User login

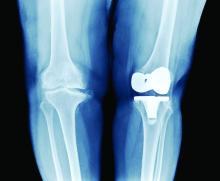

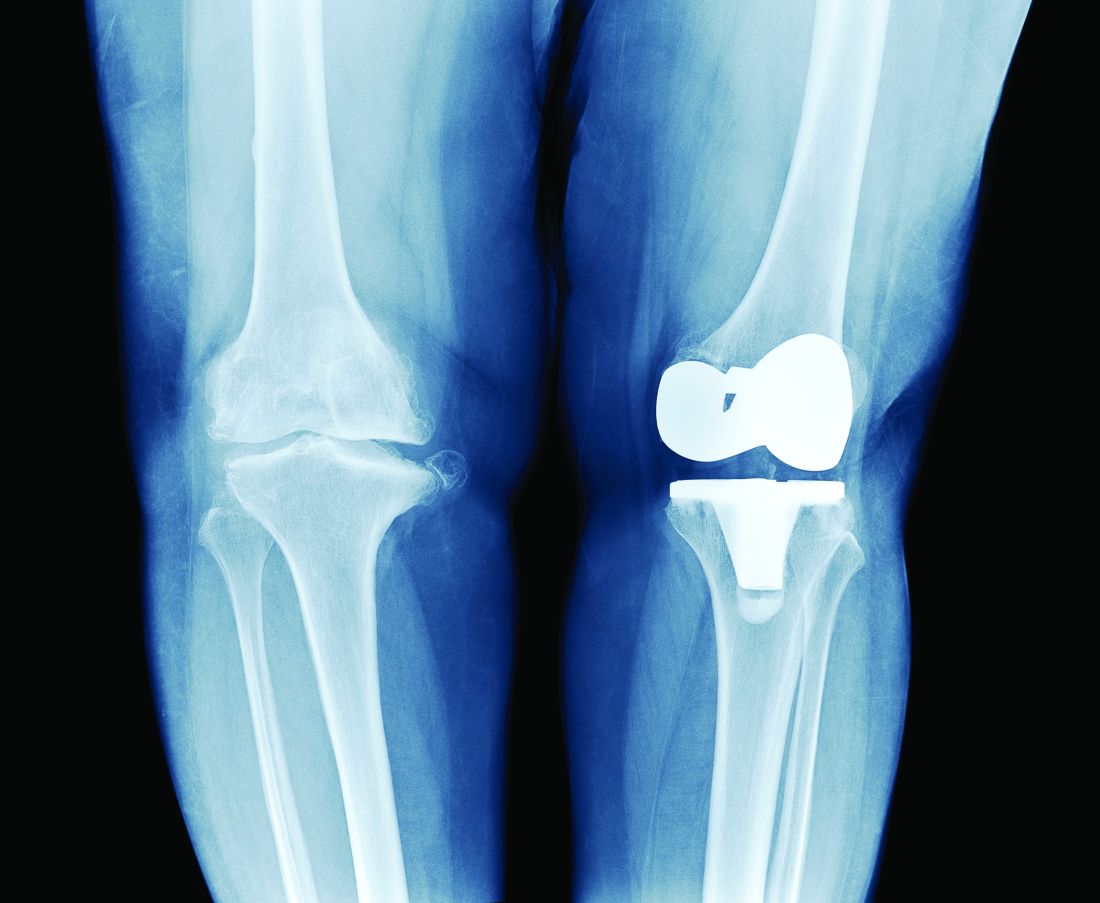

PT may lower risk of long-term opioid use after knee replacement

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adrenal vein sampling looms as choke point for aldosteronism assessment of hypertensives

At a time when new evidence strongly suggests that roughly a fifth of patents with hypertension have primary aldosteronism as the cause, other recent findings suggest that many of these possibly tens of millions of patients with aldosterone-driven high blood pressure may as a consequence need an expensive and not-widely-available diagnostic test – adrenal vein sampling – to determine whether they are candidates for a definitive surgical cure to their aldosteronism.

Some endocrinologists worry the worldwide infrastructure for running adrenal vein sampling (AVS) isn’t close to being in place to deliver on this looming need for patients with primary aldosteronism (PA), especially given the burgeoning numbers now being cited for PA prevalence.

“The system could be overwhelmed,” warned Robert M. Carey, MD, a cardiovascular endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “Right now, adrenal vein sampling [AVS] is the gold standard,” for distinguishing unilateral and bilateral excess aldosterone secretion, “but not every radiologist can do AVS. Until we find a surrogate biomarker that can distinguish unilateral and bilateral PA” many patients will need AVS, Dr. Carey said in an interview.

“AVS is important for accurate lateralization of aldosterone excess in patients, but it may not be feasible for all patients with PA to undergo AVS. If the prevalence of PA truly is on the order of 15% [of all patients with hypertension] then health systems would be stretched to offer all of them AVS, which is technically challenging and requires dedicated training and is therefore limited to expert centers,” commented Jun Yang, MBBS, a cardiovascular endocrinologist at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research and a hypertension researcher at Monash University, both in Melbourne. “At Monash, our interventional radiologists have increased their [AVS] success rate from 40% to more than 90% during the past 10 years, and our waiting list for patients scheduled for AVS is now 3-4 months long,” Dr. Yang said in an interview.

Finding a unilateral adrenal nodule as the cause of PA means that surgical removal is an option, a step that often fully resolves the PA and normalizes blood pressure. Patients with a bilateral source of the aldosterone are not candidates for surgical cure and must be managed with medical treatment, usually a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist such as spironolactone that can neutralize or at least reduce the impact of hyperaldosteronism.

AVS finds unilateral adenomas when imaging can’t

The evidence that raised concerns about the reliability of imaging as an easier and noninvasive means to identify hypertensive patients with PA and a unilateral adrenal nodule that makes them candidates for surgical removal to resolve their PA and hypertension came out in May 2020 in a review of 174 PA patients who underwent AVS at a single center in Calgary, Alta., during 2006-2018.

The review included 366 patients with PA referred to the University of Calgary for assessment, of whom 179 had no adrenal nodule visible with either CT or MRI imaging, with 174 of these patients also undergoing successful AVS. The procedure revealed 70 patients (40%) had unilateral aldosterone secretion (Can J Cardiol. 2020 May 16. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.05.013).

In an editorial about this report that appeared a few weeks later, Ross D. Feldman, MD, a hypertension-management researcher and professor of medicine at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Man., said the finding was “amazing,” and “confirms that lateralization of aldosterone secretion in a patient with PA but without an identifiable mass on that side is not a zebra,” but instead a presentation that “occurs in almost half of patients with PA and no discernible adenoma on the side that lateralizes.” (Can J. Cardiol. 2020 Jul 3. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.06.022).

Although this was just one center’s experience, the authors are not alone in making this finding, although prior reports seem to have been largely forgotten or ignored until now.

“The discordance between AVS and adrenal imaging has been documented by numerous groups, and in our own experience [in Melbourne] around 40% of patients with unilateral aldosterone excess do not have a distinct unilateral adenoma on CT,” said Dr. Yang.

“Here’s the problem,” summed up Dr. Feldman in an interview. “Nearly half of patients with hyperaldosteronism don’t localize based on a CT or MRI, so you have to do AVS, but AVS is not generally available; it’s only at tertiary centers; and you have to do a lot of them,” to do them well. “It’s a half-day procedure, and you have to hit the correct adrenal vein.”

AVS for millions?

Compounding the challenge is the other bit of bombshell news recently dropped on the endocrinology and hypertension communities: PA may be much more prevalent that previously suspected, occurring in roughly 20% of patients with hypertension, according to study results that also came out in 2020 (Ann Int Med. 2020 Jul 7;173[1]:10-20).

The upshot, according to Dr. Feldman and others, is that researchers will need to find reliable criteria besides imaging for identifying PA patients with an increased likelihood of having a lateralized source for their excess aldosterone production. That’s “the only hope,” said Dr. Feldman, “so we won’t have to do AVS on 20 million Americans.”

Unfortunately, the path toward a successful screen to winnow down candidates for AVS has been long and not especially fruitful, with efforts dating back at least 50 years, and with one of the most recent efforts at stratifying PA patients by certain laboratory measures getting dismissed as producing a benefit that “might not be substantial,” wrote Michael Stowasser, MBBS, in a published commentary (J Hypertension. 2020 Jul;38[7]:1259-61).

In contrast to Dr. Feldman, Dr. Stowasser was more optimistic about the prospects for avoiding an immediate crisis in AVS assessment of PA patients, mostly because so few patients with PA are now identified by clinicians. Given the poor record clinicians have historically rung up diagnosing PA, “it would seem unlikely that we are going to be flooded with AVS requests any time soon,” he wrote. There is also reason to hope that increased demand for AVS will help broaden availability, and innovative testing methods promise to speed up the procedure, said Dr. Stowasser, a professor of medicine at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia and director of the Endocrine Hypertension Research Centre at Greenslopes and Princess Alexandra Hospitals in Brisbane, in an interview.

But regardless of whether AVS testing becomes more available or streamlined, recent events suggest there will be little way to avoid eventually having to run millions of these diagnostic procedures.

Patients with PA “who decide they will not want surgery do not need AVS. For all other patients with PA, you need AVS. The medical system will just have to respond,” Dr. Carey concluded.

Dr. Carey, Dr. Yang, Dr. Feldman, and Dr. Stowasser had no relevant disclosures.

At a time when new evidence strongly suggests that roughly a fifth of patents with hypertension have primary aldosteronism as the cause, other recent findings suggest that many of these possibly tens of millions of patients with aldosterone-driven high blood pressure may as a consequence need an expensive and not-widely-available diagnostic test – adrenal vein sampling – to determine whether they are candidates for a definitive surgical cure to their aldosteronism.

Some endocrinologists worry the worldwide infrastructure for running adrenal vein sampling (AVS) isn’t close to being in place to deliver on this looming need for patients with primary aldosteronism (PA), especially given the burgeoning numbers now being cited for PA prevalence.

“The system could be overwhelmed,” warned Robert M. Carey, MD, a cardiovascular endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “Right now, adrenal vein sampling [AVS] is the gold standard,” for distinguishing unilateral and bilateral excess aldosterone secretion, “but not every radiologist can do AVS. Until we find a surrogate biomarker that can distinguish unilateral and bilateral PA” many patients will need AVS, Dr. Carey said in an interview.

“AVS is important for accurate lateralization of aldosterone excess in patients, but it may not be feasible for all patients with PA to undergo AVS. If the prevalence of PA truly is on the order of 15% [of all patients with hypertension] then health systems would be stretched to offer all of them AVS, which is technically challenging and requires dedicated training and is therefore limited to expert centers,” commented Jun Yang, MBBS, a cardiovascular endocrinologist at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research and a hypertension researcher at Monash University, both in Melbourne. “At Monash, our interventional radiologists have increased their [AVS] success rate from 40% to more than 90% during the past 10 years, and our waiting list for patients scheduled for AVS is now 3-4 months long,” Dr. Yang said in an interview.

Finding a unilateral adrenal nodule as the cause of PA means that surgical removal is an option, a step that often fully resolves the PA and normalizes blood pressure. Patients with a bilateral source of the aldosterone are not candidates for surgical cure and must be managed with medical treatment, usually a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist such as spironolactone that can neutralize or at least reduce the impact of hyperaldosteronism.

AVS finds unilateral adenomas when imaging can’t

The evidence that raised concerns about the reliability of imaging as an easier and noninvasive means to identify hypertensive patients with PA and a unilateral adrenal nodule that makes them candidates for surgical removal to resolve their PA and hypertension came out in May 2020 in a review of 174 PA patients who underwent AVS at a single center in Calgary, Alta., during 2006-2018.

The review included 366 patients with PA referred to the University of Calgary for assessment, of whom 179 had no adrenal nodule visible with either CT or MRI imaging, with 174 of these patients also undergoing successful AVS. The procedure revealed 70 patients (40%) had unilateral aldosterone secretion (Can J Cardiol. 2020 May 16. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.05.013).

In an editorial about this report that appeared a few weeks later, Ross D. Feldman, MD, a hypertension-management researcher and professor of medicine at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Man., said the finding was “amazing,” and “confirms that lateralization of aldosterone secretion in a patient with PA but without an identifiable mass on that side is not a zebra,” but instead a presentation that “occurs in almost half of patients with PA and no discernible adenoma on the side that lateralizes.” (Can J. Cardiol. 2020 Jul 3. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.06.022).

Although this was just one center’s experience, the authors are not alone in making this finding, although prior reports seem to have been largely forgotten or ignored until now.

“The discordance between AVS and adrenal imaging has been documented by numerous groups, and in our own experience [in Melbourne] around 40% of patients with unilateral aldosterone excess do not have a distinct unilateral adenoma on CT,” said Dr. Yang.

“Here’s the problem,” summed up Dr. Feldman in an interview. “Nearly half of patients with hyperaldosteronism don’t localize based on a CT or MRI, so you have to do AVS, but AVS is not generally available; it’s only at tertiary centers; and you have to do a lot of them,” to do them well. “It’s a half-day procedure, and you have to hit the correct adrenal vein.”

AVS for millions?

Compounding the challenge is the other bit of bombshell news recently dropped on the endocrinology and hypertension communities: PA may be much more prevalent that previously suspected, occurring in roughly 20% of patients with hypertension, according to study results that also came out in 2020 (Ann Int Med. 2020 Jul 7;173[1]:10-20).

The upshot, according to Dr. Feldman and others, is that researchers will need to find reliable criteria besides imaging for identifying PA patients with an increased likelihood of having a lateralized source for their excess aldosterone production. That’s “the only hope,” said Dr. Feldman, “so we won’t have to do AVS on 20 million Americans.”

Unfortunately, the path toward a successful screen to winnow down candidates for AVS has been long and not especially fruitful, with efforts dating back at least 50 years, and with one of the most recent efforts at stratifying PA patients by certain laboratory measures getting dismissed as producing a benefit that “might not be substantial,” wrote Michael Stowasser, MBBS, in a published commentary (J Hypertension. 2020 Jul;38[7]:1259-61).

In contrast to Dr. Feldman, Dr. Stowasser was more optimistic about the prospects for avoiding an immediate crisis in AVS assessment of PA patients, mostly because so few patients with PA are now identified by clinicians. Given the poor record clinicians have historically rung up diagnosing PA, “it would seem unlikely that we are going to be flooded with AVS requests any time soon,” he wrote. There is also reason to hope that increased demand for AVS will help broaden availability, and innovative testing methods promise to speed up the procedure, said Dr. Stowasser, a professor of medicine at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia and director of the Endocrine Hypertension Research Centre at Greenslopes and Princess Alexandra Hospitals in Brisbane, in an interview.

But regardless of whether AVS testing becomes more available or streamlined, recent events suggest there will be little way to avoid eventually having to run millions of these diagnostic procedures.

Patients with PA “who decide they will not want surgery do not need AVS. For all other patients with PA, you need AVS. The medical system will just have to respond,” Dr. Carey concluded.

Dr. Carey, Dr. Yang, Dr. Feldman, and Dr. Stowasser had no relevant disclosures.

At a time when new evidence strongly suggests that roughly a fifth of patents with hypertension have primary aldosteronism as the cause, other recent findings suggest that many of these possibly tens of millions of patients with aldosterone-driven high blood pressure may as a consequence need an expensive and not-widely-available diagnostic test – adrenal vein sampling – to determine whether they are candidates for a definitive surgical cure to their aldosteronism.

Some endocrinologists worry the worldwide infrastructure for running adrenal vein sampling (AVS) isn’t close to being in place to deliver on this looming need for patients with primary aldosteronism (PA), especially given the burgeoning numbers now being cited for PA prevalence.

“The system could be overwhelmed,” warned Robert M. Carey, MD, a cardiovascular endocrinologist and professor of medicine at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “Right now, adrenal vein sampling [AVS] is the gold standard,” for distinguishing unilateral and bilateral excess aldosterone secretion, “but not every radiologist can do AVS. Until we find a surrogate biomarker that can distinguish unilateral and bilateral PA” many patients will need AVS, Dr. Carey said in an interview.

“AVS is important for accurate lateralization of aldosterone excess in patients, but it may not be feasible for all patients with PA to undergo AVS. If the prevalence of PA truly is on the order of 15% [of all patients with hypertension] then health systems would be stretched to offer all of them AVS, which is technically challenging and requires dedicated training and is therefore limited to expert centers,” commented Jun Yang, MBBS, a cardiovascular endocrinologist at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research and a hypertension researcher at Monash University, both in Melbourne. “At Monash, our interventional radiologists have increased their [AVS] success rate from 40% to more than 90% during the past 10 years, and our waiting list for patients scheduled for AVS is now 3-4 months long,” Dr. Yang said in an interview.

Finding a unilateral adrenal nodule as the cause of PA means that surgical removal is an option, a step that often fully resolves the PA and normalizes blood pressure. Patients with a bilateral source of the aldosterone are not candidates for surgical cure and must be managed with medical treatment, usually a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist such as spironolactone that can neutralize or at least reduce the impact of hyperaldosteronism.

AVS finds unilateral adenomas when imaging can’t

The evidence that raised concerns about the reliability of imaging as an easier and noninvasive means to identify hypertensive patients with PA and a unilateral adrenal nodule that makes them candidates for surgical removal to resolve their PA and hypertension came out in May 2020 in a review of 174 PA patients who underwent AVS at a single center in Calgary, Alta., during 2006-2018.

The review included 366 patients with PA referred to the University of Calgary for assessment, of whom 179 had no adrenal nodule visible with either CT or MRI imaging, with 174 of these patients also undergoing successful AVS. The procedure revealed 70 patients (40%) had unilateral aldosterone secretion (Can J Cardiol. 2020 May 16. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.05.013).

In an editorial about this report that appeared a few weeks later, Ross D. Feldman, MD, a hypertension-management researcher and professor of medicine at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Man., said the finding was “amazing,” and “confirms that lateralization of aldosterone secretion in a patient with PA but without an identifiable mass on that side is not a zebra,” but instead a presentation that “occurs in almost half of patients with PA and no discernible adenoma on the side that lateralizes.” (Can J. Cardiol. 2020 Jul 3. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.06.022).

Although this was just one center’s experience, the authors are not alone in making this finding, although prior reports seem to have been largely forgotten or ignored until now.

“The discordance between AVS and adrenal imaging has been documented by numerous groups, and in our own experience [in Melbourne] around 40% of patients with unilateral aldosterone excess do not have a distinct unilateral adenoma on CT,” said Dr. Yang.

“Here’s the problem,” summed up Dr. Feldman in an interview. “Nearly half of patients with hyperaldosteronism don’t localize based on a CT or MRI, so you have to do AVS, but AVS is not generally available; it’s only at tertiary centers; and you have to do a lot of them,” to do them well. “It’s a half-day procedure, and you have to hit the correct adrenal vein.”

AVS for millions?

Compounding the challenge is the other bit of bombshell news recently dropped on the endocrinology and hypertension communities: PA may be much more prevalent that previously suspected, occurring in roughly 20% of patients with hypertension, according to study results that also came out in 2020 (Ann Int Med. 2020 Jul 7;173[1]:10-20).

The upshot, according to Dr. Feldman and others, is that researchers will need to find reliable criteria besides imaging for identifying PA patients with an increased likelihood of having a lateralized source for their excess aldosterone production. That’s “the only hope,” said Dr. Feldman, “so we won’t have to do AVS on 20 million Americans.”

Unfortunately, the path toward a successful screen to winnow down candidates for AVS has been long and not especially fruitful, with efforts dating back at least 50 years, and with one of the most recent efforts at stratifying PA patients by certain laboratory measures getting dismissed as producing a benefit that “might not be substantial,” wrote Michael Stowasser, MBBS, in a published commentary (J Hypertension. 2020 Jul;38[7]:1259-61).

In contrast to Dr. Feldman, Dr. Stowasser was more optimistic about the prospects for avoiding an immediate crisis in AVS assessment of PA patients, mostly because so few patients with PA are now identified by clinicians. Given the poor record clinicians have historically rung up diagnosing PA, “it would seem unlikely that we are going to be flooded with AVS requests any time soon,” he wrote. There is also reason to hope that increased demand for AVS will help broaden availability, and innovative testing methods promise to speed up the procedure, said Dr. Stowasser, a professor of medicine at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia and director of the Endocrine Hypertension Research Centre at Greenslopes and Princess Alexandra Hospitals in Brisbane, in an interview.

But regardless of whether AVS testing becomes more available or streamlined, recent events suggest there will be little way to avoid eventually having to run millions of these diagnostic procedures.

Patients with PA “who decide they will not want surgery do not need AVS. For all other patients with PA, you need AVS. The medical system will just have to respond,” Dr. Carey concluded.

Dr. Carey, Dr. Yang, Dr. Feldman, and Dr. Stowasser had no relevant disclosures.

Antibiotics or appendectomy? Both good options

Patients given antibiotics for appendicitis fared no worse in quality of life, at least in the short term, than did patients whose appendix was removed, according to a large, randomized, nonblinded, noninferiority study published online Oct. 5 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

One expert says the body of data, including this trial, indicates that the best appendicitis treatment now comes down to individual patients and choice.

David Flum, MD, director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Center at the University of Washington in Seattle, and colleagues conducted the Comparison of Outcomes of Antibiotic Drugs and Appendectomy (CODA) trial, which compared a 10-day course of antibiotics with appendectomy for patients with appendicitis at 25 US centers.

Although some may interpret the study as praising the potential role of antibiotics, the author of an accompanying editorial warns against rushing to antibiotics, even during a pandemic when hospital resources may be strained.

In the study of 1552 adults (414 with an appendicolith), 776 were randomly assigned to the antibiotics group and 776 to appendectomy (96% of whom underwent a laparoscopic procedure).

After 30 days, antibiotics were found to be noninferior to appendectomy, the standard of treatment for 120 years, as determined on the basis of 30-day scores for the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire (mean difference, 0.01 points; 95% CI, −0.001 to 0.03).

EQ-5D at 30 days was chosen as the primary endpoint because it has been validated as an overall measure of health after appendicitis treatment and the 30-day time frame mimics the typical recovery period for appendectomy, Flum and colleagues explain.

Some results favored appendectomy

However, editorialist Danny Jacobs, MD, MPH, president of Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, points out that about a third (29%) of the patients in the antibiotics group had undergone appendectomy by 90 days.

Appendicolith, a well-established potential complication, he acknowledges, was the main driver of the need for surgery (41% with that complication needed appendectomy), but it was not the sole reason.

Complications were more common in the antibiotics group than in the appendectomy group (8.1 vs 3.5 per 100 participants; rate ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.30 – 3.98). The rate of serious adverse events was 4.0 per 100 participants in the antibiotics group and 3.0 per 100 participants in the appendectomy group (rate ratio, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.67 – 2.50). Additionally, the number of emergency department visits was nearly three times higher in the antibiotics group, and more time was spent in the hospital by that group, Jacobs points out.

He notes that the article mentions circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic may figure into consideration when weighing antibiotics against appendectomy. But he warns that there also may be a danger of treatment bias in vulnerable populations and that COVID-19 has highlighted disparities in care overall.

“It will be important to ensure that some people, in particular vulnerable populations, are not offered antibiotic therapy preferentially or without adequate education regarding the longer-term implications,” Jacobs writes.

Flum told Medscape Medical News he agrees with Jacobs that the potential for bias is important.

“We should all be worried that new healthcare options won’t be equally applied,” he said.

But he and his coauthors offer an alternative view of the results of the study.

“In the antibiotics group,” they write, “more than 7 in 10 participants avoided surgery, many were treated on an outpatient basis, and participants and caregivers missed less time at work than with appendectomy.”

Flum said, “[T]hat’s going to be attractive to some patients. Not all, but some.”

Douglas Smink, MD, MPH, chief of surgery at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital in Boston, told Medscape Medical News that he sees this study as an argument for surgery remaining the go-to option for appendicitis, unless there is a safety reason for not performing the surgery.

Patients come in and want their appendix out immediately, he said, and surgery offers a quick option with short length of stay and few complications.

Additionally, he said, if patients are told that, with antibiotics, “there’s a 1 in 3 chance you’re going to need [an appendectomy] in the next 3 months, I think most people would say, ‘Just take it out then,’ ” he said.

Can research decide which is best?

The controversy has been well studied. But with no clear answer in any of the studies about whether appendectomy or use of antibiotics is better, should the current study put the research to rest?

Flum told Medscape Medical News that this study, which is three times the size of the next-largest study, makes clear “there are choices.”

Previous trials in Europe “did not move the needle” on the issue, he said, “in part because they didn’t include the patients who typically get appendectomies.”

He said their team tried to build on those studies and include “typical patients in typical hospitals with typical appendicitis” and found that both surgery and antibiotics are safe and have advantages and disadvantages, depending on the patient.

Smink says one thing that has been definitively answered with this trial is that patients with appendicolith are “more likely to fail with antibiotics.”

Previous trials have excluded patients with appendicolith, and this one did not.

“That’s something we’ve not really known for sure but we’ve assumed,” he said.

But now, Smink says, he thinks the research on the topic has gone about as far as it can go.

He notes that none of the trials has shown antibiotics to be better than appendectomy. “I have a hard time believing we are going to find anything different if we did another study like this. This is a really well-done one,” he said.

“If the best you can do is show noninferiority, which is where we are with these studies on appendicitis, you’re always going to have both options, which is great for patients and doctors,” he said.

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The original article lists the authors’ relevant financial relationships. Jacobs and Smink reported no such relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients given antibiotics for appendicitis fared no worse in quality of life, at least in the short term, than did patients whose appendix was removed, according to a large, randomized, nonblinded, noninferiority study published online Oct. 5 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

One expert says the body of data, including this trial, indicates that the best appendicitis treatment now comes down to individual patients and choice.

David Flum, MD, director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Center at the University of Washington in Seattle, and colleagues conducted the Comparison of Outcomes of Antibiotic Drugs and Appendectomy (CODA) trial, which compared a 10-day course of antibiotics with appendectomy for patients with appendicitis at 25 US centers.

Although some may interpret the study as praising the potential role of antibiotics, the author of an accompanying editorial warns against rushing to antibiotics, even during a pandemic when hospital resources may be strained.

In the study of 1552 adults (414 with an appendicolith), 776 were randomly assigned to the antibiotics group and 776 to appendectomy (96% of whom underwent a laparoscopic procedure).

After 30 days, antibiotics were found to be noninferior to appendectomy, the standard of treatment for 120 years, as determined on the basis of 30-day scores for the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire (mean difference, 0.01 points; 95% CI, −0.001 to 0.03).

EQ-5D at 30 days was chosen as the primary endpoint because it has been validated as an overall measure of health after appendicitis treatment and the 30-day time frame mimics the typical recovery period for appendectomy, Flum and colleagues explain.

Some results favored appendectomy

However, editorialist Danny Jacobs, MD, MPH, president of Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, points out that about a third (29%) of the patients in the antibiotics group had undergone appendectomy by 90 days.

Appendicolith, a well-established potential complication, he acknowledges, was the main driver of the need for surgery (41% with that complication needed appendectomy), but it was not the sole reason.

Complications were more common in the antibiotics group than in the appendectomy group (8.1 vs 3.5 per 100 participants; rate ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.30 – 3.98). The rate of serious adverse events was 4.0 per 100 participants in the antibiotics group and 3.0 per 100 participants in the appendectomy group (rate ratio, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.67 – 2.50). Additionally, the number of emergency department visits was nearly three times higher in the antibiotics group, and more time was spent in the hospital by that group, Jacobs points out.

He notes that the article mentions circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic may figure into consideration when weighing antibiotics against appendectomy. But he warns that there also may be a danger of treatment bias in vulnerable populations and that COVID-19 has highlighted disparities in care overall.

“It will be important to ensure that some people, in particular vulnerable populations, are not offered antibiotic therapy preferentially or without adequate education regarding the longer-term implications,” Jacobs writes.

Flum told Medscape Medical News he agrees with Jacobs that the potential for bias is important.

“We should all be worried that new healthcare options won’t be equally applied,” he said.

But he and his coauthors offer an alternative view of the results of the study.

“In the antibiotics group,” they write, “more than 7 in 10 participants avoided surgery, many were treated on an outpatient basis, and participants and caregivers missed less time at work than with appendectomy.”

Flum said, “[T]hat’s going to be attractive to some patients. Not all, but some.”

Douglas Smink, MD, MPH, chief of surgery at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital in Boston, told Medscape Medical News that he sees this study as an argument for surgery remaining the go-to option for appendicitis, unless there is a safety reason for not performing the surgery.

Patients come in and want their appendix out immediately, he said, and surgery offers a quick option with short length of stay and few complications.

Additionally, he said, if patients are told that, with antibiotics, “there’s a 1 in 3 chance you’re going to need [an appendectomy] in the next 3 months, I think most people would say, ‘Just take it out then,’ ” he said.

Can research decide which is best?

The controversy has been well studied. But with no clear answer in any of the studies about whether appendectomy or use of antibiotics is better, should the current study put the research to rest?

Flum told Medscape Medical News that this study, which is three times the size of the next-largest study, makes clear “there are choices.”

Previous trials in Europe “did not move the needle” on the issue, he said, “in part because they didn’t include the patients who typically get appendectomies.”

He said their team tried to build on those studies and include “typical patients in typical hospitals with typical appendicitis” and found that both surgery and antibiotics are safe and have advantages and disadvantages, depending on the patient.

Smink says one thing that has been definitively answered with this trial is that patients with appendicolith are “more likely to fail with antibiotics.”

Previous trials have excluded patients with appendicolith, and this one did not.

“That’s something we’ve not really known for sure but we’ve assumed,” he said.

But now, Smink says, he thinks the research on the topic has gone about as far as it can go.

He notes that none of the trials has shown antibiotics to be better than appendectomy. “I have a hard time believing we are going to find anything different if we did another study like this. This is a really well-done one,” he said.

“If the best you can do is show noninferiority, which is where we are with these studies on appendicitis, you’re always going to have both options, which is great for patients and doctors,” he said.

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The original article lists the authors’ relevant financial relationships. Jacobs and Smink reported no such relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients given antibiotics for appendicitis fared no worse in quality of life, at least in the short term, than did patients whose appendix was removed, according to a large, randomized, nonblinded, noninferiority study published online Oct. 5 in The New England Journal of Medicine.

One expert says the body of data, including this trial, indicates that the best appendicitis treatment now comes down to individual patients and choice.

David Flum, MD, director of the Surgical Outcomes Research Center at the University of Washington in Seattle, and colleagues conducted the Comparison of Outcomes of Antibiotic Drugs and Appendectomy (CODA) trial, which compared a 10-day course of antibiotics with appendectomy for patients with appendicitis at 25 US centers.

Although some may interpret the study as praising the potential role of antibiotics, the author of an accompanying editorial warns against rushing to antibiotics, even during a pandemic when hospital resources may be strained.

In the study of 1552 adults (414 with an appendicolith), 776 were randomly assigned to the antibiotics group and 776 to appendectomy (96% of whom underwent a laparoscopic procedure).

After 30 days, antibiotics were found to be noninferior to appendectomy, the standard of treatment for 120 years, as determined on the basis of 30-day scores for the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire (mean difference, 0.01 points; 95% CI, −0.001 to 0.03).

EQ-5D at 30 days was chosen as the primary endpoint because it has been validated as an overall measure of health after appendicitis treatment and the 30-day time frame mimics the typical recovery period for appendectomy, Flum and colleagues explain.

Some results favored appendectomy

However, editorialist Danny Jacobs, MD, MPH, president of Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, points out that about a third (29%) of the patients in the antibiotics group had undergone appendectomy by 90 days.

Appendicolith, a well-established potential complication, he acknowledges, was the main driver of the need for surgery (41% with that complication needed appendectomy), but it was not the sole reason.

Complications were more common in the antibiotics group than in the appendectomy group (8.1 vs 3.5 per 100 participants; rate ratio, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.30 – 3.98). The rate of serious adverse events was 4.0 per 100 participants in the antibiotics group and 3.0 per 100 participants in the appendectomy group (rate ratio, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.67 – 2.50). Additionally, the number of emergency department visits was nearly three times higher in the antibiotics group, and more time was spent in the hospital by that group, Jacobs points out.

He notes that the article mentions circumstances such as the COVID-19 pandemic may figure into consideration when weighing antibiotics against appendectomy. But he warns that there also may be a danger of treatment bias in vulnerable populations and that COVID-19 has highlighted disparities in care overall.

“It will be important to ensure that some people, in particular vulnerable populations, are not offered antibiotic therapy preferentially or without adequate education regarding the longer-term implications,” Jacobs writes.

Flum told Medscape Medical News he agrees with Jacobs that the potential for bias is important.

“We should all be worried that new healthcare options won’t be equally applied,” he said.

But he and his coauthors offer an alternative view of the results of the study.

“In the antibiotics group,” they write, “more than 7 in 10 participants avoided surgery, many were treated on an outpatient basis, and participants and caregivers missed less time at work than with appendectomy.”

Flum said, “[T]hat’s going to be attractive to some patients. Not all, but some.”

Douglas Smink, MD, MPH, chief of surgery at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital in Boston, told Medscape Medical News that he sees this study as an argument for surgery remaining the go-to option for appendicitis, unless there is a safety reason for not performing the surgery.

Patients come in and want their appendix out immediately, he said, and surgery offers a quick option with short length of stay and few complications.

Additionally, he said, if patients are told that, with antibiotics, “there’s a 1 in 3 chance you’re going to need [an appendectomy] in the next 3 months, I think most people would say, ‘Just take it out then,’ ” he said.

Can research decide which is best?

The controversy has been well studied. But with no clear answer in any of the studies about whether appendectomy or use of antibiotics is better, should the current study put the research to rest?

Flum told Medscape Medical News that this study, which is three times the size of the next-largest study, makes clear “there are choices.”

Previous trials in Europe “did not move the needle” on the issue, he said, “in part because they didn’t include the patients who typically get appendectomies.”

He said their team tried to build on those studies and include “typical patients in typical hospitals with typical appendicitis” and found that both surgery and antibiotics are safe and have advantages and disadvantages, depending on the patient.

Smink says one thing that has been definitively answered with this trial is that patients with appendicolith are “more likely to fail with antibiotics.”

Previous trials have excluded patients with appendicolith, and this one did not.

“That’s something we’ve not really known for sure but we’ve assumed,” he said.

But now, Smink says, he thinks the research on the topic has gone about as far as it can go.

He notes that none of the trials has shown antibiotics to be better than appendectomy. “I have a hard time believing we are going to find anything different if we did another study like this. This is a really well-done one,” he said.

“If the best you can do is show noninferiority, which is where we are with these studies on appendicitis, you’re always going to have both options, which is great for patients and doctors,” he said.

The study was funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The original article lists the authors’ relevant financial relationships. Jacobs and Smink reported no such relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Diabetes-related amputations on the rise in older adults

The recent resurgence in diabetes-related lower-extremity amputations in the United States is not limited to younger adults, according to the author of a recent study that documents similar increases among an older population of Medicare beneficiaries.

While the rate of amputations fell among these older adults from 2000 to 2009, it increased significantly from 2009 to 2017, albeit at a “less severe rate” than recently reported in younger populations, said study investigator Jessica Harding, PhD.

The rate of nontraumatic lower extremity amputation (NLEA) was ticking upward by more than 1% per year over the 2009-2017 period, according to Dr. Harding, assistant professor in the department of surgery at Emory University, Atlanta.

This latest report follows one from last year, published in Diabetes Care, that documented an annual percentage increase approaching 6% between 2009 and 2015, driven by larger increases among adults 18-64 years of age, as well as an increase among men.

It’s not clear why rates of NLEA would be on the rise among younger and older adults in the United States, Dr. Harding said, though factors she said could be implicated include changes in amputation practice, increased comorbidities, higher insulin costs, or shortcomings in early prevention programs.

“We need large-scale studies with granular data to tease out key risk factors that could help identify the drivers of these increases in amputations,” Dr. Harding said in a presentation at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“In the interim, increased attention to preventive foot care across the age spectrum could benefit adults with diabetes,” she added.

Devastating complication in older adults

The latest findings from Dr. Harding and coauthors emphasize the importance of a “team approach” to early prevention in older adults with diabetes, said Derek LeRoith, MD, PhD, director of research in the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and bone diseases with Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“If you take a 75-year-old or even an 80-year-old, their life expectancy can still be a good 10 years or more,” Dr. LeRoith said in an interview. “We shouldn’t give up on them – we should be treating them to prevent complications.”

Lower-extremity amputation is a “particularly devastating” complication that can compromise mobility, ability to exercise, and motivation, according to Dr. LeRoith, lead author of a recent Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline that urges referral of older adults with diabetes to a podiatrist, orthopedist, or vascular specialist for preventive care.

“Quite often, treating their glucose or high blood pressure will be much more difficult because of these changes,” he said.

Lower extremity amputation trends upward

Rates of NLEA declined for years, only to rebound by 50%, according to authors of a recent analysis of Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data reported last year. In their report, the age-standardized diabetes-related NLEA rate per 1,000 adults with diabetes went from 5.30 in 2000, down to 3.07 in 2009/2010, and back up to 4.62 by 2015 (Diabetes Care. 2019 Jan;42:50-4).

The resurgence was fueled mainly by an increased rate of amputations in younger and middle-aged adults and men, and through increases in minor amputations, notably the toe, according to the investigators. “These changes in trend are concerning because of the disabling and costly consequences of NLEAs as well as what they may mean for the direction of efforts to reduce diabetes-related complications,” authors of that report said at the time.

In the current study, Dr. Harding and colleagues included Medicare Parts A and B claims data for beneficiaries enrolled from 2000 to 2017. There were 4.6 million Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with diabetes in 2000, increasing to 6.9 million in 2017, she reported at the virtual ADA meeting.

Rates of NLEA followed a trajectory similar to what was seen in the earlier NIS report, falling from 8.5 per 1,000 persons in 2000 to 4.4 in 2009, for an annual percentage change of –7.9 (P < .001), Dr. Harding said. Then rates ticked upward again, to 4.8 in 2017, for an annual percentage change of 1.2 over that later period (P < .001).

While the trend was similar for most subgroups analyzed, the absolute rates were highest among men and black individuals in this older patient population, reported Dr. Harding and coauthors.

Dr. Harding said she and coauthors had no disclosures related to the research, which was performed as a collaboration between Emory University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Diabetes Translation.

SOURCE: Harding J. ADA 2020, Abstract 106-OR.

The recent resurgence in diabetes-related lower-extremity amputations in the United States is not limited to younger adults, according to the author of a recent study that documents similar increases among an older population of Medicare beneficiaries.

While the rate of amputations fell among these older adults from 2000 to 2009, it increased significantly from 2009 to 2017, albeit at a “less severe rate” than recently reported in younger populations, said study investigator Jessica Harding, PhD.

The rate of nontraumatic lower extremity amputation (NLEA) was ticking upward by more than 1% per year over the 2009-2017 period, according to Dr. Harding, assistant professor in the department of surgery at Emory University, Atlanta.

This latest report follows one from last year, published in Diabetes Care, that documented an annual percentage increase approaching 6% between 2009 and 2015, driven by larger increases among adults 18-64 years of age, as well as an increase among men.

It’s not clear why rates of NLEA would be on the rise among younger and older adults in the United States, Dr. Harding said, though factors she said could be implicated include changes in amputation practice, increased comorbidities, higher insulin costs, or shortcomings in early prevention programs.

“We need large-scale studies with granular data to tease out key risk factors that could help identify the drivers of these increases in amputations,” Dr. Harding said in a presentation at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“In the interim, increased attention to preventive foot care across the age spectrum could benefit adults with diabetes,” she added.

Devastating complication in older adults

The latest findings from Dr. Harding and coauthors emphasize the importance of a “team approach” to early prevention in older adults with diabetes, said Derek LeRoith, MD, PhD, director of research in the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and bone diseases with Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“If you take a 75-year-old or even an 80-year-old, their life expectancy can still be a good 10 years or more,” Dr. LeRoith said in an interview. “We shouldn’t give up on them – we should be treating them to prevent complications.”

Lower-extremity amputation is a “particularly devastating” complication that can compromise mobility, ability to exercise, and motivation, according to Dr. LeRoith, lead author of a recent Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline that urges referral of older adults with diabetes to a podiatrist, orthopedist, or vascular specialist for preventive care.

“Quite often, treating their glucose or high blood pressure will be much more difficult because of these changes,” he said.

Lower extremity amputation trends upward

Rates of NLEA declined for years, only to rebound by 50%, according to authors of a recent analysis of Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data reported last year. In their report, the age-standardized diabetes-related NLEA rate per 1,000 adults with diabetes went from 5.30 in 2000, down to 3.07 in 2009/2010, and back up to 4.62 by 2015 (Diabetes Care. 2019 Jan;42:50-4).

The resurgence was fueled mainly by an increased rate of amputations in younger and middle-aged adults and men, and through increases in minor amputations, notably the toe, according to the investigators. “These changes in trend are concerning because of the disabling and costly consequences of NLEAs as well as what they may mean for the direction of efforts to reduce diabetes-related complications,” authors of that report said at the time.

In the current study, Dr. Harding and colleagues included Medicare Parts A and B claims data for beneficiaries enrolled from 2000 to 2017. There were 4.6 million Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with diabetes in 2000, increasing to 6.9 million in 2017, she reported at the virtual ADA meeting.

Rates of NLEA followed a trajectory similar to what was seen in the earlier NIS report, falling from 8.5 per 1,000 persons in 2000 to 4.4 in 2009, for an annual percentage change of –7.9 (P < .001), Dr. Harding said. Then rates ticked upward again, to 4.8 in 2017, for an annual percentage change of 1.2 over that later period (P < .001).

While the trend was similar for most subgroups analyzed, the absolute rates were highest among men and black individuals in this older patient population, reported Dr. Harding and coauthors.

Dr. Harding said she and coauthors had no disclosures related to the research, which was performed as a collaboration between Emory University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Diabetes Translation.

SOURCE: Harding J. ADA 2020, Abstract 106-OR.

The recent resurgence in diabetes-related lower-extremity amputations in the United States is not limited to younger adults, according to the author of a recent study that documents similar increases among an older population of Medicare beneficiaries.

While the rate of amputations fell among these older adults from 2000 to 2009, it increased significantly from 2009 to 2017, albeit at a “less severe rate” than recently reported in younger populations, said study investigator Jessica Harding, PhD.

The rate of nontraumatic lower extremity amputation (NLEA) was ticking upward by more than 1% per year over the 2009-2017 period, according to Dr. Harding, assistant professor in the department of surgery at Emory University, Atlanta.

This latest report follows one from last year, published in Diabetes Care, that documented an annual percentage increase approaching 6% between 2009 and 2015, driven by larger increases among adults 18-64 years of age, as well as an increase among men.

It’s not clear why rates of NLEA would be on the rise among younger and older adults in the United States, Dr. Harding said, though factors she said could be implicated include changes in amputation practice, increased comorbidities, higher insulin costs, or shortcomings in early prevention programs.

“We need large-scale studies with granular data to tease out key risk factors that could help identify the drivers of these increases in amputations,” Dr. Harding said in a presentation at the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“In the interim, increased attention to preventive foot care across the age spectrum could benefit adults with diabetes,” she added.

Devastating complication in older adults

The latest findings from Dr. Harding and coauthors emphasize the importance of a “team approach” to early prevention in older adults with diabetes, said Derek LeRoith, MD, PhD, director of research in the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and bone diseases with Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“If you take a 75-year-old or even an 80-year-old, their life expectancy can still be a good 10 years or more,” Dr. LeRoith said in an interview. “We shouldn’t give up on them – we should be treating them to prevent complications.”

Lower-extremity amputation is a “particularly devastating” complication that can compromise mobility, ability to exercise, and motivation, according to Dr. LeRoith, lead author of a recent Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline that urges referral of older adults with diabetes to a podiatrist, orthopedist, or vascular specialist for preventive care.

“Quite often, treating their glucose or high blood pressure will be much more difficult because of these changes,” he said.

Lower extremity amputation trends upward

Rates of NLEA declined for years, only to rebound by 50%, according to authors of a recent analysis of Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data reported last year. In their report, the age-standardized diabetes-related NLEA rate per 1,000 adults with diabetes went from 5.30 in 2000, down to 3.07 in 2009/2010, and back up to 4.62 by 2015 (Diabetes Care. 2019 Jan;42:50-4).

The resurgence was fueled mainly by an increased rate of amputations in younger and middle-aged adults and men, and through increases in minor amputations, notably the toe, according to the investigators. “These changes in trend are concerning because of the disabling and costly consequences of NLEAs as well as what they may mean for the direction of efforts to reduce diabetes-related complications,” authors of that report said at the time.

In the current study, Dr. Harding and colleagues included Medicare Parts A and B claims data for beneficiaries enrolled from 2000 to 2017. There were 4.6 million Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with diabetes in 2000, increasing to 6.9 million in 2017, she reported at the virtual ADA meeting.

Rates of NLEA followed a trajectory similar to what was seen in the earlier NIS report, falling from 8.5 per 1,000 persons in 2000 to 4.4 in 2009, for an annual percentage change of –7.9 (P < .001), Dr. Harding said. Then rates ticked upward again, to 4.8 in 2017, for an annual percentage change of 1.2 over that later period (P < .001).

While the trend was similar for most subgroups analyzed, the absolute rates were highest among men and black individuals in this older patient population, reported Dr. Harding and coauthors.

Dr. Harding said she and coauthors had no disclosures related to the research, which was performed as a collaboration between Emory University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Diabetes Translation.

SOURCE: Harding J. ADA 2020, Abstract 106-OR.

FROM ADA 2020

Metformin use linked to improved surgery outcomes

Patients with type 2 diabetes who take metformin may have lower risk-adjusted mortality and readmission rates after surgery than do those who don’t take metformin, findings from a large retrospective cohort study suggest.

Of 10,088 individuals with diabetes who underwent a major surgery requiring hospital admission between January 1, 2010, and January 1, 2016, a total of 5,962 (59%) had received a prescription for metformin in the 180 days before surgery, and 5,460 of those patients were propensity score–matched to controls who did not receive a metformin prescription.

The study participants had a mean age of 67.7 years and underwent surgery requiring general anesthesia and postoperative admission at any of 15 hospitals in a single Pennsylvania health system. In addition to being prescribed metformin within 180 days before surgery, they also had metformin on their list of active medications at their most recent preoperative encounter before the surgery. The were followed until December 18, 2018.

In all, the 90-day and 5-year mortality hazards were reduced by 28% and 26%, respectively, in the metformin prescription recipients, compared with the propensity score–matched controls (hazard ratios, 0.72 and 0.74, respectively), Katherine M. Reitz, MD, and colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh reported in JAMA Surgery.

The readmission hazard – with mortality as a competing risk – was reduced by 16% at 30 days and 14% at 90 days (sub-HRs, 0.84 and 0.86, respectively), the researchers found.

“Hospital readmissions among those with preoperative metformin prescriptions were observed by postdischarge days 30 and 90 (304 [11%] and 538 [20.1%], respectively), whereas among those without prescriptions, 361 readmissions (13%) occurred by day 30 and 614 (23%) by day 90,” they wrote.

The investigators also noted that inflammation was reduced in patients who received a metformin prescription, compared with those who did not (mean preoperative neutrophil to leukocyte ratio, 4.5 vs. 5.0, respectively).

“In the full cohort, multivariable regression analysis similarly demonstrated that metformin was associated with a reduced hazard for both 90-day and 5-year mortality (adjusted HRs, 0.77 and 0.80, respectively) and for 30-day and 90-day readmission (aHR, 0.83 and 0.86), with mortality as a competing risk,” they added.

The findings support those from previous studies showing a decrease in all-cause mortality among diabetes patients taking metformin, said the researchers, noting that those patients had fewer age-related chronic diseases.

“These associations may reflect the anti-aging properties of metformin against the onset of disease or diabetes-associated complications. This study extends these finding by demonstrating that preoperative metformin prescriptions were associated with a reduction in postoperative mortality and readmission, a surrogate for postoperative complications, and with long-term mortality,” they wrote.

The study was limited by a number of factors, such as the potential for residual confounding inherent in retrospective analyses and a lack of adequate power to evaluate the association between metformin use and outcomes for individual surgical procedures. But the authors added that the findings are of note, because adults with comorbidities, such as diabetes, have less physiological reserve and an increased postoperative mortality and readmission rate. The results, therefore, warrant investigation with a prospective randomized clinical trial, they concluded.

In an accompanying editorial, Elizabeth L. George, MD, and Sherry M. Wren, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University wrote that the study “demonstrates how variables, besides coexisting medical diseases, can affect surgical outcomes.”

“Metformin now joins beta-blockers, statins, and immunonutrition as preoperative agents associated with improved surgical outcomes,” they wrote, adding that future studies should factor in statin use and whether those and other medications should be continued postoperatively because metformin is often held after surgery owing to concerns about contrast agent interactions, whereas statin continuation is recommended.

Future studies of metformin in this setting should exclude patients who are taking statins, or look at possible interactions between the two agents, they said, adding that they would be “interested in seeing a subanalysis of this data set that excludes patients who were prescribed statins.”

“Those data would further solidify the role of metformin as a possible modifiable perioperative factor,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Reitz reported having no disclosures. Dr. George and Dr. Wren also reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Reitz K et al. JAMA Surg. 2020 Apr 8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0416.

Patients with type 2 diabetes who take metformin may have lower risk-adjusted mortality and readmission rates after surgery than do those who don’t take metformin, findings from a large retrospective cohort study suggest.

Of 10,088 individuals with diabetes who underwent a major surgery requiring hospital admission between January 1, 2010, and January 1, 2016, a total of 5,962 (59%) had received a prescription for metformin in the 180 days before surgery, and 5,460 of those patients were propensity score–matched to controls who did not receive a metformin prescription.

The study participants had a mean age of 67.7 years and underwent surgery requiring general anesthesia and postoperative admission at any of 15 hospitals in a single Pennsylvania health system. In addition to being prescribed metformin within 180 days before surgery, they also had metformin on their list of active medications at their most recent preoperative encounter before the surgery. The were followed until December 18, 2018.

In all, the 90-day and 5-year mortality hazards were reduced by 28% and 26%, respectively, in the metformin prescription recipients, compared with the propensity score–matched controls (hazard ratios, 0.72 and 0.74, respectively), Katherine M. Reitz, MD, and colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh reported in JAMA Surgery.

The readmission hazard – with mortality as a competing risk – was reduced by 16% at 30 days and 14% at 90 days (sub-HRs, 0.84 and 0.86, respectively), the researchers found.

“Hospital readmissions among those with preoperative metformin prescriptions were observed by postdischarge days 30 and 90 (304 [11%] and 538 [20.1%], respectively), whereas among those without prescriptions, 361 readmissions (13%) occurred by day 30 and 614 (23%) by day 90,” they wrote.

The investigators also noted that inflammation was reduced in patients who received a metformin prescription, compared with those who did not (mean preoperative neutrophil to leukocyte ratio, 4.5 vs. 5.0, respectively).

“In the full cohort, multivariable regression analysis similarly demonstrated that metformin was associated with a reduced hazard for both 90-day and 5-year mortality (adjusted HRs, 0.77 and 0.80, respectively) and for 30-day and 90-day readmission (aHR, 0.83 and 0.86), with mortality as a competing risk,” they added.

The findings support those from previous studies showing a decrease in all-cause mortality among diabetes patients taking metformin, said the researchers, noting that those patients had fewer age-related chronic diseases.

“These associations may reflect the anti-aging properties of metformin against the onset of disease or diabetes-associated complications. This study extends these finding by demonstrating that preoperative metformin prescriptions were associated with a reduction in postoperative mortality and readmission, a surrogate for postoperative complications, and with long-term mortality,” they wrote.