User login

Whom to screen for anxiety and depression: Updated USPSTF recommendations

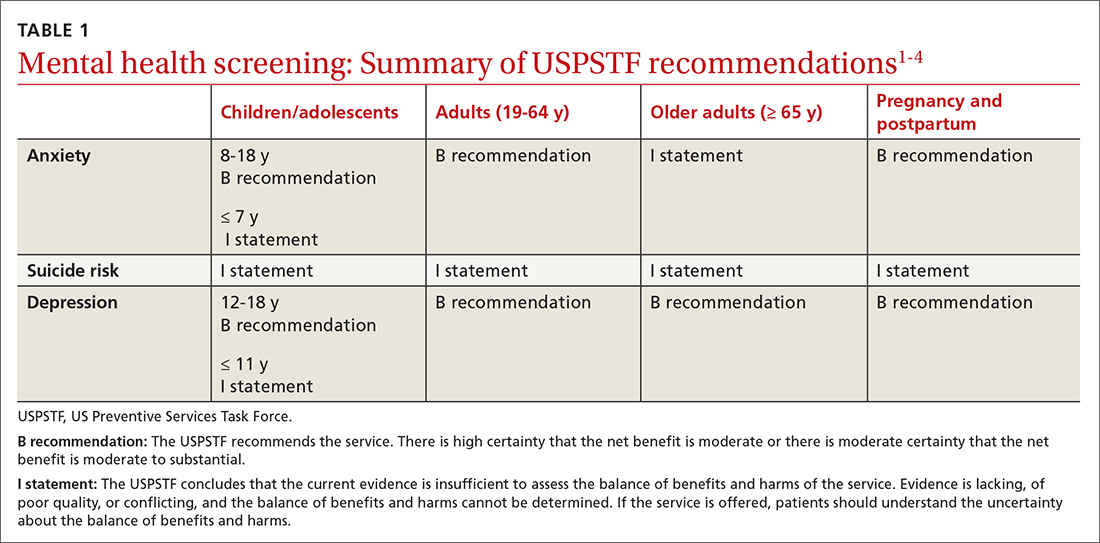

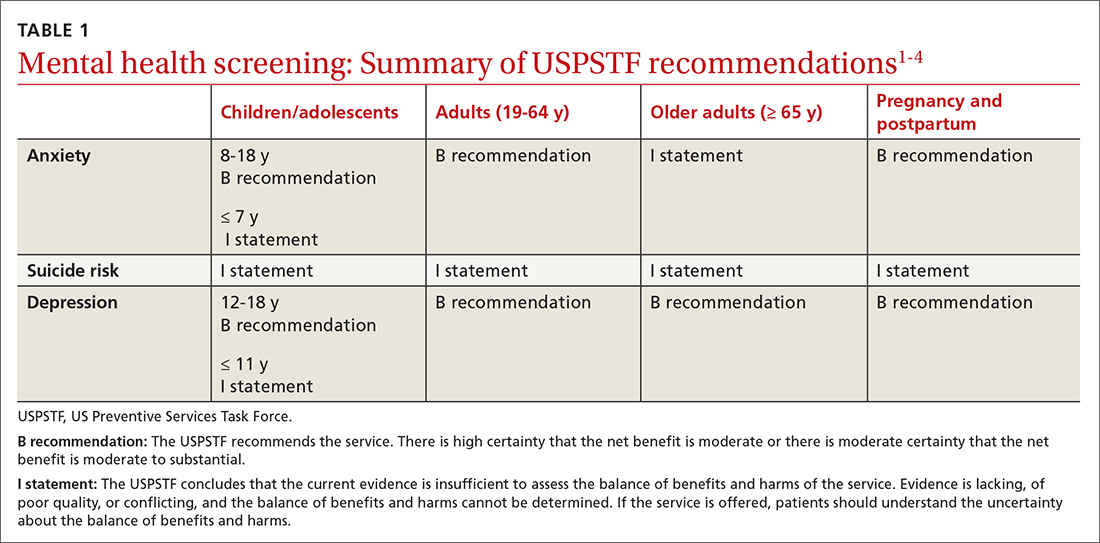

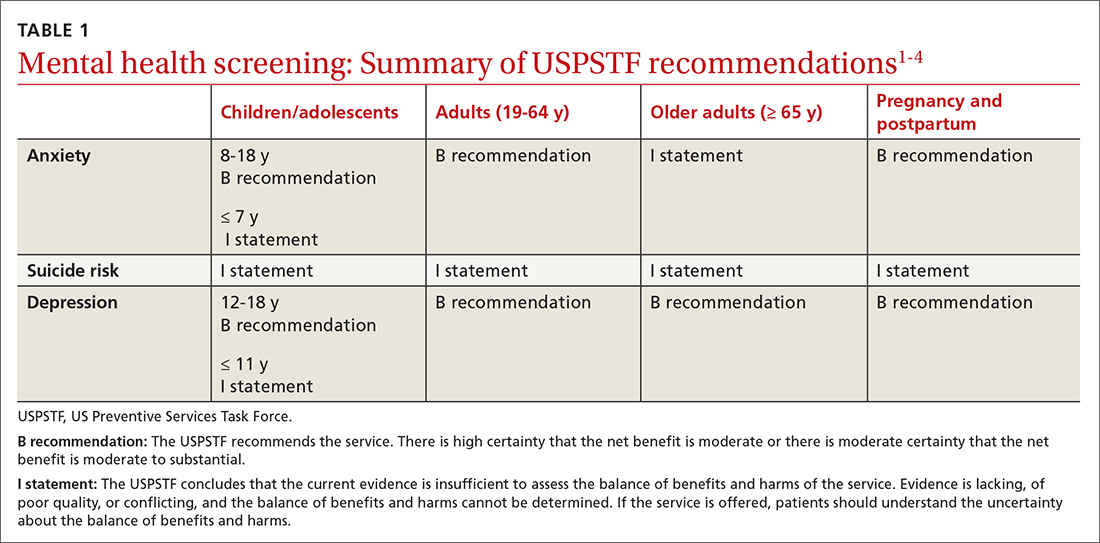

In September 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released 2 sets of draft recommendations on screening for 3 mental health conditions in adults: anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.1,2 These draft recommendations are summarized in TABLE 11-4 along with finalized recommendations on the same topics for children and adolescents, published in October 2022.3,4

The recommendations on depression and suicide risk screening in adults are updates of previous recommendations (2016 for depression and 2014 for suicide risk) with no major changes. Screening for anxiety is a topic addressed for the first time this year for adults and for children and adolescents.1,3

The recommendations are fairly consistent between age groups. A “B” recommendation supports screening for major depression in all patients starting at age 12 years, including during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (See TABLE 1 for grade definitions.) For all age groups, evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for suicide risk. A “B” recommendation was also assigned to screening for anxiety in those ages 8 to 64 years. The USPSTF believes the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for anxiety among adults ≥ 65 years of age.

The anxiety disorders common to both children and adults included in the USPSTF recommendations are generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, selective mutism, and anxiety type not specified. For adults, the USPSTF also includes substance/medication-induced anxiety and anxiety due to other medical conditions.

Adults with anxiety often present with generalized complaints such as sleep disturbance, pain, and other somatic disorders that can remain undiagnosed for years. The USPSTF cites a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders of 26.4% for men and 40.4% for women, although the data used are 10 years old.5 The cited rate of generalized anxiety in pregnancy is 8.5% to 10.5%, and in the postpartum period, 4.4% to 10.8%.6

The data on direct benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in adults through age 64 are sparse. Nevertheless, the USPSTF deemed that screening tests for anxiety have adequate accuracy and that psychological interventions for anxiety result in moderate reduction of anxiety symptoms. Pharmacologic interventions produce a small benefit, although there is a lack of evidence for pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum women. There is even less evidence of benefit for treatment in adults ≥ 65 years of age.1

How anxiety screening tests compare

Screening tests for anxiety in adults reviewed by the USPSTF included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale.1 The most studied tools are the GAD-2 and GAD-7.

Continue to: The sensitivity and specificity...

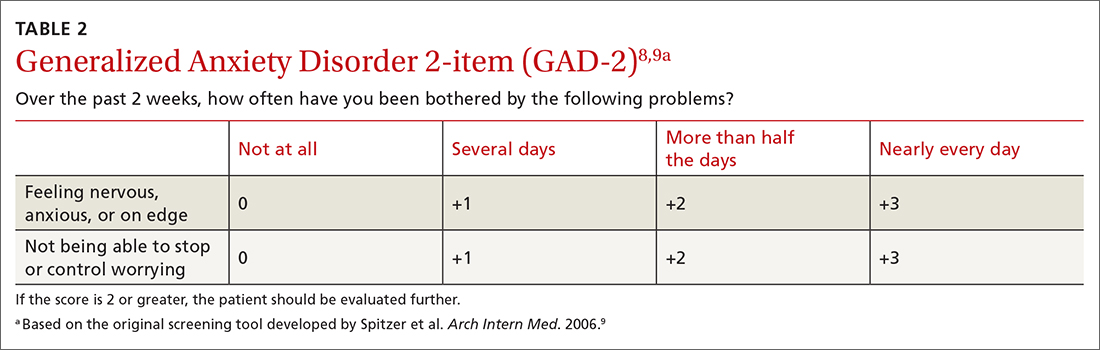

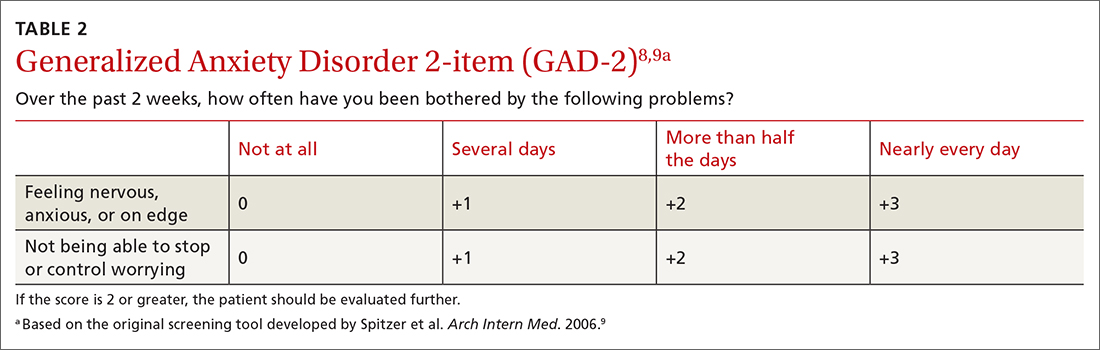

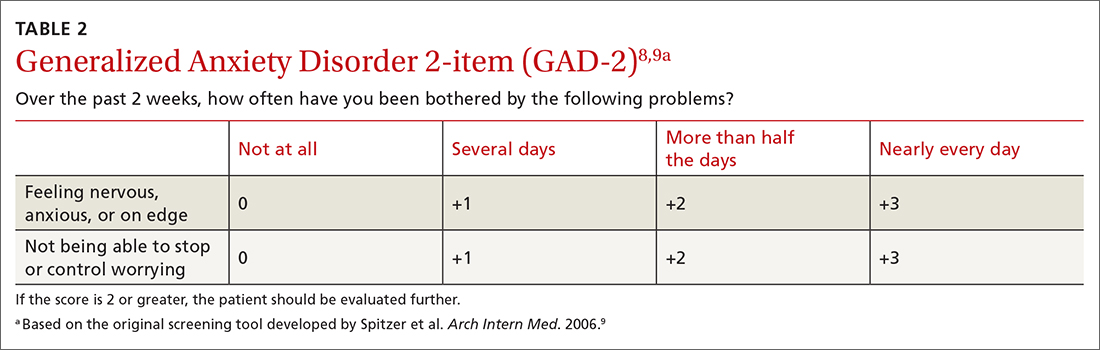

The sensitivity and specificity of each test depends on the cutoff used. With the GAD-2, a cutoff of 2 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 68% for detecting generalized anxiety.7 A cutoff of 3 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 86%.7 The GAD-7, using 10 as a cutoff, achieves a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 89%.7 Given the similar performance of the 2 options, the GAD-2 (TABLE 28,9) is probably preferable for use in primary care because of its ease of administration.

The tests evaluated by the USPSTF for anxiety screening in children and adolescents ≥ 8 years of age included the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (PHQ-A).3 These tools ask more questions than the adult screening tools do: 41 for the SCARED and 13 for the PHQ-A. The sensitivity of SCARED for generalized anxiety disorder was 64% and the specificity was 63%.10 The sensitivity of the PHQ-A was 50% and the specificity was 98%.10

Various versions of all of these screening tools can be easily located on the internet. Search for them using the acronyms.

Screening for major depression

The depression screening tests the USPSTF examined were various versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the EPDS in postpartum and pregnant persons.7

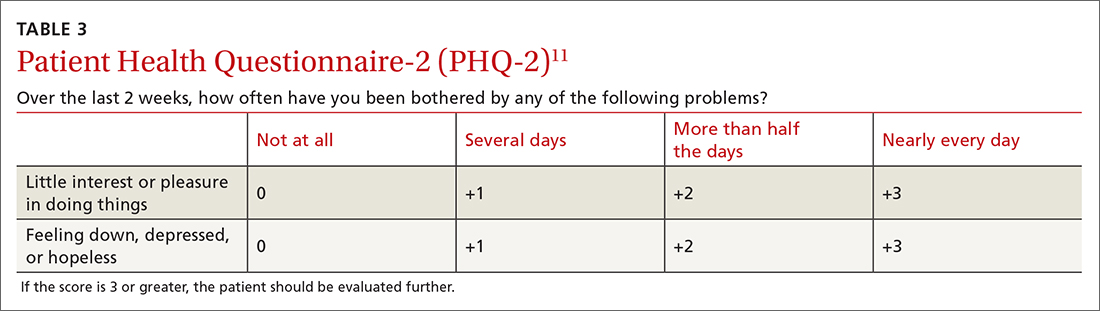

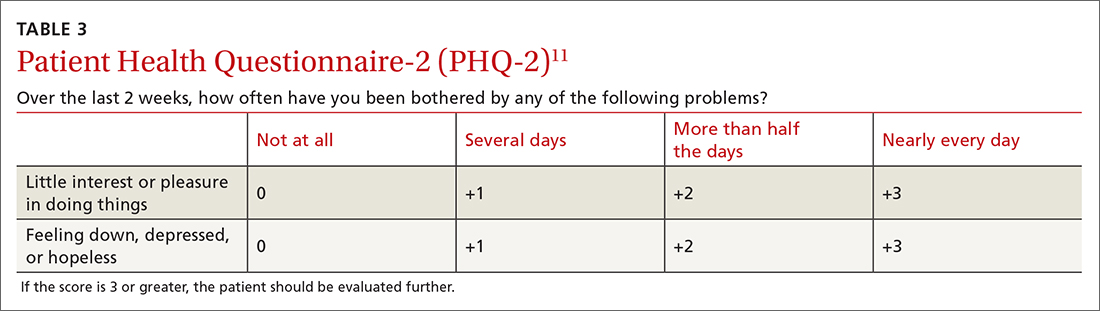

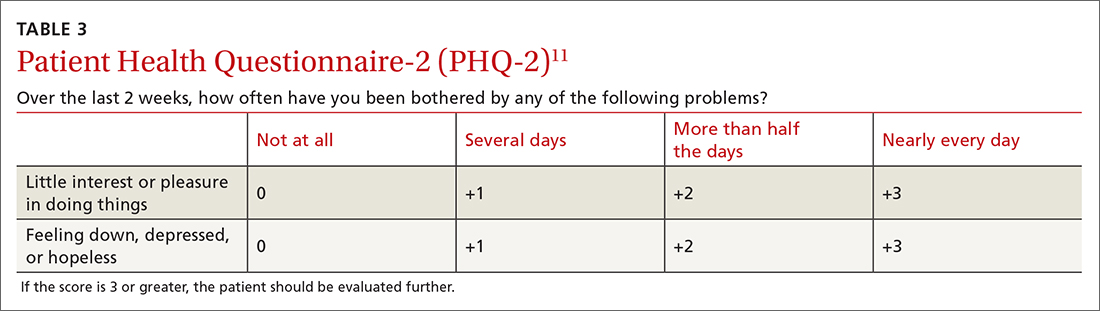

A 2-question version of the PHQ was found to have a sensitivity of 91% with a specificity of 67%. The 9-question PHQ was found to have a similar sensitivity (88%) but better specificity (85%).7TABLE 311 lists the 2 questions in the PHQ-2 and explains how to score the results.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly studied screening tool for adolescents is the PHQ-A. Its sensitivity is 73% and specificity is 94%.12

The GAD-2 and PHQ-2 have the same possible answers and scores and can be combined into a 4-question screening tool to assess for anxiety and depression. If an initial screen for anxiety or depression (or both) is positive, further diagnostic testing and follow-up are needed.

Frequency of screening

The USPSTF recognized that limited information on the frequency of screening for both anxiety and depression does not support any recommendation on this matter. It suggested screening everyone once and then basing the need for subsequent screening tests on clinical judgment after considering risk factors and life events, with periodic rescreening of those at high risk. Finally, USPSTF recognized the many challenges to implementing screening tests for mental health conditions in primary care practice, but offered little practical advice on how to do this.

Suicide risk screening

As for the evidence on benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in all age groups, the USPSTF still regards it as insufficient to make a recommendation. The lack of evidence applies to all aspects of screening, including the accuracy of the various screening tools and the potential benefits and harms of preventive interventions.2,7

Next steps

The recommendations on screening for depression, suicide risk, and anxiety in adults have been published as a draft, and the public comment period will be over by the time of this publication. The USPSTF generally takes 6 to 9 months to consider all the public comments and to publish final recommendations. The final recommendations on these topics for children and adolescents have been published since drafts were made available last April. There were no major changes between the draft and final versions.

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in adults. Draft recommendation statement. Published September 20, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening

2. USPSTF. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Updated September 14, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-update-summary/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults

3. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

4. USPSTF. Depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169-184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, et al. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: assessment and treatment. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:762-770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150

7. O’Connor E, Henninger M, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 22, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/dpG5pjV5yCew8fXvctFJNK

8. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, et al. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020;12:e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

10. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1445-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16303

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284‐1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

12. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1543-1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16310

In September 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released 2 sets of draft recommendations on screening for 3 mental health conditions in adults: anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.1,2 These draft recommendations are summarized in TABLE 11-4 along with finalized recommendations on the same topics for children and adolescents, published in October 2022.3,4

The recommendations on depression and suicide risk screening in adults are updates of previous recommendations (2016 for depression and 2014 for suicide risk) with no major changes. Screening for anxiety is a topic addressed for the first time this year for adults and for children and adolescents.1,3

The recommendations are fairly consistent between age groups. A “B” recommendation supports screening for major depression in all patients starting at age 12 years, including during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (See TABLE 1 for grade definitions.) For all age groups, evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for suicide risk. A “B” recommendation was also assigned to screening for anxiety in those ages 8 to 64 years. The USPSTF believes the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for anxiety among adults ≥ 65 years of age.

The anxiety disorders common to both children and adults included in the USPSTF recommendations are generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, selective mutism, and anxiety type not specified. For adults, the USPSTF also includes substance/medication-induced anxiety and anxiety due to other medical conditions.

Adults with anxiety often present with generalized complaints such as sleep disturbance, pain, and other somatic disorders that can remain undiagnosed for years. The USPSTF cites a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders of 26.4% for men and 40.4% for women, although the data used are 10 years old.5 The cited rate of generalized anxiety in pregnancy is 8.5% to 10.5%, and in the postpartum period, 4.4% to 10.8%.6

The data on direct benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in adults through age 64 are sparse. Nevertheless, the USPSTF deemed that screening tests for anxiety have adequate accuracy and that psychological interventions for anxiety result in moderate reduction of anxiety symptoms. Pharmacologic interventions produce a small benefit, although there is a lack of evidence for pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum women. There is even less evidence of benefit for treatment in adults ≥ 65 years of age.1

How anxiety screening tests compare

Screening tests for anxiety in adults reviewed by the USPSTF included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale.1 The most studied tools are the GAD-2 and GAD-7.

Continue to: The sensitivity and specificity...

The sensitivity and specificity of each test depends on the cutoff used. With the GAD-2, a cutoff of 2 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 68% for detecting generalized anxiety.7 A cutoff of 3 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 86%.7 The GAD-7, using 10 as a cutoff, achieves a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 89%.7 Given the similar performance of the 2 options, the GAD-2 (TABLE 28,9) is probably preferable for use in primary care because of its ease of administration.

The tests evaluated by the USPSTF for anxiety screening in children and adolescents ≥ 8 years of age included the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (PHQ-A).3 These tools ask more questions than the adult screening tools do: 41 for the SCARED and 13 for the PHQ-A. The sensitivity of SCARED for generalized anxiety disorder was 64% and the specificity was 63%.10 The sensitivity of the PHQ-A was 50% and the specificity was 98%.10

Various versions of all of these screening tools can be easily located on the internet. Search for them using the acronyms.

Screening for major depression

The depression screening tests the USPSTF examined were various versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the EPDS in postpartum and pregnant persons.7

A 2-question version of the PHQ was found to have a sensitivity of 91% with a specificity of 67%. The 9-question PHQ was found to have a similar sensitivity (88%) but better specificity (85%).7TABLE 311 lists the 2 questions in the PHQ-2 and explains how to score the results.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly studied screening tool for adolescents is the PHQ-A. Its sensitivity is 73% and specificity is 94%.12

The GAD-2 and PHQ-2 have the same possible answers and scores and can be combined into a 4-question screening tool to assess for anxiety and depression. If an initial screen for anxiety or depression (or both) is positive, further diagnostic testing and follow-up are needed.

Frequency of screening

The USPSTF recognized that limited information on the frequency of screening for both anxiety and depression does not support any recommendation on this matter. It suggested screening everyone once and then basing the need for subsequent screening tests on clinical judgment after considering risk factors and life events, with periodic rescreening of those at high risk. Finally, USPSTF recognized the many challenges to implementing screening tests for mental health conditions in primary care practice, but offered little practical advice on how to do this.

Suicide risk screening

As for the evidence on benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in all age groups, the USPSTF still regards it as insufficient to make a recommendation. The lack of evidence applies to all aspects of screening, including the accuracy of the various screening tools and the potential benefits and harms of preventive interventions.2,7

Next steps

The recommendations on screening for depression, suicide risk, and anxiety in adults have been published as a draft, and the public comment period will be over by the time of this publication. The USPSTF generally takes 6 to 9 months to consider all the public comments and to publish final recommendations. The final recommendations on these topics for children and adolescents have been published since drafts were made available last April. There were no major changes between the draft and final versions.

In September 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released 2 sets of draft recommendations on screening for 3 mental health conditions in adults: anxiety, depression, and suicide risk.1,2 These draft recommendations are summarized in TABLE 11-4 along with finalized recommendations on the same topics for children and adolescents, published in October 2022.3,4

The recommendations on depression and suicide risk screening in adults are updates of previous recommendations (2016 for depression and 2014 for suicide risk) with no major changes. Screening for anxiety is a topic addressed for the first time this year for adults and for children and adolescents.1,3

The recommendations are fairly consistent between age groups. A “B” recommendation supports screening for major depression in all patients starting at age 12 years, including during pregnancy and the postpartum period. (See TABLE 1 for grade definitions.) For all age groups, evidence was insufficient to recommend screening for suicide risk. A “B” recommendation was also assigned to screening for anxiety in those ages 8 to 64 years. The USPSTF believes the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation on screening for anxiety among adults ≥ 65 years of age.

The anxiety disorders common to both children and adults included in the USPSTF recommendations are generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, phobias, selective mutism, and anxiety type not specified. For adults, the USPSTF also includes substance/medication-induced anxiety and anxiety due to other medical conditions.

Adults with anxiety often present with generalized complaints such as sleep disturbance, pain, and other somatic disorders that can remain undiagnosed for years. The USPSTF cites a lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders of 26.4% for men and 40.4% for women, although the data used are 10 years old.5 The cited rate of generalized anxiety in pregnancy is 8.5% to 10.5%, and in the postpartum period, 4.4% to 10.8%.6

The data on direct benefits and harms of screening for anxiety in adults through age 64 are sparse. Nevertheless, the USPSTF deemed that screening tests for anxiety have adequate accuracy and that psychological interventions for anxiety result in moderate reduction of anxiety symptoms. Pharmacologic interventions produce a small benefit, although there is a lack of evidence for pharmacotherapy in pregnant and postpartum women. There is even less evidence of benefit for treatment in adults ≥ 65 years of age.1

How anxiety screening tests compare

Screening tests for anxiety in adults reviewed by the USPSTF included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) anxiety subscale.1 The most studied tools are the GAD-2 and GAD-7.

Continue to: The sensitivity and specificity...

The sensitivity and specificity of each test depends on the cutoff used. With the GAD-2, a cutoff of 2 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 68% for detecting generalized anxiety.7 A cutoff of 3 or more resulted in a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 86%.7 The GAD-7, using 10 as a cutoff, achieves a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 89%.7 Given the similar performance of the 2 options, the GAD-2 (TABLE 28,9) is probably preferable for use in primary care because of its ease of administration.

The tests evaluated by the USPSTF for anxiety screening in children and adolescents ≥ 8 years of age included the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and the Patient Health Questionnaire–Adolescent (PHQ-A).3 These tools ask more questions than the adult screening tools do: 41 for the SCARED and 13 for the PHQ-A. The sensitivity of SCARED for generalized anxiety disorder was 64% and the specificity was 63%.10 The sensitivity of the PHQ-A was 50% and the specificity was 98%.10

Various versions of all of these screening tools can be easily located on the internet. Search for them using the acronyms.

Screening for major depression

The depression screening tests the USPSTF examined were various versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in older adults, and the EPDS in postpartum and pregnant persons.7

A 2-question version of the PHQ was found to have a sensitivity of 91% with a specificity of 67%. The 9-question PHQ was found to have a similar sensitivity (88%) but better specificity (85%).7TABLE 311 lists the 2 questions in the PHQ-2 and explains how to score the results.

Continue to: The most commonly...

The most commonly studied screening tool for adolescents is the PHQ-A. Its sensitivity is 73% and specificity is 94%.12

The GAD-2 and PHQ-2 have the same possible answers and scores and can be combined into a 4-question screening tool to assess for anxiety and depression. If an initial screen for anxiety or depression (or both) is positive, further diagnostic testing and follow-up are needed.

Frequency of screening

The USPSTF recognized that limited information on the frequency of screening for both anxiety and depression does not support any recommendation on this matter. It suggested screening everyone once and then basing the need for subsequent screening tests on clinical judgment after considering risk factors and life events, with periodic rescreening of those at high risk. Finally, USPSTF recognized the many challenges to implementing screening tests for mental health conditions in primary care practice, but offered little practical advice on how to do this.

Suicide risk screening

As for the evidence on benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in all age groups, the USPSTF still regards it as insufficient to make a recommendation. The lack of evidence applies to all aspects of screening, including the accuracy of the various screening tools and the potential benefits and harms of preventive interventions.2,7

Next steps

The recommendations on screening for depression, suicide risk, and anxiety in adults have been published as a draft, and the public comment period will be over by the time of this publication. The USPSTF generally takes 6 to 9 months to consider all the public comments and to publish final recommendations. The final recommendations on these topics for children and adolescents have been published since drafts were made available last April. There were no major changes between the draft and final versions.

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in adults. Draft recommendation statement. Published September 20, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening

2. USPSTF. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Updated September 14, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-update-summary/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults

3. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

4. USPSTF. Depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169-184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, et al. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: assessment and treatment. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:762-770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150

7. O’Connor E, Henninger M, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 22, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/dpG5pjV5yCew8fXvctFJNK

8. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, et al. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020;12:e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

10. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1445-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16303

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284‐1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

12. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1543-1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16310

1. USPSTF. Screening for anxiety in adults. Draft recommendation statement. Published September 20, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/anxiety-adults-screening

2. USPSTF. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults. Updated September 14, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-update-summary/screening-depression-suicide-risk-adults

3. USPSTF. Anxiety in children and adolescents: screening. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents

4. USPSTF. Depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published October 11, 2022. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-depression-suicide-risk-children-adolescents

5. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21:169-184. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1359

6. Misri S, Abizadeh J, Sanders S, et al. Perinatal generalized anxiety disorder: assessment and treatment. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:762-770. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5150

7. O’Connor E, Henninger M, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for depression, anxiety, and suicide risk in adults: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Accessed November 22, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/home/getfilebytoken/dpG5pjV5yCew8fXvctFJNK

8. Sapra A, Bhandari P, Sharma S, et al. Using Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2) and GAD-7 in a primary care setting. Cureus. 2020;12:e8224. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8224

9. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

10. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1445-1455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16303

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284‐1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

12. Viswanathan M, Wallace IF, Middleton JC, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328:1543-1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16310

Behavioral treatment tied to lower medical, pharmacy costs

Results of a large retrospective study showed that patients newly diagnosed with a BHC who receive OPBHT following diagnosis incur lower medical and pharmacy costs over roughly the next 1 to 2 years, compared with peers who don’t receive OPBHT.

“Our findings suggest that promoting OPBHT as part of a population health strategy is associated with improved overall medical spending, particularly among adults,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Common, undertreated

Nearly a quarter of adults in the United States have a BHC, and they incur greater medical costs than those without a BHC. However, diagnosis of a BHC is often delayed, and most affected individuals receive little to no treatment.

In their cost analysis, Johanna Bellon, PhD, and colleagues with Evernorth Health, St. Louis, analyzed commercial insurance claims data for 203,401 U.S. individuals newly diagnosed with one or more BHCs between 2017 and 2018.

About half of participants had depression and/or anxiety, 11% had substance use or alcohol use disorder, and 6% had a higher-acuity diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, eating disorder, psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

About 1 in 5 (22%) had at least one chronic medical condition along with their BHC.

The researchers found that having at least one OPBHT visit was associated with lower medical and pharmacy costs during 15- and 27-month follow-up periods.

Over 15 months, the adjusted mean per member per month (PMPM) medical/pharmacy cost was $686 with no OPBHT visit, compared with $571 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Over 27 months, the adjusted mean PMPM was $464 with no OPBHT, versus $391 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Dose-response effect

In addition, there was a “dose-response” relationship between OPBHT and medical/pharmacy costs, such that estimated cost savings were significantly lower in the treated versus the untreated groups at almost every level of treatment.

“Our findings were also largely age independent, especially over 15 months, suggesting that OPBHT has favorable effects among children, young adults, and adults,” the researchers report.

“This is promising given that disease etiology and progression, treatment paradigms, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and overall medical and pharmacy costs differ among the three groups,” they say.

Notably, the dataset largely encompassed in-person OPBHT, because the study period preceded the transition into virtual care that occurred in 2020.

However, overall use of OPBHT was low – older adults, adults with lower income, individuals with comorbid medical conditions, and persons of racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to receive OPBHT, they found.

“These findings support the cost-effectiveness of practitioner- and insurance-based interventions to increase OPBHT utilization, which is a critical resource as new BHC diagnoses continue to increase,” the researchers say.

“Future research should validate these findings in other populations, including government-insured individuals, and explore data by chronic disease category, over longer time horizons, by type and quality of OPBHT, by type of medical spending, within subpopulations with BHCs, and including virtual and digital behavioral health services,” they suggest.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a large retrospective study showed that patients newly diagnosed with a BHC who receive OPBHT following diagnosis incur lower medical and pharmacy costs over roughly the next 1 to 2 years, compared with peers who don’t receive OPBHT.

“Our findings suggest that promoting OPBHT as part of a population health strategy is associated with improved overall medical spending, particularly among adults,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Common, undertreated

Nearly a quarter of adults in the United States have a BHC, and they incur greater medical costs than those without a BHC. However, diagnosis of a BHC is often delayed, and most affected individuals receive little to no treatment.

In their cost analysis, Johanna Bellon, PhD, and colleagues with Evernorth Health, St. Louis, analyzed commercial insurance claims data for 203,401 U.S. individuals newly diagnosed with one or more BHCs between 2017 and 2018.

About half of participants had depression and/or anxiety, 11% had substance use or alcohol use disorder, and 6% had a higher-acuity diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, eating disorder, psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

About 1 in 5 (22%) had at least one chronic medical condition along with their BHC.

The researchers found that having at least one OPBHT visit was associated with lower medical and pharmacy costs during 15- and 27-month follow-up periods.

Over 15 months, the adjusted mean per member per month (PMPM) medical/pharmacy cost was $686 with no OPBHT visit, compared with $571 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Over 27 months, the adjusted mean PMPM was $464 with no OPBHT, versus $391 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Dose-response effect

In addition, there was a “dose-response” relationship between OPBHT and medical/pharmacy costs, such that estimated cost savings were significantly lower in the treated versus the untreated groups at almost every level of treatment.

“Our findings were also largely age independent, especially over 15 months, suggesting that OPBHT has favorable effects among children, young adults, and adults,” the researchers report.

“This is promising given that disease etiology and progression, treatment paradigms, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and overall medical and pharmacy costs differ among the three groups,” they say.

Notably, the dataset largely encompassed in-person OPBHT, because the study period preceded the transition into virtual care that occurred in 2020.

However, overall use of OPBHT was low – older adults, adults with lower income, individuals with comorbid medical conditions, and persons of racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to receive OPBHT, they found.

“These findings support the cost-effectiveness of practitioner- and insurance-based interventions to increase OPBHT utilization, which is a critical resource as new BHC diagnoses continue to increase,” the researchers say.

“Future research should validate these findings in other populations, including government-insured individuals, and explore data by chronic disease category, over longer time horizons, by type and quality of OPBHT, by type of medical spending, within subpopulations with BHCs, and including virtual and digital behavioral health services,” they suggest.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a large retrospective study showed that patients newly diagnosed with a BHC who receive OPBHT following diagnosis incur lower medical and pharmacy costs over roughly the next 1 to 2 years, compared with peers who don’t receive OPBHT.

“Our findings suggest that promoting OPBHT as part of a population health strategy is associated with improved overall medical spending, particularly among adults,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Common, undertreated

Nearly a quarter of adults in the United States have a BHC, and they incur greater medical costs than those without a BHC. However, diagnosis of a BHC is often delayed, and most affected individuals receive little to no treatment.

In their cost analysis, Johanna Bellon, PhD, and colleagues with Evernorth Health, St. Louis, analyzed commercial insurance claims data for 203,401 U.S. individuals newly diagnosed with one or more BHCs between 2017 and 2018.

About half of participants had depression and/or anxiety, 11% had substance use or alcohol use disorder, and 6% had a higher-acuity diagnosis, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, eating disorder, psychotic disorder, or autism spectrum disorder.

About 1 in 5 (22%) had at least one chronic medical condition along with their BHC.

The researchers found that having at least one OPBHT visit was associated with lower medical and pharmacy costs during 15- and 27-month follow-up periods.

Over 15 months, the adjusted mean per member per month (PMPM) medical/pharmacy cost was $686 with no OPBHT visit, compared with $571 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Over 27 months, the adjusted mean PMPM was $464 with no OPBHT, versus $391 with one or more OPBHT visits.

Dose-response effect

In addition, there was a “dose-response” relationship between OPBHT and medical/pharmacy costs, such that estimated cost savings were significantly lower in the treated versus the untreated groups at almost every level of treatment.

“Our findings were also largely age independent, especially over 15 months, suggesting that OPBHT has favorable effects among children, young adults, and adults,” the researchers report.

“This is promising given that disease etiology and progression, treatment paradigms, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and overall medical and pharmacy costs differ among the three groups,” they say.

Notably, the dataset largely encompassed in-person OPBHT, because the study period preceded the transition into virtual care that occurred in 2020.

However, overall use of OPBHT was low – older adults, adults with lower income, individuals with comorbid medical conditions, and persons of racial and ethnic minorities were less likely to receive OPBHT, they found.

“These findings support the cost-effectiveness of practitioner- and insurance-based interventions to increase OPBHT utilization, which is a critical resource as new BHC diagnoses continue to increase,” the researchers say.

“Future research should validate these findings in other populations, including government-insured individuals, and explore data by chronic disease category, over longer time horizons, by type and quality of OPBHT, by type of medical spending, within subpopulations with BHCs, and including virtual and digital behavioral health services,” they suggest.

The study had no specific funding. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Aerobic exercise augments PTSD therapy

Investigators randomly assigned individuals with PTSD to receive either exposure therapy with aerobic exercise or exposure therapy with passive stretching for 9 weeks. At 6 months post intervention, participants in the aerobic exercise group showed greater reductions in PTSD severity, compared with those in the stretching group.

“There is a critical need to improve outcomes for treating people with PTSD, and this finding points to one potentially cheap and ready-to-use strategy that all clinicians could employ with most patients,” lead author Richard Bryant, MPsych, PhD, DSc, director of the Traumatic Stress Clinic and Scientia Professor of Psychology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told this news organization.

The study was published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

Promoting BDNF

“Trauma-focused psychotherapy is the recommended treatment for PTSD, but up to half of patients do not respond to this treatment,” Dr. Bryant said.

“We know that brain-derived neurotrophic factors [BDNF] are critical for synaptic plasticity, which underpins the learning that occurs in therapy so that reminders of trauma are no longer fear-provoking,” he continued. “Preclinical animal and human research inform us that brief aerobic exercise can promote BDNF and new learning that inhibits fear responses.”

The researchers “hypothesized that brief exercise after exposure therapy to trauma memories – which is the key ingredient of trauma-focused psychotherapy – would lead to greater reductions in PTSD, relative to standard trauma-focused therapy,” he said.

To investigate the question, the researchers randomly assigned 130 adults with PTSD (mean age, 39 years; 61% female; 76% White) to receive nine 90-minute sessions of exposure therapy with either aerobic exercise or passive stretching (n = 65 in each group).

There were no differences at baseline in sociodemographic characteristics or psychopathology measures, although the mean age of the stretching group was slightly older than that of the aerobic group (40 years vs. 37 years, respectively), and there was a slightly higher proportion of women in the stretching group (68% vs. 54%).

Participants did not differ on weekly exercise either at baseline, immediately post treatment, or at 6-week follow-up.

PTSD severity (the primary outcome) was measured using the clinician-administered PTSD scale CAPS-2, with assessments conducted at baseline, 1 week post treatment, and 6 months post treatment.

The aerobic exercise regimen was tailored to each participant, based on an assessment of his/her aerobic target zone.

The exposure therapy sessions were identical for both groups. Following the exposure sessions, participants engaged in their respective exercises: Those in the passive stretching group engaged in 20 minutes of exercise, while those in the aerobic group participated in a total of 20 minutes of exercise, with 10 conducted at their personal aerobic target heart rate.

“This level of exercise was chosen because BDNF concentration in the serum is increased by two 3-minute bouts of aerobic exercise, and 10 minutes of aerobic exercise can facilitate extinction learning,” the authors explained.

The aerobic activity consisted of running on a stepper exercise platform while having cardiac activity recorded. A small portion (10%) of the therapy sessions were recorded and rated for treatment fidelity.

Change in PTSD was the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes consisting of changes in depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder, and posttraumatic cognitions.

Few barriers

The researchers found no significant differences in PTSD severity, as measured by CAPS-2 score, between treatment groups at 10 weeks – that is, immediately post treatment (mean difference, 7.0; 95% confidence interval, –2.3 to 16.4; P = .14).

However, significantly greater reductions in PTSD severity were found in the aerobic versus the stretching group at 6-month follow-up (mean difference, 12.1;95% CI, 2.4-21.8; P = .023), pointing to a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.1-1.1]).

Although there were no differences found at 6-month assessment between rates of PTSD diagnosis (25% of the aerobic vs 27% of the stretching group), more participants in the aerobic group reached a “minimal clinically important difference,” compared to those in the stretching group (96% vs. 84%, respectively, x2 = 4.4; P = .036).

There were also superior benefits found in the aerobic versus the stretching group on depression severity at 6 months (a secondary outcome), with a mean difference in Beck Depression Inventory-2 score of 5.7 (95% CI, 0.5-10.9; P = .022), yielding a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.1-1.0]).

There were no adverse events associated with the intervention, and almost all the sessions (88%) complied with the treatment protocol.

The researchers noted several limitations. For example, they did not obtain plasma to measure BDNF concentrations, so they could not “infer whether the mechanism of change involved BDNF.”

In addition, they did not perform sex-specific analyses. “Future studies could increase the sample size to investigate sex differences because females display less BDNF change following exercise than do males,” they wrote.

Nevertheless, the study “provides initial evidence of a simple and accessible strategy that clinicians could readily apply in combination with exposure therapy,” they stated. “Whereas many pharmacologic interventions pose barriers, including cost, requirement for prescriptions, and patient resistance to drugs, exercise offers clinicians a strategy that can be implemented with few barriers.”

Dr. Bryant emphasized that one study “does not represent a body of evidence, and so it is essential that this finding be replicated in other trials before it can be recommended for clinical use.” He noted that other trials are “currently underway.”

Easy augmentation

In a comment, Barbara Rothbaum, PhD, professor in psychiatry and director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory University, Atlanta, called it a “well-controlled trial augmenting exposure therapy for PTSD with brief aerobic exercise and finding some benefits of the augmented condition at 6 months posttreatment but not immediately posttreatment.”

The study’s methodology – that is, using independent standard assessment of PTSD and rating audio recordings of therapy sessions for treatment fidelity and quality – can lead us to “be confident in their [the researchers’] conclusions,” she said.

Dr. Rothbaum, who was not associated with this study, described research into methods to augment exposure therapy for PTSD as “timely and clinically relevant.”

Exercise “would be an easy augmentation for many clinicians if it is helpful,” she noted.

The study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. The authors and Dr. Rothbaum reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators randomly assigned individuals with PTSD to receive either exposure therapy with aerobic exercise or exposure therapy with passive stretching for 9 weeks. At 6 months post intervention, participants in the aerobic exercise group showed greater reductions in PTSD severity, compared with those in the stretching group.

“There is a critical need to improve outcomes for treating people with PTSD, and this finding points to one potentially cheap and ready-to-use strategy that all clinicians could employ with most patients,” lead author Richard Bryant, MPsych, PhD, DSc, director of the Traumatic Stress Clinic and Scientia Professor of Psychology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told this news organization.

The study was published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

Promoting BDNF

“Trauma-focused psychotherapy is the recommended treatment for PTSD, but up to half of patients do not respond to this treatment,” Dr. Bryant said.

“We know that brain-derived neurotrophic factors [BDNF] are critical for synaptic plasticity, which underpins the learning that occurs in therapy so that reminders of trauma are no longer fear-provoking,” he continued. “Preclinical animal and human research inform us that brief aerobic exercise can promote BDNF and new learning that inhibits fear responses.”

The researchers “hypothesized that brief exercise after exposure therapy to trauma memories – which is the key ingredient of trauma-focused psychotherapy – would lead to greater reductions in PTSD, relative to standard trauma-focused therapy,” he said.

To investigate the question, the researchers randomly assigned 130 adults with PTSD (mean age, 39 years; 61% female; 76% White) to receive nine 90-minute sessions of exposure therapy with either aerobic exercise or passive stretching (n = 65 in each group).

There were no differences at baseline in sociodemographic characteristics or psychopathology measures, although the mean age of the stretching group was slightly older than that of the aerobic group (40 years vs. 37 years, respectively), and there was a slightly higher proportion of women in the stretching group (68% vs. 54%).

Participants did not differ on weekly exercise either at baseline, immediately post treatment, or at 6-week follow-up.

PTSD severity (the primary outcome) was measured using the clinician-administered PTSD scale CAPS-2, with assessments conducted at baseline, 1 week post treatment, and 6 months post treatment.

The aerobic exercise regimen was tailored to each participant, based on an assessment of his/her aerobic target zone.

The exposure therapy sessions were identical for both groups. Following the exposure sessions, participants engaged in their respective exercises: Those in the passive stretching group engaged in 20 minutes of exercise, while those in the aerobic group participated in a total of 20 minutes of exercise, with 10 conducted at their personal aerobic target heart rate.

“This level of exercise was chosen because BDNF concentration in the serum is increased by two 3-minute bouts of aerobic exercise, and 10 minutes of aerobic exercise can facilitate extinction learning,” the authors explained.

The aerobic activity consisted of running on a stepper exercise platform while having cardiac activity recorded. A small portion (10%) of the therapy sessions were recorded and rated for treatment fidelity.

Change in PTSD was the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes consisting of changes in depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder, and posttraumatic cognitions.

Few barriers

The researchers found no significant differences in PTSD severity, as measured by CAPS-2 score, between treatment groups at 10 weeks – that is, immediately post treatment (mean difference, 7.0; 95% confidence interval, –2.3 to 16.4; P = .14).

However, significantly greater reductions in PTSD severity were found in the aerobic versus the stretching group at 6-month follow-up (mean difference, 12.1;95% CI, 2.4-21.8; P = .023), pointing to a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.1-1.1]).

Although there were no differences found at 6-month assessment between rates of PTSD diagnosis (25% of the aerobic vs 27% of the stretching group), more participants in the aerobic group reached a “minimal clinically important difference,” compared to those in the stretching group (96% vs. 84%, respectively, x2 = 4.4; P = .036).

There were also superior benefits found in the aerobic versus the stretching group on depression severity at 6 months (a secondary outcome), with a mean difference in Beck Depression Inventory-2 score of 5.7 (95% CI, 0.5-10.9; P = .022), yielding a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.1-1.0]).

There were no adverse events associated with the intervention, and almost all the sessions (88%) complied with the treatment protocol.

The researchers noted several limitations. For example, they did not obtain plasma to measure BDNF concentrations, so they could not “infer whether the mechanism of change involved BDNF.”

In addition, they did not perform sex-specific analyses. “Future studies could increase the sample size to investigate sex differences because females display less BDNF change following exercise than do males,” they wrote.

Nevertheless, the study “provides initial evidence of a simple and accessible strategy that clinicians could readily apply in combination with exposure therapy,” they stated. “Whereas many pharmacologic interventions pose barriers, including cost, requirement for prescriptions, and patient resistance to drugs, exercise offers clinicians a strategy that can be implemented with few barriers.”

Dr. Bryant emphasized that one study “does not represent a body of evidence, and so it is essential that this finding be replicated in other trials before it can be recommended for clinical use.” He noted that other trials are “currently underway.”

Easy augmentation

In a comment, Barbara Rothbaum, PhD, professor in psychiatry and director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory University, Atlanta, called it a “well-controlled trial augmenting exposure therapy for PTSD with brief aerobic exercise and finding some benefits of the augmented condition at 6 months posttreatment but not immediately posttreatment.”

The study’s methodology – that is, using independent standard assessment of PTSD and rating audio recordings of therapy sessions for treatment fidelity and quality – can lead us to “be confident in their [the researchers’] conclusions,” she said.

Dr. Rothbaum, who was not associated with this study, described research into methods to augment exposure therapy for PTSD as “timely and clinically relevant.”

Exercise “would be an easy augmentation for many clinicians if it is helpful,” she noted.

The study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. The authors and Dr. Rothbaum reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators randomly assigned individuals with PTSD to receive either exposure therapy with aerobic exercise or exposure therapy with passive stretching for 9 weeks. At 6 months post intervention, participants in the aerobic exercise group showed greater reductions in PTSD severity, compared with those in the stretching group.

“There is a critical need to improve outcomes for treating people with PTSD, and this finding points to one potentially cheap and ready-to-use strategy that all clinicians could employ with most patients,” lead author Richard Bryant, MPsych, PhD, DSc, director of the Traumatic Stress Clinic and Scientia Professor of Psychology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told this news organization.

The study was published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

Promoting BDNF

“Trauma-focused psychotherapy is the recommended treatment for PTSD, but up to half of patients do not respond to this treatment,” Dr. Bryant said.

“We know that brain-derived neurotrophic factors [BDNF] are critical for synaptic plasticity, which underpins the learning that occurs in therapy so that reminders of trauma are no longer fear-provoking,” he continued. “Preclinical animal and human research inform us that brief aerobic exercise can promote BDNF and new learning that inhibits fear responses.”

The researchers “hypothesized that brief exercise after exposure therapy to trauma memories – which is the key ingredient of trauma-focused psychotherapy – would lead to greater reductions in PTSD, relative to standard trauma-focused therapy,” he said.

To investigate the question, the researchers randomly assigned 130 adults with PTSD (mean age, 39 years; 61% female; 76% White) to receive nine 90-minute sessions of exposure therapy with either aerobic exercise or passive stretching (n = 65 in each group).

There were no differences at baseline in sociodemographic characteristics or psychopathology measures, although the mean age of the stretching group was slightly older than that of the aerobic group (40 years vs. 37 years, respectively), and there was a slightly higher proportion of women in the stretching group (68% vs. 54%).

Participants did not differ on weekly exercise either at baseline, immediately post treatment, or at 6-week follow-up.

PTSD severity (the primary outcome) was measured using the clinician-administered PTSD scale CAPS-2, with assessments conducted at baseline, 1 week post treatment, and 6 months post treatment.

The aerobic exercise regimen was tailored to each participant, based on an assessment of his/her aerobic target zone.

The exposure therapy sessions were identical for both groups. Following the exposure sessions, participants engaged in their respective exercises: Those in the passive stretching group engaged in 20 minutes of exercise, while those in the aerobic group participated in a total of 20 minutes of exercise, with 10 conducted at their personal aerobic target heart rate.

“This level of exercise was chosen because BDNF concentration in the serum is increased by two 3-minute bouts of aerobic exercise, and 10 minutes of aerobic exercise can facilitate extinction learning,” the authors explained.

The aerobic activity consisted of running on a stepper exercise platform while having cardiac activity recorded. A small portion (10%) of the therapy sessions were recorded and rated for treatment fidelity.

Change in PTSD was the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes consisting of changes in depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder, and posttraumatic cognitions.

Few barriers

The researchers found no significant differences in PTSD severity, as measured by CAPS-2 score, between treatment groups at 10 weeks – that is, immediately post treatment (mean difference, 7.0; 95% confidence interval, –2.3 to 16.4; P = .14).

However, significantly greater reductions in PTSD severity were found in the aerobic versus the stretching group at 6-month follow-up (mean difference, 12.1;95% CI, 2.4-21.8; P = .023), pointing to a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.1-1.1]).

Although there were no differences found at 6-month assessment between rates of PTSD diagnosis (25% of the aerobic vs 27% of the stretching group), more participants in the aerobic group reached a “minimal clinically important difference,” compared to those in the stretching group (96% vs. 84%, respectively, x2 = 4.4; P = .036).

There were also superior benefits found in the aerobic versus the stretching group on depression severity at 6 months (a secondary outcome), with a mean difference in Beck Depression Inventory-2 score of 5.7 (95% CI, 0.5-10.9; P = .022), yielding a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.1-1.0]).

There were no adverse events associated with the intervention, and almost all the sessions (88%) complied with the treatment protocol.

The researchers noted several limitations. For example, they did not obtain plasma to measure BDNF concentrations, so they could not “infer whether the mechanism of change involved BDNF.”

In addition, they did not perform sex-specific analyses. “Future studies could increase the sample size to investigate sex differences because females display less BDNF change following exercise than do males,” they wrote.

Nevertheless, the study “provides initial evidence of a simple and accessible strategy that clinicians could readily apply in combination with exposure therapy,” they stated. “Whereas many pharmacologic interventions pose barriers, including cost, requirement for prescriptions, and patient resistance to drugs, exercise offers clinicians a strategy that can be implemented with few barriers.”

Dr. Bryant emphasized that one study “does not represent a body of evidence, and so it is essential that this finding be replicated in other trials before it can be recommended for clinical use.” He noted that other trials are “currently underway.”

Easy augmentation

In a comment, Barbara Rothbaum, PhD, professor in psychiatry and director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory University, Atlanta, called it a “well-controlled trial augmenting exposure therapy for PTSD with brief aerobic exercise and finding some benefits of the augmented condition at 6 months posttreatment but not immediately posttreatment.”

The study’s methodology – that is, using independent standard assessment of PTSD and rating audio recordings of therapy sessions for treatment fidelity and quality – can lead us to “be confident in their [the researchers’] conclusions,” she said.

Dr. Rothbaum, who was not associated with this study, described research into methods to augment exposure therapy for PTSD as “timely and clinically relevant.”

Exercise “would be an easy augmentation for many clinicians if it is helpful,” she noted.

The study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. The authors and Dr. Rothbaum reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET PSYCHIATRY

Antipsychotic shows benefit for Alzheimer’s agitation

SAN FRANCISCO – In a widely anticipated report,

Members of a panel of dementia specialists here at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference said that the results were encouraging. But they also noted that the available data make it difficult to understand the impact of the drug on the day-to-day life on patients.

“I’d like to be able to translate that into something else to understand the risk benefit calculus,” said neurologist and neuroscientist Alireza Atri, MD, PhD, of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Phoenix. “How does it affect the patients themselves, their quality of life, and the family members and their burden?”

Currently, there’s no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for agitation in AD.

In 2015, the FDA approved brexpiprazole, an oral medication, as a treatment for schizophrenia and an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). It is an expensive drug with an average retail price per GoodRx of $1,582 per month, and no generic is available.

Researchers released the results of a trio of phase 3 clinical trials at CTAD that examined various doses of brexpiprazole. The results of the first two trials had been released earlier in 2018.

Three trials

All trials were multicenter, 12-week, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled.

Study participants were aged 55-90 years, had probable AD diagnoses, and had agitation per various scales. The average age in the groups was 74 years, 56.0%-61.7% were women, and 94.3%-98.1% were White.

The first trial examined two fixed doses (1 mg/d, n = 137; and 2 mg/d, n = 140) or placebo (n = 136). “The study initially included a 0.5 mg/day arm,” the researchers reported, “which was removed in a protocol amendment, and patients randomized to that arm were not included in efficacy analyses.”

The second trial looked at a flexible dose (0.5-2 mg/d, n = 133) or placebo (n = 137).

In a CTAD presentation, Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck, a codeveloper of the drug, said that the researchers learned from the first two trials that 2 mg/d might be an appropriate dose, and the FDA recommended they also examine 3 mg/day. As a result, the third trial examined two fixed doses (2 mg/d, n = 75; 3 mg/d, n = 153; or placebo, n = 117).

In the third trial, both the placebo and drug groups improved per a measurement of agitation; those in the drug group improved somewhat more.

The mean change in baseline on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scale – the primary endpoint – was –5.32 for the 2-mg/d and 3-mg/d groups vs. placebo (P = .0026); the score in the placebo group fell by about 18 and by about 22 in the drug group.

The key secondary endpoint was an improvement from baseline to week 12 in the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score related to agitation. Compared with the placebo group, this score was –0.27 in the drug group (P = .0078). Both scores hovered around –1.0.

Safety data show the percentage of treatment-emergent events ranged from 45.9% in the placebo group to 49.0%-56.8% for brexpiprazole in the three trials. The percentage of these events leading to discontinuation was 6.3% among those receiving the drug and 3.4% in the placebo group.

University of Exeter dementia researcher Clive Ballard, MD, MB ChB, one of the panelists who discussed the research after the CTAD presentation, praised the trials as “well-conducted” and said that he was pleased that subjects in institutions were included. “It’s not an easy environment to do trials in. They should be really commended for doing for doing that.”

But he echoed fellow panelist Dr. Atri by noting that more data are needed to understand how well the drug works. “I would like to see the effect sizes and a little bit more detail to understand the clinical meaningfulness of that level of benefit.”

What’s next? A spokeswoman for Otsuka, a codeveloper of brexpiprazole, said that it hopes to hear in 2023 about a supplemental new drug application that was filed in November 2022.

Otsuka and Lundbeck funded the research. Mr. Hefting is an employee of Lundbeck, and several other authors work for Lundbeck or Otsuka. The single non-employee author reports various disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Atri and Dr. Ballard were not provided.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – In a widely anticipated report,

Members of a panel of dementia specialists here at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference said that the results were encouraging. But they also noted that the available data make it difficult to understand the impact of the drug on the day-to-day life on patients.

“I’d like to be able to translate that into something else to understand the risk benefit calculus,” said neurologist and neuroscientist Alireza Atri, MD, PhD, of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Phoenix. “How does it affect the patients themselves, their quality of life, and the family members and their burden?”

Currently, there’s no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for agitation in AD.

In 2015, the FDA approved brexpiprazole, an oral medication, as a treatment for schizophrenia and an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). It is an expensive drug with an average retail price per GoodRx of $1,582 per month, and no generic is available.

Researchers released the results of a trio of phase 3 clinical trials at CTAD that examined various doses of brexpiprazole. The results of the first two trials had been released earlier in 2018.

Three trials

All trials were multicenter, 12-week, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled.

Study participants were aged 55-90 years, had probable AD diagnoses, and had agitation per various scales. The average age in the groups was 74 years, 56.0%-61.7% were women, and 94.3%-98.1% were White.

The first trial examined two fixed doses (1 mg/d, n = 137; and 2 mg/d, n = 140) or placebo (n = 136). “The study initially included a 0.5 mg/day arm,” the researchers reported, “which was removed in a protocol amendment, and patients randomized to that arm were not included in efficacy analyses.”

The second trial looked at a flexible dose (0.5-2 mg/d, n = 133) or placebo (n = 137).

In a CTAD presentation, Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck, a codeveloper of the drug, said that the researchers learned from the first two trials that 2 mg/d might be an appropriate dose, and the FDA recommended they also examine 3 mg/day. As a result, the third trial examined two fixed doses (2 mg/d, n = 75; 3 mg/d, n = 153; or placebo, n = 117).

In the third trial, both the placebo and drug groups improved per a measurement of agitation; those in the drug group improved somewhat more.

The mean change in baseline on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scale – the primary endpoint – was –5.32 for the 2-mg/d and 3-mg/d groups vs. placebo (P = .0026); the score in the placebo group fell by about 18 and by about 22 in the drug group.

The key secondary endpoint was an improvement from baseline to week 12 in the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score related to agitation. Compared with the placebo group, this score was –0.27 in the drug group (P = .0078). Both scores hovered around –1.0.

Safety data show the percentage of treatment-emergent events ranged from 45.9% in the placebo group to 49.0%-56.8% for brexpiprazole in the three trials. The percentage of these events leading to discontinuation was 6.3% among those receiving the drug and 3.4% in the placebo group.

University of Exeter dementia researcher Clive Ballard, MD, MB ChB, one of the panelists who discussed the research after the CTAD presentation, praised the trials as “well-conducted” and said that he was pleased that subjects in institutions were included. “It’s not an easy environment to do trials in. They should be really commended for doing for doing that.”

But he echoed fellow panelist Dr. Atri by noting that more data are needed to understand how well the drug works. “I would like to see the effect sizes and a little bit more detail to understand the clinical meaningfulness of that level of benefit.”

What’s next? A spokeswoman for Otsuka, a codeveloper of brexpiprazole, said that it hopes to hear in 2023 about a supplemental new drug application that was filed in November 2022.

Otsuka and Lundbeck funded the research. Mr. Hefting is an employee of Lundbeck, and several other authors work for Lundbeck or Otsuka. The single non-employee author reports various disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Atri and Dr. Ballard were not provided.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – In a widely anticipated report,

Members of a panel of dementia specialists here at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference said that the results were encouraging. But they also noted that the available data make it difficult to understand the impact of the drug on the day-to-day life on patients.

“I’d like to be able to translate that into something else to understand the risk benefit calculus,” said neurologist and neuroscientist Alireza Atri, MD, PhD, of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Phoenix. “How does it affect the patients themselves, their quality of life, and the family members and their burden?”

Currently, there’s no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for agitation in AD.

In 2015, the FDA approved brexpiprazole, an oral medication, as a treatment for schizophrenia and an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). It is an expensive drug with an average retail price per GoodRx of $1,582 per month, and no generic is available.

Researchers released the results of a trio of phase 3 clinical trials at CTAD that examined various doses of brexpiprazole. The results of the first two trials had been released earlier in 2018.

Three trials

All trials were multicenter, 12-week, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled.

Study participants were aged 55-90 years, had probable AD diagnoses, and had agitation per various scales. The average age in the groups was 74 years, 56.0%-61.7% were women, and 94.3%-98.1% were White.

The first trial examined two fixed doses (1 mg/d, n = 137; and 2 mg/d, n = 140) or placebo (n = 136). “The study initially included a 0.5 mg/day arm,” the researchers reported, “which was removed in a protocol amendment, and patients randomized to that arm were not included in efficacy analyses.”

The second trial looked at a flexible dose (0.5-2 mg/d, n = 133) or placebo (n = 137).

In a CTAD presentation, Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck, a codeveloper of the drug, said that the researchers learned from the first two trials that 2 mg/d might be an appropriate dose, and the FDA recommended they also examine 3 mg/day. As a result, the third trial examined two fixed doses (2 mg/d, n = 75; 3 mg/d, n = 153; or placebo, n = 117).

In the third trial, both the placebo and drug groups improved per a measurement of agitation; those in the drug group improved somewhat more.

The mean change in baseline on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scale – the primary endpoint – was –5.32 for the 2-mg/d and 3-mg/d groups vs. placebo (P = .0026); the score in the placebo group fell by about 18 and by about 22 in the drug group.

The key secondary endpoint was an improvement from baseline to week 12 in the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score related to agitation. Compared with the placebo group, this score was –0.27 in the drug group (P = .0078). Both scores hovered around –1.0.

Safety data show the percentage of treatment-emergent events ranged from 45.9% in the placebo group to 49.0%-56.8% for brexpiprazole in the three trials. The percentage of these events leading to discontinuation was 6.3% among those receiving the drug and 3.4% in the placebo group.

University of Exeter dementia researcher Clive Ballard, MD, MB ChB, one of the panelists who discussed the research after the CTAD presentation, praised the trials as “well-conducted” and said that he was pleased that subjects in institutions were included. “It’s not an easy environment to do trials in. They should be really commended for doing for doing that.”

But he echoed fellow panelist Dr. Atri by noting that more data are needed to understand how well the drug works. “I would like to see the effect sizes and a little bit more detail to understand the clinical meaningfulness of that level of benefit.”

What’s next? A spokeswoman for Otsuka, a codeveloper of brexpiprazole, said that it hopes to hear in 2023 about a supplemental new drug application that was filed in November 2022.

Otsuka and Lundbeck funded the research. Mr. Hefting is an employee of Lundbeck, and several other authors work for Lundbeck or Otsuka. The single non-employee author reports various disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Atri and Dr. Ballard were not provided.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT CTAD 2022

Mindfulness, exercise strike out in memory trial

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

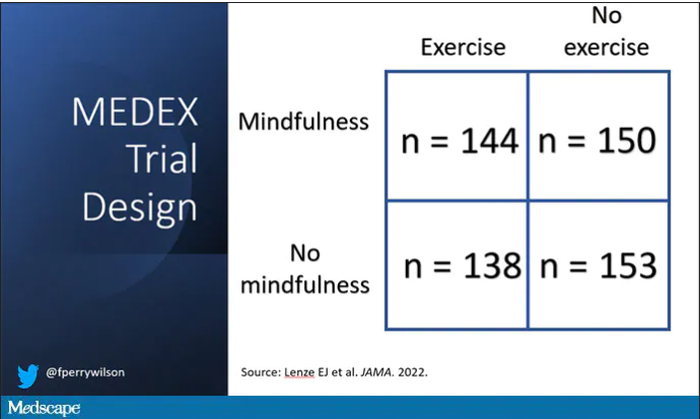

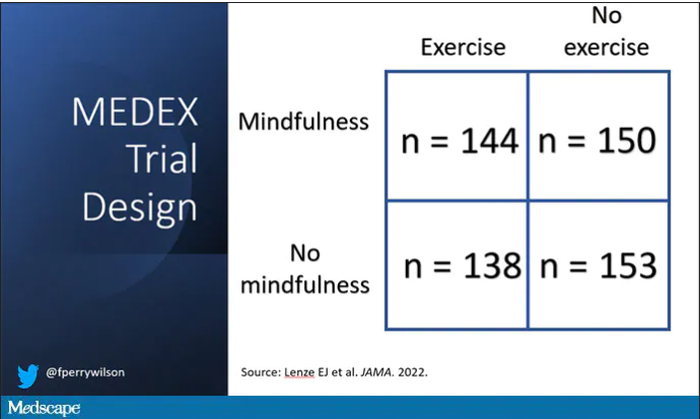

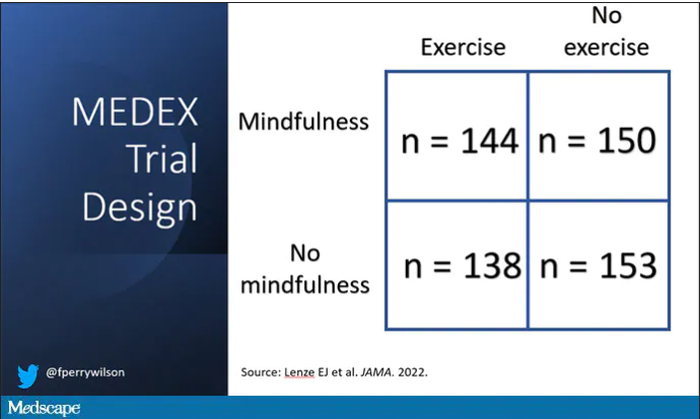

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.