User login

VIDEO: Novel and other therapies for vaginal dryness

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Menopausal women who experience vaginal dryness often find the resultant pain of sexual intercourse so prohibitive that, according to Dr. JoAnne Pinkerton, often these women go months or years without intimate relations.

There are many treatment options that can benefit patients with the condition, explained Dr. Pinkerton, medical director of the Midlife Health Center at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, but physicians aren’t always aware of what’s available.

In a video interview at annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Pinkerton discussed the range of therapies physicians can offer menopausal patients with vaginal dryness.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Menopausal women who experience vaginal dryness often find the resultant pain of sexual intercourse so prohibitive that, according to Dr. JoAnne Pinkerton, often these women go months or years without intimate relations.

There are many treatment options that can benefit patients with the condition, explained Dr. Pinkerton, medical director of the Midlife Health Center at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, but physicians aren’t always aware of what’s available.

In a video interview at annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Pinkerton discussed the range of therapies physicians can offer menopausal patients with vaginal dryness.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Menopausal women who experience vaginal dryness often find the resultant pain of sexual intercourse so prohibitive that, according to Dr. JoAnne Pinkerton, often these women go months or years without intimate relations.

There are many treatment options that can benefit patients with the condition, explained Dr. Pinkerton, medical director of the Midlife Health Center at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, but physicians aren’t always aware of what’s available.

In a video interview at annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Pinkerton discussed the range of therapies physicians can offer menopausal patients with vaginal dryness.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NAMS 2014 ANNUAL MEETING

Adnexal masses in pregnancy

With the increasing use of ultrasound in the first trimester, asymptomatic adnexal masses are being diagnosed earlier in pregnancy, leaving providers with an often difficult clinical scenario. The reported incidence of adnexal masses ranges from 1 in 81 to 1 in 8,000 pregnancies, and 0.93%-6% of these are malignant (Gynecol. Oncol. 2006;101:315-21; Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;181:19-24). In light of this, the importance of recognizing adnexal masses and knowledge of their management are crucial for any practicing obstetrician gynecologist.

Differential diagnosis

In pregnancy, the majority of adnexal masses are benign simple cysts less than 5 cm (BJOG 2003;110:578-83). As such, the majority of masses (probable corpus luteum cysts) detected in the first trimester (70% in one study) will resolve by the early part of the second trimester (Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;49:492-505). Adnexal masses are commonly physiologic or functional cysts. Benign masses with complex features can include corpus luteum, mature teratomas, hydrosalpinx, theca lutein cysts, or endometriomas. Complex adnexal masses greater than 5 cm are most likely mature teratomas (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;184:1504-12). Degenerating or pedunculated fibroids can mimic an adnexal mass and may cause pain, clouding the diagnosis.

Of the rare malignant lesions that occur in pregnancy, approximately half are epithelial tumors and one-third are germ cell tumors. Of the epithelial neoplasms, up to 50% may be low-malignant-potential tumors.

Diagnostic evaluation

Imaging: Transvaginal ultrasound is regarded as the modality of choice when evaluating adnexal pathology. Abdominal ultrasound may be especially helpful when the ovaries are outside of the pelvis, especially later in gestation. MRI without contrast may aid in distinguishing leiomyoma and ovarian pathology, which is vital when planning surgery. However, MRI with gadolinium is not recommended as its safety in pregnancy has not been established.

Tumor markers: None of the available tumor markers may be reliably used to diagnose ovarian cancer in pregnancy. CA-125 is elevated in epithelial ovarian cancer, but it is also elevated in pregnancy. However, significant elevations (greater than 1,000 U/mL) are more likely to be associated with cancer.

Markers for germ cell tumors include alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Maternal serum levels of AFP (MSAFP) normally rise in pregnancy, although extreme values (less than 500 ng/mL) are associated with neural tube defects while levels greater than 1,000 ng/mL may be associated with an ovarian germ cell tumor (especially when greater than 10,000 ng/mL). LDH is elevated in women with ovarian dysgerminomas and is reliable in pregnancy outside of HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets). Of course, hCG is elevated in pregnancy, negating its value as a germ cell tumor marker. Inhibin B may be elevated in association with granulosa cell tumors; however, it is also elevated in early gestation.

Management

Because most corpus luteum will resolve, it is recommended to electively resect adnexal masses in the second trimester when they meet the following criteria: lesions are greater than 10 cm in diameter; they are complex lesions (Fertil. Steril. 2009;91:1895-902; Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;93:585-9).

Benign-appearing but persistent simple cysts in the second trimester may be managed conservatively, as approximately 70% will resolve. Thus, routine removal of persistent cysts is not recommended (BJOG 2003;110:578-83). Risk factors for persistent lesions include size greater than 5 cm and complex morphology (Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;93:585-9).Providers may consider serial ultrasounds of ovarian cysts to detect an increase in size or change in character that may warrant further investigation.

Surgery is considered in asymptomatic women meeting the above criteria, to diagnose malignancy or reduce the risk of torsion or rupture. Torsion has been found to be more likely in the late first and early second trimester, with only 6% occurring after 20 weeks. Corpus luteum cysts may on occasion persist into the second trimester and can account for up to 17% of all cystic adnexal masses (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;181:19-24). It is important to remember that if a corpus luteum is surgically resected in the first trimester, progesterone needs to be replaced to avoid pregnancy loss. Of those complex lesions diagnosed in the first trimester that persist into the second trimester, up to 10% may be malignant.

Providers who feel comfortable with laparoscopic techniques can proceed with minimally invasive surgery, with optimal timing in the early second trimester (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:720-5). Care should be taken to consider fundal height when choosing trocar placement. If there is a high suspicion for malignancy, providers may want to proceed via laparotomy, which should be via a vertical midline incision. Tocolytic therapy given prophylactically at the time of surgery has no proven benefit and should not be routinely administered.

Washings should be obtained and providers should perform a thorough inspection of the abdomen, contralateral ovary, omentum, and peritoneal surfaces. Any suspicious lesions should be biopsied. A simple cystectomy is reasonable with benign lesions; however, a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed with frozen confirmation if there are any concerning findings for malignancy. If a malignancy is confirmed, a gynecologic oncologist should be consulted, and surgical staging should be considered.

Dr. Sullivan is a chief resident in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. Dr. Clarke-Pearson is the chair and the Robert A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. Dr. Sullivan, Dr. Gehrig, and Dr. Clarke-Pearson said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

With the increasing use of ultrasound in the first trimester, asymptomatic adnexal masses are being diagnosed earlier in pregnancy, leaving providers with an often difficult clinical scenario. The reported incidence of adnexal masses ranges from 1 in 81 to 1 in 8,000 pregnancies, and 0.93%-6% of these are malignant (Gynecol. Oncol. 2006;101:315-21; Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;181:19-24). In light of this, the importance of recognizing adnexal masses and knowledge of their management are crucial for any practicing obstetrician gynecologist.

Differential diagnosis

In pregnancy, the majority of adnexal masses are benign simple cysts less than 5 cm (BJOG 2003;110:578-83). As such, the majority of masses (probable corpus luteum cysts) detected in the first trimester (70% in one study) will resolve by the early part of the second trimester (Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;49:492-505). Adnexal masses are commonly physiologic or functional cysts. Benign masses with complex features can include corpus luteum, mature teratomas, hydrosalpinx, theca lutein cysts, or endometriomas. Complex adnexal masses greater than 5 cm are most likely mature teratomas (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;184:1504-12). Degenerating or pedunculated fibroids can mimic an adnexal mass and may cause pain, clouding the diagnosis.

Of the rare malignant lesions that occur in pregnancy, approximately half are epithelial tumors and one-third are germ cell tumors. Of the epithelial neoplasms, up to 50% may be low-malignant-potential tumors.

Diagnostic evaluation

Imaging: Transvaginal ultrasound is regarded as the modality of choice when evaluating adnexal pathology. Abdominal ultrasound may be especially helpful when the ovaries are outside of the pelvis, especially later in gestation. MRI without contrast may aid in distinguishing leiomyoma and ovarian pathology, which is vital when planning surgery. However, MRI with gadolinium is not recommended as its safety in pregnancy has not been established.

Tumor markers: None of the available tumor markers may be reliably used to diagnose ovarian cancer in pregnancy. CA-125 is elevated in epithelial ovarian cancer, but it is also elevated in pregnancy. However, significant elevations (greater than 1,000 U/mL) are more likely to be associated with cancer.

Markers for germ cell tumors include alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Maternal serum levels of AFP (MSAFP) normally rise in pregnancy, although extreme values (less than 500 ng/mL) are associated with neural tube defects while levels greater than 1,000 ng/mL may be associated with an ovarian germ cell tumor (especially when greater than 10,000 ng/mL). LDH is elevated in women with ovarian dysgerminomas and is reliable in pregnancy outside of HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets). Of course, hCG is elevated in pregnancy, negating its value as a germ cell tumor marker. Inhibin B may be elevated in association with granulosa cell tumors; however, it is also elevated in early gestation.

Management

Because most corpus luteum will resolve, it is recommended to electively resect adnexal masses in the second trimester when they meet the following criteria: lesions are greater than 10 cm in diameter; they are complex lesions (Fertil. Steril. 2009;91:1895-902; Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;93:585-9).

Benign-appearing but persistent simple cysts in the second trimester may be managed conservatively, as approximately 70% will resolve. Thus, routine removal of persistent cysts is not recommended (BJOG 2003;110:578-83). Risk factors for persistent lesions include size greater than 5 cm and complex morphology (Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;93:585-9).Providers may consider serial ultrasounds of ovarian cysts to detect an increase in size or change in character that may warrant further investigation.

Surgery is considered in asymptomatic women meeting the above criteria, to diagnose malignancy or reduce the risk of torsion or rupture. Torsion has been found to be more likely in the late first and early second trimester, with only 6% occurring after 20 weeks. Corpus luteum cysts may on occasion persist into the second trimester and can account for up to 17% of all cystic adnexal masses (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;181:19-24). It is important to remember that if a corpus luteum is surgically resected in the first trimester, progesterone needs to be replaced to avoid pregnancy loss. Of those complex lesions diagnosed in the first trimester that persist into the second trimester, up to 10% may be malignant.

Providers who feel comfortable with laparoscopic techniques can proceed with minimally invasive surgery, with optimal timing in the early second trimester (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:720-5). Care should be taken to consider fundal height when choosing trocar placement. If there is a high suspicion for malignancy, providers may want to proceed via laparotomy, which should be via a vertical midline incision. Tocolytic therapy given prophylactically at the time of surgery has no proven benefit and should not be routinely administered.

Washings should be obtained and providers should perform a thorough inspection of the abdomen, contralateral ovary, omentum, and peritoneal surfaces. Any suspicious lesions should be biopsied. A simple cystectomy is reasonable with benign lesions; however, a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed with frozen confirmation if there are any concerning findings for malignancy. If a malignancy is confirmed, a gynecologic oncologist should be consulted, and surgical staging should be considered.

Dr. Sullivan is a chief resident in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. Dr. Clarke-Pearson is the chair and the Robert A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. Dr. Sullivan, Dr. Gehrig, and Dr. Clarke-Pearson said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

With the increasing use of ultrasound in the first trimester, asymptomatic adnexal masses are being diagnosed earlier in pregnancy, leaving providers with an often difficult clinical scenario. The reported incidence of adnexal masses ranges from 1 in 81 to 1 in 8,000 pregnancies, and 0.93%-6% of these are malignant (Gynecol. Oncol. 2006;101:315-21; Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;181:19-24). In light of this, the importance of recognizing adnexal masses and knowledge of their management are crucial for any practicing obstetrician gynecologist.

Differential diagnosis

In pregnancy, the majority of adnexal masses are benign simple cysts less than 5 cm (BJOG 2003;110:578-83). As such, the majority of masses (probable corpus luteum cysts) detected in the first trimester (70% in one study) will resolve by the early part of the second trimester (Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;49:492-505). Adnexal masses are commonly physiologic or functional cysts. Benign masses with complex features can include corpus luteum, mature teratomas, hydrosalpinx, theca lutein cysts, or endometriomas. Complex adnexal masses greater than 5 cm are most likely mature teratomas (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;184:1504-12). Degenerating or pedunculated fibroids can mimic an adnexal mass and may cause pain, clouding the diagnosis.

Of the rare malignant lesions that occur in pregnancy, approximately half are epithelial tumors and one-third are germ cell tumors. Of the epithelial neoplasms, up to 50% may be low-malignant-potential tumors.

Diagnostic evaluation

Imaging: Transvaginal ultrasound is regarded as the modality of choice when evaluating adnexal pathology. Abdominal ultrasound may be especially helpful when the ovaries are outside of the pelvis, especially later in gestation. MRI without contrast may aid in distinguishing leiomyoma and ovarian pathology, which is vital when planning surgery. However, MRI with gadolinium is not recommended as its safety in pregnancy has not been established.

Tumor markers: None of the available tumor markers may be reliably used to diagnose ovarian cancer in pregnancy. CA-125 is elevated in epithelial ovarian cancer, but it is also elevated in pregnancy. However, significant elevations (greater than 1,000 U/mL) are more likely to be associated with cancer.

Markers for germ cell tumors include alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Maternal serum levels of AFP (MSAFP) normally rise in pregnancy, although extreme values (less than 500 ng/mL) are associated with neural tube defects while levels greater than 1,000 ng/mL may be associated with an ovarian germ cell tumor (especially when greater than 10,000 ng/mL). LDH is elevated in women with ovarian dysgerminomas and is reliable in pregnancy outside of HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets). Of course, hCG is elevated in pregnancy, negating its value as a germ cell tumor marker. Inhibin B may be elevated in association with granulosa cell tumors; however, it is also elevated in early gestation.

Management

Because most corpus luteum will resolve, it is recommended to electively resect adnexal masses in the second trimester when they meet the following criteria: lesions are greater than 10 cm in diameter; they are complex lesions (Fertil. Steril. 2009;91:1895-902; Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;93:585-9).

Benign-appearing but persistent simple cysts in the second trimester may be managed conservatively, as approximately 70% will resolve. Thus, routine removal of persistent cysts is not recommended (BJOG 2003;110:578-83). Risk factors for persistent lesions include size greater than 5 cm and complex morphology (Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;93:585-9).Providers may consider serial ultrasounds of ovarian cysts to detect an increase in size or change in character that may warrant further investigation.

Surgery is considered in asymptomatic women meeting the above criteria, to diagnose malignancy or reduce the risk of torsion or rupture. Torsion has been found to be more likely in the late first and early second trimester, with only 6% occurring after 20 weeks. Corpus luteum cysts may on occasion persist into the second trimester and can account for up to 17% of all cystic adnexal masses (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999;181:19-24). It is important to remember that if a corpus luteum is surgically resected in the first trimester, progesterone needs to be replaced to avoid pregnancy loss. Of those complex lesions diagnosed in the first trimester that persist into the second trimester, up to 10% may be malignant.

Providers who feel comfortable with laparoscopic techniques can proceed with minimally invasive surgery, with optimal timing in the early second trimester (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:720-5). Care should be taken to consider fundal height when choosing trocar placement. If there is a high suspicion for malignancy, providers may want to proceed via laparotomy, which should be via a vertical midline incision. Tocolytic therapy given prophylactically at the time of surgery has no proven benefit and should not be routinely administered.

Washings should be obtained and providers should perform a thorough inspection of the abdomen, contralateral ovary, omentum, and peritoneal surfaces. Any suspicious lesions should be biopsied. A simple cystectomy is reasonable with benign lesions; however, a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed with frozen confirmation if there are any concerning findings for malignancy. If a malignancy is confirmed, a gynecologic oncologist should be consulted, and surgical staging should be considered.

Dr. Sullivan is a chief resident in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. Dr. Clarke-Pearson is the chair and the Robert A. Ross Distinguished Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. Dr. Sullivan, Dr. Gehrig, and Dr. Clarke-Pearson said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

How useful is random biopsy when no colposcopic lesions are seen?

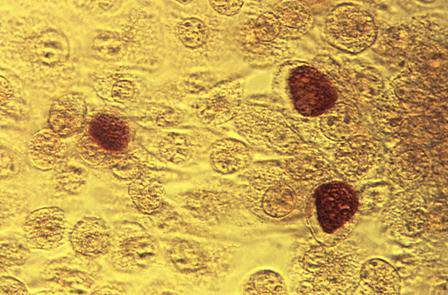

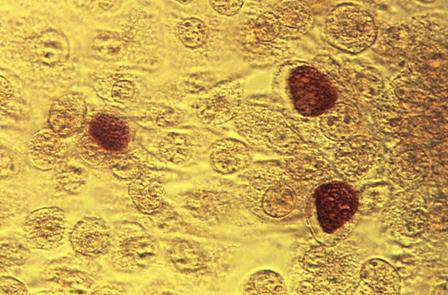

When performing colposcopy for abnormal cytology results or high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), clinicians often are faced with an absence of visible lesions. This situation raises the following question in his or her mind: “Should I perform a random biopsy?”

Details of the study

In a multicenter US study of more than 47,000 women, performed to assess HPV diagnostics between May 2008 and August 2009, colposcopy was performed in nonpregnant women aged 25 or older with an intact uterus due to atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or greater cytology results or high-risk HPV. The study participants and the colposcopists were blinded to the test results. In women with satisfactory colposcopy results but in whom no colposcopic lesions were noted, one random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction was performed.

Among 2,796 women (mean age, 39.5 years) with a random biopsy performed, the findings were: normal, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)−1, CIN2, and CIN3 in 90.0%, 5.7%, 1.3%, and 1.4%, respectively. Among all participants aged 25 and older, random biopsies accounted for 20.9% and 18.9% of the CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse cases, respectively. Among women positive for HPV 16 or 18, the likelihood of the random biopsy detecting CIN2 or worse was 24.7% and 8.6% for those with abnormal cytology or normal cytology, respectively.

What this evidence means for your practice

Consistent with other reports, the results of this post hoc analysis underscore the limitations of colposcopy. Just as results of a prior study indicated that taking two or more biopsies increases diagnostic yield,1 this large study points out the substantial benefit gained from performing a random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction when no colposcopic lesions are identified.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al; SCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):264–272.

When performing colposcopy for abnormal cytology results or high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), clinicians often are faced with an absence of visible lesions. This situation raises the following question in his or her mind: “Should I perform a random biopsy?”

Details of the study

In a multicenter US study of more than 47,000 women, performed to assess HPV diagnostics between May 2008 and August 2009, colposcopy was performed in nonpregnant women aged 25 or older with an intact uterus due to atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or greater cytology results or high-risk HPV. The study participants and the colposcopists were blinded to the test results. In women with satisfactory colposcopy results but in whom no colposcopic lesions were noted, one random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction was performed.

Among 2,796 women (mean age, 39.5 years) with a random biopsy performed, the findings were: normal, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)−1, CIN2, and CIN3 in 90.0%, 5.7%, 1.3%, and 1.4%, respectively. Among all participants aged 25 and older, random biopsies accounted for 20.9% and 18.9% of the CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse cases, respectively. Among women positive for HPV 16 or 18, the likelihood of the random biopsy detecting CIN2 or worse was 24.7% and 8.6% for those with abnormal cytology or normal cytology, respectively.

What this evidence means for your practice

Consistent with other reports, the results of this post hoc analysis underscore the limitations of colposcopy. Just as results of a prior study indicated that taking two or more biopsies increases diagnostic yield,1 this large study points out the substantial benefit gained from performing a random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction when no colposcopic lesions are identified.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

When performing colposcopy for abnormal cytology results or high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV), clinicians often are faced with an absence of visible lesions. This situation raises the following question in his or her mind: “Should I perform a random biopsy?”

Details of the study

In a multicenter US study of more than 47,000 women, performed to assess HPV diagnostics between May 2008 and August 2009, colposcopy was performed in nonpregnant women aged 25 or older with an intact uterus due to atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or greater cytology results or high-risk HPV. The study participants and the colposcopists were blinded to the test results. In women with satisfactory colposcopy results but in whom no colposcopic lesions were noted, one random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction was performed.

Among 2,796 women (mean age, 39.5 years) with a random biopsy performed, the findings were: normal, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)−1, CIN2, and CIN3 in 90.0%, 5.7%, 1.3%, and 1.4%, respectively. Among all participants aged 25 and older, random biopsies accounted for 20.9% and 18.9% of the CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse cases, respectively. Among women positive for HPV 16 or 18, the likelihood of the random biopsy detecting CIN2 or worse was 24.7% and 8.6% for those with abnormal cytology or normal cytology, respectively.

What this evidence means for your practice

Consistent with other reports, the results of this post hoc analysis underscore the limitations of colposcopy. Just as results of a prior study indicated that taking two or more biopsies increases diagnostic yield,1 this large study points out the substantial benefit gained from performing a random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction when no colposcopic lesions are identified.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al; SCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):264–272.

Reference

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al; SCUS LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):264–272.

Ovarian cancer often arises from precursor endometriosis

LAS VEGAS – Gynecologists, general surgeons, and primary care physicians now share an unprecedented opportunity to put a major dent in the incidence of ovarian cancer, according to Dr. Farr R. Nezhat.

Mounting evidence suggests that identification and complete surgical removal of endometriosis reduce the risk of several histologic types of ovarian cancer. So when a woman visits her primary care physician for pelvic pain or vaginal bleeding that might be due to endometrial pathology, or a general surgeon finds asymptomatic endometriosis during pelvic surgery, these encounters provide an opportunity for preventive intervention, explained Dr. Nezhat, professor of ob.gyn. and director of minimally invasive surgery and gynecologic robotics at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

The latest thinking about the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer, he noted, is that there are two different types of the malignancy. One type, which likely arises from endometriosis as the precursor lesion, is characterized by low-grade serous, clear cell, and endometrioid carcinomas, which tend to present at an earlier stage and are more indolent. They are associated with mutations in the PTEN, BCL2, and ARID1A genes.

A pooled analysis of 13 ovarian cancer case-control studies conducted by investigators in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium made the point that women with endometriosis are at increased risk of specific subtypes of the malignancy. The analysis, which included 7,911 women with invasive ovarian cancer, 1,907 others with borderline ovarian cancer, and more than 13,000 controls, concluded that women with a self-reported history of endometriosis had a 3.05-fold increased risk of clear cell invasive ovarian cancer, compared with controls, a 2.04-fold increased risk of endometrioid ovarian cancer, and a 2.11-fold greater likelihood of low-grade serous ovarian cancer.

In contrast, no association was apparent between endometriosis and the risk of high-grade serous or mucinous invasive ovarian cancer or borderline tumors. Thus, the pathogenesis of low- and high-grade serous ovarian cancers may differ (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:385-94).

Dr. Nezhat cited as another influential study a Swedish national registry case-control study involving all Swedes with a first-time hospital discharge diagnosis of endometriosis during 1969-2007. The cases in this study were all 220 Swedish women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer at least 1 year after their endometriosis was diagnosed. Each was matched with two controls with no ovarian cancer diagnosis before the date of the case’s cancer diagnosis.

This was the first published study to demonstrate that treatment of endometriosis has a salutary impact on subsequent risk of ovarian cancer. Complete surgical removal of all visible endometriotic tissue was associated with a 63% reduction in the risk of ovarian cancer in a univariate analysis and a 70% relative risk reduction in a multivariate analysis. One-sided oophorectomy involving the endometriosis-involved ovary was similarly associated with a 58% risk reduction for ovarian cancer in a univariate analysis and an 81% reduction in risk in a multivariate analysis (Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2013:92:546-54).

An earlier study in which Dr. Nezhat was senior author highlighted that different histologic types of early-stage ovarian carcinoma feature distinctive patterns of clinical symptoms. The study included 76 consecutive patients with FIGO stage I ovarian carcinoma, of which 54 – that is, more than two-thirds – were nonserous, which is a much higher proportion than is seen in women diagnosed with stage III and IV disease.

Most patients with serous papillary carcinoma in this series presented with an asymptomatic pelvic mass. In contrast, most of those with endometrioid or clear cell carcinoma presented with pelvic pain or abnormal vaginal bleeding with or without a pelvic mass (Fertil. Steril. 2007;88:906-10).

Endometrioisis is a pervasive condition. Dr. Nezhat said the endometriosis patients he considers to be at possible increased risk for ovarian cancer include those with longstanding endometriosis, a history of infertility, endometriosis diagnosed at an early age, as well as those with ovarian endometriomas. Eventually it will be possible to pin down more precisely the ovarian cancer risk of an individual with endometriosis through screening for genetic mutations, but the evidence base isn’t yet sufficient to introduce this into everyday practice, he said.

One audience member said it’s her practice and that of many of her gynecologic colleagues that when they incidentally find a patient has asymptomatic endometriosis, for example, during surgery for ectopic pregnancy, they will often leave it in place, even if it is quite severe. Is it time to rethink that practice and instead remove all visible endometriosis, even if the patient is asymptomatic? she asked.

“The short answer is, Yes,” Dr. Nezhat replied. “The most important thing is that when you do surgery, remove it all or else do biopsies to make sure you’re not leaving early ovarian cancer behind. Draining endometriomas is not adequate.”

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

LAS VEGAS – Gynecologists, general surgeons, and primary care physicians now share an unprecedented opportunity to put a major dent in the incidence of ovarian cancer, according to Dr. Farr R. Nezhat.

Mounting evidence suggests that identification and complete surgical removal of endometriosis reduce the risk of several histologic types of ovarian cancer. So when a woman visits her primary care physician for pelvic pain or vaginal bleeding that might be due to endometrial pathology, or a general surgeon finds asymptomatic endometriosis during pelvic surgery, these encounters provide an opportunity for preventive intervention, explained Dr. Nezhat, professor of ob.gyn. and director of minimally invasive surgery and gynecologic robotics at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

The latest thinking about the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer, he noted, is that there are two different types of the malignancy. One type, which likely arises from endometriosis as the precursor lesion, is characterized by low-grade serous, clear cell, and endometrioid carcinomas, which tend to present at an earlier stage and are more indolent. They are associated with mutations in the PTEN, BCL2, and ARID1A genes.

A pooled analysis of 13 ovarian cancer case-control studies conducted by investigators in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium made the point that women with endometriosis are at increased risk of specific subtypes of the malignancy. The analysis, which included 7,911 women with invasive ovarian cancer, 1,907 others with borderline ovarian cancer, and more than 13,000 controls, concluded that women with a self-reported history of endometriosis had a 3.05-fold increased risk of clear cell invasive ovarian cancer, compared with controls, a 2.04-fold increased risk of endometrioid ovarian cancer, and a 2.11-fold greater likelihood of low-grade serous ovarian cancer.

In contrast, no association was apparent between endometriosis and the risk of high-grade serous or mucinous invasive ovarian cancer or borderline tumors. Thus, the pathogenesis of low- and high-grade serous ovarian cancers may differ (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:385-94).

Dr. Nezhat cited as another influential study a Swedish national registry case-control study involving all Swedes with a first-time hospital discharge diagnosis of endometriosis during 1969-2007. The cases in this study were all 220 Swedish women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer at least 1 year after their endometriosis was diagnosed. Each was matched with two controls with no ovarian cancer diagnosis before the date of the case’s cancer diagnosis.

This was the first published study to demonstrate that treatment of endometriosis has a salutary impact on subsequent risk of ovarian cancer. Complete surgical removal of all visible endometriotic tissue was associated with a 63% reduction in the risk of ovarian cancer in a univariate analysis and a 70% relative risk reduction in a multivariate analysis. One-sided oophorectomy involving the endometriosis-involved ovary was similarly associated with a 58% risk reduction for ovarian cancer in a univariate analysis and an 81% reduction in risk in a multivariate analysis (Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2013:92:546-54).

An earlier study in which Dr. Nezhat was senior author highlighted that different histologic types of early-stage ovarian carcinoma feature distinctive patterns of clinical symptoms. The study included 76 consecutive patients with FIGO stage I ovarian carcinoma, of which 54 – that is, more than two-thirds – were nonserous, which is a much higher proportion than is seen in women diagnosed with stage III and IV disease.

Most patients with serous papillary carcinoma in this series presented with an asymptomatic pelvic mass. In contrast, most of those with endometrioid or clear cell carcinoma presented with pelvic pain or abnormal vaginal bleeding with or without a pelvic mass (Fertil. Steril. 2007;88:906-10).

Endometrioisis is a pervasive condition. Dr. Nezhat said the endometriosis patients he considers to be at possible increased risk for ovarian cancer include those with longstanding endometriosis, a history of infertility, endometriosis diagnosed at an early age, as well as those with ovarian endometriomas. Eventually it will be possible to pin down more precisely the ovarian cancer risk of an individual with endometriosis through screening for genetic mutations, but the evidence base isn’t yet sufficient to introduce this into everyday practice, he said.

One audience member said it’s her practice and that of many of her gynecologic colleagues that when they incidentally find a patient has asymptomatic endometriosis, for example, during surgery for ectopic pregnancy, they will often leave it in place, even if it is quite severe. Is it time to rethink that practice and instead remove all visible endometriosis, even if the patient is asymptomatic? she asked.

“The short answer is, Yes,” Dr. Nezhat replied. “The most important thing is that when you do surgery, remove it all or else do biopsies to make sure you’re not leaving early ovarian cancer behind. Draining endometriomas is not adequate.”

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

LAS VEGAS – Gynecologists, general surgeons, and primary care physicians now share an unprecedented opportunity to put a major dent in the incidence of ovarian cancer, according to Dr. Farr R. Nezhat.

Mounting evidence suggests that identification and complete surgical removal of endometriosis reduce the risk of several histologic types of ovarian cancer. So when a woman visits her primary care physician for pelvic pain or vaginal bleeding that might be due to endometrial pathology, or a general surgeon finds asymptomatic endometriosis during pelvic surgery, these encounters provide an opportunity for preventive intervention, explained Dr. Nezhat, professor of ob.gyn. and director of minimally invasive surgery and gynecologic robotics at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

The latest thinking about the pathophysiology of ovarian cancer, he noted, is that there are two different types of the malignancy. One type, which likely arises from endometriosis as the precursor lesion, is characterized by low-grade serous, clear cell, and endometrioid carcinomas, which tend to present at an earlier stage and are more indolent. They are associated with mutations in the PTEN, BCL2, and ARID1A genes.

A pooled analysis of 13 ovarian cancer case-control studies conducted by investigators in the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium made the point that women with endometriosis are at increased risk of specific subtypes of the malignancy. The analysis, which included 7,911 women with invasive ovarian cancer, 1,907 others with borderline ovarian cancer, and more than 13,000 controls, concluded that women with a self-reported history of endometriosis had a 3.05-fold increased risk of clear cell invasive ovarian cancer, compared with controls, a 2.04-fold increased risk of endometrioid ovarian cancer, and a 2.11-fold greater likelihood of low-grade serous ovarian cancer.

In contrast, no association was apparent between endometriosis and the risk of high-grade serous or mucinous invasive ovarian cancer or borderline tumors. Thus, the pathogenesis of low- and high-grade serous ovarian cancers may differ (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:385-94).

Dr. Nezhat cited as another influential study a Swedish national registry case-control study involving all Swedes with a first-time hospital discharge diagnosis of endometriosis during 1969-2007. The cases in this study were all 220 Swedish women diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer at least 1 year after their endometriosis was diagnosed. Each was matched with two controls with no ovarian cancer diagnosis before the date of the case’s cancer diagnosis.

This was the first published study to demonstrate that treatment of endometriosis has a salutary impact on subsequent risk of ovarian cancer. Complete surgical removal of all visible endometriotic tissue was associated with a 63% reduction in the risk of ovarian cancer in a univariate analysis and a 70% relative risk reduction in a multivariate analysis. One-sided oophorectomy involving the endometriosis-involved ovary was similarly associated with a 58% risk reduction for ovarian cancer in a univariate analysis and an 81% reduction in risk in a multivariate analysis (Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2013:92:546-54).

An earlier study in which Dr. Nezhat was senior author highlighted that different histologic types of early-stage ovarian carcinoma feature distinctive patterns of clinical symptoms. The study included 76 consecutive patients with FIGO stage I ovarian carcinoma, of which 54 – that is, more than two-thirds – were nonserous, which is a much higher proportion than is seen in women diagnosed with stage III and IV disease.

Most patients with serous papillary carcinoma in this series presented with an asymptomatic pelvic mass. In contrast, most of those with endometrioid or clear cell carcinoma presented with pelvic pain or abnormal vaginal bleeding with or without a pelvic mass (Fertil. Steril. 2007;88:906-10).

Endometrioisis is a pervasive condition. Dr. Nezhat said the endometriosis patients he considers to be at possible increased risk for ovarian cancer include those with longstanding endometriosis, a history of infertility, endometriosis diagnosed at an early age, as well as those with ovarian endometriomas. Eventually it will be possible to pin down more precisely the ovarian cancer risk of an individual with endometriosis through screening for genetic mutations, but the evidence base isn’t yet sufficient to introduce this into everyday practice, he said.

One audience member said it’s her practice and that of many of her gynecologic colleagues that when they incidentally find a patient has asymptomatic endometriosis, for example, during surgery for ectopic pregnancy, they will often leave it in place, even if it is quite severe. Is it time to rethink that practice and instead remove all visible endometriosis, even if the patient is asymptomatic? she asked.

“The short answer is, Yes,” Dr. Nezhat replied. “The most important thing is that when you do surgery, remove it all or else do biopsies to make sure you’re not leaving early ovarian cancer behind. Draining endometriomas is not adequate.”

He reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY WEEK

Urinary incontinence – An individual and societal ill

Urinary incontinence is a major health care concern, both in terms of the numbers of women who are suffering and with respect to societal costs and the impact on health care spending. Approximately 15 years ago, an international group reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that 200 million people worldwide – 75%-80% of them women – were suffering from urinary incontinence (JAMA 1998;280:951-3).

Since then, a high prevalence of urinary incontinence has been documented in various studies and reports. Experts have estimated, for instance, that between 13 million and 25 million adult Americans experience transient or chronic symptoms, and that approximately half of these patients suffer from severe or bothersome symptoms. Again, the majority of these individuals are women.

Consumer-based research suggests that 25% of women over the age of 18 years experience episodes of urinary incontinence, according to prevalence data collected by the National Association for Continence. In 2001, 10% of women under the age of 65 years and 35% of women over 65 had symptoms of involuntary leakage, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Despite this, nearly two-thirds of patients never discussed bladder health with their health care provider and on average, women wait over 6 years from symptom onset before a diagnosis is established. Moreover, the costs are significant; in 2001, the cost for urinary incontinence in the United States was $16.3 billion (Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;98:398-406).

There are four types of urinary incontinence – urge, stress, mixed, and overflow. Urge incontinence typically is accompanied by urgency. Stress incontinence occurs with the increased abdominal pressure that accompanies effort, exertion, laughing, coughing, and sneezing. Overflow incontinence generally involves continuous urinary loss and incomplete bladder emptying.

Over the next four installments of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have chosen to feature the workup and treatment of urinary incontinence. For our first installment, I have asked my former resident Dr. Sandra Culbertson, who is now a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago, to share her knowledge of the optimal approach for evaluating urinary incontinence in the office. As she explains, it is critical to discern the uncomplicated cases of stress urinary incontinence from possibly complicated cases that require more assessment.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller had no relevant financial disclosures.

Urinary incontinence is a major health care concern, both in terms of the numbers of women who are suffering and with respect to societal costs and the impact on health care spending. Approximately 15 years ago, an international group reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that 200 million people worldwide – 75%-80% of them women – were suffering from urinary incontinence (JAMA 1998;280:951-3).

Since then, a high prevalence of urinary incontinence has been documented in various studies and reports. Experts have estimated, for instance, that between 13 million and 25 million adult Americans experience transient or chronic symptoms, and that approximately half of these patients suffer from severe or bothersome symptoms. Again, the majority of these individuals are women.

Consumer-based research suggests that 25% of women over the age of 18 years experience episodes of urinary incontinence, according to prevalence data collected by the National Association for Continence. In 2001, 10% of women under the age of 65 years and 35% of women over 65 had symptoms of involuntary leakage, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Despite this, nearly two-thirds of patients never discussed bladder health with their health care provider and on average, women wait over 6 years from symptom onset before a diagnosis is established. Moreover, the costs are significant; in 2001, the cost for urinary incontinence in the United States was $16.3 billion (Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;98:398-406).

There are four types of urinary incontinence – urge, stress, mixed, and overflow. Urge incontinence typically is accompanied by urgency. Stress incontinence occurs with the increased abdominal pressure that accompanies effort, exertion, laughing, coughing, and sneezing. Overflow incontinence generally involves continuous urinary loss and incomplete bladder emptying.

Over the next four installments of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have chosen to feature the workup and treatment of urinary incontinence. For our first installment, I have asked my former resident Dr. Sandra Culbertson, who is now a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago, to share her knowledge of the optimal approach for evaluating urinary incontinence in the office. As she explains, it is critical to discern the uncomplicated cases of stress urinary incontinence from possibly complicated cases that require more assessment.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller had no relevant financial disclosures.

Urinary incontinence is a major health care concern, both in terms of the numbers of women who are suffering and with respect to societal costs and the impact on health care spending. Approximately 15 years ago, an international group reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association that 200 million people worldwide – 75%-80% of them women – were suffering from urinary incontinence (JAMA 1998;280:951-3).

Since then, a high prevalence of urinary incontinence has been documented in various studies and reports. Experts have estimated, for instance, that between 13 million and 25 million adult Americans experience transient or chronic symptoms, and that approximately half of these patients suffer from severe or bothersome symptoms. Again, the majority of these individuals are women.

Consumer-based research suggests that 25% of women over the age of 18 years experience episodes of urinary incontinence, according to prevalence data collected by the National Association for Continence. In 2001, 10% of women under the age of 65 years and 35% of women over 65 had symptoms of involuntary leakage, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Despite this, nearly two-thirds of patients never discussed bladder health with their health care provider and on average, women wait over 6 years from symptom onset before a diagnosis is established. Moreover, the costs are significant; in 2001, the cost for urinary incontinence in the United States was $16.3 billion (Obstet. Gynecol. 2001;98:398-406).

There are four types of urinary incontinence – urge, stress, mixed, and overflow. Urge incontinence typically is accompanied by urgency. Stress incontinence occurs with the increased abdominal pressure that accompanies effort, exertion, laughing, coughing, and sneezing. Overflow incontinence generally involves continuous urinary loss and incomplete bladder emptying.

Over the next four installments of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have chosen to feature the workup and treatment of urinary incontinence. For our first installment, I have asked my former resident Dr. Sandra Culbertson, who is now a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago, to share her knowledge of the optimal approach for evaluating urinary incontinence in the office. As she explains, it is critical to discern the uncomplicated cases of stress urinary incontinence from possibly complicated cases that require more assessment.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller had no relevant financial disclosures.

Master Class: Office evaluation for incontinence

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

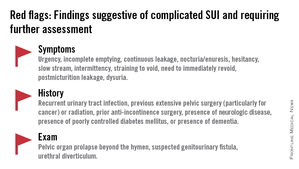

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

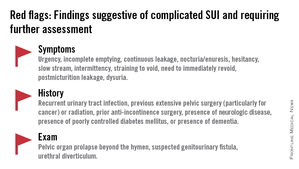

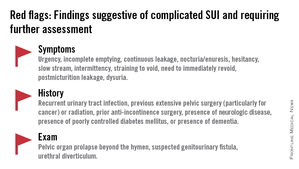

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.

The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire can be used to further assess the impact of symptoms. The short-form IIQ (the IIQ-7) asks, for instance, about the extent to which urine leakage has affected household chores, physical recreation, social activities, or emotional health.

Since the UDI and IIQ were developed about 20 years ago, at least several other urinary incontinence questionnaires have been developed and validated. Whether or not questionnaires are utilized as official tools, history taking should capture their essence and provide you with enough information to ascertain the type of incontinence, frequency of occurrence, severity, and effect on daily life.

The history also must assess the possibility of voiding dysfunction. Positive responses to questions about nocturia, hesitancy, and the need to immediately revoid, for instance, point toward complicated SUI and the need for further assessment before embarking on surgical treatment for SUI.

Patients who have uncomplicated SUI, on the other hand, will answer negatively to questions about symptoms of predominant urgency, functional impairment, continuous leakage, and/or incomplete emptying. They also will not have had recurrent urinary tract infections or medical conditions that can affect lower urinary tract function (such as neurologic disease and poorly controlled diabetes).

The physical exam

Along with the history, the physical exam is important for identifying complicated SUI and confirming which cases of SUI are truly uncomplicated. Evaluation should include a cough stress test to confirm leakage from the urethra under stress, an assessment of urethral mobility, and an assessment for pelvic organ prolapse.

The cough stress test is usually done with the patient in the supine or semirecumbent lithotomy position. If you strongly suspect stress incontinence but have a negative result, consider the following:

• Make sure the patient has a comfortably full bladder.

• Many women will contract their pelvic floor muscles when coughing to try to avoid leaking. You can apply pressure against the posterior vaginal wall either digitally or with half of the bivalve speculum to keep the patient from activating her muscles.

• The cough test can be performed in the standing position.

Assessing urethral mobility similarly involves simple observation while the patient is in a supine lithotomy position and straining. A Q-tip test or the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system may be used, but visualization and palpation also are completely acceptable.

Just as the absence of urethral mobility is a red flag, so is prolapse beyond the hymen. This patient could potentially have urethral kinking, which can mask the severity of SUI or be a source of retention. Either finding the absence of urethral mobility or the presence of POP beyond the hymen moves the case from the uncomplicated to complicated category and signals the need for further evaluation with urodynamics or other tests.

These and other findings for uncomplicated versus complicated SUI are outlined in a committee opinion issued recently by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Urogynecologic Society (Committee Opinion No. 603, Obstet .Gynecol. 2014;123:1403-7).

As the ACOG-AUGS recommendations point out, urinalysis is part of the minimum work-up for stress incontinence. Measurement of postvoid residual urine volume also becomes important when midurethral sling surgery is being contemplated for uncomplicated SUI. A normal volume rules out potential bladder-emptying abnormalities and provides final assurance that the patient is a good candidate for surgical repair.

Recent research on urodynamics

Evidence that a simple office-based incontinence evaluation without preoperative urodynamic testing is appropriate for uncomplicated predominant SUI comes largely from two recent randomized noninferiority trials.

One of these trials – a study from the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network in the United States, known as the VALUE trial – randomized 630 women with uncomplicated SUI to pretreatment work-up with or without urodynamics. Treatment success at 12 months was similar for the two groups (approximately 77%).

This finding, the authors wrote, suggests that for women with uncomplicated SUI, a “basic office evaluation” (i.e., a positive provocative stress test, a normal postvoiding residual volume, an assessment or urethral mobility, and a negative urinalysis) is a “sufficient preoperative work-up” (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1987-97).

The diagnosis of SUI as made by office evaluation was confirmed in 97% of women who underwent urodynamic testing, and while there were some adjustments in diagnosis after urodynamics, there were no major changes in treatment decision making after the testing. Approximately 93% of women in both groups underwent midurethral sling surgery.

The second trial, a Dutch study, focused on women who had already undergone urodynamic testing and been shown to have discordant findings on urodynamics and their history and clinical exam. The women – all of whom had uncomplicated predominant SUI – were randomized to undergo immediate midurethral sling surgery or receive individually tailored treatment (including sling surgery, behavioral and physical therapy, pessary, and anticholinergics).

At 1 year, there was no clinically significant difference between the two groups in patients’ assessment of their symptoms as measured by the UDI. The authors concluded that “an immediate midurethral sling operation is not inferior to individually tailored treatment based on urodynamic findings” and that “urodynamics should no longer be advised routinely before primary surgery in these patients” (Obstet. Gynecol. 2013;121:999-1008).

When urge incontinence is involved

Urodynamic testing was never believed to be perfect, but these and other studies have highlighted its imperfections. Urodynamics creates an artificial condition in the bladder, in effect, and some of the findings will involve artifact. A systematic review of studies that compared diagnoses based on symptoms with diagnoses after urodynamic investigation was interesting in this regard; while the review did not assess impact on treatment, it showed that there is poor agreement between clinical symptoms and urodynamic-based diagnoses (Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011;30:495-502).

Certainly, women with complicated SUI – as well as women who have recurrent SUI after a prior surgical intervention – require further assessment, which likely includes multichannel urodynamic testing.

Urodynamics also can play a useful role in decision making and counseling for some patients whose incontinence is predominately SUI, but is believed to involve some degree of urinary urgency. Patients with mixed urinary incontinence fare worse after midurethral sling procedures compared with patients who have SUI alone, and I counsel my patients accordingly, emphasizing that the sling will not address aspects of their incontinence related to urgency. When I sense that a patient may have unreasonably high expectations for surgery, urodynamic testing can provide some perspective on possible postoperative outcomes.

Treatment for UI or overactive bladder often may be initiated after simple office-based evaluation, just as with SUI. The goal, similarly, is to discern relatively uncomplicated or straightforward cases from complicated ones. Urologic, medical, and neurologic histories should be obtained, for instance, and retention issues (which can aggravate UI) should be ruled out through the measurement of postvoid residual urine volume.

Just as with SUI, evaluation of suspected UI more often than not involves careful history taking and clinical probing. A voiding diary can sometimes be helpful; I send patients home with such a tool when the history is inconclusive or I suspect behavioral (excessive fluid intake) or functional issues as significant factors in bladder control.

It is important to keep in mind that patients with severe SUI may have urinary frequency as a learned response. Such patients appear to have overactive bladder in addition to SUI, but may actually be urinating frequently because they’ve learned that doing so results in less leakage. In our practice we’ve observed that patients with a learned response tend not to have nocturia, while those with overactive bladder do report nocturia.

Dr. Culbertson had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Culbertson is a professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago.

Ten years ago, urodynamics were widely viewed as the gold standard for evaluating urinary incontinence. We often turned to such testing to confirm or reject the findings of our basic evaluation before determining the best type of treatment – especially before proceeding with primary anti-incontinence surgery.

What has emerged in recent years is a body of evidence that tells us otherwise. We now know that urodynamics do not give us all the answers, and that we can be much more judicious with its use.

A good history followed by a thorough physical examination and some office tests often enables us to make sound treatment recommendations without costly and potentially uncomfortable urodynamic testing. The key lies in discerning complicated and uncomplicated cases. For patients deemed to have uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence (SUI) – especially those who have failed conservative management – we can comfortably recommend surgical repair without urodynamic testing.

Identifying uncomplicated SUI

The history is the most important part of the evaluation for incontinence. Every patient who answers “yes” to a basic opening question about whether she has any concerns about bladder control should be asked a series of questions that will enable the physician to fully understand her symptoms, their severity, and their impact on her life and daily activities.

It is critical to determine whether you are dealing with pure SUI, pure urge incontinence (UI), or SUI with a component of UI. Mixed incontinence is quite prevalent. An analysis of recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data showed that of those women reporting incontinence symptoms, almost 50% reported pure SUI, and 34% reported mixed incontinence (J. Urol. 2008;179: 656-61). Other studies similarly have shown prevalence rates of mixed incontinence above 30%.

The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) recommends the use of validated questionnaires to assess incontinence and the relative contribution of UI and SUI symptoms. Some physicians do find the organized and structured format of questionnaires helpful in their practices. Others have incorporated questions from various tools into history-taking templates on their electronic medical records. Still others have made them part of a mental checklist for history taking.

The short-form version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), for instance, asks the patient whether she experiences – and how much she is bothered by – the following: frequent urination; leakage related to a feeling of urgency; leakage related to activity, coughing, or sneezing; small amount of leakage; difficulty emptying the bladder; and pain or discomfort in the lower abdominal or genital area.