User login

New lung cancer screening guideline from CHEST

An update to CHEST’s lung cancer screening guideline, Screening for Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report, has just been published online in the journal CHEST®. This update was made possible by the hard work of my co-authors and the amazing support of the CHEST staff.

Our goal was to update the evidence base for the benefit, harms, and implementation of low-radiation dose chest CT screening, then use this evidence base to produce meaningful and usable recommendations. The process for developing the guideline followed the rigorous methodological standards of CHEST in which the evidence was gathered from a systematic literature review, and the overall quality of the body of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach. Recommendations were developed and graded based on this assessment.

There are a few aspects of the new guidelines to highlight. First, we have updated some of the core recommendations; second, we have developed new recommendations related to the implementation of high-quality screening; and third, the CHEST approach to guideline development has evolved to allow us to provide recommendations in which the evidence allows and statements based on experience and expert consensus in which it does not. Through this process, we developed six graded recommendations and nine ungraded consensus-based statements.

In this update, a few changes to the core recommendations about who should be screened are worthy to note:

- We have recommended an increase to the upper age of the screen-eligible cohort from 74 to 77, in line with CMS coverage and reflecting the oldest age of participants in the National Lung Screening Trial at the end of the screening period.

- We have directly addressed the cohort of individuals who are at high risk for having/developing lung cancer based on clinical risk prediction calculators but do not meet the current eligibility criteria. We recommended that this cohort should not be routinely screened given the greater potential for this cohort to have comorbid conditions that would influence morbidity from the evaluation and treatment of screen-detected findings and death from any cause. We did, however, state that there will be individuals within the cohort deemed to be at high risk for lung cancer from a clinical risk prediction calculator who are healthy enough to benefit from lung cancer screening and that low-radiation dose CT screening could be considered in these individuals.

- We recommended against low-radiation dose CT screening in cohorts at low risk of developing lung cancer and in individuals with comorbidities that adversely influence their ability to tolerate the evaluation of screen-detected findings, tolerate treatment of an early stage screen-detected lung cancer, or that substantially limit their life expectancy.

- We also highlighted that screening is reserved for patients without symptoms that could be caused by the presence of lung cancer, stressing that all symptomatic patients should receive an appropriate diagnostic evaluation.

Our remaining recommendation and statements are focused on aspects of screening implementation that influence the balance of benefit and harms of screening and lend to an approach to screening that respects patient values. An extensive literature review, followed by a recommendation or statement, is provided to guide programs in the following areas:

- the choice of nodule size to define what constitutes a positive test;

- maximizing compliance with annual screening exams;

- developing a comprehensive approach to lung nodule management;

- minimizing overtreatment of potentially indolent lung cancers;

- the provision of evidence-based tobacco cessation treatment;

- providing effective counseling and shared decision-making visits prior to the low-radiation dose CT scan;

- how to perform the low-radiation dose CT scan;

- structured reporting of the exam results, management of non-nodule findings on the low radiation dose CT; and

- the development of data collection and reporting tools that are capable of assisting with quality improvement initiatives.

Throughout the recommendations and statements, we have tried to be sensitive to the variety of acceptable approaches to screening program organization, ranging from program structures that are entirely decentralized (test ordering, counseling, and management of the findings by the referring provider) to those that are entirely centralized (test ordering, counseling, and management of the findings by the screening program).

Though we have attempted to comprehensively evaluate the literature and balance available evidence with pragmatism and the needs of our patients, we recognize that well-intentioned and informed experts can have different opinions about aspects of our guidelines. This highlights the need for further research to guide the screening community. Most will agree that it is time to increase access to high- quality lung cancer screening programs across the country. We hope that the updated CHEST lung cancer screening guidelines can help catalyze this.

Coinciding with the publication of the guideline, CHEST has developed new e-learning modules on the benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer. The modules are based on the CHEST 2018 educational session on the Screening for Lung Cancer Guidelines. The modules are available at chestnet.org/lungcancerscreening.

An update to CHEST’s lung cancer screening guideline, Screening for Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report, has just been published online in the journal CHEST®. This update was made possible by the hard work of my co-authors and the amazing support of the CHEST staff.

Our goal was to update the evidence base for the benefit, harms, and implementation of low-radiation dose chest CT screening, then use this evidence base to produce meaningful and usable recommendations. The process for developing the guideline followed the rigorous methodological standards of CHEST in which the evidence was gathered from a systematic literature review, and the overall quality of the body of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach. Recommendations were developed and graded based on this assessment.

There are a few aspects of the new guidelines to highlight. First, we have updated some of the core recommendations; second, we have developed new recommendations related to the implementation of high-quality screening; and third, the CHEST approach to guideline development has evolved to allow us to provide recommendations in which the evidence allows and statements based on experience and expert consensus in which it does not. Through this process, we developed six graded recommendations and nine ungraded consensus-based statements.

In this update, a few changes to the core recommendations about who should be screened are worthy to note:

- We have recommended an increase to the upper age of the screen-eligible cohort from 74 to 77, in line with CMS coverage and reflecting the oldest age of participants in the National Lung Screening Trial at the end of the screening period.

- We have directly addressed the cohort of individuals who are at high risk for having/developing lung cancer based on clinical risk prediction calculators but do not meet the current eligibility criteria. We recommended that this cohort should not be routinely screened given the greater potential for this cohort to have comorbid conditions that would influence morbidity from the evaluation and treatment of screen-detected findings and death from any cause. We did, however, state that there will be individuals within the cohort deemed to be at high risk for lung cancer from a clinical risk prediction calculator who are healthy enough to benefit from lung cancer screening and that low-radiation dose CT screening could be considered in these individuals.

- We recommended against low-radiation dose CT screening in cohorts at low risk of developing lung cancer and in individuals with comorbidities that adversely influence their ability to tolerate the evaluation of screen-detected findings, tolerate treatment of an early stage screen-detected lung cancer, or that substantially limit their life expectancy.

- We also highlighted that screening is reserved for patients without symptoms that could be caused by the presence of lung cancer, stressing that all symptomatic patients should receive an appropriate diagnostic evaluation.

Our remaining recommendation and statements are focused on aspects of screening implementation that influence the balance of benefit and harms of screening and lend to an approach to screening that respects patient values. An extensive literature review, followed by a recommendation or statement, is provided to guide programs in the following areas:

- the choice of nodule size to define what constitutes a positive test;

- maximizing compliance with annual screening exams;

- developing a comprehensive approach to lung nodule management;

- minimizing overtreatment of potentially indolent lung cancers;

- the provision of evidence-based tobacco cessation treatment;

- providing effective counseling and shared decision-making visits prior to the low-radiation dose CT scan;

- how to perform the low-radiation dose CT scan;

- structured reporting of the exam results, management of non-nodule findings on the low radiation dose CT; and

- the development of data collection and reporting tools that are capable of assisting with quality improvement initiatives.

Throughout the recommendations and statements, we have tried to be sensitive to the variety of acceptable approaches to screening program organization, ranging from program structures that are entirely decentralized (test ordering, counseling, and management of the findings by the referring provider) to those that are entirely centralized (test ordering, counseling, and management of the findings by the screening program).

Though we have attempted to comprehensively evaluate the literature and balance available evidence with pragmatism and the needs of our patients, we recognize that well-intentioned and informed experts can have different opinions about aspects of our guidelines. This highlights the need for further research to guide the screening community. Most will agree that it is time to increase access to high- quality lung cancer screening programs across the country. We hope that the updated CHEST lung cancer screening guidelines can help catalyze this.

Coinciding with the publication of the guideline, CHEST has developed new e-learning modules on the benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer. The modules are based on the CHEST 2018 educational session on the Screening for Lung Cancer Guidelines. The modules are available at chestnet.org/lungcancerscreening.

An update to CHEST’s lung cancer screening guideline, Screening for Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report, has just been published online in the journal CHEST®. This update was made possible by the hard work of my co-authors and the amazing support of the CHEST staff.

Our goal was to update the evidence base for the benefit, harms, and implementation of low-radiation dose chest CT screening, then use this evidence base to produce meaningful and usable recommendations. The process for developing the guideline followed the rigorous methodological standards of CHEST in which the evidence was gathered from a systematic literature review, and the overall quality of the body of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach. Recommendations were developed and graded based on this assessment.

There are a few aspects of the new guidelines to highlight. First, we have updated some of the core recommendations; second, we have developed new recommendations related to the implementation of high-quality screening; and third, the CHEST approach to guideline development has evolved to allow us to provide recommendations in which the evidence allows and statements based on experience and expert consensus in which it does not. Through this process, we developed six graded recommendations and nine ungraded consensus-based statements.

In this update, a few changes to the core recommendations about who should be screened are worthy to note:

- We have recommended an increase to the upper age of the screen-eligible cohort from 74 to 77, in line with CMS coverage and reflecting the oldest age of participants in the National Lung Screening Trial at the end of the screening period.

- We have directly addressed the cohort of individuals who are at high risk for having/developing lung cancer based on clinical risk prediction calculators but do not meet the current eligibility criteria. We recommended that this cohort should not be routinely screened given the greater potential for this cohort to have comorbid conditions that would influence morbidity from the evaluation and treatment of screen-detected findings and death from any cause. We did, however, state that there will be individuals within the cohort deemed to be at high risk for lung cancer from a clinical risk prediction calculator who are healthy enough to benefit from lung cancer screening and that low-radiation dose CT screening could be considered in these individuals.

- We recommended against low-radiation dose CT screening in cohorts at low risk of developing lung cancer and in individuals with comorbidities that adversely influence their ability to tolerate the evaluation of screen-detected findings, tolerate treatment of an early stage screen-detected lung cancer, or that substantially limit their life expectancy.

- We also highlighted that screening is reserved for patients without symptoms that could be caused by the presence of lung cancer, stressing that all symptomatic patients should receive an appropriate diagnostic evaluation.

Our remaining recommendation and statements are focused on aspects of screening implementation that influence the balance of benefit and harms of screening and lend to an approach to screening that respects patient values. An extensive literature review, followed by a recommendation or statement, is provided to guide programs in the following areas:

- the choice of nodule size to define what constitutes a positive test;

- maximizing compliance with annual screening exams;

- developing a comprehensive approach to lung nodule management;

- minimizing overtreatment of potentially indolent lung cancers;

- the provision of evidence-based tobacco cessation treatment;

- providing effective counseling and shared decision-making visits prior to the low-radiation dose CT scan;

- how to perform the low-radiation dose CT scan;

- structured reporting of the exam results, management of non-nodule findings on the low radiation dose CT; and

- the development of data collection and reporting tools that are capable of assisting with quality improvement initiatives.

Throughout the recommendations and statements, we have tried to be sensitive to the variety of acceptable approaches to screening program organization, ranging from program structures that are entirely decentralized (test ordering, counseling, and management of the findings by the referring provider) to those that are entirely centralized (test ordering, counseling, and management of the findings by the screening program).

Though we have attempted to comprehensively evaluate the literature and balance available evidence with pragmatism and the needs of our patients, we recognize that well-intentioned and informed experts can have different opinions about aspects of our guidelines. This highlights the need for further research to guide the screening community. Most will agree that it is time to increase access to high- quality lung cancer screening programs across the country. We hope that the updated CHEST lung cancer screening guidelines can help catalyze this.

Coinciding with the publication of the guideline, CHEST has developed new e-learning modules on the benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer. The modules are based on the CHEST 2018 educational session on the Screening for Lung Cancer Guidelines. The modules are available at chestnet.org/lungcancerscreening.

EAGLES: Smoking cessation therapy did not up cardiovascular risk

among stable adult smokers with up to one year of follow-up.

“In what we believe to be the largest smoking cessation clinical trial and the only trial comparing NRT, bupropion, and varenicline [with] placebo, we found no signal that smoking cessation pharmacotherapy increases the risk of serious cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular adverse events in a general population of smokers,” concluded Neal L. Benowitz, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and his associates. “While the number of events was small, the incidence of serious cardiovascular events was low, suggesting that any absolute increase in risk that we might have missed would be low and not clinically meaningful.” The findings were reported online April 9 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

In this double-blind, multicenter, triple-dummy trial (EAGLES), Dr. Benowitz and his associates randomly assigned 8,058 adult smokers, who did not have acute or unstable cardiovascular disease, to receive bupropion (150 mg twice daily), varenicline (1 mg twice daily), NRT (21-mg/day patch with tapering), or placebo for 12 weeks, followed by 12 weeks of follow-up. A total of 4,595 patients agreed to be followed for another 28 weeks during an extension phase of the trial. More than half of the patients were women and the average age of a participant was 47 years. The primary endpoint was time to major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), including cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke. The researchers selected time to MACE as their primary endpoint to better detect differences among groups. One of the secondary end points was the occurrence of MACEs over the same 3 time intervals. Additionally, cardiovascular deaths, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke (the components of MACE) were evaluated individually, as were hospitalizations for congestive heart failure and serious arrhythmias.

Differences in time to onset of MACE between all four patient groups, were not significant. The overall incidence of MACEs was less than 0.5% during all observation periods. There were also no significant differences in rates of the individual types of MACE, coronary revascularization, hospitalization for unstable angina, or new or worsening peripheral vascular disease requiring treatment among groups. Changes in body weight, blood pressure, and heart rate also were similar across patients.

There were five cardiovascular deaths, including one in the varenicline group, two in the bupropion group and two in the placebo group, according to the researchers. Overall the trial results “are consistent with and support previously published findings from meta-analyses and small clinical trials in smokers with known [cardiovascular disease],” they wrote.

GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer, who make and market smoking cessation therapies, sponsored the study. Dr. Benowitz disclosed a consulting relationship with Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies. He also has been a paid expert witness in litigation against tobacco companies. Eight coinvestigators disclosed ties to Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

SOURCE: Benowitz NL et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0397)

among stable adult smokers with up to one year of follow-up.

“In what we believe to be the largest smoking cessation clinical trial and the only trial comparing NRT, bupropion, and varenicline [with] placebo, we found no signal that smoking cessation pharmacotherapy increases the risk of serious cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular adverse events in a general population of smokers,” concluded Neal L. Benowitz, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and his associates. “While the number of events was small, the incidence of serious cardiovascular events was low, suggesting that any absolute increase in risk that we might have missed would be low and not clinically meaningful.” The findings were reported online April 9 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

In this double-blind, multicenter, triple-dummy trial (EAGLES), Dr. Benowitz and his associates randomly assigned 8,058 adult smokers, who did not have acute or unstable cardiovascular disease, to receive bupropion (150 mg twice daily), varenicline (1 mg twice daily), NRT (21-mg/day patch with tapering), or placebo for 12 weeks, followed by 12 weeks of follow-up. A total of 4,595 patients agreed to be followed for another 28 weeks during an extension phase of the trial. More than half of the patients were women and the average age of a participant was 47 years. The primary endpoint was time to major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), including cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke. The researchers selected time to MACE as their primary endpoint to better detect differences among groups. One of the secondary end points was the occurrence of MACEs over the same 3 time intervals. Additionally, cardiovascular deaths, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke (the components of MACE) were evaluated individually, as were hospitalizations for congestive heart failure and serious arrhythmias.

Differences in time to onset of MACE between all four patient groups, were not significant. The overall incidence of MACEs was less than 0.5% during all observation periods. There were also no significant differences in rates of the individual types of MACE, coronary revascularization, hospitalization for unstable angina, or new or worsening peripheral vascular disease requiring treatment among groups. Changes in body weight, blood pressure, and heart rate also were similar across patients.

There were five cardiovascular deaths, including one in the varenicline group, two in the bupropion group and two in the placebo group, according to the researchers. Overall the trial results “are consistent with and support previously published findings from meta-analyses and small clinical trials in smokers with known [cardiovascular disease],” they wrote.

GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer, who make and market smoking cessation therapies, sponsored the study. Dr. Benowitz disclosed a consulting relationship with Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies. He also has been a paid expert witness in litigation against tobacco companies. Eight coinvestigators disclosed ties to Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

SOURCE: Benowitz NL et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0397)

among stable adult smokers with up to one year of follow-up.

“In what we believe to be the largest smoking cessation clinical trial and the only trial comparing NRT, bupropion, and varenicline [with] placebo, we found no signal that smoking cessation pharmacotherapy increases the risk of serious cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular adverse events in a general population of smokers,” concluded Neal L. Benowitz, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and his associates. “While the number of events was small, the incidence of serious cardiovascular events was low, suggesting that any absolute increase in risk that we might have missed would be low and not clinically meaningful.” The findings were reported online April 9 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

In this double-blind, multicenter, triple-dummy trial (EAGLES), Dr. Benowitz and his associates randomly assigned 8,058 adult smokers, who did not have acute or unstable cardiovascular disease, to receive bupropion (150 mg twice daily), varenicline (1 mg twice daily), NRT (21-mg/day patch with tapering), or placebo for 12 weeks, followed by 12 weeks of follow-up. A total of 4,595 patients agreed to be followed for another 28 weeks during an extension phase of the trial. More than half of the patients were women and the average age of a participant was 47 years. The primary endpoint was time to major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), including cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke. The researchers selected time to MACE as their primary endpoint to better detect differences among groups. One of the secondary end points was the occurrence of MACEs over the same 3 time intervals. Additionally, cardiovascular deaths, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke (the components of MACE) were evaluated individually, as were hospitalizations for congestive heart failure and serious arrhythmias.

Differences in time to onset of MACE between all four patient groups, were not significant. The overall incidence of MACEs was less than 0.5% during all observation periods. There were also no significant differences in rates of the individual types of MACE, coronary revascularization, hospitalization for unstable angina, or new or worsening peripheral vascular disease requiring treatment among groups. Changes in body weight, blood pressure, and heart rate also were similar across patients.

There were five cardiovascular deaths, including one in the varenicline group, two in the bupropion group and two in the placebo group, according to the researchers. Overall the trial results “are consistent with and support previously published findings from meta-analyses and small clinical trials in smokers with known [cardiovascular disease],” they wrote.

GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer, who make and market smoking cessation therapies, sponsored the study. Dr. Benowitz disclosed a consulting relationship with Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies. He also has been a paid expert witness in litigation against tobacco companies. Eight coinvestigators disclosed ties to Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

SOURCE: Benowitz NL et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0397)

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The use of smoking cessation therapy did not increase the risk of cardiovascular events in adult smokers.

Major finding: There were no significant differences among groups in rates of major adverse cardiovascular events, rates of other pertinent cardiovascular events, time to cardiovascular events, blood pressure, or heart rate.

Study details: Double-blind, randomized, multicenter, triple-dummy trial of 8,058 adult smokers receiving nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, varenicline, or placebo (EAGLES).

Disclosures: GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer sponsored the study and make the drugs. Dr. Benowitz disclosed a consulting relationship with Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies. He also has been a paid expert witness in litigation against tobacco companies. Eight coinvestigators disclosed ties to Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and other companies.

Source: Benowitz NL et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0397.

Analgesic management in radiation oncology for painful bone metastases

Bone metastases are a common cause of pain in patients with advanced cancer, with about three-quarters of patients with bone metastases experiencing pain as the dominant symptom.1 Inadequately treated cancer pain impairs patient quality of life, and is associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and fatigue. Palliative radiotherapy (RT) is effective in alleviating pain from bone metastases.4 Local field external beam radiotherapy can provide some pain relief at the site of treated metastasis in 80%-90% of cases, with complete pain relief in 50%-60% of cases.5,6 However, maximal pain relief from RT is delayed, in some cases taking days to up to multiple weeks to attain.7,8 Therefore, optimal management of bone metastases pain may require the use of analgesics until RT takes adequate effect.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for Adult Cancer Pain (v. 2.2015) recommend that pain intensity rating (PIR; range, 0-10, where 0 denotes no pain and 10, worst pain imaginable) be used to quantify pain for all symptomatic patients. These guidelines also recommend the pain medication regimen be assessed for all symptomatic patients. For patients with moderate or severe pain (PIR of ≥4), NCCN guidelines recommend that analgesic regimen be intervened upon by alteration of the analgesic regimen (initiating, rotating, or titrating analgesic) or consideration of referral to pain/symptom management specialty.

Previous findings have demonstrated inadequate analgesic management for cancer pain,2,9 including within the radiation oncology (RO) clinic, suggesting that patients seen in consultation for palliative RT may experience uncontrolled pain for days to weeks before the onset of relief from RT. Possible reasons for inadequate acute pain intervention in the RO clinic may be provider discomfort with analgesic management and infrequent formal integration of palliative care within RO.10

Limited single-institution data from the few institutions with dedicated palliative RO services have suggested that these services improve the quality of palliative care delivery, as demonstrated by providers perceptions’ of the clinical impact of a dedicated service11 and the implementation of expedited palliative RT delivery for acute cancer pain.12,13 To our knowledge, the impact of a dedicated palliative RO service on analgesic management for cancer pain has not been assessed.

Here, we report how often patients with symptomatic bone metastases had assessments of existing analgesic regimens and interventions at RO consultation at 2 cancer centers. Center 1 had implemented a dedicated palliative RO service in 2011, consisting of rotating attending physicians and residents as well as dedicated palliative care trained nurse practitioners and a fellow, with the service structured around daily rounds,11 whereas Center 2 had not yet implemented a dedicated service. Using data from both centers, we assessed the impact of a palliative RO service on analgesic assessment and management in patients with bone metastases.

Methods

We searched our institutional databases for patients seen in RO consultation for bone metastases using ICD-9 code 198.5, and retrospectively reviewed consultation notes for those patients during June-July 2008, January-February 2010, January-February 2013, and June-July 2014. Those time periods were chosen as evenly spaced representative samples before and after implementation of a dedicated palliative RO service in 2011 at Center 1. Center 2 did not implement a dedicated palliative RO service in these time periods.

Within consultation notes, we recorded the following data from the History of the Present Illness section: symptoms from bone metastases (symptomatic was defined as any pain present); PIR (range, 0-10); and whether or not the preconsultation analgesic regimen was reported for symptomatic patients (including analgesic type, dosing, effectiveness, and adherence).

Documentation of the analgesic regimen in the history section of the notes was considered the proxy for analgesic regimen assessment at time of RO consultation. Analgesics within the Medications list, which were autopopulated in the consultation note by the electronic medical record, were recorded.

Whether or not pain was addressed with initiation or titration of analgesics for patients with a PIR of ≥4 was recorded from the Assessment and Plan portion of the notes, and that metric was considered the proxy for pain intervention. In addition, the case was coded as having had pain intervention if there was documentation of the patient declining recommended analgesic intervention, or the patient had been referred to a symptom management service for intervention (eg, referral to a specialty palliative care clinic), or there was recommendation for the patient to discuss uncontrolled pain with the original prescriber. A PIR of 4 was chosen as the threshold for analgesic intervention because at that level, NCCN guidelines for cancer pain state that the analgesic regimen should be titrated, whereas for a PIR of 3 or less, the guidelines recommend only consideration of titrating the analgesic. Only patients with a documented PIR were included in the pain intervention analysis.

Frequencies of analgesic assessment and analgesic intervention were compared using t tests (Wizard Pro, v1.8.5; Evan Miller, Chicago IL).

Results

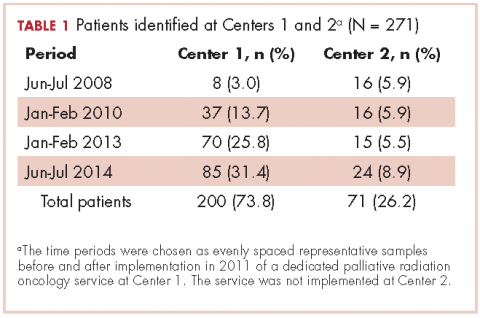

A total of 271 patients with RO consultation notes were identified at the 2 centers within the 4 time periods (Table 1).

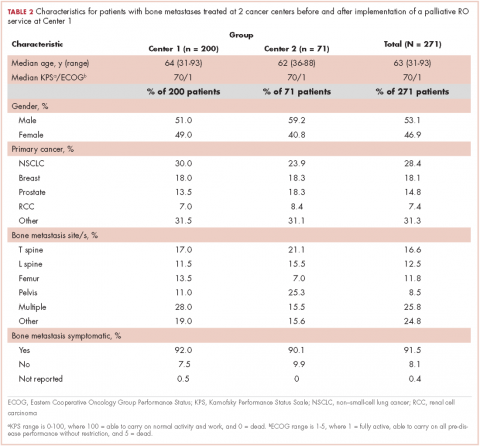

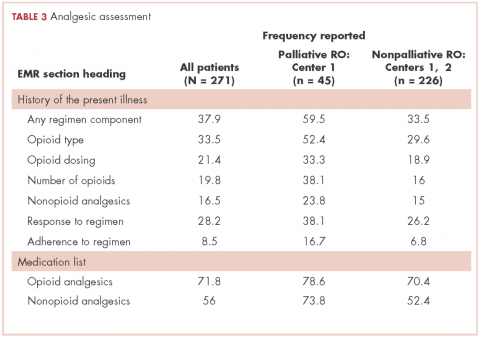

Among symptomatic patients, any component of the preconsultation analgesic regimen (including analgesic type, dosing, pain response, and adherence) was documented for 37.9% of the entire cohort at RO consultation (Table 3). At Centers 1 and 2, the frequencies of analgesic regimen assessment were documented for 41.3% and 28.1%, respectively (P = .06). Among symptomatic patients, 81.5% had an opioid or nonopioid analgesic listed in the Medications section in the electronic medical record at time of consultation.

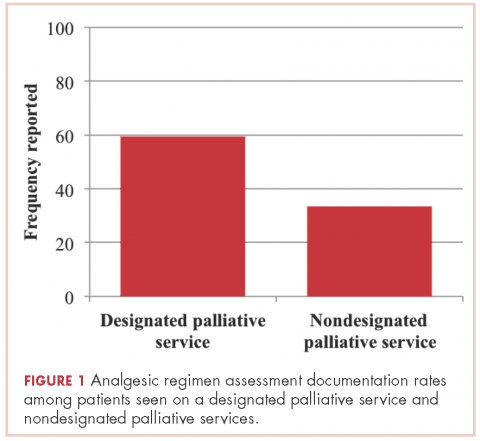

Patients seen on the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1 had an analgesic assessment documentation rate of 59.5%, whereas the patients not seen on a palliative RO service (ie, patients seen on a nonpalliative RO service at Center 1 plus all patients at Center 2) had an assessment documentation rate of 33.5% (P = .002; Figure 1). There was no significant difference between rates of analgesic regimen assessment between patients seen at Center 2 and patients seen within nondedicated palliative RO services at Center 1 (28.1% vs 35.9%, respectively; P = .27).

In patients seen at Center 1 only, those seen on the palliative RO service had a higher documentation rate of analgesic assessment compared with those seen by other services after implementation of the dedicated service (59.5% vs 38%, respectively; P = .018). Time period (after versus before 2011) was not significantly associated with the rate of documentation of analgesic assessment at either Center 1 (after vs before 2011: 44.4% vs 31%, P = .23) or Center 2 (31.4% vs 24.1%, P = .60).

Among patients with a PIR of ≥4, analgesic intervention was reported for 17.2% of patients within the entire cohort (20.8% at Center 1 and 0% at Center 2, P = .05). Among those with a PIR of ≥4, documentation of analgesic assessment noted in the History of the Present Illness section was associated with increased documentation of an analgesic intervention in the Assessment and Plan section (25% vs 7.3%; odds ratio [OR], 4.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-16.0; P = .03).

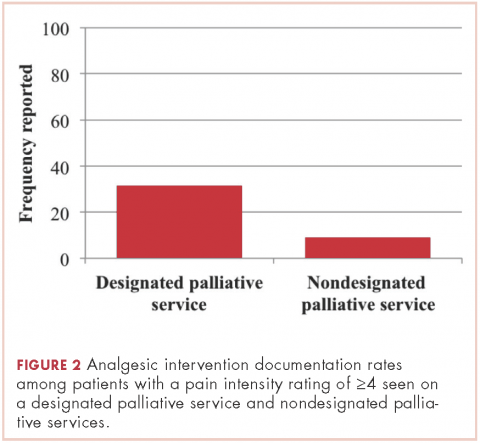

Patients seen on the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1 had a documented analgesic intervention rate of 31.6%, whereas the patients not seen on a palliative RO service (ie, those seen on a nonpalliative RO service at Center 1 plus all patients at Center 2) had a documented analgesic intervention rate of 9.2% (P = .01; Figure 2). There was no statistically significant difference between rates of documentation of an analgesic regimen intervention between patients seen at Center 2 and patients seen within nondedicated palliative RO services at Center 1 (0% vs 17.2%, respectively; P = .07).

Looking at only patients seen at Center 1, patients with a PIR of ≥4 seen on the dedicated palliative RO service had a nearly significant higher rate of documented analgesic interventions in the time period after implementation of the dedicate service (31.6% if seen on the dedicated service vs 12% if seen on a nondedicated service, P = .06).

Discussion

Multiple studies demonstrate the undertreatment of cancer pain in the outpatient setting.2,9,14,15 At 2 cancer centers, we found that about half of patients who present for consideration of palliative RT for bone metastases had a PIR of ≥4, yet only 17% of them had documentation of analgesic intervention as recommended by NCCN guidelines for cancer pain. Underlying this low rate of appropriate intervention may be the assumption of rapid pain relief by RT. However, RT often does not begin at time of consultation,16 and maximal pain relief may take days to weeks after commencement of RT.17 It is estimated that a quarter of all patients with cancer develop bone metastases during the course of their disease,12 and most of those patients suffer from pain. Thus, inherent delay in pain relief before, during, and after RT results in significant morbidity for the cancer patient population if adequate analgesic management is not provided.

The low rate of appropriate analgesic intervention at the time of RO consultation may also be related to the low incidence of proper analgesic assessment. In our cohort, 80% of symptomatic patients had an opioid or nonopioid analgesic listed in their medications within the electronic medical record at time of consultation, but only 38% had the analgesic regimen and/or its effectiveness described in the History of the Present Illness section of the record. Inattentiveness to analgesic type, dosing, and effectiveness during consultation may result in any inadequacies of the analgesic regimen going unnoticed. Consistent with this notion, we found that the rate of appropriate intervention for patients with a PIR of ≥4 was higher among patients who had analgesic regimen reported in the consultation note. Thus, interventions to implement routine review and documentation of the analgesic regimen, for example within the electronic medical record, may be one way to improve pain management.

Another possible reason for low rates of acute pain management within the RO clinic is low provider confidence in regard to analgesic management. In a recent national survey, 96% of radiation oncologists stated they were at least moderately confident with assessment of pain, yet only 77% were at least moderately confident with titrating opioids, and just 56% were at least moderately confident with rotating opioids.10 Educational interventions that improve providers’ facility with analgesic management may increase the frequency of pain management in the RO clinic.

Patients seen on the dedicated palliative RO service had significantly higher rates of documented analgesic regimen assessment and appropriate intervention during RO consultation, compared with patients seen at Center 2 and those not seen on the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1. The improvements we observed in analgesic assessment and intervention at Center 1 for patients seen on the palliative RO service are likely owing to involvement of palliative RO and not to secular trends, because there were not similar improvements for patients at Center 1 who were not seen by the palliative RO service and those at Center 2, where there was no service.

At Center 1, the dedicated palliative RO service was created to provide specialized care to patients with metastatic disease undergoing palliative radiation. Within its structure, topics within palliative RO, such as technical aspects of palliative RT, symptom management, and communication are taught and reinforced in a case-based approach. Such palliative care awareness, integration, and education within RO achieved by the palliative RO service likely contribute to the improved rates of analgesic management we found in our study. We do note that rate of analgesic intervention in the palliative RO cohort, though higher than in the nonpalliative RO group, was still low, with only a third of patients receiving proper analgesic management. These findings highlight the importance of continued effort in increasing providers’ awareness of the need to assess pain and raise comfort with analgesic initiation and titration and of having dedicated palliative care clinicians embedded within the RO setting.

Since the data for this study was acquired, Center 2 has implemented a short palliative RO didactic course for residents, which improved their comfort levels in assessing analgesic effectiveness and intervening for uncontrolled pain.18 The impact of this intervention on clinical care will need to be evaluated, but the improved provider comfort levels may translate into better-quality care.

Limitations

An important limitation of this retrospective study is the reliance on the documentation provided in the consultation note for determining frequencies of analgesic regimen assessment and intervention. The actual rates of analgesic management that occurred in clinic may have been higher than reported in the documentation. However, such discrepancy in documentation of analgesic management would also be an area for quality improvement. Inadequate documentation limits the ability for proper follow-up of cancer pain as recommended by a joint guidance statement from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.19,20 The results of our study may also partly reflect a positive impact in documentation of analgesic management by a dedicated palliative RO service.

Given the multi-institutional nature of this study, it may be that general practice differences confound the impact of the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1. However, with excluding Center 2, the dedicated service was still strongly associated with a higher rate of analgesic assessment within Center 1 and was almost significantly associated with appropriate analgesic intervention within Center 1.

We used a PIR of ≥4 as a threshold for appropriate analgesic regimen intervention because it is what is recommended by the NCCN guidelines. However, close attention should be paid to the impact that any amount of pain has on an individual patient. The functional, spiritual, and existential impact of pain is unique to each patient’s experience, and optimal symptom management should take those elements into account.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study indicates that advanced cancer patient pain assessment and intervention according to NCCN cancer pain management guidelines is not common in the RO setting, and it is an area that should be targeted for quality improvement because of the positive implications for patient well-being. Pain assessment and intervention were greater in the setting of a dedicated structure for palliative care within RO, suggesting that the integration of palliative care within RO is a promising means of improving quality of pain management.

This work was presented at the 2016 ASCO Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium (September 9-10, 2016), where this work received a Conquer Cancer Foundation Merit Award.

1. Amichetti M, Orrù P, Madeddu A, et al. Comparative evaluation of two hypofractionated radiotherapy regimens for painful bone metastases. Tumori. 2004;90(1):91-95.

2. Vuong S, Pulenzas N, DeAngelis C, et al. Inadequate pain management in cancer patients attending an outpatient palliative radiotherapy clinic. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(2):887-892.

3. Portenoy RK, Payne D, Jacobsen P. Breakthrough pain: characteristics and impact in patients with cancer pain. Pain. 1999;81(1-2):129-134.

4. Sze WM, Shelley M, Held I, Mason M. Palliation of metastatic bone pain: single fraction versus multifraction radiotherapy - a systematic review of the randomised trials. Sze WM, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2):CD004721-CD004721.

5. Ratanatharathorn V, Powers WE, Moss WT, Perez CA. Bone metastasis: review and critical analysis of random allocation trials of local field treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(1):1-18.

6. Kirou-Mauro A, Hird A, Wong J, et al. Is response to radiotherapy in patients related to the severity of pretreatment pain? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(4):1208-1212.

7. Frassica DA. General principles of external beam radiation therapy for skeletal metastases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(415 Suppl):S158-S164.

8. McDonald R, Ding K, Brundage M, et al. Effect of radiotherapy on painful bone metastases: a secondary analysis of the NCIC Clinical Trials Group Symptom Control Trial SC.23. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Jul 1;3(7):953-959.

9. Greco MT, Roberto A, Corli O, et al. Quality of cancer pain management: an update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4149-4154.

10. Wei RL, Mattes MD, Yu J, et al. Attitudes of radiation oncologists toward palliative and supportive care in the united states: report on national membership survey by the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO). Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7(2):113-119.

11. Tseng YD, Krishnan MS, Jones JA, et al. Supportive and palliative radiation oncology service: impact of a dedicated service on palliative cancer care. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2014;4(4):247-253.

12. Fairchild A, Pituskin E, Rose B, et al. The rapid access palliative radiotherapy program: blueprint for initiation of a one-stop multidisciplinary bone metastases clinic. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(2):163-170.

13. de Sa E, Sinclair E, Mitera G, et al. Continued success of the rapid response radiotherapy program: a review of 2004-2008. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(7):757-762.

14. Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(12):1985-1991.

15. Mitera G, Zeiadin N, Kirou-Mauro A, et al. Retrospective assessment of cancer pain management in an outpatient palliative radiotherapy clinic using the Pain Management Index. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(2):259-267.

16. Danjoux C, Chow E, Drossos A, et al. An innovative rapid response radiotherapy program to reduce waiting time for palliative radiotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(1):38-43.

17. Feyer PC, Steingraeber M. Radiotherapy of bone metastasis in breast cancer patients – current approaches. Breast Care (Basel). 2012;7(2):108-112.

18. Garcia MA, Braunstein SE, Anderson WG. Palliative Care Didactic Course for Radiation Oncology Residents. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97(5):884-885.

19. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96-112.

20. Bickel KE, McNiff K, Buss MK, et al. Defining high-quality palliative care in oncology practice: an American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine guidance statement. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(9):e828-e838.

Bone metastases are a common cause of pain in patients with advanced cancer, with about three-quarters of patients with bone metastases experiencing pain as the dominant symptom.1 Inadequately treated cancer pain impairs patient quality of life, and is associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and fatigue. Palliative radiotherapy (RT) is effective in alleviating pain from bone metastases.4 Local field external beam radiotherapy can provide some pain relief at the site of treated metastasis in 80%-90% of cases, with complete pain relief in 50%-60% of cases.5,6 However, maximal pain relief from RT is delayed, in some cases taking days to up to multiple weeks to attain.7,8 Therefore, optimal management of bone metastases pain may require the use of analgesics until RT takes adequate effect.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for Adult Cancer Pain (v. 2.2015) recommend that pain intensity rating (PIR; range, 0-10, where 0 denotes no pain and 10, worst pain imaginable) be used to quantify pain for all symptomatic patients. These guidelines also recommend the pain medication regimen be assessed for all symptomatic patients. For patients with moderate or severe pain (PIR of ≥4), NCCN guidelines recommend that analgesic regimen be intervened upon by alteration of the analgesic regimen (initiating, rotating, or titrating analgesic) or consideration of referral to pain/symptom management specialty.

Previous findings have demonstrated inadequate analgesic management for cancer pain,2,9 including within the radiation oncology (RO) clinic, suggesting that patients seen in consultation for palliative RT may experience uncontrolled pain for days to weeks before the onset of relief from RT. Possible reasons for inadequate acute pain intervention in the RO clinic may be provider discomfort with analgesic management and infrequent formal integration of palliative care within RO.10

Limited single-institution data from the few institutions with dedicated palliative RO services have suggested that these services improve the quality of palliative care delivery, as demonstrated by providers perceptions’ of the clinical impact of a dedicated service11 and the implementation of expedited palliative RT delivery for acute cancer pain.12,13 To our knowledge, the impact of a dedicated palliative RO service on analgesic management for cancer pain has not been assessed.

Here, we report how often patients with symptomatic bone metastases had assessments of existing analgesic regimens and interventions at RO consultation at 2 cancer centers. Center 1 had implemented a dedicated palliative RO service in 2011, consisting of rotating attending physicians and residents as well as dedicated palliative care trained nurse practitioners and a fellow, with the service structured around daily rounds,11 whereas Center 2 had not yet implemented a dedicated service. Using data from both centers, we assessed the impact of a palliative RO service on analgesic assessment and management in patients with bone metastases.

Methods

We searched our institutional databases for patients seen in RO consultation for bone metastases using ICD-9 code 198.5, and retrospectively reviewed consultation notes for those patients during June-July 2008, January-February 2010, January-February 2013, and June-July 2014. Those time periods were chosen as evenly spaced representative samples before and after implementation of a dedicated palliative RO service in 2011 at Center 1. Center 2 did not implement a dedicated palliative RO service in these time periods.

Within consultation notes, we recorded the following data from the History of the Present Illness section: symptoms from bone metastases (symptomatic was defined as any pain present); PIR (range, 0-10); and whether or not the preconsultation analgesic regimen was reported for symptomatic patients (including analgesic type, dosing, effectiveness, and adherence).

Documentation of the analgesic regimen in the history section of the notes was considered the proxy for analgesic regimen assessment at time of RO consultation. Analgesics within the Medications list, which were autopopulated in the consultation note by the electronic medical record, were recorded.

Whether or not pain was addressed with initiation or titration of analgesics for patients with a PIR of ≥4 was recorded from the Assessment and Plan portion of the notes, and that metric was considered the proxy for pain intervention. In addition, the case was coded as having had pain intervention if there was documentation of the patient declining recommended analgesic intervention, or the patient had been referred to a symptom management service for intervention (eg, referral to a specialty palliative care clinic), or there was recommendation for the patient to discuss uncontrolled pain with the original prescriber. A PIR of 4 was chosen as the threshold for analgesic intervention because at that level, NCCN guidelines for cancer pain state that the analgesic regimen should be titrated, whereas for a PIR of 3 or less, the guidelines recommend only consideration of titrating the analgesic. Only patients with a documented PIR were included in the pain intervention analysis.

Frequencies of analgesic assessment and analgesic intervention were compared using t tests (Wizard Pro, v1.8.5; Evan Miller, Chicago IL).

Results

A total of 271 patients with RO consultation notes were identified at the 2 centers within the 4 time periods (Table 1).

Among symptomatic patients, any component of the preconsultation analgesic regimen (including analgesic type, dosing, pain response, and adherence) was documented for 37.9% of the entire cohort at RO consultation (Table 3). At Centers 1 and 2, the frequencies of analgesic regimen assessment were documented for 41.3% and 28.1%, respectively (P = .06). Among symptomatic patients, 81.5% had an opioid or nonopioid analgesic listed in the Medications section in the electronic medical record at time of consultation.

Patients seen on the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1 had an analgesic assessment documentation rate of 59.5%, whereas the patients not seen on a palliative RO service (ie, patients seen on a nonpalliative RO service at Center 1 plus all patients at Center 2) had an assessment documentation rate of 33.5% (P = .002; Figure 1). There was no significant difference between rates of analgesic regimen assessment between patients seen at Center 2 and patients seen within nondedicated palliative RO services at Center 1 (28.1% vs 35.9%, respectively; P = .27).

In patients seen at Center 1 only, those seen on the palliative RO service had a higher documentation rate of analgesic assessment compared with those seen by other services after implementation of the dedicated service (59.5% vs 38%, respectively; P = .018). Time period (after versus before 2011) was not significantly associated with the rate of documentation of analgesic assessment at either Center 1 (after vs before 2011: 44.4% vs 31%, P = .23) or Center 2 (31.4% vs 24.1%, P = .60).

Among patients with a PIR of ≥4, analgesic intervention was reported for 17.2% of patients within the entire cohort (20.8% at Center 1 and 0% at Center 2, P = .05). Among those with a PIR of ≥4, documentation of analgesic assessment noted in the History of the Present Illness section was associated with increased documentation of an analgesic intervention in the Assessment and Plan section (25% vs 7.3%; odds ratio [OR], 4.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-16.0; P = .03).

Patients seen on the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1 had a documented analgesic intervention rate of 31.6%, whereas the patients not seen on a palliative RO service (ie, those seen on a nonpalliative RO service at Center 1 plus all patients at Center 2) had a documented analgesic intervention rate of 9.2% (P = .01; Figure 2). There was no statistically significant difference between rates of documentation of an analgesic regimen intervention between patients seen at Center 2 and patients seen within nondedicated palliative RO services at Center 1 (0% vs 17.2%, respectively; P = .07).

Looking at only patients seen at Center 1, patients with a PIR of ≥4 seen on the dedicated palliative RO service had a nearly significant higher rate of documented analgesic interventions in the time period after implementation of the dedicate service (31.6% if seen on the dedicated service vs 12% if seen on a nondedicated service, P = .06).

Discussion

Multiple studies demonstrate the undertreatment of cancer pain in the outpatient setting.2,9,14,15 At 2 cancer centers, we found that about half of patients who present for consideration of palliative RT for bone metastases had a PIR of ≥4, yet only 17% of them had documentation of analgesic intervention as recommended by NCCN guidelines for cancer pain. Underlying this low rate of appropriate intervention may be the assumption of rapid pain relief by RT. However, RT often does not begin at time of consultation,16 and maximal pain relief may take days to weeks after commencement of RT.17 It is estimated that a quarter of all patients with cancer develop bone metastases during the course of their disease,12 and most of those patients suffer from pain. Thus, inherent delay in pain relief before, during, and after RT results in significant morbidity for the cancer patient population if adequate analgesic management is not provided.

The low rate of appropriate analgesic intervention at the time of RO consultation may also be related to the low incidence of proper analgesic assessment. In our cohort, 80% of symptomatic patients had an opioid or nonopioid analgesic listed in their medications within the electronic medical record at time of consultation, but only 38% had the analgesic regimen and/or its effectiveness described in the History of the Present Illness section of the record. Inattentiveness to analgesic type, dosing, and effectiveness during consultation may result in any inadequacies of the analgesic regimen going unnoticed. Consistent with this notion, we found that the rate of appropriate intervention for patients with a PIR of ≥4 was higher among patients who had analgesic regimen reported in the consultation note. Thus, interventions to implement routine review and documentation of the analgesic regimen, for example within the electronic medical record, may be one way to improve pain management.

Another possible reason for low rates of acute pain management within the RO clinic is low provider confidence in regard to analgesic management. In a recent national survey, 96% of radiation oncologists stated they were at least moderately confident with assessment of pain, yet only 77% were at least moderately confident with titrating opioids, and just 56% were at least moderately confident with rotating opioids.10 Educational interventions that improve providers’ facility with analgesic management may increase the frequency of pain management in the RO clinic.

Patients seen on the dedicated palliative RO service had significantly higher rates of documented analgesic regimen assessment and appropriate intervention during RO consultation, compared with patients seen at Center 2 and those not seen on the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1. The improvements we observed in analgesic assessment and intervention at Center 1 for patients seen on the palliative RO service are likely owing to involvement of palliative RO and not to secular trends, because there were not similar improvements for patients at Center 1 who were not seen by the palliative RO service and those at Center 2, where there was no service.

At Center 1, the dedicated palliative RO service was created to provide specialized care to patients with metastatic disease undergoing palliative radiation. Within its structure, topics within palliative RO, such as technical aspects of palliative RT, symptom management, and communication are taught and reinforced in a case-based approach. Such palliative care awareness, integration, and education within RO achieved by the palliative RO service likely contribute to the improved rates of analgesic management we found in our study. We do note that rate of analgesic intervention in the palliative RO cohort, though higher than in the nonpalliative RO group, was still low, with only a third of patients receiving proper analgesic management. These findings highlight the importance of continued effort in increasing providers’ awareness of the need to assess pain and raise comfort with analgesic initiation and titration and of having dedicated palliative care clinicians embedded within the RO setting.

Since the data for this study was acquired, Center 2 has implemented a short palliative RO didactic course for residents, which improved their comfort levels in assessing analgesic effectiveness and intervening for uncontrolled pain.18 The impact of this intervention on clinical care will need to be evaluated, but the improved provider comfort levels may translate into better-quality care.

Limitations

An important limitation of this retrospective study is the reliance on the documentation provided in the consultation note for determining frequencies of analgesic regimen assessment and intervention. The actual rates of analgesic management that occurred in clinic may have been higher than reported in the documentation. However, such discrepancy in documentation of analgesic management would also be an area for quality improvement. Inadequate documentation limits the ability for proper follow-up of cancer pain as recommended by a joint guidance statement from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.19,20 The results of our study may also partly reflect a positive impact in documentation of analgesic management by a dedicated palliative RO service.

Given the multi-institutional nature of this study, it may be that general practice differences confound the impact of the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1. However, with excluding Center 2, the dedicated service was still strongly associated with a higher rate of analgesic assessment within Center 1 and was almost significantly associated with appropriate analgesic intervention within Center 1.

We used a PIR of ≥4 as a threshold for appropriate analgesic regimen intervention because it is what is recommended by the NCCN guidelines. However, close attention should be paid to the impact that any amount of pain has on an individual patient. The functional, spiritual, and existential impact of pain is unique to each patient’s experience, and optimal symptom management should take those elements into account.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study indicates that advanced cancer patient pain assessment and intervention according to NCCN cancer pain management guidelines is not common in the RO setting, and it is an area that should be targeted for quality improvement because of the positive implications for patient well-being. Pain assessment and intervention were greater in the setting of a dedicated structure for palliative care within RO, suggesting that the integration of palliative care within RO is a promising means of improving quality of pain management.

This work was presented at the 2016 ASCO Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium (September 9-10, 2016), where this work received a Conquer Cancer Foundation Merit Award.

Bone metastases are a common cause of pain in patients with advanced cancer, with about three-quarters of patients with bone metastases experiencing pain as the dominant symptom.1 Inadequately treated cancer pain impairs patient quality of life, and is associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and fatigue. Palliative radiotherapy (RT) is effective in alleviating pain from bone metastases.4 Local field external beam radiotherapy can provide some pain relief at the site of treated metastasis in 80%-90% of cases, with complete pain relief in 50%-60% of cases.5,6 However, maximal pain relief from RT is delayed, in some cases taking days to up to multiple weeks to attain.7,8 Therefore, optimal management of bone metastases pain may require the use of analgesics until RT takes adequate effect.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for Adult Cancer Pain (v. 2.2015) recommend that pain intensity rating (PIR; range, 0-10, where 0 denotes no pain and 10, worst pain imaginable) be used to quantify pain for all symptomatic patients. These guidelines also recommend the pain medication regimen be assessed for all symptomatic patients. For patients with moderate or severe pain (PIR of ≥4), NCCN guidelines recommend that analgesic regimen be intervened upon by alteration of the analgesic regimen (initiating, rotating, or titrating analgesic) or consideration of referral to pain/symptom management specialty.

Previous findings have demonstrated inadequate analgesic management for cancer pain,2,9 including within the radiation oncology (RO) clinic, suggesting that patients seen in consultation for palliative RT may experience uncontrolled pain for days to weeks before the onset of relief from RT. Possible reasons for inadequate acute pain intervention in the RO clinic may be provider discomfort with analgesic management and infrequent formal integration of palliative care within RO.10

Limited single-institution data from the few institutions with dedicated palliative RO services have suggested that these services improve the quality of palliative care delivery, as demonstrated by providers perceptions’ of the clinical impact of a dedicated service11 and the implementation of expedited palliative RT delivery for acute cancer pain.12,13 To our knowledge, the impact of a dedicated palliative RO service on analgesic management for cancer pain has not been assessed.

Here, we report how often patients with symptomatic bone metastases had assessments of existing analgesic regimens and interventions at RO consultation at 2 cancer centers. Center 1 had implemented a dedicated palliative RO service in 2011, consisting of rotating attending physicians and residents as well as dedicated palliative care trained nurse practitioners and a fellow, with the service structured around daily rounds,11 whereas Center 2 had not yet implemented a dedicated service. Using data from both centers, we assessed the impact of a palliative RO service on analgesic assessment and management in patients with bone metastases.

Methods

We searched our institutional databases for patients seen in RO consultation for bone metastases using ICD-9 code 198.5, and retrospectively reviewed consultation notes for those patients during June-July 2008, January-February 2010, January-February 2013, and June-July 2014. Those time periods were chosen as evenly spaced representative samples before and after implementation of a dedicated palliative RO service in 2011 at Center 1. Center 2 did not implement a dedicated palliative RO service in these time periods.

Within consultation notes, we recorded the following data from the History of the Present Illness section: symptoms from bone metastases (symptomatic was defined as any pain present); PIR (range, 0-10); and whether or not the preconsultation analgesic regimen was reported for symptomatic patients (including analgesic type, dosing, effectiveness, and adherence).

Documentation of the analgesic regimen in the history section of the notes was considered the proxy for analgesic regimen assessment at time of RO consultation. Analgesics within the Medications list, which were autopopulated in the consultation note by the electronic medical record, were recorded.

Whether or not pain was addressed with initiation or titration of analgesics for patients with a PIR of ≥4 was recorded from the Assessment and Plan portion of the notes, and that metric was considered the proxy for pain intervention. In addition, the case was coded as having had pain intervention if there was documentation of the patient declining recommended analgesic intervention, or the patient had been referred to a symptom management service for intervention (eg, referral to a specialty palliative care clinic), or there was recommendation for the patient to discuss uncontrolled pain with the original prescriber. A PIR of 4 was chosen as the threshold for analgesic intervention because at that level, NCCN guidelines for cancer pain state that the analgesic regimen should be titrated, whereas for a PIR of 3 or less, the guidelines recommend only consideration of titrating the analgesic. Only patients with a documented PIR were included in the pain intervention analysis.

Frequencies of analgesic assessment and analgesic intervention were compared using t tests (Wizard Pro, v1.8.5; Evan Miller, Chicago IL).

Results

A total of 271 patients with RO consultation notes were identified at the 2 centers within the 4 time periods (Table 1).

Among symptomatic patients, any component of the preconsultation analgesic regimen (including analgesic type, dosing, pain response, and adherence) was documented for 37.9% of the entire cohort at RO consultation (Table 3). At Centers 1 and 2, the frequencies of analgesic regimen assessment were documented for 41.3% and 28.1%, respectively (P = .06). Among symptomatic patients, 81.5% had an opioid or nonopioid analgesic listed in the Medications section in the electronic medical record at time of consultation.

Patients seen on the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1 had an analgesic assessment documentation rate of 59.5%, whereas the patients not seen on a palliative RO service (ie, patients seen on a nonpalliative RO service at Center 1 plus all patients at Center 2) had an assessment documentation rate of 33.5% (P = .002; Figure 1). There was no significant difference between rates of analgesic regimen assessment between patients seen at Center 2 and patients seen within nondedicated palliative RO services at Center 1 (28.1% vs 35.9%, respectively; P = .27).

In patients seen at Center 1 only, those seen on the palliative RO service had a higher documentation rate of analgesic assessment compared with those seen by other services after implementation of the dedicated service (59.5% vs 38%, respectively; P = .018). Time period (after versus before 2011) was not significantly associated with the rate of documentation of analgesic assessment at either Center 1 (after vs before 2011: 44.4% vs 31%, P = .23) or Center 2 (31.4% vs 24.1%, P = .60).

Among patients with a PIR of ≥4, analgesic intervention was reported for 17.2% of patients within the entire cohort (20.8% at Center 1 and 0% at Center 2, P = .05). Among those with a PIR of ≥4, documentation of analgesic assessment noted in the History of the Present Illness section was associated with increased documentation of an analgesic intervention in the Assessment and Plan section (25% vs 7.3%; odds ratio [OR], 4.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-16.0; P = .03).

Patients seen on the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1 had a documented analgesic intervention rate of 31.6%, whereas the patients not seen on a palliative RO service (ie, those seen on a nonpalliative RO service at Center 1 plus all patients at Center 2) had a documented analgesic intervention rate of 9.2% (P = .01; Figure 2). There was no statistically significant difference between rates of documentation of an analgesic regimen intervention between patients seen at Center 2 and patients seen within nondedicated palliative RO services at Center 1 (0% vs 17.2%, respectively; P = .07).

Looking at only patients seen at Center 1, patients with a PIR of ≥4 seen on the dedicated palliative RO service had a nearly significant higher rate of documented analgesic interventions in the time period after implementation of the dedicate service (31.6% if seen on the dedicated service vs 12% if seen on a nondedicated service, P = .06).

Discussion

Multiple studies demonstrate the undertreatment of cancer pain in the outpatient setting.2,9,14,15 At 2 cancer centers, we found that about half of patients who present for consideration of palliative RT for bone metastases had a PIR of ≥4, yet only 17% of them had documentation of analgesic intervention as recommended by NCCN guidelines for cancer pain. Underlying this low rate of appropriate intervention may be the assumption of rapid pain relief by RT. However, RT often does not begin at time of consultation,16 and maximal pain relief may take days to weeks after commencement of RT.17 It is estimated that a quarter of all patients with cancer develop bone metastases during the course of their disease,12 and most of those patients suffer from pain. Thus, inherent delay in pain relief before, during, and after RT results in significant morbidity for the cancer patient population if adequate analgesic management is not provided.

The low rate of appropriate analgesic intervention at the time of RO consultation may also be related to the low incidence of proper analgesic assessment. In our cohort, 80% of symptomatic patients had an opioid or nonopioid analgesic listed in their medications within the electronic medical record at time of consultation, but only 38% had the analgesic regimen and/or its effectiveness described in the History of the Present Illness section of the record. Inattentiveness to analgesic type, dosing, and effectiveness during consultation may result in any inadequacies of the analgesic regimen going unnoticed. Consistent with this notion, we found that the rate of appropriate intervention for patients with a PIR of ≥4 was higher among patients who had analgesic regimen reported in the consultation note. Thus, interventions to implement routine review and documentation of the analgesic regimen, for example within the electronic medical record, may be one way to improve pain management.

Another possible reason for low rates of acute pain management within the RO clinic is low provider confidence in regard to analgesic management. In a recent national survey, 96% of radiation oncologists stated they were at least moderately confident with assessment of pain, yet only 77% were at least moderately confident with titrating opioids, and just 56% were at least moderately confident with rotating opioids.10 Educational interventions that improve providers’ facility with analgesic management may increase the frequency of pain management in the RO clinic.

Patients seen on the dedicated palliative RO service had significantly higher rates of documented analgesic regimen assessment and appropriate intervention during RO consultation, compared with patients seen at Center 2 and those not seen on the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1. The improvements we observed in analgesic assessment and intervention at Center 1 for patients seen on the palliative RO service are likely owing to involvement of palliative RO and not to secular trends, because there were not similar improvements for patients at Center 1 who were not seen by the palliative RO service and those at Center 2, where there was no service.

At Center 1, the dedicated palliative RO service was created to provide specialized care to patients with metastatic disease undergoing palliative radiation. Within its structure, topics within palliative RO, such as technical aspects of palliative RT, symptom management, and communication are taught and reinforced in a case-based approach. Such palliative care awareness, integration, and education within RO achieved by the palliative RO service likely contribute to the improved rates of analgesic management we found in our study. We do note that rate of analgesic intervention in the palliative RO cohort, though higher than in the nonpalliative RO group, was still low, with only a third of patients receiving proper analgesic management. These findings highlight the importance of continued effort in increasing providers’ awareness of the need to assess pain and raise comfort with analgesic initiation and titration and of having dedicated palliative care clinicians embedded within the RO setting.

Since the data for this study was acquired, Center 2 has implemented a short palliative RO didactic course for residents, which improved their comfort levels in assessing analgesic effectiveness and intervening for uncontrolled pain.18 The impact of this intervention on clinical care will need to be evaluated, but the improved provider comfort levels may translate into better-quality care.

Limitations

An important limitation of this retrospective study is the reliance on the documentation provided in the consultation note for determining frequencies of analgesic regimen assessment and intervention. The actual rates of analgesic management that occurred in clinic may have been higher than reported in the documentation. However, such discrepancy in documentation of analgesic management would also be an area for quality improvement. Inadequate documentation limits the ability for proper follow-up of cancer pain as recommended by a joint guidance statement from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.19,20 The results of our study may also partly reflect a positive impact in documentation of analgesic management by a dedicated palliative RO service.

Given the multi-institutional nature of this study, it may be that general practice differences confound the impact of the dedicated palliative RO service at Center 1. However, with excluding Center 2, the dedicated service was still strongly associated with a higher rate of analgesic assessment within Center 1 and was almost significantly associated with appropriate analgesic intervention within Center 1.

We used a PIR of ≥4 as a threshold for appropriate analgesic regimen intervention because it is what is recommended by the NCCN guidelines. However, close attention should be paid to the impact that any amount of pain has on an individual patient. The functional, spiritual, and existential impact of pain is unique to each patient’s experience, and optimal symptom management should take those elements into account.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study indicates that advanced cancer patient pain assessment and intervention according to NCCN cancer pain management guidelines is not common in the RO setting, and it is an area that should be targeted for quality improvement because of the positive implications for patient well-being. Pain assessment and intervention were greater in the setting of a dedicated structure for palliative care within RO, suggesting that the integration of palliative care within RO is a promising means of improving quality of pain management.

This work was presented at the 2016 ASCO Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium (September 9-10, 2016), where this work received a Conquer Cancer Foundation Merit Award.

1. Amichetti M, Orrù P, Madeddu A, et al. Comparative evaluation of two hypofractionated radiotherapy regimens for painful bone metastases. Tumori. 2004;90(1):91-95.

2. Vuong S, Pulenzas N, DeAngelis C, et al. Inadequate pain management in cancer patients attending an outpatient palliative radiotherapy clinic. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(2):887-892.

3. Portenoy RK, Payne D, Jacobsen P. Breakthrough pain: characteristics and impact in patients with cancer pain. Pain. 1999;81(1-2):129-134.

4. Sze WM, Shelley M, Held I, Mason M. Palliation of metastatic bone pain: single fraction versus multifraction radiotherapy - a systematic review of the randomised trials. Sze WM, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(2):CD004721-CD004721.

5. Ratanatharathorn V, Powers WE, Moss WT, Perez CA. Bone metastasis: review and critical analysis of random allocation trials of local field treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(1):1-18.

6. Kirou-Mauro A, Hird A, Wong J, et al. Is response to radiotherapy in patients related to the severity of pretreatment pain? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(4):1208-1212.

7. Frassica DA. General principles of external beam radiation therapy for skeletal metastases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(415 Suppl):S158-S164.