User login

Female cancer researchers receive less funding than male counterparts

Female cancer researchers receive significantly less funding than their male counterparts in terms of total investment, number of awards, and mean and median funding, according to an analysis of data on public and philanthropic cancer research funding awarded to U.K. institutions between 2000 and 2013.

In an analysis of 4,186 awards totaling 2.33 billion pounds, 2,890 grants (69%) with a total value of 1.82 billion pounds (78%) were awarded to male primary investigators (PIs), compared with just 1,296 grants (31%) with a total value of 512 million pounds(22%) for female PIs, investigators reported in BMJ Open.

Investigators studied openly accessible information on funding awards from public and philanthropic sources including the Medical Research Council, Department of Health, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Engineering and Physical Science Research Council, Wellcome Trust, European Commission, and nine members of the Association of Medical Research Charities. Awards were excluded if they were not relevant to oncology, led by a non-U.K. institution, and/or not considered a research and development activity, wrote Charlie D. Zhou, MD, of the Royal Free NHS Foundation Trust Department of Nuclear Medicine in London, and coauthors.

Median grant value was greater for men (252,647 pounds; interquartile range, 127,343-553,560 pounds) than for women (198,485 pounds; IQR, 99,317-382,650 pounds) (P less than .001). Mean grant value was also greater for men (630,324 pounds; standard deviation, 1,662,559 pounds) than for women (394,730 pounds; SD, 666,574 pounds), Dr. Zhou and colleagues reported.

Large funding discrepancies were seen for sex-specific cancer research. For instance, males received 13.8, 3.5, and 2.0 times the investment of their female counterparts in total, mean, and median prostate cancer funding, respectively. Likewise, men received 9.9, 6.6, and 2.9 times the funding of women PIs in total, mean, and median funding, respectively, for cervical cancer research. This pattern was true for ovarian cancer and breast cancer research, as well.

Men also received significantly greater median funding at all points of the research and development pipeline. For preclinical, phase 1, 2, or 3 clinical trials; and public health, men received 20%, 90%, and 50% more, respectively (P less than .001); for product development and cross-disciplinary research, the difference was 50% and 20%, respectively (P less than .01).

The results of the analysis demonstrate that “female PIs clearly and consistently receive less funding than their male counterparts,” the authors wrote. Although the study results are descriptive in nature and do not identify the underlying mechanisms for these discrepancies, they “demonstrate substantial gender imbalances in cancer research investment.

“We would strongly urge policy makers, funders and the academic and scientific community to investigate the factors leading to our observed differences and seek to ensure that women are appropriately supported in scientific endeavor,” they concluded.

No disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Zhou CD et al. BMJ Open. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018625.

Female cancer researchers receive significantly less funding than their male counterparts in terms of total investment, number of awards, and mean and median funding, according to an analysis of data on public and philanthropic cancer research funding awarded to U.K. institutions between 2000 and 2013.

In an analysis of 4,186 awards totaling 2.33 billion pounds, 2,890 grants (69%) with a total value of 1.82 billion pounds (78%) were awarded to male primary investigators (PIs), compared with just 1,296 grants (31%) with a total value of 512 million pounds(22%) for female PIs, investigators reported in BMJ Open.

Investigators studied openly accessible information on funding awards from public and philanthropic sources including the Medical Research Council, Department of Health, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Engineering and Physical Science Research Council, Wellcome Trust, European Commission, and nine members of the Association of Medical Research Charities. Awards were excluded if they were not relevant to oncology, led by a non-U.K. institution, and/or not considered a research and development activity, wrote Charlie D. Zhou, MD, of the Royal Free NHS Foundation Trust Department of Nuclear Medicine in London, and coauthors.

Median grant value was greater for men (252,647 pounds; interquartile range, 127,343-553,560 pounds) than for women (198,485 pounds; IQR, 99,317-382,650 pounds) (P less than .001). Mean grant value was also greater for men (630,324 pounds; standard deviation, 1,662,559 pounds) than for women (394,730 pounds; SD, 666,574 pounds), Dr. Zhou and colleagues reported.

Large funding discrepancies were seen for sex-specific cancer research. For instance, males received 13.8, 3.5, and 2.0 times the investment of their female counterparts in total, mean, and median prostate cancer funding, respectively. Likewise, men received 9.9, 6.6, and 2.9 times the funding of women PIs in total, mean, and median funding, respectively, for cervical cancer research. This pattern was true for ovarian cancer and breast cancer research, as well.

Men also received significantly greater median funding at all points of the research and development pipeline. For preclinical, phase 1, 2, or 3 clinical trials; and public health, men received 20%, 90%, and 50% more, respectively (P less than .001); for product development and cross-disciplinary research, the difference was 50% and 20%, respectively (P less than .01).

The results of the analysis demonstrate that “female PIs clearly and consistently receive less funding than their male counterparts,” the authors wrote. Although the study results are descriptive in nature and do not identify the underlying mechanisms for these discrepancies, they “demonstrate substantial gender imbalances in cancer research investment.

“We would strongly urge policy makers, funders and the academic and scientific community to investigate the factors leading to our observed differences and seek to ensure that women are appropriately supported in scientific endeavor,” they concluded.

No disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Zhou CD et al. BMJ Open. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018625.

Female cancer researchers receive significantly less funding than their male counterparts in terms of total investment, number of awards, and mean and median funding, according to an analysis of data on public and philanthropic cancer research funding awarded to U.K. institutions between 2000 and 2013.

In an analysis of 4,186 awards totaling 2.33 billion pounds, 2,890 grants (69%) with a total value of 1.82 billion pounds (78%) were awarded to male primary investigators (PIs), compared with just 1,296 grants (31%) with a total value of 512 million pounds(22%) for female PIs, investigators reported in BMJ Open.

Investigators studied openly accessible information on funding awards from public and philanthropic sources including the Medical Research Council, Department of Health, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Engineering and Physical Science Research Council, Wellcome Trust, European Commission, and nine members of the Association of Medical Research Charities. Awards were excluded if they were not relevant to oncology, led by a non-U.K. institution, and/or not considered a research and development activity, wrote Charlie D. Zhou, MD, of the Royal Free NHS Foundation Trust Department of Nuclear Medicine in London, and coauthors.

Median grant value was greater for men (252,647 pounds; interquartile range, 127,343-553,560 pounds) than for women (198,485 pounds; IQR, 99,317-382,650 pounds) (P less than .001). Mean grant value was also greater for men (630,324 pounds; standard deviation, 1,662,559 pounds) than for women (394,730 pounds; SD, 666,574 pounds), Dr. Zhou and colleagues reported.

Large funding discrepancies were seen for sex-specific cancer research. For instance, males received 13.8, 3.5, and 2.0 times the investment of their female counterparts in total, mean, and median prostate cancer funding, respectively. Likewise, men received 9.9, 6.6, and 2.9 times the funding of women PIs in total, mean, and median funding, respectively, for cervical cancer research. This pattern was true for ovarian cancer and breast cancer research, as well.

Men also received significantly greater median funding at all points of the research and development pipeline. For preclinical, phase 1, 2, or 3 clinical trials; and public health, men received 20%, 90%, and 50% more, respectively (P less than .001); for product development and cross-disciplinary research, the difference was 50% and 20%, respectively (P less than .01).

The results of the analysis demonstrate that “female PIs clearly and consistently receive less funding than their male counterparts,” the authors wrote. Although the study results are descriptive in nature and do not identify the underlying mechanisms for these discrepancies, they “demonstrate substantial gender imbalances in cancer research investment.

“We would strongly urge policy makers, funders and the academic and scientific community to investigate the factors leading to our observed differences and seek to ensure that women are appropriately supported in scientific endeavor,” they concluded.

No disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Zhou CD et al. BMJ Open. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018625.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Key clinical point: Female cancer researchers receive significantly less funding than their male counterparts.

Major finding: Of 4,186 awards, 2,890 grants (69%) were awarded to male primary investigators (PIs), compared with 1,296 grants (31%) for female PIs.

Study details: An analysis of data on public and philanthropic cancer research funding awarded to U.K. institutions between 2000 and 2013.

Disclosures: No disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Zhou CD et al. BMJ Open. 2018 Apr 30. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018625.

Immediate postresection gemcitabine tops saline in low-grade non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer

For patients with suspected low-grade non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer, immediate postresection treatment with intravesicular gemcitabine significantly cut recurrence rates in a double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, estimated rates of 4-year recurrence were 35% with gemcitabine and 47% with placebo saline (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.48-0.90; P less than .001), reported Edward D. Messing of the University of Rochester, New York, and his associates. Gemcitabine also significantly outperformed placebo in the preplanned analysis of patients with confirmed low-grade non–muscle-invasive urothelial cancer (estimated 4-year recurrence rates , 4% and 54% respectively; HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35-0.81; P = .001).

Intravesicular gemcitabine did not significantly reduce all-cause mortality or tumor progression to muscle invasion. “In an underpowered post hoc subgroup analysis, there [also] was no evidence of a benefit of immediate post-TURBT [transurethral resection of bladder tumor] gemcitabine in patients with high-grade non–muscle-invasive urothelial cancer,” the researchers wrote. The report was published May 8 in JAMA.

Robust data already support single-dose intravesicular chemotherapy with mitomycin C or epirubicin immediately after patients undergo TURBT. But in reality, this practice is uncommon in the United States. Meanwhile, systemic gemcitabine already is used to treat bladder cancer, and its intravesicular use appears safe and at least as effective as other chemotherapies, the investigators noted. Therefore, the SWOG S0337 trial enrolled 416 symptomatic patients with suspected low-grade papillary urothelial cancer who received a single intravesicular instillation of either gemcitabine (2 g in 100 mL saline) or saline (100 mL) within 3 hours after transurethral resection of TURBT.

Ten percent of patients did not receive study drug instillation, usually for medical reasons. There were no grade 4-5 adverse events. Grade 3 or lower adverse events did not significantly differ between groups. The study did not capture reliable data on tumor size or treatment at or after recurrence, the researchers said. Taken together, the findings “support using this therapy, but further research is needed to compare gemcitabine with other intravesical agents.”

The National Cancer Institute provided funding. Eli Lilly provided the gemcitabine used in the study. Dr. Messing reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to BioCancell, Incyte, and various other biopharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Messing EM et al. JAMA. 2018 May 8;319(18):1880-8.

The well designed and executed study “provides important results for patients and physicians alike,” Samuel D. Kaffenberger, MD, David C. Miller, MD, MPH, and Matthew E. Nielsen, MD, MS, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study report in JAMA.

Recurrent bladder cancer exacts major emotional, medical, and monetary costs, the experts stressed. “The natural history of frequent recurrences drives a uniquely intensive and costly program of invasive surveillance and treatment.”

Thus, while the trial results are promising, their “ultimate benefit” will depend on “more consistent and proficient use of intravesical gemcitabine than has been observed for mitomycin,” they said. Disseminating this “simple, safe, effective, and affordable” treatment will require education and mobilization of patients and physicians, advocacy organizations, and health care system leaders.

Dr. Kaffenberger and Dr. Miller are at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Nielsen is at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Nielsen disclosed stock options via the Grand Rounds Medical Advisory Board. Dr. Miller disclosed ties to Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. Dr. Kaffenberger reported having no conflicts of interest. These comments summarize their editorial (JAMA. 2018 319;18:1864-65).

The well designed and executed study “provides important results for patients and physicians alike,” Samuel D. Kaffenberger, MD, David C. Miller, MD, MPH, and Matthew E. Nielsen, MD, MS, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study report in JAMA.

Recurrent bladder cancer exacts major emotional, medical, and monetary costs, the experts stressed. “The natural history of frequent recurrences drives a uniquely intensive and costly program of invasive surveillance and treatment.”

Thus, while the trial results are promising, their “ultimate benefit” will depend on “more consistent and proficient use of intravesical gemcitabine than has been observed for mitomycin,” they said. Disseminating this “simple, safe, effective, and affordable” treatment will require education and mobilization of patients and physicians, advocacy organizations, and health care system leaders.

Dr. Kaffenberger and Dr. Miller are at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Nielsen is at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Nielsen disclosed stock options via the Grand Rounds Medical Advisory Board. Dr. Miller disclosed ties to Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. Dr. Kaffenberger reported having no conflicts of interest. These comments summarize their editorial (JAMA. 2018 319;18:1864-65).

The well designed and executed study “provides important results for patients and physicians alike,” Samuel D. Kaffenberger, MD, David C. Miller, MD, MPH, and Matthew E. Nielsen, MD, MS, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study report in JAMA.

Recurrent bladder cancer exacts major emotional, medical, and monetary costs, the experts stressed. “The natural history of frequent recurrences drives a uniquely intensive and costly program of invasive surveillance and treatment.”

Thus, while the trial results are promising, their “ultimate benefit” will depend on “more consistent and proficient use of intravesical gemcitabine than has been observed for mitomycin,” they said. Disseminating this “simple, safe, effective, and affordable” treatment will require education and mobilization of patients and physicians, advocacy organizations, and health care system leaders.

Dr. Kaffenberger and Dr. Miller are at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Nielsen is at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Nielsen disclosed stock options via the Grand Rounds Medical Advisory Board. Dr. Miller disclosed ties to Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. Dr. Kaffenberger reported having no conflicts of interest. These comments summarize their editorial (JAMA. 2018 319;18:1864-65).

For patients with suspected low-grade non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer, immediate postresection treatment with intravesicular gemcitabine significantly cut recurrence rates in a double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, estimated rates of 4-year recurrence were 35% with gemcitabine and 47% with placebo saline (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.48-0.90; P less than .001), reported Edward D. Messing of the University of Rochester, New York, and his associates. Gemcitabine also significantly outperformed placebo in the preplanned analysis of patients with confirmed low-grade non–muscle-invasive urothelial cancer (estimated 4-year recurrence rates , 4% and 54% respectively; HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35-0.81; P = .001).

Intravesicular gemcitabine did not significantly reduce all-cause mortality or tumor progression to muscle invasion. “In an underpowered post hoc subgroup analysis, there [also] was no evidence of a benefit of immediate post-TURBT [transurethral resection of bladder tumor] gemcitabine in patients with high-grade non–muscle-invasive urothelial cancer,” the researchers wrote. The report was published May 8 in JAMA.

Robust data already support single-dose intravesicular chemotherapy with mitomycin C or epirubicin immediately after patients undergo TURBT. But in reality, this practice is uncommon in the United States. Meanwhile, systemic gemcitabine already is used to treat bladder cancer, and its intravesicular use appears safe and at least as effective as other chemotherapies, the investigators noted. Therefore, the SWOG S0337 trial enrolled 416 symptomatic patients with suspected low-grade papillary urothelial cancer who received a single intravesicular instillation of either gemcitabine (2 g in 100 mL saline) or saline (100 mL) within 3 hours after transurethral resection of TURBT.

Ten percent of patients did not receive study drug instillation, usually for medical reasons. There were no grade 4-5 adverse events. Grade 3 or lower adverse events did not significantly differ between groups. The study did not capture reliable data on tumor size or treatment at or after recurrence, the researchers said. Taken together, the findings “support using this therapy, but further research is needed to compare gemcitabine with other intravesical agents.”

The National Cancer Institute provided funding. Eli Lilly provided the gemcitabine used in the study. Dr. Messing reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to BioCancell, Incyte, and various other biopharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Messing EM et al. JAMA. 2018 May 8;319(18):1880-8.

For patients with suspected low-grade non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer, immediate postresection treatment with intravesicular gemcitabine significantly cut recurrence rates in a double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, estimated rates of 4-year recurrence were 35% with gemcitabine and 47% with placebo saline (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.48-0.90; P less than .001), reported Edward D. Messing of the University of Rochester, New York, and his associates. Gemcitabine also significantly outperformed placebo in the preplanned analysis of patients with confirmed low-grade non–muscle-invasive urothelial cancer (estimated 4-year recurrence rates , 4% and 54% respectively; HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35-0.81; P = .001).

Intravesicular gemcitabine did not significantly reduce all-cause mortality or tumor progression to muscle invasion. “In an underpowered post hoc subgroup analysis, there [also] was no evidence of a benefit of immediate post-TURBT [transurethral resection of bladder tumor] gemcitabine in patients with high-grade non–muscle-invasive urothelial cancer,” the researchers wrote. The report was published May 8 in JAMA.

Robust data already support single-dose intravesicular chemotherapy with mitomycin C or epirubicin immediately after patients undergo TURBT. But in reality, this practice is uncommon in the United States. Meanwhile, systemic gemcitabine already is used to treat bladder cancer, and its intravesicular use appears safe and at least as effective as other chemotherapies, the investigators noted. Therefore, the SWOG S0337 trial enrolled 416 symptomatic patients with suspected low-grade papillary urothelial cancer who received a single intravesicular instillation of either gemcitabine (2 g in 100 mL saline) or saline (100 mL) within 3 hours after transurethral resection of TURBT.

Ten percent of patients did not receive study drug instillation, usually for medical reasons. There were no grade 4-5 adverse events. Grade 3 or lower adverse events did not significantly differ between groups. The study did not capture reliable data on tumor size or treatment at or after recurrence, the researchers said. Taken together, the findings “support using this therapy, but further research is needed to compare gemcitabine with other intravesical agents.”

The National Cancer Institute provided funding. Eli Lilly provided the gemcitabine used in the study. Dr. Messing reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to BioCancell, Incyte, and various other biopharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Messing EM et al. JAMA. 2018 May 8;319(18):1880-8.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Immediate postresection intravesicular gemcitabine significantly reduced the risk of recurrence in patients with suspected low-grade non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Major finding: Estimated rates of 4-year recurrence were 35% with gemcitabine and 47% with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.66; P less than .001).

Study details: Phase 3 multicenter trial of 416 patients randomly assigned to receive gemcitabine (2 g in 100 mL saline) or placebo saline (100 mL) (SWOG S0337).

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute provided funding. Eli Lilly provided the gemcitabine used in the study. Dr. Messing reported having no relevant conflicts of interest. Three coinvestigators disclosed ties to BioCancell, Incyte, and various other biopharmaceutical companies.

Source: Messing EM et al. JAMA. 2018 May 8;319(18):1880-8.

Rare paraneoplastic dermatomyositis secondary to high-grade bladder cancer

The clinical presentation of bladder cancer typically presents with hematuria; changes in voiding habits such as urgency, frequency, and pain; or less commonly, obstructive symptoms. Rarely does bladder cancer first present as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome with an inflammatory myopathy. Inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis have been known to be associated with malignancy, however, in a meta-analysis by Yang and colleagues of 449 patients with dermatomyositis and malignancy there were only 8 cases reported of bladder cancer.1 Herein, we report a paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in the setting of a bladder cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 65-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension and alcohol use presented to the emergency department with worsening pain, stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and inability to lift his arms above his shoulders. During the physical exam, an erythematous purple rash was noted over his chest, neck, and arms. Upon further evaluation, his creatine phosphokinase was 3,500 U/L (reference range 52-336 U/L) suggesting muscle breakdown and possible inflammatory myopathy. A biopsy of the left deltoid and quadriceps muscles was performed and yielded a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. He was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily for his inflammatory myopathy. The patient also reported an unintentional weight loss of 20 lbs. and increasing weakness and inability to swallow, which caused aspiration events without developing pneumonia.

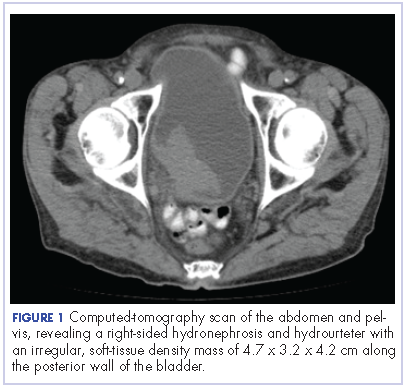

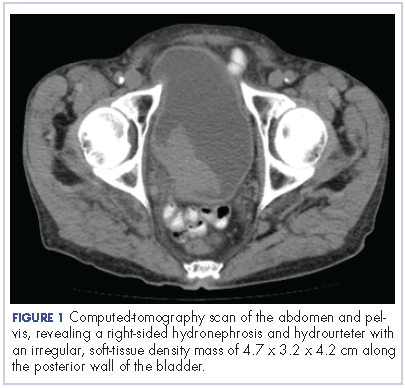

The patient’s symptoms worsened while he was on steroids, and we became concerned about the possibility of a primary malignancy, which led to further work-up. The results of a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed right-sided hydronephrosis and hydrourteter with an irregular, soft-tissue density mass of 4.7 x 3.2 x 4.2 cm along the posterior wall of the bladder (Figure 1).

A cystoscopy was performed with transurethral resection of a bladder tumor that was more than 8 cm in diameter. Because the mass was not fully resectable, only 25% of the tumor burden was removed. The pathology report revealed an invasive, high-grade urothelial cell carcinoma (Figure 2, see PDF). Further imaging ruled out metastatic spread. The patient was continued on steroids. He was not a candidate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy because of his comorbidities and cisplatin ineligibility owing to his significant bilateral hearing deficiencies. Members of a multidisciplinary tumor board decided to move forward with definitive surgery. The patient underwent a robotic-assisted laparoscoptic cystoprostatectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and open ileal conduit urinary diversion. Staging of tumor was determined as pT3b N1 (1/30) M0, LVI+. After the surgery, the patient had resolution of his rash and significant improvement in his muscle weakness with the ability to raise his arms over his head and climb stairs. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not given since he was cisplatin ineligible as a result of his hearing loss. Active surveillance was preferred.

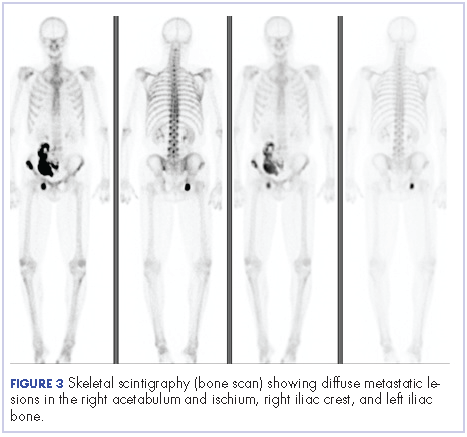

Four months after his cystoprostatectomy, he experienced new-onset hip pain and further imaging, including a bone scan, was performed. It showed metastatic disease in the ischium and iliac crest (Figure 3).

The patient decided to forgo any palliative chemotherapy and to have palliative radiation for pain and enroll in hospice. He died nine months after the initial diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma.

Discussion

Dermatomyositis is one of the inflammatory myopathies with a clinical presentation of proximal muscle weakness and characteristic skin findings of Gottron papules and heliotrope eruption. The most common subgroups of inflammatory myopathies are dermatomyositis, polymyositis, necrotizing autoimmune myopathy, and inclusion body myopathy. The pathogenesis of inflammatory myopathies is not well understood; however, some theories have been described, including: type 1 interferon signaling causing myofiber injury and antibody-complement mediated processes causing ischemia resulting in myofiber injury. 2,3 The diagnoses of inflammatory myopathies may be suggested based on history, physical examination findings, laboratory values showing muscle injury (creatine kinase, aldolase, ALT, AST, LDH), myositis-specific antibodies (antisynthetase autoantibodies), electromyogram, and magnetic-resonance imaging. However, muscle biopsy remains the gold standard.4

The initial treatment of inflammatory myopathies begins with glucocorticoid therapy at 0.5-1.0 mg/kg. This regimen may be titrated down over 6 weeks to a level adequate to control symptoms. Even while on glucocorticoid therapy, this patient’s symptoms continued, along with the development of dysphagia. Dysphagia is another notable symptom of dermatomyositis that may result in aspiration pneumonia with fatal outcomes.5,6,7 Not only did this patient initially respond poorly to corticosteroids, but the unintentional weight loss was another alarming feature prompting further evaluation. That led to the diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma, which was causing the paraneoplastic syndrome.

A paraneoplastic syndrome is a collection of symptoms that are observed in organ systems separate from the primary disease. This process is mostly caused by an autoimmune response to the tumor and nervous system.8 Inflammatory myopathies, such as dermatomyositis, have been shown to be associated with a variety of malignancies as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The most common cancers associated with dermatomyositis are ovarian, lung, pancreatic, stomach, colorectal, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.9 Although an association between dermatomyositis and bladder cancer has been established, very few cases have been reported in the literature. In the Yang meta-analysis, the relative risk of malignancy for patients with dermatomyositis was 5.5%, and of the 449 patients with dermatomyositis who had malignancy, only 8 cases of bladder cancer were reported.1

After a patient has been diagnosed with an inflammatory myopathy, there should be further evaluation for an underling malignancy causing a paraneoplastic process. The risk of these patients having a malignancy overall is 4.5 times higher than patients without dermatomyositis.1 Definite screening recommendations have not been established, but screening should be based on patient’s age, gender, and clinical scenario. The European Federation of Neurological Societies formed a task force to focus on malignancy screening of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes and included dermatomyositis as one of the signs.10 Patients should have a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Women should have a mammogram and a pelvis ultrasound. Men younger than 50 years should consider testes ultrasound, and patients older than 50 years should undergo usual colonoscopy screening.

The risk of malignancy is highest in the first year after diagnosis, but may extend to 5 years after the diagnosis, so repeat screening should be performed 3-6 months after diagnosis, followed with biannual testing for 4 years. If a malignancy is present, then treatment should be tailored to the neoplasm to improve symptoms of myositis; however, response is generally worse than it would be with dermatomyositis in the absence of malignancy. In the present case with bladder cancer, therapies may include platinum-based-chemotherapy, resection, and radiation. Dermatomyositis as a result of a bladder cancer paraneoplastic syndrome is associated with a poor prognosis as demonstrated in the case of this patient and others reported in the literature.11

Even though dermatomyositis is usually a chronic disease process, 87% of patients respond initially to corticosteroid treatment.12 Therefore, treatment should be escalated with an agent such as azathioprine or methotrexate, or, like in this case, an underlying malignancy should be suspected. This case emphasizes the importance of screening patients appropriately for malignancy in patients with an inflammatory myopathy and reveals the poor prognosis associated with this disease.

1. Yang Z, Lin F, Qin B, Liang Y, Zhong R. Polymyositis/dermatomyositis and malignancy risk: a metaanalysis study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(2):282-291.

2. Greenberg, SA. Dermatomyositis and type 1 interferons. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(3):198-203.

3. Dalakas, MC, Hohlfeld, R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362(9388):971-982.

4. Malik A, Hayat G, Kalia JS, Guzman MA. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: clinical approach and management. Front Neurol. 2016;7:64.

5. Sabio JM, Vargas-Hitos JA, Jiménez-Alonso J. Paraneoplastic dermatomyositis associated with bladder cancer. Lupus. 2006;15(9):619-620.

6. Mallon E, Osborne G, Dinneen M, Lane RJ, Glaser M, Bunker CB. Dermatomyositis in association with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24(2):94-96.

7. Hafejee A, Coulson IH. Dysphagia in dermatomyositis secondary to bladder cancer: rapid response to combined immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30(1):93-94.

8. Dalmau J, Gultekin HS, Posner JB. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes: pathogenesis and physiopathology. Brain Pathol. 1999;9(2):275-284.

9. Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigureirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357(9250):96-100.

10. Titulaer, MJ, Soffietti R, Dalmau J, et al. Screening for tumours in paraneoplastic syndromes: report of an EFNS Task Force. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(1):19-e3.

11. Xu R, Zhong Z, Jiang H, Zhang L, Zhao X. A rare paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in bladder cancer with fatal outcome. Urol J. 2013;10(1):815-817.

12. Troyanov Y, Targoff IN, Tremblay JL, Goulet JR, Raymond Y, Senecal JL. Novel classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies based on overlap syndrome features and autoantibodies: analysis of 100 French Canadian patients. Medicine (Baltimore), 2005;84(4):231-249.

The clinical presentation of bladder cancer typically presents with hematuria; changes in voiding habits such as urgency, frequency, and pain; or less commonly, obstructive symptoms. Rarely does bladder cancer first present as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome with an inflammatory myopathy. Inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis have been known to be associated with malignancy, however, in a meta-analysis by Yang and colleagues of 449 patients with dermatomyositis and malignancy there were only 8 cases reported of bladder cancer.1 Herein, we report a paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in the setting of a bladder cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 65-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension and alcohol use presented to the emergency department with worsening pain, stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and inability to lift his arms above his shoulders. During the physical exam, an erythematous purple rash was noted over his chest, neck, and arms. Upon further evaluation, his creatine phosphokinase was 3,500 U/L (reference range 52-336 U/L) suggesting muscle breakdown and possible inflammatory myopathy. A biopsy of the left deltoid and quadriceps muscles was performed and yielded a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. He was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily for his inflammatory myopathy. The patient also reported an unintentional weight loss of 20 lbs. and increasing weakness and inability to swallow, which caused aspiration events without developing pneumonia.

The patient’s symptoms worsened while he was on steroids, and we became concerned about the possibility of a primary malignancy, which led to further work-up. The results of a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed right-sided hydronephrosis and hydrourteter with an irregular, soft-tissue density mass of 4.7 x 3.2 x 4.2 cm along the posterior wall of the bladder (Figure 1).

A cystoscopy was performed with transurethral resection of a bladder tumor that was more than 8 cm in diameter. Because the mass was not fully resectable, only 25% of the tumor burden was removed. The pathology report revealed an invasive, high-grade urothelial cell carcinoma (Figure 2, see PDF). Further imaging ruled out metastatic spread. The patient was continued on steroids. He was not a candidate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy because of his comorbidities and cisplatin ineligibility owing to his significant bilateral hearing deficiencies. Members of a multidisciplinary tumor board decided to move forward with definitive surgery. The patient underwent a robotic-assisted laparoscoptic cystoprostatectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and open ileal conduit urinary diversion. Staging of tumor was determined as pT3b N1 (1/30) M0, LVI+. After the surgery, the patient had resolution of his rash and significant improvement in his muscle weakness with the ability to raise his arms over his head and climb stairs. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not given since he was cisplatin ineligible as a result of his hearing loss. Active surveillance was preferred.

Four months after his cystoprostatectomy, he experienced new-onset hip pain and further imaging, including a bone scan, was performed. It showed metastatic disease in the ischium and iliac crest (Figure 3).

The patient decided to forgo any palliative chemotherapy and to have palliative radiation for pain and enroll in hospice. He died nine months after the initial diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma.

Discussion

Dermatomyositis is one of the inflammatory myopathies with a clinical presentation of proximal muscle weakness and characteristic skin findings of Gottron papules and heliotrope eruption. The most common subgroups of inflammatory myopathies are dermatomyositis, polymyositis, necrotizing autoimmune myopathy, and inclusion body myopathy. The pathogenesis of inflammatory myopathies is not well understood; however, some theories have been described, including: type 1 interferon signaling causing myofiber injury and antibody-complement mediated processes causing ischemia resulting in myofiber injury. 2,3 The diagnoses of inflammatory myopathies may be suggested based on history, physical examination findings, laboratory values showing muscle injury (creatine kinase, aldolase, ALT, AST, LDH), myositis-specific antibodies (antisynthetase autoantibodies), electromyogram, and magnetic-resonance imaging. However, muscle biopsy remains the gold standard.4

The initial treatment of inflammatory myopathies begins with glucocorticoid therapy at 0.5-1.0 mg/kg. This regimen may be titrated down over 6 weeks to a level adequate to control symptoms. Even while on glucocorticoid therapy, this patient’s symptoms continued, along with the development of dysphagia. Dysphagia is another notable symptom of dermatomyositis that may result in aspiration pneumonia with fatal outcomes.5,6,7 Not only did this patient initially respond poorly to corticosteroids, but the unintentional weight loss was another alarming feature prompting further evaluation. That led to the diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma, which was causing the paraneoplastic syndrome.

A paraneoplastic syndrome is a collection of symptoms that are observed in organ systems separate from the primary disease. This process is mostly caused by an autoimmune response to the tumor and nervous system.8 Inflammatory myopathies, such as dermatomyositis, have been shown to be associated with a variety of malignancies as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The most common cancers associated with dermatomyositis are ovarian, lung, pancreatic, stomach, colorectal, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.9 Although an association between dermatomyositis and bladder cancer has been established, very few cases have been reported in the literature. In the Yang meta-analysis, the relative risk of malignancy for patients with dermatomyositis was 5.5%, and of the 449 patients with dermatomyositis who had malignancy, only 8 cases of bladder cancer were reported.1

After a patient has been diagnosed with an inflammatory myopathy, there should be further evaluation for an underling malignancy causing a paraneoplastic process. The risk of these patients having a malignancy overall is 4.5 times higher than patients without dermatomyositis.1 Definite screening recommendations have not been established, but screening should be based on patient’s age, gender, and clinical scenario. The European Federation of Neurological Societies formed a task force to focus on malignancy screening of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes and included dermatomyositis as one of the signs.10 Patients should have a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Women should have a mammogram and a pelvis ultrasound. Men younger than 50 years should consider testes ultrasound, and patients older than 50 years should undergo usual colonoscopy screening.

The risk of malignancy is highest in the first year after diagnosis, but may extend to 5 years after the diagnosis, so repeat screening should be performed 3-6 months after diagnosis, followed with biannual testing for 4 years. If a malignancy is present, then treatment should be tailored to the neoplasm to improve symptoms of myositis; however, response is generally worse than it would be with dermatomyositis in the absence of malignancy. In the present case with bladder cancer, therapies may include platinum-based-chemotherapy, resection, and radiation. Dermatomyositis as a result of a bladder cancer paraneoplastic syndrome is associated with a poor prognosis as demonstrated in the case of this patient and others reported in the literature.11

Even though dermatomyositis is usually a chronic disease process, 87% of patients respond initially to corticosteroid treatment.12 Therefore, treatment should be escalated with an agent such as azathioprine or methotrexate, or, like in this case, an underlying malignancy should be suspected. This case emphasizes the importance of screening patients appropriately for malignancy in patients with an inflammatory myopathy and reveals the poor prognosis associated with this disease.

The clinical presentation of bladder cancer typically presents with hematuria; changes in voiding habits such as urgency, frequency, and pain; or less commonly, obstructive symptoms. Rarely does bladder cancer first present as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome with an inflammatory myopathy. Inflammatory myopathies such as dermatomyositis have been known to be associated with malignancy, however, in a meta-analysis by Yang and colleagues of 449 patients with dermatomyositis and malignancy there were only 8 cases reported of bladder cancer.1 Herein, we report a paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in the setting of a bladder cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 65-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension and alcohol use presented to the emergency department with worsening pain, stiffness in the neck, shoulders, and inability to lift his arms above his shoulders. During the physical exam, an erythematous purple rash was noted over his chest, neck, and arms. Upon further evaluation, his creatine phosphokinase was 3,500 U/L (reference range 52-336 U/L) suggesting muscle breakdown and possible inflammatory myopathy. A biopsy of the left deltoid and quadriceps muscles was performed and yielded a diagnosis of dermatomyositis. He was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily for his inflammatory myopathy. The patient also reported an unintentional weight loss of 20 lbs. and increasing weakness and inability to swallow, which caused aspiration events without developing pneumonia.

The patient’s symptoms worsened while he was on steroids, and we became concerned about the possibility of a primary malignancy, which led to further work-up. The results of a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed right-sided hydronephrosis and hydrourteter with an irregular, soft-tissue density mass of 4.7 x 3.2 x 4.2 cm along the posterior wall of the bladder (Figure 1).

A cystoscopy was performed with transurethral resection of a bladder tumor that was more than 8 cm in diameter. Because the mass was not fully resectable, only 25% of the tumor burden was removed. The pathology report revealed an invasive, high-grade urothelial cell carcinoma (Figure 2, see PDF). Further imaging ruled out metastatic spread. The patient was continued on steroids. He was not a candidate for neoadjuvant chemotherapy because of his comorbidities and cisplatin ineligibility owing to his significant bilateral hearing deficiencies. Members of a multidisciplinary tumor board decided to move forward with definitive surgery. The patient underwent a robotic-assisted laparoscoptic cystoprostatectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection and open ileal conduit urinary diversion. Staging of tumor was determined as pT3b N1 (1/30) M0, LVI+. After the surgery, the patient had resolution of his rash and significant improvement in his muscle weakness with the ability to raise his arms over his head and climb stairs. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not given since he was cisplatin ineligible as a result of his hearing loss. Active surveillance was preferred.

Four months after his cystoprostatectomy, he experienced new-onset hip pain and further imaging, including a bone scan, was performed. It showed metastatic disease in the ischium and iliac crest (Figure 3).

The patient decided to forgo any palliative chemotherapy and to have palliative radiation for pain and enroll in hospice. He died nine months after the initial diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma.

Discussion

Dermatomyositis is one of the inflammatory myopathies with a clinical presentation of proximal muscle weakness and characteristic skin findings of Gottron papules and heliotrope eruption. The most common subgroups of inflammatory myopathies are dermatomyositis, polymyositis, necrotizing autoimmune myopathy, and inclusion body myopathy. The pathogenesis of inflammatory myopathies is not well understood; however, some theories have been described, including: type 1 interferon signaling causing myofiber injury and antibody-complement mediated processes causing ischemia resulting in myofiber injury. 2,3 The diagnoses of inflammatory myopathies may be suggested based on history, physical examination findings, laboratory values showing muscle injury (creatine kinase, aldolase, ALT, AST, LDH), myositis-specific antibodies (antisynthetase autoantibodies), electromyogram, and magnetic-resonance imaging. However, muscle biopsy remains the gold standard.4

The initial treatment of inflammatory myopathies begins with glucocorticoid therapy at 0.5-1.0 mg/kg. This regimen may be titrated down over 6 weeks to a level adequate to control symptoms. Even while on glucocorticoid therapy, this patient’s symptoms continued, along with the development of dysphagia. Dysphagia is another notable symptom of dermatomyositis that may result in aspiration pneumonia with fatal outcomes.5,6,7 Not only did this patient initially respond poorly to corticosteroids, but the unintentional weight loss was another alarming feature prompting further evaluation. That led to the diagnosis of urothelial cell carcinoma, which was causing the paraneoplastic syndrome.

A paraneoplastic syndrome is a collection of symptoms that are observed in organ systems separate from the primary disease. This process is mostly caused by an autoimmune response to the tumor and nervous system.8 Inflammatory myopathies, such as dermatomyositis, have been shown to be associated with a variety of malignancies as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The most common cancers associated with dermatomyositis are ovarian, lung, pancreatic, stomach, colorectal, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.9 Although an association between dermatomyositis and bladder cancer has been established, very few cases have been reported in the literature. In the Yang meta-analysis, the relative risk of malignancy for patients with dermatomyositis was 5.5%, and of the 449 patients with dermatomyositis who had malignancy, only 8 cases of bladder cancer were reported.1

After a patient has been diagnosed with an inflammatory myopathy, there should be further evaluation for an underling malignancy causing a paraneoplastic process. The risk of these patients having a malignancy overall is 4.5 times higher than patients without dermatomyositis.1 Definite screening recommendations have not been established, but screening should be based on patient’s age, gender, and clinical scenario. The European Federation of Neurological Societies formed a task force to focus on malignancy screening of paraneoplastic neurological syndromes and included dermatomyositis as one of the signs.10 Patients should have a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Women should have a mammogram and a pelvis ultrasound. Men younger than 50 years should consider testes ultrasound, and patients older than 50 years should undergo usual colonoscopy screening.

The risk of malignancy is highest in the first year after diagnosis, but may extend to 5 years after the diagnosis, so repeat screening should be performed 3-6 months after diagnosis, followed with biannual testing for 4 years. If a malignancy is present, then treatment should be tailored to the neoplasm to improve symptoms of myositis; however, response is generally worse than it would be with dermatomyositis in the absence of malignancy. In the present case with bladder cancer, therapies may include platinum-based-chemotherapy, resection, and radiation. Dermatomyositis as a result of a bladder cancer paraneoplastic syndrome is associated with a poor prognosis as demonstrated in the case of this patient and others reported in the literature.11

Even though dermatomyositis is usually a chronic disease process, 87% of patients respond initially to corticosteroid treatment.12 Therefore, treatment should be escalated with an agent such as azathioprine or methotrexate, or, like in this case, an underlying malignancy should be suspected. This case emphasizes the importance of screening patients appropriately for malignancy in patients with an inflammatory myopathy and reveals the poor prognosis associated with this disease.

1. Yang Z, Lin F, Qin B, Liang Y, Zhong R. Polymyositis/dermatomyositis and malignancy risk: a metaanalysis study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(2):282-291.

2. Greenberg, SA. Dermatomyositis and type 1 interferons. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(3):198-203.

3. Dalakas, MC, Hohlfeld, R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362(9388):971-982.

4. Malik A, Hayat G, Kalia JS, Guzman MA. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: clinical approach and management. Front Neurol. 2016;7:64.

5. Sabio JM, Vargas-Hitos JA, Jiménez-Alonso J. Paraneoplastic dermatomyositis associated with bladder cancer. Lupus. 2006;15(9):619-620.

6. Mallon E, Osborne G, Dinneen M, Lane RJ, Glaser M, Bunker CB. Dermatomyositis in association with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24(2):94-96.

7. Hafejee A, Coulson IH. Dysphagia in dermatomyositis secondary to bladder cancer: rapid response to combined immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30(1):93-94.

8. Dalmau J, Gultekin HS, Posner JB. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes: pathogenesis and physiopathology. Brain Pathol. 1999;9(2):275-284.

9. Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigureirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357(9250):96-100.

10. Titulaer, MJ, Soffietti R, Dalmau J, et al. Screening for tumours in paraneoplastic syndromes: report of an EFNS Task Force. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(1):19-e3.

11. Xu R, Zhong Z, Jiang H, Zhang L, Zhao X. A rare paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in bladder cancer with fatal outcome. Urol J. 2013;10(1):815-817.

12. Troyanov Y, Targoff IN, Tremblay JL, Goulet JR, Raymond Y, Senecal JL. Novel classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies based on overlap syndrome features and autoantibodies: analysis of 100 French Canadian patients. Medicine (Baltimore), 2005;84(4):231-249.

1. Yang Z, Lin F, Qin B, Liang Y, Zhong R. Polymyositis/dermatomyositis and malignancy risk: a metaanalysis study. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(2):282-291.

2. Greenberg, SA. Dermatomyositis and type 1 interferons. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(3):198-203.

3. Dalakas, MC, Hohlfeld, R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362(9388):971-982.

4. Malik A, Hayat G, Kalia JS, Guzman MA. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: clinical approach and management. Front Neurol. 2016;7:64.

5. Sabio JM, Vargas-Hitos JA, Jiménez-Alonso J. Paraneoplastic dermatomyositis associated with bladder cancer. Lupus. 2006;15(9):619-620.

6. Mallon E, Osborne G, Dinneen M, Lane RJ, Glaser M, Bunker CB. Dermatomyositis in association with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24(2):94-96.

7. Hafejee A, Coulson IH. Dysphagia in dermatomyositis secondary to bladder cancer: rapid response to combined immunoglobulin and methylprednisolone. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30(1):93-94.

8. Dalmau J, Gultekin HS, Posner JB. Paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes: pathogenesis and physiopathology. Brain Pathol. 1999;9(2):275-284.

9. Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigureirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357(9250):96-100.

10. Titulaer, MJ, Soffietti R, Dalmau J, et al. Screening for tumours in paraneoplastic syndromes: report of an EFNS Task Force. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18(1):19-e3.

11. Xu R, Zhong Z, Jiang H, Zhang L, Zhao X. A rare paraneoplastic dermatomyositis in bladder cancer with fatal outcome. Urol J. 2013;10(1):815-817.

12. Troyanov Y, Targoff IN, Tremblay JL, Goulet JR, Raymond Y, Senecal JL. Novel classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies based on overlap syndrome features and autoantibodies: analysis of 100 French Canadian patients. Medicine (Baltimore), 2005;84(4):231-249.

World Trade Center responders face greater cancer burden, including greater risk of multiple myeloma

Rescue and recovery workers who were involved in the aftermath of the World Trade Center disaster may face a greater cancer burden than the general population, according to two studies published in JAMA Oncology.

In particular, they may be at risk of developing multiple myeloma at an earlier age.

The first study was a closed-cohort study of 14,474 employees of the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) who were exposed to the World Trade Center disaster but were cancer-free as of Jan. 1, 2012. The aim was to project cancer incidence from 2012 through 2031, based on data from the FDNY World Trade Center Health Program, and compare those rates with age-, race-, and sex-specific New York cancer rates from the general population.

The modeling projected a “modestly” higher number of cancer cases in the white male subgroup of rescue and recovery workers exposed to the World Trade Center (2,714 vs. 2,596 for the general population of New York; P less than .001). Specifically, the investigators projected significantly higher case counts of prostate cancer (1,437 vs. 863), thyroid cancer (73 vs. 57), and melanoma (201 vs. 131), compared with the general population in New York, but fewer lung (237 vs. 373), colorectal (172 vs. 267), and kidney cancers (66 vs. 132) (P less than .001 for all).

“Our findings suggest that the FDNY WTC-exposed cohort may experience a greater burden of cancer than would be expected from a population with similar demographic characteristics,” wrote Rachel Zeig-Owens, DrPH, from the Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, both in New York, and coauthors, highlighting prostate cancer as a particular concern.

However, they also acknowledged that the elevated rates observed in people exposed to the World Trade Center disaster could be a result of increased surveillance, even though they did attempt to correct for that, and that firefighters in general might face higher risks.

“It is possible that firefighters have a higher risk of cancer than the general population owing to exposures associated with the occupation,” they wrote. However occupation could also have the opposite effect, as rescue and recovery workers tend to have lower smoking rates, which may explain the relatively low rates of certain cancers such as lung cancer, they said.

A second study examined the effect of the World Trade Center disaster on the risk of multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathies in exposed firefighters.

The seroprevalence study of monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance (MGUS) in 781 exposed firefighters revealed that the age-standardized prevalence of these was 76% higher in this population than it was in a white male reference population living in Minnesota.

In particular, the age-standardized prevalence of light-chain MGUS was more than threefold higher in exposed firefighters, compared with the reference population.

Researchers also analyzed a case series of 16 exposed white male firefighters who received a diagnosis of multiple myeloma after Sept. 11, 2001. Of the 14 patients for whom data on the monoclonal protein isotype was available, half had light-chain multiple myeloma.

“These findings are of interest due to previously observed associations between light-chain multiple myeloma and light-chain MGUS and exposure to toxins, and chronic immune stimulation,” wrote Ola Landgren, MD, PhD, from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and his coauthors.

Seven patients were also assessed for CD20 expression – a marker of poorer prognosis – and 71% were found to be CD20-positive, a prevalence around 3.5-fold higher than that seen in the general population.

The cohort with multiple myeloma was diagnosed on average 12 years younger than those in the general population. The authors commented that this was unlikely to be caused by lead-time bias because the time from first symptoms to clinical manifestation of the disease is usually around 1 year.

“Taken together, our results show that environmental exposure due to the WTC attacks is associated with myeloma precursor disease (MGUS and light-chain MGUS) and may be a risk factor for the development of multiple myeloma at an earlier age, particularly the light-chain subtype,” the authors wrote.

The first study was supported by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health; no conflicts of interest were declared.

The second study was supported by the V Foundation for Cancer Research, the Byrne Fund for the benefit of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the National Cancer Institute, the Albert Einstein Cancer Center, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; no conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Zeig-Owens R et al. JAMA Oncology. 2018 April 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0504. Landgren O et al. JAMA Oncology. 2018 April 16. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0509.

When the heroes of the World Trade Center are diagnosed with even a common cancer, there is a natural tendency to assume that the diagnosis is the result of their service during the disaster. However, it is important to appreciate that the firefighting profession is known to be associated with higher risks of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and multiple myelomas, compared with the general population.

Given that, it would have been preferable to compare the World Trade Center–exposed populations with an equally intensively screened, age-matched cohort of firefighters from another major city.

If we apply Sir Richard Doll’s rule that a single epidemiologic study cannot be persuasive until the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval is greater than three, the relative risks in the study by Landgren and colleagues are too small to be persuasive.

The predicted increases in cancers of the prostate, thyroid, and myeloma are interesting, but these have also been previously reported in firefighters from other cities.

Despite this, we owe it to these men and women to find the truth and determine the illnesses that are associated with their service.

Otis W. Brawley, MD, is chief medical and scientific officer and executive vice president of the American Cancer Society and a professor at Emory University, Atlanta. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Oncology. 2018 April 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0498.) No conflicts of interest were declared.

When the heroes of the World Trade Center are diagnosed with even a common cancer, there is a natural tendency to assume that the diagnosis is the result of their service during the disaster. However, it is important to appreciate that the firefighting profession is known to be associated with higher risks of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and multiple myelomas, compared with the general population.

Given that, it would have been preferable to compare the World Trade Center–exposed populations with an equally intensively screened, age-matched cohort of firefighters from another major city.

If we apply Sir Richard Doll’s rule that a single epidemiologic study cannot be persuasive until the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval is greater than three, the relative risks in the study by Landgren and colleagues are too small to be persuasive.

The predicted increases in cancers of the prostate, thyroid, and myeloma are interesting, but these have also been previously reported in firefighters from other cities.

Despite this, we owe it to these men and women to find the truth and determine the illnesses that are associated with their service.

Otis W. Brawley, MD, is chief medical and scientific officer and executive vice president of the American Cancer Society and a professor at Emory University, Atlanta. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Oncology. 2018 April 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0498.) No conflicts of interest were declared.

When the heroes of the World Trade Center are diagnosed with even a common cancer, there is a natural tendency to assume that the diagnosis is the result of their service during the disaster. However, it is important to appreciate that the firefighting profession is known to be associated with higher risks of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and multiple myelomas, compared with the general population.

Given that, it would have been preferable to compare the World Trade Center–exposed populations with an equally intensively screened, age-matched cohort of firefighters from another major city.

If we apply Sir Richard Doll’s rule that a single epidemiologic study cannot be persuasive until the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval is greater than three, the relative risks in the study by Landgren and colleagues are too small to be persuasive.

The predicted increases in cancers of the prostate, thyroid, and myeloma are interesting, but these have also been previously reported in firefighters from other cities.

Despite this, we owe it to these men and women to find the truth and determine the illnesses that are associated with their service.

Otis W. Brawley, MD, is chief medical and scientific officer and executive vice president of the American Cancer Society and a professor at Emory University, Atlanta. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Oncology. 2018 April 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0498.) No conflicts of interest were declared.

Rescue and recovery workers who were involved in the aftermath of the World Trade Center disaster may face a greater cancer burden than the general population, according to two studies published in JAMA Oncology.

In particular, they may be at risk of developing multiple myeloma at an earlier age.

The first study was a closed-cohort study of 14,474 employees of the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) who were exposed to the World Trade Center disaster but were cancer-free as of Jan. 1, 2012. The aim was to project cancer incidence from 2012 through 2031, based on data from the FDNY World Trade Center Health Program, and compare those rates with age-, race-, and sex-specific New York cancer rates from the general population.

The modeling projected a “modestly” higher number of cancer cases in the white male subgroup of rescue and recovery workers exposed to the World Trade Center (2,714 vs. 2,596 for the general population of New York; P less than .001). Specifically, the investigators projected significantly higher case counts of prostate cancer (1,437 vs. 863), thyroid cancer (73 vs. 57), and melanoma (201 vs. 131), compared with the general population in New York, but fewer lung (237 vs. 373), colorectal (172 vs. 267), and kidney cancers (66 vs. 132) (P less than .001 for all).

“Our findings suggest that the FDNY WTC-exposed cohort may experience a greater burden of cancer than would be expected from a population with similar demographic characteristics,” wrote Rachel Zeig-Owens, DrPH, from the Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, both in New York, and coauthors, highlighting prostate cancer as a particular concern.

However, they also acknowledged that the elevated rates observed in people exposed to the World Trade Center disaster could be a result of increased surveillance, even though they did attempt to correct for that, and that firefighters in general might face higher risks.

“It is possible that firefighters have a higher risk of cancer than the general population owing to exposures associated with the occupation,” they wrote. However occupation could also have the opposite effect, as rescue and recovery workers tend to have lower smoking rates, which may explain the relatively low rates of certain cancers such as lung cancer, they said.

A second study examined the effect of the World Trade Center disaster on the risk of multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathies in exposed firefighters.

The seroprevalence study of monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance (MGUS) in 781 exposed firefighters revealed that the age-standardized prevalence of these was 76% higher in this population than it was in a white male reference population living in Minnesota.

In particular, the age-standardized prevalence of light-chain MGUS was more than threefold higher in exposed firefighters, compared with the reference population.

Researchers also analyzed a case series of 16 exposed white male firefighters who received a diagnosis of multiple myeloma after Sept. 11, 2001. Of the 14 patients for whom data on the monoclonal protein isotype was available, half had light-chain multiple myeloma.

“These findings are of interest due to previously observed associations between light-chain multiple myeloma and light-chain MGUS and exposure to toxins, and chronic immune stimulation,” wrote Ola Landgren, MD, PhD, from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and his coauthors.

Seven patients were also assessed for CD20 expression – a marker of poorer prognosis – and 71% were found to be CD20-positive, a prevalence around 3.5-fold higher than that seen in the general population.

The cohort with multiple myeloma was diagnosed on average 12 years younger than those in the general population. The authors commented that this was unlikely to be caused by lead-time bias because the time from first symptoms to clinical manifestation of the disease is usually around 1 year.

“Taken together, our results show that environmental exposure due to the WTC attacks is associated with myeloma precursor disease (MGUS and light-chain MGUS) and may be a risk factor for the development of multiple myeloma at an earlier age, particularly the light-chain subtype,” the authors wrote.

The first study was supported by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health; no conflicts of interest were declared.

The second study was supported by the V Foundation for Cancer Research, the Byrne Fund for the benefit of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the National Cancer Institute, the Albert Einstein Cancer Center, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; no conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Zeig-Owens R et al. JAMA Oncology. 2018 April 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0504. Landgren O et al. JAMA Oncology. 2018 April 16. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0509.

Rescue and recovery workers who were involved in the aftermath of the World Trade Center disaster may face a greater cancer burden than the general population, according to two studies published in JAMA Oncology.

In particular, they may be at risk of developing multiple myeloma at an earlier age.

The first study was a closed-cohort study of 14,474 employees of the Fire Department of the City of New York (FDNY) who were exposed to the World Trade Center disaster but were cancer-free as of Jan. 1, 2012. The aim was to project cancer incidence from 2012 through 2031, based on data from the FDNY World Trade Center Health Program, and compare those rates with age-, race-, and sex-specific New York cancer rates from the general population.

The modeling projected a “modestly” higher number of cancer cases in the white male subgroup of rescue and recovery workers exposed to the World Trade Center (2,714 vs. 2,596 for the general population of New York; P less than .001). Specifically, the investigators projected significantly higher case counts of prostate cancer (1,437 vs. 863), thyroid cancer (73 vs. 57), and melanoma (201 vs. 131), compared with the general population in New York, but fewer lung (237 vs. 373), colorectal (172 vs. 267), and kidney cancers (66 vs. 132) (P less than .001 for all).

“Our findings suggest that the FDNY WTC-exposed cohort may experience a greater burden of cancer than would be expected from a population with similar demographic characteristics,” wrote Rachel Zeig-Owens, DrPH, from the Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, both in New York, and coauthors, highlighting prostate cancer as a particular concern.

However, they also acknowledged that the elevated rates observed in people exposed to the World Trade Center disaster could be a result of increased surveillance, even though they did attempt to correct for that, and that firefighters in general might face higher risks.

“It is possible that firefighters have a higher risk of cancer than the general population owing to exposures associated with the occupation,” they wrote. However occupation could also have the opposite effect, as rescue and recovery workers tend to have lower smoking rates, which may explain the relatively low rates of certain cancers such as lung cancer, they said.

A second study examined the effect of the World Trade Center disaster on the risk of multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathies in exposed firefighters.

The seroprevalence study of monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance (MGUS) in 781 exposed firefighters revealed that the age-standardized prevalence of these was 76% higher in this population than it was in a white male reference population living in Minnesota.

In particular, the age-standardized prevalence of light-chain MGUS was more than threefold higher in exposed firefighters, compared with the reference population.

Researchers also analyzed a case series of 16 exposed white male firefighters who received a diagnosis of multiple myeloma after Sept. 11, 2001. Of the 14 patients for whom data on the monoclonal protein isotype was available, half had light-chain multiple myeloma.

“These findings are of interest due to previously observed associations between light-chain multiple myeloma and light-chain MGUS and exposure to toxins, and chronic immune stimulation,” wrote Ola Landgren, MD, PhD, from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and his coauthors.

Seven patients were also assessed for CD20 expression – a marker of poorer prognosis – and 71% were found to be CD20-positive, a prevalence around 3.5-fold higher than that seen in the general population.

The cohort with multiple myeloma was diagnosed on average 12 years younger than those in the general population. The authors commented that this was unlikely to be caused by lead-time bias because the time from first symptoms to clinical manifestation of the disease is usually around 1 year.

“Taken together, our results show that environmental exposure due to the WTC attacks is associated with myeloma precursor disease (MGUS and light-chain MGUS) and may be a risk factor for the development of multiple myeloma at an earlier age, particularly the light-chain subtype,” the authors wrote.

The first study was supported by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health; no conflicts of interest were declared.

The second study was supported by the V Foundation for Cancer Research, the Byrne Fund for the benefit of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the National Cancer Institute, the Albert Einstein Cancer Center, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; no conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Zeig-Owens R et al. JAMA Oncology. 2018 April 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0504. Landgren O et al. JAMA Oncology. 2018 April 16. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0509.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Monoclonal gammopathies and multiple myeloma may occur more often and earlier in World Trade Center rescue workers.

Major finding: Prevalence of light-chain monoclonal gammopathies is threefold higher in exposed firefighters than in a reference population of white males.

Study details: A cohort study in 14,474 employees of the Fire Department of the City of New York exposed to the Sept. 11, 2001, World Trade Center disaster, a case series of 16 exposed white male firefighters diagnosed with multiple myeloma, and a seroprevalence study of monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance in 781 exposed firefighters.

Disclosures: The first study was supported by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health; no conflicts of interest were declared. The second study was supported by the V Foundation for Cancer Research, the Byrne Fund for the benefit of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the National Cancer Institute, the Albert Einstein Cancer Center, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; no conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Zeig-Owens R et al. JAMA Oncology 2018, Apr 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0504. Landgren O et al. JAMA Oncology 2018, Apr 26. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0509.

Company discontinues phase 3 ADAPT for mRCC

A second interim analysis of

In ADAPT, 462 patients with previously untreated advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) were randomized 2:1 between combination treatment with Rocapuldencel-T and sunitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy, after undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy.

In February 2017, the trial’s Independent Data Monitoring Committee had reviewed the data and concluded that the trial was unlikely to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in median overall survival in the combination arm and recommended halting the trial. However, the principal investigators and the company, Argos Therapeutics, considered the data too immature to observe the delayed effects associated with immunotherapy and decided to continue the trial. They submitted a protocol amendment to the Food and Drug Administration adding additional co-primary endpoints, and in April of last year, met with the Food and Drug Administration, which accepted the amendment and agreed to continuation of the trial, according to a company press release issued in November.

In the latest interim analysis, which was conducted following an additional 51 deaths, median overall survival for the intent-to-treat patient population was 28.2 months for the combination arm (95% confidence interval, 23.4, 35.2) compared with 31.2 months (95% CI, 23.0, 44.5) for the control arm; this was one of four new co-primary endpoints. The hazard ratio was 1.10 (95% CI, 0.85, 1.42).

Other co-primary endpoints that were evaluated, including overall survival for the patients who remained alive at the time of the February 2017 interim analysis and overall survival for all patients for whom at least 12 months of follow-up was available, did not demonstrate a favorable result, Argos Therapeutics said in a recent press release.

Rocapuldencel-T “consists of autologous dendritic cells programmed with amplified RNA from a patient’s primary tumor” and is “designed to overcome immunosuppression and induce broadly reactive, long-lasting anti-tumor memory T cells” according to the early interim analysis presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) 2017. The drug is also being evaluated in non–small cell lung cancer and bladder cancer.

A second interim analysis of

In ADAPT, 462 patients with previously untreated advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) were randomized 2:1 between combination treatment with Rocapuldencel-T and sunitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy, after undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy.

In February 2017, the trial’s Independent Data Monitoring Committee had reviewed the data and concluded that the trial was unlikely to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in median overall survival in the combination arm and recommended halting the trial. However, the principal investigators and the company, Argos Therapeutics, considered the data too immature to observe the delayed effects associated with immunotherapy and decided to continue the trial. They submitted a protocol amendment to the Food and Drug Administration adding additional co-primary endpoints, and in April of last year, met with the Food and Drug Administration, which accepted the amendment and agreed to continuation of the trial, according to a company press release issued in November.

In the latest interim analysis, which was conducted following an additional 51 deaths, median overall survival for the intent-to-treat patient population was 28.2 months for the combination arm (95% confidence interval, 23.4, 35.2) compared with 31.2 months (95% CI, 23.0, 44.5) for the control arm; this was one of four new co-primary endpoints. The hazard ratio was 1.10 (95% CI, 0.85, 1.42).

Other co-primary endpoints that were evaluated, including overall survival for the patients who remained alive at the time of the February 2017 interim analysis and overall survival for all patients for whom at least 12 months of follow-up was available, did not demonstrate a favorable result, Argos Therapeutics said in a recent press release.

Rocapuldencel-T “consists of autologous dendritic cells programmed with amplified RNA from a patient’s primary tumor” and is “designed to overcome immunosuppression and induce broadly reactive, long-lasting anti-tumor memory T cells” according to the early interim analysis presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) 2017. The drug is also being evaluated in non–small cell lung cancer and bladder cancer.

A second interim analysis of