User login

Prevalence of Glaucoma in Patients With Vitiligo

Vitiligo is an acquired idiopathic disease of unknown etiology. Characterized by depigmented maculae and melanocytic destruction, it usually presents in childhood or young adulthood. The incidence of vitiligo ranges from 0.5% to 2% globally and there is no racial or gender predilection.1

Patients with vitiligo may exhibit pigmentary abnormalities of the iris and retina.2 Noninflammatory depigmented lesions of the ocular fundus observed in vitiligo indicate a local loss of melanocytes.1 The fact that melanocytes are present not only in the skin and roots of the hair but also in the uvea and stria vascularis of the inner ear may explain the ophthalmologic disorders that accompany vitiligo.3 The term glaucoma refers to a large number of diseases that share a common feature: a distinctive and progressive optic neuropathy that may derive from various risks and is associated with a gradual loss of the visual field. If the disorder is not diagnosed and treated properly it could cause blindness.

Glaucoma is classified on the basis of the underlying abnormality that causes intraocular pressure (IOP) to rise. Glaucoma is first divided into open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma; glaucoma associated with developmental anomalies is then subdivided according to specific alterations.4

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms vitiligo and glaucoma revealed only 1 study examining the incidence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo.5 In the study reported here, we determined the presence of and possible risk factors for glaucoma in patients with vitiligo who had presented to the dermatology polyclinic.

Methods

We registered 49 patients diagnosed with vitiligo by clinical and Wood light examination and 20 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Patients who were using topical corticosteroid treatments for vitiligo lesions located on the face were excluded from the study due to the glaucoma-inducing effects of corticosteroids. Similarly, patients who received drugs with sympathetic and parasympathetic action that can cause glaucoma were excluded.

The patients received a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination that included visual acuity testing, refraction, IOP measurement, gonioscopy, and fundus examination. All patients and controls underwent visual field tests and optic nerve head analyses using a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Glaucoma was diagnosed based on fundus examination, IOP measurement, field of vision evaluation, and optic nerve head analysis.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research protocol was approved by the university hospital ethics committee.

Results

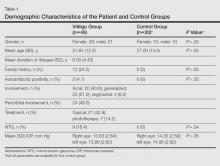

The study registered a total of 49 patients with vitiligo (28 female; 21 male) and 20 healthy controls (10 female; 10 male) with a variety of demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Mean (SD) IOP values were 13.83 (2.84) mm Hg for the right eye and 13.89 (2.60) mm Hg for the left eye in the vitiligo group. Values were 14.35 (2.56) mm Hg and 14.95 (2.92) mm Hg, respectively, in the control group. The IOP differences between the 2 groups were not statistically significant (P>.05).

Nine patients (18.4%) in the vitiligo group were found to have signs of normal-tension glaucoma (NTG). Optic nerve damage and vision loss occurs in the presence of normal IOP in NTG. There were no signs of NTG in the control group. Normal-tension glaucoma was diagnosed in the vitiligo group based on glaucomatous optic disc appearance, visual field defects, and structural analysis of the entire optic nerve head in confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. The NTG difference between the vitiligo and control groups was statistically significant (P=.04).

In the vitiligo group, of the 9 patients who had NTG, 6 had periorbital vitiligo lesions; the remaining 3 had none. Although patients who had periorbital lesions had a higher rate of glaucoma relative to the patients without periorbital lesions, the difference was not statistically significant (P>.05).

No statistically significant differences (P>.05) were found between patients with vitiligo with and without glaucoma in terms of age, sex, disease duration, family history of vitiligo, presence or absence of periorbital involvement, manner of involvement, percentage of the involved body areas, and IOP (Table 1).

Comment

Glaucoma is characterized by increased IOP, visual field loss, and changes in the optic nerve head. Although elevated IOP is common in ocular hypertension as well as in glaucoma, there is no glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertension. In NTG, on the other hand, glaucomatous visual field loss and optic nerve head changes occur without an increase in IOP.6 Normal-tension glaucoma is a particular type of open-angle glaucoma. It is believed that NTG and high-tension glaucoma induce optic nerve head damage through different means.7 Alternative theories have been put forth to account for the glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve head that occurs in NTG, despite normal or close to normal IOP. These theories include vascular disorders (eg, ischemia, which interrupts the orthograde or retrograde axonal transport), excessive accumulation of free radicals, triggering of apoptosis, and low resistance of lamina cribrosa.8

Although there are various studies exploring ocular symptoms in patients with vitiligo,9-15 only 1 study has examined the incidence of glaucoma in this group of patients.5 Biswas et al11 examined ocular signs in 100 patients with vitiligo and found that 23% of patients had hypopigmented foci in the iris, 18% had pigmentation in the anterior chamber, 11% had chorioretinal degeneration, 9% had hypopigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium, 5% had uveitis, and 34% were evaluated as normal. In this study, the authors concluded that there was a strong relationship between vitiligo and eye diseases.11 When Gopal et al9 compared the eye examinations of 150 vitiligo patients and 100 healthy controls, they found uveitis, iris, and retinal pigmentary abnormalities in 16% of the vitiligo patients (P<.001).

Rogosić et al5 examined the incidence of glaucoma in 42 patients with vitiligo and found primary open-angle glaucoma in 24 (57%) patients. The patients had a mean age of 56 years, mean disease duration of 13 years, and mean IOP of 18 mm Hg for the right eye and 17.5 mm Hg for the left eye. The incidence of glaucoma was significantly higher in patients with vitiligo (P<.001) and increased with disease duration.5

Similar studies, however, have failed to show a relationship between vitiligo and glaucoma. In a study that evaluated the retinal pigment epithelium and the optic nerve in patients with vitiligo, Perossini et al10 found that the fundus examination of the patients was perfectly normal.

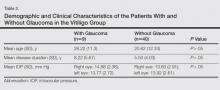

In our study, we detected NTG in 18.4% of patients with vitiligo. We did not find a significant statistical difference between patients with and without glaucoma (Table 2). Rogosić et al5 found a significant relationship between age and glaucoma incidence, but we did not find such a relationship, which we believe is because the mean age of our patients was lower than the prior study.

In vitiligo, melanocytes are destroyed through an unknown mechanism. Although the cellular and molecular mechanisms causing melanocytic destruction have not yet been determined, various hypotheses have been put forward to explain the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo. Among these, the most commonly held hypotheses are the neural, self-destruction, and autoimmune hypotheses.16

Based on the observation that stress and serious trauma could precipitate or trigger the onset of vitiligo,16 the neural hypothesis holds that neurochemical mediators released from the edges of the nerve endings exert toxic effects on melanocytes. The fact that both melanocytes and choroidal pigment cells originate from the mesenchyme and dermatomal spreading of segmental vitiligo are arguments propounded in favor of this hypothesis.17

The self-destruction hypothesis suggests that the intrinsic protective mechanisms that normally enable melanocytes to eliminate toxic intermediate products or metabolites on the melanogenesis path have been impaired in patients with vitiligo.18,19 There is evidence of increased oxidative stress over the whole epidermis of patients with vitiligo.20 Thus, free radicals affect melanin and cause membrane damage via lipid peroxidation reactions.21

The autoimmune hypothesis proposes a clinical relationship between vitiligo and several diseases believed to be autoimmune. Because the macrophage infiltration observed in vitiligo lesions is more pronounced on the perilesional skin, this hypothesis holds that macrophages may play a role in melanocyte removal.21 The Koebner phenomenon observed in vitiligo lends support to the critical role of trauma in the etiopathogenesis of the disease.

Although we could not explain the co-presence of vitiligo and glaucoma, we believe that it may result from the fact that both diseases are observed in tissues that have the same embryologic origin and etiology, perhaps vascular or neural disorders, excessive accumulation of free radicals, or the triggering of apoptosis. Dermatologists should be alert to the presence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo because glaucoma is an eye disease that progresses slowly and may lead to vision loss.

1. Ortonne JP. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JB, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:947-973.

2. Ortonne JP, Bahadoran P, Fitzpatrick TB, et al. Hypomelanoses and hypermelanoses. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:836-881.

3. van den Wijngaard R, Wijngaard R, Wankowiczs-Kalinsa A, et al. Autoimmune melanocyte destruction in vitiligo. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1061-1067.

4. Shields MB, Ritch R, Krupin T. Classification of the glaucomas. In: Ritch R, Shields MB, Krupin T, eds. The Glaucomas. St Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co; 1996:717-725.

5. Rogosić V, Bojić L, Puizina-Ivić N, et al. Vitiligo and glaucoma–an association or a coincidence? a pilot study. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:21-26.

6. Anderson DR. Normal-tension glaucoma (low-tension glaucoma). Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(suppl 59):S97-S101.

7. Iwata K. Primary open angle glaucoma and low tension glaucoma–pathogenesis and mechanism of optic nerve damage [in Japanese]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;96:1501-1531.

8. Hitchings RA, Anderton SA. A comparative study of visual field defects seen in patients with low-tension glaucoma and chronic simple glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1983;67:818-821.

9. Gopal KV, Rama Rao GR, Kumar YH, et al. Vitiligo: a part of a systemic autoimmune process. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:162-165.

10. Perossini M, Turio E, Perossini T, et al. Vitiligo: ocular and electrophysiological findings. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:141-149.

11. Biswas G, Barbhuiya JN, Biswas MC, et al. Clinical pattern of ocular manifestations in vitiligo. J Indian Med Assoc. 2003;101:478-480.

12. Park S, Albert DM, Bolognia JL. Ocular manifestations of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:609-622.

13. Albert DM, Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB. Ocular abnormalities occurring with vitiligo. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:1145-1160.

14. Wagoner MD, Albert DM, Lerner AB, et al. New observations on vitiligo and ocular disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:16-26.

15. Cowan CL Jr, Halder RM, Grimes PE, et al. Ocular disturbances in vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:17-24.

16. Orecchia GE. Neural pathogenesis. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:142-150.

17. Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolf HH, et al. Disorders of melanin pigmentation. In: Bartels V, ed. Dermatology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2000:1013-1042.

18. Tüzün Y, Kotoğyan A, Aydemir EH, et al. Pigmentasyon bozuklukları. In: Baransü O. Dermatoloji. 2nd ed. Istanbul: Nobel Tıp Kitabevi; 1994:557-559.

19. Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Disturbances of pigmentation. In: Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000:1065-1068.

20. Schallreuter KU. Biochemical theory of vitiligo: a role of pteridines in pigmentation. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. London, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:151-159.

21. van den Wijngaard R, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, Le Poole C, et al. Local immune response in skin of generalized vitiligo patients. destruction of melanocytes is associated with the predominent presence of CLA+T cells at the perilesional site. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1299-1309.

Vitiligo is an acquired idiopathic disease of unknown etiology. Characterized by depigmented maculae and melanocytic destruction, it usually presents in childhood or young adulthood. The incidence of vitiligo ranges from 0.5% to 2% globally and there is no racial or gender predilection.1

Patients with vitiligo may exhibit pigmentary abnormalities of the iris and retina.2 Noninflammatory depigmented lesions of the ocular fundus observed in vitiligo indicate a local loss of melanocytes.1 The fact that melanocytes are present not only in the skin and roots of the hair but also in the uvea and stria vascularis of the inner ear may explain the ophthalmologic disorders that accompany vitiligo.3 The term glaucoma refers to a large number of diseases that share a common feature: a distinctive and progressive optic neuropathy that may derive from various risks and is associated with a gradual loss of the visual field. If the disorder is not diagnosed and treated properly it could cause blindness.

Glaucoma is classified on the basis of the underlying abnormality that causes intraocular pressure (IOP) to rise. Glaucoma is first divided into open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma; glaucoma associated with developmental anomalies is then subdivided according to specific alterations.4

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms vitiligo and glaucoma revealed only 1 study examining the incidence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo.5 In the study reported here, we determined the presence of and possible risk factors for glaucoma in patients with vitiligo who had presented to the dermatology polyclinic.

Methods

We registered 49 patients diagnosed with vitiligo by clinical and Wood light examination and 20 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Patients who were using topical corticosteroid treatments for vitiligo lesions located on the face were excluded from the study due to the glaucoma-inducing effects of corticosteroids. Similarly, patients who received drugs with sympathetic and parasympathetic action that can cause glaucoma were excluded.

The patients received a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination that included visual acuity testing, refraction, IOP measurement, gonioscopy, and fundus examination. All patients and controls underwent visual field tests and optic nerve head analyses using a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Glaucoma was diagnosed based on fundus examination, IOP measurement, field of vision evaluation, and optic nerve head analysis.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research protocol was approved by the university hospital ethics committee.

Results

The study registered a total of 49 patients with vitiligo (28 female; 21 male) and 20 healthy controls (10 female; 10 male) with a variety of demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Mean (SD) IOP values were 13.83 (2.84) mm Hg for the right eye and 13.89 (2.60) mm Hg for the left eye in the vitiligo group. Values were 14.35 (2.56) mm Hg and 14.95 (2.92) mm Hg, respectively, in the control group. The IOP differences between the 2 groups were not statistically significant (P>.05).

Nine patients (18.4%) in the vitiligo group were found to have signs of normal-tension glaucoma (NTG). Optic nerve damage and vision loss occurs in the presence of normal IOP in NTG. There were no signs of NTG in the control group. Normal-tension glaucoma was diagnosed in the vitiligo group based on glaucomatous optic disc appearance, visual field defects, and structural analysis of the entire optic nerve head in confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. The NTG difference between the vitiligo and control groups was statistically significant (P=.04).

In the vitiligo group, of the 9 patients who had NTG, 6 had periorbital vitiligo lesions; the remaining 3 had none. Although patients who had periorbital lesions had a higher rate of glaucoma relative to the patients without periorbital lesions, the difference was not statistically significant (P>.05).

No statistically significant differences (P>.05) were found between patients with vitiligo with and without glaucoma in terms of age, sex, disease duration, family history of vitiligo, presence or absence of periorbital involvement, manner of involvement, percentage of the involved body areas, and IOP (Table 1).

Comment

Glaucoma is characterized by increased IOP, visual field loss, and changes in the optic nerve head. Although elevated IOP is common in ocular hypertension as well as in glaucoma, there is no glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertension. In NTG, on the other hand, glaucomatous visual field loss and optic nerve head changes occur without an increase in IOP.6 Normal-tension glaucoma is a particular type of open-angle glaucoma. It is believed that NTG and high-tension glaucoma induce optic nerve head damage through different means.7 Alternative theories have been put forth to account for the glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve head that occurs in NTG, despite normal or close to normal IOP. These theories include vascular disorders (eg, ischemia, which interrupts the orthograde or retrograde axonal transport), excessive accumulation of free radicals, triggering of apoptosis, and low resistance of lamina cribrosa.8

Although there are various studies exploring ocular symptoms in patients with vitiligo,9-15 only 1 study has examined the incidence of glaucoma in this group of patients.5 Biswas et al11 examined ocular signs in 100 patients with vitiligo and found that 23% of patients had hypopigmented foci in the iris, 18% had pigmentation in the anterior chamber, 11% had chorioretinal degeneration, 9% had hypopigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium, 5% had uveitis, and 34% were evaluated as normal. In this study, the authors concluded that there was a strong relationship between vitiligo and eye diseases.11 When Gopal et al9 compared the eye examinations of 150 vitiligo patients and 100 healthy controls, they found uveitis, iris, and retinal pigmentary abnormalities in 16% of the vitiligo patients (P<.001).

Rogosić et al5 examined the incidence of glaucoma in 42 patients with vitiligo and found primary open-angle glaucoma in 24 (57%) patients. The patients had a mean age of 56 years, mean disease duration of 13 years, and mean IOP of 18 mm Hg for the right eye and 17.5 mm Hg for the left eye. The incidence of glaucoma was significantly higher in patients with vitiligo (P<.001) and increased with disease duration.5

Similar studies, however, have failed to show a relationship between vitiligo and glaucoma. In a study that evaluated the retinal pigment epithelium and the optic nerve in patients with vitiligo, Perossini et al10 found that the fundus examination of the patients was perfectly normal.

In our study, we detected NTG in 18.4% of patients with vitiligo. We did not find a significant statistical difference between patients with and without glaucoma (Table 2). Rogosić et al5 found a significant relationship between age and glaucoma incidence, but we did not find such a relationship, which we believe is because the mean age of our patients was lower than the prior study.

In vitiligo, melanocytes are destroyed through an unknown mechanism. Although the cellular and molecular mechanisms causing melanocytic destruction have not yet been determined, various hypotheses have been put forward to explain the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo. Among these, the most commonly held hypotheses are the neural, self-destruction, and autoimmune hypotheses.16

Based on the observation that stress and serious trauma could precipitate or trigger the onset of vitiligo,16 the neural hypothesis holds that neurochemical mediators released from the edges of the nerve endings exert toxic effects on melanocytes. The fact that both melanocytes and choroidal pigment cells originate from the mesenchyme and dermatomal spreading of segmental vitiligo are arguments propounded in favor of this hypothesis.17

The self-destruction hypothesis suggests that the intrinsic protective mechanisms that normally enable melanocytes to eliminate toxic intermediate products or metabolites on the melanogenesis path have been impaired in patients with vitiligo.18,19 There is evidence of increased oxidative stress over the whole epidermis of patients with vitiligo.20 Thus, free radicals affect melanin and cause membrane damage via lipid peroxidation reactions.21

The autoimmune hypothesis proposes a clinical relationship between vitiligo and several diseases believed to be autoimmune. Because the macrophage infiltration observed in vitiligo lesions is more pronounced on the perilesional skin, this hypothesis holds that macrophages may play a role in melanocyte removal.21 The Koebner phenomenon observed in vitiligo lends support to the critical role of trauma in the etiopathogenesis of the disease.

Although we could not explain the co-presence of vitiligo and glaucoma, we believe that it may result from the fact that both diseases are observed in tissues that have the same embryologic origin and etiology, perhaps vascular or neural disorders, excessive accumulation of free radicals, or the triggering of apoptosis. Dermatologists should be alert to the presence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo because glaucoma is an eye disease that progresses slowly and may lead to vision loss.

Vitiligo is an acquired idiopathic disease of unknown etiology. Characterized by depigmented maculae and melanocytic destruction, it usually presents in childhood or young adulthood. The incidence of vitiligo ranges from 0.5% to 2% globally and there is no racial or gender predilection.1

Patients with vitiligo may exhibit pigmentary abnormalities of the iris and retina.2 Noninflammatory depigmented lesions of the ocular fundus observed in vitiligo indicate a local loss of melanocytes.1 The fact that melanocytes are present not only in the skin and roots of the hair but also in the uvea and stria vascularis of the inner ear may explain the ophthalmologic disorders that accompany vitiligo.3 The term glaucoma refers to a large number of diseases that share a common feature: a distinctive and progressive optic neuropathy that may derive from various risks and is associated with a gradual loss of the visual field. If the disorder is not diagnosed and treated properly it could cause blindness.

Glaucoma is classified on the basis of the underlying abnormality that causes intraocular pressure (IOP) to rise. Glaucoma is first divided into open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma; glaucoma associated with developmental anomalies is then subdivided according to specific alterations.4

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms vitiligo and glaucoma revealed only 1 study examining the incidence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo.5 In the study reported here, we determined the presence of and possible risk factors for glaucoma in patients with vitiligo who had presented to the dermatology polyclinic.

Methods

We registered 49 patients diagnosed with vitiligo by clinical and Wood light examination and 20 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Patients who were using topical corticosteroid treatments for vitiligo lesions located on the face were excluded from the study due to the glaucoma-inducing effects of corticosteroids. Similarly, patients who received drugs with sympathetic and parasympathetic action that can cause glaucoma were excluded.

The patients received a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination that included visual acuity testing, refraction, IOP measurement, gonioscopy, and fundus examination. All patients and controls underwent visual field tests and optic nerve head analyses using a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Glaucoma was diagnosed based on fundus examination, IOP measurement, field of vision evaluation, and optic nerve head analysis.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research protocol was approved by the university hospital ethics committee.

Results

The study registered a total of 49 patients with vitiligo (28 female; 21 male) and 20 healthy controls (10 female; 10 male) with a variety of demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Mean (SD) IOP values were 13.83 (2.84) mm Hg for the right eye and 13.89 (2.60) mm Hg for the left eye in the vitiligo group. Values were 14.35 (2.56) mm Hg and 14.95 (2.92) mm Hg, respectively, in the control group. The IOP differences between the 2 groups were not statistically significant (P>.05).

Nine patients (18.4%) in the vitiligo group were found to have signs of normal-tension glaucoma (NTG). Optic nerve damage and vision loss occurs in the presence of normal IOP in NTG. There were no signs of NTG in the control group. Normal-tension glaucoma was diagnosed in the vitiligo group based on glaucomatous optic disc appearance, visual field defects, and structural analysis of the entire optic nerve head in confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. The NTG difference between the vitiligo and control groups was statistically significant (P=.04).

In the vitiligo group, of the 9 patients who had NTG, 6 had periorbital vitiligo lesions; the remaining 3 had none. Although patients who had periorbital lesions had a higher rate of glaucoma relative to the patients without periorbital lesions, the difference was not statistically significant (P>.05).

No statistically significant differences (P>.05) were found between patients with vitiligo with and without glaucoma in terms of age, sex, disease duration, family history of vitiligo, presence or absence of periorbital involvement, manner of involvement, percentage of the involved body areas, and IOP (Table 1).

Comment

Glaucoma is characterized by increased IOP, visual field loss, and changes in the optic nerve head. Although elevated IOP is common in ocular hypertension as well as in glaucoma, there is no glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertension. In NTG, on the other hand, glaucomatous visual field loss and optic nerve head changes occur without an increase in IOP.6 Normal-tension glaucoma is a particular type of open-angle glaucoma. It is believed that NTG and high-tension glaucoma induce optic nerve head damage through different means.7 Alternative theories have been put forth to account for the glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve head that occurs in NTG, despite normal or close to normal IOP. These theories include vascular disorders (eg, ischemia, which interrupts the orthograde or retrograde axonal transport), excessive accumulation of free radicals, triggering of apoptosis, and low resistance of lamina cribrosa.8

Although there are various studies exploring ocular symptoms in patients with vitiligo,9-15 only 1 study has examined the incidence of glaucoma in this group of patients.5 Biswas et al11 examined ocular signs in 100 patients with vitiligo and found that 23% of patients had hypopigmented foci in the iris, 18% had pigmentation in the anterior chamber, 11% had chorioretinal degeneration, 9% had hypopigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium, 5% had uveitis, and 34% were evaluated as normal. In this study, the authors concluded that there was a strong relationship between vitiligo and eye diseases.11 When Gopal et al9 compared the eye examinations of 150 vitiligo patients and 100 healthy controls, they found uveitis, iris, and retinal pigmentary abnormalities in 16% of the vitiligo patients (P<.001).

Rogosić et al5 examined the incidence of glaucoma in 42 patients with vitiligo and found primary open-angle glaucoma in 24 (57%) patients. The patients had a mean age of 56 years, mean disease duration of 13 years, and mean IOP of 18 mm Hg for the right eye and 17.5 mm Hg for the left eye. The incidence of glaucoma was significantly higher in patients with vitiligo (P<.001) and increased with disease duration.5

Similar studies, however, have failed to show a relationship between vitiligo and glaucoma. In a study that evaluated the retinal pigment epithelium and the optic nerve in patients with vitiligo, Perossini et al10 found that the fundus examination of the patients was perfectly normal.

In our study, we detected NTG in 18.4% of patients with vitiligo. We did not find a significant statistical difference between patients with and without glaucoma (Table 2). Rogosić et al5 found a significant relationship between age and glaucoma incidence, but we did not find such a relationship, which we believe is because the mean age of our patients was lower than the prior study.

In vitiligo, melanocytes are destroyed through an unknown mechanism. Although the cellular and molecular mechanisms causing melanocytic destruction have not yet been determined, various hypotheses have been put forward to explain the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo. Among these, the most commonly held hypotheses are the neural, self-destruction, and autoimmune hypotheses.16

Based on the observation that stress and serious trauma could precipitate or trigger the onset of vitiligo,16 the neural hypothesis holds that neurochemical mediators released from the edges of the nerve endings exert toxic effects on melanocytes. The fact that both melanocytes and choroidal pigment cells originate from the mesenchyme and dermatomal spreading of segmental vitiligo are arguments propounded in favor of this hypothesis.17

The self-destruction hypothesis suggests that the intrinsic protective mechanisms that normally enable melanocytes to eliminate toxic intermediate products or metabolites on the melanogenesis path have been impaired in patients with vitiligo.18,19 There is evidence of increased oxidative stress over the whole epidermis of patients with vitiligo.20 Thus, free radicals affect melanin and cause membrane damage via lipid peroxidation reactions.21

The autoimmune hypothesis proposes a clinical relationship between vitiligo and several diseases believed to be autoimmune. Because the macrophage infiltration observed in vitiligo lesions is more pronounced on the perilesional skin, this hypothesis holds that macrophages may play a role in melanocyte removal.21 The Koebner phenomenon observed in vitiligo lends support to the critical role of trauma in the etiopathogenesis of the disease.

Although we could not explain the co-presence of vitiligo and glaucoma, we believe that it may result from the fact that both diseases are observed in tissues that have the same embryologic origin and etiology, perhaps vascular or neural disorders, excessive accumulation of free radicals, or the triggering of apoptosis. Dermatologists should be alert to the presence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo because glaucoma is an eye disease that progresses slowly and may lead to vision loss.

1. Ortonne JP. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JB, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:947-973.

2. Ortonne JP, Bahadoran P, Fitzpatrick TB, et al. Hypomelanoses and hypermelanoses. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:836-881.

3. van den Wijngaard R, Wijngaard R, Wankowiczs-Kalinsa A, et al. Autoimmune melanocyte destruction in vitiligo. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1061-1067.

4. Shields MB, Ritch R, Krupin T. Classification of the glaucomas. In: Ritch R, Shields MB, Krupin T, eds. The Glaucomas. St Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co; 1996:717-725.

5. Rogosić V, Bojić L, Puizina-Ivić N, et al. Vitiligo and glaucoma–an association or a coincidence? a pilot study. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:21-26.

6. Anderson DR. Normal-tension glaucoma (low-tension glaucoma). Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(suppl 59):S97-S101.

7. Iwata K. Primary open angle glaucoma and low tension glaucoma–pathogenesis and mechanism of optic nerve damage [in Japanese]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;96:1501-1531.

8. Hitchings RA, Anderton SA. A comparative study of visual field defects seen in patients with low-tension glaucoma and chronic simple glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1983;67:818-821.

9. Gopal KV, Rama Rao GR, Kumar YH, et al. Vitiligo: a part of a systemic autoimmune process. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:162-165.

10. Perossini M, Turio E, Perossini T, et al. Vitiligo: ocular and electrophysiological findings. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:141-149.

11. Biswas G, Barbhuiya JN, Biswas MC, et al. Clinical pattern of ocular manifestations in vitiligo. J Indian Med Assoc. 2003;101:478-480.

12. Park S, Albert DM, Bolognia JL. Ocular manifestations of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:609-622.

13. Albert DM, Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB. Ocular abnormalities occurring with vitiligo. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:1145-1160.

14. Wagoner MD, Albert DM, Lerner AB, et al. New observations on vitiligo and ocular disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:16-26.

15. Cowan CL Jr, Halder RM, Grimes PE, et al. Ocular disturbances in vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:17-24.

16. Orecchia GE. Neural pathogenesis. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:142-150.

17. Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolf HH, et al. Disorders of melanin pigmentation. In: Bartels V, ed. Dermatology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2000:1013-1042.

18. Tüzün Y, Kotoğyan A, Aydemir EH, et al. Pigmentasyon bozuklukları. In: Baransü O. Dermatoloji. 2nd ed. Istanbul: Nobel Tıp Kitabevi; 1994:557-559.

19. Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Disturbances of pigmentation. In: Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000:1065-1068.

20. Schallreuter KU. Biochemical theory of vitiligo: a role of pteridines in pigmentation. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. London, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:151-159.

21. van den Wijngaard R, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, Le Poole C, et al. Local immune response in skin of generalized vitiligo patients. destruction of melanocytes is associated with the predominent presence of CLA+T cells at the perilesional site. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1299-1309.

1. Ortonne JP. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JB, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:947-973.

2. Ortonne JP, Bahadoran P, Fitzpatrick TB, et al. Hypomelanoses and hypermelanoses. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:836-881.

3. van den Wijngaard R, Wijngaard R, Wankowiczs-Kalinsa A, et al. Autoimmune melanocyte destruction in vitiligo. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1061-1067.

4. Shields MB, Ritch R, Krupin T. Classification of the glaucomas. In: Ritch R, Shields MB, Krupin T, eds. The Glaucomas. St Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co; 1996:717-725.

5. Rogosić V, Bojić L, Puizina-Ivić N, et al. Vitiligo and glaucoma–an association or a coincidence? a pilot study. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:21-26.

6. Anderson DR. Normal-tension glaucoma (low-tension glaucoma). Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(suppl 59):S97-S101.

7. Iwata K. Primary open angle glaucoma and low tension glaucoma–pathogenesis and mechanism of optic nerve damage [in Japanese]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;96:1501-1531.

8. Hitchings RA, Anderton SA. A comparative study of visual field defects seen in patients with low-tension glaucoma and chronic simple glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1983;67:818-821.

9. Gopal KV, Rama Rao GR, Kumar YH, et al. Vitiligo: a part of a systemic autoimmune process. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:162-165.

10. Perossini M, Turio E, Perossini T, et al. Vitiligo: ocular and electrophysiological findings. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:141-149.

11. Biswas G, Barbhuiya JN, Biswas MC, et al. Clinical pattern of ocular manifestations in vitiligo. J Indian Med Assoc. 2003;101:478-480.

12. Park S, Albert DM, Bolognia JL. Ocular manifestations of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:609-622.

13. Albert DM, Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB. Ocular abnormalities occurring with vitiligo. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:1145-1160.

14. Wagoner MD, Albert DM, Lerner AB, et al. New observations on vitiligo and ocular disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:16-26.

15. Cowan CL Jr, Halder RM, Grimes PE, et al. Ocular disturbances in vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:17-24.

16. Orecchia GE. Neural pathogenesis. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:142-150.

17. Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolf HH, et al. Disorders of melanin pigmentation. In: Bartels V, ed. Dermatology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2000:1013-1042.

18. Tüzün Y, Kotoğyan A, Aydemir EH, et al. Pigmentasyon bozuklukları. In: Baransü O. Dermatoloji. 2nd ed. Istanbul: Nobel Tıp Kitabevi; 1994:557-559.

19. Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Disturbances of pigmentation. In: Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000:1065-1068.

20. Schallreuter KU. Biochemical theory of vitiligo: a role of pteridines in pigmentation. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. London, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:151-159.

21. van den Wijngaard R, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, Le Poole C, et al. Local immune response in skin of generalized vitiligo patients. destruction of melanocytes is associated with the predominent presence of CLA+T cells at the perilesional site. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1299-1309.

Practice Points

- Patients with vitiligo may exhibit pigmentary abnormalities of the iris and retina.

- Normal-tension glaucoma may develop in patients with vitiligo.

- Glaucoma progresses slowly and may lead to vision loss; as a result, dermatologists should be alert to the presence of glaucoma in vitiligo patients.

Changing Treatment Landscape of Hepatitis C Virus Infection Among Penitentiary Inmates

The incidence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection increased markedly in the 1970s and 1980s. These increases were mainly attributable to blood transfusions and injection drug use.1,2 The blood supply was not screened for HCV before 1992 (now, HCV infection by blood transfusion is rare).2,3 Surveillance of the period 1992-2003 showed a substantial decrease in the incidence of acute hepatitis C cases, and the rate remained steady through 2010.2,3 Over the past 5 years, HCV has returned to national attention with a rising infection rate (2.5-fold increase during 2010-2013) and a rapid succession of FDA approvals of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs).4 Currently, the most prevalent mode of infection is injection drug use, accounting for > 50% of all cases of HCV infection and 84% of acute HCV infections.5

Baby boomers (people born between 1945 and 1965) account for three-fourths of the population currently living with chronic HCV infection resulting from past infection.6 Historically, rates of acute and chronic infection have been far higher for blacks than for whites and Hispanics.2,4,7,8 In 2004, that trend started to reverse, with the incidence in whites surpassing that in blacks.4 Recent reports have identified a new cohort of HCV-infected injection drug users (IDUs) who are young (aged ≤ 24 years) and white nonurban dwellers.5

HCV Infection Among High Risk Individuals

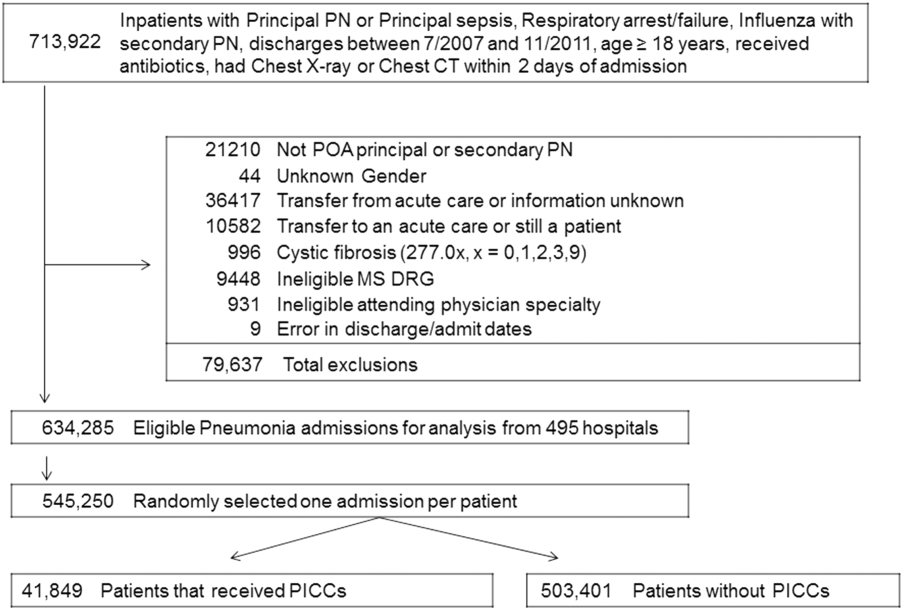

In the U.S., unlike in other parts of the world, HCV infection is more prevalent than hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.4,9,10 According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), about 2.7 million Americans have chronic HCV infection. However, NHANES surveys do not sample certain populations, including the incarcerated and the homeless, in whom infection rates are thought to be higher.11 The incarcerated, the largest institutionalized group, have the highest incidence: One in 3 is infected with HCV.12 This rate is attributable to high rates of injection drug use and other high-risk behaviors. Drug-related offenses account for 50% of federal prison incarceration.13 For IDUs, the HCV infection rate is as high as 70% to 90%. Despite widespread implementation of needle-exchange programs after the discovery of HIV in the 1980s, recent surveys have indicated that about one-third of 18- to 30-year-old active IDUs are infected with HCV.14

Penitentiary Inmates Infected With HCV

A 2015 search of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) electronic medical records at the U.S. Penitentiary Canaan (USP Canaan) found that out of a population of about 1,600 inmates, 182 (11%) had tested positive for HCV antibodies (anti-HCV). This percentage likely is an underestimation, because HCV testing is not mandatory, and many (45%-85%) of the infected are unaware of their HCV infection status.2 Most of the infected remain chronically infected and are not being treated.

Prevalence of HCV infection commonly refers to chronic HCV infection. The diagnosis of chronic HCV infection is established by presence of HCV RNA on polymerase chain reaction assays. Of the 182 inmates who tested positive for anti-HCV, 45 had their cases resolved (undetectable HCV RNA), 34 spontaneously, and the other 11 after treatment, primarily with peginterferon and ribavirin (pegINF/RBV) dual therapies. The remaining 137 who tested positive remained chronically infected. This chronically infected group represented 9% of the population of 1,600 inmates. Although the infection rate is significantly higher than that in the general population (1% incidence), the inmates’ true rate of infection in all probability is much higher.11

Earlier NHANES data showed HCV more prevalent in minorities, particularly blacks, compared with whites.2,7,8 At USP Canaan, however, the incidence of chronic HCV infection was 21% in whites (mean age, 42 years), 4% in blacks (mean age, 51 years), and 7% in Hispanics (mean age, 39 years). The lower rates in blacks and Hispanics could have resulted from a lack of awareness about getting tested or from having fewer opportunities to obtain medical care in the community before incarceration (the infection can remain asymptomatic for several decades).

HCV genotype 1 is the most common HCV genotype in the U.S.5,15 At USP Canaan, genotype 1 accounted for 56% of the cases of chronic HCV infection in whites, 90% in blacks, and 79% in Hispanics. The majority genotype was subtype 1a.

Of the 137 inmates with HCV co-infections, 8 (6%) had HIV/HCV co-infection, and 4 (3%) had HBV/HCV co-infection. Also, 7 (5%) were diabetic. According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (AASLD/IDSA) guidelines, patients with comorbidities are a high priority for treatment, as there is a high risk for complications, with liver fibrosis progressing more rapidly.16

Changing Landscape of HCV Treatment

Treatments for chronic HCV infection have never been more promising. There is the prospect of a cure with the new DAAs. These new medications are active against HCV and interfere with viral enzymes and other proteins essential for viral replication. Until recently, the mainstay of treatment for chronic HCV infection was pegINF/RBV. However, INF-based dual therapies were associated with high rates of adverse effects (AEs) and treatment discontinuation. In 2011, release of the protease inhibitors (PIs) boceprevir and telaprevir improved sustained virologic response (SVR) rates for treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1 from about 50% (pegINF/RBV dual therapies) to 70% to 75% (PI in combination with pegINF/RBV triple therapies). However, first-generation DAAs were INF-based, and their dosing was cumbersome.15,17-19

Starting with the 2013 approval of simeprevir (second-wave PI) and sofosbuvir (polymerase inhibitor), most patients’ SVR rates improved to 75% to 90%.20,21 Sustained virologic response rates were boosted to > 95% after the 2014 approval of Harvoni, coformulated ledispasvir (replication complex inhibitor) and sofosbuvir, and Viekira Pak, a combination of ombitasvir (replication complex inhibitor), paritaprevir (PI), and ritonavir (inhibitor of CYP3A4 enzyme) co-packaged with dasabuvir (polymerase inhibitor).22-24 In 2015, daclatasvir (replication complex inhibitor) was approved, followed in 2016 by Zepatier, coformulated elbasvir (replication complex inhibitor) and grazoprevir (PI). Harvoni has simplified the treatment regimen to 1 pill a day and shortened the duration of treatment to as few as 8 weeks for some

patients.25

The option of an all-oral, INF-free treatment regimen and the prospect of freedom from the HCV could not come at a more opportune time, given the aging of baby boomers with chronic HCV infection and the high rates of HCV and HIV infections contracted in the 1970s and 1980s. An estimated one-third of those infected is expected to develop cirrhosis within 20 years.26

Cost of HCV Treatment

The U.S. has the highest health care costs in the world—consuming 17% of the nation’s gross domestic product.27,28 Health care costs also have been steadily increasing in U.S. prisons because of the expanding and aging incarcerated population. The Eighth Amendment provides inmates with the constitutional right to health care. The BOP’s overall expense of pharmaceuticals for HCV treatment has soared in recent years. It was kept below $2 million in fiscal years 2010 and 2011 but more than doubled the next 2 years, to more than $4 million in 2012 and 2013, and increased in 2014 to about $6 million. Hepititis C treatment accounted for 3% of the BOP pharmaceutical budget in 2011 and 7% in 2014.29 Increased HCV pharmaceutical expenses were attributable to the introduction of DAAs. Even so, the majority of inmates with chronic HCV infection remained untreated.

Compared with DAA PIs, sofosbuvir is a game changer. Its all-oral, INF-free regimen makes treatment of chronic HCV infection more effective and safer. However, its cost is prohibitive, even in rich countries: A 12-week course costs $84,000, and Harvoni (ledispasvir/ sofosbuvir) costs $94,000.30,31 A generic version of sofosbuvir is not expected until 2025.32 Many studies have been conducted on the cost-effectiveness of these newer DAAs, but the picture is unclear, as the results were sensitive to drug price, drug efficacy (SVR rates vary with genotype and patient profile), quality of life after successful treatment, and the willingness-to-pay threshold.30 Ironically, treatment cost could be the primary barrier to HCV eradication.

At USP Canaan, 137 inmates with chronic HCV infection potentially could have benefited from treatment. A majority (91 inmates) were infected with HCV genotype 1; of the other 46 inmates, 12 had genotype 2, 18 had genotype 3, 2 had genotype 4, and 14 lacked genotyping.

The all-oral, INF-free regimen obviates the need for weekly injection, and treatment duration is shorter. The AASLD/IDSA treatment guidelines recommend all-oral, INF-free treatment regimens for all patients with genotype 1. Typically, treatment lasts 12 or 24 weeks, depending on presence or absence of liver cirrhosis, among other considerations.16

Because of the high cost of treating all inmates with chronic HCV infection, the large number of inmates who are asymptomatic, and the potential decrease in medication costs after the introduction of generic versions, inmates are being prioritized for treatment based primarily on staging (presence or absence of liver disease). The rationale for using staging for prioritization is that patients with chronic HCV infection and no or minimal fibrosis at presentation seem to progress slowly, and treatment possibly can be delayed or withheld; whereas patients with significant fibrosis (septal or bridging fibrosis) progress almost invariably to cirrhosis over a 10- to 20-year period, so antiviral treatment becomes urgent.33

APRI: Biomarker for Liver Fibrosis

A liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis. Although generally safe, it is costly. It is also subject to sampling error and examiner discrepancy, which lead to incorrect staging of fibrosis in 20% of patients.5,33 Alternatively, various biologic markers can be used to diagnose liver disease. The aspartate aminotransferase (AST) platelet ratio index (APRI) is a simple and useful index based on readily available laboratory results: AST level and platelet count. APRI correlated significantly with fibrosis stage in patients with chronic HCV infection.33

At USP Canaan, 16 (12%) of the 137 inmates with chronic HCV infection had an APRI higher than 1, and 5 of the 16 had an APRI higher than 2.

Conclusion

In coming years, treatment of chronic HCV infection will consume a more significant portion of the health care budget. As treatment becomes more efficacious and safer, the paradigm may shift from a stage-based strategy to a treat-all strategy. Possibly, more inmates will ask for treatment as the treatment burden lessens due to fewer treatment-associated AEs. However, despite the efficacy of HCV treatment, there is no reduction in the overall lifetime medical costs, because the offset in downstream direct medical costs (from successful treatment) is less than the cost of a cure.30

In the BOP, many challenges remain: HCV infection rates are expected to be high, treatment costs astronomical, resources limited, and treated patients may become reinfected if high-risk behavior continues. Patient education is, therefore, an important component of effective prevention and treatment strategies. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends HCV screening for all high-risk persons and a onetime screening for all baby boomers.34 Federal prisons offer HCV testing to all inmates with risk factors, when clinically indicated, or on

request.

All inmates with chronic HCV infection were being monitored for treatment prioritization, as some were at higher risk for complications or disease progression and required more urgent treatment.35 Ideally, all inmates should be treated, as incarcerated persons are at elevated risk for HCV transmission, and successful treatment would benefit public health by reducing infection rates in the community.16 However, resource constraints are a reality in health care, particularly among underserved populations, and this situation provides the rationale for screening, monitoring, and treatment prioritization. This step-by-step approach, which rests on sound clinical judgment, helps control the budget.

Click here for the digital edition.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR-19):1-39.

2. Ditah I, Ditah F, Devaki P, et al. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 through 2010. J Hepatol. 2014;60(4):691-698.

3. Daniels D, Grytdal S, Wasley A; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis - United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(3):1-27.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Viral Hepatitis and National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance—United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2013surveillance/pdfs/2013hepsurveillancerpt.pdf. Updated April 24, 2015. Accessed May 20, 2015.

5. Hepatitis C Online. Hepatitis C Online Website. http://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu. Accessed March 3, 2016.

6. Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-4):1-32.

7. Alter KJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(8):556-562.

8. Liu G, Holmberg SD, Kamili S, Xu F. Racial disparities in the proportion of current, unresolved hepatitis C virus infections in the United States, 2003-2010. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(8):1950-1957.

9. World Health Organization. Hepatitis B [fact sheet 204]. World Health Organization Website. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en. Updated July 2015. Accessed March 3, 2016.

10. World Health Organization. Hepatitis C [fact sheet 164]. World Health Organization Website. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en. Updated July 2015. Accessed March 3, 2016.

11. Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):293-300.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C and Incarceration. Publication No. 21-1306. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/PDFs/HepCIncarcerationFactSheet.pdf. October 2013. Accessed March 3, 2016.

13. Federal Bureau of Prisons. Inmate statistics: offenses. Federal Bureau of Prisons Website. http://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp. Updated January 30, 2016. Accessed March 3, 2016.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C FAQs for health professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/HCVfaq.htm. Updated January 8, 2016. Accessed March 4, 2016.

15. Saab S, Gordon SC, Park H, Sulkowski M, Ahmed A, Younossi Z. Cost-effectiveness analysis of sofosbuvir plus peginterferon/ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(6):657-675.

16. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America Website. http://hcvguidelines.org. Updated February 2016. Accessed March 4, 2016.

17. Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2405-2416.

18. Kwo PY. Boceprevir: a novel nonstructural 3 (NS3) protease inhibitor for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5(3):179-188.

19. Stahmeyer JT, Rossol S, Krauth C. Outcomes, costs and cost-effectiveness of treating

hepatitis C with direct acting antivirals. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(3):267-277.

20. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878-1887.

21. Fried MW, Buti M, Dore GJ, et al. Once-daily simeprevir (TMC435) with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in treatment-naïve genotype 1 hepatitis C: the randomized PILLAR study. Hepatology. 2013;58(6):1918-1929.

22. Ferenci P, Bernstein D, Lalezari J, et al; PEARL-III Study; PEARL-IV Study. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with or without ribavirin for HCV. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(21):1983-1992.

23. Feld JJ, Kowdley KV, Coakley E, et al. Treatment of HCV with ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(17):1594-1603.

24. Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, et al; ION-1 Investigators. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(20):1889-1898.

25. Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, et al; ION-3 Investigators. Ledipasvir and

sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(20):1879-1888.

26. Younossi ZM, Singer ME, Mir HM, Henry L, Hunt S. Impact of interferon free regimens on clinical and cost outcomes for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients. J Hepatol. 2014;60(3):530-537.

27. The Economist Don’t kill Obamacare. The Economist Website. http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21645730-supreme-court-considers-whether-gut-obamacare-evidence-mounting-law. Published May 7, 2015. Accessed March 4, 2016.

28. The World Bank. Health expenditure, total (% of GDP). The World Bank Website. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS. Published 2015. Accessed March 4, 2016.

29. Federal Bureau of Prisons, Health Services Division. 2015 BOP National P&T Minutes. Federal Bureau of Prisons intranet website. http://sallyport.bop.gov/co/hsd/pharmacy/docs/BOP_National_P&T_Minutes/2015%20BOP%20National%20P&T%20Minutes_Final.pdf. Published August 13, 2014. Accessed November 9, 2015.

30. Chhatwal J, Kanwal F, Roberts MS, Dunn MA. Cost-effectiveness and budget impact of hepatitis C virus treatment with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(6):397-406.

31. Sachs J. The drug that is bankrupting America. Huffington Post Website. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jeffrey-sachs/the-drug-that-is-bankrupt_b_6692340

.html. Published February 16, 2015. Updated April 18, 2015. Accessed March 4, 2016.

32. Hill A, Khoo S, Fortunak J, Simmons B, Ford N. Minimum costs for producing hepatitis C direct-acting antivirals for use in large-scale treatment access programs in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(7):928-936.

33. Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38(2):518-526.

34. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Hepatitis C: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Website. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/hepatitis-c-screening?ds=1&s=hepatitis c. Updated July 2015. Accessed March 4, 2016.

35. Federal Bureau of Prisons. Evaluation and Management of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection [clinical practice guidelines]. Federal Bureau of Prisons Website. http://www.bop.gov/resources/pdfs/hepatitis_c.pdf. Published July 2015. Accessed March 4, 2016.

The incidence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection increased markedly in the 1970s and 1980s. These increases were mainly attributable to blood transfusions and injection drug use.1,2 The blood supply was not screened for HCV before 1992 (now, HCV infection by blood transfusion is rare).2,3 Surveillance of the period 1992-2003 showed a substantial decrease in the incidence of acute hepatitis C cases, and the rate remained steady through 2010.2,3 Over the past 5 years, HCV has returned to national attention with a rising infection rate (2.5-fold increase during 2010-2013) and a rapid succession of FDA approvals of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs).4 Currently, the most prevalent mode of infection is injection drug use, accounting for > 50% of all cases of HCV infection and 84% of acute HCV infections.5

Baby boomers (people born between 1945 and 1965) account for three-fourths of the population currently living with chronic HCV infection resulting from past infection.6 Historically, rates of acute and chronic infection have been far higher for blacks than for whites and Hispanics.2,4,7,8 In 2004, that trend started to reverse, with the incidence in whites surpassing that in blacks.4 Recent reports have identified a new cohort of HCV-infected injection drug users (IDUs) who are young (aged ≤ 24 years) and white nonurban dwellers.5

HCV Infection Among High Risk Individuals

In the U.S., unlike in other parts of the world, HCV infection is more prevalent than hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.4,9,10 According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), about 2.7 million Americans have chronic HCV infection. However, NHANES surveys do not sample certain populations, including the incarcerated and the homeless, in whom infection rates are thought to be higher.11 The incarcerated, the largest institutionalized group, have the highest incidence: One in 3 is infected with HCV.12 This rate is attributable to high rates of injection drug use and other high-risk behaviors. Drug-related offenses account for 50% of federal prison incarceration.13 For IDUs, the HCV infection rate is as high as 70% to 90%. Despite widespread implementation of needle-exchange programs after the discovery of HIV in the 1980s, recent surveys have indicated that about one-third of 18- to 30-year-old active IDUs are infected with HCV.14

Penitentiary Inmates Infected With HCV

A 2015 search of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) electronic medical records at the U.S. Penitentiary Canaan (USP Canaan) found that out of a population of about 1,600 inmates, 182 (11%) had tested positive for HCV antibodies (anti-HCV). This percentage likely is an underestimation, because HCV testing is not mandatory, and many (45%-85%) of the infected are unaware of their HCV infection status.2 Most of the infected remain chronically infected and are not being treated.

Prevalence of HCV infection commonly refers to chronic HCV infection. The diagnosis of chronic HCV infection is established by presence of HCV RNA on polymerase chain reaction assays. Of the 182 inmates who tested positive for anti-HCV, 45 had their cases resolved (undetectable HCV RNA), 34 spontaneously, and the other 11 after treatment, primarily with peginterferon and ribavirin (pegINF/RBV) dual therapies. The remaining 137 who tested positive remained chronically infected. This chronically infected group represented 9% of the population of 1,600 inmates. Although the infection rate is significantly higher than that in the general population (1% incidence), the inmates’ true rate of infection in all probability is much higher.11

Earlier NHANES data showed HCV more prevalent in minorities, particularly blacks, compared with whites.2,7,8 At USP Canaan, however, the incidence of chronic HCV infection was 21% in whites (mean age, 42 years), 4% in blacks (mean age, 51 years), and 7% in Hispanics (mean age, 39 years). The lower rates in blacks and Hispanics could have resulted from a lack of awareness about getting tested or from having fewer opportunities to obtain medical care in the community before incarceration (the infection can remain asymptomatic for several decades).

HCV genotype 1 is the most common HCV genotype in the U.S.5,15 At USP Canaan, genotype 1 accounted for 56% of the cases of chronic HCV infection in whites, 90% in blacks, and 79% in Hispanics. The majority genotype was subtype 1a.

Of the 137 inmates with HCV co-infections, 8 (6%) had HIV/HCV co-infection, and 4 (3%) had HBV/HCV co-infection. Also, 7 (5%) were diabetic. According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (AASLD/IDSA) guidelines, patients with comorbidities are a high priority for treatment, as there is a high risk for complications, with liver fibrosis progressing more rapidly.16

Changing Landscape of HCV Treatment

Treatments for chronic HCV infection have never been more promising. There is the prospect of a cure with the new DAAs. These new medications are active against HCV and interfere with viral enzymes and other proteins essential for viral replication. Until recently, the mainstay of treatment for chronic HCV infection was pegINF/RBV. However, INF-based dual therapies were associated with high rates of adverse effects (AEs) and treatment discontinuation. In 2011, release of the protease inhibitors (PIs) boceprevir and telaprevir improved sustained virologic response (SVR) rates for treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1 from about 50% (pegINF/RBV dual therapies) to 70% to 75% (PI in combination with pegINF/RBV triple therapies). However, first-generation DAAs were INF-based, and their dosing was cumbersome.15,17-19

Starting with the 2013 approval of simeprevir (second-wave PI) and sofosbuvir (polymerase inhibitor), most patients’ SVR rates improved to 75% to 90%.20,21 Sustained virologic response rates were boosted to > 95% after the 2014 approval of Harvoni, coformulated ledispasvir (replication complex inhibitor) and sofosbuvir, and Viekira Pak, a combination of ombitasvir (replication complex inhibitor), paritaprevir (PI), and ritonavir (inhibitor of CYP3A4 enzyme) co-packaged with dasabuvir (polymerase inhibitor).22-24 In 2015, daclatasvir (replication complex inhibitor) was approved, followed in 2016 by Zepatier, coformulated elbasvir (replication complex inhibitor) and grazoprevir (PI). Harvoni has simplified the treatment regimen to 1 pill a day and shortened the duration of treatment to as few as 8 weeks for some

patients.25

The option of an all-oral, INF-free treatment regimen and the prospect of freedom from the HCV could not come at a more opportune time, given the aging of baby boomers with chronic HCV infection and the high rates of HCV and HIV infections contracted in the 1970s and 1980s. An estimated one-third of those infected is expected to develop cirrhosis within 20 years.26

Cost of HCV Treatment

The U.S. has the highest health care costs in the world—consuming 17% of the nation’s gross domestic product.27,28 Health care costs also have been steadily increasing in U.S. prisons because of the expanding and aging incarcerated population. The Eighth Amendment provides inmates with the constitutional right to health care. The BOP’s overall expense of pharmaceuticals for HCV treatment has soared in recent years. It was kept below $2 million in fiscal years 2010 and 2011 but more than doubled the next 2 years, to more than $4 million in 2012 and 2013, and increased in 2014 to about $6 million. Hepititis C treatment accounted for 3% of the BOP pharmaceutical budget in 2011 and 7% in 2014.29 Increased HCV pharmaceutical expenses were attributable to the introduction of DAAs. Even so, the majority of inmates with chronic HCV infection remained untreated.

Compared with DAA PIs, sofosbuvir is a game changer. Its all-oral, INF-free regimen makes treatment of chronic HCV infection more effective and safer. However, its cost is prohibitive, even in rich countries: A 12-week course costs $84,000, and Harvoni (ledispasvir/ sofosbuvir) costs $94,000.30,31 A generic version of sofosbuvir is not expected until 2025.32 Many studies have been conducted on the cost-effectiveness of these newer DAAs, but the picture is unclear, as the results were sensitive to drug price, drug efficacy (SVR rates vary with genotype and patient profile), quality of life after successful treatment, and the willingness-to-pay threshold.30 Ironically, treatment cost could be the primary barrier to HCV eradication.

At USP Canaan, 137 inmates with chronic HCV infection potentially could have benefited from treatment. A majority (91 inmates) were infected with HCV genotype 1; of the other 46 inmates, 12 had genotype 2, 18 had genotype 3, 2 had genotype 4, and 14 lacked genotyping.

The all-oral, INF-free regimen obviates the need for weekly injection, and treatment duration is shorter. The AASLD/IDSA treatment guidelines recommend all-oral, INF-free treatment regimens for all patients with genotype 1. Typically, treatment lasts 12 or 24 weeks, depending on presence or absence of liver cirrhosis, among other considerations.16

Because of the high cost of treating all inmates with chronic HCV infection, the large number of inmates who are asymptomatic, and the potential decrease in medication costs after the introduction of generic versions, inmates are being prioritized for treatment based primarily on staging (presence or absence of liver disease). The rationale for using staging for prioritization is that patients with chronic HCV infection and no or minimal fibrosis at presentation seem to progress slowly, and treatment possibly can be delayed or withheld; whereas patients with significant fibrosis (septal or bridging fibrosis) progress almost invariably to cirrhosis over a 10- to 20-year period, so antiviral treatment becomes urgent.33

APRI: Biomarker for Liver Fibrosis

A liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis. Although generally safe, it is costly. It is also subject to sampling error and examiner discrepancy, which lead to incorrect staging of fibrosis in 20% of patients.5,33 Alternatively, various biologic markers can be used to diagnose liver disease. The aspartate aminotransferase (AST) platelet ratio index (APRI) is a simple and useful index based on readily available laboratory results: AST level and platelet count. APRI correlated significantly with fibrosis stage in patients with chronic HCV infection.33

At USP Canaan, 16 (12%) of the 137 inmates with chronic HCV infection had an APRI higher than 1, and 5 of the 16 had an APRI higher than 2.

Conclusion

In coming years, treatment of chronic HCV infection will consume a more significant portion of the health care budget. As treatment becomes more efficacious and safer, the paradigm may shift from a stage-based strategy to a treat-all strategy. Possibly, more inmates will ask for treatment as the treatment burden lessens due to fewer treatment-associated AEs. However, despite the efficacy of HCV treatment, there is no reduction in the overall lifetime medical costs, because the offset in downstream direct medical costs (from successful treatment) is less than the cost of a cure.30

In the BOP, many challenges remain: HCV infection rates are expected to be high, treatment costs astronomical, resources limited, and treated patients may become reinfected if high-risk behavior continues. Patient education is, therefore, an important component of effective prevention and treatment strategies. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends HCV screening for all high-risk persons and a onetime screening for all baby boomers.34 Federal prisons offer HCV testing to all inmates with risk factors, when clinically indicated, or on

request.

All inmates with chronic HCV infection were being monitored for treatment prioritization, as some were at higher risk for complications or disease progression and required more urgent treatment.35 Ideally, all inmates should be treated, as incarcerated persons are at elevated risk for HCV transmission, and successful treatment would benefit public health by reducing infection rates in the community.16 However, resource constraints are a reality in health care, particularly among underserved populations, and this situation provides the rationale for screening, monitoring, and treatment prioritization. This step-by-step approach, which rests on sound clinical judgment, helps control the budget.

Click here for the digital edition.

The incidence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection increased markedly in the 1970s and 1980s. These increases were mainly attributable to blood transfusions and injection drug use.1,2 The blood supply was not screened for HCV before 1992 (now, HCV infection by blood transfusion is rare).2,3 Surveillance of the period 1992-2003 showed a substantial decrease in the incidence of acute hepatitis C cases, and the rate remained steady through 2010.2,3 Over the past 5 years, HCV has returned to national attention with a rising infection rate (2.5-fold increase during 2010-2013) and a rapid succession of FDA approvals of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs).4 Currently, the most prevalent mode of infection is injection drug use, accounting for > 50% of all cases of HCV infection and 84% of acute HCV infections.5

Baby boomers (people born between 1945 and 1965) account for three-fourths of the population currently living with chronic HCV infection resulting from past infection.6 Historically, rates of acute and chronic infection have been far higher for blacks than for whites and Hispanics.2,4,7,8 In 2004, that trend started to reverse, with the incidence in whites surpassing that in blacks.4 Recent reports have identified a new cohort of HCV-infected injection drug users (IDUs) who are young (aged ≤ 24 years) and white nonurban dwellers.5

HCV Infection Among High Risk Individuals

In the U.S., unlike in other parts of the world, HCV infection is more prevalent than hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.4,9,10 According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), about 2.7 million Americans have chronic HCV infection. However, NHANES surveys do not sample certain populations, including the incarcerated and the homeless, in whom infection rates are thought to be higher.11 The incarcerated, the largest institutionalized group, have the highest incidence: One in 3 is infected with HCV.12 This rate is attributable to high rates of injection drug use and other high-risk behaviors. Drug-related offenses account for 50% of federal prison incarceration.13 For IDUs, the HCV infection rate is as high as 70% to 90%. Despite widespread implementation of needle-exchange programs after the discovery of HIV in the 1980s, recent surveys have indicated that about one-third of 18- to 30-year-old active IDUs are infected with HCV.14

Penitentiary Inmates Infected With HCV

A 2015 search of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) electronic medical records at the U.S. Penitentiary Canaan (USP Canaan) found that out of a population of about 1,600 inmates, 182 (11%) had tested positive for HCV antibodies (anti-HCV). This percentage likely is an underestimation, because HCV testing is not mandatory, and many (45%-85%) of the infected are unaware of their HCV infection status.2 Most of the infected remain chronically infected and are not being treated.

Prevalence of HCV infection commonly refers to chronic HCV infection. The diagnosis of chronic HCV infection is established by presence of HCV RNA on polymerase chain reaction assays. Of the 182 inmates who tested positive for anti-HCV, 45 had their cases resolved (undetectable HCV RNA), 34 spontaneously, and the other 11 after treatment, primarily with peginterferon and ribavirin (pegINF/RBV) dual therapies. The remaining 137 who tested positive remained chronically infected. This chronically infected group represented 9% of the population of 1,600 inmates. Although the infection rate is significantly higher than that in the general population (1% incidence), the inmates’ true rate of infection in all probability is much higher.11

Earlier NHANES data showed HCV more prevalent in minorities, particularly blacks, compared with whites.2,7,8 At USP Canaan, however, the incidence of chronic HCV infection was 21% in whites (mean age, 42 years), 4% in blacks (mean age, 51 years), and 7% in Hispanics (mean age, 39 years). The lower rates in blacks and Hispanics could have resulted from a lack of awareness about getting tested or from having fewer opportunities to obtain medical care in the community before incarceration (the infection can remain asymptomatic for several decades).

HCV genotype 1 is the most common HCV genotype in the U.S.5,15 At USP Canaan, genotype 1 accounted for 56% of the cases of chronic HCV infection in whites, 90% in blacks, and 79% in Hispanics. The majority genotype was subtype 1a.

Of the 137 inmates with HCV co-infections, 8 (6%) had HIV/HCV co-infection, and 4 (3%) had HBV/HCV co-infection. Also, 7 (5%) were diabetic. According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (AASLD/IDSA) guidelines, patients with comorbidities are a high priority for treatment, as there is a high risk for complications, with liver fibrosis progressing more rapidly.16

Changing Landscape of HCV Treatment

Treatments for chronic HCV infection have never been more promising. There is the prospect of a cure with the new DAAs. These new medications are active against HCV and interfere with viral enzymes and other proteins essential for viral replication. Until recently, the mainstay of treatment for chronic HCV infection was pegINF/RBV. However, INF-based dual therapies were associated with high rates of adverse effects (AEs) and treatment discontinuation. In 2011, release of the protease inhibitors (PIs) boceprevir and telaprevir improved sustained virologic response (SVR) rates for treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1 from about 50% (pegINF/RBV dual therapies) to 70% to 75% (PI in combination with pegINF/RBV triple therapies). However, first-generation DAAs were INF-based, and their dosing was cumbersome.15,17-19

Starting with the 2013 approval of simeprevir (second-wave PI) and sofosbuvir (polymerase inhibitor), most patients’ SVR rates improved to 75% to 90%.20,21 Sustained virologic response rates were boosted to > 95% after the 2014 approval of Harvoni, coformulated ledispasvir (replication complex inhibitor) and sofosbuvir, and Viekira Pak, a combination of ombitasvir (replication complex inhibitor), paritaprevir (PI), and ritonavir (inhibitor of CYP3A4 enzyme) co-packaged with dasabuvir (polymerase inhibitor).22-24 In 2015, daclatasvir (replication complex inhibitor) was approved, followed in 2016 by Zepatier, coformulated elbasvir (replication complex inhibitor) and grazoprevir (PI). Harvoni has simplified the treatment regimen to 1 pill a day and shortened the duration of treatment to as few as 8 weeks for some

patients.25

The option of an all-oral, INF-free treatment regimen and the prospect of freedom from the HCV could not come at a more opportune time, given the aging of baby boomers with chronic HCV infection and the high rates of HCV and HIV infections contracted in the 1970s and 1980s. An estimated one-third of those infected is expected to develop cirrhosis within 20 years.26

Cost of HCV Treatment