User login

Does reduced degradation of insulin by the liver cause type 2 diabetes?

LOS ANGELES –

That’s a hypothesis that Richard N. Bergman, PhD, and his colleagues are testing in his lab at the Sports Spectacular Diabetes and Obesity Wellness and Research Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“More than 50% of insulin secreted into the portal vein is degraded by the liver and never enters the systemic circulation,” Dr. Bergman said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “We have found that if you make an animal insulin resistant with a high fat diet, they degrade less of the insulin. Why is that? They deliver a higher fraction of the insulin into the systemic circulation. One of the answers is that the liver is a gateway for insulin delivery to the systemic circulation.” In fact, when he and his colleagues tested a population of normal dogs, they found wide variability in the ability of the liver to take up and degrade insulin (Diabetes. 2018 67[8]:1495-503).

“It ranged from 20% to 70%; I didn’t believe these data,” said Dr. Bergman, who is also chair in diabetes research at Cedars-Sinai. “We had to redo the study and the same thing was true. There’s a wide variation in what fraction of insulin that enters the liver is degraded. That led to the idea that this could be true in humans.”

To follow up on this concept, he and his colleagues used data from 100 African immigrants without diabetes to develop a model to estimate hepatic versus extrahepatic insulin clearance in humans (Diabetes. 2016;65[6]:1556-64). “This population was chosen because previous studies have suggested that individuals of African descent have reduced hepatic insulin clearance compared with Western subjects,” the authors wrote in the article. “Similarly, FSIGT [frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test] data from two groups showed that African American women had much higher plasma insulin concentrations than European American women during periods of elevated endogenous secretion but not after intravenous insulin infusion, also suggesting reduced hepatic, but not extrahepatic, insulin clearance in African American subjects. Thus, this population was of special interest for applying a model that could quantify both hepatic and extrahepatic insulin clearance.”

The model was able to reproduce accurately the full plasma insulin profiles observed during the FSIGT and identify clear differences in parameter values among individuals. “The ability of the liver to degrade insulin is very variable across a normal human population,” Dr. Bergman said. “That means this may be a controlled variable.”

In a separate analysis of 23 African American and 23 European American women, Dr. Bergman, Francesca Piccinini, PhD, Barbara A. Gower, PhD, and colleagues found that hepatic but not extrahepatic insulin clearance is lower in the African American women, compared with their European American counterparts (Diabetes. 2017;66[10]:2564-70). Data from a cohort of children found the same thing (Diabetes Obes & Metab. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/dom.13471).

“What does this mean that different ethnic groups have different clearance of insulin?” he asked. “It means that African Americans deliver a higher fraction of secreted insulin into the systemic circulation. We know that African Americans tend to be hyperinsulinemic. That isn’t necessarily due to oversecretion of insulin; it’s likely due primarily to reduced degradation of insulin. The question then is, can the reduced insulin clearance play a causal role in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes?”

He hypothesized that, in normal individuals, half of insulin secreted by the pancreas is exported into the systemic circulation and half is degraded. “We propose that in people at risk for diabetes, insulin is secreted by the pancreas but much less of it is degraded,” Dr. Bergman continued. “Insulin gets into the systemic circulation, so then you can get hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance. The resistance stresses the beta cells of the pancreas. Thus, the idea is that differences in clearance of insulin by the liver in some individuals may be pathogenic in the cause of diabetes.”

Dr. Bergman reported that he has done consulting/collaboration with Janssen, January, Novo Nordisk, and Zafgen. He has also received research grants from Astra Zeneca, Janssen, and the National Institutes of Health.

LOS ANGELES –

That’s a hypothesis that Richard N. Bergman, PhD, and his colleagues are testing in his lab at the Sports Spectacular Diabetes and Obesity Wellness and Research Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“More than 50% of insulin secreted into the portal vein is degraded by the liver and never enters the systemic circulation,” Dr. Bergman said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “We have found that if you make an animal insulin resistant with a high fat diet, they degrade less of the insulin. Why is that? They deliver a higher fraction of the insulin into the systemic circulation. One of the answers is that the liver is a gateway for insulin delivery to the systemic circulation.” In fact, when he and his colleagues tested a population of normal dogs, they found wide variability in the ability of the liver to take up and degrade insulin (Diabetes. 2018 67[8]:1495-503).

“It ranged from 20% to 70%; I didn’t believe these data,” said Dr. Bergman, who is also chair in diabetes research at Cedars-Sinai. “We had to redo the study and the same thing was true. There’s a wide variation in what fraction of insulin that enters the liver is degraded. That led to the idea that this could be true in humans.”

To follow up on this concept, he and his colleagues used data from 100 African immigrants without diabetes to develop a model to estimate hepatic versus extrahepatic insulin clearance in humans (Diabetes. 2016;65[6]:1556-64). “This population was chosen because previous studies have suggested that individuals of African descent have reduced hepatic insulin clearance compared with Western subjects,” the authors wrote in the article. “Similarly, FSIGT [frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test] data from two groups showed that African American women had much higher plasma insulin concentrations than European American women during periods of elevated endogenous secretion but not after intravenous insulin infusion, also suggesting reduced hepatic, but not extrahepatic, insulin clearance in African American subjects. Thus, this population was of special interest for applying a model that could quantify both hepatic and extrahepatic insulin clearance.”

The model was able to reproduce accurately the full plasma insulin profiles observed during the FSIGT and identify clear differences in parameter values among individuals. “The ability of the liver to degrade insulin is very variable across a normal human population,” Dr. Bergman said. “That means this may be a controlled variable.”

In a separate analysis of 23 African American and 23 European American women, Dr. Bergman, Francesca Piccinini, PhD, Barbara A. Gower, PhD, and colleagues found that hepatic but not extrahepatic insulin clearance is lower in the African American women, compared with their European American counterparts (Diabetes. 2017;66[10]:2564-70). Data from a cohort of children found the same thing (Diabetes Obes & Metab. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/dom.13471).

“What does this mean that different ethnic groups have different clearance of insulin?” he asked. “It means that African Americans deliver a higher fraction of secreted insulin into the systemic circulation. We know that African Americans tend to be hyperinsulinemic. That isn’t necessarily due to oversecretion of insulin; it’s likely due primarily to reduced degradation of insulin. The question then is, can the reduced insulin clearance play a causal role in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes?”

He hypothesized that, in normal individuals, half of insulin secreted by the pancreas is exported into the systemic circulation and half is degraded. “We propose that in people at risk for diabetes, insulin is secreted by the pancreas but much less of it is degraded,” Dr. Bergman continued. “Insulin gets into the systemic circulation, so then you can get hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance. The resistance stresses the beta cells of the pancreas. Thus, the idea is that differences in clearance of insulin by the liver in some individuals may be pathogenic in the cause of diabetes.”

Dr. Bergman reported that he has done consulting/collaboration with Janssen, January, Novo Nordisk, and Zafgen. He has also received research grants from Astra Zeneca, Janssen, and the National Institutes of Health.

LOS ANGELES –

That’s a hypothesis that Richard N. Bergman, PhD, and his colleagues are testing in his lab at the Sports Spectacular Diabetes and Obesity Wellness and Research Center at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“More than 50% of insulin secreted into the portal vein is degraded by the liver and never enters the systemic circulation,” Dr. Bergman said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “We have found that if you make an animal insulin resistant with a high fat diet, they degrade less of the insulin. Why is that? They deliver a higher fraction of the insulin into the systemic circulation. One of the answers is that the liver is a gateway for insulin delivery to the systemic circulation.” In fact, when he and his colleagues tested a population of normal dogs, they found wide variability in the ability of the liver to take up and degrade insulin (Diabetes. 2018 67[8]:1495-503).

“It ranged from 20% to 70%; I didn’t believe these data,” said Dr. Bergman, who is also chair in diabetes research at Cedars-Sinai. “We had to redo the study and the same thing was true. There’s a wide variation in what fraction of insulin that enters the liver is degraded. That led to the idea that this could be true in humans.”

To follow up on this concept, he and his colleagues used data from 100 African immigrants without diabetes to develop a model to estimate hepatic versus extrahepatic insulin clearance in humans (Diabetes. 2016;65[6]:1556-64). “This population was chosen because previous studies have suggested that individuals of African descent have reduced hepatic insulin clearance compared with Western subjects,” the authors wrote in the article. “Similarly, FSIGT [frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test] data from two groups showed that African American women had much higher plasma insulin concentrations than European American women during periods of elevated endogenous secretion but not after intravenous insulin infusion, also suggesting reduced hepatic, but not extrahepatic, insulin clearance in African American subjects. Thus, this population was of special interest for applying a model that could quantify both hepatic and extrahepatic insulin clearance.”

The model was able to reproduce accurately the full plasma insulin profiles observed during the FSIGT and identify clear differences in parameter values among individuals. “The ability of the liver to degrade insulin is very variable across a normal human population,” Dr. Bergman said. “That means this may be a controlled variable.”

In a separate analysis of 23 African American and 23 European American women, Dr. Bergman, Francesca Piccinini, PhD, Barbara A. Gower, PhD, and colleagues found that hepatic but not extrahepatic insulin clearance is lower in the African American women, compared with their European American counterparts (Diabetes. 2017;66[10]:2564-70). Data from a cohort of children found the same thing (Diabetes Obes & Metab. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1111/dom.13471).

“What does this mean that different ethnic groups have different clearance of insulin?” he asked. “It means that African Americans deliver a higher fraction of secreted insulin into the systemic circulation. We know that African Americans tend to be hyperinsulinemic. That isn’t necessarily due to oversecretion of insulin; it’s likely due primarily to reduced degradation of insulin. The question then is, can the reduced insulin clearance play a causal role in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes?”

He hypothesized that, in normal individuals, half of insulin secreted by the pancreas is exported into the systemic circulation and half is degraded. “We propose that in people at risk for diabetes, insulin is secreted by the pancreas but much less of it is degraded,” Dr. Bergman continued. “Insulin gets into the systemic circulation, so then you can get hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance. The resistance stresses the beta cells of the pancreas. Thus, the idea is that differences in clearance of insulin by the liver in some individuals may be pathogenic in the cause of diabetes.”

Dr. Bergman reported that he has done consulting/collaboration with Janssen, January, Novo Nordisk, and Zafgen. He has also received research grants from Astra Zeneca, Janssen, and the National Institutes of Health.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCIRDC 2018

Postdiagnosis statin use lowers mortality rate for patients with HCC

Statin use after a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was associated with a reduced risk of all-cause and cancer-specific mortality, according to recent research published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“Our current findings are biologically plausible since statins inhibit not only cholesterol synthesis but also reduce other important downstream products, including membrane integrity maintenance, cell signaling, protein synthesis, and cell-cycle progression,” wrote Aaron P. Thrift, PhD, of the section of epidemiology and population sciences and department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and his colleagues. “Not only can statins have a direct impact on cancer cells through inhibition of the mevalonate pathway within the cancer cells, but the reduction of circulating cholesterol levels through hepatic pathways is indeed considered important.”

Dr. Thrift and his colleagues performed a retrospective cohort analysis of data from 15,422 patients with HCC in the VA Central Cancer Registry who were diagnosed between 2002 and 2016 and filled a prescription for statins. The researchers looked at statin prescriptions filled prior to and after diagnosis, following patients from diagnosis up to a 3-month lag period. The statins analyzed included atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin.

Overall, 78.8% of patients died during 26,680 person-years of follow-up and the median survival time was 17.24 months. The researchers found 14.9% of patients (2,293 patients) with HCC filled prescriptions for statins after their cancer diagnosis. The median time to begin statins after diagnosis was 2.37 months, and patients who used statins after diagnosis had a median survival time of 26.38 months compared with 15.67 months for patients who did not use statins after diagnosis. For HCC patients who used statins, there was a decreased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.95) and cancer-specific mortality (adjusted HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93), which was consistent for both high-dose and low-dose statins and for lag periods between 0 months and 12 months after diagnosis.

Limitations in the study were the exclusion of any statins filled at non-VA pharmacies, baseline differences in statin users and nonstatin users that could have affected results, potential misclassification of cirrhosis in the registry, and the lack of generalization to other populations due to a veteran-specific patient cohort.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and VA Health Services Research and Development Service Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety. The authors report having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thrift AP et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.046.

Statin use after a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was associated with a reduced risk of all-cause and cancer-specific mortality, according to recent research published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“Our current findings are biologically plausible since statins inhibit not only cholesterol synthesis but also reduce other important downstream products, including membrane integrity maintenance, cell signaling, protein synthesis, and cell-cycle progression,” wrote Aaron P. Thrift, PhD, of the section of epidemiology and population sciences and department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and his colleagues. “Not only can statins have a direct impact on cancer cells through inhibition of the mevalonate pathway within the cancer cells, but the reduction of circulating cholesterol levels through hepatic pathways is indeed considered important.”

Dr. Thrift and his colleagues performed a retrospective cohort analysis of data from 15,422 patients with HCC in the VA Central Cancer Registry who were diagnosed between 2002 and 2016 and filled a prescription for statins. The researchers looked at statin prescriptions filled prior to and after diagnosis, following patients from diagnosis up to a 3-month lag period. The statins analyzed included atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin.

Overall, 78.8% of patients died during 26,680 person-years of follow-up and the median survival time was 17.24 months. The researchers found 14.9% of patients (2,293 patients) with HCC filled prescriptions for statins after their cancer diagnosis. The median time to begin statins after diagnosis was 2.37 months, and patients who used statins after diagnosis had a median survival time of 26.38 months compared with 15.67 months for patients who did not use statins after diagnosis. For HCC patients who used statins, there was a decreased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.95) and cancer-specific mortality (adjusted HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93), which was consistent for both high-dose and low-dose statins and for lag periods between 0 months and 12 months after diagnosis.

Limitations in the study were the exclusion of any statins filled at non-VA pharmacies, baseline differences in statin users and nonstatin users that could have affected results, potential misclassification of cirrhosis in the registry, and the lack of generalization to other populations due to a veteran-specific patient cohort.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and VA Health Services Research and Development Service Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety. The authors report having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thrift AP et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.046.

Statin use after a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was associated with a reduced risk of all-cause and cancer-specific mortality, according to recent research published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“Our current findings are biologically plausible since statins inhibit not only cholesterol synthesis but also reduce other important downstream products, including membrane integrity maintenance, cell signaling, protein synthesis, and cell-cycle progression,” wrote Aaron P. Thrift, PhD, of the section of epidemiology and population sciences and department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and his colleagues. “Not only can statins have a direct impact on cancer cells through inhibition of the mevalonate pathway within the cancer cells, but the reduction of circulating cholesterol levels through hepatic pathways is indeed considered important.”

Dr. Thrift and his colleagues performed a retrospective cohort analysis of data from 15,422 patients with HCC in the VA Central Cancer Registry who were diagnosed between 2002 and 2016 and filled a prescription for statins. The researchers looked at statin prescriptions filled prior to and after diagnosis, following patients from diagnosis up to a 3-month lag period. The statins analyzed included atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin.

Overall, 78.8% of patients died during 26,680 person-years of follow-up and the median survival time was 17.24 months. The researchers found 14.9% of patients (2,293 patients) with HCC filled prescriptions for statins after their cancer diagnosis. The median time to begin statins after diagnosis was 2.37 months, and patients who used statins after diagnosis had a median survival time of 26.38 months compared with 15.67 months for patients who did not use statins after diagnosis. For HCC patients who used statins, there was a decreased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.95) and cancer-specific mortality (adjusted HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93), which was consistent for both high-dose and low-dose statins and for lag periods between 0 months and 12 months after diagnosis.

Limitations in the study were the exclusion of any statins filled at non-VA pharmacies, baseline differences in statin users and nonstatin users that could have affected results, potential misclassification of cirrhosis in the registry, and the lack of generalization to other populations due to a veteran-specific patient cohort.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and VA Health Services Research and Development Service Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety. The authors report having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thrift AP et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.046.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The use of statins after diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was associated with a lower risk of death.

Major finding: In 14.9% of patients who used statins after diagnosis, the rate of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.95) and cancer-specific mortality (adjusted HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93) was lower, and was consistent for both high-dose and low-dose statins.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 15,422 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the VA Central Cancer Registry between 2002 and 2016.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and VA Health Services Research and Development Service Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety. The authors report having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Thrift AP et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.046.

Patient-reported outcomes for patients with chronic liver disease

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and its complications such as decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide.1,2 In addition to its clinical impact, CLD causes impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and other patient-reported outcomes (PROs).1 Furthermore, patients with CLD use a substantial amount of health care resources, making CLD responsible for tremendous economic burden to the society.1,2

Although CLD encompasses a number of liver diseases, globally, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), as well as alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), are the most important causes of liver disease.1,2 In this context, recently developed treatment of HBV and HCV are highly effective. In contrast, there is no effective treatment for NASH and treatment of alcoholic steatohepatitis remains suboptimal.3 In the context of the growing burden of obesity and diabetes, the prevalence of NASH and its related complications are expected to grow.4

In recent years, a comprehensive approach to assessing the full burden of chronic diseases such as CLD has become increasingly recognized. In this context, it is important to evaluate not only the clinical burden of CLD (survival and mortality) but also its economic burden and its impact on PROs. PROs are defined as reports that come directly from the patient about their health without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or anyone else.5,6 Therefore, this commentary focuses on reviewing the assessment and interpretation of PROs in CLD and why they are important in clinical practice.

Assessment of patient-reported outcomes

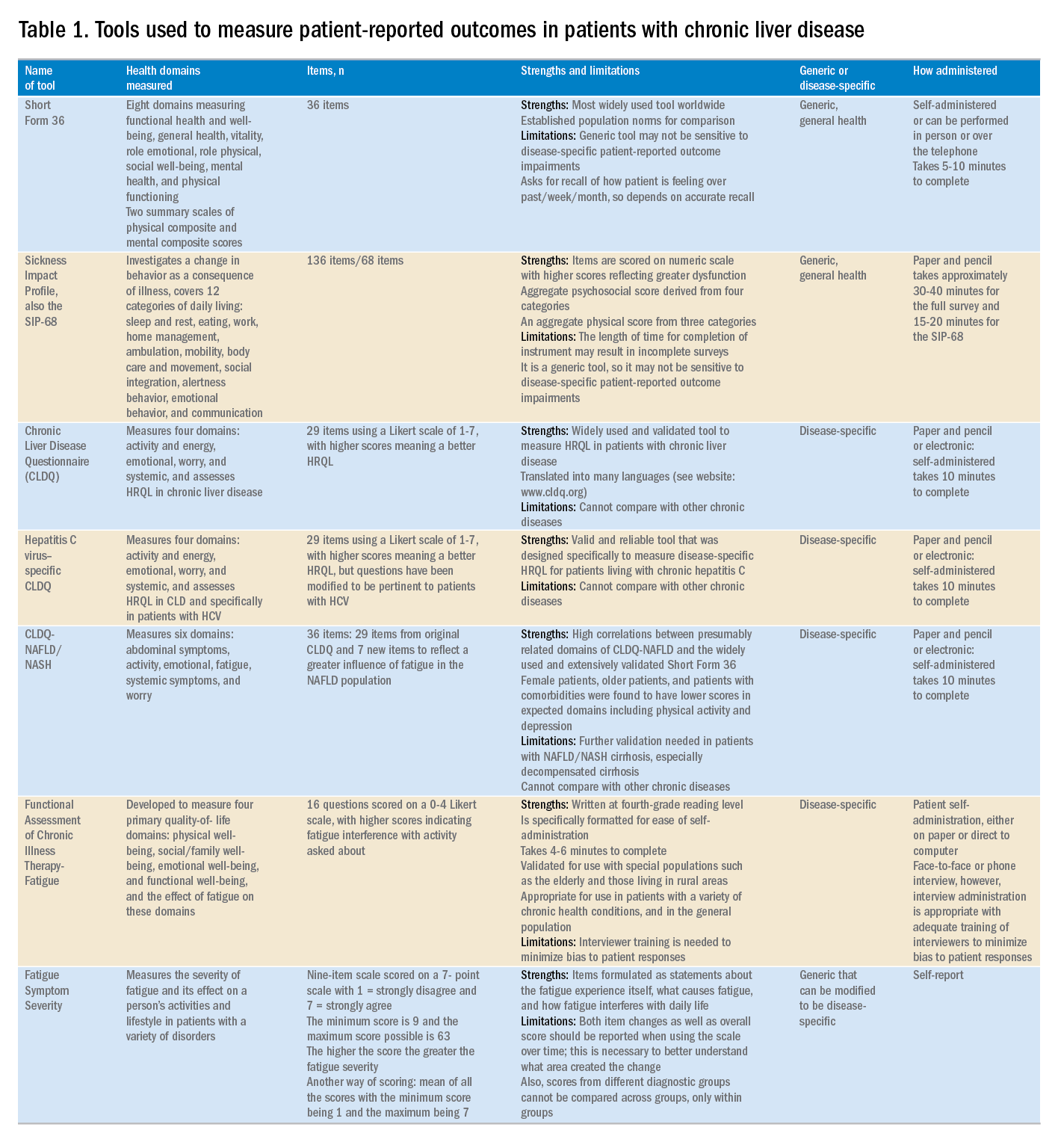

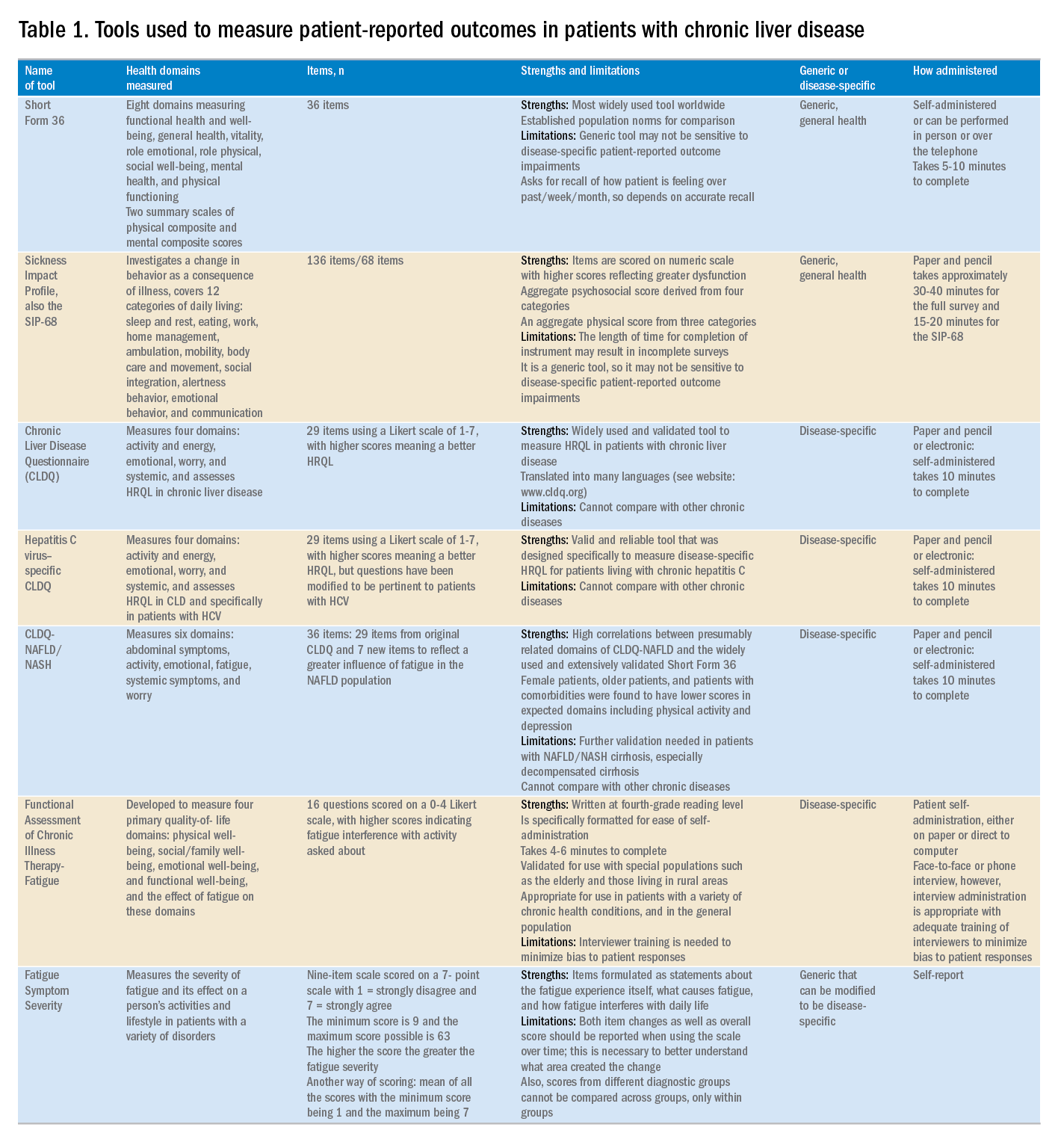

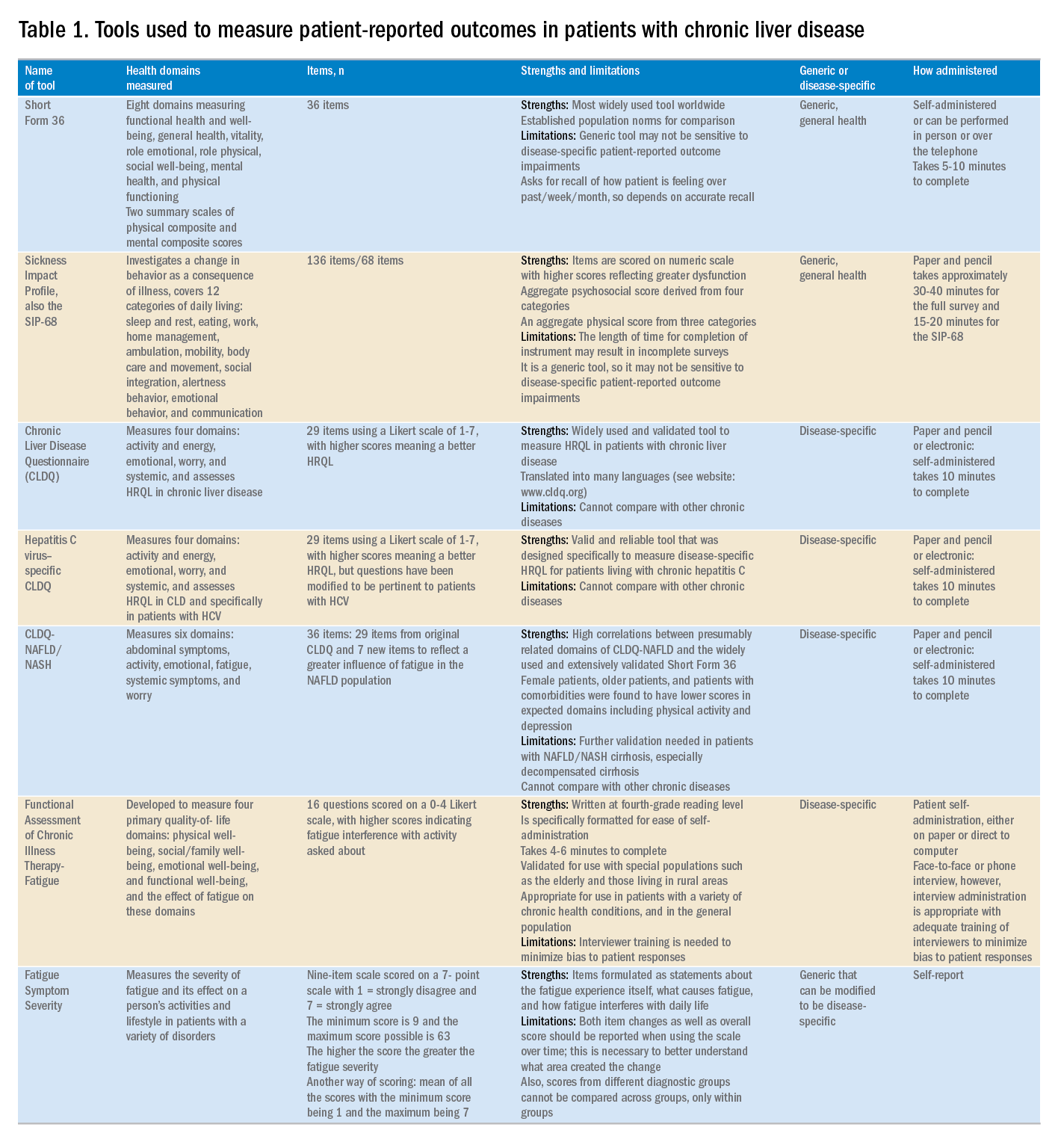

Although a number of PRO instruments are available, three different categories are most relevant for patients with CLD. In this context, PRO instruments can be divided into generic tools, disease-/condition-specific tools, or other instruments that specifically measure outcomes such as work or activity impairment (Table 1).

Generic HRQL tools measure overall health and its impact on patients’ quality of life. One of the most commonly used generic HRQL tools in liver disease is the Short Form-36 (SF-36) version 2. The SF-36 version 2 tool measures eight domains (scores, 0–100; with a higher score indicating less impairment) and provides two summary scores: one for physical functioning and one for mental health functioning. The SF-36 has been translated into multiple languages and provides age group– and disease-specific norms to use in comparison analysis.7 In addition to the SF-36, the Sickness Impact Profile also has been used to assess a change in behavior as a consequence of illness. The Sickness Impact Profile consists of 136 items/12 categories covering activities of daily living (sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior, emotional behavior, and communication). Items are scored on a numeric scale, with higher scores reflecting greater dysfunction as well as providing two aggregate scores: the psychosocial score, which is derived from four categories, and an aggregate physical score, which is calculated from three categories.8 Although generic instruments capture patients’ HRQL with different disease states (e.g., CLD vs. congestive heart failure), they may not have sufficient responsiveness to detect clinically important changes that can occur as a result of the natural history of disease or its treatment.9

For better responsiveness of HRQL instruments, disease-specific or condition-specific tools have been developed. These tools assess those aspects of HRQL that are related directly to the underlying disease. For patients with CLD, several tools have been developed and validated.10-12 One of the more popular tools is the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which was developed and validated for patients with CLD.10 The CLDQ has 29 items and 6 domains covering fatigue, activity, emotional function, abdominal symptoms, systemic symptoms, and worry.10 More recently, HCV-specific and NASH-specific versions of the CLDQ have been developed and validated (CLDQ-HCV and CLDQ–nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD]/NASH). The CLDQ-HCV instrument has some items from the original CLDQ with additional items specific to patients suffering from HCV. The CLDQ-HCV has 29 items that measure 4 domains: activity and energy, emotional, worry, and systemic, with high reliability and validity.11 Finally, the CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH was developed in a similar fashion to the CLDQ and CLDQ-HCV. The CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH has 36 items grouped into 6 domains: abdominal symptoms, activity, emotional, fatigue, systemic symptoms, and worry.12 All versions of the CLDQ are scored on a Likert scale of 1-7 nd domain scores are presented in the same manner. In addition, each version of the CLDQ can provide a total score, which also ranges from 1 to 7. In this context, the higher scores represent a better HRQL.10-12In addition to generic and disease-specific instruments, some investigators may elect to include other instruments that are designed specifically to capture fatigue, a very common symptom of CLD. These include the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, Fatigue Symptom Severity, and Fatigue Assessment Inventory.13,14

Finally, work productivity can be influenced profoundly by CLD and can be assessed by self-reports or questionnaires. One of these is the Work Productivity Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem questionnaire, which evaluates impairment in patients’ daily activities and work productivity associated with a specific health problem, and for patients with liver disease, patients are asked to think about how their disease state impacts their life. Higher impairment scores indicate a poorer health status and range from 0 to 1.15 An important aspect of the PRO assessment that is utilized in economic analysis measures health utilities. Health utilities are measured directly (time-trade off) or indirectly (SF6D, EQ5D, Health Utility Index). These assessment are from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Utility adjustments are used to combine qualty of life with quantity of life such as quality-adjusted years of life (QALY).16

Patient-reported outcome results for patients with chronic liver disease

Over the years, studies using these instruments have shown that patients with CLD suffer significant impairment in their PROs in all domains measured when compared with the population norms or with individuals without liver disease. Regardless of the cause of their CLD, patients with cirrhosis, especially with decompensated cirrhosis, have the most significant impairments.16,17 On the other hand, there is substantial evidence that standard treatment for decompensated cirrhosis (i.e., liver transplantation) can significantly improve HRQL and other PROs in patients with advanced cirrhosis.18

In addition to the data for patients with advanced liver disease, there is a significant amount of PRO data that has been generated for patients with early liver disease. In this context, treatment of HCV with the new interferon-free direct antiviral agents results in substantial PRO gains during treatment and after achieving sustained virologic response.19 In fact, these improvements in PROs have been captured by disease-specific, generic, fatigue-specific, and work productivity instruments.19

In contrast to HCV, PRO data for patients with HBV are limited. Nevertheless, recent data have suggested that HBV patients who have viral suppression with a nucleoside/nucleotide analogue have a better HRQL.20 Finally, PRO assessments in subjects with NASH are in their early stages. In this context, HRQL data from patients with NASH show significant impairment, which worsens with advanced liver disease.21,22 In addition, preliminary data suggest that improvement of fibrosis with medication can lead to improvement of some aspects of PROs in NASH.23,24

Clinical practice and patient-reported outcomes

The first challenge in the implementation of PRO assessment in clinical practice is the appreciation and understanding of the practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists about its importance and relevance to clinicians. Generally, clinicians are more focused on the classic markers of disease activity and severity (laboratory tests, and so forth), rather than those that measure patient experiences (PROs). Given that patient experience increasingly has become an important indicator of quality of care, this issue may become increasingly important in clinical practice. In addition, it is important to remember that PROs are the most important outcomes from the patient’s perspective. Another challenge in implementation of PROs in clinical practice is to choose the correct validated tool and to implement PRO assessment during an office visit. In fact, completing long questionnaires takes time and resources, which may not be feasible for a busy clinic. Furthermore, these assessments are not reimbursed by payers, which leave the burden of the PRO assessment and counseling of patients about their interpretation to the clinicians or their clinical staff. Although the other challenges are easier to solve, covering the cost of administration and counseling patients about interventions to improve their PROs can be substantial. In liver disease, the best and easiest tool to use is a validated disease-specific instrument (such as the CLDQ), which takes no more than 10 minutes to complete. In fact, these instruments can be completed electronically either during the office visit or before the visit through secure web access. Nevertheless, all of these efforts require strong emphasis and desire to assess the patient’s perspective about their disease and its treatment and to manage their quality of life accordingly.

In summary, the armamentarium of PRO tools used in multiple studies of CLD have provided excellent insight into the PRO burden of CLD, and their treatments from the patient’s perspective thus are an important part of health care workers’ interaction with patients. Work continues in understanding the impact of other liver diseases on PROs but with the current knowledge about PROs, clinicians should be encouraged to use this information when formulating their treatment plan.25 Finally, seamless implementation of PRO assessments in the clinical setting in a cost-effective manner remains a challenge and should be addressed in the future.

References

1. Afendy A, Kallman JB, Stepanova M, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;30:469-76.

2. Sarin SK, Maiwall R. Global burden of liver disease: a true burden on health sciences and economies. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/publications/e-wgn/e-wgn-expert-point-of-view-articles-collection/global-burden-of-liver-disease-a-true-burden-on-health-sciences-and-economies. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

3. Younossi Z, Henry L. Contribution of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to the burden of liver-related morbidity and mortality. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1778-85.

4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

5. Younossi ZM, Park H, Dieterich D, et al. Assessment of cost of innovation versus the value of health gains associated with treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the United States: the quality-adjusted cost of care. Medicine. (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5048.

6. Centers for Disease Control–Health Related Quality of Life. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HRQoL/concept.htm. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

7. Ware JE, Kosinski M. Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:405-20.

8. De Bruin A, Diederiks J, De Witte L, et al. The development of a short generic version of the Sickness Impact Profile. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:407-12.

9. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trial. 1989;10:407-15.

10. Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwia M, et al. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295-300.

11. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L. Performance and validation of Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-Hepatitis C Version (CLDQ-HCV) in clinical trials of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Value Health. 2016;19:544-51.

12. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. A disease-specific quality of life instrument for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: CLDQ-NAFLD. Liver Int. 2017;37:1209-18.

13. Webster K, Odom L, Peterman A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: validation of version 4 of the core questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:604.

14. Golabi P, Sayiner M, Bush H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:565-78.

15. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

16. Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;15:301.

17. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

18. Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. Quality of life and mental health comparisons among liver transplant recipients and cirrhotic patients with different self-perceptions of health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:97-106.

19. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. An in-depth analysis of patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with different anti-viral regimens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:808-16.

20. Weinstein AA, Price Kallman J, Stepanova M, et al. Depression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:127-32.

21. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Jacobson IM, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without voxilaprevir in direct-acting antiviral-naïve chronic hepatitis C: patient-reported outcomes from POLARIS 2 and 3. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:259-67.

22. Sayiner M, Stepanova M, Pham H, et al. Assessment of health utilities and quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000106.

23. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Gordon S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir, with or without Voxilaprevir. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:567-74.

24. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

25. Younossi Z. What Is the ethical responsibility of a provider when prescribing the new direct-acting antiviral agents to patients with hepatitis C infection? Clin Liver Dis. 2015;6:117-9.

Dr. Younossi is at the Center for Liver Diseases, chair, Department of Medicine, professor of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va; and the Betty and Guy Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Inova Health System, Falls Church. He has received research funding and is a consultant with Abbvie, Intercept, BMS, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Shinogi, Terns, and Viking.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and its complications such as decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide.1,2 In addition to its clinical impact, CLD causes impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and other patient-reported outcomes (PROs).1 Furthermore, patients with CLD use a substantial amount of health care resources, making CLD responsible for tremendous economic burden to the society.1,2

Although CLD encompasses a number of liver diseases, globally, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), as well as alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), are the most important causes of liver disease.1,2 In this context, recently developed treatment of HBV and HCV are highly effective. In contrast, there is no effective treatment for NASH and treatment of alcoholic steatohepatitis remains suboptimal.3 In the context of the growing burden of obesity and diabetes, the prevalence of NASH and its related complications are expected to grow.4

In recent years, a comprehensive approach to assessing the full burden of chronic diseases such as CLD has become increasingly recognized. In this context, it is important to evaluate not only the clinical burden of CLD (survival and mortality) but also its economic burden and its impact on PROs. PROs are defined as reports that come directly from the patient about their health without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or anyone else.5,6 Therefore, this commentary focuses on reviewing the assessment and interpretation of PROs in CLD and why they are important in clinical practice.

Assessment of patient-reported outcomes

Although a number of PRO instruments are available, three different categories are most relevant for patients with CLD. In this context, PRO instruments can be divided into generic tools, disease-/condition-specific tools, or other instruments that specifically measure outcomes such as work or activity impairment (Table 1).

Generic HRQL tools measure overall health and its impact on patients’ quality of life. One of the most commonly used generic HRQL tools in liver disease is the Short Form-36 (SF-36) version 2. The SF-36 version 2 tool measures eight domains (scores, 0–100; with a higher score indicating less impairment) and provides two summary scores: one for physical functioning and one for mental health functioning. The SF-36 has been translated into multiple languages and provides age group– and disease-specific norms to use in comparison analysis.7 In addition to the SF-36, the Sickness Impact Profile also has been used to assess a change in behavior as a consequence of illness. The Sickness Impact Profile consists of 136 items/12 categories covering activities of daily living (sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior, emotional behavior, and communication). Items are scored on a numeric scale, with higher scores reflecting greater dysfunction as well as providing two aggregate scores: the psychosocial score, which is derived from four categories, and an aggregate physical score, which is calculated from three categories.8 Although generic instruments capture patients’ HRQL with different disease states (e.g., CLD vs. congestive heart failure), they may not have sufficient responsiveness to detect clinically important changes that can occur as a result of the natural history of disease or its treatment.9

For better responsiveness of HRQL instruments, disease-specific or condition-specific tools have been developed. These tools assess those aspects of HRQL that are related directly to the underlying disease. For patients with CLD, several tools have been developed and validated.10-12 One of the more popular tools is the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which was developed and validated for patients with CLD.10 The CLDQ has 29 items and 6 domains covering fatigue, activity, emotional function, abdominal symptoms, systemic symptoms, and worry.10 More recently, HCV-specific and NASH-specific versions of the CLDQ have been developed and validated (CLDQ-HCV and CLDQ–nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD]/NASH). The CLDQ-HCV instrument has some items from the original CLDQ with additional items specific to patients suffering from HCV. The CLDQ-HCV has 29 items that measure 4 domains: activity and energy, emotional, worry, and systemic, with high reliability and validity.11 Finally, the CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH was developed in a similar fashion to the CLDQ and CLDQ-HCV. The CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH has 36 items grouped into 6 domains: abdominal symptoms, activity, emotional, fatigue, systemic symptoms, and worry.12 All versions of the CLDQ are scored on a Likert scale of 1-7 nd domain scores are presented in the same manner. In addition, each version of the CLDQ can provide a total score, which also ranges from 1 to 7. In this context, the higher scores represent a better HRQL.10-12In addition to generic and disease-specific instruments, some investigators may elect to include other instruments that are designed specifically to capture fatigue, a very common symptom of CLD. These include the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, Fatigue Symptom Severity, and Fatigue Assessment Inventory.13,14

Finally, work productivity can be influenced profoundly by CLD and can be assessed by self-reports or questionnaires. One of these is the Work Productivity Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem questionnaire, which evaluates impairment in patients’ daily activities and work productivity associated with a specific health problem, and for patients with liver disease, patients are asked to think about how their disease state impacts their life. Higher impairment scores indicate a poorer health status and range from 0 to 1.15 An important aspect of the PRO assessment that is utilized in economic analysis measures health utilities. Health utilities are measured directly (time-trade off) or indirectly (SF6D, EQ5D, Health Utility Index). These assessment are from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Utility adjustments are used to combine qualty of life with quantity of life such as quality-adjusted years of life (QALY).16

Patient-reported outcome results for patients with chronic liver disease

Over the years, studies using these instruments have shown that patients with CLD suffer significant impairment in their PROs in all domains measured when compared with the population norms or with individuals without liver disease. Regardless of the cause of their CLD, patients with cirrhosis, especially with decompensated cirrhosis, have the most significant impairments.16,17 On the other hand, there is substantial evidence that standard treatment for decompensated cirrhosis (i.e., liver transplantation) can significantly improve HRQL and other PROs in patients with advanced cirrhosis.18

In addition to the data for patients with advanced liver disease, there is a significant amount of PRO data that has been generated for patients with early liver disease. In this context, treatment of HCV with the new interferon-free direct antiviral agents results in substantial PRO gains during treatment and after achieving sustained virologic response.19 In fact, these improvements in PROs have been captured by disease-specific, generic, fatigue-specific, and work productivity instruments.19

In contrast to HCV, PRO data for patients with HBV are limited. Nevertheless, recent data have suggested that HBV patients who have viral suppression with a nucleoside/nucleotide analogue have a better HRQL.20 Finally, PRO assessments in subjects with NASH are in their early stages. In this context, HRQL data from patients with NASH show significant impairment, which worsens with advanced liver disease.21,22 In addition, preliminary data suggest that improvement of fibrosis with medication can lead to improvement of some aspects of PROs in NASH.23,24

Clinical practice and patient-reported outcomes

The first challenge in the implementation of PRO assessment in clinical practice is the appreciation and understanding of the practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists about its importance and relevance to clinicians. Generally, clinicians are more focused on the classic markers of disease activity and severity (laboratory tests, and so forth), rather than those that measure patient experiences (PROs). Given that patient experience increasingly has become an important indicator of quality of care, this issue may become increasingly important in clinical practice. In addition, it is important to remember that PROs are the most important outcomes from the patient’s perspective. Another challenge in implementation of PROs in clinical practice is to choose the correct validated tool and to implement PRO assessment during an office visit. In fact, completing long questionnaires takes time and resources, which may not be feasible for a busy clinic. Furthermore, these assessments are not reimbursed by payers, which leave the burden of the PRO assessment and counseling of patients about their interpretation to the clinicians or their clinical staff. Although the other challenges are easier to solve, covering the cost of administration and counseling patients about interventions to improve their PROs can be substantial. In liver disease, the best and easiest tool to use is a validated disease-specific instrument (such as the CLDQ), which takes no more than 10 minutes to complete. In fact, these instruments can be completed electronically either during the office visit or before the visit through secure web access. Nevertheless, all of these efforts require strong emphasis and desire to assess the patient’s perspective about their disease and its treatment and to manage their quality of life accordingly.

In summary, the armamentarium of PRO tools used in multiple studies of CLD have provided excellent insight into the PRO burden of CLD, and their treatments from the patient’s perspective thus are an important part of health care workers’ interaction with patients. Work continues in understanding the impact of other liver diseases on PROs but with the current knowledge about PROs, clinicians should be encouraged to use this information when formulating their treatment plan.25 Finally, seamless implementation of PRO assessments in the clinical setting in a cost-effective manner remains a challenge and should be addressed in the future.

References

1. Afendy A, Kallman JB, Stepanova M, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;30:469-76.

2. Sarin SK, Maiwall R. Global burden of liver disease: a true burden on health sciences and economies. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/publications/e-wgn/e-wgn-expert-point-of-view-articles-collection/global-burden-of-liver-disease-a-true-burden-on-health-sciences-and-economies. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

3. Younossi Z, Henry L. Contribution of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to the burden of liver-related morbidity and mortality. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1778-85.

4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

5. Younossi ZM, Park H, Dieterich D, et al. Assessment of cost of innovation versus the value of health gains associated with treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the United States: the quality-adjusted cost of care. Medicine. (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5048.

6. Centers for Disease Control–Health Related Quality of Life. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HRQoL/concept.htm. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

7. Ware JE, Kosinski M. Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:405-20.

8. De Bruin A, Diederiks J, De Witte L, et al. The development of a short generic version of the Sickness Impact Profile. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:407-12.

9. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trial. 1989;10:407-15.

10. Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwia M, et al. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295-300.

11. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L. Performance and validation of Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-Hepatitis C Version (CLDQ-HCV) in clinical trials of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Value Health. 2016;19:544-51.

12. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. A disease-specific quality of life instrument for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: CLDQ-NAFLD. Liver Int. 2017;37:1209-18.

13. Webster K, Odom L, Peterman A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: validation of version 4 of the core questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:604.

14. Golabi P, Sayiner M, Bush H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:565-78.

15. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

16. Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;15:301.

17. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

18. Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. Quality of life and mental health comparisons among liver transplant recipients and cirrhotic patients with different self-perceptions of health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:97-106.

19. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. An in-depth analysis of patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with different anti-viral regimens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:808-16.

20. Weinstein AA, Price Kallman J, Stepanova M, et al. Depression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:127-32.

21. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Jacobson IM, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without voxilaprevir in direct-acting antiviral-naïve chronic hepatitis C: patient-reported outcomes from POLARIS 2 and 3. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:259-67.

22. Sayiner M, Stepanova M, Pham H, et al. Assessment of health utilities and quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000106.

23. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Gordon S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir, with or without Voxilaprevir. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:567-74.

24. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

25. Younossi Z. What Is the ethical responsibility of a provider when prescribing the new direct-acting antiviral agents to patients with hepatitis C infection? Clin Liver Dis. 2015;6:117-9.

Dr. Younossi is at the Center for Liver Diseases, chair, Department of Medicine, professor of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va; and the Betty and Guy Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Inova Health System, Falls Church. He has received research funding and is a consultant with Abbvie, Intercept, BMS, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Shinogi, Terns, and Viking.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) and its complications such as decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are major causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide.1,2 In addition to its clinical impact, CLD causes impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQL) and other patient-reported outcomes (PROs).1 Furthermore, patients with CLD use a substantial amount of health care resources, making CLD responsible for tremendous economic burden to the society.1,2

Although CLD encompasses a number of liver diseases, globally, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), as well as alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), are the most important causes of liver disease.1,2 In this context, recently developed treatment of HBV and HCV are highly effective. In contrast, there is no effective treatment for NASH and treatment of alcoholic steatohepatitis remains suboptimal.3 In the context of the growing burden of obesity and diabetes, the prevalence of NASH and its related complications are expected to grow.4

In recent years, a comprehensive approach to assessing the full burden of chronic diseases such as CLD has become increasingly recognized. In this context, it is important to evaluate not only the clinical burden of CLD (survival and mortality) but also its economic burden and its impact on PROs. PROs are defined as reports that come directly from the patient about their health without amendment or interpretation by a clinician or anyone else.5,6 Therefore, this commentary focuses on reviewing the assessment and interpretation of PROs in CLD and why they are important in clinical practice.

Assessment of patient-reported outcomes

Although a number of PRO instruments are available, three different categories are most relevant for patients with CLD. In this context, PRO instruments can be divided into generic tools, disease-/condition-specific tools, or other instruments that specifically measure outcomes such as work or activity impairment (Table 1).

Generic HRQL tools measure overall health and its impact on patients’ quality of life. One of the most commonly used generic HRQL tools in liver disease is the Short Form-36 (SF-36) version 2. The SF-36 version 2 tool measures eight domains (scores, 0–100; with a higher score indicating less impairment) and provides two summary scores: one for physical functioning and one for mental health functioning. The SF-36 has been translated into multiple languages and provides age group– and disease-specific norms to use in comparison analysis.7 In addition to the SF-36, the Sickness Impact Profile also has been used to assess a change in behavior as a consequence of illness. The Sickness Impact Profile consists of 136 items/12 categories covering activities of daily living (sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior, emotional behavior, and communication). Items are scored on a numeric scale, with higher scores reflecting greater dysfunction as well as providing two aggregate scores: the psychosocial score, which is derived from four categories, and an aggregate physical score, which is calculated from three categories.8 Although generic instruments capture patients’ HRQL with different disease states (e.g., CLD vs. congestive heart failure), they may not have sufficient responsiveness to detect clinically important changes that can occur as a result of the natural history of disease or its treatment.9

For better responsiveness of HRQL instruments, disease-specific or condition-specific tools have been developed. These tools assess those aspects of HRQL that are related directly to the underlying disease. For patients with CLD, several tools have been developed and validated.10-12 One of the more popular tools is the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), which was developed and validated for patients with CLD.10 The CLDQ has 29 items and 6 domains covering fatigue, activity, emotional function, abdominal symptoms, systemic symptoms, and worry.10 More recently, HCV-specific and NASH-specific versions of the CLDQ have been developed and validated (CLDQ-HCV and CLDQ–nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD]/NASH). The CLDQ-HCV instrument has some items from the original CLDQ with additional items specific to patients suffering from HCV. The CLDQ-HCV has 29 items that measure 4 domains: activity and energy, emotional, worry, and systemic, with high reliability and validity.11 Finally, the CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH was developed in a similar fashion to the CLDQ and CLDQ-HCV. The CLDQ-NAFLD/NASH has 36 items grouped into 6 domains: abdominal symptoms, activity, emotional, fatigue, systemic symptoms, and worry.12 All versions of the CLDQ are scored on a Likert scale of 1-7 nd domain scores are presented in the same manner. In addition, each version of the CLDQ can provide a total score, which also ranges from 1 to 7. In this context, the higher scores represent a better HRQL.10-12In addition to generic and disease-specific instruments, some investigators may elect to include other instruments that are designed specifically to capture fatigue, a very common symptom of CLD. These include the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, Fatigue Symptom Severity, and Fatigue Assessment Inventory.13,14

Finally, work productivity can be influenced profoundly by CLD and can be assessed by self-reports or questionnaires. One of these is the Work Productivity Activity Impairment: Specific Health Problem questionnaire, which evaluates impairment in patients’ daily activities and work productivity associated with a specific health problem, and for patients with liver disease, patients are asked to think about how their disease state impacts their life. Higher impairment scores indicate a poorer health status and range from 0 to 1.15 An important aspect of the PRO assessment that is utilized in economic analysis measures health utilities. Health utilities are measured directly (time-trade off) or indirectly (SF6D, EQ5D, Health Utility Index). These assessment are from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). Utility adjustments are used to combine qualty of life with quantity of life such as quality-adjusted years of life (QALY).16

Patient-reported outcome results for patients with chronic liver disease

Over the years, studies using these instruments have shown that patients with CLD suffer significant impairment in their PROs in all domains measured when compared with the population norms or with individuals without liver disease. Regardless of the cause of their CLD, patients with cirrhosis, especially with decompensated cirrhosis, have the most significant impairments.16,17 On the other hand, there is substantial evidence that standard treatment for decompensated cirrhosis (i.e., liver transplantation) can significantly improve HRQL and other PROs in patients with advanced cirrhosis.18

In addition to the data for patients with advanced liver disease, there is a significant amount of PRO data that has been generated for patients with early liver disease. In this context, treatment of HCV with the new interferon-free direct antiviral agents results in substantial PRO gains during treatment and after achieving sustained virologic response.19 In fact, these improvements in PROs have been captured by disease-specific, generic, fatigue-specific, and work productivity instruments.19

In contrast to HCV, PRO data for patients with HBV are limited. Nevertheless, recent data have suggested that HBV patients who have viral suppression with a nucleoside/nucleotide analogue have a better HRQL.20 Finally, PRO assessments in subjects with NASH are in their early stages. In this context, HRQL data from patients with NASH show significant impairment, which worsens with advanced liver disease.21,22 In addition, preliminary data suggest that improvement of fibrosis with medication can lead to improvement of some aspects of PROs in NASH.23,24

Clinical practice and patient-reported outcomes

The first challenge in the implementation of PRO assessment in clinical practice is the appreciation and understanding of the practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists about its importance and relevance to clinicians. Generally, clinicians are more focused on the classic markers of disease activity and severity (laboratory tests, and so forth), rather than those that measure patient experiences (PROs). Given that patient experience increasingly has become an important indicator of quality of care, this issue may become increasingly important in clinical practice. In addition, it is important to remember that PROs are the most important outcomes from the patient’s perspective. Another challenge in implementation of PROs in clinical practice is to choose the correct validated tool and to implement PRO assessment during an office visit. In fact, completing long questionnaires takes time and resources, which may not be feasible for a busy clinic. Furthermore, these assessments are not reimbursed by payers, which leave the burden of the PRO assessment and counseling of patients about their interpretation to the clinicians or their clinical staff. Although the other challenges are easier to solve, covering the cost of administration and counseling patients about interventions to improve their PROs can be substantial. In liver disease, the best and easiest tool to use is a validated disease-specific instrument (such as the CLDQ), which takes no more than 10 minutes to complete. In fact, these instruments can be completed electronically either during the office visit or before the visit through secure web access. Nevertheless, all of these efforts require strong emphasis and desire to assess the patient’s perspective about their disease and its treatment and to manage their quality of life accordingly.

In summary, the armamentarium of PRO tools used in multiple studies of CLD have provided excellent insight into the PRO burden of CLD, and their treatments from the patient’s perspective thus are an important part of health care workers’ interaction with patients. Work continues in understanding the impact of other liver diseases on PROs but with the current knowledge about PROs, clinicians should be encouraged to use this information when formulating their treatment plan.25 Finally, seamless implementation of PRO assessments in the clinical setting in a cost-effective manner remains a challenge and should be addressed in the future.

References

1. Afendy A, Kallman JB, Stepanova M, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2009;30:469-76.

2. Sarin SK, Maiwall R. Global burden of liver disease: a true burden on health sciences and economies. Available from: http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/publications/e-wgn/e-wgn-expert-point-of-view-articles-collection/global-burden-of-liver-disease-a-true-burden-on-health-sciences-and-economies. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

3. Younossi Z, Henry L. Contribution of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to the burden of liver-related morbidity and mortality. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1778-85.

4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

5. Younossi ZM, Park H, Dieterich D, et al. Assessment of cost of innovation versus the value of health gains associated with treatment of chronic hepatitis C in the United States: the quality-adjusted cost of care. Medicine. (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5048.

6. Centers for Disease Control–Health Related Quality of Life. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/HRQoL/concept.htm. Accessed: August 31, 2017.

7. Ware JE, Kosinski M. Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:405-20.

8. De Bruin A, Diederiks J, De Witte L, et al. The development of a short generic version of the Sickness Impact Profile. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:407-12.

9. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trial. 1989;10:407-15.

10. Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwia M, et al. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 1999;45:295-300.

11. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L. Performance and validation of Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-Hepatitis C Version (CLDQ-HCV) in clinical trials of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Value Health. 2016;19:544-51.

12. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. A disease-specific quality of life instrument for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: CLDQ-NAFLD. Liver Int. 2017;37:1209-18.

13. Webster K, Odom L, Peterman A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: validation of version 4 of the core questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:604.

14. Golabi P, Sayiner M, Bush H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:565-78.

15. Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353-65.

16. Loria A, Escheik C, Gerber NL, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;15:301.

17. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

18. Pérez-San-Gregorio MÁ, Martín-Rodríguez A, Domínguez-Cabello E, et al. Quality of life and mental health comparisons among liver transplant recipients and cirrhotic patients with different self-perceptions of health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:97-106.

19. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. An in-depth analysis of patient-reported outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with different anti-viral regimens. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:808-16.

20. Weinstein AA, Price Kallman J, Stepanova M, et al. Depression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:127-32.

21. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Jacobson IM, et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without voxilaprevir in direct-acting antiviral-naïve chronic hepatitis C: patient-reported outcomes from POLARIS 2 and 3. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:259-67.

22. Sayiner M, Stepanova M, Pham H, et al. Assessment of health utilities and quality of life in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3:e000106.

23. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Gordon S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir, with or without Voxilaprevir. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:567-74.

24. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Charlton M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus-related decompensated cirrhosis: an exploratory analysis from the randomised, open-label ASTRAL-4 phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:122-32.

25. Younossi Z. What Is the ethical responsibility of a provider when prescribing the new direct-acting antiviral agents to patients with hepatitis C infection? Clin Liver Dis. 2015;6:117-9.

Dr. Younossi is at the Center for Liver Diseases, chair, Department of Medicine, professor of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va; and the Betty and Guy Beatty Center for Integrated Research, Inova Health System, Falls Church. He has received research funding and is a consultant with Abbvie, Intercept, BMS, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Shinogi, Terns, and Viking.

Biomarker algorithm may offer noninvasive look at liver fibrosis

Serum biomarkers may enable a noninvasive method of detecting advanced hepatic fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according to results from a recent study.

An algorithm created by the investigators distinguished NAFLD patients with advanced liver fibrosis from those with mild to moderate fibrosis, reported lead author Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California at San Diego and his colleagues.

“Liver biopsy is currently the gold standard for diagnosing NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] and staging liver fibrosis,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, it is a costly and invasive procedure with an all-cause mortality risk of approximately 0.2%. Liver biopsy typically samples only 1/50,000th of the organ, and it is liable to sampling error with an error rate of 25% for diagnosis of hepatic fibrosis.”

Existing serum-based tests are reliable for diagnosing nonfibrotic NAFLD, but they may misdiagnosis patients with advanced fibrosis. Although imaging-based techniques may provide better diagnostic accuracy, some are available only for subgroups of patients, while others come with a high financial burden. Diagnostic shortcomings may have a major effect on patient outcomes, particularly when risk groups are considered.

“Fibrosis stages F3 and F4 (advanced fibrosis) are primary predictors of liver-related morbidity and mortality, with 11%-22% of NASH patients reported to have advanced fibrosis,” the investigators noted.

The investigators therefore aimed to distinguish such high-risk NAFLD patients from those with mild or moderate liver fibrosis. Three biomarkers were included: hyaluronic acid (HA), TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP-1), and alpha2-macroglobulin (A2M). Each biomarker has documented associations with liver fibrosis. For instance, higher A2M concentrations inhibit fibrinolysis, HA is associated with excessive extracellular matrix and fibrotic tissue, and TIMP-1 is a known liver fibrosis marker and inhibitor of extracellular matrix degradation. The relative strengths of each in detecting advanced liver fibrosis was determined through an algorithm.

The investigators relied on archived serum samples from Duke University, Durham, N.C., (n = 792) and University of California at San Diego (n = 244) that were collected within 11 days of liver biopsy. Biopsies were performed with 15- to 16-gauge needles using at least eight portal tracts, and these samples were used to diagnose NAFLD. Patients with alcoholic liver disease or hepatitis C virus were excluded.

Algorithm training was based on serum measurements from 396 patients treated at Duke University. Samples were divided into mild to moderate (F0-F2) or advanced (F3-F4) fibrosis and split into 10 subsets. The logical regression model was trained on nine subsets and tested on the 10th, with iterations 10 times through this sequence until all 10 samples were tested. This process was repeated 10,000 times. Using the median coefficients from 100,000 logistical regression models, the samples were scored using the algorithm from 0 to 100, with higher numbers representing more advanced fibrosis, and the relative weights of each biomarker measurement were determined.

A noninferiority protocol was used to validate the algorithm, through which the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve was calculated. The AUROC curve of the validation samples was 0.856, with 0.5 being the score for a random algorithm. The algorithm correctly classified 90.0% of F0 cases, 75.0% of F1 cases, 53.8% of F2 cases, 77.4% of F3 cases, and 94.4% of F4 cases. The sensitivity was 79.7% and the specificity was 75.7%.

The algorithm was superior to Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) and NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS) in two validation cohorts. In a combination of validation cohorts, the algorithm correctly identified 79.5% of F3-F4 patients, compared with rates of 25.8% and 28.0% from FIB-4 and NFS, respectively. The investigators noted that the algorithm was unaffected by sex or age. In contrast, FIB-4 is biased toward females, and both FIB-4 and NFS are less accurate with patients aged 35 years or younger.

“Performance of the training and validation sets was robust and well matched, enabling the reliable differentiation of NAFLD patients with and without advanced fibrosis,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by Prometheus Laboratories. Authors not employed by Prometheus Laboratories were employed by Duke University or the University of California, San Diego; each institution received funding from Prometheus Laboratories.

SOURCE: Loomba R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.004.

Serum biomarkers may enable a noninvasive method of detecting advanced hepatic fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according to results from a recent study.

An algorithm created by the investigators distinguished NAFLD patients with advanced liver fibrosis from those with mild to moderate fibrosis, reported lead author Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California at San Diego and his colleagues.

“Liver biopsy is currently the gold standard for diagnosing NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] and staging liver fibrosis,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, it is a costly and invasive procedure with an all-cause mortality risk of approximately 0.2%. Liver biopsy typically samples only 1/50,000th of the organ, and it is liable to sampling error with an error rate of 25% for diagnosis of hepatic fibrosis.”

Existing serum-based tests are reliable for diagnosing nonfibrotic NAFLD, but they may misdiagnosis patients with advanced fibrosis. Although imaging-based techniques may provide better diagnostic accuracy, some are available only for subgroups of patients, while others come with a high financial burden. Diagnostic shortcomings may have a major effect on patient outcomes, particularly when risk groups are considered.

“Fibrosis stages F3 and F4 (advanced fibrosis) are primary predictors of liver-related morbidity and mortality, with 11%-22% of NASH patients reported to have advanced fibrosis,” the investigators noted.

The investigators therefore aimed to distinguish such high-risk NAFLD patients from those with mild or moderate liver fibrosis. Three biomarkers were included: hyaluronic acid (HA), TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP-1), and alpha2-macroglobulin (A2M). Each biomarker has documented associations with liver fibrosis. For instance, higher A2M concentrations inhibit fibrinolysis, HA is associated with excessive extracellular matrix and fibrotic tissue, and TIMP-1 is a known liver fibrosis marker and inhibitor of extracellular matrix degradation. The relative strengths of each in detecting advanced liver fibrosis was determined through an algorithm.

The investigators relied on archived serum samples from Duke University, Durham, N.C., (n = 792) and University of California at San Diego (n = 244) that were collected within 11 days of liver biopsy. Biopsies were performed with 15- to 16-gauge needles using at least eight portal tracts, and these samples were used to diagnose NAFLD. Patients with alcoholic liver disease or hepatitis C virus were excluded.