care with a physician he met at a barbershop health fair in Harlem, who referred him for specialty evaluation. Today, he presents for follow-up and reports he did not take this medication because he heard it is an antidepressant. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: A 61-year-old woman was previously diagnosed with mixed variant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-M). Her symptoms have not significantly changed. Her prior workup has been reassuring and consistent with IBS-M. Despite this, the patient pushes to repeat a colonoscopy, fearful that something is being missed or that she is not being offered care because of her undocumented status. How do you respond?

Patient 3: A 36-year-old man is followed for the management of generalized anxiety disorder and functional heartburn. He was started on low-dose amitriptyline with some benefit, but follow-up has been sporadic. On further discussion, he reports financial stressors, time barriers, and difficulty scheduling a meeting with his union representative for work accommodations as he lives in a more rural community. How do you reply?

Patient 4: A 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who uses a wheelchair has functional constipation that is well controlled on his current regimen. He has never undergone colon cancer screening. He occasionally notices blood in his stool, so a colonoscopy was recommended to confirm that his hematochezia reflects functional constipation complicated by hemorrhoids. He is concerned about the bowel preparation required for a colonoscopy given his limited mobility, as his insurance does not cover assistance at home. He does not have family members to help him. How can you assist him?

Social determinants of health, health disparities, and DGBIs

Social determinants of health affect all aspects of patient care, with an increasing body of published work looking at potential disparities in organ-based and structural diseases.1,2,3,4 However, little has been done to explore their influence on disorders of gut-brain interaction or DGBIs.

. As DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory or endoscopic test, the patient history is of the utmost importance and physician-patient rapport is paramount in their treatment. Such rapport may be more difficult to establish in patients coming from historically marginalized and minoritized communities who may be distrustful of healthcare as an institution of (discriminatory) power.

Potential DGBI management pitfalls in historically marginalized or minoritized communities

For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, disparities in healthcare take on many forms. People from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive a gastroenterology consultation and those with IBS are more likely to undergo procedures as compared to White patients with IBS.6 Implicit bias may lead to fewer specialist referrals, and specialty care may be limited or unavailable in some areas. Patients may prefer seeing providers in their own community, with whom they share racial or ethnic identities, which could lead to fewer referrals to specialists outside of the community.

Historical discrimination contributes to a lack of trust in healthcare professionals, which may lead patients to favor more objective diagnostics such as endoscopy or view being counseled against invasive procedures as having necessary care denied. Due to a broader cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, patients may be more hesitant to utilize neuromodulators, which have historically been used for psychiatric diagnoses, as it may lead them to conflate their GI illness with mental illness.7,8

Since DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single test or managed with a single treatment modality, providing excellent care for patients with DGBIs requires clear communication. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), access to high-quality language assistance is the foundation of comprehensive care. Interpreter use (or lack thereof) may limit the ability to obtain a complete and accurate clinical history, which can lead to fewer referrals to specialists and increased reliance on endoscopic evaluations that may not be clinically indicated.

These language barriers affect patients on many levels – in their ability to understand instructions for medication administration, preparation for procedures, and return precautions – which may ultimately lead to poorer responses to therapy or delays in care. LEP alone is broadly associated with fewer referrals for outpatient follow-up, adverse health outcomes and complications, and longer hospital stays.9 These disparities can be mitigated by investing in high-quality interpreter services, providing instructions and forms in multiple languages, and engaging the patient’s family and social supports according to their preferences.

People experiencing poverty (urban and rural) face challenges across multiple domains including access to healthcare, health insurance, stable housing and employment, and more. Many patients seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may face greater difficulties coordinating care with external gastroenterologists.10

Insurance barriers limit access to essential medications, tests, and procedures, and create delays in establishing care with specialists. Significant psychological stress and higher rates of comorbid anxiety and depression contribute to increased IBS severity.11 Financial limitations may limit dietary choices, which can further exacerbate DGBI symptoms. Long work hours with limited flexibility may prohibit them from presenting for regular follow-ups and establishing advanced DGBI care such as with a dietitian or psychologist.

Patients with disabilities face many of the health inequities previously discussed, as well as additional challenges with physical accessibility, transportation, exclusion from education and employment, discrimination, and stigma. Higher prevalence of comorbid mental illness and higher rates of intimate partner violence and interpersonal violence all contribute to DGBI severity and challenges with access to care.12,13 Patients with disabilities may struggle to arrive at appointments, maneuver through the building or exam room, and ultimately follow recommended care plans.

How to approach DGBIs in historically marginalized and minoritized communities

Returning to the patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them?

Patient 1: We can discuss with the patient how nortriptyline and other typical antidepressants can and often are used for indications other than depression. These medications modify centrally-mediated pain signaling and many patients with functional dyspepsia experience a significant benefit. It is critical to build on the rapport that was established at the community health outreach event and to explore the patient’s concerns thoroughly.

Patient 2: We would begin by inquiring about her underlying fears associated with her symptoms and seek to understand her goals for repeat intervention. We can review the risks of endoscopy and shift the focus to improving her symptoms. If we can improve her bowel habits or her pain, her desire for further interventions may lessen.

Patient 3: It will be important to work within the realistic time and monetary constraints in this patient’s life. We can validate him and the challenges he is facing, provide positive reinforcement for the progress he has made so far, and avoid disparaging him for the aspects of the treatment plan he has been unable to follow through with. As he reported a benefit from amitriptyline, we can consider increasing his dose as a feasible next step.

Patient 4: We can encourage the patient to discuss with his primary care physician how they may be able to coordinate an inpatient admission for colonoscopy preparation. Given his co-morbidities, this avenue will provide him dedicated support to help him adequately prep to ensure a higher quality examination and limit the need for repeat procedures.

DGBI care in historically marginalized and minoritized communities: A call to action

Understanding cultural differences and existing disparities in care is essential to improving care for patients from historically minoritized communities with DGBIs. Motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, with acknowledgment of social and cultural differences, allow us to work together with patients and their support systems to set and achieve feasible goals.14

To address known health disparities, offices can take steps to ensure the accessibility of language, forms, physical space, providers, and care teams. Providing culturally sensitive care and lowering barriers to care are the first steps to effecting meaningful change for patients with DGBIs from historically minoritized communities.

Dr. Yu is based at Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Boston Medical Center and Boston University, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Dimino and Dr. Vélez are based at the Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Yu, Dr. Dimino, and Dr. Vélez do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

Additional Online Resources

Form Accessibility

- Intake Form Guidance for Providers

- Making Your Clinic Welcoming to LGBTQ Patients

- Transgender data collection in the electronic health record: Current concepts and issues

Language Accessibility

Physical Accessibility

- Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities

- Making your medical office accessible

References

1. Zavala VA, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6.

2. Kardashian A, et al. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1002/hep.32743.

3. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, Gender, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1002/lt.25996.

4. Anyane-Yeboa A, et al. The Impact of the Social Determinants of Health on Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.011.

5. Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032.

6. Silvernale C, et al. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039.

7. Hearn M, et al. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: a taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30348-6.

8. Yan XJ, et al. The impact of stigma on medication adherence in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13956.

9. Twersky SE, et al. The Impact of Limited English Proficiency on Healthcare Access and Outcomes in the U.S.: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jan. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12030364.

10. Bayly JE, et al. Limited English proficiency and reported receipt of colorectal cancer screening among adults 45-75 in 2019 and 2021. Prev Med Rep. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102638.

11. Cheng K, et al. Epidemiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Large Academic Safety-Net Hospital. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.3390/jcm13051314.

12. Breiding MJ, Armour BS. The association between disability and intimate partner violence in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.017.

13. Mitra M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence against men with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.030.

14. Bahafzallah L, et al. Motivational Interviewing in Ethnic Populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00940-3.

Introduction: Cases

Patient 1: A 57-year-old man with post-prandial distress variant functional dyspepsia (FD) was recommended to start nortriptyline. He previously established primary care with a physician he met at a barbershop health fair in Harlem, who referred him for specialty evaluation. Today, he presents for follow-up and reports he did not take this medication because he heard it is an antidepressant. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: A 61-year-old woman was previously diagnosed with mixed variant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-M). Her symptoms have not significantly changed. Her prior workup has been reassuring and consistent with IBS-M. Despite this, the patient pushes to repeat a colonoscopy, fearful that something is being missed or that she is not being offered care because of her undocumented status. How do you respond?

Patient 3: A 36-year-old man is followed for the management of generalized anxiety disorder and functional heartburn. He was started on low-dose amitriptyline with some benefit, but follow-up has been sporadic. On further discussion, he reports financial stressors, time barriers, and difficulty scheduling a meeting with his union representative for work accommodations as he lives in a more rural community. How do you reply?

Patient 4: A 74-year-old man with Parkinson’s disease who uses a wheelchair has functional constipation that is well controlled on his current regimen. He has never undergone colon cancer screening. He occasionally notices blood in his stool, so a colonoscopy was recommended to confirm that his hematochezia reflects functional constipation complicated by hemorrhoids. He is concerned about the bowel preparation required for a colonoscopy given his limited mobility, as his insurance does not cover assistance at home. He does not have family members to help him. How can you assist him?

Social determinants of health, health disparities, and DGBIs

Social determinants of health affect all aspects of patient care, with an increasing body of published work looking at potential disparities in organ-based and structural diseases.1,2,3,4 However, little has been done to explore their influence on disorders of gut-brain interaction or DGBIs.

. As DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single laboratory or endoscopic test, the patient history is of the utmost importance and physician-patient rapport is paramount in their treatment. Such rapport may be more difficult to establish in patients coming from historically marginalized and minoritized communities who may be distrustful of healthcare as an institution of (discriminatory) power.

Potential DGBI management pitfalls in historically marginalized or minoritized communities

For racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, disparities in healthcare take on many forms. People from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to receive a gastroenterology consultation and those with IBS are more likely to undergo procedures as compared to White patients with IBS.6 Implicit bias may lead to fewer specialist referrals, and specialty care may be limited or unavailable in some areas. Patients may prefer seeing providers in their own community, with whom they share racial or ethnic identities, which could lead to fewer referrals to specialists outside of the community.

Historical discrimination contributes to a lack of trust in healthcare professionals, which may lead patients to favor more objective diagnostics such as endoscopy or view being counseled against invasive procedures as having necessary care denied. Due to a broader cultural stigma surrounding mental illness, patients may be more hesitant to utilize neuromodulators, which have historically been used for psychiatric diagnoses, as it may lead them to conflate their GI illness with mental illness.7,8

Since DGBIs cannot be diagnosed with a single test or managed with a single treatment modality, providing excellent care for patients with DGBIs requires clear communication. For patients with limited English proficiency (LEP), access to high-quality language assistance is the foundation of comprehensive care. Interpreter use (or lack thereof) may limit the ability to obtain a complete and accurate clinical history, which can lead to fewer referrals to specialists and increased reliance on endoscopic evaluations that may not be clinically indicated.

These language barriers affect patients on many levels – in their ability to understand instructions for medication administration, preparation for procedures, and return precautions – which may ultimately lead to poorer responses to therapy or delays in care. LEP alone is broadly associated with fewer referrals for outpatient follow-up, adverse health outcomes and complications, and longer hospital stays.9 These disparities can be mitigated by investing in high-quality interpreter services, providing instructions and forms in multiple languages, and engaging the patient’s family and social supports according to their preferences.

People experiencing poverty (urban and rural) face challenges across multiple domains including access to healthcare, health insurance, stable housing and employment, and more. Many patients seek care at federally qualified health centers, which may face greater difficulties coordinating care with external gastroenterologists.10

Insurance barriers limit access to essential medications, tests, and procedures, and create delays in establishing care with specialists. Significant psychological stress and higher rates of comorbid anxiety and depression contribute to increased IBS severity.11 Financial limitations may limit dietary choices, which can further exacerbate DGBI symptoms. Long work hours with limited flexibility may prohibit them from presenting for regular follow-ups and establishing advanced DGBI care such as with a dietitian or psychologist.

Patients with disabilities face many of the health inequities previously discussed, as well as additional challenges with physical accessibility, transportation, exclusion from education and employment, discrimination, and stigma. Higher prevalence of comorbid mental illness and higher rates of intimate partner violence and interpersonal violence all contribute to DGBI severity and challenges with access to care.12,13 Patients with disabilities may struggle to arrive at appointments, maneuver through the building or exam room, and ultimately follow recommended care plans.

How to approach DGBIs in historically marginalized and minoritized communities

Returning to the patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them?

Patient 1: We can discuss with the patient how nortriptyline and other typical antidepressants can and often are used for indications other than depression. These medications modify centrally-mediated pain signaling and many patients with functional dyspepsia experience a significant benefit. It is critical to build on the rapport that was established at the community health outreach event and to explore the patient’s concerns thoroughly.

Patient 2: We would begin by inquiring about her underlying fears associated with her symptoms and seek to understand her goals for repeat intervention. We can review the risks of endoscopy and shift the focus to improving her symptoms. If we can improve her bowel habits or her pain, her desire for further interventions may lessen.

Patient 3: It will be important to work within the realistic time and monetary constraints in this patient’s life. We can validate him and the challenges he is facing, provide positive reinforcement for the progress he has made so far, and avoid disparaging him for the aspects of the treatment plan he has been unable to follow through with. As he reported a benefit from amitriptyline, we can consider increasing his dose as a feasible next step.

Patient 4: We can encourage the patient to discuss with his primary care physician how they may be able to coordinate an inpatient admission for colonoscopy preparation. Given his co-morbidities, this avenue will provide him dedicated support to help him adequately prep to ensure a higher quality examination and limit the need for repeat procedures.

DGBI care in historically marginalized and minoritized communities: A call to action

Understanding cultural differences and existing disparities in care is essential to improving care for patients from historically minoritized communities with DGBIs. Motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, with acknowledgment of social and cultural differences, allow us to work together with patients and their support systems to set and achieve feasible goals.14

To address known health disparities, offices can take steps to ensure the accessibility of language, forms, physical space, providers, and care teams. Providing culturally sensitive care and lowering barriers to care are the first steps to effecting meaningful change for patients with DGBIs from historically minoritized communities.

Dr. Yu is based at Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Boston Medical Center and Boston University, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Dimino and Dr. Vélez are based at the Division of Gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Dr. Yu, Dr. Dimino, and Dr. Vélez do not have any conflicts of interest for this article.

Additional Online Resources

Form Accessibility

- Intake Form Guidance for Providers

- Making Your Clinic Welcoming to LGBTQ Patients

- Transgender data collection in the electronic health record: Current concepts and issues

Language Accessibility

Physical Accessibility

- Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities

- Making your medical office accessible

References

1. Zavala VA, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6.

2. Kardashian A, et al. Health disparities in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2023 Apr. doi: 10.1002/hep.32743.

3. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, Gender, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021 Jun. doi: 10.1002/lt.25996.

4. Anyane-Yeboa A, et al. The Impact of the Social Determinants of Health on Disparities in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.03.011.

5. Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032.

6. Silvernale C, et al. Racial disparity in healthcare utilization among patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: results from a multicenter cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 May. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14039.

7. Hearn M, et al. Stigma and irritable bowel syndrome: a taboo subject? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30348-6.

8. Yan XJ, et al. The impact of stigma on medication adherence in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021 Feb. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13956.

9. Twersky SE, et al. The Impact of Limited English Proficiency on Healthcare Access and Outcomes in the U.S.: A Scoping Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jan. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12030364.

10. Bayly JE, et al. Limited English proficiency and reported receipt of colorectal cancer screening among adults 45-75 in 2019 and 2021. Prev Med Rep. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102638.

11. Cheng K, et al. Epidemiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in a Large Academic Safety-Net Hospital. J Clin Med. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.3390/jcm13051314.

12. Breiding MJ, Armour BS. The association between disability and intimate partner violence in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.017.

13. Mitra M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence against men with disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.030.

14. Bahafzallah L, et al. Motivational Interviewing in Ethnic Populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00940-3.

A Practical Approach to Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) can be considered a “young” disease, with initial case series reported only about 30 years ago. Since that time, it has become a commonly encountered condition in both emergency and clinic settings. The most recent prevalence study estimates that 1 in 700 people in the U.S. have EoE,1 the volume of EoE-associated ED visits tripped between 2009 and 2019 and is projected to double again by 2030,2 and “new” gastroenterologists undoubtedly have learned about and seen this condition. As a chronic disease, EoE necessitates longitudinal follow-up and optimization of care to prevent complications. With increasing diagnostic delay, EoE progresses in most, but not all, patients from an inflammatory- to fibrostenotic-predominant condition.3

Diagnosis of EoE

The most likely area that you will encounter EoE is during an emergent middle-of-the-night endoscopy for food impaction. If called in for this, EoE will be the cause in more than 50% of patients.4 However, the diagnosis can only be made if esophageal biopsies are obtained at the time of the procedure. This is a critical time to decrease diagnostic delay, as half of patients are lost to follow-up after a food impaction.5 Unfortunately, although taking biopsies during index food impaction is guideline-recommended, a quality metric, and safe to obtain after the food bolus is cleared, this is infrequently done in practice.6, 7

The next most likely area for EoE detection is in the endoscopy suite where 15-23% of patients with dysphagia and 5-7% of patients undergoing upper endoscopy for any indication will have EoE.4 Sometimes EoE will be detected “incidentally” during an open-access case (for example, in a patient with diarrhea undergoing evaluation for celiac). In these cases, it is important to perform a careful history (as noted below) as subtle EoE symptoms can frequently be identified. Finally, when patients are seen in clinic for solid food dysphagia, EoE is clearly on the differential. A few percent of patients with refractory heartburn or chest pain will have EoE causing the symptoms rather than reflux,4 and all patients under consideration for antireflux surgery should have an endoscopy to assess for EoE.

When talking to patients with known or suspected EoE, the history must go beyond general questions about dysphagia or trouble swallowing. Many patients with EoE have overtly or subconsciously modified their eating behaviors over many years to minimize symptoms, may have adapted to chronic dysphagia, and will answer “no” when asked if they have trouble swallowing. Instead, use the acronym “IMPACT” to delve deeper into possible symptoms.8 Do they “Imbibe” fluids or liquids between each bite to help get food down? Do they “Modify” the way they eat (cut food into small bites; puree foods)? Do they “Prolong” mealtimes? Do they “Avoid” certain foods that stick? Do they “Chew’ until their food is a mush to get it down? And do they “Turn away” tablets or pills? Pill dysphagia is often a subtle symptom, and sometimes the only symptom elicited.

Additionally, it may be important to ask a partner or family member (if present) about their observations. They may provide insight (e.g. “yes – he chokes with every bite but never says it bothers him”) that the patient might not otherwise provide. The suspicion for EoE should also be increased in patients with concomitant atopic diseases and in those with a family history of dysphagia or who have family members needing esophageal dilation. It is important to remember that EoE can be seen across all ages, sexes, and races/ethnicities.

Diagnosis of EoE is based on the AGREE consensus,9 which is also echoed in the recently updated American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines.10 Diagnosis requires three steps. First, symptoms of esophageal dysfunction must be present. This will most typically be dysphagia in adolescents and adults, but symptoms are non-specific in children (e.g. poor growth and feeding, abdominal pain, vomiting, regurgitation, heartburn).

Second, at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) are required on esophageal biopsy, which implies that an endoscopy be performed. A high-quality endoscopic exam in EoE is of the utmost importance. The approach has been described elsewhere,11 but enough time on insertion should be taken to fully insufflate and examine the esophagus, including the areas of the gastroesophageal junction and upper esophageal sphincter where strictures can be missed, to gently wash debris, and to assess the endoscopic findings of EoE. Endoscopic findings should be reported using the validated EoE Endoscopy Reference Score (EREFS),12 which grades five key features. EREFS is reproducible, is responsive to treatment, and is guideline-recommended (see Figure 1).6, 10 The features are edema (present=1), rings (mild=1; moderate=2; severe=3), exudates (mild=1; severe=2), furrows (mild=1; severe=2), and stricture (present=1; also estimate diameter in mm) and are incorporated into many endoscopic reporting programs. Additionally, diffuse luminal narrowing and mucosal fragility (“crepe-paper” mucosa) should be assessed.

After this, biopsies should be obtained with at least 6 biopsy fragments from different locations in the esophagus. Any visible endoscopic abnormalities should be targeted (the highest yield is in exudates and furrows). The rationale is that EoE is patchy and at least 6 biopsies will maximize diagnostic yield.10 Ideally the initial endoscopy for EoE should be done off of treatments (like PPI or diet restriction) as these could mask the diagnosis. If a patient with suspected EoE has an endoscopy while on PPI, and the endoscopy is normal, a diagnosis of EoE cannot be made. In this case, consideration should be given as to stopping the PPI, allowing a wash out period (at least 1-2 months), and then repeating the endoscopy to confirm the diagnosis. This is important as EoE is a chronic condition necessitating life-long treatment and monitoring, so a definitive diagnosis is critical.

The third and final step in diagnosis is assessing for other conditions that could cause esophageal eosinophilia.9 The most common differential diagnosis is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In some cases, EoE and GERD overlap or can have a complex relationship.13 Unfortunately the location of the eosinophilia (i.e. distal only) and the level of the eosinophil counts are not useful in making this distinction, so all clinical features (symptoms, presence of erosive esophagitis, or a hiatal hernia endoscopically), and ancillary reflex testing when indicated may be required prior to a formal EoE diagnosis. After the diagnosis is established, there should be direct communication with the patient to review the diagnosis and select treatments. While it is possible to convey results electronically in a messaging portal or with a letter, a more formal interaction, such as a clinic visit, is recommended because this is a new diagnosis of a chronic condition. Similarly, a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease would never be made in a pathology follow-up letter alone.

Treatment of EoE

When it comes to treatment, the new guidelines emphasize several points.10 First, there is the concept that anti-inflammatory treatment should be paired with assessment of fibrostenosis and esophageal dilation; to do either in isolation is incomplete treatment. It is safe to perform dilation both prior to anti-inflammatory treatment (for example, with a critical stricture in a patient with dysphagia) and after anti-inflammatory treatment has been prescribed (for example, during an endoscopy to assess treatment response).

Second, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), swallowed topical corticosteroids (tCS), or dietary elimination are all acceptable first-line treatment options for EoE. A shared decision-making framework should be used for this discussion. If dietary elimination is selected,14 based on new clinical trial data, guidelines recommend using empiric elimination and starting with a less restrictive diet (either a one-food elimination diet with dairy alone or a two-food elimination with dairy and wheat elimination). If PPIs are selected, the dose should be double the standard reflux dose. Data are mixed as to whether to use twice daily dosing (i.e., omeprazole 20 mg twice daily) or once a day dosing (i.e., omeprazole 40 mg daily), but total dose and adherence may be more important than frequency.10

For tCS use, either budesonide or fluticasone can be selected, but budesonide oral suspension is the only FDA-approved tCS for EoE.15 Initial treatment length is usually 6-8 weeks for diet elimination and, 12 weeks for PPI and tCS. In general, it is best to pick a single treatment to start, and reserve combining therapies for patients who do not have a complete response to a single modality as there are few data to support combination therapy.

After initial treatment, it is critical to assess for treatment response.16 Goals of EoE treatment include improvement in symptoms, but also improvement in endoscopic and histologic features to prevent complications. Symptoms in EoE do not always correlate with underlying biologic disease activity: patients can minimize symptoms with careful eating; they may perceive no difference in symptoms despite histologic improvement if a stricture persists; and they may have minimal symptoms after esophageal dilation despite ongoing inflammation. Because of this, performing a follow-up endoscopy after initial treatment is guideline-recommended.10, 17 This allows assessing for endoscopic improvement, re-assessing for fibrostenosis and performing dilation if indicated, and obtaining esophageal biopsies. If there is non-response, options include switching between other first line treatments or considering “stepping-up” to dupilumab which is also an FDA-approved option for EoE that is recommended in the guidelines.10, 18 In some cases where patients have multiple severe atopic conditions such as asthma or eczema that would warrant dupilumab use, or if patients are intolerant to PPIs or tCS, dupilumab could be considered as an earlier treatment for EoE.

Long-Term Maintenance

If a patient has a good response (for example, improved symptoms, improved endoscopic features, and <15 eos/hpf on biopsy), treatment can be maintained long-term. In almost all cases, if treatment is stopped, EoE disease activity recurs.19 Patients could be seen back in clinic in 6-12 months, and then a discussion can be conducted about a follow-up endoscopy, with timing to be determined based on their individual disease features and severity.17

Patients with more severe strictures, however, may have to be seen in endoscopy for serial dilations. Continued follow-up is essential for optimal care. Just as patients can progress in their disease course with diagnostic delay, there are data that show they can also progress after diagnosis when there are gaps in care without regular follow-up.20 Unlike other chronic esophageal disorders such as GERD and Barrett’s esophagus and other chronic GI inflammatory conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, however, EoE is not associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer.21, 22

Given its increasing frequency, EoE will be commonly encountered by gastroenterologists both new and established. Having a systematic approach for diagnosis, understanding how to elicit subtle symptoms, implementing a shared decision-making framework for treatment with a structured algorithm for assessing response, performing follow-up, maintaining treatment, and monitoring patients long-term will allow the large majority of EoE patients to be successfully managed.

Dr. Dellon is based at the Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. He disclosed research funding, consultant fees, and educational grants from multiple companies.

References

1. Thel HL, et al. Prevalence and Costs of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.09.031.

2. Lam AY, et al. Epidemiologic Burden and Projections for Eosinophilic Esophagitis-Associated Emergency Department Visits in the United States: 2009-2030. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.028.

3. Schoepfer AM, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013 Dec. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015.

4. Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and Natural History of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.067.

5. Chang JW, et al. Loss to follow-up after food impaction among patients with and without eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2019 Dec. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz056.

6. Aceves SS, et al. Endoscopic approach to eosinophilic esophagitis: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Consensus Conference. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.05.013.

7. Leiman DA, et al. Quality Indicators for the Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002138.

8. Hirano I, Furuta GT. Approaches and Challenges to Management of Pediatric and Adult Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.052.

9. Dellon ES, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009.

10. Dellon ES, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000003194.

11. Dellon ES. Optimizing the Endoscopic Examination in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.011.

12. Hirano I, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2012 May. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817.

13. Spechler SJ, et al. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jun. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01179.x.

14. Chang JW, et al. Development of a Practical Guide to Implement and Monitor Diet Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.006.

15. Hirano I, et al. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.022.

16. Dellon ES, Gupta SK. A conceptual approach to understanding treatment response in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.030.

17. von Arnim U, et al. Monitoring Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Routine Clinical Practice - International Expert Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.018.

18. Dellon ES, et al. Dupilumab in Adults and Adolescents with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa220598.

19. Dellon ES, et al. Rapid Recurrence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Activity After Successful Treatment in the Observation Phase of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.050.