User login

Healthy diet, less news helped prevent anxiety, depression during COVID

VIENNA –

Results from a longitudinal Spanish survey study of more than 1,000 adults showed that being outside, relaxing, participating in physical activities, and drinking plenty of water were also beneficial. However, social contact with friends and relatives, following a routine, and pursuing hobbies had no significant impact.

“This was a little surprising,” lead author Joaquim Radua, MD, PhD, August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, said in a release.

“Like many people, we had assumed that personal contact would play a bigger part in avoiding anxiety and depression during stressful times,” he added.

However, Dr. Radua said that because the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “people who socialized may also have been anxious about getting infected.”

Consequently, “it may be that this specific behavior cannot be extrapolated to other times, when there is no pandemic,” he said.

The findings were presented at the 35th European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) Congress.

Correlational versus longitudinal studies

Dr. Radua emphasized that individuals “should socialize,” of course.

“We think it’s important that people continue to follow what works for them and that if you enjoy seeing friends or following a hobby, you continue to do so,” he said.

“Our work was centered on COVID, but we now need to see if these factors apply to other stressful circumstances. These simple behaviors may prevent anxiety and depression, and prevention is better than cure,” he added.

The researchers note that, in “times of uncertainty” such as the COVID-19 pandemic, many individuals experience increases in both anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Although a range of behaviors are recommended to help people cope, the investigators add that some of the recommendations are based on correlational studies.

Indeed, the researchers previously identified a correlation between following a healthy/balanced diet, among other measures, and lower anxiety and depressive symptoms during the pandemic.

However, it is unclear from cross-sectional studies whether the behavior alters the symptoms, in which case the behavior could be considered “helpful,” or conversely whether the symptoms alter an individual’s behavior, in which case the behaviors “may be useless,” the investigators note.

The investigative team therefore set out to provide more robust evidence for making recommendations and conducted a prospective longitudinal study.

They recruited 1,049 adults online via social networks, matching them to the regional, age and sex, and urbanicity distribution of the overall Spanish population.

Every 2 weeks for 12 months, the researchers administered the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9, and a two-item ecological momentary assessment to minimize recall bias, among other measures. They also asked about 10 self-report coping behaviors.

Significant coping behaviors

The study was completed by 942 individuals, indicating a retention of 90%.

Among both completers and non-completers there was an over-representation of individuals aged 18-34 years and women, compared with the general population, and fewer participants aged at least 65 years.

Pre-recruitment, the mean baseline GAD-7 score among completers was 7.4, falling to around 5.5 at the time of the first questionnaire. Scores on the PHQ-9 were 7.6 and 5.6, respectively.

Performing population-weighted autoregressive moving average models to analyze the relationship between the current frequency of the coping behaviors and future changes in anxiety and depressive symptoms, the investigators found that the greatest effect was from following a healthy, balanced diet, with an impact size of 0.95.

This was followed by avoiding too much stressful news (impact size, 0.91), staying outdoors or looking outside (0.40), doing relaxing activities (0.33), participating in physical exercise (0.32), and drinking water to hydrate (0.25).

Overall, these coping behaviors were associated with a significant reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms (all, P < .001).

On the other hand, there was no impact on future symptoms from socializing with friends and relatives, whether or not they lived in the same household. There was also no effect from following a routine, pursuing hobbies, or performing home tasks.

The researchers note that similar results were obtained when excluding participants with hazardous alcohol consumption, defined as a score on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test of 8 or higher.

However, they point out that despite its prospective design and large cohort, the study was not interventional. Therefore, they “cannot rule out the possibility that decreasing the frequency of a behavior is an early sign of some mechanism that later leads to increased anxiety and depression symptoms.”

Nevertheless, they believe that possibility “seems unlikely.”

Reflective of a unique time?

Commenting on the findings, Catherine Harmer, PhD, director of the Psychopharmacology and Emotional Research Lab, department of psychiatry, University of Oxford (England), said in the release this was an “interesting study” that “provides some important insights as to which behaviors may protect our mental health during times of significant stress.”

She said the finding that social contact was not beneficial was “surprising” but may reflect the fact that, during the pandemic, it was “stressful even to have those social contacts, even if we managed to meet a friend outside.”

The results of the study may therefore be “reflective of the unique experience” of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Dr. Harmer, who was not involved with the research.

“I wouldn’t think that reading too much news would generally be something that has a negative impact on depression and anxiety, but I think it was very much at the time,” she said.

With the pandemic overwhelming one country after another, “the more you read about it, the more frightening it was,” she added, noting that it is “easy to forget how frightened we were at the beginning.”

Dr. Harmer noted that “it would be interesting” if the study was repeated and the same factors came out – or if they were unique to that time.

This would be “useful to know, as these times may come again. And the more information we have to cope with a pandemic, the better,” she concluded.

The research was supported by the AXA Research Fund via an AXA Award granted to Dr. Radua from the call for projects “mitigating risk in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.” The investigators and Dr. Harmer report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA –

Results from a longitudinal Spanish survey study of more than 1,000 adults showed that being outside, relaxing, participating in physical activities, and drinking plenty of water were also beneficial. However, social contact with friends and relatives, following a routine, and pursuing hobbies had no significant impact.

“This was a little surprising,” lead author Joaquim Radua, MD, PhD, August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, said in a release.

“Like many people, we had assumed that personal contact would play a bigger part in avoiding anxiety and depression during stressful times,” he added.

However, Dr. Radua said that because the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “people who socialized may also have been anxious about getting infected.”

Consequently, “it may be that this specific behavior cannot be extrapolated to other times, when there is no pandemic,” he said.

The findings were presented at the 35th European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) Congress.

Correlational versus longitudinal studies

Dr. Radua emphasized that individuals “should socialize,” of course.

“We think it’s important that people continue to follow what works for them and that if you enjoy seeing friends or following a hobby, you continue to do so,” he said.

“Our work was centered on COVID, but we now need to see if these factors apply to other stressful circumstances. These simple behaviors may prevent anxiety and depression, and prevention is better than cure,” he added.

The researchers note that, in “times of uncertainty” such as the COVID-19 pandemic, many individuals experience increases in both anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Although a range of behaviors are recommended to help people cope, the investigators add that some of the recommendations are based on correlational studies.

Indeed, the researchers previously identified a correlation between following a healthy/balanced diet, among other measures, and lower anxiety and depressive symptoms during the pandemic.

However, it is unclear from cross-sectional studies whether the behavior alters the symptoms, in which case the behavior could be considered “helpful,” or conversely whether the symptoms alter an individual’s behavior, in which case the behaviors “may be useless,” the investigators note.

The investigative team therefore set out to provide more robust evidence for making recommendations and conducted a prospective longitudinal study.

They recruited 1,049 adults online via social networks, matching them to the regional, age and sex, and urbanicity distribution of the overall Spanish population.

Every 2 weeks for 12 months, the researchers administered the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9, and a two-item ecological momentary assessment to minimize recall bias, among other measures. They also asked about 10 self-report coping behaviors.

Significant coping behaviors

The study was completed by 942 individuals, indicating a retention of 90%.

Among both completers and non-completers there was an over-representation of individuals aged 18-34 years and women, compared with the general population, and fewer participants aged at least 65 years.

Pre-recruitment, the mean baseline GAD-7 score among completers was 7.4, falling to around 5.5 at the time of the first questionnaire. Scores on the PHQ-9 were 7.6 and 5.6, respectively.

Performing population-weighted autoregressive moving average models to analyze the relationship between the current frequency of the coping behaviors and future changes in anxiety and depressive symptoms, the investigators found that the greatest effect was from following a healthy, balanced diet, with an impact size of 0.95.

This was followed by avoiding too much stressful news (impact size, 0.91), staying outdoors or looking outside (0.40), doing relaxing activities (0.33), participating in physical exercise (0.32), and drinking water to hydrate (0.25).

Overall, these coping behaviors were associated with a significant reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms (all, P < .001).

On the other hand, there was no impact on future symptoms from socializing with friends and relatives, whether or not they lived in the same household. There was also no effect from following a routine, pursuing hobbies, or performing home tasks.

The researchers note that similar results were obtained when excluding participants with hazardous alcohol consumption, defined as a score on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test of 8 or higher.

However, they point out that despite its prospective design and large cohort, the study was not interventional. Therefore, they “cannot rule out the possibility that decreasing the frequency of a behavior is an early sign of some mechanism that later leads to increased anxiety and depression symptoms.”

Nevertheless, they believe that possibility “seems unlikely.”

Reflective of a unique time?

Commenting on the findings, Catherine Harmer, PhD, director of the Psychopharmacology and Emotional Research Lab, department of psychiatry, University of Oxford (England), said in the release this was an “interesting study” that “provides some important insights as to which behaviors may protect our mental health during times of significant stress.”

She said the finding that social contact was not beneficial was “surprising” but may reflect the fact that, during the pandemic, it was “stressful even to have those social contacts, even if we managed to meet a friend outside.”

The results of the study may therefore be “reflective of the unique experience” of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Dr. Harmer, who was not involved with the research.

“I wouldn’t think that reading too much news would generally be something that has a negative impact on depression and anxiety, but I think it was very much at the time,” she said.

With the pandemic overwhelming one country after another, “the more you read about it, the more frightening it was,” she added, noting that it is “easy to forget how frightened we were at the beginning.”

Dr. Harmer noted that “it would be interesting” if the study was repeated and the same factors came out – or if they were unique to that time.

This would be “useful to know, as these times may come again. And the more information we have to cope with a pandemic, the better,” she concluded.

The research was supported by the AXA Research Fund via an AXA Award granted to Dr. Radua from the call for projects “mitigating risk in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.” The investigators and Dr. Harmer report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA –

Results from a longitudinal Spanish survey study of more than 1,000 adults showed that being outside, relaxing, participating in physical activities, and drinking plenty of water were also beneficial. However, social contact with friends and relatives, following a routine, and pursuing hobbies had no significant impact.

“This was a little surprising,” lead author Joaquim Radua, MD, PhD, August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, said in a release.

“Like many people, we had assumed that personal contact would play a bigger part in avoiding anxiety and depression during stressful times,” he added.

However, Dr. Radua said that because the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, “people who socialized may also have been anxious about getting infected.”

Consequently, “it may be that this specific behavior cannot be extrapolated to other times, when there is no pandemic,” he said.

The findings were presented at the 35th European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) Congress.

Correlational versus longitudinal studies

Dr. Radua emphasized that individuals “should socialize,” of course.

“We think it’s important that people continue to follow what works for them and that if you enjoy seeing friends or following a hobby, you continue to do so,” he said.

“Our work was centered on COVID, but we now need to see if these factors apply to other stressful circumstances. These simple behaviors may prevent anxiety and depression, and prevention is better than cure,” he added.

The researchers note that, in “times of uncertainty” such as the COVID-19 pandemic, many individuals experience increases in both anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Although a range of behaviors are recommended to help people cope, the investigators add that some of the recommendations are based on correlational studies.

Indeed, the researchers previously identified a correlation between following a healthy/balanced diet, among other measures, and lower anxiety and depressive symptoms during the pandemic.

However, it is unclear from cross-sectional studies whether the behavior alters the symptoms, in which case the behavior could be considered “helpful,” or conversely whether the symptoms alter an individual’s behavior, in which case the behaviors “may be useless,” the investigators note.

The investigative team therefore set out to provide more robust evidence for making recommendations and conducted a prospective longitudinal study.

They recruited 1,049 adults online via social networks, matching them to the regional, age and sex, and urbanicity distribution of the overall Spanish population.

Every 2 weeks for 12 months, the researchers administered the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD)-7, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9, and a two-item ecological momentary assessment to minimize recall bias, among other measures. They also asked about 10 self-report coping behaviors.

Significant coping behaviors

The study was completed by 942 individuals, indicating a retention of 90%.

Among both completers and non-completers there was an over-representation of individuals aged 18-34 years and women, compared with the general population, and fewer participants aged at least 65 years.

Pre-recruitment, the mean baseline GAD-7 score among completers was 7.4, falling to around 5.5 at the time of the first questionnaire. Scores on the PHQ-9 were 7.6 and 5.6, respectively.

Performing population-weighted autoregressive moving average models to analyze the relationship between the current frequency of the coping behaviors and future changes in anxiety and depressive symptoms, the investigators found that the greatest effect was from following a healthy, balanced diet, with an impact size of 0.95.

This was followed by avoiding too much stressful news (impact size, 0.91), staying outdoors or looking outside (0.40), doing relaxing activities (0.33), participating in physical exercise (0.32), and drinking water to hydrate (0.25).

Overall, these coping behaviors were associated with a significant reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms (all, P < .001).

On the other hand, there was no impact on future symptoms from socializing with friends and relatives, whether or not they lived in the same household. There was also no effect from following a routine, pursuing hobbies, or performing home tasks.

The researchers note that similar results were obtained when excluding participants with hazardous alcohol consumption, defined as a score on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test of 8 or higher.

However, they point out that despite its prospective design and large cohort, the study was not interventional. Therefore, they “cannot rule out the possibility that decreasing the frequency of a behavior is an early sign of some mechanism that later leads to increased anxiety and depression symptoms.”

Nevertheless, they believe that possibility “seems unlikely.”

Reflective of a unique time?

Commenting on the findings, Catherine Harmer, PhD, director of the Psychopharmacology and Emotional Research Lab, department of psychiatry, University of Oxford (England), said in the release this was an “interesting study” that “provides some important insights as to which behaviors may protect our mental health during times of significant stress.”

She said the finding that social contact was not beneficial was “surprising” but may reflect the fact that, during the pandemic, it was “stressful even to have those social contacts, even if we managed to meet a friend outside.”

The results of the study may therefore be “reflective of the unique experience” of the COVID-19 pandemic, said Dr. Harmer, who was not involved with the research.

“I wouldn’t think that reading too much news would generally be something that has a negative impact on depression and anxiety, but I think it was very much at the time,” she said.

With the pandemic overwhelming one country after another, “the more you read about it, the more frightening it was,” she added, noting that it is “easy to forget how frightened we were at the beginning.”

Dr. Harmer noted that “it would be interesting” if the study was repeated and the same factors came out – or if they were unique to that time.

This would be “useful to know, as these times may come again. And the more information we have to cope with a pandemic, the better,” she concluded.

The research was supported by the AXA Research Fund via an AXA Award granted to Dr. Radua from the call for projects “mitigating risk in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.” The investigators and Dr. Harmer report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ECNP 2022

Preexisting mental illness symptoms spiked during pandemic

“Those with preexisting mental health conditions may be particularly vulnerable to these effects because they are more susceptible to experiencing high levels of stress during a crisis and are more likely to experience isolation/despair during confinement compared to the general population,” wrote Danna Ramirez of The Menninger Clinic, Houston, and colleagues.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research , the investigators compared data from 142 adolescents aged 12-17 years and 470 adults aged 18-79 years who were admitted to an inpatient psychiatric hospital in Houston. Of these, 65 adolescents and 235 adults were admitted before the pandemic, and 77 adolescents and 235 adults were admitted during the pandemic.

Clinical outcomes were scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A), the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale–Short Form (DERS-SF), the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale (WHODAS), the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (WHOASSIST), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Disturbing Dream and Nightmare Severity Index (DDNSI), and the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised (SBQ-R).

Overall, adults admitted during the pandemic had significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression, emotional dysregulation, and disability (P < .001 for all) as well as nightmares (P = .013) compared to those admitted prior to the pandemic.

Among adolescents, measures of anxiety, depression, and sleep quality were significantly higher at admission during the pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic (P = .005, P = .005, and P = .011, respectively)

Reasons for the increase in symptom severity remain unclear, but include the possibility that individuals with preexisting mental illness simply became more ill; or that individuals with symptoms delayed hospital admission out of fear of exposure to COVID-19, which resulted in more severe symptoms at admission, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the primarily White population and the reliance on self-reports, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the lack of differentiation between patients who may have had COVID-19 before hospitalization and those who did not, so the researchers could not determine whether the virus itself played a biological role in symptom severity.

However, the results support data from previous studies and identify increased psychiatry symptom severity for patients admitted for inpatient psychiatry care during the pandemic, they said. Although resources are scarce, the findings emphasize that mental health needs, especially for those with preexisting conditions, should not be overlooked, and continuity and expansion of access to mental health care for all should be prioritized, they concluded.

The study was supported by The Menninger Clinic and The Menninger Clinic Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Those with preexisting mental health conditions may be particularly vulnerable to these effects because they are more susceptible to experiencing high levels of stress during a crisis and are more likely to experience isolation/despair during confinement compared to the general population,” wrote Danna Ramirez of The Menninger Clinic, Houston, and colleagues.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research , the investigators compared data from 142 adolescents aged 12-17 years and 470 adults aged 18-79 years who were admitted to an inpatient psychiatric hospital in Houston. Of these, 65 adolescents and 235 adults were admitted before the pandemic, and 77 adolescents and 235 adults were admitted during the pandemic.

Clinical outcomes were scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A), the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale–Short Form (DERS-SF), the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale (WHODAS), the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (WHOASSIST), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Disturbing Dream and Nightmare Severity Index (DDNSI), and the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised (SBQ-R).

Overall, adults admitted during the pandemic had significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression, emotional dysregulation, and disability (P < .001 for all) as well as nightmares (P = .013) compared to those admitted prior to the pandemic.

Among adolescents, measures of anxiety, depression, and sleep quality were significantly higher at admission during the pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic (P = .005, P = .005, and P = .011, respectively)

Reasons for the increase in symptom severity remain unclear, but include the possibility that individuals with preexisting mental illness simply became more ill; or that individuals with symptoms delayed hospital admission out of fear of exposure to COVID-19, which resulted in more severe symptoms at admission, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the primarily White population and the reliance on self-reports, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the lack of differentiation between patients who may have had COVID-19 before hospitalization and those who did not, so the researchers could not determine whether the virus itself played a biological role in symptom severity.

However, the results support data from previous studies and identify increased psychiatry symptom severity for patients admitted for inpatient psychiatry care during the pandemic, they said. Although resources are scarce, the findings emphasize that mental health needs, especially for those with preexisting conditions, should not be overlooked, and continuity and expansion of access to mental health care for all should be prioritized, they concluded.

The study was supported by The Menninger Clinic and The Menninger Clinic Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Those with preexisting mental health conditions may be particularly vulnerable to these effects because they are more susceptible to experiencing high levels of stress during a crisis and are more likely to experience isolation/despair during confinement compared to the general population,” wrote Danna Ramirez of The Menninger Clinic, Houston, and colleagues.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research , the investigators compared data from 142 adolescents aged 12-17 years and 470 adults aged 18-79 years who were admitted to an inpatient psychiatric hospital in Houston. Of these, 65 adolescents and 235 adults were admitted before the pandemic, and 77 adolescents and 235 adults were admitted during the pandemic.

Clinical outcomes were scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents (PHQ-A), the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale–Short Form (DERS-SF), the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale (WHODAS), the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (WHOASSIST), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Disturbing Dream and Nightmare Severity Index (DDNSI), and the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised (SBQ-R).

Overall, adults admitted during the pandemic had significantly higher levels of anxiety, depression, emotional dysregulation, and disability (P < .001 for all) as well as nightmares (P = .013) compared to those admitted prior to the pandemic.

Among adolescents, measures of anxiety, depression, and sleep quality were significantly higher at admission during the pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic (P = .005, P = .005, and P = .011, respectively)

Reasons for the increase in symptom severity remain unclear, but include the possibility that individuals with preexisting mental illness simply became more ill; or that individuals with symptoms delayed hospital admission out of fear of exposure to COVID-19, which resulted in more severe symptoms at admission, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the primarily White population and the reliance on self-reports, the researchers noted. Another limitation was the lack of differentiation between patients who may have had COVID-19 before hospitalization and those who did not, so the researchers could not determine whether the virus itself played a biological role in symptom severity.

However, the results support data from previous studies and identify increased psychiatry symptom severity for patients admitted for inpatient psychiatry care during the pandemic, they said. Although resources are scarce, the findings emphasize that mental health needs, especially for those with preexisting conditions, should not be overlooked, and continuity and expansion of access to mental health care for all should be prioritized, they concluded.

The study was supported by The Menninger Clinic and The Menninger Clinic Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PSYCHIATRY RESEARCH

E-health program improves perinatal depression

Patients with perinatal depression who used a specialized online tool showed improvement in symptoms, compared with controls who received routine care, based on data from 191 individuals.

Although perinatal depression affects approximately 17% of pregnant women and 13% of postpartum women, the condition is often underrecognized and undertreated, Brian Danaher, PhD, of Influents Innovations, Eugene, Ore., and colleagues wrote. Meta-analyses have shown that e-health interventions based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can improve depression in general and perinatal depression in particular.

An e-health program known as the MomMoodBooster has demonstrated effectiveness at reducing postpartum depression, and the researchers evaluated the effectiveness of a perinatal version.

In a study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers randomized 95 pregnant women and 96 postpartum women who met screening criteria for depression to routine care for perinatal depression, which included a 24/7 crisis hotline and a referral network or PDP plus a version of the MomMoodBooster with a perinatal depression component (MMB2). Participants were aged 18 and older, with no active suicidal ideation. The average age was 32 years; 84% were non-Hispanic, 67% were White, and 94% were married or in a long-term relationship. During the 12 weeks, each of six sessions became accessible online in sequence.

The primary endpoint was the change in outcomes at 12 weeks after the start of the program, with depressive symptom severity measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Anxiety was assessed as a secondary outcome by using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was used to evaluate clinical significance, and was defined as a reduction in PHQ-9 of at least 5 points from baseline.

After controlling for perinatal status at baseline and assessment time, the MMB2 group had significantly greater decreases in depression severity and stress compared with the routine care group. In addition, based on MCID, significantly more women in the MMB2 group showed improvements in depression, compared with the routine care group (43% vs. 26%; odds ratio, 2.12; P = .015).

A total of 88 of the 89 women in the MMB2 group accessed the sessions, and approximately half (49%) viewed all six sessions.

Of the women who used the MMB2 program, 96% said that it was easy to use, 93% said they would recommend it, and 83% said it was helpful to them.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of long-term follow-up data and inability to determine the durability of the treatment effects, the researchers noted. Another key limitation is the demographics of the study population (slightly older and a greater proportion of White individuals than the national average), which may not be representative of all perinatal women in the United States.

However, the results are consistent with findings from previous studies, including meta-analyses of CBT-based programs, the researchers wrote.

“When used in a largely self-directed approach, MMB2 could fill the gap when in-person treatment options are limited as well as for women whose circumstances (COVID) and/or concerns (stigma, costs) reduce the acceptability of in-person help,” they said. Use of e-health programs such as MMB2 could increase the scope of treatment for perinatal depression.

Expanding e-health options may improve outcomes and reduce disparities

Perinatal and postpartum depression is one of the most common conditions affecting pregnancy, Lisette D. Tanner, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Depression can have serious consequences for both maternal and neonatal well-being, including preterm birth, low birth weight, and poor bonding, as well as delayed emotional and cognitive development of the newborn.

“While clinicians are encouraged to screen patients during and after pregnancy for signs and symptoms of depression, once identified, the availability of effective treatment is limited. Access to mental health resources is a long-standing disparity in medicine, and therefore research investigating readily available e-health treatment strategies is critically important,” said Dr. Tanner, who was not involved in the study.

In the current study, “I was surprised by the number of patients who saw a clinically significant improvement in depression scores in such a short period of time. An average of only 20 days elapsed between baseline and post-test scores and almost 43% of patients showed improvement. Mental health interventions typically take longer to demonstrate an effect, both medication and talk therapies,” she said.

“The largest barrier to adoption of any e-health modality into clinical practice is often the cost of implementation and maintaining infrastructure,” said Dr. Tanner. “A cost-effectiveness analysis of this intervention would be helpful to better delineate the value of such of program in comparison to more traditional treatments.”

More research is needed on the effectiveness of the intervention for specific populations, such as groups with lower socioeconomic status and patients with chronic mood disorders, Dr. Tanner said. “Additionally, introducing the program in locations with limited access to mental health resources would support more widespread implementation.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Tanner had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Patients with perinatal depression who used a specialized online tool showed improvement in symptoms, compared with controls who received routine care, based on data from 191 individuals.

Although perinatal depression affects approximately 17% of pregnant women and 13% of postpartum women, the condition is often underrecognized and undertreated, Brian Danaher, PhD, of Influents Innovations, Eugene, Ore., and colleagues wrote. Meta-analyses have shown that e-health interventions based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can improve depression in general and perinatal depression in particular.

An e-health program known as the MomMoodBooster has demonstrated effectiveness at reducing postpartum depression, and the researchers evaluated the effectiveness of a perinatal version.

In a study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers randomized 95 pregnant women and 96 postpartum women who met screening criteria for depression to routine care for perinatal depression, which included a 24/7 crisis hotline and a referral network or PDP plus a version of the MomMoodBooster with a perinatal depression component (MMB2). Participants were aged 18 and older, with no active suicidal ideation. The average age was 32 years; 84% were non-Hispanic, 67% were White, and 94% were married or in a long-term relationship. During the 12 weeks, each of six sessions became accessible online in sequence.

The primary endpoint was the change in outcomes at 12 weeks after the start of the program, with depressive symptom severity measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Anxiety was assessed as a secondary outcome by using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was used to evaluate clinical significance, and was defined as a reduction in PHQ-9 of at least 5 points from baseline.

After controlling for perinatal status at baseline and assessment time, the MMB2 group had significantly greater decreases in depression severity and stress compared with the routine care group. In addition, based on MCID, significantly more women in the MMB2 group showed improvements in depression, compared with the routine care group (43% vs. 26%; odds ratio, 2.12; P = .015).

A total of 88 of the 89 women in the MMB2 group accessed the sessions, and approximately half (49%) viewed all six sessions.

Of the women who used the MMB2 program, 96% said that it was easy to use, 93% said they would recommend it, and 83% said it was helpful to them.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of long-term follow-up data and inability to determine the durability of the treatment effects, the researchers noted. Another key limitation is the demographics of the study population (slightly older and a greater proportion of White individuals than the national average), which may not be representative of all perinatal women in the United States.

However, the results are consistent with findings from previous studies, including meta-analyses of CBT-based programs, the researchers wrote.

“When used in a largely self-directed approach, MMB2 could fill the gap when in-person treatment options are limited as well as for women whose circumstances (COVID) and/or concerns (stigma, costs) reduce the acceptability of in-person help,” they said. Use of e-health programs such as MMB2 could increase the scope of treatment for perinatal depression.

Expanding e-health options may improve outcomes and reduce disparities

Perinatal and postpartum depression is one of the most common conditions affecting pregnancy, Lisette D. Tanner, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Depression can have serious consequences for both maternal and neonatal well-being, including preterm birth, low birth weight, and poor bonding, as well as delayed emotional and cognitive development of the newborn.

“While clinicians are encouraged to screen patients during and after pregnancy for signs and symptoms of depression, once identified, the availability of effective treatment is limited. Access to mental health resources is a long-standing disparity in medicine, and therefore research investigating readily available e-health treatment strategies is critically important,” said Dr. Tanner, who was not involved in the study.

In the current study, “I was surprised by the number of patients who saw a clinically significant improvement in depression scores in such a short period of time. An average of only 20 days elapsed between baseline and post-test scores and almost 43% of patients showed improvement. Mental health interventions typically take longer to demonstrate an effect, both medication and talk therapies,” she said.

“The largest barrier to adoption of any e-health modality into clinical practice is often the cost of implementation and maintaining infrastructure,” said Dr. Tanner. “A cost-effectiveness analysis of this intervention would be helpful to better delineate the value of such of program in comparison to more traditional treatments.”

More research is needed on the effectiveness of the intervention for specific populations, such as groups with lower socioeconomic status and patients with chronic mood disorders, Dr. Tanner said. “Additionally, introducing the program in locations with limited access to mental health resources would support more widespread implementation.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Tanner had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Patients with perinatal depression who used a specialized online tool showed improvement in symptoms, compared with controls who received routine care, based on data from 191 individuals.

Although perinatal depression affects approximately 17% of pregnant women and 13% of postpartum women, the condition is often underrecognized and undertreated, Brian Danaher, PhD, of Influents Innovations, Eugene, Ore., and colleagues wrote. Meta-analyses have shown that e-health interventions based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can improve depression in general and perinatal depression in particular.

An e-health program known as the MomMoodBooster has demonstrated effectiveness at reducing postpartum depression, and the researchers evaluated the effectiveness of a perinatal version.

In a study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers randomized 95 pregnant women and 96 postpartum women who met screening criteria for depression to routine care for perinatal depression, which included a 24/7 crisis hotline and a referral network or PDP plus a version of the MomMoodBooster with a perinatal depression component (MMB2). Participants were aged 18 and older, with no active suicidal ideation. The average age was 32 years; 84% were non-Hispanic, 67% were White, and 94% were married or in a long-term relationship. During the 12 weeks, each of six sessions became accessible online in sequence.

The primary endpoint was the change in outcomes at 12 weeks after the start of the program, with depressive symptom severity measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Anxiety was assessed as a secondary outcome by using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was used to evaluate clinical significance, and was defined as a reduction in PHQ-9 of at least 5 points from baseline.

After controlling for perinatal status at baseline and assessment time, the MMB2 group had significantly greater decreases in depression severity and stress compared with the routine care group. In addition, based on MCID, significantly more women in the MMB2 group showed improvements in depression, compared with the routine care group (43% vs. 26%; odds ratio, 2.12; P = .015).

A total of 88 of the 89 women in the MMB2 group accessed the sessions, and approximately half (49%) viewed all six sessions.

Of the women who used the MMB2 program, 96% said that it was easy to use, 93% said they would recommend it, and 83% said it was helpful to them.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of long-term follow-up data and inability to determine the durability of the treatment effects, the researchers noted. Another key limitation is the demographics of the study population (slightly older and a greater proportion of White individuals than the national average), which may not be representative of all perinatal women in the United States.

However, the results are consistent with findings from previous studies, including meta-analyses of CBT-based programs, the researchers wrote.

“When used in a largely self-directed approach, MMB2 could fill the gap when in-person treatment options are limited as well as for women whose circumstances (COVID) and/or concerns (stigma, costs) reduce the acceptability of in-person help,” they said. Use of e-health programs such as MMB2 could increase the scope of treatment for perinatal depression.

Expanding e-health options may improve outcomes and reduce disparities

Perinatal and postpartum depression is one of the most common conditions affecting pregnancy, Lisette D. Tanner, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview. “Depression can have serious consequences for both maternal and neonatal well-being, including preterm birth, low birth weight, and poor bonding, as well as delayed emotional and cognitive development of the newborn.

“While clinicians are encouraged to screen patients during and after pregnancy for signs and symptoms of depression, once identified, the availability of effective treatment is limited. Access to mental health resources is a long-standing disparity in medicine, and therefore research investigating readily available e-health treatment strategies is critically important,” said Dr. Tanner, who was not involved in the study.

In the current study, “I was surprised by the number of patients who saw a clinically significant improvement in depression scores in such a short period of time. An average of only 20 days elapsed between baseline and post-test scores and almost 43% of patients showed improvement. Mental health interventions typically take longer to demonstrate an effect, both medication and talk therapies,” she said.

“The largest barrier to adoption of any e-health modality into clinical practice is often the cost of implementation and maintaining infrastructure,” said Dr. Tanner. “A cost-effectiveness analysis of this intervention would be helpful to better delineate the value of such of program in comparison to more traditional treatments.”

More research is needed on the effectiveness of the intervention for specific populations, such as groups with lower socioeconomic status and patients with chronic mood disorders, Dr. Tanner said. “Additionally, introducing the program in locations with limited access to mental health resources would support more widespread implementation.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Tanner had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Keep menstrual cramps away the dietary prevention way

Foods for thought: Menstrual cramp prevention

For those who menstruate, it’s typical for that time of the month to bring cravings for things that may give a serotonin boost that eases the rise in stress hormones. Chocolate and other foods high in sugar fall into that category, but they could actually be adding to the problem.

About 90% of adolescent girls have menstrual pain, and it’s the leading cause of school absences for the demographic. Muscle relaxers and PMS pills are usually the recommended solution to alleviating menstrual cramps, but what if the patient doesn’t want to take any medicine?

Serah Sannoh of Rutgers University wanted to find another way to relieve her menstrual pains. The literature review she presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society found multiple studies that examined dietary patterns that resulted in menstrual pain.

In Ms. Sannoh’s analysis, she looked at how certain foods have an effect on cramps. Do they contribute to the pain or reduce it? Diets high in processed foods, oils, sugars, salt, and omega-6 fatty acids promote inflammation in the muscles around the uterus. Thus, cramps.

The answer, sometimes, is not to add a medicine but to change our daily practices, she suggested. Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce pain, and those who practiced a vegan diet had the lowest muscle inflammation rates. So more salmon and fewer Swedish Fish.

Stage 1 of the robot apocalypse is already upon us

The mere mention of a robot apocalypse is enough to conjure images of terrifying robot soldiers with Austrian accents harvesting and killing humanity while the survivors live blissfully in a simulation and do low-gravity kung fu with high-profile Hollywood actors. They’ll even take over the navy.

Reality is often less exciting than the movies, but rest assured, the robots will not be denied their dominion of Earth. Our future robot overlords are simply taking a more subtle, less dramatic route toward their ultimate subjugation of mankind: They’re making us all sad and burned out.

The research pulls from work conducted in multiple countries to paint a picture of a humanity filled with anxiety about jobs as robotic automation grows more common. In India, a survey of automobile manufacturing works showed that working alongside industrial robots was linked with greater reports of burnout and workplace incivility. In Singapore, a group of college students randomly assigned to read one of three articles – one about the use of robots in business, a generic article about robots, or an article unrelated to robots – were then surveyed about their job security concerns. Three guesses as to which group was most worried.

In addition, the researchers analyzed 185 U.S. metropolitan areas for robot prevalence alongside use of job-recruiting websites and found that the more robots a city used, the more common job searches were. Unemployment rates weren’t affected, suggesting people had job insecurity because of robots. Sure, there could be other, nonrobotic reasons for this, but that’s no fun. We’re here because we fear our future android rulers.

It’s not all doom and gloom, fortunately. In an online experiment, the study authors found that self-affirmation exercises, such as writing down characteristics or values important to us, can overcome the existential fears and lessen concern about robots in the workplace. One of the authors noted that, while some fear is justified, “media reports on new technologies like robots and algorithms tend to be apocalyptic in nature, so people may develop an irrational fear about them.”

Oops. Our bad.

Apocalypse, stage 2: Leaping oral superorganisms

The terms of our secret agreement with the shadowy-but-powerful dental-industrial complex stipulate that LOTME can only cover tooth-related news once a year. This is that once a year.

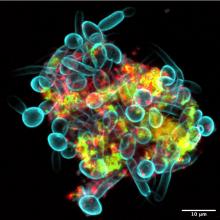

Since we’ve already dealt with a robot apocalypse, how about a sci-fi horror story? A story with a “cross-kingdom partnership” in which assemblages of bacteria and fungi perform feats greater than either could achieve on its own. A story in which new microscopy technologies allow “scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time,” according to a statement from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

While looking at saliva samples from toddlers with severe tooth decay, lead author Zhi Ren and associates “noticed the bacteria and fungi forming these assemblages and developing motions we never thought they would possess: a ‘walking-like’ and ‘leaping-like’ mobility. … It’s almost like a new organism – a superorganism – with new functions,” said senior author Hyun Koo, DDS, PhD, of Penn Dental Medicine.

Did he say “mobility”? He did, didn’t he?

To study these alleged superorganisms, they set up a laboratory system “using the bacteria, fungi, and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva,” the university explained.

“Incubated in human saliva.” There’s a phrase you don’t see every day.

It only took a few hours for the investigators to observe the bacterial/fungal assemblages making leaps of more than 100 microns across the tooth-like material. “That is more than 200 times their own body length,” Dr. Ren said, “making them even better than most vertebrates, relative to body size. For example, tree frogs and grasshoppers can leap forward about 50 times and 20 times their own body length, respectively.”

So, will it be the robots or the evil superorganisms? Let us give you a word of advice: Always bet on bacteria.

Foods for thought: Menstrual cramp prevention

For those who menstruate, it’s typical for that time of the month to bring cravings for things that may give a serotonin boost that eases the rise in stress hormones. Chocolate and other foods high in sugar fall into that category, but they could actually be adding to the problem.

About 90% of adolescent girls have menstrual pain, and it’s the leading cause of school absences for the demographic. Muscle relaxers and PMS pills are usually the recommended solution to alleviating menstrual cramps, but what if the patient doesn’t want to take any medicine?

Serah Sannoh of Rutgers University wanted to find another way to relieve her menstrual pains. The literature review she presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society found multiple studies that examined dietary patterns that resulted in menstrual pain.

In Ms. Sannoh’s analysis, she looked at how certain foods have an effect on cramps. Do they contribute to the pain or reduce it? Diets high in processed foods, oils, sugars, salt, and omega-6 fatty acids promote inflammation in the muscles around the uterus. Thus, cramps.

The answer, sometimes, is not to add a medicine but to change our daily practices, she suggested. Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce pain, and those who practiced a vegan diet had the lowest muscle inflammation rates. So more salmon and fewer Swedish Fish.

Stage 1 of the robot apocalypse is already upon us

The mere mention of a robot apocalypse is enough to conjure images of terrifying robot soldiers with Austrian accents harvesting and killing humanity while the survivors live blissfully in a simulation and do low-gravity kung fu with high-profile Hollywood actors. They’ll even take over the navy.

Reality is often less exciting than the movies, but rest assured, the robots will not be denied their dominion of Earth. Our future robot overlords are simply taking a more subtle, less dramatic route toward their ultimate subjugation of mankind: They’re making us all sad and burned out.

The research pulls from work conducted in multiple countries to paint a picture of a humanity filled with anxiety about jobs as robotic automation grows more common. In India, a survey of automobile manufacturing works showed that working alongside industrial robots was linked with greater reports of burnout and workplace incivility. In Singapore, a group of college students randomly assigned to read one of three articles – one about the use of robots in business, a generic article about robots, or an article unrelated to robots – were then surveyed about their job security concerns. Three guesses as to which group was most worried.

In addition, the researchers analyzed 185 U.S. metropolitan areas for robot prevalence alongside use of job-recruiting websites and found that the more robots a city used, the more common job searches were. Unemployment rates weren’t affected, suggesting people had job insecurity because of robots. Sure, there could be other, nonrobotic reasons for this, but that’s no fun. We’re here because we fear our future android rulers.

It’s not all doom and gloom, fortunately. In an online experiment, the study authors found that self-affirmation exercises, such as writing down characteristics or values important to us, can overcome the existential fears and lessen concern about robots in the workplace. One of the authors noted that, while some fear is justified, “media reports on new technologies like robots and algorithms tend to be apocalyptic in nature, so people may develop an irrational fear about them.”

Oops. Our bad.

Apocalypse, stage 2: Leaping oral superorganisms

The terms of our secret agreement with the shadowy-but-powerful dental-industrial complex stipulate that LOTME can only cover tooth-related news once a year. This is that once a year.

Since we’ve already dealt with a robot apocalypse, how about a sci-fi horror story? A story with a “cross-kingdom partnership” in which assemblages of bacteria and fungi perform feats greater than either could achieve on its own. A story in which new microscopy technologies allow “scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time,” according to a statement from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

While looking at saliva samples from toddlers with severe tooth decay, lead author Zhi Ren and associates “noticed the bacteria and fungi forming these assemblages and developing motions we never thought they would possess: a ‘walking-like’ and ‘leaping-like’ mobility. … It’s almost like a new organism – a superorganism – with new functions,” said senior author Hyun Koo, DDS, PhD, of Penn Dental Medicine.

Did he say “mobility”? He did, didn’t he?

To study these alleged superorganisms, they set up a laboratory system “using the bacteria, fungi, and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva,” the university explained.

“Incubated in human saliva.” There’s a phrase you don’t see every day.

It only took a few hours for the investigators to observe the bacterial/fungal assemblages making leaps of more than 100 microns across the tooth-like material. “That is more than 200 times their own body length,” Dr. Ren said, “making them even better than most vertebrates, relative to body size. For example, tree frogs and grasshoppers can leap forward about 50 times and 20 times their own body length, respectively.”

So, will it be the robots or the evil superorganisms? Let us give you a word of advice: Always bet on bacteria.

Foods for thought: Menstrual cramp prevention

For those who menstruate, it’s typical for that time of the month to bring cravings for things that may give a serotonin boost that eases the rise in stress hormones. Chocolate and other foods high in sugar fall into that category, but they could actually be adding to the problem.

About 90% of adolescent girls have menstrual pain, and it’s the leading cause of school absences for the demographic. Muscle relaxers and PMS pills are usually the recommended solution to alleviating menstrual cramps, but what if the patient doesn’t want to take any medicine?

Serah Sannoh of Rutgers University wanted to find another way to relieve her menstrual pains. The literature review she presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society found multiple studies that examined dietary patterns that resulted in menstrual pain.

In Ms. Sannoh’s analysis, she looked at how certain foods have an effect on cramps. Do they contribute to the pain or reduce it? Diets high in processed foods, oils, sugars, salt, and omega-6 fatty acids promote inflammation in the muscles around the uterus. Thus, cramps.

The answer, sometimes, is not to add a medicine but to change our daily practices, she suggested. Foods high in omega-3 fatty acids helped reduce pain, and those who practiced a vegan diet had the lowest muscle inflammation rates. So more salmon and fewer Swedish Fish.

Stage 1 of the robot apocalypse is already upon us

The mere mention of a robot apocalypse is enough to conjure images of terrifying robot soldiers with Austrian accents harvesting and killing humanity while the survivors live blissfully in a simulation and do low-gravity kung fu with high-profile Hollywood actors. They’ll even take over the navy.

Reality is often less exciting than the movies, but rest assured, the robots will not be denied their dominion of Earth. Our future robot overlords are simply taking a more subtle, less dramatic route toward their ultimate subjugation of mankind: They’re making us all sad and burned out.

The research pulls from work conducted in multiple countries to paint a picture of a humanity filled with anxiety about jobs as robotic automation grows more common. In India, a survey of automobile manufacturing works showed that working alongside industrial robots was linked with greater reports of burnout and workplace incivility. In Singapore, a group of college students randomly assigned to read one of three articles – one about the use of robots in business, a generic article about robots, or an article unrelated to robots – were then surveyed about their job security concerns. Three guesses as to which group was most worried.

In addition, the researchers analyzed 185 U.S. metropolitan areas for robot prevalence alongside use of job-recruiting websites and found that the more robots a city used, the more common job searches were. Unemployment rates weren’t affected, suggesting people had job insecurity because of robots. Sure, there could be other, nonrobotic reasons for this, but that’s no fun. We’re here because we fear our future android rulers.

It’s not all doom and gloom, fortunately. In an online experiment, the study authors found that self-affirmation exercises, such as writing down characteristics or values important to us, can overcome the existential fears and lessen concern about robots in the workplace. One of the authors noted that, while some fear is justified, “media reports on new technologies like robots and algorithms tend to be apocalyptic in nature, so people may develop an irrational fear about them.”

Oops. Our bad.

Apocalypse, stage 2: Leaping oral superorganisms

The terms of our secret agreement with the shadowy-but-powerful dental-industrial complex stipulate that LOTME can only cover tooth-related news once a year. This is that once a year.

Since we’ve already dealt with a robot apocalypse, how about a sci-fi horror story? A story with a “cross-kingdom partnership” in which assemblages of bacteria and fungi perform feats greater than either could achieve on its own. A story in which new microscopy technologies allow “scientists to visualize the behavior of living microbes in real time,” according to a statement from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

While looking at saliva samples from toddlers with severe tooth decay, lead author Zhi Ren and associates “noticed the bacteria and fungi forming these assemblages and developing motions we never thought they would possess: a ‘walking-like’ and ‘leaping-like’ mobility. … It’s almost like a new organism – a superorganism – with new functions,” said senior author Hyun Koo, DDS, PhD, of Penn Dental Medicine.

Did he say “mobility”? He did, didn’t he?

To study these alleged superorganisms, they set up a laboratory system “using the bacteria, fungi, and a tooth-like material, all incubated in human saliva,” the university explained.

“Incubated in human saliva.” There’s a phrase you don’t see every day.

It only took a few hours for the investigators to observe the bacterial/fungal assemblages making leaps of more than 100 microns across the tooth-like material. “That is more than 200 times their own body length,” Dr. Ren said, “making them even better than most vertebrates, relative to body size. For example, tree frogs and grasshoppers can leap forward about 50 times and 20 times their own body length, respectively.”

So, will it be the robots or the evil superorganisms? Let us give you a word of advice: Always bet on bacteria.

Digital mental health training acceptable to boarding teens

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – A modular digital intervention to teach mental health skills to youth awaiting transfer to psychiatric care appeared feasible to implement and acceptable to teens and their parents, according to a study presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

“This program has the potential to teach evidence-based mental health skills to youth during boarding, providing a head start on recovery prior to psychiatric hospitalization,” study coauthor Samantha House, DO, MPH, section chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., told attendees.

Mental health boarding has become increasingly common as psychiatric care resources have been stretched by a crisis in pediatric mental health that began even before the COVID pandemic. Since youth often don’t receive evidence-based therapies while boarding, Dr. House and her coauthor, JoAnna K. Leyenaar, MD, PhD, MPH, developed a pilot program called I-CARE, which stands for Improving Care, Accelerating Recovery and Education.

I-CARE is a digital health intervention that combines videos on a tablet with workbook exercises that teach mental health skills. The seven modules include an introduction and one each on schedule-making, safety planning, psychoeducation, behavioral activation, relaxation skills, and mindfulness skills. Licensed nursing assistants who have received a 6-hour training from a clinical psychologist administer the program and provide safety supervision during boarding.

“I-CARE was designed to be largely self-directed, supported by ‘coaches’ who are not mental health professionals,” Dr. Leyenaar, vice chair of research in the department of pediatrics and an associate professor of pediatrics at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said in an interview. With this model, the program requires minimal additional resources beyond the tablets and workbooks, and is designed for implementation in settings with few or no mental health professionals, she said.

Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and an attending physician at Seattle Children’s Hospital, was not involved in the study but was excited to see it.

“I think it’s a really good idea, and I like that it’s being studied,” Dr. Breuner said in an interview. She said the health care and public health system has let down an entire population who data had shown were experiencing mental health problems.

“We knew before the pandemic that behavioral health issues were creeping up slowly with anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and, of course, substance use disorders and eating disorders, and not a lot was being done about it,” Dr. Breuner said, and the pandemic exacerbated those issues. ”I don’t know why no one realized that this was going to be the downstream effect of having no socialization for kids for 18 months and limited resources for those who we need desperately to provide care for,” especially BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] kids and underresourced kids.

That sentiment is exactly what inspired the creation of the program, according to Dr. Leyenaar.

The I-CARE program was implemented at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in November 2021 for adolescents aged 12-17 who were boarding because of suicidality or self-harm. The program and study excluded youth with psychosis and other cognitive or behavioral conditions that didn’t fit with the skills taught by the module training.

The researchers qualitatively evaluated the I-CARE program in youth who were offered at least two I-CARE modules and with parents present during boarding.

Twenty-four youth, with a median age of 14, were offered the I-CARE program between November 2021 and April 2022 while boarding for a median 8 days. Most of the patients were female (79%), and a third were transgender or gender diverse. Most were White (83%), and about two-thirds had Medicaid (62.5%). The most common diagnoses among the participants were major depressive disorder (71%) and generalized anxiety disorder (46%). Others included PTSD (29%), restrictive eating disorder (21%), and bipolar disorder (12.5%).

All offered the program completed the first module, and 79% participated in additional modules. The main reason for discontinuation was transfer to another facility, but a few youth either refused to engage with the program or felt they knew the material well enough that they weren’t benefiting from it.

The evaluation involved 16 youth, seven parents, and 17 clinicians. On a Likert scale, the composite score for the program’s appropriateness – suitability, applicability, and meeting needs – was an average 3.7, with a higher rating from clinicians (4.3) and caregivers (3.5) than youth (2.8).

“Some youth felt the intervention was better suited for a younger audience or those with less familiarity with mental health skills, but they acknowledged that the intervention would be helpful and appropriate for others,” Dr. House, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Geisel School of Medicine, said.

Youth rated the acceptability of the program more highly (3.6) and all three groups found it easy to use, with an average feasibility score of 4 across the board. The program’s acceptability received an average score of 4 from parents and clinicians.

”Teens seem to particularly value the psychoeducation module that explains the relationship between thoughts and feelings, as well as the opportunity to develop a personalized safety plan,” Dr. Leyenaar said.

Among the challenges expressed by the participating teens were that the loud sounds and beeping in the hospital made it difficult to practice mindfulness and that they often had to wait for staff to be available to do I-CARE.

“I feel like not many people have been trained yet,” one teen said, “so to have more nurses available to do I-CARE would be helpful.”

Another participant found the coaches helpful. “Sometimes they were my nurse, sometimes they were someone I never met before. … and also, they were all really, really nice,” the teen said.

Another teen regarded the material as “really surface-level mental health stuff” that they thought “could be helpful to other people who are here for the first time.” But others found the content more beneficial.

“The videos were helpful. … I was worried that they weren’t going to be very informative, but they did make sense to me,” one participant said. “They weren’t overcomplicating things. … They weren’t saying anything I didn’t understand, so that was good.”

The researchers next plan to conduct a multisite study to determine the program’s effectiveness in improving health outcomes and reducing suicidal ideation. Dr. House and Dr. Leyenaar are looking at ways to refine the program.

”We may narrow the age range for participants, with an upper age limit of 16, since some older teens said that the modules were best suited for a younger audience,” Dr. Leyenaar said. “We are also discussing how to best support youth who are readmitted to our hospital and have participated in I-CARE previously.”

Dr. Breuner said she would be interested to see, in future studies of the program, whether it reduced the likelihood of inpatient psychiatric stay, the length of psychiatric stay after admission, or the risk of readmission. She also wondered if the program might be offered in languages other than English, whether a version might be specifically designed for BIPOC youth, and whether the researchers had considered offering the intervention to caregivers as well.

The modules are teaching the kids but should they also be teaching the parents? Dr. Breuner wondered. A lot of times, she said, the parents are bringing these kids in because they don’t know what to do and can’t deal with them anymore. Offering modules on the same skills to caregivers would also enable the caregivers to reinforce and reteach the skills to their children, especially if the youth struggled to really take in what the modules were trying to teach.

Dr. Leyenaar said she expects buy-in for a program like this would be high at other institutions, but it’s premature to scale it up until they’ve conducted at least another clinical trial on its effectiveness. The biggest potential barrier to buy-in that Dr. Breuner perceived would be cost.

“It’s always difficult when it costs money” since the hospital needs to train the clinicians who provide the care, Dr. Breuner said, but it’s possible those costs could be offset if the program reduces the risk of readmission or return to the emergency department.

While the overall risk of harms from the intervention are low, Dr. Breuner said it is important to be conscious that the intervention may not necessarily be appropriate for all youth.

“There’s always risk when there’s a trauma background, and you have to be very careful, especially with mindfulness training,” Dr. Breuner said. For those with a history of abuse or other adverse childhood experiences “for someone to get into a very calm, still place can actually be counterproductive.”

Dr. Breuner especially appreciated that the researchers involved the youth and caregivers in the evaluation process. “That the parents expressed positive attitudes is really incredible,” she said.

Dr. House, Dr. Leyenaar, and Dr. Breuner had no disclosures. No external funding was noted for the study.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – A modular digital intervention to teach mental health skills to youth awaiting transfer to psychiatric care appeared feasible to implement and acceptable to teens and their parents, according to a study presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference.

“This program has the potential to teach evidence-based mental health skills to youth during boarding, providing a head start on recovery prior to psychiatric hospitalization,” study coauthor Samantha House, DO, MPH, section chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, N.H., told attendees.

Mental health boarding has become increasingly common as psychiatric care resources have been stretched by a crisis in pediatric mental health that began even before the COVID pandemic. Since youth often don’t receive evidence-based therapies while boarding, Dr. House and her coauthor, JoAnna K. Leyenaar, MD, PhD, MPH, developed a pilot program called I-CARE, which stands for Improving Care, Accelerating Recovery and Education.

I-CARE is a digital health intervention that combines videos on a tablet with workbook exercises that teach mental health skills. The seven modules include an introduction and one each on schedule-making, safety planning, psychoeducation, behavioral activation, relaxation skills, and mindfulness skills. Licensed nursing assistants who have received a 6-hour training from a clinical psychologist administer the program and provide safety supervision during boarding.

“I-CARE was designed to be largely self-directed, supported by ‘coaches’ who are not mental health professionals,” Dr. Leyenaar, vice chair of research in the department of pediatrics and an associate professor of pediatrics at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said in an interview. With this model, the program requires minimal additional resources beyond the tablets and workbooks, and is designed for implementation in settings with few or no mental health professionals, she said.

Cora Breuner, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, Seattle, and an attending physician at Seattle Children’s Hospital, was not involved in the study but was excited to see it.

“I think it’s a really good idea, and I like that it’s being studied,” Dr. Breuner said in an interview. She said the health care and public health system has let down an entire population who data had shown were experiencing mental health problems.

“We knew before the pandemic that behavioral health issues were creeping up slowly with anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and, of course, substance use disorders and eating disorders, and not a lot was being done about it,” Dr. Breuner said, and the pandemic exacerbated those issues. ”I don’t know why no one realized that this was going to be the downstream effect of having no socialization for kids for 18 months and limited resources for those who we need desperately to provide care for,” especially BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] kids and underresourced kids.

That sentiment is exactly what inspired the creation of the program, according to Dr. Leyenaar.

The I-CARE program was implemented at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in November 2021 for adolescents aged 12-17 who were boarding because of suicidality or self-harm. The program and study excluded youth with psychosis and other cognitive or behavioral conditions that didn’t fit with the skills taught by the module training.

The researchers qualitatively evaluated the I-CARE program in youth who were offered at least two I-CARE modules and with parents present during boarding.

Twenty-four youth, with a median age of 14, were offered the I-CARE program between November 2021 and April 2022 while boarding for a median 8 days. Most of the patients were female (79%), and a third were transgender or gender diverse. Most were White (83%), and about two-thirds had Medicaid (62.5%). The most common diagnoses among the participants were major depressive disorder (71%) and generalized anxiety disorder (46%). Others included PTSD (29%), restrictive eating disorder (21%), and bipolar disorder (12.5%).

All offered the program completed the first module, and 79% participated in additional modules. The main reason for discontinuation was transfer to another facility, but a few youth either refused to engage with the program or felt they knew the material well enough that they weren’t benefiting from it.

The evaluation involved 16 youth, seven parents, and 17 clinicians. On a Likert scale, the composite score for the program’s appropriateness – suitability, applicability, and meeting needs – was an average 3.7, with a higher rating from clinicians (4.3) and caregivers (3.5) than youth (2.8).

“Some youth felt the intervention was better suited for a younger audience or those with less familiarity with mental health skills, but they acknowledged that the intervention would be helpful and appropriate for others,” Dr. House, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Geisel School of Medicine, said.

Youth rated the acceptability of the program more highly (3.6) and all three groups found it easy to use, with an average feasibility score of 4 across the board. The program’s acceptability received an average score of 4 from parents and clinicians.

”Teens seem to particularly value the psychoeducation module that explains the relationship between thoughts and feelings, as well as the opportunity to develop a personalized safety plan,” Dr. Leyenaar said.