User login

Biceps Tenodesis and Superior Labrum Anterior to Posterior (SLAP) Tears

Injuries of the superior labrum–biceps complex (SLBC) have been recognized as a cause of shoulder pain since they were first described by Andrews and colleagues1 in 1985. Superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears are relatively uncommon injuries of the shoulder, and their true incidence is difficult to establish. However, recently there has been a significant increase in the reported incidence and operative treatment of SLAP tears.2 SLAP tears can occur in isolation, but they are commonly seen in association with other shoulder lesions, including rotator cuff tear, Bankart lesion, glenohumeral arthritis, acromioclavicular joint pathology, and subacromial impingement.

Although SLAP tears are well described and classified,3-6 our understanding of symptomatic SLAP tears and of their contribution to glenohumeral instability is limited. Diagnosing a SLAP tear on the basis of history and physical examination is a clinical challenge. Pain is the most common presentation of SLAP tears, though localization and characterization of pain are variable and nonspecific.7 The mechanism of injury is helpful in acute presentation (traction injury; fall on outstretched, abducted arm), but an overhead athlete may present with no distinct mechanism other than chronic, repetitive use of the shoulder.8-11 Numerous provocative physical examination tests have been used to assist in the diagnosis of SLAP tear, yet there is no consensus regarding the ideal physical examination test, with high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy.12-14 Magnetic resonance arthrography, the gold standard imaging modality, is highly sensitive and specific (>95%) for diagnosing SLAP tears.

SLAP tear management is based on lesion type and severity, age, functional demands, and presence of coexisting intra-articular lesions. Management options include nonoperative treatment, débridement or repair of SLBC, biceps tenotomy, and biceps tenodesis.15-19

In this 5-point review, we present an evidence-based analysis of the role of the SLBC in glenohumeral stability and the role of biceps tenodesis in the management of SLAP tears.

1. Role of SLBC in stability of glenohumeral joint

The anatomy of the SLBC has been well described,20,21 and there is consensus that SLBC pathology can be a source of shoulder pain. The superior labrum is relatively more mobile than the rest of the glenoid labrum, and it provides attachment to the long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) and the superior glenohumeral and middle glenohumeral ligaments.

The functional role of the SLBC in glenohumeral stability and its contribution to the pathogenesis of shoulder instability are not clearly defined. Our understanding of SLBC function is largely derived from simulated cadaveric experiments of SLAP tears. Controlled laboratory studies with simulated type II SLAP tears in cadavers have shown significantly increased glenohumeral translation in the anterior-posterior and superior-inferior directions, suggesting a role of the superior labrum in maintaining glenohumeral stability.22-26 Interestingly, there is conflicting evidence regarding restoration of normal glenohumeral translation in cadaveric shoulders after repair of simulated SLAP lesions in the presence or absence of simulated anterior capsular laxity.22,25-27 However, it is important to understand the limitations of cadaveric experiments in order to appreciate and truly comprehend the results of these experiments. There are inconsistencies in the size of simulated type II SLAP lesions in different studies, which can affect the degree of glenohumeral translation and the results of repair.23-25,28 The amount of glenohumeral translation noticed after simulated SLAP tears in cadavers, though statistically significant, is small in amplitude, and its relevance may not translate to a clinically significant level. The impact of dynamic components of stability (eg, rotator cuff muscles), capsular stretch, and other in vivo variables that affect glenohumeral stability are unaccounted for during cadaveric experiments.

LHBT is a recognized cause of shoulder pain, but its contribution to shoulder stability is a point of continued debate. According to one school of thought, LHBT is a vestigial structure that can be sacrificed without any loss of stability. Another school of thought holds that LHBT is an important active stabilizer of the glenohumeral joint. Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that loading the LHBT decreases glenohumeral translation and rotational range of motion, especially in lower and mid ranges of abduction.23,29,30 Furthermore, LHBT contributes to anterior glenohumeral stability by resisting torsional forces in the abducted and externally rotated shoulder and reducing stress on the inferior glenohumeral ligaments.31-33 Strauss and colleagues22 recently found that simulated anterior and posterior type II SLAP lesions in cadaveric shoulders increased glenohumeral translation in all planes, and biceps tenodesis did not further worsen this abnormal glenohumeral translation. Furthermore, repair of posterior SLAP lesions along with biceps tenodesis restored abnormal glenohumeral translation with no significant difference from the baseline in any plane of motion. Again, the limitations of cadaveric studies should be considered when interpreting these results and applying them clinically.

2. Biceps tenodesis as primary treatment for SLAP tears

A growing body of evidence suggests that primary tenodesis of LHBT may be an effective alternative treatment to SLAP repairs in select patients.34-36 However, the evidence is weak, and high-quality studies comparing SLAP repair and primary biceps tenodesis are required in order to make a strong recommendation for one technique over another. Gupta and colleagues35 retrospectively analyzed 28 cases of concomitant SLAP tear and biceps tendonitis treated with primary open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There was significant improvement in patients’ functional outcome scores postoperatively [SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation), ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons shoulder index), SST (Simple Shoulder Test), VAS (visual analog scale), and SF-12 (Short Form-12)]. In addition, 80% of patients were satisfied with their outcome. Mean age was 43.7 years. Forty-two percent of patients had a worker’s compensation claim. Interestingly, 15 patients in this cohort had a type I SLAP tear. Boileau and colleagues34 prospectively followed 25 cases of type II SLAP tear treated with either SLAP repair (10 patients; mean age, 37 years) or primary arthroscopic biceps tenodesis (15 patients; mean age, 52 years). Compared with the SLAP repair group, the biceps tenodesis group had significantly higher rates of satisfaction and return to previous level of sports participation. However, group assignments were nonrandomized, and the decision to treat a patient with SLAP repair versus biceps tenodesis was made by the senior surgeon purely on the basis of age (SLAP repair for patients under 30 years). Ek and colleagues36 retrospectively compared the cases of 10 patients who underwent SLAP repair (mean age, 32 years) and 15 who underwent biceps tenodesis (mean age, 47 years) for type II SLAP tear. There was no significant difference between the groups with respect to outcome scores, return to play or preinjury activity level, or complications.

There continues to be significant debate as to which patient will benefit from primary SLAP repair versus biceps tenodesis. Multiple factors are involved: age, presence of associated shoulder pathology, occupation, preinjury activity level, and worker’s compensation status. Age has convincingly been shown to affect the outcomes of treatment of type II SLAP tears.34,35,37-40 There is consensus that patients over age 40 years will benefit from primary biceps tenodesis for SLAP tears. However, the evidence for this recommendation is weak.

3. Biceps tenodesis and failed SLAP repair

The definition of a failed SLAP repair is not well documented in the literature, but dissatisfaction after SLAP repair can result from continued shoulder pain, poor shoulder function, or inability to return to preinjury functional level.15,41 The etiologic determination and treatment of a failed SLAP repair are challenging, and outcomes of revision SLAP repair are not very promising.42,43 Biceps tenodesis has been proposed as an alternative treatment to revision SLAP repair for failed SLAP repair. McCormick and colleagues41 prospectively evaluated 42 patients (mean age, 39.2 years; minimum follow-up, 2 years) with failed type II SLAP repairs that were treated with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There was significant improvement in ASES, SANE, and Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI) outcome scores and in postoperative shoulder range of motion at a mean follow-up of 3.6 years. One patient had transient musculocutaneous neurapraxia after surgery. In a retrospective cohort study, Gupta and colleagues44 found significant improvement in ASES, SANE, SST, SF-12, and VAS outcome scores in 11 patients who underwent open subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed arthroscopic SLAP repair (mean age at surgery, 40 years; mean follow-up, 26 months). Three of the 11 patients had worker’s compensation claims, and there were no complications and no revision surgeries required after biceps tenodesis. Werner and colleagues16 retrospectively evaluated 17 patients who underwent biceps tenodesis for failed SLAP repair (mean age, 39 years; minimum follow-up, 2 years). Twenty-nine percent of patients had worker’s compensation claims. Compared with the contralateral shoulder, the treated shoulder had better postoperative ASES, SANE, SST, and Veteran RAND 36-item health survey outcome scores; range of motion was near normal.

There are no high-quality studies comparing revision SLAP repair and biceps tenodesis in the management of failed SLAP repair.16,41-44 Case series studies have found improved outcomes and pain relief after biceps tenodesis for failed SLAP repair, but the quality of evidence has been poor (level IV evidence).16,41-44 The senior author recommends treating failed SLAP repairs with biceps tenodesis.

4. Biceps tenodesis as treatment option for SLAP tear in overhead throwing athletes

Biceps tenodesis is a potential alternative treatment to SLAP repair in overhead throwing athletes. Although outcome scores and satisfaction rates after SLAP repair are high in overhead athletes, the rates of return to sport are relatively low, especially in baseball players.38,45-47 In a level III cohort study, Boileau and colleagues34 found that 13 (87%) of 15 patients with type II SLAP tears, including 8 overhead athletes, had returned to their previous level of activity by a mean of 30 months after biceps tenodesis. In contrast, only 2 of 10 patients returned to their previous level of activity after SLAP repair. Interestingly, 3 patients who underwent biceps tenodesis for failed SLAP repair returned to overhead sports. Schöffl and colleagues48 reported on the outcomes of biceps tenodesis for SLAP lesions in 6 high-level rock climbers. By a mean follow-up of 6 months, all 6 patients had returned to their previous level of climbing. Their satisfaction rate was 96.8%. Gupta and colleagues35 reported on a cohort of 28 patients who underwent biceps tenodesis for SLAP tears and concomitant biceps tendonitis. Of the 8 athletes in the group, 5 were able to return to their previous level of play, and 1 was able to return to a lower level of sporting activity. There was significant improvement from preoperative to postoperative scores on ASES, SST, SANE, VAS, SF-12 overall, and SF-12 components.

Chalmers and colleagues49 recently described motion analyses with simultaneous surface electromyographic measurements in 18 baseball pitchers. Of these 18 players, 7 were uninjured (controls), 6 were pitching after SLAP repair, and 5 were pitching after subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There were no significant differences between controls and postoperative patients with respect to pitching kinematics. Interestingly, compared with the controls and the patients who underwent open biceps tenodesis, the patients who underwent SLAP repair had altered patterns of thoracic rotation during pitching. However, the clinical significance of this finding and the impact of this finding on pitching efficacy are not currently known.

Biceps tenodesis as a primary procedure for type II SLAP lesion in an overhead athlete is a concept in evolution. Increasing evidence suggests a role for primary biceps tenodesis in an overhead athlete with type II SLAP lesion and concomitant biceps pathology. However, this evidence is of poor quality, and the strength of the recommendation is weak. Still to be determined is whether return to preinjury performance level is better with primary biceps tenodesis or with SLAP repair in overhead athletes with type II SLAP lesion. As per the senior author’s treatment algorithm, we prefer SLAP repair for overhead athletes with type II SLAP tears and reserve biceps tenodesis for cases involving significant biceps pathology and/or clinical symptoms involving the bicipital groove consistent with extra-articular biceps pain.

5. Biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP tear in contact athletes and occupations demanding heavy labor (blue-collar jobs)

SLAP tears are less common in contact athletes, and there is general agreement that SLAP repair outcomes are better in contact athletes than in overhead athletes. In a retrospective review of 18 rugby players with SLAP tears, Funk and Snow50 reported excellent results and quicker return to sport after SLAP repair. Patients with isolated SLAP tears had the earliest return to play. Enad and colleagues51 reported SLAP repair outcomes in an active military population. SLAP tears are more common in the military versus the general population because of the unique physical demands placed on military personnel. The authors retrospectively reviewed 27 cases of type II SLAP tears treated with SLAP repair and suture anchors. Outcomes were measured at a mean of 30.5 months after surgery. Twenty-four (89%) of the 27 patients had good to excellent results, and 94% had returned to active duty by a mean of 4.4 months after SLAP repair.

Given the poor-quality evidence in the literature, we believe that biceps tenodesis should be reserved for revision surgery in contact athletes. There is insufficient evidence to recommend biceps tenodesis as primary treatment for type II SLAP tears in contact athletes. SLAP repair should be performed for primary SLAP lesions in contact athletes and for patients in physically demanding professions (eg, military, laborer, weightlifter).

Conclusion

SLAP tears can result in persistent shoulder pain and dysfunction. SLAP tear management depends on lesion type and severity, age, and functional demands. SLAP repair is the treatment of choice for type II SLAP lesions in young, active patients. Biceps tenodesis is a preferred alternative to SLAP repair in failed SLAP repair and in type II SLAP patients who are older than 40 years and who are less active and have a worker’s compensation claim. These recommendations are based on poor-quality evidence. There is an unmet need for randomized clinical studies comparing SLAP repair with biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP tears in different patient populations so as to optimize the current decision-making algorithm for SLAP tears.

1. Andrews JR, Carson WG Jr, McLeod WD. Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(5):337-341.

2. Weber SC, Martin DF, Seiler JG 3rd, Harrast JJ. Superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: incidence rates, complications, and outcomes as reported by American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery. Part II candidates. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1538-1543.

3. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):274-279.

4. Morgan CD, Burkhart SS, Palmeri M, Gillespie M. Type II SLAP lesions: three subtypes and their relationships to superior instability and rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(6):553-565.

5. Powell SE, Nord KD, Ryu RKN. The diagnosis, classification, and treatment of SLAP lesions. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2012;20(1):46-56.

6. Maffet MW, Gartsman GM, Moseley B. Superior labrum-biceps tendon complex lesions of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(1):93-98.

7. Kim TK, Queale WS, Cosgarea AJ, McFarland EG. Clinical features of the different types of SLAP lesions: an analysis of one hundred and thirty-nine cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(1):66-71.

8. Abrams GD, Safran MR. Diagnosis and management of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(5):311-318.

9. Keener JD, Brophy RH. Superior labral tears of the shoulder: pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(10):627-637.

10. Abrams GD, Hussey KE, Harris JD, Cole BJ. Clinical results of combined meniscus and femoral osteochondral allograft transplantation: minimum 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(8):964-970.e1.

11. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):404-420.

12. Virk MS, Arciero RA. Superior labrum anterior to posterior tears and glenohumeral instability. Instr Course Lect. 2013;62:501-514.

13. Calvert E, Chambers GK, Regan W, Hawkins RH, Leith JM. Special physical examination tests for superior labrum anterior posterior shoulder tears are clinically limited and invalid: a diagnostic systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):558-563.

14. Jones GL, Galluch DB. Clinical assessment of superior glenoid labral lesions: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:45-51.

15. Werner BC, Brockmeier SF, Miller MD. Etiology, diagnosis, and management of failed SLAP repair. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(9):554-565.

16. Werner BC, Pehlivan HC, Hart JM, et al. Biceps tenodesis is a viable option for salvage of failed SLAP repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(8):e179-e184.

17. Erickson J, Lavery K, Monica J, Gatt C, Dhawan A. Surgical treatment of symptomatic superior labrum anterior-posterior tears in patients older than 40 years: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1274-1282.

18. Huri G, Hyun YS, Garbis NG, McFarland EG. Treatment of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions: a literature review. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48(3):290-297.

19. Li X, Lin TJ, Jager M, et al. Management of type II superior labrum anterior posterior lesions: a review of the literature. Orthop Rev. 2010;2(1):e6.

20. Cooper DE, Arnoczky SP, O’Brien SJ, Warren RF, DiCarlo E, Allen AA. Anatomy, histology, and vascularity of the glenoid labrum. An anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(1):46-52.

21. Vangsness CT, Jorgenson SS, Watson T, Johnson DL. The origin of the long head of the biceps from the scapula and glenoid labrum. An anatomical study of 100 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(6):951-954.

22. Strauss EJ, Salata MJ, Sershon RA, et al. Role of the superior labrum after biceps tenodesis in glenohumeral stability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):485-491.

23. Pagnani MJ, Deng XH, Warren RF, Torzilli PA, Altchek DW. Effect of lesions of the superior portion of the glenoid labrum on glenohumeral translation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):1003-1010.

24. McMahon PJ, Burkart A, Musahl V, Debski RE. Glenohumeral translations are increased after a type II superior labrum anterior-posterior lesion: a cadaveric study of severity of passive stabilizer injury. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(1):39-44.

25. Burkart A, Debski R, Musahl V, McMahon P, Woo SL. Biomechanical tests for type II SLAP lesions of the shoulder joint before and after arthroscopic repair [in German]. Orthopade. 2003;32(7):600-607.

26. Panossian VR, Mihata T, Tibone JE, Fitzpatrick MJ, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. Biomechanical analysis of isolated type II SLAP lesions and repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):529-534.

27. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Tibone JE, Fitzpatrick MJ, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical assessment of type II superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions associated with anterior shoulder capsular laxity as seen in throwers: a cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1604-1610.

28. Youm T, Tibone JE, ElAttrache NS, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. Simulated type II superior labral anterior posterior lesions do not alter the path of glenohumeral articulation: a cadaveric biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(4):767-774.

29. Youm T, ElAttrache NS, Tibone JE, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. The effect of the long head of the biceps on glenohumeral kinematics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):122-129.

30. McGarry MH, Nguyen ML, Quigley RJ, Hanypsiak B, Gupta R, Lee TQ. The effect of long and short head biceps loading on glenohumeral joint rotational range of motion and humeral head position [published online ahead of print September 26, 2014]. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.

31. Glousman R, Jobe F, Tibone J, Moynes D, Antonelli D, Perry J. Dynamic electromyographic analysis of the throwing shoulder with glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(2):220-226.

32. Gowan ID, Jobe FW, Tibone JE, Perry J, Moynes DR. A comparative electromyographic analysis of the shoulder during pitching. Professional versus amateur pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(6):586-590.

33. Rodosky MW, Harner CD, Fu FH. The role of the long head of the biceps muscle and superior glenoid labrum in anterior stability of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):121-130.

34. Boileau P, Parratte S, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Shia D, Bicknell R. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):929-936.

35. Gupta AK, Chalmers PN, Klosterman EL, et al. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for bicipital tendonitis with SLAP tear. Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e48-e53.

36. Ek ET, Shi LL, Tompson JD, Freehill MT, Warner JJ. Surgical treatment of isolated type II superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions: repair versus biceps tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1059-1065.

37. Alpert JM, Wuerz TH, O’Donnell TF, Carroll KM, Brucker NN, Gill TJ. The effect of age on the outcomes of arthroscopic repair of type II superior labral anterior and posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2299-2303.

38. Provencher MT, McCormick F, Dewing C, McIntire S, Solomon D. A prospective analysis of 179 type 2 superior labrum anterior and posterior repairs: outcomes and factors associated with success and failure. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):880-886.

39. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Burkhart SS. Long-term outcome after arthroscopic repair of type II SLAP lesions: results according to age and workers’ compensation status. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):451-457.

40. Burns JP, Bahk M, Snyder SJ. Superior labral tears: repair versus biceps tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2 suppl):S2-S8.

41. McCormick F, Nwachukwu BU, Solomon D, et al. The efficacy of biceps tenodesis in the treatment of failed superior labral anterior posterior repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):820-825.

42. Katz LM, Hsu S, Miller SL, et al. Poor outcomes after SLAP repair: descriptive analysis and prognosis. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):849-855.

43. Park S, Glousman RE. Outcomes of revision arthroscopic type II superior labral anterior posterior repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1290-1294.

44. Gupta AK, Bruce B, Klosterman EL, McCormick F, Harris J, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP repair. Orthopedics. 2013;36(6):e723-e728.

45. Neuman BJ, Boisvert CB, Reiter B, Lawson K, Ciccotti MG, Cohen SB. Results of arthroscopic repair of type II superior labral anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes: assessment of return to preinjury playing level and satisfaction. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1883-1888.

46. Fedoriw WW, Ramkumar P, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM. Return to play after treatment of superior labral tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1155-1160.

47. Park JY, Chung SW, Jeon SH, Lee JG, Oh KS. Clinical and radiological outcomes of type 2 superior labral anterior posterior repairs in elite overhead athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(6):1372-1379.

48. Schöffl V, Popp D, Dickschass J, Küpper T. Superior labral anterior-posterior lesions in rock climbers—primary double tenodesis? Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(3):261-263.

49. Chalmers PN, Trombley R, Cip J, et al. Postoperative restoration of upper extremity motion and neuromuscular control during the overhand pitch: evaluation of tenodesis and repair for superior labral anterior-posterior tears. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12):2825-2836.

50. Funk L, Snow M. SLAP tears of the glenoid labrum in contact athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(1):1-4.

51. Enad JG, Gaines RJ, White SM, Kurtz CA. Arthroscopic superior labrum anterior-posterior repair in military patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(3):300-305.

Injuries of the superior labrum–biceps complex (SLBC) have been recognized as a cause of shoulder pain since they were first described by Andrews and colleagues1 in 1985. Superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears are relatively uncommon injuries of the shoulder, and their true incidence is difficult to establish. However, recently there has been a significant increase in the reported incidence and operative treatment of SLAP tears.2 SLAP tears can occur in isolation, but they are commonly seen in association with other shoulder lesions, including rotator cuff tear, Bankart lesion, glenohumeral arthritis, acromioclavicular joint pathology, and subacromial impingement.

Although SLAP tears are well described and classified,3-6 our understanding of symptomatic SLAP tears and of their contribution to glenohumeral instability is limited. Diagnosing a SLAP tear on the basis of history and physical examination is a clinical challenge. Pain is the most common presentation of SLAP tears, though localization and characterization of pain are variable and nonspecific.7 The mechanism of injury is helpful in acute presentation (traction injury; fall on outstretched, abducted arm), but an overhead athlete may present with no distinct mechanism other than chronic, repetitive use of the shoulder.8-11 Numerous provocative physical examination tests have been used to assist in the diagnosis of SLAP tear, yet there is no consensus regarding the ideal physical examination test, with high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy.12-14 Magnetic resonance arthrography, the gold standard imaging modality, is highly sensitive and specific (>95%) for diagnosing SLAP tears.

SLAP tear management is based on lesion type and severity, age, functional demands, and presence of coexisting intra-articular lesions. Management options include nonoperative treatment, débridement or repair of SLBC, biceps tenotomy, and biceps tenodesis.15-19

In this 5-point review, we present an evidence-based analysis of the role of the SLBC in glenohumeral stability and the role of biceps tenodesis in the management of SLAP tears.

1. Role of SLBC in stability of glenohumeral joint

The anatomy of the SLBC has been well described,20,21 and there is consensus that SLBC pathology can be a source of shoulder pain. The superior labrum is relatively more mobile than the rest of the glenoid labrum, and it provides attachment to the long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) and the superior glenohumeral and middle glenohumeral ligaments.

The functional role of the SLBC in glenohumeral stability and its contribution to the pathogenesis of shoulder instability are not clearly defined. Our understanding of SLBC function is largely derived from simulated cadaveric experiments of SLAP tears. Controlled laboratory studies with simulated type II SLAP tears in cadavers have shown significantly increased glenohumeral translation in the anterior-posterior and superior-inferior directions, suggesting a role of the superior labrum in maintaining glenohumeral stability.22-26 Interestingly, there is conflicting evidence regarding restoration of normal glenohumeral translation in cadaveric shoulders after repair of simulated SLAP lesions in the presence or absence of simulated anterior capsular laxity.22,25-27 However, it is important to understand the limitations of cadaveric experiments in order to appreciate and truly comprehend the results of these experiments. There are inconsistencies in the size of simulated type II SLAP lesions in different studies, which can affect the degree of glenohumeral translation and the results of repair.23-25,28 The amount of glenohumeral translation noticed after simulated SLAP tears in cadavers, though statistically significant, is small in amplitude, and its relevance may not translate to a clinically significant level. The impact of dynamic components of stability (eg, rotator cuff muscles), capsular stretch, and other in vivo variables that affect glenohumeral stability are unaccounted for during cadaveric experiments.

LHBT is a recognized cause of shoulder pain, but its contribution to shoulder stability is a point of continued debate. According to one school of thought, LHBT is a vestigial structure that can be sacrificed without any loss of stability. Another school of thought holds that LHBT is an important active stabilizer of the glenohumeral joint. Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that loading the LHBT decreases glenohumeral translation and rotational range of motion, especially in lower and mid ranges of abduction.23,29,30 Furthermore, LHBT contributes to anterior glenohumeral stability by resisting torsional forces in the abducted and externally rotated shoulder and reducing stress on the inferior glenohumeral ligaments.31-33 Strauss and colleagues22 recently found that simulated anterior and posterior type II SLAP lesions in cadaveric shoulders increased glenohumeral translation in all planes, and biceps tenodesis did not further worsen this abnormal glenohumeral translation. Furthermore, repair of posterior SLAP lesions along with biceps tenodesis restored abnormal glenohumeral translation with no significant difference from the baseline in any plane of motion. Again, the limitations of cadaveric studies should be considered when interpreting these results and applying them clinically.

2. Biceps tenodesis as primary treatment for SLAP tears

A growing body of evidence suggests that primary tenodesis of LHBT may be an effective alternative treatment to SLAP repairs in select patients.34-36 However, the evidence is weak, and high-quality studies comparing SLAP repair and primary biceps tenodesis are required in order to make a strong recommendation for one technique over another. Gupta and colleagues35 retrospectively analyzed 28 cases of concomitant SLAP tear and biceps tendonitis treated with primary open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There was significant improvement in patients’ functional outcome scores postoperatively [SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation), ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons shoulder index), SST (Simple Shoulder Test), VAS (visual analog scale), and SF-12 (Short Form-12)]. In addition, 80% of patients were satisfied with their outcome. Mean age was 43.7 years. Forty-two percent of patients had a worker’s compensation claim. Interestingly, 15 patients in this cohort had a type I SLAP tear. Boileau and colleagues34 prospectively followed 25 cases of type II SLAP tear treated with either SLAP repair (10 patients; mean age, 37 years) or primary arthroscopic biceps tenodesis (15 patients; mean age, 52 years). Compared with the SLAP repair group, the biceps tenodesis group had significantly higher rates of satisfaction and return to previous level of sports participation. However, group assignments were nonrandomized, and the decision to treat a patient with SLAP repair versus biceps tenodesis was made by the senior surgeon purely on the basis of age (SLAP repair for patients under 30 years). Ek and colleagues36 retrospectively compared the cases of 10 patients who underwent SLAP repair (mean age, 32 years) and 15 who underwent biceps tenodesis (mean age, 47 years) for type II SLAP tear. There was no significant difference between the groups with respect to outcome scores, return to play or preinjury activity level, or complications.

There continues to be significant debate as to which patient will benefit from primary SLAP repair versus biceps tenodesis. Multiple factors are involved: age, presence of associated shoulder pathology, occupation, preinjury activity level, and worker’s compensation status. Age has convincingly been shown to affect the outcomes of treatment of type II SLAP tears.34,35,37-40 There is consensus that patients over age 40 years will benefit from primary biceps tenodesis for SLAP tears. However, the evidence for this recommendation is weak.

3. Biceps tenodesis and failed SLAP repair

The definition of a failed SLAP repair is not well documented in the literature, but dissatisfaction after SLAP repair can result from continued shoulder pain, poor shoulder function, or inability to return to preinjury functional level.15,41 The etiologic determination and treatment of a failed SLAP repair are challenging, and outcomes of revision SLAP repair are not very promising.42,43 Biceps tenodesis has been proposed as an alternative treatment to revision SLAP repair for failed SLAP repair. McCormick and colleagues41 prospectively evaluated 42 patients (mean age, 39.2 years; minimum follow-up, 2 years) with failed type II SLAP repairs that were treated with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There was significant improvement in ASES, SANE, and Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI) outcome scores and in postoperative shoulder range of motion at a mean follow-up of 3.6 years. One patient had transient musculocutaneous neurapraxia after surgery. In a retrospective cohort study, Gupta and colleagues44 found significant improvement in ASES, SANE, SST, SF-12, and VAS outcome scores in 11 patients who underwent open subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed arthroscopic SLAP repair (mean age at surgery, 40 years; mean follow-up, 26 months). Three of the 11 patients had worker’s compensation claims, and there were no complications and no revision surgeries required after biceps tenodesis. Werner and colleagues16 retrospectively evaluated 17 patients who underwent biceps tenodesis for failed SLAP repair (mean age, 39 years; minimum follow-up, 2 years). Twenty-nine percent of patients had worker’s compensation claims. Compared with the contralateral shoulder, the treated shoulder had better postoperative ASES, SANE, SST, and Veteran RAND 36-item health survey outcome scores; range of motion was near normal.

There are no high-quality studies comparing revision SLAP repair and biceps tenodesis in the management of failed SLAP repair.16,41-44 Case series studies have found improved outcomes and pain relief after biceps tenodesis for failed SLAP repair, but the quality of evidence has been poor (level IV evidence).16,41-44 The senior author recommends treating failed SLAP repairs with biceps tenodesis.

4. Biceps tenodesis as treatment option for SLAP tear in overhead throwing athletes

Biceps tenodesis is a potential alternative treatment to SLAP repair in overhead throwing athletes. Although outcome scores and satisfaction rates after SLAP repair are high in overhead athletes, the rates of return to sport are relatively low, especially in baseball players.38,45-47 In a level III cohort study, Boileau and colleagues34 found that 13 (87%) of 15 patients with type II SLAP tears, including 8 overhead athletes, had returned to their previous level of activity by a mean of 30 months after biceps tenodesis. In contrast, only 2 of 10 patients returned to their previous level of activity after SLAP repair. Interestingly, 3 patients who underwent biceps tenodesis for failed SLAP repair returned to overhead sports. Schöffl and colleagues48 reported on the outcomes of biceps tenodesis for SLAP lesions in 6 high-level rock climbers. By a mean follow-up of 6 months, all 6 patients had returned to their previous level of climbing. Their satisfaction rate was 96.8%. Gupta and colleagues35 reported on a cohort of 28 patients who underwent biceps tenodesis for SLAP tears and concomitant biceps tendonitis. Of the 8 athletes in the group, 5 were able to return to their previous level of play, and 1 was able to return to a lower level of sporting activity. There was significant improvement from preoperative to postoperative scores on ASES, SST, SANE, VAS, SF-12 overall, and SF-12 components.

Chalmers and colleagues49 recently described motion analyses with simultaneous surface electromyographic measurements in 18 baseball pitchers. Of these 18 players, 7 were uninjured (controls), 6 were pitching after SLAP repair, and 5 were pitching after subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There were no significant differences between controls and postoperative patients with respect to pitching kinematics. Interestingly, compared with the controls and the patients who underwent open biceps tenodesis, the patients who underwent SLAP repair had altered patterns of thoracic rotation during pitching. However, the clinical significance of this finding and the impact of this finding on pitching efficacy are not currently known.

Biceps tenodesis as a primary procedure for type II SLAP lesion in an overhead athlete is a concept in evolution. Increasing evidence suggests a role for primary biceps tenodesis in an overhead athlete with type II SLAP lesion and concomitant biceps pathology. However, this evidence is of poor quality, and the strength of the recommendation is weak. Still to be determined is whether return to preinjury performance level is better with primary biceps tenodesis or with SLAP repair in overhead athletes with type II SLAP lesion. As per the senior author’s treatment algorithm, we prefer SLAP repair for overhead athletes with type II SLAP tears and reserve biceps tenodesis for cases involving significant biceps pathology and/or clinical symptoms involving the bicipital groove consistent with extra-articular biceps pain.

5. Biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP tear in contact athletes and occupations demanding heavy labor (blue-collar jobs)

SLAP tears are less common in contact athletes, and there is general agreement that SLAP repair outcomes are better in contact athletes than in overhead athletes. In a retrospective review of 18 rugby players with SLAP tears, Funk and Snow50 reported excellent results and quicker return to sport after SLAP repair. Patients with isolated SLAP tears had the earliest return to play. Enad and colleagues51 reported SLAP repair outcomes in an active military population. SLAP tears are more common in the military versus the general population because of the unique physical demands placed on military personnel. The authors retrospectively reviewed 27 cases of type II SLAP tears treated with SLAP repair and suture anchors. Outcomes were measured at a mean of 30.5 months after surgery. Twenty-four (89%) of the 27 patients had good to excellent results, and 94% had returned to active duty by a mean of 4.4 months after SLAP repair.

Given the poor-quality evidence in the literature, we believe that biceps tenodesis should be reserved for revision surgery in contact athletes. There is insufficient evidence to recommend biceps tenodesis as primary treatment for type II SLAP tears in contact athletes. SLAP repair should be performed for primary SLAP lesions in contact athletes and for patients in physically demanding professions (eg, military, laborer, weightlifter).

Conclusion

SLAP tears can result in persistent shoulder pain and dysfunction. SLAP tear management depends on lesion type and severity, age, and functional demands. SLAP repair is the treatment of choice for type II SLAP lesions in young, active patients. Biceps tenodesis is a preferred alternative to SLAP repair in failed SLAP repair and in type II SLAP patients who are older than 40 years and who are less active and have a worker’s compensation claim. These recommendations are based on poor-quality evidence. There is an unmet need for randomized clinical studies comparing SLAP repair with biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP tears in different patient populations so as to optimize the current decision-making algorithm for SLAP tears.

Injuries of the superior labrum–biceps complex (SLBC) have been recognized as a cause of shoulder pain since they were first described by Andrews and colleagues1 in 1985. Superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears are relatively uncommon injuries of the shoulder, and their true incidence is difficult to establish. However, recently there has been a significant increase in the reported incidence and operative treatment of SLAP tears.2 SLAP tears can occur in isolation, but they are commonly seen in association with other shoulder lesions, including rotator cuff tear, Bankart lesion, glenohumeral arthritis, acromioclavicular joint pathology, and subacromial impingement.

Although SLAP tears are well described and classified,3-6 our understanding of symptomatic SLAP tears and of their contribution to glenohumeral instability is limited. Diagnosing a SLAP tear on the basis of history and physical examination is a clinical challenge. Pain is the most common presentation of SLAP tears, though localization and characterization of pain are variable and nonspecific.7 The mechanism of injury is helpful in acute presentation (traction injury; fall on outstretched, abducted arm), but an overhead athlete may present with no distinct mechanism other than chronic, repetitive use of the shoulder.8-11 Numerous provocative physical examination tests have been used to assist in the diagnosis of SLAP tear, yet there is no consensus regarding the ideal physical examination test, with high sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy.12-14 Magnetic resonance arthrography, the gold standard imaging modality, is highly sensitive and specific (>95%) for diagnosing SLAP tears.

SLAP tear management is based on lesion type and severity, age, functional demands, and presence of coexisting intra-articular lesions. Management options include nonoperative treatment, débridement or repair of SLBC, biceps tenotomy, and biceps tenodesis.15-19

In this 5-point review, we present an evidence-based analysis of the role of the SLBC in glenohumeral stability and the role of biceps tenodesis in the management of SLAP tears.

1. Role of SLBC in stability of glenohumeral joint

The anatomy of the SLBC has been well described,20,21 and there is consensus that SLBC pathology can be a source of shoulder pain. The superior labrum is relatively more mobile than the rest of the glenoid labrum, and it provides attachment to the long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) and the superior glenohumeral and middle glenohumeral ligaments.

The functional role of the SLBC in glenohumeral stability and its contribution to the pathogenesis of shoulder instability are not clearly defined. Our understanding of SLBC function is largely derived from simulated cadaveric experiments of SLAP tears. Controlled laboratory studies with simulated type II SLAP tears in cadavers have shown significantly increased glenohumeral translation in the anterior-posterior and superior-inferior directions, suggesting a role of the superior labrum in maintaining glenohumeral stability.22-26 Interestingly, there is conflicting evidence regarding restoration of normal glenohumeral translation in cadaveric shoulders after repair of simulated SLAP lesions in the presence or absence of simulated anterior capsular laxity.22,25-27 However, it is important to understand the limitations of cadaveric experiments in order to appreciate and truly comprehend the results of these experiments. There are inconsistencies in the size of simulated type II SLAP lesions in different studies, which can affect the degree of glenohumeral translation and the results of repair.23-25,28 The amount of glenohumeral translation noticed after simulated SLAP tears in cadavers, though statistically significant, is small in amplitude, and its relevance may not translate to a clinically significant level. The impact of dynamic components of stability (eg, rotator cuff muscles), capsular stretch, and other in vivo variables that affect glenohumeral stability are unaccounted for during cadaveric experiments.

LHBT is a recognized cause of shoulder pain, but its contribution to shoulder stability is a point of continued debate. According to one school of thought, LHBT is a vestigial structure that can be sacrificed without any loss of stability. Another school of thought holds that LHBT is an important active stabilizer of the glenohumeral joint. Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that loading the LHBT decreases glenohumeral translation and rotational range of motion, especially in lower and mid ranges of abduction.23,29,30 Furthermore, LHBT contributes to anterior glenohumeral stability by resisting torsional forces in the abducted and externally rotated shoulder and reducing stress on the inferior glenohumeral ligaments.31-33 Strauss and colleagues22 recently found that simulated anterior and posterior type II SLAP lesions in cadaveric shoulders increased glenohumeral translation in all planes, and biceps tenodesis did not further worsen this abnormal glenohumeral translation. Furthermore, repair of posterior SLAP lesions along with biceps tenodesis restored abnormal glenohumeral translation with no significant difference from the baseline in any plane of motion. Again, the limitations of cadaveric studies should be considered when interpreting these results and applying them clinically.

2. Biceps tenodesis as primary treatment for SLAP tears

A growing body of evidence suggests that primary tenodesis of LHBT may be an effective alternative treatment to SLAP repairs in select patients.34-36 However, the evidence is weak, and high-quality studies comparing SLAP repair and primary biceps tenodesis are required in order to make a strong recommendation for one technique over another. Gupta and colleagues35 retrospectively analyzed 28 cases of concomitant SLAP tear and biceps tendonitis treated with primary open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There was significant improvement in patients’ functional outcome scores postoperatively [SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation), ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons shoulder index), SST (Simple Shoulder Test), VAS (visual analog scale), and SF-12 (Short Form-12)]. In addition, 80% of patients were satisfied with their outcome. Mean age was 43.7 years. Forty-two percent of patients had a worker’s compensation claim. Interestingly, 15 patients in this cohort had a type I SLAP tear. Boileau and colleagues34 prospectively followed 25 cases of type II SLAP tear treated with either SLAP repair (10 patients; mean age, 37 years) or primary arthroscopic biceps tenodesis (15 patients; mean age, 52 years). Compared with the SLAP repair group, the biceps tenodesis group had significantly higher rates of satisfaction and return to previous level of sports participation. However, group assignments were nonrandomized, and the decision to treat a patient with SLAP repair versus biceps tenodesis was made by the senior surgeon purely on the basis of age (SLAP repair for patients under 30 years). Ek and colleagues36 retrospectively compared the cases of 10 patients who underwent SLAP repair (mean age, 32 years) and 15 who underwent biceps tenodesis (mean age, 47 years) for type II SLAP tear. There was no significant difference between the groups with respect to outcome scores, return to play or preinjury activity level, or complications.

There continues to be significant debate as to which patient will benefit from primary SLAP repair versus biceps tenodesis. Multiple factors are involved: age, presence of associated shoulder pathology, occupation, preinjury activity level, and worker’s compensation status. Age has convincingly been shown to affect the outcomes of treatment of type II SLAP tears.34,35,37-40 There is consensus that patients over age 40 years will benefit from primary biceps tenodesis for SLAP tears. However, the evidence for this recommendation is weak.

3. Biceps tenodesis and failed SLAP repair

The definition of a failed SLAP repair is not well documented in the literature, but dissatisfaction after SLAP repair can result from continued shoulder pain, poor shoulder function, or inability to return to preinjury functional level.15,41 The etiologic determination and treatment of a failed SLAP repair are challenging, and outcomes of revision SLAP repair are not very promising.42,43 Biceps tenodesis has been proposed as an alternative treatment to revision SLAP repair for failed SLAP repair. McCormick and colleagues41 prospectively evaluated 42 patients (mean age, 39.2 years; minimum follow-up, 2 years) with failed type II SLAP repairs that were treated with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There was significant improvement in ASES, SANE, and Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI) outcome scores and in postoperative shoulder range of motion at a mean follow-up of 3.6 years. One patient had transient musculocutaneous neurapraxia after surgery. In a retrospective cohort study, Gupta and colleagues44 found significant improvement in ASES, SANE, SST, SF-12, and VAS outcome scores in 11 patients who underwent open subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed arthroscopic SLAP repair (mean age at surgery, 40 years; mean follow-up, 26 months). Three of the 11 patients had worker’s compensation claims, and there were no complications and no revision surgeries required after biceps tenodesis. Werner and colleagues16 retrospectively evaluated 17 patients who underwent biceps tenodesis for failed SLAP repair (mean age, 39 years; minimum follow-up, 2 years). Twenty-nine percent of patients had worker’s compensation claims. Compared with the contralateral shoulder, the treated shoulder had better postoperative ASES, SANE, SST, and Veteran RAND 36-item health survey outcome scores; range of motion was near normal.

There are no high-quality studies comparing revision SLAP repair and biceps tenodesis in the management of failed SLAP repair.16,41-44 Case series studies have found improved outcomes and pain relief after biceps tenodesis for failed SLAP repair, but the quality of evidence has been poor (level IV evidence).16,41-44 The senior author recommends treating failed SLAP repairs with biceps tenodesis.

4. Biceps tenodesis as treatment option for SLAP tear in overhead throwing athletes

Biceps tenodesis is a potential alternative treatment to SLAP repair in overhead throwing athletes. Although outcome scores and satisfaction rates after SLAP repair are high in overhead athletes, the rates of return to sport are relatively low, especially in baseball players.38,45-47 In a level III cohort study, Boileau and colleagues34 found that 13 (87%) of 15 patients with type II SLAP tears, including 8 overhead athletes, had returned to their previous level of activity by a mean of 30 months after biceps tenodesis. In contrast, only 2 of 10 patients returned to their previous level of activity after SLAP repair. Interestingly, 3 patients who underwent biceps tenodesis for failed SLAP repair returned to overhead sports. Schöffl and colleagues48 reported on the outcomes of biceps tenodesis for SLAP lesions in 6 high-level rock climbers. By a mean follow-up of 6 months, all 6 patients had returned to their previous level of climbing. Their satisfaction rate was 96.8%. Gupta and colleagues35 reported on a cohort of 28 patients who underwent biceps tenodesis for SLAP tears and concomitant biceps tendonitis. Of the 8 athletes in the group, 5 were able to return to their previous level of play, and 1 was able to return to a lower level of sporting activity. There was significant improvement from preoperative to postoperative scores on ASES, SST, SANE, VAS, SF-12 overall, and SF-12 components.

Chalmers and colleagues49 recently described motion analyses with simultaneous surface electromyographic measurements in 18 baseball pitchers. Of these 18 players, 7 were uninjured (controls), 6 were pitching after SLAP repair, and 5 were pitching after subpectoral biceps tenodesis. There were no significant differences between controls and postoperative patients with respect to pitching kinematics. Interestingly, compared with the controls and the patients who underwent open biceps tenodesis, the patients who underwent SLAP repair had altered patterns of thoracic rotation during pitching. However, the clinical significance of this finding and the impact of this finding on pitching efficacy are not currently known.

Biceps tenodesis as a primary procedure for type II SLAP lesion in an overhead athlete is a concept in evolution. Increasing evidence suggests a role for primary biceps tenodesis in an overhead athlete with type II SLAP lesion and concomitant biceps pathology. However, this evidence is of poor quality, and the strength of the recommendation is weak. Still to be determined is whether return to preinjury performance level is better with primary biceps tenodesis or with SLAP repair in overhead athletes with type II SLAP lesion. As per the senior author’s treatment algorithm, we prefer SLAP repair for overhead athletes with type II SLAP tears and reserve biceps tenodesis for cases involving significant biceps pathology and/or clinical symptoms involving the bicipital groove consistent with extra-articular biceps pain.

5. Biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP tear in contact athletes and occupations demanding heavy labor (blue-collar jobs)

SLAP tears are less common in contact athletes, and there is general agreement that SLAP repair outcomes are better in contact athletes than in overhead athletes. In a retrospective review of 18 rugby players with SLAP tears, Funk and Snow50 reported excellent results and quicker return to sport after SLAP repair. Patients with isolated SLAP tears had the earliest return to play. Enad and colleagues51 reported SLAP repair outcomes in an active military population. SLAP tears are more common in the military versus the general population because of the unique physical demands placed on military personnel. The authors retrospectively reviewed 27 cases of type II SLAP tears treated with SLAP repair and suture anchors. Outcomes were measured at a mean of 30.5 months after surgery. Twenty-four (89%) of the 27 patients had good to excellent results, and 94% had returned to active duty by a mean of 4.4 months after SLAP repair.

Given the poor-quality evidence in the literature, we believe that biceps tenodesis should be reserved for revision surgery in contact athletes. There is insufficient evidence to recommend biceps tenodesis as primary treatment for type II SLAP tears in contact athletes. SLAP repair should be performed for primary SLAP lesions in contact athletes and for patients in physically demanding professions (eg, military, laborer, weightlifter).

Conclusion

SLAP tears can result in persistent shoulder pain and dysfunction. SLAP tear management depends on lesion type and severity, age, and functional demands. SLAP repair is the treatment of choice for type II SLAP lesions in young, active patients. Biceps tenodesis is a preferred alternative to SLAP repair in failed SLAP repair and in type II SLAP patients who are older than 40 years and who are less active and have a worker’s compensation claim. These recommendations are based on poor-quality evidence. There is an unmet need for randomized clinical studies comparing SLAP repair with biceps tenodesis for type II SLAP tears in different patient populations so as to optimize the current decision-making algorithm for SLAP tears.

1. Andrews JR, Carson WG Jr, McLeod WD. Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(5):337-341.

2. Weber SC, Martin DF, Seiler JG 3rd, Harrast JJ. Superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: incidence rates, complications, and outcomes as reported by American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery. Part II candidates. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1538-1543.

3. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):274-279.

4. Morgan CD, Burkhart SS, Palmeri M, Gillespie M. Type II SLAP lesions: three subtypes and their relationships to superior instability and rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(6):553-565.

5. Powell SE, Nord KD, Ryu RKN. The diagnosis, classification, and treatment of SLAP lesions. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2012;20(1):46-56.

6. Maffet MW, Gartsman GM, Moseley B. Superior labrum-biceps tendon complex lesions of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(1):93-98.

7. Kim TK, Queale WS, Cosgarea AJ, McFarland EG. Clinical features of the different types of SLAP lesions: an analysis of one hundred and thirty-nine cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(1):66-71.

8. Abrams GD, Safran MR. Diagnosis and management of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(5):311-318.

9. Keener JD, Brophy RH. Superior labral tears of the shoulder: pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(10):627-637.

10. Abrams GD, Hussey KE, Harris JD, Cole BJ. Clinical results of combined meniscus and femoral osteochondral allograft transplantation: minimum 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(8):964-970.e1.

11. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):404-420.

12. Virk MS, Arciero RA. Superior labrum anterior to posterior tears and glenohumeral instability. Instr Course Lect. 2013;62:501-514.

13. Calvert E, Chambers GK, Regan W, Hawkins RH, Leith JM. Special physical examination tests for superior labrum anterior posterior shoulder tears are clinically limited and invalid: a diagnostic systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):558-563.

14. Jones GL, Galluch DB. Clinical assessment of superior glenoid labral lesions: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:45-51.

15. Werner BC, Brockmeier SF, Miller MD. Etiology, diagnosis, and management of failed SLAP repair. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(9):554-565.

16. Werner BC, Pehlivan HC, Hart JM, et al. Biceps tenodesis is a viable option for salvage of failed SLAP repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(8):e179-e184.

17. Erickson J, Lavery K, Monica J, Gatt C, Dhawan A. Surgical treatment of symptomatic superior labrum anterior-posterior tears in patients older than 40 years: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1274-1282.

18. Huri G, Hyun YS, Garbis NG, McFarland EG. Treatment of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions: a literature review. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48(3):290-297.

19. Li X, Lin TJ, Jager M, et al. Management of type II superior labrum anterior posterior lesions: a review of the literature. Orthop Rev. 2010;2(1):e6.

20. Cooper DE, Arnoczky SP, O’Brien SJ, Warren RF, DiCarlo E, Allen AA. Anatomy, histology, and vascularity of the glenoid labrum. An anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(1):46-52.

21. Vangsness CT, Jorgenson SS, Watson T, Johnson DL. The origin of the long head of the biceps from the scapula and glenoid labrum. An anatomical study of 100 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(6):951-954.

22. Strauss EJ, Salata MJ, Sershon RA, et al. Role of the superior labrum after biceps tenodesis in glenohumeral stability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):485-491.

23. Pagnani MJ, Deng XH, Warren RF, Torzilli PA, Altchek DW. Effect of lesions of the superior portion of the glenoid labrum on glenohumeral translation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):1003-1010.

24. McMahon PJ, Burkart A, Musahl V, Debski RE. Glenohumeral translations are increased after a type II superior labrum anterior-posterior lesion: a cadaveric study of severity of passive stabilizer injury. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(1):39-44.

25. Burkart A, Debski R, Musahl V, McMahon P, Woo SL. Biomechanical tests for type II SLAP lesions of the shoulder joint before and after arthroscopic repair [in German]. Orthopade. 2003;32(7):600-607.

26. Panossian VR, Mihata T, Tibone JE, Fitzpatrick MJ, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. Biomechanical analysis of isolated type II SLAP lesions and repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):529-534.

27. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Tibone JE, Fitzpatrick MJ, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical assessment of type II superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions associated with anterior shoulder capsular laxity as seen in throwers: a cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1604-1610.

28. Youm T, Tibone JE, ElAttrache NS, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. Simulated type II superior labral anterior posterior lesions do not alter the path of glenohumeral articulation: a cadaveric biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(4):767-774.

29. Youm T, ElAttrache NS, Tibone JE, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. The effect of the long head of the biceps on glenohumeral kinematics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):122-129.

30. McGarry MH, Nguyen ML, Quigley RJ, Hanypsiak B, Gupta R, Lee TQ. The effect of long and short head biceps loading on glenohumeral joint rotational range of motion and humeral head position [published online ahead of print September 26, 2014]. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.

31. Glousman R, Jobe F, Tibone J, Moynes D, Antonelli D, Perry J. Dynamic electromyographic analysis of the throwing shoulder with glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(2):220-226.

32. Gowan ID, Jobe FW, Tibone JE, Perry J, Moynes DR. A comparative electromyographic analysis of the shoulder during pitching. Professional versus amateur pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(6):586-590.

33. Rodosky MW, Harner CD, Fu FH. The role of the long head of the biceps muscle and superior glenoid labrum in anterior stability of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):121-130.

34. Boileau P, Parratte S, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Shia D, Bicknell R. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):929-936.

35. Gupta AK, Chalmers PN, Klosterman EL, et al. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for bicipital tendonitis with SLAP tear. Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e48-e53.

36. Ek ET, Shi LL, Tompson JD, Freehill MT, Warner JJ. Surgical treatment of isolated type II superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions: repair versus biceps tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1059-1065.

37. Alpert JM, Wuerz TH, O’Donnell TF, Carroll KM, Brucker NN, Gill TJ. The effect of age on the outcomes of arthroscopic repair of type II superior labral anterior and posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2299-2303.

38. Provencher MT, McCormick F, Dewing C, McIntire S, Solomon D. A prospective analysis of 179 type 2 superior labrum anterior and posterior repairs: outcomes and factors associated with success and failure. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):880-886.

39. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Burkhart SS. Long-term outcome after arthroscopic repair of type II SLAP lesions: results according to age and workers’ compensation status. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):451-457.

40. Burns JP, Bahk M, Snyder SJ. Superior labral tears: repair versus biceps tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2 suppl):S2-S8.

41. McCormick F, Nwachukwu BU, Solomon D, et al. The efficacy of biceps tenodesis in the treatment of failed superior labral anterior posterior repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):820-825.

42. Katz LM, Hsu S, Miller SL, et al. Poor outcomes after SLAP repair: descriptive analysis and prognosis. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):849-855.

43. Park S, Glousman RE. Outcomes of revision arthroscopic type II superior labral anterior posterior repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1290-1294.

44. Gupta AK, Bruce B, Klosterman EL, McCormick F, Harris J, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP repair. Orthopedics. 2013;36(6):e723-e728.

45. Neuman BJ, Boisvert CB, Reiter B, Lawson K, Ciccotti MG, Cohen SB. Results of arthroscopic repair of type II superior labral anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes: assessment of return to preinjury playing level and satisfaction. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1883-1888.

46. Fedoriw WW, Ramkumar P, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM. Return to play after treatment of superior labral tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1155-1160.

47. Park JY, Chung SW, Jeon SH, Lee JG, Oh KS. Clinical and radiological outcomes of type 2 superior labral anterior posterior repairs in elite overhead athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(6):1372-1379.

48. Schöffl V, Popp D, Dickschass J, Küpper T. Superior labral anterior-posterior lesions in rock climbers—primary double tenodesis? Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(3):261-263.

49. Chalmers PN, Trombley R, Cip J, et al. Postoperative restoration of upper extremity motion and neuromuscular control during the overhand pitch: evaluation of tenodesis and repair for superior labral anterior-posterior tears. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12):2825-2836.

50. Funk L, Snow M. SLAP tears of the glenoid labrum in contact athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(1):1-4.

51. Enad JG, Gaines RJ, White SM, Kurtz CA. Arthroscopic superior labrum anterior-posterior repair in military patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(3):300-305.

1. Andrews JR, Carson WG Jr, McLeod WD. Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13(5):337-341.

2. Weber SC, Martin DF, Seiler JG 3rd, Harrast JJ. Superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions of the shoulder: incidence rates, complications, and outcomes as reported by American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery. Part II candidates. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1538-1543.

3. Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Ferkel RD, Friedman MJ. SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1990;6(4):274-279.

4. Morgan CD, Burkhart SS, Palmeri M, Gillespie M. Type II SLAP lesions: three subtypes and their relationships to superior instability and rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(6):553-565.

5. Powell SE, Nord KD, Ryu RKN. The diagnosis, classification, and treatment of SLAP lesions. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2012;20(1):46-56.

6. Maffet MW, Gartsman GM, Moseley B. Superior labrum-biceps tendon complex lesions of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(1):93-98.

7. Kim TK, Queale WS, Cosgarea AJ, McFarland EG. Clinical features of the different types of SLAP lesions: an analysis of one hundred and thirty-nine cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(1):66-71.

8. Abrams GD, Safran MR. Diagnosis and management of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(5):311-318.

9. Keener JD, Brophy RH. Superior labral tears of the shoulder: pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(10):627-637.

10. Abrams GD, Hussey KE, Harris JD, Cole BJ. Clinical results of combined meniscus and femoral osteochondral allograft transplantation: minimum 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(8):964-970.e1.

11. Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):404-420.

12. Virk MS, Arciero RA. Superior labrum anterior to posterior tears and glenohumeral instability. Instr Course Lect. 2013;62:501-514.

13. Calvert E, Chambers GK, Regan W, Hawkins RH, Leith JM. Special physical examination tests for superior labrum anterior posterior shoulder tears are clinically limited and invalid: a diagnostic systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(5):558-563.

14. Jones GL, Galluch DB. Clinical assessment of superior glenoid labral lesions: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:45-51.

15. Werner BC, Brockmeier SF, Miller MD. Etiology, diagnosis, and management of failed SLAP repair. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(9):554-565.

16. Werner BC, Pehlivan HC, Hart JM, et al. Biceps tenodesis is a viable option for salvage of failed SLAP repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(8):e179-e184.

17. Erickson J, Lavery K, Monica J, Gatt C, Dhawan A. Surgical treatment of symptomatic superior labrum anterior-posterior tears in patients older than 40 years: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1274-1282.

18. Huri G, Hyun YS, Garbis NG, McFarland EG. Treatment of superior labrum anterior posterior lesions: a literature review. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48(3):290-297.

19. Li X, Lin TJ, Jager M, et al. Management of type II superior labrum anterior posterior lesions: a review of the literature. Orthop Rev. 2010;2(1):e6.

20. Cooper DE, Arnoczky SP, O’Brien SJ, Warren RF, DiCarlo E, Allen AA. Anatomy, histology, and vascularity of the glenoid labrum. An anatomical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(1):46-52.

21. Vangsness CT, Jorgenson SS, Watson T, Johnson DL. The origin of the long head of the biceps from the scapula and glenoid labrum. An anatomical study of 100 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(6):951-954.

22. Strauss EJ, Salata MJ, Sershon RA, et al. Role of the superior labrum after biceps tenodesis in glenohumeral stability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):485-491.

23. Pagnani MJ, Deng XH, Warren RF, Torzilli PA, Altchek DW. Effect of lesions of the superior portion of the glenoid labrum on glenohumeral translation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):1003-1010.

24. McMahon PJ, Burkart A, Musahl V, Debski RE. Glenohumeral translations are increased after a type II superior labrum anterior-posterior lesion: a cadaveric study of severity of passive stabilizer injury. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(1):39-44.

25. Burkart A, Debski R, Musahl V, McMahon P, Woo SL. Biomechanical tests for type II SLAP lesions of the shoulder joint before and after arthroscopic repair [in German]. Orthopade. 2003;32(7):600-607.

26. Panossian VR, Mihata T, Tibone JE, Fitzpatrick MJ, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. Biomechanical analysis of isolated type II SLAP lesions and repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(5):529-534.

27. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Tibone JE, Fitzpatrick MJ, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical assessment of type II superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions associated with anterior shoulder capsular laxity as seen in throwers: a cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1604-1610.

28. Youm T, Tibone JE, ElAttrache NS, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. Simulated type II superior labral anterior posterior lesions do not alter the path of glenohumeral articulation: a cadaveric biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(4):767-774.

29. Youm T, ElAttrache NS, Tibone JE, McGarry MH, Lee TQ. The effect of the long head of the biceps on glenohumeral kinematics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):122-129.

30. McGarry MH, Nguyen ML, Quigley RJ, Hanypsiak B, Gupta R, Lee TQ. The effect of long and short head biceps loading on glenohumeral joint rotational range of motion and humeral head position [published online ahead of print September 26, 2014]. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.

31. Glousman R, Jobe F, Tibone J, Moynes D, Antonelli D, Perry J. Dynamic electromyographic analysis of the throwing shoulder with glenohumeral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(2):220-226.

32. Gowan ID, Jobe FW, Tibone JE, Perry J, Moynes DR. A comparative electromyographic analysis of the shoulder during pitching. Professional versus amateur pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(6):586-590.

33. Rodosky MW, Harner CD, Fu FH. The role of the long head of the biceps muscle and superior glenoid labrum in anterior stability of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):121-130.

34. Boileau P, Parratte S, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Shia D, Bicknell R. Arthroscopic treatment of isolated type II SLAP lesions: biceps tenodesis as an alternative to reinsertion. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):929-936.

35. Gupta AK, Chalmers PN, Klosterman EL, et al. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for bicipital tendonitis with SLAP tear. Orthopedics. 2015;38(1):e48-e53.

36. Ek ET, Shi LL, Tompson JD, Freehill MT, Warner JJ. Surgical treatment of isolated type II superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions: repair versus biceps tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1059-1065.

37. Alpert JM, Wuerz TH, O’Donnell TF, Carroll KM, Brucker NN, Gill TJ. The effect of age on the outcomes of arthroscopic repair of type II superior labral anterior and posterior lesions. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2299-2303.

38. Provencher MT, McCormick F, Dewing C, McIntire S, Solomon D. A prospective analysis of 179 type 2 superior labrum anterior and posterior repairs: outcomes and factors associated with success and failure. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):880-886.

39. Denard PJ, Lädermann A, Burkhart SS. Long-term outcome after arthroscopic repair of type II SLAP lesions: results according to age and workers’ compensation status. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(4):451-457.

40. Burns JP, Bahk M, Snyder SJ. Superior labral tears: repair versus biceps tenodesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2 suppl):S2-S8.

41. McCormick F, Nwachukwu BU, Solomon D, et al. The efficacy of biceps tenodesis in the treatment of failed superior labral anterior posterior repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(4):820-825.

42. Katz LM, Hsu S, Miller SL, et al. Poor outcomes after SLAP repair: descriptive analysis and prognosis. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(8):849-855.

43. Park S, Glousman RE. Outcomes of revision arthroscopic type II superior labral anterior posterior repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(6):1290-1294.

44. Gupta AK, Bruce B, Klosterman EL, McCormick F, Harris J, Romeo AA. Subpectoral biceps tenodesis for failed type II SLAP repair. Orthopedics. 2013;36(6):e723-e728.

45. Neuman BJ, Boisvert CB, Reiter B, Lawson K, Ciccotti MG, Cohen SB. Results of arthroscopic repair of type II superior labral anterior posterior lesions in overhead athletes: assessment of return to preinjury playing level and satisfaction. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1883-1888.

46. Fedoriw WW, Ramkumar P, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM. Return to play after treatment of superior labral tears in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1155-1160.

47. Park JY, Chung SW, Jeon SH, Lee JG, Oh KS. Clinical and radiological outcomes of type 2 superior labral anterior posterior repairs in elite overhead athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(6):1372-1379.

48. Schöffl V, Popp D, Dickschass J, Küpper T. Superior labral anterior-posterior lesions in rock climbers—primary double tenodesis? Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(3):261-263.

49. Chalmers PN, Trombley R, Cip J, et al. Postoperative restoration of upper extremity motion and neuromuscular control during the overhand pitch: evaluation of tenodesis and repair for superior labral anterior-posterior tears. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12):2825-2836.

50. Funk L, Snow M. SLAP tears of the glenoid labrum in contact athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(1):1-4.

51. Enad JG, Gaines RJ, White SM, Kurtz CA. Arthroscopic superior labrum anterior-posterior repair in military patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(3):300-305.

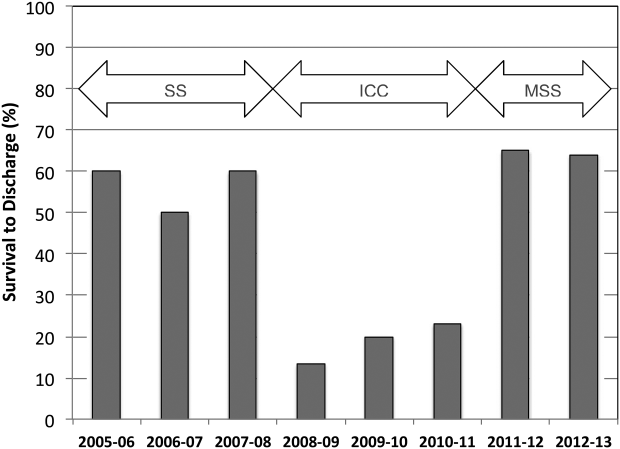

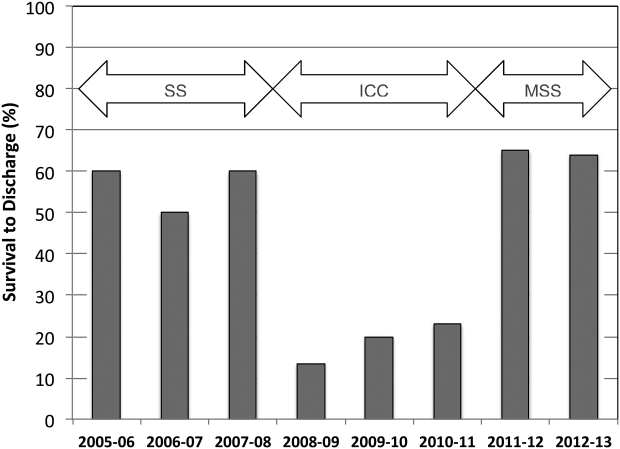

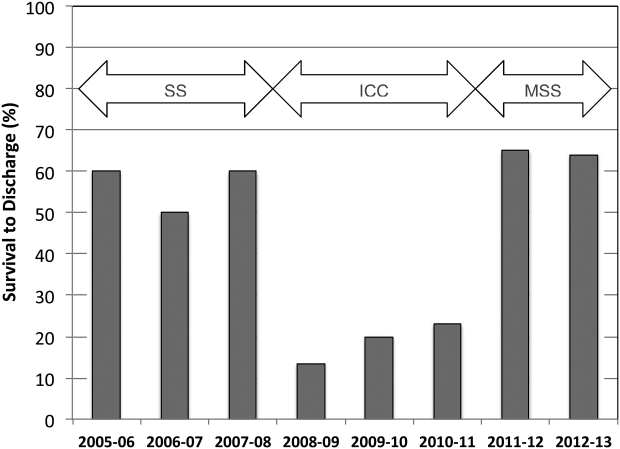

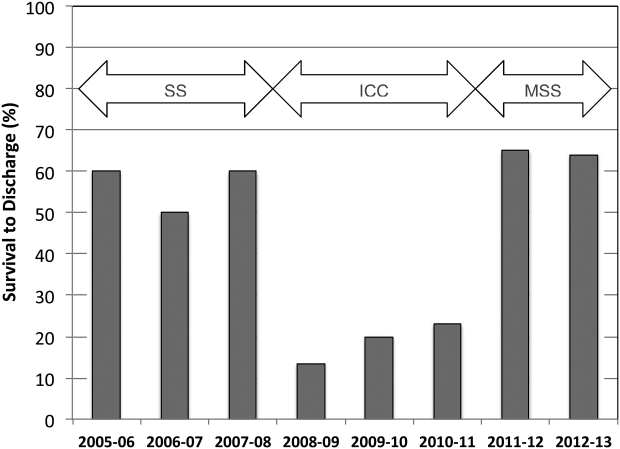

CPR Prior to Defibrillation for VF/VT CPA

Cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) is a major contributor to overall mortality in both the in‐ and out‐of‐hospital setting.[1, 2, 3] Despite advances in the field of resuscitation science, mortality from CPA remains high.[1, 4] Unlike the out‐of‐hospital environment, inpatient CPA is unique, as trained healthcare providers are the primary responders with a range of expertise available throughout the duration of arrest.

There are inherent opportunities of in‐hospital cardiac arrest that exist, such as the opportunity for near immediate arrest detection, rapid initiation of high‐quality chest compressions, and early defibrillation if indicated. Given the association between improved rates of successful defibrillation and high‐quality chest compressions, the 2005 American Heart Association (AHA) updates changed the recommended guideline ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia (VF/VT) defibrillation sequence from 3 stacked shocks to a single shock followed by 2 minutes of chest compressions between defibrillation attempts.[5, 6] However, the recommendations were directed primarily at cases of out‐of‐hospital VF/VT CPA, and it currently remains unclear as to whether this strategy offers any advantage to patients who suffer an in‐hospital VF/VT arrest.[7]

Despite the aforementioned findings regarding the benefit of high‐quality chest compressions, there is a paucity of evidence in the medical literature to support whether delivering a period of chest compressions before defibrillation attempt, including initial shock and shock sequence, translate to improved outcomes. With the exception of the statement recommending early defibrillation in case of in‐hospital arrest, there are no formal AHA consensus recommendations.[5, 8, 9] Here we document our experience using the approach of expedited stacked defibrillation shocks in persons experiencing monitored in‐hospital VF/VT arrest.

METHODS

Design

This was a retrospective study of observational data from our in‐hospital resuscitation database. Waiver of informed consent was granted by our institutional investigational review board.

Setting

This study was performed in the University of California San Diego Healthcare System, which includes 2 urban academic hospitals, with a combined total of approximately 500 beds. A designated team is activated in response to code blue requests and includes: code registered nurse (RN), code doctor of medicine (MD), airway MD, respiratory therapist, pharmacist, house nursing supervisor, primary RN, and unit charge RN. Crash carts with defibrillators (ZOLL R and E series; ZOLL Medical Corp., Chelmsford, MA) are located on each inpatient unit. Defibrillator features include real‐time cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) feedback, filtered electrocardiography (ECG), and continuous waveform capnography.