User login

Novel calculator predicts cancer risk in patients with CVD

Individualized 10-year and lifetime risks of cancer can now for the first time be estimated in patients with established cardiovascular disease, Cilie C. van ’t Klooster, MD, reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

She and her coinvestigators have developed an easy-to-use predictive model that generates individualized risk estimates for total cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer. The tool relies on nine readily available clinical variables: age, sex, smoking, weight, height, alcohol use, diabetes, antiplatelet drug use, and C-reactive protein level. The cancer risk calculator factors in an individual’s competing risk of death because of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The risk calculator was developed using data on 7,280 patients with established CVD enrolled in the ongoing long-term Dutch UCC-SMART (Utrecht Cardiovascular Cohort – Second Manifestations of Arterial Disease) study, then independently validated in 9,322 patients in the double-blind CANTOS (Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes) trial, explained Dr. van ’t Klooster of Utrecht (the Netherlands) University.

Several other prediction models estimate the risk of a specific type of cancer, most commonly breast cancer or lung cancer. But the new Utrecht prediction tool is the first one to estimate total cancer risk. It’s also the first to apply specifically to patients with known CVD, thus filling an unmet need, because patients with established CVD are known to be on average at 19% increased risk of total cancer and 56% greater risk for lung cancer, compared with the general population. This is thought to be caused mainly by shared risk factors, including smoking, obesity, and low-grade systemic inflammation.

As the Utrecht/CANTOS analysis shows, however, that 19% increased relative risk for cancer in patients with CVD doesn’t tell the whole story. While the median lifetime and 10-year risks of total cancer in CANTOS were 26% and 10%, respectively, the individual patient risks for total cancer estimated using the Dutch prediction model ranged from 1% to 52% for lifetime and from 1% to 31% for 10-year risk. The same was true for lung cancer risk: median 5% lifetime and 2% 10-year risks, with individual patient risks ranging from 0% to 37% and from 0% to 24%. Likewise for colorectal cancer: a median 4% lifetime risk, ranging from 0% to 6%, and a median 2% risk over the next 10 years, with personalized risks ranging as high as 13% for lifetime risk and 6% for 10-year colorectal cancer risk.

The risk calculator performed “reasonably well,” according to Dr. van ’t Klooster. She pointed to a C-statistic of 0.74 for lung cancer, 0.63 for total cancer, and 0.64 for colorectal cancer. It’s possible the risk predictor’s performance could be further enhanced by incorporation of several potentially important factors that weren’t available in the UCC-SMART derivation cohort, including race, education level, and socioeconomic status, she added.

Potential applications for the risk calculator in clinical practice require further study, but include using the lifetime risk prediction for cancer as a motivational aid in conversations with patients about the importance of behavioral change in support of a healthier lifestyle. Also, a high predicted 10-year lung cancer risk could potentially be used to lower the threshold for a screening chest CT, resulting in earlier detection and treatment of lung cancer, Dr. van ’t Klooster noted.

In an interview, Bonnie Ky, MD, MSCE, praised the risk prediction study as rigorously executed, topical, and clinically significant.

“This paper signifies the overlap between our two disciplines of cancer and cardiovascular disease in terms of the risks that we face together when we care for this patient population,” said Dr. Ky, a cardiologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Many of us in medicine believe in the importance of risk prediction: identifying who’s at high risk and doing everything we can to mitigate that risk. This paper speaks to that and moves us one step closer to accomplishing that aim,” added Dr. Ky, who is editor in chief of JACC: CardioOncology, which published the study simultaneously with Dr. van ’t Klooster’s presentation at ESC 2020. The paper provides direct access to the risk calculator.

Dr. van ’t Klooster reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study. UCC-SMART is funded by a Utrecht University grant, and CANTOS was funded by Novartis.

SOURCE: van ’t Klooster CC. ESC 2020 and JACC CardioOncol. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.07.001.

Individualized 10-year and lifetime risks of cancer can now for the first time be estimated in patients with established cardiovascular disease, Cilie C. van ’t Klooster, MD, reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

She and her coinvestigators have developed an easy-to-use predictive model that generates individualized risk estimates for total cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer. The tool relies on nine readily available clinical variables: age, sex, smoking, weight, height, alcohol use, diabetes, antiplatelet drug use, and C-reactive protein level. The cancer risk calculator factors in an individual’s competing risk of death because of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The risk calculator was developed using data on 7,280 patients with established CVD enrolled in the ongoing long-term Dutch UCC-SMART (Utrecht Cardiovascular Cohort – Second Manifestations of Arterial Disease) study, then independently validated in 9,322 patients in the double-blind CANTOS (Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes) trial, explained Dr. van ’t Klooster of Utrecht (the Netherlands) University.

Several other prediction models estimate the risk of a specific type of cancer, most commonly breast cancer or lung cancer. But the new Utrecht prediction tool is the first one to estimate total cancer risk. It’s also the first to apply specifically to patients with known CVD, thus filling an unmet need, because patients with established CVD are known to be on average at 19% increased risk of total cancer and 56% greater risk for lung cancer, compared with the general population. This is thought to be caused mainly by shared risk factors, including smoking, obesity, and low-grade systemic inflammation.

As the Utrecht/CANTOS analysis shows, however, that 19% increased relative risk for cancer in patients with CVD doesn’t tell the whole story. While the median lifetime and 10-year risks of total cancer in CANTOS were 26% and 10%, respectively, the individual patient risks for total cancer estimated using the Dutch prediction model ranged from 1% to 52% for lifetime and from 1% to 31% for 10-year risk. The same was true for lung cancer risk: median 5% lifetime and 2% 10-year risks, with individual patient risks ranging from 0% to 37% and from 0% to 24%. Likewise for colorectal cancer: a median 4% lifetime risk, ranging from 0% to 6%, and a median 2% risk over the next 10 years, with personalized risks ranging as high as 13% for lifetime risk and 6% for 10-year colorectal cancer risk.

The risk calculator performed “reasonably well,” according to Dr. van ’t Klooster. She pointed to a C-statistic of 0.74 for lung cancer, 0.63 for total cancer, and 0.64 for colorectal cancer. It’s possible the risk predictor’s performance could be further enhanced by incorporation of several potentially important factors that weren’t available in the UCC-SMART derivation cohort, including race, education level, and socioeconomic status, she added.

Potential applications for the risk calculator in clinical practice require further study, but include using the lifetime risk prediction for cancer as a motivational aid in conversations with patients about the importance of behavioral change in support of a healthier lifestyle. Also, a high predicted 10-year lung cancer risk could potentially be used to lower the threshold for a screening chest CT, resulting in earlier detection and treatment of lung cancer, Dr. van ’t Klooster noted.

In an interview, Bonnie Ky, MD, MSCE, praised the risk prediction study as rigorously executed, topical, and clinically significant.

“This paper signifies the overlap between our two disciplines of cancer and cardiovascular disease in terms of the risks that we face together when we care for this patient population,” said Dr. Ky, a cardiologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Many of us in medicine believe in the importance of risk prediction: identifying who’s at high risk and doing everything we can to mitigate that risk. This paper speaks to that and moves us one step closer to accomplishing that aim,” added Dr. Ky, who is editor in chief of JACC: CardioOncology, which published the study simultaneously with Dr. van ’t Klooster’s presentation at ESC 2020. The paper provides direct access to the risk calculator.

Dr. van ’t Klooster reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study. UCC-SMART is funded by a Utrecht University grant, and CANTOS was funded by Novartis.

SOURCE: van ’t Klooster CC. ESC 2020 and JACC CardioOncol. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.07.001.

Individualized 10-year and lifetime risks of cancer can now for the first time be estimated in patients with established cardiovascular disease, Cilie C. van ’t Klooster, MD, reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

She and her coinvestigators have developed an easy-to-use predictive model that generates individualized risk estimates for total cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer. The tool relies on nine readily available clinical variables: age, sex, smoking, weight, height, alcohol use, diabetes, antiplatelet drug use, and C-reactive protein level. The cancer risk calculator factors in an individual’s competing risk of death because of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The risk calculator was developed using data on 7,280 patients with established CVD enrolled in the ongoing long-term Dutch UCC-SMART (Utrecht Cardiovascular Cohort – Second Manifestations of Arterial Disease) study, then independently validated in 9,322 patients in the double-blind CANTOS (Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes) trial, explained Dr. van ’t Klooster of Utrecht (the Netherlands) University.

Several other prediction models estimate the risk of a specific type of cancer, most commonly breast cancer or lung cancer. But the new Utrecht prediction tool is the first one to estimate total cancer risk. It’s also the first to apply specifically to patients with known CVD, thus filling an unmet need, because patients with established CVD are known to be on average at 19% increased risk of total cancer and 56% greater risk for lung cancer, compared with the general population. This is thought to be caused mainly by shared risk factors, including smoking, obesity, and low-grade systemic inflammation.

As the Utrecht/CANTOS analysis shows, however, that 19% increased relative risk for cancer in patients with CVD doesn’t tell the whole story. While the median lifetime and 10-year risks of total cancer in CANTOS were 26% and 10%, respectively, the individual patient risks for total cancer estimated using the Dutch prediction model ranged from 1% to 52% for lifetime and from 1% to 31% for 10-year risk. The same was true for lung cancer risk: median 5% lifetime and 2% 10-year risks, with individual patient risks ranging from 0% to 37% and from 0% to 24%. Likewise for colorectal cancer: a median 4% lifetime risk, ranging from 0% to 6%, and a median 2% risk over the next 10 years, with personalized risks ranging as high as 13% for lifetime risk and 6% for 10-year colorectal cancer risk.

The risk calculator performed “reasonably well,” according to Dr. van ’t Klooster. She pointed to a C-statistic of 0.74 for lung cancer, 0.63 for total cancer, and 0.64 for colorectal cancer. It’s possible the risk predictor’s performance could be further enhanced by incorporation of several potentially important factors that weren’t available in the UCC-SMART derivation cohort, including race, education level, and socioeconomic status, she added.

Potential applications for the risk calculator in clinical practice require further study, but include using the lifetime risk prediction for cancer as a motivational aid in conversations with patients about the importance of behavioral change in support of a healthier lifestyle. Also, a high predicted 10-year lung cancer risk could potentially be used to lower the threshold for a screening chest CT, resulting in earlier detection and treatment of lung cancer, Dr. van ’t Klooster noted.

In an interview, Bonnie Ky, MD, MSCE, praised the risk prediction study as rigorously executed, topical, and clinically significant.

“This paper signifies the overlap between our two disciplines of cancer and cardiovascular disease in terms of the risks that we face together when we care for this patient population,” said Dr. Ky, a cardiologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Many of us in medicine believe in the importance of risk prediction: identifying who’s at high risk and doing everything we can to mitigate that risk. This paper speaks to that and moves us one step closer to accomplishing that aim,” added Dr. Ky, who is editor in chief of JACC: CardioOncology, which published the study simultaneously with Dr. van ’t Klooster’s presentation at ESC 2020. The paper provides direct access to the risk calculator.

Dr. van ’t Klooster reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study. UCC-SMART is funded by a Utrecht University grant, and CANTOS was funded by Novartis.

SOURCE: van ’t Klooster CC. ESC 2020 and JACC CardioOncol. 2020 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.07.001.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2020

The earlier the better for colchicine post-MI: COLCOT

The earlier the anti-inflammatory drug colchicine is initiated after a myocardial infarction (MI) the greater the benefit, a new COLCOT analysis suggests.

The parent trial was conducted in patients with a recent MI because of the intense inflammation present at that time, and added colchicine 0.5 mg daily to standard care within 30 days following MI.

As previously reported, colchicine significantly reduced the risk of the primary end point – a composite of cardiovascular (CV) death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina requiring revascularization – by 23% compared with placebo.

This new analysis shows the risk was reduced by 48% in patients receiving colchicine within 3 days of an MI (4.3% vs. 8.3%; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-0.84, P = .007).

Risk of a secondary efficacy end point – CV death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, or stroke – was reduced by 45% over an average follow up of 22.7 months (3.3% vs 6.1%; adjusted HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.32-0.95, P = .031).

“We believe that our results support an early, in-hospital initiation of adjunctive colchicine for post-MI prevention,” Nadia Bouabdallaoui, MD, Montreal Heart Institute, Quebec, Canada, said during an online session devoted to colchicine at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020.

Session moderator Massimo Imazio, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Turin, Italy, said the improved outcomes suggest that earlier treatment is better – a finding that parallels his own experience using colchicine in patients with pericarditis.

“This substudy is very important because this is probably also the year in cardiovascular applications [that] early use of the drug could improve outcomes,” he said.

Positive data have been accumulating for colchicine from COLCOT, LoDoCo, and, most recently, the LoDoCo2 trial, even as another anti-inflammatory drug, methotrexate, flamed out as secondary prevention in the CIRT trial.

The new COLCOT substudy included 4,661 of the 4,745 original patients and examined treatment initiation using three strata: within 0-3 days (n = 1,193), 4-7 days (n = 720), and 8-30 days (n = 2,748). Patients who received treatment within 3 days were slightly younger, more likely to be smokers, and to have a shorter time from MI to randomization (2.1 days vs 5.1 days vs. 20.8 days, respectively).

In the subset receiving treatment within 3 days, those assigned to colchicine had the same number of cardiac deaths as those given placebo (2 vs. 2) but fewer resuscitated cardiac arrests (1 vs. 3), MIs (17 vs. 29), strokes (1 vs. 5), and urgent hospitalizations for angina requiring revascularization (6 vs. 17).

“A larger trial might have allowed for a better assessment of individual endpoints and subgroups,” observed Bouabdallaoui.

Although there is growing support for colchicine, experts caution that the drug many not be for everyone. In COLCOT, 1 in 10 patients were unable to tolerate the drug, largely because of gastrointestinal (GI) issues.

Pharmacogenomics substudy

A second COLCOT substudy aimed to identify genetic markers predictive of colchicine response and to gain insights into the mechanisms behind this response. It included 767 patients treated with colchicine and another 755 treated with placebo – or about one-third the patients in the original trial.

A genome-wide association study did not find a significant association for the primary CV endpoint, although a prespecified subgroup analysis in men identified an interesting region on chromosome 9 (variant: rs10811106), which just missed reaching genomewide significance, said Marie-Pierre Dubé, PhD, director of the Université de Montréal Beaulieu-Saucier Pharmacogenomics Centre at the Montreal Heart Institute.

In addition, the genomewide analysis found two significant regions for GI events: one on chromosome 6 (variant: rs6916345) and one on chromosome 10 (variant: rs74795203).

For each of the identified regions, the researchers then tested the effect of the allele in the placebo group and the interaction between the genetic variant and treatment with colchicine. For the chromosome 9 region in males, there was no effect in the placebo group and a significant interaction in the colchicine group.

For the significant GI event findings, there was a small effect for the chromosome 6 region in the placebo group and a very significant interaction with colchicine, Dubé said. Similarly, there was no effect for the chromosome 10 region in the placebo group and a significant interaction with colchicine.

Additional analyses in stratified patient populations showed that males with the protective allele (CC) for the chromosome 9 region represented 83% of the population. The primary CV endpoint occurred in 3.2% of these men treated with colchicine and 6.3% treated with placebo (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.24 - 0.86).

For the gastrointestinal events, 25% of patients carried the risk allele (AA) for the chromosome 6 region and 36.9% of these had GI events when treated with colchicine versus 18.6% when treated with placebo (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.57-3.72).

Similarly, 13% of individuals carried one or two copies of the risk allele (AG+GG) for the chromosome 10 region and the risk of GI events in these was nearly four times higher with colchicine (47.1% vs. 18.9%; HR, 3.98; 95% CI 2.24-7.07).

Functional genomic analyses of the identified regions were also performed and showed that the chromosome 9 locus overlaps with the SAXO1 gene, a stabilizer of axonemal microtubules 1.

“The leading variant at this locus (rs10811106 C allele) correlated with the expression of the HAUS6 gene, which is involved in microtubule generation from existing microtubules, and may interact with the effect of colchicine, which is known to inhibit microtubule formation,” observed Dubé.

Also, the chromosome 6 locus associated with gastrointestinal events was colocalizing with the Crohn’s disease locus, adding further support for this region.

“The results support potential personalized approaches to inflammation reduction for cardiovascular prevention,” Dubé said.

This is a post hoc subgroup analysis, however, and replication is necessary, ideally in prospective randomized trials, she noted.

The substudy is important because it provides further insights into the link between colchicine and microtubule polymerization, affecting the activation of the inflammasome, session moderator Imazio said.

“Second, it is important because pharmacogenomics can help us to better understand the optimal responder to colchicine and colchicine resistance,” he said. “So it can be useful for personalized medicine, leading to the proper use of the drug for the proper patient.”

COLCOT was supported by the government of Quebec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and philanthropic foundations. Bouabdallaoui has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dubé reported grants from the government of Quebec; personal fees from DalCor and GlaxoSmithKline; research support from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Servier, Sanofi; and minor equity interest in DalCor. Dubé is also coauthor of patents on pharmacogenomics-guided CETP inhibition, and pharmacogenomics markers of response to colchicine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The earlier the anti-inflammatory drug colchicine is initiated after a myocardial infarction (MI) the greater the benefit, a new COLCOT analysis suggests.

The parent trial was conducted in patients with a recent MI because of the intense inflammation present at that time, and added colchicine 0.5 mg daily to standard care within 30 days following MI.

As previously reported, colchicine significantly reduced the risk of the primary end point – a composite of cardiovascular (CV) death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina requiring revascularization – by 23% compared with placebo.

This new analysis shows the risk was reduced by 48% in patients receiving colchicine within 3 days of an MI (4.3% vs. 8.3%; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-0.84, P = .007).

Risk of a secondary efficacy end point – CV death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, or stroke – was reduced by 45% over an average follow up of 22.7 months (3.3% vs 6.1%; adjusted HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.32-0.95, P = .031).

“We believe that our results support an early, in-hospital initiation of adjunctive colchicine for post-MI prevention,” Nadia Bouabdallaoui, MD, Montreal Heart Institute, Quebec, Canada, said during an online session devoted to colchicine at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020.

Session moderator Massimo Imazio, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Turin, Italy, said the improved outcomes suggest that earlier treatment is better – a finding that parallels his own experience using colchicine in patients with pericarditis.

“This substudy is very important because this is probably also the year in cardiovascular applications [that] early use of the drug could improve outcomes,” he said.

Positive data have been accumulating for colchicine from COLCOT, LoDoCo, and, most recently, the LoDoCo2 trial, even as another anti-inflammatory drug, methotrexate, flamed out as secondary prevention in the CIRT trial.

The new COLCOT substudy included 4,661 of the 4,745 original patients and examined treatment initiation using three strata: within 0-3 days (n = 1,193), 4-7 days (n = 720), and 8-30 days (n = 2,748). Patients who received treatment within 3 days were slightly younger, more likely to be smokers, and to have a shorter time from MI to randomization (2.1 days vs 5.1 days vs. 20.8 days, respectively).

In the subset receiving treatment within 3 days, those assigned to colchicine had the same number of cardiac deaths as those given placebo (2 vs. 2) but fewer resuscitated cardiac arrests (1 vs. 3), MIs (17 vs. 29), strokes (1 vs. 5), and urgent hospitalizations for angina requiring revascularization (6 vs. 17).

“A larger trial might have allowed for a better assessment of individual endpoints and subgroups,” observed Bouabdallaoui.

Although there is growing support for colchicine, experts caution that the drug many not be for everyone. In COLCOT, 1 in 10 patients were unable to tolerate the drug, largely because of gastrointestinal (GI) issues.

Pharmacogenomics substudy

A second COLCOT substudy aimed to identify genetic markers predictive of colchicine response and to gain insights into the mechanisms behind this response. It included 767 patients treated with colchicine and another 755 treated with placebo – or about one-third the patients in the original trial.

A genome-wide association study did not find a significant association for the primary CV endpoint, although a prespecified subgroup analysis in men identified an interesting region on chromosome 9 (variant: rs10811106), which just missed reaching genomewide significance, said Marie-Pierre Dubé, PhD, director of the Université de Montréal Beaulieu-Saucier Pharmacogenomics Centre at the Montreal Heart Institute.

In addition, the genomewide analysis found two significant regions for GI events: one on chromosome 6 (variant: rs6916345) and one on chromosome 10 (variant: rs74795203).

For each of the identified regions, the researchers then tested the effect of the allele in the placebo group and the interaction between the genetic variant and treatment with colchicine. For the chromosome 9 region in males, there was no effect in the placebo group and a significant interaction in the colchicine group.

For the significant GI event findings, there was a small effect for the chromosome 6 region in the placebo group and a very significant interaction with colchicine, Dubé said. Similarly, there was no effect for the chromosome 10 region in the placebo group and a significant interaction with colchicine.

Additional analyses in stratified patient populations showed that males with the protective allele (CC) for the chromosome 9 region represented 83% of the population. The primary CV endpoint occurred in 3.2% of these men treated with colchicine and 6.3% treated with placebo (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.24 - 0.86).

For the gastrointestinal events, 25% of patients carried the risk allele (AA) for the chromosome 6 region and 36.9% of these had GI events when treated with colchicine versus 18.6% when treated with placebo (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.57-3.72).

Similarly, 13% of individuals carried one or two copies of the risk allele (AG+GG) for the chromosome 10 region and the risk of GI events in these was nearly four times higher with colchicine (47.1% vs. 18.9%; HR, 3.98; 95% CI 2.24-7.07).

Functional genomic analyses of the identified regions were also performed and showed that the chromosome 9 locus overlaps with the SAXO1 gene, a stabilizer of axonemal microtubules 1.

“The leading variant at this locus (rs10811106 C allele) correlated with the expression of the HAUS6 gene, which is involved in microtubule generation from existing microtubules, and may interact with the effect of colchicine, which is known to inhibit microtubule formation,” observed Dubé.

Also, the chromosome 6 locus associated with gastrointestinal events was colocalizing with the Crohn’s disease locus, adding further support for this region.

“The results support potential personalized approaches to inflammation reduction for cardiovascular prevention,” Dubé said.

This is a post hoc subgroup analysis, however, and replication is necessary, ideally in prospective randomized trials, she noted.

The substudy is important because it provides further insights into the link between colchicine and microtubule polymerization, affecting the activation of the inflammasome, session moderator Imazio said.

“Second, it is important because pharmacogenomics can help us to better understand the optimal responder to colchicine and colchicine resistance,” he said. “So it can be useful for personalized medicine, leading to the proper use of the drug for the proper patient.”

COLCOT was supported by the government of Quebec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and philanthropic foundations. Bouabdallaoui has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dubé reported grants from the government of Quebec; personal fees from DalCor and GlaxoSmithKline; research support from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Servier, Sanofi; and minor equity interest in DalCor. Dubé is also coauthor of patents on pharmacogenomics-guided CETP inhibition, and pharmacogenomics markers of response to colchicine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The earlier the anti-inflammatory drug colchicine is initiated after a myocardial infarction (MI) the greater the benefit, a new COLCOT analysis suggests.

The parent trial was conducted in patients with a recent MI because of the intense inflammation present at that time, and added colchicine 0.5 mg daily to standard care within 30 days following MI.

As previously reported, colchicine significantly reduced the risk of the primary end point – a composite of cardiovascular (CV) death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina requiring revascularization – by 23% compared with placebo.

This new analysis shows the risk was reduced by 48% in patients receiving colchicine within 3 days of an MI (4.3% vs. 8.3%; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.32-0.84, P = .007).

Risk of a secondary efficacy end point – CV death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, MI, or stroke – was reduced by 45% over an average follow up of 22.7 months (3.3% vs 6.1%; adjusted HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.32-0.95, P = .031).

“We believe that our results support an early, in-hospital initiation of adjunctive colchicine for post-MI prevention,” Nadia Bouabdallaoui, MD, Montreal Heart Institute, Quebec, Canada, said during an online session devoted to colchicine at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020.

Session moderator Massimo Imazio, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Turin, Italy, said the improved outcomes suggest that earlier treatment is better – a finding that parallels his own experience using colchicine in patients with pericarditis.

“This substudy is very important because this is probably also the year in cardiovascular applications [that] early use of the drug could improve outcomes,” he said.

Positive data have been accumulating for colchicine from COLCOT, LoDoCo, and, most recently, the LoDoCo2 trial, even as another anti-inflammatory drug, methotrexate, flamed out as secondary prevention in the CIRT trial.

The new COLCOT substudy included 4,661 of the 4,745 original patients and examined treatment initiation using three strata: within 0-3 days (n = 1,193), 4-7 days (n = 720), and 8-30 days (n = 2,748). Patients who received treatment within 3 days were slightly younger, more likely to be smokers, and to have a shorter time from MI to randomization (2.1 days vs 5.1 days vs. 20.8 days, respectively).

In the subset receiving treatment within 3 days, those assigned to colchicine had the same number of cardiac deaths as those given placebo (2 vs. 2) but fewer resuscitated cardiac arrests (1 vs. 3), MIs (17 vs. 29), strokes (1 vs. 5), and urgent hospitalizations for angina requiring revascularization (6 vs. 17).

“A larger trial might have allowed for a better assessment of individual endpoints and subgroups,” observed Bouabdallaoui.

Although there is growing support for colchicine, experts caution that the drug many not be for everyone. In COLCOT, 1 in 10 patients were unable to tolerate the drug, largely because of gastrointestinal (GI) issues.

Pharmacogenomics substudy

A second COLCOT substudy aimed to identify genetic markers predictive of colchicine response and to gain insights into the mechanisms behind this response. It included 767 patients treated with colchicine and another 755 treated with placebo – or about one-third the patients in the original trial.

A genome-wide association study did not find a significant association for the primary CV endpoint, although a prespecified subgroup analysis in men identified an interesting region on chromosome 9 (variant: rs10811106), which just missed reaching genomewide significance, said Marie-Pierre Dubé, PhD, director of the Université de Montréal Beaulieu-Saucier Pharmacogenomics Centre at the Montreal Heart Institute.

In addition, the genomewide analysis found two significant regions for GI events: one on chromosome 6 (variant: rs6916345) and one on chromosome 10 (variant: rs74795203).

For each of the identified regions, the researchers then tested the effect of the allele in the placebo group and the interaction between the genetic variant and treatment with colchicine. For the chromosome 9 region in males, there was no effect in the placebo group and a significant interaction in the colchicine group.

For the significant GI event findings, there was a small effect for the chromosome 6 region in the placebo group and a very significant interaction with colchicine, Dubé said. Similarly, there was no effect for the chromosome 10 region in the placebo group and a significant interaction with colchicine.

Additional analyses in stratified patient populations showed that males with the protective allele (CC) for the chromosome 9 region represented 83% of the population. The primary CV endpoint occurred in 3.2% of these men treated with colchicine and 6.3% treated with placebo (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.24 - 0.86).

For the gastrointestinal events, 25% of patients carried the risk allele (AA) for the chromosome 6 region and 36.9% of these had GI events when treated with colchicine versus 18.6% when treated with placebo (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.57-3.72).

Similarly, 13% of individuals carried one or two copies of the risk allele (AG+GG) for the chromosome 10 region and the risk of GI events in these was nearly four times higher with colchicine (47.1% vs. 18.9%; HR, 3.98; 95% CI 2.24-7.07).

Functional genomic analyses of the identified regions were also performed and showed that the chromosome 9 locus overlaps with the SAXO1 gene, a stabilizer of axonemal microtubules 1.

“The leading variant at this locus (rs10811106 C allele) correlated with the expression of the HAUS6 gene, which is involved in microtubule generation from existing microtubules, and may interact with the effect of colchicine, which is known to inhibit microtubule formation,” observed Dubé.

Also, the chromosome 6 locus associated with gastrointestinal events was colocalizing with the Crohn’s disease locus, adding further support for this region.

“The results support potential personalized approaches to inflammation reduction for cardiovascular prevention,” Dubé said.

This is a post hoc subgroup analysis, however, and replication is necessary, ideally in prospective randomized trials, she noted.

The substudy is important because it provides further insights into the link between colchicine and microtubule polymerization, affecting the activation of the inflammasome, session moderator Imazio said.

“Second, it is important because pharmacogenomics can help us to better understand the optimal responder to colchicine and colchicine resistance,” he said. “So it can be useful for personalized medicine, leading to the proper use of the drug for the proper patient.”

COLCOT was supported by the government of Quebec, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and philanthropic foundations. Bouabdallaoui has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dubé reported grants from the government of Quebec; personal fees from DalCor and GlaxoSmithKline; research support from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Servier, Sanofi; and minor equity interest in DalCor. Dubé is also coauthor of patents on pharmacogenomics-guided CETP inhibition, and pharmacogenomics markers of response to colchicine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

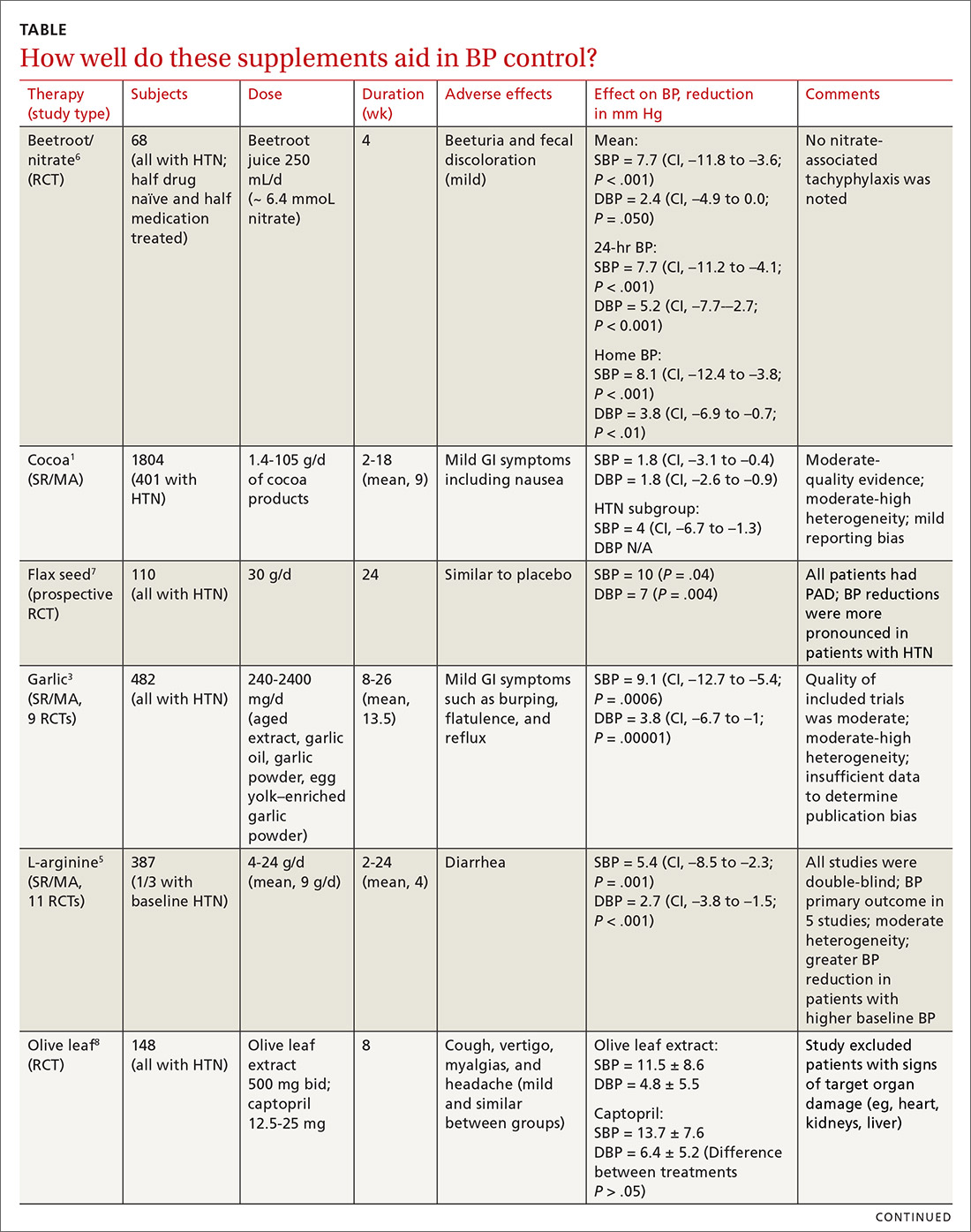

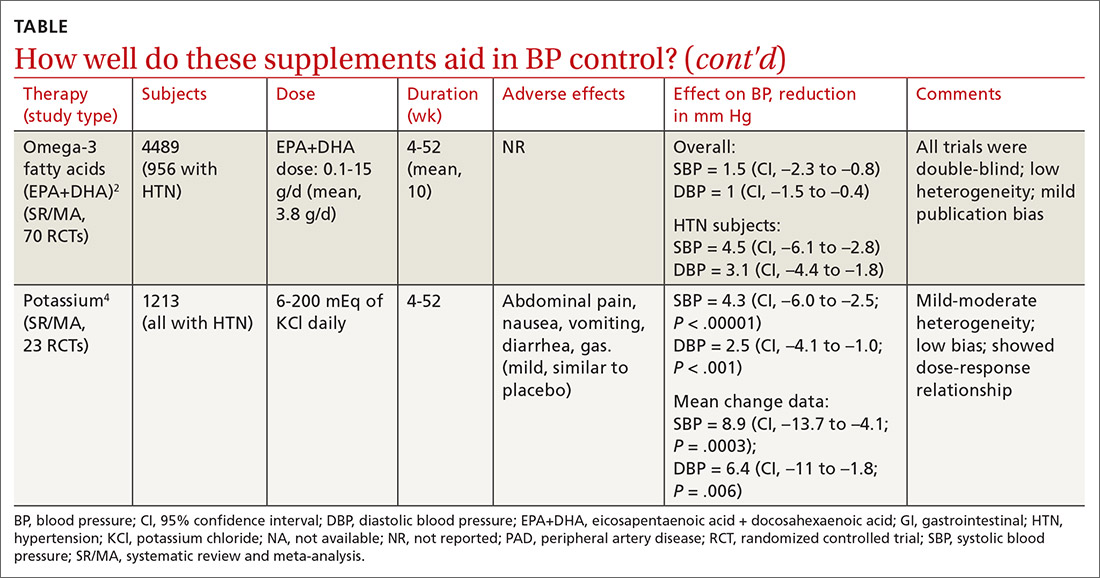

Does evidence support the use of supplements to aid in BP control?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Cocoa. A 2017 Cochrane review evaluated data from more than 1800 patients (401 in hypertension studies) to determine the effect of cocoa on BP.1 Compared with placebo (in flavanol-free or low-flavanol controls), cocoa lowered systolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (confidence interval [CI], –3.1 to –0.4) and diastolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (CI, –2.6 to –0.9). Further analysis of patients with hypertension (only) showed a reduction in systolic BP of 4 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1.3).

Omega-3 fatty acids. Similarly, a 2014 meta-analysis investigating omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] + docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) included data from 4489 patients (956 with hypertension) and showed reductions in systolic BP of 1.5 mm Hg (CI, –2.3 to –0.8) and diastolic BP of 1 mm Hg (CI, –1.5 to –0.4), compared with placebo.2 Again, subgroup analysis of patients with hypertension (only) at baseline revealed a greater decrease in systolic and diastolic BP: 4.5 mm Hg (CI, –6.1 to –2.8) and 3.1 mm Hg (CI, –4.4 to –1.8), respectively.

Garlic and potassium chloride. Separate meta-analyses that included only patients with hypertension found that both garlic and potassium significantly lowered BP.3,4 A 2015 meta-analysis comparing a variety of garlic preparations with placebo in patients with hypertension showed decreases in systolic BP of 9.1 mm Hg (CI, –12.7 to –5.4) and in diastolic BP of 3.8 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1).3 Meanwhile, a meta-analysis in 2017 comparing different doses of potassium chloride with placebo demonstrated reductions in systolic BP of 4.3 mm Hg (CI, –6 to –2.5) and diastolic BP of 2.5 mm Hg (CI, –4.1 to –1).4

L-arginine. Another meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported evidence that oral L-arginine, compared with placebo, significantly reduced systolic BP by 5.4 mm Hg (CI, –8.5 to –2.3) and diastolic BP by 2.7 mm Hg (CI, –3.8 to –1.5).5 Close to one-third of patients had hypertension at baseline.

Beetroot juice. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed that consumption of beetroot juice (with nitrate) once daily reduced BP in 3 different settings (clinic, 24-hour ambulatory, and home readings) when compared with placebo (nitrate-free beetroot juice).6 Study participants were mostly British women, overweight, without significant cardiovascular or renal disease, and with uncontrolled ambulatory BP (> 135/85 mm Hg).

Flax seed. A prospective, double-blind trial of patients with peripheral artery disease compared the antihypertensive effects of flax seed with placebo in patients with and without hypertension and found marked decreases in systolic and diastolic BP.7 Study participants were all older than 40 years without other major cardiac or renal disease, and the majority of enrolled patients with hypertension were concurrently taking medications to treat hypertension during the study.

Olive leaf extract. A double-blind, parallel, and active-control clinical trial in Indonesia compared the BP-lowering effect of olive leaf extract (Olea europaea) to captopril as monotherapies in patients with stage 1 hypertension.8 After a 4-week period of dietary intervention, individuals who were still hypertensive (range, 140/90 to 159/99 mm Hg) were treated with either olive leaf extract or captopril. After 8 weeks of treatment, both groups saw comparable reductions in BP.

Continue to: Editor's takeaway

Editor’s takeaway

Many studies have demonstrated BP benefits from a variety of natural supplements. Although the studies’ durations are short, the effects sometimes modest, and the outcomes disease-oriented rather than patient-oriented, the findings can provide a useful complement to our efforts to manage this most common chronic disease.

1. Ried K, Fakler P, Stocks NP. Effect of cocoa on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(4):CD008893.

2. Miller PE, Van Elswyk M, Alexander DD. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:885-896.

3. Rohner A, Ried K, Sobenin IA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of garlic preparations on blood pressure in individuals with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:414-423.

4. Poorolajal J, Zeraati F, Soltanian AR, et al. Oral potassium supplementation for management of essential hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174967.

5. Dong JY, Qin LQ, Zhang Z, et al. Effect of oral L-arginine supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:959-965.

6. Kapil V, Khambata RS, Robertson A, et al. Dietary nitrate provides sustained blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients: a randomized, phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hypertension. 2015;65:320-327.

7. Rodriguez-Leyva D, Weighell W, Edel AL, et al. Potent antihypertensive action of dietary flaxseed in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2013;62:1081-1089.

8. Susalit E, Agus N, Effendi I, et al. Olive (Olea europaea) leaf extract effective in patients with stage-1 hypertension: comparison with captopril. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:251-258.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Cocoa. A 2017 Cochrane review evaluated data from more than 1800 patients (401 in hypertension studies) to determine the effect of cocoa on BP.1 Compared with placebo (in flavanol-free or low-flavanol controls), cocoa lowered systolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (confidence interval [CI], –3.1 to –0.4) and diastolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (CI, –2.6 to –0.9). Further analysis of patients with hypertension (only) showed a reduction in systolic BP of 4 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1.3).

Omega-3 fatty acids. Similarly, a 2014 meta-analysis investigating omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] + docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) included data from 4489 patients (956 with hypertension) and showed reductions in systolic BP of 1.5 mm Hg (CI, –2.3 to –0.8) and diastolic BP of 1 mm Hg (CI, –1.5 to –0.4), compared with placebo.2 Again, subgroup analysis of patients with hypertension (only) at baseline revealed a greater decrease in systolic and diastolic BP: 4.5 mm Hg (CI, –6.1 to –2.8) and 3.1 mm Hg (CI, –4.4 to –1.8), respectively.

Garlic and potassium chloride. Separate meta-analyses that included only patients with hypertension found that both garlic and potassium significantly lowered BP.3,4 A 2015 meta-analysis comparing a variety of garlic preparations with placebo in patients with hypertension showed decreases in systolic BP of 9.1 mm Hg (CI, –12.7 to –5.4) and in diastolic BP of 3.8 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1).3 Meanwhile, a meta-analysis in 2017 comparing different doses of potassium chloride with placebo demonstrated reductions in systolic BP of 4.3 mm Hg (CI, –6 to –2.5) and diastolic BP of 2.5 mm Hg (CI, –4.1 to –1).4

L-arginine. Another meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported evidence that oral L-arginine, compared with placebo, significantly reduced systolic BP by 5.4 mm Hg (CI, –8.5 to –2.3) and diastolic BP by 2.7 mm Hg (CI, –3.8 to –1.5).5 Close to one-third of patients had hypertension at baseline.

Beetroot juice. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed that consumption of beetroot juice (with nitrate) once daily reduced BP in 3 different settings (clinic, 24-hour ambulatory, and home readings) when compared with placebo (nitrate-free beetroot juice).6 Study participants were mostly British women, overweight, without significant cardiovascular or renal disease, and with uncontrolled ambulatory BP (> 135/85 mm Hg).

Flax seed. A prospective, double-blind trial of patients with peripheral artery disease compared the antihypertensive effects of flax seed with placebo in patients with and without hypertension and found marked decreases in systolic and diastolic BP.7 Study participants were all older than 40 years without other major cardiac or renal disease, and the majority of enrolled patients with hypertension were concurrently taking medications to treat hypertension during the study.

Olive leaf extract. A double-blind, parallel, and active-control clinical trial in Indonesia compared the BP-lowering effect of olive leaf extract (Olea europaea) to captopril as monotherapies in patients with stage 1 hypertension.8 After a 4-week period of dietary intervention, individuals who were still hypertensive (range, 140/90 to 159/99 mm Hg) were treated with either olive leaf extract or captopril. After 8 weeks of treatment, both groups saw comparable reductions in BP.

Continue to: Editor's takeaway

Editor’s takeaway

Many studies have demonstrated BP benefits from a variety of natural supplements. Although the studies’ durations are short, the effects sometimes modest, and the outcomes disease-oriented rather than patient-oriented, the findings can provide a useful complement to our efforts to manage this most common chronic disease.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Cocoa. A 2017 Cochrane review evaluated data from more than 1800 patients (401 in hypertension studies) to determine the effect of cocoa on BP.1 Compared with placebo (in flavanol-free or low-flavanol controls), cocoa lowered systolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (confidence interval [CI], –3.1 to –0.4) and diastolic BP by 1.8 mm Hg (CI, –2.6 to –0.9). Further analysis of patients with hypertension (only) showed a reduction in systolic BP of 4 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1.3).

Omega-3 fatty acids. Similarly, a 2014 meta-analysis investigating omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] + docosahexaenoic acid [DHA]) included data from 4489 patients (956 with hypertension) and showed reductions in systolic BP of 1.5 mm Hg (CI, –2.3 to –0.8) and diastolic BP of 1 mm Hg (CI, –1.5 to –0.4), compared with placebo.2 Again, subgroup analysis of patients with hypertension (only) at baseline revealed a greater decrease in systolic and diastolic BP: 4.5 mm Hg (CI, –6.1 to –2.8) and 3.1 mm Hg (CI, –4.4 to –1.8), respectively.

Garlic and potassium chloride. Separate meta-analyses that included only patients with hypertension found that both garlic and potassium significantly lowered BP.3,4 A 2015 meta-analysis comparing a variety of garlic preparations with placebo in patients with hypertension showed decreases in systolic BP of 9.1 mm Hg (CI, –12.7 to –5.4) and in diastolic BP of 3.8 mm Hg (CI, –6.7 to –1).3 Meanwhile, a meta-analysis in 2017 comparing different doses of potassium chloride with placebo demonstrated reductions in systolic BP of 4.3 mm Hg (CI, –6 to –2.5) and diastolic BP of 2.5 mm Hg (CI, –4.1 to –1).4

L-arginine. Another meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported evidence that oral L-arginine, compared with placebo, significantly reduced systolic BP by 5.4 mm Hg (CI, –8.5 to –2.3) and diastolic BP by 2.7 mm Hg (CI, –3.8 to –1.5).5 Close to one-third of patients had hypertension at baseline.

Beetroot juice. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study showed that consumption of beetroot juice (with nitrate) once daily reduced BP in 3 different settings (clinic, 24-hour ambulatory, and home readings) when compared with placebo (nitrate-free beetroot juice).6 Study participants were mostly British women, overweight, without significant cardiovascular or renal disease, and with uncontrolled ambulatory BP (> 135/85 mm Hg).

Flax seed. A prospective, double-blind trial of patients with peripheral artery disease compared the antihypertensive effects of flax seed with placebo in patients with and without hypertension and found marked decreases in systolic and diastolic BP.7 Study participants were all older than 40 years without other major cardiac or renal disease, and the majority of enrolled patients with hypertension were concurrently taking medications to treat hypertension during the study.

Olive leaf extract. A double-blind, parallel, and active-control clinical trial in Indonesia compared the BP-lowering effect of olive leaf extract (Olea europaea) to captopril as monotherapies in patients with stage 1 hypertension.8 After a 4-week period of dietary intervention, individuals who were still hypertensive (range, 140/90 to 159/99 mm Hg) were treated with either olive leaf extract or captopril. After 8 weeks of treatment, both groups saw comparable reductions in BP.

Continue to: Editor's takeaway

Editor’s takeaway

Many studies have demonstrated BP benefits from a variety of natural supplements. Although the studies’ durations are short, the effects sometimes modest, and the outcomes disease-oriented rather than patient-oriented, the findings can provide a useful complement to our efforts to manage this most common chronic disease.

1. Ried K, Fakler P, Stocks NP. Effect of cocoa on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(4):CD008893.

2. Miller PE, Van Elswyk M, Alexander DD. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:885-896.

3. Rohner A, Ried K, Sobenin IA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of garlic preparations on blood pressure in individuals with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:414-423.

4. Poorolajal J, Zeraati F, Soltanian AR, et al. Oral potassium supplementation for management of essential hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174967.

5. Dong JY, Qin LQ, Zhang Z, et al. Effect of oral L-arginine supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:959-965.

6. Kapil V, Khambata RS, Robertson A, et al. Dietary nitrate provides sustained blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients: a randomized, phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hypertension. 2015;65:320-327.

7. Rodriguez-Leyva D, Weighell W, Edel AL, et al. Potent antihypertensive action of dietary flaxseed in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2013;62:1081-1089.

8. Susalit E, Agus N, Effendi I, et al. Olive (Olea europaea) leaf extract effective in patients with stage-1 hypertension: comparison with captopril. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:251-258.

1. Ried K, Fakler P, Stocks NP. Effect of cocoa on blood pressure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(4):CD008893.

2. Miller PE, Van Elswyk M, Alexander DD. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:885-896.

3. Rohner A, Ried K, Sobenin IA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of garlic preparations on blood pressure in individuals with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:414-423.

4. Poorolajal J, Zeraati F, Soltanian AR, et al. Oral potassium supplementation for management of essential hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174967.

5. Dong JY, Qin LQ, Zhang Z, et al. Effect of oral L-arginine supplementation on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2011;162:959-965.

6. Kapil V, Khambata RS, Robertson A, et al. Dietary nitrate provides sustained blood pressure lowering in hypertensive patients: a randomized, phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hypertension. 2015;65:320-327.

7. Rodriguez-Leyva D, Weighell W, Edel AL, et al. Potent antihypertensive action of dietary flaxseed in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2013;62:1081-1089.

8. Susalit E, Agus N, Effendi I, et al. Olive (Olea europaea) leaf extract effective in patients with stage-1 hypertension: comparison with captopril. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:251-258.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. A number of well-tolerated natural therapies have been shown to reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP). (See Table1-8 for summary.) However, the studies don’t provide direct evidence of whether the decrease in BP is linked to patient-oriented outcomes. Nor do they allow definitive conclusions concerning the lasting nature of the reductions, because most studies were fewer than 6 months in duration (strength of recommendation: C, disease-oriented evidence).

It's time to change when BP meds are taken

In this issue of JFP, there is an extraordinarily valuable PURL (Priority Updates from the Research Literature) for you. PURLs® are written by academic family physicians who comb through volumes of research to identify and then summarize for JFP important studies we believe should change your practice. After reading a PURL, you may find that you have already implemented this new evidence into your practice. In that case, the PURL confirms that you are doing the right thing.

Here is the good news from this month’s PURL: Having patients take their blood pressure (BP) medication in the evening, rather than in the morning, leads not only to better BP control but also to a reduction in cardiovascular events.1 How large is this effect? This simple intervention nearly cut in half the number of major cardiovascular events—including myocardial infarction, stroke, and congestive heart failure—and the risk for death from a cardiovascular event was reduced 56%. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 major cardiovascular event over the course of 6.3 years was 20. That means this intervention is more powerful than taking a statin!

The investigators, who call this intervention “chronotherapy” since it takes into account the body’s circadian rhythms, have been studying the effect of this simple intervention for many years, and this large randomized trial provides very strong evidence that it’s effective. Despite the excellent trial design and execution, some cardiovascular researchers have questioned the integrity of the trial and believe patients should continue to take their antihypertensives in the morning.2 The main investigator of the study, however, has provided a very strong rebuttal in print.3

I am delighted to see the positive results of this definitive trial of chronotherapy for hypertension. When these investigators published their first randomized trial of chronotherapy in 2010,4 which demonstrated a significant BP reduction with evening dosing of antihypertensives, I began telling all of my patients to take at least 1 of their antihypertensive meds in the evening. Maybe I was jumping the gun at that time, but we should all tell our patients to take their BP medication in the evening from now on. What could be an easier way to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality?

1. Hermida RC, Crespo JJ, Domínguez-Sardiña M, et al. Bedtime hypertension treatment improves cardiovascular risk reduction: the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial [published online ahead of print October 22, 2019]. Eur Heart J. 2019;ehz754. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz754

2. Kreutz R, Kjeldsen SE, Burnier M, et al. Blood pressure medication should not be routinely dosed at bedtime. We must disregard the data from the HYGIA project [editorial]. Blood Press. 2020;29:135-136.

3. Crespo JJ, Domínguez-Sardiña M, Otero A, et. al. Bedtime hypertension chronotherapy best reduces cardiovascular disease risk as corroborated by the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial. Rebuttal to European Society of Hypertension officials. Chronobiol Int. 2020;37:771-780.

4. Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojón A, Fernández JR. Influence of circadian time of hypertension treatment on cardiovascular risk: results of the MAPEC study. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:1629-1651.

In this issue of JFP, there is an extraordinarily valuable PURL (Priority Updates from the Research Literature) for you. PURLs® are written by academic family physicians who comb through volumes of research to identify and then summarize for JFP important studies we believe should change your practice. After reading a PURL, you may find that you have already implemented this new evidence into your practice. In that case, the PURL confirms that you are doing the right thing.

Here is the good news from this month’s PURL: Having patients take their blood pressure (BP) medication in the evening, rather than in the morning, leads not only to better BP control but also to a reduction in cardiovascular events.1 How large is this effect? This simple intervention nearly cut in half the number of major cardiovascular events—including myocardial infarction, stroke, and congestive heart failure—and the risk for death from a cardiovascular event was reduced 56%. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 major cardiovascular event over the course of 6.3 years was 20. That means this intervention is more powerful than taking a statin!

The investigators, who call this intervention “chronotherapy” since it takes into account the body’s circadian rhythms, have been studying the effect of this simple intervention for many years, and this large randomized trial provides very strong evidence that it’s effective. Despite the excellent trial design and execution, some cardiovascular researchers have questioned the integrity of the trial and believe patients should continue to take their antihypertensives in the morning.2 The main investigator of the study, however, has provided a very strong rebuttal in print.3

I am delighted to see the positive results of this definitive trial of chronotherapy for hypertension. When these investigators published their first randomized trial of chronotherapy in 2010,4 which demonstrated a significant BP reduction with evening dosing of antihypertensives, I began telling all of my patients to take at least 1 of their antihypertensive meds in the evening. Maybe I was jumping the gun at that time, but we should all tell our patients to take their BP medication in the evening from now on. What could be an easier way to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality?

In this issue of JFP, there is an extraordinarily valuable PURL (Priority Updates from the Research Literature) for you. PURLs® are written by academic family physicians who comb through volumes of research to identify and then summarize for JFP important studies we believe should change your practice. After reading a PURL, you may find that you have already implemented this new evidence into your practice. In that case, the PURL confirms that you are doing the right thing.

Here is the good news from this month’s PURL: Having patients take their blood pressure (BP) medication in the evening, rather than in the morning, leads not only to better BP control but also to a reduction in cardiovascular events.1 How large is this effect? This simple intervention nearly cut in half the number of major cardiovascular events—including myocardial infarction, stroke, and congestive heart failure—and the risk for death from a cardiovascular event was reduced 56%. The number needed to treat to prevent 1 major cardiovascular event over the course of 6.3 years was 20. That means this intervention is more powerful than taking a statin!

The investigators, who call this intervention “chronotherapy” since it takes into account the body’s circadian rhythms, have been studying the effect of this simple intervention for many years, and this large randomized trial provides very strong evidence that it’s effective. Despite the excellent trial design and execution, some cardiovascular researchers have questioned the integrity of the trial and believe patients should continue to take their antihypertensives in the morning.2 The main investigator of the study, however, has provided a very strong rebuttal in print.3

I am delighted to see the positive results of this definitive trial of chronotherapy for hypertension. When these investigators published their first randomized trial of chronotherapy in 2010,4 which demonstrated a significant BP reduction with evening dosing of antihypertensives, I began telling all of my patients to take at least 1 of their antihypertensive meds in the evening. Maybe I was jumping the gun at that time, but we should all tell our patients to take their BP medication in the evening from now on. What could be an easier way to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality?

1. Hermida RC, Crespo JJ, Domínguez-Sardiña M, et al. Bedtime hypertension treatment improves cardiovascular risk reduction: the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial [published online ahead of print October 22, 2019]. Eur Heart J. 2019;ehz754. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz754

2. Kreutz R, Kjeldsen SE, Burnier M, et al. Blood pressure medication should not be routinely dosed at bedtime. We must disregard the data from the HYGIA project [editorial]. Blood Press. 2020;29:135-136.

3. Crespo JJ, Domínguez-Sardiña M, Otero A, et. al. Bedtime hypertension chronotherapy best reduces cardiovascular disease risk as corroborated by the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial. Rebuttal to European Society of Hypertension officials. Chronobiol Int. 2020;37:771-780.

4. Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojón A, Fernández JR. Influence of circadian time of hypertension treatment on cardiovascular risk: results of the MAPEC study. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:1629-1651.

1. Hermida RC, Crespo JJ, Domínguez-Sardiña M, et al. Bedtime hypertension treatment improves cardiovascular risk reduction: the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial [published online ahead of print October 22, 2019]. Eur Heart J. 2019;ehz754. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz754

2. Kreutz R, Kjeldsen SE, Burnier M, et al. Blood pressure medication should not be routinely dosed at bedtime. We must disregard the data from the HYGIA project [editorial]. Blood Press. 2020;29:135-136.

3. Crespo JJ, Domínguez-Sardiña M, Otero A, et. al. Bedtime hypertension chronotherapy best reduces cardiovascular disease risk as corroborated by the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial. Rebuttal to European Society of Hypertension officials. Chronobiol Int. 2020;37:771-780.

4. Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojón A, Fernández JR. Influence of circadian time of hypertension treatment on cardiovascular risk: results of the MAPEC study. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:1629-1651.

Is it better to take that antihypertensive at night?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 54-year-old White woman presents to your office with new-onset hypertension. As you are discussing options for treatment, she mentions she would prefer once-daily dosing to help her remember to take her medication. She also wants to know what the best time of day is to take her medication to reduce her risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). What do you advise?

The burden of hypertension is significant and growing in the United States. The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines reported that more than 108 million people were affected in 2015-2016—up from 87 million in 1999-2000.2 Yet control of hypertension is improving among those receiving antihypertension pharmacotherapy. As reported in the ACC/AHA guidelines, data from the 2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicate an increase of controlled hypertension among those receiving treatment from 25.6% (1999-2000) to 43.5% (2015-2016).2

Chronotherapy involves the administration of medication in coordination with the body’s circadian rhythms to maximize therapeutic effectiveness and/or minimize adverse effects. It is not a new concept as it applies to hypertension. Circadian rhythm–dependent mechanisms influence the natural rise and fall of blood pressure (BP).1 The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, known to be most active at night, is a target mechanism for BP control.1 Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are more effective (alone or in combination with other agents) at reducing BP during sleep and wakefulness when they are taken at night.3,4 Additional prospective clinical trials and systematic reviews have documented improved BP during sleep and on 24-hour ambulatory monitoring when antihypertensives are taken at bedtime.3-5

However, there have been few long-term studies assessing the effects of bedtime administration of antihypertensive medication on CVD risk reduction with patient-oriented outcomes.6,7 Additionally, no studies have evaluated morning vs bedtime administration of antihypertensive medication for CVD risk reduction in a primary care setting. The 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of CVD offers no recommendation regarding when to take antihypertensive medication.8 Timing of medication administration also is not addressed in the NHANES study of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in US adults.9

This study sought to determine in a primary care setting whether taking antihypertensives at bedtime, as opposed to upon waking, more effectively reduces CVD risk.

STUDY SUMMARY

PM vs AM antihypertensive dosing reduces CV events

This prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint trial of antihypertensive medication administration timing was part of a large, multicenter Spanish study investigating ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) as a routine diagnostic tool.

Study participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to 2 treatment arms; participants either took all of their BP medications in the morning upon waking (n = 9532) or right before bedtime (n = 9552). The study was conducted in a primary care clinical setting. It included adult participants (age ≥ 18 years) with hypertension (defined as having at least 1 of the following benchmarks: awake systolic BP [SBP] mean ≥ 135 mm Hg, awake diastolic BP (DBP) mean ≥ 85 mm Hg, asleep SBP mean ≥ 120 mm Hg, asleep DBP mean ≥ 70 mm Hg as corroborated by 48-hour ABPM) who were taking at least 1 antihypertensive medication.

Continue to: Any antihypertension medication...

Any antihypertension medication included in the Spanish national formulary was allowed (exact agents were not delineated, but the following classes were included: ARB, ACE inhibitor, calcium channel blocker [CCB], beta-blocker, and/or diuretic). All BP medications had to be dosed once daily for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, night or rotating-shift work, alcohol or other substance dependence, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, preexisting CVD (unstable angina, heart failure, arrhythmia, kidney failure, and retinopathy), inability to tolerate ABPM, and inability to comply with required 1-year follow-up.

Upon enrollment and at every subsequent clinic visit (scheduled at least annually), participants underwent 48-hour ABPM. Those with uncontrolled BP or elevated CVD risk had scheduled follow-up and ABPM more frequently. The primary outcome was a composite of CVD events including new-onset myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, heart failure, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and CVD death. Secondary endpoints were individually analyzed primary outcomes of CVD events. The typical patient at baseline was 60.5 years of age with a body mass index of 29.7, an almost 9-year duration of hypertension, and a baseline office BP of 149/86 mm Hg. The patient break-out by antihypertensive class (awakening vs bedtime groups) was as follows: ARB (53% vs 53%), ACE inhibitor (25% vs 23%), CCB (33% vs 37%), beta-blocker (22% vs 18%), and diuretic (47% vs 40%).

During the median 6.3-year patient follow-up period, 1752 participants experienced a total of 2454 CVD events. Patients in the bedtime administration group, compared with those in the morning group, showed significantly lower risk for a CVD event (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50-0.61; P < .001). Also, there was a lower risk for individual CVD events in the bedtime administration group: CVD death (HR = 0.44; 95% CI, 0.34-0.56), myocardial infarction (HR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.84), coronary revascularization (HR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.47-0.75), heart failure (HR = 0.58; 95% CI, 0.49-0.70), and stroke (HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.41-0.63). This difference remained after correction for multiple potential confounders. There were no differences in adverse events, such as sleep-time hypotension, between groups.

WHAT’S NEW

First RCT in primary care to show dosing time change reduces CV risk

This is the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) performed in a primary care setting to compare before-bedtime to upon-waking administration of antihypertensive medications using clinically significant endpoints. The study demonstrates that a simple change in administration time has the potential to significantly improve the lives of our patients by reducing the risk for cardiovascular events and their medication burden.

CAVEATS

Homogenous population and exclusions limit generalizability

Because the study population consisted of white Spanish men and women, the results may not be generalizable beyond that ethnic group. In addition, the study exclusions limit interpretation in night/rotating-shift employees, patients with secondary hypertension, and those with CVD, chronic kidney disease, or severe retinopathy looking to reduce their risk.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Nighttime urination could lead to nonadherence

Taking diuretics at bedtime may result in unwanted nighttime awakenings for visits to the bathroom, which could lead to nonadherence in some patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Hermida RC, Crespo JJ, Domínguez-Sardiña M, et al. Bedtime hypertension treatment improves cardiovascular risk reduction: the Hygia Chronotherapy Trial [published online ahead of print October 22, 2019]. Eur Heart J. 2019;ehz754. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz754.

2. Dorans KS, Mills KT, Liu Y, et al. Trends in prevalence and control of hypertension according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008888.

3. Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Smolensky MH, et al. Chronotherapy with conventional blood pressure medications improves management of hypertension and reduces cardiovascular and stroke risks. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:277-292.

4. Bowles NP, Thosar SS, Herzig MX, et al. Chronotherapy for hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20:97.

5. Zhao P, Xu P, Wan C, et al. Evening versus morning dosing regimen drug therapy for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD004184.

6. Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, et al. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients: the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145-153.

7. Black HR, Elliott WJ, Grandits G, et al. Principal results of the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2073-2082.

8. Arnette DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:e177-e232.

9. Foti K, Wang D, Appel LJ, et al. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in US adults: trends in the hypertensive control cascade by population subgroup (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2016). Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188:2165-2174.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 54-year-old White woman presents to your office with new-onset hypertension. As you are discussing options for treatment, she mentions she would prefer once-daily dosing to help her remember to take her medication. She also wants to know what the best time of day is to take her medication to reduce her risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). What do you advise?

The burden of hypertension is significant and growing in the United States. The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines reported that more than 108 million people were affected in 2015-2016—up from 87 million in 1999-2000.2 Yet control of hypertension is improving among those receiving antihypertension pharmacotherapy. As reported in the ACC/AHA guidelines, data from the 2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicate an increase of controlled hypertension among those receiving treatment from 25.6% (1999-2000) to 43.5% (2015-2016).2

Chronotherapy involves the administration of medication in coordination with the body’s circadian rhythms to maximize therapeutic effectiveness and/or minimize adverse effects. It is not a new concept as it applies to hypertension. Circadian rhythm–dependent mechanisms influence the natural rise and fall of blood pressure (BP).1 The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, known to be most active at night, is a target mechanism for BP control.1 Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are more effective (alone or in combination with other agents) at reducing BP during sleep and wakefulness when they are taken at night.3,4 Additional prospective clinical trials and systematic reviews have documented improved BP during sleep and on 24-hour ambulatory monitoring when antihypertensives are taken at bedtime.3-5

However, there have been few long-term studies assessing the effects of bedtime administration of antihypertensive medication on CVD risk reduction with patient-oriented outcomes.6,7 Additionally, no studies have evaluated morning vs bedtime administration of antihypertensive medication for CVD risk reduction in a primary care setting. The 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of CVD offers no recommendation regarding when to take antihypertensive medication.8 Timing of medication administration also is not addressed in the NHANES study of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in US adults.9

This study sought to determine in a primary care setting whether taking antihypertensives at bedtime, as opposed to upon waking, more effectively reduces CVD risk.

STUDY SUMMARY

PM vs AM antihypertensive dosing reduces CV events

This prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint trial of antihypertensive medication administration timing was part of a large, multicenter Spanish study investigating ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) as a routine diagnostic tool.

Study participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to 2 treatment arms; participants either took all of their BP medications in the morning upon waking (n = 9532) or right before bedtime (n = 9552). The study was conducted in a primary care clinical setting. It included adult participants (age ≥ 18 years) with hypertension (defined as having at least 1 of the following benchmarks: awake systolic BP [SBP] mean ≥ 135 mm Hg, awake diastolic BP (DBP) mean ≥ 85 mm Hg, asleep SBP mean ≥ 120 mm Hg, asleep DBP mean ≥ 70 mm Hg as corroborated by 48-hour ABPM) who were taking at least 1 antihypertensive medication.

Continue to: Any antihypertension medication...

Any antihypertension medication included in the Spanish national formulary was allowed (exact agents were not delineated, but the following classes were included: ARB, ACE inhibitor, calcium channel blocker [CCB], beta-blocker, and/or diuretic). All BP medications had to be dosed once daily for inclusion. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, night or rotating-shift work, alcohol or other substance dependence, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, preexisting CVD (unstable angina, heart failure, arrhythmia, kidney failure, and retinopathy), inability to tolerate ABPM, and inability to comply with required 1-year follow-up.

Upon enrollment and at every subsequent clinic visit (scheduled at least annually), participants underwent 48-hour ABPM. Those with uncontrolled BP or elevated CVD risk had scheduled follow-up and ABPM more frequently. The primary outcome was a composite of CVD events including new-onset myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, heart failure, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and CVD death. Secondary endpoints were individually analyzed primary outcomes of CVD events. The typical patient at baseline was 60.5 years of age with a body mass index of 29.7, an almost 9-year duration of hypertension, and a baseline office BP of 149/86 mm Hg. The patient break-out by antihypertensive class (awakening vs bedtime groups) was as follows: ARB (53% vs 53%), ACE inhibitor (25% vs 23%), CCB (33% vs 37%), beta-blocker (22% vs 18%), and diuretic (47% vs 40%).

During the median 6.3-year patient follow-up period, 1752 participants experienced a total of 2454 CVD events. Patients in the bedtime administration group, compared with those in the morning group, showed significantly lower risk for a CVD event (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50-0.61; P < .001). Also, there was a lower risk for individual CVD events in the bedtime administration group: CVD death (HR = 0.44; 95% CI, 0.34-0.56), myocardial infarction (HR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.52-0.84), coronary revascularization (HR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.47-0.75), heart failure (HR = 0.58; 95% CI, 0.49-0.70), and stroke (HR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.41-0.63). This difference remained after correction for multiple potential confounders. There were no differences in adverse events, such as sleep-time hypotension, between groups.

WHAT’S NEW

First RCT in primary care to show dosing time change reduces CV risk

This is the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) performed in a primary care setting to compare before-bedtime to upon-waking administration of antihypertensive medications using clinically significant endpoints. The study demonstrates that a simple change in administration time has the potential to significantly improve the lives of our patients by reducing the risk for cardiovascular events and their medication burden.

CAVEATS

Homogenous population and exclusions limit generalizability

Because the study population consisted of white Spanish men and women, the results may not be generalizable beyond that ethnic group. In addition, the study exclusions limit interpretation in night/rotating-shift employees, patients with secondary hypertension, and those with CVD, chronic kidney disease, or severe retinopathy looking to reduce their risk.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Nighttime urination could lead to nonadherence

Taking diuretics at bedtime may result in unwanted nighttime awakenings for visits to the bathroom, which could lead to nonadherence in some patients.