User login

The Impact of End of Life Chemotherapy on Quality of Life and Life Expectancy

Background: A majority of end-stage cancer patients are receiving chemotherapy, regardless of performance status, in the last months of life. Oncologists continue to prescribe disease targeted therapy for patients enrolled in palliative or hospice care in an attempt to alleviate symptoms and extend life expectancy. Research indicates that chemotherapy at end of life does not accomplish either of these goals of care, and may actually do more harm than good.

Methods: An evidence based research review indicates that > 50% of all cancer patients are receiving chemotherapy during their last 4-6 months of life. Data supports a decreased quality of life and decreased life expectancy for patients receiving chemotherapy during the last months of life. There is an increase in visits to the emergency department, hospitalizations, and death in the hospital when cancer patients are actively receiving chemotherapy during end of life.

Overutilization of chemotherapy treatment is poor quality care leading to adverse patient outcomes. The intent of hospice care is to meet the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of a dying patient and their family. The focus of care is on comfort, not cure. The intent of palliative care focuses on symptom control and may include a combination of comfort measures and curative interventions. This review supports further investigation into the practice of chemotherapy administration in terminally ill patients.

Background: A majority of end-stage cancer patients are receiving chemotherapy, regardless of performance status, in the last months of life. Oncologists continue to prescribe disease targeted therapy for patients enrolled in palliative or hospice care in an attempt to alleviate symptoms and extend life expectancy. Research indicates that chemotherapy at end of life does not accomplish either of these goals of care, and may actually do more harm than good.

Methods: An evidence based research review indicates that > 50% of all cancer patients are receiving chemotherapy during their last 4-6 months of life. Data supports a decreased quality of life and decreased life expectancy for patients receiving chemotherapy during the last months of life. There is an increase in visits to the emergency department, hospitalizations, and death in the hospital when cancer patients are actively receiving chemotherapy during end of life.

Overutilization of chemotherapy treatment is poor quality care leading to adverse patient outcomes. The intent of hospice care is to meet the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of a dying patient and their family. The focus of care is on comfort, not cure. The intent of palliative care focuses on symptom control and may include a combination of comfort measures and curative interventions. This review supports further investigation into the practice of chemotherapy administration in terminally ill patients.

Background: A majority of end-stage cancer patients are receiving chemotherapy, regardless of performance status, in the last months of life. Oncologists continue to prescribe disease targeted therapy for patients enrolled in palliative or hospice care in an attempt to alleviate symptoms and extend life expectancy. Research indicates that chemotherapy at end of life does not accomplish either of these goals of care, and may actually do more harm than good.

Methods: An evidence based research review indicates that > 50% of all cancer patients are receiving chemotherapy during their last 4-6 months of life. Data supports a decreased quality of life and decreased life expectancy for patients receiving chemotherapy during the last months of life. There is an increase in visits to the emergency department, hospitalizations, and death in the hospital when cancer patients are actively receiving chemotherapy during end of life.

Overutilization of chemotherapy treatment is poor quality care leading to adverse patient outcomes. The intent of hospice care is to meet the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs of a dying patient and their family. The focus of care is on comfort, not cure. The intent of palliative care focuses on symptom control and may include a combination of comfort measures and curative interventions. This review supports further investigation into the practice of chemotherapy administration in terminally ill patients.

Integrated Outpatient Palliative Care for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Background: Despite increasing emphasis on integration of palliative care with disease-directed care for advanced cancer, the nature of this integration and its effects on patient and caregiver outcomes are not well understood.

Methods: We evaluated the effects of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care for advanced cancer on patient and caregiver outcomes. Following a standard protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42017057541), investigators independently screened reports to identify randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies that evaluated the effect of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care interventions on quality of life, survival, and healthcare utilization among adults with advanced cancer. Data sources were English-language peer-reviewed publications in PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane Central through November 2016. We subsequently updated our PubMed search through July 2018. Data were synthesized using random-effects meta-analyses, supplemented with qualitative methods when necessary.

Results: Eight randomized controlled and two cluster randomized trials were included. Most patients had multiple advanced cancers, with median time from diagnosis or recurrence to enrollment ranging from eight to 12 weeks. All interventions included a multidisciplinary team, were classified as “moderately integrated,” and addressed physical and psychological symptoms. In a meta-analysis, short-term quality of life improved; symptom burden improved; and all-cause mortality decreased. Qualitative analyses revealed no association between integration elements, palliative care intervention elements, and intervention impact. Utilization and caregiver outcomes were often not reported.

Conclusion: Moderately integrated palliative and oncology outpatient interventions had positive effects on short-term quality of life, symptom burden, and survival. Evidence for effects on healthcare utilization and caregiver outcomes remains sparse.

Background: Despite increasing emphasis on integration of palliative care with disease-directed care for advanced cancer, the nature of this integration and its effects on patient and caregiver outcomes are not well understood.

Methods: We evaluated the effects of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care for advanced cancer on patient and caregiver outcomes. Following a standard protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42017057541), investigators independently screened reports to identify randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies that evaluated the effect of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care interventions on quality of life, survival, and healthcare utilization among adults with advanced cancer. Data sources were English-language peer-reviewed publications in PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane Central through November 2016. We subsequently updated our PubMed search through July 2018. Data were synthesized using random-effects meta-analyses, supplemented with qualitative methods when necessary.

Results: Eight randomized controlled and two cluster randomized trials were included. Most patients had multiple advanced cancers, with median time from diagnosis or recurrence to enrollment ranging from eight to 12 weeks. All interventions included a multidisciplinary team, were classified as “moderately integrated,” and addressed physical and psychological symptoms. In a meta-analysis, short-term quality of life improved; symptom burden improved; and all-cause mortality decreased. Qualitative analyses revealed no association between integration elements, palliative care intervention elements, and intervention impact. Utilization and caregiver outcomes were often not reported.

Conclusion: Moderately integrated palliative and oncology outpatient interventions had positive effects on short-term quality of life, symptom burden, and survival. Evidence for effects on healthcare utilization and caregiver outcomes remains sparse.

Background: Despite increasing emphasis on integration of palliative care with disease-directed care for advanced cancer, the nature of this integration and its effects on patient and caregiver outcomes are not well understood.

Methods: We evaluated the effects of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care for advanced cancer on patient and caregiver outcomes. Following a standard protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42017057541), investigators independently screened reports to identify randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies that evaluated the effect of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care interventions on quality of life, survival, and healthcare utilization among adults with advanced cancer. Data sources were English-language peer-reviewed publications in PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane Central through November 2016. We subsequently updated our PubMed search through July 2018. Data were synthesized using random-effects meta-analyses, supplemented with qualitative methods when necessary.

Results: Eight randomized controlled and two cluster randomized trials were included. Most patients had multiple advanced cancers, with median time from diagnosis or recurrence to enrollment ranging from eight to 12 weeks. All interventions included a multidisciplinary team, were classified as “moderately integrated,” and addressed physical and psychological symptoms. In a meta-analysis, short-term quality of life improved; symptom burden improved; and all-cause mortality decreased. Qualitative analyses revealed no association between integration elements, palliative care intervention elements, and intervention impact. Utilization and caregiver outcomes were often not reported.

Conclusion: Moderately integrated palliative and oncology outpatient interventions had positive effects on short-term quality of life, symptom burden, and survival. Evidence for effects on healthcare utilization and caregiver outcomes remains sparse.

The Impact of Registered Dietitian Staffing and Nutrition Practices in High-Risk Cancer Patients Across the Veterans Health Administration

Background: Malnutrition in cancer patients has a significant correlation with disability, dysfunction and death, as well as increased patient care costs, neutropenia, reduced quality of life, fall risk, fractures, nosocomial infections, and longer treatment durations 1-3. Registered dietitian (RD) involvement early on may increase recognition of malnutrition for at-risk patients. Guidelines for nutrition staffing in cancer centers is illdefined in the literature, with few existing recommendations.

Methods: In Phase 1, a survey of RDs across VHA was conducted to determine current referral and staffing practices surrounding nutrition care and services in outpatient oncology clinics. The survey was administered to RDs who devote some or all of their time to oncology nutrition in the outpatient setting and participate on 1 of 2 popular VHA listservs: a nutrition support listserv, and an oncology nutrition listserv.

Phase 2 will be a multi-site, retrospective, chart analysis among 20 VA facilities who treat cancer patients in the outpatient setting. Site investigators, divided into proactive vs. reactive nutrition practices based on Phase 1 survey results, will be instructed to obtain a list of patients diagnosed with high nutrition risk cancers during 2016 and 2017.

Primary outcomes measured will include weight loss, percent maximum weight change over speci ed timeframes, diagnosis of malnutrition, and reported breaks in treatment. Secondary outcomes include overall survival and disease-free survival. For all comparisons, P < 0.05 will be considered statistically signifcant.

Discussion: The data from 46 sites completing the national survey show that RD staffing practices vary widely across VA cancer centers. Few centers staff full time or dedicated oncology RDs independent of patient caseload, with the median oncology dedicated RD FTE being 0.5. Consult and referral practices dictating nutrition intervention were found to be reported as 17% proactive, 25% reactive, and 58% a combination of both practices. Phase 2 results seek to compare patient outcomes with RD staffing and nutrition care practices to determine much needed guidelines for effective nutrition delivery in VHA cancer centers across the U.S.

Background: Malnutrition in cancer patients has a significant correlation with disability, dysfunction and death, as well as increased patient care costs, neutropenia, reduced quality of life, fall risk, fractures, nosocomial infections, and longer treatment durations 1-3. Registered dietitian (RD) involvement early on may increase recognition of malnutrition for at-risk patients. Guidelines for nutrition staffing in cancer centers is illdefined in the literature, with few existing recommendations.

Methods: In Phase 1, a survey of RDs across VHA was conducted to determine current referral and staffing practices surrounding nutrition care and services in outpatient oncology clinics. The survey was administered to RDs who devote some or all of their time to oncology nutrition in the outpatient setting and participate on 1 of 2 popular VHA listservs: a nutrition support listserv, and an oncology nutrition listserv.

Phase 2 will be a multi-site, retrospective, chart analysis among 20 VA facilities who treat cancer patients in the outpatient setting. Site investigators, divided into proactive vs. reactive nutrition practices based on Phase 1 survey results, will be instructed to obtain a list of patients diagnosed with high nutrition risk cancers during 2016 and 2017.

Primary outcomes measured will include weight loss, percent maximum weight change over speci ed timeframes, diagnosis of malnutrition, and reported breaks in treatment. Secondary outcomes include overall survival and disease-free survival. For all comparisons, P < 0.05 will be considered statistically signifcant.

Discussion: The data from 46 sites completing the national survey show that RD staffing practices vary widely across VA cancer centers. Few centers staff full time or dedicated oncology RDs independent of patient caseload, with the median oncology dedicated RD FTE being 0.5. Consult and referral practices dictating nutrition intervention were found to be reported as 17% proactive, 25% reactive, and 58% a combination of both practices. Phase 2 results seek to compare patient outcomes with RD staffing and nutrition care practices to determine much needed guidelines for effective nutrition delivery in VHA cancer centers across the U.S.

Background: Malnutrition in cancer patients has a significant correlation with disability, dysfunction and death, as well as increased patient care costs, neutropenia, reduced quality of life, fall risk, fractures, nosocomial infections, and longer treatment durations 1-3. Registered dietitian (RD) involvement early on may increase recognition of malnutrition for at-risk patients. Guidelines for nutrition staffing in cancer centers is illdefined in the literature, with few existing recommendations.

Methods: In Phase 1, a survey of RDs across VHA was conducted to determine current referral and staffing practices surrounding nutrition care and services in outpatient oncology clinics. The survey was administered to RDs who devote some or all of their time to oncology nutrition in the outpatient setting and participate on 1 of 2 popular VHA listservs: a nutrition support listserv, and an oncology nutrition listserv.

Phase 2 will be a multi-site, retrospective, chart analysis among 20 VA facilities who treat cancer patients in the outpatient setting. Site investigators, divided into proactive vs. reactive nutrition practices based on Phase 1 survey results, will be instructed to obtain a list of patients diagnosed with high nutrition risk cancers during 2016 and 2017.

Primary outcomes measured will include weight loss, percent maximum weight change over speci ed timeframes, diagnosis of malnutrition, and reported breaks in treatment. Secondary outcomes include overall survival and disease-free survival. For all comparisons, P < 0.05 will be considered statistically signifcant.

Discussion: The data from 46 sites completing the national survey show that RD staffing practices vary widely across VA cancer centers. Few centers staff full time or dedicated oncology RDs independent of patient caseload, with the median oncology dedicated RD FTE being 0.5. Consult and referral practices dictating nutrition intervention were found to be reported as 17% proactive, 25% reactive, and 58% a combination of both practices. Phase 2 results seek to compare patient outcomes with RD staffing and nutrition care practices to determine much needed guidelines for effective nutrition delivery in VHA cancer centers across the U.S.

Impact of Integrated Oncology- Palliative Care Outpatient Model on Trends of Palliative Care and Hospice Care Referrals From Oncology

Background: A commonly voiced concern of oncologists, regarding the introduction of palliative care, is that patients might be immediately steered to hospice care and away from oncology care.

Objective: To assess the impact of oncology-palliative care collaboration on trends of referrals to palliative and hospice care.

Methods: In January 2015, we implemented an integrated oncology-palliative care clinic model with the following elements:

- Pre-clinic “huddle” among palliative care and oncology staff to identify palliative care needs for patients;

- Shared palliative care and oncology clinic appointments;

- Introduction of palliative care for every new oncology clinic patient, for advance care planning;

- Concurrent oncology and palliative care follow-up for all high-risk patients (aggressive histology, progressing disease, etc.) for goals of care discussions and symptom management; and

- Palliative care and oncology staff co-managing oncology patients enrolled in hospice care.

Measurements: We examined the following metrics for FY15, FY16, FY17, and FY18.

- Total number of palliative care consults;

- Number of palliative care consults from oncology;

- Percentage palliative care consults from oncology [(item 2 × 100) / item 1];

- Total number of referrals to hospice care;

- Number of referrals to hospice care from oncology; and

- Percentage hospice care referrals from oncology [(item 5 × 100) / item 4].

Results: During the period of FY15 to FY18, there was a consistent increase in total palliative care consults (355, 394, 549, and 570 respectively). There also was a consistent increase in percentage palliative care consults from oncology (24%, 34%, 38%, and 40% respectively) without an increase in percentage hospice care referrals from oncology.

Conclusion: A common concern is that palliative care in oncology care will result in patients being immediately steered to hospice care and away from continued oncology care. Although it was limited to a single clinical setting, our intervention resulted in increased palliative care consults from oncology without a proportionate increase in hospice care referrals from oncology during the same time-period, suggesting that earlier access to palliative care did not result in immediate transition to hospice care. Palliative care offers opportunities for goals of care conversations and symptom management in oncology care, prior to transition to hospice care. Future implications include robust studies to further test these findings, review of structure and training of oncology-palliative care teams, and systems redesign to develop dyad or shared clinic models.

Background: A commonly voiced concern of oncologists, regarding the introduction of palliative care, is that patients might be immediately steered to hospice care and away from oncology care.

Objective: To assess the impact of oncology-palliative care collaboration on trends of referrals to palliative and hospice care.

Methods: In January 2015, we implemented an integrated oncology-palliative care clinic model with the following elements:

- Pre-clinic “huddle” among palliative care and oncology staff to identify palliative care needs for patients;

- Shared palliative care and oncology clinic appointments;

- Introduction of palliative care for every new oncology clinic patient, for advance care planning;

- Concurrent oncology and palliative care follow-up for all high-risk patients (aggressive histology, progressing disease, etc.) for goals of care discussions and symptom management; and

- Palliative care and oncology staff co-managing oncology patients enrolled in hospice care.

Measurements: We examined the following metrics for FY15, FY16, FY17, and FY18.

- Total number of palliative care consults;

- Number of palliative care consults from oncology;

- Percentage palliative care consults from oncology [(item 2 × 100) / item 1];

- Total number of referrals to hospice care;

- Number of referrals to hospice care from oncology; and

- Percentage hospice care referrals from oncology [(item 5 × 100) / item 4].

Results: During the period of FY15 to FY18, there was a consistent increase in total palliative care consults (355, 394, 549, and 570 respectively). There also was a consistent increase in percentage palliative care consults from oncology (24%, 34%, 38%, and 40% respectively) without an increase in percentage hospice care referrals from oncology.

Conclusion: A common concern is that palliative care in oncology care will result in patients being immediately steered to hospice care and away from continued oncology care. Although it was limited to a single clinical setting, our intervention resulted in increased palliative care consults from oncology without a proportionate increase in hospice care referrals from oncology during the same time-period, suggesting that earlier access to palliative care did not result in immediate transition to hospice care. Palliative care offers opportunities for goals of care conversations and symptom management in oncology care, prior to transition to hospice care. Future implications include robust studies to further test these findings, review of structure and training of oncology-palliative care teams, and systems redesign to develop dyad or shared clinic models.

Background: A commonly voiced concern of oncologists, regarding the introduction of palliative care, is that patients might be immediately steered to hospice care and away from oncology care.

Objective: To assess the impact of oncology-palliative care collaboration on trends of referrals to palliative and hospice care.

Methods: In January 2015, we implemented an integrated oncology-palliative care clinic model with the following elements:

- Pre-clinic “huddle” among palliative care and oncology staff to identify palliative care needs for patients;

- Shared palliative care and oncology clinic appointments;

- Introduction of palliative care for every new oncology clinic patient, for advance care planning;

- Concurrent oncology and palliative care follow-up for all high-risk patients (aggressive histology, progressing disease, etc.) for goals of care discussions and symptom management; and

- Palliative care and oncology staff co-managing oncology patients enrolled in hospice care.

Measurements: We examined the following metrics for FY15, FY16, FY17, and FY18.

- Total number of palliative care consults;

- Number of palliative care consults from oncology;

- Percentage palliative care consults from oncology [(item 2 × 100) / item 1];

- Total number of referrals to hospice care;

- Number of referrals to hospice care from oncology; and

- Percentage hospice care referrals from oncology [(item 5 × 100) / item 4].

Results: During the period of FY15 to FY18, there was a consistent increase in total palliative care consults (355, 394, 549, and 570 respectively). There also was a consistent increase in percentage palliative care consults from oncology (24%, 34%, 38%, and 40% respectively) without an increase in percentage hospice care referrals from oncology.

Conclusion: A common concern is that palliative care in oncology care will result in patients being immediately steered to hospice care and away from continued oncology care. Although it was limited to a single clinical setting, our intervention resulted in increased palliative care consults from oncology without a proportionate increase in hospice care referrals from oncology during the same time-period, suggesting that earlier access to palliative care did not result in immediate transition to hospice care. Palliative care offers opportunities for goals of care conversations and symptom management in oncology care, prior to transition to hospice care. Future implications include robust studies to further test these findings, review of structure and training of oncology-palliative care teams, and systems redesign to develop dyad or shared clinic models.

Fatal Drug-Resistant Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus in a 56-Year-Old Immunosuppressed Man (FULL)

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

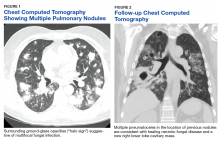

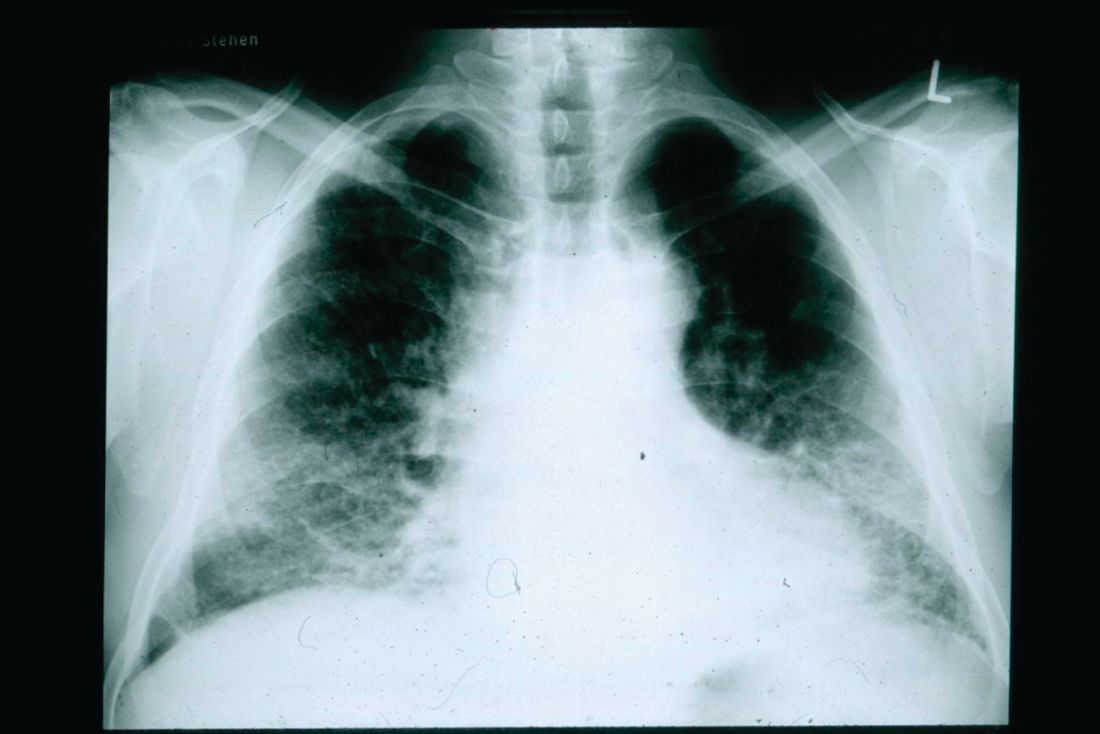

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

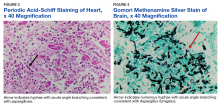

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

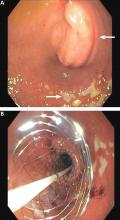

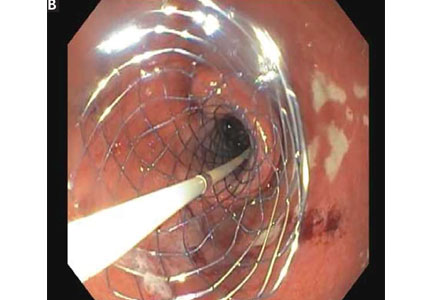

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.

2. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):408-415.

3. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

4. García-Cadenas I, Rivera I, Martino R, et al. Patterns of infection and infection-related mortality in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(1):107-113.

5. Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(8):4569-4576.

6. Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(5):673-680.

7. Cuenca-Estrella M, Moore CB, Barchiesi F, et al; AFST Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(6):467-474.

8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, et al; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3142-3146.

9. Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89.

10. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):584-587.

11. Rajendran R, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Ramage G. Prior in vitro exposure to voriconazole confers resistance to amphotericin B in Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):342-345.

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.

2. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):408-415.

3. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

4. García-Cadenas I, Rivera I, Martino R, et al. Patterns of infection and infection-related mortality in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(1):107-113.

5. Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(8):4569-4576.

6. Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(5):673-680.

7. Cuenca-Estrella M, Moore CB, Barchiesi F, et al; AFST Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(6):467-474.

8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, et al; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3142-3146.

9. Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89.

10. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):584-587.

11. Rajendran R, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Ramage G. Prior in vitro exposure to voriconazole confers resistance to amphotericin B in Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):342-345.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.

2. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):408-415.

3. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

4. García-Cadenas I, Rivera I, Martino R, et al. Patterns of infection and infection-related mortality in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(1):107-113.

5. Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(8):4569-4576.

6. Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(5):673-680.

7. Cuenca-Estrella M, Moore CB, Barchiesi F, et al; AFST Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(6):467-474.

8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, et al; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3142-3146.

9. Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89.

10. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):584-587.

11. Rajendran R, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Ramage G. Prior in vitro exposure to voriconazole confers resistance to amphotericin B in Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):342-345.

Survey: Palliative care blocked by many barriers in end-stage liver disease

results of a recent survey show.

Cultural factors, unrealistic expectations of the patient, lack of reimbursement, and competing demands for physicians’ time were some of the barriers to palliative care cited most frequently in the survey, said the researchers, in their report on the survey results that appears in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Moreover, most responding physicians said they felt end-of-life advance care planning discussions take place too late in the course of illness, according to Nneka N. Ufere, MD, of the Gastrointestinal Unit, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and co-authors of the report.

“Multiple interventions targeted at patients, caregivers, institutions, and clinicians are needed to overcome barriers to improve the delivery of high-quality palliative and end-of-life care for patients with end-stage liver disease,” the researchers said.

Specialty palliative care can improve quality of life for patients with life-limiting conditions such as end-stage liver disease, which is associated with poor quality of life and a median survival of just two years without liver transplant, the authors said.

Advance care planning, in which patients discuss goals and care preferences in light of the expected course of illness, was a “critical component” of palliative care that can improve the quality of end-of-life care, Dr. Ufere and co-authors said.

Unfortunately, palliative care planning services are underutilized in end-stage liver disease, studies show, while rates of timely advance care planning discussions are low.

To find out why, Dr. Ufere and colleagues asked 1,238 physicians to fill out a web-based questionnaire designed to assess their perceptions of barriers to use of palliative care and barriers to timely advance care planning discussions. A total of 396 physicians (32%) completed the survey between February and April 2018.

Sixty percent were transplant hepatologists, and 79% of the survey participants said they worked in a teaching hospital, according to Dr. Ufere and co-authors, who added that no respondents had formal palliative care training.

Almost all respondents (95%) agreed that centers providing care for end-stage liver disease patients should have palliative care services, and most (86%) said they thought such patients would benefit from palliative care earlier in the course of disease.

While most (84%) agreed that a hepatologist was the best provider to discuss advance care planning with the patient, only about one-quarter (27%) said the hepatologist was best suited to provide palliative care, while most (88%) said the palliative care specialist was best for that role.

When asked about patient and caregiver barriers, nearly all respondents (95%) agreed that cultural factors that influenced palliative care perception was an issue, while 93% said patients’ unrealistic expectations was an issue.

Clinician barriers that respondents perceived included competing demands for clinicians’ time, cited by 91%, fear that palliative care might destroy the patient’s hope, cited by 82%, and the misperception that palliative care starts when active treatment ends, cited by 81%.

One potential solution to the competing demands on clinicians’ time would be development of “collaborative care models” between palliative care and hepatology services, according to Dr. Ufere and co-authors.

“Outpatient specialty palliative care visits, ideally temporally coordinated with the hepatology visits, can play a role not only in attending to symptom assessment and ACP, but also in addressing important psychosocial aspects of care, such as patient coping and well-being,” they said in their report on the survey.

Institutional barriers of note included limited reimbursement for time spent providing palliative care, cited by 76% and lack of a palliative care service, cited by nearly half (46%).

Some of the most commonly affirmed barriers to timely advance care planning discussions included insufficient training in end-of-life communication issues, and insufficient training in cultural competency issues related to the discussions.

In terms of timeliness, only 17% said advance care planning discussions happen at the right time, while 81% said they happen too late, investigators found.

Funding for the research came from the National Institutes of Health. The authors had no disclosures or conflicts of interest related to the report.

SOURCE: Ufere NN, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.022.

results of a recent survey show.

Cultural factors, unrealistic expectations of the patient, lack of reimbursement, and competing demands for physicians’ time were some of the barriers to palliative care cited most frequently in the survey, said the researchers, in their report on the survey results that appears in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Moreover, most responding physicians said they felt end-of-life advance care planning discussions take place too late in the course of illness, according to Nneka N. Ufere, MD, of the Gastrointestinal Unit, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and co-authors of the report.

“Multiple interventions targeted at patients, caregivers, institutions, and clinicians are needed to overcome barriers to improve the delivery of high-quality palliative and end-of-life care for patients with end-stage liver disease,” the researchers said.

Specialty palliative care can improve quality of life for patients with life-limiting conditions such as end-stage liver disease, which is associated with poor quality of life and a median survival of just two years without liver transplant, the authors said.

Advance care planning, in which patients discuss goals and care preferences in light of the expected course of illness, was a “critical component” of palliative care that can improve the quality of end-of-life care, Dr. Ufere and co-authors said.

Unfortunately, palliative care planning services are underutilized in end-stage liver disease, studies show, while rates of timely advance care planning discussions are low.

To find out why, Dr. Ufere and colleagues asked 1,238 physicians to fill out a web-based questionnaire designed to assess their perceptions of barriers to use of palliative care and barriers to timely advance care planning discussions. A total of 396 physicians (32%) completed the survey between February and April 2018.

Sixty percent were transplant hepatologists, and 79% of the survey participants said they worked in a teaching hospital, according to Dr. Ufere and co-authors, who added that no respondents had formal palliative care training.

Almost all respondents (95%) agreed that centers providing care for end-stage liver disease patients should have palliative care services, and most (86%) said they thought such patients would benefit from palliative care earlier in the course of disease.

While most (84%) agreed that a hepatologist was the best provider to discuss advance care planning with the patient, only about one-quarter (27%) said the hepatologist was best suited to provide palliative care, while most (88%) said the palliative care specialist was best for that role.

When asked about patient and caregiver barriers, nearly all respondents (95%) agreed that cultural factors that influenced palliative care perception was an issue, while 93% said patients’ unrealistic expectations was an issue.

Clinician barriers that respondents perceived included competing demands for clinicians’ time, cited by 91%, fear that palliative care might destroy the patient’s hope, cited by 82%, and the misperception that palliative care starts when active treatment ends, cited by 81%.

One potential solution to the competing demands on clinicians’ time would be development of “collaborative care models” between palliative care and hepatology services, according to Dr. Ufere and co-authors.

“Outpatient specialty palliative care visits, ideally temporally coordinated with the hepatology visits, can play a role not only in attending to symptom assessment and ACP, but also in addressing important psychosocial aspects of care, such as patient coping and well-being,” they said in their report on the survey.

Institutional barriers of note included limited reimbursement for time spent providing palliative care, cited by 76% and lack of a palliative care service, cited by nearly half (46%).

Some of the most commonly affirmed barriers to timely advance care planning discussions included insufficient training in end-of-life communication issues, and insufficient training in cultural competency issues related to the discussions.

In terms of timeliness, only 17% said advance care planning discussions happen at the right time, while 81% said they happen too late, investigators found.

Funding for the research came from the National Institutes of Health. The authors had no disclosures or conflicts of interest related to the report.

SOURCE: Ufere NN, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.022.

results of a recent survey show.

Cultural factors, unrealistic expectations of the patient, lack of reimbursement, and competing demands for physicians’ time were some of the barriers to palliative care cited most frequently in the survey, said the researchers, in their report on the survey results that appears in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Moreover, most responding physicians said they felt end-of-life advance care planning discussions take place too late in the course of illness, according to Nneka N. Ufere, MD, of the Gastrointestinal Unit, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and co-authors of the report.

“Multiple interventions targeted at patients, caregivers, institutions, and clinicians are needed to overcome barriers to improve the delivery of high-quality palliative and end-of-life care for patients with end-stage liver disease,” the researchers said.

Specialty palliative care can improve quality of life for patients with life-limiting conditions such as end-stage liver disease, which is associated with poor quality of life and a median survival of just two years without liver transplant, the authors said.

Advance care planning, in which patients discuss goals and care preferences in light of the expected course of illness, was a “critical component” of palliative care that can improve the quality of end-of-life care, Dr. Ufere and co-authors said.

Unfortunately, palliative care planning services are underutilized in end-stage liver disease, studies show, while rates of timely advance care planning discussions are low.

To find out why, Dr. Ufere and colleagues asked 1,238 physicians to fill out a web-based questionnaire designed to assess their perceptions of barriers to use of palliative care and barriers to timely advance care planning discussions. A total of 396 physicians (32%) completed the survey between February and April 2018.

Sixty percent were transplant hepatologists, and 79% of the survey participants said they worked in a teaching hospital, according to Dr. Ufere and co-authors, who added that no respondents had formal palliative care training.

Almost all respondents (95%) agreed that centers providing care for end-stage liver disease patients should have palliative care services, and most (86%) said they thought such patients would benefit from palliative care earlier in the course of disease.

While most (84%) agreed that a hepatologist was the best provider to discuss advance care planning with the patient, only about one-quarter (27%) said the hepatologist was best suited to provide palliative care, while most (88%) said the palliative care specialist was best for that role.

When asked about patient and caregiver barriers, nearly all respondents (95%) agreed that cultural factors that influenced palliative care perception was an issue, while 93% said patients’ unrealistic expectations was an issue.

Clinician barriers that respondents perceived included competing demands for clinicians’ time, cited by 91%, fear that palliative care might destroy the patient’s hope, cited by 82%, and the misperception that palliative care starts when active treatment ends, cited by 81%.

One potential solution to the competing demands on clinicians’ time would be development of “collaborative care models” between palliative care and hepatology services, according to Dr. Ufere and co-authors.

“Outpatient specialty palliative care visits, ideally temporally coordinated with the hepatology visits, can play a role not only in attending to symptom assessment and ACP, but also in addressing important psychosocial aspects of care, such as patient coping and well-being,” they said in their report on the survey.

Institutional barriers of note included limited reimbursement for time spent providing palliative care, cited by 76% and lack of a palliative care service, cited by nearly half (46%).

Some of the most commonly affirmed barriers to timely advance care planning discussions included insufficient training in end-of-life communication issues, and insufficient training in cultural competency issues related to the discussions.

In terms of timeliness, only 17% said advance care planning discussions happen at the right time, while 81% said they happen too late, investigators found.

Funding for the research came from the National Institutes of Health. The authors had no disclosures or conflicts of interest related to the report.

SOURCE: Ufere NN, et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.03.022.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Gastric outlet obstruction: A red flag, potentially manageable

A 72-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with progressive nausea and vomiting. One week earlier, she developed early satiety and nausea with vomiting after eating solid food. Three days later her symptoms progressed, and she became unable to take anything by mouth. The patient also experienced a 40-lb weight loss in the previous 3 months. She denies symptoms of abdominal pain, hematemesis, or melena. Her medical history includes cholecystectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus, diagnosed 1 year ago. She has no family history of gastrointestinal malignancy. She says she smoked 1 pack a day in her 20s. She does not consume alcohol.

On physical examination, she is normotensive with a heart rate of 105 beats per minute. The oral mucosa is dry, and the abdomen is mildly distended and tender to palpation in the epigastrium. Laboratory evaluation reveals hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis.