User login

Digital treatment may help relieve PTSD, panic disorder

The 28-day home-based treatment, known as the capnometry guided respiratory intervention (CGRI), uses an app-based feedback protocol to normalize respiration and increase patients’ ability to cope with symptoms of stress, anxiety, and panic by providing real time breath-to-breath feedback of respiratory rate and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels via a nasal cannula.

Results from the large real-world study showed that over 65% of patients with PD and over 72% of those with PTSD responded to the treatment. In addition, almost 75% of participants adhered to the study protocol, with low dropout rates.

“The brief duration of treatment, high adherence rates, and clinical benefit suggests that CGRI provides an important addition to treatment options for PD and PTSD,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Digital Health.

‘New kid on the block’

The “respiratory dysregulation hypothesis” links CO2 sensitivity to panic attacks and PD, and similar reactivity has been identified in PTSD, but a “common limitation of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic approaches to PD and PTSD is that neither address the role of respiratory physiology and breathing style,” the investigators note.

The most widely studied treatment for PTSD is trauma-focused psychotherapy, in which the patient reviews and revisits the trauma, but it has a high dropout rate, study investigator Michael Telch, PhD, director of the Laboratory for the Study of Anxiety Disorders, University of Texas, Austin, told this news organization.

He described CGRI for PTSD as a “relatively new kid on the block, so to speak.” The intervention was cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of PD and PTSD in 2013 and 2018, respectively, and is currently available through the Veterans Administration for veterans with PTSD. It is also covered by some commercial insurance plans.

“The underlying assumption [of CGRI] is that a person can learn to develop skills for controlling some of their physiological reactions that are triggered as a result of trauma,” said Dr. Telch.

The device uses a biofeedback approach to give patients “greater control over their physiological reactions, such as hyperventilation and increased respiration rate, and the focus is on providing a sense of mastery,” he said.

Participants with PTSD were assigned to a health coach. The device was delivered to the patient’s home, and patients met with the trained coach weekly and could check in between visits via text or e-mail. Twice-daily sessions were recommended.

“The coach gets feedback about what’s happening with the patient’s respiration and end-tidal CO2 levels [etCO2] and instructs participants how to keep their respiration rate and etCO2 at a more normal level,” said Dr. Telch.

The CGRI “teaches a specific breathing style via a system providing real-time feedback of respiratory rate (RR) and exhaled carbon dioxide levels facilitated by data capture,” the authors note.

Sense of mastery

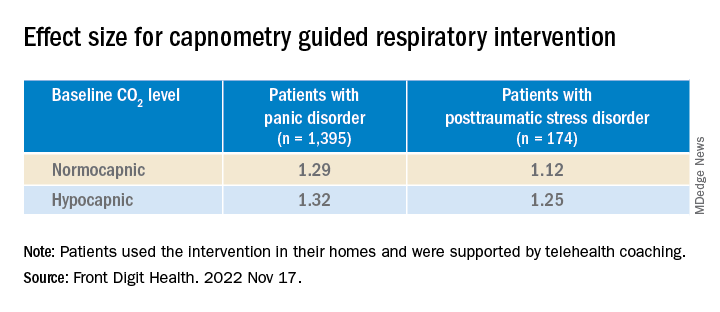

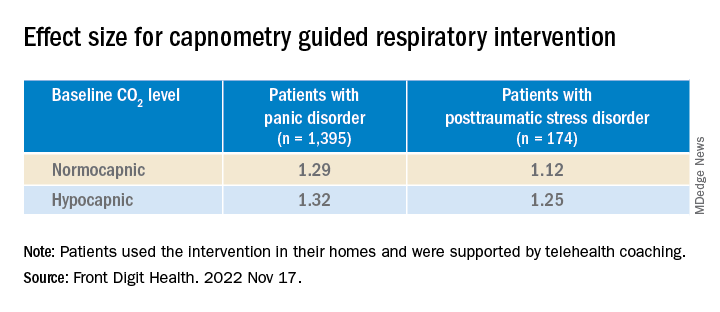

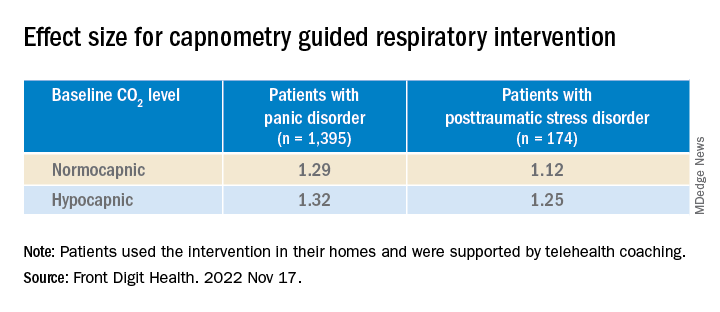

Of the 1,569 participants, 1,395 had PD and 174 had PTSD (mean age, 39.2 [standard deviation, 13.9] years and 40.9 [SD, 14.9] years, respectively; 76% and 73% female, respectively). Those with PD completed the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) and those with PTSD completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), before and after the intervention.

The treatment response rate for PD was defined as a 40% or greater reduction in PDSS total scores, whereas treatment response rate for PTSD was defined as a 10-point or greater reduction in PCL-5 scores.

At baseline, patients were classified either as normocapnic or hypocapnic (etCO2 ≥ 37 or < 37, respectively), with 65% classified as normocapnic and 35% classified as hypocapnic.

Among patients with PD, there was a 50.2% mean pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PDSS scores (P < .001; d = 1.31), with a treatment response rate of 65.3% of patients.

Among patients with PTSD, there was a 41.1% pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PCL-5 scores (P < .001; d = 1.16), with a treatment response rate of 72.4%.

When investigators analyzed the response at the individual level, they found that 55.7% of patients with PD and 53.5% of those with PTSD were classified as treatment responders. This determination was based on a two-pronged approach that first calculated the Reliable Change Index (RCI) for each participant, and, in participants showing statistically reliable improvement, whether the posttreatment score was closer to the distribution of scores for patients without or with the given disorder.

“Patients with both normal and below-normal baseline exhaled CO2 levels experienced comparable benefit,” the authors report.

There were high levels of adherence across the full treatment period in both the PD and the PTSD groups (74.8% and 74.9%, respectively), with low dropout rates (10% and 11%, respectively).

“Not every single patient who undergoes any treatment has a perfect response, but the response rates to this treatment have, surprisingly, been quite positive and there have been no negative side effects,” Dr. Telch remarked.

He noted that one of the effects of PTSD is that the “patient has negative beliefs about their ability to control the world. ‘I can’t control my reactions. At any time, I could have a flashback.’ Helping the patient to develop any sense of mastery over some of their reactions can spill over and give them a greater sense of mastery and control, which can have a positive effect in reducing PTSD symptoms.”

‘A viable alternative’

Commenting on the research, Charles Marmar, MD, chair and Peter H. Schub Professor of Psychiatry, department of psychiatry, New York University, said that the study has some limitations, probably the most significant of which is that most participants had normal baseline CO2 levels.

“The treatment is fundamentally designed for people who hyperventilate and blow off too much CO2 so they can breathe in a more calm, relaxed way, but most people in the trial had normal CO2 to begin with,” said Dr. Marmar, who was not involved with the study.

“It’s likely that the major benefits were the relaxation from doing the breathing exercises rather than the change in CO2 levels,” he speculated.

The treatment is “probably a good thing for those patients who actually have abnormal CO2 levels. This treatment could be used in precision medicine, where you tailor treatments to those who actually need them rather than giving the same treatment to everyone,” he said.

“For patients who don’t respond to trauma-focused therapy or it’s too aversive for them to undergo, this new intervention provides a viable alternative,” Dr. Telch added.

The study was internally funded by Freespira. Dr. Telch is a scientific advisor at Freespira and receives compensation by way of stock options. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Marmar has declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 28-day home-based treatment, known as the capnometry guided respiratory intervention (CGRI), uses an app-based feedback protocol to normalize respiration and increase patients’ ability to cope with symptoms of stress, anxiety, and panic by providing real time breath-to-breath feedback of respiratory rate and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels via a nasal cannula.

Results from the large real-world study showed that over 65% of patients with PD and over 72% of those with PTSD responded to the treatment. In addition, almost 75% of participants adhered to the study protocol, with low dropout rates.

“The brief duration of treatment, high adherence rates, and clinical benefit suggests that CGRI provides an important addition to treatment options for PD and PTSD,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Digital Health.

‘New kid on the block’

The “respiratory dysregulation hypothesis” links CO2 sensitivity to panic attacks and PD, and similar reactivity has been identified in PTSD, but a “common limitation of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic approaches to PD and PTSD is that neither address the role of respiratory physiology and breathing style,” the investigators note.

The most widely studied treatment for PTSD is trauma-focused psychotherapy, in which the patient reviews and revisits the trauma, but it has a high dropout rate, study investigator Michael Telch, PhD, director of the Laboratory for the Study of Anxiety Disorders, University of Texas, Austin, told this news organization.

He described CGRI for PTSD as a “relatively new kid on the block, so to speak.” The intervention was cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of PD and PTSD in 2013 and 2018, respectively, and is currently available through the Veterans Administration for veterans with PTSD. It is also covered by some commercial insurance plans.

“The underlying assumption [of CGRI] is that a person can learn to develop skills for controlling some of their physiological reactions that are triggered as a result of trauma,” said Dr. Telch.

The device uses a biofeedback approach to give patients “greater control over their physiological reactions, such as hyperventilation and increased respiration rate, and the focus is on providing a sense of mastery,” he said.

Participants with PTSD were assigned to a health coach. The device was delivered to the patient’s home, and patients met with the trained coach weekly and could check in between visits via text or e-mail. Twice-daily sessions were recommended.

“The coach gets feedback about what’s happening with the patient’s respiration and end-tidal CO2 levels [etCO2] and instructs participants how to keep their respiration rate and etCO2 at a more normal level,” said Dr. Telch.

The CGRI “teaches a specific breathing style via a system providing real-time feedback of respiratory rate (RR) and exhaled carbon dioxide levels facilitated by data capture,” the authors note.

Sense of mastery

Of the 1,569 participants, 1,395 had PD and 174 had PTSD (mean age, 39.2 [standard deviation, 13.9] years and 40.9 [SD, 14.9] years, respectively; 76% and 73% female, respectively). Those with PD completed the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) and those with PTSD completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), before and after the intervention.

The treatment response rate for PD was defined as a 40% or greater reduction in PDSS total scores, whereas treatment response rate for PTSD was defined as a 10-point or greater reduction in PCL-5 scores.

At baseline, patients were classified either as normocapnic or hypocapnic (etCO2 ≥ 37 or < 37, respectively), with 65% classified as normocapnic and 35% classified as hypocapnic.

Among patients with PD, there was a 50.2% mean pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PDSS scores (P < .001; d = 1.31), with a treatment response rate of 65.3% of patients.

Among patients with PTSD, there was a 41.1% pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PCL-5 scores (P < .001; d = 1.16), with a treatment response rate of 72.4%.

When investigators analyzed the response at the individual level, they found that 55.7% of patients with PD and 53.5% of those with PTSD were classified as treatment responders. This determination was based on a two-pronged approach that first calculated the Reliable Change Index (RCI) for each participant, and, in participants showing statistically reliable improvement, whether the posttreatment score was closer to the distribution of scores for patients without or with the given disorder.

“Patients with both normal and below-normal baseline exhaled CO2 levels experienced comparable benefit,” the authors report.

There were high levels of adherence across the full treatment period in both the PD and the PTSD groups (74.8% and 74.9%, respectively), with low dropout rates (10% and 11%, respectively).

“Not every single patient who undergoes any treatment has a perfect response, but the response rates to this treatment have, surprisingly, been quite positive and there have been no negative side effects,” Dr. Telch remarked.

He noted that one of the effects of PTSD is that the “patient has negative beliefs about their ability to control the world. ‘I can’t control my reactions. At any time, I could have a flashback.’ Helping the patient to develop any sense of mastery over some of their reactions can spill over and give them a greater sense of mastery and control, which can have a positive effect in reducing PTSD symptoms.”

‘A viable alternative’

Commenting on the research, Charles Marmar, MD, chair and Peter H. Schub Professor of Psychiatry, department of psychiatry, New York University, said that the study has some limitations, probably the most significant of which is that most participants had normal baseline CO2 levels.

“The treatment is fundamentally designed for people who hyperventilate and blow off too much CO2 so they can breathe in a more calm, relaxed way, but most people in the trial had normal CO2 to begin with,” said Dr. Marmar, who was not involved with the study.

“It’s likely that the major benefits were the relaxation from doing the breathing exercises rather than the change in CO2 levels,” he speculated.

The treatment is “probably a good thing for those patients who actually have abnormal CO2 levels. This treatment could be used in precision medicine, where you tailor treatments to those who actually need them rather than giving the same treatment to everyone,” he said.

“For patients who don’t respond to trauma-focused therapy or it’s too aversive for them to undergo, this new intervention provides a viable alternative,” Dr. Telch added.

The study was internally funded by Freespira. Dr. Telch is a scientific advisor at Freespira and receives compensation by way of stock options. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Marmar has declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The 28-day home-based treatment, known as the capnometry guided respiratory intervention (CGRI), uses an app-based feedback protocol to normalize respiration and increase patients’ ability to cope with symptoms of stress, anxiety, and panic by providing real time breath-to-breath feedback of respiratory rate and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels via a nasal cannula.

Results from the large real-world study showed that over 65% of patients with PD and over 72% of those with PTSD responded to the treatment. In addition, almost 75% of participants adhered to the study protocol, with low dropout rates.

“The brief duration of treatment, high adherence rates, and clinical benefit suggests that CGRI provides an important addition to treatment options for PD and PTSD,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Digital Health.

‘New kid on the block’

The “respiratory dysregulation hypothesis” links CO2 sensitivity to panic attacks and PD, and similar reactivity has been identified in PTSD, but a “common limitation of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic approaches to PD and PTSD is that neither address the role of respiratory physiology and breathing style,” the investigators note.

The most widely studied treatment for PTSD is trauma-focused psychotherapy, in which the patient reviews and revisits the trauma, but it has a high dropout rate, study investigator Michael Telch, PhD, director of the Laboratory for the Study of Anxiety Disorders, University of Texas, Austin, told this news organization.

He described CGRI for PTSD as a “relatively new kid on the block, so to speak.” The intervention was cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of PD and PTSD in 2013 and 2018, respectively, and is currently available through the Veterans Administration for veterans with PTSD. It is also covered by some commercial insurance plans.

“The underlying assumption [of CGRI] is that a person can learn to develop skills for controlling some of their physiological reactions that are triggered as a result of trauma,” said Dr. Telch.

The device uses a biofeedback approach to give patients “greater control over their physiological reactions, such as hyperventilation and increased respiration rate, and the focus is on providing a sense of mastery,” he said.

Participants with PTSD were assigned to a health coach. The device was delivered to the patient’s home, and patients met with the trained coach weekly and could check in between visits via text or e-mail. Twice-daily sessions were recommended.

“The coach gets feedback about what’s happening with the patient’s respiration and end-tidal CO2 levels [etCO2] and instructs participants how to keep their respiration rate and etCO2 at a more normal level,” said Dr. Telch.

The CGRI “teaches a specific breathing style via a system providing real-time feedback of respiratory rate (RR) and exhaled carbon dioxide levels facilitated by data capture,” the authors note.

Sense of mastery

Of the 1,569 participants, 1,395 had PD and 174 had PTSD (mean age, 39.2 [standard deviation, 13.9] years and 40.9 [SD, 14.9] years, respectively; 76% and 73% female, respectively). Those with PD completed the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) and those with PTSD completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), before and after the intervention.

The treatment response rate for PD was defined as a 40% or greater reduction in PDSS total scores, whereas treatment response rate for PTSD was defined as a 10-point or greater reduction in PCL-5 scores.

At baseline, patients were classified either as normocapnic or hypocapnic (etCO2 ≥ 37 or < 37, respectively), with 65% classified as normocapnic and 35% classified as hypocapnic.

Among patients with PD, there was a 50.2% mean pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PDSS scores (P < .001; d = 1.31), with a treatment response rate of 65.3% of patients.

Among patients with PTSD, there was a 41.1% pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PCL-5 scores (P < .001; d = 1.16), with a treatment response rate of 72.4%.

When investigators analyzed the response at the individual level, they found that 55.7% of patients with PD and 53.5% of those with PTSD were classified as treatment responders. This determination was based on a two-pronged approach that first calculated the Reliable Change Index (RCI) for each participant, and, in participants showing statistically reliable improvement, whether the posttreatment score was closer to the distribution of scores for patients without or with the given disorder.

“Patients with both normal and below-normal baseline exhaled CO2 levels experienced comparable benefit,” the authors report.

There were high levels of adherence across the full treatment period in both the PD and the PTSD groups (74.8% and 74.9%, respectively), with low dropout rates (10% and 11%, respectively).

“Not every single patient who undergoes any treatment has a perfect response, but the response rates to this treatment have, surprisingly, been quite positive and there have been no negative side effects,” Dr. Telch remarked.

He noted that one of the effects of PTSD is that the “patient has negative beliefs about their ability to control the world. ‘I can’t control my reactions. At any time, I could have a flashback.’ Helping the patient to develop any sense of mastery over some of their reactions can spill over and give them a greater sense of mastery and control, which can have a positive effect in reducing PTSD symptoms.”

‘A viable alternative’

Commenting on the research, Charles Marmar, MD, chair and Peter H. Schub Professor of Psychiatry, department of psychiatry, New York University, said that the study has some limitations, probably the most significant of which is that most participants had normal baseline CO2 levels.

“The treatment is fundamentally designed for people who hyperventilate and blow off too much CO2 so they can breathe in a more calm, relaxed way, but most people in the trial had normal CO2 to begin with,” said Dr. Marmar, who was not involved with the study.

“It’s likely that the major benefits were the relaxation from doing the breathing exercises rather than the change in CO2 levels,” he speculated.

The treatment is “probably a good thing for those patients who actually have abnormal CO2 levels. This treatment could be used in precision medicine, where you tailor treatments to those who actually need them rather than giving the same treatment to everyone,” he said.

“For patients who don’t respond to trauma-focused therapy or it’s too aversive for them to undergo, this new intervention provides a viable alternative,” Dr. Telch added.

The study was internally funded by Freespira. Dr. Telch is a scientific advisor at Freespira and receives compensation by way of stock options. The other authors’ disclosures are listed on the original paper. Dr. Marmar has declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FRONTIERS IN DIGITAL HEALTH

Visualization can improve sports performance

Over the past 30 years, Dr. Richard W. Cohen has used visualization techniques to help world class tennis players and recreational tennis players become the best they could be.

Visualization should be used in two ways to help players improve. First, to improve technique, after every practice session I have the player think about one shot they did not do well technically, and I have them, in vivo, shadow the shot on the court correctly before they leave the court. That night I tell the player to put themselves in a quiet, relaxed place and, in vitro, visualize themselves hitting the shot the correct way.

Almost always, the next day the players tell me they are hitting that one shot better and are motivated to again think about the one shot that was not technically correct and repeat the in vivo technique with similar great results.

The second way I use visualization for tennis players is to decrease their anxiety before matches. It is important to have some preparatory anxiety to perform optimally but having excessive anxiety will decrease performance. To alleviate excessive anxiety before matches, I have players watch their opponents hit the day before the match for at least 5 minutes to see their strengths and weaknesses. Then, the night before the match, I have them visualize how they will play a big point utilizing their strength into their opponent’s weakness. This rehearsal using imagery the night before a big match will decrease a player’s excessive anxiety and allow them to achieve their best effort in the match.

An example of this is if their opponent has a weak backhand that they can only slice. They visualize hitting wide to their forehand to get into their weak backhand and see themselves going forward and putting away a volley. Visualization used in these two ways helps improve stroke mechanics and match results in players of all levels. These visualization techniques can also be extended to other sports and to help improve life habits.

For example, Dr. Susan A. Cohen has seen that many patients have a decline in their dental health because of fear of going to the dentist to receive the treatment they need. Visualization techniques decrease the patient’s anxiety by rehearsing the possible traumatic events of the dental visit – e.g., the injection of anesthesia before the dental procedure. Visualization of calmness with systematic desensitization has helped decrease anxiety in patients.

In 20 years of clinical experience as a dentist, Dr. Cohen has seen how these techniques have increased compliance in her dental patients. She has also noted that visualizing the results of having a healthy mouth with improved appearance and function leads to an overall willingness to visit the dentist regularly and enjoy the dental experience. These examples demonstrate how visualization can enhance sports performance, quality of life, and overall health.

Dr. Richard W. Cohen is a psychiatrist who has been in private practice for over 40 years and is on the editorial advisory board for Clinical Psychiatry News. He has won 18 USTA national tennis championships. Dr. Susan A. Cohen has practiced dentistry for over 20 years. The Cohens, who are married, are based in Philadelphia.

Over the past 30 years, Dr. Richard W. Cohen has used visualization techniques to help world class tennis players and recreational tennis players become the best they could be.

Visualization should be used in two ways to help players improve. First, to improve technique, after every practice session I have the player think about one shot they did not do well technically, and I have them, in vivo, shadow the shot on the court correctly before they leave the court. That night I tell the player to put themselves in a quiet, relaxed place and, in vitro, visualize themselves hitting the shot the correct way.

Almost always, the next day the players tell me they are hitting that one shot better and are motivated to again think about the one shot that was not technically correct and repeat the in vivo technique with similar great results.

The second way I use visualization for tennis players is to decrease their anxiety before matches. It is important to have some preparatory anxiety to perform optimally but having excessive anxiety will decrease performance. To alleviate excessive anxiety before matches, I have players watch their opponents hit the day before the match for at least 5 minutes to see their strengths and weaknesses. Then, the night before the match, I have them visualize how they will play a big point utilizing their strength into their opponent’s weakness. This rehearsal using imagery the night before a big match will decrease a player’s excessive anxiety and allow them to achieve their best effort in the match.

An example of this is if their opponent has a weak backhand that they can only slice. They visualize hitting wide to their forehand to get into their weak backhand and see themselves going forward and putting away a volley. Visualization used in these two ways helps improve stroke mechanics and match results in players of all levels. These visualization techniques can also be extended to other sports and to help improve life habits.

For example, Dr. Susan A. Cohen has seen that many patients have a decline in their dental health because of fear of going to the dentist to receive the treatment they need. Visualization techniques decrease the patient’s anxiety by rehearsing the possible traumatic events of the dental visit – e.g., the injection of anesthesia before the dental procedure. Visualization of calmness with systematic desensitization has helped decrease anxiety in patients.

In 20 years of clinical experience as a dentist, Dr. Cohen has seen how these techniques have increased compliance in her dental patients. She has also noted that visualizing the results of having a healthy mouth with improved appearance and function leads to an overall willingness to visit the dentist regularly and enjoy the dental experience. These examples demonstrate how visualization can enhance sports performance, quality of life, and overall health.

Dr. Richard W. Cohen is a psychiatrist who has been in private practice for over 40 years and is on the editorial advisory board for Clinical Psychiatry News. He has won 18 USTA national tennis championships. Dr. Susan A. Cohen has practiced dentistry for over 20 years. The Cohens, who are married, are based in Philadelphia.

Over the past 30 years, Dr. Richard W. Cohen has used visualization techniques to help world class tennis players and recreational tennis players become the best they could be.

Visualization should be used in two ways to help players improve. First, to improve technique, after every practice session I have the player think about one shot they did not do well technically, and I have them, in vivo, shadow the shot on the court correctly before they leave the court. That night I tell the player to put themselves in a quiet, relaxed place and, in vitro, visualize themselves hitting the shot the correct way.

Almost always, the next day the players tell me they are hitting that one shot better and are motivated to again think about the one shot that was not technically correct and repeat the in vivo technique with similar great results.

The second way I use visualization for tennis players is to decrease their anxiety before matches. It is important to have some preparatory anxiety to perform optimally but having excessive anxiety will decrease performance. To alleviate excessive anxiety before matches, I have players watch their opponents hit the day before the match for at least 5 minutes to see their strengths and weaknesses. Then, the night before the match, I have them visualize how they will play a big point utilizing their strength into their opponent’s weakness. This rehearsal using imagery the night before a big match will decrease a player’s excessive anxiety and allow them to achieve their best effort in the match.

An example of this is if their opponent has a weak backhand that they can only slice. They visualize hitting wide to their forehand to get into their weak backhand and see themselves going forward and putting away a volley. Visualization used in these two ways helps improve stroke mechanics and match results in players of all levels. These visualization techniques can also be extended to other sports and to help improve life habits.

For example, Dr. Susan A. Cohen has seen that many patients have a decline in their dental health because of fear of going to the dentist to receive the treatment they need. Visualization techniques decrease the patient’s anxiety by rehearsing the possible traumatic events of the dental visit – e.g., the injection of anesthesia before the dental procedure. Visualization of calmness with systematic desensitization has helped decrease anxiety in patients.

In 20 years of clinical experience as a dentist, Dr. Cohen has seen how these techniques have increased compliance in her dental patients. She has also noted that visualizing the results of having a healthy mouth with improved appearance and function leads to an overall willingness to visit the dentist regularly and enjoy the dental experience. These examples demonstrate how visualization can enhance sports performance, quality of life, and overall health.

Dr. Richard W. Cohen is a psychiatrist who has been in private practice for over 40 years and is on the editorial advisory board for Clinical Psychiatry News. He has won 18 USTA national tennis championships. Dr. Susan A. Cohen has practiced dentistry for over 20 years. The Cohens, who are married, are based in Philadelphia.

What are the risk factors for Mohs surgery–related anxiety?

confirmed by a health care provider (HCP), results from a single-center survey demonstrated.

“Higher patient-reported anxiety in hospital settings is significantly linked to lower patient satisfaction with the quality of care and higher patient-reported postoperative pain,” corresponding author Ally-Khan Somani, MD, PhD, and colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online in Dermatologic Surgery. “Identifying factors associated with perioperative patient anxiety could improve outcomes and patient satisfaction.”

Dr. Somani, director of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology in the department of dermatology at the University of Indiana, Indianapolis, and coauthors surveyed 145 patients who underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) at the university from February 2018 to March 2020. They collected patient self-reported demographics, medical history, and administered a 10-point visual analog scale assessment of anxiety at multiple stages. They also sought HCP-perceived assessments of anxiety and used a stepwise regression mode to explore factors that potentially contributed to anxiety outcomes. The mean age of the 145 patients was 63 years, 60% were female, and 77% had no self-reported anxiety confirmed by a prior HCP’s diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients (66%) received a pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon, 59% had a history of skin cancer removal surgery, and 86% had 1-2 layers removed during the current MMS.

Prior to MMS, the researchers found that significant risk factors for increased anxiety included younger age, female sex, and self-reported history of anxiety confirmed by an HCP (P < .05), while intraoperatively, HCP-perceived patient anxiety increased with younger patient age and more layers removed. Following MMS, patient anxiety increased significantly with more layers removed and higher self-reported preoperative anxiety levels. “Although existing research is divided regarding the efficacy of pre-MMS consultation for anxiety reduction, these findings suggest that patient-reported and HCP-perceived anxiety were not significantly affected by in-person pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon,” Dr. Somani and colleagues wrote. “Thus, routinely recommending consultations may not be the best approach for improving anxiety outcomes.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of their analysis, including its single-center design, enrollment of demographically similar patients, and the fact that no objective measurements of anxiety such as heart rate or blood pressure were taken.

“One of the main benefits of Mohs surgery is that we are able to operate under local anesthesia, but this also means that our patients are acutely aware of everything going on around them,” said Patricia M. Richey, MD, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and was asked to comment on the study.

“I think it is so important that this study is primarily focusing on the patient experience,” she said. “While this study did not find that a pre-op consult impacted patient anxiety levels, I do think we can infer that it is critical to connect with your patients on some level prior to surgery, as it helps you tailor your process to make the day more tolerable for them [such as] playing music, determining the need for an oral anxiolytic, etc.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Richey reported having financial disclosures.

confirmed by a health care provider (HCP), results from a single-center survey demonstrated.

“Higher patient-reported anxiety in hospital settings is significantly linked to lower patient satisfaction with the quality of care and higher patient-reported postoperative pain,” corresponding author Ally-Khan Somani, MD, PhD, and colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online in Dermatologic Surgery. “Identifying factors associated with perioperative patient anxiety could improve outcomes and patient satisfaction.”

Dr. Somani, director of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology in the department of dermatology at the University of Indiana, Indianapolis, and coauthors surveyed 145 patients who underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) at the university from February 2018 to March 2020. They collected patient self-reported demographics, medical history, and administered a 10-point visual analog scale assessment of anxiety at multiple stages. They also sought HCP-perceived assessments of anxiety and used a stepwise regression mode to explore factors that potentially contributed to anxiety outcomes. The mean age of the 145 patients was 63 years, 60% were female, and 77% had no self-reported anxiety confirmed by a prior HCP’s diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients (66%) received a pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon, 59% had a history of skin cancer removal surgery, and 86% had 1-2 layers removed during the current MMS.

Prior to MMS, the researchers found that significant risk factors for increased anxiety included younger age, female sex, and self-reported history of anxiety confirmed by an HCP (P < .05), while intraoperatively, HCP-perceived patient anxiety increased with younger patient age and more layers removed. Following MMS, patient anxiety increased significantly with more layers removed and higher self-reported preoperative anxiety levels. “Although existing research is divided regarding the efficacy of pre-MMS consultation for anxiety reduction, these findings suggest that patient-reported and HCP-perceived anxiety were not significantly affected by in-person pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon,” Dr. Somani and colleagues wrote. “Thus, routinely recommending consultations may not be the best approach for improving anxiety outcomes.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of their analysis, including its single-center design, enrollment of demographically similar patients, and the fact that no objective measurements of anxiety such as heart rate or blood pressure were taken.

“One of the main benefits of Mohs surgery is that we are able to operate under local anesthesia, but this also means that our patients are acutely aware of everything going on around them,” said Patricia M. Richey, MD, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and was asked to comment on the study.

“I think it is so important that this study is primarily focusing on the patient experience,” she said. “While this study did not find that a pre-op consult impacted patient anxiety levels, I do think we can infer that it is critical to connect with your patients on some level prior to surgery, as it helps you tailor your process to make the day more tolerable for them [such as] playing music, determining the need for an oral anxiolytic, etc.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Richey reported having financial disclosures.

confirmed by a health care provider (HCP), results from a single-center survey demonstrated.

“Higher patient-reported anxiety in hospital settings is significantly linked to lower patient satisfaction with the quality of care and higher patient-reported postoperative pain,” corresponding author Ally-Khan Somani, MD, PhD, and colleagues wrote in the study, which was published online in Dermatologic Surgery. “Identifying factors associated with perioperative patient anxiety could improve outcomes and patient satisfaction.”

Dr. Somani, director of dermatologic surgery and cutaneous oncology in the department of dermatology at the University of Indiana, Indianapolis, and coauthors surveyed 145 patients who underwent Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) at the university from February 2018 to March 2020. They collected patient self-reported demographics, medical history, and administered a 10-point visual analog scale assessment of anxiety at multiple stages. They also sought HCP-perceived assessments of anxiety and used a stepwise regression mode to explore factors that potentially contributed to anxiety outcomes. The mean age of the 145 patients was 63 years, 60% were female, and 77% had no self-reported anxiety confirmed by a prior HCP’s diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients (66%) received a pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon, 59% had a history of skin cancer removal surgery, and 86% had 1-2 layers removed during the current MMS.

Prior to MMS, the researchers found that significant risk factors for increased anxiety included younger age, female sex, and self-reported history of anxiety confirmed by an HCP (P < .05), while intraoperatively, HCP-perceived patient anxiety increased with younger patient age and more layers removed. Following MMS, patient anxiety increased significantly with more layers removed and higher self-reported preoperative anxiety levels. “Although existing research is divided regarding the efficacy of pre-MMS consultation for anxiety reduction, these findings suggest that patient-reported and HCP-perceived anxiety were not significantly affected by in-person pre-MMS consultation with the surgeon,” Dr. Somani and colleagues wrote. “Thus, routinely recommending consultations may not be the best approach for improving anxiety outcomes.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of their analysis, including its single-center design, enrollment of demographically similar patients, and the fact that no objective measurements of anxiety such as heart rate or blood pressure were taken.

“One of the main benefits of Mohs surgery is that we are able to operate under local anesthesia, but this also means that our patients are acutely aware of everything going on around them,” said Patricia M. Richey, MD, who practices Mohs surgery and cosmetic dermatology in Washington, D.C., and was asked to comment on the study.

“I think it is so important that this study is primarily focusing on the patient experience,” she said. “While this study did not find that a pre-op consult impacted patient anxiety levels, I do think we can infer that it is critical to connect with your patients on some level prior to surgery, as it helps you tailor your process to make the day more tolerable for them [such as] playing music, determining the need for an oral anxiolytic, etc.”

Neither the researchers nor Dr. Richey reported having financial disclosures.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

New guidelines say pediatricians should screen for anxiety: Now what?

Recently the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a formal recommendation that adolescents and children as young as 8 should be screened for anxiety.1 The advice was based on a review of the research that concluded that anxiety disorders were common in youth (prevalence around 8%), screening was not overly burdensome or dangerous, and treatments were available and effective.

While pediatricians fully appreciate how common clinically significant anxiety is and its impact on the lives of youth, the reception for the recommendations have been mixed. Some are concerned that it could lead to the overprescribing of medications. Arguably, the biggest pushback, however, relates to the question of what to do when a child screens positive in a time when finding an available child and adolescent psychiatrist or other type of pediatric mental health professional can feel next to impossible. The hope of this article is to fill in some of those gaps.

Screening for anxiety disorders

The recommendations suggest using a rating scale as part of the screen but doesn’t dictate which one. A common instrument that has been employed is the Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Disorders, which is a freely available 41-item instrument that has versions for youth self-report and parent-report. A shorter 7-item rating scale, the General Anxiety Disorder–7, and the even shorter GAD-2 (the first two questions of the GAD-7), are also popular but focus, as the name applies, on general anxiety disorder and not related conditions such as social or separation anxiety that can have some different symptoms. These instruments can be given to patients and families in the waiting room or administered with the help of a nurse, physician, or embedded mental health professional. The recommendations do not include specific guidance on how often the screening should be done but repeated screenings are likely important at some interval.

Confirming the diagnosis

Of course, a screening isn’t a formal diagnosis. The American Academy of Pediatrics has expressed the view that the initial diagnosis and treatment for anxiety disorders is well within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, which means further steps are likely required beyond a referral. Fortunately, going from a positive screen to an initial diagnosis does not have to overly laborious and can focus on reviewing the DSM-5 criteria for key anxiety disorders while also ensuring that there isn’t a nonpsychiatric cause driving the symptoms, such as the often cited but rarely seen pheochromocytoma. More common rule-outs include medication-induced anxiety or substance use, excessive caffeine intake, and cardiac arrhythmias. Assessing for current and past trauma or specific causes of the anxiety such as bullying are also important.

It is important to note that it is the rule rather than the exception that youth with clinical levels of anxiety will frequently endorse a number of criteria that span multiple diagnoses including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and separation anxiety disorder.2 Spending a lot of effort to narrow things down to a single anxiety diagnosis often is unnecessary, as both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments don’t change all that much between individual diagnoses.

Explaining the diagnosis

In general, I’m a strong proponent of trying to explain any behavioral diagnoses that you make to kids in a way that is accurate but nonstigmatizing. When it comes to anxiety, one parallel I often draw is to our immune system, which most youth understand at least in basic terms. Both our immune system and our anxiety networks are natural and important; as a species, we wouldn’t have lasted long without them. Both are built to assess and respond to threats. Problems can arise, however, if the response is too strong relative to the threat or the response is activated when it doesn’t need to be. Treatment is directed not at ridding ourselves of anxiety but at helping regulate it so it works for us and not against us. Spending a few minutes going through a discussion like this can be very helpful, and perhaps more so than some dry summary of DSM-5 criteria.

Starting treatment

It is important to note that best practice recommendations when it comes to the treatment of anxiety disorder in youth do not suggest medications as the only type of treatment and often urge clinicians to try nonpharmacological interventions first.3 A specific type of psychotherapy called cognitive-behavioral therapy has the strongest scientific support as an effective treatment for anxiety but other modalities, including parenting guidance, can be helpful as well. Consequently, a referral to a good psychotherapist is paramount. For many kids, the key to overcoming anxiety is exposure: which means confronting anxiety slowly, with support, and with specific skills.

If there is a traumatic source of the anxiety, addressing that as much as possible is obviously critical and could involve working with the family or school. For some kids, this may involve frightening things they are seeing online or through other media. Finally, some health promotion activities such as exercise or mindfulness can also be quite useful.

Despite the fact that SSRIs are referred to as antidepressants, there is increasing appreciation that these medications are useful for anxiety, perhaps even more so than for mood. While only one medication, duloxetine, has Food and Drug Administration approval to treat anxiety in children as young as 7, there is good evidence to support the use of many of the most common SSRIs in treating clinical anxiety. Buspirone, beta-blockers, and antihistamine medications like hydroxyzine also can have their place in treatment, while benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications are generally best avoided for anxious youth, especially in the primary care setting. A short but helpful medication guide with regard to pediatric anxiety has been published by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.4

Conclusions

Clinical levels of anxiety in children and adolescents are both common and quite treatable, which has prompted new recommendations that primary care clinicians screen for them starting at age 8. While this recommendation may at first seem like yet one more task to fit in, following the guidance can be accomplished with the help of short screening tools and a managed multimodal approach to treatment.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1438-44.

2. Strawn JR. Curr Psychiatry. 2012;11(9):16-21.

3. Walter HJ et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(10):1107-24.

4. Anxiety Disorders: Parents’ Medication Guide Workgroup. “Anxiety disorders: Parents’ medication guide.” Washington D.C.: American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2020.

Recently the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a formal recommendation that adolescents and children as young as 8 should be screened for anxiety.1 The advice was based on a review of the research that concluded that anxiety disorders were common in youth (prevalence around 8%), screening was not overly burdensome or dangerous, and treatments were available and effective.

While pediatricians fully appreciate how common clinically significant anxiety is and its impact on the lives of youth, the reception for the recommendations have been mixed. Some are concerned that it could lead to the overprescribing of medications. Arguably, the biggest pushback, however, relates to the question of what to do when a child screens positive in a time when finding an available child and adolescent psychiatrist or other type of pediatric mental health professional can feel next to impossible. The hope of this article is to fill in some of those gaps.

Screening for anxiety disorders

The recommendations suggest using a rating scale as part of the screen but doesn’t dictate which one. A common instrument that has been employed is the Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Disorders, which is a freely available 41-item instrument that has versions for youth self-report and parent-report. A shorter 7-item rating scale, the General Anxiety Disorder–7, and the even shorter GAD-2 (the first two questions of the GAD-7), are also popular but focus, as the name applies, on general anxiety disorder and not related conditions such as social or separation anxiety that can have some different symptoms. These instruments can be given to patients and families in the waiting room or administered with the help of a nurse, physician, or embedded mental health professional. The recommendations do not include specific guidance on how often the screening should be done but repeated screenings are likely important at some interval.

Confirming the diagnosis

Of course, a screening isn’t a formal diagnosis. The American Academy of Pediatrics has expressed the view that the initial diagnosis and treatment for anxiety disorders is well within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, which means further steps are likely required beyond a referral. Fortunately, going from a positive screen to an initial diagnosis does not have to overly laborious and can focus on reviewing the DSM-5 criteria for key anxiety disorders while also ensuring that there isn’t a nonpsychiatric cause driving the symptoms, such as the often cited but rarely seen pheochromocytoma. More common rule-outs include medication-induced anxiety or substance use, excessive caffeine intake, and cardiac arrhythmias. Assessing for current and past trauma or specific causes of the anxiety such as bullying are also important.

It is important to note that it is the rule rather than the exception that youth with clinical levels of anxiety will frequently endorse a number of criteria that span multiple diagnoses including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and separation anxiety disorder.2 Spending a lot of effort to narrow things down to a single anxiety diagnosis often is unnecessary, as both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments don’t change all that much between individual diagnoses.

Explaining the diagnosis

In general, I’m a strong proponent of trying to explain any behavioral diagnoses that you make to kids in a way that is accurate but nonstigmatizing. When it comes to anxiety, one parallel I often draw is to our immune system, which most youth understand at least in basic terms. Both our immune system and our anxiety networks are natural and important; as a species, we wouldn’t have lasted long without them. Both are built to assess and respond to threats. Problems can arise, however, if the response is too strong relative to the threat or the response is activated when it doesn’t need to be. Treatment is directed not at ridding ourselves of anxiety but at helping regulate it so it works for us and not against us. Spending a few minutes going through a discussion like this can be very helpful, and perhaps more so than some dry summary of DSM-5 criteria.

Starting treatment

It is important to note that best practice recommendations when it comes to the treatment of anxiety disorder in youth do not suggest medications as the only type of treatment and often urge clinicians to try nonpharmacological interventions first.3 A specific type of psychotherapy called cognitive-behavioral therapy has the strongest scientific support as an effective treatment for anxiety but other modalities, including parenting guidance, can be helpful as well. Consequently, a referral to a good psychotherapist is paramount. For many kids, the key to overcoming anxiety is exposure: which means confronting anxiety slowly, with support, and with specific skills.

If there is a traumatic source of the anxiety, addressing that as much as possible is obviously critical and could involve working with the family or school. For some kids, this may involve frightening things they are seeing online or through other media. Finally, some health promotion activities such as exercise or mindfulness can also be quite useful.

Despite the fact that SSRIs are referred to as antidepressants, there is increasing appreciation that these medications are useful for anxiety, perhaps even more so than for mood. While only one medication, duloxetine, has Food and Drug Administration approval to treat anxiety in children as young as 7, there is good evidence to support the use of many of the most common SSRIs in treating clinical anxiety. Buspirone, beta-blockers, and antihistamine medications like hydroxyzine also can have their place in treatment, while benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications are generally best avoided for anxious youth, especially in the primary care setting. A short but helpful medication guide with regard to pediatric anxiety has been published by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.4

Conclusions

Clinical levels of anxiety in children and adolescents are both common and quite treatable, which has prompted new recommendations that primary care clinicians screen for them starting at age 8. While this recommendation may at first seem like yet one more task to fit in, following the guidance can be accomplished with the help of short screening tools and a managed multimodal approach to treatment.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1438-44.

2. Strawn JR. Curr Psychiatry. 2012;11(9):16-21.

3. Walter HJ et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(10):1107-24.

4. Anxiety Disorders: Parents’ Medication Guide Workgroup. “Anxiety disorders: Parents’ medication guide.” Washington D.C.: American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2020.

Recently the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a formal recommendation that adolescents and children as young as 8 should be screened for anxiety.1 The advice was based on a review of the research that concluded that anxiety disorders were common in youth (prevalence around 8%), screening was not overly burdensome or dangerous, and treatments were available and effective.

While pediatricians fully appreciate how common clinically significant anxiety is and its impact on the lives of youth, the reception for the recommendations have been mixed. Some are concerned that it could lead to the overprescribing of medications. Arguably, the biggest pushback, however, relates to the question of what to do when a child screens positive in a time when finding an available child and adolescent psychiatrist or other type of pediatric mental health professional can feel next to impossible. The hope of this article is to fill in some of those gaps.

Screening for anxiety disorders

The recommendations suggest using a rating scale as part of the screen but doesn’t dictate which one. A common instrument that has been employed is the Screen for Child Anxiety and Related Disorders, which is a freely available 41-item instrument that has versions for youth self-report and parent-report. A shorter 7-item rating scale, the General Anxiety Disorder–7, and the even shorter GAD-2 (the first two questions of the GAD-7), are also popular but focus, as the name applies, on general anxiety disorder and not related conditions such as social or separation anxiety that can have some different symptoms. These instruments can be given to patients and families in the waiting room or administered with the help of a nurse, physician, or embedded mental health professional. The recommendations do not include specific guidance on how often the screening should be done but repeated screenings are likely important at some interval.

Confirming the diagnosis

Of course, a screening isn’t a formal diagnosis. The American Academy of Pediatrics has expressed the view that the initial diagnosis and treatment for anxiety disorders is well within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, which means further steps are likely required beyond a referral. Fortunately, going from a positive screen to an initial diagnosis does not have to overly laborious and can focus on reviewing the DSM-5 criteria for key anxiety disorders while also ensuring that there isn’t a nonpsychiatric cause driving the symptoms, such as the often cited but rarely seen pheochromocytoma. More common rule-outs include medication-induced anxiety or substance use, excessive caffeine intake, and cardiac arrhythmias. Assessing for current and past trauma or specific causes of the anxiety such as bullying are also important.

It is important to note that it is the rule rather than the exception that youth with clinical levels of anxiety will frequently endorse a number of criteria that span multiple diagnoses including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and separation anxiety disorder.2 Spending a lot of effort to narrow things down to a single anxiety diagnosis often is unnecessary, as both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments don’t change all that much between individual diagnoses.

Explaining the diagnosis

In general, I’m a strong proponent of trying to explain any behavioral diagnoses that you make to kids in a way that is accurate but nonstigmatizing. When it comes to anxiety, one parallel I often draw is to our immune system, which most youth understand at least in basic terms. Both our immune system and our anxiety networks are natural and important; as a species, we wouldn’t have lasted long without them. Both are built to assess and respond to threats. Problems can arise, however, if the response is too strong relative to the threat or the response is activated when it doesn’t need to be. Treatment is directed not at ridding ourselves of anxiety but at helping regulate it so it works for us and not against us. Spending a few minutes going through a discussion like this can be very helpful, and perhaps more so than some dry summary of DSM-5 criteria.

Starting treatment

It is important to note that best practice recommendations when it comes to the treatment of anxiety disorder in youth do not suggest medications as the only type of treatment and often urge clinicians to try nonpharmacological interventions first.3 A specific type of psychotherapy called cognitive-behavioral therapy has the strongest scientific support as an effective treatment for anxiety but other modalities, including parenting guidance, can be helpful as well. Consequently, a referral to a good psychotherapist is paramount. For many kids, the key to overcoming anxiety is exposure: which means confronting anxiety slowly, with support, and with specific skills.

If there is a traumatic source of the anxiety, addressing that as much as possible is obviously critical and could involve working with the family or school. For some kids, this may involve frightening things they are seeing online or through other media. Finally, some health promotion activities such as exercise or mindfulness can also be quite useful.

Despite the fact that SSRIs are referred to as antidepressants, there is increasing appreciation that these medications are useful for anxiety, perhaps even more so than for mood. While only one medication, duloxetine, has Food and Drug Administration approval to treat anxiety in children as young as 7, there is good evidence to support the use of many of the most common SSRIs in treating clinical anxiety. Buspirone, beta-blockers, and antihistamine medications like hydroxyzine also can have their place in treatment, while benzodiazepines and antipsychotic medications are generally best avoided for anxious youth, especially in the primary care setting. A short but helpful medication guide with regard to pediatric anxiety has been published by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.4

Conclusions

Clinical levels of anxiety in children and adolescents are both common and quite treatable, which has prompted new recommendations that primary care clinicians screen for them starting at age 8. While this recommendation may at first seem like yet one more task to fit in, following the guidance can be accomplished with the help of short screening tools and a managed multimodal approach to treatment.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

References

1. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1438-44.

2. Strawn JR. Curr Psychiatry. 2012;11(9):16-21.

3. Walter HJ et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(10):1107-24.

4. Anxiety Disorders: Parents’ Medication Guide Workgroup. “Anxiety disorders: Parents’ medication guide.” Washington D.C.: American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2020.

Scurvy in psychiatric patients: An easy-to-miss diagnosis

Two years ago, I cared for Ms. L, a woman in her late 40s who had a history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Unable to work and highly distressed throughout the day, Ms. L was admitted to our psychiatric unit due to her functional decompensation and symptom severity.

Ms. L was extremely focused on physical symptoms. She had rigid rules regarding which beauty products she could and could not use (she insisted most soaps gave her a rash, though she did not have any clear documentation of this) as well as the types of food she could and could not eat due to fear of an allergic reaction (skin testing was negative for the foods she claimed were problematic, though this did not change her selective eating habits). By the time she was admitted to our unit, in addition to outpatient mental health, she was being treated by internal medicine, allergy and immunology, and dermatology, with largely equivocal objective findings.

During her psychiatric admission intake, Ms. L mentioned that due to her fear of anaphylaxis, she hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables for at least 2 years. As a result, I ordered testing of her vitamin C level.

Three days following admission, Ms. L requested to be discharged because she said she needed to care for her pet. She reported feeling less anxious, and because the treatment team felt she did not meet the criteria for an involuntary hold, she was discharged. A week later, the results of her vitamin C level came back, indicating a severe deficiency (<0.1 mg/dL; reference range: 0.3 to 2.7 mg/dL). I contacted her outpatient team, and vitamin C supplementation was started immediately.

Notes from Ms. L’s subsequent outpatient mental health visits indicated improvement in her somatic symptoms (less perseveration), although over the next year her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scales were largely unchanged (fluctuating within the range of 11 to 17 and 12 to 17, respectively). One year later, Ms. L stopped taking vitamin C supplements because she was afraid she was becoming allergic to them, though there was no objective evidence to support this belief. Her vitamin C levels were within the normal range at the time and have not been rechecked since then.

Ms. L’s obsession with “healthy eating” led to numerous red herrings for clinicians, as she was anxious about every food. Countertransference and feelings of frustration may have also led clinicians in multiple specialties to miss the diagnosis of scurvy. Vitamin C supplementation did not result in remission of Ms. L’s symptoms, which reflects the complexity and severity of her comorbid psychiatric illnesses. However, a decrease in her perseveration on somatic symptoms afforded increased opportunities to address her other psychiatric diagnoses. Ms. L eventually enrolled in an eating disorders program, which was beneficial to her.

Keep scurvy in the differential Dx

Symptoms of scurvy include malaise; lethargy; anemia; myalgia; bone pain; easy bruising; petechiae and perifollicular hemorrhages (due to capillary fragility); gum disease; mood changes; and depression.1 In later stages, the presentation can progress to edema; jaundice; hemolysis and spontaneous bleeding; neuropathy; fever; convulsions; and death.

1. Léger D. Scurvy: reemergence of nutritional deficiencies. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(10):1403-1406.

2. Velandia B, Centor RM, McConnell V, et al. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1281-1284.

3. Meisel K, Daggubati S, Josephson SA. Scurvy in the 21st century? Vitamin C deficiency presenting to the neurologist. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(6):491-493.

Two years ago, I cared for Ms. L, a woman in her late 40s who had a history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Unable to work and highly distressed throughout the day, Ms. L was admitted to our psychiatric unit due to her functional decompensation and symptom severity.

Ms. L was extremely focused on physical symptoms. She had rigid rules regarding which beauty products she could and could not use (she insisted most soaps gave her a rash, though she did not have any clear documentation of this) as well as the types of food she could and could not eat due to fear of an allergic reaction (skin testing was negative for the foods she claimed were problematic, though this did not change her selective eating habits). By the time she was admitted to our unit, in addition to outpatient mental health, she was being treated by internal medicine, allergy and immunology, and dermatology, with largely equivocal objective findings.

During her psychiatric admission intake, Ms. L mentioned that due to her fear of anaphylaxis, she hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables for at least 2 years. As a result, I ordered testing of her vitamin C level.

Three days following admission, Ms. L requested to be discharged because she said she needed to care for her pet. She reported feeling less anxious, and because the treatment team felt she did not meet the criteria for an involuntary hold, she was discharged. A week later, the results of her vitamin C level came back, indicating a severe deficiency (<0.1 mg/dL; reference range: 0.3 to 2.7 mg/dL). I contacted her outpatient team, and vitamin C supplementation was started immediately.

Notes from Ms. L’s subsequent outpatient mental health visits indicated improvement in her somatic symptoms (less perseveration), although over the next year her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scales were largely unchanged (fluctuating within the range of 11 to 17 and 12 to 17, respectively). One year later, Ms. L stopped taking vitamin C supplements because she was afraid she was becoming allergic to them, though there was no objective evidence to support this belief. Her vitamin C levels were within the normal range at the time and have not been rechecked since then.

Ms. L’s obsession with “healthy eating” led to numerous red herrings for clinicians, as she was anxious about every food. Countertransference and feelings of frustration may have also led clinicians in multiple specialties to miss the diagnosis of scurvy. Vitamin C supplementation did not result in remission of Ms. L’s symptoms, which reflects the complexity and severity of her comorbid psychiatric illnesses. However, a decrease in her perseveration on somatic symptoms afforded increased opportunities to address her other psychiatric diagnoses. Ms. L eventually enrolled in an eating disorders program, which was beneficial to her.

Keep scurvy in the differential Dx

Symptoms of scurvy include malaise; lethargy; anemia; myalgia; bone pain; easy bruising; petechiae and perifollicular hemorrhages (due to capillary fragility); gum disease; mood changes; and depression.1 In later stages, the presentation can progress to edema; jaundice; hemolysis and spontaneous bleeding; neuropathy; fever; convulsions; and death.

Two years ago, I cared for Ms. L, a woman in her late 40s who had a history of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Unable to work and highly distressed throughout the day, Ms. L was admitted to our psychiatric unit due to her functional decompensation and symptom severity.

Ms. L was extremely focused on physical symptoms. She had rigid rules regarding which beauty products she could and could not use (she insisted most soaps gave her a rash, though she did not have any clear documentation of this) as well as the types of food she could and could not eat due to fear of an allergic reaction (skin testing was negative for the foods she claimed were problematic, though this did not change her selective eating habits). By the time she was admitted to our unit, in addition to outpatient mental health, she was being treated by internal medicine, allergy and immunology, and dermatology, with largely equivocal objective findings.

During her psychiatric admission intake, Ms. L mentioned that due to her fear of anaphylaxis, she hadn’t eaten any fruits or vegetables for at least 2 years. As a result, I ordered testing of her vitamin C level.

Three days following admission, Ms. L requested to be discharged because she said she needed to care for her pet. She reported feeling less anxious, and because the treatment team felt she did not meet the criteria for an involuntary hold, she was discharged. A week later, the results of her vitamin C level came back, indicating a severe deficiency (<0.1 mg/dL; reference range: 0.3 to 2.7 mg/dL). I contacted her outpatient team, and vitamin C supplementation was started immediately.

Notes from Ms. L’s subsequent outpatient mental health visits indicated improvement in her somatic symptoms (less perseveration), although over the next year her scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scales were largely unchanged (fluctuating within the range of 11 to 17 and 12 to 17, respectively). One year later, Ms. L stopped taking vitamin C supplements because she was afraid she was becoming allergic to them, though there was no objective evidence to support this belief. Her vitamin C levels were within the normal range at the time and have not been rechecked since then.

Ms. L’s obsession with “healthy eating” led to numerous red herrings for clinicians, as she was anxious about every food. Countertransference and feelings of frustration may have also led clinicians in multiple specialties to miss the diagnosis of scurvy. Vitamin C supplementation did not result in remission of Ms. L’s symptoms, which reflects the complexity and severity of her comorbid psychiatric illnesses. However, a decrease in her perseveration on somatic symptoms afforded increased opportunities to address her other psychiatric diagnoses. Ms. L eventually enrolled in an eating disorders program, which was beneficial to her.

Keep scurvy in the differential Dx

Symptoms of scurvy include malaise; lethargy; anemia; myalgia; bone pain; easy bruising; petechiae and perifollicular hemorrhages (due to capillary fragility); gum disease; mood changes; and depression.1 In later stages, the presentation can progress to edema; jaundice; hemolysis and spontaneous bleeding; neuropathy; fever; convulsions; and death.

1. Léger D. Scurvy: reemergence of nutritional deficiencies. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(10):1403-1406.

2. Velandia B, Centor RM, McConnell V, et al. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1281-1284.

3. Meisel K, Daggubati S, Josephson SA. Scurvy in the 21st century? Vitamin C deficiency presenting to the neurologist. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(6):491-493.

1. Léger D. Scurvy: reemergence of nutritional deficiencies. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(10):1403-1406.

2. Velandia B, Centor RM, McConnell V, et al. Scurvy is still present in developed countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1281-1284.

3. Meisel K, Daggubati S, Josephson SA. Scurvy in the 21st century? Vitamin C deficiency presenting to the neurologist. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(6):491-493.

The importance of connection and community

You only are free when you realize you belong no place – you belong every place – no place at all. The price is high. The reward is great. ~ Maya Angelou

At 8 o’clock, every weekday morning, for years and years now, two friends appear in my kitchen for coffee, and so one identity I carry includes being part of the “coffee ladies.” While this is one of the smaller and more intimate groups to which I belong, I am also a member (“distinguished,” no less) of a slightly larger group: the American Psychiatric Association, and being part of both groups is meaningful to me in more ways than I can describe.

When I think back over the years, I – like most people – have belonged to many people and places, either officially or unofficially. It is these connections that define us, fill our time, give us meaning and purpose, and anchor us. We belong to our families and friends, but we also belong to our professional and community groups, our institutions – whether they are hospitals, schools, religious centers, country clubs, or charitable organizations – as well as interest and advocacy groups. And finally, we belong to our coworkers and to our patients, and they to us, especially if we see the same people over time. Being a psychiatrist can be a solitary career, and it can take a little effort to be a part of larger worlds, especially for those who find solace in more individual activities.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve noticed that I belong to fewer of these groups. I’m no longer a little league or field hockey mom, nor a member of the neighborhood babysitting co-op, and I’ve exhausted the gamut of council and leadership positions in my APA district branch. I’ve joined organizations only to pay the membership fee, and then never gone to their meetings or events. The pandemic has accounted for some of this: I still belong to my book club, but I often read the book and don’t go to the Zoom meetings as I miss the real-life aspect of getting together. Being boxed on a screen is not the same as the one-on-one conversations before the formal book discussion. And while I still carry a host of identities, I imagine it is not unusual to belong to fewer organizations as time passes. It’s not all bad, there is something good to be said for living life at a less frenetic pace as fewer entities lay claim to my time.

In psychiatry, our patients span the range of human experience: Some are very engaged with their worlds, while others struggle to make even the most basic of connections. Their lives may seem disconnected – empty, even – and I find myself encouraging people to reach out, to find activities that will ease their loneliness and integrate a feeling of belonging in a way that adds meaning and purpose. For some people, this may be as simple as asking a friend to have lunch, but even that can be an overwhelming obstacle for someone who is depressed, or for someone who has no friends.

Patients may counter my suggestions with a host of reasons as to why they can’t connect. Perhaps their friend is too busy with work or his family, the lunch would cost too much, there’s no transportation, or no restaurant that could meet their dietary needs. Or perhaps they are just too fearful of being rejected.

Psychiatric disorders, by their nature, can be very isolating. Depressed and anxious people often find it a struggle just to get through their days, adding new people and activities is not something that brings joy. For people suffering with psychosis, their internal realities are often all-consuming and there may be no room for accommodating others. And finally, what I hear over and over, is that people are afraid of what others might think of them, and this fear is paralyzing. I try to suggest that we never really know or control what others think of us, but obviously, this does not reassure most patients as they are also bewildered by their irrational fear. To go to an event unaccompanied, or even to a party to which they have been invited, is a hurdle they won’t (or can’t) attempt.

The pandemic, with its initial months of shutdown, and then with years of fear of illness, has created new ways of connecting. Our “Zoom” world can be very convenient – in many ways it has opened up aspects of learning and connection for people who are short on time,or struggle with transportation. In the comfort of our living rooms, in pajamas and slippers, we can take classes, join clubs, attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, go to conferences or religious services, and be part of any number of organizations without flying or searching for parking. I love that, with 1 hour and a single click, I can now attend my department’s weekly Grand Rounds. But for many who struggle with using technology, or who don’t feel the same benefits from online encounters, the pandemic has been an isolating and lonely time.