User login

‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.

18. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/. Published September 24, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2019.

19. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use--rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.

18. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/. Published September 24, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2019.

19. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use--rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.

18. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/. Published September 24, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2019.

19. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use--rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

DBS vs TMS for treatment-resistant depression: A comparison

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with major depressive disorder do not respond to pharmacotherapy.1 For patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD)—typically defined as an inadequate response to at least 1 antidepressant trial of adequate dose and duration—neurostimulation may be an effective treatment option.

Two forms of neurostimulation used to treat TRD are deep brain stimulation (DBS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). In DBS, electrodes are placed within the patient’s cranium and affixed to specific target locations. These electrodes are electrically stimulated at various frequencies. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive treatment in which a magnetic field is produced over a patient’s cranium, stimulating brain tissue via electromagnetic induction.

Media portraya

In this article, I compare DBS and TMS, and offer suggestions for educating patients about the potential adverse effects and therapeutic outcomes of each modality.

Deep brain stimulation

Deep brain stimulation is FDA-approved for treating Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, dystonia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).3 It has been used off-label for TRD, and some preliminary evidence suggests it is effective for this purpose. A review of 22 studies found that for patients with TRD, the rate of response to DBS (defined as >50% improvement on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score) ranges from 40% to 70%.1 Additional research, including larger, randomized, sham-controlled trials, is needed.

A consensus on the optimal target location for DBS has not yet been reached. Studies have had varying degrees of symptom improvement targeting the subgenual cingulate gyrus, posterior gyrus rectus, nucleus accumbens, ventral capsule/ventral striatum, inferior thalamic peduncle, and lateral habenula.1

A worsening of depressive symptoms and increased risk of suicide have been reported in—but are not exclusive to—DBS. Patients treated with DBS may still meet the criteria for treatment resistance.

Continue to: The lack of insurance coverage...

The lack of insurance coverage for DBS for treating depression is a deterrent to its use. Because DBS is not FDA-approved for treating depression, the costs (approximately $65,000) that are not covered by a facility or study will fall on the patient.4 Patients may abandon hope for a positive therapeutic outcome if they must struggle with the financial responsibility for procedures and follow-up.4

Serious potential adverse events of DBS include infections, skin erosions, and postoperative seizure.4 Patients who are treated with DBS should be educated about these adverse effects, and how they may affect outcomes.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is FDA-approved for treating depression, OCD, and migraine. Randomized, sham-controlled trials have found that TMS is effective for TRD.5 Studies have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy, with response rates ranging from 47% to 58%.6

The most commonly used target area for TMS for patients with depression is the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.7 Potential adverse effects are relatively few and benign. The most serious adverse effect of TMS is a risk for seizure, which is reported to occur at a frequency of <0.1%.7

Although it varies by practice and location, the cost for an acute course of TMS (20 to 30 sessions) may range from $6,000 to $12,000.8 Most insurance companies cover TMS treatment for depression.

Continue to: TMS

TMS: A more accessible option

Compared with DBS, TMS is a more affordable and accessible therapy for patients with TRD. Further studies are needed to learn more about the therapeutic potential of DBS for TRD, and to develop methods that help decrease the risk of adverse effects. In addition, insurance coverage needs to be expanded to DBS to avoid having patients be responsible for the full costs of this treatment. Until then, TMS should be a recommended therapy for patients with TRD. If TRD persists in patients treated with TMS, consider electroconvulsive therapy.

1. Morishita T, Fayad SM, Higuchi MA, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: systematic review of clinical outcomes. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-484.

2. Lawrence RE, Kaufmann CR, DeSilva RB, et al. Patients’ belief about deep brain stimulation for treatment resistant depression. AJOB Neuroscience, 2018;9(4):210-218.

3. Rossi PJ, Giordano J, Okun MS. The problem of funding off-label deep brain stimulation: bait-and-switch tactics and the need for policy reform. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(1):9-10.

4. Holtzheimer PE, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a multisite, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(11):839-849.

5. Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

6. Janicak PG, Sackett V, Kudrna K, et al. Advances in transcranial magnetic stimulation for managing major depressive disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):49-56.

7. Dobek CE, Blumberger DM, Downar J, et al. Risk of seizures in transcranial magnetic stimulation: a clinical review to inform consent process focused on bupropion. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2975-2987.

8. McClintock SM, Reti IM, Carpenter LL, et al; National Network of Depression Centers rTMS Task Group; American Psychiatric Association Council on Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. Consensus recommendations for the clinical application of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.16cs10905.

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with major depressive disorder do not respond to pharmacotherapy.1 For patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD)—typically defined as an inadequate response to at least 1 antidepressant trial of adequate dose and duration—neurostimulation may be an effective treatment option.

Two forms of neurostimulation used to treat TRD are deep brain stimulation (DBS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). In DBS, electrodes are placed within the patient’s cranium and affixed to specific target locations. These electrodes are electrically stimulated at various frequencies. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive treatment in which a magnetic field is produced over a patient’s cranium, stimulating brain tissue via electromagnetic induction.

Media portraya

In this article, I compare DBS and TMS, and offer suggestions for educating patients about the potential adverse effects and therapeutic outcomes of each modality.

Deep brain stimulation

Deep brain stimulation is FDA-approved for treating Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, dystonia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).3 It has been used off-label for TRD, and some preliminary evidence suggests it is effective for this purpose. A review of 22 studies found that for patients with TRD, the rate of response to DBS (defined as >50% improvement on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score) ranges from 40% to 70%.1 Additional research, including larger, randomized, sham-controlled trials, is needed.

A consensus on the optimal target location for DBS has not yet been reached. Studies have had varying degrees of symptom improvement targeting the subgenual cingulate gyrus, posterior gyrus rectus, nucleus accumbens, ventral capsule/ventral striatum, inferior thalamic peduncle, and lateral habenula.1

A worsening of depressive symptoms and increased risk of suicide have been reported in—but are not exclusive to—DBS. Patients treated with DBS may still meet the criteria for treatment resistance.

Continue to: The lack of insurance coverage...

The lack of insurance coverage for DBS for treating depression is a deterrent to its use. Because DBS is not FDA-approved for treating depression, the costs (approximately $65,000) that are not covered by a facility or study will fall on the patient.4 Patients may abandon hope for a positive therapeutic outcome if they must struggle with the financial responsibility for procedures and follow-up.4

Serious potential adverse events of DBS include infections, skin erosions, and postoperative seizure.4 Patients who are treated with DBS should be educated about these adverse effects, and how they may affect outcomes.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is FDA-approved for treating depression, OCD, and migraine. Randomized, sham-controlled trials have found that TMS is effective for TRD.5 Studies have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy, with response rates ranging from 47% to 58%.6

The most commonly used target area for TMS for patients with depression is the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.7 Potential adverse effects are relatively few and benign. The most serious adverse effect of TMS is a risk for seizure, which is reported to occur at a frequency of <0.1%.7

Although it varies by practice and location, the cost for an acute course of TMS (20 to 30 sessions) may range from $6,000 to $12,000.8 Most insurance companies cover TMS treatment for depression.

Continue to: TMS

TMS: A more accessible option

Compared with DBS, TMS is a more affordable and accessible therapy for patients with TRD. Further studies are needed to learn more about the therapeutic potential of DBS for TRD, and to develop methods that help decrease the risk of adverse effects. In addition, insurance coverage needs to be expanded to DBS to avoid having patients be responsible for the full costs of this treatment. Until then, TMS should be a recommended therapy for patients with TRD. If TRD persists in patients treated with TMS, consider electroconvulsive therapy.

Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with major depressive disorder do not respond to pharmacotherapy.1 For patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD)—typically defined as an inadequate response to at least 1 antidepressant trial of adequate dose and duration—neurostimulation may be an effective treatment option.

Two forms of neurostimulation used to treat TRD are deep brain stimulation (DBS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). In DBS, electrodes are placed within the patient’s cranium and affixed to specific target locations. These electrodes are electrically stimulated at various frequencies. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive treatment in which a magnetic field is produced over a patient’s cranium, stimulating brain tissue via electromagnetic induction.

Media portraya

In this article, I compare DBS and TMS, and offer suggestions for educating patients about the potential adverse effects and therapeutic outcomes of each modality.

Deep brain stimulation

Deep brain stimulation is FDA-approved for treating Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, dystonia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).3 It has been used off-label for TRD, and some preliminary evidence suggests it is effective for this purpose. A review of 22 studies found that for patients with TRD, the rate of response to DBS (defined as >50% improvement on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score) ranges from 40% to 70%.1 Additional research, including larger, randomized, sham-controlled trials, is needed.

A consensus on the optimal target location for DBS has not yet been reached. Studies have had varying degrees of symptom improvement targeting the subgenual cingulate gyrus, posterior gyrus rectus, nucleus accumbens, ventral capsule/ventral striatum, inferior thalamic peduncle, and lateral habenula.1

A worsening of depressive symptoms and increased risk of suicide have been reported in—but are not exclusive to—DBS. Patients treated with DBS may still meet the criteria for treatment resistance.

Continue to: The lack of insurance coverage...

The lack of insurance coverage for DBS for treating depression is a deterrent to its use. Because DBS is not FDA-approved for treating depression, the costs (approximately $65,000) that are not covered by a facility or study will fall on the patient.4 Patients may abandon hope for a positive therapeutic outcome if they must struggle with the financial responsibility for procedures and follow-up.4

Serious potential adverse events of DBS include infections, skin erosions, and postoperative seizure.4 Patients who are treated with DBS should be educated about these adverse effects, and how they may affect outcomes.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is FDA-approved for treating depression, OCD, and migraine. Randomized, sham-controlled trials have found that TMS is effective for TRD.5 Studies have demonstrated varying degrees of efficacy, with response rates ranging from 47% to 58%.6

The most commonly used target area for TMS for patients with depression is the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.7 Potential adverse effects are relatively few and benign. The most serious adverse effect of TMS is a risk for seizure, which is reported to occur at a frequency of <0.1%.7

Although it varies by practice and location, the cost for an acute course of TMS (20 to 30 sessions) may range from $6,000 to $12,000.8 Most insurance companies cover TMS treatment for depression.

Continue to: TMS

TMS: A more accessible option

Compared with DBS, TMS is a more affordable and accessible therapy for patients with TRD. Further studies are needed to learn more about the therapeutic potential of DBS for TRD, and to develop methods that help decrease the risk of adverse effects. In addition, insurance coverage needs to be expanded to DBS to avoid having patients be responsible for the full costs of this treatment. Until then, TMS should be a recommended therapy for patients with TRD. If TRD persists in patients treated with TMS, consider electroconvulsive therapy.

1. Morishita T, Fayad SM, Higuchi MA, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: systematic review of clinical outcomes. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-484.

2. Lawrence RE, Kaufmann CR, DeSilva RB, et al. Patients’ belief about deep brain stimulation for treatment resistant depression. AJOB Neuroscience, 2018;9(4):210-218.

3. Rossi PJ, Giordano J, Okun MS. The problem of funding off-label deep brain stimulation: bait-and-switch tactics and the need for policy reform. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(1):9-10.

4. Holtzheimer PE, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a multisite, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(11):839-849.

5. Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

6. Janicak PG, Sackett V, Kudrna K, et al. Advances in transcranial magnetic stimulation for managing major depressive disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):49-56.

7. Dobek CE, Blumberger DM, Downar J, et al. Risk of seizures in transcranial magnetic stimulation: a clinical review to inform consent process focused on bupropion. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2975-2987.

8. McClintock SM, Reti IM, Carpenter LL, et al; National Network of Depression Centers rTMS Task Group; American Psychiatric Association Council on Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. Consensus recommendations for the clinical application of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.16cs10905.

1. Morishita T, Fayad SM, Higuchi MA, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: systematic review of clinical outcomes. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(3):475-484.

2. Lawrence RE, Kaufmann CR, DeSilva RB, et al. Patients’ belief about deep brain stimulation for treatment resistant depression. AJOB Neuroscience, 2018;9(4):210-218.

3. Rossi PJ, Giordano J, Okun MS. The problem of funding off-label deep brain stimulation: bait-and-switch tactics and the need for policy reform. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(1):9-10.

4. Holtzheimer PE, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a multisite, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(11):839-849.

5. Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

6. Janicak PG, Sackett V, Kudrna K, et al. Advances in transcranial magnetic stimulation for managing major depressive disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(6):49-56.

7. Dobek CE, Blumberger DM, Downar J, et al. Risk of seizures in transcranial magnetic stimulation: a clinical review to inform consent process focused on bupropion. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2975-2987.

8. McClintock SM, Reti IM, Carpenter LL, et al; National Network of Depression Centers rTMS Task Group; American Psychiatric Association Council on Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. Consensus recommendations for the clinical application of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(1). doi: 10.4088/JCP.16cs10905.

Antidepressants for pediatric patients

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a significant pediatric health problem, with a lifetime prevalence as high as 20% by the end of adolescence.1-3 Major depressive disorder in adolescence is associated with significant morbidity, including poor social functioning, school difficulties, early pregnancy, and increased risk of physical illness and substance abuse.4-6 It is also linked with significant mortality, with increased risk for suicide, which is now the second leading cause of death in individuals age 10 to 24 years.1,7,8

As their name suggests, antidepressants comprise a group of medications that are used to treat MDD; they are also, however, first-line agents for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in adults. Anxiety disorders (including GAD and other anxiety diagnoses) and PTSD are also common in childhood and adolescence with a combined lifetime prevalence ranging from 15% to 30%.9,10 These disorders are also associated with increased risk of suicide.11 For all of these disorders, depending on the severity of presentation and the preference of the patient, treatments are often a combination of psychotherapy and psychopharmacology.

Clinicians face several challenges when considering antidepressants for pediatric patients. Pediatricians and psychiatrists need to understand whether these medications work in children and adolescents, and whether there are unique developmental safety and tolerability issues. The evidence base in child psychiatry is considerably smaller compared with that of adult psychiatry. From this more limited evidence base also came the controversial “black-box” warning regarding a risk of emergent suicidality when starting antidepressants that accompanies all antidepressants for pediatric, but not adult, patients. This warning has had major effects on clinical encounters with children experiencing depression, including altering clinician prescribing behavior.12

Do antidepressants work in children?

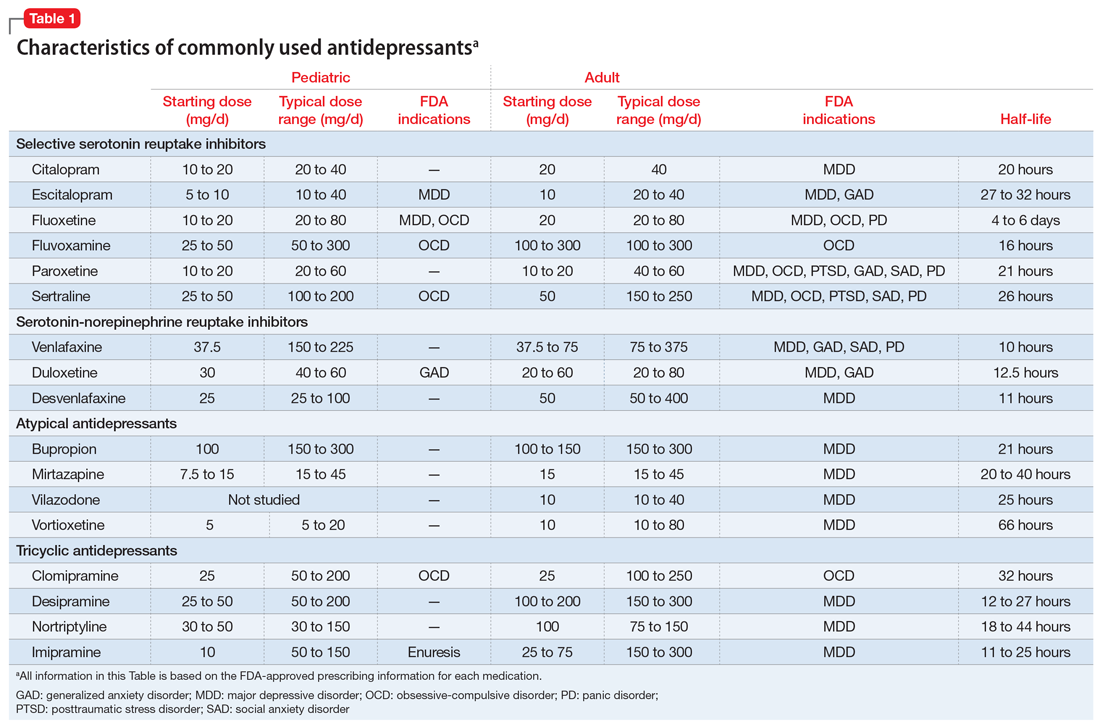

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly used class of antidepressants in both children and adults.13 While only a few SSRIs are FDA-approved for pediatric indications, the lack of FDA approval is typically related to a lack of sufficient testing in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for specific pediatric indications, rather than to demonstrable differences in efficacy between antidepressant agents. Since there is currently no data to suggest inferiority of one agent compared to another in children or adults,14,15 efficacy data will be discussed here as applied to the class of SSRIs, generalizing from RCTs conducted on individual drugs. Table 1 lists FDA indications and dosing information for individual antidepressants.

There is strong evidence that SSRIs are effective for treating pediatric anxiety disorders (eg, social anxiety disorder and GAD)16 and OCD,17 with numbers needed to treat (NNT) between 3 and 5. For both of these disorders, SSRIs combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have the highest likelihood of improving symptoms or achieving remission.17,18

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are also effective for treating pediatric MDD; however, the literature is more complex for this disorder compared to GAD and OCD as there are considerable differences in effect sizes between National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)–funded studies and industry-sponsored trials.13 The major NIMH-sponsored adolescent depression trial, TADS (Treatment for Adolescents and Depression Study), showed that SSRIs (fluoxetine in this case) were quite effective, with an NNT of 4 over the acute phase (12 weeks).19 Ultimately, approximately 80% of adolescents improved over 9 months. Many industry-sponsored trials for MDD in pediatric patients had large placebo response rates (approximately 60%), which resulted in smaller between-group differences, and estimates of an NNT closer to 12,13 which has muddied the waters in meta-analyses that include all trials.20 Improvement in depressive symptoms also appears to be bolstered by concomitant CBT in MDD,19 but not as robustly as in GAD and OCD. While the full benefit of SSRIs for depression may take as long as 8 weeks, a meta-analysis of depression studies of pediatric patients suggests that significant benefits from placebo are observed as early as 2 weeks, and that further treatment gains are minimal after 4 weeks.15 Thus, we recommend at least a 4- to 6-week trial at therapeutic dosing before deeming a medication a treatment failure.

Continue to: Posttraumatic stress disorder...

Posttraumatic stress disorder is a fourth disorder in which SSRIs are a first-line treatment in adults. The data for using SSRIs to treat pediatric patients with PTSD is scant, with only a few RCTs, and no large NIMH-funded trials. Randomized controlled trials have not demonstrated significant differences between SSRIs and placebo21,22 and thus the current first-line recommendation in pediatric PTSD remains trauma-focused therapy, with good evidence for trauma-focused CBT.23 Practically speaking, there can be considerable overlap of PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms in children,23 and children with a history of trauma who also have comorbid MDD may benefit from medication if their symptoms persist despite an adequate trial of psychotherapy.

Taken together, the current evidence suggests that SSRIs are often effective in pediatric GAD, OCD, and MDD, with low NNTs (ranging from 3 to 5 based on NIMH-funded trials) for all of these disorders; there is not yet sufficient evidence of efficacy in pediatric patients with PTSD.

Fluoxetine has been studied more intensively than other SSRIs (for example, it was the antidepressant used in the TADS trial), and thus has the largest evidence base. For this reason, fluoxetine is often considered the first of the first-line options. Additionally, fluoxetine has a longer half-life than other antidepressants, which may make it more effective in situations where patients are likely to miss doses, and results in a lower risk of withdrawal symptoms when stopped due to “self-tapering.”

SNRIs and atypical antidepressants. Other antidepressants commonly used in pediatric patients but with far less evidence of efficacy include serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and the atypical antidepressants bupropion and mirtazapine. The SNRI duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating GAD in children age 7 to 17, but there are no other pediatric indications for duloxetine, or for the other SNRIs.

In general, adverse effect profiles are worse for SNRIs compared to SSRIs, further limiting their utility. While there are no pediatric studies demonstrating SNRI efficacy for neuropathic pain, good data exists in adults.24 Thus, an SNRI could be a reasonable option if a pediatric patient has failed prior adequate SSRI trials and also has comorbid neuropathic pain.

Continue to: Neither bupropion nor mirtazapine...

Neither bupropion nor mirtazapine have undergone rigorous testing in pediatric patients, and therefore these agents should generally be considered only once other first-line treatments have failed. Bupropion has been evaluated for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)25 and for adolescent smoking cessation.26 However, the evidence is weak, and bupropion is not considered a first-line option for children and adolescents.

Tricyclic antidepressants. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are efficacious for treating several pediatric conditions; however, their significant side effect profile, their monitoring requirements, as well as their lethality in overdose has left them replaced by SSRIs in most cases. That said, they can be appropriate in refractory ADHD (desipramine27,28) and refractory OCD (clomipramine is FDA-approved for this indication29); they are considered a third-line treatment for enuresis.30

Why did my patient stop the medication?

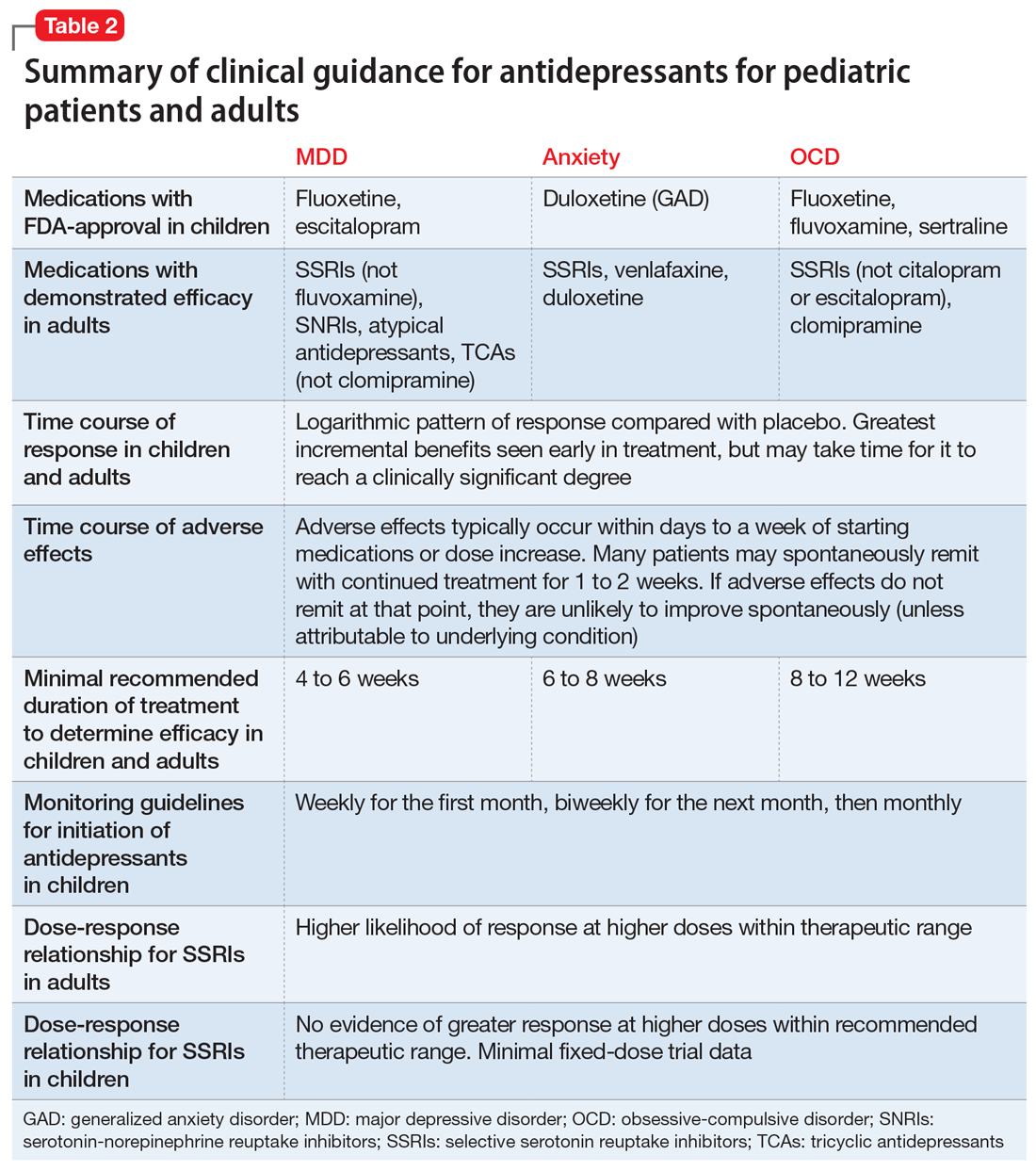

Common adverse effects. Although the greatest benefit of antidepressant medications compared with placebo is achieved relatively early on in treatment, it generally takes time for these benefits to accrue and become clinically apparent.15,31 By contrast, most adverse effects of antidepressants present and are at their most severe early in treatment. The combination of early adverse effects and delayed efficacy leads many patients, families, and clinicians to discontinue medications before they have an adequate chance to work. Thus, it is imperative to provide psychoeducation before starting a medication about the typical time-course of improvement and adverse effects (Table 2).

Adverse effects of SSRIs often appear or worsen transiently during initiation of a medication, during a dose increase,32 or, theoretically, with the addition of a medication that interferes with SSRI metabolism (eg, cimetidine inhibition of cytochrome P450 2D6).33 If families are prepared for this phenomenon and the therapeutic alliance is adequate, adverse effects can be tolerated to allow for a full medication trial. Common adverse effects of SSRIs include sleep problems (insomnia/sedation), gastrointestinal upset, sexual dysfunction, dry mouth, and hyperhidrosis. Although SSRIs differ somewhat in the frequency of these effects, as a class, they are more similar than different. Adequate psychoeducation is especially imperative in the treatment of OCD and anxiety disorders, where there is limited evidence of efficacy for any non-serotonergic antidepressants.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are not considered first-line medications because of the reduced evidence base compared to SSRIs and their enhanced adverse effect profiles. Because SNRIs partially share a mechanism of action with SSRIs, they also share portions of the adverse effects profile. However, SNRIs have the additional adverse effect of hypertension, which is related to their noradrenergic activity. Thus, it is reasonable to obtain a baseline blood pressure before initiating an SNRI, as well as periodically after initiation and during dose increases, particularly if the patient has other risk factors for hypertension.34

Continue to: Although TCAs have efficacy...

Although TCAs have efficacy in some pediatric disorders,27-29,35 their adverse effect profile limits their use. Tricyclic antidepressants are highly anticholinergic (causing dizziness secondary to orthostatic hypotension, dry mouth, and urinary retention) and antihistaminergic (causing sedation and weight gain). Additionally, TCAs lower the seizure threshold and have adverse cardiac effects relating to their anti-alpha-1 adrenergic activity, resulting in dose-dependent increases in the QTc and cardiac toxicity in overdose that could lead to arrhythmia and death. These medications have their place, but their use requires careful informed consent, clear treatment goals, and baseline and periodic cardiac monitoring (via electrocardiogram).

Serious adverse effects. Clinicians may be hesitant to prescribe antidepressants for pediatric patients because of the potential for more serious adverse effects, including severe behavioral activation syndromes, serotonin syndrome, and emergent suicidality. However, current FDA-approved antidepressants arguably have one of the most positive risk/benefit profiles of any orally-administered medication approved for pediatric patients. Having a strong understanding of the evidence is critical to evaluating when it is appropriate to prescribe an antidepressant, how to properly monitor the patient, and how to obtain accurate informed consent.

Pediatric behavioral activation syndrome. Many clinicians report that children receiving antidepressants experience a pediatric behavioral activation syndrome, which exists along a spectrum from mild activation, increased energy, insomnia, or irritability up through more severe presentations of agitation, hyperactivity, or possibly mania. A recent meta-analysis suggested a positive association between antidepressant use and activation events on the milder end of this spectrum in pediatric patients with non-OCD anxiety disorders,16 and it is thought that compared with adolescents, younger children are more susceptible to activation adverse effects.36 The likelihood of activation events has been associated with higher antidepressant plasma levels,37 suggesting that dose or individual differences in metabolism may play a role. At the severe end of the spectrum, the risk of induction of mania in pediatric patients with depression or anxiety is relatively rare (<2%) and not statistically different from placebo in RCTs of pediatric participants.38 Meta-analyses of larger randomized, placebo-controlled trials of adults do not support the idea that SSRIs and other second-generation antidepressants carry an increased risk of mania compared with placebo.39,40 Children or adolescents with bona fide bipolar disorder (ie, patients who have had observed mania that meets all DSM-5 criteria) should be treated with a mood-stabilizing agent or antipsychotic if prescribed an antidepressant.41 These clear-cut cases are, however, relatively rare, and more often clinicians are confronted with ambiguous cases that include a family history of bipolar disorder along with “softer” symptoms of irritability, intrusiveness, or aggression. In these children, SSRIs may be appropriate for depressive, OCD, or anxiety symptoms, and should be strongly considered before prescribing antipsychotics or mood stabilizers, as long as initiated with proper monitoring.

Serotonin syndrome is a life-threatening condition caused by excess synaptic serotonin. It is characterized by confusion, sweating, diarrhea, hypertension, hyperthermia, and tachycardia. At its most severe, serotonin syndrome can result in seizures, arrhythmias, and death. The risk of serotonin syndrome is very low when using an SSRI as monotherapy. Risk increases with polypharmacy, particularly unexamined polypharmacy when multiple serotonergic agents are inadvertently on board. Commonly used serotonergic agents include other antidepressants, migraine medications (eg, triptans), some pain medications, and the cough suppressant dextromethorphan.

The easiest way to mitigate the risk of serotonin syndrome is to use an interaction index computer program, which can help ensure that the interacting agents are not prescribed without first discussing the risks and benefits. It is important to teach adolescents that certain recreational drugs are highly serotonergic and can cause serious interactions with antidepressants. For example, recreational use of dextromethorphan or 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA; commonly known as “ecstasy”) has been associated with serotonin syndrome in adolescents taking antidepressant medications.42,43

Continue to: Suicidality

Suicidality. The black-box warning regarding a risk of emergent suicidality when starting antidepressant treatment in children is controversial.44 The prospect that a medication intended to ameliorate depression might instead risk increasing suicidal thinking is alarming to parents and clinicians alike. To appropriately weigh and discuss the risks and benefits with families, it is important to understand the data upon which the warning is based.

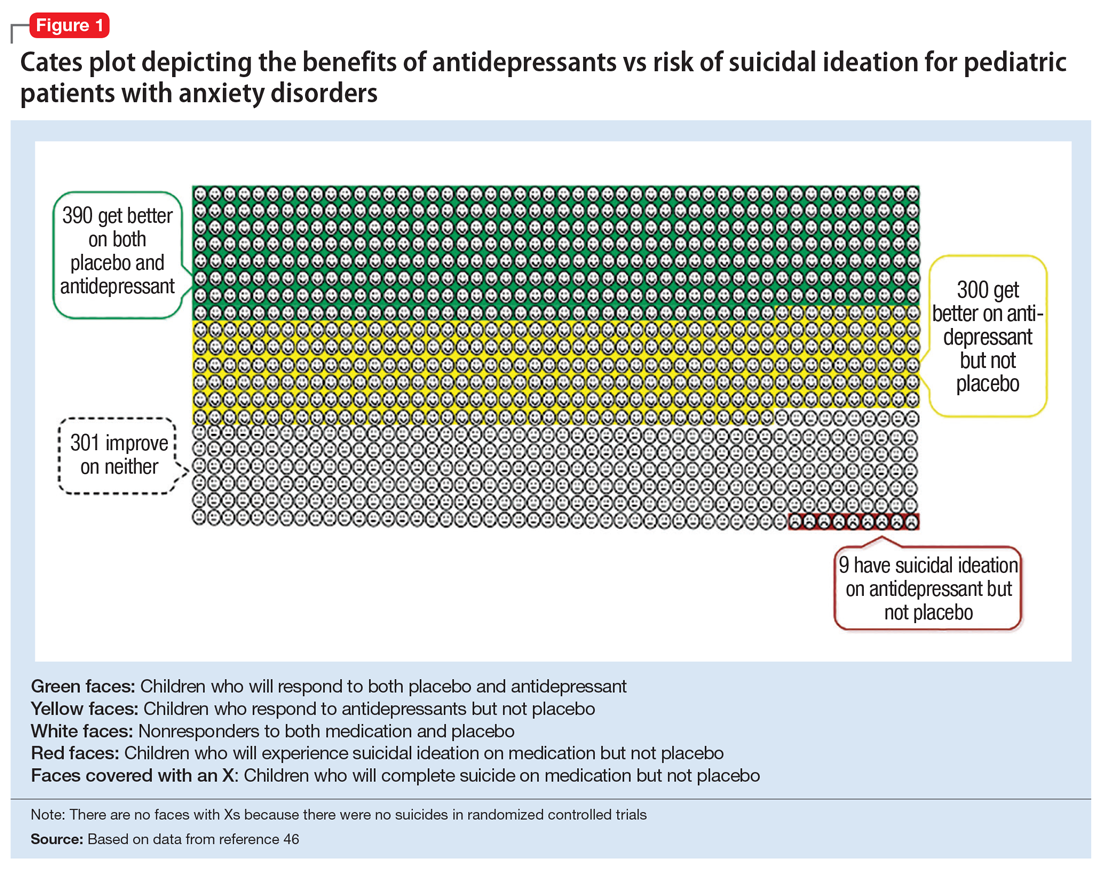

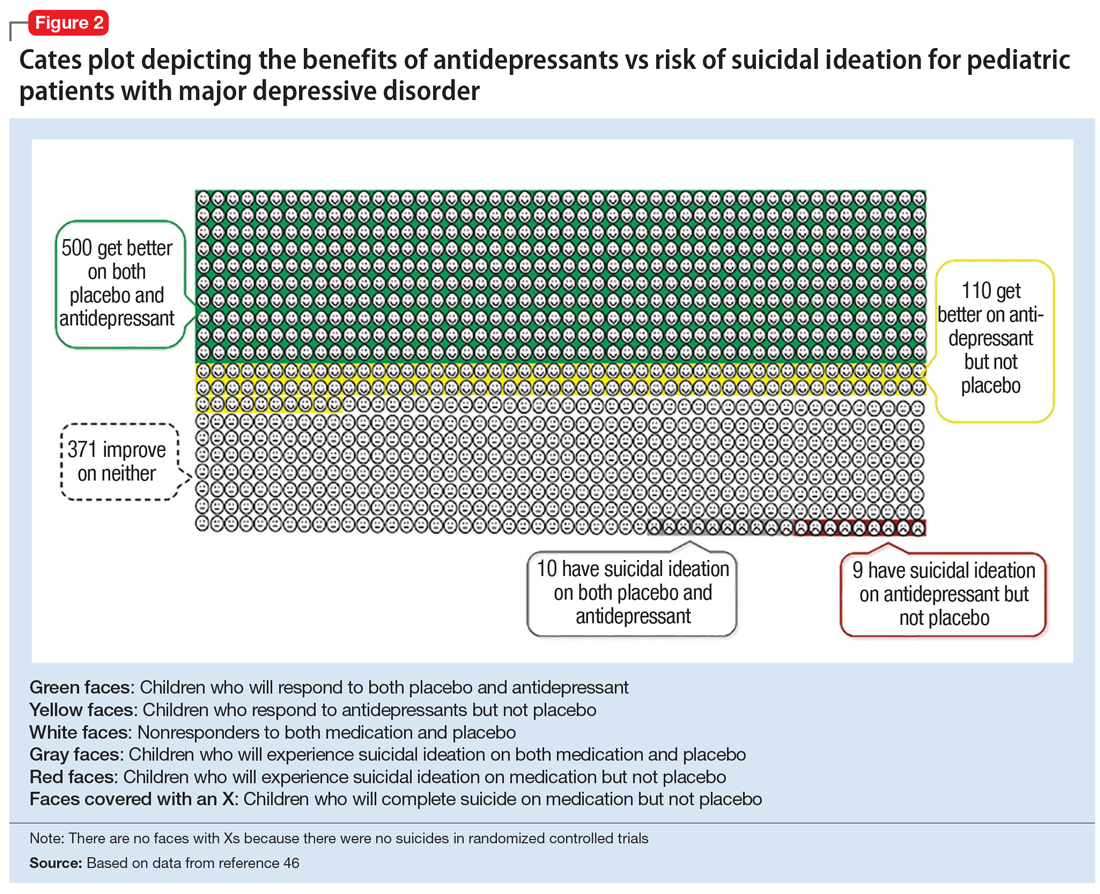

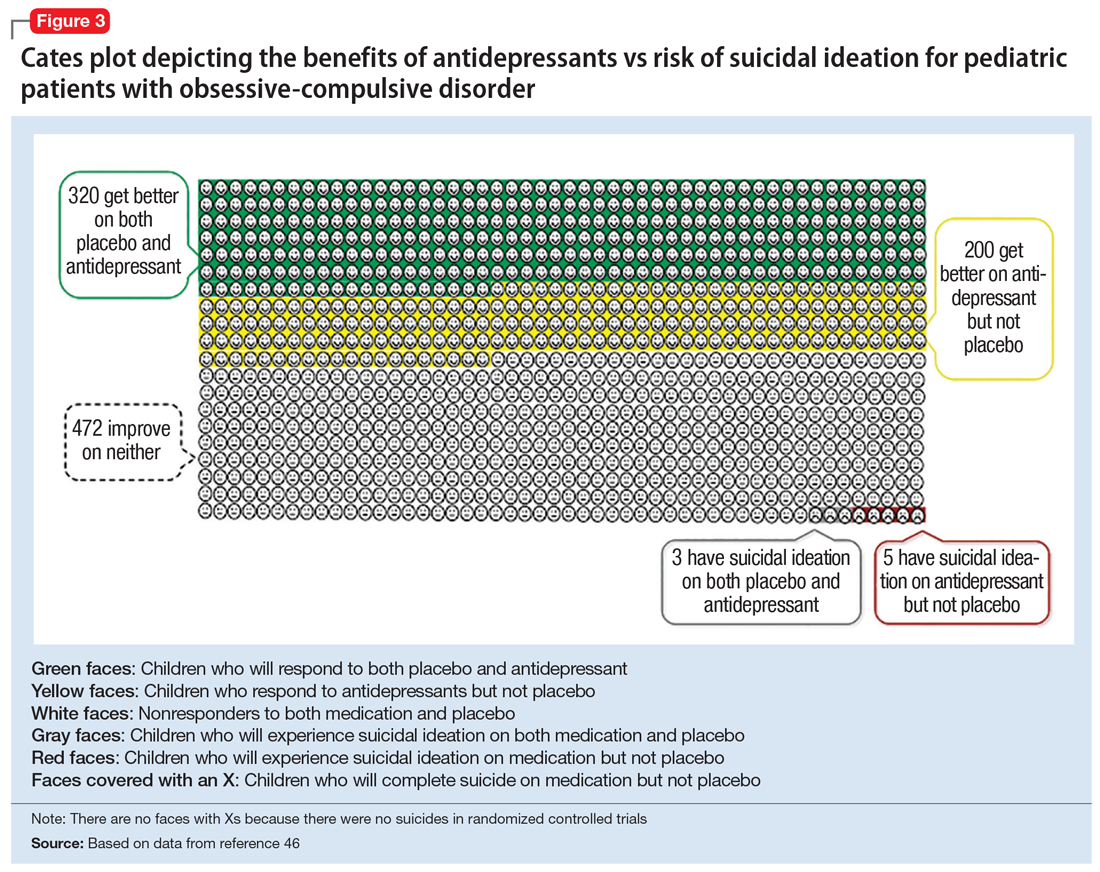

In 2004, the FDA commissioned a review of 23 antidepressant trials, both published and unpublished, pooling studies across multiple indications (MDD, OCD, anxiety, and ADHD) and multiple antidepressant classes. This meta-analysis, which included nearly 4,400 pediatric patients, found a small but statistically significant increase in spontaneously-reported suicidal thoughts or actions, with a risk difference of 1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1% to 2%).45 These data suggest that if one treats 100 pediatric patients, 1 to 2 of them may experience short-term increases in suicidal thinking or behavior.45 There were no differences in suicidal thinking when assessed systematically (ie, when all subjects reported symptoms of suicidal ideation on structured rating scales), and there were no completed suicides.45 A subsequent analysis that included 27 pediatric trials suggested an even lower, although still significant, risk difference (<1%), yielding a number needed to harm (NNH) of 143.46 Thus, with low NNT for efficacy (3 to 6) and relatively high NNH for emergent suicidal thoughts or behaviors (100 to 143), for many patients the benefits will outweigh the risks.

Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3 are Cates plots that depict the absolute benefits of antidepressants compared with the risk of suicidality for pediatric patients with MDD, OCD, and anxiety disorders. Recent meta-analyses have suggested that the increased risk of suicidality in antidepressant trials is specific to studies that included children and adolescents, and is not observed in adult studies. A meta-analysis of 70 trials involving 18,526 participants suggested that the odds ratio of suicidality in trials of children and adolescents was 2.39 (95% CI, 1.31 to 4.33) compared with 0.81 (95% CI, 0.51 to 1.28) in adults.47 Additionally, a network meta-analysis exclusively focusing on pediatric antidepressant trials in MDD reported significantly higher suicidality-related adverse events in venlafaxine trials compared with placebo, duloxetine, and several SSRIs (fluoxetine, paroxetine, and escitalopram).20 These data should be interpreted with caution as differences in suicidality detected between agents is quite possibly related to differences in the method of assessment between trials, as opposed to actual differences in risk between agents.

Epidemiologic data further support the use of antidepressants in pediatric patients, showing that antidepressant use is associated with decreased teen suicide attempts and completions,48 and the decline in prescriptions that occurred following the black-box warning was accompanied by a 14% increase in teen suicides.49 Multiple hypotheses have been proposed to explain the pediatric clinical trial findings. One idea is that potential adverse effects of activation, or the intended effects of restoring the motivation, energy, and social engagement that is often impaired in depression, increases the likelihood of thinking about suicide or acting on thoughts. Another theory is that reporting of suicidality may be increased, rather than increased de novo suicidality itself. Antidepressants are effective for treating pediatric anxiety disorders, including social anxiety disorder,16 which could result in more willingness to report. Also, the manner in which adverse effects are generally ascertained in trials might have led to increased spontaneous reporting. In many trials, investigators ask whether participants have any adverse effects in general, and inquire about specific adverse effects only if the family answers affirmatively. Thus, the increased rate of other adverse effects associated with antidepressants (sleep problems, gastrointestinal upset, dry mouth, etc.) might trigger a specific question regarding suicidal ideation, which the child or family then may be more likely to report. Alternatively, any type of psychiatric treatment could increase an individual’s propensity to report; in adolescent psychotherapy trials, non-medic

Continue to: How long should the antidepressant be continued?

How long should the antidepressant be continued?

Many patients are concerned about how long they may be taking medication, and whether they will be taking an antidepressant “forever.” A treatment course can be broken into an acute phase, wherein remission is achieved and maintained for 6 to 8 weeks. This is followed by a continuation phase, with the goal of relapse prevention, lasting 16 to 20 weeks. The length of the last phase—the maintenance phase—depends both on the child’s history, the underlying therapeutic indication, the adverse effect burden experienced, and the family’s preferences/values. In general, for a first depressive episode, after treating for 1 year, a trial of discontinuation can be attempted with close monitoring. For a second depressive episode, we recommend 2 years of remission on antidepressant therapy before attempting discontinuation. In patients who have had 3 depressive episodes, or have had episodes of high severity, we recommend continuing antidepressant treatment indefinitely. Although much less well studied, the risk of relapse following SSRI discontinuation appears much more significant in OCD, whereas anxiety disorders and MDD have a relatively comparable risk.52

In general, stopping an antidepressant should be done carefully and slowly.

What to do when first-line treatments fail

Adequate psychotherapy? To determine whether children are receiving adequate CBT, ask:

- if the child receives homework from psychotherapy

- if the parents are included in treatment

- if therapy has involved identifying thought patterns that may be contributing to the child’s illness, and

- if the therapist has ever exposed the child to a challenge likely to produce anxiety or distress in a supervised environment and has developed an exposure hierarchy (for conditions with primarily exposure-based therapies, such as OCD or anxiety disorders).

If a family is not receiving most of these elements in psychotherapy, this is a good indicator that they may not be receiving evidence-based CBT.

Continue to: Adequate pharmacotherapy?