User login

Bariatric surgery leads to less improvement in black patients

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

The AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/practice-updates/obesity-practice-guide.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

The AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/practice-updates/obesity-practice-guide.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

The AGA Practice guide on Obesity and Weight management, Education and Resources (POWER) white paper provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/practice-updates/obesity-practice-guide.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Black patients who underwent bariatric surgery suffered more overall complications and reported a lower quality of life than white patients.

Major finding: The rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02).

Study details: A matched cohort study of 14,210 patients, half black and half white, who underwent a primary bariatric operation in Michigan between June 2006 and January 2017.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the collaborative’s executive committee chair.

Source: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

Bariatric surgery leads to less improvement in black patients

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

The well-documented disparities between black and white patients after bariatric surgery are brought back to the forefront via to this study from Wood et al., according to Brian Hodgens, MD, and Kenric M. Murayama, MD, of the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Some of the findings hint at the cultural differences that permeate the time before and after a surgery like this: In particular, they highlighted how black patients were more likely to report good or very good quality of life before surgery but less likely after. This could be related to a “difference in perceptions of obesity by black patients,” where they are more hesitant to pursue the surgery than their white counterparts, Dr. Hodgens and Dr. Murayama wrote.

More work is needed, they added, but “this study and others like it can better equip practicing bariatric surgeons to educate themselves and patients on expectations before and after bariatric surgery.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial ( JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 1 0.1001/jamasurg.2019.0067 ). Dr. Murayama reported receiving personal fees from Medtronic outside the submitted work.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

“Per this analysis, there are significant racial disparities in perioperative outcomes, weight loss, and quality of life after bariatric surgery,” wrote lead author Michael H. Wood, MD, of Wayne State University, Detroit, and his coauthors, adding that, “while biological differences may explain some of the disparity in outcomes, environmental, social, and behavioral factors likely play a role.” The study was published online in JAMA Surgery.

This study reviewed data from 14,210 participants in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a state-wide consortium and clinical registry of bariatric surgery patients. Matching cohorts were established for black (n = 7,105) and white (n = 7,105) patients who underwent a primary bariatric operation (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, or adjustable gastric banding) between June 2006 and January 2017. The only significant differences between cohorts – clarified as “never more than 1 or 2 percentage points” – were in regard to income brackets and procedure type.

At 30-day follow-up, the rate of overall complications was higher in black patients (628, 8.8%) than in white patients (481, 6.8%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.17-1.51; P = .02), as was the length of stay (mean, 2.2 days vs. 1.9 days; aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.20-0.40; P less than .001). Black patients also had a higher rate of both ED visits (541 [11.6%] vs. 826 [7.6%]; aOR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.43-1.79; P less than .001) and readmissions (414 [5.8%] vs. 245 [3.5%]; aOR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.47-2.03; P less than .001).

In addition, at 1-year follow-up, black patients had a lower mean weight loss (32.0 kg vs. 38.3 kg; P less than .001) and percentage of total weight loss (26% vs. 29%; P less than .001) compared with white patients. And though black patients were more likely than white patients to report a high quality of life before surgery (2,672 [49.5%] vs. 2,354 [41.4%]; P less than .001), they were less likely to do so 1 year afterward (1,379 [87.2%] vs. 2,133 [90.4%]; P = .002).

The coauthors acknowledged the limitations of their study, including potential unmeasured factors between cohorts such as disease duration or severity. They also noted that a wider time horizon than 30 days post surgery could have altered the results, although “serious adverse events and resource use tend to be highest within the first month after surgery, and we anticipate that this effect would have been negligible.”

The study was funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network. Dr. Wood reported no conflicts of interest. Three of his coauthors reported receiving salary support from Blue Cross Blue Shield Michigan/Blue Care Network for their work with the MBSC, and one other coauthor reported receiving an honorarium for being the MBSC’s executive committee chair.

SOURCE: Wood MH et al. JAMA Surg. 2019 Mar 6. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0029.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Sudden-onset rash on the trunk and limbs • morbid obesity • family history of diabetes mellitus • Dx?

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.

His medical history was unremarkable except for morbid obesity. He did not drink alcohol regularly and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the rash. He had no family history of hyperlipidemia, but his mother had a history of diabetes mellitus.

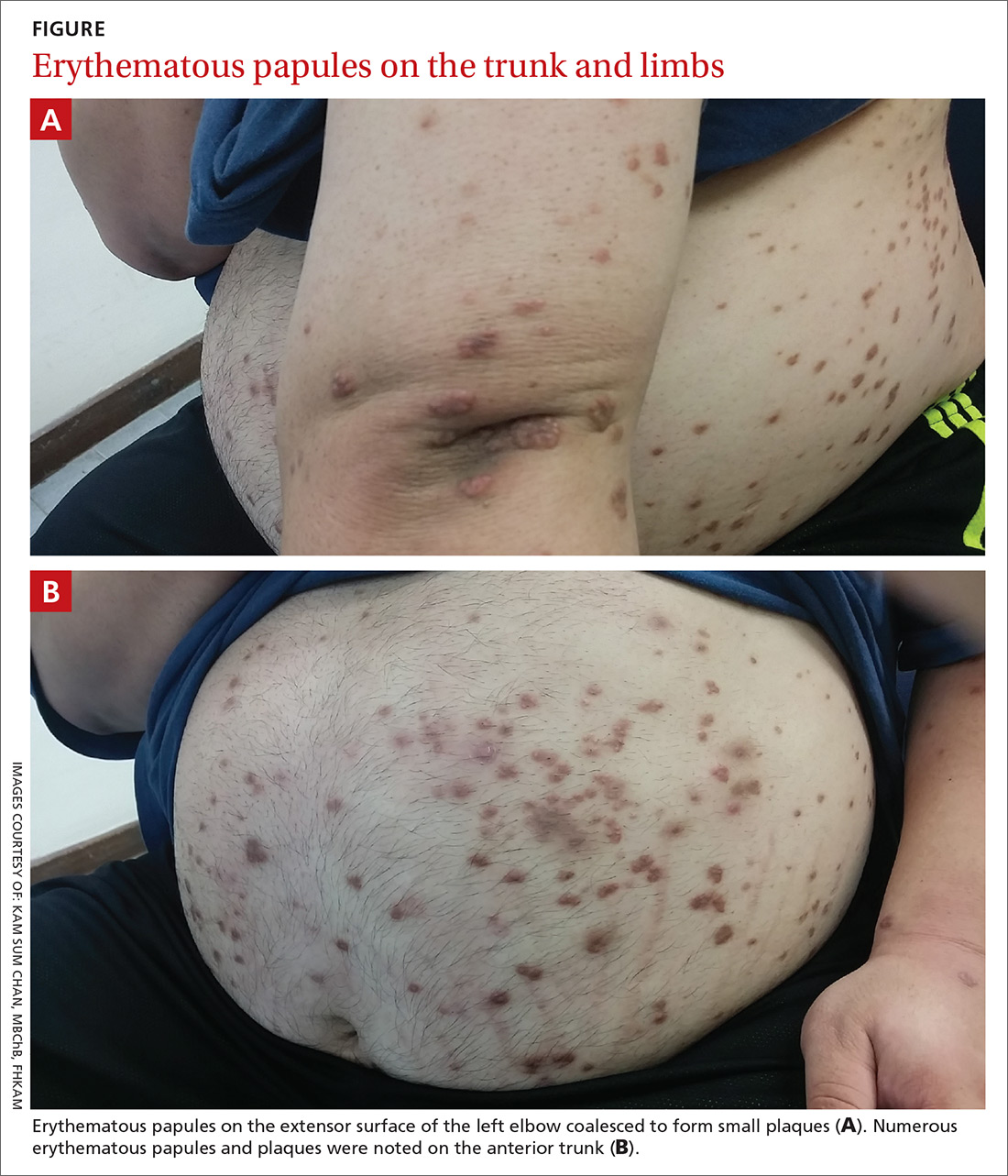

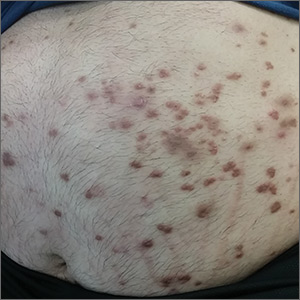

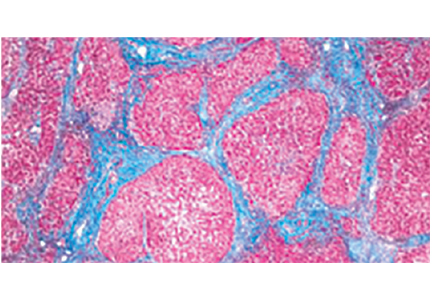

Physical examination showed numerous discrete erythematous papules with a creamy center on his trunk and his arms and legs. The lesions were more numerous on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. Some of the papules coalesced to form small plaques (FIGURE). There was no scaling, and the lesions were firm in texture. The patient’s face was spared, and there was no mucosal involvement. The patient was otherwise systemically well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the morphology, distribution, and abrupt onset of the diffuse nonpruritic papules in this morbidly obese (but otherwise systemically well) middle-aged man, a clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma was suspected. Subsequent blood testing revealed an elevated serum triglyceride level of 47.8 mmol/L (reference range, <1.7 mmol/L), elevated serum total cholesterol of 7.1 mmol/L (reference range, <6.2 mmol/L), and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 0.7 mmol/L (reference range, >1 mmol/L in men). He also had an elevated fasting serum glucose level of 12.9 mmol/L (reference range, 3.9–5.6 mmol/L) and an elevated hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 10.9%.

Subsequent thyroid, liver, and renal function tests were normal, but the patient had heavy proteinuria, with an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 355.6 mg/mmol (reference range, ≤2.5 mg/mmol). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, who confirmed the clinical diagnosis without the need for a skin biopsy.

DISCUSSION

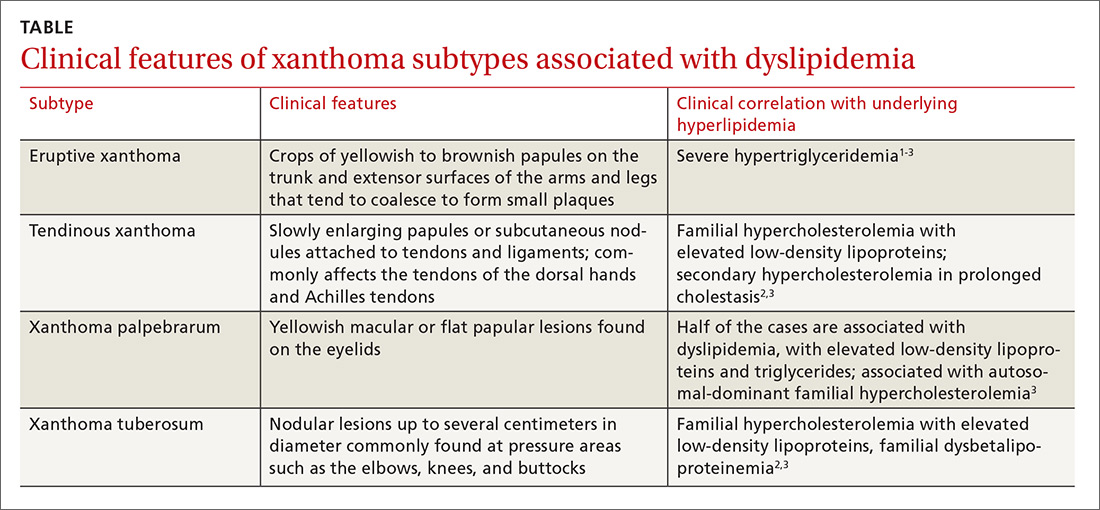

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by an abrupt onset of crops of multiple yellowish to brownish papules that can coalesce into small plaques. The lesions can be generalized, but tend to be more densely distributed on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, buttocks, and thighs.5 Eruptive xanthoma often is associated with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be primary—as a result of a genetic defect caused by familial hypertriglyceridemia—or secondary, associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, and drugs like estrogen replacement therapies, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin.6 Pruritus and tenderness may or may not be present, and the Köbner phenomenon may occur.7

Continue to: The differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for eruptive xanthoma includes xanthoma disseminatum, non–Langerhans cell histiocytoses (eg, generalized eruptive histiocytosis), and cutaneous mastocytosis.1

Xanthoma disseminatum is an extremely rare, but benign, disorder of non–Langerhans cell origin. The average age of onset is older than 40 years. The rash consists of multiple red-yellow papules and nodules that most commonly present in flexural areas. Forty percent to 60% of patients have mucosal involvement, and rarely the central nervous system is involved.8

Generalized eruptive histiocytosis is another rare non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis that occurs mainly in adults and is characterized by widespread, symmetric, red-brown papules on the trunk, arms, and legs, and rarely the mucous membranes.9

Cutaneous mastocytosis, especially xanthelasmoid mastocytosis, consists of multiple pruritic, yellowish, papular or nodular lesions that may mimic eruptive xanthoma. It occurs mainly in children and rarely in adults.10

Confirming the diagnosis, initiating treatment

The diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma can be confirmed by skin biopsy if other differential diagnoses cannot be ruled out or the lesions do not resolve with treatment. Skin biopsy will reveal lipid-laden macrophages (known as foam cells) deposited in the dermis.7

Continue to: Treatment of eruptive xanthoma

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves management of the underlying causes of the condition. In most cases, dietary control, intensive triglyceride-lowering therapies, and treatment of other secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia result in complete resolution of the lesions within several weeks.5

Our patient’s outcome

Our patient’s sudden-onset rash alerted us to the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, and heavy proteinuria, which he was not aware of previously. We counselled him about stringent low-sugar, low-lipid diet control and exercise, and we started him on metformin and gemfibrozil. He was referred to an internal medicine specialist for further assessment and management of his severe hypertriglyceridemia and heavy proteinuria.

The rash started to wane 1 month after the patient started the metformin and gemfibrozil, and his drug regimen was changed to combination therapy with metformin/glimepiride and fenofibrate/simvastatin 6 weeks later when he was seen in the medical specialty clinic. Fundus photography performed 1 month after starting oral antidiabetic therapy showed no diabetic retinopathy or lipemia retinalis.

After 3 months of treatment, his serum triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c levels dropped to 3.8 mmol/L and 8.7%, respectively. The rash also resolved considerably, with only residual papules on the abdomen. This rapid clinical response to treatment of the underlying hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes further supported the clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

THE TAKEAWAY

Eruptive xanthoma is relatively rare, but it is important for family physicians to recognize this clinical presentation as a potential indicator of severe hypertriglyceridemia. Recognizing hypertriglyceridemia early is important, as it can be associated with an increased risk for acute pancreatitis. Moreover, eruptive xanthoma might be the sole presenting symptom of underlying diabetes mellitus or familial hyperlipidemia, both of which can lead to a significant increase in cardiovascular risk if uncontrolled.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chan Kam Sum, MBChB, FRACGP, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Out-patient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon, Hong Kong; cks048@ha.org.hk

1. Tang WK. Eruptive xanthoma. [case reports]. Hong Kong Dermatol Venereol Bull. 2001;9:172-175.

2. Frew J, Murrell D, Haber R. Fifty shades of yellow: a review of the xanthodermatoses. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1109-1123.

3. Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

4. Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:157.

5. Holsinger JM, Campbell SM, Witman P. Multiple erythematous-yellow, dome-shaped papules. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:517.

6. Loeckermann S, Braun-Falco M. Eruptive xanthomas in association with metabolic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:565-566.

7. Merola JF, Mengden SJ, Soldano A, et al. Eruptive xanthomas. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

8. Park M, Boone B, Devas S. Xanthoma disseminatum: case report and mini-review of the literature. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:150-154.

9. Attia A, Seleit I, El Badawy N, et al. Photoletter to the editor: generalized eruptive histiocytoma. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:53-55.

10. Nabavi NS, Nejad MH, Feli S, et al. Adult onset of xanthelasmoid mastocytosis: report of a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:468.

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.

His medical history was unremarkable except for morbid obesity. He did not drink alcohol regularly and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the rash. He had no family history of hyperlipidemia, but his mother had a history of diabetes mellitus.

Physical examination showed numerous discrete erythematous papules with a creamy center on his trunk and his arms and legs. The lesions were more numerous on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. Some of the papules coalesced to form small plaques (FIGURE). There was no scaling, and the lesions were firm in texture. The patient’s face was spared, and there was no mucosal involvement. The patient was otherwise systemically well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the morphology, distribution, and abrupt onset of the diffuse nonpruritic papules in this morbidly obese (but otherwise systemically well) middle-aged man, a clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma was suspected. Subsequent blood testing revealed an elevated serum triglyceride level of 47.8 mmol/L (reference range, <1.7 mmol/L), elevated serum total cholesterol of 7.1 mmol/L (reference range, <6.2 mmol/L), and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 0.7 mmol/L (reference range, >1 mmol/L in men). He also had an elevated fasting serum glucose level of 12.9 mmol/L (reference range, 3.9–5.6 mmol/L) and an elevated hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 10.9%.

Subsequent thyroid, liver, and renal function tests were normal, but the patient had heavy proteinuria, with an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 355.6 mg/mmol (reference range, ≤2.5 mg/mmol). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, who confirmed the clinical diagnosis without the need for a skin biopsy.

DISCUSSION

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by an abrupt onset of crops of multiple yellowish to brownish papules that can coalesce into small plaques. The lesions can be generalized, but tend to be more densely distributed on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, buttocks, and thighs.5 Eruptive xanthoma often is associated with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be primary—as a result of a genetic defect caused by familial hypertriglyceridemia—or secondary, associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, and drugs like estrogen replacement therapies, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin.6 Pruritus and tenderness may or may not be present, and the Köbner phenomenon may occur.7

Continue to: The differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for eruptive xanthoma includes xanthoma disseminatum, non–Langerhans cell histiocytoses (eg, generalized eruptive histiocytosis), and cutaneous mastocytosis.1

Xanthoma disseminatum is an extremely rare, but benign, disorder of non–Langerhans cell origin. The average age of onset is older than 40 years. The rash consists of multiple red-yellow papules and nodules that most commonly present in flexural areas. Forty percent to 60% of patients have mucosal involvement, and rarely the central nervous system is involved.8

Generalized eruptive histiocytosis is another rare non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis that occurs mainly in adults and is characterized by widespread, symmetric, red-brown papules on the trunk, arms, and legs, and rarely the mucous membranes.9

Cutaneous mastocytosis, especially xanthelasmoid mastocytosis, consists of multiple pruritic, yellowish, papular or nodular lesions that may mimic eruptive xanthoma. It occurs mainly in children and rarely in adults.10

Confirming the diagnosis, initiating treatment

The diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma can be confirmed by skin biopsy if other differential diagnoses cannot be ruled out or the lesions do not resolve with treatment. Skin biopsy will reveal lipid-laden macrophages (known as foam cells) deposited in the dermis.7

Continue to: Treatment of eruptive xanthoma

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves management of the underlying causes of the condition. In most cases, dietary control, intensive triglyceride-lowering therapies, and treatment of other secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia result in complete resolution of the lesions within several weeks.5

Our patient’s outcome

Our patient’s sudden-onset rash alerted us to the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, and heavy proteinuria, which he was not aware of previously. We counselled him about stringent low-sugar, low-lipid diet control and exercise, and we started him on metformin and gemfibrozil. He was referred to an internal medicine specialist for further assessment and management of his severe hypertriglyceridemia and heavy proteinuria.

The rash started to wane 1 month after the patient started the metformin and gemfibrozil, and his drug regimen was changed to combination therapy with metformin/glimepiride and fenofibrate/simvastatin 6 weeks later when he was seen in the medical specialty clinic. Fundus photography performed 1 month after starting oral antidiabetic therapy showed no diabetic retinopathy or lipemia retinalis.

After 3 months of treatment, his serum triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c levels dropped to 3.8 mmol/L and 8.7%, respectively. The rash also resolved considerably, with only residual papules on the abdomen. This rapid clinical response to treatment of the underlying hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes further supported the clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

THE TAKEAWAY

Eruptive xanthoma is relatively rare, but it is important for family physicians to recognize this clinical presentation as a potential indicator of severe hypertriglyceridemia. Recognizing hypertriglyceridemia early is important, as it can be associated with an increased risk for acute pancreatitis. Moreover, eruptive xanthoma might be the sole presenting symptom of underlying diabetes mellitus or familial hyperlipidemia, both of which can lead to a significant increase in cardiovascular risk if uncontrolled.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chan Kam Sum, MBChB, FRACGP, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Out-patient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon, Hong Kong; cks048@ha.org.hk

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.

His medical history was unremarkable except for morbid obesity. He did not drink alcohol regularly and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the rash. He had no family history of hyperlipidemia, but his mother had a history of diabetes mellitus.

Physical examination showed numerous discrete erythematous papules with a creamy center on his trunk and his arms and legs. The lesions were more numerous on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. Some of the papules coalesced to form small plaques (FIGURE). There was no scaling, and the lesions were firm in texture. The patient’s face was spared, and there was no mucosal involvement. The patient was otherwise systemically well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the morphology, distribution, and abrupt onset of the diffuse nonpruritic papules in this morbidly obese (but otherwise systemically well) middle-aged man, a clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma was suspected. Subsequent blood testing revealed an elevated serum triglyceride level of 47.8 mmol/L (reference range, <1.7 mmol/L), elevated serum total cholesterol of 7.1 mmol/L (reference range, <6.2 mmol/L), and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 0.7 mmol/L (reference range, >1 mmol/L in men). He also had an elevated fasting serum glucose level of 12.9 mmol/L (reference range, 3.9–5.6 mmol/L) and an elevated hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 10.9%.

Subsequent thyroid, liver, and renal function tests were normal, but the patient had heavy proteinuria, with an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 355.6 mg/mmol (reference range, ≤2.5 mg/mmol). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, who confirmed the clinical diagnosis without the need for a skin biopsy.

DISCUSSION

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by an abrupt onset of crops of multiple yellowish to brownish papules that can coalesce into small plaques. The lesions can be generalized, but tend to be more densely distributed on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, buttocks, and thighs.5 Eruptive xanthoma often is associated with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be primary—as a result of a genetic defect caused by familial hypertriglyceridemia—or secondary, associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, and drugs like estrogen replacement therapies, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin.6 Pruritus and tenderness may or may not be present, and the Köbner phenomenon may occur.7

Continue to: The differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for eruptive xanthoma includes xanthoma disseminatum, non–Langerhans cell histiocytoses (eg, generalized eruptive histiocytosis), and cutaneous mastocytosis.1

Xanthoma disseminatum is an extremely rare, but benign, disorder of non–Langerhans cell origin. The average age of onset is older than 40 years. The rash consists of multiple red-yellow papules and nodules that most commonly present in flexural areas. Forty percent to 60% of patients have mucosal involvement, and rarely the central nervous system is involved.8

Generalized eruptive histiocytosis is another rare non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis that occurs mainly in adults and is characterized by widespread, symmetric, red-brown papules on the trunk, arms, and legs, and rarely the mucous membranes.9

Cutaneous mastocytosis, especially xanthelasmoid mastocytosis, consists of multiple pruritic, yellowish, papular or nodular lesions that may mimic eruptive xanthoma. It occurs mainly in children and rarely in adults.10

Confirming the diagnosis, initiating treatment

The diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma can be confirmed by skin biopsy if other differential diagnoses cannot be ruled out or the lesions do not resolve with treatment. Skin biopsy will reveal lipid-laden macrophages (known as foam cells) deposited in the dermis.7

Continue to: Treatment of eruptive xanthoma

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma involves management of the underlying causes of the condition. In most cases, dietary control, intensive triglyceride-lowering therapies, and treatment of other secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia result in complete resolution of the lesions within several weeks.5

Our patient’s outcome

Our patient’s sudden-onset rash alerted us to the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, and heavy proteinuria, which he was not aware of previously. We counselled him about stringent low-sugar, low-lipid diet control and exercise, and we started him on metformin and gemfibrozil. He was referred to an internal medicine specialist for further assessment and management of his severe hypertriglyceridemia and heavy proteinuria.

The rash started to wane 1 month after the patient started the metformin and gemfibrozil, and his drug regimen was changed to combination therapy with metformin/glimepiride and fenofibrate/simvastatin 6 weeks later when he was seen in the medical specialty clinic. Fundus photography performed 1 month after starting oral antidiabetic therapy showed no diabetic retinopathy or lipemia retinalis.

After 3 months of treatment, his serum triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c levels dropped to 3.8 mmol/L and 8.7%, respectively. The rash also resolved considerably, with only residual papules on the abdomen. This rapid clinical response to treatment of the underlying hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes further supported the clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma.

THE TAKEAWAY

Eruptive xanthoma is relatively rare, but it is important for family physicians to recognize this clinical presentation as a potential indicator of severe hypertriglyceridemia. Recognizing hypertriglyceridemia early is important, as it can be associated with an increased risk for acute pancreatitis. Moreover, eruptive xanthoma might be the sole presenting symptom of underlying diabetes mellitus or familial hyperlipidemia, both of which can lead to a significant increase in cardiovascular risk if uncontrolled.

CORRESPONDENCE

Chan Kam Sum, MBChB, FRACGP, Tseung Kwan O Jockey Club General Out-patient Clinic, 99 Po Lam Road North, G/F, Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon, Hong Kong; cks048@ha.org.hk

1. Tang WK. Eruptive xanthoma. [case reports]. Hong Kong Dermatol Venereol Bull. 2001;9:172-175.

2. Frew J, Murrell D, Haber R. Fifty shades of yellow: a review of the xanthodermatoses. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1109-1123.

3. Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

4. Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:157.

5. Holsinger JM, Campbell SM, Witman P. Multiple erythematous-yellow, dome-shaped papules. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:517.

6. Loeckermann S, Braun-Falco M. Eruptive xanthomas in association with metabolic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:565-566.

7. Merola JF, Mengden SJ, Soldano A, et al. Eruptive xanthomas. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

8. Park M, Boone B, Devas S. Xanthoma disseminatum: case report and mini-review of the literature. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:150-154.

9. Attia A, Seleit I, El Badawy N, et al. Photoletter to the editor: generalized eruptive histiocytoma. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:53-55.

10. Nabavi NS, Nejad MH, Feli S, et al. Adult onset of xanthelasmoid mastocytosis: report of a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:468.

1. Tang WK. Eruptive xanthoma. [case reports]. Hong Kong Dermatol Venereol Bull. 2001;9:172-175.

2. Frew J, Murrell D, Haber R. Fifty shades of yellow: a review of the xanthodermatoses. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1109-1123.

3. Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, et al. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014;158:181-188.

4. Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, et al. Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: a retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:157.

5. Holsinger JM, Campbell SM, Witman P. Multiple erythematous-yellow, dome-shaped papules. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:517.

6. Loeckermann S, Braun-Falco M. Eruptive xanthomas in association with metabolic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:565-566.

7. Merola JF, Mengden SJ, Soldano A, et al. Eruptive xanthomas. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

8. Park M, Boone B, Devas S. Xanthoma disseminatum: case report and mini-review of the literature. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2014;22:150-154.

9. Attia A, Seleit I, El Badawy N, et al. Photoletter to the editor: generalized eruptive histiocytoma. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:53-55.

10. Nabavi NS, Nejad MH, Feli S, et al. Adult onset of xanthelasmoid mastocytosis: report of a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:468.

Bariatric surgery + medical therapy: Effective Tx for T2DM?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 46-year-old woman presents with a body mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and a glycated hemoglobin (HgbA1c) of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 units/d, with minimal change in HgbA1c. Should you recommend bariatric surgery as an option for the treatment of diabetes?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes and at least 95% of those have type 2.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal in order to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Treatment strategies may include lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing secretion of insulin, insulin replacement, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) currently recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as first-line therapy for the management of diabetes,2 but these by themselves are often inadequate. In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for other populations with T2DM (see the PURL, “How do these 3 diabetes agents compare in reducing mortality?”), the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for the treatment of patients with T2DM, a BMI ≥35 kg/m2, and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4 However, this recommendation from the ADA supporting bariatric surgery is based only on short-term studies.

For example, one single-center nonblinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 60 patients with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 found reductions in HgbA1C levels from the average baseline of 8.65±1.45% to 7.7±0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4±1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35 kg/m2), gastric bypass had better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy, with 93% of patients in the gastric bypass group achieving remission of T2DM vs 47% of patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group (P=.02) over a 12-month period.6

The current study sought to examine the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up shows surgery + intensive medical therapy works

This study by Schauer et al was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were 20 to 60 years of age, had a BMI of 27 to 43 kg/m2, and had an HgbA1C >7%. Patients with previous bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Each patient was randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. All patients underwent IMT as defined by the ADA. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an HgbA1c ≤6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period leaving 149; 134 completed the 5-year follow-up; 8 patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment; an additional 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

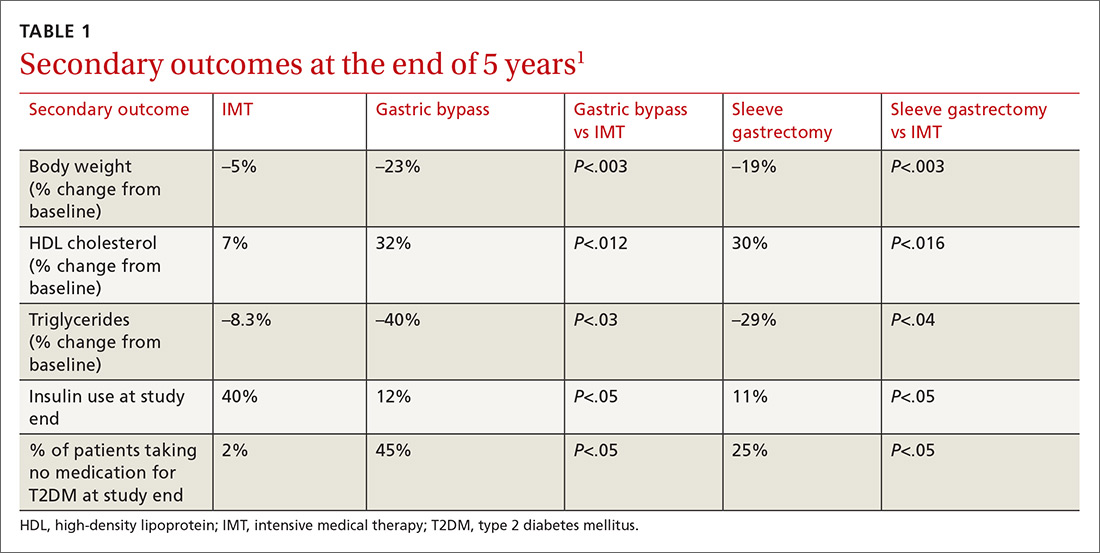

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an HgbA1c of ≤6% compared with the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.01; 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.03). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels, and greater increases from baseline in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels; they also required less diabetic medication for glycemic control (see TABLE 11). However, when data were imputed for the intention-to-treat analysis, P-values were P=0.08 for gastric bypass and P=0.17 for sleeve gastrectomy compared with the IMT group for lowering HgbA1c.

WHAT’S NEW?

Adding surgery has big benefits with minimal adverse effects

Prior studies that evaluated the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM for patients with a BMI ≥27 kg/m2, which is below the starting BMI (35 kg/m2) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis, in this patient population is significant.1 Complications can include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling regarding the possible complications is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1c, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size of the study...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who received gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up compared with the patients who received sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to that with IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and the cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Asssociation. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42 (suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011;146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 46-year-old woman presents with a body mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and a glycated hemoglobin (HgbA1c) of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 units/d, with minimal change in HgbA1c. Should you recommend bariatric surgery as an option for the treatment of diabetes?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes and at least 95% of those have type 2.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal in order to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Treatment strategies may include lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing secretion of insulin, insulin replacement, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) currently recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as first-line therapy for the management of diabetes,2 but these by themselves are often inadequate. In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for other populations with T2DM (see the PURL, “How do these 3 diabetes agents compare in reducing mortality?”), the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for the treatment of patients with T2DM, a BMI ≥35 kg/m2, and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4 However, this recommendation from the ADA supporting bariatric surgery is based only on short-term studies.

For example, one single-center nonblinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 60 patients with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 found reductions in HgbA1C levels from the average baseline of 8.65±1.45% to 7.7±0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4±1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35 kg/m2), gastric bypass had better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy, with 93% of patients in the gastric bypass group achieving remission of T2DM vs 47% of patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group (P=.02) over a 12-month period.6

The current study sought to examine the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up shows surgery + intensive medical therapy works

This study by Schauer et al was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were 20 to 60 years of age, had a BMI of 27 to 43 kg/m2, and had an HgbA1C >7%. Patients with previous bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Each patient was randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. All patients underwent IMT as defined by the ADA. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an HgbA1c ≤6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period leaving 149; 134 completed the 5-year follow-up; 8 patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment; an additional 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an HgbA1c of ≤6% compared with the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.01; 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.03). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels, and greater increases from baseline in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels; they also required less diabetic medication for glycemic control (see TABLE 11). However, when data were imputed for the intention-to-treat analysis, P-values were P=0.08 for gastric bypass and P=0.17 for sleeve gastrectomy compared with the IMT group for lowering HgbA1c.

WHAT’S NEW?

Adding surgery has big benefits with minimal adverse effects

Prior studies that evaluated the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM for patients with a BMI ≥27 kg/m2, which is below the starting BMI (35 kg/m2) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis, in this patient population is significant.1 Complications can include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling regarding the possible complications is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1c, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size of the study...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who received gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up compared with the patients who received sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to that with IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and the cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 46-year-old woman presents with a body mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2, a 4-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and a glycated hemoglobin (HgbA1c) of 9.8%. The patient is currently being treated with intensive medical therapy (IMT), including metformin 2000 mg/d, sitagliptin 100 mg/d, and insulin glargine 12 units/d, with minimal change in HgbA1c. Should you recommend bariatric surgery as an option for the treatment of diabetes?

One in 11 Americans has diabetes and at least 95% of those have type 2.2,3 The treatment of T2DM is generally multimodal in order to target the various mechanisms that cause hyperglycemia. Treatment strategies may include lifestyle modifications, decreasing insulin resistance, increasing secretion of insulin, insulin replacement, and targeting incretin-hormonal pathways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) currently recommends diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications as first-line therapy for the management of diabetes,2 but these by themselves are often inadequate. In addition to various pharmacotherapeutic strategies for other populations with T2DM (see the PURL, “How do these 3 diabetes agents compare in reducing mortality?”), the ADA recommends bariatric surgery for the treatment of patients with T2DM, a BMI ≥35 kg/m2, and uncontrolled hyperglycemia.2,4 However, this recommendation from the ADA supporting bariatric surgery is based only on short-term studies.

For example, one single-center nonblinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 60 patients with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 found reductions in HgbA1C levels from the average baseline of 8.65±1.45% to 7.7±0.6% in the IMT group and to 6.4±1.4% in the gastric-bypass group at 2 years.5 In another study, a randomized double-blind trial involving 60 moderately obese patients (BMI, 25-35 kg/m2), gastric bypass had better outcomes than sleeve gastrectomy, with 93% of patients in the gastric bypass group achieving remission of T2DM vs 47% of patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group (P=.02) over a 12-month period.6

The current study sought to examine the long-term outcomes of IMT alone vs bariatric surgery with IMT for the treatment of T2DM in patients who are overweight or obese.1

STUDY SUMMARY

5-year follow-up shows surgery + intensive medical therapy works

This study by Schauer et al was a 5-year follow-up of a nonblinded, single-center RCT comparing IMT alone to IMT with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy in 150 patients with T2DM.1 Patients were included if they were 20 to 60 years of age, had a BMI of 27 to 43 kg/m2, and had an HgbA1C >7%. Patients with previous bariatric surgery, complex abdominal surgery, or uncontrolled medical or psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Each patient was randomly placed in a 1:1:1 fashion into 3 groups: IMT only, IMT and gastric bypass, or IMT and sleeve gastrectomy. All patients underwent IMT as defined by the ADA. The primary outcome was the number of patients with an HgbA1c ≤6%. Secondary outcomes included weight loss, glucose control, lipid levels, blood pressure, medication use, renal function, adverse effects, ophthalmologic outcomes, and quality of life.

Continue to: Of the 150 patients...

Of the 150 patients, 1 died during the follow-up period leaving 149; 134 completed the 5-year follow-up; 8 patients in the IMT group and 1 patient in the sleeve gastrectomy group never initiated assigned treatment; an additional 6 patients were lost to follow-up. One patient from the IMT group and 1 patient from the sleeve gastrectomy group crossed over to the gastric bypass group.

Results. More patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups achieved an HgbA1c of ≤6% compared with the IMT group (14 of 49 gastric bypass patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.01; 11 of 47 sleeve gastrectomy patients vs 2 of 38 IMT patients; P=.03). Compared with those in the IMT group, the patients in the bariatric surgery and sleeve gastrectomy groups showed greater reductions from baseline in body weight and triglyceride levels, and greater increases from baseline in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels; they also required less diabetic medication for glycemic control (see TABLE 11). However, when data were imputed for the intention-to-treat analysis, P-values were P=0.08 for gastric bypass and P=0.17 for sleeve gastrectomy compared with the IMT group for lowering HgbA1c.

WHAT’S NEW?

Adding surgery has big benefits with minimal adverse effects

Prior studies that evaluated the effect of gastric bypass surgery on diabetes were observational or had a shorter follow-up duration. This study demonstrates bariatric surgery plus IMT has long-term benefits with minimal adverse events compared with IMT alone.1,5 Additionally, this study supports recommendations for bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM for patients with a BMI ≥27 kg/m2, which is below the starting BMI (35 kg/m2) recommended by the ADA.1,4

CAVEATS

Surgery is not without risks

The risk for surgical complications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, severe hypoglycemia requiring intervention, and ketoacidosis, in this patient population is significant.1 Complications can include gastrointestinal leak, stroke, and infection.1 Additionally, long-term complications from bariatric surgery are emerging and include choledocholithiasis, intestinal obstruction, and esophageal pathology.7 Extensive patient counseling regarding the possible complications is necessary to ensure that patients make an informed decision regarding surgery.

This study utilized surrogate markers (A1c, lipid levels, and body weight) as disease-oriented outcome measures. Patient-oriented outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality, were not explored in this study.

Continue to: Due to the small sample size of the study...

Due to the small sample size of the study, it is unclear if the outcomes of the 2 surgery groups were significantly different. Patients who received gastric bypass surgery had more weight loss and used less diabetes medication at the end of follow-up compared with the patients who received sleeve gastrectomy. More information is needed to determine which gastric surgery is preferable for the treatment of T2DM while minimizing adverse effects. However, both of the procedures had outcomes superior to that with IMT, and selection of a particular type of surgery should be a joint decision between the patient and provider.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Access and cost may be barriers

The major barriers to implementation are access to, and the cost of, bariatric surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Asssociation. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42 (suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011;146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

1. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

2. American Diabetes Asssociation. Obesity management for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42 (suppl 1):S81-S89.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, et al. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a joint statement by international diabetes organizations. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:861-877.

5. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1577-1585.

6. Lee WJ, Chong K, Ser KH, et al. Gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Surg. 2011;146:143-148.

7. Schulman AR, Thompson CC. Complications of bariatric surgery: what you can expect to see in your GI practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1640-1655.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider bariatric surgery with medical therapy as a treatment option for adults with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and a body mass index ≥27 kg/m2.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a nonblinded, single-center, randomized controlled trial.

Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

Are You Sitting Down for This?

Not all sedentary behavior is equal, say researchers from Universidad Autónoma de Madrid in Spain, who evaluated the sedentary habits of 5,459 women and 4,740 men.

The researchers note that several studies have found that, unlike, for example, computer use and reading, TV watching is consistently associated with adverse health outcomes, such as metabolic syndrome, obesity, and diabetes mellitus (DM). But different sedentary behaviors (SBs) have different health effects, they add. They cite research that suggests TV and other “passive” SBs (eg, listening or talking while sitting) could be more harmful than “mentally active” SBs, such as computer use and reading. In this study, “passive” sedentary time, such as TV watching, was associated with less recreational activity and higher body weight. Time at the computer and reading were linked to more recreational physical activity but less light-intensity activity at home.

Moreover, each type of SB has a distinct demographic and lifestyle profile, the researchers say. Older age, lower education, unhealthy lifestyle (smoking, worse diet, less physical activity, higher BMI) and chronic morbidity, such as DM or osteomuscular disease, were linked to more TV time. Longer time at the computer or in commuting was linked to younger age, male gender, higher education, and a sedentary job.

Watching TV had no association with total time spent on the rest of leisure-time SBs. The researchers also found that “mentally active” SBs, such as using the computer and reading, tend to cluster.