User login

Colchicine reduces inflammatory markers associated with metabolic syndrome

A small study offers a tantalizing hint that

The 3-month trial did not meet its primary endpoint – change in insulin sensitivity as measured by a glucose tolerance test – but it did hit several secondary goals, all of which were related to the inflammation that accompanies prediabetes, Jack A. Yanovski, MD, and colleagues wrote in Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism.

“Colchicine is well-known to have anti-inflammatory properties, although its effect on obesity-associated inflammation has not previously been investigated,” said Dr. Yanovski of the National institutes of Health and his coauthors. “Classically, it has been posited that colchicine blocks inflammation by impeding leukocyte locomotion, diapedesis, and, ultimately, recruitment to sites of inflammation. ... Recently, it has been shown that colchicine also inhibits the formation of the NLRP3 [NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3] inflammasome, an important component of the obesity-associated inflammatory cascade.”

The NLRP3 inflammasome has been shown to play an important part in promoting the inflammatory state of obesity, the authors noted. When a cell senses danger, NLRP3 uses microtubules to create an inflammasome that then produces interleukin-1 beta gene and interleukin-18. One of colchicine’s known actions is to inhibit microtubule formation, suggesting that it could put the brakes on this process.

The study comprised 40 patients who had metabolic syndrome, significant insulin resistance, and elevated inflammatory markers. Among the exclusionary criteria were having a significant medical illness, a history of gout, and recent or current use of colchicine.

The patients were randomized to colchicine 0.6 mg or placebo twice daily for 3 months. No dietary advice was given during the study period. Of the 40 randomized patients, 37 completed the 3-month study, though none left because of adverse events.

Although there were no significant between-group differences in levels of fasting insulin, colchicine did significantly decrease inflammatory markers, compared with placebo. C-reactive protein dropped by 2.8 mg/L in the active group but increased slightly in the placebo group. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate also decreased in the colchicine group, compared with placebo (difference, –5.9 mm/hr; P = .07). The active group experienced an improvement in fasting insulin as measured by the homeostasis model assessment–estimated insulin resistance index and in glucose effectiveness, which suggests metabolic improvement.

“Larger trials are needed to investigate whether colchicine has efficacy in improving insulin resistance and/or preventing the onset of diabetes mellitus in at-risk individuals with obesity-associated inflammation,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by the National Institutes of Health. None of the authors reported any disclosures or conflicts of interest relating to this study.

SOURCE: Yanovski JA et al. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1111/dom.13702.

A small study offers a tantalizing hint that

The 3-month trial did not meet its primary endpoint – change in insulin sensitivity as measured by a glucose tolerance test – but it did hit several secondary goals, all of which were related to the inflammation that accompanies prediabetes, Jack A. Yanovski, MD, and colleagues wrote in Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism.

“Colchicine is well-known to have anti-inflammatory properties, although its effect on obesity-associated inflammation has not previously been investigated,” said Dr. Yanovski of the National institutes of Health and his coauthors. “Classically, it has been posited that colchicine blocks inflammation by impeding leukocyte locomotion, diapedesis, and, ultimately, recruitment to sites of inflammation. ... Recently, it has been shown that colchicine also inhibits the formation of the NLRP3 [NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3] inflammasome, an important component of the obesity-associated inflammatory cascade.”

The NLRP3 inflammasome has been shown to play an important part in promoting the inflammatory state of obesity, the authors noted. When a cell senses danger, NLRP3 uses microtubules to create an inflammasome that then produces interleukin-1 beta gene and interleukin-18. One of colchicine’s known actions is to inhibit microtubule formation, suggesting that it could put the brakes on this process.

The study comprised 40 patients who had metabolic syndrome, significant insulin resistance, and elevated inflammatory markers. Among the exclusionary criteria were having a significant medical illness, a history of gout, and recent or current use of colchicine.

The patients were randomized to colchicine 0.6 mg or placebo twice daily for 3 months. No dietary advice was given during the study period. Of the 40 randomized patients, 37 completed the 3-month study, though none left because of adverse events.

Although there were no significant between-group differences in levels of fasting insulin, colchicine did significantly decrease inflammatory markers, compared with placebo. C-reactive protein dropped by 2.8 mg/L in the active group but increased slightly in the placebo group. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate also decreased in the colchicine group, compared with placebo (difference, –5.9 mm/hr; P = .07). The active group experienced an improvement in fasting insulin as measured by the homeostasis model assessment–estimated insulin resistance index and in glucose effectiveness, which suggests metabolic improvement.

“Larger trials are needed to investigate whether colchicine has efficacy in improving insulin resistance and/or preventing the onset of diabetes mellitus in at-risk individuals with obesity-associated inflammation,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by the National Institutes of Health. None of the authors reported any disclosures or conflicts of interest relating to this study.

SOURCE: Yanovski JA et al. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1111/dom.13702.

A small study offers a tantalizing hint that

The 3-month trial did not meet its primary endpoint – change in insulin sensitivity as measured by a glucose tolerance test – but it did hit several secondary goals, all of which were related to the inflammation that accompanies prediabetes, Jack A. Yanovski, MD, and colleagues wrote in Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism.

“Colchicine is well-known to have anti-inflammatory properties, although its effect on obesity-associated inflammation has not previously been investigated,” said Dr. Yanovski of the National institutes of Health and his coauthors. “Classically, it has been posited that colchicine blocks inflammation by impeding leukocyte locomotion, diapedesis, and, ultimately, recruitment to sites of inflammation. ... Recently, it has been shown that colchicine also inhibits the formation of the NLRP3 [NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3] inflammasome, an important component of the obesity-associated inflammatory cascade.”

The NLRP3 inflammasome has been shown to play an important part in promoting the inflammatory state of obesity, the authors noted. When a cell senses danger, NLRP3 uses microtubules to create an inflammasome that then produces interleukin-1 beta gene and interleukin-18. One of colchicine’s known actions is to inhibit microtubule formation, suggesting that it could put the brakes on this process.

The study comprised 40 patients who had metabolic syndrome, significant insulin resistance, and elevated inflammatory markers. Among the exclusionary criteria were having a significant medical illness, a history of gout, and recent or current use of colchicine.

The patients were randomized to colchicine 0.6 mg or placebo twice daily for 3 months. No dietary advice was given during the study period. Of the 40 randomized patients, 37 completed the 3-month study, though none left because of adverse events.

Although there were no significant between-group differences in levels of fasting insulin, colchicine did significantly decrease inflammatory markers, compared with placebo. C-reactive protein dropped by 2.8 mg/L in the active group but increased slightly in the placebo group. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate also decreased in the colchicine group, compared with placebo (difference, –5.9 mm/hr; P = .07). The active group experienced an improvement in fasting insulin as measured by the homeostasis model assessment–estimated insulin resistance index and in glucose effectiveness, which suggests metabolic improvement.

“Larger trials are needed to investigate whether colchicine has efficacy in improving insulin resistance and/or preventing the onset of diabetes mellitus in at-risk individuals with obesity-associated inflammation,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by the National Institutes of Health. None of the authors reported any disclosures or conflicts of interest relating to this study.

SOURCE: Yanovski JA et al. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1111/dom.13702.

FROM DIABETES, OBESITY, AND METABOLISM

Improved WIC food packages reverse obesity in toddler participants

Improvements to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food package guidelines in 2009 appear responsible for reversing the upward trend in obesity prevalence among WIC toddler participants, Madeleine I.G. Daepp, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and her associates reported in Pediatrics.

Using data.gov files from 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014, Ms. Daepp and her colleagues conducted a quasi-experimental interrupted time series analysis to compare state-level population trends in obesity prevalence among children aged 2-4 years before and after 2009. The goal of the study was to determine whether the WIC package changes had any influence on obesity trends among program participants. Altogether, data from 2,253,471 children in 2000 and 3,152,137 children in 2012 was included in the analysis.

Among the guidelines updated to encourage healthier eating habits were the addition of cash allowances for the purchase of more fruits and vegetables, reduction by half in the allowable portions of juice, reduction in cheese, transition of toddlers aged 2-4 years to low-fat or skim milk, and replacement of refined-grain products with healthier whole grain products.

Across all states included in the study, the authors reported average obesity prevalence of 13% in 2000 and 15% in 2008. Although no change was observed in 2010, by 2014 the obesity prevalence decreased to 14%. Hawaii was excluded because of concerns about data quality.

Ms. Daepp and her associates “estimated a pre-2009 annual trend of a 0.23% increase in childhood obesity prevalence.” After the 2009 package revision, they estimated “a decline in childhood obesity of 0.34% per year [P less than .001].”

This change could not be explained by racial-ethnic makeup or child poverty, changes in maternal prepregnancy body mass indices, or prevalence of macrosomia. Speculating that “unmeasured heterogeneity in WIC populations across states” might explain the difference, the authors also suggested that variance in how effectively the package changes were implemented from state to state could be a factor.

Ms. Daepp and her associates recommended that future studies should focus on evaluating differences in how closely vendors follow the package changes, as well as considering whether any other implementation factors could have an influence on state-by-state trends in childhood obesity.

Study limitations noted included an absence of individual body mass index data and information on changes in energy intake and expenditure.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Daepp was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship grant. Three coauthors were supported by the JPB Foundation; a fourth was supported by an NIH grant.

SOURCE: Daepp MIG et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2841.

Improvements to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food package guidelines in 2009 appear responsible for reversing the upward trend in obesity prevalence among WIC toddler participants, Madeleine I.G. Daepp, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and her associates reported in Pediatrics.

Using data.gov files from 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014, Ms. Daepp and her colleagues conducted a quasi-experimental interrupted time series analysis to compare state-level population trends in obesity prevalence among children aged 2-4 years before and after 2009. The goal of the study was to determine whether the WIC package changes had any influence on obesity trends among program participants. Altogether, data from 2,253,471 children in 2000 and 3,152,137 children in 2012 was included in the analysis.

Among the guidelines updated to encourage healthier eating habits were the addition of cash allowances for the purchase of more fruits and vegetables, reduction by half in the allowable portions of juice, reduction in cheese, transition of toddlers aged 2-4 years to low-fat or skim milk, and replacement of refined-grain products with healthier whole grain products.

Across all states included in the study, the authors reported average obesity prevalence of 13% in 2000 and 15% in 2008. Although no change was observed in 2010, by 2014 the obesity prevalence decreased to 14%. Hawaii was excluded because of concerns about data quality.

Ms. Daepp and her associates “estimated a pre-2009 annual trend of a 0.23% increase in childhood obesity prevalence.” After the 2009 package revision, they estimated “a decline in childhood obesity of 0.34% per year [P less than .001].”

This change could not be explained by racial-ethnic makeup or child poverty, changes in maternal prepregnancy body mass indices, or prevalence of macrosomia. Speculating that “unmeasured heterogeneity in WIC populations across states” might explain the difference, the authors also suggested that variance in how effectively the package changes were implemented from state to state could be a factor.

Ms. Daepp and her associates recommended that future studies should focus on evaluating differences in how closely vendors follow the package changes, as well as considering whether any other implementation factors could have an influence on state-by-state trends in childhood obesity.

Study limitations noted included an absence of individual body mass index data and information on changes in energy intake and expenditure.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Daepp was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship grant. Three coauthors were supported by the JPB Foundation; a fourth was supported by an NIH grant.

SOURCE: Daepp MIG et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2841.

Improvements to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food package guidelines in 2009 appear responsible for reversing the upward trend in obesity prevalence among WIC toddler participants, Madeleine I.G. Daepp, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, and her associates reported in Pediatrics.

Using data.gov files from 2008, 2010, 2012, and 2014, Ms. Daepp and her colleagues conducted a quasi-experimental interrupted time series analysis to compare state-level population trends in obesity prevalence among children aged 2-4 years before and after 2009. The goal of the study was to determine whether the WIC package changes had any influence on obesity trends among program participants. Altogether, data from 2,253,471 children in 2000 and 3,152,137 children in 2012 was included in the analysis.

Among the guidelines updated to encourage healthier eating habits were the addition of cash allowances for the purchase of more fruits and vegetables, reduction by half in the allowable portions of juice, reduction in cheese, transition of toddlers aged 2-4 years to low-fat or skim milk, and replacement of refined-grain products with healthier whole grain products.

Across all states included in the study, the authors reported average obesity prevalence of 13% in 2000 and 15% in 2008. Although no change was observed in 2010, by 2014 the obesity prevalence decreased to 14%. Hawaii was excluded because of concerns about data quality.

Ms. Daepp and her associates “estimated a pre-2009 annual trend of a 0.23% increase in childhood obesity prevalence.” After the 2009 package revision, they estimated “a decline in childhood obesity of 0.34% per year [P less than .001].”

This change could not be explained by racial-ethnic makeup or child poverty, changes in maternal prepregnancy body mass indices, or prevalence of macrosomia. Speculating that “unmeasured heterogeneity in WIC populations across states” might explain the difference, the authors also suggested that variance in how effectively the package changes were implemented from state to state could be a factor.

Ms. Daepp and her associates recommended that future studies should focus on evaluating differences in how closely vendors follow the package changes, as well as considering whether any other implementation factors could have an influence on state-by-state trends in childhood obesity.

Study limitations noted included an absence of individual body mass index data and information on changes in energy intake and expenditure.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Ms. Daepp was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship grant. Three coauthors were supported by the JPB Foundation; a fourth was supported by an NIH grant.

SOURCE: Daepp MIG et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2841.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Noninfected children of HIV-positive mothers have high rates of obesity

NEW ORLEANS – than are those with no such exposure, according to research that provides a compelling link between inflammatory activity in utero and subsequent risk of metabolic disorders.

Most supportive of that link was a near-linear inverse relationship between CD4 counts during the time of pregnancy and risk of both obesity and reactive respiratory disease more than a decade later, according to research presented by Lindsay Fourman, MD, an instructor in medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, during the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

In this video interview, Dr. Fourman discusses the effort to understand the long-term health consequences of being exposed to HIV and antiretroviral therapies while in utero, a group known by the acronym HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU). With effective therapies now routinely preventing mother-to-child transmission, this population of children is growing quickly.

For this study, 50 HEU individuals were identified from a patient database. They were matched in a 3:1 ratio to a control group for a variety of demographic and socioeconomic variables. At a median age of 18 years, the HEU population was found to have a “strikingly” higher rate of obesity, compared with controls (42% vs. 25%, respectively; P = .04). The rate of reactive airway disease was similarly increased in the HEU group (40% vs. 24%; P = .04).

These data are important for considering health risks in an HEU population, but Dr. Fourman explained that it provides support for looking at metabolic risks from other in utero exposures linked to upregulated inflammation, such as gestational diabetes or obesity.

Dr Fourman and her colleagues reported no disclosures or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Fourman L et al. ENDO 2019, Session P10 (SAT-256).

NEW ORLEANS – than are those with no such exposure, according to research that provides a compelling link between inflammatory activity in utero and subsequent risk of metabolic disorders.

Most supportive of that link was a near-linear inverse relationship between CD4 counts during the time of pregnancy and risk of both obesity and reactive respiratory disease more than a decade later, according to research presented by Lindsay Fourman, MD, an instructor in medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, during the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

In this video interview, Dr. Fourman discusses the effort to understand the long-term health consequences of being exposed to HIV and antiretroviral therapies while in utero, a group known by the acronym HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU). With effective therapies now routinely preventing mother-to-child transmission, this population of children is growing quickly.

For this study, 50 HEU individuals were identified from a patient database. They were matched in a 3:1 ratio to a control group for a variety of demographic and socioeconomic variables. At a median age of 18 years, the HEU population was found to have a “strikingly” higher rate of obesity, compared with controls (42% vs. 25%, respectively; P = .04). The rate of reactive airway disease was similarly increased in the HEU group (40% vs. 24%; P = .04).

These data are important for considering health risks in an HEU population, but Dr. Fourman explained that it provides support for looking at metabolic risks from other in utero exposures linked to upregulated inflammation, such as gestational diabetes or obesity.

Dr Fourman and her colleagues reported no disclosures or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Fourman L et al. ENDO 2019, Session P10 (SAT-256).

NEW ORLEANS – than are those with no such exposure, according to research that provides a compelling link between inflammatory activity in utero and subsequent risk of metabolic disorders.

Most supportive of that link was a near-linear inverse relationship between CD4 counts during the time of pregnancy and risk of both obesity and reactive respiratory disease more than a decade later, according to research presented by Lindsay Fourman, MD, an instructor in medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, during the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

In this video interview, Dr. Fourman discusses the effort to understand the long-term health consequences of being exposed to HIV and antiretroviral therapies while in utero, a group known by the acronym HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU). With effective therapies now routinely preventing mother-to-child transmission, this population of children is growing quickly.

For this study, 50 HEU individuals were identified from a patient database. They were matched in a 3:1 ratio to a control group for a variety of demographic and socioeconomic variables. At a median age of 18 years, the HEU population was found to have a “strikingly” higher rate of obesity, compared with controls (42% vs. 25%, respectively; P = .04). The rate of reactive airway disease was similarly increased in the HEU group (40% vs. 24%; P = .04).

These data are important for considering health risks in an HEU population, but Dr. Fourman explained that it provides support for looking at metabolic risks from other in utero exposures linked to upregulated inflammation, such as gestational diabetes or obesity.

Dr Fourman and her colleagues reported no disclosures or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Fourman L et al. ENDO 2019, Session P10 (SAT-256).

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2019

In obesity-related asthma, a new hormonal target

NEW ORLEANS – A hormone that is oversecreted in obesity may provide a pathway from adipose to lung tissue in individuals with both obesity and asthma, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“Obesity-related asthma is a really understudied and new phenomenon. It’s a unique complication of obesity,” said Furkan Burak, MD, in a video interview after an obesity-focused press conference.

“In addition to being a standalone disease, obesity mostly comes as a package. And that’s the problem,” said Dr. Burak, pointing to obesity-related asthma’s clustering with diseases such as diabetes and atherosclerosis.

Asthma affects 10% of the world population, and it’s becoming increasingly understood that said Dr. Burak, an endocrinology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“There are two types of asthma related to obesity,” he said. Classic allergic asthma can get worse with obesity; however, asthma can sometimes occur de novo in adults, particularly women, with obesity. “What is important is … that they are less responsive to classic treatments,” such as steroids and beta-agonists. “And the problem is not small: Of asthmatics, 40% are obese. It’s a therapeutic problem, and we are not able to treat them well.”

The fatty acid binding protein 4, aP2, a hormone that is released by adipose tissue, travels to distant organs and regulates metabolic responses. Levels of aP2 are known to be increased in obesity, particularly in individuals with asthma, said Dr. Burak.

Citing work done at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and at Boston’s Harvard Medical School, as well as elsewhere, Dr. Burak and his collaborators noted in the abstract accompanying the presentation that “increased serum aP2 levels strongly correlate with poor metabolic, inflammatory, and cardiovascular outcomes in multiple independent human studies.”

Dr. Burak said he and his colleagues are trying to sort out “how a fat-tissue–borne hormone could potentially cause a problem in the lung.”

A big clue came with the discovery that patients with asthma and obesity have elevated levels of aP2 within their airways when bronchoalveolar lavage is performed, suggesting that the hormone may be the pathological mediator linking obesity to asthma – “a direct link between the fat tissue and the lung,” he said.

Serum aP2 levels were available from the Nurse’s Health Study, so Dr. Burak and his colleagues looked at those levels in randomly selected study participants. “We found that aP2 levels were elevated 25.6% – significantly – in asthmatics, compared with nonasthmatics, but only in obese and overweight [participants, and] not in lean” participants, he said.

Dr. Burak and his colleagues compared 525 individuals with body mass indices of less than 25 kg/m2, of whom 15 had asthma, with 385 individuals with body mass indices of more than 25, of whom 15 of whom had asthma.

Collecting bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from individuals with asthma showed a mean increase of 23% in aP2 levels in patients with obesity compared with lean individuals.

These data taken together show both systemic and local elevations of aP2 in human obesity. “That could contribute to the airway hyperreactivity and to the asthma pathogenesis,” which would confirm findings from animal studies, said Dr. Burak.

Further investigation will focus on individuals who are haploinsufficient for aP2. The group already is known to have lower risk for dyslipidemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, but Dr. Burak and his collaborators also will determine whether asthma incidence is also lower.

The eventual goal is to attack aP2 as a therapeutic target. “Can we inhibit and target aP2 therapeutically in the context of obesity to treat obesity-related asthma? We have a big hope for that.”

Dr. Burak and his colleagues reported no disclosures or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Burak MF et al. ENDO 2019, Session OR01-1.

NEW ORLEANS – A hormone that is oversecreted in obesity may provide a pathway from adipose to lung tissue in individuals with both obesity and asthma, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“Obesity-related asthma is a really understudied and new phenomenon. It’s a unique complication of obesity,” said Furkan Burak, MD, in a video interview after an obesity-focused press conference.

“In addition to being a standalone disease, obesity mostly comes as a package. And that’s the problem,” said Dr. Burak, pointing to obesity-related asthma’s clustering with diseases such as diabetes and atherosclerosis.

Asthma affects 10% of the world population, and it’s becoming increasingly understood that said Dr. Burak, an endocrinology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“There are two types of asthma related to obesity,” he said. Classic allergic asthma can get worse with obesity; however, asthma can sometimes occur de novo in adults, particularly women, with obesity. “What is important is … that they are less responsive to classic treatments,” such as steroids and beta-agonists. “And the problem is not small: Of asthmatics, 40% are obese. It’s a therapeutic problem, and we are not able to treat them well.”

The fatty acid binding protein 4, aP2, a hormone that is released by adipose tissue, travels to distant organs and regulates metabolic responses. Levels of aP2 are known to be increased in obesity, particularly in individuals with asthma, said Dr. Burak.

Citing work done at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and at Boston’s Harvard Medical School, as well as elsewhere, Dr. Burak and his collaborators noted in the abstract accompanying the presentation that “increased serum aP2 levels strongly correlate with poor metabolic, inflammatory, and cardiovascular outcomes in multiple independent human studies.”

Dr. Burak said he and his colleagues are trying to sort out “how a fat-tissue–borne hormone could potentially cause a problem in the lung.”

A big clue came with the discovery that patients with asthma and obesity have elevated levels of aP2 within their airways when bronchoalveolar lavage is performed, suggesting that the hormone may be the pathological mediator linking obesity to asthma – “a direct link between the fat tissue and the lung,” he said.

Serum aP2 levels were available from the Nurse’s Health Study, so Dr. Burak and his colleagues looked at those levels in randomly selected study participants. “We found that aP2 levels were elevated 25.6% – significantly – in asthmatics, compared with nonasthmatics, but only in obese and overweight [participants, and] not in lean” participants, he said.

Dr. Burak and his colleagues compared 525 individuals with body mass indices of less than 25 kg/m2, of whom 15 had asthma, with 385 individuals with body mass indices of more than 25, of whom 15 of whom had asthma.

Collecting bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from individuals with asthma showed a mean increase of 23% in aP2 levels in patients with obesity compared with lean individuals.

These data taken together show both systemic and local elevations of aP2 in human obesity. “That could contribute to the airway hyperreactivity and to the asthma pathogenesis,” which would confirm findings from animal studies, said Dr. Burak.

Further investigation will focus on individuals who are haploinsufficient for aP2. The group already is known to have lower risk for dyslipidemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, but Dr. Burak and his collaborators also will determine whether asthma incidence is also lower.

The eventual goal is to attack aP2 as a therapeutic target. “Can we inhibit and target aP2 therapeutically in the context of obesity to treat obesity-related asthma? We have a big hope for that.”

Dr. Burak and his colleagues reported no disclosures or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Burak MF et al. ENDO 2019, Session OR01-1.

NEW ORLEANS – A hormone that is oversecreted in obesity may provide a pathway from adipose to lung tissue in individuals with both obesity and asthma, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“Obesity-related asthma is a really understudied and new phenomenon. It’s a unique complication of obesity,” said Furkan Burak, MD, in a video interview after an obesity-focused press conference.

“In addition to being a standalone disease, obesity mostly comes as a package. And that’s the problem,” said Dr. Burak, pointing to obesity-related asthma’s clustering with diseases such as diabetes and atherosclerosis.

Asthma affects 10% of the world population, and it’s becoming increasingly understood that said Dr. Burak, an endocrinology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“There are two types of asthma related to obesity,” he said. Classic allergic asthma can get worse with obesity; however, asthma can sometimes occur de novo in adults, particularly women, with obesity. “What is important is … that they are less responsive to classic treatments,” such as steroids and beta-agonists. “And the problem is not small: Of asthmatics, 40% are obese. It’s a therapeutic problem, and we are not able to treat them well.”

The fatty acid binding protein 4, aP2, a hormone that is released by adipose tissue, travels to distant organs and regulates metabolic responses. Levels of aP2 are known to be increased in obesity, particularly in individuals with asthma, said Dr. Burak.

Citing work done at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and at Boston’s Harvard Medical School, as well as elsewhere, Dr. Burak and his collaborators noted in the abstract accompanying the presentation that “increased serum aP2 levels strongly correlate with poor metabolic, inflammatory, and cardiovascular outcomes in multiple independent human studies.”

Dr. Burak said he and his colleagues are trying to sort out “how a fat-tissue–borne hormone could potentially cause a problem in the lung.”

A big clue came with the discovery that patients with asthma and obesity have elevated levels of aP2 within their airways when bronchoalveolar lavage is performed, suggesting that the hormone may be the pathological mediator linking obesity to asthma – “a direct link between the fat tissue and the lung,” he said.

Serum aP2 levels were available from the Nurse’s Health Study, so Dr. Burak and his colleagues looked at those levels in randomly selected study participants. “We found that aP2 levels were elevated 25.6% – significantly – in asthmatics, compared with nonasthmatics, but only in obese and overweight [participants, and] not in lean” participants, he said.

Dr. Burak and his colleagues compared 525 individuals with body mass indices of less than 25 kg/m2, of whom 15 had asthma, with 385 individuals with body mass indices of more than 25, of whom 15 of whom had asthma.

Collecting bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from individuals with asthma showed a mean increase of 23% in aP2 levels in patients with obesity compared with lean individuals.

These data taken together show both systemic and local elevations of aP2 in human obesity. “That could contribute to the airway hyperreactivity and to the asthma pathogenesis,” which would confirm findings from animal studies, said Dr. Burak.

Further investigation will focus on individuals who are haploinsufficient for aP2. The group already is known to have lower risk for dyslipidemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, but Dr. Burak and his collaborators also will determine whether asthma incidence is also lower.

The eventual goal is to attack aP2 as a therapeutic target. “Can we inhibit and target aP2 therapeutically in the context of obesity to treat obesity-related asthma? We have a big hope for that.”

Dr. Burak and his colleagues reported no disclosures or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Burak MF et al. ENDO 2019, Session OR01-1.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2019

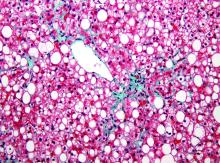

Novel microbiome signature may detect NAFLD-cirrhosis

according to results from a study published in Nature Communications.

“Limited data exist concerning the diagnostic accuracy of gut microbiome–derived signatures for detecting NAFLD-cirrhosis,” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, along with her colleagues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 203 patients with NAFLD. Data was collected from a twin and family cohort with a total of 98 probands that included the complete spectrum of the disease. In addition, 105 first-degree relatives of the probands were also included.

The team analyzed stool samples of participants using MRI and assessed whether the novel signature could accurately identify cirrhosis in NAFLD.

After analysis, the researchers found that in a specific cohort of probands, the microbial biomarker showed strong diagnostic accuracy for identifying cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.92). These findings were validated in another cohort of first-degree relatives of the proband group (AUROC, 0.87).

The authors acknowledged that a key limitation of the analysis was that it was only a single-center study. As a result, the widespread generalizability of the findings could be restricted.

“This conveniently assessed microbial biomarker could present an adjunct tool to current invasive approaches to determine stage of liver disease,” they concluded.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and Janssen. The authors reported financial affiliations with the American Gastroenterological Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Nat Commun. 2019 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9.

according to results from a study published in Nature Communications.

“Limited data exist concerning the diagnostic accuracy of gut microbiome–derived signatures for detecting NAFLD-cirrhosis,” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, along with her colleagues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 203 patients with NAFLD. Data was collected from a twin and family cohort with a total of 98 probands that included the complete spectrum of the disease. In addition, 105 first-degree relatives of the probands were also included.

The team analyzed stool samples of participants using MRI and assessed whether the novel signature could accurately identify cirrhosis in NAFLD.

After analysis, the researchers found that in a specific cohort of probands, the microbial biomarker showed strong diagnostic accuracy for identifying cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.92). These findings were validated in another cohort of first-degree relatives of the proband group (AUROC, 0.87).

The authors acknowledged that a key limitation of the analysis was that it was only a single-center study. As a result, the widespread generalizability of the findings could be restricted.

“This conveniently assessed microbial biomarker could present an adjunct tool to current invasive approaches to determine stage of liver disease,” they concluded.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and Janssen. The authors reported financial affiliations with the American Gastroenterological Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Nat Commun. 2019 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9.

according to results from a study published in Nature Communications.

“Limited data exist concerning the diagnostic accuracy of gut microbiome–derived signatures for detecting NAFLD-cirrhosis,” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, along with her colleagues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 203 patients with NAFLD. Data was collected from a twin and family cohort with a total of 98 probands that included the complete spectrum of the disease. In addition, 105 first-degree relatives of the probands were also included.

The team analyzed stool samples of participants using MRI and assessed whether the novel signature could accurately identify cirrhosis in NAFLD.

After analysis, the researchers found that in a specific cohort of probands, the microbial biomarker showed strong diagnostic accuracy for identifying cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.92). These findings were validated in another cohort of first-degree relatives of the proband group (AUROC, 0.87).

The authors acknowledged that a key limitation of the analysis was that it was only a single-center study. As a result, the widespread generalizability of the findings could be restricted.

“This conveniently assessed microbial biomarker could present an adjunct tool to current invasive approaches to determine stage of liver disease,” they concluded.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and Janssen. The authors reported financial affiliations with the American Gastroenterological Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Nat Commun. 2019 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

Bariatric surgery may be appropriate for class 1 obesity

LAS VEGAS – Once reserved for the most obese patients, bariatric surgery is on the road to becoming an option for millions of Americans who are just a step beyond overweight, even those with a body mass index as low as 30 kg/m2.

In regard to patients with lower levels of obesity, “we should be intervening in this chronic disease earlier rather than later,” said Stacy A. Brethauer, MD, professor of surgery at the Ohio State University, Columbus, in a presentation about new standards for bariatric surgery at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Bariatric treatment “should be offered after nonsurgical [weight-loss] therapy has failed,” he said. “That’s not where you stop. You continue to escalate as you would for heart disease or cancer.”

As Dr. Brethauer noted, research suggests that all categories of obesity – including so-called class 1 obesity (defined as a BMI from 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2) – boost the risk of multiple diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, pulmonary embolism, gallbladder disease, several types of cancer, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain.

“There is no question that class 1 obesity is clearly putting people at risk,” he said. “Ultimately, you can conclude from all this evidence that class 1 is a chronic disease, and it deserves to be treated effectively.”

There are, of course, various nonsurgical treatments for obesity, including diet and exercise and pharmacotherapy. However, systematic reviews have found that people find it extremely difficult to keep the weight off after 1 year regardless of the strategy they adopt.

Beyond a year, Dr. Brethauer said, “you get poor maintenance of weight control, and you get poor control of metabolic burden. You don’t have a durable efficacy.”

In the past, bariatric surgery wasn’t considered an option for patients with class 1 obesity. It’s traditionally been reserved for patients with BMIs at or above 35 kg/m2. But this standard has evolved in recent years.

In 2018, Dr. Brethauer coauthored an updated position statement by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery that encouraged bariatric surgery in certain mildly obese patients.

“For most people with class I obesity,” the statement on bariatric surgery states, “it is clear that the nonsurgical group of therapies will not provide a durable solution to their disease of obesity.”

The statement went on to say that “surgical intervention should be considered after failure of nonsurgical treatments” in the class 1 population.

Bariatric surgery in the class 1 population does more than reduce obesity, Dr. Brethauer said. “Over the last 5 years or so, a large body of literature has emerged,” he said, and both systematic reviews and randomized trails have shown significant postsurgery improvements in comorbidities such as diabetes.

“It’s important to emphasize that these patients don’t become underweight,” he said. “The body finds a healthy set point. They don’t become underweight or malnourished because you’re operating on a lower-weight group.”

Are weight-loss operations safe in class 1 patients? The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery statement says that research has found “bariatric surgery is associated with modest morbidity and very low mortality in patients with class I obesity.”

In fact, Dr. Brethauer said, the mortality rate in this population is “less than gallbladder surgery, less than hip surgery, less than hysterectomy, less than knee surgery – operations people are being referred for and undergoing all the time.”

He added: “The case can be made very clearly based on this data that these operations are safe in this patient population. Not only are they safe, they have durable and significant impact on comorbidities.”

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Brethauer discloses relationships with Medtronic (speaker) and GI Windows (consultant).

Review the AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper, which provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at http://ow.ly/WV8l30oeyYv.

LAS VEGAS – Once reserved for the most obese patients, bariatric surgery is on the road to becoming an option for millions of Americans who are just a step beyond overweight, even those with a body mass index as low as 30 kg/m2.

In regard to patients with lower levels of obesity, “we should be intervening in this chronic disease earlier rather than later,” said Stacy A. Brethauer, MD, professor of surgery at the Ohio State University, Columbus, in a presentation about new standards for bariatric surgery at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Bariatric treatment “should be offered after nonsurgical [weight-loss] therapy has failed,” he said. “That’s not where you stop. You continue to escalate as you would for heart disease or cancer.”

As Dr. Brethauer noted, research suggests that all categories of obesity – including so-called class 1 obesity (defined as a BMI from 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2) – boost the risk of multiple diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, pulmonary embolism, gallbladder disease, several types of cancer, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain.

“There is no question that class 1 obesity is clearly putting people at risk,” he said. “Ultimately, you can conclude from all this evidence that class 1 is a chronic disease, and it deserves to be treated effectively.”

There are, of course, various nonsurgical treatments for obesity, including diet and exercise and pharmacotherapy. However, systematic reviews have found that people find it extremely difficult to keep the weight off after 1 year regardless of the strategy they adopt.

Beyond a year, Dr. Brethauer said, “you get poor maintenance of weight control, and you get poor control of metabolic burden. You don’t have a durable efficacy.”

In the past, bariatric surgery wasn’t considered an option for patients with class 1 obesity. It’s traditionally been reserved for patients with BMIs at or above 35 kg/m2. But this standard has evolved in recent years.

In 2018, Dr. Brethauer coauthored an updated position statement by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery that encouraged bariatric surgery in certain mildly obese patients.

“For most people with class I obesity,” the statement on bariatric surgery states, “it is clear that the nonsurgical group of therapies will not provide a durable solution to their disease of obesity.”

The statement went on to say that “surgical intervention should be considered after failure of nonsurgical treatments” in the class 1 population.

Bariatric surgery in the class 1 population does more than reduce obesity, Dr. Brethauer said. “Over the last 5 years or so, a large body of literature has emerged,” he said, and both systematic reviews and randomized trails have shown significant postsurgery improvements in comorbidities such as diabetes.

“It’s important to emphasize that these patients don’t become underweight,” he said. “The body finds a healthy set point. They don’t become underweight or malnourished because you’re operating on a lower-weight group.”

Are weight-loss operations safe in class 1 patients? The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery statement says that research has found “bariatric surgery is associated with modest morbidity and very low mortality in patients with class I obesity.”

In fact, Dr. Brethauer said, the mortality rate in this population is “less than gallbladder surgery, less than hip surgery, less than hysterectomy, less than knee surgery – operations people are being referred for and undergoing all the time.”

He added: “The case can be made very clearly based on this data that these operations are safe in this patient population. Not only are they safe, they have durable and significant impact on comorbidities.”

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Brethauer discloses relationships with Medtronic (speaker) and GI Windows (consultant).

Review the AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper, which provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at http://ow.ly/WV8l30oeyYv.

LAS VEGAS – Once reserved for the most obese patients, bariatric surgery is on the road to becoming an option for millions of Americans who are just a step beyond overweight, even those with a body mass index as low as 30 kg/m2.

In regard to patients with lower levels of obesity, “we should be intervening in this chronic disease earlier rather than later,” said Stacy A. Brethauer, MD, professor of surgery at the Ohio State University, Columbus, in a presentation about new standards for bariatric surgery at the 2019 Annual Minimally Invasive Surgery Symposium by Global Academy for Medical Education.

Bariatric treatment “should be offered after nonsurgical [weight-loss] therapy has failed,” he said. “That’s not where you stop. You continue to escalate as you would for heart disease or cancer.”

As Dr. Brethauer noted, research suggests that all categories of obesity – including so-called class 1 obesity (defined as a BMI from 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2) – boost the risk of multiple diseases, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, asthma, pulmonary embolism, gallbladder disease, several types of cancer, osteoarthritis, and chronic back pain.

“There is no question that class 1 obesity is clearly putting people at risk,” he said. “Ultimately, you can conclude from all this evidence that class 1 is a chronic disease, and it deserves to be treated effectively.”

There are, of course, various nonsurgical treatments for obesity, including diet and exercise and pharmacotherapy. However, systematic reviews have found that people find it extremely difficult to keep the weight off after 1 year regardless of the strategy they adopt.

Beyond a year, Dr. Brethauer said, “you get poor maintenance of weight control, and you get poor control of metabolic burden. You don’t have a durable efficacy.”

In the past, bariatric surgery wasn’t considered an option for patients with class 1 obesity. It’s traditionally been reserved for patients with BMIs at or above 35 kg/m2. But this standard has evolved in recent years.

In 2018, Dr. Brethauer coauthored an updated position statement by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery that encouraged bariatric surgery in certain mildly obese patients.

“For most people with class I obesity,” the statement on bariatric surgery states, “it is clear that the nonsurgical group of therapies will not provide a durable solution to their disease of obesity.”

The statement went on to say that “surgical intervention should be considered after failure of nonsurgical treatments” in the class 1 population.

Bariatric surgery in the class 1 population does more than reduce obesity, Dr. Brethauer said. “Over the last 5 years or so, a large body of literature has emerged,” he said, and both systematic reviews and randomized trails have shown significant postsurgery improvements in comorbidities such as diabetes.

“It’s important to emphasize that these patients don’t become underweight,” he said. “The body finds a healthy set point. They don’t become underweight or malnourished because you’re operating on a lower-weight group.”

Are weight-loss operations safe in class 1 patients? The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery statement says that research has found “bariatric surgery is associated with modest morbidity and very low mortality in patients with class I obesity.”

In fact, Dr. Brethauer said, the mortality rate in this population is “less than gallbladder surgery, less than hip surgery, less than hysterectomy, less than knee surgery – operations people are being referred for and undergoing all the time.”

He added: “The case can be made very clearly based on this data that these operations are safe in this patient population. Not only are they safe, they have durable and significant impact on comorbidities.”

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Brethauer discloses relationships with Medtronic (speaker) and GI Windows (consultant).

Review the AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper, which provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at http://ow.ly/WV8l30oeyYv.

REPORTING FROM MISS

CPAP use associated with greater weight loss in obese patients with sleep apnea

NEW ORLEANS – Contrary to previously published data suggesting continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) produces weight gain in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), new study findings presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society provided data supporting the exact opposite conclusion.

“We think the data are strong enough to conclude that combining CPAP with a weight-loss program should be considered for all OSA patients. The weight-loss advantage is substantial,” reported Yuanjie Mao, MD, PhD, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Both weight loss and CPAP have been shown to be effective for the treatment of OSA, but concern that CPAP produces a counterproductive gain in weight was raised by findings in a meta-analysis in which CPAP was associated with increased body mass index (Thorax. 2015 Mar;70:258-64). As a result of that finding, some guidelines subsequently advised intensifying a weight-loss program at the time that CPAP is initiated to mitigate the weight gain effect, according to Dr. Mao. However, he noted that prospective data were never collected, so a causal relationship was never proven. Now, his data support the opposite conclusion.

In the more recent study, 300 patients who had participated in an intensive weight-loss program at his institution were divided into three groups: OSA patients who had been treated with CPAP, symptomatic OSA patients who had not been treated with CPAP, and asymptomatic OSA patients not treated with CPAP. They were compared retrospectively for weight change over a 16-week period.

“This was a very simple study,” said Dr. Mao, who explained that several exclusions, such as thyroid dysfunction, active infection, and uncontrolled diabetes, were used to reduce variables that might also affect weight change. At the end of 16 weeks, the median absolute weight loss in the CPAP group was 26.7 lb (12.1 kg), compared with 21 lb (9.5 kg) for the symptomatic OSA group and 19.2 lb (8.7 kg) for the asymptomatic OSA group. The weight loss was significantly greater for the CPAP group (P less than .01), compared with either of the other two groups, but not significantly different between the groups that were not treated with CPAP.

“The differences remained significant after adjusting for baseline BMI [body mass index], age, and gender,” Dr. Mao reported.

Asked why his data contradicted the previously reported data, Dr. Mao said that the previous studies were not evaluating CPAP in the context of a weight-loss program. He contends that when CPAP is combined with a rigorous weight-reduction regimen, there is an additive benefit from CPAP.

According to Dr. Mao, these data bring the value of CPAP for weight loss full circle. Before publication of the 2015 meta-analysis, it was widely assumed that CPAP helped with weight loss based on the expectation that better sleep quality would increase daytime activity. However, in the absence of strong data confirming that effect, Dr. Mao believes the unexpected results of the 2015 study easily pushed the pendulum in the opposite direction.

“The conclusion that CPAP increases weight was drawn from studies not designed to evaluate a weight-loss effect in those participating in a weight-loss program,” Dr. Mao explained. His study suggests that it is this combination that is important. He believes the observed effect from better sleep quality associated with CPAP is not necessarily related to better daytime function alone.

“Patients who sleep well also have more favorable diurnal changes in factors that might be important to weight change, such as leptin resistance and hormonal secretion,” he said. Although more work is needed to determine whether these purported mechanisms are important, he thinks his study has an immediate clinical message.

“Patients with OSA who are prescribed weight loss should also be considered for CPAP for the goal of weight loss,” Dr. Mao said. “We think this therapy should be started right away.”

SOURCE: Mao Y et al. ENDO 2019, Session SAT-095.

NEW ORLEANS – Contrary to previously published data suggesting continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) produces weight gain in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), new study findings presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society provided data supporting the exact opposite conclusion.

“We think the data are strong enough to conclude that combining CPAP with a weight-loss program should be considered for all OSA patients. The weight-loss advantage is substantial,” reported Yuanjie Mao, MD, PhD, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Both weight loss and CPAP have been shown to be effective for the treatment of OSA, but concern that CPAP produces a counterproductive gain in weight was raised by findings in a meta-analysis in which CPAP was associated with increased body mass index (Thorax. 2015 Mar;70:258-64). As a result of that finding, some guidelines subsequently advised intensifying a weight-loss program at the time that CPAP is initiated to mitigate the weight gain effect, according to Dr. Mao. However, he noted that prospective data were never collected, so a causal relationship was never proven. Now, his data support the opposite conclusion.

In the more recent study, 300 patients who had participated in an intensive weight-loss program at his institution were divided into three groups: OSA patients who had been treated with CPAP, symptomatic OSA patients who had not been treated with CPAP, and asymptomatic OSA patients not treated with CPAP. They were compared retrospectively for weight change over a 16-week period.

“This was a very simple study,” said Dr. Mao, who explained that several exclusions, such as thyroid dysfunction, active infection, and uncontrolled diabetes, were used to reduce variables that might also affect weight change. At the end of 16 weeks, the median absolute weight loss in the CPAP group was 26.7 lb (12.1 kg), compared with 21 lb (9.5 kg) for the symptomatic OSA group and 19.2 lb (8.7 kg) for the asymptomatic OSA group. The weight loss was significantly greater for the CPAP group (P less than .01), compared with either of the other two groups, but not significantly different between the groups that were not treated with CPAP.

“The differences remained significant after adjusting for baseline BMI [body mass index], age, and gender,” Dr. Mao reported.

Asked why his data contradicted the previously reported data, Dr. Mao said that the previous studies were not evaluating CPAP in the context of a weight-loss program. He contends that when CPAP is combined with a rigorous weight-reduction regimen, there is an additive benefit from CPAP.

According to Dr. Mao, these data bring the value of CPAP for weight loss full circle. Before publication of the 2015 meta-analysis, it was widely assumed that CPAP helped with weight loss based on the expectation that better sleep quality would increase daytime activity. However, in the absence of strong data confirming that effect, Dr. Mao believes the unexpected results of the 2015 study easily pushed the pendulum in the opposite direction.

“The conclusion that CPAP increases weight was drawn from studies not designed to evaluate a weight-loss effect in those participating in a weight-loss program,” Dr. Mao explained. His study suggests that it is this combination that is important. He believes the observed effect from better sleep quality associated with CPAP is not necessarily related to better daytime function alone.

“Patients who sleep well also have more favorable diurnal changes in factors that might be important to weight change, such as leptin resistance and hormonal secretion,” he said. Although more work is needed to determine whether these purported mechanisms are important, he thinks his study has an immediate clinical message.

“Patients with OSA who are prescribed weight loss should also be considered for CPAP for the goal of weight loss,” Dr. Mao said. “We think this therapy should be started right away.”

SOURCE: Mao Y et al. ENDO 2019, Session SAT-095.

NEW ORLEANS – Contrary to previously published data suggesting continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) produces weight gain in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), new study findings presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society provided data supporting the exact opposite conclusion.

“We think the data are strong enough to conclude that combining CPAP with a weight-loss program should be considered for all OSA patients. The weight-loss advantage is substantial,” reported Yuanjie Mao, MD, PhD, of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

Both weight loss and CPAP have been shown to be effective for the treatment of OSA, but concern that CPAP produces a counterproductive gain in weight was raised by findings in a meta-analysis in which CPAP was associated with increased body mass index (Thorax. 2015 Mar;70:258-64). As a result of that finding, some guidelines subsequently advised intensifying a weight-loss program at the time that CPAP is initiated to mitigate the weight gain effect, according to Dr. Mao. However, he noted that prospective data were never collected, so a causal relationship was never proven. Now, his data support the opposite conclusion.

In the more recent study, 300 patients who had participated in an intensive weight-loss program at his institution were divided into three groups: OSA patients who had been treated with CPAP, symptomatic OSA patients who had not been treated with CPAP, and asymptomatic OSA patients not treated with CPAP. They were compared retrospectively for weight change over a 16-week period.

“This was a very simple study,” said Dr. Mao, who explained that several exclusions, such as thyroid dysfunction, active infection, and uncontrolled diabetes, were used to reduce variables that might also affect weight change. At the end of 16 weeks, the median absolute weight loss in the CPAP group was 26.7 lb (12.1 kg), compared with 21 lb (9.5 kg) for the symptomatic OSA group and 19.2 lb (8.7 kg) for the asymptomatic OSA group. The weight loss was significantly greater for the CPAP group (P less than .01), compared with either of the other two groups, but not significantly different between the groups that were not treated with CPAP.

“The differences remained significant after adjusting for baseline BMI [body mass index], age, and gender,” Dr. Mao reported.

Asked why his data contradicted the previously reported data, Dr. Mao said that the previous studies were not evaluating CPAP in the context of a weight-loss program. He contends that when CPAP is combined with a rigorous weight-reduction regimen, there is an additive benefit from CPAP.

According to Dr. Mao, these data bring the value of CPAP for weight loss full circle. Before publication of the 2015 meta-analysis, it was widely assumed that CPAP helped with weight loss based on the expectation that better sleep quality would increase daytime activity. However, in the absence of strong data confirming that effect, Dr. Mao believes the unexpected results of the 2015 study easily pushed the pendulum in the opposite direction.

“The conclusion that CPAP increases weight was drawn from studies not designed to evaluate a weight-loss effect in those participating in a weight-loss program,” Dr. Mao explained. His study suggests that it is this combination that is important. He believes the observed effect from better sleep quality associated with CPAP is not necessarily related to better daytime function alone.

“Patients who sleep well also have more favorable diurnal changes in factors that might be important to weight change, such as leptin resistance and hormonal secretion,” he said. Although more work is needed to determine whether these purported mechanisms are important, he thinks his study has an immediate clinical message.

“Patients with OSA who are prescribed weight loss should also be considered for CPAP for the goal of weight loss,” Dr. Mao said. “We think this therapy should be started right away.”

SOURCE: Mao Y et al. ENDO 2019, Session SAT-095.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2019

First RCT with aromatase inhibitor for male hypogonadism shows promise

NEW ORLEANS – In obese men with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, an experimental aromatase inhibitor (Ai) normalized testosterone, seemed to improve sperm function, and was not associated with any significant adverse safety signals, according to findings presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Unlike testosterone therapy, “leflutrozole was associated with positive effects on semen fertility parameters, such as semen volume and concentration,” reported Thomas Hugh Jones, MD, FRCP, of the Centre for Diabetes and Endocrinology, Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, and the department of oncology and metabolism, University of Sheffield Medical School, both in England.

Although the impact of the experimental aromatase inhibitor leflutrozole on parameters of semen function was an exploratory analysis in this multicenter, placebo-controlled study, it is particularly noteworthy because it addresses one of the weaknesses of testosterone replacement, which is often the first choice in treating hypogonadism, Dr. Jones said.

“Testosterone replacement frequently results in negative feedback suppression of follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone so that along with lower sperm counts, these men have significant problems with fertility,” he explained.

In this phase 2, double-blind, randomized trial, 271 men with hypogonadism were randomized to placebo or to leflutrozole in a dose of 0.1 mg, 0.3 mg, or 1.0 mg taken orally once weekly. All patients had a serum testosterone level of less than 300 ng/dL at entry. The median body mass index was 38 kg/m2, and the average age was 50.9 years.

Results were presented after 24 weeks of treatment, but the blinded study continued for an additional 24 weeks.

Normalization of testosterone, defined as a level between 300 and 1,000 ng/dL, was the primary endpoint. The mean testosterone levels were essentially unchanged in the placebo group during the first 24-week phase of the study, but they climbed to means of 458 ng/dL in the 0.1-mg group, 512 ng/dL in the 0.3-mg group, and 586 ng/dL in the 1.0-mg group.

“Overall, 75% were in the normal range, but it reached 90% in the groups taking the two higher doses,” Dr. Jones reported. Testosterone levels never exceeded 1,500 ng/d.

For the effect on FSH and LH, which were secondary endpoints, both were increased in a dose-dependent manner at 12 and 20 weeks (P less than .001 for the highest dose relative to placebo).

For the semen analysis, also conducted at 12 and 20 weeks, all three doses were associated with a numerical increase in sperm count relative to placebo, with the highest dose achieving significant improvements in semen volume (P = .006), semen concentration (P = .01), and total motile sperm count (P = .03), Dr. Jones reported.

“The 48-week analysis has just been completed, and these types of improvements have been persistent,” Dr. Jones said in reference to the increase in sex hormones as well as measures of sperm function. Although he did not present the 48-week results in detail, he disclosed that this longer follow-up also supported favorable effects on bone density, which is among several prespecified substudies being performed.

Leflutrozole, which is chemically related to letrozole, has been well tolerated at the doses studied. An increase in hematocrit consistent with the rise in testosterone was observed, but Dr. Jones reported that there are no significant safety issues identified so far.

Aromatase inhibitors have been used off label to treat hypogonadism, but this is the first randomized controlled trial for this indication, Dr. Jones said.

Although leflutrozole was used in this study at far lower doses than the aromatase inhibitors currently available for treatment of breast cancer, it might provide an advance for a challenging condition, according to Dr. Jones. He did not speculate when a phase 3 registration trial might start, but he did say that the promise of this agent warrants further development.

Dr. Jones reported a financial relationship with Mereo BioPharma, the sponsor of this trial.

Source: Jones et al. ENDO 2019, Session OR18-4.

NEW ORLEANS – In obese men with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, an experimental aromatase inhibitor (Ai) normalized testosterone, seemed to improve sperm function, and was not associated with any significant adverse safety signals, according to findings presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Unlike testosterone therapy, “leflutrozole was associated with positive effects on semen fertility parameters, such as semen volume and concentration,” reported Thomas Hugh Jones, MD, FRCP, of the Centre for Diabetes and Endocrinology, Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, and the department of oncology and metabolism, University of Sheffield Medical School, both in England.

Although the impact of the experimental aromatase inhibitor leflutrozole on parameters of semen function was an exploratory analysis in this multicenter, placebo-controlled study, it is particularly noteworthy because it addresses one of the weaknesses of testosterone replacement, which is often the first choice in treating hypogonadism, Dr. Jones said.

“Testosterone replacement frequently results in negative feedback suppression of follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone so that along with lower sperm counts, these men have significant problems with fertility,” he explained.

In this phase 2, double-blind, randomized trial, 271 men with hypogonadism were randomized to placebo or to leflutrozole in a dose of 0.1 mg, 0.3 mg, or 1.0 mg taken orally once weekly. All patients had a serum testosterone level of less than 300 ng/dL at entry. The median body mass index was 38 kg/m2, and the average age was 50.9 years.

Results were presented after 24 weeks of treatment, but the blinded study continued for an additional 24 weeks.

Normalization of testosterone, defined as a level between 300 and 1,000 ng/dL, was the primary endpoint. The mean testosterone levels were essentially unchanged in the placebo group during the first 24-week phase of the study, but they climbed to means of 458 ng/dL in the 0.1-mg group, 512 ng/dL in the 0.3-mg group, and 586 ng/dL in the 1.0-mg group.

“Overall, 75% were in the normal range, but it reached 90% in the groups taking the two higher doses,” Dr. Jones reported. Testosterone levels never exceeded 1,500 ng/d.

For the effect on FSH and LH, which were secondary endpoints, both were increased in a dose-dependent manner at 12 and 20 weeks (P less than .001 for the highest dose relative to placebo).

For the semen analysis, also conducted at 12 and 20 weeks, all three doses were associated with a numerical increase in sperm count relative to placebo, with the highest dose achieving significant improvements in semen volume (P = .006), semen concentration (P = .01), and total motile sperm count (P = .03), Dr. Jones reported.

“The 48-week analysis has just been completed, and these types of improvements have been persistent,” Dr. Jones said in reference to the increase in sex hormones as well as measures of sperm function. Although he did not present the 48-week results in detail, he disclosed that this longer follow-up also supported favorable effects on bone density, which is among several prespecified substudies being performed.

Leflutrozole, which is chemically related to letrozole, has been well tolerated at the doses studied. An increase in hematocrit consistent with the rise in testosterone was observed, but Dr. Jones reported that there are no significant safety issues identified so far.

Aromatase inhibitors have been used off label to treat hypogonadism, but this is the first randomized controlled trial for this indication, Dr. Jones said.

Although leflutrozole was used in this study at far lower doses than the aromatase inhibitors currently available for treatment of breast cancer, it might provide an advance for a challenging condition, according to Dr. Jones. He did not speculate when a phase 3 registration trial might start, but he did say that the promise of this agent warrants further development.

Dr. Jones reported a financial relationship with Mereo BioPharma, the sponsor of this trial.

Source: Jones et al. ENDO 2019, Session OR18-4.

NEW ORLEANS – In obese men with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, an experimental aromatase inhibitor (Ai) normalized testosterone, seemed to improve sperm function, and was not associated with any significant adverse safety signals, according to findings presented at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Unlike testosterone therapy, “leflutrozole was associated with positive effects on semen fertility parameters, such as semen volume and concentration,” reported Thomas Hugh Jones, MD, FRCP, of the Centre for Diabetes and Endocrinology, Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, and the department of oncology and metabolism, University of Sheffield Medical School, both in England.

Although the impact of the experimental aromatase inhibitor leflutrozole on parameters of semen function was an exploratory analysis in this multicenter, placebo-controlled study, it is particularly noteworthy because it addresses one of the weaknesses of testosterone replacement, which is often the first choice in treating hypogonadism, Dr. Jones said.

“Testosterone replacement frequently results in negative feedback suppression of follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone so that along with lower sperm counts, these men have significant problems with fertility,” he explained.

In this phase 2, double-blind, randomized trial, 271 men with hypogonadism were randomized to placebo or to leflutrozole in a dose of 0.1 mg, 0.3 mg, or 1.0 mg taken orally once weekly. All patients had a serum testosterone level of less than 300 ng/dL at entry. The median body mass index was 38 kg/m2, and the average age was 50.9 years.

Results were presented after 24 weeks of treatment, but the blinded study continued for an additional 24 weeks.

Normalization of testosterone, defined as a level between 300 and 1,000 ng/dL, was the primary endpoint. The mean testosterone levels were essentially unchanged in the placebo group during the first 24-week phase of the study, but they climbed to means of 458 ng/dL in the 0.1-mg group, 512 ng/dL in the 0.3-mg group, and 586 ng/dL in the 1.0-mg group.

“Overall, 75% were in the normal range, but it reached 90% in the groups taking the two higher doses,” Dr. Jones reported. Testosterone levels never exceeded 1,500 ng/d.

For the effect on FSH and LH, which were secondary endpoints, both were increased in a dose-dependent manner at 12 and 20 weeks (P less than .001 for the highest dose relative to placebo).

For the semen analysis, also conducted at 12 and 20 weeks, all three doses were associated with a numerical increase in sperm count relative to placebo, with the highest dose achieving significant improvements in semen volume (P = .006), semen concentration (P = .01), and total motile sperm count (P = .03), Dr. Jones reported.

“The 48-week analysis has just been completed, and these types of improvements have been persistent,” Dr. Jones said in reference to the increase in sex hormones as well as measures of sperm function. Although he did not present the 48-week results in detail, he disclosed that this longer follow-up also supported favorable effects on bone density, which is among several prespecified substudies being performed.

Leflutrozole, which is chemically related to letrozole, has been well tolerated at the doses studied. An increase in hematocrit consistent with the rise in testosterone was observed, but Dr. Jones reported that there are no significant safety issues identified so far.