User login

Carcinoma Erysipeloides of Papillary Serous Ovarian Cancer Mimicking Cellulitis of the Abdominal Wall

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIC ovarian cancer presented with progressing abdominal erythema and pain of 1 month’s duration. She had been diagnosed 4 years prior with grade 3, poorly differentiated papillary serous carcinoma involving the bilateral ovaries, uterine tubes, uterus, and omentum with lymphovascular invasion. She underwent tumor resection and debulking followed by paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy. The cancer recurred 2 years later with carcinomatous ascites. She declined chemotherapy but underwent therapeutic paracentesis.

One month prior to presentation, the patient developed a small, tender, erythematous patch on the abdomen. Her primary physician started her on cephalexin for presumed cellulitis without improvement. The erythema continued to spread on the abdomen with worsening pain, which prompted her presentation to the emergency department. She was admitted and started on intravenous vancomycin.

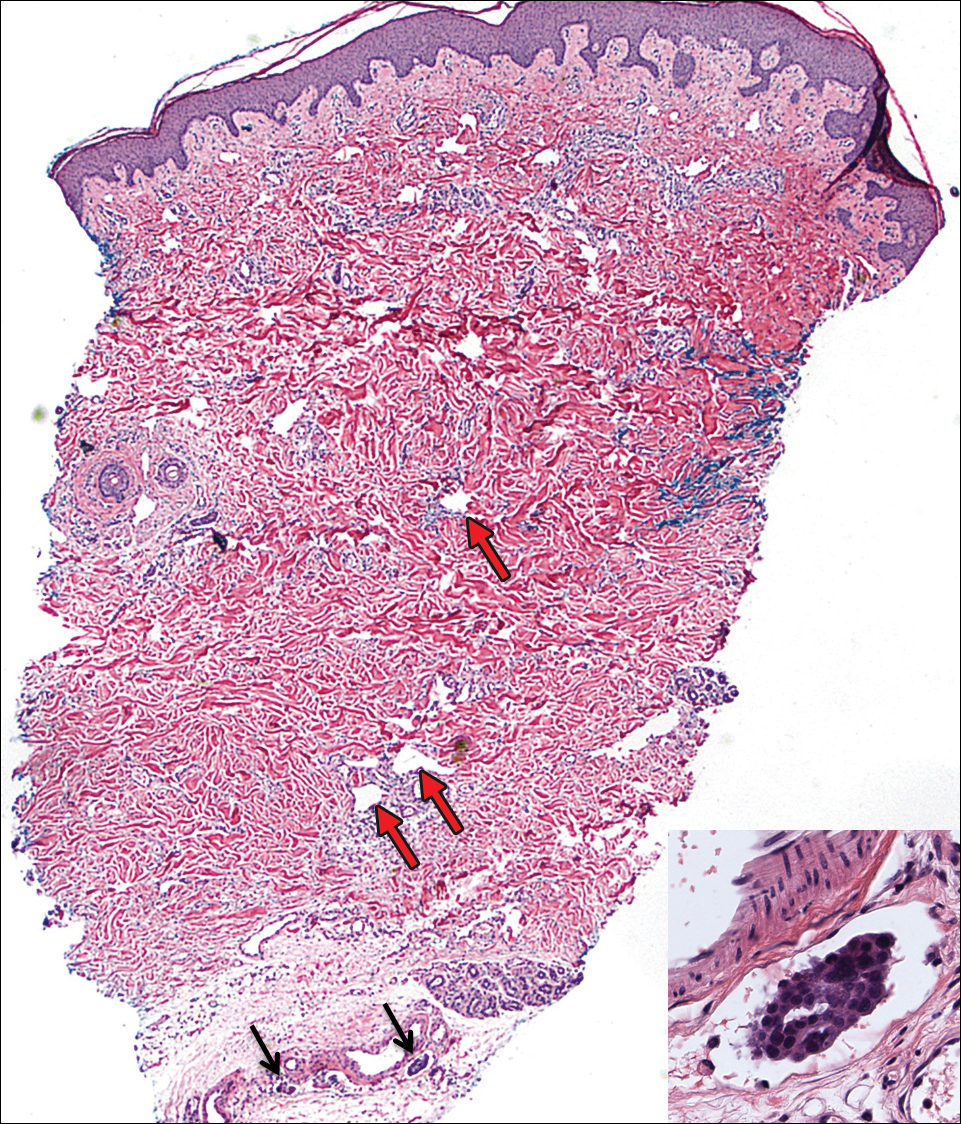

On admission to the hospital, the patient was cachexic and afebrile with a white blood cell count of 10,400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL). Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, 15×20-cm, erythematous, blanchable, indurated plaque in the periumbilical region (Figure 1). The plaque was tender to palpation with guarding but no increased warmth. Punch biopsies of the abdominal skin revealed carcinoma within the lymphatic channels in the deep dermis and dilated lymphatics throughout the overlying dermis (Figure 2). These findings were diagnostic for carcinoma erysipeloides. Tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Vancomycin was discontinued, and she was discharged with pain medication. She declined chemotherapy due to the potential side effects and elected to continue symptomatic management with palliative paracentesis. After she was discharged, she underwent a tunneled pleural catheterization for recurrent malignant pleural effusions.

Carcinoma erysipeloides is a rare cutaneous metastasis secondary to internal malignancy that presents as well-demarcated areas of erythema and is sometimes misdiagnosed as cellulitis or erysipelas. Histology is notable for lymphovascular congestion without inflammation. Carcinoma erysipeloides most commonly is associated with breast cancer, but it also has been described in cancers of the prostate, larynx, stomach, lungs, thyroid, parotid gland, fallopian tubes, cervix, pancreas, and metastatic melanoma.1-5 While the pathogenesis of carcinoma erysipeloides is poorly understood, it is thought to occur by direct spread of tumor cells from the lymph nodes to the cutaneous lymphatics, causing obstruction and edema.

Ovarian cancer has the highest mortality of all gynecologic cancers and often is associated with delayed diagnosis. Cutaneous metastasis is a late manifestation often presenting as subcutaneous nodules.6,7 Carcinoma erysipeloides is an even rarer presentation of ovarian cancer, with a poor prognosis and a median survival of 18 months.8 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term carcinoma erysipeloides revealed 9 cases of carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian cancer: 1 describing erythematous papules, plaques, and zosteriform vesicles on the upper thighs to the lower abdomen,9 and 8 describing erythematous plaques on the breasts.8,10 We report a case of carcinoma erysipeloides associated with stage IIIc ovarian cancer localized to the abdominal wall mimicking cellulitis. Our report reminds clinicians of this important diagnosis in ovarian cancer and of the importance of a skin biopsy to expedite a definitive diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry using ovarian tumor markers (eg, paired-box gene 8, cancer antigen 125) is an additional tool to accurately identify malignant cells in skin biopsy.8,10 Once diagnosed, primary treatment for carcinoma erysipeloides is treatment of the underlying malignancy.

- Cormio G, Capotorto M, Di Vagno G, et al. Skin metastases in ovarian carcinoma: a report of nine cases and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:682-685.

- Kim MK, Kim SH, Lee YY, et al. Metastatic skin lesions on lower extremities in a patient with recurrent serous papillary ovarian carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:142-145.

- Karmali S, Rudmik L, Temple W, et al. Melanoma erysipeloides. Can J Surg. 2005;48:159-160.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides of the breast in a patient with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:575-576.

- Hazelrigg DE, Rudolph AH. Inflammatory metastic carcinoma. carcinoma erysipelatoides. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:69-70.

- Cowan LJ, Roller JI, Connelly PJ, et al. Extraovarian stage IV peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma presenting as an asymptomatic skin lesion—a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57:433-435.

- Schonmann R, Altaras M, Biron T, et al. Inflammatory skin metastases from ovarian carcinoma—a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:670-672.

- Klein RL, Brown AR, Gomez-Castro CM, et al. Ovarian cancer metastatic to the breast presenting as inflammatory breast cancer: a case report and literature review. J Cancer. 2010;1:27-31.

- Lee HC, Chu CY, Hsiao CH. Carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian clear-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5828-5830.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Photo quiz. rash in a patient with ovarian cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:538, 575-576.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIC ovarian cancer presented with progressing abdominal erythema and pain of 1 month’s duration. She had been diagnosed 4 years prior with grade 3, poorly differentiated papillary serous carcinoma involving the bilateral ovaries, uterine tubes, uterus, and omentum with lymphovascular invasion. She underwent tumor resection and debulking followed by paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy. The cancer recurred 2 years later with carcinomatous ascites. She declined chemotherapy but underwent therapeutic paracentesis.

One month prior to presentation, the patient developed a small, tender, erythematous patch on the abdomen. Her primary physician started her on cephalexin for presumed cellulitis without improvement. The erythema continued to spread on the abdomen with worsening pain, which prompted her presentation to the emergency department. She was admitted and started on intravenous vancomycin.

On admission to the hospital, the patient was cachexic and afebrile with a white blood cell count of 10,400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL). Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, 15×20-cm, erythematous, blanchable, indurated plaque in the periumbilical region (Figure 1). The plaque was tender to palpation with guarding but no increased warmth. Punch biopsies of the abdominal skin revealed carcinoma within the lymphatic channels in the deep dermis and dilated lymphatics throughout the overlying dermis (Figure 2). These findings were diagnostic for carcinoma erysipeloides. Tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Vancomycin was discontinued, and she was discharged with pain medication. She declined chemotherapy due to the potential side effects and elected to continue symptomatic management with palliative paracentesis. After she was discharged, she underwent a tunneled pleural catheterization for recurrent malignant pleural effusions.

Carcinoma erysipeloides is a rare cutaneous metastasis secondary to internal malignancy that presents as well-demarcated areas of erythema and is sometimes misdiagnosed as cellulitis or erysipelas. Histology is notable for lymphovascular congestion without inflammation. Carcinoma erysipeloides most commonly is associated with breast cancer, but it also has been described in cancers of the prostate, larynx, stomach, lungs, thyroid, parotid gland, fallopian tubes, cervix, pancreas, and metastatic melanoma.1-5 While the pathogenesis of carcinoma erysipeloides is poorly understood, it is thought to occur by direct spread of tumor cells from the lymph nodes to the cutaneous lymphatics, causing obstruction and edema.

Ovarian cancer has the highest mortality of all gynecologic cancers and often is associated with delayed diagnosis. Cutaneous metastasis is a late manifestation often presenting as subcutaneous nodules.6,7 Carcinoma erysipeloides is an even rarer presentation of ovarian cancer, with a poor prognosis and a median survival of 18 months.8 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term carcinoma erysipeloides revealed 9 cases of carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian cancer: 1 describing erythematous papules, plaques, and zosteriform vesicles on the upper thighs to the lower abdomen,9 and 8 describing erythematous plaques on the breasts.8,10 We report a case of carcinoma erysipeloides associated with stage IIIc ovarian cancer localized to the abdominal wall mimicking cellulitis. Our report reminds clinicians of this important diagnosis in ovarian cancer and of the importance of a skin biopsy to expedite a definitive diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry using ovarian tumor markers (eg, paired-box gene 8, cancer antigen 125) is an additional tool to accurately identify malignant cells in skin biopsy.8,10 Once diagnosed, primary treatment for carcinoma erysipeloides is treatment of the underlying malignancy.

To the Editor:

A 40-year-old woman with a history of stage IIIC ovarian cancer presented with progressing abdominal erythema and pain of 1 month’s duration. She had been diagnosed 4 years prior with grade 3, poorly differentiated papillary serous carcinoma involving the bilateral ovaries, uterine tubes, uterus, and omentum with lymphovascular invasion. She underwent tumor resection and debulking followed by paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy. The cancer recurred 2 years later with carcinomatous ascites. She declined chemotherapy but underwent therapeutic paracentesis.

One month prior to presentation, the patient developed a small, tender, erythematous patch on the abdomen. Her primary physician started her on cephalexin for presumed cellulitis without improvement. The erythema continued to spread on the abdomen with worsening pain, which prompted her presentation to the emergency department. She was admitted and started on intravenous vancomycin.

On admission to the hospital, the patient was cachexic and afebrile with a white blood cell count of 10,400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL). Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, 15×20-cm, erythematous, blanchable, indurated plaque in the periumbilical region (Figure 1). The plaque was tender to palpation with guarding but no increased warmth. Punch biopsies of the abdominal skin revealed carcinoma within the lymphatic channels in the deep dermis and dilated lymphatics throughout the overlying dermis (Figure 2). These findings were diagnostic for carcinoma erysipeloides. Tissue and blood cultures were negative for bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Vancomycin was discontinued, and she was discharged with pain medication. She declined chemotherapy due to the potential side effects and elected to continue symptomatic management with palliative paracentesis. After she was discharged, she underwent a tunneled pleural catheterization for recurrent malignant pleural effusions.

Carcinoma erysipeloides is a rare cutaneous metastasis secondary to internal malignancy that presents as well-demarcated areas of erythema and is sometimes misdiagnosed as cellulitis or erysipelas. Histology is notable for lymphovascular congestion without inflammation. Carcinoma erysipeloides most commonly is associated with breast cancer, but it also has been described in cancers of the prostate, larynx, stomach, lungs, thyroid, parotid gland, fallopian tubes, cervix, pancreas, and metastatic melanoma.1-5 While the pathogenesis of carcinoma erysipeloides is poorly understood, it is thought to occur by direct spread of tumor cells from the lymph nodes to the cutaneous lymphatics, causing obstruction and edema.

Ovarian cancer has the highest mortality of all gynecologic cancers and often is associated with delayed diagnosis. Cutaneous metastasis is a late manifestation often presenting as subcutaneous nodules.6,7 Carcinoma erysipeloides is an even rarer presentation of ovarian cancer, with a poor prognosis and a median survival of 18 months.8 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term carcinoma erysipeloides revealed 9 cases of carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian cancer: 1 describing erythematous papules, plaques, and zosteriform vesicles on the upper thighs to the lower abdomen,9 and 8 describing erythematous plaques on the breasts.8,10 We report a case of carcinoma erysipeloides associated with stage IIIc ovarian cancer localized to the abdominal wall mimicking cellulitis. Our report reminds clinicians of this important diagnosis in ovarian cancer and of the importance of a skin biopsy to expedite a definitive diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry using ovarian tumor markers (eg, paired-box gene 8, cancer antigen 125) is an additional tool to accurately identify malignant cells in skin biopsy.8,10 Once diagnosed, primary treatment for carcinoma erysipeloides is treatment of the underlying malignancy.

- Cormio G, Capotorto M, Di Vagno G, et al. Skin metastases in ovarian carcinoma: a report of nine cases and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:682-685.

- Kim MK, Kim SH, Lee YY, et al. Metastatic skin lesions on lower extremities in a patient with recurrent serous papillary ovarian carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:142-145.

- Karmali S, Rudmik L, Temple W, et al. Melanoma erysipeloides. Can J Surg. 2005;48:159-160.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides of the breast in a patient with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:575-576.

- Hazelrigg DE, Rudolph AH. Inflammatory metastic carcinoma. carcinoma erysipelatoides. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:69-70.

- Cowan LJ, Roller JI, Connelly PJ, et al. Extraovarian stage IV peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma presenting as an asymptomatic skin lesion—a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57:433-435.

- Schonmann R, Altaras M, Biron T, et al. Inflammatory skin metastases from ovarian carcinoma—a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:670-672.

- Klein RL, Brown AR, Gomez-Castro CM, et al. Ovarian cancer metastatic to the breast presenting as inflammatory breast cancer: a case report and literature review. J Cancer. 2010;1:27-31.

- Lee HC, Chu CY, Hsiao CH. Carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian clear-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5828-5830.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Photo quiz. rash in a patient with ovarian cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:538, 575-576.

- Cormio G, Capotorto M, Di Vagno G, et al. Skin metastases in ovarian carcinoma: a report of nine cases and a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:682-685.

- Kim MK, Kim SH, Lee YY, et al. Metastatic skin lesions on lower extremities in a patient with recurrent serous papillary ovarian carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:142-145.

- Karmali S, Rudmik L, Temple W, et al. Melanoma erysipeloides. Can J Surg. 2005;48:159-160.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Carcinoma erysipeloides of the breast in a patient with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:575-576.

- Hazelrigg DE, Rudolph AH. Inflammatory metastic carcinoma. carcinoma erysipelatoides. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:69-70.

- Cowan LJ, Roller JI, Connelly PJ, et al. Extraovarian stage IV peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma presenting as an asymptomatic skin lesion—a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57:433-435.

- Schonmann R, Altaras M, Biron T, et al. Inflammatory skin metastases from ovarian carcinoma—a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:670-672.

- Klein RL, Brown AR, Gomez-Castro CM, et al. Ovarian cancer metastatic to the breast presenting as inflammatory breast cancer: a case report and literature review. J Cancer. 2010;1:27-31.

- Lee HC, Chu CY, Hsiao CH. Carcinoma erysipeloides from ovarian clear-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5828-5830.

- Godinez-Puig V, Frangos J, Hollmann TJ, et al. Photo quiz. rash in a patient with ovarian cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:538, 575-576.

Practice Points

- Carcinoma erysipeloides is a rare cutaneous marker of metastatic ovarian cancer.

- Clinicians should be aware of carcinoma erysipeloides in ovarian cancer and maintain a low threshold for biopsy for accurate diagnosis and management planning.

Metastatic Melanoma and Prostatic Adenocarcinoma in the Same Sentinel Lymph Node

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

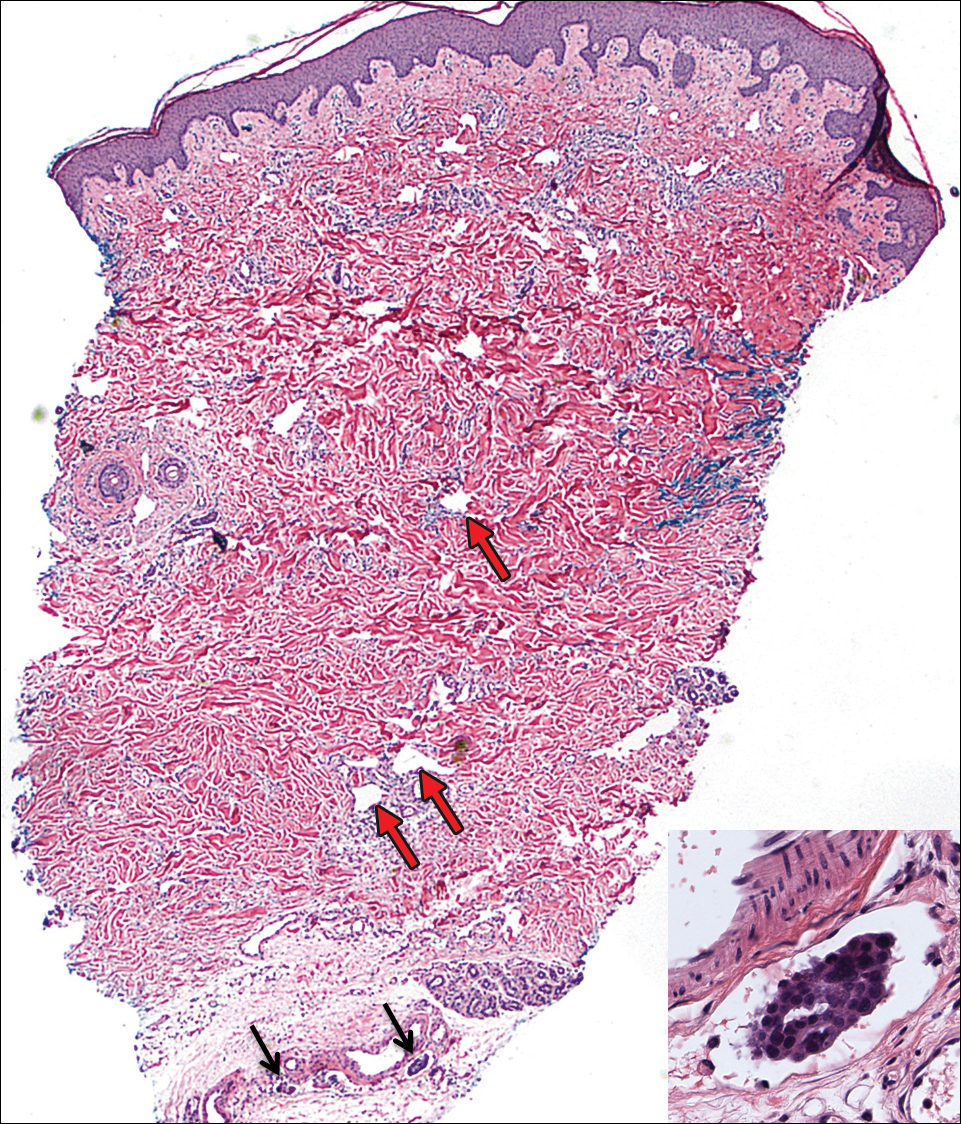

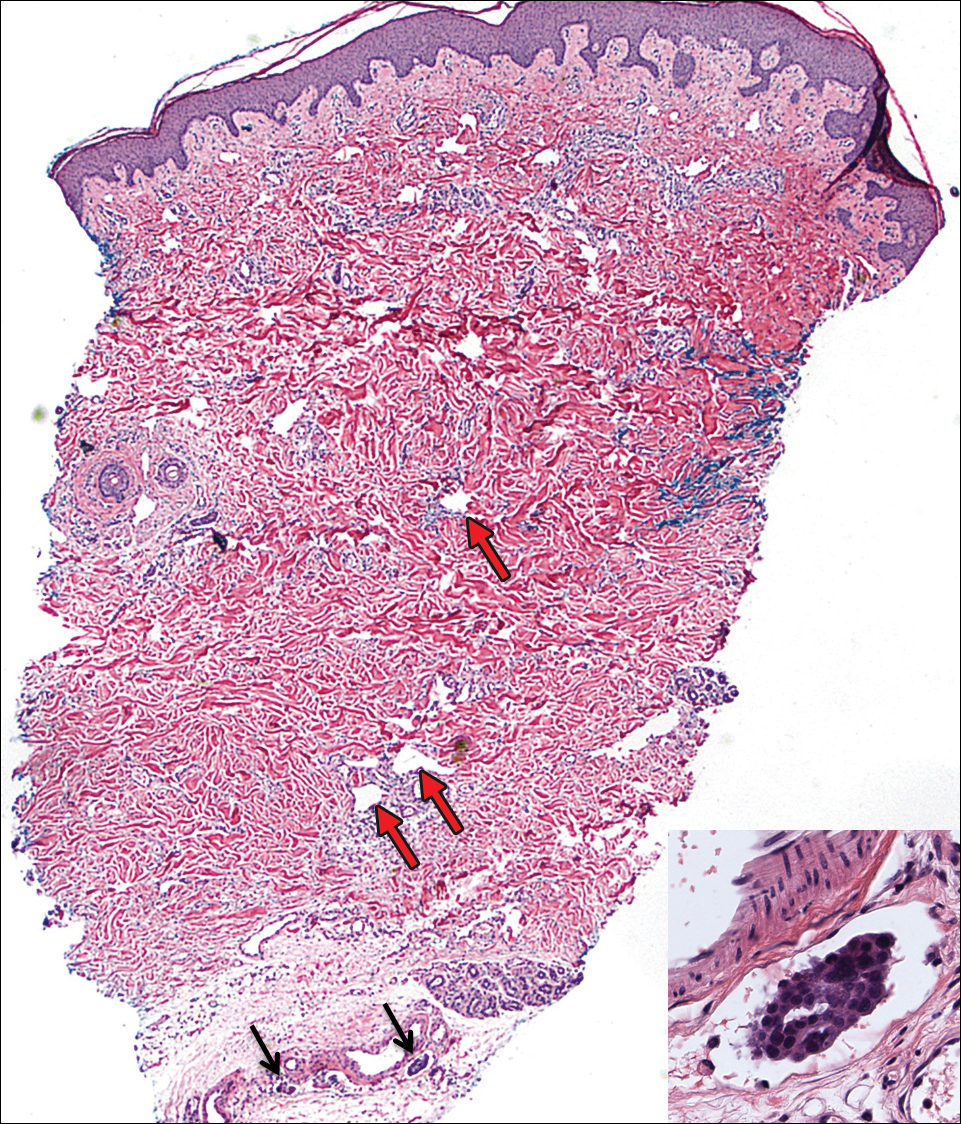

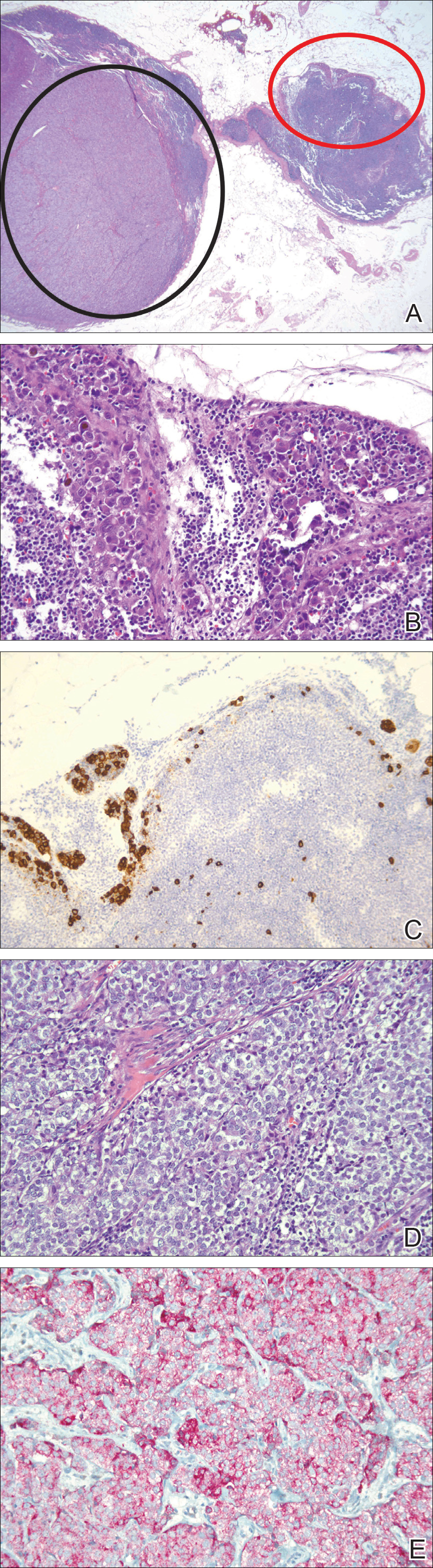

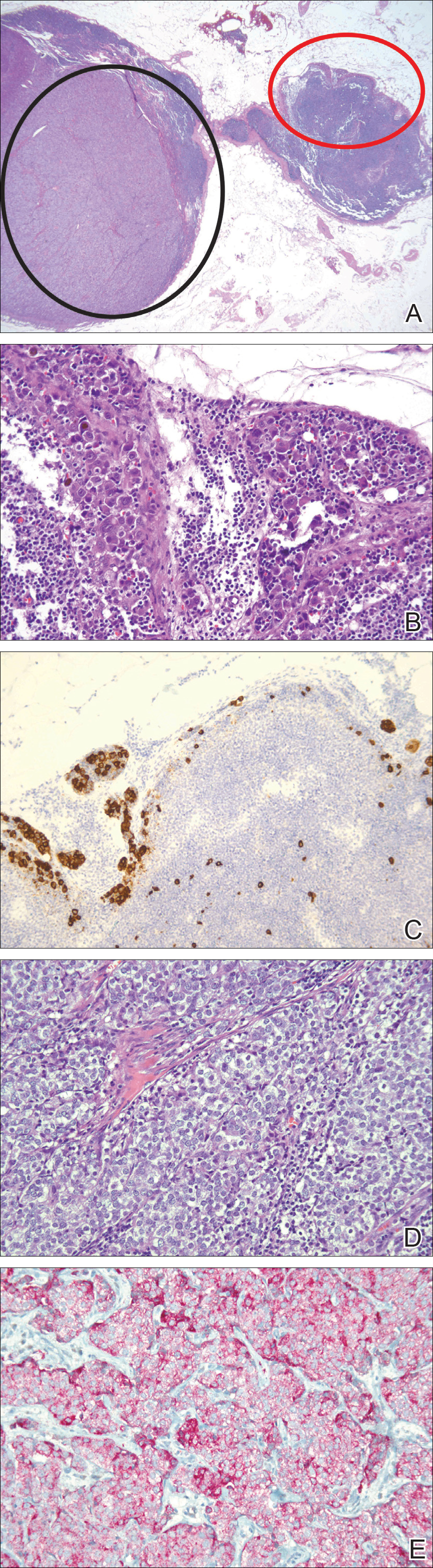

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

To the Editor:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsies routinely are performed to detect regional metastases in a variety of malignancies, including breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Histologic examination of an SLN occasionally enables detection of other unsuspected underlying diseases that typically are inflammatory in nature. Although concomitant hematolymphoid malignancy, particularly chronic lymphocytic leukemia, has been reported in SLNs, collision of 2 different solid tumors in the same SLN is rare.1,2 We report a unique case documenting collision of both metastatic melanoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN to raise awareness of the diagnostic challenges occurring in patients with coexisting malignancies.

A 71-year-old man with a history of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma to the bone presented for treatment of a melanoma that was newly diagnosed by an outside dermatologist. The patient’s medical history was notable for radical prostatectomy performed 15 years prior for treatment of a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Gleason score unknown) followed by bilateral orchiectomy performed 7 years later after his serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level began to rise, with no response to goserelin (a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist) therapy. Two years prior to the diagnosis of metastatic disease, his PSA level started to rise again and the patient received bicalutamide with little improvement, followed by 8 cycles of docetaxel. His PSA level improved and he most recently was being treated with abiraterone acetate. The patient’s latest computed tomography scan showed that the bony metastases secondary to prostatic adenocarcinoma had progressed. His serum PSA level was 105 ng/mL (reference range, <4.0 ng/mL) at the current presentation, elevated from 64 ng/mL one year prior.

Recently, the patient had noted a changing pigmented skin lesion on the left side of the flank. The patient described the lesion as a “black mole” first appearing 2 years prior, which had begun to ooze, change shape, and become darker and more nodular. A shave biopsy revealed a primary cutaneous malignant melanoma at least 3.4 mm in depth with ulceration and a mitotic rate of 15/mm2. No molecular studies were performed on the melanoma. Standard treatment via wide local excision and sentinel lymphadenectomy was planned.

Lymphoscintigraphy revealed 3 left draining axillary lymph nodes. The patient was treated with wide local excision and left axillary SLN biopsy. Five SLNs and 3 non-SLNs were excised. Per protocol, all SLNs were examined pathologically with serial sections: 2 hematoxylin and eosin–stained levels, S-100, and melan-A immunohistochemical stains. No residual melanoma was identified in the wide-excision specimen. Examination of the left axillary SLNs revealed metastatic melanoma in 3 of 5 SLNs. Two SLNs demonstrated total replacement by metastatic melanoma. A third SLN revealed a metastatic malignant neoplasm occupying 75% of the nodal area (Figure, A). S-100 and melan-A immunohistochemical staining were negative in this nodule but revealed small aggregates and isolated tumor cells distinct from this nodule that were diagnostic of micrometastatic melanoma (Figures, B and C). The tumor cells in the large nodule were histologically distinct from the melanoma and were instead composed of nests of epithelioid cells with clear cytoplasm (Figure, D). Upon further immunohistochemical staining, this tumor was strongly positive for AE1/AE3 keratin and PIN4 cocktail (cytokeratin 5, cytokeratin 15, p63, and p504s/alpha-methylacyl-CoA-racemase)(Figure, E) with focal positivity for PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase, diagnostic of metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate origin.

A positron emission tomography scan performed a few days after the discovery of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in the SLNs showed expected postoperative changes (eg, increased activity from procedure-related inflammation) in the left side of the flank and axilla as well as moderately hypermetabolic left supraclavicular lymph nodes suspicious for viable metastatic disease. Subsequent fine-needle aspiration of the aforementioned lymph nodes revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. The preoperative lymphoscintigraphy at the time of SLN biopsy did not show drainage to the left supraclavicular nodal basin.

Based on a discussion of the patient’s case during a multidisciplinary tumor board consultation, the benefit of performing completion lymph node dissection for melanoma management did not outweigh the risks. Accordingly, the patient received adjuvant radiation therapy to the axillary nodal basin. He was started on ketoconazole and zoledronic acid therapy for metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma and was alive with disease at 6-month follow-up. The finding of both metastatic melanoma and prostate adenocarcinoma detected in an SLN after wide excision and SLN biopsy for cutaneous melanoma is a unique report of collision of these 2 tumors. Rare cases of collision between 2 solid tumors occurring in the same lymph node have involved prostate adenocarcinoma as one of the solid tumor components.1,3 Detection of tumor collision on lymph node biopsy between prostatic adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma has been documented in 2 separate cases.1 Three additional cases of concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma identified on lymph node biopsy have been reported.1,3 Although never proven statistically, it is likely that these concurrent diagnoses are due to the high incidences of prostate and colorectal adenocarcinomas in the general US population; they are ranked first and third, respectively, for cancer incidence in US males.4

As demonstrated in the current case and the available literature, immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic source of the metastases. Furthermore, thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Earlier identification of second malignancies in SLNs can alert the clinician to the presence of relapse of a known concurrent malignancy before it is clinically apparent, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease. As has been demonstrated for lymphoma and melanoma, in rare cases awareness of the possibility of a second malignancy in the SLN can result in earlier initial diagnosis of undiscovered malignancy.2

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

- Sughayer MA, Zakarneh L, Abu-Shakra R. Collision metastasis of breast and ovarian adenocarcinoma in axillary lymph nodes: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:423-427.

- Farma JM, Zager JS, Barnica-Elvir V, et al. A collision of diseases: chronic lymphocytic leukemia discovered during lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1360-1364.

- Wade ZK, Shippey JE, Hamon GA, et al. Collision metastasis of prostatic and colonic adenocarcinoma: report of 2 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:318-320.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30.

Practice Points

- Immunohistochemical stains play a vital role in the detection of tumor collision phenomena as well as identification of histologic sources of metastases.

- Thorough histopathologic examination of biopsy specimens in the context of a patient’s clinical history remains paramount in obtaining an accurate diagnosis, enhancing the possibility of more effective treatment of earlier disease.

VIDEO: U.S. melanoma incidence hits all-time high

SAN DIEGO –

“Nobody’s quite sure why the [melanoma] rates are still rising so dramatically,” Darrell S. Rigel, MD, said in a video interview during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. The increase remains even after adjustment of incidence rates for the increasing mean age of U.S. adults.

The American Cancer Society reported that the estimated annual incidence rate for invasive melanoma will be 91,270 cases for 2018, following what the society called a rapid rise in the rate for the past 30 years. Add to that the estimate of more than 87,000 U.S. cases of in situ melanoma for an overall annual U.S. rate of 178,560, Dr. Rigel said.

Melanoma has a latency of 5-20 years, “so what we’re seeing right now are the effects of what happened 5, 10, or 20 years ago,” said Dr. Rigel, a dermatologist at New York University.

During a talk at the meeting, Dr. Rigel said that based on current incident levels he projected a lifetime U.S. incidence rate of invasive melanoma of one case for every 40 adults by the end of this decade, and a lifetime incidence rate for either invasive or in situ melanoma of one case for every 20 adults by 2020.

A positive trend is that for the first time, the number of melanoma deaths has started to fall, with an estimated 9,320 deaths from melanoma in 2018 according to American Cancer Society statistics, down from a peak of 10,130 melanoma deaths in 2016, Dr. Rigel said.

SAN DIEGO –

“Nobody’s quite sure why the [melanoma] rates are still rising so dramatically,” Darrell S. Rigel, MD, said in a video interview during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. The increase remains even after adjustment of incidence rates for the increasing mean age of U.S. adults.

The American Cancer Society reported that the estimated annual incidence rate for invasive melanoma will be 91,270 cases for 2018, following what the society called a rapid rise in the rate for the past 30 years. Add to that the estimate of more than 87,000 U.S. cases of in situ melanoma for an overall annual U.S. rate of 178,560, Dr. Rigel said.

Melanoma has a latency of 5-20 years, “so what we’re seeing right now are the effects of what happened 5, 10, or 20 years ago,” said Dr. Rigel, a dermatologist at New York University.

During a talk at the meeting, Dr. Rigel said that based on current incident levels he projected a lifetime U.S. incidence rate of invasive melanoma of one case for every 40 adults by the end of this decade, and a lifetime incidence rate for either invasive or in situ melanoma of one case for every 20 adults by 2020.

A positive trend is that for the first time, the number of melanoma deaths has started to fall, with an estimated 9,320 deaths from melanoma in 2018 according to American Cancer Society statistics, down from a peak of 10,130 melanoma deaths in 2016, Dr. Rigel said.

SAN DIEGO –

“Nobody’s quite sure why the [melanoma] rates are still rising so dramatically,” Darrell S. Rigel, MD, said in a video interview during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. The increase remains even after adjustment of incidence rates for the increasing mean age of U.S. adults.

The American Cancer Society reported that the estimated annual incidence rate for invasive melanoma will be 91,270 cases for 2018, following what the society called a rapid rise in the rate for the past 30 years. Add to that the estimate of more than 87,000 U.S. cases of in situ melanoma for an overall annual U.S. rate of 178,560, Dr. Rigel said.

Melanoma has a latency of 5-20 years, “so what we’re seeing right now are the effects of what happened 5, 10, or 20 years ago,” said Dr. Rigel, a dermatologist at New York University.

During a talk at the meeting, Dr. Rigel said that based on current incident levels he projected a lifetime U.S. incidence rate of invasive melanoma of one case for every 40 adults by the end of this decade, and a lifetime incidence rate for either invasive or in situ melanoma of one case for every 20 adults by 2020.

A positive trend is that for the first time, the number of melanoma deaths has started to fall, with an estimated 9,320 deaths from melanoma in 2018 according to American Cancer Society statistics, down from a peak of 10,130 melanoma deaths in 2016, Dr. Rigel said.

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

VIDEO: Bioimpedance provides accurate assessment of Mohs surgical margins

SAN DIEGO – In assessing tumor-free margins during Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer, of histologic sections, in a single-center, pilot study of bioimpedance in 151 specimens from 50 consecutive patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

If the finding of high diagnostic accuracy using bioimpedance spectroscopy is confirmed in larger numbers of patients and specimens run at multiple sites, this approach could “potentially revolutionize what happens with the way Mohs sections are processed in the future” by potentially shaving many minutes off the duration of a standard procedure, Darrell S. Rigel, MD, said in a video interview during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Usually, it takes 10-20 minutes to process and examine Mohs specimens at each stage of the surgical procedure to determine whether additional excision must remove residual cancer cells, said Dr. Rigel, a dermatologist at New York University. In contrast, assessment for residual cancer cells in the surgical field takes less than a minute using bioimpedance spectroscopy, which relies on differences in electrical conductivity between benign and cancerous cells to identify cancer cells remaining at the surgical margins.

The results of the study were presented in a poster at the meeting, by a research associate of Dr. Rigel’s, Ryan Svoboda, MD, of the National Society for Cutaneous Medicine, New York.

The researchers used a bioimpedance spectroscopy device made by NovaScan to assess 151 histology slides prepared during Mohs micrographic surgery on patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer, and compared the findings against the gold standard of histological slide examination. By this criterion, bioimpedance spectroscopy identified 105 true negatives and 2 false negatives, and 43 true positives and 1 false positive. Calculations showed that this equated to 95.6% sensitivity, 99.1% specificity, a 97.7% positive predictive value, and a 98.1% negative predictive value.

These may be underestimates of the accuracy of bioimpedance spectroscopy because the calculations presume that conventional histology is always correct, but Dr. Rigel noted that sometimes the histological diagnosis is wrong.

SOURCE: Svoboda R et al. Poster 7304.

SAN DIEGO – In assessing tumor-free margins during Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer, of histologic sections, in a single-center, pilot study of bioimpedance in 151 specimens from 50 consecutive patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

If the finding of high diagnostic accuracy using bioimpedance spectroscopy is confirmed in larger numbers of patients and specimens run at multiple sites, this approach could “potentially revolutionize what happens with the way Mohs sections are processed in the future” by potentially shaving many minutes off the duration of a standard procedure, Darrell S. Rigel, MD, said in a video interview during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Usually, it takes 10-20 minutes to process and examine Mohs specimens at each stage of the surgical procedure to determine whether additional excision must remove residual cancer cells, said Dr. Rigel, a dermatologist at New York University. In contrast, assessment for residual cancer cells in the surgical field takes less than a minute using bioimpedance spectroscopy, which relies on differences in electrical conductivity between benign and cancerous cells to identify cancer cells remaining at the surgical margins.

The results of the study were presented in a poster at the meeting, by a research associate of Dr. Rigel’s, Ryan Svoboda, MD, of the National Society for Cutaneous Medicine, New York.

The researchers used a bioimpedance spectroscopy device made by NovaScan to assess 151 histology slides prepared during Mohs micrographic surgery on patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer, and compared the findings against the gold standard of histological slide examination. By this criterion, bioimpedance spectroscopy identified 105 true negatives and 2 false negatives, and 43 true positives and 1 false positive. Calculations showed that this equated to 95.6% sensitivity, 99.1% specificity, a 97.7% positive predictive value, and a 98.1% negative predictive value.

These may be underestimates of the accuracy of bioimpedance spectroscopy because the calculations presume that conventional histology is always correct, but Dr. Rigel noted that sometimes the histological diagnosis is wrong.

SOURCE: Svoboda R et al. Poster 7304.

SAN DIEGO – In assessing tumor-free margins during Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer, of histologic sections, in a single-center, pilot study of bioimpedance in 151 specimens from 50 consecutive patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

If the finding of high diagnostic accuracy using bioimpedance spectroscopy is confirmed in larger numbers of patients and specimens run at multiple sites, this approach could “potentially revolutionize what happens with the way Mohs sections are processed in the future” by potentially shaving many minutes off the duration of a standard procedure, Darrell S. Rigel, MD, said in a video interview during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Usually, it takes 10-20 minutes to process and examine Mohs specimens at each stage of the surgical procedure to determine whether additional excision must remove residual cancer cells, said Dr. Rigel, a dermatologist at New York University. In contrast, assessment for residual cancer cells in the surgical field takes less than a minute using bioimpedance spectroscopy, which relies on differences in electrical conductivity between benign and cancerous cells to identify cancer cells remaining at the surgical margins.

The results of the study were presented in a poster at the meeting, by a research associate of Dr. Rigel’s, Ryan Svoboda, MD, of the National Society for Cutaneous Medicine, New York.

The researchers used a bioimpedance spectroscopy device made by NovaScan to assess 151 histology slides prepared during Mohs micrographic surgery on patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer, and compared the findings against the gold standard of histological slide examination. By this criterion, bioimpedance spectroscopy identified 105 true negatives and 2 false negatives, and 43 true positives and 1 false positive. Calculations showed that this equated to 95.6% sensitivity, 99.1% specificity, a 97.7% positive predictive value, and a 98.1% negative predictive value.

These may be underestimates of the accuracy of bioimpedance spectroscopy because the calculations presume that conventional histology is always correct, but Dr. Rigel noted that sometimes the histological diagnosis is wrong.

SOURCE: Svoboda R et al. Poster 7304.

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

Key clinical point: Bioimpedance spectroscopy showed excellent diagnostic accuracy for cancer cells on Mohs surgical margins.

Major finding: Bioimpedance spectroscopy had a sensitivity of 95.6% and specificity of 99.1% compared with Mohs histology.

Study details: A single-center pilot study with 151 Mohs surgical specimens taken from 50 patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by NovaScan, the company developing the device tested in the study. Dr. Rigel has been a consultant to NovaScan and to Castle Biosciences, DermTech, Ferndale, Myriad, and Neutrogena, and has received research support from Castle and Neutrogena.

Source: Svoboda R et al. Poster 7304.

Evaluating Dermatology Apps for Patient Education

Topical imiquimod helps clear blurred lines in lentigo maligna excision

according to a study from the University of Utah.

Lentigo maligna is a subtype of melanoma in situ, usually occurring in the head and neck regions, the researchers said.

“Neoadjuvant topical imiquimod 5% cream applied 5 times weekly for 8 weeks was associated with decreased MDCs in LM treatment sites compared with the MDCs of negative control sites,” wrote Shadai Flores of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and her colleagues.

Previously, the ability to distinguish between the surgical border and surrounding background melanocytic hyperplasia was uncertain. Because of this uncertainty, LM removal required an average margin of 7.2 mm. Another study showed that topical imiquimod 5% cream enabled the removal of most LM tumors with 2-mm margins. This study “sought to evaluate MDCs in imiquimod-treated LM and negative control biopsy specimens to determine if there was a measurable difference in melanocyte density,” the researchers wrote in a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology.

The study prospectively followed 52 cases of LM treated with imiquimod 5% topical cream 5 days per week for 8 weeks followed by conservative staged excisions with 2-mm margins. Treatment with imiquimod 5% of LM was followed by a 2- to 4-month recuperation period before surgery could be performed. All patients in the study were treated by one Mohs surgeon at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the university.

To establish an MDC baseline, a 10-mm long fusiform biopsy was taken as a negative control. The negative control sample site and the LM site were separated by approximately 6 cm, found on the same side of the body, and showed similar color changes. After a negative control was taken, an LM lesion was resected and subsequently quadrisected. The MDCs then were concurrently counted by the researchers and compared with the negative controls.

Of the 52 LM specimens, 44 (85%) exhibited decreases in MDCs, compared with the negative controls. The median MDC from post–imiquimod-treated sites was 14.4, with a range of 0.5-26.6. This showed marked improvement over the negative controls, which had a median MDC of 20.0 (range of 9.0-36.7). A 2-tailed paired t test revealed that the results displayed statistical significance (P less than .001). Residual LM was seen in the central areas of 9 (17%) specimens, but 43 (83%) had no indication of residual LM.

“The decreased melanocytic hyperplasia in imiquimod-treated sites reduced ambiguity in making a distinction between the border of the excised LM and background melanocytic hyperplasia,” noted Ms. Flores and her colleagues.

The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Flores S et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Feb 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5632.

according to a study from the University of Utah.

Lentigo maligna is a subtype of melanoma in situ, usually occurring in the head and neck regions, the researchers said.

“Neoadjuvant topical imiquimod 5% cream applied 5 times weekly for 8 weeks was associated with decreased MDCs in LM treatment sites compared with the MDCs of negative control sites,” wrote Shadai Flores of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and her colleagues.

Previously, the ability to distinguish between the surgical border and surrounding background melanocytic hyperplasia was uncertain. Because of this uncertainty, LM removal required an average margin of 7.2 mm. Another study showed that topical imiquimod 5% cream enabled the removal of most LM tumors with 2-mm margins. This study “sought to evaluate MDCs in imiquimod-treated LM and negative control biopsy specimens to determine if there was a measurable difference in melanocyte density,” the researchers wrote in a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology.

The study prospectively followed 52 cases of LM treated with imiquimod 5% topical cream 5 days per week for 8 weeks followed by conservative staged excisions with 2-mm margins. Treatment with imiquimod 5% of LM was followed by a 2- to 4-month recuperation period before surgery could be performed. All patients in the study were treated by one Mohs surgeon at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the university.

To establish an MDC baseline, a 10-mm long fusiform biopsy was taken as a negative control. The negative control sample site and the LM site were separated by approximately 6 cm, found on the same side of the body, and showed similar color changes. After a negative control was taken, an LM lesion was resected and subsequently quadrisected. The MDCs then were concurrently counted by the researchers and compared with the negative controls.

Of the 52 LM specimens, 44 (85%) exhibited decreases in MDCs, compared with the negative controls. The median MDC from post–imiquimod-treated sites was 14.4, with a range of 0.5-26.6. This showed marked improvement over the negative controls, which had a median MDC of 20.0 (range of 9.0-36.7). A 2-tailed paired t test revealed that the results displayed statistical significance (P less than .001). Residual LM was seen in the central areas of 9 (17%) specimens, but 43 (83%) had no indication of residual LM.

“The decreased melanocytic hyperplasia in imiquimod-treated sites reduced ambiguity in making a distinction between the border of the excised LM and background melanocytic hyperplasia,” noted Ms. Flores and her colleagues.

The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Flores S et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Feb 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5632.

according to a study from the University of Utah.

Lentigo maligna is a subtype of melanoma in situ, usually occurring in the head and neck regions, the researchers said.

“Neoadjuvant topical imiquimod 5% cream applied 5 times weekly for 8 weeks was associated with decreased MDCs in LM treatment sites compared with the MDCs of negative control sites,” wrote Shadai Flores of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and her colleagues.

Previously, the ability to distinguish between the surgical border and surrounding background melanocytic hyperplasia was uncertain. Because of this uncertainty, LM removal required an average margin of 7.2 mm. Another study showed that topical imiquimod 5% cream enabled the removal of most LM tumors with 2-mm margins. This study “sought to evaluate MDCs in imiquimod-treated LM and negative control biopsy specimens to determine if there was a measurable difference in melanocyte density,” the researchers wrote in a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology.

The study prospectively followed 52 cases of LM treated with imiquimod 5% topical cream 5 days per week for 8 weeks followed by conservative staged excisions with 2-mm margins. Treatment with imiquimod 5% of LM was followed by a 2- to 4-month recuperation period before surgery could be performed. All patients in the study were treated by one Mohs surgeon at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the university.

To establish an MDC baseline, a 10-mm long fusiform biopsy was taken as a negative control. The negative control sample site and the LM site were separated by approximately 6 cm, found on the same side of the body, and showed similar color changes. After a negative control was taken, an LM lesion was resected and subsequently quadrisected. The MDCs then were concurrently counted by the researchers and compared with the negative controls.

Of the 52 LM specimens, 44 (85%) exhibited decreases in MDCs, compared with the negative controls. The median MDC from post–imiquimod-treated sites was 14.4, with a range of 0.5-26.6. This showed marked improvement over the negative controls, which had a median MDC of 20.0 (range of 9.0-36.7). A 2-tailed paired t test revealed that the results displayed statistical significance (P less than .001). Residual LM was seen in the central areas of 9 (17%) specimens, but 43 (83%) had no indication of residual LM.

“The decreased melanocytic hyperplasia in imiquimod-treated sites reduced ambiguity in making a distinction between the border of the excised LM and background melanocytic hyperplasia,” noted Ms. Flores and her colleagues.

The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Flores S et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Feb 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5632.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Neoadjuvant, topical imiquimod 5% cream is associated with a decrease in melanocyte density counts (MDC).

Major finding: Of 52 patient specimens, 44 (85%) exhibited decreases in MDCs, compared with the negative controls.

Study details: A prospective study of 52 cases of lentigo maligna treated with imiquimod 5% topical cream 5 days per week for 8 weeks, followed by conservative staged excisions with 2-mm margins.

Disclosures: The authors had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Flores S et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Feb 16. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5632.

Concurrent ipilimumab and CMV colitis refractory to oral steroids

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, including anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (anti-CTLA4) and anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (anti-PD-1) antibodies, have demonstrated clinical and survival benefits in a variety of malignancies, which has led to an expansion in their role in oncology. In melanoma, the anti-CTLA-4 antibody, ipilimumab, has demonstrated a survival benefit in patients with advanced metastatic melanoma and in patients with resectable disease with lymph node involvement.1,2

Ipilimumab exerts its effect by binding CTLA-4 on conventional and regulatory T cells, thus blocking inhibitory signals on T cells, which leads to an antitumor response.3 The increased immune response counteracts the immune-evading mechanisms of the tumor. With increased use of these agents, immune-related adverse events (irAEs) have become more prevalent. The most common irAEs secondary to ipilimumab are skin rash, colitis/diarrhea, hepatitis, pneumonitis, and various endocrinopathies.4 In a phase 3 trial of adjuvant ipilimumab in patients with resected stage III melanoma, grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred in 54.1% of participants in the ipilimumab arm, the most common being diarrhea and colitis (9.8% and 6.8%, respectively).2Recognition and management of irAEs has led to the implementation of treatment guidelines.4,5 Management of irAEs includes checkpoint inhibitor discontinuation and reversal of the immune response by institution of immunosuppression with corticosteroids.

Case presentation and summary

A 40-year-old white woman with stage IIIB BRAF V600E-positive melanoma presented with diarrhea refractory to high-dose prednisone (1 mg/kg BID). She had recently undergone wide local excision and sentinel node biopsy and received her inaugural dose of ipilimumab (10 mg/kg).

The patient first presented with loose, watery stools that had begun 8 days after she had received her first dose of adjuvant ipilimumab. She was admitted to the hospital, and intravenous methylprednisolone was initiated along with empiric ciprofloxacin (400 mg, IVPB Q12h) and metronidazole (500 mg, IVPB Q8h) as infectious causes were concurrently ruled out. During this initial admission, the patient’s stool was negative for Clostridium difficile toxin, ova, and parasites, as well as enteric pathogens by culture. After infectious causes were excluded, she was diagnosed with ipilimumab-induced colitis. Antibiotics were discontinued, and the patient ultimately noted improvement in her symptoms. On hospital day 7, she was experiencing only 2 bowel movements a day and was discharged on 80 mg of prednisone twice daily.

After discharge the patient noted persistence of her symptoms. At her follow-up, 9 days after discharge, the patient noted continued symptoms of low-grade diarrhea. She failed a trial of steroid tapering due to exacerbation of her abdominal pain and frequency of diarrhea. Further investigation was negative for C. diff toxin and a computed-tomography scan was consistent with continuing colitis. The patient’s symptoms continued to worsen, with recurrence of grade 3 diarrhea, and she was ultimately readmitted 17 days after her earlier discharge (36 days after her first ipilimumab dosing).

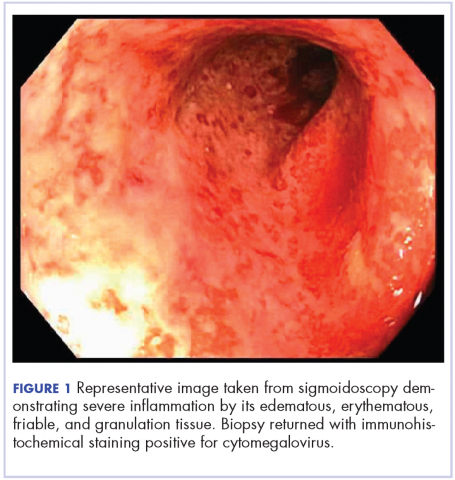

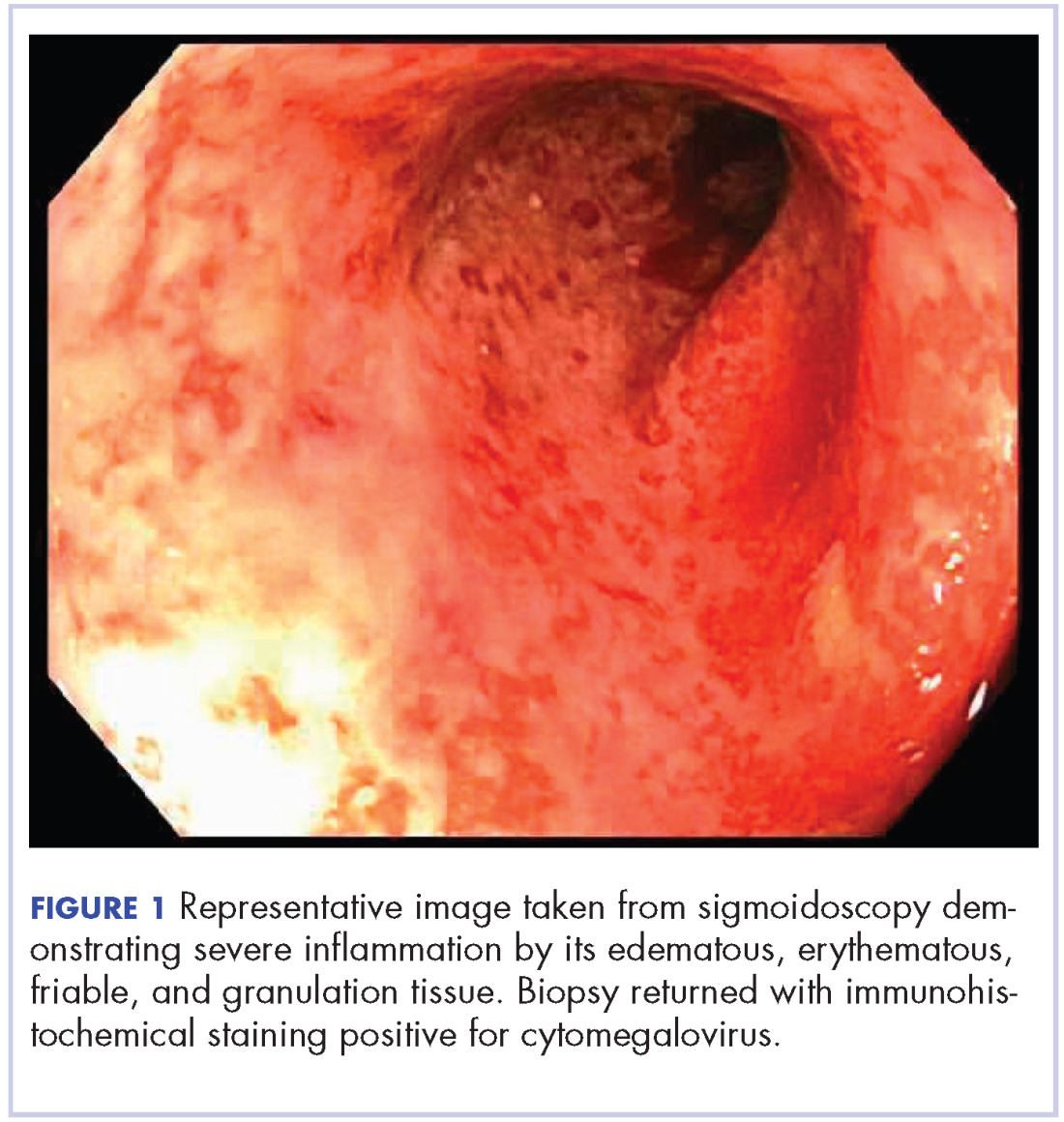

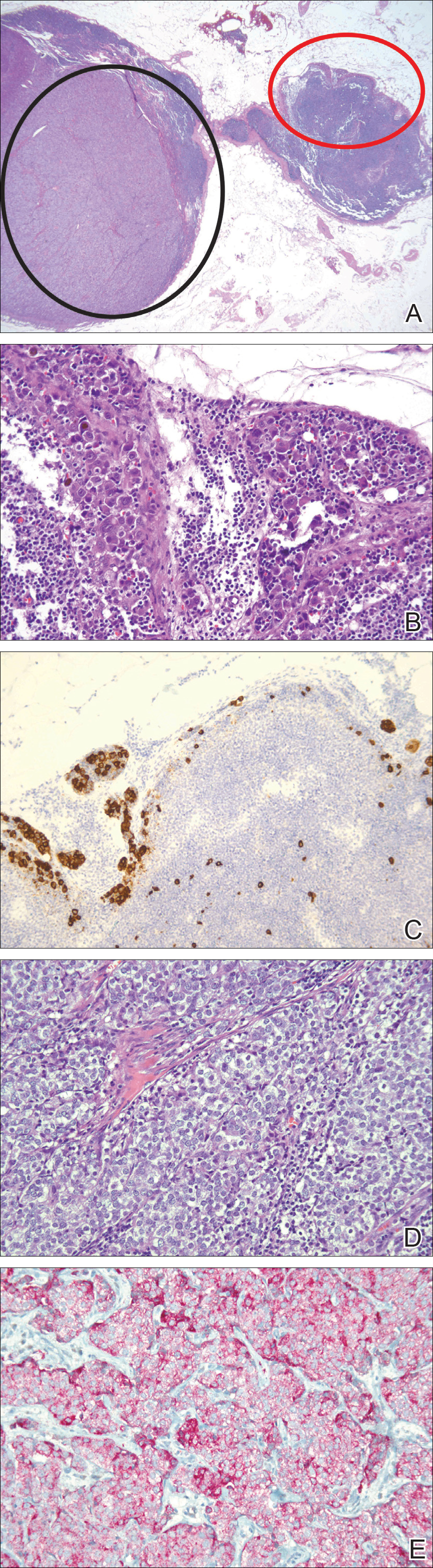

On re-admission, the patient was again given intravenous methylprednisolone and experienced interval improvement in the frequency of diarrhea. A gastroenterology expert was consulted, and the patient underwent a flexible sigmoidoscopy that demonstrated findings of diffuse and severe inflammation and biopsies were obtained (Figure 1). After several days of continued symptoms, the patient received infliximab 5 mg/kg for treatment of her adverse autoimmune reaction. After administration, the patient noted improvement in the frequency and volume of diarrhea, however, her symptoms still persisted.

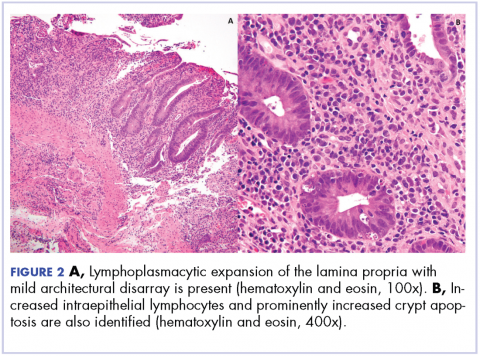

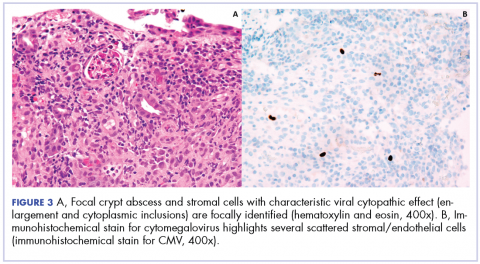

Biopsy results subsequently revealed findings compatible with ipilimumab-induced colitis, and immunohistochemical staining demonstrated positivity for cytomegalovirus (CMV). Specifically, histologic examination showed lymphoplasmacytic expansion of the lamina propria, some architectural distortion, and increased crypt apoptosis. Scattered cryptitis and crypt abscesses were also noted, as were rare stromal and endothelial cells with characteristic CMV inclusions (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Serum CMV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was also positive at 652,000 IU/mL (lower limit of detection 100 IU/mL). Induction dosing of ganciclovir (5 mg/kg IV Q12h) was initiated. The combined treatment with intravenous methylprednisone and ganciclovir led to an improvement in diarrhea frequency and resolution of blood in the stool. She was transitioned to oral prednisone, but it resulted in redevelopment of grade 3 diarrhea. The patient was therefore resumed on and discharged on daily intravenous methylprednisolone.

After discharge, the patient was started on budesonide 9 mg daily. Her serum CMV PCR level reduced and she was transitioned to oral valgancyclovir (900 mg daily) for maintenance. Another unsuccessful attempt was made to switch her to oral prednisone.

About 14 weeks after the initial ipilimumab dosing, the patient underwent another flexible sigmoidoscopy that again demonstrated severe colitis from the rectum to sigmoid colon. Biopsies were negative for CMV. Patient was readmitted for recurrence of diarrhea the following week. Treatment with IV methylprednisone (1mg/kg BID) and infliximab (5 mg/kg) again led to an improvement of symptoms. She was again discharged on IV methylprednisone (1 mg/kg BID) with a taper.

In the 15th week after her initial ipilimumab dose, the patient presented with a perforated bowel, requiring a subtotal colectomy and end ileostomy. She continued on a slow taper of oral prednisone (50 mg daily and decrease by 10 mg every 5 days).

At her last documented follow-up, 8 months after her first ipilimumab dose, she was having normal output from her ileostomy. She developed secondary adrenal insufficiency because of the long-term steroids and continued to take prednisone 5 mg daily.

Discussion

Diarrhea and colitis are common irAEs attributable to checkpoint-inhibitor therapy used for the treatment of melanoma. This case of ipilimumab-induced colitis refractory to high-dose oral steroids demonstrates the risks associated with management of anti-CTLA-4 induced colitis. In particular, the high-dose corticosteroids required to treat the autoimmune component of this patient’s colitis increased her susceptibility to CMV reactivation.

The diagnosis of colitis secondary to ipilimumab is made primarily in the appropriate clinical setting, and typically onsets during the induction period (within 12 weeks of initial dosing) and most resolve within 6-8 weeks.6 Histopathologically, there is lymphoplasmacytic expansion of lamina propria, increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, and increased epithelial apoptosis of crypts. One can also see acute cryptitis and crypt abscesses. Reactive epithelial changes with mucin depletion are also often seen in epithelial cells.

Findings from immunohistochemical studies have shown the increased intraepithelial lymphocytes to be predominantly CD8-positive T cells, while the lamina propria contains an increase in the mixture of CD4- and CD8-positive T cells. In addition, small intestinal samples show villous blunting. There is an absence of significant architectural distortion and well-developed basal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates characteristic of chronic mucosal injury, such as idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease.7 Granulomas are also absent in most series, though they have been reported in some cases.8 The features are similar to those seen in autoimmune enteropathy, but goblet and endocrine cells remain preserved. Graft-versus-host disease has similar histologic features, however, the clinical setting usually makes the distinction between these obvious.

Current treatment algorithms for ipilimumab-related diarrhea, begin with immediate treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone (125 mg once). This is followed with oral prednisone at a dose of 1-2 mg/kg tapered over 4 to 8 weeks.4 In patients with persistent symptoms despite adequate doses of corticosteroids, infliximab (5 mg/kg every 2 weeks) is recommended until the resolution of symptoms, and a longer taper of prednisone is often necessary.

Institution of high-dose corticosteroids to treat grade 3 or 4 irAEs can increase the risk for infection, including opportunistic infections. One retrospective review of patients administered checkpoint inhibitors at a single institution revealed that 7.3% of 740 patients developed a severe infection that lead to hospitalization or treatment with intravenous antibiotics.9 In that patient cohort, only 0.6% had a serious infection secondary to a viral etiology, and 1 patient developed CMV enterocolitis. Most patients who developed an infection in this cohort had received corticosteroids (46/54 patients, 85%) and/or infliximab (13/54 patients, 24%).9

CMV is a member of the Herpesviridae family. After a primary infection, which can often go unrecognized in an immunocompetent host, CMV can persist in a latent state.10 In a study by Bate and colleagues, the age-adjusted seropositivity of CMV was found to be 50.4%.11 Based on those results, immunosuppression in a patient who has previously been infected with CMV can lead to a risk of reactivation or even reinfection. In the era of checkpoint-inhibitor therapy, reactivation of CMV has been described previously in a case of CMV hepatitis and a report of CMV colitis.12,13 Immunosuppression, such as that caused by corticosteroids, is a risk factor for CMV infection.14 Colitis caused by CMV usually presents with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody diarrhea.15 In suspected cases of CMV colitis, endoscopy should be pursued with biopsy for tissue examination. A tissue diagnosis is required for CMV colitis because serum PCR can be negative in isolated cases of gastrointestinal CMV infection.15

Conclusion

Despite appropriate treatment with ganciclovir and the noted response in the patient’s serum CMV PCR, symptom exacerbation was observed with the transition to oral prednisone. The requirement for intravenous corticosteroids in the present case demonstrates the prolonged effects exerted by irAEs secondary to checkpoint-inhibitor therapy. Those effects are attributable to the design of the antibody – ipilimumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody and has a plasma half-life of about 15 days.1,4

By the identification of CMV histopathologically, this case, along with the case presented by Lankes and colleagues,13 illustrates the importance of considering CMV colitis in patients who are being treated with ipilimumab and who develop persistent or worsening diarrhea after initial treatment with high-dose steroids.

Early recognition of possible coexistent CMV colitis in patients with a history of treatment with ipilimumab can have important clinical consequences. It can lead to quicker implementation of proper antiviral therapy and minimization of immune suppression to levels required to maintain control of the patient’s symptoms.

1. Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711-723.

2. Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1845-1855.

3. Glassman PM, Balthasar JP. Mechanistic considerations for the use of monoclonal antibodies for cancer therapy. Cancer Biol Med. 2014;11(1):20-33.

4. Weber JS, Kahler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2691-2697.

5. Fecher LA, Agarwala SS, Hodi FS, Weber JS. Ipilimumab and its toxicities: a multidisciplinary approach. Oncologist. 2013;18(6):733-743.

6. Weber JS, Dummer R, de Pril V, Lebbe C, Hodi FS, Investigators MDX. Patterns of onset and resolution of immune-related adverse events of special interest with ipilimumab: detailed safety analysis from a phase 3 trial in patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer. 2013;119(9):1675-1682.

7. Oble DA, Mino-Kenudson M, Goldsmith J, et al. Alpha-CTLA-4 mAb-associated panenteritis: a histologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(8):1130-1137.

8. Beck KE, Blansfield JA, Tran KQ, et al. Enterocolitis in patients with cancer after antibody blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(15):2283-2289.

9. Del Castillo M, Romero FA, Arguello E, Kyi C, Postow MA, Redelman-Sidi G. The spectrum of serious infections among patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade for the treatment of melanoma. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(11):1490-1493.

10. Pillet S, Pozzetto B, Roblin X. Cytomegalovirus and ulcerative colitis: place of antiviral therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(6):2030-2045.

11. Bate SL, Dollard SC, Cannon MJ. Cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in the United States: the national health and nutrition examination surveys, 1988-2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(11):1439-1447.

12. Uslu U, Agaimy A, Hundorfean G, Harrer T, Schuler G, Heinzerling L. autoimmune colitis and subsequent CMV-induced hepatitis after treatment with ipilimumab. J Immunother. 2015;38(5):212-215.

13. Lankes K, Hundorfean G, Harrer T, et al. Anti-TNF-refractory colitis after checkpoint inhibitor therapy: possible role of CMV-mediated immunopathogenesis. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(6):e1128611.

14. Ko JH, Peck KR, Lee WJ, et al. Clinical presentation and risk factors for cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(6):e20-26.

15. You DM, Johnson MD. Cytomegalovirus infection and the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14(4):334-342.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, including anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (anti-CTLA4) and anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (anti-PD-1) antibodies, have demonstrated clinical and survival benefits in a variety of malignancies, which has led to an expansion in their role in oncology. In melanoma, the anti-CTLA-4 antibody, ipilimumab, has demonstrated a survival benefit in patients with advanced metastatic melanoma and in patients with resectable disease with lymph node involvement.1,2

Ipilimumab exerts its effect by binding CTLA-4 on conventional and regulatory T cells, thus blocking inhibitory signals on T cells, which leads to an antitumor response.3 The increased immune response counteracts the immune-evading mechanisms of the tumor. With increased use of these agents, immune-related adverse events (irAEs) have become more prevalent. The most common irAEs secondary to ipilimumab are skin rash, colitis/diarrhea, hepatitis, pneumonitis, and various endocrinopathies.4 In a phase 3 trial of adjuvant ipilimumab in patients with resected stage III melanoma, grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred in 54.1% of participants in the ipilimumab arm, the most common being diarrhea and colitis (9.8% and 6.8%, respectively).2Recognition and management of irAEs has led to the implementation of treatment guidelines.4,5 Management of irAEs includes checkpoint inhibitor discontinuation and reversal of the immune response by institution of immunosuppression with corticosteroids.

Case presentation and summary

A 40-year-old white woman with stage IIIB BRAF V600E-positive melanoma presented with diarrhea refractory to high-dose prednisone (1 mg/kg BID). She had recently undergone wide local excision and sentinel node biopsy and received her inaugural dose of ipilimumab (10 mg/kg).

The patient first presented with loose, watery stools that had begun 8 days after she had received her first dose of adjuvant ipilimumab. She was admitted to the hospital, and intravenous methylprednisolone was initiated along with empiric ciprofloxacin (400 mg, IVPB Q12h) and metronidazole (500 mg, IVPB Q8h) as infectious causes were concurrently ruled out. During this initial admission, the patient’s stool was negative for Clostridium difficile toxin, ova, and parasites, as well as enteric pathogens by culture. After infectious causes were excluded, she was diagnosed with ipilimumab-induced colitis. Antibiotics were discontinued, and the patient ultimately noted improvement in her symptoms. On hospital day 7, she was experiencing only 2 bowel movements a day and was discharged on 80 mg of prednisone twice daily.

After discharge the patient noted persistence of her symptoms. At her follow-up, 9 days after discharge, the patient noted continued symptoms of low-grade diarrhea. She failed a trial of steroid tapering due to exacerbation of her abdominal pain and frequency of diarrhea. Further investigation was negative for C. diff toxin and a computed-tomography scan was consistent with continuing colitis. The patient’s symptoms continued to worsen, with recurrence of grade 3 diarrhea, and she was ultimately readmitted 17 days after her earlier discharge (36 days after her first ipilimumab dosing).

On re-admission, the patient was again given intravenous methylprednisolone and experienced interval improvement in the frequency of diarrhea. A gastroenterology expert was consulted, and the patient underwent a flexible sigmoidoscopy that demonstrated findings of diffuse and severe inflammation and biopsies were obtained (Figure 1). After several days of continued symptoms, the patient received infliximab 5 mg/kg for treatment of her adverse autoimmune reaction. After administration, the patient noted improvement in the frequency and volume of diarrhea, however, her symptoms still persisted.

Biopsy results subsequently revealed findings compatible with ipilimumab-induced colitis, and immunohistochemical staining demonstrated positivity for cytomegalovirus (CMV). Specifically, histologic examination showed lymphoplasmacytic expansion of the lamina propria, some architectural distortion, and increased crypt apoptosis. Scattered cryptitis and crypt abscesses were also noted, as were rare stromal and endothelial cells with characteristic CMV inclusions (Figure 2 and Figure 3).