User login

Examining Interventions and Adverse Events After Nonfatal Opioid Overdoses in Veterans

The number of opioid-related overdose deaths in the United States is estimated to have increased 6-fold over the past 2 decades.1 In 2017, more than two-thirds of drug overdose deaths involved opioids, yielding a mortality rate of 14.9 per 100,000.2 Not only does the opioid epidemic currently pose a significant public health crisis characterized by high morbidity and mortality, but it is also projected to worsen in coming years. According to Chen and colleagues, opioid overdose deaths are estimated to increase by 147% from 2015 to 2025.3 That projects almost 82,000 US deaths annually and > 700,000 deaths in this period—even before accounting for surges in opioid overdoses and opioid-related mortality coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic.3,4

As health systems and communities globally struggle with unprecedented losses and stressors introduced by the pandemic, emerging data warrants escalating concerns with regard to increased vulnerability to relapse and overdose among those with mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs). In a recent report, the American Medical Association estimates that opioid-related deaths have increased in more than 40 states with the COVID-19 pandemic.4

Veterans are twice as likely to experience a fatal opioid overdose compared with their civilian counterparts.5 While several risk mitigation strategies have been employed in recent years to improve opioid prescribing and safety within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), veterans continue to overdose on opioids, both prescribed and obtained illicitly.6 Variables shown to be strongly associated with opioid overdose risk include presence of mental health disorders, SUDs, medical conditions involving impaired drug metabolism or excretion, respiratory disorders, higher doses of opioids, concomitant use of sedative medications, and history of overdose.6-8 Many veterans struggle with chronic pain and those prescribed high doses of opioids were more likely to have comorbid pain diagnoses, mental health disorders, and SUDs.9 Dashboards and predictive models, such as the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) and the Risk Index for Overdose or Serious Opioid-induced Respiratory Depression (RIOSORD), incorporate such factors to stratify overdose risk among veterans, in an effort to prioritize high-risk individuals for review and provision of care.6,10,11 Despite recent recognition that overdose prevention likely requires a holistic approach that addresses the biopsychosocial factors contributing to opioid-related morbidity and mortality, it is unclear whether veterans are receiving adequate and appropriate treatment for contributing conditions.

There are currently no existing studies that describe health service utilization (HSU), medication interventions, and rates of opioid-related adverse events (ORAEs) among veterans after survival of a nonfatal opioid overdose (NFO). Clinical characteristics of veterans treated for opioid overdose at a VA emergency department (ED) have previously been described by Clement and Stock.12 Despite improvements that have been made in VA opioid prescribing and safety, knowledge gaps remain with regard to best practices for opioid overdose prevention. The aim of this study was to characterize HSU and medication interventions in veterans following NFO, as well as the frequency of ORAEs after overdose. The findings of this study may aid in the identification of areas for targeted improvement in the prevention and reduction of opioid overdoses and adverse opioid-related sequelae.

Methods

This retrospective descriptive study was conducted at VA San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHCS) in California. Subjects included were veterans administered naloxone in the ED for suspected opioid overdose between July 1, 2013 and April 1, 2017. The study population was identified through data retrieved from automated drug dispensing systems, which was then confirmed through manual chart review of notes associated with the index ED visit. Inclusion criteria included documented increased respiration or responsiveness following naloxone administration. Subjects were excluded if they demonstrated lack of response to naloxone, overdosed secondary to inpatient administration of opioids, received palliative or hospice care during the study period, or were lost to follow-up.

Data were collected via retrospective chart review and included date of index ED visit, demographics, active prescriptions, urine drug screen (UDS) results, benzodiazepine (BZD) use corroborated by positive UDS or mention of BZD in index visit chart notes, whether overdose was determined to be a suicide attempt, and naloxone kit dispensing. Patient data was collected for 2 years following overdose, including: ORAEs; ED visits; hospitalizations; repeat overdoses; fatal overdose; whether subjects were still alive; follow-up visits for pain management, mental health, and addiction treatment services; and visits to the psychiatric emergency clinic. Clinical characteristics, such as mental health disorder diagnoses, SUDs, and relevant medical conditions also were collected. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and included only descriptive statistics.

Results

Ninety-three patients received naloxone in the VASDHCS ED. Thirty-five met inclusion criteria and were included in the primary analysis. All subjects received IV naloxone with a mean 0.8 mg IV boluses (range, 0.1-4.4 mg).

Most patients were male with a mean age of 59.8 years (Table 1). Almost all overdoses were nonintentional except for 3 suicide attempts that were reviewed by the Suicide Prevention Committee. Three patients had previously been treated for opioid overdose at the VA with a documented positive clinical response to naloxone administration.

At the time of overdose, 29 patients (82.9%) had an active opioid prescription. Of these, the majority were issued through the VA with a mean 117 mg morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD). Interestingly, only 24 of the 28 patients with a UDS collected at time of overdose tested positive for opioids, which may be attributable to the use of synthetic opioids, which are not reliably detected by traditional UDS. Concomitant BZD use was involved in 13 of the 35 index overdoses (37.1%), although only 6 patients (17.1%) had an active BZD prescription at time of overdose. Seven patients (20.0%) were prescribed medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder (OUD), with all 7 using methadone. According to VA records, only 1 patient had previously been dispensed a naloxone kit at any point prior to overdosing. Mental health and SUD diagnoses frequently co-occurred, with 20 patients (57.1%) having at least 1 mental health condition and at least 1 SUD.

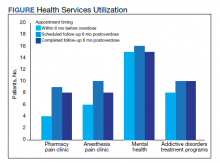

Rates of follow-up varied by clinician type in the 6 months after NFO (Figure). Of those with mental health disorders, 15 patients (45.5%) received mental health services before and after overdose, while 8 (40.0%) and 10 (50.0%) of those with SUDs received addiction treatment services before and after overdose, respectively. Seven patients presented to the psychiatric emergency clinic within 6 months prior to overdose and 5 patients within the 6 months following overdose.

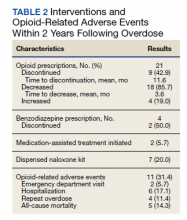

Of patients with VA opioid prescriptions, within 2 years of NFO, 9 (42.9%) had their opioids discontinued, and 18 (85.7%) had MEDD reductions ranging from 10 mg to 150 mg (12.5-71.4% reduction) with a mean of 63 mg. Two of the 4 patients with active BZD prescriptions at the time of the overdose event had their prescriptions continued. Seven patients (20.0%) were dispensed naloxone kits following overdose (Table 2).

Rates of ORAEs ranged from 0% to 17% with no documented overdose fatalities. Examples of AEs observed in this study included ED visits or hospitalizations involving opioid withdrawal, opioid-related personality changes, and opioid overdose. Five patients died during the study period, yielding an all-cause mortality rate of 14.3% with a mean time to death of 10.8 months. The causes of death were largely unknown except for 1 patient, whose death was reportedly investigated as an accidental medication overdose without additional information.

Repeat overdose verified by hospital records occurred in 4 patients (11.4%) within 2 years. Patients who experienced a subsequent overdose were prescribed higher doses of opioids with a mean MEDD among VA prescriptions of 130 mg vs 114 mg for those without repeat overdose. In this group, 3 patients (75.0%) also had concomitant BZD use, which was proportionally higher than the 10 patients (32.3%) without a subsequent overdose. Of note, 2 of the 4 patients with a repeat overdose had their opioid doses increased above the MEDD prescribed at the time of index overdose. None of the 4 subjects who experienced a repeat overdose were initiated on MAT within 2 years according to VA records.

Discussions

This retrospective study is representative of many veterans receiving VA care, despite the small sample size. Clinical characteristics observed in the study population were generally consistent with those published by Clement and Stock, including high rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidities.12 Subjects in both studies were prescribed comparable dosages of opioids; among those prescribed opioids but not BZDs through the VA, the mean MEDD was 117 mg in our study compared with 126 mg in the Clement and Stock study. Since implementation of the Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) in 2013, opioid prescribing practices have improved nationwide across VA facilities, including successful reduction in the numbers of patients prescribed high-dose opioids and concurrent BZDs.13

Despite the tools and resources available to clinicians, discontinuing opioid therapy remains a difficult process. Concerns related to mental health and/or substance-use related decompensations often exist in the setting of rapid dose reductions or abrupt discontinuation of opioids.6 Although less than half of patients in the present study with an active opioid prescription at time of index overdose had their opioids discontinued within 2 years, it is reassuring to note the much higher rate of those with subsequent decreases in their prescribed doses, as well as the 50% reduction in BZD coprescribing. Ultimately, these findings remain consistent with the VA goals of mitigating harm, improving opioid prescribing, and ensuring the safe use of opioid medications when clinically appropriate.

Moreover, recent evidence suggests that interventions focused solely on opioid prescribing practices are becoming increasingly limited in their impact on reducing opioid-related deaths and will likely be insufficient for addressing the opioid epidemic as it continues to evolve. According to Chen and colleagues, opioid overdose deaths are projected to increase over the next several years, while further reduction in the incidence of prescription opioid misuse is estimated to decrease overdose deaths by only 3% to 5.3%. In the context of recent surges in synthetic opioid use, it is projected that 80% of overdose deaths between 2016 and 2025 will be attributable to illicit opioids.3 Such predictions underscore the urgent need to adopt alternative approaches to risk-reducing measures and policy change.

The increased risk of mortality associated with opioid misuse and overdose is well established in the current literature. However, less is known regarding the rate of ORAEs after survival of an NFO. Olfson and colleagues sought to address this knowledge gap by characterizing mortality risks in 76,325 US adults within 1 year following NFO.14 Among their studied population, all-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 778.3 per 10,000 person-years, which was 24 times greater than that of the general population. This emphasizes the need for the optimization of mental health services, addiction treatment, and medical care for these individuals at higher risk.

Limitations

Certain factors and limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Given that the study included only veterans, factors such as the demographic and clinical characteristics more commonly observed among these patients should be taken into account and may in turn limit the generalizability of these findings to nonveteran populations. Another major limitation is the small sample size; the study period and by extension, the number of patients able to be included in the present study were restricted by the availability of retrievable data from automated drug dispensing systems. Patients without documented response to naloxone were excluded from the study due to low clinical suspicion for opioid overdose, although the possibility that the dose administered was too low to produce a robust clinical response cannot be definitively ruled out. The lack of reliable methods to capture events and overdoses treated outside of the VA may have resulted in underestimations of the true occurrence of ORAEs following NFO. Information regarding naloxone administration outside VA facilities, such as in transport to the hospital, self-reported, or bystander administration, was similarly limited by lack of reliable methods for retrieving such data and absence of documentation in VA records. Although all interventions and outcomes reported in the present study occurred within 2 years following NFO, further conclusions pertaining to the relative timing of specific interventions and ORAEs cannot be made. Lastly, this study did not investigate the direct impact of opioid risk mitigation initiatives implemented by the VA in the years coinciding with the study period.

Future Directions

Despite these limitations, an important strength of this study is its ability to identify potential areas for targeted improvement and to guide further efforts relating to the prevention of opioid overdose and opioid-related mortality among veterans. Identification of individuals at high risk for opioid overdose and misuse is an imperative first step that allows for the implementation of downstream risk-mitigating interventions. Within the VA, several tools have been developed in recent years to provide clinicians with additional resources and support in this regard.6,15

No more than half of those diagnosed with mental health disorders and SUDs in the present study received outpatient follow-up care for these conditions within 6 months following NFO, which may suggest high rates of inadequate treatment. Given the strong association between mental health disorders, SUDs, and increased risk of overdose, increasing engagement with mental health and addiction treatment services may be paramount to preventing subsequent ORAEs, including repeat overdose.6-9,11

Naloxone kit dispensing represents another area for targeted improvement. Interventions may include clinician education and systematic changes, such as implementing protocols that boost the likelihood of high-risk individuals being provided with naloxone at the earliest opportunity. Bystander-administered naloxone programs can also be considered for increasing naloxone access and reducing opioid-related mortality.16

Finally, despite evidence supporting the benefit of MAT in OUD treatment and reducing all-cause and opioid-related mortality after NFO, the low rates of MAT observed in this study are consistent with previous reports that these medications remain underutilized.17 Screening for OUD, in conjunction with increasing access to and utilization of OUD treatment modalities, is an established and integral component of overdose prevention efforts. For VA clinicians, the Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI) dashboard can be used to identify patients diagnosed with OUD who are not yet on MAT.18 Initiatives to expand MAT access through the ED have the potential to provide life-saving interventions and bridge care in the interim until patients are able to become established with a long-term health care practitioner.19

Conclusions

This is the first study to describe HSU, medication interventions, and ORAEs among veterans who survive NFO. Studies have shown that veterans with a history of NFO are at increased risk of subsequent AEs and premature death.6,7,10,14 As such, NFOs represent crucial opportunities to identify high-risk individuals and ensure provision of adequate care. Recent data supports the development of a holistic, multimodal approach focused on adequate treatment of conditions that contribute to opioid-related risks, including mental health disorders, SUDs, pain diagnoses, and medical comorbidities.3,14 Interventions designed to improve access, engagement, and retention in such care therefore play a pivotal role in overdose prevention and reducing mortality.

Although existing risk mitigation initiatives have improved opioid prescribing and safety within the VA, the findings of this study suggest that there remains room for improvement, and the need for well-coordinated efforts to reduce risks associated with both prescribed and illicit opioid use cannot be overstated. Rates of overdose deaths not only remain high but are projected to continue increasing in coming years, despite advances in clinical practice aimed at reducing harms associated with opioid use. The present findings aim to help identify processes with the potential to reduce rates of overdose, death, and adverse sequelae in high-risk populations. However, future studies are warranted to expand on these findings and contribute to ongoing efforts in reducing opioid-related harms and overdose deaths. This study may provide critical insight to inform further investigations to guide such interventions and highlight tools that health care facilities even outside the VA can consider implementing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jonathan Lacro, PharmD, BCPP, for his guidance with this important clinical topic and navigating IRB submissions.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data overview: the drug overdose epidemic: behind the numbers. Updated March 25, 2021. Accessed February 9, 2022. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/index.html

2. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427. Published 2018 Jan 4. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1 3. Chen Q, Larochelle MR, Weaver DT, et al. Prevention of prescription opioid misuse and projected overdose deaths in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187621. Published 2019 Feb 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7621

4. American Medical Association. Issue brief: nation’s drug-related overdose and death epidemic continues to worsen. Updated November 12, 2021. Accessed February 11, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/issue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf

5. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Galea S, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Accidental poisoning mortality among patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health System. Med Care. 2011;49(4):393-396. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202aa27

6. Lewis ET, Trafton J, Oliva E. Data-based case reviews of patients with opioid related risk factors as a tool to prevent overdose and suicide. Accessed February 9, 2022. www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/2488-notes.pdf

7. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Risk factors for serious prescription opioid-related toxicity or overdose among Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1911-1929. doi:10.1111/pme.12480

8. Webster LR. Risk Factors for Opioid-Use Disorder and Overdose. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1741-1748. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002496

9. Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Carr TP, Deyo RA, Dobscha SK. Clinical characteristics of veterans prescribed high doses of opioid medications for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2010;151(3):625-632. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.002

10. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

11. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Development of a risk index for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose in Veterans’ Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):1566-1579. doi:10.1111/pme.12777

12. Clement C, Stock C. Who Overdoses at a VA Emergency Department? Fed Pract. 2016;33(11):14-20.

13. Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the Opioid Safety Initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158(5):833-839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837

14. Olfson M, Crystal S, Wall M, Wang S, Liu SM, Blanco C. Causes of death after nonfatal opioid overdose [published correction appears in JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Aug 1;75(8):867]. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):820-827. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1471

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA pain management – opioid safety – clinical tools. Updated November 14, 2019. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/Opioid_Safety/Clinical_Tools.asp

16. Doe-Simkins M, Walley AY, Epstein A, Moyer P. Saved by the nose: bystander-administered intranasal naloxone hydrochloride for opioid overdose. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):788-791. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.146647

17. Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):137-145. doi:10.7326/M17-3107

18. Wiechers I. Program focuses on safe psychiatric medication. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://blogs.va.gov/VAntage/27099/program-focuses-safe-psychiatric-medication/

19. Newman S; California Health Care Foundation. How to pay for it – MAT in the emergency department: FAQ. Published March 2019. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/HowToPayForMATinED.pdf

The number of opioid-related overdose deaths in the United States is estimated to have increased 6-fold over the past 2 decades.1 In 2017, more than two-thirds of drug overdose deaths involved opioids, yielding a mortality rate of 14.9 per 100,000.2 Not only does the opioid epidemic currently pose a significant public health crisis characterized by high morbidity and mortality, but it is also projected to worsen in coming years. According to Chen and colleagues, opioid overdose deaths are estimated to increase by 147% from 2015 to 2025.3 That projects almost 82,000 US deaths annually and > 700,000 deaths in this period—even before accounting for surges in opioid overdoses and opioid-related mortality coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic.3,4

As health systems and communities globally struggle with unprecedented losses and stressors introduced by the pandemic, emerging data warrants escalating concerns with regard to increased vulnerability to relapse and overdose among those with mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs). In a recent report, the American Medical Association estimates that opioid-related deaths have increased in more than 40 states with the COVID-19 pandemic.4

Veterans are twice as likely to experience a fatal opioid overdose compared with their civilian counterparts.5 While several risk mitigation strategies have been employed in recent years to improve opioid prescribing and safety within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), veterans continue to overdose on opioids, both prescribed and obtained illicitly.6 Variables shown to be strongly associated with opioid overdose risk include presence of mental health disorders, SUDs, medical conditions involving impaired drug metabolism or excretion, respiratory disorders, higher doses of opioids, concomitant use of sedative medications, and history of overdose.6-8 Many veterans struggle with chronic pain and those prescribed high doses of opioids were more likely to have comorbid pain diagnoses, mental health disorders, and SUDs.9 Dashboards and predictive models, such as the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) and the Risk Index for Overdose or Serious Opioid-induced Respiratory Depression (RIOSORD), incorporate such factors to stratify overdose risk among veterans, in an effort to prioritize high-risk individuals for review and provision of care.6,10,11 Despite recent recognition that overdose prevention likely requires a holistic approach that addresses the biopsychosocial factors contributing to opioid-related morbidity and mortality, it is unclear whether veterans are receiving adequate and appropriate treatment for contributing conditions.

There are currently no existing studies that describe health service utilization (HSU), medication interventions, and rates of opioid-related adverse events (ORAEs) among veterans after survival of a nonfatal opioid overdose (NFO). Clinical characteristics of veterans treated for opioid overdose at a VA emergency department (ED) have previously been described by Clement and Stock.12 Despite improvements that have been made in VA opioid prescribing and safety, knowledge gaps remain with regard to best practices for opioid overdose prevention. The aim of this study was to characterize HSU and medication interventions in veterans following NFO, as well as the frequency of ORAEs after overdose. The findings of this study may aid in the identification of areas for targeted improvement in the prevention and reduction of opioid overdoses and adverse opioid-related sequelae.

Methods

This retrospective descriptive study was conducted at VA San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHCS) in California. Subjects included were veterans administered naloxone in the ED for suspected opioid overdose between July 1, 2013 and April 1, 2017. The study population was identified through data retrieved from automated drug dispensing systems, which was then confirmed through manual chart review of notes associated with the index ED visit. Inclusion criteria included documented increased respiration or responsiveness following naloxone administration. Subjects were excluded if they demonstrated lack of response to naloxone, overdosed secondary to inpatient administration of opioids, received palliative or hospice care during the study period, or were lost to follow-up.

Data were collected via retrospective chart review and included date of index ED visit, demographics, active prescriptions, urine drug screen (UDS) results, benzodiazepine (BZD) use corroborated by positive UDS or mention of BZD in index visit chart notes, whether overdose was determined to be a suicide attempt, and naloxone kit dispensing. Patient data was collected for 2 years following overdose, including: ORAEs; ED visits; hospitalizations; repeat overdoses; fatal overdose; whether subjects were still alive; follow-up visits for pain management, mental health, and addiction treatment services; and visits to the psychiatric emergency clinic. Clinical characteristics, such as mental health disorder diagnoses, SUDs, and relevant medical conditions also were collected. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and included only descriptive statistics.

Results

Ninety-three patients received naloxone in the VASDHCS ED. Thirty-five met inclusion criteria and were included in the primary analysis. All subjects received IV naloxone with a mean 0.8 mg IV boluses (range, 0.1-4.4 mg).

Most patients were male with a mean age of 59.8 years (Table 1). Almost all overdoses were nonintentional except for 3 suicide attempts that were reviewed by the Suicide Prevention Committee. Three patients had previously been treated for opioid overdose at the VA with a documented positive clinical response to naloxone administration.

At the time of overdose, 29 patients (82.9%) had an active opioid prescription. Of these, the majority were issued through the VA with a mean 117 mg morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD). Interestingly, only 24 of the 28 patients with a UDS collected at time of overdose tested positive for opioids, which may be attributable to the use of synthetic opioids, which are not reliably detected by traditional UDS. Concomitant BZD use was involved in 13 of the 35 index overdoses (37.1%), although only 6 patients (17.1%) had an active BZD prescription at time of overdose. Seven patients (20.0%) were prescribed medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder (OUD), with all 7 using methadone. According to VA records, only 1 patient had previously been dispensed a naloxone kit at any point prior to overdosing. Mental health and SUD diagnoses frequently co-occurred, with 20 patients (57.1%) having at least 1 mental health condition and at least 1 SUD.

Rates of follow-up varied by clinician type in the 6 months after NFO (Figure). Of those with mental health disorders, 15 patients (45.5%) received mental health services before and after overdose, while 8 (40.0%) and 10 (50.0%) of those with SUDs received addiction treatment services before and after overdose, respectively. Seven patients presented to the psychiatric emergency clinic within 6 months prior to overdose and 5 patients within the 6 months following overdose.

Of patients with VA opioid prescriptions, within 2 years of NFO, 9 (42.9%) had their opioids discontinued, and 18 (85.7%) had MEDD reductions ranging from 10 mg to 150 mg (12.5-71.4% reduction) with a mean of 63 mg. Two of the 4 patients with active BZD prescriptions at the time of the overdose event had their prescriptions continued. Seven patients (20.0%) were dispensed naloxone kits following overdose (Table 2).

Rates of ORAEs ranged from 0% to 17% with no documented overdose fatalities. Examples of AEs observed in this study included ED visits or hospitalizations involving opioid withdrawal, opioid-related personality changes, and opioid overdose. Five patients died during the study period, yielding an all-cause mortality rate of 14.3% with a mean time to death of 10.8 months. The causes of death were largely unknown except for 1 patient, whose death was reportedly investigated as an accidental medication overdose without additional information.

Repeat overdose verified by hospital records occurred in 4 patients (11.4%) within 2 years. Patients who experienced a subsequent overdose were prescribed higher doses of opioids with a mean MEDD among VA prescriptions of 130 mg vs 114 mg for those without repeat overdose. In this group, 3 patients (75.0%) also had concomitant BZD use, which was proportionally higher than the 10 patients (32.3%) without a subsequent overdose. Of note, 2 of the 4 patients with a repeat overdose had their opioid doses increased above the MEDD prescribed at the time of index overdose. None of the 4 subjects who experienced a repeat overdose were initiated on MAT within 2 years according to VA records.

Discussions

This retrospective study is representative of many veterans receiving VA care, despite the small sample size. Clinical characteristics observed in the study population were generally consistent with those published by Clement and Stock, including high rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidities.12 Subjects in both studies were prescribed comparable dosages of opioids; among those prescribed opioids but not BZDs through the VA, the mean MEDD was 117 mg in our study compared with 126 mg in the Clement and Stock study. Since implementation of the Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) in 2013, opioid prescribing practices have improved nationwide across VA facilities, including successful reduction in the numbers of patients prescribed high-dose opioids and concurrent BZDs.13

Despite the tools and resources available to clinicians, discontinuing opioid therapy remains a difficult process. Concerns related to mental health and/or substance-use related decompensations often exist in the setting of rapid dose reductions or abrupt discontinuation of opioids.6 Although less than half of patients in the present study with an active opioid prescription at time of index overdose had their opioids discontinued within 2 years, it is reassuring to note the much higher rate of those with subsequent decreases in their prescribed doses, as well as the 50% reduction in BZD coprescribing. Ultimately, these findings remain consistent with the VA goals of mitigating harm, improving opioid prescribing, and ensuring the safe use of opioid medications when clinically appropriate.

Moreover, recent evidence suggests that interventions focused solely on opioid prescribing practices are becoming increasingly limited in their impact on reducing opioid-related deaths and will likely be insufficient for addressing the opioid epidemic as it continues to evolve. According to Chen and colleagues, opioid overdose deaths are projected to increase over the next several years, while further reduction in the incidence of prescription opioid misuse is estimated to decrease overdose deaths by only 3% to 5.3%. In the context of recent surges in synthetic opioid use, it is projected that 80% of overdose deaths between 2016 and 2025 will be attributable to illicit opioids.3 Such predictions underscore the urgent need to adopt alternative approaches to risk-reducing measures and policy change.

The increased risk of mortality associated with opioid misuse and overdose is well established in the current literature. However, less is known regarding the rate of ORAEs after survival of an NFO. Olfson and colleagues sought to address this knowledge gap by characterizing mortality risks in 76,325 US adults within 1 year following NFO.14 Among their studied population, all-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 778.3 per 10,000 person-years, which was 24 times greater than that of the general population. This emphasizes the need for the optimization of mental health services, addiction treatment, and medical care for these individuals at higher risk.

Limitations

Certain factors and limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Given that the study included only veterans, factors such as the demographic and clinical characteristics more commonly observed among these patients should be taken into account and may in turn limit the generalizability of these findings to nonveteran populations. Another major limitation is the small sample size; the study period and by extension, the number of patients able to be included in the present study were restricted by the availability of retrievable data from automated drug dispensing systems. Patients without documented response to naloxone were excluded from the study due to low clinical suspicion for opioid overdose, although the possibility that the dose administered was too low to produce a robust clinical response cannot be definitively ruled out. The lack of reliable methods to capture events and overdoses treated outside of the VA may have resulted in underestimations of the true occurrence of ORAEs following NFO. Information regarding naloxone administration outside VA facilities, such as in transport to the hospital, self-reported, or bystander administration, was similarly limited by lack of reliable methods for retrieving such data and absence of documentation in VA records. Although all interventions and outcomes reported in the present study occurred within 2 years following NFO, further conclusions pertaining to the relative timing of specific interventions and ORAEs cannot be made. Lastly, this study did not investigate the direct impact of opioid risk mitigation initiatives implemented by the VA in the years coinciding with the study period.

Future Directions

Despite these limitations, an important strength of this study is its ability to identify potential areas for targeted improvement and to guide further efforts relating to the prevention of opioid overdose and opioid-related mortality among veterans. Identification of individuals at high risk for opioid overdose and misuse is an imperative first step that allows for the implementation of downstream risk-mitigating interventions. Within the VA, several tools have been developed in recent years to provide clinicians with additional resources and support in this regard.6,15

No more than half of those diagnosed with mental health disorders and SUDs in the present study received outpatient follow-up care for these conditions within 6 months following NFO, which may suggest high rates of inadequate treatment. Given the strong association between mental health disorders, SUDs, and increased risk of overdose, increasing engagement with mental health and addiction treatment services may be paramount to preventing subsequent ORAEs, including repeat overdose.6-9,11

Naloxone kit dispensing represents another area for targeted improvement. Interventions may include clinician education and systematic changes, such as implementing protocols that boost the likelihood of high-risk individuals being provided with naloxone at the earliest opportunity. Bystander-administered naloxone programs can also be considered for increasing naloxone access and reducing opioid-related mortality.16

Finally, despite evidence supporting the benefit of MAT in OUD treatment and reducing all-cause and opioid-related mortality after NFO, the low rates of MAT observed in this study are consistent with previous reports that these medications remain underutilized.17 Screening for OUD, in conjunction with increasing access to and utilization of OUD treatment modalities, is an established and integral component of overdose prevention efforts. For VA clinicians, the Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI) dashboard can be used to identify patients diagnosed with OUD who are not yet on MAT.18 Initiatives to expand MAT access through the ED have the potential to provide life-saving interventions and bridge care in the interim until patients are able to become established with a long-term health care practitioner.19

Conclusions

This is the first study to describe HSU, medication interventions, and ORAEs among veterans who survive NFO. Studies have shown that veterans with a history of NFO are at increased risk of subsequent AEs and premature death.6,7,10,14 As such, NFOs represent crucial opportunities to identify high-risk individuals and ensure provision of adequate care. Recent data supports the development of a holistic, multimodal approach focused on adequate treatment of conditions that contribute to opioid-related risks, including mental health disorders, SUDs, pain diagnoses, and medical comorbidities.3,14 Interventions designed to improve access, engagement, and retention in such care therefore play a pivotal role in overdose prevention and reducing mortality.

Although existing risk mitigation initiatives have improved opioid prescribing and safety within the VA, the findings of this study suggest that there remains room for improvement, and the need for well-coordinated efforts to reduce risks associated with both prescribed and illicit opioid use cannot be overstated. Rates of overdose deaths not only remain high but are projected to continue increasing in coming years, despite advances in clinical practice aimed at reducing harms associated with opioid use. The present findings aim to help identify processes with the potential to reduce rates of overdose, death, and adverse sequelae in high-risk populations. However, future studies are warranted to expand on these findings and contribute to ongoing efforts in reducing opioid-related harms and overdose deaths. This study may provide critical insight to inform further investigations to guide such interventions and highlight tools that health care facilities even outside the VA can consider implementing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jonathan Lacro, PharmD, BCPP, for his guidance with this important clinical topic and navigating IRB submissions.

The number of opioid-related overdose deaths in the United States is estimated to have increased 6-fold over the past 2 decades.1 In 2017, more than two-thirds of drug overdose deaths involved opioids, yielding a mortality rate of 14.9 per 100,000.2 Not only does the opioid epidemic currently pose a significant public health crisis characterized by high morbidity and mortality, but it is also projected to worsen in coming years. According to Chen and colleagues, opioid overdose deaths are estimated to increase by 147% from 2015 to 2025.3 That projects almost 82,000 US deaths annually and > 700,000 deaths in this period—even before accounting for surges in opioid overdoses and opioid-related mortality coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic.3,4

As health systems and communities globally struggle with unprecedented losses and stressors introduced by the pandemic, emerging data warrants escalating concerns with regard to increased vulnerability to relapse and overdose among those with mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs). In a recent report, the American Medical Association estimates that opioid-related deaths have increased in more than 40 states with the COVID-19 pandemic.4

Veterans are twice as likely to experience a fatal opioid overdose compared with their civilian counterparts.5 While several risk mitigation strategies have been employed in recent years to improve opioid prescribing and safety within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), veterans continue to overdose on opioids, both prescribed and obtained illicitly.6 Variables shown to be strongly associated with opioid overdose risk include presence of mental health disorders, SUDs, medical conditions involving impaired drug metabolism or excretion, respiratory disorders, higher doses of opioids, concomitant use of sedative medications, and history of overdose.6-8 Many veterans struggle with chronic pain and those prescribed high doses of opioids were more likely to have comorbid pain diagnoses, mental health disorders, and SUDs.9 Dashboards and predictive models, such as the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) and the Risk Index for Overdose or Serious Opioid-induced Respiratory Depression (RIOSORD), incorporate such factors to stratify overdose risk among veterans, in an effort to prioritize high-risk individuals for review and provision of care.6,10,11 Despite recent recognition that overdose prevention likely requires a holistic approach that addresses the biopsychosocial factors contributing to opioid-related morbidity and mortality, it is unclear whether veterans are receiving adequate and appropriate treatment for contributing conditions.

There are currently no existing studies that describe health service utilization (HSU), medication interventions, and rates of opioid-related adverse events (ORAEs) among veterans after survival of a nonfatal opioid overdose (NFO). Clinical characteristics of veterans treated for opioid overdose at a VA emergency department (ED) have previously been described by Clement and Stock.12 Despite improvements that have been made in VA opioid prescribing and safety, knowledge gaps remain with regard to best practices for opioid overdose prevention. The aim of this study was to characterize HSU and medication interventions in veterans following NFO, as well as the frequency of ORAEs after overdose. The findings of this study may aid in the identification of areas for targeted improvement in the prevention and reduction of opioid overdoses and adverse opioid-related sequelae.

Methods

This retrospective descriptive study was conducted at VA San Diego Healthcare System (VASDHCS) in California. Subjects included were veterans administered naloxone in the ED for suspected opioid overdose between July 1, 2013 and April 1, 2017. The study population was identified through data retrieved from automated drug dispensing systems, which was then confirmed through manual chart review of notes associated with the index ED visit. Inclusion criteria included documented increased respiration or responsiveness following naloxone administration. Subjects were excluded if they demonstrated lack of response to naloxone, overdosed secondary to inpatient administration of opioids, received palliative or hospice care during the study period, or were lost to follow-up.

Data were collected via retrospective chart review and included date of index ED visit, demographics, active prescriptions, urine drug screen (UDS) results, benzodiazepine (BZD) use corroborated by positive UDS or mention of BZD in index visit chart notes, whether overdose was determined to be a suicide attempt, and naloxone kit dispensing. Patient data was collected for 2 years following overdose, including: ORAEs; ED visits; hospitalizations; repeat overdoses; fatal overdose; whether subjects were still alive; follow-up visits for pain management, mental health, and addiction treatment services; and visits to the psychiatric emergency clinic. Clinical characteristics, such as mental health disorder diagnoses, SUDs, and relevant medical conditions also were collected. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel and included only descriptive statistics.

Results

Ninety-three patients received naloxone in the VASDHCS ED. Thirty-five met inclusion criteria and were included in the primary analysis. All subjects received IV naloxone with a mean 0.8 mg IV boluses (range, 0.1-4.4 mg).

Most patients were male with a mean age of 59.8 years (Table 1). Almost all overdoses were nonintentional except for 3 suicide attempts that were reviewed by the Suicide Prevention Committee. Three patients had previously been treated for opioid overdose at the VA with a documented positive clinical response to naloxone administration.

At the time of overdose, 29 patients (82.9%) had an active opioid prescription. Of these, the majority were issued through the VA with a mean 117 mg morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD). Interestingly, only 24 of the 28 patients with a UDS collected at time of overdose tested positive for opioids, which may be attributable to the use of synthetic opioids, which are not reliably detected by traditional UDS. Concomitant BZD use was involved in 13 of the 35 index overdoses (37.1%), although only 6 patients (17.1%) had an active BZD prescription at time of overdose. Seven patients (20.0%) were prescribed medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder (OUD), with all 7 using methadone. According to VA records, only 1 patient had previously been dispensed a naloxone kit at any point prior to overdosing. Mental health and SUD diagnoses frequently co-occurred, with 20 patients (57.1%) having at least 1 mental health condition and at least 1 SUD.

Rates of follow-up varied by clinician type in the 6 months after NFO (Figure). Of those with mental health disorders, 15 patients (45.5%) received mental health services before and after overdose, while 8 (40.0%) and 10 (50.0%) of those with SUDs received addiction treatment services before and after overdose, respectively. Seven patients presented to the psychiatric emergency clinic within 6 months prior to overdose and 5 patients within the 6 months following overdose.

Of patients with VA opioid prescriptions, within 2 years of NFO, 9 (42.9%) had their opioids discontinued, and 18 (85.7%) had MEDD reductions ranging from 10 mg to 150 mg (12.5-71.4% reduction) with a mean of 63 mg. Two of the 4 patients with active BZD prescriptions at the time of the overdose event had their prescriptions continued. Seven patients (20.0%) were dispensed naloxone kits following overdose (Table 2).

Rates of ORAEs ranged from 0% to 17% with no documented overdose fatalities. Examples of AEs observed in this study included ED visits or hospitalizations involving opioid withdrawal, opioid-related personality changes, and opioid overdose. Five patients died during the study period, yielding an all-cause mortality rate of 14.3% with a mean time to death of 10.8 months. The causes of death were largely unknown except for 1 patient, whose death was reportedly investigated as an accidental medication overdose without additional information.

Repeat overdose verified by hospital records occurred in 4 patients (11.4%) within 2 years. Patients who experienced a subsequent overdose were prescribed higher doses of opioids with a mean MEDD among VA prescriptions of 130 mg vs 114 mg for those without repeat overdose. In this group, 3 patients (75.0%) also had concomitant BZD use, which was proportionally higher than the 10 patients (32.3%) without a subsequent overdose. Of note, 2 of the 4 patients with a repeat overdose had their opioid doses increased above the MEDD prescribed at the time of index overdose. None of the 4 subjects who experienced a repeat overdose were initiated on MAT within 2 years according to VA records.

Discussions

This retrospective study is representative of many veterans receiving VA care, despite the small sample size. Clinical characteristics observed in the study population were generally consistent with those published by Clement and Stock, including high rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidities.12 Subjects in both studies were prescribed comparable dosages of opioids; among those prescribed opioids but not BZDs through the VA, the mean MEDD was 117 mg in our study compared with 126 mg in the Clement and Stock study. Since implementation of the Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) in 2013, opioid prescribing practices have improved nationwide across VA facilities, including successful reduction in the numbers of patients prescribed high-dose opioids and concurrent BZDs.13

Despite the tools and resources available to clinicians, discontinuing opioid therapy remains a difficult process. Concerns related to mental health and/or substance-use related decompensations often exist in the setting of rapid dose reductions or abrupt discontinuation of opioids.6 Although less than half of patients in the present study with an active opioid prescription at time of index overdose had their opioids discontinued within 2 years, it is reassuring to note the much higher rate of those with subsequent decreases in their prescribed doses, as well as the 50% reduction in BZD coprescribing. Ultimately, these findings remain consistent with the VA goals of mitigating harm, improving opioid prescribing, and ensuring the safe use of opioid medications when clinically appropriate.

Moreover, recent evidence suggests that interventions focused solely on opioid prescribing practices are becoming increasingly limited in their impact on reducing opioid-related deaths and will likely be insufficient for addressing the opioid epidemic as it continues to evolve. According to Chen and colleagues, opioid overdose deaths are projected to increase over the next several years, while further reduction in the incidence of prescription opioid misuse is estimated to decrease overdose deaths by only 3% to 5.3%. In the context of recent surges in synthetic opioid use, it is projected that 80% of overdose deaths between 2016 and 2025 will be attributable to illicit opioids.3 Such predictions underscore the urgent need to adopt alternative approaches to risk-reducing measures and policy change.

The increased risk of mortality associated with opioid misuse and overdose is well established in the current literature. However, less is known regarding the rate of ORAEs after survival of an NFO. Olfson and colleagues sought to address this knowledge gap by characterizing mortality risks in 76,325 US adults within 1 year following NFO.14 Among their studied population, all-cause mortality occurred at a rate of 778.3 per 10,000 person-years, which was 24 times greater than that of the general population. This emphasizes the need for the optimization of mental health services, addiction treatment, and medical care for these individuals at higher risk.

Limitations

Certain factors and limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Given that the study included only veterans, factors such as the demographic and clinical characteristics more commonly observed among these patients should be taken into account and may in turn limit the generalizability of these findings to nonveteran populations. Another major limitation is the small sample size; the study period and by extension, the number of patients able to be included in the present study were restricted by the availability of retrievable data from automated drug dispensing systems. Patients without documented response to naloxone were excluded from the study due to low clinical suspicion for opioid overdose, although the possibility that the dose administered was too low to produce a robust clinical response cannot be definitively ruled out. The lack of reliable methods to capture events and overdoses treated outside of the VA may have resulted in underestimations of the true occurrence of ORAEs following NFO. Information regarding naloxone administration outside VA facilities, such as in transport to the hospital, self-reported, or bystander administration, was similarly limited by lack of reliable methods for retrieving such data and absence of documentation in VA records. Although all interventions and outcomes reported in the present study occurred within 2 years following NFO, further conclusions pertaining to the relative timing of specific interventions and ORAEs cannot be made. Lastly, this study did not investigate the direct impact of opioid risk mitigation initiatives implemented by the VA in the years coinciding with the study period.

Future Directions

Despite these limitations, an important strength of this study is its ability to identify potential areas for targeted improvement and to guide further efforts relating to the prevention of opioid overdose and opioid-related mortality among veterans. Identification of individuals at high risk for opioid overdose and misuse is an imperative first step that allows for the implementation of downstream risk-mitigating interventions. Within the VA, several tools have been developed in recent years to provide clinicians with additional resources and support in this regard.6,15

No more than half of those diagnosed with mental health disorders and SUDs in the present study received outpatient follow-up care for these conditions within 6 months following NFO, which may suggest high rates of inadequate treatment. Given the strong association between mental health disorders, SUDs, and increased risk of overdose, increasing engagement with mental health and addiction treatment services may be paramount to preventing subsequent ORAEs, including repeat overdose.6-9,11

Naloxone kit dispensing represents another area for targeted improvement. Interventions may include clinician education and systematic changes, such as implementing protocols that boost the likelihood of high-risk individuals being provided with naloxone at the earliest opportunity. Bystander-administered naloxone programs can also be considered for increasing naloxone access and reducing opioid-related mortality.16

Finally, despite evidence supporting the benefit of MAT in OUD treatment and reducing all-cause and opioid-related mortality after NFO, the low rates of MAT observed in this study are consistent with previous reports that these medications remain underutilized.17 Screening for OUD, in conjunction with increasing access to and utilization of OUD treatment modalities, is an established and integral component of overdose prevention efforts. For VA clinicians, the Psychotropic Drug Safety Initiative (PDSI) dashboard can be used to identify patients diagnosed with OUD who are not yet on MAT.18 Initiatives to expand MAT access through the ED have the potential to provide life-saving interventions and bridge care in the interim until patients are able to become established with a long-term health care practitioner.19

Conclusions

This is the first study to describe HSU, medication interventions, and ORAEs among veterans who survive NFO. Studies have shown that veterans with a history of NFO are at increased risk of subsequent AEs and premature death.6,7,10,14 As such, NFOs represent crucial opportunities to identify high-risk individuals and ensure provision of adequate care. Recent data supports the development of a holistic, multimodal approach focused on adequate treatment of conditions that contribute to opioid-related risks, including mental health disorders, SUDs, pain diagnoses, and medical comorbidities.3,14 Interventions designed to improve access, engagement, and retention in such care therefore play a pivotal role in overdose prevention and reducing mortality.

Although existing risk mitigation initiatives have improved opioid prescribing and safety within the VA, the findings of this study suggest that there remains room for improvement, and the need for well-coordinated efforts to reduce risks associated with both prescribed and illicit opioid use cannot be overstated. Rates of overdose deaths not only remain high but are projected to continue increasing in coming years, despite advances in clinical practice aimed at reducing harms associated with opioid use. The present findings aim to help identify processes with the potential to reduce rates of overdose, death, and adverse sequelae in high-risk populations. However, future studies are warranted to expand on these findings and contribute to ongoing efforts in reducing opioid-related harms and overdose deaths. This study may provide critical insight to inform further investigations to guide such interventions and highlight tools that health care facilities even outside the VA can consider implementing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jonathan Lacro, PharmD, BCPP, for his guidance with this important clinical topic and navigating IRB submissions.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data overview: the drug overdose epidemic: behind the numbers. Updated March 25, 2021. Accessed February 9, 2022. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/index.html

2. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427. Published 2018 Jan 4. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1 3. Chen Q, Larochelle MR, Weaver DT, et al. Prevention of prescription opioid misuse and projected overdose deaths in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187621. Published 2019 Feb 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7621

4. American Medical Association. Issue brief: nation’s drug-related overdose and death epidemic continues to worsen. Updated November 12, 2021. Accessed February 11, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/issue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf

5. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Galea S, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Accidental poisoning mortality among patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health System. Med Care. 2011;49(4):393-396. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202aa27

6. Lewis ET, Trafton J, Oliva E. Data-based case reviews of patients with opioid related risk factors as a tool to prevent overdose and suicide. Accessed February 9, 2022. www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/2488-notes.pdf

7. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Risk factors for serious prescription opioid-related toxicity or overdose among Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1911-1929. doi:10.1111/pme.12480

8. Webster LR. Risk Factors for Opioid-Use Disorder and Overdose. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1741-1748. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002496

9. Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Carr TP, Deyo RA, Dobscha SK. Clinical characteristics of veterans prescribed high doses of opioid medications for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2010;151(3):625-632. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.002

10. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

11. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Development of a risk index for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose in Veterans’ Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):1566-1579. doi:10.1111/pme.12777

12. Clement C, Stock C. Who Overdoses at a VA Emergency Department? Fed Pract. 2016;33(11):14-20.

13. Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the Opioid Safety Initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158(5):833-839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837

14. Olfson M, Crystal S, Wall M, Wang S, Liu SM, Blanco C. Causes of death after nonfatal opioid overdose [published correction appears in JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Aug 1;75(8):867]. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):820-827. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1471

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA pain management – opioid safety – clinical tools. Updated November 14, 2019. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/Opioid_Safety/Clinical_Tools.asp

16. Doe-Simkins M, Walley AY, Epstein A, Moyer P. Saved by the nose: bystander-administered intranasal naloxone hydrochloride for opioid overdose. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):788-791. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.146647

17. Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):137-145. doi:10.7326/M17-3107

18. Wiechers I. Program focuses on safe psychiatric medication. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://blogs.va.gov/VAntage/27099/program-focuses-safe-psychiatric-medication/

19. Newman S; California Health Care Foundation. How to pay for it – MAT in the emergency department: FAQ. Published March 2019. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/HowToPayForMATinED.pdf

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data overview: the drug overdose epidemic: behind the numbers. Updated March 25, 2021. Accessed February 9, 2022. www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/index.html

2. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427. Published 2018 Jan 4. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1 3. Chen Q, Larochelle MR, Weaver DT, et al. Prevention of prescription opioid misuse and projected overdose deaths in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187621. Published 2019 Feb 1. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7621

4. American Medical Association. Issue brief: nation’s drug-related overdose and death epidemic continues to worsen. Updated November 12, 2021. Accessed February 11, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/issue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf

5. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Galea S, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Accidental poisoning mortality among patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health System. Med Care. 2011;49(4):393-396. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202aa27

6. Lewis ET, Trafton J, Oliva E. Data-based case reviews of patients with opioid related risk factors as a tool to prevent overdose and suicide. Accessed February 9, 2022. www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/2488-notes.pdf

7. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Risk factors for serious prescription opioid-related toxicity or overdose among Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1911-1929. doi:10.1111/pme.12480

8. Webster LR. Risk Factors for Opioid-Use Disorder and Overdose. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1741-1748. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002496

9. Morasco BJ, Duckart JP, Carr TP, Deyo RA, Dobscha SK. Clinical characteristics of veterans prescribed high doses of opioid medications for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2010;151(3):625-632. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.002

10. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

11. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Development of a risk index for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose in Veterans’ Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):1566-1579. doi:10.1111/pme.12777

12. Clement C, Stock C. Who Overdoses at a VA Emergency Department? Fed Pract. 2016;33(11):14-20.

13. Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the Opioid Safety Initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158(5):833-839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837

14. Olfson M, Crystal S, Wall M, Wang S, Liu SM, Blanco C. Causes of death after nonfatal opioid overdose [published correction appears in JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Aug 1;75(8):867]. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):820-827. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1471

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA pain management – opioid safety – clinical tools. Updated November 14, 2019. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/Opioid_Safety/Clinical_Tools.asp

16. Doe-Simkins M, Walley AY, Epstein A, Moyer P. Saved by the nose: bystander-administered intranasal naloxone hydrochloride for opioid overdose. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(5):788-791. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2008.146647

17. Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(3):137-145. doi:10.7326/M17-3107

18. Wiechers I. Program focuses on safe psychiatric medication. Published April 21, 2016. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://blogs.va.gov/VAntage/27099/program-focuses-safe-psychiatric-medication/

19. Newman S; California Health Care Foundation. How to pay for it – MAT in the emergency department: FAQ. Published March 2019. Accessed February 9, 2022. https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/HowToPayForMATinED.pdf

Mindfulness intervention curbs opioid misuse, chronic pain

In a randomized clinical trial, 250 adults with both opioid misuse and chronic pain received either the intervention, called mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement (MORE), or supportive psychotherapy.

Results showed the first group was twice as likely to reduce opioid misuse after 9 months than the latter group.

The intervention was developed by Eric Garland, PhD, director of the Center on Mindfulness and Integrative Health Intervention Development (C-MIIND), University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “As the largest and longest-term clinical trial of MORE ever conducted, this study definitively establishes the efficacy of MORE as a treatment for chronic pain and opioid misuse,” he told this news organization.

The findings were published online Feb. 28 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Self-regulation

Study participants included 250 adults (64% women; mean age, 51.8 years) with co-occurring opioid misuse and chronic pain who were randomly allocated to receive MORE or supportive psychotherapy, which served as a control group.

Both interventions were delivered by trained clinical social workers in six primary care clinics in Utah to groups of 6-12 participants across 8 weekly 2-hour sessions.

The MORE intervention, detailed on Dr. Garland’s website, provides sequenced training in mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring skills.

Mindfulness consisted of meditation on breathing and body sensations to strengthen self-regulation of compulsive opioid use and to mitigate pain and opioid craving by reinterpreting these experiences as innocuous sensory information.

Reappraisal consisted of reframing maladaptive thoughts to decrease negative emotions and engender meaning in life.

Savoring consisted of training in focusing awareness on pleasurable events and sensations to amplify positive emotions and reward.

Fewer depressive symptoms

Through 9 months of follow-up, the MORE group had about a twofold greater likelihood than the supportive psychotherapy group for reduction in opioid misuse (odds ratio [OR], 2.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-3.61; P = .01)

“MORE reduced opioid misuse by 45% 9 months after the end of treatment, more than doubling the effect of standard supportive psychotherapy and exceeding the effect size of other therapies for opioid misuse among people with chronic pain,” Dr. Garland said.

Members of the MORE group experienced greater reduction in pain severity and pain-related functional interference compared with members of the control group.

“MORE’s effect size on chronic pain symptoms was greater than that observed for CBT, the current gold standard psychological treatment for chronic pain,” Dr. Garland noted.

Compared with supportive psychotherapy, MORE decreased emotional distress, depressive symptoms, and real-time reports of opioid craving in daily life.

“Although nearly 70% of participants met criteria for depression at the beginning of the trial, on average, patients in MORE no longer exhibited symptoms consistent with major depressive disorder by the end of the study,” Dr. Garland said.

The current study builds on prior studies of MORE showing similar results, as reported previously by this news organization.

MORE can be successfully delivered in routine primary care, Dr. Garland noted. “In this trial, we delivered MORE in conference rooms, break rooms, and lunch rooms at community primary care clinics,” he added.

‘Powerful program’

To date, Dr. Garland has trained more than 450 physicians, nurses, social workers, and psychologists in health care systems across the country to implement MORE as an insurance-reimbursable group visit for patients in need.

One of them is Nancy Sudak, MD, chief well-being officer and director of integrative health, Essentia Health, Duluth, Minn.

“MORE is a very powerful program that teaches patients how to turn down the volume of their pain. I’ve been quite impressed by the power of MORE,” Dr. Sudak told this news organization

She noted that “buy-in” from patients is key – and the more a clinician knows a patient, the easier the buy-in.

“I recruited most of the patients in my groups from my own practice, so I already knew the patients quite well and there wasn’t really a need to sell it,” Dr. Sudak said.

“We have tried to operationalize it through our system and find that, as long as our recruitment techniques are robust enough, it’s not that hard to find patients to fill the groups, especially because chronic pain is just so common,” she added.

Dr. Sudak has found that patients who participate in MORE “bond and learn with each other and support each other. Patients love it, providers love it, and it’s a way to address isolation and loneliness” that can come with certain conditions.

“There are really only upsides to the group visit model and I think we’ll be seeing quite a bit more of it in the future,” she added.

Evidence-based data

Anna Parisi, PhD, is also delivering MORE to patients. She told this news organization, she was “really drawn” to the MORE program because oftentimes patients who require the most sophisticated therapies receive the ones with the least evidence.

This is often “what folks in the community are getting when they’re struggling with substance use,” added Dr. Parisi, a postdoctoral research associate working with Dr. Garland at the University of Utah. Dr. Parisi was not a coauthor on the current study.

“With MORE, all of the strategies and techniques are tied to mechanistic studies of their efficacy, so you know that what you’re delivering has a rationale behind it,” she said.

Like Dr. Sudak, Dr. Parisi said her patients, for the most part, have been receptive to the program. Although at first some were skeptical about mindfulness – with one patient using the term “tree-hugging” – they found immediate benefit even after the first session.

“That really helps them stay motivated to finish the program,” Dr. Parisi said.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Garland serves as director of the Center on Mindfulness and Integrative Health Intervention Development, which provides MORE, mindfulness-based therapy, and CBT in the context of research trials for no cost to research participants. He receives honoraria and payment for delivering seminars, lectures, and teaching engagements related to training clinicians in MORE and mindfulness and receives royalties from BehaVR and from the sales of books related to MORE outside the submitted work. Dr. Sudak and Dr. Parisi have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a randomized clinical trial, 250 adults with both opioid misuse and chronic pain received either the intervention, called mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement (MORE), or supportive psychotherapy.

Results showed the first group was twice as likely to reduce opioid misuse after 9 months than the latter group.

The intervention was developed by Eric Garland, PhD, director of the Center on Mindfulness and Integrative Health Intervention Development (C-MIIND), University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “As the largest and longest-term clinical trial of MORE ever conducted, this study definitively establishes the efficacy of MORE as a treatment for chronic pain and opioid misuse,” he told this news organization.

The findings were published online Feb. 28 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Self-regulation

Study participants included 250 adults (64% women; mean age, 51.8 years) with co-occurring opioid misuse and chronic pain who were randomly allocated to receive MORE or supportive psychotherapy, which served as a control group.

Both interventions were delivered by trained clinical social workers in six primary care clinics in Utah to groups of 6-12 participants across 8 weekly 2-hour sessions.

The MORE intervention, detailed on Dr. Garland’s website, provides sequenced training in mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring skills.

Mindfulness consisted of meditation on breathing and body sensations to strengthen self-regulation of compulsive opioid use and to mitigate pain and opioid craving by reinterpreting these experiences as innocuous sensory information.

Reappraisal consisted of reframing maladaptive thoughts to decrease negative emotions and engender meaning in life.

Savoring consisted of training in focusing awareness on pleasurable events and sensations to amplify positive emotions and reward.

Fewer depressive symptoms

Through 9 months of follow-up, the MORE group had about a twofold greater likelihood than the supportive psychotherapy group for reduction in opioid misuse (odds ratio [OR], 2.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-3.61; P = .01)

“MORE reduced opioid misuse by 45% 9 months after the end of treatment, more than doubling the effect of standard supportive psychotherapy and exceeding the effect size of other therapies for opioid misuse among people with chronic pain,” Dr. Garland said.

Members of the MORE group experienced greater reduction in pain severity and pain-related functional interference compared with members of the control group.

“MORE’s effect size on chronic pain symptoms was greater than that observed for CBT, the current gold standard psychological treatment for chronic pain,” Dr. Garland noted.

Compared with supportive psychotherapy, MORE decreased emotional distress, depressive symptoms, and real-time reports of opioid craving in daily life.

“Although nearly 70% of participants met criteria for depression at the beginning of the trial, on average, patients in MORE no longer exhibited symptoms consistent with major depressive disorder by the end of the study,” Dr. Garland said.

The current study builds on prior studies of MORE showing similar results, as reported previously by this news organization.

MORE can be successfully delivered in routine primary care, Dr. Garland noted. “In this trial, we delivered MORE in conference rooms, break rooms, and lunch rooms at community primary care clinics,” he added.

‘Powerful program’

To date, Dr. Garland has trained more than 450 physicians, nurses, social workers, and psychologists in health care systems across the country to implement MORE as an insurance-reimbursable group visit for patients in need.

One of them is Nancy Sudak, MD, chief well-being officer and director of integrative health, Essentia Health, Duluth, Minn.

“MORE is a very powerful program that teaches patients how to turn down the volume of their pain. I’ve been quite impressed by the power of MORE,” Dr. Sudak told this news organization

She noted that “buy-in” from patients is key – and the more a clinician knows a patient, the easier the buy-in.

“I recruited most of the patients in my groups from my own practice, so I already knew the patients quite well and there wasn’t really a need to sell it,” Dr. Sudak said.

“We have tried to operationalize it through our system and find that, as long as our recruitment techniques are robust enough, it’s not that hard to find patients to fill the groups, especially because chronic pain is just so common,” she added.

Dr. Sudak has found that patients who participate in MORE “bond and learn with each other and support each other. Patients love it, providers love it, and it’s a way to address isolation and loneliness” that can come with certain conditions.

“There are really only upsides to the group visit model and I think we’ll be seeing quite a bit more of it in the future,” she added.

Evidence-based data

Anna Parisi, PhD, is also delivering MORE to patients. She told this news organization, she was “really drawn” to the MORE program because oftentimes patients who require the most sophisticated therapies receive the ones with the least evidence.

This is often “what folks in the community are getting when they’re struggling with substance use,” added Dr. Parisi, a postdoctoral research associate working with Dr. Garland at the University of Utah. Dr. Parisi was not a coauthor on the current study.

“With MORE, all of the strategies and techniques are tied to mechanistic studies of their efficacy, so you know that what you’re delivering has a rationale behind it,” she said.