User login

Low Back Pain Triggered by Fatigue, Distractions, and Awkward Positions

New research reveals the physical and psychosocial factors that significantly increase the risk of low back pain onset. The trial results, which were published online ahead of print February 9 in Arthritis Care & Research, show that being engaged in manual tasks involving awkward positions will increase the risk of low back pain by 8 times. People who are distracted during activities or fatigued also significantly increase their risk of acute low back pain.

“Understanding which risk factors contribute to back pain and controlling exposure to these risks is an important first step in prevention,” said Manuela Ferreira, PhD, Associate Professor at the George Institute for Global Health and Sydney Medical School at the University of Sydney in New South Wales, Australia. “Our study is the first to examine brief exposure to a range of modifiable triggers for an acute episode of low back pain.”

For this case-crossover study, Dr. Ferreira and colleagues recruited 999 participants from 300 primary care clinics in Sydney, Australia, who had an acute low back pain episode between October 2011 and November 2012. Participants were asked to report exposure to 12 physical or psychosocial factors in the 96 hours prior to the onset of back pain.

The study found that:

• The risk of a new episode of low back pain significantly increased due to a range of triggers, from an odds ratio of 2.7 for moderate to vigorous physical activity to 25.0 for distraction during an activity.

• Back pain risk was highest between 7:00 am and at noontime.

• Age moderated the effect of exposure to heavy loads, with an odds ratio for individuals age 20, 40, or 60 at 13.6, 6.0, and 2.7, respectively.

“Understanding which modifiable risk factors lead to low back pain is an important step toward controlling a condition that affects so many worldwide,” said Dr. Ferreira. “Our findings enhance knowledge of low back pain triggers and will assist the development of new prevention programs that can reduce suffering from this potentially disabling condition.”

Suggested Reading

Steffens D, Ferreira ML, Latimer J, et al. What triggers an episode of acute low back pain? a case-crossover study. Arthritis Care Res. 2015 Feb 9. [Epub ahead of print]

New research reveals the physical and psychosocial factors that significantly increase the risk of low back pain onset. The trial results, which were published online ahead of print February 9 in Arthritis Care & Research, show that being engaged in manual tasks involving awkward positions will increase the risk of low back pain by 8 times. People who are distracted during activities or fatigued also significantly increase their risk of acute low back pain.

“Understanding which risk factors contribute to back pain and controlling exposure to these risks is an important first step in prevention,” said Manuela Ferreira, PhD, Associate Professor at the George Institute for Global Health and Sydney Medical School at the University of Sydney in New South Wales, Australia. “Our study is the first to examine brief exposure to a range of modifiable triggers for an acute episode of low back pain.”

For this case-crossover study, Dr. Ferreira and colleagues recruited 999 participants from 300 primary care clinics in Sydney, Australia, who had an acute low back pain episode between October 2011 and November 2012. Participants were asked to report exposure to 12 physical or psychosocial factors in the 96 hours prior to the onset of back pain.

The study found that:

• The risk of a new episode of low back pain significantly increased due to a range of triggers, from an odds ratio of 2.7 for moderate to vigorous physical activity to 25.0 for distraction during an activity.

• Back pain risk was highest between 7:00 am and at noontime.

• Age moderated the effect of exposure to heavy loads, with an odds ratio for individuals age 20, 40, or 60 at 13.6, 6.0, and 2.7, respectively.

“Understanding which modifiable risk factors lead to low back pain is an important step toward controlling a condition that affects so many worldwide,” said Dr. Ferreira. “Our findings enhance knowledge of low back pain triggers and will assist the development of new prevention programs that can reduce suffering from this potentially disabling condition.”

New research reveals the physical and psychosocial factors that significantly increase the risk of low back pain onset. The trial results, which were published online ahead of print February 9 in Arthritis Care & Research, show that being engaged in manual tasks involving awkward positions will increase the risk of low back pain by 8 times. People who are distracted during activities or fatigued also significantly increase their risk of acute low back pain.

“Understanding which risk factors contribute to back pain and controlling exposure to these risks is an important first step in prevention,” said Manuela Ferreira, PhD, Associate Professor at the George Institute for Global Health and Sydney Medical School at the University of Sydney in New South Wales, Australia. “Our study is the first to examine brief exposure to a range of modifiable triggers for an acute episode of low back pain.”

For this case-crossover study, Dr. Ferreira and colleagues recruited 999 participants from 300 primary care clinics in Sydney, Australia, who had an acute low back pain episode between October 2011 and November 2012. Participants were asked to report exposure to 12 physical or psychosocial factors in the 96 hours prior to the onset of back pain.

The study found that:

• The risk of a new episode of low back pain significantly increased due to a range of triggers, from an odds ratio of 2.7 for moderate to vigorous physical activity to 25.0 for distraction during an activity.

• Back pain risk was highest between 7:00 am and at noontime.

• Age moderated the effect of exposure to heavy loads, with an odds ratio for individuals age 20, 40, or 60 at 13.6, 6.0, and 2.7, respectively.

“Understanding which modifiable risk factors lead to low back pain is an important step toward controlling a condition that affects so many worldwide,” said Dr. Ferreira. “Our findings enhance knowledge of low back pain triggers and will assist the development of new prevention programs that can reduce suffering from this potentially disabling condition.”

Suggested Reading

Steffens D, Ferreira ML, Latimer J, et al. What triggers an episode of acute low back pain? a case-crossover study. Arthritis Care Res. 2015 Feb 9. [Epub ahead of print]

Suggested Reading

Steffens D, Ferreira ML, Latimer J, et al. What triggers an episode of acute low back pain? a case-crossover study. Arthritis Care Res. 2015 Feb 9. [Epub ahead of print]

Study: Osteoarthritis develops sooner than thought after ACL injury, repair

People who have had a knee reconstruction following trauma may be susceptible to osteoarthritis sooner than currently thought, according to new MRI findings at 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Almost a third of people studied had some evidence of early osteoarthritis (OA) at that early time point, challenging “existing dogma that degenerative joint disease does not become apparent for years post-ACLR,” reported Dr. Kay Crossley of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Feb. 18 [doi:10.1002/art.39005]).

However, as they did not have access to preoperative images, they could not rule out that some OA features may have been preexisting and not related to knee trauma, they said.

“This is a sample that was taken after the injury and after the reconstruction, so they truly don’t know that what they’re finding is as a result of even the injury, surgery, or the meniscal damage or meniscal resection they had done at the time,” Dr. David J. Hunter, a leading OA expert from Sydney (Australia) University, said when asked to comment on the study’s findings.

“It may well be that these were people that had some underlying structural damage,” he added.

The researchers noted that radiographic knee OA was thought to be as high as 50%-90% a decade after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). The issue is particularly important because ACL injuries typically occur in younger adults who are then prone to developing knee OA before they reach 40 years, they said.

“Early detection of knee OA after ACLR may permit early intervention such as load management, which is likely to be more effective prior to the development of advanced disease,” they wrote.

Their study included 111 patients aged 18-50 years who had undergone single-bundle hamstring-tendon autograft ACLR 1 year earlier.

MRI scans of their knees were compared with 20 uninjured asymptomatic matched controls. The researchers used the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS) to score specific OA features because the more recent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Osteoarthritis Score (ACLOAS) had not been published at the time of their study.

Results showed that 34 (31%) patients had MRI-defined knee OA following an ACLR a year earlier.

MRI-OA features were most frequently found in the patellofemoral compartment, particularly the medial femoral trochlea, a potentially underrecognized site of knee pathology following reconstruction, the researchers said.

Pathology in the patellofemoral joint included not only “early” features of OA, such as bone marrow lesions and partial-thickness cartilage loss, but also frank osteophytes on MRI, they noted.

None of the uninjured control knees had MRI-defined patellofemoral or tibiofemoral OA.

The authors acknowledged that a lack of access to preoperative knee images limited the conclusions they could reach in their study, but they noted that MRI-OA features were rarely seen in the small sample of uninjured matched control knees.

“Combined with the observation that six times as many reconstructed knees had radiographic osteophytes than uninjured contralateral knees, these findings suggest that knee trauma and/or reconstruction was strongly implicated in the development of OA features,” they wrote.

Another limitation that the authors acknowledged was that the MRI definition of OA was relatively new and was likely to be refined as the understanding of OA pathology evolved.

Dr. Hunter, who was the lead investigator involved in developing the MOAKS, agreed that the definition needed more validity and testing.

“This is the third study that uses that definition, and I do think that long-term clinical implications of what MRI definition means is unknown,” he said. “The challenge that we have is that we do kick up a lot of abnormalities, and we don’t truly know what the long-term clinical implications of those abnormalities are at this point.”

“There are a lot of problems with the way this study has been done, but I do think it is really helpful that it highlights how important injury is with regards to predisposing to early OA.”

“It’s something that a lot of people don’t really highlight or pay attention to,” he said.

The study was partly funded by the Queensland Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Network, a University of Melbourne Research Collaboration grant, and University of British Columbia’s Centre for Hip Health and Mobility via the Society for Mobility and Health. One study author is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme and TissueGene. No other authors declared conflicts of interest.

People who have had a knee reconstruction following trauma may be susceptible to osteoarthritis sooner than currently thought, according to new MRI findings at 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Almost a third of people studied had some evidence of early osteoarthritis (OA) at that early time point, challenging “existing dogma that degenerative joint disease does not become apparent for years post-ACLR,” reported Dr. Kay Crossley of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Feb. 18 [doi:10.1002/art.39005]).

However, as they did not have access to preoperative images, they could not rule out that some OA features may have been preexisting and not related to knee trauma, they said.

“This is a sample that was taken after the injury and after the reconstruction, so they truly don’t know that what they’re finding is as a result of even the injury, surgery, or the meniscal damage or meniscal resection they had done at the time,” Dr. David J. Hunter, a leading OA expert from Sydney (Australia) University, said when asked to comment on the study’s findings.

“It may well be that these were people that had some underlying structural damage,” he added.

The researchers noted that radiographic knee OA was thought to be as high as 50%-90% a decade after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). The issue is particularly important because ACL injuries typically occur in younger adults who are then prone to developing knee OA before they reach 40 years, they said.

“Early detection of knee OA after ACLR may permit early intervention such as load management, which is likely to be more effective prior to the development of advanced disease,” they wrote.

Their study included 111 patients aged 18-50 years who had undergone single-bundle hamstring-tendon autograft ACLR 1 year earlier.

MRI scans of their knees were compared with 20 uninjured asymptomatic matched controls. The researchers used the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS) to score specific OA features because the more recent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Osteoarthritis Score (ACLOAS) had not been published at the time of their study.

Results showed that 34 (31%) patients had MRI-defined knee OA following an ACLR a year earlier.

MRI-OA features were most frequently found in the patellofemoral compartment, particularly the medial femoral trochlea, a potentially underrecognized site of knee pathology following reconstruction, the researchers said.

Pathology in the patellofemoral joint included not only “early” features of OA, such as bone marrow lesions and partial-thickness cartilage loss, but also frank osteophytes on MRI, they noted.

None of the uninjured control knees had MRI-defined patellofemoral or tibiofemoral OA.

The authors acknowledged that a lack of access to preoperative knee images limited the conclusions they could reach in their study, but they noted that MRI-OA features were rarely seen in the small sample of uninjured matched control knees.

“Combined with the observation that six times as many reconstructed knees had radiographic osteophytes than uninjured contralateral knees, these findings suggest that knee trauma and/or reconstruction was strongly implicated in the development of OA features,” they wrote.

Another limitation that the authors acknowledged was that the MRI definition of OA was relatively new and was likely to be refined as the understanding of OA pathology evolved.

Dr. Hunter, who was the lead investigator involved in developing the MOAKS, agreed that the definition needed more validity and testing.

“This is the third study that uses that definition, and I do think that long-term clinical implications of what MRI definition means is unknown,” he said. “The challenge that we have is that we do kick up a lot of abnormalities, and we don’t truly know what the long-term clinical implications of those abnormalities are at this point.”

“There are a lot of problems with the way this study has been done, but I do think it is really helpful that it highlights how important injury is with regards to predisposing to early OA.”

“It’s something that a lot of people don’t really highlight or pay attention to,” he said.

The study was partly funded by the Queensland Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Network, a University of Melbourne Research Collaboration grant, and University of British Columbia’s Centre for Hip Health and Mobility via the Society for Mobility and Health. One study author is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme and TissueGene. No other authors declared conflicts of interest.

People who have had a knee reconstruction following trauma may be susceptible to osteoarthritis sooner than currently thought, according to new MRI findings at 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Almost a third of people studied had some evidence of early osteoarthritis (OA) at that early time point, challenging “existing dogma that degenerative joint disease does not become apparent for years post-ACLR,” reported Dr. Kay Crossley of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Feb. 18 [doi:10.1002/art.39005]).

However, as they did not have access to preoperative images, they could not rule out that some OA features may have been preexisting and not related to knee trauma, they said.

“This is a sample that was taken after the injury and after the reconstruction, so they truly don’t know that what they’re finding is as a result of even the injury, surgery, or the meniscal damage or meniscal resection they had done at the time,” Dr. David J. Hunter, a leading OA expert from Sydney (Australia) University, said when asked to comment on the study’s findings.

“It may well be that these were people that had some underlying structural damage,” he added.

The researchers noted that radiographic knee OA was thought to be as high as 50%-90% a decade after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). The issue is particularly important because ACL injuries typically occur in younger adults who are then prone to developing knee OA before they reach 40 years, they said.

“Early detection of knee OA after ACLR may permit early intervention such as load management, which is likely to be more effective prior to the development of advanced disease,” they wrote.

Their study included 111 patients aged 18-50 years who had undergone single-bundle hamstring-tendon autograft ACLR 1 year earlier.

MRI scans of their knees were compared with 20 uninjured asymptomatic matched controls. The researchers used the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS) to score specific OA features because the more recent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Osteoarthritis Score (ACLOAS) had not been published at the time of their study.

Results showed that 34 (31%) patients had MRI-defined knee OA following an ACLR a year earlier.

MRI-OA features were most frequently found in the patellofemoral compartment, particularly the medial femoral trochlea, a potentially underrecognized site of knee pathology following reconstruction, the researchers said.

Pathology in the patellofemoral joint included not only “early” features of OA, such as bone marrow lesions and partial-thickness cartilage loss, but also frank osteophytes on MRI, they noted.

None of the uninjured control knees had MRI-defined patellofemoral or tibiofemoral OA.

The authors acknowledged that a lack of access to preoperative knee images limited the conclusions they could reach in their study, but they noted that MRI-OA features were rarely seen in the small sample of uninjured matched control knees.

“Combined with the observation that six times as many reconstructed knees had radiographic osteophytes than uninjured contralateral knees, these findings suggest that knee trauma and/or reconstruction was strongly implicated in the development of OA features,” they wrote.

Another limitation that the authors acknowledged was that the MRI definition of OA was relatively new and was likely to be refined as the understanding of OA pathology evolved.

Dr. Hunter, who was the lead investigator involved in developing the MOAKS, agreed that the definition needed more validity and testing.

“This is the third study that uses that definition, and I do think that long-term clinical implications of what MRI definition means is unknown,” he said. “The challenge that we have is that we do kick up a lot of abnormalities, and we don’t truly know what the long-term clinical implications of those abnormalities are at this point.”

“There are a lot of problems with the way this study has been done, but I do think it is really helpful that it highlights how important injury is with regards to predisposing to early OA.”

“It’s something that a lot of people don’t really highlight or pay attention to,” he said.

The study was partly funded by the Queensland Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Network, a University of Melbourne Research Collaboration grant, and University of British Columbia’s Centre for Hip Health and Mobility via the Society for Mobility and Health. One study author is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme and TissueGene. No other authors declared conflicts of interest.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: People who have undergone anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction following trauma may be susceptible to early OA sooner than previously thought, but the study authors did not have access to baseline images to rule out existing pathology.

Major finding: A third of the 111 patients studied had evidence of MRI-defined OA a year after their surgery.

Data source: MRI study of 111 patients who had undergone ACL surgery matched with 20 uninjured asymptomatic controls.

Disclosures: The study was partly funded by the Queensland Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Network, a University of Melbourne Research Collaboration grant, and University of British Columbia’s Centre for Hip Health and Mobility via the Society for Mobility and Health. One study author is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme and TissueGene. No other authors declared conflicts of interest.

VIDEO: Ask patients about metal-on-metal hip implants

MAUI, HAWAII – Rheumatologists and other providers need to ask patients if they’ve had metal-on-metal hip implants.

That goes for hip resurfacing – which by definition is metal on metal – as well as actual metal-on-metal hips. Signs of trouble can be as subtle as mental status changes, and they go well beyond the traditional issues with worn-out artificial joints.

During a video interview at the 2015 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium, Dr. Bill Bugbee, an orthopedic surgeon and professor at the University of California, San Diego, explained the problems and the warning signs for which physicians should watch.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MAUI, HAWAII – Rheumatologists and other providers need to ask patients if they’ve had metal-on-metal hip implants.

That goes for hip resurfacing – which by definition is metal on metal – as well as actual metal-on-metal hips. Signs of trouble can be as subtle as mental status changes, and they go well beyond the traditional issues with worn-out artificial joints.

During a video interview at the 2015 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium, Dr. Bill Bugbee, an orthopedic surgeon and professor at the University of California, San Diego, explained the problems and the warning signs for which physicians should watch.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MAUI, HAWAII – Rheumatologists and other providers need to ask patients if they’ve had metal-on-metal hip implants.

That goes for hip resurfacing – which by definition is metal on metal – as well as actual metal-on-metal hips. Signs of trouble can be as subtle as mental status changes, and they go well beyond the traditional issues with worn-out artificial joints.

During a video interview at the 2015 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium, Dr. Bill Bugbee, an orthopedic surgeon and professor at the University of California, San Diego, explained the problems and the warning signs for which physicians should watch.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT RWCS 2015

ACL repair: ‘We have to do better’

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A novel approach to repairing anterior cruciate ligament injuries – and perhaps thereby avoiding a downstream tidal wave of knee osteoarthritis – is creating major buzz in sports medicine circles.

“You’ll probably hear much more about this bioenhanced repair, with the expectation of achieving strength equal to that of ACL reconstruction and perhaps preventing the development of osteoarthritis 15 years down the road,” Dr. M. Timothy Hresko predicted at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

He cited research led by his colleague Dr. Martha M. Murray of Boston Children’s Hospital, which has resulted in development of a surgical technique combining a tissue-engineered composite scaffold with a suture repair of the torn ACL in what Dr. Murray has termed a bioenhanced repair.

Her work, to date preclinical, has garnered major awards from both the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Food and Drug Administration recently granted approval for the first clinical safety studies, to begin this year.

There is a major unmet need for better methods of repairing ACL injuries. They’re common, with an estimated 550,000 cases per year. The peak incidence occurs in 15- to 19-year-old female athletes. And the current gold standard therapy consisting of ACL reconstruction using an allograft or hamstring graft has a disturbingly high failure rate, both early and late. The graft failure rate is up to 20% in the first 2 years, climbing to 50% at 10 years.

“We just have to do better,” conceded Dr. Hresko, an orthopedic surgeon at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Boston Children’s Hospital.

“One of the interesting and unfortunate facts,” he continued, “is that roughly 80% of people who have an ACL injury, with or without reconstruction, are still going to have osteoarthritis 14 years after the injury. So, if this is your 15-year-old daughter who plays basketball, she’ll only be 30 and will already have degenerative arthritis of the knee at what should still be a very active period of life.”

The bioenhanced repair now under study uses an extracellular matrix-based scaffold, which is loaded with a few milliliters of the patient’s own platelet-enriched plasma. The scaffold is applied between the torn ligament ends in order to stimulate collagen production and promote ligament healing. The suture repair of the ligament entails much less trauma than does standard reconstructive surgery.

In large-animal studies, the bioenhanced repair resulted in the same yield load, stiffness, and other desirable biomechanical properties at 1 year as with major reconstructive surgery. However, while premature posttraumatic osteoarthritis occurred in 80% of the knees treated with standard ACL reconstruction, there was no evidence of such damage 1 year following bioenhanced repair. Nor have adverse reactions to the scaffold been noted in the porcine model.

Dr. Hresko reported serving as a consultant to Depuy Spine.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A novel approach to repairing anterior cruciate ligament injuries – and perhaps thereby avoiding a downstream tidal wave of knee osteoarthritis – is creating major buzz in sports medicine circles.

“You’ll probably hear much more about this bioenhanced repair, with the expectation of achieving strength equal to that of ACL reconstruction and perhaps preventing the development of osteoarthritis 15 years down the road,” Dr. M. Timothy Hresko predicted at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

He cited research led by his colleague Dr. Martha M. Murray of Boston Children’s Hospital, which has resulted in development of a surgical technique combining a tissue-engineered composite scaffold with a suture repair of the torn ACL in what Dr. Murray has termed a bioenhanced repair.

Her work, to date preclinical, has garnered major awards from both the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Food and Drug Administration recently granted approval for the first clinical safety studies, to begin this year.

There is a major unmet need for better methods of repairing ACL injuries. They’re common, with an estimated 550,000 cases per year. The peak incidence occurs in 15- to 19-year-old female athletes. And the current gold standard therapy consisting of ACL reconstruction using an allograft or hamstring graft has a disturbingly high failure rate, both early and late. The graft failure rate is up to 20% in the first 2 years, climbing to 50% at 10 years.

“We just have to do better,” conceded Dr. Hresko, an orthopedic surgeon at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Boston Children’s Hospital.

“One of the interesting and unfortunate facts,” he continued, “is that roughly 80% of people who have an ACL injury, with or without reconstruction, are still going to have osteoarthritis 14 years after the injury. So, if this is your 15-year-old daughter who plays basketball, she’ll only be 30 and will already have degenerative arthritis of the knee at what should still be a very active period of life.”

The bioenhanced repair now under study uses an extracellular matrix-based scaffold, which is loaded with a few milliliters of the patient’s own platelet-enriched plasma. The scaffold is applied between the torn ligament ends in order to stimulate collagen production and promote ligament healing. The suture repair of the ligament entails much less trauma than does standard reconstructive surgery.

In large-animal studies, the bioenhanced repair resulted in the same yield load, stiffness, and other desirable biomechanical properties at 1 year as with major reconstructive surgery. However, while premature posttraumatic osteoarthritis occurred in 80% of the knees treated with standard ACL reconstruction, there was no evidence of such damage 1 year following bioenhanced repair. Nor have adverse reactions to the scaffold been noted in the porcine model.

Dr. Hresko reported serving as a consultant to Depuy Spine.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A novel approach to repairing anterior cruciate ligament injuries – and perhaps thereby avoiding a downstream tidal wave of knee osteoarthritis – is creating major buzz in sports medicine circles.

“You’ll probably hear much more about this bioenhanced repair, with the expectation of achieving strength equal to that of ACL reconstruction and perhaps preventing the development of osteoarthritis 15 years down the road,” Dr. M. Timothy Hresko predicted at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

He cited research led by his colleague Dr. Martha M. Murray of Boston Children’s Hospital, which has resulted in development of a surgical technique combining a tissue-engineered composite scaffold with a suture repair of the torn ACL in what Dr. Murray has termed a bioenhanced repair.

Her work, to date preclinical, has garnered major awards from both the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Food and Drug Administration recently granted approval for the first clinical safety studies, to begin this year.

There is a major unmet need for better methods of repairing ACL injuries. They’re common, with an estimated 550,000 cases per year. The peak incidence occurs in 15- to 19-year-old female athletes. And the current gold standard therapy consisting of ACL reconstruction using an allograft or hamstring graft has a disturbingly high failure rate, both early and late. The graft failure rate is up to 20% in the first 2 years, climbing to 50% at 10 years.

“We just have to do better,” conceded Dr. Hresko, an orthopedic surgeon at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Boston Children’s Hospital.

“One of the interesting and unfortunate facts,” he continued, “is that roughly 80% of people who have an ACL injury, with or without reconstruction, are still going to have osteoarthritis 14 years after the injury. So, if this is your 15-year-old daughter who plays basketball, she’ll only be 30 and will already have degenerative arthritis of the knee at what should still be a very active period of life.”

The bioenhanced repair now under study uses an extracellular matrix-based scaffold, which is loaded with a few milliliters of the patient’s own platelet-enriched plasma. The scaffold is applied between the torn ligament ends in order to stimulate collagen production and promote ligament healing. The suture repair of the ligament entails much less trauma than does standard reconstructive surgery.

In large-animal studies, the bioenhanced repair resulted in the same yield load, stiffness, and other desirable biomechanical properties at 1 year as with major reconstructive surgery. However, while premature posttraumatic osteoarthritis occurred in 80% of the knees treated with standard ACL reconstruction, there was no evidence of such damage 1 year following bioenhanced repair. Nor have adverse reactions to the scaffold been noted in the porcine model.

Dr. Hresko reported serving as a consultant to Depuy Spine.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WINTER RHEUMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Risk Factors for Postoperative Complications in Trigger Finger Release

Stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, is a pathology commonly referred to the plastic and hand surgery service of the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS). Patients usually present to their primary care provider with symptoms of the finger being temporarily locked or stuck in the flexed position. This can be a painful problem due to the size mismatch between the flexor tendon and the pulley under which it glides.

Patients are typically referred to surgery after failing ≥ 1 attempt at nonoperative management. The surgery is relatively quick and straightforward; however, postoperative complications can lead to an unexpected costly and lengthy recovery. The objective of this study was to identify potential risk factors that can predispose patients to postoperative complications so that those risk factors may be better anticipated and modified, if possible.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of trigger finger release surgery was performed on-site at the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, Florida, from January 2005 to December 2010 to identify risk factors associated with postoperative complications. The study was approved by both the NFSGVHS Internal Review Board and the University of Florida Institutional Review Board. Patients who underwent surgery exclusively for ≥ 1 trigger fingers by the plastic surgery service were included in the study.

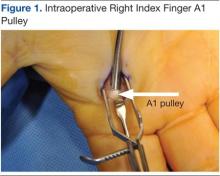

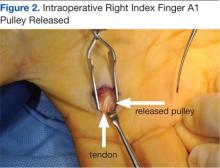

The surgery involves making an incision over the affected A1 pulley in the hand (Figure 1) and sharply releasing it (Figure 2) under direct vision. Potential risk factors for postoperative complications were recorded. These risk factors included smoking status, diabetic status, type of incision, and number of digits released during the surgical procedure.

Results

Ninety-eight digits (on 81 hands) were identified as meeting inclusion criteria. Surgeries were performed using a longitudinal (43), transverse (48), oblique (5), or Brunner (2) incision. There were 10 complications: cellulitis (3), pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis (3), scar adhesion (1), delayed healing (2), and incomplete release (1). The overall complication rate was 10.2%. The authors compared risk factors with complications, using the chi square test and a determining of P < .05.

Related: Making the Case for Minimally Invasive Surgery

There was no link found between overall postoperative complications and diabetic status, incision type, or smoking status. There was a statistically significant link between diabetic patients and the incidence of postoperative infection (P = .002) and between 2 digits operated on during the same surgery and postoperative infection (P = .027)

Discussion

The routine practice of the NFSGVHS hand clinic is to offer a steroid injection as the initial treatment for trigger finger. Health care providers (HCPs) allow no more than 3 injections to the same digit to avoid the rare but potentially serious complication of a tendon rupture.1 Due to the large NFSGVHS catchment area, wait time for elective trigger finger surgery is several months. This 3-injection plan has been well received by patients and referring providers due to these wait times. However, a recent article by Kerrigan and Stanwix concluded that the most cost-efficient treatment strategy is 2 steroid injections before surgery.2

More often than not, trigger finger release is a short, outpatient surgery with a quick recovery. To minimize the risk of stiffness and scar adhesions, the NFSGVHS practice is to refer all postoperative hand cases for ≥ 1 hand therapy appointment on the same day as their first postoperative visit.

Cost Estimates

When complications occur, they can be costly to patients due to both time spent away from home and work and additional expenses. When the current procedural terminology (CPT) codes are run through the VistA integrated billing system, based on the VHA Chief Business Office Reasonable Charges, a complication can more than double the charges associated with A1 pulley surgery.

A flexor sheath incision and drainage (I+D) (CPT 26020) charges $8,935.35 (facility charge, $6,911.95 plus professional fee, $2,023.40), compared with open trigger finger release (CPT 26055) at $8,365.66 (facility charge, $6,911.95 plus professional fee, $1,453.71). According to a conversation with the finance service officer at NFSGVHS (2/11/2014), the anesthesia bill ($490.56/15 min), anticipated level 3 emergency department visits (facility charge, $889.22 plus professional fee $493.40), and inpatient stays (daily floor bed $786.19) can make an infectious complication costly.

Trigger finger can also be released percutaneously. This is a reasonable option that avoids the operating room, but NFSGVHS surgeons prefer the open surgery due to concerns for tendon and nerve injury that can result from a blind sweep of the needle.3,4

Related: Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism After Total Joint Replacement

Existing studies found complications for trigger finger release ranging from 1% to 31%.5,6 Wound complications and joint stiffness are known complications.5-7 In this study, 60% of the complications were infections, and 80% of the complications were wound complications. Six of 8 patients with wound-healing complications received perioperative antibiotics. Three patients returned to the operating room for an I+D of the flexor sheath. The results showed a statistically significant link between > 1 digit treated at the same surgery and postoperative complications (P = .027). A PubMed search revealed no existing hand literature with this association.

Risk Factors

Diabetes, tobacco use, type of incision, and number of digits treated were assessed as risk factors for complications after trigger finger surgery. Nicotine is widely accepted as increasing the risk for wound complications.8 Almost 20% of the U.S. population smokes, compared with 22% of the VA population and 32% of active-duty military personnel.9 One in 4 veterans has been diagnosed with diabetes, a well-known predisposing factor in delayed wound healing and infection.10,11 No prior studies were found comparing type of incision or multiple digits treated as complications risk factors.

There is also a well-known association between trigger finger and diabetes. Chronic hyperglycemia results in the accumulation of collagen within tendon sheaths due to impairment of collagen breakdown. Patients with diabetes tend to present with multiple digit involvement and respond less favorably to steroid injections compared with patients without diabetes.12 Wound healing is also impaired in patients with diabetes. All 6 wound infections in this study were in patients with diabetes. Proposed etiologies for wound-healing complications include pathologic angiogenesis, impaired fibroblast proliferation and migration, impaired circulation, decreased oxygenation, and a defective immune response to the injured site.13

Trigger finger may develop in multiple digits. Once surgery has been planned for 1 digit, patients may request surgery on another digit on the same hand that has not had an attempt at nonoperative intervention. The NFSGVHS plastic surgeons have raised the threshold to offer multiple surgical procedures on the same hand at the same operative visit to minimize recovery time and number of visits, particularly when patients are travelling long distances. This may be less convenient; however, the overall cost to the patient and the health care system in the event of a complication is significant. Plastic surgery providers also run an alcohol prep pad over the incision site to prevent inoculation of the flexor sheath during suture removal.

Current recommendations to ameliorate the postoperative risks to the patient and costs to the system include endorsing a more conservative approach to treating trigger finger than was previously practiced at NFSGVHS. The known, less favorable response of patients with diabetes to steroid injections plus their elevated risk of postoperative infection create a catch-22 for the treatment plan. Given the low risk of a single steroid injection to the flexor sheath, this procedure is still recommended as a first-line treatment.

Related: Experience Tells in Hip Arthroplasty

During the 5-year study there was a lower threshold for surgical management and for treatment of multiple digits during the same surgery than the one currently practiced, with an overall consensus of the hospital’s HCPs. The authors recommend that all patients start with a steroid injection before committing to surgery. Patients with diabetes are informed that the injection will cause a temporary rise in their blood glucose.14 If they are resistant to the injection, high-dose oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or proximal interphalangeal joint splinting is ordered.

Verification of A1C values showing better chronic management of blood sugar is a procedure HCPs from the NFSGVHS will begin to follow. Preoperative A1C values between 6.5% and 8% in patients known to have diabetes has been recommended.15 A1C values > 7% have been found to be an independent risk factor for stenosing tenosynovitis.16 The total number of trigger finger surgeries may drop with the benefit of improved utilization of resources.

Conclusion

The authors found a statistically significant association between postoperative infection and 2 patient populations: patients with diabetes (P = .002) and patients having > 1 digit released during the same surgery (P = .027). This outcome suggests using caution when offering A1 pulley release in select patient populations.

Acknowledgement

Justine Pierson, BS, research coordinator at University of Florida, for statistical analysis. Funding is through salary.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Yamada K, Masuko, T, Iwasaki N. Rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon after injections of insoluble steroid for a trigger finger. J Hand Surg Eur. 2011;36(1):77-78.

2. Kerrigan CL, Stanwix MG. Using evidence to minimize the cost of trigger finger care. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(6):997-1005.

3. Habbu R, Putnam MD, Adams JE. Percutaneous Release of the A1 pulley: a cadaver study. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(11):2273-2277.

4. Guler F, Kose O, Ercan EC, Turan A, Canbora K. Open vs percutaneous release for the treatment of trigger thumb. Orthopedics. 2013;36(10):e1290-e1294.

5. Lim M-H, Lim K-K, Rasheed MZ, Narayana S, Tan B-H. Outcome of open trigger digit release. J Hand Surg Eur. 2007;32(4):457-479.

6. Will R, Lubahn J. Complications of open trigger finger release. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(4):594-596.

7. Lee WT, Chong AK. Outcome study of open trigger digit release. J Hand Surg Eur. 2011;36(4):339.

8. Rinker B. The evils of nicotine: An evidence-based guide to smoking and plastic surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70(5):599-605.

9. Bondurant S, Wedge R, eds. Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 2009.

10. Shilling AM, Raphael J. Diabetes, hyperglycemia, and infections. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2008;22(3):519-535.

11. Kuppersmith J, Francis J, Kerr E, et al. Advancing evidence-based care for diabetes: Lessons from the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff. 2007;26(2):156-158.

12. Brown E, Genoway KA. Impact of diabetes on outcomes in hand surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(12):2067-2072.

13. Francis-Goforth KN, Harken AH, Saba JD. Normalization of diabetic wound healing. Surgery. 2010;147(3):446-449.

14. Wang AA, Hutchinson DT. The effect of corticosteroid injection for trigger finger on blood glucose level in diabetic patients. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(6):979-981.

15. Underwood P, Askari R, Hurwitz S, Chamarthi B, Garg R. Preoperative A1C and Clinical Outcomes in patients with diabetes undergoing major noncardiac surgical procedures. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37(3): 611-616.

16. Vance MC, Tucker JJ, Harness NG. The association of hemoglobin A1c with the prevalence of stenosing tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(9):1765-1769.

Stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, is a pathology commonly referred to the plastic and hand surgery service of the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS). Patients usually present to their primary care provider with symptoms of the finger being temporarily locked or stuck in the flexed position. This can be a painful problem due to the size mismatch between the flexor tendon and the pulley under which it glides.

Patients are typically referred to surgery after failing ≥ 1 attempt at nonoperative management. The surgery is relatively quick and straightforward; however, postoperative complications can lead to an unexpected costly and lengthy recovery. The objective of this study was to identify potential risk factors that can predispose patients to postoperative complications so that those risk factors may be better anticipated and modified, if possible.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of trigger finger release surgery was performed on-site at the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, Florida, from January 2005 to December 2010 to identify risk factors associated with postoperative complications. The study was approved by both the NFSGVHS Internal Review Board and the University of Florida Institutional Review Board. Patients who underwent surgery exclusively for ≥ 1 trigger fingers by the plastic surgery service were included in the study.

The surgery involves making an incision over the affected A1 pulley in the hand (Figure 1) and sharply releasing it (Figure 2) under direct vision. Potential risk factors for postoperative complications were recorded. These risk factors included smoking status, diabetic status, type of incision, and number of digits released during the surgical procedure.

Results

Ninety-eight digits (on 81 hands) were identified as meeting inclusion criteria. Surgeries were performed using a longitudinal (43), transverse (48), oblique (5), or Brunner (2) incision. There were 10 complications: cellulitis (3), pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis (3), scar adhesion (1), delayed healing (2), and incomplete release (1). The overall complication rate was 10.2%. The authors compared risk factors with complications, using the chi square test and a determining of P < .05.

Related: Making the Case for Minimally Invasive Surgery

There was no link found between overall postoperative complications and diabetic status, incision type, or smoking status. There was a statistically significant link between diabetic patients and the incidence of postoperative infection (P = .002) and between 2 digits operated on during the same surgery and postoperative infection (P = .027)

Discussion

The routine practice of the NFSGVHS hand clinic is to offer a steroid injection as the initial treatment for trigger finger. Health care providers (HCPs) allow no more than 3 injections to the same digit to avoid the rare but potentially serious complication of a tendon rupture.1 Due to the large NFSGVHS catchment area, wait time for elective trigger finger surgery is several months. This 3-injection plan has been well received by patients and referring providers due to these wait times. However, a recent article by Kerrigan and Stanwix concluded that the most cost-efficient treatment strategy is 2 steroid injections before surgery.2

More often than not, trigger finger release is a short, outpatient surgery with a quick recovery. To minimize the risk of stiffness and scar adhesions, the NFSGVHS practice is to refer all postoperative hand cases for ≥ 1 hand therapy appointment on the same day as their first postoperative visit.

Cost Estimates

When complications occur, they can be costly to patients due to both time spent away from home and work and additional expenses. When the current procedural terminology (CPT) codes are run through the VistA integrated billing system, based on the VHA Chief Business Office Reasonable Charges, a complication can more than double the charges associated with A1 pulley surgery.

A flexor sheath incision and drainage (I+D) (CPT 26020) charges $8,935.35 (facility charge, $6,911.95 plus professional fee, $2,023.40), compared with open trigger finger release (CPT 26055) at $8,365.66 (facility charge, $6,911.95 plus professional fee, $1,453.71). According to a conversation with the finance service officer at NFSGVHS (2/11/2014), the anesthesia bill ($490.56/15 min), anticipated level 3 emergency department visits (facility charge, $889.22 plus professional fee $493.40), and inpatient stays (daily floor bed $786.19) can make an infectious complication costly.

Trigger finger can also be released percutaneously. This is a reasonable option that avoids the operating room, but NFSGVHS surgeons prefer the open surgery due to concerns for tendon and nerve injury that can result from a blind sweep of the needle.3,4

Related: Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism After Total Joint Replacement

Existing studies found complications for trigger finger release ranging from 1% to 31%.5,6 Wound complications and joint stiffness are known complications.5-7 In this study, 60% of the complications were infections, and 80% of the complications were wound complications. Six of 8 patients with wound-healing complications received perioperative antibiotics. Three patients returned to the operating room for an I+D of the flexor sheath. The results showed a statistically significant link between > 1 digit treated at the same surgery and postoperative complications (P = .027). A PubMed search revealed no existing hand literature with this association.

Risk Factors

Diabetes, tobacco use, type of incision, and number of digits treated were assessed as risk factors for complications after trigger finger surgery. Nicotine is widely accepted as increasing the risk for wound complications.8 Almost 20% of the U.S. population smokes, compared with 22% of the VA population and 32% of active-duty military personnel.9 One in 4 veterans has been diagnosed with diabetes, a well-known predisposing factor in delayed wound healing and infection.10,11 No prior studies were found comparing type of incision or multiple digits treated as complications risk factors.

There is also a well-known association between trigger finger and diabetes. Chronic hyperglycemia results in the accumulation of collagen within tendon sheaths due to impairment of collagen breakdown. Patients with diabetes tend to present with multiple digit involvement and respond less favorably to steroid injections compared with patients without diabetes.12 Wound healing is also impaired in patients with diabetes. All 6 wound infections in this study were in patients with diabetes. Proposed etiologies for wound-healing complications include pathologic angiogenesis, impaired fibroblast proliferation and migration, impaired circulation, decreased oxygenation, and a defective immune response to the injured site.13

Trigger finger may develop in multiple digits. Once surgery has been planned for 1 digit, patients may request surgery on another digit on the same hand that has not had an attempt at nonoperative intervention. The NFSGVHS plastic surgeons have raised the threshold to offer multiple surgical procedures on the same hand at the same operative visit to minimize recovery time and number of visits, particularly when patients are travelling long distances. This may be less convenient; however, the overall cost to the patient and the health care system in the event of a complication is significant. Plastic surgery providers also run an alcohol prep pad over the incision site to prevent inoculation of the flexor sheath during suture removal.

Current recommendations to ameliorate the postoperative risks to the patient and costs to the system include endorsing a more conservative approach to treating trigger finger than was previously practiced at NFSGVHS. The known, less favorable response of patients with diabetes to steroid injections plus their elevated risk of postoperative infection create a catch-22 for the treatment plan. Given the low risk of a single steroid injection to the flexor sheath, this procedure is still recommended as a first-line treatment.

Related: Experience Tells in Hip Arthroplasty

During the 5-year study there was a lower threshold for surgical management and for treatment of multiple digits during the same surgery than the one currently practiced, with an overall consensus of the hospital’s HCPs. The authors recommend that all patients start with a steroid injection before committing to surgery. Patients with diabetes are informed that the injection will cause a temporary rise in their blood glucose.14 If they are resistant to the injection, high-dose oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or proximal interphalangeal joint splinting is ordered.

Verification of A1C values showing better chronic management of blood sugar is a procedure HCPs from the NFSGVHS will begin to follow. Preoperative A1C values between 6.5% and 8% in patients known to have diabetes has been recommended.15 A1C values > 7% have been found to be an independent risk factor for stenosing tenosynovitis.16 The total number of trigger finger surgeries may drop with the benefit of improved utilization of resources.

Conclusion

The authors found a statistically significant association between postoperative infection and 2 patient populations: patients with diabetes (P = .002) and patients having > 1 digit released during the same surgery (P = .027). This outcome suggests using caution when offering A1 pulley release in select patient populations.

Acknowledgement

Justine Pierson, BS, research coordinator at University of Florida, for statistical analysis. Funding is through salary.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, is a pathology commonly referred to the plastic and hand surgery service of the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS). Patients usually present to their primary care provider with symptoms of the finger being temporarily locked or stuck in the flexed position. This can be a painful problem due to the size mismatch between the flexor tendon and the pulley under which it glides.

Patients are typically referred to surgery after failing ≥ 1 attempt at nonoperative management. The surgery is relatively quick and straightforward; however, postoperative complications can lead to an unexpected costly and lengthy recovery. The objective of this study was to identify potential risk factors that can predispose patients to postoperative complications so that those risk factors may be better anticipated and modified, if possible.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of trigger finger release surgery was performed on-site at the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville, Florida, from January 2005 to December 2010 to identify risk factors associated with postoperative complications. The study was approved by both the NFSGVHS Internal Review Board and the University of Florida Institutional Review Board. Patients who underwent surgery exclusively for ≥ 1 trigger fingers by the plastic surgery service were included in the study.

The surgery involves making an incision over the affected A1 pulley in the hand (Figure 1) and sharply releasing it (Figure 2) under direct vision. Potential risk factors for postoperative complications were recorded. These risk factors included smoking status, diabetic status, type of incision, and number of digits released during the surgical procedure.

Results

Ninety-eight digits (on 81 hands) were identified as meeting inclusion criteria. Surgeries were performed using a longitudinal (43), transverse (48), oblique (5), or Brunner (2) incision. There were 10 complications: cellulitis (3), pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis (3), scar adhesion (1), delayed healing (2), and incomplete release (1). The overall complication rate was 10.2%. The authors compared risk factors with complications, using the chi square test and a determining of P < .05.

Related: Making the Case for Minimally Invasive Surgery

There was no link found between overall postoperative complications and diabetic status, incision type, or smoking status. There was a statistically significant link between diabetic patients and the incidence of postoperative infection (P = .002) and between 2 digits operated on during the same surgery and postoperative infection (P = .027)

Discussion

The routine practice of the NFSGVHS hand clinic is to offer a steroid injection as the initial treatment for trigger finger. Health care providers (HCPs) allow no more than 3 injections to the same digit to avoid the rare but potentially serious complication of a tendon rupture.1 Due to the large NFSGVHS catchment area, wait time for elective trigger finger surgery is several months. This 3-injection plan has been well received by patients and referring providers due to these wait times. However, a recent article by Kerrigan and Stanwix concluded that the most cost-efficient treatment strategy is 2 steroid injections before surgery.2

More often than not, trigger finger release is a short, outpatient surgery with a quick recovery. To minimize the risk of stiffness and scar adhesions, the NFSGVHS practice is to refer all postoperative hand cases for ≥ 1 hand therapy appointment on the same day as their first postoperative visit.

Cost Estimates

When complications occur, they can be costly to patients due to both time spent away from home and work and additional expenses. When the current procedural terminology (CPT) codes are run through the VistA integrated billing system, based on the VHA Chief Business Office Reasonable Charges, a complication can more than double the charges associated with A1 pulley surgery.

A flexor sheath incision and drainage (I+D) (CPT 26020) charges $8,935.35 (facility charge, $6,911.95 plus professional fee, $2,023.40), compared with open trigger finger release (CPT 26055) at $8,365.66 (facility charge, $6,911.95 plus professional fee, $1,453.71). According to a conversation with the finance service officer at NFSGVHS (2/11/2014), the anesthesia bill ($490.56/15 min), anticipated level 3 emergency department visits (facility charge, $889.22 plus professional fee $493.40), and inpatient stays (daily floor bed $786.19) can make an infectious complication costly.

Trigger finger can also be released percutaneously. This is a reasonable option that avoids the operating room, but NFSGVHS surgeons prefer the open surgery due to concerns for tendon and nerve injury that can result from a blind sweep of the needle.3,4

Related: Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism After Total Joint Replacement

Existing studies found complications for trigger finger release ranging from 1% to 31%.5,6 Wound complications and joint stiffness are known complications.5-7 In this study, 60% of the complications were infections, and 80% of the complications were wound complications. Six of 8 patients with wound-healing complications received perioperative antibiotics. Three patients returned to the operating room for an I+D of the flexor sheath. The results showed a statistically significant link between > 1 digit treated at the same surgery and postoperative complications (P = .027). A PubMed search revealed no existing hand literature with this association.

Risk Factors

Diabetes, tobacco use, type of incision, and number of digits treated were assessed as risk factors for complications after trigger finger surgery. Nicotine is widely accepted as increasing the risk for wound complications.8 Almost 20% of the U.S. population smokes, compared with 22% of the VA population and 32% of active-duty military personnel.9 One in 4 veterans has been diagnosed with diabetes, a well-known predisposing factor in delayed wound healing and infection.10,11 No prior studies were found comparing type of incision or multiple digits treated as complications risk factors.

There is also a well-known association between trigger finger and diabetes. Chronic hyperglycemia results in the accumulation of collagen within tendon sheaths due to impairment of collagen breakdown. Patients with diabetes tend to present with multiple digit involvement and respond less favorably to steroid injections compared with patients without diabetes.12 Wound healing is also impaired in patients with diabetes. All 6 wound infections in this study were in patients with diabetes. Proposed etiologies for wound-healing complications include pathologic angiogenesis, impaired fibroblast proliferation and migration, impaired circulation, decreased oxygenation, and a defective immune response to the injured site.13

Trigger finger may develop in multiple digits. Once surgery has been planned for 1 digit, patients may request surgery on another digit on the same hand that has not had an attempt at nonoperative intervention. The NFSGVHS plastic surgeons have raised the threshold to offer multiple surgical procedures on the same hand at the same operative visit to minimize recovery time and number of visits, particularly when patients are travelling long distances. This may be less convenient; however, the overall cost to the patient and the health care system in the event of a complication is significant. Plastic surgery providers also run an alcohol prep pad over the incision site to prevent inoculation of the flexor sheath during suture removal.

Current recommendations to ameliorate the postoperative risks to the patient and costs to the system include endorsing a more conservative approach to treating trigger finger than was previously practiced at NFSGVHS. The known, less favorable response of patients with diabetes to steroid injections plus their elevated risk of postoperative infection create a catch-22 for the treatment plan. Given the low risk of a single steroid injection to the flexor sheath, this procedure is still recommended as a first-line treatment.

Related: Experience Tells in Hip Arthroplasty

During the 5-year study there was a lower threshold for surgical management and for treatment of multiple digits during the same surgery than the one currently practiced, with an overall consensus of the hospital’s HCPs. The authors recommend that all patients start with a steroid injection before committing to surgery. Patients with diabetes are informed that the injection will cause a temporary rise in their blood glucose.14 If they are resistant to the injection, high-dose oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or proximal interphalangeal joint splinting is ordered.

Verification of A1C values showing better chronic management of blood sugar is a procedure HCPs from the NFSGVHS will begin to follow. Preoperative A1C values between 6.5% and 8% in patients known to have diabetes has been recommended.15 A1C values > 7% have been found to be an independent risk factor for stenosing tenosynovitis.16 The total number of trigger finger surgeries may drop with the benefit of improved utilization of resources.

Conclusion

The authors found a statistically significant association between postoperative infection and 2 patient populations: patients with diabetes (P = .002) and patients having > 1 digit released during the same surgery (P = .027). This outcome suggests using caution when offering A1 pulley release in select patient populations.

Acknowledgement

Justine Pierson, BS, research coordinator at University of Florida, for statistical analysis. Funding is through salary.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Yamada K, Masuko, T, Iwasaki N. Rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon after injections of insoluble steroid for a trigger finger. J Hand Surg Eur. 2011;36(1):77-78.

2. Kerrigan CL, Stanwix MG. Using evidence to minimize the cost of trigger finger care. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(6):997-1005.

3. Habbu R, Putnam MD, Adams JE. Percutaneous Release of the A1 pulley: a cadaver study. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(11):2273-2277.

4. Guler F, Kose O, Ercan EC, Turan A, Canbora K. Open vs percutaneous release for the treatment of trigger thumb. Orthopedics. 2013;36(10):e1290-e1294.

5. Lim M-H, Lim K-K, Rasheed MZ, Narayana S, Tan B-H. Outcome of open trigger digit release. J Hand Surg Eur. 2007;32(4):457-479.

6. Will R, Lubahn J. Complications of open trigger finger release. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(4):594-596.

7. Lee WT, Chong AK. Outcome study of open trigger digit release. J Hand Surg Eur. 2011;36(4):339.

8. Rinker B. The evils of nicotine: An evidence-based guide to smoking and plastic surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70(5):599-605.

9. Bondurant S, Wedge R, eds. Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 2009.

10. Shilling AM, Raphael J. Diabetes, hyperglycemia, and infections. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2008;22(3):519-535.

11. Kuppersmith J, Francis J, Kerr E, et al. Advancing evidence-based care for diabetes: Lessons from the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff. 2007;26(2):156-158.

12. Brown E, Genoway KA. Impact of diabetes on outcomes in hand surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(12):2067-2072.

13. Francis-Goforth KN, Harken AH, Saba JD. Normalization of diabetic wound healing. Surgery. 2010;147(3):446-449.

14. Wang AA, Hutchinson DT. The effect of corticosteroid injection for trigger finger on blood glucose level in diabetic patients. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(6):979-981.

15. Underwood P, Askari R, Hurwitz S, Chamarthi B, Garg R. Preoperative A1C and Clinical Outcomes in patients with diabetes undergoing major noncardiac surgical procedures. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37(3): 611-616.

16. Vance MC, Tucker JJ, Harness NG. The association of hemoglobin A1c with the prevalence of stenosing tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(9):1765-1769.

1. Yamada K, Masuko, T, Iwasaki N. Rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon after injections of insoluble steroid for a trigger finger. J Hand Surg Eur. 2011;36(1):77-78.

2. Kerrigan CL, Stanwix MG. Using evidence to minimize the cost of trigger finger care. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(6):997-1005.

3. Habbu R, Putnam MD, Adams JE. Percutaneous Release of the A1 pulley: a cadaver study. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(11):2273-2277.

4. Guler F, Kose O, Ercan EC, Turan A, Canbora K. Open vs percutaneous release for the treatment of trigger thumb. Orthopedics. 2013;36(10):e1290-e1294.

5. Lim M-H, Lim K-K, Rasheed MZ, Narayana S, Tan B-H. Outcome of open trigger digit release. J Hand Surg Eur. 2007;32(4):457-479.

6. Will R, Lubahn J. Complications of open trigger finger release. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(4):594-596.

7. Lee WT, Chong AK. Outcome study of open trigger digit release. J Hand Surg Eur. 2011;36(4):339.

8. Rinker B. The evils of nicotine: An evidence-based guide to smoking and plastic surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70(5):599-605.

9. Bondurant S, Wedge R, eds. Combating Tobacco Use in Military and Veteran Populations. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 2009.

10. Shilling AM, Raphael J. Diabetes, hyperglycemia, and infections. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2008;22(3):519-535.

11. Kuppersmith J, Francis J, Kerr E, et al. Advancing evidence-based care for diabetes: Lessons from the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff. 2007;26(2):156-158.

12. Brown E, Genoway KA. Impact of diabetes on outcomes in hand surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(12):2067-2072.

13. Francis-Goforth KN, Harken AH, Saba JD. Normalization of diabetic wound healing. Surgery. 2010;147(3):446-449.

14. Wang AA, Hutchinson DT. The effect of corticosteroid injection for trigger finger on blood glucose level in diabetic patients. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31(6):979-981.

15. Underwood P, Askari R, Hurwitz S, Chamarthi B, Garg R. Preoperative A1C and Clinical Outcomes in patients with diabetes undergoing major noncardiac surgical procedures. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37(3): 611-616.

16. Vance MC, Tucker JJ, Harness NG. The association of hemoglobin A1c with the prevalence of stenosing tenosynovitis. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(9):1765-1769.

Arthritis, Infectious Tenosynovitis, and Tendon Rupture in a Patient With Rheumatoid Arthritis and Psoriasis

Compared with monoarticular arthritis, polyarticular arthritis may yield an initially narrower differential diagnosis that focuses on systemic inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Approximately 15% to 30% of septic arthritis is polyarticular, of which about 45% is associated with underlying RA.1,2 Regardless of the number of joints involved, septic (infectious) arthritis is a valid consideration given the morbidity and mortality.

In a retrospective study in the United Kingdom (UK) between 1982 and 1991, the morbidity and mortality of septic arthritis was 31.6% and 11.5%, respectively, and 16% of the study population had RA.3 A review of the literature by Dubost and colleagues found that polyarticular septic arthritis (PASA) has a mortality of 31% to 42% compared with 4% to 8% for monoarticular septic arthritis, and RA was present in 67% of the PASA fatalities.1

Related: The Golden Era of Treatment in Rheumatology

Rheumatoid arthritis and its treatment predispose patients to septic arthritis. Septic arthritis in the UK general population is 0.42 per 100 patient-years for patients with RA on antitumor necrosis factor therapy.3,4 In a retrospective study in the U.S., the incidence of septic arthritis was 0.40 per 100 patient-years for patients with RA compared with 0.02 per 100 patient-years for patients without RA.5

Other complications of RA include infectious tenosynovitis and tendon rupture. The incidence and prevalence of infectious tenosynovitis and tendon rupture in RA are not firmly established in the literature.

We present a patient with RA and psoriasis who responded initially to acute management for RA but subsequently was diagnosed with culture-negative polyarticular arthritis and infectious tenosynovitis associated with beta hemolytic group G Streptococcus (GGS), a part of Streptococcus milleri (S. milleri). During surgery, he was also found to have bilateral extensor pollicus longus (EPL) tendon rupture. Given the possible morbidity, the authors believe this patient may be of interest to the medical community.

Case Presentation

A 69-year-old African American male presented with 3 to 4 days of swelling and pain of bilateral wrists, bilateral hands, and the left ankle with subjective, but resolved, fevers and chills. His medical history was significant for seropositive erosive RA, psoriasis, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, alcohol abuse, chronic tobacco use, osteoporosis, and glaucoma. He did not have diabetes, reported no IV drug abuse, and except for the immunosuppressive effects of his medications, was not otherwise immunocompromised.

For 2 years in the outpatient setting, the rheumatology clinic had been managing the patient’s rheumatoid factor (RF) positive and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody positive erosive RA with etanercept 25 mg subcutaneously twice a week. The RA affected his hands, wrists, shoulders, and ankles bilaterally but was successfully controlled. The dermatology clinic was managing the patient’s psoriasis with calcipotriene cream 0.005% twice a week and clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice a week. Psoriatic plaques were noted on bilateral elbows, bilateral dorsal hands, and bilateral dorsal feet.

Initial Evaluation

At evaluation, the patient’s vital signs revealed a temperature of 36.3°C (97.3°F), pulse of 102 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation of 99% on room air, and blood pressure of 102/70 mm Hg. He was found to have edema, tenderness, and erythema of the wrists bilaterally and left metacarpophalangeal joints (MCPs) and edematous right MCPs and left medial ankle.

The patient had been nonadherent with etanercept for 5 monthsand restarted taking the medication only 2 weeks before presentation. He had noticed worsening arthritis for at least 1 month. His last RA flare was approximately 1 year before presentation. Additional symptoms included 4 days of nausea, nonbloody and nonbilious emesis, left lower quadrant pain, and diarrhea without melena or hematochezia.

Initial laboratory studies found 3.2 k/μL white blood cells (WBCs) with a differential of 11.9% lymphocytes, 4.2% monocytes, 83.3% neutrophils, 0.5% eosinophils, and 0.1% basophils; 165 k/μL platelets; 96 mm/h erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); and 45 mg/dL C-reactive protein. The patient was diagnosed with viral gastroenteritis and RA flare and was admitted for inpatient management secondary to limited ability to care for himself.

Related: Infliximab-Induced Complications

The patient was started on prednisone 40 mg orally once a day (for 5 days) for empiric treatment of an RA flare and continued on etanercept. The inpatient rheumatology service was consulted. Further evaluation later that day found involvement of the proximal interphalangeal joints and elbows and tenderness of the tendons of the dorsal hand bilaterally. Over the next 2 days, the patient remained afebrile and WBCs were within normal limits. Edema, erythema, and tenderness of the involved joints somewhat improved, but tenderness along the tendons of the dorsal hand worsened, which concerned the managing teams for infectious tenosynovitis.

By day 4, the patient was afebrile and had a leukocytosis of 12.9 k/μLwith neutrophils 86.7%, but improvement of erythema, pain, and range of motion of involved joints and no tenderness to palpation of tendons was noted. The inpatient orthopedic surgery service evaluated the patient and did not find sufficient evidence necessitating surgical intervention.

Worsening Condition

On day 6, arthrocentesis of the left wrist was performed secondary to worsening of erythema and edema. The patient experienced new edema of the left shoulder and leukocytosis continued to trend upward (15.7 k/μL on day 6). Purulent aspirate (1.5 mL) was obtained from the fluctuance and tenosynovium of the left wrist. Empiric vancomycin 1 g IV twice daily and ceftriaxone 2 g IV daily were started and continued for 3 days. By this point in his hospital course, the patient had received 1 dose of etanercept. Prednisone and etanercept were previously discontinued because of the discovered infection. Blood cultures were drawn and had no growth (Table). Gastroenterology studies were limited to stool cultures and did not include colonoscopy. Leukocytosis began trending down.

On day 8, antibiotics were tailored to penicillin G 4 million units IV every 4 hours following growth of GGS from the sample of the left wrist. Subsequently, synovial fluid (3 mL) from the left shoulder was obtained following initiation of antibiotic therapy and had no growth. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) found tenosynovitis of the left ankle and right wrist.