User login

Few antidepressant adverse effects backed by convincing evidence

Relatively few of the adverse health outcomes attributed to antidepressants are supported by convincing evidence, reported the authors of a systematic review of 45 meta-analyses.

The authors did find convincing evidence linking the use of antidepressants and suicide attempt or completion among people under age 19 years and use of the medication and autism risk among offspring. “However, the few [studies] with convincing evidence associations did not reflect causality, and none of them remained at the convincing evidence level after accounting for confounding by indication,” wrote Elena Dragioti, PhD, of the Pain and Rehabilitation Centre at Linköping (Sweden) University and coauthors. The study was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Dr. Dragioti and coauthors undertook a systematic “umbrella review” grading the evidence from the 45 meta-analyses of 695 observational studies into the association between antidepressant use and the risk of adverse health outcomes. All the meta-analyses included a control group not exposed to antidepressants, with the exception of one that compared the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding between two classes of antidepressants.

They found 120 possible adverse health associations described in the meta-analyses, 61.7% of which related to maternal and pregnancy-related adverse health outcomes. Two-thirds of the adverse health outcome associations involved selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

However, among the 120 adverse health associations, only three (2.5%) were supported by “convincing” evidence. One was the association between SSRIs and increased risk of suicide attempts and completion in children and adolescents. Convincing evidence also was found between any antidepressant use before pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder and between SSRI use during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder. The evidence for the association with suicide risk was deemed high quality, but the two associations with autism spectrum disorder were only of moderate quality.

The authors commented that these findings needed to be considered when prescribing antidepressants in adolescents and children, particularly as another networked meta-analysis had found fluoxetine was the only antidepressant that worked better than placebo in children and adolescents. “In addition, they wrote.

The review found that 11 adverse health outcomes (9.2%) had “highly suggestive” evidence linking them to antidepressant use. These were ADHD in children, cataract development, severe bleeding at any site, upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, postpartum hemorrhage, preterm birth, lower Apgar score at 5 minutes, osteoporotic fracture, and hip fracture.

Seven of those – ADHD in children, lower Apgar score, severe bleeding at any site, cataract development, osteoporotic features, preterm birth, and upper GI bleeding – had moderate-quality evidence. However, the authors noted that the effect sizes were small and had low prevalence.

The study also found highly suggestive evidence linking antidepressant use to a decreased risk of suicide attempts or completion in adults.

The authors said several of those adverse events in adults, such as GI bleeding and osteoporotic fractures, could be prevented with medication, so the advantages of antidepressant use in adults could outweigh the disadvantage of those preventable safety issues.

Twenty-one adverse health outcomes showed either suggestive, weak, or no evidence for their association with antidepressant use.

They also conducted a sensitivity analysis that limited the analysis to cohort studies, prospective cohort studies, studies that controlled for confounding by the treatment indication, and studies from North America. This showed that none of the associations for which there was originally deemed to be convincing evidence retained that same rank.

“Overall, the results showed that the association between antidepressant use and adverse health outcomes was not supported by robust evidence and that the underlying disease likely inflated the findings in a relevant way,” the authors wrote.

However, when they looked solely at prospective cohort studies, the association between preterm birth and use of any antidepressant was upgraded to having convincing evidence.

When the analysis focused on SSRIs only, the association with lower Apgar scores at 5 minutes also was upgraded to having convincing evidence. Similarly, the evidence for an association with preterm birth also was found to be convincing when the analysis was limited to other or mixed antidepressants.

Dr. Dragioti and coauthors cited several limitations, including the inability of some randomized, controlled trials to address adverse outcomes.

“Antidepressant use appears to be safe for the treatment of psychiatric disorders, but more studies matching for underlying disease are needed to clarify the degree of confounding by indication and other biases,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by several entities, including the National Institute for Health Research’s Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Dragioti reported no disclosures. Four authors declared funding, consultancies, personal fees, royalties, or shares in the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Dragioti E et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2859.

Relatively few of the adverse health outcomes attributed to antidepressants are supported by convincing evidence, reported the authors of a systematic review of 45 meta-analyses.

The authors did find convincing evidence linking the use of antidepressants and suicide attempt or completion among people under age 19 years and use of the medication and autism risk among offspring. “However, the few [studies] with convincing evidence associations did not reflect causality, and none of them remained at the convincing evidence level after accounting for confounding by indication,” wrote Elena Dragioti, PhD, of the Pain and Rehabilitation Centre at Linköping (Sweden) University and coauthors. The study was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Dr. Dragioti and coauthors undertook a systematic “umbrella review” grading the evidence from the 45 meta-analyses of 695 observational studies into the association between antidepressant use and the risk of adverse health outcomes. All the meta-analyses included a control group not exposed to antidepressants, with the exception of one that compared the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding between two classes of antidepressants.

They found 120 possible adverse health associations described in the meta-analyses, 61.7% of which related to maternal and pregnancy-related adverse health outcomes. Two-thirds of the adverse health outcome associations involved selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

However, among the 120 adverse health associations, only three (2.5%) were supported by “convincing” evidence. One was the association between SSRIs and increased risk of suicide attempts and completion in children and adolescents. Convincing evidence also was found between any antidepressant use before pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder and between SSRI use during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder. The evidence for the association with suicide risk was deemed high quality, but the two associations with autism spectrum disorder were only of moderate quality.

The authors commented that these findings needed to be considered when prescribing antidepressants in adolescents and children, particularly as another networked meta-analysis had found fluoxetine was the only antidepressant that worked better than placebo in children and adolescents. “In addition, they wrote.

The review found that 11 adverse health outcomes (9.2%) had “highly suggestive” evidence linking them to antidepressant use. These were ADHD in children, cataract development, severe bleeding at any site, upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, postpartum hemorrhage, preterm birth, lower Apgar score at 5 minutes, osteoporotic fracture, and hip fracture.

Seven of those – ADHD in children, lower Apgar score, severe bleeding at any site, cataract development, osteoporotic features, preterm birth, and upper GI bleeding – had moderate-quality evidence. However, the authors noted that the effect sizes were small and had low prevalence.

The study also found highly suggestive evidence linking antidepressant use to a decreased risk of suicide attempts or completion in adults.

The authors said several of those adverse events in adults, such as GI bleeding and osteoporotic fractures, could be prevented with medication, so the advantages of antidepressant use in adults could outweigh the disadvantage of those preventable safety issues.

Twenty-one adverse health outcomes showed either suggestive, weak, or no evidence for their association with antidepressant use.

They also conducted a sensitivity analysis that limited the analysis to cohort studies, prospective cohort studies, studies that controlled for confounding by the treatment indication, and studies from North America. This showed that none of the associations for which there was originally deemed to be convincing evidence retained that same rank.

“Overall, the results showed that the association between antidepressant use and adverse health outcomes was not supported by robust evidence and that the underlying disease likely inflated the findings in a relevant way,” the authors wrote.

However, when they looked solely at prospective cohort studies, the association between preterm birth and use of any antidepressant was upgraded to having convincing evidence.

When the analysis focused on SSRIs only, the association with lower Apgar scores at 5 minutes also was upgraded to having convincing evidence. Similarly, the evidence for an association with preterm birth also was found to be convincing when the analysis was limited to other or mixed antidepressants.

Dr. Dragioti and coauthors cited several limitations, including the inability of some randomized, controlled trials to address adverse outcomes.

“Antidepressant use appears to be safe for the treatment of psychiatric disorders, but more studies matching for underlying disease are needed to clarify the degree of confounding by indication and other biases,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by several entities, including the National Institute for Health Research’s Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Dragioti reported no disclosures. Four authors declared funding, consultancies, personal fees, royalties, or shares in the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Dragioti E et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2859.

Relatively few of the adverse health outcomes attributed to antidepressants are supported by convincing evidence, reported the authors of a systematic review of 45 meta-analyses.

The authors did find convincing evidence linking the use of antidepressants and suicide attempt or completion among people under age 19 years and use of the medication and autism risk among offspring. “However, the few [studies] with convincing evidence associations did not reflect causality, and none of them remained at the convincing evidence level after accounting for confounding by indication,” wrote Elena Dragioti, PhD, of the Pain and Rehabilitation Centre at Linköping (Sweden) University and coauthors. The study was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Dr. Dragioti and coauthors undertook a systematic “umbrella review” grading the evidence from the 45 meta-analyses of 695 observational studies into the association between antidepressant use and the risk of adverse health outcomes. All the meta-analyses included a control group not exposed to antidepressants, with the exception of one that compared the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding between two classes of antidepressants.

They found 120 possible adverse health associations described in the meta-analyses, 61.7% of which related to maternal and pregnancy-related adverse health outcomes. Two-thirds of the adverse health outcome associations involved selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

However, among the 120 adverse health associations, only three (2.5%) were supported by “convincing” evidence. One was the association between SSRIs and increased risk of suicide attempts and completion in children and adolescents. Convincing evidence also was found between any antidepressant use before pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder and between SSRI use during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder. The evidence for the association with suicide risk was deemed high quality, but the two associations with autism spectrum disorder were only of moderate quality.

The authors commented that these findings needed to be considered when prescribing antidepressants in adolescents and children, particularly as another networked meta-analysis had found fluoxetine was the only antidepressant that worked better than placebo in children and adolescents. “In addition, they wrote.

The review found that 11 adverse health outcomes (9.2%) had “highly suggestive” evidence linking them to antidepressant use. These were ADHD in children, cataract development, severe bleeding at any site, upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, postpartum hemorrhage, preterm birth, lower Apgar score at 5 minutes, osteoporotic fracture, and hip fracture.

Seven of those – ADHD in children, lower Apgar score, severe bleeding at any site, cataract development, osteoporotic features, preterm birth, and upper GI bleeding – had moderate-quality evidence. However, the authors noted that the effect sizes were small and had low prevalence.

The study also found highly suggestive evidence linking antidepressant use to a decreased risk of suicide attempts or completion in adults.

The authors said several of those adverse events in adults, such as GI bleeding and osteoporotic fractures, could be prevented with medication, so the advantages of antidepressant use in adults could outweigh the disadvantage of those preventable safety issues.

Twenty-one adverse health outcomes showed either suggestive, weak, or no evidence for their association with antidepressant use.

They also conducted a sensitivity analysis that limited the analysis to cohort studies, prospective cohort studies, studies that controlled for confounding by the treatment indication, and studies from North America. This showed that none of the associations for which there was originally deemed to be convincing evidence retained that same rank.

“Overall, the results showed that the association between antidepressant use and adverse health outcomes was not supported by robust evidence and that the underlying disease likely inflated the findings in a relevant way,” the authors wrote.

However, when they looked solely at prospective cohort studies, the association between preterm birth and use of any antidepressant was upgraded to having convincing evidence.

When the analysis focused on SSRIs only, the association with lower Apgar scores at 5 minutes also was upgraded to having convincing evidence. Similarly, the evidence for an association with preterm birth also was found to be convincing when the analysis was limited to other or mixed antidepressants.

Dr. Dragioti and coauthors cited several limitations, including the inability of some randomized, controlled trials to address adverse outcomes.

“Antidepressant use appears to be safe for the treatment of psychiatric disorders, but more studies matching for underlying disease are needed to clarify the degree of confounding by indication and other biases,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by several entities, including the National Institute for Health Research’s Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Dragioti reported no disclosures. Four authors declared funding, consultancies, personal fees, royalties, or shares in the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Dragioti E et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2859.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: “More studies [of antidepressants] matching for underlying disease are needed to clarify the degree of confounding by indication and other biases.”

Major finding: Increased suicide risk in children and adolescents is one of the few adverse health outcomes of antidepressants that is backed by evidence.

Study details: Systematic umbrella review of 45 meta-analyses of 695 observational studies.

Disclosures: The study was funded by several entities, including the National Institute for Health Research’s Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Dr. Dragioti reported no disclosures. Four authors declared funding, consultancies, personal fees, royalties, or shares in the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Dragioti E et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Oct 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2859.

Premature mortality across most psychiatric disorders

The evidence is robust and disheartening: As if the personal suffering and societal stigma of mental illness are not bad enough, psychiatric patients also have a shorter lifespan.1 In the past, most studies have focused on early mortality and loss of potential life-years in schizophrenia,2 but many subsequent reports indicate that premature death occurs in all major psychiatric disorders.

Here is a summary of the sobering facts:

- Schizophrenia. In a study of 30,210 patients with schizophrenia, compared with >5 million individuals in the general population in Denmark (where they have an excellent registry), mortality was 16-fold higher among patients with schizophrenia if they had a single somatic illness.3 The illnesses were mostly respiratory, gastrointestinal, or cardiovascular).3 The loss of potential years of life was staggeringly high: 18.7 years for men, 16.3 years for women.4 A study conducted in 8 US states reported a loss of 2 to 3 decades of life across each of these states.5 The causes of death in patients with schizophrenia were mainly heart disease, cancer, stroke, and pulmonary diseases. A national database in Sweden found that unmedicated patients with schizophrenia had a significantly higher death rate than those receiving antipsychotics.6,7 Similar findings were reported by researchers in Finland.8 The Swedish study by Tiihonen et al6 also found that mortality was highest in patients receiving benzodiazepines along with antipsychotics, but there was no increased mortality among patients with schizophrenia receiving antidepressants.

- Bipolar disorder. A shorter life expectancy has also been reported in bipolar disorder,9 with a loss of 13.6 years for men and 12.1 years for women. Early death was caused by physical illness (even when suicide deaths were excluded), especially cardiovascular disease.10

- Major depressive disorder (MDD). A reduction of life expectancy in persons with MDD (unipolar depression) has been reported, with a loss of 14 years in men and 10 years in women.11 Although suicide contributed to the shorter lifespan, death due to accidents was 500% higher among persons with unipolar depression; the largest causes of death were physical illnesses. Further, Zubenko et al12 reported alarming findings about excess mortality among first- and second-degree relatives of persons with early-onset depression (some of whom were bipolar). The relatives died an average of 8 years earlier than the local population, and 40% died before reaching age 65. Also, there was a 5-fold increase in infant mortality (in the first year of life) among the relatives. The most common causes of death in adult relatives were heart disease, cancer, and stroke. It is obvious that MDD has a significant negative impact on health and longevity in both patients and their relatives.

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A 220% increase in mortality was reported in persons with ADHD at all ages.13 Accidents were the most common cause of death. The mortality rate ratio (MRR) was 1.86 for ADHD before age 6, 1.58 for ADHD between age 6 to 17, and 4.25 for those age ≥18. The rate of early mortality was higher in girls and women (MRR = 2.85) than boys and men (MRR = 1.27).

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). A study from Denmark of 10,155 persons with OCD followed for 10 years reported a significantly higher risk of death from both natural (MRR = 1.68) and unnatural causes (MRR = 2.61), compared with the general population.14 Patients with OCD and comorbid depression, anxiety, or substance use had a further increase in mortality risk, but the mortality risk of individuals with OCD without psychiatric comorbidity was still 200% higher than that of the general population.

- Anxiety disorders. One study found no increase in mortality among patients who have generalized anxiety, unless it was associated with depression.15 Another study reported that the presence of anxiety reduced the risk of cardiovascular mortality in persons with depression.16 The absence of increased mortality in anxiety disorders was also confirmed in a meta-analysis of 36 studies.17 However, a study of postmenopausal women with panic attacks found a 3-fold increase in coronary artery disease and stroke in that cohort,18 which confirmed the findings of an older study19 that demonstrated a 2-fold increase of mortality among 155 men with panic disorder after a 12-year follow-up. Also, a 25-year follow-up study found that suicide accounted for 20% of deaths in the anxiety group compared with 16.2% in the depression group,20 showing a significant risk of suicide in panic disorder, even exceeding that of depression.

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD). In a 12-year follow-up study of 9,495 individuals with “disruptive behavioral disorders,” which included ODD and CD, the mortality rate was >400% higher in these patients compared with 1.92 million individuals in the general population (9.66 vs 2.22 per 10,000 person-years).21 Comorbid substance use disorder and ADHD further increased the mortality rate in this cohort.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Studies show that there is a significantly increased risk of early cardiovascular mortality in PTSD,22 and that the death rate may be associated with accelerated “DNA methylation age” that leads to a 13% increased risk for all-cause mortality.23

- Borderline personality disorder (BPD). A recent longitudinal study (24 years of follow-up with evaluation every 2 years) reported a significantly higher mortality in patients with BPD compared with those with other personality disorders. The age range when the study started was 18 to 35. The rate of suicide death was Palatino LT Std>400% higher in BPD (5.9% vs 1.4%). Also, non-suicidal death was 250% higher in BPD (14% vs 5.5%). The causes of non-suicidal death included cardiovascular disease, substance-related complications, cancer, and accidents.24

- Other personality disorders. Certain personality traits have been associated with shorter leukocyte telomeres, which signal early death. These traits include neuroticism, conscientiousness, harm avoidance, and reward dependence.25 Another study found shorter telomeres in persons with high neuroticism and low agreeableness26 regardless of age or sex. Short telomeres, which reflect accelerated cellular senescence and aging, have also been reported in several major psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, and anxiety).27-29 The cumulative evidence is unassailable; psychiatric brain disorders are not only associated with premature death due to high suicide rates, but also with multiple medical diseases that lead to early mortality and a shorter lifespan. The shortened telomeres reflect high oxidative stress and inflammation, and both those toxic processes are known to be associated with major psychiatric disorders. Compounding the dismal facts about early mortality due to mental illness are the additional grave medical consequences of alcohol and substance use, which are highly comorbid with most psychiatric disorders, further exacerbating the premature death rates among psychiatric patients.

Continue to: There is an important take-home message...

There is an important take-home message in all of this: Our patients are at high risk for potentially fatal medical conditions that require early detection, and intensive ongoing treatment by a primary care clinician (not “provider”; I abhor the widespread use of that term for physicians or nurse practitioners) is an indispensable component of psychiatric care. Thus, collaborative care is vital to protect our psychiatric patients from early mortality and a shortened lifespan. Psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners must not only win the battle against mental illness, but also diligently avoid losing the war of life and death.

1. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334-341.

2. Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067133.

3. Kugathasan P, Stubbs B, Aagaard J, et al. Increased mortality from somatic multimorbidity in patients with schizophrenia: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019. doi: 10.1111/acps.13076.

4. Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):101-104.

5. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

6. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

7. Torniainen M, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tanskanen A, et al. Antipsychotic treatment and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):656-663.

8. Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374(9690):620-627.

9. Wilson R, Gaughran F, Whitburn T, et al. Place of death and other factors associated with unnatural mortality in patients with serious mental disorders: population-based retrospective cohort study. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(2):e23. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.5.

10. Ösby U, Westman J, Hällgren J, et al. Mortality trends in cardiovascular causes in schizophrenia, bipolar and unipolar mood disorder in Sweden 1987-2010. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(5):867-871.

11. Laursen TM, Musliner KL, Benros ME, et al. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:203-207.

12. Zubenko GS, Zubenko WN, Spiker DG, et al. Malignancy of recurrent, early-onset major depression: a family study. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(8):690-699.

13. Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, et al. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190-2196.

14. Meier SM, Mattheisen M, Mors O, et al. Mortality among persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):268-274.

15. Holwerda TJ, Schoevers RA, Dekker J, et al. The relationship between generalized anxiety disorder, depression and mortality in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):241-249.

16. Ivanovs R, Kivite A, Ziedonis D, et al. Association of depression and anxiety with the 10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality in a primary care population of Latvia using the SCORE system. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:276.

17. Miloyan B, Bulley A, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Anxiety disorders and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1467-1475.

18. Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Panic attacks and risk of incident cardiovascular events among postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1153-1160.

19. Coryell W, Noyes R Jr, House JD. Mortality among outpatients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(4):508-510.

20. Coryell W, Noyes R, Clancy J. Excess mortality in panic disorder. A comparison with primary unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(6):701-703.

21. Scott JG, Giørtz Pedersen M, Erskine HE, et al. Mortality in individuals with disruptive behavior disorders diagnosed by specialist services - a nationwide cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:255-260.

22. Burg MM, Soufer R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(10):94.

23. Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Stoop TB, et al. Accelerated DNA methylation age: associations with PTSD and mortality. Psychosom Med. 2017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000506.

24. Temes CM, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice MC, et al. Deaths by suicide and other causes among patients with borderline personality disorder and personality-disordered comparison subjects over 24 years of prospective follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12436.

25. Sadahiro R, Suzuki A, Enokido M, et al. Relationship between leukocyte telomere length and personality traits in healthy subjects. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):291-295.

26. Schoormans D, Verhoeven JE, Denollet J, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and personality: associations with the Big Five and Type D personality traits. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):1008-1019.

27. Muneer A, Minhas FA. Telomere biology in mood disorders: an updated, comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2019;17(3):343-363.

28. Vakonaki E, Tsiminikaki K, Plaitis S, et al. Common mental disorders and association with telomere length. Biomed Rep. 2018;8(2):111-116.

29. Malouff

The evidence is robust and disheartening: As if the personal suffering and societal stigma of mental illness are not bad enough, psychiatric patients also have a shorter lifespan.1 In the past, most studies have focused on early mortality and loss of potential life-years in schizophrenia,2 but many subsequent reports indicate that premature death occurs in all major psychiatric disorders.

Here is a summary of the sobering facts:

- Schizophrenia. In a study of 30,210 patients with schizophrenia, compared with >5 million individuals in the general population in Denmark (where they have an excellent registry), mortality was 16-fold higher among patients with schizophrenia if they had a single somatic illness.3 The illnesses were mostly respiratory, gastrointestinal, or cardiovascular).3 The loss of potential years of life was staggeringly high: 18.7 years for men, 16.3 years for women.4 A study conducted in 8 US states reported a loss of 2 to 3 decades of life across each of these states.5 The causes of death in patients with schizophrenia were mainly heart disease, cancer, stroke, and pulmonary diseases. A national database in Sweden found that unmedicated patients with schizophrenia had a significantly higher death rate than those receiving antipsychotics.6,7 Similar findings were reported by researchers in Finland.8 The Swedish study by Tiihonen et al6 also found that mortality was highest in patients receiving benzodiazepines along with antipsychotics, but there was no increased mortality among patients with schizophrenia receiving antidepressants.

- Bipolar disorder. A shorter life expectancy has also been reported in bipolar disorder,9 with a loss of 13.6 years for men and 12.1 years for women. Early death was caused by physical illness (even when suicide deaths were excluded), especially cardiovascular disease.10

- Major depressive disorder (MDD). A reduction of life expectancy in persons with MDD (unipolar depression) has been reported, with a loss of 14 years in men and 10 years in women.11 Although suicide contributed to the shorter lifespan, death due to accidents was 500% higher among persons with unipolar depression; the largest causes of death were physical illnesses. Further, Zubenko et al12 reported alarming findings about excess mortality among first- and second-degree relatives of persons with early-onset depression (some of whom were bipolar). The relatives died an average of 8 years earlier than the local population, and 40% died before reaching age 65. Also, there was a 5-fold increase in infant mortality (in the first year of life) among the relatives. The most common causes of death in adult relatives were heart disease, cancer, and stroke. It is obvious that MDD has a significant negative impact on health and longevity in both patients and their relatives.

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A 220% increase in mortality was reported in persons with ADHD at all ages.13 Accidents were the most common cause of death. The mortality rate ratio (MRR) was 1.86 for ADHD before age 6, 1.58 for ADHD between age 6 to 17, and 4.25 for those age ≥18. The rate of early mortality was higher in girls and women (MRR = 2.85) than boys and men (MRR = 1.27).

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). A study from Denmark of 10,155 persons with OCD followed for 10 years reported a significantly higher risk of death from both natural (MRR = 1.68) and unnatural causes (MRR = 2.61), compared with the general population.14 Patients with OCD and comorbid depression, anxiety, or substance use had a further increase in mortality risk, but the mortality risk of individuals with OCD without psychiatric comorbidity was still 200% higher than that of the general population.

- Anxiety disorders. One study found no increase in mortality among patients who have generalized anxiety, unless it was associated with depression.15 Another study reported that the presence of anxiety reduced the risk of cardiovascular mortality in persons with depression.16 The absence of increased mortality in anxiety disorders was also confirmed in a meta-analysis of 36 studies.17 However, a study of postmenopausal women with panic attacks found a 3-fold increase in coronary artery disease and stroke in that cohort,18 which confirmed the findings of an older study19 that demonstrated a 2-fold increase of mortality among 155 men with panic disorder after a 12-year follow-up. Also, a 25-year follow-up study found that suicide accounted for 20% of deaths in the anxiety group compared with 16.2% in the depression group,20 showing a significant risk of suicide in panic disorder, even exceeding that of depression.

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD). In a 12-year follow-up study of 9,495 individuals with “disruptive behavioral disorders,” which included ODD and CD, the mortality rate was >400% higher in these patients compared with 1.92 million individuals in the general population (9.66 vs 2.22 per 10,000 person-years).21 Comorbid substance use disorder and ADHD further increased the mortality rate in this cohort.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Studies show that there is a significantly increased risk of early cardiovascular mortality in PTSD,22 and that the death rate may be associated with accelerated “DNA methylation age” that leads to a 13% increased risk for all-cause mortality.23

- Borderline personality disorder (BPD). A recent longitudinal study (24 years of follow-up with evaluation every 2 years) reported a significantly higher mortality in patients with BPD compared with those with other personality disorders. The age range when the study started was 18 to 35. The rate of suicide death was Palatino LT Std>400% higher in BPD (5.9% vs 1.4%). Also, non-suicidal death was 250% higher in BPD (14% vs 5.5%). The causes of non-suicidal death included cardiovascular disease, substance-related complications, cancer, and accidents.24

- Other personality disorders. Certain personality traits have been associated with shorter leukocyte telomeres, which signal early death. These traits include neuroticism, conscientiousness, harm avoidance, and reward dependence.25 Another study found shorter telomeres in persons with high neuroticism and low agreeableness26 regardless of age or sex. Short telomeres, which reflect accelerated cellular senescence and aging, have also been reported in several major psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, and anxiety).27-29 The cumulative evidence is unassailable; psychiatric brain disorders are not only associated with premature death due to high suicide rates, but also with multiple medical diseases that lead to early mortality and a shorter lifespan. The shortened telomeres reflect high oxidative stress and inflammation, and both those toxic processes are known to be associated with major psychiatric disorders. Compounding the dismal facts about early mortality due to mental illness are the additional grave medical consequences of alcohol and substance use, which are highly comorbid with most psychiatric disorders, further exacerbating the premature death rates among psychiatric patients.

Continue to: There is an important take-home message...

There is an important take-home message in all of this: Our patients are at high risk for potentially fatal medical conditions that require early detection, and intensive ongoing treatment by a primary care clinician (not “provider”; I abhor the widespread use of that term for physicians or nurse practitioners) is an indispensable component of psychiatric care. Thus, collaborative care is vital to protect our psychiatric patients from early mortality and a shortened lifespan. Psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners must not only win the battle against mental illness, but also diligently avoid losing the war of life and death.

The evidence is robust and disheartening: As if the personal suffering and societal stigma of mental illness are not bad enough, psychiatric patients also have a shorter lifespan.1 In the past, most studies have focused on early mortality and loss of potential life-years in schizophrenia,2 but many subsequent reports indicate that premature death occurs in all major psychiatric disorders.

Here is a summary of the sobering facts:

- Schizophrenia. In a study of 30,210 patients with schizophrenia, compared with >5 million individuals in the general population in Denmark (where they have an excellent registry), mortality was 16-fold higher among patients with schizophrenia if they had a single somatic illness.3 The illnesses were mostly respiratory, gastrointestinal, or cardiovascular).3 The loss of potential years of life was staggeringly high: 18.7 years for men, 16.3 years for women.4 A study conducted in 8 US states reported a loss of 2 to 3 decades of life across each of these states.5 The causes of death in patients with schizophrenia were mainly heart disease, cancer, stroke, and pulmonary diseases. A national database in Sweden found that unmedicated patients with schizophrenia had a significantly higher death rate than those receiving antipsychotics.6,7 Similar findings were reported by researchers in Finland.8 The Swedish study by Tiihonen et al6 also found that mortality was highest in patients receiving benzodiazepines along with antipsychotics, but there was no increased mortality among patients with schizophrenia receiving antidepressants.

- Bipolar disorder. A shorter life expectancy has also been reported in bipolar disorder,9 with a loss of 13.6 years for men and 12.1 years for women. Early death was caused by physical illness (even when suicide deaths were excluded), especially cardiovascular disease.10

- Major depressive disorder (MDD). A reduction of life expectancy in persons with MDD (unipolar depression) has been reported, with a loss of 14 years in men and 10 years in women.11 Although suicide contributed to the shorter lifespan, death due to accidents was 500% higher among persons with unipolar depression; the largest causes of death were physical illnesses. Further, Zubenko et al12 reported alarming findings about excess mortality among first- and second-degree relatives of persons with early-onset depression (some of whom were bipolar). The relatives died an average of 8 years earlier than the local population, and 40% died before reaching age 65. Also, there was a 5-fold increase in infant mortality (in the first year of life) among the relatives. The most common causes of death in adult relatives were heart disease, cancer, and stroke. It is obvious that MDD has a significant negative impact on health and longevity in both patients and their relatives.

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A 220% increase in mortality was reported in persons with ADHD at all ages.13 Accidents were the most common cause of death. The mortality rate ratio (MRR) was 1.86 for ADHD before age 6, 1.58 for ADHD between age 6 to 17, and 4.25 for those age ≥18. The rate of early mortality was higher in girls and women (MRR = 2.85) than boys and men (MRR = 1.27).

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). A study from Denmark of 10,155 persons with OCD followed for 10 years reported a significantly higher risk of death from both natural (MRR = 1.68) and unnatural causes (MRR = 2.61), compared with the general population.14 Patients with OCD and comorbid depression, anxiety, or substance use had a further increase in mortality risk, but the mortality risk of individuals with OCD without psychiatric comorbidity was still 200% higher than that of the general population.

- Anxiety disorders. One study found no increase in mortality among patients who have generalized anxiety, unless it was associated with depression.15 Another study reported that the presence of anxiety reduced the risk of cardiovascular mortality in persons with depression.16 The absence of increased mortality in anxiety disorders was also confirmed in a meta-analysis of 36 studies.17 However, a study of postmenopausal women with panic attacks found a 3-fold increase in coronary artery disease and stroke in that cohort,18 which confirmed the findings of an older study19 that demonstrated a 2-fold increase of mortality among 155 men with panic disorder after a 12-year follow-up. Also, a 25-year follow-up study found that suicide accounted for 20% of deaths in the anxiety group compared with 16.2% in the depression group,20 showing a significant risk of suicide in panic disorder, even exceeding that of depression.

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD). In a 12-year follow-up study of 9,495 individuals with “disruptive behavioral disorders,” which included ODD and CD, the mortality rate was >400% higher in these patients compared with 1.92 million individuals in the general population (9.66 vs 2.22 per 10,000 person-years).21 Comorbid substance use disorder and ADHD further increased the mortality rate in this cohort.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Studies show that there is a significantly increased risk of early cardiovascular mortality in PTSD,22 and that the death rate may be associated with accelerated “DNA methylation age” that leads to a 13% increased risk for all-cause mortality.23

- Borderline personality disorder (BPD). A recent longitudinal study (24 years of follow-up with evaluation every 2 years) reported a significantly higher mortality in patients with BPD compared with those with other personality disorders. The age range when the study started was 18 to 35. The rate of suicide death was Palatino LT Std>400% higher in BPD (5.9% vs 1.4%). Also, non-suicidal death was 250% higher in BPD (14% vs 5.5%). The causes of non-suicidal death included cardiovascular disease, substance-related complications, cancer, and accidents.24

- Other personality disorders. Certain personality traits have been associated with shorter leukocyte telomeres, which signal early death. These traits include neuroticism, conscientiousness, harm avoidance, and reward dependence.25 Another study found shorter telomeres in persons with high neuroticism and low agreeableness26 regardless of age or sex. Short telomeres, which reflect accelerated cellular senescence and aging, have also been reported in several major psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, and anxiety).27-29 The cumulative evidence is unassailable; psychiatric brain disorders are not only associated with premature death due to high suicide rates, but also with multiple medical diseases that lead to early mortality and a shorter lifespan. The shortened telomeres reflect high oxidative stress and inflammation, and both those toxic processes are known to be associated with major psychiatric disorders. Compounding the dismal facts about early mortality due to mental illness are the additional grave medical consequences of alcohol and substance use, which are highly comorbid with most psychiatric disorders, further exacerbating the premature death rates among psychiatric patients.

Continue to: There is an important take-home message...

There is an important take-home message in all of this: Our patients are at high risk for potentially fatal medical conditions that require early detection, and intensive ongoing treatment by a primary care clinician (not “provider”; I abhor the widespread use of that term for physicians or nurse practitioners) is an indispensable component of psychiatric care. Thus, collaborative care is vital to protect our psychiatric patients from early mortality and a shortened lifespan. Psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioners must not only win the battle against mental illness, but also diligently avoid losing the war of life and death.

1. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334-341.

2. Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067133.

3. Kugathasan P, Stubbs B, Aagaard J, et al. Increased mortality from somatic multimorbidity in patients with schizophrenia: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019. doi: 10.1111/acps.13076.

4. Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):101-104.

5. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

6. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

7. Torniainen M, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tanskanen A, et al. Antipsychotic treatment and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):656-663.

8. Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374(9690):620-627.

9. Wilson R, Gaughran F, Whitburn T, et al. Place of death and other factors associated with unnatural mortality in patients with serious mental disorders: population-based retrospective cohort study. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(2):e23. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.5.

10. Ösby U, Westman J, Hällgren J, et al. Mortality trends in cardiovascular causes in schizophrenia, bipolar and unipolar mood disorder in Sweden 1987-2010. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(5):867-871.

11. Laursen TM, Musliner KL, Benros ME, et al. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:203-207.

12. Zubenko GS, Zubenko WN, Spiker DG, et al. Malignancy of recurrent, early-onset major depression: a family study. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(8):690-699.

13. Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, et al. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190-2196.

14. Meier SM, Mattheisen M, Mors O, et al. Mortality among persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):268-274.

15. Holwerda TJ, Schoevers RA, Dekker J, et al. The relationship between generalized anxiety disorder, depression and mortality in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):241-249.

16. Ivanovs R, Kivite A, Ziedonis D, et al. Association of depression and anxiety with the 10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality in a primary care population of Latvia using the SCORE system. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:276.

17. Miloyan B, Bulley A, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Anxiety disorders and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1467-1475.

18. Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Panic attacks and risk of incident cardiovascular events among postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1153-1160.

19. Coryell W, Noyes R Jr, House JD. Mortality among outpatients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(4):508-510.

20. Coryell W, Noyes R, Clancy J. Excess mortality in panic disorder. A comparison with primary unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(6):701-703.

21. Scott JG, Giørtz Pedersen M, Erskine HE, et al. Mortality in individuals with disruptive behavior disorders diagnosed by specialist services - a nationwide cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:255-260.

22. Burg MM, Soufer R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(10):94.

23. Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Stoop TB, et al. Accelerated DNA methylation age: associations with PTSD and mortality. Psychosom Med. 2017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000506.

24. Temes CM, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice MC, et al. Deaths by suicide and other causes among patients with borderline personality disorder and personality-disordered comparison subjects over 24 years of prospective follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12436.

25. Sadahiro R, Suzuki A, Enokido M, et al. Relationship between leukocyte telomere length and personality traits in healthy subjects. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):291-295.

26. Schoormans D, Verhoeven JE, Denollet J, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and personality: associations with the Big Five and Type D personality traits. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):1008-1019.

27. Muneer A, Minhas FA. Telomere biology in mood disorders: an updated, comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2019;17(3):343-363.

28. Vakonaki E, Tsiminikaki K, Plaitis S, et al. Common mental disorders and association with telomere length. Biomed Rep. 2018;8(2):111-116.

29. Malouff

1. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334-341.

2. Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067133.

3. Kugathasan P, Stubbs B, Aagaard J, et al. Increased mortality from somatic multimorbidity in patients with schizophrenia: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019. doi: 10.1111/acps.13076.

4. Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):101-104.

5. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

6. Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600-606.

7. Torniainen M, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tanskanen A, et al. Antipsychotic treatment and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):656-663.

8. Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, et al. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study). Lancet. 2009;374(9690):620-627.

9. Wilson R, Gaughran F, Whitburn T, et al. Place of death and other factors associated with unnatural mortality in patients with serious mental disorders: population-based retrospective cohort study. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(2):e23. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.5.

10. Ösby U, Westman J, Hällgren J, et al. Mortality trends in cardiovascular causes in schizophrenia, bipolar and unipolar mood disorder in Sweden 1987-2010. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(5):867-871.

11. Laursen TM, Musliner KL, Benros ME, et al. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:203-207.

12. Zubenko GS, Zubenko WN, Spiker DG, et al. Malignancy of recurrent, early-onset major depression: a family study. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105(8):690-699.

13. Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, et al. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190-2196.

14. Meier SM, Mattheisen M, Mors O, et al. Mortality among persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder in Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):268-274.

15. Holwerda TJ, Schoevers RA, Dekker J, et al. The relationship between generalized anxiety disorder, depression and mortality in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):241-249.

16. Ivanovs R, Kivite A, Ziedonis D, et al. Association of depression and anxiety with the 10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality in a primary care population of Latvia using the SCORE system. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:276.

17. Miloyan B, Bulley A, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Anxiety disorders and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(11):1467-1475.

18. Smoller JW, Pollack MH, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. Panic attacks and risk of incident cardiovascular events among postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1153-1160.

19. Coryell W, Noyes R Jr, House JD. Mortality among outpatients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(4):508-510.

20. Coryell W, Noyes R, Clancy J. Excess mortality in panic disorder. A comparison with primary unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(6):701-703.

21. Scott JG, Giørtz Pedersen M, Erskine HE, et al. Mortality in individuals with disruptive behavior disorders diagnosed by specialist services - a nationwide cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:255-260.

22. Burg MM, Soufer R. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18(10):94.

23. Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Stoop TB, et al. Accelerated DNA methylation age: associations with PTSD and mortality. Psychosom Med. 2017. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000506.

24. Temes CM, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice MC, et al. Deaths by suicide and other causes among patients with borderline personality disorder and personality-disordered comparison subjects over 24 years of prospective follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12436.

25. Sadahiro R, Suzuki A, Enokido M, et al. Relationship between leukocyte telomere length and personality traits in healthy subjects. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):291-295.

26. Schoormans D, Verhoeven JE, Denollet J, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and personality: associations with the Big Five and Type D personality traits. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):1008-1019.

27. Muneer A, Minhas FA. Telomere biology in mood disorders: an updated, comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2019;17(3):343-363.

28. Vakonaki E, Tsiminikaki K, Plaitis S, et al. Common mental disorders and association with telomere length. Biomed Rep. 2018;8(2):111-116.

29. Malouff

Physician burnout vs depression: Recognize the signs

Although all health care professionals are at risk for burnout, physicians have especially high rates of self-reported burnout—which is commonly understood as a work-related syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of accomplishment that develops over time.1 In a 2019 report investigating burnout in approximately 15,000 physicians, 39% of psychiatrists and nearly 50% of physicians from multiple other specialities described themselves as “burned out.”2 In addition, 15% reported symptoms of clinical depression (4%) or subclinical depression (11%). In comparison, in 2017, 7.1% of US adults experienced at least 1 major depressive episode.3 Because physician burnout and depression can be associated with adverse outcomes in patient care and personal health, rapid identification and differentiation of the 2 conditions is paramount.

Differentiating burnout and depression

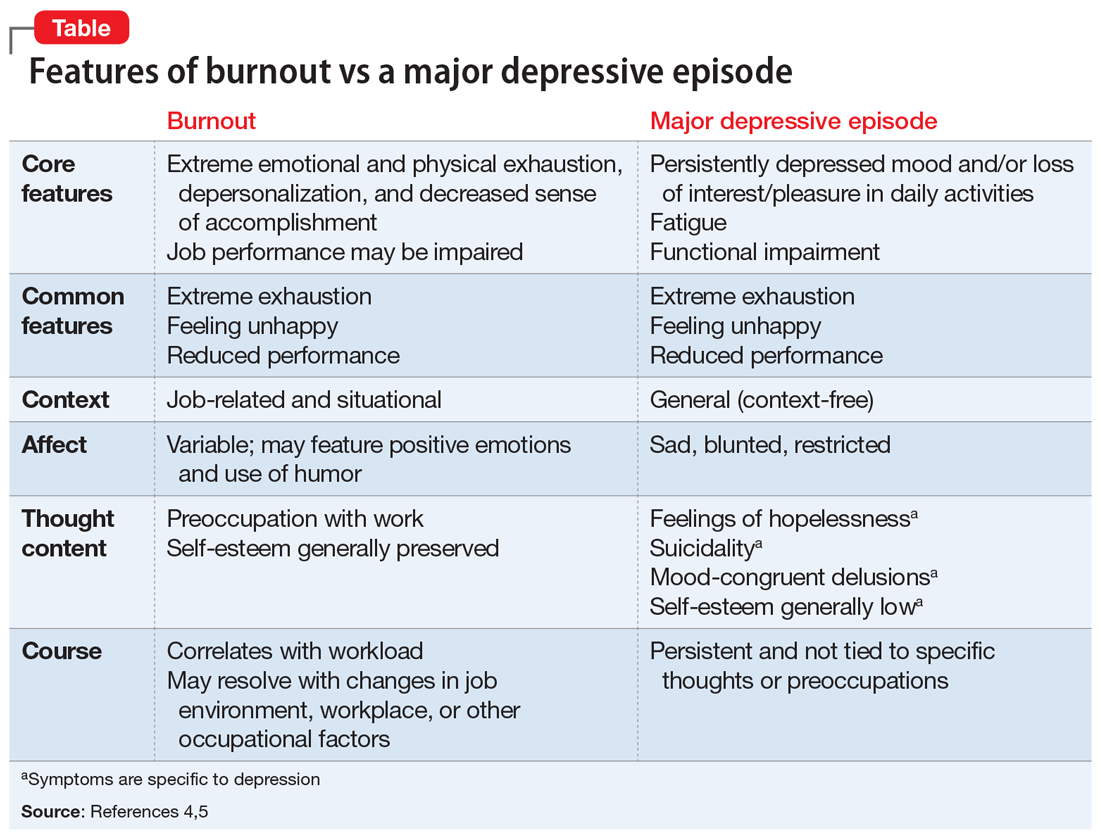

Burnout and depression are distinct but overlapping entities. Although burnout can be difficult to recognize and is not currently a DSM diagnosis, physicians can learn to identify the signs with reference to the more familiar features of depression (Table4,5). Many features of burnout are work-related, while the negative feelings and thoughts of depression pertain to all areas of life. Furthermore, a major depressive episode often includes hopelessness, suicidality, or mood-congruent delusions; burnout does not. Shared symptoms of burnout and depression include extreme exhaustion, feeling unhappy, and reduced performance.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of burnout.4,5 Some researchers have proposed that physicians who are categorized as “burned out” may actually have underlying anxiety or depressive disorders that have been misdiagnosed and not appropriately treated.4,5 Others claim that burnout is best formulated as a depressive condition in need of formal diagnostic criteria.4,5 Because the definition of burnout is in question,4,5 strategies to prevent and detect burnout in individual clinicians remain elusive.

Key areas that contribute to vulnerability to burnout include one’s sense of community, fairness, and control in the workplace; personal and organization values; and work-life balance. We propose the mnemonic WORK to help clinicians quickly assess their vulnerability to burnout in these areas.

Workload. Outside of working hours, are you satisfied with the amount of time you devote to self-care, recreation, and other activities that are important to you? Do you honor your “down time”?

Oversight. Are you satisfied with the flexibility and autonomy in your professional life? Are you able to cope with the systemic demands of your practice while upholding your priorities within these restrictions?

Reward. Are the mechanisms for feedback, opportunities for advancement, and financial compensation in your workplace fair? Do you find positive meaning in the work that you do?

Continue to: Kinship

Kinship. Does your place of work support cooperation and collaboration, rather than competition and isolation? Do you approach and receive support from your colleagues when you need assistance?

Persistent dissatisfaction in any of these aspects should prompt clinicians to further develop strategies that promote workplace engagement, job satisfaction, and resilience. We hope this mnemonic helps clinicians to take responsibility for their own well-being and ultimately reap the rewards of a fulfilling professional life.

1. Brindley P. Psychological burnout and the intensive care practitioner: a practical and candid review for those who care. J Inten Care Soc. 2017;18(4):270-275.

2. Kane L. Medscape national physician b urnout & depression report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Updated February 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Messias E, Flynn V. The tired, retired, and recovered physician: professional burnout versus major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):716-719.

5. Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD. In reply—defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(9):1456-1458.

Although all health care professionals are at risk for burnout, physicians have especially high rates of self-reported burnout—which is commonly understood as a work-related syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of accomplishment that develops over time.1 In a 2019 report investigating burnout in approximately 15,000 physicians, 39% of psychiatrists and nearly 50% of physicians from multiple other specialities described themselves as “burned out.”2 In addition, 15% reported symptoms of clinical depression (4%) or subclinical depression (11%). In comparison, in 2017, 7.1% of US adults experienced at least 1 major depressive episode.3 Because physician burnout and depression can be associated with adverse outcomes in patient care and personal health, rapid identification and differentiation of the 2 conditions is paramount.

Differentiating burnout and depression

Burnout and depression are distinct but overlapping entities. Although burnout can be difficult to recognize and is not currently a DSM diagnosis, physicians can learn to identify the signs with reference to the more familiar features of depression (Table4,5). Many features of burnout are work-related, while the negative feelings and thoughts of depression pertain to all areas of life. Furthermore, a major depressive episode often includes hopelessness, suicidality, or mood-congruent delusions; burnout does not. Shared symptoms of burnout and depression include extreme exhaustion, feeling unhappy, and reduced performance.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of burnout.4,5 Some researchers have proposed that physicians who are categorized as “burned out” may actually have underlying anxiety or depressive disorders that have been misdiagnosed and not appropriately treated.4,5 Others claim that burnout is best formulated as a depressive condition in need of formal diagnostic criteria.4,5 Because the definition of burnout is in question,4,5 strategies to prevent and detect burnout in individual clinicians remain elusive.

Key areas that contribute to vulnerability to burnout include one’s sense of community, fairness, and control in the workplace; personal and organization values; and work-life balance. We propose the mnemonic WORK to help clinicians quickly assess their vulnerability to burnout in these areas.

Workload. Outside of working hours, are you satisfied with the amount of time you devote to self-care, recreation, and other activities that are important to you? Do you honor your “down time”?

Oversight. Are you satisfied with the flexibility and autonomy in your professional life? Are you able to cope with the systemic demands of your practice while upholding your priorities within these restrictions?

Reward. Are the mechanisms for feedback, opportunities for advancement, and financial compensation in your workplace fair? Do you find positive meaning in the work that you do?

Continue to: Kinship

Kinship. Does your place of work support cooperation and collaboration, rather than competition and isolation? Do you approach and receive support from your colleagues when you need assistance?

Persistent dissatisfaction in any of these aspects should prompt clinicians to further develop strategies that promote workplace engagement, job satisfaction, and resilience. We hope this mnemonic helps clinicians to take responsibility for their own well-being and ultimately reap the rewards of a fulfilling professional life.

Although all health care professionals are at risk for burnout, physicians have especially high rates of self-reported burnout—which is commonly understood as a work-related syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of accomplishment that develops over time.1 In a 2019 report investigating burnout in approximately 15,000 physicians, 39% of psychiatrists and nearly 50% of physicians from multiple other specialities described themselves as “burned out.”2 In addition, 15% reported symptoms of clinical depression (4%) or subclinical depression (11%). In comparison, in 2017, 7.1% of US adults experienced at least 1 major depressive episode.3 Because physician burnout and depression can be associated with adverse outcomes in patient care and personal health, rapid identification and differentiation of the 2 conditions is paramount.

Differentiating burnout and depression

Burnout and depression are distinct but overlapping entities. Although burnout can be difficult to recognize and is not currently a DSM diagnosis, physicians can learn to identify the signs with reference to the more familiar features of depression (Table4,5). Many features of burnout are work-related, while the negative feelings and thoughts of depression pertain to all areas of life. Furthermore, a major depressive episode often includes hopelessness, suicidality, or mood-congruent delusions; burnout does not. Shared symptoms of burnout and depression include extreme exhaustion, feeling unhappy, and reduced performance.

Surprisingly, there is no universally accepted definition of burnout.4,5 Some researchers have proposed that physicians who are categorized as “burned out” may actually have underlying anxiety or depressive disorders that have been misdiagnosed and not appropriately treated.4,5 Others claim that burnout is best formulated as a depressive condition in need of formal diagnostic criteria.4,5 Because the definition of burnout is in question,4,5 strategies to prevent and detect burnout in individual clinicians remain elusive.

Key areas that contribute to vulnerability to burnout include one’s sense of community, fairness, and control in the workplace; personal and organization values; and work-life balance. We propose the mnemonic WORK to help clinicians quickly assess their vulnerability to burnout in these areas.

Workload. Outside of working hours, are you satisfied with the amount of time you devote to self-care, recreation, and other activities that are important to you? Do you honor your “down time”?

Oversight. Are you satisfied with the flexibility and autonomy in your professional life? Are you able to cope with the systemic demands of your practice while upholding your priorities within these restrictions?

Reward. Are the mechanisms for feedback, opportunities for advancement, and financial compensation in your workplace fair? Do you find positive meaning in the work that you do?

Continue to: Kinship

Kinship. Does your place of work support cooperation and collaboration, rather than competition and isolation? Do you approach and receive support from your colleagues when you need assistance?

Persistent dissatisfaction in any of these aspects should prompt clinicians to further develop strategies that promote workplace engagement, job satisfaction, and resilience. We hope this mnemonic helps clinicians to take responsibility for their own well-being and ultimately reap the rewards of a fulfilling professional life.

1. Brindley P. Psychological burnout and the intensive care practitioner: a practical and candid review for those who care. J Inten Care Soc. 2017;18(4):270-275.

2. Kane L. Medscape national physician b urnout & depression report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Updated February 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Messias E, Flynn V. The tired, retired, and recovered physician: professional burnout versus major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):716-719.

5. Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD. In reply—defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(9):1456-1458.

1. Brindley P. Psychological burnout and the intensive care practitioner: a practical and candid review for those who care. J Inten Care Soc. 2017;18(4):270-275.

2. Kane L. Medscape national physician b urnout & depression report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056#1. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

3. National Institute of Mental Health. Prevalence of major depressive episode among adults. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml. Updated February 2019. Accessed September 17, 2019.

4. Messias E, Flynn V. The tired, retired, and recovered physician: professional burnout versus major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):716-719.

5. Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD. In reply—defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92(9):1456-1458.

Four genetic variants link psychotic experiences to multiple mental disorders

Four genetic variations appear to link psychotic experiences with other psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and neurodevelopmental disorders, a large genetic study has concluded.

, reported Sophie E. Legge, PhD, and colleagues. Their study was published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Although it is informative, the study is unlikely to expand the knowledge of schizophrenia-specific genetics.

“Consistent with other studies, the heritability estimate (1.71%) was low, and given that the variance explained in our polygenic risk analysis was also low, the finding suggests that understanding the genetics of psychotic experiences is unlikely to have an important effect on understanding the genetics of schizophrenia specifically,” wrote Dr. Legge, of the MRC Center for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics in the division of psychological medicine and clinical neurosciences at Cardiff (Wales) University, and colleagues.

The team conducted a genomewide association study (GWAS) using data from 127,966 individuals in the U.K. Biobank. Of these, 6,123 reported any psychotic experience, 2,143 reported distressing psychotic experiences, and 3,337 reported multiple experiences. The remainder served as controls. At the time of the biobank data collection, the subjects were a mean of 64 years of age; 56% were women.

First psychotic experience occurred at a mean of almost 32 years of age, but about a third reported that the first episode occurred before age 20, or that psychotic experiences had been happening ever since they could remember. Another third reported their first experience between ages 40 and 76 years.

The investigators conducted three GWAS studies: one for any psychotic experience, one for distressing experiences, and one for multiple experiences.

No significant genetic associations were found among those with multiple psychotic experiences, the authors said.

But they did find four variants significantly associated with the other experience categories.

Two variants were associated with any psychotic experience. Those with rs10994278, an intronic variant within Ankyrin-3 (ANK3), were 16% more likely to have a psychotic experience (odds ratio, 1.16). Those with intergenic variant rs549656827 were 39% less likely (OR, 0.61). “The ANK3 gene encodes ankyrin-G, a protein that has been shown to regulate the assembly of voltage-gated sodium channels and is essential for normal synaptic function,” the authors said. “ANK3 is one of strongest and most replicated genes for bipolar disorder, and variants within ANK3 have also been associated in the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium cross-disorder GWAS, and in a rare variant analysis of autism spectrum disorder.”

Two variants were linked to distressing psychotic experiences: rs75459873, intronic to cannabinoid receptor 2 (CNR2), decreased the risk by 34% (OR, 0.66). Intergenic variant rs3849810 increased the risk by 12% (OR, 1.12).

“CNR2 encodes for CB2, one of two well-characterized cannabinoid receptors. Several lines of evidence have implicated the endocannabinoid system in psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and depression. The main psychoactive agent of cannabis, tetrahydrocannabinol, can cause acute psychotic symptoms and cognitive impairment. Given that cannabis use is strongly associated with psychotic experiences, we tested, but found no evidence for, a mediating or moderating effect of cannabis use on the association of rs75459873 and distressing psychotic experiences. However, while no evidence was found in this study, a mediating effect of cannabis use cannot be ruled out given the relatively low power of such analyses and the potential measurement error.”

Also, significant genetic correlations were found between any psychotic experiences and major depressive disorder, autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, and schizophrenia. However, the polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, ADHD, and autism spectrum disorder, were low.

“We also considered individual psychotic symptoms and found that polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and ADHD were more strongly associated with delusions of persecution than with the other psychotic symptoms.”

Those with distressing psychotic experiences tended to have more copy number variations (CNVs) associated with schizophrenia (OR, 2.04) and neurodevelopmental disorders (OR, 1.75). The team also found significant associations between distressing experiences and major depressive disorder, ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia.

“We found particular enrichment of these [polygenic risk scores] in distressing psychotic experiences and for delusions of persecution,” they noted. “ ... All schizophrenia-associated [copy number variations] are also associated with neurodevelopmental disorders such as intellectual disability and autism.”

The study’s strengths include its large sample size. Among its limitations, the researchers said, are the study’s retrospective measurement of psychotic experiences based on self-report from a questionnaire that was online. Gathering the data in that way raised the likelihood of possible error, they said.

Dr. Legge reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Legge SE et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 25. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2508.

The genetic links uncovered in this study offer an intriguing, but incomplete look at the risks of psychotic experiences and their complicated intertwinings with other mental disorders, wrote Albert R. Powers III, MD, PhD.

“Penetrance of the genes in question likely depends at least in part on environmental influences, some of which have been studied extensively,” he wrote. “Recently, some have proposed risk stratification by exposome – a composite score of relevant exposures that may increase risk for psychosis and is analogous to the polygenic risk score used [here].

“The combination of environmental and genetic composite scores may lead to improved insight into individualized pathways toward psychotic experiences, highlighting genetic vulnerabilities to specific stressors likely to lead to phenotypic expression. Ultimately, this will require a more sophisticated mapping between phenomenology and biology than currently exists.”

One approach would be to combine deep phenotyping and behavioral analyses in a framework that could link all relevant levels from symptoms to neurophysiology.

“One such framework is predictive processing theory, which is linked closely with the free energy principle and the Bayesian brain hypothesis and attempts to explain perceptual and cognitive phenomena as manifestations of a drive to maintain as accurate an internal model of one’s surroundings as possible by minimizing prediction errors. This relatively simple scheme makes specific – and, importantly, falsifiable – assessments of the mathematical signatures of neurotypical processes and the ways they might break down to produce specific psychiatric symptoms.”

Dr. Powers is an assistant professor at the department of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and serves as medical director of the PRIME Psychosis Research Clinic at Yale. His comments came in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Sep 25. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2391 ).

The genetic links uncovered in this study offer an intriguing, but incomplete look at the risks of psychotic experiences and their complicated intertwinings with other mental disorders, wrote Albert R. Powers III, MD, PhD.

“Penetrance of the genes in question likely depends at least in part on environmental influences, some of which have been studied extensively,” he wrote. “Recently, some have proposed risk stratification by exposome – a composite score of relevant exposures that may increase risk for psychosis and is analogous to the polygenic risk score used [here].