User login

Two cases of possible remission in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has been shown to generally have a poor prognosis. Within the first 3-5 years of diagnosis, the mortality rate is the highest of all the subtypes of breast cancer, although late relapses are less common.1,2 TNBC is markedly heterogeneous tumor, and the individual prognosis can vary widely.1,3 Metastatic TNBC is generally considered a noncurable disease. The median time from recurrence to death for metastatic disease is about 9 months, compared with 20 months for patients with other subtypes of breast cancers.4,5 The median survival time for patients with metastatic TNBC is about 13 months.3

New targeted therapies are emerging for breast cancer, but there are currently no effective targeted therapies for patients with TNBC. In addition, few reports in the literature that discuss long-term complete remissions in patients who have metastatic TNBC. Here, we describe two cases in which patients with metastatic TNBC achieved sustained complete response on conventional chemotherapy regimens.

Case presentations and summaries

Case 1

A 59-year-old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed on biopsy in February 2005 with locally advanced right breast cancer (stage T2N2bM0). She underwent lumpectomy, and the results of her pathology tests revealed a triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma. She was started on 4 cycles of neoadjuvant doxorubicin (60 mg/m2 IV) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2 IV)

In November 2007, the patient was found to have right chest wall metastasis confirmed by ultrasound-guided needle biopsy, and underwent right-side chest wall and partial sternum resection. In May 2008, she had recurrence in the left axilla, and biopsy results showed that she had TNBC disease. She was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) and bevacizumab (10 mg/kg every 2 weeks) continued until July 2008. Chemotherapy was stopped in July 2008 because of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection of the chest wall and was not resumed after the infection had resolved.

A follow-up positron-emission tomography– computed tomography (PET-CT) scan in June 2009, showed no evidence of disease and the scan was negative for disease in her left axilla. Another PET scan about a year later, in September 2010, was also negative for any disease recurrence.

The patient has continued her follow-up with physical examinations and imaging scans. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (December 2010), an MRI of the breasts (February 2011, August 2015), and a PET-CT scan (April 2015, Figure 1) were all negative for any evidence of disease. In September 2011, she had a CT-guided biopsy of a medial right clavicle and costal junction lesion; and in November 2011 and January 2013, surgical biopsies of the right chest wall and first rib lesions, all negative for any evidence for malignancy. At her last follow-up in January 2017, the patient remained in remission.

Case 2

A 68-year old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed in Russia in 2004 with infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the right breast (T4N1M0; receptor status unknown at that time). She underwent a right modified radical mastectomy and received adjuvant chemotherapy with 4 cycles of cyclophosphamide (100 mg/m2 day 1 to day 14), methotrexate (40 mg/m2 IV day 1 and day 8), and fluorouracil (600 mg/m2 IV, day 1 and day 8) followed by 2 cycles of docetaxel (75 mg/m2 IV) and anthracycline adriyamycin (50 mg/m2 IV). The patient later received radiation therapy (radiation dose not known, treatment was received in Russia), and completed her treatment in November 2004.

The patient moved to the United States and was started on 25 mg daily exemestane in February 2005. In March 2009, she was diagnosed by biopsy to have recurrence in her internal mammary and hilar lymph nodes and sternum. The cancer was found to be ER- and PR-negative and HER2-neu–negative. The patient was treated with radiation therapy (37.5 Gy in 15 fractions) to sternum and hilar and internal mammary lymph nodes with improvement in pain and shrinkage of lymph nodes size. In May 2009, she was started on 1,500 mg oral twice a day capecitabine (3 cycles). The therapy was started after completion of radiation treatment due to progression of disease. She developed hand-and-foot syndrome as side effect of the capecitabine, so the dose was reduced. She was switched to gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle) as a single-agent therapy and completed 3 cycles. A follow-up PET-CT scan in February 2010 showed no evidence of disease.

In May 2010, the patient had a recurrence in the same metastatic foci as before, and she was again started on gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle). She continued gemcitabine until there was evidence of disease progression on a PET-CT scan in October 2010, which showed new areas of disease in the left parasternal region, left sternum, prevascular mediastinal nodes, and left supraclavicular, hilar and axillary adenopathy, and fourth thoracic vertebra. Gemcitabine was discontinued and patient was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) for 6 cycles. Paclitaxel was discontinued after 6 weeks because she developed a drug-related rash. A follow-up PET-CT scan in December 2010 again showed complete resolution of disease in terms of response.

In March 2011, PET imaging showed progression of disease in the left chest wall and axillary lymph nodes, so the patient was started on eribulin therapy (1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 21-day cycle) and completed 3 cycles. In May 2011, PET imaging showed complete response to treatment with no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease. The patient has not had chemotherapy since November 2011, and surveillance PET imaging has not demonstrated any recurrence of disease (Figure 2). Following her last follow-up in November 2016, the patient remains in remission.

Discussion

Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are defined as tumors that lack expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2, and represent about 12%-17% of breast cancer cases.1,6 TNBCs tend to be larger in size at diagnosis than are other subtypes, are usually high-grade (poorly differentiated), and are more likely to be invasive ductal carcinomas.1,7 TNBC and the basal-like breast cancers as a group are associated with an adverse prognosis.1,7 There is no standard preferred chemotherapy and no biologic therapy available for TNBC.1,6-7 A sharp decline in survival outcome during the first 3-5 years after diagnosis initial is observed in TNBC, although the distant relapses after this time are less common.1 Beyond 10 years from diagnosis, the relapses are seen more common among patients with ER-positive cancers than among those with ER-negative subtype cancers. Therefore, although TNBCs are biologically aggressive, many are possibly curable, and this reflects their interesting characteristic heterogeneity.1,6

Chemotherapy is currently the mainstay of systemic medical treatment. Although patients with TNBC have a worse outcome after chemotherapy than patients with breast cancers of other subtypes, it still improves their outcome to a greater extent than in patients with ER-positive subtypes.1,6,7 Considering the heterogeneity of TNBC, it is difficult to predict which patients will benefit more from chemotherapy. The same has been observed in previous studies when subgroups of women with TNBC were extremely sensitive to chemotherapy, whereas in others it was of uncertain benefit.1

Currently, there is no preferred standard form of chemotherapy for TNBC. There are few case reports that demonstrate long-term survival and complete remission in metastatic TNBC. Shakir has reported on a significant clinical response to nab-paclitaxel monotherapy in a patient with triple-negative BRCA1-positive breast cancer, although patient survived a little more than 5 years and died with central nervous system recurrence.8 Montero and Gluck have described a patient with metastatic TNBC who was treated with nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, and bevacizumab and who also survived for 5 years after diagnosis.9 Different retrospective analyses have suggested that the addition of docetaxel or paclitaxel to anthracycline-containing adjuvant regimens may be of greater benefit for the treatment of TNBC than for ER-positive tumors.10 A meta-analysis of trials comparing the effects of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF, which was used in Case 2) with anthracycline-containing regimens has suggested that the latter therapy regimen is more effective against TNBC,11 although another retrospective analysis of a separate trial suggested the opposite for basal-like breast cancers. 12 The authors of the latter analysis concluded that anthracycline-containing adjuvant chemotherapy regimens are inferior to adjuvant CMF in women with basal breast cancer.12

Miller and colleagues have shown that the addition of bevacizumab (angiogenesis inhibitor) to paclitaxel (used in Case 1) improved progression-free survival (median PFS, 11.8 vs 5.9 months; hazard ratio [HR] for progression, 0.60; P < .001) in women with TNBC as it did in the overall study group (HR, 0.53 and 0.60, respectively), although the overall survival rate was similar in the two groups (median OS, 26.7 vs 25.2 months; HR, 0.88; P = .16).13

An interesting clinical target in TNBC is the enzyme poly (adenosine diphosphate– ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is involved in base-excision repair after DNA damage. PARP inhibitors have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and in sporadic TNBC cancers.14 Similarly, the use of an oral PARP inhibitor, olaparib, resulted in tumor regression in up to 41% of patients carrying BRCA mutations, most of whom had TNBC.15

Conclusion

TNBC and basal-like breast cancers show aggressive clinical behavior, but a subgroup of these cancers may be markedly sensitive to chemotherapy and associated with a good prognosis when treated with conventional chemotherapy regimens. The two cases presented here show that some patients can get a prolonged disease control from chemotherapy, even after progressing on multiple previous chemotherapy regimens and that after, 5 years or so, these rare patients could be in true long-term remission. Novel approaches, for example PARP inhibitors, have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and as well as sporadic TNBC.

1. Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS, Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938-1948.

2. Pogoda K, Niwińska A, Murawska M, Pieńkowski T. Analysis of pattern, time and risk factors influencing recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):388.

3. Kassam F, Enright K, Dent R, et al. Survival outcomes for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: implications for clinical practice and trial design. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(1):29-33.

4. Perou CM. Molecular stratification of triple-negative breast cancers. Oncologist. 2010;15(suppl 5):39-48.

5. Rakha EA, Chan S. Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011;23(9):587-600.

6. Williams N, Harris L. Triple-negative breast cancer in the post-genomic era. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(9):859-860, 864.

7. Randhawa SK, Venur VA, Kawsar H, et al. A retrospective comparison of the characteristics and recurrence outcome of triple-negative and triple-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl; abstr 1038).

8. Shakir AR. Strong and sustained response to treatment with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel in a patient with metastatic, triple-negative, BRCA1-positive breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7(1)252-259.

9. Montero A, Glück S. Long-term complete remission with nab-paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and gemcitabine combination therapy in a patient with triple-negative metastatic breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5(3):687-692.

10. Hayes DF, Thor AD, Dressler LG, et al. HER2 and response to paclitaxel in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1496-1506.

11. Di Leo A, Isola J, Piette F, et al. A meta- analysis of phase III trials evaluating the predictive value of HER2 and topoisomerase alpha in early breast cancer patients treated with CMF or anthracycline-based adjuvant therapy [SABCS, abstract 705]. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/69/2_Supplement/705. Published 2008. Accessed May 4, 2017.

12. Cheang M, Chia SK, Tu D, et al. Anthracycline in basal breast cancer: the NCIC-CTG trial MA5 comparing adjuvant CMF to CEF [ASCO; abstract 519]. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/35150-65. Published 2009. Accessed May 4, 2017.

13. Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666-2676.

14. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123-134.

15. Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235-244.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has been shown to generally have a poor prognosis. Within the first 3-5 years of diagnosis, the mortality rate is the highest of all the subtypes of breast cancer, although late relapses are less common.1,2 TNBC is markedly heterogeneous tumor, and the individual prognosis can vary widely.1,3 Metastatic TNBC is generally considered a noncurable disease. The median time from recurrence to death for metastatic disease is about 9 months, compared with 20 months for patients with other subtypes of breast cancers.4,5 The median survival time for patients with metastatic TNBC is about 13 months.3

New targeted therapies are emerging for breast cancer, but there are currently no effective targeted therapies for patients with TNBC. In addition, few reports in the literature that discuss long-term complete remissions in patients who have metastatic TNBC. Here, we describe two cases in which patients with metastatic TNBC achieved sustained complete response on conventional chemotherapy regimens.

Case presentations and summaries

Case 1

A 59-year-old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed on biopsy in February 2005 with locally advanced right breast cancer (stage T2N2bM0). She underwent lumpectomy, and the results of her pathology tests revealed a triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma. She was started on 4 cycles of neoadjuvant doxorubicin (60 mg/m2 IV) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2 IV)

In November 2007, the patient was found to have right chest wall metastasis confirmed by ultrasound-guided needle biopsy, and underwent right-side chest wall and partial sternum resection. In May 2008, she had recurrence in the left axilla, and biopsy results showed that she had TNBC disease. She was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) and bevacizumab (10 mg/kg every 2 weeks) continued until July 2008. Chemotherapy was stopped in July 2008 because of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection of the chest wall and was not resumed after the infection had resolved.

A follow-up positron-emission tomography– computed tomography (PET-CT) scan in June 2009, showed no evidence of disease and the scan was negative for disease in her left axilla. Another PET scan about a year later, in September 2010, was also negative for any disease recurrence.

The patient has continued her follow-up with physical examinations and imaging scans. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (December 2010), an MRI of the breasts (February 2011, August 2015), and a PET-CT scan (April 2015, Figure 1) were all negative for any evidence of disease. In September 2011, she had a CT-guided biopsy of a medial right clavicle and costal junction lesion; and in November 2011 and January 2013, surgical biopsies of the right chest wall and first rib lesions, all negative for any evidence for malignancy. At her last follow-up in January 2017, the patient remained in remission.

Case 2

A 68-year old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed in Russia in 2004 with infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the right breast (T4N1M0; receptor status unknown at that time). She underwent a right modified radical mastectomy and received adjuvant chemotherapy with 4 cycles of cyclophosphamide (100 mg/m2 day 1 to day 14), methotrexate (40 mg/m2 IV day 1 and day 8), and fluorouracil (600 mg/m2 IV, day 1 and day 8) followed by 2 cycles of docetaxel (75 mg/m2 IV) and anthracycline adriyamycin (50 mg/m2 IV). The patient later received radiation therapy (radiation dose not known, treatment was received in Russia), and completed her treatment in November 2004.

The patient moved to the United States and was started on 25 mg daily exemestane in February 2005. In March 2009, she was diagnosed by biopsy to have recurrence in her internal mammary and hilar lymph nodes and sternum. The cancer was found to be ER- and PR-negative and HER2-neu–negative. The patient was treated with radiation therapy (37.5 Gy in 15 fractions) to sternum and hilar and internal mammary lymph nodes with improvement in pain and shrinkage of lymph nodes size. In May 2009, she was started on 1,500 mg oral twice a day capecitabine (3 cycles). The therapy was started after completion of radiation treatment due to progression of disease. She developed hand-and-foot syndrome as side effect of the capecitabine, so the dose was reduced. She was switched to gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle) as a single-agent therapy and completed 3 cycles. A follow-up PET-CT scan in February 2010 showed no evidence of disease.

In May 2010, the patient had a recurrence in the same metastatic foci as before, and she was again started on gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle). She continued gemcitabine until there was evidence of disease progression on a PET-CT scan in October 2010, which showed new areas of disease in the left parasternal region, left sternum, prevascular mediastinal nodes, and left supraclavicular, hilar and axillary adenopathy, and fourth thoracic vertebra. Gemcitabine was discontinued and patient was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) for 6 cycles. Paclitaxel was discontinued after 6 weeks because she developed a drug-related rash. A follow-up PET-CT scan in December 2010 again showed complete resolution of disease in terms of response.

In March 2011, PET imaging showed progression of disease in the left chest wall and axillary lymph nodes, so the patient was started on eribulin therapy (1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 21-day cycle) and completed 3 cycles. In May 2011, PET imaging showed complete response to treatment with no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease. The patient has not had chemotherapy since November 2011, and surveillance PET imaging has not demonstrated any recurrence of disease (Figure 2). Following her last follow-up in November 2016, the patient remains in remission.

Discussion

Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are defined as tumors that lack expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2, and represent about 12%-17% of breast cancer cases.1,6 TNBCs tend to be larger in size at diagnosis than are other subtypes, are usually high-grade (poorly differentiated), and are more likely to be invasive ductal carcinomas.1,7 TNBC and the basal-like breast cancers as a group are associated with an adverse prognosis.1,7 There is no standard preferred chemotherapy and no biologic therapy available for TNBC.1,6-7 A sharp decline in survival outcome during the first 3-5 years after diagnosis initial is observed in TNBC, although the distant relapses after this time are less common.1 Beyond 10 years from diagnosis, the relapses are seen more common among patients with ER-positive cancers than among those with ER-negative subtype cancers. Therefore, although TNBCs are biologically aggressive, many are possibly curable, and this reflects their interesting characteristic heterogeneity.1,6

Chemotherapy is currently the mainstay of systemic medical treatment. Although patients with TNBC have a worse outcome after chemotherapy than patients with breast cancers of other subtypes, it still improves their outcome to a greater extent than in patients with ER-positive subtypes.1,6,7 Considering the heterogeneity of TNBC, it is difficult to predict which patients will benefit more from chemotherapy. The same has been observed in previous studies when subgroups of women with TNBC were extremely sensitive to chemotherapy, whereas in others it was of uncertain benefit.1

Currently, there is no preferred standard form of chemotherapy for TNBC. There are few case reports that demonstrate long-term survival and complete remission in metastatic TNBC. Shakir has reported on a significant clinical response to nab-paclitaxel monotherapy in a patient with triple-negative BRCA1-positive breast cancer, although patient survived a little more than 5 years and died with central nervous system recurrence.8 Montero and Gluck have described a patient with metastatic TNBC who was treated with nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, and bevacizumab and who also survived for 5 years after diagnosis.9 Different retrospective analyses have suggested that the addition of docetaxel or paclitaxel to anthracycline-containing adjuvant regimens may be of greater benefit for the treatment of TNBC than for ER-positive tumors.10 A meta-analysis of trials comparing the effects of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF, which was used in Case 2) with anthracycline-containing regimens has suggested that the latter therapy regimen is more effective against TNBC,11 although another retrospective analysis of a separate trial suggested the opposite for basal-like breast cancers. 12 The authors of the latter analysis concluded that anthracycline-containing adjuvant chemotherapy regimens are inferior to adjuvant CMF in women with basal breast cancer.12

Miller and colleagues have shown that the addition of bevacizumab (angiogenesis inhibitor) to paclitaxel (used in Case 1) improved progression-free survival (median PFS, 11.8 vs 5.9 months; hazard ratio [HR] for progression, 0.60; P < .001) in women with TNBC as it did in the overall study group (HR, 0.53 and 0.60, respectively), although the overall survival rate was similar in the two groups (median OS, 26.7 vs 25.2 months; HR, 0.88; P = .16).13

An interesting clinical target in TNBC is the enzyme poly (adenosine diphosphate– ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is involved in base-excision repair after DNA damage. PARP inhibitors have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and in sporadic TNBC cancers.14 Similarly, the use of an oral PARP inhibitor, olaparib, resulted in tumor regression in up to 41% of patients carrying BRCA mutations, most of whom had TNBC.15

Conclusion

TNBC and basal-like breast cancers show aggressive clinical behavior, but a subgroup of these cancers may be markedly sensitive to chemotherapy and associated with a good prognosis when treated with conventional chemotherapy regimens. The two cases presented here show that some patients can get a prolonged disease control from chemotherapy, even after progressing on multiple previous chemotherapy regimens and that after, 5 years or so, these rare patients could be in true long-term remission. Novel approaches, for example PARP inhibitors, have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and as well as sporadic TNBC.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has been shown to generally have a poor prognosis. Within the first 3-5 years of diagnosis, the mortality rate is the highest of all the subtypes of breast cancer, although late relapses are less common.1,2 TNBC is markedly heterogeneous tumor, and the individual prognosis can vary widely.1,3 Metastatic TNBC is generally considered a noncurable disease. The median time from recurrence to death for metastatic disease is about 9 months, compared with 20 months for patients with other subtypes of breast cancers.4,5 The median survival time for patients with metastatic TNBC is about 13 months.3

New targeted therapies are emerging for breast cancer, but there are currently no effective targeted therapies for patients with TNBC. In addition, few reports in the literature that discuss long-term complete remissions in patients who have metastatic TNBC. Here, we describe two cases in which patients with metastatic TNBC achieved sustained complete response on conventional chemotherapy regimens.

Case presentations and summaries

Case 1

A 59-year-old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed on biopsy in February 2005 with locally advanced right breast cancer (stage T2N2bM0). She underwent lumpectomy, and the results of her pathology tests revealed a triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma. She was started on 4 cycles of neoadjuvant doxorubicin (60 mg/m2 IV) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2 IV)

In November 2007, the patient was found to have right chest wall metastasis confirmed by ultrasound-guided needle biopsy, and underwent right-side chest wall and partial sternum resection. In May 2008, she had recurrence in the left axilla, and biopsy results showed that she had TNBC disease. She was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) and bevacizumab (10 mg/kg every 2 weeks) continued until July 2008. Chemotherapy was stopped in July 2008 because of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection of the chest wall and was not resumed after the infection had resolved.

A follow-up positron-emission tomography– computed tomography (PET-CT) scan in June 2009, showed no evidence of disease and the scan was negative for disease in her left axilla. Another PET scan about a year later, in September 2010, was also negative for any disease recurrence.

The patient has continued her follow-up with physical examinations and imaging scans. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis (December 2010), an MRI of the breasts (February 2011, August 2015), and a PET-CT scan (April 2015, Figure 1) were all negative for any evidence of disease. In September 2011, she had a CT-guided biopsy of a medial right clavicle and costal junction lesion; and in November 2011 and January 2013, surgical biopsies of the right chest wall and first rib lesions, all negative for any evidence for malignancy. At her last follow-up in January 2017, the patient remained in remission.

Case 2

A 68-year old woman (age in 2015) had been diagnosed in Russia in 2004 with infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the right breast (T4N1M0; receptor status unknown at that time). She underwent a right modified radical mastectomy and received adjuvant chemotherapy with 4 cycles of cyclophosphamide (100 mg/m2 day 1 to day 14), methotrexate (40 mg/m2 IV day 1 and day 8), and fluorouracil (600 mg/m2 IV, day 1 and day 8) followed by 2 cycles of docetaxel (75 mg/m2 IV) and anthracycline adriyamycin (50 mg/m2 IV). The patient later received radiation therapy (radiation dose not known, treatment was received in Russia), and completed her treatment in November 2004.

The patient moved to the United States and was started on 25 mg daily exemestane in February 2005. In March 2009, she was diagnosed by biopsy to have recurrence in her internal mammary and hilar lymph nodes and sternum. The cancer was found to be ER- and PR-negative and HER2-neu–negative. The patient was treated with radiation therapy (37.5 Gy in 15 fractions) to sternum and hilar and internal mammary lymph nodes with improvement in pain and shrinkage of lymph nodes size. In May 2009, she was started on 1,500 mg oral twice a day capecitabine (3 cycles). The therapy was started after completion of radiation treatment due to progression of disease. She developed hand-and-foot syndrome as side effect of the capecitabine, so the dose was reduced. She was switched to gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle) as a single-agent therapy and completed 3 cycles. A follow-up PET-CT scan in February 2010 showed no evidence of disease.

In May 2010, the patient had a recurrence in the same metastatic foci as before, and she was again started on gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15, every 28-day cycle). She continued gemcitabine until there was evidence of disease progression on a PET-CT scan in October 2010, which showed new areas of disease in the left parasternal region, left sternum, prevascular mediastinal nodes, and left supraclavicular, hilar and axillary adenopathy, and fourth thoracic vertebra. Gemcitabine was discontinued and patient was started on weekly paclitaxel (90 mg/m2) for 6 cycles. Paclitaxel was discontinued after 6 weeks because she developed a drug-related rash. A follow-up PET-CT scan in December 2010 again showed complete resolution of disease in terms of response.

In March 2011, PET imaging showed progression of disease in the left chest wall and axillary lymph nodes, so the patient was started on eribulin therapy (1.4 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 21-day cycle) and completed 3 cycles. In May 2011, PET imaging showed complete response to treatment with no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease. The patient has not had chemotherapy since November 2011, and surveillance PET imaging has not demonstrated any recurrence of disease (Figure 2). Following her last follow-up in November 2016, the patient remains in remission.

Discussion

Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) are defined as tumors that lack expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2, and represent about 12%-17% of breast cancer cases.1,6 TNBCs tend to be larger in size at diagnosis than are other subtypes, are usually high-grade (poorly differentiated), and are more likely to be invasive ductal carcinomas.1,7 TNBC and the basal-like breast cancers as a group are associated with an adverse prognosis.1,7 There is no standard preferred chemotherapy and no biologic therapy available for TNBC.1,6-7 A sharp decline in survival outcome during the first 3-5 years after diagnosis initial is observed in TNBC, although the distant relapses after this time are less common.1 Beyond 10 years from diagnosis, the relapses are seen more common among patients with ER-positive cancers than among those with ER-negative subtype cancers. Therefore, although TNBCs are biologically aggressive, many are possibly curable, and this reflects their interesting characteristic heterogeneity.1,6

Chemotherapy is currently the mainstay of systemic medical treatment. Although patients with TNBC have a worse outcome after chemotherapy than patients with breast cancers of other subtypes, it still improves their outcome to a greater extent than in patients with ER-positive subtypes.1,6,7 Considering the heterogeneity of TNBC, it is difficult to predict which patients will benefit more from chemotherapy. The same has been observed in previous studies when subgroups of women with TNBC were extremely sensitive to chemotherapy, whereas in others it was of uncertain benefit.1

Currently, there is no preferred standard form of chemotherapy for TNBC. There are few case reports that demonstrate long-term survival and complete remission in metastatic TNBC. Shakir has reported on a significant clinical response to nab-paclitaxel monotherapy in a patient with triple-negative BRCA1-positive breast cancer, although patient survived a little more than 5 years and died with central nervous system recurrence.8 Montero and Gluck have described a patient with metastatic TNBC who was treated with nab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, and bevacizumab and who also survived for 5 years after diagnosis.9 Different retrospective analyses have suggested that the addition of docetaxel or paclitaxel to anthracycline-containing adjuvant regimens may be of greater benefit for the treatment of TNBC than for ER-positive tumors.10 A meta-analysis of trials comparing the effects of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF, which was used in Case 2) with anthracycline-containing regimens has suggested that the latter therapy regimen is more effective against TNBC,11 although another retrospective analysis of a separate trial suggested the opposite for basal-like breast cancers. 12 The authors of the latter analysis concluded that anthracycline-containing adjuvant chemotherapy regimens are inferior to adjuvant CMF in women with basal breast cancer.12

Miller and colleagues have shown that the addition of bevacizumab (angiogenesis inhibitor) to paclitaxel (used in Case 1) improved progression-free survival (median PFS, 11.8 vs 5.9 months; hazard ratio [HR] for progression, 0.60; P < .001) in women with TNBC as it did in the overall study group (HR, 0.53 and 0.60, respectively), although the overall survival rate was similar in the two groups (median OS, 26.7 vs 25.2 months; HR, 0.88; P = .16).13

An interesting clinical target in TNBC is the enzyme poly (adenosine diphosphate– ribose) polymerase (PARP), which is involved in base-excision repair after DNA damage. PARP inhibitors have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and in sporadic TNBC cancers.14 Similarly, the use of an oral PARP inhibitor, olaparib, resulted in tumor regression in up to 41% of patients carrying BRCA mutations, most of whom had TNBC.15

Conclusion

TNBC and basal-like breast cancers show aggressive clinical behavior, but a subgroup of these cancers may be markedly sensitive to chemotherapy and associated with a good prognosis when treated with conventional chemotherapy regimens. The two cases presented here show that some patients can get a prolonged disease control from chemotherapy, even after progressing on multiple previous chemotherapy regimens and that after, 5 years or so, these rare patients could be in true long-term remission. Novel approaches, for example PARP inhibitors, have shown encouraging clinical activity in trials of tumors arising in BRCA mutation carriers and as well as sporadic TNBC.

1. Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS, Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938-1948.

2. Pogoda K, Niwińska A, Murawska M, Pieńkowski T. Analysis of pattern, time and risk factors influencing recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):388.

3. Kassam F, Enright K, Dent R, et al. Survival outcomes for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: implications for clinical practice and trial design. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(1):29-33.

4. Perou CM. Molecular stratification of triple-negative breast cancers. Oncologist. 2010;15(suppl 5):39-48.

5. Rakha EA, Chan S. Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011;23(9):587-600.

6. Williams N, Harris L. Triple-negative breast cancer in the post-genomic era. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(9):859-860, 864.

7. Randhawa SK, Venur VA, Kawsar H, et al. A retrospective comparison of the characteristics and recurrence outcome of triple-negative and triple-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl; abstr 1038).

8. Shakir AR. Strong and sustained response to treatment with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel in a patient with metastatic, triple-negative, BRCA1-positive breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7(1)252-259.

9. Montero A, Glück S. Long-term complete remission with nab-paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and gemcitabine combination therapy in a patient with triple-negative metastatic breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5(3):687-692.

10. Hayes DF, Thor AD, Dressler LG, et al. HER2 and response to paclitaxel in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1496-1506.

11. Di Leo A, Isola J, Piette F, et al. A meta- analysis of phase III trials evaluating the predictive value of HER2 and topoisomerase alpha in early breast cancer patients treated with CMF or anthracycline-based adjuvant therapy [SABCS, abstract 705]. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/69/2_Supplement/705. Published 2008. Accessed May 4, 2017.

12. Cheang M, Chia SK, Tu D, et al. Anthracycline in basal breast cancer: the NCIC-CTG trial MA5 comparing adjuvant CMF to CEF [ASCO; abstract 519]. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/35150-65. Published 2009. Accessed May 4, 2017.

13. Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666-2676.

14. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123-134.

15. Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235-244.

1. Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS, Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938-1948.

2. Pogoda K, Niwińska A, Murawska M, Pieńkowski T. Analysis of pattern, time and risk factors influencing recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):388.

3. Kassam F, Enright K, Dent R, et al. Survival outcomes for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: implications for clinical practice and trial design. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(1):29-33.

4. Perou CM. Molecular stratification of triple-negative breast cancers. Oncologist. 2010;15(suppl 5):39-48.

5. Rakha EA, Chan S. Metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2011;23(9):587-600.

6. Williams N, Harris L. Triple-negative breast cancer in the post-genomic era. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(9):859-860, 864.

7. Randhawa SK, Venur VA, Kawsar H, et al. A retrospective comparison of the characteristics and recurrence outcome of triple-negative and triple-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl; abstr 1038).

8. Shakir AR. Strong and sustained response to treatment with carboplatin plus nab-paclitaxel in a patient with metastatic, triple-negative, BRCA1-positive breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7(1)252-259.

9. Montero A, Glück S. Long-term complete remission with nab-paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and gemcitabine combination therapy in a patient with triple-negative metastatic breast cancer. Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5(3):687-692.

10. Hayes DF, Thor AD, Dressler LG, et al. HER2 and response to paclitaxel in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1496-1506.

11. Di Leo A, Isola J, Piette F, et al. A meta- analysis of phase III trials evaluating the predictive value of HER2 and topoisomerase alpha in early breast cancer patients treated with CMF or anthracycline-based adjuvant therapy [SABCS, abstract 705]. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/69/2_Supplement/705. Published 2008. Accessed May 4, 2017.

12. Cheang M, Chia SK, Tu D, et al. Anthracycline in basal breast cancer: the NCIC-CTG trial MA5 comparing adjuvant CMF to CEF [ASCO; abstract 519]. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/35150-65. Published 2009. Accessed May 4, 2017.

13. Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666-2676.

14. Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123-134.

15. Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235-244.

Breast density and optimal screening for breast cancer

MY STORY: Prologue

My aunt received a breast cancer diagnosis at age 40, and she died at age 60, in 1970. Then, in 1975, my mother’s breast cancer was found at age 55, but only after she was examined for nipple retraction; on mammography, the cancer had been obscured by dense breast tissue. Mom had 2 metastatic nodes but participated in the earliest clinical trials of chemotherapy and lived free of breast cancer for another 41 years. Naturally I thought that, were I to develop this disease, I would want it found earlier. Ironically, it was, but only because I had spent my career trying to understand the optimal screening approaches for women with dense breasts—women like me.

Cancers are masked on mammography in dense breasts

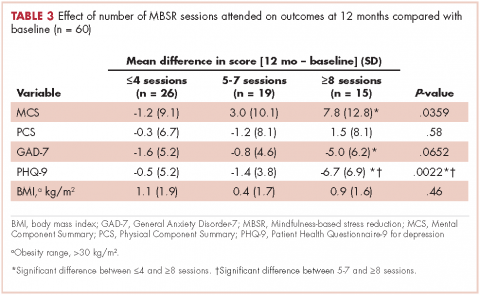

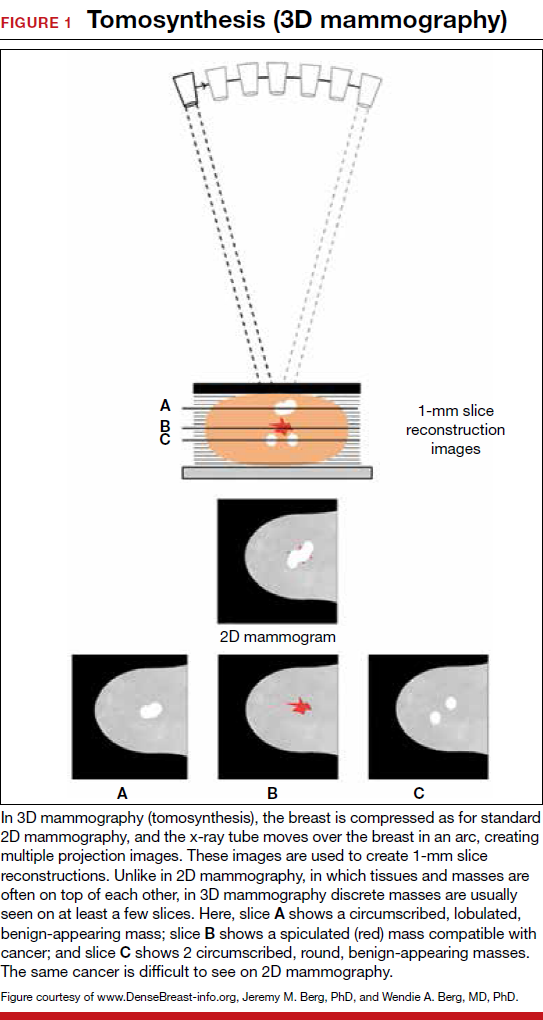

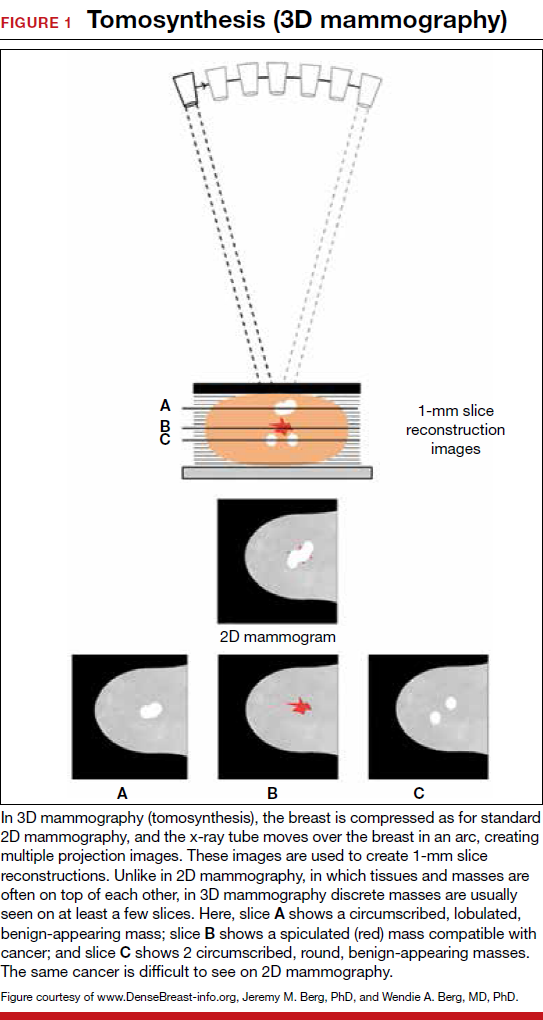

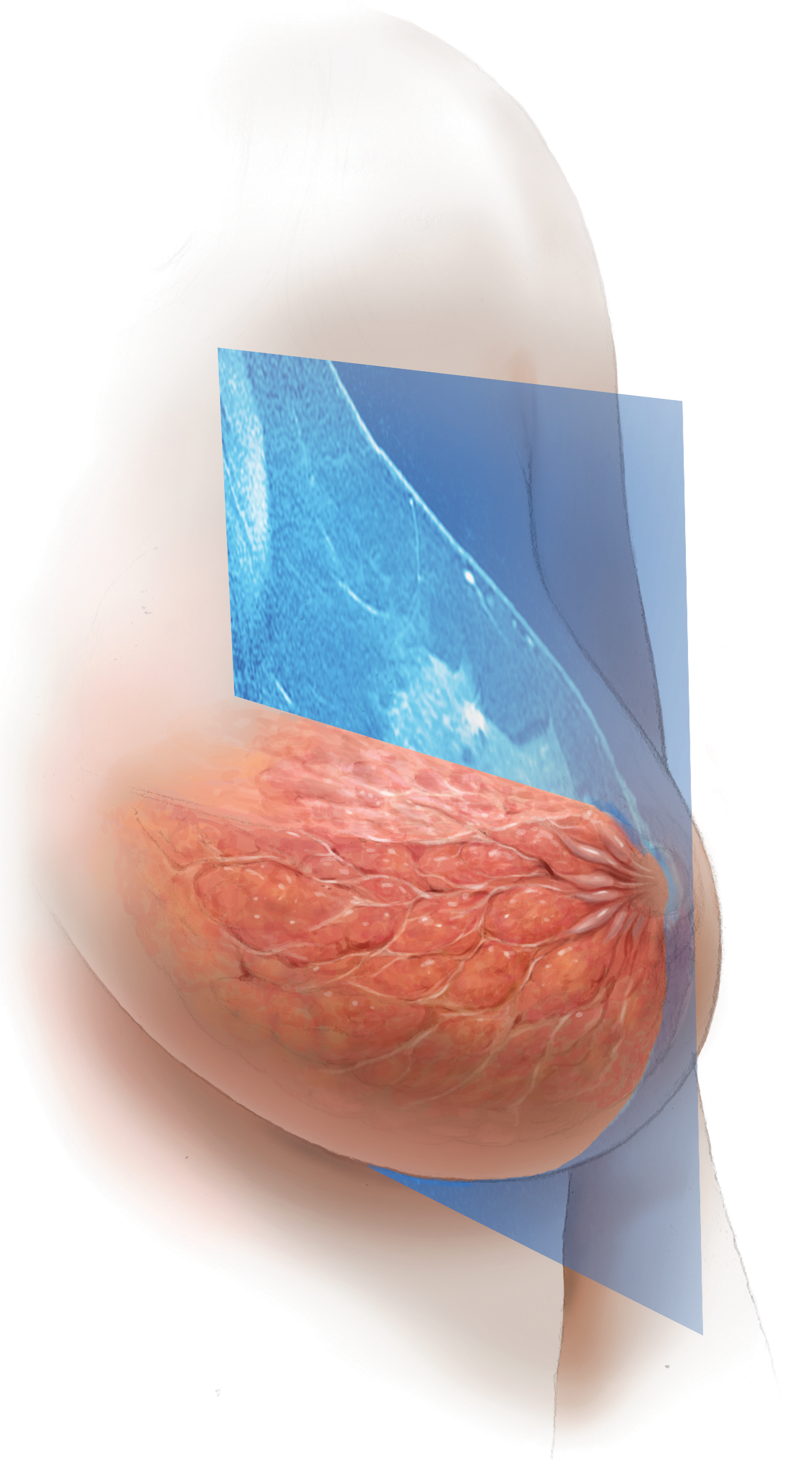

For women, screening mammography is an important step in reducing the risk of dying from breast cancer. The greatest benefits are realized by those who start annual screening at age 40, or 45 at the latest.1 As it takes 9 to 10 years to see a benefit from breast cancer screening at the population level, it is not logical to continue this testing when life expectancy is less than 10 years, as is the case with women age 85 or older, even those in the healthiest quartile.2–4 However, despite recent advances, the development of 3D mammography (tomosynthesis) (FIGURE 1) in particular, cancers can still be masked by dense breast tissue. Both 2D and 3D mammograms are x-rays; both dense tissue and cancers absorb x-rays and appear white.

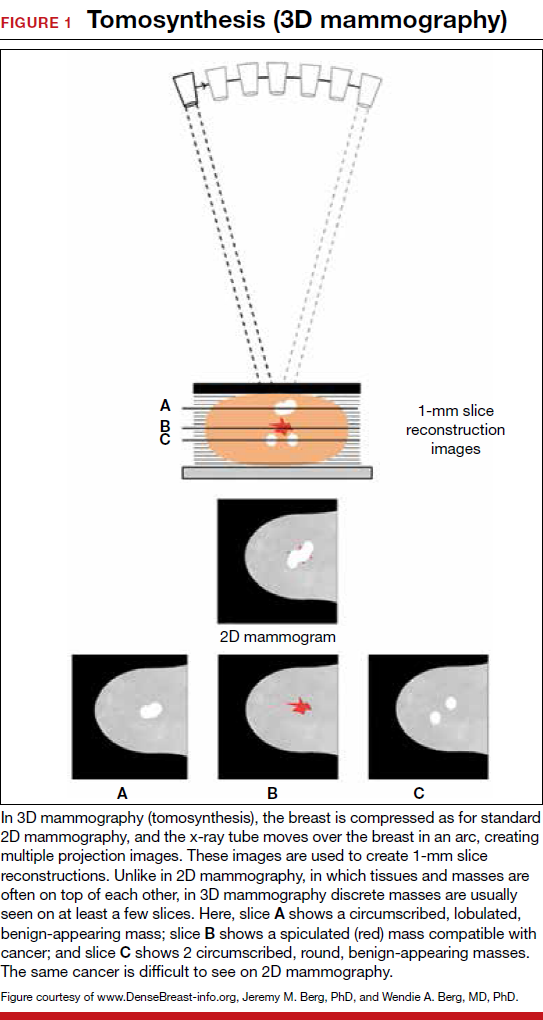

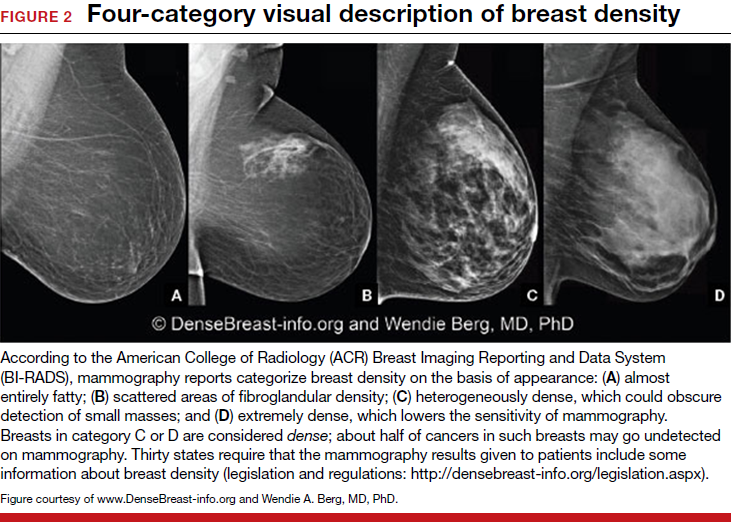

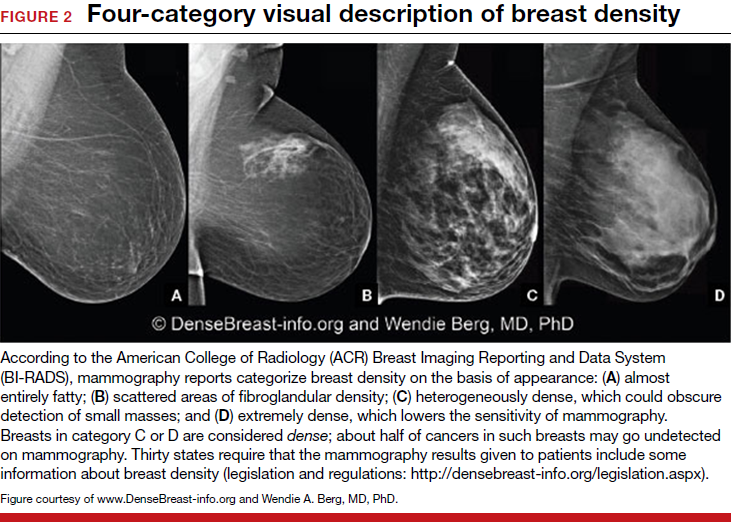

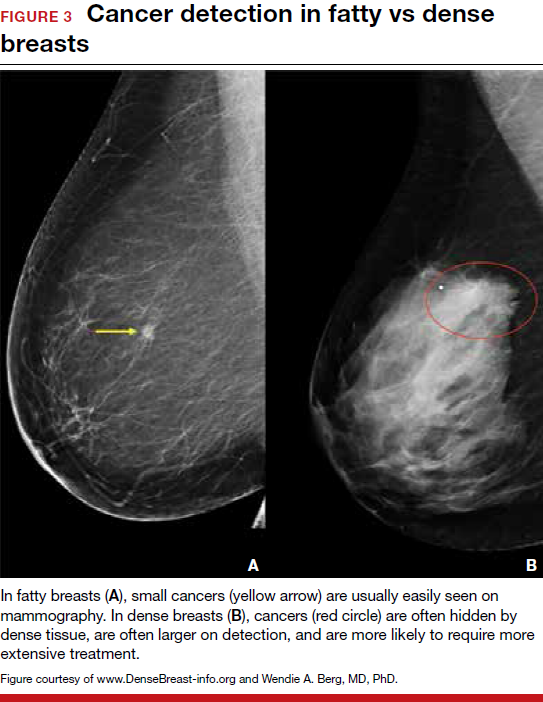

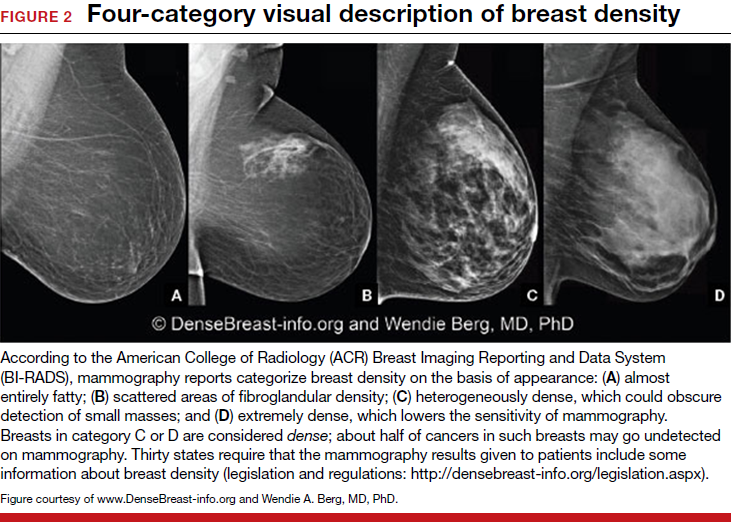

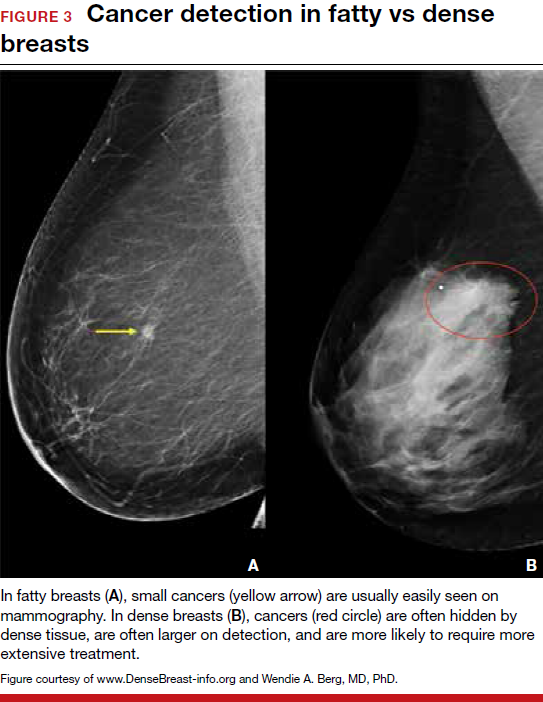

Breast density is determined on mammography and is categorized as fatty, scattered fibroglandular, heterogeneously dense, or extremely dense (FIGURE 2).5 Tissue in the heterogeneous and extreme categories is considered dense. More than half of women in their 40s have dense breasts; with some fatty involution occurring around menopause, the proportion drops to 25% for women in their 60s.6 About half of breast cancers have calcifications, which on mammography are usually easily visible even in dense breasts. The problem is with noncalcified invasive cancers that can be hidden by dense tissue (FIGURE 3).

3D mammography improves cancer detection but is of minimal benefit in extremely dense breasts

Although 3D mammography improves cancer detection in most women, any benefit is minimal in women with extremely dense breasts, as there is no inherent soft-tissue contrast.7 Masked cancers are often only discovered because of a lump after a normal screening mammogram, as so-called “interval cancers.” Compared with screen-detected cancers, interval cancers tend to be more biologically aggressive, to have spread to lymph nodes, and to have worse prognoses. However, even some small screen-detected cancers are biologically aggressive and can spread to lymph nodes quickly, and no screening test or combination of screening tests can prevent this occurrence completely, regardless of breast density.

Related article:

Get smart about dense breasts

MRI provides early detection across all breast densities

In all tissue densities, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is far better than mammography in detecting breast cancer.8 Women at high risk for breast cancer caused by mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, p53, and other genes have poor outcomes with screening mammography alone—up to 50% of cancers are interval cancers. Annual screening MRI reduces this percentage significantly, to 11% in women with pathogenic BRCA1 mutations and to 4% in women with BRCA2 mutations.9 Warner and colleagues found a decrease in late-stage cancers in high-risk women who underwent annual MRI screenings compared to high-risk women unable to have MRI.10

The use of MRI for screening is limited by availability, patient tolerance,11 and high cost. Research is being conducted to further validate approaches using shortened screening MRI times (so-called “abbreviated” or “fast” MRI) and, thereby, improve access, tolerance, and reduce associated costs; several investigators already have reported promising results, and a few centers offer this modality directly to patients willing to pay $300 to $350 out of pocket.12,13 Even in normal-risk women, MRI significantly increases detection of early breast cancer after a normal mammogram and ultrasound, and the cancer detection benefit of MRI is seen across all breast densities.14

Most health insurance plans cover screening MRI only for women who meet defined risk criteria, including women who have a known disease-causing mutation—or are suspected of having one, given a family history of breast cancer with higher than 20% to 25% lifetime risk by a model that predicts mutation carrier status—as well as women who had chest radiation therapy before age 30, typically for Hodgkin lymphoma, and at least 8 years earlier.15 In addition, MRI can be considered in women with atypical breast biopsy results or a personal history of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS).16

Screening MRI should start by age 25 in women with disease-causing mutations, or at the time of atypical or LCIS biopsy results, and should be performed annually unless the woman is pregnant or has a metallic implant, renal insufficiency, or another contraindication to MRI. MRI can be beneficial in women with a personal history of cancer, although annual mammography remains the standard of care.17–19

MRI and mammography can be performed at the same time or on an alternating 6-month basis, with mammography usually starting only after age 30 because of the small risk that radiation poses for younger women. There are a few other impediments to having breast MRI: The woman must lie on her stomach within a confined space (tunnel), the contrast that is injected may not be well tolerated, and insurance does not cover the test for women who do not meet the defined risk criteria.11

Read why mammography supplemented by US is best for women with dense breasts.

Ultrasonography supplements mammography

Mammography supplemented with ultrasonography (US) has been studied as a “Goldilocks” or best-fit solution for the screening of women with dense breasts, as detection of invasive cancers is improved with the 2 modalities over mammography alone, and US is less invasive, better tolerated, and lower in cost than the more sensitive MRI.

In women with dense breasts, US has been found to improve cancer detection over mammography alone, and early results suggest a larger cancer detection benefit from US than from 3D mammography, although research is ongoing.20 Adding US reduces the interval cancer rate in women with dense breasts to less than 10% of all cancers found—similar to results for women with fatty breasts.17,21,22

US can be performed by a trained technologist or a physician using a small transducer, which usually provides diagnostic images (so that most callbacks would be for a true finding), or a larger transducer and an automated system can be used to create more than a thousand images for radiologist review.23,24 Use of a hybrid system, a small transducer with an automated arm, has been validated as well.25 Screening US is not available universally, and with all these approaches optimal performance requires trained personnel. Supplemental screening US usually is covered by insurance but is nearly always subject to a deductible/copay.

Related article:

Educate patients about dense breasts and cancer risk

Reducing false-positives, callbacks, and additional testing

Mammography carries a risk of false-positives. On average, 11% to 12% of women are called back for additional testing after a screening mammogram, and in more than 95% of women brought back for extra testing, no cancer is found.26 Women with dense breasts are more likely than those with less dense breasts to be called back.27 US and MRI improve cancer detection and therefore yield additional positive, but also false-positive, findings. Notably, callbacks decrease after the first round of screening with any modality or combination of tests, as long as prior examinations are available for comparison.

One advantage of 3D over 2D mammography is a decrease in extra testing for areas of asymmetry, which are often recognizable on 3D mammography as representing normal superimposed tissue.28–30 Architectural distortion, which is better seen on 3D mammography and usually represents either cancer or a benign radial scar, can lead to false-positive biopsies, although the average biopsy rate is no higher for 3D than for 2D alone.31 Typically, the 3D and 2D examinations are performed together (slightly more than doubling the radiation dose), or synthetic 2D images can be created from the 3D slices (resulting in a total radiation dose almost the same as standard 2D alone).

Most additional cancers seen on 3D mammography or US are lower-grade invasive cancers with good prognoses. Some aggressive high-grade breast cancers go undetected even when mammography is supplemented with US, either because they are too small to be seen or because they resemble common benign masses and may not be recognized. MRI is particularly effective in depicting high-grade cancers, even small ones.

The TABLE summarizes the relative rates of cancer detection and additional testing by various breast screening tests or combinations of tests. Neither clinical breast examination by a physician or other health care professional nor routine breast self-examination reduces the number of deaths caused by breast cancer. Nevertheless, women should monitor any changes in their breasts and report these changes to their clinician. A new lump, skin or nipple retraction, or a spontaneous clear or bloody nipple discharge merits diagnostic breast imaging even if a recent screening mammogram was normal.

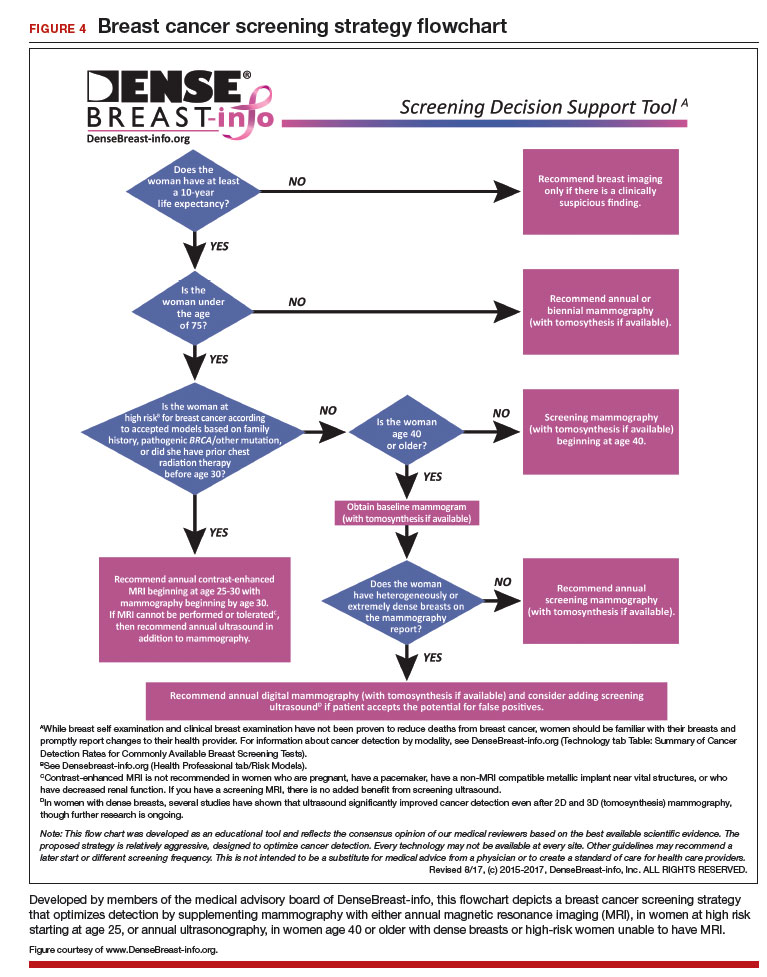

FIGURE 4 is an updated decision support tool that suggests strategies for optimizingcancer detection with widely available screening methods.

Read how to take advantage of today’s technology for breast density screening

MY STORY: Epilogue

My annual 3D mammograms were normal, even the year my cancer was present. In 2014, I entered my family history into the IBIS Breast Cancer Risk Evaluation Tool (Tyrer-Cuzick model of breast cancer risk) (http://www.ems-trials.org/riskevaluator/) and calculated my lifetime risk at 19.7%. That is when I decided to have a screening MRI. My invasive breast cancer was easily seen on MRI and then on US. The cancer was node-negative, easily confirmed with needle biopsy, and treated with lumpectomy and radiation. There was no need for chemotherapy.

My personal experience prompted me to join JoAnn Pushkin and Cindy Henke-Sarmento, RT(R)(M), BA, in developing a website, www.DenseBreast-info.org, to give women and their physicians easy access to information on making decisions about screening in dense breasts.

My colleagues and I are often asked what is the best way to order supplemental imaging for a patient who may have dense breasts. Even in cases in which a mammogram does not exist or is unavailable, the following prescription can be implemented easily at centers that offer US: “2D plus 3D mammogram if available; if dense, perform ultrasound as needed.”

Related article:

DenseBreast-info.org: What this resource can offer you, and your patients

Breast density screening: Take advantage of today’s technology

Breast screening and diagnostic imaging have improved significantly since the 1970s, when many of the randomized trials of mammography were conducted. Breast density is one of the most common and important risk factors for development of breast cancer and is now incorporated into the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium model (https://tools.bcsc-scc.org/BC5yearRisk/calculator.htm) and the Tyrer-Cuzick model (see also http://densebreast-info.org/explanation-of-dense-breast-risk-models.aspx).32 Although we continue to validate newer approaches, women should take advantage of the improved methods of early cancer detection, particularly if they have dense breasts or are at high risk for breast cancer.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614.

- Tabar L, Yen MF, Vitak B, Chen HH, Smith RA, Duffy SW. Mammography service screening and mortality in breast cancer patients: 20-year follow-up before and after introduction of screening. Lancet. 2003;361(9367):1405–1410.

- Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Conell-Price J, O’Brien S, Walter LC. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ. 2013;346:e8441.

- Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750–2756.

- Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, et al. ACR BI-RADS mammography. In: D’Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, et al, eds. ACR BI-RADS Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. 5th ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

- Sprague BL, Gangnon RE, Burt V, et al. Prevalence of mammographically dense breasts in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(10).

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1784–1786.

- Berg WA. Tailored supplemental screening for breast cancer: what now and what next? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(2):390–399.

- Heijnsdijk EA, Warner E, Gilbert FJ, et al. Differences in natural history between breast cancers in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers and effects of MRI screening—MRISC, MARIBS, and Canadian studies combined. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(9):1458–1468.

- Warner E, Hill K, Causer P, et al. Prospective study of breast cancer incidence in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation under surveillance with and without magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(13):1664–1669.

- Berg WA, Blume JD, Adams AM, et al. Reasons women at elevated risk of breast cancer refuse breast MR imaging screening: ACRIN 6666. Radiology. 2010;254(1):79–87.

- Kuhl CK, Schrading S, Strobel K, Schild HH, Hilgers RD, Bieling HB. Abbreviated breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): first postcontrast subtracted images and maximum-intensity projection—a novel approach to breast cancer screening with MRI. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(22):2304–2310.

- Strahle DA, Pathak DR, Sierra A, Saha S, Strahle C, Devisetty K. Systematic development of an abbreviated protocol for screening breast magnetic resonance imaging. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;162(2):283–295.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, Leutner C, Schild HH, Schrading S. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283(2):361–370.

- Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al; American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(2):75–89.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN guidelines for detection, prevention, and risk reduction: breast cancer screening and diagnosis. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf.

- Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, et al; ACRIN 6666 Investigators. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1394–1404.

- Brennan S, Liberman L, Dershaw DD, Morris E. Breast MRI screening of women with a personal history of breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(2):510–516.

- Lehman CD, Lee JM, DeMartini WB, et al. Screening MRI in women with a personal history of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(3).

- Tagliafico AS, Calabrese M, Mariscotti G, et al. Adjunct screening with tomosynthesis or ultrasound in women with mammography-negative dense breasts: interim report of a prospective comparative trial [published online ahead of print March 9, 2016]. J Clin Oncol. JCO634147.

- Corsetti V, Houssami N, Ghirardi M, et al. Evidence of the effect of adjunct ultrasound screening in women with mammography-negative dense breasts: interval breast cancers at 1 year follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(7):1021–1026.

- Ohuchi N, Suzuki A, Sobue T, et al; J-START Investigator Groups. Sensitivity and specificity of mammography and adjunctive ultrasonography to screen for breast cancer in the Japan Strategic Anti-Cancer Randomized Trial (J-START): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10016):341–348.

- Berg WA, Mendelson EB. Technologist-performed handheld screening breast US imaging: how is it performed and what are the outcomes to date? Radiology. 2014;272(1):12–27.

- Brem RF, Tabár L, Duffy SW, et al. Assessing improvement in detection of breast cancer with three-dimensional automated breast US in women with dense breast tissue: the SomoInsight study. Radiology. 2015;274(3):663–673.

- Kelly KM, Dean J, Comulada WS, Lee SJ. Breast cancer detection using automated whole breast ultrasound and mammography in radiographically dense breasts. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(3):734–742.

- Lehman CD, Arao RF, Sprague BL, et al. National performance benchmarks for modern screening digital mammography: update from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Radiology. 2017;283(1):49–58.

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Hubbard RA, et al; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Outcomes of screening mammography by frequency, breast density, and postmenopausal hormone therapy. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(9):807–816.

- Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499–2507.

- Skaane P, Bandos AI, Gullien R, et al. Comparison of digital mammography alone and digital mammography plus tomosynthesis in a population-based screening program. Radiology. 2013;267(1):47–56.

- Ciatto S, Houssami N, Bernardi D, et al. Integration of 3D digital mammography with tomosynthesis for population breast-cancer screening (STORM): a prospective comparison study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):583–589.

- Bahl M, Lamb LR, Lehman CD. Pathologic outcomes of architectural distortion on digital 2D versus tomosynthesis mammography [published online ahead of print August 23, 2017]. AJR Am J Roentgenol. doi:10.2214/AJR.17.17979.

- Engmann NJ, Golmakani MK, Miglioretti DL, Sprague BL, Kerlikowske K; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Population-attributable risk proportion of clinical risk factors for breast cancer [published online ahead of print February 2, 2017]. JAMA Oncol. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6326.

MY STORY: Prologue

My aunt received a breast cancer diagnosis at age 40, and she died at age 60, in 1970. Then, in 1975, my mother’s breast cancer was found at age 55, but only after she was examined for nipple retraction; on mammography, the cancer had been obscured by dense breast tissue. Mom had 2 metastatic nodes but participated in the earliest clinical trials of chemotherapy and lived free of breast cancer for another 41 years. Naturally I thought that, were I to develop this disease, I would want it found earlier. Ironically, it was, but only because I had spent my career trying to understand the optimal screening approaches for women with dense breasts—women like me.

Cancers are masked on mammography in dense breasts

For women, screening mammography is an important step in reducing the risk of dying from breast cancer. The greatest benefits are realized by those who start annual screening at age 40, or 45 at the latest.1 As it takes 9 to 10 years to see a benefit from breast cancer screening at the population level, it is not logical to continue this testing when life expectancy is less than 10 years, as is the case with women age 85 or older, even those in the healthiest quartile.2–4 However, despite recent advances, the development of 3D mammography (tomosynthesis) (FIGURE 1) in particular, cancers can still be masked by dense breast tissue. Both 2D and 3D mammograms are x-rays; both dense tissue and cancers absorb x-rays and appear white.

Breast density is determined on mammography and is categorized as fatty, scattered fibroglandular, heterogeneously dense, or extremely dense (FIGURE 2).5 Tissue in the heterogeneous and extreme categories is considered dense. More than half of women in their 40s have dense breasts; with some fatty involution occurring around menopause, the proportion drops to 25% for women in their 60s.6 About half of breast cancers have calcifications, which on mammography are usually easily visible even in dense breasts. The problem is with noncalcified invasive cancers that can be hidden by dense tissue (FIGURE 3).

3D mammography improves cancer detection but is of minimal benefit in extremely dense breasts

Although 3D mammography improves cancer detection in most women, any benefit is minimal in women with extremely dense breasts, as there is no inherent soft-tissue contrast.7 Masked cancers are often only discovered because of a lump after a normal screening mammogram, as so-called “interval cancers.” Compared with screen-detected cancers, interval cancers tend to be more biologically aggressive, to have spread to lymph nodes, and to have worse prognoses. However, even some small screen-detected cancers are biologically aggressive and can spread to lymph nodes quickly, and no screening test or combination of screening tests can prevent this occurrence completely, regardless of breast density.

Related article:

Get smart about dense breasts

MRI provides early detection across all breast densities

In all tissue densities, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is far better than mammography in detecting breast cancer.8 Women at high risk for breast cancer caused by mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, p53, and other genes have poor outcomes with screening mammography alone—up to 50% of cancers are interval cancers. Annual screening MRI reduces this percentage significantly, to 11% in women with pathogenic BRCA1 mutations and to 4% in women with BRCA2 mutations.9 Warner and colleagues found a decrease in late-stage cancers in high-risk women who underwent annual MRI screenings compared to high-risk women unable to have MRI.10

The use of MRI for screening is limited by availability, patient tolerance,11 and high cost. Research is being conducted to further validate approaches using shortened screening MRI times (so-called “abbreviated” or “fast” MRI) and, thereby, improve access, tolerance, and reduce associated costs; several investigators already have reported promising results, and a few centers offer this modality directly to patients willing to pay $300 to $350 out of pocket.12,13 Even in normal-risk women, MRI significantly increases detection of early breast cancer after a normal mammogram and ultrasound, and the cancer detection benefit of MRI is seen across all breast densities.14

Most health insurance plans cover screening MRI only for women who meet defined risk criteria, including women who have a known disease-causing mutation—or are suspected of having one, given a family history of breast cancer with higher than 20% to 25% lifetime risk by a model that predicts mutation carrier status—as well as women who had chest radiation therapy before age 30, typically for Hodgkin lymphoma, and at least 8 years earlier.15 In addition, MRI can be considered in women with atypical breast biopsy results or a personal history of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS).16

Screening MRI should start by age 25 in women with disease-causing mutations, or at the time of atypical or LCIS biopsy results, and should be performed annually unless the woman is pregnant or has a metallic implant, renal insufficiency, or another contraindication to MRI. MRI can be beneficial in women with a personal history of cancer, although annual mammography remains the standard of care.17–19

MRI and mammography can be performed at the same time or on an alternating 6-month basis, with mammography usually starting only after age 30 because of the small risk that radiation poses for younger women. There are a few other impediments to having breast MRI: The woman must lie on her stomach within a confined space (tunnel), the contrast that is injected may not be well tolerated, and insurance does not cover the test for women who do not meet the defined risk criteria.11

Read why mammography supplemented by US is best for women with dense breasts.

Ultrasonography supplements mammography

Mammography supplemented with ultrasonography (US) has been studied as a “Goldilocks” or best-fit solution for the screening of women with dense breasts, as detection of invasive cancers is improved with the 2 modalities over mammography alone, and US is less invasive, better tolerated, and lower in cost than the more sensitive MRI.

In women with dense breasts, US has been found to improve cancer detection over mammography alone, and early results suggest a larger cancer detection benefit from US than from 3D mammography, although research is ongoing.20 Adding US reduces the interval cancer rate in women with dense breasts to less than 10% of all cancers found—similar to results for women with fatty breasts.17,21,22

US can be performed by a trained technologist or a physician using a small transducer, which usually provides diagnostic images (so that most callbacks would be for a true finding), or a larger transducer and an automated system can be used to create more than a thousand images for radiologist review.23,24 Use of a hybrid system, a small transducer with an automated arm, has been validated as well.25 Screening US is not available universally, and with all these approaches optimal performance requires trained personnel. Supplemental screening US usually is covered by insurance but is nearly always subject to a deductible/copay.

Related article:

Educate patients about dense breasts and cancer risk

Reducing false-positives, callbacks, and additional testing

Mammography carries a risk of false-positives. On average, 11% to 12% of women are called back for additional testing after a screening mammogram, and in more than 95% of women brought back for extra testing, no cancer is found.26 Women with dense breasts are more likely than those with less dense breasts to be called back.27 US and MRI improve cancer detection and therefore yield additional positive, but also false-positive, findings. Notably, callbacks decrease after the first round of screening with any modality or combination of tests, as long as prior examinations are available for comparison.

One advantage of 3D over 2D mammography is a decrease in extra testing for areas of asymmetry, which are often recognizable on 3D mammography as representing normal superimposed tissue.28–30 Architectural distortion, which is better seen on 3D mammography and usually represents either cancer or a benign radial scar, can lead to false-positive biopsies, although the average biopsy rate is no higher for 3D than for 2D alone.31 Typically, the 3D and 2D examinations are performed together (slightly more than doubling the radiation dose), or synthetic 2D images can be created from the 3D slices (resulting in a total radiation dose almost the same as standard 2D alone).

Most additional cancers seen on 3D mammography or US are lower-grade invasive cancers with good prognoses. Some aggressive high-grade breast cancers go undetected even when mammography is supplemented with US, either because they are too small to be seen or because they resemble common benign masses and may not be recognized. MRI is particularly effective in depicting high-grade cancers, even small ones.

The TABLE summarizes the relative rates of cancer detection and additional testing by various breast screening tests or combinations of tests. Neither clinical breast examination by a physician or other health care professional nor routine breast self-examination reduces the number of deaths caused by breast cancer. Nevertheless, women should monitor any changes in their breasts and report these changes to their clinician. A new lump, skin or nipple retraction, or a spontaneous clear or bloody nipple discharge merits diagnostic breast imaging even if a recent screening mammogram was normal.

FIGURE 4 is an updated decision support tool that suggests strategies for optimizingcancer detection with widely available screening methods.

Read how to take advantage of today’s technology for breast density screening

MY STORY: Epilogue

My annual 3D mammograms were normal, even the year my cancer was present. In 2014, I entered my family history into the IBIS Breast Cancer Risk Evaluation Tool (Tyrer-Cuzick model of breast cancer risk) (http://www.ems-trials.org/riskevaluator/) and calculated my lifetime risk at 19.7%. That is when I decided to have a screening MRI. My invasive breast cancer was easily seen on MRI and then on US. The cancer was node-negative, easily confirmed with needle biopsy, and treated with lumpectomy and radiation. There was no need for chemotherapy.

My personal experience prompted me to join JoAnn Pushkin and Cindy Henke-Sarmento, RT(R)(M), BA, in developing a website, www.DenseBreast-info.org, to give women and their physicians easy access to information on making decisions about screening in dense breasts.

My colleagues and I are often asked what is the best way to order supplemental imaging for a patient who may have dense breasts. Even in cases in which a mammogram does not exist or is unavailable, the following prescription can be implemented easily at centers that offer US: “2D plus 3D mammogram if available; if dense, perform ultrasound as needed.”

Related article:

DenseBreast-info.org: What this resource can offer you, and your patients

Breast density screening: Take advantage of today’s technology

Breast screening and diagnostic imaging have improved significantly since the 1970s, when many of the randomized trials of mammography were conducted. Breast density is one of the most common and important risk factors for development of breast cancer and is now incorporated into the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium model (https://tools.bcsc-scc.org/BC5yearRisk/calculator.htm) and the Tyrer-Cuzick model (see also http://densebreast-info.org/explanation-of-dense-breast-risk-models.aspx).32 Although we continue to validate newer approaches, women should take advantage of the improved methods of early cancer detection, particularly if they have dense breasts or are at high risk for breast cancer.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

MY STORY: Prologue

My aunt received a breast cancer diagnosis at age 40, and she died at age 60, in 1970. Then, in 1975, my mother’s breast cancer was found at age 55, but only after she was examined for nipple retraction; on mammography, the cancer had been obscured by dense breast tissue. Mom had 2 metastatic nodes but participated in the earliest clinical trials of chemotherapy and lived free of breast cancer for another 41 years. Naturally I thought that, were I to develop this disease, I would want it found earlier. Ironically, it was, but only because I had spent my career trying to understand the optimal screening approaches for women with dense breasts—women like me.

Cancers are masked on mammography in dense breasts

For women, screening mammography is an important step in reducing the risk of dying from breast cancer. The greatest benefits are realized by those who start annual screening at age 40, or 45 at the latest.1 As it takes 9 to 10 years to see a benefit from breast cancer screening at the population level, it is not logical to continue this testing when life expectancy is less than 10 years, as is the case with women age 85 or older, even those in the healthiest quartile.2–4 However, despite recent advances, the development of 3D mammography (tomosynthesis) (FIGURE 1) in particular, cancers can still be masked by dense breast tissue. Both 2D and 3D mammograms are x-rays; both dense tissue and cancers absorb x-rays and appear white.

Breast density is determined on mammography and is categorized as fatty, scattered fibroglandular, heterogeneously dense, or extremely dense (FIGURE 2).5 Tissue in the heterogeneous and extreme categories is considered dense. More than half of women in their 40s have dense breasts; with some fatty involution occurring around menopause, the proportion drops to 25% for women in their 60s.6 About half of breast cancers have calcifications, which on mammography are usually easily visible even in dense breasts. The problem is with noncalcified invasive cancers that can be hidden by dense tissue (FIGURE 3).

3D mammography improves cancer detection but is of minimal benefit in extremely dense breasts

Although 3D mammography improves cancer detection in most women, any benefit is minimal in women with extremely dense breasts, as there is no inherent soft-tissue contrast.7 Masked cancers are often only discovered because of a lump after a normal screening mammogram, as so-called “interval cancers.” Compared with screen-detected cancers, interval cancers tend to be more biologically aggressive, to have spread to lymph nodes, and to have worse prognoses. However, even some small screen-detected cancers are biologically aggressive and can spread to lymph nodes quickly, and no screening test or combination of screening tests can prevent this occurrence completely, regardless of breast density.

Related article:

Get smart about dense breasts

MRI provides early detection across all breast densities

In all tissue densities, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is far better than mammography in detecting breast cancer.8 Women at high risk for breast cancer caused by mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, p53, and other genes have poor outcomes with screening mammography alone—up to 50% of cancers are interval cancers. Annual screening MRI reduces this percentage significantly, to 11% in women with pathogenic BRCA1 mutations and to 4% in women with BRCA2 mutations.9 Warner and colleagues found a decrease in late-stage cancers in high-risk women who underwent annual MRI screenings compared to high-risk women unable to have MRI.10

The use of MRI for screening is limited by availability, patient tolerance,11 and high cost. Research is being conducted to further validate approaches using shortened screening MRI times (so-called “abbreviated” or “fast” MRI) and, thereby, improve access, tolerance, and reduce associated costs; several investigators already have reported promising results, and a few centers offer this modality directly to patients willing to pay $300 to $350 out of pocket.12,13 Even in normal-risk women, MRI significantly increases detection of early breast cancer after a normal mammogram and ultrasound, and the cancer detection benefit of MRI is seen across all breast densities.14

Most health insurance plans cover screening MRI only for women who meet defined risk criteria, including women who have a known disease-causing mutation—or are suspected of having one, given a family history of breast cancer with higher than 20% to 25% lifetime risk by a model that predicts mutation carrier status—as well as women who had chest radiation therapy before age 30, typically for Hodgkin lymphoma, and at least 8 years earlier.15 In addition, MRI can be considered in women with atypical breast biopsy results or a personal history of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS).16

Screening MRI should start by age 25 in women with disease-causing mutations, or at the time of atypical or LCIS biopsy results, and should be performed annually unless the woman is pregnant or has a metallic implant, renal insufficiency, or another contraindication to MRI. MRI can be beneficial in women with a personal history of cancer, although annual mammography remains the standard of care.17–19

MRI and mammography can be performed at the same time or on an alternating 6-month basis, with mammography usually starting only after age 30 because of the small risk that radiation poses for younger women. There are a few other impediments to having breast MRI: The woman must lie on her stomach within a confined space (tunnel), the contrast that is injected may not be well tolerated, and insurance does not cover the test for women who do not meet the defined risk criteria.11

Read why mammography supplemented by US is best for women with dense breasts.

Ultrasonography supplements mammography

Mammography supplemented with ultrasonography (US) has been studied as a “Goldilocks” or best-fit solution for the screening of women with dense breasts, as detection of invasive cancers is improved with the 2 modalities over mammography alone, and US is less invasive, better tolerated, and lower in cost than the more sensitive MRI.

In women with dense breasts, US has been found to improve cancer detection over mammography alone, and early results suggest a larger cancer detection benefit from US than from 3D mammography, although research is ongoing.20 Adding US reduces the interval cancer rate in women with dense breasts to less than 10% of all cancers found—similar to results for women with fatty breasts.17,21,22

US can be performed by a trained technologist or a physician using a small transducer, which usually provides diagnostic images (so that most callbacks would be for a true finding), or a larger transducer and an automated system can be used to create more than a thousand images for radiologist review.23,24 Use of a hybrid system, a small transducer with an automated arm, has been validated as well.25 Screening US is not available universally, and with all these approaches optimal performance requires trained personnel. Supplemental screening US usually is covered by insurance but is nearly always subject to a deductible/copay.

Related article:

Educate patients about dense breasts and cancer risk

Reducing false-positives, callbacks, and additional testing