User login

Palliative care improves QoL for patients with Parkinson’s disease and related disorders

, according to results from a randomized clinical trial in JAMA Neurology.

The benefits of palliative care even extended to patients’ caregivers, who also appeared to benefit from outpatient palliative care at the 12-month mark, according to lead author Benzi M. Kluger, MD, of the department of neurology, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues.

Between November 2015 and September 2017, Dr. Kluger and colleagues included 210 patients into the trial from three participating academic tertiary care centers who had “moderate to high palliative care needs” as assessed by the Palliative Care Needs Assessment Tool, which the researchers said are “common reasons for referral” and “reflect a desire to meet patient-centered needs rather than disease-centered markers.” Patients were primarily non-Hispanic white men with a mean age of about 70 years. The researchers also included 175 caregivers in the trial, most of whom were women, spouses to the patients, and in their caregiver role for over 5.5 years.

Patients with PDRD were randomized to receive standard care – usual care through their primary care physician and a neurologist – or “integrated outpatient palliative care,” from a team consisting of a palliative neurologist, nurse, social worker, chaplain, and board-certified palliative medicine physician. The goal of palliative care was addressing “nonmotor symptoms, goals of care, anticipatory guidance, difficult emotions, and caregiver support,” which patients received every 3 months through an in-person outpatient visit or telemedicine.

Quality of life for patients was measured through the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) scale, and caregiver burden was assessed with the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12). The researchers also measured symptom burden and other QoL measures using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale–Revised for Parkinson’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Prolonged Grief Disorder questionnaire, and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being.

Overall, 87 of 105 (82.1%) of patients in the palliative care group went to all their outpatient palliative care visits, and 19 of 106 (17.9%) patients received palliative care through telemedicine. Patients in the palliative care group also attended more neurology visits (4.66 visits) than those in the standard care (3.16 visits) group.

Quality of life significantly improved for patients in the palliative care group, compared with patients receiving standard care only at 6 months (0.66 vs. –0.84; between-group difference, 1.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.47-3.27; P = .009) and at 12 months (0.68 vs. –0.42; between-group difference, 1.36; 95% CI, −0.01 to 2.73; P = .05). These results remained significant at 6 months and 12 months after researchers used multiple imputation to fill in missing data. While there was no significant difference in caregiver burden between groups at 6 months, there was a statistically significant difference at 12 months favoring the palliative care group (between-group difference, −2.60; 95% CI, −4.58 to −0.61; P = .01).

Patients receiving palliative care also had better nonmotor symptom burden, motor symptom severity, and were more likely to complete advance directives, compared with patients receiving standard care alone. “We hypothesize that motor improvements may have reflected an unanticipated benefit of our palliative care team’s general goal of encouraging activities that promoted joy, meaning, and connection,” Dr. Kluger and colleagues said. Researchers also noted that the intervention patients with greater need for palliative care tended to benefit more than patients with patients with lower palliative care needs.

“Because the palliative care intervention is time-intensive and resource-intensive, future studies should optimize triage tools and consider alternative models of care delivery, such as telemedicine or care navigators, to provide key aspects of the intervention at lower cost,” they said.

In a related editorial, Bastiaan R. Bloem, MD, PhD, from the Center of Expertise for Parkinson & Movement Disorders, at Radboud University Medical Center, in the Netherlands, and colleagues acknowledged that the study by Kluger et al. is “timely and practical” because it introduces a system for outpatient palliative care for patients with PDRD at a time when there is “growing awareness that palliative care may also benefit persons with neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease.”

The study is also important because it highlights that patients at varying stages of disease, including mild disease, may benefit from an integrated outpatient palliative model, which is not usually considered when determining candidates for palliative care in other scenarios, such as in patients with cancer. Future studies are warranted to assess how palliative care models can be implemented in different disease states and health care settings, they said.

“These new studies should continue to highlight the fact that palliative care is not about terminal diseases and dying,” Dr. Bloem and colleagues concluded. “As Kluger and colleagues indicate in their important clinical trial, palliative care is about how to live well.”

Six authors reported receiving a grant from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, which was the funding source for the study. Two authors reported receiving grants from the University Hospital Foundation during the study. One author reported receiving grants from Allergan and Merz Pharma and is a consultant for GE Pharmaceuticals and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; another reported receiving grants from the Archstone Foundation, the California Health Care Foundation, the Cambia Health Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Institute of Nursing Research, the Stupski Foundation, and the UniHealth Foundation. Dr. Bloem and a colleague reported their institution received a center of excellence grant from the Parkinson’s Foundation.

SOURCE: Kluger B et al. JAMA Neurol. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4992.

, according to results from a randomized clinical trial in JAMA Neurology.

The benefits of palliative care even extended to patients’ caregivers, who also appeared to benefit from outpatient palliative care at the 12-month mark, according to lead author Benzi M. Kluger, MD, of the department of neurology, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues.

Between November 2015 and September 2017, Dr. Kluger and colleagues included 210 patients into the trial from three participating academic tertiary care centers who had “moderate to high palliative care needs” as assessed by the Palliative Care Needs Assessment Tool, which the researchers said are “common reasons for referral” and “reflect a desire to meet patient-centered needs rather than disease-centered markers.” Patients were primarily non-Hispanic white men with a mean age of about 70 years. The researchers also included 175 caregivers in the trial, most of whom were women, spouses to the patients, and in their caregiver role for over 5.5 years.

Patients with PDRD were randomized to receive standard care – usual care through their primary care physician and a neurologist – or “integrated outpatient palliative care,” from a team consisting of a palliative neurologist, nurse, social worker, chaplain, and board-certified palliative medicine physician. The goal of palliative care was addressing “nonmotor symptoms, goals of care, anticipatory guidance, difficult emotions, and caregiver support,” which patients received every 3 months through an in-person outpatient visit or telemedicine.

Quality of life for patients was measured through the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) scale, and caregiver burden was assessed with the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12). The researchers also measured symptom burden and other QoL measures using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale–Revised for Parkinson’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Prolonged Grief Disorder questionnaire, and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being.

Overall, 87 of 105 (82.1%) of patients in the palliative care group went to all their outpatient palliative care visits, and 19 of 106 (17.9%) patients received palliative care through telemedicine. Patients in the palliative care group also attended more neurology visits (4.66 visits) than those in the standard care (3.16 visits) group.

Quality of life significantly improved for patients in the palliative care group, compared with patients receiving standard care only at 6 months (0.66 vs. –0.84; between-group difference, 1.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.47-3.27; P = .009) and at 12 months (0.68 vs. –0.42; between-group difference, 1.36; 95% CI, −0.01 to 2.73; P = .05). These results remained significant at 6 months and 12 months after researchers used multiple imputation to fill in missing data. While there was no significant difference in caregiver burden between groups at 6 months, there was a statistically significant difference at 12 months favoring the palliative care group (between-group difference, −2.60; 95% CI, −4.58 to −0.61; P = .01).

Patients receiving palliative care also had better nonmotor symptom burden, motor symptom severity, and were more likely to complete advance directives, compared with patients receiving standard care alone. “We hypothesize that motor improvements may have reflected an unanticipated benefit of our palliative care team’s general goal of encouraging activities that promoted joy, meaning, and connection,” Dr. Kluger and colleagues said. Researchers also noted that the intervention patients with greater need for palliative care tended to benefit more than patients with patients with lower palliative care needs.

“Because the palliative care intervention is time-intensive and resource-intensive, future studies should optimize triage tools and consider alternative models of care delivery, such as telemedicine or care navigators, to provide key aspects of the intervention at lower cost,” they said.

In a related editorial, Bastiaan R. Bloem, MD, PhD, from the Center of Expertise for Parkinson & Movement Disorders, at Radboud University Medical Center, in the Netherlands, and colleagues acknowledged that the study by Kluger et al. is “timely and practical” because it introduces a system for outpatient palliative care for patients with PDRD at a time when there is “growing awareness that palliative care may also benefit persons with neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease.”

The study is also important because it highlights that patients at varying stages of disease, including mild disease, may benefit from an integrated outpatient palliative model, which is not usually considered when determining candidates for palliative care in other scenarios, such as in patients with cancer. Future studies are warranted to assess how palliative care models can be implemented in different disease states and health care settings, they said.

“These new studies should continue to highlight the fact that palliative care is not about terminal diseases and dying,” Dr. Bloem and colleagues concluded. “As Kluger and colleagues indicate in their important clinical trial, palliative care is about how to live well.”

Six authors reported receiving a grant from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, which was the funding source for the study. Two authors reported receiving grants from the University Hospital Foundation during the study. One author reported receiving grants from Allergan and Merz Pharma and is a consultant for GE Pharmaceuticals and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; another reported receiving grants from the Archstone Foundation, the California Health Care Foundation, the Cambia Health Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Institute of Nursing Research, the Stupski Foundation, and the UniHealth Foundation. Dr. Bloem and a colleague reported their institution received a center of excellence grant from the Parkinson’s Foundation.

SOURCE: Kluger B et al. JAMA Neurol. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4992.

, according to results from a randomized clinical trial in JAMA Neurology.

The benefits of palliative care even extended to patients’ caregivers, who also appeared to benefit from outpatient palliative care at the 12-month mark, according to lead author Benzi M. Kluger, MD, of the department of neurology, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues.

Between November 2015 and September 2017, Dr. Kluger and colleagues included 210 patients into the trial from three participating academic tertiary care centers who had “moderate to high palliative care needs” as assessed by the Palliative Care Needs Assessment Tool, which the researchers said are “common reasons for referral” and “reflect a desire to meet patient-centered needs rather than disease-centered markers.” Patients were primarily non-Hispanic white men with a mean age of about 70 years. The researchers also included 175 caregivers in the trial, most of whom were women, spouses to the patients, and in their caregiver role for over 5.5 years.

Patients with PDRD were randomized to receive standard care – usual care through their primary care physician and a neurologist – or “integrated outpatient palliative care,” from a team consisting of a palliative neurologist, nurse, social worker, chaplain, and board-certified palliative medicine physician. The goal of palliative care was addressing “nonmotor symptoms, goals of care, anticipatory guidance, difficult emotions, and caregiver support,” which patients received every 3 months through an in-person outpatient visit or telemedicine.

Quality of life for patients was measured through the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) scale, and caregiver burden was assessed with the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12). The researchers also measured symptom burden and other QoL measures using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale–Revised for Parkinson’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Prolonged Grief Disorder questionnaire, and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual Well-Being.

Overall, 87 of 105 (82.1%) of patients in the palliative care group went to all their outpatient palliative care visits, and 19 of 106 (17.9%) patients received palliative care through telemedicine. Patients in the palliative care group also attended more neurology visits (4.66 visits) than those in the standard care (3.16 visits) group.

Quality of life significantly improved for patients in the palliative care group, compared with patients receiving standard care only at 6 months (0.66 vs. –0.84; between-group difference, 1.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.47-3.27; P = .009) and at 12 months (0.68 vs. –0.42; between-group difference, 1.36; 95% CI, −0.01 to 2.73; P = .05). These results remained significant at 6 months and 12 months after researchers used multiple imputation to fill in missing data. While there was no significant difference in caregiver burden between groups at 6 months, there was a statistically significant difference at 12 months favoring the palliative care group (between-group difference, −2.60; 95% CI, −4.58 to −0.61; P = .01).

Patients receiving palliative care also had better nonmotor symptom burden, motor symptom severity, and were more likely to complete advance directives, compared with patients receiving standard care alone. “We hypothesize that motor improvements may have reflected an unanticipated benefit of our palliative care team’s general goal of encouraging activities that promoted joy, meaning, and connection,” Dr. Kluger and colleagues said. Researchers also noted that the intervention patients with greater need for palliative care tended to benefit more than patients with patients with lower palliative care needs.

“Because the palliative care intervention is time-intensive and resource-intensive, future studies should optimize triage tools and consider alternative models of care delivery, such as telemedicine or care navigators, to provide key aspects of the intervention at lower cost,” they said.

In a related editorial, Bastiaan R. Bloem, MD, PhD, from the Center of Expertise for Parkinson & Movement Disorders, at Radboud University Medical Center, in the Netherlands, and colleagues acknowledged that the study by Kluger et al. is “timely and practical” because it introduces a system for outpatient palliative care for patients with PDRD at a time when there is “growing awareness that palliative care may also benefit persons with neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease.”

The study is also important because it highlights that patients at varying stages of disease, including mild disease, may benefit from an integrated outpatient palliative model, which is not usually considered when determining candidates for palliative care in other scenarios, such as in patients with cancer. Future studies are warranted to assess how palliative care models can be implemented in different disease states and health care settings, they said.

“These new studies should continue to highlight the fact that palliative care is not about terminal diseases and dying,” Dr. Bloem and colleagues concluded. “As Kluger and colleagues indicate in their important clinical trial, palliative care is about how to live well.”

Six authors reported receiving a grant from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, which was the funding source for the study. Two authors reported receiving grants from the University Hospital Foundation during the study. One author reported receiving grants from Allergan and Merz Pharma and is a consultant for GE Pharmaceuticals and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; another reported receiving grants from the Archstone Foundation, the California Health Care Foundation, the Cambia Health Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Institute of Nursing Research, the Stupski Foundation, and the UniHealth Foundation. Dr. Bloem and a colleague reported their institution received a center of excellence grant from the Parkinson’s Foundation.

SOURCE: Kluger B et al. JAMA Neurol. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4992.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Experts bring clarity to end of life difficulties

Understanding family perspective is an important factor

A Vietnam veteran steered clear of the health care system for years, then showed up at the hospital with pneumonia and respiratory failure. He was whisked to the intensive care unit, and cancerous masses were found.

The situation – as described by Jeffrey Frank, MD, director of quality and performance at Vituity, a physician group in Emeryville, Calif. – then got worse.

“No one was there for him,” Dr. Frank said. “He’s laying in the ICU, he does not have the capacity to make decisions, let alone communicate. So the care team needs guidance.”

Too often, hospitalists find themselves in confusing situations involving patients near the end of their lives, having to determine how to go about treating a patient or withholding treatment when patients are not in a position to announce their wishes. When family is present, the health care team thinks the most sensible course of treatment is at odds with what the family wants to be done.

At the Society of Hospital Medicine 2019 Annual Conference, hospitalists with palliative care training offered advice on how to go about handling these difficult situations, which can sometimes become more manageable with certain strategies.

For situations in which there is no designated representative to speak for a patient who is unresponsive – the so-called “unbefriended patient” or “unrepresented patient” – any source of information can be valuable. And health care providers should seek out this input, Dr. Frank said.

“When there is a visitor at the bedside, and as long as they know the person, and they can start giving the medical providers some information about what the patient would have wanted, most of us will talk with that person and that’s actually a good habit,” he said.

Thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia have regulations on whom health care providers should talk to when there is no obvious representative, Dr. Frank said, noting that most of these regulations follow a classic family-tree order. But in the discouraging results of many surveys of health care providers on the subject, most clinicians say that they do not know the regulations in their state, Dr. Frank said. But he said such results betray a silver lining because clinicians say that they would be inclined to use a family tree–style hierarchy in deciding with whom they should speak about end of life decisions.

Hospitalists should at least know whether their hospital has a policy on unrepresented patients, Dr. Frank said.

“That’s your road map on how to get through consenting this patient – what am I going to do with Mr. Smith?” he said. “You may ask yourself, ‘Do I just keep treating him and treating him?’ If you have a policy at your hospital, it will protect you from liability, as well as give you a sense of process.”

Conflicts in communication

An even worse situation, perhaps, is one that many hospitalists have seen: A patient is teetering at the edge of life, and a spouse arrives, along with two daughters from out of state who have not seen their father in a year, said Elizabeth Gundersen, MD, director of the ethics curriculum at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

“The family requests that the medical team do everything, including intubation and attempts at resuscitation if needed,” she said. “The family says he was fine prior to this admission. Another thing I hear a lot is, ‘He was even sicker than this last year, and he got better.’ ”

Meanwhile, “the medical team consensus is that he is not going to survive this illness,” Dr. Gundersen said.

The situation is so common and problematic that it has a name – the “Daughter from California Syndrome.” (According to medical literature says, it’s called the “Daughter from Chicago Syndrome” in California.)

“This is one of the most agonizing things that happens to us in medicine,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It affects us, it affects our nurses, it affects the entire medical team. It’s agonizing when we feel like treatment has somehow turned to torture.”

Dr. Gundersen said the medical staff should avoid using the word “futile,” or similar language, with families.

“Words matter,” she said. “Inappropriate language can inadvertently convey the feeling that, ‘They’re giving up on my dad – they think it’s hopeless.’ That can make families and the medical team dig in their heels further.”

Sometimes it can be hard to define the terms of decision making. Even if the family and the medical team can agree that no “nonbeneficial treatments” should be administered, Dr. Gundersen said, what exactly does that mean? Does it mean less than a 1% chance of working; less than a 5% chance?

If the medical staff thinks a mode of care won’t be effective, but the family still insists, some states have laws that could help the medical team. In Texas, for example, if the medical team thinks the care they’re giving isn’t helping the patient, and the patient is likely going to have a poor outcome, there’s a legal process that the team can go through, Dr. Gundersen said. But even these laws are seen as potentially problematic because of concerns that they put too much power in the hands of a hospital committee.

Dr. Gundersen strongly advised getting at the root causes of a family’s apprehension. They might not have been informed early enough about the dire nature of an illness to feel they can make a decision comfortably. They also may be receiving information in a piecemeal manner or information that is inconsistent. Another common fear expressed by families is a concern over abandonment by the medical team if a decision is made to forgo a certain treatment. Also, sometimes the goals of care might not be properly detailed and discussed, she said.

But better communication can help overcome these snags, Dr. Gundersen said.

She suggested that sometimes it’s helpful to clarify things with the family, for example, what do they mean by “Do everything”?

“Does it mean ‘I want you to do everything to prolong their life even if they suffer,’ or does it mean ‘I want you do to everything that’s reasonable to try to prolong their life but not at the risk of increased suffering,’ or anywhere in between. Really just having these clarifying conversations is helpful.”

She also emphasized the importance of talking about interests, such as not wanting a patient to suffer, instead of taking positions, such as flatly recommending the withdrawal of treatment.

“It’s easy for both sides to kind of dig in their heels and not communicate effectively,” Dr. Gundersen said.

‘Emotional torture’

There are times when, no matter how skillfully the medical team communicates, they stand at an impasse with the family.

“This is emotional torture for us,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It’s moral distress. We kind of dread these situations. In these cases, trying to support yourself and your team emotionally is the most important thing.”

Ami Doshi, MD, director of palliative care inpatient services at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, described the case of a baby girl that touched on the especially painful issues that can arise in pediatric cases. The 2-month-old girl had been born after a pregnancy affected by polyhydramnios and had an abnormal neurological exam and brain MRI, as well as congenital abnormalities. She’d been intubated for respiratory failure and was now on high-flow nasal cannula therapy. The girl was intolerant to feeding and was put on a nasojejunal feeding tube and then a gastrostomy-jejunostomy tube.

But the baby’s vomiting continued, and she had bradycardia and hypoxia so severe she needed bag mask ventilation to recover. The mother started to feel like she was “torturing” the baby.

The family decided to stop respiratory support but to continue artificial nutrition and hydration, which Dr. Doshi said, has an elevated status in the human psyche. Mentioning discontinuing feeding is fraught with complexity, she said.

“The notion of feeding is such a basic instinct, especially with a baby, that tackling the notion of discontinuing any sort of feeds, orally or tube feeds, is fraught with emotion and angst at times,” Dr. Doshi said.

The girl had respiratory events but recovered from them on her own, but the vomiting and retching continued. Eventually the artificial nutrition and hydration was stopped. But after 5 days, the medical staff began feeling uncomfortable, Dr. Doshi said. “We’re starting to hear from nurses, doctors, other people, that something just doesn’t feel right about what’s happening: ‘She seems okay,’ and, ‘Is it really okay for us to be doing this?’ and ‘Gosh, this is taking a long time.’ ”

The medical staff had, in a sense, joined the family on the emotional roller coaster.

Dr. Doshi said it’s important to remember that there is no ethical or moral distinction between withdrawing a medical intervention and withholding one.

“Stopping an intervention once it has started is no different ethically or legally than not starting it in the first place,” she said.

According to Dr. Doshi, there is a general consensus among medical societies that artificial nutrition and hydration is a medical intervention just like any other and that it should be evaluated within the same framework: Is it overly burdensome? Are we doing harm? Is it consistent with the goal of care? In so doing, be sure to respect patient autonomy and obtain informed consent.

As with so much in medicine, careful communication is a must.

“Paint a picture of what the patient’s trajectory is going to look like with and without artificial nutrition and hydration. At the end of the day, having done all of that, we’re going to ultimately respect what the patient or the surrogate decision maker decides,” Dr. Doshi said.

After assessment the data and the chances of success, and still without clarity about how to proceed, a good option might be considering a “time-limited trial” in which the medical team sits with the family and agrees on a time frame for an intervention and chooses predetermined endpoints for assessing success or failure.

“This can be very powerful to help us understand whether it is beneficial, but also – from the family’s perspective – to know everything was tried,” Dr. Doshi said.

Hospitalists should emphasize what is being added to treatment so that families don’t think only of what is being taken away, she said.

“Usually we are adding a lot – symptom management, a lot of psychosocial support. So what are all the other ways that we’re going to continue to care for the patient, even when we are withdrawing or withholding a specific intervention?” Dr. Doshi noted.

Sometimes, the best healer of distress in the midst of end of life decision making is time itself, Dr. Gundersen said.

In a condolence call, she once spoke with a family member involved in an agonizing case in which the medical team and family were at odds. Yet the man told her: “I know that you all were telling us the entire time that this was going to happen, but I guess we just had to go through our own process.”

Understanding family perspective is an important factor

Understanding family perspective is an important factor

A Vietnam veteran steered clear of the health care system for years, then showed up at the hospital with pneumonia and respiratory failure. He was whisked to the intensive care unit, and cancerous masses were found.

The situation – as described by Jeffrey Frank, MD, director of quality and performance at Vituity, a physician group in Emeryville, Calif. – then got worse.

“No one was there for him,” Dr. Frank said. “He’s laying in the ICU, he does not have the capacity to make decisions, let alone communicate. So the care team needs guidance.”

Too often, hospitalists find themselves in confusing situations involving patients near the end of their lives, having to determine how to go about treating a patient or withholding treatment when patients are not in a position to announce their wishes. When family is present, the health care team thinks the most sensible course of treatment is at odds with what the family wants to be done.

At the Society of Hospital Medicine 2019 Annual Conference, hospitalists with palliative care training offered advice on how to go about handling these difficult situations, which can sometimes become more manageable with certain strategies.

For situations in which there is no designated representative to speak for a patient who is unresponsive – the so-called “unbefriended patient” or “unrepresented patient” – any source of information can be valuable. And health care providers should seek out this input, Dr. Frank said.

“When there is a visitor at the bedside, and as long as they know the person, and they can start giving the medical providers some information about what the patient would have wanted, most of us will talk with that person and that’s actually a good habit,” he said.

Thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia have regulations on whom health care providers should talk to when there is no obvious representative, Dr. Frank said, noting that most of these regulations follow a classic family-tree order. But in the discouraging results of many surveys of health care providers on the subject, most clinicians say that they do not know the regulations in their state, Dr. Frank said. But he said such results betray a silver lining because clinicians say that they would be inclined to use a family tree–style hierarchy in deciding with whom they should speak about end of life decisions.

Hospitalists should at least know whether their hospital has a policy on unrepresented patients, Dr. Frank said.

“That’s your road map on how to get through consenting this patient – what am I going to do with Mr. Smith?” he said. “You may ask yourself, ‘Do I just keep treating him and treating him?’ If you have a policy at your hospital, it will protect you from liability, as well as give you a sense of process.”

Conflicts in communication

An even worse situation, perhaps, is one that many hospitalists have seen: A patient is teetering at the edge of life, and a spouse arrives, along with two daughters from out of state who have not seen their father in a year, said Elizabeth Gundersen, MD, director of the ethics curriculum at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

“The family requests that the medical team do everything, including intubation and attempts at resuscitation if needed,” she said. “The family says he was fine prior to this admission. Another thing I hear a lot is, ‘He was even sicker than this last year, and he got better.’ ”

Meanwhile, “the medical team consensus is that he is not going to survive this illness,” Dr. Gundersen said.

The situation is so common and problematic that it has a name – the “Daughter from California Syndrome.” (According to medical literature says, it’s called the “Daughter from Chicago Syndrome” in California.)

“This is one of the most agonizing things that happens to us in medicine,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It affects us, it affects our nurses, it affects the entire medical team. It’s agonizing when we feel like treatment has somehow turned to torture.”

Dr. Gundersen said the medical staff should avoid using the word “futile,” or similar language, with families.

“Words matter,” she said. “Inappropriate language can inadvertently convey the feeling that, ‘They’re giving up on my dad – they think it’s hopeless.’ That can make families and the medical team dig in their heels further.”

Sometimes it can be hard to define the terms of decision making. Even if the family and the medical team can agree that no “nonbeneficial treatments” should be administered, Dr. Gundersen said, what exactly does that mean? Does it mean less than a 1% chance of working; less than a 5% chance?

If the medical staff thinks a mode of care won’t be effective, but the family still insists, some states have laws that could help the medical team. In Texas, for example, if the medical team thinks the care they’re giving isn’t helping the patient, and the patient is likely going to have a poor outcome, there’s a legal process that the team can go through, Dr. Gundersen said. But even these laws are seen as potentially problematic because of concerns that they put too much power in the hands of a hospital committee.

Dr. Gundersen strongly advised getting at the root causes of a family’s apprehension. They might not have been informed early enough about the dire nature of an illness to feel they can make a decision comfortably. They also may be receiving information in a piecemeal manner or information that is inconsistent. Another common fear expressed by families is a concern over abandonment by the medical team if a decision is made to forgo a certain treatment. Also, sometimes the goals of care might not be properly detailed and discussed, she said.

But better communication can help overcome these snags, Dr. Gundersen said.

She suggested that sometimes it’s helpful to clarify things with the family, for example, what do they mean by “Do everything”?

“Does it mean ‘I want you to do everything to prolong their life even if they suffer,’ or does it mean ‘I want you do to everything that’s reasonable to try to prolong their life but not at the risk of increased suffering,’ or anywhere in between. Really just having these clarifying conversations is helpful.”

She also emphasized the importance of talking about interests, such as not wanting a patient to suffer, instead of taking positions, such as flatly recommending the withdrawal of treatment.

“It’s easy for both sides to kind of dig in their heels and not communicate effectively,” Dr. Gundersen said.

‘Emotional torture’

There are times when, no matter how skillfully the medical team communicates, they stand at an impasse with the family.

“This is emotional torture for us,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It’s moral distress. We kind of dread these situations. In these cases, trying to support yourself and your team emotionally is the most important thing.”

Ami Doshi, MD, director of palliative care inpatient services at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, described the case of a baby girl that touched on the especially painful issues that can arise in pediatric cases. The 2-month-old girl had been born after a pregnancy affected by polyhydramnios and had an abnormal neurological exam and brain MRI, as well as congenital abnormalities. She’d been intubated for respiratory failure and was now on high-flow nasal cannula therapy. The girl was intolerant to feeding and was put on a nasojejunal feeding tube and then a gastrostomy-jejunostomy tube.

But the baby’s vomiting continued, and she had bradycardia and hypoxia so severe she needed bag mask ventilation to recover. The mother started to feel like she was “torturing” the baby.

The family decided to stop respiratory support but to continue artificial nutrition and hydration, which Dr. Doshi said, has an elevated status in the human psyche. Mentioning discontinuing feeding is fraught with complexity, she said.

“The notion of feeding is such a basic instinct, especially with a baby, that tackling the notion of discontinuing any sort of feeds, orally or tube feeds, is fraught with emotion and angst at times,” Dr. Doshi said.

The girl had respiratory events but recovered from them on her own, but the vomiting and retching continued. Eventually the artificial nutrition and hydration was stopped. But after 5 days, the medical staff began feeling uncomfortable, Dr. Doshi said. “We’re starting to hear from nurses, doctors, other people, that something just doesn’t feel right about what’s happening: ‘She seems okay,’ and, ‘Is it really okay for us to be doing this?’ and ‘Gosh, this is taking a long time.’ ”

The medical staff had, in a sense, joined the family on the emotional roller coaster.

Dr. Doshi said it’s important to remember that there is no ethical or moral distinction between withdrawing a medical intervention and withholding one.

“Stopping an intervention once it has started is no different ethically or legally than not starting it in the first place,” she said.

According to Dr. Doshi, there is a general consensus among medical societies that artificial nutrition and hydration is a medical intervention just like any other and that it should be evaluated within the same framework: Is it overly burdensome? Are we doing harm? Is it consistent with the goal of care? In so doing, be sure to respect patient autonomy and obtain informed consent.

As with so much in medicine, careful communication is a must.

“Paint a picture of what the patient’s trajectory is going to look like with and without artificial nutrition and hydration. At the end of the day, having done all of that, we’re going to ultimately respect what the patient or the surrogate decision maker decides,” Dr. Doshi said.

After assessment the data and the chances of success, and still without clarity about how to proceed, a good option might be considering a “time-limited trial” in which the medical team sits with the family and agrees on a time frame for an intervention and chooses predetermined endpoints for assessing success or failure.

“This can be very powerful to help us understand whether it is beneficial, but also – from the family’s perspective – to know everything was tried,” Dr. Doshi said.

Hospitalists should emphasize what is being added to treatment so that families don’t think only of what is being taken away, she said.

“Usually we are adding a lot – symptom management, a lot of psychosocial support. So what are all the other ways that we’re going to continue to care for the patient, even when we are withdrawing or withholding a specific intervention?” Dr. Doshi noted.

Sometimes, the best healer of distress in the midst of end of life decision making is time itself, Dr. Gundersen said.

In a condolence call, she once spoke with a family member involved in an agonizing case in which the medical team and family were at odds. Yet the man told her: “I know that you all were telling us the entire time that this was going to happen, but I guess we just had to go through our own process.”

A Vietnam veteran steered clear of the health care system for years, then showed up at the hospital with pneumonia and respiratory failure. He was whisked to the intensive care unit, and cancerous masses were found.

The situation – as described by Jeffrey Frank, MD, director of quality and performance at Vituity, a physician group in Emeryville, Calif. – then got worse.

“No one was there for him,” Dr. Frank said. “He’s laying in the ICU, he does not have the capacity to make decisions, let alone communicate. So the care team needs guidance.”

Too often, hospitalists find themselves in confusing situations involving patients near the end of their lives, having to determine how to go about treating a patient or withholding treatment when patients are not in a position to announce their wishes. When family is present, the health care team thinks the most sensible course of treatment is at odds with what the family wants to be done.

At the Society of Hospital Medicine 2019 Annual Conference, hospitalists with palliative care training offered advice on how to go about handling these difficult situations, which can sometimes become more manageable with certain strategies.

For situations in which there is no designated representative to speak for a patient who is unresponsive – the so-called “unbefriended patient” or “unrepresented patient” – any source of information can be valuable. And health care providers should seek out this input, Dr. Frank said.

“When there is a visitor at the bedside, and as long as they know the person, and they can start giving the medical providers some information about what the patient would have wanted, most of us will talk with that person and that’s actually a good habit,” he said.

Thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia have regulations on whom health care providers should talk to when there is no obvious representative, Dr. Frank said, noting that most of these regulations follow a classic family-tree order. But in the discouraging results of many surveys of health care providers on the subject, most clinicians say that they do not know the regulations in their state, Dr. Frank said. But he said such results betray a silver lining because clinicians say that they would be inclined to use a family tree–style hierarchy in deciding with whom they should speak about end of life decisions.

Hospitalists should at least know whether their hospital has a policy on unrepresented patients, Dr. Frank said.

“That’s your road map on how to get through consenting this patient – what am I going to do with Mr. Smith?” he said. “You may ask yourself, ‘Do I just keep treating him and treating him?’ If you have a policy at your hospital, it will protect you from liability, as well as give you a sense of process.”

Conflicts in communication

An even worse situation, perhaps, is one that many hospitalists have seen: A patient is teetering at the edge of life, and a spouse arrives, along with two daughters from out of state who have not seen their father in a year, said Elizabeth Gundersen, MD, director of the ethics curriculum at Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

“The family requests that the medical team do everything, including intubation and attempts at resuscitation if needed,” she said. “The family says he was fine prior to this admission. Another thing I hear a lot is, ‘He was even sicker than this last year, and he got better.’ ”

Meanwhile, “the medical team consensus is that he is not going to survive this illness,” Dr. Gundersen said.

The situation is so common and problematic that it has a name – the “Daughter from California Syndrome.” (According to medical literature says, it’s called the “Daughter from Chicago Syndrome” in California.)

“This is one of the most agonizing things that happens to us in medicine,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It affects us, it affects our nurses, it affects the entire medical team. It’s agonizing when we feel like treatment has somehow turned to torture.”

Dr. Gundersen said the medical staff should avoid using the word “futile,” or similar language, with families.

“Words matter,” she said. “Inappropriate language can inadvertently convey the feeling that, ‘They’re giving up on my dad – they think it’s hopeless.’ That can make families and the medical team dig in their heels further.”

Sometimes it can be hard to define the terms of decision making. Even if the family and the medical team can agree that no “nonbeneficial treatments” should be administered, Dr. Gundersen said, what exactly does that mean? Does it mean less than a 1% chance of working; less than a 5% chance?

If the medical staff thinks a mode of care won’t be effective, but the family still insists, some states have laws that could help the medical team. In Texas, for example, if the medical team thinks the care they’re giving isn’t helping the patient, and the patient is likely going to have a poor outcome, there’s a legal process that the team can go through, Dr. Gundersen said. But even these laws are seen as potentially problematic because of concerns that they put too much power in the hands of a hospital committee.

Dr. Gundersen strongly advised getting at the root causes of a family’s apprehension. They might not have been informed early enough about the dire nature of an illness to feel they can make a decision comfortably. They also may be receiving information in a piecemeal manner or information that is inconsistent. Another common fear expressed by families is a concern over abandonment by the medical team if a decision is made to forgo a certain treatment. Also, sometimes the goals of care might not be properly detailed and discussed, she said.

But better communication can help overcome these snags, Dr. Gundersen said.

She suggested that sometimes it’s helpful to clarify things with the family, for example, what do they mean by “Do everything”?

“Does it mean ‘I want you to do everything to prolong their life even if they suffer,’ or does it mean ‘I want you do to everything that’s reasonable to try to prolong their life but not at the risk of increased suffering,’ or anywhere in between. Really just having these clarifying conversations is helpful.”

She also emphasized the importance of talking about interests, such as not wanting a patient to suffer, instead of taking positions, such as flatly recommending the withdrawal of treatment.

“It’s easy for both sides to kind of dig in their heels and not communicate effectively,” Dr. Gundersen said.

‘Emotional torture’

There are times when, no matter how skillfully the medical team communicates, they stand at an impasse with the family.

“This is emotional torture for us,” Dr. Gundersen said. “It’s moral distress. We kind of dread these situations. In these cases, trying to support yourself and your team emotionally is the most important thing.”

Ami Doshi, MD, director of palliative care inpatient services at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego, described the case of a baby girl that touched on the especially painful issues that can arise in pediatric cases. The 2-month-old girl had been born after a pregnancy affected by polyhydramnios and had an abnormal neurological exam and brain MRI, as well as congenital abnormalities. She’d been intubated for respiratory failure and was now on high-flow nasal cannula therapy. The girl was intolerant to feeding and was put on a nasojejunal feeding tube and then a gastrostomy-jejunostomy tube.

But the baby’s vomiting continued, and she had bradycardia and hypoxia so severe she needed bag mask ventilation to recover. The mother started to feel like she was “torturing” the baby.

The family decided to stop respiratory support but to continue artificial nutrition and hydration, which Dr. Doshi said, has an elevated status in the human psyche. Mentioning discontinuing feeding is fraught with complexity, she said.

“The notion of feeding is such a basic instinct, especially with a baby, that tackling the notion of discontinuing any sort of feeds, orally or tube feeds, is fraught with emotion and angst at times,” Dr. Doshi said.

The girl had respiratory events but recovered from them on her own, but the vomiting and retching continued. Eventually the artificial nutrition and hydration was stopped. But after 5 days, the medical staff began feeling uncomfortable, Dr. Doshi said. “We’re starting to hear from nurses, doctors, other people, that something just doesn’t feel right about what’s happening: ‘She seems okay,’ and, ‘Is it really okay for us to be doing this?’ and ‘Gosh, this is taking a long time.’ ”

The medical staff had, in a sense, joined the family on the emotional roller coaster.

Dr. Doshi said it’s important to remember that there is no ethical or moral distinction between withdrawing a medical intervention and withholding one.

“Stopping an intervention once it has started is no different ethically or legally than not starting it in the first place,” she said.

According to Dr. Doshi, there is a general consensus among medical societies that artificial nutrition and hydration is a medical intervention just like any other and that it should be evaluated within the same framework: Is it overly burdensome? Are we doing harm? Is it consistent with the goal of care? In so doing, be sure to respect patient autonomy and obtain informed consent.

As with so much in medicine, careful communication is a must.

“Paint a picture of what the patient’s trajectory is going to look like with and without artificial nutrition and hydration. At the end of the day, having done all of that, we’re going to ultimately respect what the patient or the surrogate decision maker decides,” Dr. Doshi said.

After assessment the data and the chances of success, and still without clarity about how to proceed, a good option might be considering a “time-limited trial” in which the medical team sits with the family and agrees on a time frame for an intervention and chooses predetermined endpoints for assessing success or failure.

“This can be very powerful to help us understand whether it is beneficial, but also – from the family’s perspective – to know everything was tried,” Dr. Doshi said.

Hospitalists should emphasize what is being added to treatment so that families don’t think only of what is being taken away, she said.

“Usually we are adding a lot – symptom management, a lot of psychosocial support. So what are all the other ways that we’re going to continue to care for the patient, even when we are withdrawing or withholding a specific intervention?” Dr. Doshi noted.

Sometimes, the best healer of distress in the midst of end of life decision making is time itself, Dr. Gundersen said.

In a condolence call, she once spoke with a family member involved in an agonizing case in which the medical team and family were at odds. Yet the man told her: “I know that you all were telling us the entire time that this was going to happen, but I guess we just had to go through our own process.”

Storytelling tool can assist elderly in the ICU

SAN FRANCISCO – A “Best Case/Worst Case” (BCWC) framework tool has been adapted for use with geriatric trauma patients in the ICU, where it can help track a patient’s progress and enable better communication with patients and loved ones. The tool relies on a combination of graphics and text that surgeons update daily during rounds, and creates a longitudinal view of a patient’s trajectory during their stay in the ICU.

– for example, after a complication has arisen.

“Each day during rounds, the ICU team records important events on the graphic aid that change the patient’s course. The team draws a star to represent the best case, and a line to represent prognostic uncertainty. The attending trauma surgeon then uses the geriatric trauma outcome score, their knowledge of the health state of the patient, and their own clinical experience to tell a story about treatments, recovery, and outcomes if everything goes as well as we might hope. This story is written down in the best-case scenario box,” Christopher Zimmerman, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said during a presentation about the BCWC tool at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons

“We often like to talk to patients and their families [about best- and worst-case scenarios] anyway, but [the research team] have tried to formalize it,” said Tam Pham, MD, professor of surgery at the University of Washington, in an interview. Dr. Pham comoderated the session where the research was presented.

“When we’re able to communicate where the uncertainty is and where the boundaries are around the course of care and possible outcomes, we can build an alliance with patients and families that will be helpful when there is a big decision to make, say about a laparotomy for a perforated viscus,” said Dr. Zimmerman.

Dr. Zimmerman gave an example of a patient who came into the ICU after suffering multiple fractures from falling down a set of stairs. The team created an initial BCWC with a hoped-for best-case scenario. Later, the patient developed hypoxemic respiratory failure and had to be intubated overnight. “This event is recorded on the graphic, and her star representing the best case has changed position, the line representing uncertainty has shortened, and the contents of her best-case scenario has changed. Each day in rounds, this process is repeated,” said Dr. Zimmerman.

Palliative care physicians, education experts, and surgeons at the University of Wisconsin–Madison developed the tool in an effort to reduce unwanted care at the end of life, in the context of high-risk surgeries. The researchers adapted the tool to the trauma setting by gathering six focus groups of trauma practitioners at the University of Wisconsin; University of Texas, Dallas; and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. They modified the tool after incorporating comments, and then iteratively modified it through tasks carried out in the ICU as part of a qualitative improvement initiative at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. They generated a change to the tool, implemented it in the ICU during subsequent rounds, then collected observations and field notes, then revised and repeated the process, streamlining it to fit into the ICU environment, according to Dr. Zimmerman.

The back side of the tool is available for family members to write important details about their loved ones, leading insight into the patient’s personality and desires, such as favorite music or affection for a family pet.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zimmerman and Dr. Pham have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zimmerman C et al. Clinical Congress 2019, Abstract.

SAN FRANCISCO – A “Best Case/Worst Case” (BCWC) framework tool has been adapted for use with geriatric trauma patients in the ICU, where it can help track a patient’s progress and enable better communication with patients and loved ones. The tool relies on a combination of graphics and text that surgeons update daily during rounds, and creates a longitudinal view of a patient’s trajectory during their stay in the ICU.

– for example, after a complication has arisen.

“Each day during rounds, the ICU team records important events on the graphic aid that change the patient’s course. The team draws a star to represent the best case, and a line to represent prognostic uncertainty. The attending trauma surgeon then uses the geriatric trauma outcome score, their knowledge of the health state of the patient, and their own clinical experience to tell a story about treatments, recovery, and outcomes if everything goes as well as we might hope. This story is written down in the best-case scenario box,” Christopher Zimmerman, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said during a presentation about the BCWC tool at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons

“We often like to talk to patients and their families [about best- and worst-case scenarios] anyway, but [the research team] have tried to formalize it,” said Tam Pham, MD, professor of surgery at the University of Washington, in an interview. Dr. Pham comoderated the session where the research was presented.

“When we’re able to communicate where the uncertainty is and where the boundaries are around the course of care and possible outcomes, we can build an alliance with patients and families that will be helpful when there is a big decision to make, say about a laparotomy for a perforated viscus,” said Dr. Zimmerman.

Dr. Zimmerman gave an example of a patient who came into the ICU after suffering multiple fractures from falling down a set of stairs. The team created an initial BCWC with a hoped-for best-case scenario. Later, the patient developed hypoxemic respiratory failure and had to be intubated overnight. “This event is recorded on the graphic, and her star representing the best case has changed position, the line representing uncertainty has shortened, and the contents of her best-case scenario has changed. Each day in rounds, this process is repeated,” said Dr. Zimmerman.

Palliative care physicians, education experts, and surgeons at the University of Wisconsin–Madison developed the tool in an effort to reduce unwanted care at the end of life, in the context of high-risk surgeries. The researchers adapted the tool to the trauma setting by gathering six focus groups of trauma practitioners at the University of Wisconsin; University of Texas, Dallas; and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. They modified the tool after incorporating comments, and then iteratively modified it through tasks carried out in the ICU as part of a qualitative improvement initiative at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. They generated a change to the tool, implemented it in the ICU during subsequent rounds, then collected observations and field notes, then revised and repeated the process, streamlining it to fit into the ICU environment, according to Dr. Zimmerman.

The back side of the tool is available for family members to write important details about their loved ones, leading insight into the patient’s personality and desires, such as favorite music or affection for a family pet.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zimmerman and Dr. Pham have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zimmerman C et al. Clinical Congress 2019, Abstract.

SAN FRANCISCO – A “Best Case/Worst Case” (BCWC) framework tool has been adapted for use with geriatric trauma patients in the ICU, where it can help track a patient’s progress and enable better communication with patients and loved ones. The tool relies on a combination of graphics and text that surgeons update daily during rounds, and creates a longitudinal view of a patient’s trajectory during their stay in the ICU.

– for example, after a complication has arisen.

“Each day during rounds, the ICU team records important events on the graphic aid that change the patient’s course. The team draws a star to represent the best case, and a line to represent prognostic uncertainty. The attending trauma surgeon then uses the geriatric trauma outcome score, their knowledge of the health state of the patient, and their own clinical experience to tell a story about treatments, recovery, and outcomes if everything goes as well as we might hope. This story is written down in the best-case scenario box,” Christopher Zimmerman, MD, a general surgery resident at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said during a presentation about the BCWC tool at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons

“We often like to talk to patients and their families [about best- and worst-case scenarios] anyway, but [the research team] have tried to formalize it,” said Tam Pham, MD, professor of surgery at the University of Washington, in an interview. Dr. Pham comoderated the session where the research was presented.

“When we’re able to communicate where the uncertainty is and where the boundaries are around the course of care and possible outcomes, we can build an alliance with patients and families that will be helpful when there is a big decision to make, say about a laparotomy for a perforated viscus,” said Dr. Zimmerman.

Dr. Zimmerman gave an example of a patient who came into the ICU after suffering multiple fractures from falling down a set of stairs. The team created an initial BCWC with a hoped-for best-case scenario. Later, the patient developed hypoxemic respiratory failure and had to be intubated overnight. “This event is recorded on the graphic, and her star representing the best case has changed position, the line representing uncertainty has shortened, and the contents of her best-case scenario has changed. Each day in rounds, this process is repeated,” said Dr. Zimmerman.

Palliative care physicians, education experts, and surgeons at the University of Wisconsin–Madison developed the tool in an effort to reduce unwanted care at the end of life, in the context of high-risk surgeries. The researchers adapted the tool to the trauma setting by gathering six focus groups of trauma practitioners at the University of Wisconsin; University of Texas, Dallas; and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. They modified the tool after incorporating comments, and then iteratively modified it through tasks carried out in the ICU as part of a qualitative improvement initiative at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. They generated a change to the tool, implemented it in the ICU during subsequent rounds, then collected observations and field notes, then revised and repeated the process, streamlining it to fit into the ICU environment, according to Dr. Zimmerman.

The back side of the tool is available for family members to write important details about their loved ones, leading insight into the patient’s personality and desires, such as favorite music or affection for a family pet.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zimmerman and Dr. Pham have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zimmerman C et al. Clinical Congress 2019, Abstract.

REPORTING FROM CLINICAL CONGRESS 2019

Early palliative care consult decreases in-hospital mortality

NEW ORLEANS – When initiated early, meeting certain end-of-life criteria, results of a recent randomized clinical trial suggest.

The rate of in-hospital mortality was lower for critical care patients receiving an early consultation, compared with those who received palliative care initiated according to usual standards in the randomized, controlled trial, described at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In addition, more health care surrogates were chosen in the hospital when palliative care medicine was involved earlier, according to investigator Scott Helgeson, MD, fellow in pulmonary critical care at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

Taken together, Dr. Helgeson said, those findings suggest the importance of getting palliative care involved “very early, while the patient can still make decisions.”

“There are a lot of things that can get in the way of adequate conversations, and that’s when the palliative care team can come in,” Dr. Helgeson said in an interview.

This study is the first reported to date to look at the impact on patient care outcomes specifically within 24 hours of medical ICU admission, according to Dr. Helgeson and coinvestigators

In their randomized study, patients were eligible if they met at least one of several criteria, including advanced age (80 years or older), late-stage dementia, post–cardiac arrest, metastatic cancer, end-stage organ failure, recurrent ICU admissions, an APACHE II score of 14 or higher, a SOFA score of 9 or higher, preexisting functional dependency, or consideration for a tracheostomy or permanent feeding tube.

Of 29 patients randomized, 14 received early palliative care, and 15 received standard palliative care, which was defined as starting “whenever the treating team deems (it) is appropriate,” according to the published abstract.

Hospital mortality occurred in none of the patients in the early palliative care group, versus six in the usual care group (P = .01), Dr. Helgeson and colleagues found. Moreover, seven health care surrogates were chosen in hospital in the early palliative care group, versus none in the usual care group (P less than .01).

Length of stay in the ICU or in hospital did not vary by treatment group, according to the investigators.

About one-fifth of deaths in the United States take place in or around ICU admissions, according to the investigators, who noted that those admissions can result in changing goals from cure to comfort – though sometimes too late.

Dr. Helgeson and coauthors disclosed that they had no relationships relevant to this research presentation.

SOURCE: Helgeson S, et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.803.

NEW ORLEANS – When initiated early, meeting certain end-of-life criteria, results of a recent randomized clinical trial suggest.

The rate of in-hospital mortality was lower for critical care patients receiving an early consultation, compared with those who received palliative care initiated according to usual standards in the randomized, controlled trial, described at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In addition, more health care surrogates were chosen in the hospital when palliative care medicine was involved earlier, according to investigator Scott Helgeson, MD, fellow in pulmonary critical care at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

Taken together, Dr. Helgeson said, those findings suggest the importance of getting palliative care involved “very early, while the patient can still make decisions.”

“There are a lot of things that can get in the way of adequate conversations, and that’s when the palliative care team can come in,” Dr. Helgeson said in an interview.

This study is the first reported to date to look at the impact on patient care outcomes specifically within 24 hours of medical ICU admission, according to Dr. Helgeson and coinvestigators

In their randomized study, patients were eligible if they met at least one of several criteria, including advanced age (80 years or older), late-stage dementia, post–cardiac arrest, metastatic cancer, end-stage organ failure, recurrent ICU admissions, an APACHE II score of 14 or higher, a SOFA score of 9 or higher, preexisting functional dependency, or consideration for a tracheostomy or permanent feeding tube.

Of 29 patients randomized, 14 received early palliative care, and 15 received standard palliative care, which was defined as starting “whenever the treating team deems (it) is appropriate,” according to the published abstract.

Hospital mortality occurred in none of the patients in the early palliative care group, versus six in the usual care group (P = .01), Dr. Helgeson and colleagues found. Moreover, seven health care surrogates were chosen in hospital in the early palliative care group, versus none in the usual care group (P less than .01).

Length of stay in the ICU or in hospital did not vary by treatment group, according to the investigators.

About one-fifth of deaths in the United States take place in or around ICU admissions, according to the investigators, who noted that those admissions can result in changing goals from cure to comfort – though sometimes too late.

Dr. Helgeson and coauthors disclosed that they had no relationships relevant to this research presentation.

SOURCE: Helgeson S, et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.803.

NEW ORLEANS – When initiated early, meeting certain end-of-life criteria, results of a recent randomized clinical trial suggest.

The rate of in-hospital mortality was lower for critical care patients receiving an early consultation, compared with those who received palliative care initiated according to usual standards in the randomized, controlled trial, described at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

In addition, more health care surrogates were chosen in the hospital when palliative care medicine was involved earlier, according to investigator Scott Helgeson, MD, fellow in pulmonary critical care at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

Taken together, Dr. Helgeson said, those findings suggest the importance of getting palliative care involved “very early, while the patient can still make decisions.”

“There are a lot of things that can get in the way of adequate conversations, and that’s when the palliative care team can come in,” Dr. Helgeson said in an interview.

This study is the first reported to date to look at the impact on patient care outcomes specifically within 24 hours of medical ICU admission, according to Dr. Helgeson and coinvestigators

In their randomized study, patients were eligible if they met at least one of several criteria, including advanced age (80 years or older), late-stage dementia, post–cardiac arrest, metastatic cancer, end-stage organ failure, recurrent ICU admissions, an APACHE II score of 14 or higher, a SOFA score of 9 or higher, preexisting functional dependency, or consideration for a tracheostomy or permanent feeding tube.

Of 29 patients randomized, 14 received early palliative care, and 15 received standard palliative care, which was defined as starting “whenever the treating team deems (it) is appropriate,” according to the published abstract.

Hospital mortality occurred in none of the patients in the early palliative care group, versus six in the usual care group (P = .01), Dr. Helgeson and colleagues found. Moreover, seven health care surrogates were chosen in hospital in the early palliative care group, versus none in the usual care group (P less than .01).

Length of stay in the ICU or in hospital did not vary by treatment group, according to the investigators.

About one-fifth of deaths in the United States take place in or around ICU admissions, according to the investigators, who noted that those admissions can result in changing goals from cure to comfort – though sometimes too late.

Dr. Helgeson and coauthors disclosed that they had no relationships relevant to this research presentation.

SOURCE: Helgeson S, et al. CHEST 2019. Abstract, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.803.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2019

Palliative care programs continue growth in U.S. hospitals

Growth continues among palliative care programs in the United States, although access often depends “more upon accidents of geography than it does upon the needs of patients,” according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

“As is true for many aspects of health care, geography is destiny. Where you live determines your access to the best quality of life and highest quality of care during a serious illness,” said Diane E. Meier, MD, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in a written statement.

the two organizations said in their 2019 report card on palliative care access. What hasn’t changed since 2015, however, is the country’s overall grade, which remains a B.

Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have a palliative care program in all of their hospitals with 50 or more beds and each earned a grade of A (palliative care rate of greater than 80%), along with 17 other states. The lowest-performing states – Alabama, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – all received Ds for having a rate below 40%, the CAPC said.

The urban/rural divide also is prominent in palliative care: “90% of hospitals with palliative care are in urban areas. Only 17% of rural hospitals with fifty or more beds report palliative care programs,” the report said.

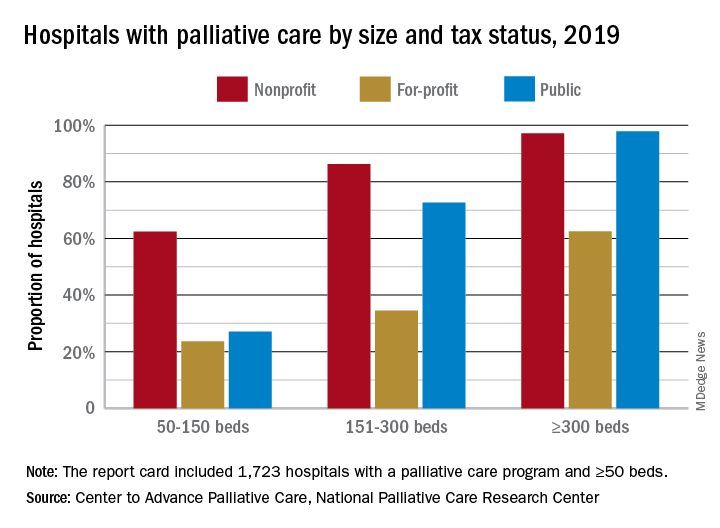

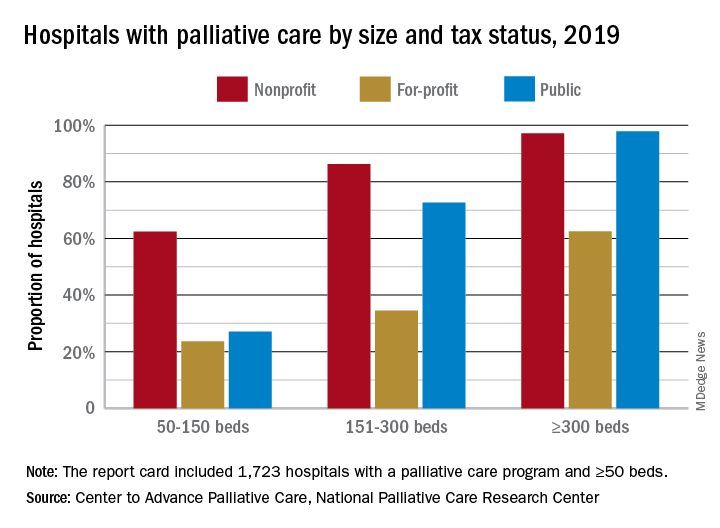

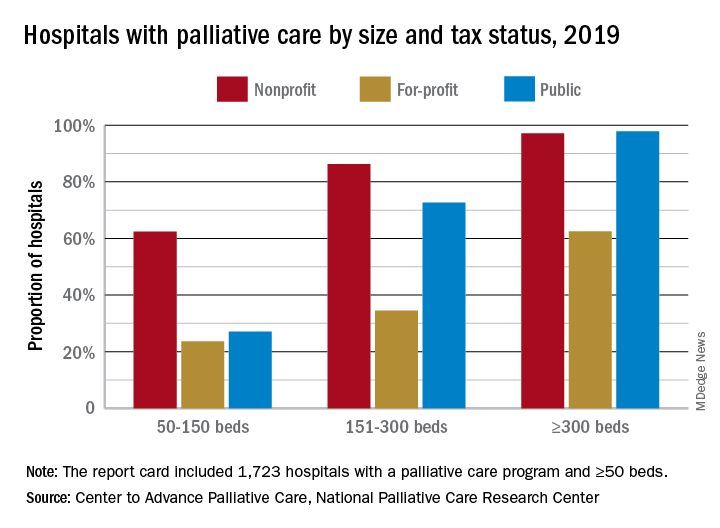

Hospital type is another source of disparity. Small, nonprofit hospitals are much more likely to offer access to palliative care than either for-profit or public facilities of the same size, but the gap closes as size increases, at least between nonprofit and public hospitals. For the largest institutions, the public hospitals pull into the lead, 98% versus 97%, over the nonprofits, with the for-profit facilities well behind at 63%.

“High quality palliative care has been shown to improve patient and family quality of life, improve patients’ and families’ health care experiences, and in certain diseases, prolong life. Palliative care has also been shown to improve hospital efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending,” said R. Sean Morrison, MD, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center.

The report card is based on data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey Database, with additional data from the National Palliative Care Registry and Center to Advance Palliative Care’s Mapping Community Palliative Care initiative. The final sample included 2,409 hospitals with 50 or more beds.

Growth continues among palliative care programs in the United States, although access often depends “more upon accidents of geography than it does upon the needs of patients,” according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

“As is true for many aspects of health care, geography is destiny. Where you live determines your access to the best quality of life and highest quality of care during a serious illness,” said Diane E. Meier, MD, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in a written statement.

the two organizations said in their 2019 report card on palliative care access. What hasn’t changed since 2015, however, is the country’s overall grade, which remains a B.

Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have a palliative care program in all of their hospitals with 50 or more beds and each earned a grade of A (palliative care rate of greater than 80%), along with 17 other states. The lowest-performing states – Alabama, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – all received Ds for having a rate below 40%, the CAPC said.

The urban/rural divide also is prominent in palliative care: “90% of hospitals with palliative care are in urban areas. Only 17% of rural hospitals with fifty or more beds report palliative care programs,” the report said.

Hospital type is another source of disparity. Small, nonprofit hospitals are much more likely to offer access to palliative care than either for-profit or public facilities of the same size, but the gap closes as size increases, at least between nonprofit and public hospitals. For the largest institutions, the public hospitals pull into the lead, 98% versus 97%, over the nonprofits, with the for-profit facilities well behind at 63%.

“High quality palliative care has been shown to improve patient and family quality of life, improve patients’ and families’ health care experiences, and in certain diseases, prolong life. Palliative care has also been shown to improve hospital efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending,” said R. Sean Morrison, MD, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center.

The report card is based on data from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey Database, with additional data from the National Palliative Care Registry and Center to Advance Palliative Care’s Mapping Community Palliative Care initiative. The final sample included 2,409 hospitals with 50 or more beds.

Growth continues among palliative care programs in the United States, although access often depends “more upon accidents of geography than it does upon the needs of patients,” according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center.

“As is true for many aspects of health care, geography is destiny. Where you live determines your access to the best quality of life and highest quality of care during a serious illness,” said Diane E. Meier, MD, director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, in a written statement.

the two organizations said in their 2019 report card on palliative care access. What hasn’t changed since 2015, however, is the country’s overall grade, which remains a B.

Delaware, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have a palliative care program in all of their hospitals with 50 or more beds and each earned a grade of A (palliative care rate of greater than 80%), along with 17 other states. The lowest-performing states – Alabama, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming – all received Ds for having a rate below 40%, the CAPC said.

The urban/rural divide also is prominent in palliative care: “90% of hospitals with palliative care are in urban areas. Only 17% of rural hospitals with fifty or more beds report palliative care programs,” the report said.

Hospital type is another source of disparity. Small, nonprofit hospitals are much more likely to offer access to palliative care than either for-profit or public facilities of the same size, but the gap closes as size increases, at least between nonprofit and public hospitals. For the largest institutions, the public hospitals pull into the lead, 98% versus 97%, over the nonprofits, with the for-profit facilities well behind at 63%.

“High quality palliative care has been shown to improve patient and family quality of life, improve patients’ and families’ health care experiences, and in certain diseases, prolong life. Palliative care has also been shown to improve hospital efficiency and reduce unnecessary spending,” said R. Sean Morrison, MD, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center.